Towards Merging Digital Technology with Traditional Acting Methods

Support for Training Performers with Multi-Modal Analytics SystemAuthor: Shima Ghari

Media Technology, Malmö University Supervisor: Daniel Spikol

2 Abstract

Society is relying more and more on computer-generated information due to the online abilities provided by current information and telecommunication technologies in a variety of ways such as social networks, learning systems, shopping, quality-of-life improvements. Multimodal Learning Analytics (MMLA) is a method in learning analytics research that makes it possible to capture large amounts of data on human activity. This study aims to provide a deeper

understanding of physical movement challenges for training performers in open-ended, practice-based learning settings. Moreover, it discusses how multi-modal analytics systems can provide support for performers. This study identifies ten important requirements that a prototype should have in order to fulfill the performer’s needs. These requirements are implemented in a low fidelity prototype that provides modeling movement followed by Laban Movement Analysis theory, capture user data with MMLA tools, and provide personalized feedback. The results indicated there is a potential within the usage of a multi-modal system to support and improve the motor skill learning process through personalized help and feedback.

3

Acknowledgments

Foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Daniel Spikol for all his advice and

encouragement throughout my time writing this paper. He has inspired me in many ways and no words can describe how much I am thankful for all our meetings and conversations.

Furthermore, I would like to thank the members of “On Stage Skåne” and “Orizon.Art” for their time and participation in this research. My sincere thanks must also go to Inna Syzonenko, PJ Andersson, and to my best friend Yevgen Pronenko for all of their encouragement and support during the data collection of this study.

4

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 - Introduction: 5

1.1 Purpose of the study 7

1.2 Limitations 8

1.3 Personal motivation 8

1.4 Thesis outline 9

Chapter 2- Background: 10

2.1 Laban’s Dance Theory 14

2.2 Human-computer interaction 18

2.3 Multimodal Learning Analytics 19

Chapter 3 - Methodology: 21 3.1 Research Design: 22 3.1.1 Human-centered design 22 3.2 Data collection: 26 3.2.1 Participant Observation 26 3.2.2 Semi-Structured Interviews 28 3.2.3 Survey 28 3.3 Prototype: 29 3.4 Analysis 30 3.5 Ethical Considerations 30

Chapter 4 - Context of use 31

4.1 Phase I- Context of use (Observation) 31

4.2 Phase II- Context of use (Interviews) 42

Chapter 5- Requirements Specification Phase III 45

5.1 Finding form observation sessions: 45

5.2 Findings from the interviews with beginner and expert actors (Part one): 48 5.3 Findings from the interviews with directors, acting, and dance coaches (Part two): 53

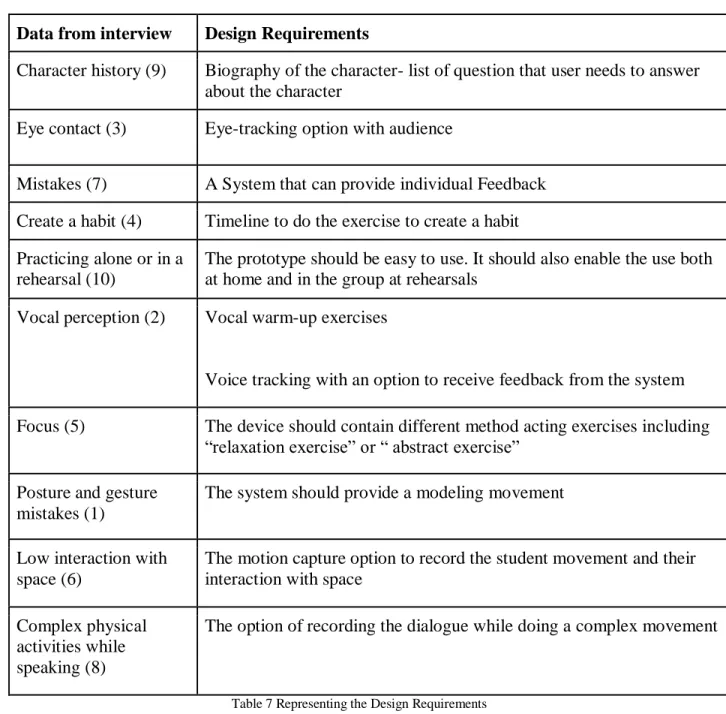

5.4 Design requirements 58

Chapter 6- Create a Design Solution- Phase IV 61

6.1 Design Ideas Part One: 61

6.2 Design Ideas Part Two 63

Chapter 7- Evaluation of the Design Solution- Phase V 72

7.1 Findings from the low fidelity artefact test 75

5 8.1 Reflection 82 Chapter 9- Conclusion 84 9.1 Future work 85 References 86 Appendix 1 91 Appendix 2 92 Appendix 3 93 Appendix 4 94

List of Figures

Figure 1 25 Figure 2 26 Figure 3 38 Figure 4 41 Figure 5 41 Figure 6 62 Figure 7 65 Figure 8 66 Figure 9 67 Figure 10 68 Figure 11 70 Figure 12 72 Figure 13 75 Figure 14 77 Figure 15 77 Figure 16 78 Figure 17 79 Figure 18 80List of Tables

Table 1 36 Table 2 45 Table 3 48 Table 4 54 Table 5 48 Table 6 58 Table 7 606

Chapter 1 - Introduction:

Humans have two separate memories. “Obviously there is a memory of the body apart from conscious recollection: Through repetition and exercise, a habit develops” (Fuchs, 2012). The learning-by-doing approach is something that training procedure on motor skills acquisition can follow (Reigeluth et al., 1999). This interaction between action and perception is called enactive knowledge (Bruner, 1966) which supports the transmission of information acquired through action and can feed the user back through different senses. These include many human activities dancing, handwriting/drawing, improving the technique for acting and sports, etc. (Soderstrom & Bjork, 2015). In order to perform these actions in a controlled manner, the performer needs to practice them repeating the movements required until a suitable manner to carry them out is learned, that is, he/she needs to practice their conscious body movements (motor skills). Therefore, it is essential to direct and correct the performer’s movements until his/her best possible movement is achieved. In fact, because each performer has different motor skills, physical abilities, and goals, this practicing should be done in a personalized way. For instance, in the case of acting, it is important to have personalized motor skills in order to build a

character. The British actor Ian McKellen says: “Acting is a very personal process. It has to do with expressing your own personality and discovering the character you're playing through your own experience - so we're all different” (Ian McKellen, 2006). This means that each performer should have the support and advice that is most suitable for his/her individual characteristics in his/her own situation, which might vary from the support and advice needed by another

performer in a different situation. In order to obtain the right psychomotor support, user data- driven methodologies are necessary (Santos, 2016). A method to provide these new

7 difficult problems in rich social-learning environments. Also, proper support and feedback for students in these learning environments are necessary for their final results. At the same time, providing proper support for each learner is a very challenging task for teachers. Usually, students do not notice motion errors themselves and they need to have objective guidance from experts (Iwasako et al. 2014). Conventionally, the coaches are used to provision motor skills. A human instructor usually uses methods such as physical supervision for the student’s limo movement, verbal guidance, using a mirror to let students observe themselves, etc. (van der Linden et al. 2011). This is why training approaches need high skills in distinguishing how the movement performed matches the ideal one, particularly when movements are difficult and can be done at different levels. However, when a teacher tries to give feedback, 1- might not be able to observe all those important variables that characterized the movement, 2- cannot continue the equal level of concentration for a long time and 3- might not be able to give collective feedback.

