SOCIAL JUSTICE,

GLOBALISATION AND

SEX TRAFFICKING

- A qualitative study on support to victims

of the sex trade, in an Indian regional context

PETRA SPENCER

SOCIAL RÄTTVISA,

GLOBALISERING OCH

SEXHANDEL

- En kvalitativ studie om stöd till sexhandels

offer, i en indisk regional kontext

PETRA SPENCER

Författare: Spencer, P.Titel: Social rättvisa, globalisering och sexhandel. Undertitel: En kvalitativ studie om stöd till sexhandels offer, i en indisk regional kontext. Examensarbete i socialt

arbete 30 högskolepoäng. Malmö Högskola: Fakulteten för hälsa och samhälle,

Institutionen för socialt arbete, 2014.

Sammanfattning: Karnataka har visat sig vara en populär destination för människohandel. Tyvärr faller många migranter och andra offer för människohandlare, ofta på grund av globaliseringens mörka sidor. Det övergripande syftet med studien var att nå en bättre förståelse av tillgängliga stödverksamheter för sexhandels offer i Karnataka, och utmaningar därefter, för att bättre harmonisera tjänster och svara mot offrens rättigheter.

Forskningsmetoden bestod av kvalitativ karaktär med etnografiska inslag, med fältarbete som bedrivits i den indiska delstaten Karnataka. Studien ger en

kartläggning av stödtjänster (främst rehabiliteringshem) för offer, samtidigt som den undersöker utmaningar i relation till politiska beslut, strategier och

implementering. Situationen i dag målar upp en bild av förvirring när det gäller ett fungerande stödsystem. I allmänhet var rehabiliteringshemmen ohygieniska med dåliga sanitära förhållanden med begränsad hälso-och sjukvård. Hemmen var även otillräckliga vad gäller säkerhet, samarbete och samordning, samt utbildning och erfarenhet hos personal. De ’skyddande och rehabiliterande hemmen’ (Ujjawalas) är inte tillräckliga nog vad gäller ett stödsystem, och de fokuserar inte enbart på offer för sexhandeln. Således bör det finnas specialisthjälp (med hälsokliniker), särskilt eftersom offer för sexhandeln ofta behöver specialiserad vård,

psykosocialt som fysiskt. Ett socialt rättvist stödsystem bör förstå och värdera mänskliga rättigheter, samt erkänna värdighet hos varje individ. Om det finns en brist på ett fungerande stödsystem, och framför allt ett holistiskt

sektorsövergripande synsätt, riskerar offer fysiska såväl som psykiska problem. Ett icke fungerande stödsystem kan också förvärra socioekonomiska orättvisor, speciellt eftersom offer riskerar att hamna i fattigdom om de inte integreras tillbaka i samhället. Som en övergripande socioekonomisk och politisk fråga undergräver det hälsa, trygghet och säkerhet, inte bara hos de människor som är direkt berörda utan samhället i stort.

SOCIAL JUSTICE,

GLOBALISATION AND

SEX TRAFFICKING

- A qualitative study on support to victims

of the sex trade, in an Indian regional context

PETRA SPENCER

Author: Spencer, P.Title: Social justice, globalisation and sex trafficking. Subtitle: A qualitative study on support to victims of the sex trade, in an Indian regional context. Degree

project in social work 30 credits. Malmö University: Faculty of health and

society, Department of social work, 2014.

Abstract: Karnataka has turned out to be a hotspot destination for human

trafficking. Unfortunately many migrants and others fall prey for traffickers, often due to the dark sides of globalisation. The overall purpose of the assessment was to reach a better understanding of available victim support services for victims of sex trafficking in Karnataka, and challenges thereof, as to better harmonise services and respond to the rights of victims. The method of research was of qualitative character with ethnographic elements, with fieldwork conducted in Karnataka, India. The research provides a mapping of victim support services (with a focus on shelters), while also examining challenges in relation to policy, strategy and implementation. The situation today paints out a picture of confusion in terms of a victim support system. In general, the shelters were unhygienic with poor sanitation and offered limited health services. They were also inadequate in terms of security, cooperation and coordination, as well as education and

experience among shelter staff. At the moment the ‘Protective and Rehabilitative Homes’ (Ujjawalas) are not adequate enough, and do not exclusively focus on sex trafficked victims. As such, there should be specialised assistance (with health clinics), especially since sex trafficked victims often need specialised care, psycho-socially as well as physically. A socially just system should understand and value human right, as well as recognise the dignity of every human being. If there is a lack of a functioning support system, and especially a holistic multi-sectoral approach, victims risk physical as well as mental health problems. A non-functioning system can also spur socio-economical injustices, as victims risk end up in poverty if they are not properly integrated back into society. As a cross-cutting socio-economic as well as political issue it undermines the health, security and safety of not only people directly concerned but the society in general as well.

Acknowledgement

A deep appreciation and indebtedness is expressed towards all the individuals in the shelter homes that were contacted during the research process who gave their time graciously and generously, without whom this research would not have been possible. Gratitude and acknowledgement is also expressed towards staff of NGOs and other associated locations that were visited for this documentation. I am very thankful to the Department of Women and Child Development, Karnataka, for collaborating with me on the documented projects on anti-human trafficking and victim support. I deeply appreciate the support from select experts in the field, such as the CID/ AHTU. This document attempts to capture the nature of the work that has been done regarding support to victims of sex trafficking, the needs and gaps that are experienced in the field, and a possible way forward to respond to the rights of victims.

Sincerely, Petra Spencer 2014-06-16

Acronyms:

AHTU Anti-Human Trafficking Unit

CAC Central Advisory Committee

CEDAW the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of

Discrimination against Women

CID Criminal Investigation Department

CrPC the Code of Criminal Procedure

CSE Commercial Sexual Exploitation

CSW Commercial Sexual Work

DWCD Department of Women and Child Development

GO Governmental Organisation

HT Human Trafficking

ICPS Integrated Child Protection Scheme

IGO Intergovernmental Organisation

ILO International Labour Organization

IPC Indian Penal Code

ITPA the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act

JJA Juvenile Justice Act

M&E Monitoring and Evaluation

MHA Ministry of Home Affairs

MWCD Ministry of Women and Child Development

NCW National Commission for Women

NGO Non-Governmental Organisation

NHRC National Human Rights Commission

PPP Public Private Partnership

P&R Protective and Rehabilitative

SAC State Advisory Committee

SC Scheduled Cast

SOP Standard Operating Procedure

ST Scheduled Tribe

STD Sexually Transmitted Disease

TIP Trafficking in Persons

UDHR the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

UN United Nations

UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund

UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

UNTOC United Nations Convention against Transnational

Organised Crime

UT Union Territory

3 P’s Prevention, Protection and Prosecution

3 R’s Rescue, Rehabilitation, and Reintegration

Abstract

Acknowledgement Acronyms

Table and Figures

TABLE 1. KARNATAKA SOCIO-‐ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS 18 TABLE 2. SOURCE, TRANSIT AND DESTINATION FACTORS 19

TABLE 3. LEGAL FRAMEWORK 22

TABLE 4. GOVERNMENT INITIATIVES AT A GLANCE 25 TABLE 5. KARNATAKA -‐ PROTECTION MECHANISMS AT A GLANCE 26 FIGURE 1. MASLOW'S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS 31

