The Framing of Sexual

Harassment in German Online

Newspapers:

A Critical Discourse Analysis of the

Online News Coverage of the Two

Biggest German Newspapers on Sexual

Harassment in the Light of #MeToo in

Late 2017

by Renée Leifermann

Master’s Programme – Culture, Collaborative Media and Creative Industries One-Year Master, 15 Credits

August 2018 Malmö University Supervisor: Erin Cory

Abstract

This thesis looks into the online news representation of the #MeToo movement, started by actress Alyssa Milano in October 2017, in the two biggest German newspapers, Süddeutsche Zeitung and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung between October 2017 and January 2017. The purpose of this study is to examine how the online editorial departments of the two biggest German newspapers frame and represent sexual harassment in the light of #MeToo. Additionally, I want to determine how the news coverage developed from when Harvey Weinstein first was accused of sexual misconduct in October 2017, touching upon the occurrence of the now famous hashtag roughly two weeks later and another three months later when German TV director Dieter Wedel faced similar allegations. To do so, I conducted a Critical Discourse Analysis of 19 online newspaper articles. The analysis is divided into three parts: Text level, discursive practice and social practice. Resulting from the analysis, one can see that sexual harassment in Germany still is not recognised as an issue of gender inequality but rather a matter of individual responsibility and systemic structures in certain industries, especially when German stakeholders are involved.

Keywords: critical discourse analysis, framing, sexual harassment, social media,

Content

List of Images List of Tables List of Diagrams

Introduction 6

Purpose Of This Study 9

Research Questions 10

Literature Review 11

Framing Sexual Harassment And Other Feminist Topics In News Media 11

Social Media And Hashtag Activism 13

The German Perspective 15

Theoretical Concepts and Analytical Framework 20

Agenda Setting And Framing 20

Representation 22

Discourse 24

Methodology 26

Choice Of Method: Critical Discourse Analysis 26

Research Approach And Paradigm 28

Data Collection 30

Data Analysis 31

Ethics 32

Analysis and Discussion 34

Text Level And Interdiscursivity 34

Individual Discourse 37

Systemic Discourse 40

Gender Equality Discourse 44

Techno-Legal Discourse 46 Summary 46 Social Practice 47 Conclusion 55 Limitations 59 References 61 Online Resources 67 Appendix 75

List Of Images

Image 1: Screenshot of tweet by Milano 6 Image 2: Fairclough’s three dimensional model (Fairclough 1992) 26

List Of Tables

Table 1: Female representations 34

Table 2: Male representations 34

List Of Diagrams

Introduction

In 2018 sexual harassment and gender inequality still are important issue within German society: 43% of the German female population indicated that they have been sexually harassed at least once in their live (YouGov as quoted in ZEIT ONLINE 2017) and according to the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE 2017), in a ranking of all 28 EU member states, Germany only ranks 12th when it comes to work, health and political representation.

The online world offers a lot of opportunities for all kinds of political engagement, activism and protests to fight societal problems (Easteal et al. 2015). It offers a “great potential for broadly disseminating feminist ideas, shaping new modes of discourse about gender and sexism, connecting to different constituencies, and allowing creative modes of protest to emerge” (Baer 2016, p.18). The social media platform Twitter has become an especially popular discursive outlet for public discussion and (feminist) protests (Drüeke & Zobl 2016). In the past, creative types of protest have increasingly emerged in the form of Twitter hashtags. #EverydaySexism, #YesAllWomen and #Aufschrei (“outcry”, German speaking countries only) are only few successful examples. Since October 2017, we face a new powerful hashtag campaign, perhaps the most powerful of them all: #MeToo.

Although activist Tarana Burke invented the hashtag years ago, it needed Harvey Weinstein and Alyssa Milano to go viral: In October 2017, over 50 women started to accuse the famous film producer of sexual harassment and assault. It all came to light when the New York Times (NYT) published an elaborate article on the matter on October 5th, 2017 (Kantor & Twohey 2017). On October 15, actress Milano took #MeToo to Twitter and encouraged all women who have been sexually assaulted or harassed to change their social media status accordingly in order to illustrate the dimension the problem (Milano 2017).

Image 1: Screenshot of tweet by Milano

Since then, #MeToo has been retweeted almost 25,000 times, received 53,000 likes and 68,000 comments. Since #MeToo, Weinstein has not been the only public figure accused with assault or harassment, resulting in a “rapid downfall of those accused, leading to prompt resignations and terminations from their respective roles” (Hudson 2018, p.1). In January 2018, the first public figure within the German film industry, Dieter Wedel, a director and screenwriter, faced similar allegations after an article was published in ZEITmagazin (ZEITmagazin 2018).

Social media platforms were not the only spaces that jumped on the #MeToo bandwagon. There has been a lot of news coverage on the topic, including all the important newspapers of the Western world. The NYT even awarded the women pushing the movement – the “silence breakers” – with the title of “2017 Person of the Year” (Hudson 2018). Some non-Western countries like India, South Africa or Russia joined the #MeToo debate, tool (Süddeutsche Zeitung 2018a). Even months after the outbreak of #MeToo, related articles are published in important newspapers on regular basis. Compared to other countries, #MeToo spread rather slowly in Germany. Germany even seemed “immune” to the #MeToo debate with barely any cases within the first months. It was only in January 2018 when Wedel was accused with sexual assault (Kirschbaum 2018).

With #MeToo, sexual violence suddenly became a publicly discussed topic. Before, there was rather little public debate about sexual harassment in Germany

(Zippel 2006). According to agenda setting theory, the media can shape the priorities of the public by putting the focus on certain issues (Scheufele 2000). Naturally, sexual abuse has been a problem before #MeToo. Media of course should portray social phenomena. However, a large majority of sexual assault victims are female (WHO 2013) while the majority of powerful newsmakers still is male (Hodkinson 2017). They determine the editorial agenda – the portrayal of events, people, groups etc. more than often is selective (Hodkinson 2017). Therefore, it took #MeToo to make the magnitude of sexual assault visible for everyone.

I chose this topic due to my personal interest in the German handling of sexual harassment and in feminism in general. Being a woman, I had my own experiences with sexual harassment and therefore, I find it interesting how the media frame sexual misconduct, especially in the light of #MeToo. With the rise of #MeToo, I am curious how the news coverage in Germany evolved around that topic. Additionally, the feminist understanding of sexual harassment traditionally considers it as being reflective of patriarchal worldviews, male dominance, misogyny and sexism (Easteal et al. 2015). I am interested in how the German society sees sexual harassment and the dominant discourses around it. I chose to focus on the film industry because it is where #MeToo went viral when the allegations against Weinstein were made. I find it interesting that there were similar accusations against a US-American film producer and a German film director. I think it interestingly displays traditional power structures and relations between powerful men in the role of producers or directors and women in the role of actresses or assistants. Additionally, according to McDonald and Charlesworth (2013), there has been little research on how sexual harassment is presented in media texts, such as newspaper articles.

