STARTED FROM THE INTERNET, NOW WE’RE

QUEER

THE USAGE OF SNS TO EXPLORE, BUILD AND

COMMUNICATE QUEER IDENTITIES

MADONNA PAULINA NORDLING

Media and Communication Studies: Media activism, strategy & entrepreneurship Bachelor Thesis

Malmö University

Faculty of Culture and Society Spring Term of 2019

coming out. The aim of the study has been to broaden the field with and obtain a deeper understanding of how a marginalized group in society can use social media as a part in exploring and building an identity. The study was conducted with a method of semi-structured personal in-depth interviews with a sample of five Swedish queer people in the age span of 23-27. The result was analyzed along previous research within the field and with a theoretical perspective of culture, representation, performative acting and self-presentation. The result showed that young queer people are exploring, building and communicating their identities in different ways that varies depending on where in the process of coming out they are. The result showed that it was common for the queer people in this study to use SNS while exploring and building their queer identities, but not as common when communicating it. There were both similarities and differences in these findings compared to previous research.

Heading: Started From the Internet, Now We’re Queer – The usage of SNS to explore, build and communicate queer identities.

Author: Madonna Paulina Nordling

Level: Final Exam Project in Media and Communication Studies, 15 hp Institution: School of Arts and Communication (K3)

Faculty: Faculty of Culture and Society University: Malmö University

Supervisor: Matts Skagshöj Examiner: Margareta Melin Term: Spring of 2019

Keywords: Queer, Identity, Youth, Sweden, Culture, Representation, Performative Acting, Self-Presentation, Heteronormativity.

definitions are based on the definition from RFSU (2015) and RSFU (2017), the Swedish Association for Sexuality Education. As an addition to this, the definition of SNS also needs to be further explained, here based on Wikipedia (2019). The words are following:

• Bisexual: A person who is emotionally and/or sexually attracted by persons regardless of their sex.

• Cis-person: A person whose sex and/or gender identity corresponds with the norms of the sex/gender that was registered at birth.

• Homosexual: A person who is emotionally and/or sexually attracted by persons oh the same sex/gender.

• Non-binary: A person whose sex- and/or gender identity is between or beyond the traditional division of sexes and genders (man/woman, male/female), or who does not want to define their gender identity at all. Could also be seen as genderfluid, whereas ones gender identity can vary over time or be a mix of different genders in different times in ones life.

• Pansexual: A person who is emotionally and/or sexually attracted by persons regardless of their gender and at the same time question a binary gender division. Some sees pansexuality as a sexual preference, others sees it as bisexuality with a broader definition.

• Queer: An approach that criticizes norms regarding sex, gender and sexuality. Queer could also be an identity, “to be queer”, and often refers to an opposition to categories such as woman, man, bi- hetero- or homosexual. It also refers to the opposition regarding what is seen as normal and abnormal, often regarding sexuality and gender.

• SNS: A short for Social Networking Sites (Could also be used as short for Social Networking Services or Social Media) that refers to online platforms which people use to build social networks or social relations, often with other people who share similar interests, activities, backgrounds or real-life connections.

Aim and Research Questions ... 2 Aim ... 2 Research Questions ... 2 Limitations ... 2 Disposition ... 3 Queerness and Social Media in a Context ... 4 Queer in a world of compulsory heterosexuality ... 4 Young Swedes and social media ... 5 Previous Research in the Field ... 6 Stages of coming out and SNS usage ... 6 SNS as a resource for information and peer support ... 7 Theoretical Framework ... 9 Representation within different cultures ... 9 Gender construction and performative acting ... 10 Presenting and expressing the personal façade ... 12 Methodological Design and Execution ... 13 Qualitative interviews ... 13 Sample of respondents ... 14 Conducting the interviews ... 15 Validity, reliability and generalization. ... 16 Ethical considerations ... 17 Analyzing the Results ... 18 Stage one, accepting and developing a queer identity, online and offline ... 18 Stage two, the coming out story, not so digital ... 21 Stage three, not being queer enough or being a stereotype ... 23 Stage four, moving away from social media ... 26

Discussion of the findings ... 29 Suggestions for further research ... 31 References ... 32

Introduction

Imagine a world where everyone is assumed to love apples. You on the other side feel like you can’t relate, you are more of a pear-person. But you know that a person who likes pears more than apples is regarded as abnormal in your society. You are young, hearing about how pear-persons are not suitable to get married, just because they like pears. Apple-people are demonstrating against pear-Apple-people, yelling slogans like “Pray the pear away” and “Fear the pear”. Your classmates in school are yelling in the corridors, teasing and saying that others are “fucking pears”. You hide your love for pears, afraid that someone will notice it about you. If people ask, you always tell them that you prefer apples. You feel lonely and afraid. Are you the only pear-person in the world? It certainly feels like it.

Imagine how you one day are casually spending some time online, when you suddenly stumble upon a post on a social networking site about others who likes pears, just like you. You click on the title and get redirected to another site, you can’t believe your eyes, it is fully dedicated to other people who, like you, also love pears. Post after post on the site has content related to how it could feel like to love pears, how you can be fully open in society as a pear-person, and possibilities to get connected to other pear-persons you could talk to privately. You feel like a new world has opened for you.

You might think that this illustration of people who like apples or pears is childish or silly, but the truth might not be so different if you replace pear with queer. The number of people who identify themselves as queer is increasing (Glaad, 2017; Forte, 2018). The last decades have shifted both our societies and media landscapes, where anyone with an Internet connection can produce their own content. This is mentioned as a power shift, marginalized groups in the society can find solidarity and create digital communities online. Despite this change, queer people are still often looked upon as a marginalized group, they have less power than non-queers in a society based on heteronormativity. Young queer people also have an increased risk of both mental and physical illness, based on their increased risks of experiencing discrimination, violence and rejection (Forte, 2018:24-25). However, based on my own experiences, I have found social networking sites to be an important source for information for finding peers and for identity building, not least for queer people. If that is the case, how and why is that?

Aim and Research Questions

In order to understand how social media and SNS (Social networking sites) can be used in multiple ways by different groups in society and affect their lives in various ways, I am going to study how young queer people in Sweden are using social media and SNS in their process of coming out. Since queer people are going through the process of creating and accepting an identity whilst “coming out”, the focus is going to be on how social media is used by them in the process of exploring and building their identities. In order to

understand this, a framework of theories regarding identities, gender and representation are going to be used in relation to the empirical material, which consist of depth interviews with young queer people in Sweden.