Multimodal Learning Analytics (MMLA) is a method in learning analytics research that makes it possible to capture large amounts of data on human activity (Worsley, 2014). The aim of MMLA approaches is to combine several information processing technologies such as computer activities, wearable sensors, and cameras, eye tracking, gesture sensing, text mining, image processing, etc. In this study, the use of MMLA can help to generate specific data about what occurs when students are involved in different activities. Using this method can help the author to have insight into the step by step progress of the performers' activity and their social interaction. (Blikstein & Worsley, 2016).

The initial focus in this paper is to understand and design the needs for training actors and acting coaches, however, as actors are exploring movement through dance and improvisation

8 techniques, this study makes use of theories from dance methods as well. Chapter 2 provides and discusses these methods in sufficient detail.

1.1 Purpose of the study

Performers express themselves in many ways. Visual cues such as body orientation, facial expressions, and gestures often work as signaling mechanisms and provide a lot of information to the receiver during social interactions. The emphasis of this research is on the performers’ physical movement experience. However, the question remains about how performers might experience physical movements. In order to answer this question, we must first answer what performers consciously express through movements? What do they unconsciously

express? How do they interact with their surroundings? How does the physical environment influence their movements? This study aims to provide a deeper understanding of physical movement challenges for training performers in open-ended, practice-based learning settings. Moreover, it discusses how multi-modal analytics systems can provide support for performers. The cases explored in this study include method actors. Below research questions will be addressed as a guideline for this study in order to accomplish its purpose:

Main question:

RQ1: What are the design requirements for developing a multi-modal analytics system that supports performers (stage actors) practicing new methods and acting techniques? A sub-question also explores the following:

RQ2: How can a low fidelity prototype of an MMLA system create a common understanding between different stakeholders including performers, coaches, and directors?

9 In order to answer these questions, this study makes use of empirical studies, theories, and design as different phases of the research development, as each approach offers different potentials to explore the research questions.

1.2 Limitations

The aim of this study is to explore only the physical movement challenges that occur when actors are involved with training performance and therefore, there is not any focus on psychological, emotional, and social facts. At the same time, the arguments provided in this study are limited to two rehearsals/workshops that might not provide a full image of the predictable results.

Moreover, the primary focus of this study was on stage actors to improve their performance in theater and therefore, the findings from this study might not work for other performers such as camera actors as the prototype has been tested only with "on stage" actors and none of the participants had an experience of acting for the camera. The prototype introduced in this study aims to understand and provide a methodology for any future technology. The prototype has been tested under a simulated environment as designing technology with MMLA was out of the scope of this study.

1.3 Personal motivation

This section discusses the factors that motivated the research undertaken in this study. In order to deepen my knowledge in theatre and to improve my acting skills, I attended several acting courses in Malmö, where I noticed that body movement techniques are very important and sometimes very hard to learn. One of the greatest and most common challenges I and the other students faced at first was learning to move our bodies and to share our advice/feedback with other students on how to overcome challenges. Apart from physical warm-ups, an actor/actress needs to learn using his/her body to show the environment, emotion, character, and story. I have

10 found my inspiration for writing this paper from a conversation I had with my previous acting teacher, who teaches the subject of “body movement techniques” in different acting classes.

The conversation we had was around the topic of proper body posture and how technology can support the relevant aspects of physical movement within method acting techniques. In this study, I have been able to combine my passion with my educational background, as an amateur actress, and as a designer. My experiences from different acting courses and performing on stage, as well as my educational background in multimedia design, have therefore played a major role in this study.

1.4 Thesis outline

Chapter one starts with a short introduction which explains the general idea behind this research. The second chapter describes the background of the study and its theoretical frameworks.

Chapter three describes the methodology and the design process undertaken in the study.

Chapters four and five include the design findings and results. Chapters six and seven introduce a design solution and evaluation of the solution. Chapter 8 discusses the findings of the study, and finally, chapter 9 contains conclusion and future works.

11

Chapter 2- Background:

Nowadays the notions of the embodiment are often referred to as important features of the design. These notions are mostly discussed from a phenomenological standpoint (Dourish, 2001; Svanæs, 2000). The phenomenological approach argues a more holistic outlook on human, emotional, physical, and cognitive aspects. Richard Shusterman has proposed an approach to the aesthetics of the human body called somaesthetics (Shusterman, 2000), which have been

suggested as valuable approaches in the area of user experiences and interaction design (Kallio, 2003; Petersen et al 2004). In phenomenology, the borders within mind and body are detached and the body as it exists and experience form the foundation of human existence. In the case of acting onstage, the phenomenological approach locates the actor's physical existence at the focus of the stage event. Gamer (1994) in Bodied Spaces: Phenomenology and Performance in

Contemporary Drama states that theater forms within the actor's body on stage.

According to Adam Bailey (2015) who is a teacher of “Alexander Technique”, indicated that the human may feel huge emotions and use the memory from the past when they first start physical techniques. In this case, the person might need an ability to deal with the movement as it appears, especially when the movement recalls a trauma. A similar perspective is defined by Siobhan Fink (1990):

“physical expression through movement facilitates the evocation of unconscious memories, fantasies, and primitive ways of coping with traumatic experiences” (p. 18). Fink's emphasizes the importance of attention on training performers’ wellbeing in any rehearsal or acting movement classes. Schechner (1985), argues that actors’ physical learning process should first happen in the body and that all those psychological patterns related to the mind must

12 be considered afterward. Later, in 1992, the American voice theorist Kristin Linklater also

supported the importance of the actor re-connecting towards the “sensory apparatus of the body”. “This is quite different from not thinking. It is rather, whole-body thinking, or

experiential thinking, or incarnated thinking, or the Word made Flesh dwelling among us” (Linklater, 1992, p. 14).

Gamer, Schechner, Bailey, and Linklater all supporters the importance of the “whole-body” concept in the acting classes or rehearsals.

One of the well-known acting techniques that are in use in almost every acting class is the Stanislavsky method. Konstantin Stanislavsky (1936/1980) was a Russian actor and director, who established the Moscow Art Theatre (1898). He was the first acting coach truly involved with actors’ training and the psychophysical part of acting (Hodge, 2000). Stanislavsky

developed his perception of actors’ training and demonstrated a change from an emphasis on the psychology of the actors to the importance of the body of the actors (Meyer, 2001). He began to realize that emotion has no meaning without physical movement and saying that:

“in every action there is something psychological and in the psychological, something physical” (Stanislavsky, 1950/1988, p. 75).

He also mentions that solely focussing on feelings is not always a useful way of using emotion. “An actor always remains himself whatever his real or imaginary experiences may be. He must, therefore, never lose sight of himself on stage” (p. 54)

He then adds, “the moment an actor loses sight of himself on stage, his ability to enter into the feelings of his character goes overboard and overacting begins” (Stanislavsky, 1950/1988, p. 54).

13 Stanislavsky came to understand that there is no place for a machinelike gesture on the theater stage, so he believed that the actor’s body required training, for a better posture, and also to make elegant movements.