Following this brief introduction, I will explain the purpose and underlying research question of this study. Subsequently, I will focus on a literature review of the field, lay out my theoretical framework in which I set up the most important concepts supporting my research, set up an analytical framework that acts as a guideline for

my research and explain the methodology used within this research, including my research approach and the research paradigm I place my study within as well as a brief explanation of how I collected and analysed my data. I will then explain ethical aspects that need to be considered before I lay out my analysis. Lastly, I will draw my conclusions and discuss my outcomes and the limitations of my research.

Purpose Of This Study

I want to examine how the online editorial departments of the two biggest German newspapers frame and represent sexual harassment in the light of #MeToo. Additionally, I want to determine how the news coverage developed from when Weinstein first was accused with sexual misconduct in October 2017, touching upon the occurrence of the now famous hashtag roughly two weeks later and another three months later when German TV director Wedel faced similar allegations.

To fulfill said purpose, I will focus on the two biggest German daily newspapers: Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ) and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) because they have a similar circulation (Statista 2017) and represent two different political positions: While SZ is popular for having a liberal, centre-left attitude, FAZ is well-known for being conservative (euro topics 2018). I analyse 19 articles dealing with sexual harassment and published online by SZ and FZ, within three days after the article on Harvey Weinstein was published in the NYT, three days after Milano tweeted about #MeToo on social media, and three days after the article on Dieter Wedel was published in ZEITmagazin. My analysis will be embedded in Fairclough’s Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). I will divide my analysis in three levels: text analysis, discursive practice and social practice. I want to review the representations the journalists use to offer subject positions to the men and women involved (text level), I plan to study the nodal points of the articles, how they present the discourse of sexual harassment and the relation between the discourse (interdiscursivity/discursive practice), and thirdly, I plan to place my

findings in the sociocultural context of sexual harassment in Germany (social practice).

Research Questions

To guide my research and fulfil the purpose of my study, I came up with the following research question:

How did the framing of sexual harassment in the film industry by the two biggest German newspapers develop with the occurrence of #MeToo online between October 2017 and January 2018?

In order to answer this research question, I set up the following sub-questions I plan to answer with my research:

1. What subject positions are on offer in the newspaper articles at all three stages, concerning the men and women involved?

2. What is the dominant discourse of sexual harassment in each article at all three stages, how is it reflected in the nodal points?

3. How can we understand the discursive formations established with the help of question one and two in the context of hegemonic ideas about what constitutes sexual harassment in Germany?

Literature Review

Framing Sexual Harassment And Other Feminist Topics In News Media

Feminism and feminist topics like sexual harassment or sexual assault but also violence against women in general look back at a long history of having a hard time in the news media world (Baker Beck 1998; Easteal et al. 2015; Bronstein 2005). Especially when it comes to feminist issues, news media often use frames that distance violent and sexist acts from their underlying social cause(s) (Easteal et al. 2015). In sum, the media portrayal of sexual harassment is often problematic as it often is misleading, simplistic and combined with “clichéd characters” which in turn results in society perceiving violence against women as this simplified patriarchal concept (Easteal et al. 2015, p. 111). Or in other words, the media framing of violence against women, for instance sexual harassment, reinforces conservative, patriarchal worldview (Easteal et al. 2015).

In 1992, Helen Benedict, author, journalist and professor at Columbia University published her book Virgin or Vamp: How the Press Covers Sex Crimes where she summarises the history of sex crimes in news media up until 1992. According to Benedict (1992), the press always has covered sex crimes – which I consider sexual harassment to fall under – with bias and prejudice. This happens partly due to the habits in the newsroom and partly due to the public attitude towards women but also towards sex and violence in general. Benedict (1992) thinks that the press has the power to establish and reinforce those attitudes. During her research, the author found a continuous decrease in the quality of news coverage on sex crimes during the 1980s and 1990s. Additionally, the sympathy for the rape victim and the empathy with them decreased. Generally, the news coverage of sex crimes is selective: crimes against white women tend to be covered more frequently, so do crimes with black offenders (Benedict 1992).

According to Saguy (2002), news coverage on sexual harassment is shaped by cultural, institutional, legal, political and economic factors. Cultural factors concern

the journalistic traditions within a specific country. That explains why for example newspaper coverage on sexual harassment in the US may differ from Germany. Institutional factors refer to the power different institutions have in the news making process. Legal factors concern laws around sexual harassment but also possible restrictions to journalistic freedom. Political factors refer to different political realities of the country but also the political background of the specific newspaper. Lastly, economic factors concern possible dependencies of investors or advertising that may influence the news coverage (Saguy 2002).

More recently, McDonald and Charlesworth (2012) concluded that news media primarily cover sexual harassment cases with scandalous accusations and “overtly sexualized conduct” (p. 95) involved. Accordingly, Easteal et al. (2015) state that violence against women still only makes it to the news when particular happenings concerning homicide of a partner/family, intimate homicide, high-profile persons of interest being involved in sexual assault or legal matters concerning sexual harassment or assault is involved. Additionally, McDonald’s and Charlesworth’s (2012) study within four Western countries (US, UK, Canada and Australia) showed that the media generally still present sexual harassment as an individualised problem, as the misconduct of an individual rather than as symptomatic to gender inequality or a systemic issue. According to Easteal et al. (2015), this sets a frame that leaves the underlying social causes out of the picture. The representation of perpetrators and victims to sexual harassment in large parts of the Western media creates a loaded image of their respective rights and responsibilities (Easteal et al. 2015). Easteal et al. (2015) hold the opinion that the way the press creates narratives about feminist topics such as sexual harassment may hinder feminist endeavors of protecting women from (sexual) violence and creating justice for them. The authors hold the opinion that social media in fact has the potential to challenge the dominant representation and framing of sexual harassment and other feminist matters but at the same time, the internet can also be used to enhance the dominant discourse on violence against women (Easteal et al. 2015).

Interestingly, I was not able to find a lot of recent literature on news coverage of sexual harassment. Already in 1996, Sev’er investigated why sexual harassment made it to the newsrooms but not into the mainstream academic journals, only into gender-based journals. According to her, this is due to 1) the researchers’ androcentric biases and their fear of claim-making, 2) gatekeeping by editors or reviewers or 3) not wanting to be published in mainstream journals (Sev’er 1996).

Social Media And Hashtag Activism

Nowadays, groups often build their shared moral base through different media channels. As Wilson (2018) puts it, “[m]edia outlets from social media to newspapers can play a pivotal role in developing a shared moral understanding” (p. 34). Simultaneously, the number of people acting as an attentive audience, an audience that is publicly aware and engaged, is increasingly growing (Wilson 2018). According to Kingdon (2003), the media tend to affect the public’s agenda by expanding the initiatives someone else or another media outlet started instead of starting movements themselves. Researchers agree on the fact that the coverage of social movements can (positively or negatively) influence the related mobilization (Coy 2013). Accordingly, Wilson (2018) thinks that media outlets like newspapers have the power to enhance or stop social movements just through covering them or not. Without news media coverage even a movement like #MeToo could have had difficulties to find the right window of opportunity to go viral. “[T]he internet is a major source from which people obtain new information” (Hong 2012, p. 69). Many people even read newspapers online, for example on their smartphones. Additionally, social media have an increasing impact on what newspapers and other media cover as news. Those news are often shared online via tweets on Twitter or posts on Facebook (Hong 2012). Therefore, many newspapers make use of social media nowadays. Additionally, online news is the most important information source today (Newman et al. 2017).