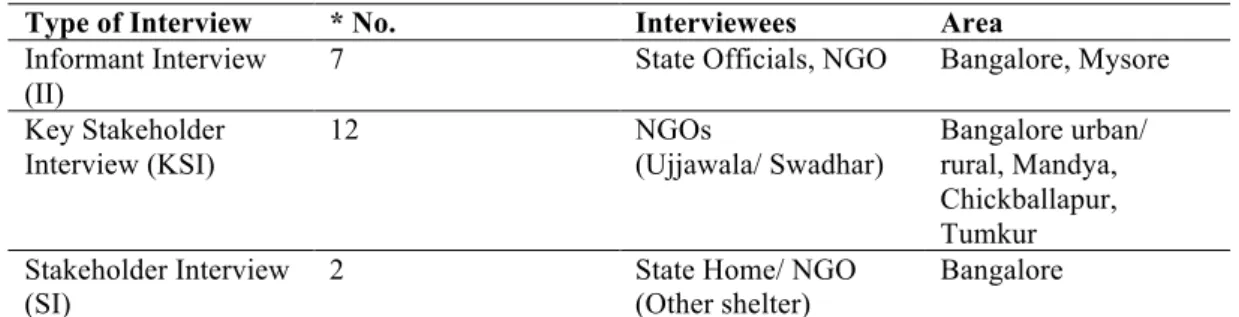

TABLE 6. INTERVIEWS CONDUCTED 35

Table of Contents

1. Intro ... 8

1.1 Background ... 8

1.2 Objective and research questions ... 10

1.3 Disposition ... 10

2. Scope of the work ... 12

2.1 Method and sources ... 12

2.2 Ethics ... 14

2.3 Relevance and (de)limitations ... 14

2.4 Research definitions ... 16

3. Previous research ... 17

3.1 Socio-‐economic characteristics ... 17

3.2 Migration patterns and sectors ... 18

3.3 Supply and demand-‐side factors ... 20

3.4 Legal framework ... 21

3.5 Institutional framework ... 23

3.6 Past and current protection efforts ... 26

4. Theoretical framework ... 28

4.1 Theoretical discussion ... 28

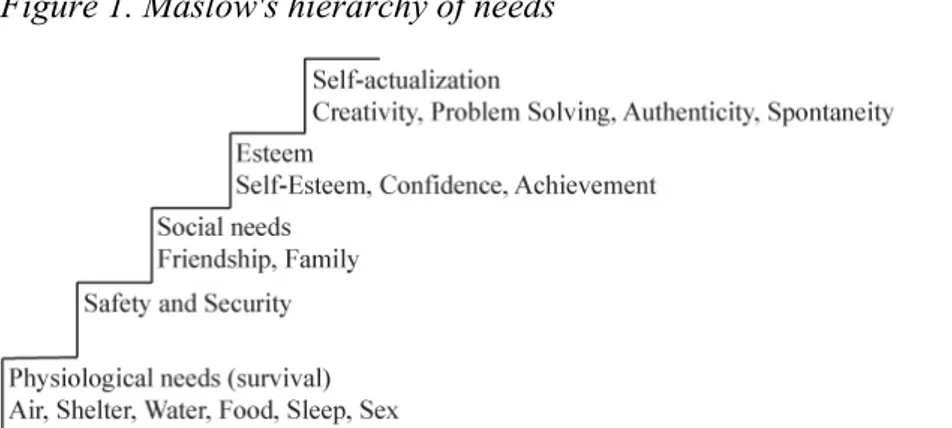

4.2 Theory/ theoretical perspectives ... 29

4.2.1 A theory of human motivation ... 29

4.2.2 Social justice ... 31

4.2.3 Social mobilisation and networking ... 33

5. Field research ... 35

5.1 Results ... 35

5.1.1 Perspectives on sex trafficking and victim support ... 35

5.1.2 Perspectives on state/ law focused questions ... 38

5.1.3 Capacity/ perspectives on coordination and cooperation ... 39

5.1.4 Intervention efforts and capacity ... 41

5.1.5 Admission policy ... 44

5.1.6 Funding and sustainability ... 45

5.1.7 Staff component and training ... 46

5.1.8 Security ... 47

5.1.9 Shelter premises and capacity ... 49

5. 2 Analysis ... 50

5.2.1 Perspectives on sex trafficking and victim support ... 50

5.2.2 Perspectives on state/ law focused questions ... 53

5.2.3 Capacity/ perspectives on coordination and cooperation ... 54

5.2.6 Funding and sustainability ... 58

5.2.7 Staff component and training ... 59

5.2.8 Security ... 60

5.2.9 Shelter premises and capacity ... 61

6. Summary and conclusion ... 62

6.1. Summary ... 62 6.2 Concluding discussion ... 62 6.2 Recommendations ... 65 References: ... 67 Appendices

Appendix 1.List of interviewees Appendix 2. Introduction guide

Appendix 3. Interview guide – stakeholders/ informants

1. INTRO

This is a research paper on available victim support services (with a focus on rehabilitative shelters) for victims of sex trafficking in Karnataka, India, and challenges thereof.Below is an introduction to the research problem.

1.1 Background

According to United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC, 2010:39), every year, thousands of men, women and children around the globe fall into the hands of traffickers. Almost every country in the world is affected by trafficking, whether as a country of origin, transit or destination for victims. As one can imagine it is difficult to estimate the size of the problem, and many countries have only recently passed, and some have yet to pass, legislation making human

trafficking a distinct crime. Definitions of the offence vary, as does the capacity to detect victims (ibid). According to one estimate, made by the International Labour Organization (ILO), 20.9 million people are victims of trafficking globally. This estimate includes victims of human trafficking for labour and sexual exploitation. According to data collected by UNODC, trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation accounts for 58 per cent of all trafficking cases detected globally (UNODC, 2012:1ff).

Principles of international human rights were established after World War II as to guarantee civil liberties and fundamental freedom for women, for example by ‘the Universal Declaration of Human Rights’ (UDHR, 1948) and ‘the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women’ (CEDAW, 1979). However, women in South Asia have remained an exception from enjoying fundamental freedom and rights. According to UNODC (2008:4), South Asia is seen as a vulnerable region for trafficking because of its huge growth in terms of population, urbanisation, and abject poverty. Research also reveals that trafficking in women and children is on the increase in Asia (ibid).

According to Brysk and Maskey (2012:42) globalisation have resulted in South Asia becoming a low-cost, labour-intensive production centre. As a result of globalisation some people have become unable to enjoy the resources of citizenship (ibid). India has been ranked as one of the highest as an exploiter of trafficking among the South Asian countries. As mentioned by U.S Department of State (2013:195ff), India is not only a source, but also a transit and destination country for trafficking.According to UNODC (2008:11) reform processes have widely transformed the economic landscape of the country over the years, however, the benefits of economic growth have not reached different parts of society in an equitable way.

Brysk and Maskey (2012:45f) argues that surprisingly little international attention has been paid to human trafficking in India, although the country represents one-sixth of the world’s population and is well-known to suffer from modern forms of slavery. One reason trafficking in India is relatively invisible is that it is mostly regional and domestic. Another reason India’s trafficking is overlooked is that India is a rapidly globalising democracy in which rising social inequality is increasing the ‘citizenship gap’ between rights in theory and in practice for many marginalised groups. Even as the public sphere in India modernises, patriarchal

traditions and gender inequity is claimed to have resulted in the feminisation of poverty, exacerbating women’s vulnerability to sexual exploitation. And, as in many developing-world democracies, in India, corruption undermines protection of women (ibid). Sex trafficking is increasing in India, as well as in the

representative state, that is Karnataka (Hameed et al. 2010:21; Kumar, 30 July, 2012). Kant (2013:9ff) claims that, despite strong steps taken by the Government of India, the trafficking rackets and gangs have become more organised and expanded into newer forms of trafficking.