Aim

Hence, the aim of this study is to obtain a deeper understanding of how a marginalized group in society can be using social media as a part in exploring, building and

communicating their identities. Many studies have been conducted regarding identity building and gender representation on social media; however, these studies lack

information about young queer people in Sweden and their usage of social media, which makes this an important area to further investigate.

Research Questions

To reach the aim of this study and achieve relevant insights for the analysis, these research questions constitutes the foundation for this study:

• How are young queer people in Sweden using SNS to explore, build and communicate their identities?

• How does this differ in different stages in the process of coming out?

Limitations

In previous conducted similar studies, the age span of respondents has been approximately 18-28 years old. Thus, as a natural connection to previous studies, the age span of

Respondents in this study is going to be 18-28 years old. This is the age where most queer people start their process or are in the process of coming out. Further, this is also within the age span where Swedes are using SNS to the highest extent (Internetstiftelsen, 2018:97). Previously studies have mainly focused on North America, whereas this study will focus on Sweden. These delimitation will put this thesis in the same context age wise but shift the geographically focus to give a broader understanding of the field. The study will examine how queer people in this age span personally describes their usage and effects of social media platforms in the process of exploring and building identities. The study will not delimit to a few social media platforms, but instead touch all platforms mentioned by the respondents.

Disposition

A more detailed presentation of the following sections of the thesis is presented here below, starting from chapter 3.

• Chapter 3, contextualization. In the third chapter, the context of the study will be presented to give a broader overview of the subject and its field.

• Chapter 4, previous research. In the fourth chapter, relevant previous research within the field will be presented in a themed structure. This will help to build the broader understanding first presented in chapter three and put this

conducted study in a more defined context.

• Chapter 5, theory. The fifth chapter will present and describe relevant theories for the study. The theory will, together with the previous research presented in chapter four, act as the framework for the analysis in chapter seven.

• Chapter 6, method and execution. In the sixth chapter, the methodological design and execution will be described and discussed. The sample of

respondent is presented here and the chapter ends with a discussion regarding validity, reliability, generalization and ethical considerations.

• Chapter 7, result and analysis. In chapter seven, the results from the empirical data collection will be presented and analyzed in correlation with the theories presented in chapter five and the previous research presented in chapter four. • Chapter 8, summary and discussion. Chapter eight will critically summarize and

discuss the findings in relation to the aim and research questions. The chapter will end with suggestions for possible further research.

Queerness and Social Media in a Context

This chapter works as a background and broader understanding to the field. The chapter starts with a more detailed introduction to the term queer and the concept of

heteronormativity and ends with a presentation about social media usage in Sweden and social media and identity building.

Queer in a world of compulsory heterosexuality

Throughout this thesis, the term queer is used as an umbrella term that includes all sexualities and/or genders which are beyond either heterosexuality and/or cis-gender. Ambjörnsson (2016:16) explains the term queer as a way of pay attention to multiple different conditions in society that is connected to gender, sexuality, power and norms. Further, she argues that instead of seeing LGBTQ as the opposite to heterosexuality, the term queer makes us look beyond the traditionally divisions between what is seen as normal or not. There has been a shift from using the term “Gay” or “LGBTQ”, and instead use the term “Queer”, which Ambjörnsson (2016:25) describes as a result of a shifting generations.

Throughout the study, the analysis is grounded in society as a heteronormativity. Ambjörnsson (2016:47-48) explains heteronormativity as a form of social organization, which is culturally, socially and historically created, where heterosexuality is taken for granted. Thus, heteronormativity can be explained as the institutions, laws, structures and actions, which maintain heterosexuality as something unitary, natural and universal. In other words, everything that helps maintaining the picture of a heterosexual life as the desirable and natural way of living. The concept of heteronormativity does not desire to criticize heterosexuality, but more so the structures that premier that way of life. The heteronormativity works in ways that Butler (1990:26-31) explains as compulsory

heterosexuality, which refers to the binary restrictions on sex and sexuality with merely

reproductive aims. Both Butler (1990:26-31) and Ambjörnson (2016:53) describe

compulsory heterosexuality as the maintenance of the border between heterosexuality and homosexuality, and the hierarchy between man and woman. A person who is categorized as a woman is expected to desire a man and vice versa. Thus, to know if a person is hetero- or homosexual, one need to have knowledge about this individual’s gender. The

heteronormativity leads to assumptions about one another that might not be true, a person might feel forced to “choose” between only two binaries; man or woman, hetero- or homosexual. People who feel like they don’t belong to either are often seen as strange, incomprehensible or non-trustworthy (Ambjörnson, 2016:53-55).

Even though our society is based on heteronormativity, the younger generation today, in the age group of 18-35 years, is significantly more likely to openly identifying themselves within the queer spectra (Glaad, 2017). The same age group is also much more likely to be allies of the queer community and show support for queer people. However, it is, as Forte (2018:18-19) describes it, hard to know the exact number of people in Sweden that

identifies themselves within the queer spectra. However, studies in Sweden have shown that between 2,4-2,8 percent of the Swedish people identifies as other than heterosexual. The percentage have increased in the younger generation of Swedes in the age span of 18-25 years, where between 8-11,9 percent identifies themselves within the queer spectra. Due to new legislations in Sweden that are relativity non-discriminatory, such as the possibilities for same-sex marriages, Sweden has a rather open climate in society surrounding queer

people. However, queer people have a higher risk of both experiencing physical and mental illness and bullying (a.a.:24-31). Even if queer people have an increased risk of illness and mistreatment, several studies have shown that social networking sites, social media and Internet generally could benefit queer people in their wellbeing (Craig & McInroy, 2014; Fox & Ralston, 2016; Gray, 2009).

Young Swedes and social media

More Swedish citizens than ever are connected to the Internet today (98%) and fewer citizens in Sweden are left in a digital alienation. In Sweden, 83 percent of the Internet users are visiting social networking sites (Internetstiftelsen, 2018:4-5). 75 percent of the Swedes in the age 16-25 years are using Facebook, Instagram or Snapchat on a daily basis. The group in Sweden who is using Internet in different ways the most consists of people born in the 90’s. Further, this group is also the generation in Sweden who the most sees Internet as an important part in the private life (a.a.:97).

The “social” in social media could be interpreted in different ways. It has been associated with a variation of different concepts and explanations. From a various outtake of different approaches towards finding a description of social media, Fuchs (2014:37) summarizes it as a variation of online social activity such as collective action, communities, connecting with others, creative making of user-generated content, co-operation and sharing. Further, Fuchs (2014:37) raises the question about what it means to act in a social way online. This is summarized as the possibility to interact with others, feelings of

togetherness, the enabling of collaborative production of digital knowledge and a system of human cognition, communication and co-operation (a.a.:45).