With the importance of social media and hashtags for social/political movements, the term hashtag activism arose. Hashtag activism “happens when large numbers

of postings appear on social media under a common hashtagged word, phrase or sentence with a social or political claim” (Yang 2016, p. 13) and is a “discursive protest on social media” (p. 13). Hashtag activism is important for awareness-raising (Eagle 2015). #MeToo is also a feminist hashtag which leads us to the notion of feminist hashtag activism (hashtag feminism) which belongs to the broader framework of digital feminist activism. Baer (2016) summarises digital feminist activism as a “departure from conventional modes of doing feminist politics, arguing that it represents a new moment or a turning point in feminism in [several] ways” (p. 18). Additionally, digital feminism is seen as “engaging substantively and self-reflexively without issues of privilege, and access” (Baer 2016, p. 18). Hashtag activism turns into hashtag feminism when the hashtag concerns and intends to fight for gender equality (Clark 2016). Hashtag feminism even has become a “powerful tactic for fighting gender inequities around the world” (Clark 2016, p. 788).

Other prominent examples of feminist hashtag activism are #YesAllWomen from 2014, where women worldwide tried to draw attention “to the ubiquity of sexism, misogyny, and violence against women” (Baer 2016, p. 17), which in Germany was combined with the hashtag #Aufschrei and documented cases of everyday sexism (Baer 2016); #WhyIStayed, where women explained why they stayed with their abusive husbands and how they finally cut the strings (Clark 2016) and #EverydaySexism, where it took just a few days to collect a high number of posts from women sharing their experiences with sexual harassment in their everyday life (Eagle 2015).

Further exploring the field of hashtag activism, we come across celebrity hashtag activism. Celebrity hashtag activism occurs when a popular, well-known person, for example an actor/actress adapts and uses a hashtag to give it more attention (Duvall & Heckemeyer 2018). In November 2014, a 12-year-old boy was shot by a police officer while playing outside with a toy gun. It was not before songwriter and producer John Legend published a tweet on Twitter that the matter reached broader public attention. Legend also engaged in the #BlackLivesMatter

campaign, a hashtag campaign that seeks to bring justice to black people who still are systematically oppressed and experience brutalisation, especially concerning the US-American judicial system (Duvall & Heckemeyer 2018). Joined by many black celebrities, #BlackLivesMatter went viral and even was referred to in the presidential elections of 2016 in the US: This is only one example of celebrities, especially of those representing systematically oppressed ethnic groups or minorities, adapting a politically or socially important hashtag, help it to go viral and thus receive more public attention and importance. Just like actress Milano did when using the hashtag #MeToo to demonstrate the magnitude of the problem of sexual harassment and abuse (mainly) against women.

The German Perspective

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment naturally is not a new German phenomenon. However, in most Western countries, news media tend to present sexual harassment as an individual problem rather than as a systemic issue or as embedded in the general problem of gender inequality (McDonald & Charlesworth 2013): Media often frames sexual harassment as being the product of a shared responsibility of offender and victim (Easteal et al. 2015). Changes concerning politics or legislation to protect victims from sexual misconduct took longer in Germany than it did in other countries (Zippel 2006). Strikingly, within the EU sexual harassment was less likely to be seen as an issue of concern even though women in the member states reported roughly the same amount of sexual harassment at work as women in the US (Zippel 2006).

Within the European Union, EU law defines sexual harassment as

“where any form of unwanted verbal, non-verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature occurs, with the purpose or effect of violating the dignity of a person, in particular when creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment” (European Parliament 2017).

The German Antidiscrimination Law captures the following legal definition for sexual harassment:

“Sexual harassment shall be deemed to be discrimination in relation to Section 2(1) Nos 1 to 4, when an unwanted conduct of a sexual nature, including unwanted sexual acts and requests to carry out sexual acts, physical contact of a sexual nature, comments of a sexual nature, as well as the unwanted showing or public exhibition of pornographic images, takes place with the purpose or effect of violating the dignity of the person concerned, in particular where it creates an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment” (European Institute for Gender Equality; EIGE 2018).

This definition was added to the “Protection of Employees Act” in 2006 because it was lacking any definition of sexual harassment (EIGE 2018). In 2014, the EU Council decided that sexual harassment in all private or public spheres within the EU falls under direct social violence, together with offenses like rape, sexual assault (EIGE 2018). Since then, online harassment falls under direct gender-based violence against women, too (EIGE 2018). However, in German law sexual harassment is only a separate criminal offense since 2016 when it was added to the official criminal code (Strafgesetzbuch, StGB) (Hörnle 2017). Until then, sexual harassment fell under insult (Art. 185 StGB), defamation (Art. 186 StGB) or intentional defamation (Art. 187 StGB).

Nonetheless, the chapter on sexual offenses was not completely re-written or set up in a different way. They only added some parts to the already existing division. Since then, Sect. 184i StGB defines what sexual harassment is and what kind of punishment is to be expected. Additionally, Sect. 184j StGB extends the definition to sexual harassment performed from within a group, making it possible to prosecute people who helped offenders to harass a person (Hörnle 2017).

Contrarily, the US were the first country to consider sexual harassment as sex discrimination and that to this day has the most elaborate legal measures against

it (Zippel 2006). According to the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC; 2018), sexual harassment is defined as

“unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature constitute sexual harassment when this conduct explicitly or implicitly affects an individual's employment, unreasonably interferes with an individual's work performance, or creates an intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment”.

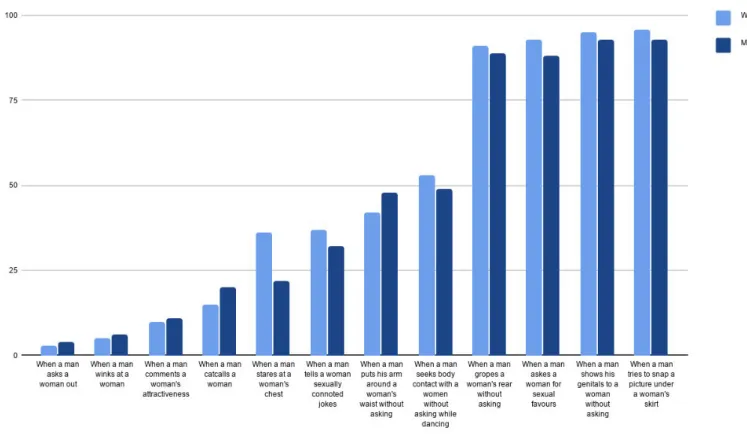

It is agreed upon that sexual harassment is a striking example of an important fight over power, sexuality and gender equality as it combines the problems concerning violence against women, sexuality and workplace equality (Zippel 2006; Carstensen 2016). However, critical voices mention that in practice, it is difficult and limited to pinpoint, identify and define situations and behaviour that is considered sexual harassment (Carstensen 2016, p. 274). For the interpretation of behaviour that might be considered sexual harassment, the context within which it takes place, whether it is formal or informal, plays an important role. Equally important is the relationship between the people involved: Are they formal, informal, close, distanced or even non existent (if one of the people involved is a complete stranger) (Carstensen 2016). The main problem is that if “a behaviour or situation can be defined as sexual harassment from the target’s point of view, the behaviour is subjectively harassment, but objectively the behaviour is not necessarily defined as such” and the other way around (Carstensen 2016, p. 274-275). Women tend to be more likely to perceive a situation/behaviour as sexual harassment than men. However, research has shown that the magnitude of such differences in perceptions differ extensively: There are studies that did not show relevant differences in the perceptions of men and women, while others showed large gender differences in perception of sexual harassment (Blumenthal 1998).