Similar to the phenomenology and whole-body approaches, Suzuki highlights the importance of the space with the actor's body. Suzuki in his notes (1979) "Body, Space,

Language" explained the experience of directing a show that made him look at the actor's body as the most important factor when training for new physical activity. He had to trust the physical energy reflecting from the existing body of the actor. He mentioned that the space for their rehearsal was small (above a coffee shop) and for the first time he discovered that the physical energy alone allowed the theater to be available to a group of people. Alongside, the whole-body approach, the use of kinaesthetic sense is an important factor that training performers must be aware of when learning new physical movement.

Besides the movement of the present moment, one of the major contributors to the core image can be kinaesthetic memory. A kinaesthetic memory flares in our moving muscles, triggered by a movement we are doing, it recalls other times of movement. The memory is caught in the preconscious, in the sensing organs, and in the muscles. This

phenomenon, known as muscle memory, allows memory, images, and meaning to be encoded in our muscles (Blom & Chaplin, 1988).

The haptic perception could be explained as something that is possible to be noticed through the sense of touch. This perception can be separated into two sensations: 1) a tactile sense and 2) a kinaesthetic sense. The tactile sense is what a person could feel on his/her skin through nerve cells, while the kinaesthetic sense refers to the ability to sense the space with the body position and the surrounding objects. In other words, the kinaesthetic sense is grounded on information

14 from muscle, joints, tendons, and the vestibular apparatus and, therefore, reflects physical

movements (Hunter, 1954).

The existence of a kinaesthetic is also grabbing attention in academic’s area especially within pedagogy or the areas that want to achieve a holistic viewpoint on dichotomies that separates body and mind from each other (Gardner, 2000; Hannaford, 1995; Damasio, 1994).

In most movement-based activities such as dancing and acting, people often talk about ‘bodily memories’. Bodily memory can be described as learning by practicing the same exercises over and over. The kinaesthetic sense is strongly associated and intertwined with other senses of humans. For instance, people who have trained in specific types of movement such as dancers and athletes have the ability to do physical changes in their muscles without seeing the physical movement. This means they are able to make use of their bodily memory and kinaesthetic sense.

The kinaesthetic sense can provide information and feedback about where the body is in relation to itself and to the physical surrounding objects therefore, the capability to control the body movement. This is the strongest and most relevant sense for actors and dancers, as it refers to the body’s capability to perceive weight, balance, muscular, tension, rotation, stretch and, etc. (Blom & Chaplin, 1988).

In the Body Memory, Metaphor and Movement, the German psychiatrist Thomas Fuchs distinguishes body types into six forms: procedural, situational, intercorporeal, incorporative, pain, and traumatic memory (Fuchs, 2012). Procedural memory contains the kinaesthetic and sensorimotor abilities. This memory can be understood as dynamic processes: patterned orders of movement, habits that are well-practiced, pattern-perception familiarity, and skillful handling of

15 tools. Performers in acting classes are often becoming familiar with the learning about body movement, which mandates to forget what they have learned so far and to let it sink into implicit unconscious knowledge. In this way, actors can obtain the skills that make up their personalized way of being-in-the-world (Fuchs, 2012). William James says: “It is a general principle in psychology that consciousness deserts all processes where it can no longer be of use” (James, 1950). And Thomas Fuchs adds,” What we have forgotten has become what we are”

(Fuchs,2012), which is a reason why procedural memory plays a major role in the human body learning skill. The primary case study in this paper relies on actors and their physical

movements, however, because dance techniques are part of any movement classes in acting courses, the notions of dance and dance theories will also be discussed during this study.

In some modern acting schools, students are required to learn some dance techniques because in dance they can find various examples of human movement and methods for

exercising the ability to express aesthetic matters through movement. This study mainly refers to dance methods and theories of Rudolf Laban. Laban’s theories of movement are applicable to all kinds of human movement and can be expanded to all performers who use their full body.

2.1 Laban’s Dance Theory

Rudolf Laban (1879-1958) was a Hungarian choreographer and dance/movement

theoretician. He established the discipline of dance analysis, and he developed a system of dance notation, which is known as Labanotation or Kinetography Laban (Trinitylaban.ac.uk, 2019). His dance and movement theories can be divided into four categories: Laban Movement Analysis (LMA), Space Harmony, Dynamic Qualities of Movement and Dance, and Harmony of Movement (Maletic, 1987). The Laban Movement Analysis is the most appropriate theory for

16 this study to fulfill its aim which is understanding the physical movement challenges for training performers in practice-based learning settings.

There are several ways that movement can be described but from a physical point of view, the movement can be thought of the change of the position of an object within a specific space and time. Therefore, it can say that “time” and “space” are two important elements of the human movement. From a dance theory point of view, the amount of strength that a human exerts for a movement should be considered as the third movement element, which is often called the energy or force element. However, Laban re-named the force notion with “weight”. He also introduced the fourth element as fluency and later called it “flow”.

In the Movement Analysis category, he describes the way a movement could be done with respect to inner intention, which is known as Laban “Eight Efforts” theory. Effort theory is one of the most useful elements for performers, especially actors. The concept of doing

something with respect to inner intention, explains the difference between reaching for a cup of tea and punching someone in anger, in terms of “body-organization”. In both scenarios, the extension of the arm is involved but inner intentions are varied in terms of timing, control of the movement, the strength of the movement, etc. Therefore, the quality of the movement is an important notion for describing how time, space, weight, and flow can be combined. For instance, there is a difference in the quality of the movement if a person reaches for a cup of tea fast and direct, rather than fast and indirect. Laban described four components that, when set in particular ways, make the “Eight Efforts” of human movement. He introduced two elements for each of the four-movement notions. 1- Time (sustained and quick). 2- Space (direct and indirect). 3- Weight (light and heavy). 4- Flow (free and bound).

17 Even though Laban was a choreographer and his theories are based on dance movement, he still defined that his theories were suitable for all kinds of human movement. He then argues that “Whether the purpose of the movement is work or art does not matter for the elements [e.g. time, space, weight, and flow] are invariably the same” (Laban, 1950/1980, p.93).

Laban Movement Analysis is a helpful tool for actors who have difficulties shaping into the character’s movements and move outside their own bodies. According to Laban, human beings have inherent goals for moving. He describes that a person might move to reach/move an object or to satisfy his/her needs. The goal behind a movement might be tangible or intangible and could include different characteristics. For instance, planned actions, unaware tics, physical reflexes, and doing activities that might be fun or pleasurable. Moreover, Laban highlights that movement shows a mindset that is affected by the surroundings of the mover. This means there is a tangled relation between mental and physical motivations for moving. People can

communicate with their bodies in order to represent beliefs with different body actions.

Laban Movement Analysis (LMA) presents a new terminology and taxonomy that helps to deliver a language for detailed step by step movement scenarios. LMA is also the primary theoretical root for Labanotation and used in different activities such as theatre, anthropology, psychotherapy, sports, psychology, movement education, etc. In doing” Labananalysis” the human observer explains the movement in four sections 1- what human efforts are involved, 2- what kind of body shapes are created, and what are the processes of change from one shape into another, 3- what body parts are stationary. 4- how is space involved in locomotor and stationery movement.