Previous Research in the Field

The aim of this chapter is to put this study in a broader context by describing and discussing previous studies in the field. The chosen articles treat themes that are relevant for this study and will help achieving a perception about central entries to the field. The themes have been defined based on the main focus in the articles and will help form a clearer picture of what questions that have been studied before.

Stages of coming out and SNS usage

When analyzing the “coming out” as a process, Kus (1985:179) argues that all queer people must deal with a similar or generic process of several stages, but might not complete all stages but instead get frozen in one of them. Despite this, the experiences of the coming out process can be unique to every queer person experiencing it. The process of coming out is a deeply psychological change for the queer person, and those undergoing it might not see it as a series of steps or stages. It is more of a qualitative nature and might be a negative- or positive process.

Kus (1985:178) identifies four stages in the process of coming out as following; (1) Identification, (2) Cognitive changes, (3) Acceptance and (4) Action. Further, more recent research has also focused on different stages of coming out in the combination of SNS. In a study conducted by Fox and Warber (2014), they focused on how queer persons use of SNS differs depending on where in the process of coming out they are. Reading Fox and Warber (2014) alongside Kus (1985), there are similarities in the way the stages of coming out are defined and described. Fox and Warber (2014) describes the four stages of coming out as following: (1) Mostly in the closet, (2) Peeking out, (3) Partially out and (4) Out. Similar stages have also been identified and studied by Owens (2017).

According to Kus (1985:184), the first stage start when the queer person recognizes their true identity as queer, a transformation that might harm the person’s self esteem. Fox and Warber (2014:87) connect this stage to the use of SNS, stating that queer people in this stage usually hide their identity as queer on SNS. This is done out of a view of their online communities as dominated by heteronormativity and of a fear of the medium “outing” them without their consent. Fox and Warber (2014:88) describes how the queer person in this stage practices what Kus (1985:185) would describe as “closet passing”. According to Fox and Warber (2014:88), the person obey the rules of an heterosexual self-presentation and tries to highlight their illusion of being heterosexual, for example by only allowing tags in pictures with pictures of the opposite gender. The same result shows in the study conducted by Owens (2017:442) where queer people who were not out yet maintained an online identity as a heterosexual person.

According to Kus (1985:185), the “closet passing” is the hallmark of the second stage of coming out. This is when the queers conceals their true identity and pretends to be straight while exploring what it means to be queer. In sum, the criterion for stage two is changing the attitude about queer people whilst still not be completely accepting it as a positive aspect of oneself. In stage two, the queer person also starts giving hints about their true identity (Kus, 1985:187). This shows in similar ways on SNS where queer people starts giving hints about their true identity, e.g. by changing their sexual preferences to “both men and women” (Fox & Warber, 2014:88).

The third stage, acceptance, is what it sounds like. According to Kus (1985:188), this might be one of the more joyful stages of them all, but is often only seen in retrospect. The

criterions for stage three is the acceptance of being queer as something positive rather than something negative. Fox and Warber (2014:89-90) describes how queer people in this stage start testing the setting for coming out to a wider network whilst showing a greater

acceptance of their queer identity. The queer person starts to connect with other queer people online and is more willing to share and like content connected to being queer, for example by showing that they support gay rights without saying that they are gay. They also used the function of filtering what friends who got access to their shared content in order to minimize possible homophobic comments. The same behavior showed in the study by Owens (2017:440) where queer people filtered who got to see specific content that they posted online. This is also explained by Duguay (2014) who talks about context collapse, a state that happens when someone’s online identity unintentionally get merged into the persons offline identity. In other words, when someone gets unintentional “outed” offline based on content they create and publish online. Further, SNS can also be a tool for testing what it is like to come out. In the study by Owens (2017:440), queer respondents said that “its less risky to indirectly come out on Facebook than it is to directly tell his friends on the social media

website” with the notion that other people are less willing to publicly confront them offline

about their queer identity on SNS.

In the fourth and final step, actions on the basis of self-acceptance can be either highly visible or hidden. In this stage, full disclosure of a queer identity often occurs and is seen as the queer allowing others to be more aware of whom they are. The queer can become a role model for younger queers, as well as an educator for the straights (Kus, 185:190-191). This is also shown on SNS, whereas the queer person is comfortable with being public about their queer relationship and being queer in general (Fox & Warber, 2014:90-91). The queer people who are out are also willing to educate others and would not hesitate to either get in a discussion to defend queer people, or simply un-friend homophobic friends. Owens (2017:437) study shows that SNS sometimes are used as tools for actively coming out to the public and that SNS can be seen as transformative tools that has changed the coming-out process for some queer persons in a significantly way.

In sum, previous research shows that queer people change their behavior, both online and offline, depending on where in the process of coming out they are.

SNS as a resource for information and peer support

A recurrent finding in previous studies is that new media and SNS are important in queer peoples lives, both in the process of coming out, but also in their process of building and exploring identities. Craig and McInroy (2014:100) identified five themes in their study that influences queer peoples aims of using SNS; (1) access resources, (2) explore identity, (3) find likeness, (4) come out digitally, and (5) potentially expand identities formed online to their offline lives.

In the study by Craig and McInroy (2014:101), almost all participants mentioned SNS and new media as an important resource of information. The information online differs from information offline in terms of an experienced more diverse and realistic selection. Further, gathering information online instead of offline minimizes the risks of being

unintentionally outed, exemplified by borrowing books from the library with a risk of being seen. The anonymity that SNS offers also affects the possibility for the queer people of exploring identities. They can be creative with their creation of self without pressure or expectations from their offline lives. They also find likeness on SNS in forms of role models and by taking part of others stories online about being queer or coming out. Jesse

and Ralston (2016) showed a similar result in their study, where respondents that had come farther in their process of coming out demonstrated a will to “pay back”, these people were keen on later sharing information themselves to help others. Further, the study by Ybarra, Mitchell, Palmer and Reisner (2015:134) showed that online friends are a key support for queer people. SNS also allows for queer people to start their process of coming out, either anonymously or more public. After testing their identities online, they often get expanded to their offline lives. Respondents in the study by Craig and McInroy (2014:102-105) noted how their online activity helped them prepare for an intersection of their online identity into their offline identity.

The study by Bond, Hefner and Drogos (2008) showed that young queer people are more likely than old queer people to use SNS over interpersonal communication or mass media in their information seeking during the process of coming out. Their study also suggests that mediated forms of communication could benefit sexual exploration among queer people. The study by Gray (2009) focused on a selection of rural queer youth and their use of new media and SNS. The result showed that the queer youth in rural areas grew up with a queer representation in traditional media that they felt were stereotyped and not “real”. The result showed that representations of realness in information and stories online were crucial for them in the process of exploring, building and coming out with their queer identities. This is also showed in the study by Bond, Hefner and Drogos (2008:41) where queer people feel like the pictures about queer people that circulate in more traditional media are often stereotypical and not real.