When talking about sexual harassment within this research, I refer to the European, German, and/or US-American definition of sexual harassment as they all consider all verbal, non-verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature with

purpose or effect of violating the dignity of the victim, especially when it creates intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environments (EEOC 2018, European Parliament 2017, EIGE 2018).

Media Framing of Feminism and Feminist Movements in Germany

The German press generally spreads a negative portrayal of feminism (Jaworska & Krishnamurthy 2012). By framing feminism negatively, in a sexualised manner, the German Press creates a stereotypical image of feminism, relating it to leftist politics and a lesbian orientation (Jaworska & Krishnamurthy 2012). Furthermore, the relevance of feminism is frequently questioned within German news coverage or even treated with irony. Feminism in Germany is generally framed as something that is not of high relevance for the general public, not a social movement but rather a topic concerning well-educated middle-class women in academia, literature or arts. However, in general until 2009 at least, feminism received rather little attention from the German news media (Jaworska & Krishnamurthy 2012). But is this still the case in 2018, in the light of #MeToo? The hashtag clearly being a feminist matter provides an interesting case to look into how the German news media frame feminism and feminist movements today.

Social Media And Hashtag Activism in Germany

In 2010, the internet became the second most popular news source in the US while newspapers ranked third; only television was used more (Hong 2012). In Germany, however, the public is more sceptical when it comes to the internet as a news platform. According to a PwC survey, 71% of the German population trust the German public broadcasters ARD and ZDF the most as a source of information about political events. 53% use newspapers and only 23% use social media like Facebook or Twitter (PwC 2017). Only 15% think of the German population considers Facebook as a trustworthy news source and only 10% trust Twitter (PwC 2017). Even within younger German generations (18-29 years), only 23% consider social media like Facebook trustworthy. This might be a reason why it took longer for #MeToo to spread in Germany than in the US. Additionally, in 2016, there were 67.54 Million active Twitter users in the US, ranking first,

whereas Germany did not even rank within the top 10 countries of Twitter users (Statista 2018). According to Davies (2017), Twitter always ran into more difficulties on the German market than in other countries. In 2015, there were only 1.73 Million frequent German Twitter users. 3.73 Million people made occasional use of the platform whereas 48.7 Million people used the platform rarely or never (Statista 2018). Still, Twitter, like Facebook, is a highly relevant social media outlet: Viral hashtags and hashtag activism are not new phenomena in Germany. For instance, in 2013, the feminist hashtag #Aufschrei (outcry) went viral (Baer 2016).

Theoretical Concepts and Analytical Framework

My theoretical framework draws on three theoretical concepts: Media Effects, divided into Agenda Setting and Framing; Representation Theory and the concept of discourse. All concepts go hand in hand to help me answer my sub-questions and ultimately my main research question.

Agenda Setting And Framing

(Mass) media in general have a great impact on public opinion. Potter defines a mass media effect as “a change in an outcome within a person or social entity that is due to mass media influence following exposure to a mass media message or series of messages” (Potter 2011, p. 903). Scheufele (2000), split media effects into three main approaches: agenda setting, framing and priming. He thinks that those three approaches “are related but cannot be combined into a simple theory” (Scheufele 2000, p. 289). Within this study, I will focus on the concepts of agenda setting and framing. According to McCombs and Shaw (as cited in Griffin 2009), agenda setting theory is a two-step theory: first, the media tell the public what to think about (agenda setting) and then the media tell the public how to think about it (framing),

Scheufele (2000) considers agenda setting to be a causal theory: The importance the mass media ascribe to an issue will be the same importance the audience ascribes to the same issue (p. 304). As Cohen (1963, p.13) puts it: “The press may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about.”

The continuous process of framing has the ability to construct social realities (Scheufele 1999). According to Griffin (2009), framing is the “selection of a restricted number of thematically related attributes for inclusion on the media agenda when a particular [...] issue is discussed” (p. 364). It can be divided into frame-building and frame-setting (Scheufele 2000, p. 307). Frame-setting describes how journalists represent a given issue whereas frame-building takes

into account that journalists also are influenced by aspects like “social norms and values, organizational pressure and constraints, pressure of interest groups, journalistic routines, and ideological or political orientations” (Scheufele 2000, p. 307). I consider frame-setting as an especially important notion within this research. By describing sexual harassment but also the men and women involved with a specific choice of words, journalist set a clear frame about how they want the topic to be conceived by the public. According to Easteal et al. (2015), when it comes to sexual assault and other forms of violence against women like harassment, framing can happen on a subtle level, simply by focusing on the victim rather than on the offender, thereby often blaming the victim instead of the offender (victim-blaming).

While “agenda setting refers to the idea that there is a strong correlation between the emphasis that mass media place on certain issues […] and the importance attributed to these issues by mass audiences” (Scheufele and Tewksbury 2007, p. 11), framing is “based on the assumption that how an issue is characterized in news reports can have an influence on how it is understood by audiences” (Scheufele & Tewksbury 2007, p. 11). Following Hodkinson (2017), agenda setting is the “notion that, through their decisions about which issues and events on which to focus, news and other ‘informational’ media can shape the priorities of the public” (p. 281). It thus plays a role, how many articles the different newspapers publish –or do not publish. In talking or not talking about the subjects #MeToo and sexual harassment, they show how much importance attribute to the matter. Within my research project, agenda setting and framing thus help me to understand how SZ and FAZ present #MeToo, how they influence the public with their news coverage and in how far they are influenced by societal standards on the other hand. To summarise, in writing about sexual harassment and #MeToo, the press can make sure that the public considers the topic to be worth talking about and by setting a specific frame, the press can guide the public in how to evaluate the topic. By framing the topic in a certain way, journalist can shape the dominant discourse about it. I will come back to this when talking about discourse in this research.

Representation

The media representation of sexual harassment and other violence against women effects how society in turn perceives it (see also Easteal et al. 2015). Representation theory has its roots in semiology, more precisely in de Saussure’s notion of signifier and signified, where signifier is seen as the means of representation whereas signified is the particular represented concept (Hodkinson 2017). Applied to texts, signifier thus is an actual word, while signified describes the meaning associated with said word. According to Fairclough, representation refers to the words and language used in a specific text to ascribe meaning to people, groups or social events and conditions (Fairclough 1989; 1995a). Within this research project, I suppose that journalists use certain words (signifiers) within their articles on sexual harassment in the light of #MeToo in order to give meaning to their representation of the particular event, thus shaping the dominant discourse about it, but also to describe the subject positions of the men and women involved in the articles. Representations which are produced by for example journalists in newspaper articles can shape the perception of sexual harassment or the men and women involved in #MeToo in Germany (see framing).