It is argued by P.M Nair (one of India’s most prominent trafficking experts), that the economic boom has increased the demand for sexual services and increased the level of migrant workers, leading to a resultant increase in the supply of victims (Hameed et al. 2010:16). According to news reports (Dev, 5 Nov, 2013; Kumar, 30 July, 2012) Karnataka has turned out to be a hotspot destination for human trafficking. Kant (2013:11, 106ff) argues that the state is not only a source area for traffickers, but also a destination area for sex trafficked victims. With modernisation, sexual exploitation of women and children is claimed to have undergone a change (ibid). In Karnataka, sexually exploited victims can receive help under ‘the Ujjawala Scheme’, which seeks, for example, to protect and rehabilitate female sex trafficked victims. U.S. Department of State (2013:197) mentions that corruption has led to the closure of many homes under the Ujjawala Scheme. The lack of government oversight and monitoring of these shelters has led to much criticism, particularly as several cases of abuse have been discovered. Shelters have also been overcrowded and unhygienic, offered poor food, and provided limited, if any, services (ibid).

According to UNODC (2011:11ff), protection involves, in cooperation with non-governmental organisations (NGOs), that safe and adequate shelters meet the needs of victims, as well as ensure that victims are protected from harm or intimidation (ibid). Sekar (2011:61f) argues that holistic care is vital for

successful rehabilitation and re-integration of victims. Apart from the provision of the basic needs such as food, shelter and clothing, there are many psycho-social needs that caregivers need to address. This includes for example medical services and counselling (ibid). Nair and Sen (2007:514ff) argues that while there are efforts to prevent trafficking at the source areas, there is hardly any efforts to address the areas were children are being trafficked to. And even if there are initiatives, it is often noticed that the interventions come to a halt after the rescue operation (ibid). According to Brysk and Maskey (2012:47), research has shown that rehabilitation measures in India are not adequate and that not all rescued victims receive rehabilitative services. Those rescued and taken to shelter homes have been critical of the quality of counselling and vocational training offered. Because of inadequate rehabilitation and reintegration measures, many rescued victims are also re-trafficked (ibid).

Against the backdrop of this, Karnataka’s most disadvantaged social strata continue to fall prey for traffickers. This research seemed crucial in order to establish what services that actually are available, as well as needs and gaps, in terms of victim support. Particularly in terms of harmonising victim support services and thus respond to the rights of the victims, a response which is crucial and also guaranteed by the state. Subsequently, a response so crucial should be imbedded in the social system and institutions. In the outlooks of it, it seems as

there is a lack of recognition and assistance from the state regarding the problem, then there will not be a sufficient victim support system in place.

1.2 Objective and research questions

The objective with the research was to highlight available victim support services (in both theory and practice; i.e. examining challenges in relation to policy, strategy and implementation) for victims of sex trafficking in Karnataka, and challenges thereof. Further the study had as an aim to provide an opportunity for reflection on the conditions, obstacles and opportunities to conduct social

mobilisation in an area characterised by a complex problem. This means that there was a desire to develop a meta-theoretical perspective on qualitative grounds that can be used in relation to social work to develop a critical, reflexive and fair approach, as to better harmonise services and respond to the rights of the victims – a perspective that takes into account the individual, positions, as well as

structural factors. This research paper thus intends to present an alternative point of view and response to the problem of sex trafficking and victim support

services, such as holistic care in shelter homes.

Research Question: How is sex trafficking and victim support in Karnataka perceived and experienced (by selected stakeholders)?

Sub-question 1. What is the nature and scale of sex trafficking and a victim support system (i.e. shelters and rehabilitation) in the State of Karnataka?

Sub-question 2. What are the common challenges, needs and gaps, especially with regards to key stakeholders’ capacity?

1.3 Disposition

In chapter 2, the research paper begins with a motivation of the choice of the qualitative method of use as well as it outlines the methodological procedure that forms part of the point of departure. This includes a description of the method and sources, relevance, limits and delimitations, and an ethical discussion. Further it is defined and explained a few, for the research paper, relevant concepts.

Chapter 3 presents previous research, and also form part as secondary sources of the collected material for the research. A critical literature review seemed

essential to include as it demonstrates that the researcher knows the field of the research problem. This means more than reporting what has been read and understood, as it enables the identification of what the most important issues are and their relevance to the research and knowledge of controversies. The review of previous research allowed for mapping the field and position the research within a context. Knowledge of the field helped to identify the needs and gaps, as well as to what seemed crucial to integrate in the following field research, chapter 5 reflects this focus.

Chapter 4 outlines the theoretical framework, which includes a theoretical discussion as well as it outlines the chosen theories for the research paper. It seemed essential to, for example, establish what a theory is and why they are needed, as well as to describe how the chosen research area and research questions fits with the selected theoretical framework. As such, the theoretical framework is used as a way to anchor the paper in a scientific discussion, to use and build on previous work of earlier scholars.

Chapter 5 presents the empirical material (primary sources) for the research paper. Chapter 5.1 presents the data collected during the fieldwork undertaken in

Karnataka, with a connection to aim and research questions. Chapter 5.2 presents the analysis of the collected data. Subchapter 5.1.1 corresponds with 5.2.1, and so on. Further, there is a slight connection to previous research as well, in terms of some steering documents and theoretical contributions.

Chapter 6 presents a summary and conclusion. This concluding chapter presents a statement of the main point of view presented in the introduction in response to the topic, implications resulting from the analysis of the topic as well as

2. SCOPE OF THE WORK

In the following section the methodology is outlined, which describes method and sources, ethical considerations, relevance and (de)limitations and research

definitions.

2.1 Method and sources

Based on the scope and objective of the research, a qualitative methodological approach was adopted, with ethnographic elements – with fieldwork conducted in Karnataka, India. The choice of a more ethnographic approach seemed essential since the research problem was focused on human culture and social problems. According to Gray and Webb (2013:196), the aims and methods of social work and ethnography are parallel. As a method, ethnography investigates how people live in their natural environment and the circumstances and conditions that

ultimately shape their experiences. This requires of the ethnographer to go to were people live, participate in and/or observing daily life and open systems, similar to social work. The implementing entity was living in India during the research process, more or less on a permanent basis, and access to the field was not an issue.

As mentioned by Grey and Webb (ibid), although participation and observation over time is the cornerstone of ethnographic research, ethnographers often draw from a deep toolbox of strategies. Hence, something this research undertook as well. As mentioned by Bryman (2011:378), additional data, in ethnographic work, is often collected through the help of interviews or written sources. Further, the analysis of power was also a central issue, especially since the implementing entity sees herself as a critical thinker, and since the study emphasise on social transformation as forms of justice, equality and emancipation. The basis and interpretative perspective for this paper was of hermeneutic character. As mentioned by Bryman (2011:32) this means science that seeks an interpretative understanding of social action.

Before launching the main study, minor pilot activities was carried out. The main objective of the pilot phase was to gain an overall insight into the research

problem, and to develop the research instruments for the qualitative components of the research. In this phase an introductory explanation about the, then,

forthcoming research was sent out as a written ‘alert’ to some organisations that they would be contacted in the near future. The research was then conducted through a two-stage process. The first stage involved reviewing secondary data describing the dynamics of sex trafficking and protection efforts in India, and in the representative state in particular. The literature review of previous research was generated through systematic search in several online databases to locate peer-reviewed literature, as well as to search for grey literature. Key words, such as for example sex trafficking and shelter homes in Karnataka, guided the

literature search. A manual search of references in retrieved documents was also performed. Organisations or publishers of documents, working on sex trafficking, were also contacted. The fist stage enabled the identification of activities and interventions of governmental institutions as well as NGOs, as well as it enabled for a review of the legal framework pertaining to sex trafficking. The second stage reflects the empirical material for this research and involved interviewing people working in NGOs and governmental institutions, in order to understand the

current situation of a victim support system and challenges thereof, such as implementation hurdles, needs and gaps. This was more of a primary in-depth documentation process. The second stage also enabled to further review literature. At the conclusion of the research process a range of suggested recommendations was developed as to better harmonise victim support services and respond to the rights of the victims.