In sum, previous research shows that queer people use SNS in different ways and with different aims. However, previous research also shows similarities in the ways queer people use SNS and that SNS is an important resource for queer people.

Theoretical Framework

The following theoretical approach will be used to analyze the empirical material collected in this study. In this chapter, theories that will permeate the study and specific theoretical terms will be presented and explained. These theories are used as a framework to position the study in the field and affect the way possible phenomena are examined and presented as results.

Representation within different cultures

Since this study is going to focus on how queer people uses social media in terms of exploring and building identities, representations is something that will be discussed. In order to talk about representations, I need to define what this concept stands for. To do this, this study is going to use the definitions by Stuart Hall (1997). Throughout this thesis, the study’s research questions will be examined as a process between representation and culture, which leads to a natural approach for using the model “The circuit of culture”.

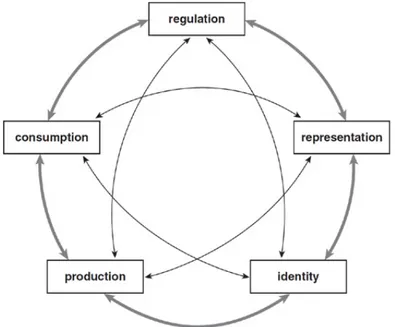

Figure 1. The circuit of culture. Paul Du Gay (2013).

Du Gay (2013:xxx) explains the model as five major cultural processes that intertwine, which are representation, identity, production, consumption and regulation. Together, they form the circuit of culture, which is necessary to use to make sure that cultural artifacts or texts are studied in a suitable way. The circuit of culture can be used regardless of where in the circuit the analyze starts, as long as all steps in the circuit are followed all the way around. The steps follow each other and all steps need to be considered in order to examine how something, for example, is represented, which social identities that are connected to this, how it is produced, consumed and what mechanisms that regulate its distribution and use.

Based on the circuit of culture by Du Gay (2013), Hall (1997) highlights representation as one of the central practices that produces culture. To summarize Hall (1997:17) and his definition of representation and its connection to culture, culture is about shared meanings and meanings are constructed through languages. The language helps us interpret the world as it works as a representational system. Language can mean different things, from words

and body language to pictures and symbols; They don’t have a fixed meaning but are encoded and decoded by members of societies, which means that the meaning can shift between both different cultures and individuals within the same cultures (a.a.:45).

Hall (1997:19-23) further elaborates his definition of representation as how people within a culture give meaning to people, object and events by how they represent them. This could be the language and the images they use and produce about them, the emotions that they associate with them and the way they get classified and valued. This way of coding and decoding takes place in every social and personal interaction, but also in different kinds of media. In order to think and feel about the world in similar ways, members within a culture need to share similar cultural codes. The collective notion and understanding of the cultural codes is what gives meaning and lead to an identification with a community (ibid). This approach to representations, as varying in its meanings and interpretations between different cultures, will be an important angle to the concept representation in this thesis. When the relationship between how queer identities are looked upon, explored and constructed, the notion about how this might be interpreted within different cultures will be considerate.

As an addition to this, Thompson (1995:207) explains how representations in a mediated society create a self-reflexive process of self-formation and identity building. The individuals get access to mediated information and images via media that helps them expand their identities from not only relying on local representations. The building of an identity is based on symbolical images within ones culture and the identity building does not end or finish, but could be seen as a constantly ongoing process.

Further, Hall (1997:22) talks about the discursive approach within representation as the notion of effects and consequences of certain representations. Representation in a culture is also about power relations that affect and define how certain representations construct identities and subjectivities. Meanings can be of both a negative and a positive kind, often in binaries, and defines what is normal and what is not based on power relations (Hall, 1997:25). This is called differentiation and is, according to Hall (1997:225-226), mentioned as one of the most important aspects in terms of representation. We need the binaries to make sense of the world in terms of classifying, but this division can also create problems. Thus, there are few binaries that are neutral and there is almost always a relation of power between them where one pole in the binary is dominant, the existence and meaning of one often excludes the other. A classic binary division is male-female, a categorization that not everyone might identify with. In this way, differentiation is also a dangerous aspect, regarding its underlying power relations and the cultural creation of meaning and of who is fitting in it and not (ibid). This builds upon the notion of the heteronormativity, where the binary power relation between heterosexual/other sexualities relates to various structures and power relations in society that works as gatekeepers in keeping heterosexuality as the normal and desirable sexuality. The power relations within different representations will be an important approach in this thesis when discussing representations and their different cultural meanings.

Gender construction and performative acting

As shown in previous studies, queer people often feel misrepresented; that pictures, representations and assumptions circulating around them in society are one sided and stereotypical. Based on this, both feminism theory and queer theory has been regarded as necessary to find a way of enhancing representations of various genders. Queer theory

emerged from the critique that previous research on homosexuality presupposed solid categories about gender identities (Rollins & Hirsch, 2003) Queer theory could be used as a tool in order to apply critical thinking about, e.g. gender norms, and to examine

heteronormativity (Rosenberg, 2002). In her book Gender Trouble, Butler (1990:2) focuses on how gender is structured and how women have been structurally misrepresented in the opposition to men, based on the notion of heteronormativity.

Like Hall (1997), Butler (1990) describes how language is a normative function, here in the process that makes assumptions about what it means to be a woman. In this thesis, I argue that the term and subject woman can be replaced with or include the term queer. This builds on how Butler (1990:31) talks about a universal patriarchy where the male and heterosexual have been the dominating and preferred, the female and not heterosexual depends on a binary division and parting from the dominating. The construction of genders and identities happens in the notion of the binary division between the genders (Butler, 1990:60-62). Further, gender divisions can’t rely merely on the binary opposition between male and female, one also need to take notions of various components that affect a gender and an identity, such as race, class, age, ethnicity and sexuality, in order to

complete a meaning of an identity (Butler, 1990:20-21). In this thesis, female and queer will be seen as the predominant notion of the male.

Butler (1990:9-12) explains how gender is assumed to be the cultural interpretation of a sexed body, but how gender can’t be assumed to follow the binary division as the

biological sex is assumed to have. A body is just a passive medium where cultural meanings are externally positioned and inscribed. In the same way, sexuality and desire does not follow from either gender or sex (Butler, 1990:185). Butler (1990:185) explains the construction of gender in terms of performative acting, signifying absences that suggest organizing principles of both gender- and sexually identities. These performative acts are produced and visible on the surface of the body, sustained through corporal signs and other discursive means, and could be acts, gestures, and articulated and enacted desires (ibid). Performative acting will be an important framework for the thesis analysis, where identity building and identity performance will be looked upon as a performative acts.