While generally speaking, Hall (1997) defines representation as “the process by which members of a culture use language to produce meaning” (p. 61), in media studies, it focuses on “the way media symbolises or stands in for social or cultural phenomena. [It is] often used to refer to the selective portrayal of events, people, groups, cultural trends, social relations etc.” (Hodkinson 2017, p 291). Fürsich (2010) places media representation within the critical cultural paradigm of media studies. According to her, (mass) media representation in fact is more than a identical reflection of reality but much rather mirror the culture, knowledge and meaning of a society within which the media operate (Fürsich 2010). Fürsich points out that representations in the media such as journalism “create reality and normalise specific world-views or ideologies” (p. 115). Representation also has the power to guide the public in a certain direction, away from or towards specific

(political) issues (Fürsich 2010). Following Fairclough (2001), representation is “a process of social construction of practices [...], representations enter and shape social processes and practices.” (p. 2). Additionally, Fairclough (1995a) stresses that media representation has the power to influence how societal groups perceive relationships, knowledge, identities or to summarise, power relations. Through their representation of reality, the media, supported by other players like the government, has the power to influence how the audience understands, interprets and values issues of public concern, such as sexual harassment (Fürsich 2010, Hodkinson 2017).

As Hall (1997) and Fürsich (2010) point out, media representation can create shared societal and cultural meaning. Consequently, limited or under-representation can have a significantly negative impact on decision-making processes and politics. It can even contribute to existing inequalities in society and politics (Fürsich 2010). Women generally look back at a long history of under-representation in media content and institutions: They they barely play a role in decision-making processes within the media industry (Hodkinson 2017). According to Hodkinson, minority groups suffer from under-representation but likewise from stereotypical representation. Women fall under the notion of a minority group as they still are not able to enjoy the same opportunities, privileges and rights as men (Lumen 2018).

When writing articles, journalist can decide what words to use in order to represent the men and women involved or to represent sexual harassment and thus shape the dominant discourse within an article. Therefore, I expect the concept of representation to help me point out how the way sexual harassment and also men and women involved #MeToo are presented in German newspaper coverage, can influence the public’s opinion on the issue. Representation is manifested in text (Hall 1997, Hodkinson 2017) and therefore plays an important role for the text level when looking at CDA.

Discourse

In my research project, I consider the concept of discourse to be important because when analysing discourses, the type of discourse and its specific context play an important role in understanding the underlying power structures and shared meanings of sexual harassment within German society. Also, representation is closely related to discourse. I consider the representation of sexual harassment in online newspaper articles and how they shape the social networks they are placed within but on the other hand are shaped by social influences as the discourse which is relevant for this research. The broad term discourse has different definitions and meanings to it. According to Hall (1997), discourse refers to “a cluster (or formation) of ideas, images and practices, which provide ways of talking about forms of knowledge and conduct associated with a particular topic, social activity or institutional site in society” (p. 6). Jäger (2001) sees discourse as representing “a reality of its own which in relation to ‘the real world’ is in no way ‘much ado about nothing’, distortion or lies, but has a material reality of its own and ‘feeds on’ past and (other) current discourses.” (p. 36), thus discourses are “material means” (Jäger 2001, p. 36) which can also be seen as “societal means of production” (p. 36) that generate societal realities. Discourse can also be described as a social interaction process (Fairclough 1998). Fairclough sees discourse as a form of action and a form of representation within which people can operate with each other or the world (Fairclough 1992). Van Dijk’s (1997) definition of discourse can be summarised as any written or spoken form of language, every event of communication. In his definition, Fairclough (1995a), however, also includes images and any form of non-verbal communication as being able to form a discourse. Additionally, “discourse is always simultaneously constitutive of: social identities, social relations, and systems of knowledge and belief” (Fairclough 1995a, p. 55). Thus, a discourse can never be dissociated from its social context, it is always heavily influenced by social networks and relations. Additionally, Fairclough sees discourse as social practice shaping knowledge, social relations and identities, but which also is

formed by other social practices, structures and systems (Jorgensen and Phillips 2002).

According to Fairclough (1995b) discourses are countable. They can stand in relation to each other. Within newspaper articles, authors can place sexual harassment in different discourses that again shape how sexual harassment is interpreted (McDonald & Charlesworth 2013). McDonald and Charlesworth (2013) place sexual harassment within four different types of discourse: individual discourse (sexual harassment as individual misconduct); systemic discourse (harassment as a trend within certain organisations or industries); gender equality discourse (sexual harassment as a power tool representing gender inequality) and techno-legal discourse (sexual harassment as a matter of legal or technical issues in the context of laws or jurisdictions). Within this research, those different discourses say a lot about how the authors of the analysed articles want sexual harassment to be perceived by the public (framing).

In my research project, agenda setting, framing, representation and discourse are strongly interwoven: How sexual harassment, #MeToo and the men and women involved are represented in word choice mirrors the dominant discourse about sexual harassment in a specific newspaper article. By representing sexual harassment and #MeToo in a certain way, journalist have the ability to set the frame in the public’s perception of the topic and by putting sexual harassment and #MeToo on their agenda and writing about it in the first place, the press can make sure that the issue is perceived as something worth talking about.

Methodology

Choice Of Method: Critical Discourse Analysis

As a main method, I use Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) as established by Fairglough to analyse dominant media representation of sexual harassment in online newspaper articles in the light of #MeToo. In my project, I consider the representation of sexual harassment to be informing the dominant discourse. CDA belongs to the tradition of Discourse Analysis. Most discourse theory is grounded in Foucault’s theory of power relations. According to Foucault (1983), “power relations are rooted in the system of social networks” (p. 224). Discourse Analysis focuses on patterns and structures of language used in texts, always considering the respective sociocultural context (Paltridge 2006). Johnstone (2008) states that researchers in “many fields, with very diverse research projects, make use of discourse analysis” (p. 6). Furthermore, “discourse analysis is the study of language, in the everyday sense in which most people use the term” (Johnstone 2008 p. xvi). Hodkinson (2017) stresses that discourse analysis tries to put individual texts into context, “rather than understanding [them] in isolation” (p.68). There are critical and non-critical approaches to Discourse Analysis. Critical approaches such as CDA focus on the reasoning of why a certain word choice is made to uncover power relations within language and how they have the possibility to shape society but likewise are shaped by society (Fairclough 1995a).