The applicability of Labanotation for modeling the motor skill when practicing a new acting technique can be analyzed using the Laban Movement Analysis method. There are

18 different ways that motor skill learning can be defined, however, motor skill in this paper refers to the process of growing the ability to perform a function that needs the whole body or a limb movement to achieve the goal (Santos, 2017). Providing personalized learning support at the appropriate level for an individual learner is something that had less attention in pedagogical approaches in the acting industry. Although the human effort in learning physical movements concludes a huge part of the learning process, teacher’s roles, and their pedagogical approaches are also something that should be considered. According to Prior’s (2004) finding, despite many books, articles, and practical approaches to acting techniques and methods, astonishingly, there is very little attention to actors training pedagogy. Prior argued that actor student oftentimes

remains:

“a mysterious facet of the theatre industry due largely to the unarticulated understandings of pedagogical practices of acting tutors” (p. i).

Prior also includes; the evidence indicates that literature focuses mostly on the methodology part rather than the teaching of actors and pedagogical approaches. He also mentioned that a lot of research tends to write about acting techniques and not on the efficiency of delivering learning:

“to date, the pedagogical murky waters of actor training remain relatively uncharted” (p. 8).

In recent years, several studies conducted in the educational industry towards providing personalized support in “affective” and “cognitive” which are classified as the two learning domains. However, there has been less attention providing personalized support for motor skills as the third learning domain (Santos 2016). In fact, there are several challenges that occur in delivering appropriate motor skill support. For instance, an existing challenge in this scenario could be designing proper movement modeling that diagnoses different errors, as well as the use of an appropriate sensorial channel that can process the recognized diagnosis.

19

2.2 Human-computer interaction

Human-computer interaction (HCI) began in the 1980s in the root of cognitive science and computer science, but it still does not directly belong to the particular theoretical background. In the 1990s, HIC was expanded into social science and recently into the wider viewpoints of the interaction between people. In computer human interaction the approach taken when talking about the relation between technology and users, is usually from a cognitive standpoint.

However, because this viewpoint does not take into account the cultural, and emotional aspects of human interaction, it has been criticized. In the area of human computer interaction, the embodiment notion has been used as a picture of people in a social ’virtual setting’.

Paul Dourish (2001) In his book where the action is: The Foundations of Embodied Interaction presented the embodiment notion to a larger arena within human computer

interaction and. Dourish presented a new way of experiencing computer systems that for instance touch upon the area of social computing and tangible computing. He describes the term

embodiment as ”the creation, manipulation, and sharing of meaning through engaged interaction with artefacts.” He also depicts the ’embodied phenomena’” those that by their very nature occur in real-time and real space” (Dourish, 2001, p.126). According to Dourish, not only touchable objects could be embodied, but also things like human actions and their conversation could also be embodied. This means that to be embodiment is more than physical and visual appearance. It implies to contribute to real space and real-time. Therefore, embodied interaction is

demonstrating the importance of the user's body interactions with the physical world.

Embodiment and HCI are practically in close relation, as it made one aware of users as well as users from the surrounding setting. In fact, human actions are a result of something our

20 environments as well as surrounding settings influence humans with and vice-versa (Dourish, 2001).

2.3 Multimodal Learning Analytics

For the past few years, scholars have been showing interest in the area of Multimodal Learning Analytics (MMLA). Worsley and Blikstein (2011) defined this learning method as “a set of multi-modal sensory inputs, that can be used to predict, understand, and quantify student

learning.” The term Multimodal Learning Analytics was first discussed in 2012 at the conference on Multimodal Interaction (ICMI) (Scherer, Worsley, & Morency, 2012; Worsley, 2012). Later in 2016, scholars such as Worsley, Abrahamson, Blikstein, Schneider, and Tissenbaum (2016), presented Multimodal Learning Analytics as a term that connects three ideas namely: multimodal data, multimodal learning, and Computer-supported collaborative learning. At its nature, MMLA uses the information in order to model and describe the human learning process in complex learning settings.

There have been several studies that focused to understand the challenges that performers encounter when practicing a new motor skill with the special focus of giving personalized

feedback. For example, Santos and Eddy (2017) research on designing a system that follows the LMA for movement modeling in martial arts, Aikido. Learning Aikido requires training for both mind and body movement. As Santos and Eddy indicated, no motor skill learning system has directly designed for recognizing the movement errors when practicing physical movement with an opponent and delivering suitable personalized feedback when needed. They explained how to use LMA to analyze the joint performance in Aikido by addressing the defensive movement of

21 the Ikkyo (one of the principles of Aikido) against other attacks. LMA is used to educate the correct arm gesture (Santos and Eddy, 2017).

In the same concept, Ochoa and colleagues (2018) have presented an approach for supporting students with presentation skills using a low-cost sensor named “RAP system

recording environment” (Ochoa. et al., 2018). They aimed to help entry-level students in order to enhance their basic presentation skills using MMLA systems that deliver feedback as bad or good presentations. This study wants to explore the idea of supporting training actors when practicing for physical movement with LMA modeling as to some extent close to the work from Santos and Eddy in the case of martial arts Aikido.

At the same time to explore the idea of “RAP system” in the concept of Multi-Modal Learning Analysis in order to capture performer’s body movements and understands how to support the physical movement learnings from an MMLA perspective in the modeling of the actor’s communication with the technology but more than just a “bad” or “good” feedback. The aim is to be able to provide appropriate personalized feedback for each individual and explore if there is any potential to implement and combine these two ideas together in the acting industry. The above-explained background theories create a framework to answer the research questions employed in this study. However, as providing support for motor skills learning is still a new approach this question might still remain as to what extent MMLA can support the actors' physical movement learning process.

22

Chapter 3 - Methodology:

Because the intention of this work was based on learning from experience and looking at patterns and themes, the inductive approach was chosen as the main research method. Inductive

reasoning allows the researcher to observe and use participants’ views to develop a more comprehensive theory (Trochim, 2007). One reason that the inductive approach chose was to help the author discover general features that could affect an actor’s behavior (in terms of physical movement). Also, the author's intention was to understand the phenomenon behind the physical movement learning process for actors when learning a new motor skill. As Bernard explains in Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches the inductive approach “involves the search for pattern from observation and the development of explanations for those patterns through series of hypotheses” (p. 7). The methods used in this study are namely participant observation, direct observation, Semi-structured interview, and Survey which will be described in more detail later in this chapter (see section 3.2).

The qualitative methods were chosen as data collection techniques because they capture the depth and difficulty of the topic and are good enough to capture unanticipated information which might further contribute to the understanding of how practicing or learning physical movement works.As the intention of the author was looking at the interaction between technological devices and performers’ physical embodied level and also to understand and design needs for training actors and coaches/directors, the human-centered design (HCD) has been chosen as a design approach along the way in this study. HCD can provide help to connect better with people, increase seeing new opportunities, and create different solutions.

23

3.1 Research Design:

The choice of research design and data collection requires significant attention to the outcome of this study. Therefore, it is essential to assess the reason for the chosen methods. Given that this research explores the challenges that training actors encounter when learning the new physical activity, it seems very relevant to understand the community of thought amongst training actors and acting coaches. The grounded theory begins with digging into a research situation and letting the researcher understand what is occurring through conversation, interviews, and observations (Glaser, 1992). With, if this study lets the author genuinely listen to the training actors and acting coaches, then the methodology used in this study seems to meet these requirements.