Further, Butler (1990:185-186) argues that the body gets gendered based on its performative acts, suggesting that it has no existential status apart from its acts, which constitutes its reality. The interior gender is produced on the surface of the body and creates the visible illusion, interpreted by society and oneself based on discourses and the frame of binary genders and reproductive heterosexuality. Gender is a fabrication and can therefore be neither true nor false; they are only produced as a truth based on the discourse of a primary and stable identity. Butler (1990:190) also explains the body becoming a cultural sign of gender as a survival strategy within compulsory systems of binaries. Those who fail at doing their gender “right” are regularly punished and discrete genders

performed “right” according to cultural notions of binaries are humanized within our contemporary culture. Thus, gender has no natural and given meaning without the

production, we have created a collective agreement of the polar genders as cultural fictions that we believe in and follow. Gender is also an act in the terms of its repetitions in the aim of maintaining ones performed gender, the repetition and re-experience of a set of meaning is socially established and becomes a ritualized form of legitimation of gender. In this way, the concept of gender is also a social temporality constituted in time and space through what Butler (1990:191) talks about as a stylized repetition of acts.

Presenting and expressing the personal façade

In his book The Presentation of Self in Every Life, Goffman (2009) present and explain the self-presentation theory. According to Goffman (2009:11-15), we always collect information about others in our interactions. We both apply the information we have and collect new information by identifying clues in the others behavior out of personal gain and practical reasons. Building on the theoretical frameworks by Butler (1990), Goffmans (2009)

theoretical approach will be used in this thesis to give a better understanding of how and why performative acts are performed by queer people in different settings.

According to Goffman (2009:15-18), an individual who appear before others will always affect the definition of a situation via ones actions. This could be intentional and calculated to induce a specific reaction, unintentionally calculated, or intentional since ones social group or status demands these actions. The others can either be affected according to the intentions or dismiss them and misinterpret the situation. The collective

understanding of a communicative situation is constructed via a common understanding and agreement of the definition of an individual’s actions. This is what Goffman (2009:18-21) explains as the preliminary functioning unit, and explains as varying between different types of settings and situations.

Further, the social agreement of the realness of the presentation of the self is crucial. If the situation and setting is convinced that the individual is being ones true self, the

individual often feel compelled to keep that presentation. The individual can also have a calculated intentional to present a version of oneself to convince the others that one is a type of person as a way of fitting in or reach certain goals. The latter could result in a feeling of the individual as not being ones true self. However, this is often done to care for ones own safety and best (Goffman, 2009:25-26). As an addition to this, Goffman

(2009:29-32) also explains ones façade as a part of an individual’s actions and realness. The

personal façade is referring to the details in ones’ appearance beyond ones’ actions, such as

clothes, gender, age, ethnicity, size, speech pattern, facial expressions, gestures and alike. Sometimes a façade, in relation to actions, can result in a decreasing realness of a person, if they are not connected through social norms and expectations. Goffman (2009:38) explains that a group of individuals tend to emphasize specific things in their way of acting,

depending on what situation they are located in with which others. On the other hand, facades can be a way of creating and belonging to a collective representation, where the individual can find abstract and stereotyped expectations of how one should act. The individuals are in this situations using something that Goffman (2009:35) terms as dramatic

realization, a characteristically way of using signs that highlights and confirms actions with

facts about oneself that would otherwise be hidden.

Goffman (2009:39-41) also talks about the idealization in which individuals’ actions take place. It could be explained as how actions are socialized, formed and reformed to fit the expectations in the society in which the actions take place. This can be shown in how an individual tend to incorporate socially valued actions and morals in ones behavior. Depending on shifting social settings and norms, the self-representation of an individual will shift (a.a.:52).

In sum, Goffmans (2009) approach will tie together the theoretical frameworks from Hall (1997), Du Gay (2013) and Butler (1990) in the hope of a better understanding of how culture, representation and performative acts, in a concrete way, are connected through queer peoples actions and behavior on social media.

Methodological Design and Execution

This chapter follows an account of the method that was used for collecting the empirical data for the result and analysis. This is followed by a short presentation of the respondents that participate in the study. The chapter ends with ethical considerations and a discussion about the study’s validity and reliability.

Qualitative interviews

According to Trost (2005:13-14), the aim of the study should be decisive for what method that should be used. A qualitative study is reasonable for the aim to understand the way people reason and acts, also to distinguish similar or varying patterns in relation to this. Based on this, a qualitative approach is relevant and useful for conducting this study in order to examine how queer people themselves are discussing their use of SNS in order to be able to reach the study’s aim and answer the study’s research questions. The majority of previous studies presented before is conducted with a qualitative approach in the choice of methods, which further motivates the qualitative approach in this study since one part of the aim is to broaden the understanding and add knowledge to previous studies in the field.

Since this study is going to focus on queer people and their self-perceived experiences of building and exploring identities by using SNS, a deeper understanding of them is necessary. This motivates the usage of qualitative interviews as the main method in the qualitative approach made in this study. The focus in this study is on personal experiences that could point out a path and maybe some patterns in how SNS are used by some queer people, rather than showing a general result of how queer people are using it. Kvale and Brinkmann (2014:17) explain that the method of qualitative interviews aims to understand the world from the aspect of the respondents; it develops meaning from their experiences and uncovers their lived world. Further, Ryen (2004:77) explains that the central point is the possibility to see the respondent’s way of seeing and interpreting the world, not to examine how many who are experiencing and seeing it in the same-, or in a different way. With the qualitative interviews, it is possible to get a deep understanding of the

respondents. Further, Larsson (2013:55) explains that qualitative interviews are suitable within the field of media and communication when the aim is to distinguish how different groups in society get information and communicate around a subject or theme.

The knowledge that is produced in an interview can be evaluated in different ways, depending on which epistemological approach that is used. This study uses a

phenomenological approach, which in qualitative methods focuses on the interest of understanding social phenomena from the respondents’ own perspectives and their ways of explaining the world. Since the experienced life world from the respondents is what is interesting in this study, a phenomenological approach will work as an inspiration for the method used in this study. The focus in phenomenology on the meaning in the

respondent’s life world has helped to clarify and structure the understanding of a qualitative interview. Their assumptions of the reality of the world are what the reality is (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2014:44). In a phenomenological method, the focus is to describe the respondents’ sayings and perceived life world to such and fully and precisely extent as possible, rather than describing and analyzing the respondents sayings and life worlds. This could further be explained as an open description whereas I as a researcher need to be active in listening and seeing and be open for nuances in answers and findings (Kvale &

brinkmann, 2014:42). Hence, the aim of using this approach is to give a true picture of the respondent’s experiences.