A discourse, according to Fairclough (1989), is a social interaction process, a “mode of action, one form in which people max act upon the world and especially upon each other, as well as a mode of representation” (Fairclough 1992, p. 63). Also, discourses can be distinguished from each other, they can be countable (Fairclough 1995b). For instance, in this paper, individual discourse, systemic discourse, gender equality discourse and techno-legal discourse are considered. The term “critical” in CDA implies “showing connections and causes which are hidden; it also implies intervention, for example providing resources for those who may be disadvantages through change (Fairclough 1992, p.9). According to Coffin

(2001), CDA “gives attention to the dynamic interplay between text production, the text itself, and text interpretation or consumption (p. 99). Fairclough (1995a) describes CDA as a three dimensional analytical framework that studies discursive events and their power to create change. With his framework, Fairclough aims to “bring together three analytical traditions, each of which is indispensable for discourse analysis” (Fairclough 1992, p. 72). The three dimensions Fairclough includes are text, discursive practice and sociocultural practice.

Image 2: Fairclough’s three dimensional model (Fairclough 1992)

The text dimension deals with the meaning and patterns of text, the analysis takes place at word level and the focus lies on linguistics. Text in this case can either be speech, writing, images or a combination of those three elements. CDA is often combined with other research methods (Meyer 2001). To analyse the linguistic text level, I combine CDA with a content analysis to get a first impression of what words are used frequently to represent the men and women involved and what subject positions they offer. I then place the subject positions within the different discourses found in the text. Discursive practice ideally involves the production and consumption of texts and the analysis takes place at text level. However, within the scope of my research, neither production nor consumption of text can be analysed. Therefore, I focus on interdiscursivity instead, which according to Fairclough (1995b) can also be part of discursive practice. According to Fairclough, interdiscursivity describes the relation between different discourses (Fairclough 2003). It is a form of intertextuality that explains how a text or article can refer to already existing discourses (Jorgensen & Phillips 2002). Sociocultural

practice deals with the organisation of and dominant standards in society as well as social structures. The analysis takes place at the norm level.

CDA can help to understand how discourse in news can create certain angles, impressions and worldviews (Hodkinson 2017). According to Coffin (2001), CDA is an approach to language analysis that “concerns itself with issues of language, power and ideology” (p. 99). The interdisciplinary approach of CDA focuses on language as a form of social practice: The study of language according to CDA is not possible without taking social aspects into account (Fairclough & Wodak 1997).

Research Approach And Paradigm

CDA is a traditionally qualitative research method. To carry out CDA, I use an inductive research strategy in which I focus on the context in which my research takes place. According to Blaikie (2010), an inductive research strategy tries to generalise the patterns and structures found during research into theory. I first collect my data from the selected newspaper articles concerning sexual harassment at three different stages, analyse it critically and then continue to create meaning and interpretations from said data. Instead of drawing universal conclusion from my data about the framing of sexual harassment in German online newspapers on text level and interdiscursivity, I try to place my result in the respective sociocultural context and explain it accordingly.

Within this research, I ontologically rely on the idealist assumption that reality derives from the different interpretations, representations and constructions social actors take from the world they live in, instead of assuming that there is just one universal reality: The idealist ontological assumption implies that social reality consists of shared interpretations (Blaikie 2010). Additionally, I place this research within the tradition of two different research paradigms: Interpretivism and critical theory.

Interpretivism

Interpretivists suppose that there is more than one universal reality. Reality is shaped by individuals in groups, their daily interactions and the meanings they produce (Blaikie 2010). Interpretivist researchers try to understand “the world as it is experienced and made meaningful by human beings”, they want to draw upon the meanings and realities individuals create and produce knowledge from that (Collins 2010). Discourse analysis is a typical research method within interpretivism because it analyses “the language in tests and transcripts to highlight the social relationships and cultural values through which individuals make meaning” (Collins 2010). Interpretivism can be linked ontological assumptions. As CDA, according to Fairclough, is the “critical study of language”, it looks at how language on different levels is able to create change (Fairclough 1995a). That is what I do, too. I look at how language patterns and keywords change during the course of news coverage on sexual harassment in the light of #MeToo and how that changed the characteristics ascribed to the men and women involved. Thereby, I can identify shared patterns of language and meaning in the newspaper articles that I interpret according to my internalised norms and values.

Critical Theory

Critical Theory sees reality as socially constructed entities within a social group. It can also be influenced by power relations within the society. Habermas, who significantly contributed to critical theory, thinks that “assumptions embedded in both theoretical constructs and common-sense thinking can determine what will be regarded as reality rather” (Blaikie 2010, p. 100). According to Habermas (1972), emancipation and freedom play an important role within critical theory. Methodologically, it is an emancipatory and critical ideology, where critical research instruments are of high importance (Habermas 1972). As CDA critically studies language causing change (Fairclough 1995a) and does look at particular words and sentences but also the underlying discourses that reinforce the dominant worldviews (Hodkinson 2017), I place it within the paradigm of critical theory.

Data Collection

To apply CDA, Fairclough suggests a problem-oriented, step-by-step approach (Meyer 2001). I applied Fairclough’s CDA to a small sample of 19 newspaper articles from two major German newspapers on sexual harassment related to the #metoo movement. I chose SZ and FAZ as they have a similar circulation (Statista 2017). They also are well-known for being sophisticated and of high quality. Germany’s biggest newspaper, BILDZeitung on the contrary is a tabloid newspaper which is why I did not consider it for my analysis. I wanted to gather information from two similar newspapers qua circulation that however have different political views to obtain a broad image of the German news media. I wanted to compare the articles from when the allegations against Weinstein came to light in the beginning of October 2017, to the time when Milano tweeted #MeToo and finally to the time when the accusations against Dieter Wedel first occurred in January 2018. To choose my articles, I sampled at two stages. I first searched the archives of both newspapers using the terms “Weinstein”, “#MeToo” and “Wedel”. Concerning reading the different articles and choosing the ones I wanted to analyse for this paper, I was confronted with the difficulty of both newspapers only allowing the readers access to a limited amount of articles for free. I had to arrange trial subscriptions and pay for some articles to analyse sufficient articles. To narrow down my research and to keep the articles close to the important incidents, I decided to mainly focus on three phases:

1. The first three days after the infamous article on Weinstein was published in the NYT on October 5th, 2017: Four articles, two published in SZ, two published in FAZ

2. The first three days after Milano posted #MeToo on Twitter on October 15th, 2017: Eight articles, six published in SZ, two published in FAZ 3. The first three days after ZEITmagazin reported the allegations on Dieter

Wedel on January 3rd, 2018: Seven articles, four published in SZ, three published in FAZ

Data Analysis

I divided my data analysis in two sections: Text level and discursive practice put together, and social practice.