3.1.1 Human-centered design

The Human-centered design (HDC) emphasis is on designing software that can be compatible with the characteristics of humans which means the designed technology should not expect users to adapt to certain software (Norman and Draper, 1986). In this study, HCD is defined as

software designed to exploit the peoples’ existing or acquired abilities and limitations in a higher priority, compared with other aims during the design process. According to Hoffman and

Colleagues (2002), the HCD approach is also referred to as ‘user-centered design’, which concentrates on characteristics of people as well as specific features of target users to make the designed system sophisticated enough for the needs of the users. (Hoffman et al., 2002). The designers at IDEO (2015) believe that the people who experience difficulties in everyday life are those who also hold the answers for designers and developers. Brown Tim (2009) states, if a human-centered designer believes in things that have been learned from people, the entire team can find better solutions for the world's needs. The HCD process starts with a general or

24 specific design challenge which includes three phases: 1) Inspiration phase that helps the

designer hear the needs of people in new ways. 2) Ideation phase that aims to create solutions to meet the needs from phase one. 3) Implementation phase that delivers solutions with a financial aim (Brown, 2009).

In line with centering users when designing new technology, Santos and Boticario (2011), introduced “TORMES Methodology to Elicit Educational Oriented Recommendation”. According to recommender systems in education (2010), current methods emphasize on

recommending learning objects that have been offered to complement the course, however, they did not consider the individuality of the educational field when designing the recommendation. (Santos and Boticario, 2011). To manage this gap, the Tutor-Oriented Recommendations Modelling for Educational Systems (TORMES methodology) was introduced. TORMES methodology provides support for the educational system by involving the teachers/ instructors within the data analysis and HCD approaches. The TORMES methodology uses several

iterations cycles based on computer interactive systems.

At the same time, the Design Council group introduced a framework, the “Double Diamond”, as a design thinking process within the human-centered approach. The Double Diamond is a model that contains four phases namely discover, define, develop, and deliver. The first phase of this model begins with discovery because the Design Council core emphasis is on ‘user research’ and therefore, understanding users’ wants and needs (Design Council, 2012). This study uses the combination of the “Human-centered design approach” and the “Double Diamond model” which is shown in Figure 1.

25 Figure 1 represents the re-defined double diamond introduced by Dan Nessler on May 19, 2016

This re-defined figure aims to provide guidance to tackle design challenges and combines the four phases of Double Diamond (discover, define, develop, and deliver) with the three phases of Human-Centered design (inspiration, ideation, and implementation). The re-defined double diamond describes the first diamond as “designing the right things” and the second diamond as “designing things right” (Buxton, 2007).

26 As the aim of this study was towards understanding the challenges to support performers with their motor skills, the research done during the design process falls into the first diamond which is the combination of "discover/research" with "define/synthesis" phases. The process of getting into the second diamond is considered future steps for this study. In order to answer the research questions, it was important that the methodological approaches used in the study allowed the interaction between stakeholders. This was a key element to draw any conclusion for this research. The data collection methods used in this research are participant observation, semi-structured interviews and survey. Further, this chapter describes the most important ethical considerations in the research. Figure 2 inspired by TORMES Methodology which illustrates a journey of how each method was used and evaluated in the different phases of the study.

27 Figure 2 illustrates, represents the design process within the first diamond of the double diamond model. The process contains five phases which will be discussed in chapter 4 in sufficient detail. Phase I and phase II start with primary research which follows the “people-centered framework”. The concept of the people-centered framework was introduced in Convivial Toolbox, by

Sanders and Stappers (2012). This framework divides people into the three categories: what people say, what people do, and what people make. All three types of research design tools can be used in different parts of the design process. However, what people “say” and “do” are the most relevant areas to fulfill the aims of this study.

3.2 Data collection:

In this section, the applied methods and the motivations why they have been chosen for this study are defined.

3.2.1 Participant Observation

Participant observation was used as a tool to understand what people “do” in phase I. The data in this phase was gathered from the two rehearsals at Malmö AmatörteaterForum (MAF) with “On Stage Skåne” production and “Orizon.Art”. At the time of writing this paper, the author was a member of the On Stage Skåne production and after she explained the research idea to the managers of On Stage Skåne, they have agreed to be part of this study. During the brainstorming session that the author had with a member of On Stage Skåne, it brought up into the author’s attention that there is an acting workshop running in Malmö with two professional directors called Orizon.Art. The author has contacted the Orizon. Art production and they have also accepted to be part of this study. More detail about the two theatre groups is discussed in chapter 4. One of the roles of the author in this part was to be the subjective participant and use the information obtained through personal engagement with the research topic to communicate

28 better and get further to know the On Stage Skåne and Orizon.Art productions. At the same time, the author plays the objective role and used the visual research method of video recording with sound and photographs of each and every rehearsal and not allowing the emotion impact on the findings from the observation. It is important to mention that the recordings have only done with On Stage Skåne production and the author had only taken notes during the observation with Orizon.Art (see chapter 4).

All the participants of On Stage Skåne were the cast members that working on the upcoming show “Marian or the Real Tale of Robin Hood”. As it has been mentioned, the author at the time of writing this paper was part of the On Stage Skåne production and all the cast members were aware that the author uses their rehearsal as part of her research project. In the case of Orizon.Art, the director has introduced the author to the cast members and the author has explained her role as a researcher and her research topic.

29

3.2.2 Semi-Structured Interviews

As the author’s intention was towards using the human-centered design approach, it was important to listen to the people and hear their needs in their own words. According to Grey 2014, the interviews are a qualitative method of data collection and are viewed as a valid method of analyzing data (Grey, 2014). Interviews with participants can provide narratives describing how performers experience and react to physical learning and what the most common difficulties performers encounter are, both when learning and practicing new techniques while performing at the workshops or at home.

Semi-structured one-on-one interview conducted with both theatre groups which provided a great opportunity for the author to gather data and understand the actor’s behavior, the physical learning process, physical abilities, and the challenging key elements for each student. Three different interviews have been conducted with beginner actors, professional actors, and directors, acting, and dance coaches.

3.2.3 Survey

Using a survey to collect information is a flexible and organized way to gather numerous

answers. This method helps the researcher to save the time upon gathering data without having to spend time talking to each participant (Gray, 2004). The Walliman 2017mentioned survey helps people to answer anonymously the questions and often without feeling for example,

30

3.3 Prototype:

As the aim of this study is to understand what are the design requirements for a future system to support performers with their motor skills, the methodology used in this section generates a clear idea for design requirements that eventually are needed for any future technology. After findings from phase I and II and III, several sketches and storyboards were drawn. The final solution had been developed as an app that contains some of the design requirements introduced in chapter 5. The app provides a simple modeling movement in which the user must imitate the movement while saying the desired monologue. The user will receive personalized feedback based on the acting exercises they have done. (see chapter 6.2).

3.4 Analysis

The assessment and analysis of gathered information were conceded at the end of each design phase. Every gathered data was broken down and examined at the end of each phase. All the information from observation and interviews were carefully reviewed and compared with each other. Findings from observation and interviews are considered as unstructured research findings. In phase III, the list of findings from Phase I (observation) and II (interviews) was discussed with several acting coaches. The approval on the list of findings from coaches drove the research process into phase IV where the target group defined and sketched, and storyboards were also conducted. In this phase, the first draft of the design idea was discussed with amateur actors, coaches, and directors and according to the feedback received from the target tested, the design requirements were introduced. In phase V, the design solution was tested with the target group with help from the MMLA system and the survey.