Kvale and Brinkmann (2014:45) further explain the method of qualitative interviews, with inspiration from phenomenology, as semi-structured. As an extension to this, Trost (2005:50) talks about the interview guide as a tool in a qualitative interview. The

respondent should lead the conversation in terms of order of subjects and partial aspects in the questions areas. In a semi-structured interview, an interview guide where the main topics are listed could be useful to let the respondent lead but without losing control over what needs to be asked by the interviewer. In this study, an interview guide has been used, accordingly to the recommendations from Trost (2005).

Sample of respondents

In the same way that a study’s aim should decide which methods that should be used, Larsson (2013:61) explains how whom that should be studied should led to what samples of respondents that is necessary. This is based on the study’s aim and what the sample should represent. Hence, the sample of respondents in this study is young queer people in Sweden. In order to conduct this study, five respondents have been interviewed. The respondents were found via a post posted on my private social media where I asked for queer

respondents for a study surrounding queer identity and social media.

The sample was partially made via a strategic sample, which Larsson (2013:61)

describes as a choice of respondents that will represent a broad selection of the phenomena studied. In this study, respondents within various ages within the age span were chosen. The respondents are also representing different identities and sexualities within the queer spectrum. This sample was actively and subjectively chosen with the ambition of

representing a sample of respondents with different gender identities and sexual

preferences. However, all of the respondents were cis-gendered and the sexual preferences amongst them were mostly homo- or bisexual. This was a result of limits in terms of time for the study, but also under consideration for that the respondents themselves reached out to me for being a part of the study.

Eleven respondents in total signed up for the study, but the empirical data collection was completed after five interviews. After that number, the empirical data was showing signs of being saturated and I reached the conclusion that no more new aspects would be expected from conducting more interviews. Kvale and Brinkmann (2014:156) explain that the necessary number of respondents varies depending on what kind of material that are needed and wanted and that no more respondents are needed when the collected empirical data is saturated. Further, Larsson (2013:63) explains that a strategic selection enables the selection to successively grow and that the empirical material could be further expanded with more interviews if necessary. If this would have happened, further and more interviews would have been conducted.

Even though the aim of the study was to examine a broader age span of young queer people in Sweden and their usage of social media, the respondents in this study turned out to consist of a relatively homogenous group age-wise. Instead of ranging from the desired age span of 18-28 years, the respondents were all in the age 23-27 years. The more

narrowed age span of respondents is a result of how the respondents were recruited, via my private social media, where most of my friends and followers are within the same age span as me, hence 23-27 years old. This limitation of the sample will affect the result since many of the respondents identified their process of coming out as “pre-internet”. Different

answers and usages would have been discussed if the respondents have been younger and had used Internet more regularly even before starting their processes. Due to limits in the study, such as time, this was still considered as an interesting group to focus on. If the time span for the study had been longer, a more diverse group considering factors such as age, sexual preferences and gender identities would have been preferred.

As briefly described before, the respondents were chosen with the aim of representing different gender identities and sexual preferences. All of the respondents who agreed on being a part of the study described their age, gender identity and sexual preferences to me. Based on this, I then narrowed down the sample from eleven to five persons based on their self-identification and age. The sample of respondents resulted in the following:

• Respondent 1 (R1): 25 years. Cis-man, homosexual. • Respondent 2 (R2): 23 years. Cis-woman, bisexual. • Respondent 3 (R3): 25 years. Cis-woman, homosexual.

• Respondent 4 (R4): 26 years. Cis-woman, bisexual/pansexual. • Respondent 5 (R5): 27 years. Cis-man, homosexual.

Conducting the interviews

The interviews with the respondents took place in different settings, where most of them took place in private rooms in a public building. Two of the interviews (R3 and R4) were conducted over telephone. Independent of where the interviews were conducted, the interviewer and the respondents were alone in the interview situation. The interviews took between 30-60 minutes and ended after both the interviewer and the respondent

experienced that the material was saturated. The respondents were, after the questions, asked if they had something to add. The interviews were, with consent from the

respondents, audio recorded. As a complement to this, the interviewer took notes during the interviews for the purpose of remembering specific emotional or other physical reactions from the respondents, e.g. body gestures, facial expressions and alike.

After the interviews, the recorded material was transcribed, and later sorted in to different categories, depending on the content in the material. These categories were, e.g.

online activity affecting offline life, finding likeness online and searching for information. These

categories were further themed and placed in new categories, based on the stages of

coming out that form the base for the presentation and the analysis of the result in the next chapter.

The interviews and the way the respondent answers were compared to the interviewers own experiences could be experienced as what Kvale and Brinkmann (2014:49) describes as an interpersonal situation. In some parts of the interviews, discussion with new

perspectives appeared, for both the respondents and me as the interviewer. Further, the interviews partially resembles with each other in terms of structure and answers since the questions were formulated in similar ways in the interviews. However, the latter interviews were more specified and to a greater extent followed up on the answers from the

respondents. This was made possible as a result of the interviewers knowledge from the earlier interviews. As an addition to this, I myself identify as queer, something that I used as an asset in my role as an interviewer. My previous knowledge about the queer sphere helped me understand expressions and situations described by the respondents. The respondents were during the interviews informed about my queer identity, something that

they themselves expressed led to them feeling safer about being open about their experiences and thoughts.

Since the interviews were very open, with just a few overall questions in a semi-structured approach, the answers and discussions were often long and the respondents could get lost in trying to explain without making their own conclusions. Thus, an

interpretation of the meaning was necessary, in this case by conducting a form of meaning concentration. This could be explained as summarizing the respondents’ answers with central themes that have a significant role, and by doing so, get a more clear picture and understanding of what can be used from the interviews (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2014:245-247). Once again, this was a situation were I found my previous knowledge and experience from the queer sphere as an asset that helped me concentrate and understand the

respondents answers.

Validity, reliability and generalization.

The ambition with this study was to be able, to some extent, give an insight to how queer people are using SNS to build and explore their identity. Two important quality criteria in order to achieve this are validity and reliability (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2014:264). Validity means that the study examines the asserted questions. Reliability means that the method is well defined to the extent that the study could be repeated and come to the same results.