Text Level and Discursive Practice

To analyse the text level, I looked at the linguistics: I read 19 articles and filtered them on the basis of subject positions representing men and women involved reflected in the choice of words (nouns, adjectives/adverbs and verbs). I put all articles in tables (see appendix) and ordered them according to their date of appearance. In the tables, I displayed the headlines, the newspaper I chose them from and the link to the subsequent article. In a different table, I put the date, the newspaper, the headline and a number of characteristics and describing words filtered from the article. To guide my interpretation of the subject positions, I set up questions which I tried to keep in mind while going through the texts:

1. What are the words used to represent women? 2. What are the words used to represent men?

3. Are there similarities/differences between SZ and FAZ?

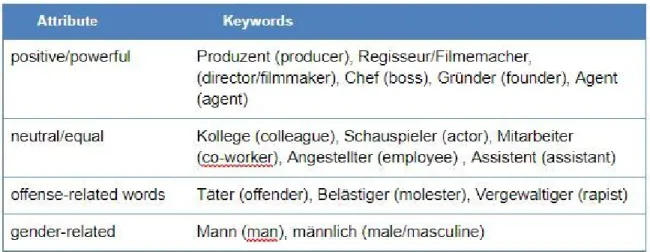

According to Fairclough (1995b), it is not only important to look at the words that are used but also at those that are not. That is why I focus on positive/powerful, neutral/equal, weak/less powerful and gender-related words and how they are used or not used to create subject positions for the men and women involved. By this, I want to figure out how the dominant discourses are set up linguistically. Doing so, I assume that there can be different dominant discourses that can change or stand in relation to each other.This is what Fairclough labels

“interdiscursivity” (1995b). By working out the dominant discourse of each article, I hope to get insights in any development of discourses throughout the course of my research. According to McDonald and Charlesworth (2013) different discourses can present sexual harassment as

2. systemic discourse: a systemic issue within an industry, in this case the film industry

3. gender equality discourse: a matter of gender inequality 4. techno-legal discourse: a matter of legal clarification.

Additionally, I focus on the nodal points of the articles and how they mirror the dominant discourses.

Social Practice

To analyse the social practice, I look at the history and development of sexual harassment in Germany and how it used to be displayed in the media. I also take the German legal definition end developments of sexual harassment into

consideration. With this, I aim to determine how one can understand the discursive formations established in part one of my analysis in the context of hegemonic ideas about what constitutes sexual harassment in Germany. To better

understand what constitutes sexual harassment in Germany, I additionally rely on a literature research, taking academic journals, legal documents, official

governmental websites and statistics into account.

Ethics

The most important ethical guideline for every researcher is to avoid plagiarism. Therefore, I made sure to correctly reference and quote all my sources, online and offline, academic and popular. Additionally, I as a researcher have to make sure what the purpose of my study is as I did in the introduction of this paper (Swedish Research Council 2017).

For my research, I heavily rely on the online archives of SZ and FAZ to access the analysed articles. According to the AoIR Ethics Working Committee (2012), research that “employs visual and textual analysis, semiotic analysis, content analysis, or other methods of analysis to study the web and/or internet-facilitated images, writings, and media forms” (p. 4) falls under the umbrella term of internet research which has to consider special ethical guidelines. Concerning my online

data collection, I had to make sure to have the right authorisation to use the websites of SZ and FAZ and that the articles I used were officially published on their respective websites. I also had to consider copyright restrictions because it might not be permitted to for example take screenshots or images without the permission of the copyright holder (AoIR 2012).

Analysis and Discussion

I present my analysis in two main parts, mirroring Fairclough’s three dimensions but summarising text level and discursive practice under one headline. To answer my research question, I looked at three different phases within the recent debate on sexual harassment in Germany in the light of #MeToo. Phase One was when the NYT published the article on Weinstein, Phase Two is when Milano posted #MeToo on Twitter and Phase Three is when ZEITmagazin their revealing article on German director Wedel. I decided to take the first three days after each incident into account to narrow down my research. First, I went to the online archives of my chosen newspapers, SZ and FAZ, and searched for the terms Weinstein, #MeToo and Wedel. Until May 10th, 454 articles could be found in the online archive of SZ when searching for the term “Weinstein” (Süddeutsche Zeitung 2018b). Whereas the online archive of FAZ only displayed 176 articles for the same keyword (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 2018a). In SZ, there were 427 articles tagged with #MeToo by May 10th, 2018 (Süddeutsche Zeitung 2018c). The archive of FAZ, however, displays 103 results for the same search word (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 2018b). By May 10th, SZ published 137 articles on the topic “Wedel” (Süddeutsche Zeitung 2018d), while in the archive of FAZ 30 results could be found (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 2018c). Within the first three days after the NYT told their readers about the allegations against Harvey Weinstein, both SZ and FAZ released two articles on the matter. After Milano tweeted #MeToo, SZ published six articles on the matter while FAZ only released two. Finally, concerning the Wedel affair, SZ released four articles and FAZ three. According to Agenda Setting Theory, this shows that generally, SZ considers the issue of sexual harassment in the light of #MeToo of higher importance than FAZ does simply due to the fact that SZ published more articles on the matter and thus apparently found it more important to talk about it.

Text Level And Interdiscursivity

When I first went through the articles, I noticed that often, the authors offered more powerful subject positions to the men involved than to the women. To test my assumption, I also looked at how often more powerful positions were associated with women. That made me look at the following representations when looking at the articles for the second time.

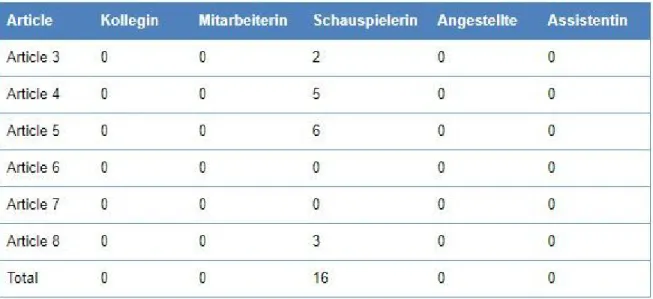

Table 1: Female representations

Overall, women involved in the articles were mostly represented as clearly were “woman” (105 times) and actress (69 times). Surprisingly, the word victim or a similar subject position was only mentioned 17 times in the course of 19 articles in total. Additionally, it seems striking that the authors often felt the necessity to mention that the women involved were young (ten times), especially in SZ (nine of ten times). Strong subject positions were only occasionally ascribed to the women involved, above all the term “feminist” (five times in total).