31

3.5 Ethical Considerations

Allen (1996) examined that consent should be a continuous discussion throughout the entire research process and not just some sort of an agreement at the beginning of the research. Since this research followed the visual research method during the data collection (video recording with sound and photographs), the ethical concept was a topic that needed to be controlled with sensitivity, during the research process. Sarah Pink (2017) in Doing visual ethnography stresses that publication of the collected data might increase extra issues for the researcher, and therefore, the distinct difference between the researcher's goal and his/her intentions must be clear from the beginning to the participants of the research. “The publication of certain photographic and video images may damage individuals’ reputations; they may not want certain aspects of their identities revealed or their personal opinions to be made public” (p.17). In accordance with Pink’s statement, before the research begins, all participants were informed on the purpose and the intentions of this study. As most participants of this study were actors and emotions were involved in their performances, it was very important that all participants felt comfortable with the situation of having their feelings sensed. The participants were given a consent form, where indicated information about their rights (voluntary participation and withdrawal etc.) and the

confidentiality of all results. The participants were fully informed about the process of video and the audio recording as well as photographs (both verbally and in writing). Four of the

participants did not desire to be video recorded nor photographed, but after getting to know the researcher, they voluntarily asked to be part of the video recordings and/or photographs. Finally, all volunteers did receive a signed copy of the consent form.

32

Chapter 4 - Context of use

This chapter describes the pre-study methods based on the research questions and the theoretical background. The main intention of the design phase was to develop a series of iterations to create a prototype concept. These iterations provide a framework to understand the design requirements for supporting performers. The relation of each phase, procedure, and findings from each method is also explained.

Phase I and phase II of the research design start with primary research which follows the “people-centered framework”. The concept of the people-centered framework was introduced in Convivial Toolbox, by Sanders and Stappers (2012). This framework divides people into three categories: (1) what people say, (2) what people do, and (3) what people make. All three types of research design tools can be used in different parts of the design process. However, what people “say” and “do” are the most relevant areas to fulfill the aims of this study.

4.1 Phase I- Context of use (Observation)

The "what people do" technique was used in order to understand how the human body works. According to Sanders and Stappers (2012), the most effective “do” technique is

observation. Gossling (2005) explain that looking at someone’s room for fifteen minutes can deliver more reliable information about one person than spending a whole day with that person (Gossling, 2005). The section below describes the different types of observation techniques that lead the author towards answering the research question of what the requirements are for

33

Participant observation

There are two main types of observation. Firstly, “direct observation,” in which the researcher only observes without interacting with the objects or people. Secondly, “participant observation,” in which the researcher acts as both observer and participant in the situation under study

(DeWALT and DeWALT, 2002). The participant observation method was chosen as the main technique for data collection at “On Stage Skåne” rehearsals, and the mix of participant

observation and the direct observation at “Orizon.Art”. The observation method has helped the researcher to sense and experience the challenges that performers encounter when learning a new physical movement. This method facilitated the development of researcher relationships with the participants and also to increase the quality of the other design methods used in this research, such as interview and focus groups. Two observations of workshop/rehearsal were conducted during this research. The first observation was conducted with “On Stage Skåne” and the second observation with “Orizon.Art”.

The section below describes the most important techniques used in each rehearsal. It also provides information about the researcher’s participant experience in the field. Finally, discusses the most relevant finding from the observation sessions.

On Stage Skåne

“On Stage Skåne” is an English-speaking community theatre group based in Malmö. The group was formed in January 2016 by two friends, Richard McTiernan, and Anne Alcott to help integrate English people into Swedish society. Around 8 members performed the first show in September 2016 and since then the group has done four performances and today they have 24

34 members. Throughout time, the ethos of the group was that theatre should be fun and available to all. At the time this study was conducted, the cast and crew of “On Stage Skåne” were working on the upcoming production “Marian or the Real Tale of Robin Hood”. It might be interesting to mention that the author of this paper had a role (a guard named Locus) in the production of Marian.

The rehearsals for “Marian or the Real Tale of Robin Hood” consisted of twenty evening classes once a week from January to May 2019 at Malmö AmatörteaterForum (MAF). Each rehearsal lasted three hours, where the first one and a half hours were worked on warm-ups and different acting techniques. The members of “On Stage Skåne” did not require to have any academic acting knowledge and their cast was a mix of professional and amateur actors. The participants were informed that their rehearsals are going to be used as part of a research project, and they accepted to be interviewed one or two times, as well as being recorded with video and photographs.

The pedagogy used for the rehearsals was based on the tradition of the modern acting and dance techniques, which had a focus on individual movement and personalized expression. As the cast of “On Stage Skåne” contained people with and without dance experience, the director (who was a choreographer and an acting teacher) and her pedagogical method played a major role in the participants’ expertise during the rehearsals, thus their understanding of the human movement.

During the first one and a half hours of each rehearsal, the participants practiced different kinds of movements that were intended at exploring the concept of basic movement patterns and

35 emotions. The important part of each rehearsal was to practice, learn, understand the

personalized motor skills and physical abilities, and to develop an awareness of their bodies. Simply, all the emphasis during practice was on understanding how an individual moves and how one does not move. The notes were written both during and after each observation session.

Orizon.Art

In order to gain a better understanding of actors’ physical learning process, a second "participant observation" was conducted with an English acting workshop called Orizon.Art. The workshop was run by the owners of Oriundus Art and Zorra Art productions. The Orizon.Art targets both children and adults who have a passion for becoming actors/actresses.

The experience of participating in this workshop was quite different compared with the experience with “On Stage Skåne”. The Orizon.Art production owners did not accept taking any photographs, videos, or audio recordings. The workshop consisted of seventeen evening classes once a week during the winter 2018 and spring 2019, with a total of eight students and two teachers at Carbs Studio in Malmö (The author only participates in one workshop session). An introduction meeting was carried out with the teachers of Orizon.Art, before the workshop, got started. The purpose of the meeting was to clarify the intentions of author observation and her research aims. During the meeting one of the teachers asked if a back-up idea was planned, as she strongly believed that technology, in general, would cause harm to the actors’ creativity:

I do not think that technology can be part of the actor’s life. I mean if the technology was able to help actors with their movement challenges, we would have had some kind of a device today. I apologize but, I cannot see any future or any need for such a thing in this market. I believe that technology and especially what you are talking about is going to stop people's creativity and their unique personality (Orizon.Art, personal interview, 2019).

The meeting continued further by joining new participants (two students) in the meeting and talking about the time that an actor needs to learn a new movement. After all the students showed

36 up, the actual workshop started. The workshop lasted three hours, wherein the first half an hour, the students worked on the warm-ups and different acting techniques. The other two and a half hours was based on character building techniques. As video recording and photography was not allowed during this workshop, the observation session was divided into two parts. Part one of the observation used the "participant" method wherein the first hour of the workshop, the

author joined the body warm-ups techniques. The second part of the workshop turns into a "direct observation", where the author only took notes and drew some sketches without interacting with any objects.