According to Alvehus (2013:127), it is important to distinguish between a theoretical and empirical generalization where an empirical generalization is about, from a limited selection and field, being able to generalize about these specific respondents in this specific field. Theoretical generalization on the other hand refers to the possibility to reach a generalization based on similarities and differences between the conducted study and previous studies (Kvale, 1997:210) This study have been examining a specific sample of respondents, but with a pervading comparison with both previous research and theory. Thus, this study has been able to give a theoretical generalization of the result and analysis. Further, since the study’s’ approach has been chosen with contemplation and in order to reach the study’s goal, the study’s validity increases. The phenomena that this study aimed to study are what have been studied. However, the interviews, how the questions have been asked and how the answers were concentrated have been a subjective choice and have been affected by me as the interviewer. With this in mind, in order to minimize the risk of relying on merely subjective interpretations, I as the researcher have, e.g., consciously formed the questions to minimize the risk of asking leading questions.

Further, the interviews were conducted in Swedish and have later been translated to English. This has affected the interpretations and the nuances in the language from the respondents since some statements have a different impact and/or meanings in different languages. However, in order to minimize the risk of inaccuracy in the translated answers, the respondents have confirmed that their answers correlates with the empirical results from the translated interviews.

The time limit for this study has made it both impossible and unsustainable to conduct an extensive study that would give a completely generalizable result about all queers in Sweden. However, this study might be an indication of how queer people in Sweden can be using social media as a part of their exploring and building of identities where this study shows how these specific respondents in this study are using social media for this.

Ethical considerations

As Kvale and Brinkmann (2014:33) explains interviews as a research method are permeated with ethical questions and considerations. The knowledge that is produced in such a setting is dependent on consent between the respondents and the interviewer and their social relationship (ibid). This has been considered throughout the conduction of the study and both precautions and active choices in the moment have been taken to make the

respondents feel as safe as possible, as an example by sharing the interviewers identity as a queer person with the respondents.

Before the interviews, the respondents were informed about the study, its aims, the theme in general and its purpose. They were informed that the participation study was voluntary and that they could decide to leave the study at any time. A document with the same information was given to them for them to keep. The respondents were informed that their participation was purely confidential, that their responses were anonymous and that their identities would not be able to be reveal from their answers. To protect the respondents’ integrity, their identities and names are therefore not presented in this study. Larsson (2013:75) explains that a confidential treatment contributes to both trust and openness in the relationship between the interviewer and the respondent. If the respondents know that their answers will be treated with caution and that they will be anonymous in the study, the chance of them answering truthfully and with their innermost thoughts and feelings increases. Since the study treats subjects such as identity, gender and sexuality that could be sensitive subjects, only the interviewer knows the respondents’ full name and identity in this study. The material from the interviews in form of recordings and transcriptions has also been handled with care and in an anonymous way, e.g. that the respondents’ names have not been included in the transcripts. After the study is completed, the collected material from the respondents in the form of recordings and personal data will be completely deleted. Material in form of transcriptions will be kept for one year in order to be able to strengthen any questions surrounding the result and analysis in this study. This aligns with how Malmö University proposes the handling of personal data in a study (Malmö University, 2019).

Analyzing the Results

In the analysis, the theoretical perspectives as well as results from previous research presented above are used to understand the results. The empirical material is analyzed based on themes that showed in the interviews with the respondents and will focus on the concepts from the theoretical section such as culture, representation, performative acts and the presentation of self. In order to clarify occurring themes and perspectives, and focusing on the phenomenological approach, a selection of quotes by the respondents from the transcribed interviews will be presented. Further, in order to reach the study’s aim and answer the study’s research questions, these are what the analysis ground is based on. The themes in the result and analysis are somewhat based on the four stages of coming out, identified by Kus (1985) and Fox and Warber (2014).

Stage one, accepting and developing a queer identity, online and offline

All of the respondents see themselves as heavy users of Internet and social media, whereas Instagram is the platform that they use the most, followed by Facebook, Twitter and Snapchat. They talk about their process of exploring and developing their identities as queer people as both a process online and offline. The social media platforms focus during the interviews was mainly on Instagram, Facebook and Internet more generally, since these were the platforms where the respondents were most active. The respondents also describe their process of developing their identities as pre-Internet and social media.

R2 explains her beginning of the process of developing an identity as a bisexual woman as disconnected from Internet and social media. She had Internet access but first learned about other sexualities than heterosexuality offline. When she was about 12 years old, she heard about lesbians in her community and learned that living with someone of the same gender was possible. After that, she realized that bisexuality also existed, which she describes as a big moment in her life.

Reading this in relation with Hall (1997:19-23) and his definition of representation, one might argue that R2 and her getting presented to a, for her, new word with a new meaning, might have led her to discover a new representation. By finding a new way of decoding her identity, a new perspective opened up for her in terms of giving her a new meaning of coding herself as a type of specific identity as a person within the culture. She explains how the word bisexual changed the way she looked upon herself and others, how she got a word to explain how she felt and thereby made it possible for her to

communicate herself and help others interpret her in the “right” way. This answer from R2 somewhat correlates with the answer from R1. He also talks about starting his process offline, using Internet only to find some information to validate his feelings and thoughts. This might be an example of how Hall (1997:22) describes how certain representations could help in the construction of identities and subjectivities. By finding representations online that confirmed R1 and his experienced identity as valid, and by finding others that felt the same way, R1 could continue building his subjective identity, knowing that it was somewhat accepted within his culture.

In contrast to this, R3 states that she used SNS in a more active way in her process of developing and creating her identity as a lesbian woman. The questioning of her identity as

a heterosexual person begun early in her life, but it took a long time for her to accept it. However, she describes herself as using Internet regularly, liking how Internet could offer her information about anything. She started to think about her identity offline but didn’t want to ask someone in her real life about it. This naturally led to her moving towards -Internet and social media to find both information and others to talk to about her thoughts surrounding her identity.

I would say that social media, or at least Internet more generally, have been extremely important to me in my process of understanding and accepting myself as a lesbian. [...] It started with me Google stuff like ’lesbian quiz’ or ’am I gay?’ and doing all tests and quizzes I could find regarding this. I knew back then that the tests were 100% non-scientific, but I just had to channel my thoughts and wondering somewhere, like my insecurities about it. […] I knew that lesbian was the truth about me, but I couldn’t be honest with it in the beginning. I think the test were some sort of self-validation for myself. They are kind of stupid, but they helped, a lot.

R3.