Strategies for when collecting data ranged from deskwork (literature reviews, web browsing etc.), for when conducting the initial assessment and mapping, to

fieldwork for when conducting observations and interviews (semi-structured and unstructured). Various types of interviews were used and categorised, such as key stakeholder interviews (KSI, shelter homes), stakeholder interviews (SI, shelter homes or other service providers) and informant interviews (II, government officials, academics etc.). Each KSI took approximately two hours to conduct. The interview guide was thus developed as according to the interview situation (see ‘Appendices’). Research questions in the interviews were somewhat based upon previous research and the researchers prior knowledge,3 as well as it attempted to be is in line with the selected theoretical analytical tool. The interview guide for the KSIs was designed so that it could easily be

operationalised, chapter 5 reflects this focus. Confidentiality and informed consent was taken into consideration. All interviewees gave their informed consent on going ’public’ with the information disclosed. Interviews were transcribed and stored in a secure place. However, this research did not include the views of victims, nor was it covert or secretive in nature.

The primary sources were based upon data collected from organisations such as NGOs (shelters) and governmental institutions (e.g. Women and Child

Department). Some governmental institutions and informants functioned foremost as entry points/ facilitators as to enable KSIs. Secondary sources have been based upon academic journals, articles and reports, from for example the UN, and others. The research thus attempts to shed light on victim support services, and challenges thereof, from different levels - the institutional level as well as from the grass-root level. The secondary data was also used as corroborative evidence during the field research process.As recommended by Atkinson and Hammersley (2007:183f), in order to avoid anecdotes (and errors) in secondary sources, such as by word of mouth, triangulation was used to verify information when needed. The various shelters that was visited was targeted due to their location in the representative state, such as being located in areas affected by the problem of sex trafficking, and especially for being ‘Protective and Rehabilitative Homes’ (P&R Homes/ Ujjawala homes) for sex trafficked victims. In some instances the

selection of which shelters to visit in the state was a choice against the backdrop of a convenience sample. 4 The State of Karnataka was chosen, for example, as it is a major hub with a high population density that is increasingly becoming affected by sex trafficking (see 2.3 ‘Relevance and (de)limitations’).Further, the research was undertaken during a timeframe of approximately six months which consisted of preparatory research, major research (theoretical and field based), and post-research activities as when finalising the research paper.

2.2 Ethics

Before the field research activities took off an ethical review of the intended project was approved by the Ethical Committee at Malmö University, as to make sure that the research corresponded to the ethical principles adopted by the University. 8 This approved application was also sent to the Head of the

Department in due time for the examination, as to make sure recommendations was followed. It should be noted that the Ethical Committee did not recommend interviews with victims, and thus, this can have deprived the research of some important aspects, such as victims’ perspectives on critical issues such as for example ‘victim-friendly approaches’ or staff members’ possible lack of knowledge about sex trafficking. Also, during the research process victims themselves, and staff members, encouraged interviews with victims. The various stakeholders might have perceived the lack of interviews with victims as a lack of interest from the researcher.Confidentiality and informed consent was taken into consideration throughout the entire research process. Despite the fact that the implementing entity stored information pertaining to shelters’ location in a secure place (as they are supposed to be ‘safe houses’ away from traffickers), many addresses were available online, also published by the government.

2.3 Relevance and (de)limitations

The implementing entity asserts that the research undertaken was relevant, especially since it had a focus on social vulnerability- that is victims of sex

trafficking, as well as it had a focus on social work- that is victim support services provided to victims by for example social workers. In this context, a discussion on adoptable standards of professionally designed and administered minimum

standards of care and support services become relevant. As mentioned by, for example, Brysk and Maskey (2012:42ff), surprisingly little international attention has been paid to human trafficking in India. While the bulk of the work that has been undertaken in the area of sex trafficking has focused on prevention and the nature and scale of the practice, there is a dearth of information on responding to the rights of victims in terms of holistic victim support and care, such as shelter facilities and their capacity. This study therefore attempts to provide crucial information on victim support services, and challenges thereof.

The researcher asserts that the methods used provides for a sufficient degree of reliability, in the sense that the assessment has produced stable and consistent results. It is also asserted that the research presents validity, as it has analysed what it purported to analyse. Further, data collection ended when theoretical saturation/ empirical robustness seemed to have been achieved. Transcriptions and summaries of the collected data were done regularly in order for the field research to achieve good quality. As mentioned, the choice of qualitative research, with ethnographic elements, seemed essential since the research problem was focused on human culture and social problems. While there is a risk that the respondents interviewed might not be interpreted as quantitatively significant to some readers, it nonetheless provides valuable perspectives on sex trafficking and victim support services in Karnataka. The qualitative in-depth discussions helped to identify and enable the analysis of the implementation of schemes and programmes, the impact they have had, as well as recognising that much still needs to be done. The

research can thus provide important information on needs and gaps, chapter 5 and

6 reflects this focus. Many NGOs are registered, but not all, and though this may be positive and dynamic for a democratic development it does encompass

challenges in terms of a coordinated victim response.

The research could have faced constrains and limitations on the ability to use quantitative data due to limitations resulting from the nature and scale of sex trafficking, however a quantitative approach was not desired. The nature of sex trafficking is also such that reliable quantitative data is scarce, for several reasons. Some shelter homes were hard to locate, and the Department of Women and Child Development (DWCD) did not always know whether some shelters were up running or not. Data collection was slightly challenged due to the fact that some organisations were hard to get ahold of. As always when doing research in foreign countries, and especially in rural areas, information might have been lost in

interviews were translation was necessary. It should be noted that there were some cases of language barriers, however, the information provided is nonetheless credible since interviewees in the majority of cases spoke English and the data could also be corroborated.

In addition to this, the possibility to use the interviewees’ own words, such as by using quotes, might have been affected due to the fact that a recording device was not used. The choice not to use a recording device was made by the researcher due to the fact that there were language barriers, and just taking notes thus seemed more efficient. Further, a recording device was not used since the researcher believed that this could deter people from talking. As mentioned, the research lacks the perspectives of victims, since this was not recommended by the Ethical Committee (see ‘Ethics’). Data collected in interviews might have been

compromised if interviewees perceived the researcher to be the government’s (DWCD) ‘extended arm’, however this potential problem was addressed by an attempt to install confidence in the stakeholders.

Due to the various forms of trafficking and the magnitude of the problem and, as well as due to the research’s purpose and linkage to social work, this research focused on human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation and victim support services. This research also focused on the State of Karnataka in India, as to narrow its scope. Also, since India consists of a federal system the state governments have the ultimate responsibility for implementing and launching anti-human trafficking initiatives. Nevertheless, there was a need to make a reduction in geography focus so as to allow for sufficient depth of research into the selected state, and target a state with great representative problems. Due to the magnitude and the diversity of India’s states and territories, sex trafficking differs greatly based on the characteristics of a given region. Thus, the research needed to establish delimitations in its scope. Trafficking of women and children is claimed to have increased in Karnataka, and the state is characterised as a destination location for sex trafficked victims, which was essential also in order to identify support services such as rehabilitation homes for victims. The

selection of Karnataka was thus based on the following criteria: representation as a destination location; representation of ‘protection efforts’9 (that includes

rehabilitation); an increasing trend towards sex trafficking; an environment that seemed receptive to analysis/ interventions; representation within the group of a

variety of dynamics that could potentially be influencing the rate of sex trafficking; and sufficient data available.