Acting techniques used during the workshops:

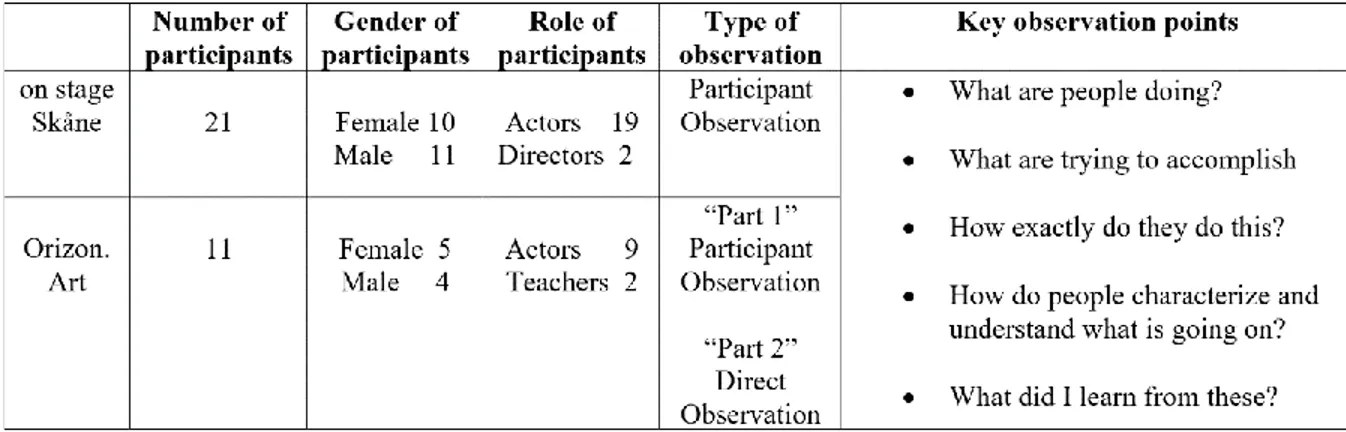

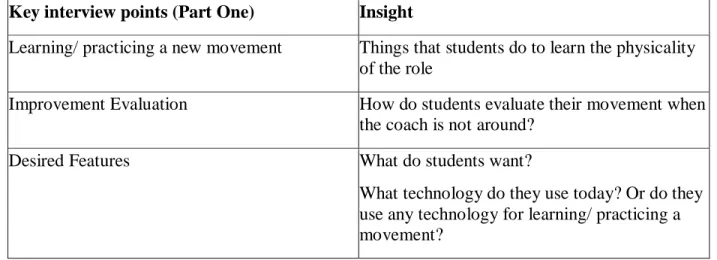

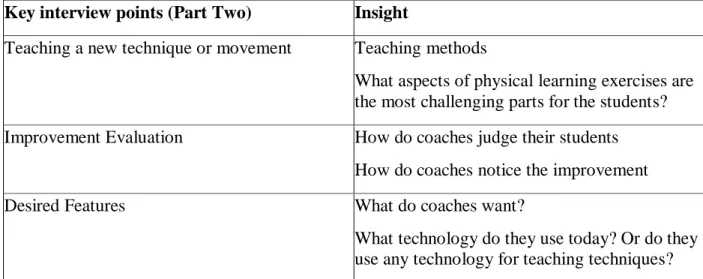

This section discusses the most important techniques used by the acting coaches and directors to develop the students’ acting skills. Further, it describes the purpose of the workshops and the role of coaches and students. Finally, discussing the relevant findings from the observation sessions with “On Stage Skåne” and “Orizon.Art”. Table 2 indicates the number, gender, and role of participants as well as things that were considered during the observation.

37

Type of techniques used by coaches/directors to develop students’ acting skills:

On the basis of photography, video recording, and note writing evidence, it appears that there were several tactics used by the acting coaches in the workshops to facilitate learning the process and understanding the material of the students. The tactics described in this part are related to rehearsal activities. According to the evidence available from the observation notes, the techniques used to develop students’method acting include relaxation exercise, foundation exercise, advanced sense-memory exercise, character development, need exercise, and animal exercise. The explanation of some techniques are discussed as follows:

A. Relaxation exercise:

Relaxation exercise is one of the techniques to engage the student's whole body with the space and objects around them. The Orizon.Art teacher started the class by a quote from Lee Strasberg (1901-1982) which emphasizes the importance of a relaxed body.

You all need to remember that actors need a warm heart and a cool head. You need these two elements to be able to gain control over your body and mind. You need to free up your body from the pervasive problems of tension and habits (Orizon.Art, Observation notes, 2019).

The teacher continues further by asking some questions to both attract and engage students to do the exercises. For example, she asked if the students heard about the Stanislavski “creative mood”. The teacher continues by describing the "creative mood" as a way in which an actor can be aware and notice where and how his/her emotions and senses can function expressively. The teacher adds that one way to achieve a creative mood is by doing a relaxation exercise. An essential exercise that actors must do to take control of their physical activities as well as their emotions. The meditation was used together with the relaxation exercise to help actors become more aware of their bodies. The teacher reminds students to return back to this exercise when

38 there is a loss of control or distraction during the rehearsals and pre-performance. The relaxation exercise was also used during the “On Stage Skåne” rehearsals.

Figure 3 shows students during the relaxation exercise

The exercise started with students sitting on a chair. The students are required to ask themselves a question of how they feel at that moment both emotionally and physically on a scale of one to ten. The exercise lasted for fifteen to twenty minutes, during which they moved all the different parts of their body one by one. The movement started from the toe to head and sometimes they made specific noises. After finishing moving each part of the body, the teacher taught students how to distinguish the areas of their bodies that hold mental tension. According to Lee Strasberg, there are several areas around the head part of the body that gather the tensions. For example, Strasberg referred to the “blue nerves”, which is the area around the eyes, the “thick muscles”

39 that are the muscles around the nose, the muscles around the jaw, mouth and the tongue, as well as the nerves contained in the back (Cohen, 2010). The nerves and muscles in the back usually keep the traumatic experiences from childhood that might be tight and very hard to make contact with.

The teacher also used different meditation techniques in order to create deeper body awareness. This awareness was included in physical sensations like cramps, burning, tingling, etc. The exercise continued with the exploration of the parts of the body that the actors usually do not make contact with. These parts include ears, knees, back, etc. The students are required to make a sound “HA” when there is tension in their bodies. The sound should have been loud enough and elongated for ten seconds. The evidence indicates that both movements and sounds support actors with letting go of blockages and difficulties. Finally, the teacher checked the relaxation point on each student. The teacher lifted the arms, or legs in order to sense student’s tensions and determine whether students are relaxed or not.

Author experience as a participant in the relaxation exercise:

During the relaxation exercise, the teacher told the author to not touch her eyes and stop biting her lip. she realized that continually touching her eyes like she was checking if her eyes are still on her face. The author also realized that she was biting her lip several times, which she stopped and tried to relax her arms and hands. After 5 minutes, the teacher told her again to not touch her eyes and she had no idea why she was touching them again and was not even aware of that. The author tried to relax her body one more time and felt tingling in her hands. Some minutes later, she felt that her fingers were heading up to her eyes again, and this time she tried to not touch her eyes and kept the arms open and relaxed by her side. It was quite a shocking experience for the

40 author to notice that she has a habit of touching the eyes continuously and noticing that she was able to control it was liberating.