This quote from R3 indicates another need of the content and information she could find, in contrast to R1 and R2; she looked for it and found it mainly on the Internet. Reading R3 in relation to both Hall (1997) and Du Gay (2013), the answer might indicate a shift in R3s views of the cultural meanings toward different representations. The self-validation that R3 talks about might be an example of how her identity got a more positive connotation after she found representations of it online. Further, this could possibly also be explained as a sort of identity building in terms of differentiation, but instead of finding differentiation from the queer community, R3 built her differentiation in the division from the

heteronormativity. Connecting this to the circuit of culture, the representation often follows by and affects identity. R3 continues describing how she used Internet and social media in her process of developing her queer identity as extensive. She searched for and read all content and information surrounding lesbians that she could find, most often using the incognito-function in order to be anonym, she explains how she worried about

someone finding out about her questioning of her sexual identity, and revealing it to others before she was ready for it. This could be an example of how Fox and Warber (2014:87) describes how queer people in the first stage of coming out often hide their queer identity online from the fear of being outed without consent, something that Kus (1985:185) defines as “closet passing”. When asked if R3 then knowingly tried to pass as a heterosexual, she answers:

Yes, indeed! I always had a boyfriend during this time. Both because I so badly wanted the lesbian side of me to disappear, but also to be able to dismiss any possible question about me being homosexual if someone saw my search history.

R3.

This aligns with the findings in the studies made by both Owens (2017) and Fox and Warber (2014), where they found that queer people who wasn’t out yet felt compelled to maintain a heterosexual identity online to not be outed by the machine. Even though Owens (2017) and Fox and Warber (2014) bases their results more on the activity on social media, this answer from R3 could indicate that this also affects how queer people, whom are not yet out, maintains a heterosexual image of themselves in all settings.

Further, R3 explains how a lot of the content she found online was pure porn, something she found to be scary and not fully the real image. However, she also stumbles upon, what she describes as, more ”real” images of lesbian women.

[…] The most representations I found, apart from porn, were celebrities like Ellen DeGeneres. But she was like famous and stuff and lived in the USA and I thought that in order to be openly lesbian, you had to be famous and loved in order to be validated. […] However, later on, I managed to find pictures and representations of more ’real’ lesbians. […] I experienced such happiness when I realized that being a lesbian was more than just being a girl in a pornographic movie. That people actually lived as lesbians, for real.

R3.

Reading this quote in relation with Goffman (2009, 25-26), this might indicate what he describes as the realness of presentations. Whilst Goffman focuses more on the

presentation of the self, this on the other hand describes how R3 searched for realness in the presentation of others. The way R3 interpreted the presentation of other lesbians online of not being real could however be an example of how Goffman (2009:15-18) explains how a preliminary functioning unit can affect the impression of another. Further, the way R3 feel about the representation not being real might be an effect of her somewhat identifying with the definition of lesbian, but not agreeing on how she feel about it in contrast to what definition that is presented to her. She does not agree to the constructed understanding of what a lesbian is or isn’t. When she later on found a, to her, more real picture of what a lesbian is or isn’t, she found a presentation that followed her

interpretation of the preliminary functioning unit.

R4 talks about using SNS from an early age to explore her queer identity. However, even if she explains SNS as important for exploring and building her queer identity, she didn’t thought about it as a way of exploring her identity back then. R4 explains how she in the age around 14 talked to people who she didn’t know on MSN. She identified herself within a subculture, emo, and talked with others within this culture. According to her, she could freely disclose her identity as bisexual to them without being questioned about it.

Within the emo-culture, it was very common to be bisexual. You were more strange if you were heterosexual than if you were bisexual, it was taken for granted that you were bisexual.

R4.

Reading this quote from R4 in relation with Hall (1997) might show signs of the different cultural assumptions and representations within different cultures. R4 talks about how the cultural assumptions within the emo-culture were that everyone who belonged to the culture was bisexual. The shared meaning about bisexuality within this culture was that it was normal and assumed, which could be seen as an example on how Hall (1997) describes how cultures share different cultural codes.

Alike R3 and R4, R5 also talks about the usage of social media as very important in his exploration of his identity as a homosexual man in a young age, explaining how online communities for homosexual men were the first places where he meet others alike him. He explains the culture on these communities in similar ways as R4 talks about the emo-culture, as a place where another sexuality than heterosexuality was taken for granted, disconnected from the heteronormativity. R5 explains how he always knew about his

sexual identity as a homosexual man, but how he oppressed the feelings due to the negative tonality about gay men that he experienced, which affected his mental health in a negative way. However, these feelings and thoughts turned him towards the Internet, which worked as a confirming center of information. This lead him to feel better about himself by

collecting information online that showed another image of homosexuals, as normal and okay. Like R1, he used SNS as a validation of his queer identity.

Stage two, the coming out story, not so digital

The first time I came out, I think I was around 21-22 years old. I fell in love with a girl, like really in love, head over heels and all that. And for the first time I realized that this was how love could feel like. […] The more I allowed myself to, like, be a lesbian and flirt with girls, the more I realized that it wasn’t me that was the problem, it was the boys.

R3.

This quote from R3 shows how she felt more and more pleased with the identification as a lesbian woman the more she allowed herself to practice her identity. This might be an example of how Butler (1990:191) explains gender as a performative act in terms of repetitions. The way R3 repeated her identity as a lesbian woman let her re-experience her set of meanings and establish her form of her performed gender and identity.

All of the respondents saw themselves as out and open with their identities, however, the level of outness varied. A common answer from the respondents was that they felt completely out to their close friends, but not in other social settings such as at work, in school or in social groups with people that they didn’t know well. They felt safer with close friends, already knowing that their friends were supporting queer people. At work or in school however, they didn’t know how others would react to them being queer. This might be an example of how Butler (1990:190) describes the cultural and social sign on gender. The respondents here show a fear of being, how Butler (1990) describes it as, “punished” for not performing their gender right, not following the norm of heterosexuality. Further, it was unusual among the respondents to come out openly as queer on digital or social media. R1 described how he both saw himself as very open with being a homosexual man; but that it could shift quick depending on what settings he was in. Once again, an example of the fear of being punished of not performing ones gender “right”. R5 evaluates the fear of not performing his gender right by explaining how shifted settings in his offline life

affected his process of coming out. He started a new school where he felt like the common notion of what it meant to be homosexual were more positive and accepted, apart from his old school. R5 explains his behavior in his old school as following:

Homosexuality was seen as bad as pedophilia in that school. There were always bad words about queer people. I lived under a complete denial during this period, thought about it as a phase that would pass if I ignored it long enough. […] I just tried to not have any personality that could be interpreted as gay and stay under the radar.

R5.

Further, R5 explains how he felt like he could start over in his new school, exploring his identity more openly and be himself. He also explains how the friends he got in his new school were “more queer”, where some of his friends also identified themselves as either bisexuals or homosexuals. However, he first came out on the Internet before telling his