2.4 Research definitions

Human trafficking – according to the United Nations Convention against

Transnational Organised Crime (UNTOC) and its protocol thereto, the ‘Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons,’ trafficking in persons (TIP) is a serious crime and a grave violation of human rights. 10 According to the UNTOC and its protocol thereto, trafficking in persons, is defined as:

‘the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organ’ (The Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, article 3 (a)).

Globalisation – can be defined as the integration of economies, industries,

markets, cultures and policy making around the world. Recently the term has been expanded to include a broader range of areas and activities, such as for example climate change. In this research it becomes important to point out the ‘dark sides of globalisation’, which in this research should be understood as people exploiting other more vulnerable people, due to both groups desire of satisfying their needs, for example due to urbanisation, economic booms and people searching for employment.

Safe House - it is important to clarify the definition of a ‘safe house’ since the term can refer to two different components of what a safe house can be. A safe house can either refer to, as in this study, a secure shelter identified (however not necessarily officially accredited) by the government as a victim support service. It can also refer to a safe house in which trafficked people are taken to by their traffickers. Trafficking vs. Prostitution – sex trafficking does not mean prostitution. In understanding trafficking one should delink it from (voluntary) prostitution. According to P.M. Nair (2007) ‘demand’ in commercial sexual exploitation (CSE) is claimed to generate, promote and perpetuate sex trafficking. In India, sex

trafficking seems to be discussed in terms of prostitution mainly due to the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act (ITPA, 1956).

Victim support services - it is important to emphasise on the fact that victim support services in this research focus on service providers that can ‘protect’ sex trafficked victims in shelters that also can rehabilitate the victims, and not all stakeholders who provide assistance in areas such as prevention and prosecution.

3. PREVIOUS RESEARCH

This chapter presents previous research and hence further background information into the research problem. As mentioned, this research focused on the State of Karnataka in India, as to narrow its scope (see section 2.3 for selection criteria). In order to reach an understanding of the research problem, it seemed essential to outline socio-economic characteristics, migration patterns and sectors, supply and demand-side factors, the anti-TIP legal and institutional framework, as well as past and current protection efforts. As mentioned, some steering documents and theoretical contributions from this chapter forms part of the analysis.

3.1 Socio-economic characteristics

As mentioned in the latest census (Census of India, 2011)the population of Karnataka is rising considerably due to rapid efforts towards development and progress. In total, the state of Karnataka comprise of 30 districts. It is the 8th largest state in the country in terms of area. The total population, in 2011, was 61.1 million persons, making it the 9th most populated state in India. Kannada is the official language of the state. The main religion practiced is Hinduism. The total population growth in the state, in 2011, was 15.60 per cent. The capital city, Bangalore, had a population growth of about 47 per cent. The sex ratio was 973 females per 1000 males, which is slightly better than the national average.

Literacy rate in Karnataka has seen an upward trend and was 75.3 per cent, as per the 2011 census. Of that, male literacy stood at 82.47 per cent, while female literacy was only 66.01 per cent (ibid).

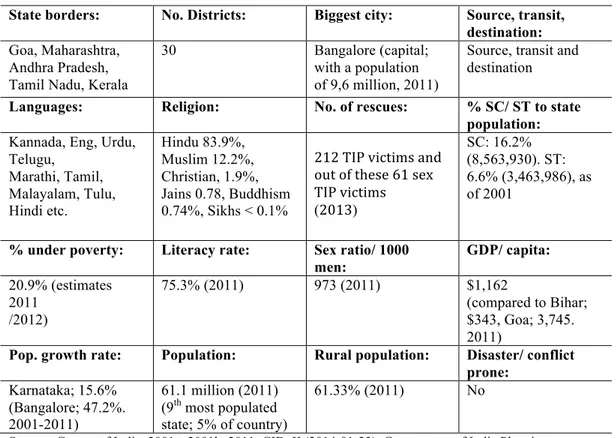

According to Nair and Sen (2007:38f, 511) Karnataka is predominantly rural and agrarian, however it is also one of the leading industrialised states. In general, people in the northern part of Karnataka are poorer, whereas the southern part of the state is populated by relatively affluent people (ibid). Karnataka is one of the high economic growth states in India, even so, the percentage of the population living below the poverty line was estimated to be 20.9 in 2011-2012 (Government of India Planning Commission, 2013). According to one source (Dev, 5 Nov, 2013) Karnataka has reported the third highest number of human trafficking cases in the country during 2009-2012. According to Nair and Sen (2007:38f, 511) complaints of exploitation of women and children have shown an increase in recent years in Bangalore. 11See table 1. below for a brief overview of Karnataka’s socio-economic characteristics.

Table 1. Karnataka socio-economic characteristics

State borders: No. Districts: Biggest city: Source, transit, destination:

Goa, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Kerala

30

Bangalore (capital; with a population of 9,6 million, 2011)

Source, transit and destination

Languages: Religion: No. of rescues: % SC/ ST to state population:

Kannada, Eng, Urdu, Telugu, Marathi, Tamil, Malayalam, Tulu, Hindi etc. Hindu 83.9%, Muslim 12.2%, Christian, 1.9%, Jains 0.78, Buddhism 0.74%, Sikhs < 0.1%

212 TIP victims and out of these 61 sex TIP victims (2013) SC: 16.2% (8,563,930). ST: 6.6% (3,463,986), as of 2001

% under poverty: Literacy rate: Sex ratio/ 1000 men: GDP/ capita: 20.9% (estimates 2011 /2012) 75.3% (2011) 973 (2011) $1,162 (compared to Bihar; $343, Goa; 3,745. 2011)

Pop. growth rate: Population: Rural population: Disaster/ conflict prone: Karnataka; 15.6% (Bangalore; 47.2%. 2001-2011) 61.1 million (2011) (9th most populated state; 5% of country) 61.33% (2011) No

Source: Census of India, 2001a, 2001b, 2011; CID, II (2014-01-23); Government of India Planning

Commission (2013), Nair and Sen (2007:38f, 511).

3.2 Migration patterns and sectors

Half of the world’s victims of human trafficking is claimed to reside in India (ADI-EL Foundation, 2013). India’s trafficking patterns indicate that 90 per cent of its trafficking is domestic. Trafficking between Indian states (i.e. inter-state) is claimed to be rising due to increased mobility, rapid urbanisation, and growth in a number of industries. A large number of Nepali and Bangladeshi females (with a majority being children) as well as an increasing number of women and girls from Uzbekistan, Ukraine, Russia, Azerbaijan, Serbia, Kazakhstan, and Afghanistan are also subjected to sex trafficking in India (U.S. Department of State, 2013:195). According to Kant (2004, 41f, 106ff) trafficking in person (for sexual

exploitation), especially amongst minors and young girls, are allegedly increasing enormously all over Karnataka. Kant (2013:11, 106) argues that Karnataka is a source and destination state for sex trafficking. Women and children are trafficked from Karnataka for sexual exploitation within the country, and also for

international trafficking to, for example, Gulf countries (ibid). Regions vary in their human trafficking migration patterns. Some states/ territories might be source areas, others being destination or transit areas, and the full gambit of possibilities in between (such as one area being e.g. both source, transit and destination). Table 2. below outlines some factors that distinguish one area from another.

Table 2. Source, transit and destination factors

Source: Poverty is often cited as the single largest reason for people ending up leaving an

area, and thus, for an area being a ‘source’ of human trafficking. Still, cultural issues (e.g. the caste system), religious issues, natural disasters or conflicts, and the lack of an effective legal framework could function as reasons as to why an area is being cited as a source location.