B. Foundation exercise

The second technique used by “On stage” Skåne was a foundation exercise. This exercise emphasizes the role of human senses. This technique merges the actor's own present moments with character present moment and is only doable by activating the five human senses. The director of “Marian or the Real Tale of Robin Hood” wanted the actors to be fully present in “the now situation”. The director describes the sense building as the important ability to have the audience believe in things an actor is doing. The sense building is a journey of imaginary places, people, activities, objects, etc.

I want you all to know that we are not doing the foundation sense exercises to provoke emotional responses. You are supposed to make a physical and mental discipline with each of the foundation sense exercises. I want your senses to be engaged at all times (“On Stage Skåne”, Observation notes, 2019).

The director was reminding the actors that for an emotional response they do need to have other exercises like advanced sense memory exercise. The evidence from video recording indicates that there were several times that students especially those with little experience lost focus and got blocked. The director gave those students the “Abstract and Speaking Out” exercises. This exercise is one of the techniques introduced by Strasberg that the actors can use when their disorienting habits take hold. They can use "abstract and speaking out" exercise to find a clear expression, and to deal with their physical movement challenges. Every session of “On Stage Skåne” rehearsals began with one or two foundation sense exercises. These exercises included:

41 Breakfast drink exercise, taking off and putting on underclothes, mirror make-up/Shaving

exercise, overall sensation exercises that contained shower and bath, drunk and strong wind exercises, need exercise, etc. Figures 4 and 5 represent some of these exercises.

Figure 4 illustrating the abstract exercise

42

Author experience of being a researcher and an observer:

As it has been discussed in chapter 3, the author had the role of the subjective participant by observing what each individual does in the workshops/rehearsals. On one hand, the evidence of writing notes during some of the rehearsals with On Stage Skåne indicates that some actors felt unsure of their movement. This happened when one of the cast members asked the author how her body posture looked like from the back (the cast member was a woman who should shift her body posture and gesture to act like an old man). On the other hand, the author plays an objective role as a researcher by recording every rehearsal. Analyzing some of the videos, indicate that because of a big number of the cast (19 actors), the director was not able to capture each individual movement mistakes, could not continue the equal level of concentration for a long time, and not be able to give collective feedback which also means not able to provide personalized feedback for each actor. At this point, one of the author’s assumptions was that there is a need for a kind of tool to help the coaches capture students' movements and provide the appropriate feedback. This statement was supported by some of the conversations that the cast member of On Stage Skåne had with others about their need for extra eyes to follow their movement.

“I wish to have a personal assistant to teach me even simple exercises. I am not even sure if I do the abstract exercise correctly” (”On Stage Skåne”, Observation notes, 2019). The author's experience at this stage indicates that technology might be able to support students and educate a simple movement while providing personalized feedback. However, to get the validity of this statement she conducted several interviews with both On Stage Skåne and Orizon.Art production.

43

4.2 Phase II- Context of use (Interviews)

According to the “people-centered framework”, the interview is part of the “say” technique that allows the researcher to learn more about the people under the study. Sanders (2012) describes that the “say” technique is going beyond the superficial layer of human behavior. The features of the method do not only act as user behavior on his/her own, but it also acts as a way of

communication of a human toward another. (Sanders and Stappers, 2012). However, what people “do” is not the same as what people, “say”. This means people might sometimes make

themselves look better than what they are or might not do what they say. What we think we are doing is often not what we are doing.

As the author’s intention was towards using the people human-centered design approach, it was important to listen to the people and hear their needs in their own words. Based on the findings from phase I, the observation analysis indicates that there are several differences between the needs of beginner and expert learners which are discussed in Phase III. In fact, the “say” technique was conducted at this phase of the research to understand the focus group. The author’s intention was to understand the independent thoughts of performers who have

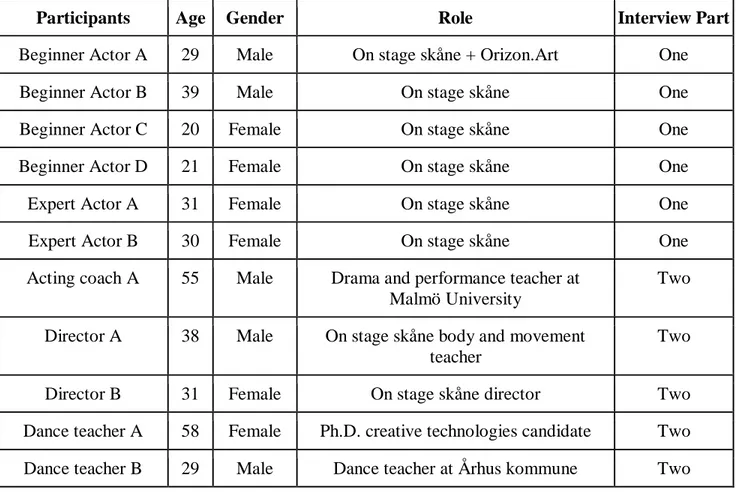

participated in either On Stage Skåne or Orizon. Art rehearsals/workshops and ask each person the open-ended questions. In total eleven people accepted to be interviewed, This included four amateur and two experts actors, three acting coaches/ director, and two dance teachers. The interview sessions were divided into two parts.

Part One: To hear the needs of students which included both beginner and professional actors.

Part Two: To hear the opinion of the coaches and understand their expectations of each

44 Listening to the stories and experiences of teachers has helped the author to identify the focus group in a reliable manner. Part two of the interview included professional directors, acting teachers, and two professional dance teachers.

In fact, in order to understand the requirements to support actors with their physical learning process, the concerns from both parties (students and coaches) were important for this study. At the same time, understanding the techniques used in the dance classes was also an important factor because acting students and coaches are using dance techniques as part of their methods in physical learning.

The semi-structured interview was conducted individually at the rehearsal environment with directors, teachers, expert actors, and amateur actors after rehearsing sessions. One interview with the professional dance teacher was conducted at Malmö University and one interview over Skype. The interviews took approximately 30 to 45 minutes, all interviews were recorded and transcribed. However, the breathing, laughs, humming, pauses were not part of the researcher's notes writing. In addition, there was no confirmation on any comments such as: yes, that’s correct, alright, right, exactly, etc. The aim of these interviews was to collect the verbal data on how the participants experienced the acting rehearsals/workshops and to understand their needs. All conversations were held in English. Appendix 1 contains a more complete list of the interview questions. Table 2 indicates information about the participants.

45

Participants Age Gender Role Interview Part

Beginner Actor A 29 Male On stage skåne + Orizon.Art One

Beginner Actor B 39 Male On stage skåne One

Beginner Actor C 20 Female On stage skåne One

Beginner Actor D 21 Female On stage skåne One

Expert Actor A 31 Female On stage skåne One

Expert Actor B 30 Female On stage skåne One

Acting coach A 55 Male Drama and performance teacher at Malmö University

Two

Director A 38 Male On stage skåne body and movement teacher

Two

Director B 31 Female On stage skåne director Two

Dance teacher A 58 Female Ph.D. creative technologies candidate Two Dance teacher B 29 Male Dance teacher at Århus kommune Two

Table 2 representing information about the participants

The next chapter (5) discusses the most important findings from observation and interview sessions. These findings then help the author to identify the target group.