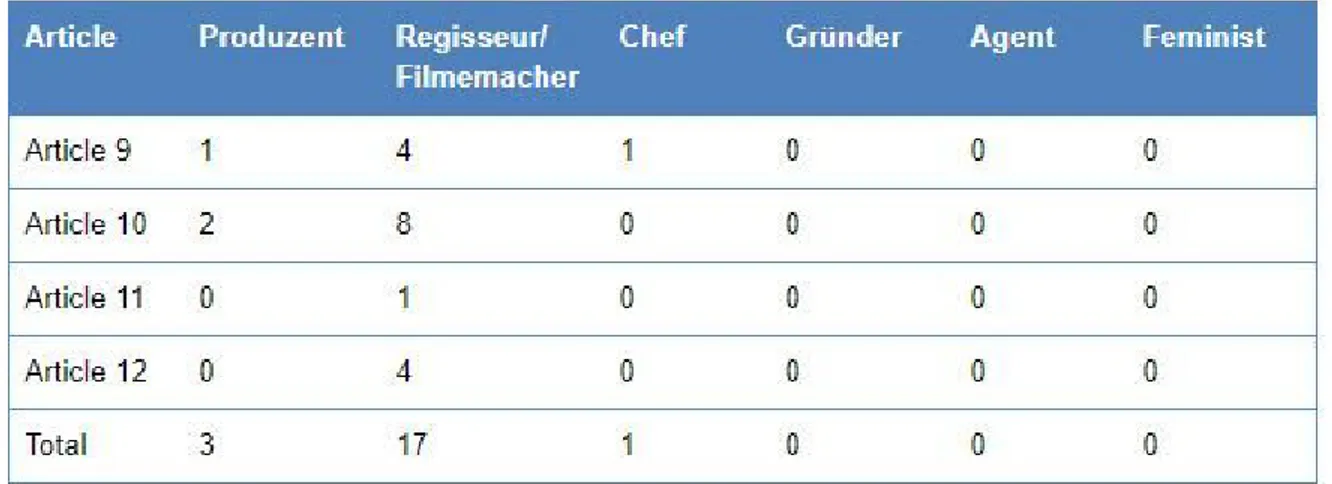

Aside from Weinstein (97 times) and Wedel (94 times), the men involved mostly were represented in powerful subject positions like producer (27 times) and director (27 times). The attribute “man” was mentioned 27 times, too. Surprisingly, men were only represented as “offender” six times in 19 articles, only one of the mentionings being published in FAZ. None of the articles called the men involved molester or rapist.

Strikingly, the linguistic focus in the articles often concentrates on the women involved rather than on the men involved. Even though Weinstein was the main subject to two of the analysed phases (Phase One and Two) his name was not mentioned as often as the word “woman”. The authors of the articles talked about “woman/woman” more than three times as much than they talked about “man/men”, strongly indicating how sexual harassment also in the light of #MeToo is a subject that concerns women rather than men, even though men mostly are the ones actually performing the harassment. The subject position “offender” was barely used it all. This again shifts the focus on the women involved rather than on the men involved which sets an important frame in the light of #MeToo, putting women in the spotlight, being victim to sexual harassment, not the men hurting them. Additionally, if the women involved were not represented as “woman”, they were often described as “actresses”, as subordinated to the men involved, being “producers” or “directors”. And yet, the male counterparts were not mentioned as often as the females (69:54). This again how women are represented in the my chosen articles about sexual harassment in the light of #MeToo more often than men are even though, they are the victims to it. Focusing on the women can

create a feeling of mutual responsibility, blaming the women at least partially for what happened to them.

Additionally, I looked for the dominant discourses on sexual harassment in the single articles, how they are framed and reflected in the nodal points of the articles. In accordance with McDonald and Charlesworth (2013), I looked at the interplay of the following discourses: individual discourse: harassment as an individual aberration; systemic discourse: harassment as a systemic issue within the (film) industry; gender equality discourse: harassment as a matter of gender inequality; and techno-legal discourse: harassment as a matter of legal clarification. Within the articles, I did not only look at how the discourses are set up and reflected linguistically but also how the nodal points of every article emphasised the dominant discourse it drew on.

Individual Discourse

Within the individual discourse, sexual harassment is represented as the individual misconduct of a person, as a behaviour that has nothing to do with systemic or gender-related structures and tendencies. In total, six articles made use of this discourse.

Phase One:

In Phase One, SZ published their first article “Hollywood: Sexual harassment allegations against Weinstein” on October 6th (Süddeutsche Zeitung 2017a) where the headline already indicated that sexual harassment is associated with Weinstein not with men in general or with men in the film industry. By focussing on what Weinstein did and how he reacted to the allegation, the author presents sexual harassment as the misconduct of a single person, Harvey Weinstein in this case. Therefore, the dominant discourse in this article is sexual harassment as individual aberration. It was the only one of two times during the scope of my study that SZ framed sexual harassment as individual misbehaviour.

FAZ on the other hand framed sexual harassment as individual misconduct in most of their articles during the time of my research. Two of them were published in Phase One. Those were also the only two articles to be published within the first three days after the allegations against Weinstein came to light in FAZ. On October 6th, FAZ published the article “Maker of ‘Pulp Fiction’: Film producer Weinstein accused of sexually harassing women”. Following the article, the powerful producer, who produced movies like The King’s Speech, faces sexual harassment allegations from several women. Weinstein apologised for his misbehaviour which he says is a result from being raised and socialised in the 60s and 70s. He is now seeking help from therapists (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 2017a). In their article, by focusing on Weinstein’s misbehaviour against woman, FAZ frames sexual harassment as his individual misconduct because there is no indication that there might be similar cases. The case Weinstein is presented as a single entity. Sexual harassment in this case thus falls under individual discourse. In their second article, “Sexual harassment allegations: Production company has investigations carried out against Harvey Weinstein”, published one day later, the author talks about how Weinstein, a successful Hollywood film producer, faces serious sexual harassment accusations from over 30 years after an article was published in the NYT. Most of the suspected victims are then young women hoping for a career in Hollywood. Weinstein apologised for his misbehaviour and now wants to take a break to fight his “demons”. His company which he founded and runs together with his brother Bob, supports his break and initiated own internal investigations on the matter (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 2017b). Within this second article, FAZ again described on how Weinstein as a person harassed young women and actresses. Thus, again, the description of sexual harassment in this article falls under individual discourse because there is no indication of the allegations being a sign of a bigger societal problem.

Phase Two:

In Phase Two, SZ published one article framing sexual harassment as individual discourse on October 16th. According to the article “Investor might buy Weinstein Company”, #MeToo developed and gained momentum, resulting in severe

financial trouble for the Weinstein Company after allegations of sexual assault against Weinstein came to light. Now, a potential investor should save the company. Weinstein, co-founder of the company, was already fired due to the accusations (Süddeutsche Zeitung 2017c). While this article focused on the financial situation of the Weinstein company which Weinstein co-founded with his brother, it still talks about sexual harassment as well. Even though the article mentions Milano’s Twitter post and how many women reacted to it, it still frames sexual harassment as individual discourse by focusing on what Weinstein did wrong and what other accomplishments he has achieved in his life. Additionally, the article does not mention the motives for sexual harassment or the underlying power structures.

Phase Three:

In Phase Three, FAZ published three articles in total. In two of the three articles sexual harassment was framed as individual misconduct. In the article “#MeToo in Germany: Actresses accuse Dieter Wedel of sexual assault”, published on

January 3rd, the author describes how several women accuse Wedel of sexual harassment, abuse and even rape while former co-worker support the accusations by reporting Wedel’s verbally abusive workplace behaviour. In a written statement, Wedel denies all allegations. He only admits to being loud, harsh and strict on set, but never with sexual intentions (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 2018d). In this article, the author solely focuses on the case Wedel, describing him as a

successful player in the German film industry, therefore it falls under individual discourse as the author does not indicate any systemic structures behind the allegations Wedel faces.

On January 4th, FAZ released the article “Mayor of Bad Hersfeld: ‘How Wedel is treated reminds me of a witch hunt.’”, within which the author describes how Thomas Fehling, mayor of Bad Hersfeld, supports Dieter Wedel while he faces severe accusations of sexual misconduct as the first German name in the film industry who is being called within the #MeToo debate after ZEITmagazin published an article about him. In Bad Hersfeld, Wedel works as director of a