Transit: Reasons such as geography (e.g. transport hub to other states) and infrastructure (e.g.

extensive and unmonitored train networks) is often attributed to locations cited as ‘transit’.

Destination: Areas economic success is often cited as a derivate of high inflows of migrants

from the rest of the country. A high demand for sex workers as a result of being a major tourist destination, generic gender/ caste issues, and lack of community responsibility for social security and welfare are other reasons cited. The absence of a strong legal framework is another factor.

Source: Hameed et al. 2010:11.

Southern states, such as Karnataka, have historically functioned as the supply areas to destinations such as Mumbai, Goa, Kolkata and Chennai (U.S. Department of State, 2003). Nair and Sen (2007: 503ff) argue that in recent years Karnataka has become a destination area for trafficked victims. According to Kant (2004, 41f)

districts in Karnataka such as Mysore, Bangalore, Raichur, Ananthapur, Raichur, Gulbarga, Bijapur, Bellary, Shimoga, Haveri, Meruj, Coorg, Mandya, Tumkur, Hassan and Chamarajanagar is reported to have been the areas most affected by trafficking of women and children. As mentioned by Nair and Sen (2007:48, 503ff) the various factors pertaining to why Karnataka consist of being both an source, transit and destination area can be explained for example by the fact that the state (especially the northern parts) are affected by poverty, minority groups and women (often dalits) are discriminated, the state has cross-borders and relatively good infrastructure, thus making it a good transit route. Also, due to globalisation and growth it is a popular state for migrates, who often end up as victims in the hands of unscrupulous traffickers (ibid).

Sex trafficking establishments continue to move from more traditional locations, such as brothels in densely populated urban areas, to locations that are harder to find, such as to residential areas in cities and to rural areas (U.S. Department of State, 2013:195).Kant (2013: 11, 106) claims that due to modernisation, the business with CSE in Bangalore have gone hi-tech. In Bangalore and the urban metropolitan areas of Karnataka, the business with sexual exploitation has

expanded and many of these rackets are being run from residential colonies in the name of spas, massage parlours and friendship clubs (ibid). Although the majority of sex trafficking is to supply girls for brothels and escort agencies, trafficking is also taking place for the pornographic industry (including live feeds for the Internet, ADI-EL Foundation, 2013). According to DWCD’s ‘Action Plan to Combat Trafficking of Women and Children in Karnataka’ (n.d.) CSE of women and children takes place in various forms, including sex tourism. Sexual

exploitation practised under ‘the Devadasi system’ (see below) is also being recognised as one form of trafficking (ibid). According to Sathyanarayana and Babu (2012:157ff) the Devadasi system is an old practice of sex slavery, and Dalit girls are the ones that are the most exploited. The beginning of the practice has been traced back to Karnataka. Young girls are forced to provide sexual services to temple patrons, priests, and upper caste community members (ibid).According to Torri (2009:37ff) the system is prevalent in north Karnataka, and districts

bordering Karnataka and Maharasshtra, known as the ‘Devadasi belt’, have trafficking structures operating at various levels (ibid).

Kant (2004:41f) argues that about 80 per cent of prostitutes (often involuntary prostitution) in Mumbai and Goa originate from Karnataka. Karnataka with the adjacent state of Goa has been ranked as a popular destination for child sex tourism (DWCD, n.d). Bangalore is claimed to be one of five major cities that accounts for 80 per cent of children involved in CSE in the country (ibid).

According to Joffres et al. (2008:3f), in Karnataka, sex tourism has notably been undertaken in some of the new tourist spots like Gokarna and Karwar. Cities such as Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Hyderabad and Chennai, as well as Bangalore (in Karnataka), are claimed to have the largest concentrations of women and girls involved in CSE (ibid). The trafficking is also taking place for purposes like using the wombs and for illegal and forced marriages (ADI-EL Foundation, 2013). 12

3.3 Supply and demand-side factors

According to the Census of India (2011), the population of Karnataka has increased considerably due to rapid efforts towards development and progress. Bangalore has grown into a hub for many major companies, and many youngsters have flocked to Bangalore in recent times in search of employment (ibid). As mentioned, Karnataka has in recent years turned out to be a hotspot destination for both migrates and traffickers. Kant (2004:41f) argues that the consumerist culture, spawned by globalisation and liberalisation, lure young women into the market with sexual exploitation (ibid). In the last decade, the process of globalisation has enhanced the ‘push and pull’ factors that drive migrants’ desires to seek more gainful employments. This is claimed to have caused an unprecedented amount of migration. Migration itself does not lead to trafficking, but trafficking often happens in the process of migration (UNODC, 2008:25).

Hamed et al (2010:12ff) argues that the international promotion of the child sex industry on the Internet is another contributing factor to trafficking. He also argues that poor economic conditions, poor literacy levels, lack of awareness of the ‘outer world’, lack of education, dysfunctional families, children separated from their parents, peer pressure, consumerism and materialism, migration and unemployment all constitute the influencing factors to trafficking. The demand factors, which perpetuate trafficking in sex tourism, include perceptions of

masculinity, gender, power and myths on sexuality. It is argued that the economic boom has increased the demand for sexual services and increased the level of migrant workers, leading to a resultant increase in the supply of victims (ibid). According to Nair and Sen (2007:514ff), although tourism is not directly responsible for trafficking, it does provide an environment for easy access to vulnerable people, and especially vulnerable children. By adding pressure on the available resources and alienating people from their traditional livelihoods, the tourism industry is instrumental in facilitating an artificial development that leaves the local community vulnerable to traffickers (ibid).

As mentioned by Nair and Sen (2007:505) trafficking takes place from different socio-economic milieu, including areas not affected by poverty. It is more a question of vulnerability of the victims and the access of the traffickers. Another dimension can be the absence of law enforcement and effective surveillance

12 According to Hameed et al. (2010:13f) forced marriages, often with promises from traffickers

without a ‘dowry’ (remuneration from wife’s family to husband’s upon wedding), arise partly because of skewed sex ratios (ibid).

systems, which should include the community as a whole (ibid). As mentioned by Hamed et al. (ibid:13) trafficking is made worse by traditions that reinforce

gender discrimination based on caste and ethnicity, the Devadasi system being the most visible. Caste discrimination is outlawed, however, the caste system is not (ADI-EL Foundation, 2013). The government has tried to help former devadasis by assigning money to whoever marries a former devadasi, however this often seem to have encouraged unscrupulous people to marry these women who later trade them to brothels (ibid). Joffres et al. (2008:3) argue that after a few years of concubinage the girls are sold or auctioned to traffickers for CSE.

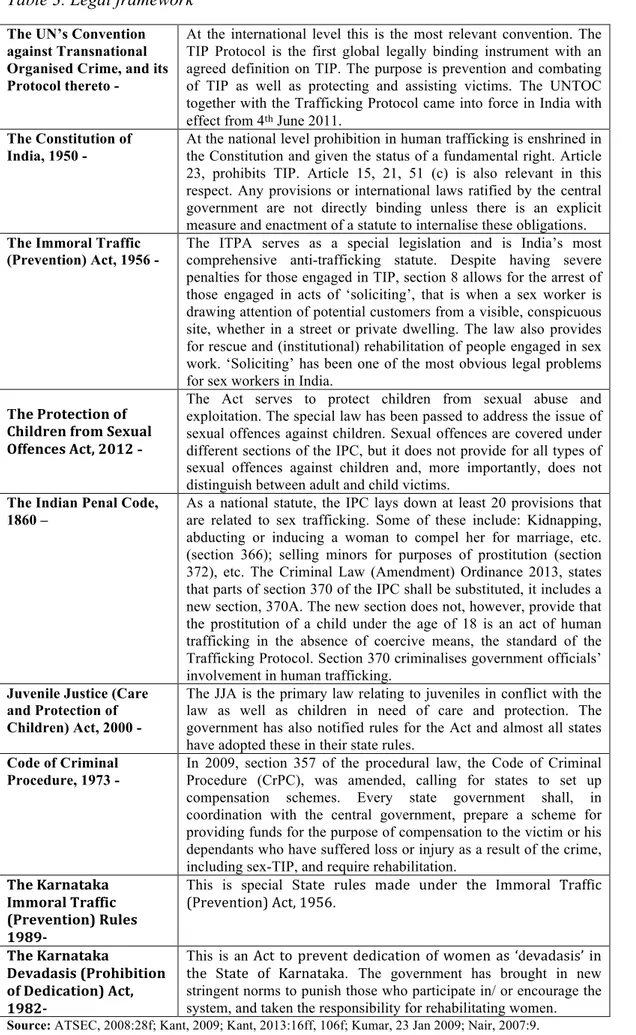

3.4 Legal framework

In recent years the government has taken significant steps to address the issue of trafficking, some of these recent steps are reviewed below. The government is committed to fulfill its obligations under various international, regional and national instruments with regard to rescue, rehabilitation and reintegration of the victims. While there is a large collection of existing conventions and statutes only the most relevant is outlined, as in table 3. Some of most relevant conventions and statutes, in relation to the subject matter, seem to be UNTOC, the Constitution of India, the ITPA, the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, the Indian Penal Code (IPC), and Karnataka Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Rules.

The Government of India is also a signatory to the CEDAW, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and its optional Protocols, the SAARC Convention on Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Women and Children for

Prostitution, among others (Kant, 2013:25). In addition, a new ‘anti-rape law’

came into affect in 2013 (TOI, 3 April, 2013). The law should be able to function as a compliment to curb sex trafficking offences. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act (1989), provides an additional tool as to safeguard women and girls from marginalised groups from being trafficked.

Despite the fact that India has a defined legal process that is supposed to deal with offenders and assist victims the legal framework is plagued with several

weaknesses. According to Hameed et al. (2010:18ff), flaws include corruption, an overburdened law enforcement sector and poorly resourced protection services. Still, they point out, there have been efforts as to rectify these flaws. Another compromising factor in this matter is the fact that trafficking is captured by over 15 various statutes, which increases confusion within an already overburden law enforcement sector (ibid).

In addition to this, in 2005, the Director General of Police of Karnataka also issued a circular (‘no Section 8 arrests’) for a victim centric approach in dealing with cases under the ITPA. The circular stated to the police that the Act was not being implemented in its true spirit and that police action should be against the traffickers, pimps, brothel keepers and those living on the earning of prostitution, and not against the women who are victims of sex trafficking (Kant, 2013:107f; Karnataka Police, DGP Office Circular No.17/CRM/SMS-4/2005).

Table 3. Legal framework

The UN’s Convention against Transnational Organised Crime, and its Protocol thereto -

At the international level this is the most relevant convention. The TIP Protocol is the first global legally binding instrument with an agreed definition on TIP. The purpose is prevention and combating of TIP as well as protecting and assisting victims. The UNTOC together with the Trafficking Protocol came into force in India with effect from 4th June 2011.

The Constitution of India, 1950 -

At the national level prohibition in human trafficking is enshrined in the Constitution and given the status of a fundamental right. Article 23, prohibits TIP. Article 15, 21, 51 (c) is also relevant in this respect. Any provisions or international laws ratified by the central government are not directly binding unless there is an explicit measure and enactment of a statute to internalise these obligations.

The Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956 -

The ITPA serves as a special legislation and is India’s most comprehensive anti-trafficking statute. Despite having severe penalties for those engaged in TIP, section 8 allows for the arrest of those engaged in acts of ‘soliciting’, that is when a sex worker is drawing attention of potential customers from a visible, conspicuous site, whether in a street or private dwelling. The law also provides for rescue and (institutional) rehabilitation of people engaged in sex work. ‘Soliciting’ has been one of the most obvious legal problems for sex workers in India.

The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 -

The Act serves to protect children from sexual abuse and exploitation. The special law has been passed to address the issue of sexual offences against children. Sexual offences are covered under different sections of the IPC, but it does not provide for all types of sexual offences against children and, more importantly, does not distinguish between adult and child victims.

The Indian Penal Code, 1860 –

As a national statute, the IPC lays down at least 20 provisions that are related to sex trafficking. Some of these include: Kidnapping, abducting or inducing a woman to compel her for marriage, etc. (section 366); selling minors for purposes of prostitution (section 372), etc. The Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance 2013, states that parts of section 370 of the IPC shall be substituted, it includes a new section, 370A. The new section does not, however, provide that the prostitution of a child under the age of 18 is an act of human trafficking in the absence of coercive means, the standard of the Trafficking Protocol. Section 370 criminalises government officials’ involvement in human trafficking.

Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000 -

The JJA is the primary law relating to juveniles in conflict with the law as well as children in need of care and protection. The government has also notified rules for the Act and almost all states have adopted these in their state rules.

Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 -

In 2009, section 357 of the procedural law, the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), was amended, calling for states to set up compensation schemes. Every state government shall, in coordination with the central government, prepare a scheme for providing funds for the purpose of compensation to the victim or his dependants who have suffered loss or injury as a result of the crime, including sex-TIP, and require rehabilitation.

The Karnataka Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Rules 1989-‐

This is special State rules made under the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956.

The Karnataka

Devadasis (Prohibition of Dedication) Act, 1982-‐

This is an Act to prevent dedication of women as ‘devadasis’ in the State of Karnataka. The government has brought in new stringent norms to punish those who participate in/ or encourage the system, and taken the responsibility for rehabilitating women.

3.5 Institutional framework

The Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) is the nodal ministry that deals with the subject of prevention and protection of trafficking in women and children for CSE. They work very closely with other ministries, for example the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA). The ministry is responsible for the

implementation of legislation pertaining to the care and protection of women and children, for example the ITPA, the JJA, and Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act. The ministry holds regular Central Advisory Committee (CAC) meetings to review the various issues in countering human trafficking. The committee has members from central ministries and state governments as well as other important stakeholders (Kant, 2013:32ff). State Advisory Committees (SACs) are supposed to monitor that initiatives are being undertaken on

prevention, rescue, rehabilitation, reintegration and repatriation in their respective states. Women and Child Department Secretaries, in all states, have been

requested to hold regular meetings of such a committee (ibid:17).

DWCD in Karnataka has formulated an Action Plan with the involvement of other relevant departments such as the Police, Education and Labour, NGOs and other important stakeholders. In order to tackle the menace of human trafficking the state government initiated an anti-trafficking cell, and an anti-human trafficking unit (AHTU), in the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) headquarters. (Kant, 2013:107f; UNODC, 2007:6ff). The units are supposed to provide a multi-disciplinary and joint responsibility approach by all stakeholders, such as the police, prosecutors, NGOs, civil society and the media. Police officials in the units are, for example, supposed to maintain constant liaison with NGOs working on anti-human trafficking (UNODC, ibid:6ff). Their mandate includes to ensure that DWCD provides all relief to rescued victims without delay, such as for travel, clothing, medicine and other immediate necessities. NGOs can, for example, assist the units in providing medical care and help (ibid).In 2013, it was reported that institutionalisation of procedures involving rescue, rehabilitation,

reintegration and repatriation issues still needed to be finalised (Kant, 2013:107f). According to Kant (ibid:35) the care and protection of a trafficked victim

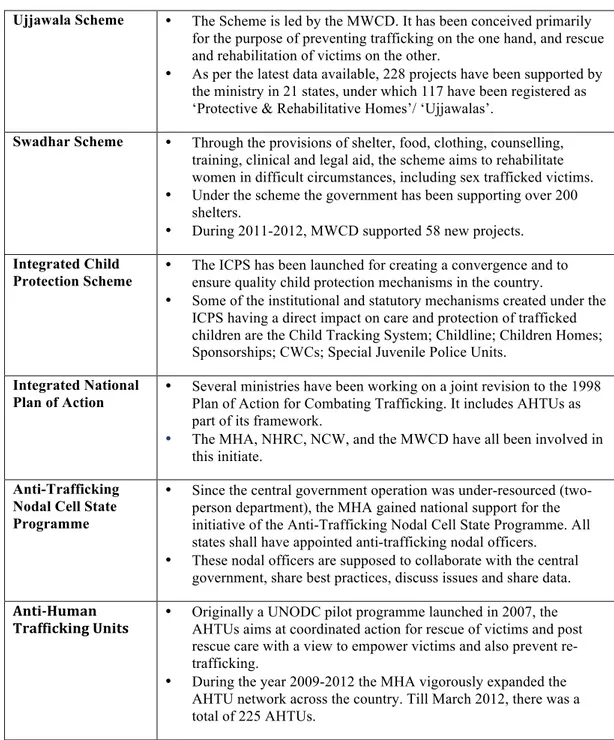

encompasses immediate care and protection, long term rehabilitation, repatriation and reintegration. Legislation like the JJA and the ITPA mandates MWCD to create such institutional mechanisms and formulate programmes and schemes for the welfare of women and children who are in need of care and protection (ibid). Some of the various initiatives of the ministry that have a direct impact on the care and protection of victims of sex trafficking are as follows:

A. The Ujjawala Scheme B. The Swadhar Scheme

C. The Integrated Child Protection Scheme

A. The Ujjawala Scheme is ‘a comprehensive scheme for prevention of trafficking and rescue, rehabilitation and re-integration of victims of trafficking and

commercial sexual exploitation’. The scheme was launched in 2007 and

conceived primarily for the purpose of preventing trafficking on the one hand and rescue and rehabilitation of victims on the other. The beneficiaries of the Ujjawala scheme are women and children who are either vulnerable to/ or victims of

concerned state governments/UT administrations. The state governments is to ensure that the organisations have capabilities and credentials in undertaking activities. The continuation of grants is to be based on the satisfactory

performance reported by the state governments. In addition, it is proposed, for example, that periodic inspections takes place at the local state level. A

monitoring mechanism is under formulation, and inter alia, the states have been requested to involve district level officers for regular monitoring (Government of India, notes, 2007; Kant, 2013:35).

B. The Swadhar Scheme was launched by the ministry in 2001-2002. Through the provisions of shelter, food, clothing, counselling, training, clinical and legal aid, the scheme aims to rehabilitate women in difficult circumstances. Swadhar is inherently a shelter based scheme and cannot holistically address the issue of rescue, rehabilitation and reintegration of sex trafficked victims. The detailed reasons for this are the fact that the background of a trafficked victim cannot be compared to that of a women/girl who is a victim of domestic violence/ rape/ destitute etc., who typically enters a Swadhar home. Keeping the above issues and gaps in mind MWCD initiated the Ujjawala Scheme (Government of India, notes, 2007). The ministry is taking steps to bring in a monitoring mechanism.

Trafficked women/girls can be attended to under the scheme. However such women/ girls should first seek assistance under the Ujjawala Scheme. The

ministry is taking steps to bring in a monitoring mechanism for the shelter homes. Women above 18 years can be attended to under the scheme. Girls up to the age of 18 and boys up to the age of 12 years would be allowed to stay with their mothers in Swadhar shelters (Kant, 2013:18ff).

C. The ‘Integrated Child Protection Scheme’ (ICPS) was launched by the government in 2009 in order to create a convergence and to ensure quality child protection mechanisms in the country. The scheme is to implement the provisions of the JJA. The ICPS objectives in brief is to contribute to the improvements in the well being of children in difficult circumstances, to reduce vulnerabilities to situations and actions that lead to abuse, neglect, exploitation, abandonment and separation of children. The scheme, being centrally sponsored, is being

implemented mainly through the state governments/UT administrations. They are then, in turn, implementing various components of the scheme either by

themselves or through NGOs. In cases of trafficked children, this scheme provides for the response mechanism for the care and protection of the child. 17 Some of the

institutional and statutory mechanisms created under the ICPS having a direct impact on care and protection of trafficked children are for example the Children Homes and Child Welfare Committees (CWCs). The CWC are the core central mechanism for care and protection of children across the country (Kant, 2013:37). Table 4. provides an overview of the most important actions, programmes and schemes relevant to the subject matter.

17 MWCD has formulated a Protocol for pre-rescue, rescue and post-rescue operations of child

victims of sexual exploitation. MWCD has also developed, for example, the ‘Counselling Services for Child Survivors of Trafficking’ (Kant, 2013: 34).

Table 4. Government initiatives at a glance

Ujjawala Scheme • The Scheme is led by the MWCD. It has been conceived primarily for the purpose of preventing trafficking on the one hand, and rescue and rehabilitation of victims on the other.

• As per the latest data available, 228 projects have been supported by the ministry in 21 states, under which 117 have been registered as ‘Protective & Rehabilitative Homes’/ ‘Ujjawalas’.

Swadhar Scheme • Through the provisions of shelter, food, clothing, counselling, training, clinical and legal aid, the scheme aims to rehabilitate women in difficult circumstances, including sex trafficked victims. • Under the scheme the government has been supporting over 200

shelters.

• During 2011-2012, MWCD supported 58 new projects.

Integrated Child

Protection Scheme • The ICPS has been launched for creating a convergence and to ensure quality child protection mechanisms in the country. • Some of the institutional and statutory mechanisms created under the

ICPS having a direct impact on care and protection of trafficked children are the Child Tracking System; Childline; Children Homes; Sponsorships; CWCs; Special Juvenile Police Units.

Integrated National

Plan of Action • Several ministries have been working on a joint revision to the 1998 Plan of Action for Combating Trafficking. It includes AHTUs as part of its framework.

• The MHA, NHRC, NCW, and the MWCD have all been involved in

this initiate.

Anti-Trafficking Nodal Cell State Programme

• Since the central government operation was under-resourced (two-person department), the MHA gained national support for the initiative of the Anti-Trafficking Nodal Cell State Programme. All states shall have appointed anti-trafficking nodal officers. • These nodal officers are supposed to collaborate with the central

government, share best practices, discuss issues and share data.

Anti-‐Human

Trafficking Units • Originally a UNODC pilot programme launched in 2007, the AHTUs aims at coordinated action for rescue of victims and post rescue care with a view to empower victims and also prevent re-trafficking.

• During the year 2009-2012 the MHA vigorously expanded the AHTU network across the country. Till March 2012, there was a total of 225 AHTUs.

Source: Hameed et al. 2010; Kant, 2013:29ff; UNODC, 2007; U.S. Department of State, 2012; 2013.

According to a report prepared for UNODC, a SAC on anti-trafficking was constituted in 2004 in Karnataka. However, according to DWCD (and CID) such a committee has not been formed at the state level, only at district and village levels (Government of Karnataka, 2007, Proceedings of Government of

Karnataka; Kant, 2013:107). Karnataka government has initiated the Ujjawala and Swadhar Schemes. 34 Swadhar homes and 33 Ujjawala shelters have been

established. 18 The Bhagya Laxmi Scheme has also been initiated, which seeks to change the attitudes of the society towards the birth of girl children and raise the status of girls socio-economically. A scheme titled Santwana (women helpline)