CULTURE-LANGUAGES-MEDIA

Independent Project with Specialization in English

Studies and Education

15 Credits, First Cycle

Why work with children’s literature in an

ESL-classroom?

Varför arbeta med barnlitteratur på engelska i klassrummet för engelska som

andraspråk?

Lucas Brandt

Master of Arts in Primary Education: School Years 4-6, 240 credits or Pre-School and School Years 1-3, 240 credits English Studies and Education

2020-10-21

Examiner: Björn Sundmark Supervisor: Sirkka Ivakko

2

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to find out why children’s literature could be used in an ESL-classroom. We know that children’s literature should be included in an ESL-classroom, according to the national curriculum for English in Sweden, but experience tells me that actual usage of children’s literature in the teaching of the English language for students in the early school years is limited. To find out why children’s literature could be used to teach I have taken part of current studies about and around the subject. The studies were found using either ERC or ERICs search engines. Furthermore, the studies used in this paper are compared to one another to see possible similar outcomes. The studies show that ESL-students show a variety of development in skills such as reading, writing, comprehension by working with children’s literature. The results also show a potential increase in motivation to learn the language.

3

Table of contents

1. Introduction ... 4 3. Method ... 7 4. Results ... 11 5. Discussion ... 14 5.1 Motivation ... 14 5.2 Learning goals ... 15 6. Conclusion ... 18 7. References ... 204

1. Introduction

Most of us remember being read storybook classics like little Red Riding Hood or Hansel and Gretel’s adventures in the woods in preschool, kindergarten or at home. Those stories taught us to appreciate close friends and family and to make us aware that our actions matter to other people, for both good and bad. What some of us fail to remember is that those stories were the first few steppingstones into learning a new language, words and sentences which may be new to you get explained and, on that road, you learn the language in a context. Neuman & Kaefer (2018) explain in a report that a lack of interest and attention in early preschool and kindergarten years may result in not completely understanding the meaning of some words, that they often are used in different context and may be used in different ways. Neuman & Kaefer (2018) furthermore explain that those years are vital to acquire necessary knowledge about the words in a language to continue their language education. Why should this be any different in learning a second language? My experiences during both VFU-courses and my personal education have shown that the dominant way of teaching the English language is through various textbooks and workbooks. However, in other subjects, e.g Swedish, I have seen and experienced different ways of including children’s literature in their education. “Book of the week” and “personal books” is terms used by teachers I have encountered in one way or another whilst being in Swedish

classrooms. Why shouldn’t I use children’s literature in order to teach the English language in the future as a teacher in my classroom?

Roslina (2017) reports in her research in a classroom in Kolaka, Indonesia, that while knowing that English as a foreign language is an important subject, it is hard and stressful to learn, especially amongst students whose motivation is low. Roslina used picture story books in an attempt to enhance the students reading skills and motivation. The result showed a similar result as a research done in the US by Louie and Sierschynski (2015), where they used wordless picture books as a source for discussion. The results showed that working with children’s literature improve the motivation and enjoyment to learn the English language amongst ESL-students. However, Rosalina’s research resulted in showing an enhanced ability to read and their will to explore the foreign language further after working with

5

children’s literature, whereas Louie and Sierschynski’s research showed that students who work with wordless picture books through discussion provides the students an opportunity to develop a deeper understanding of language of literacy elements as well as their structure.

The Swedish curriculum for English, grades 4-6, states that different texts and stories from different medias should be included in the education, also to search and choose different texts in English from different medias. The earlier years include clearly spoken English and texts from different media, different songs, and stories, as well as different forms of simple conversations. The curriculum does not, however, state how and when to integrate

children’s literature as a form of text. English is a global language that is of most importance of professional success in any profession (Nardie, 2017). The point of this paper is to find research that clarifies the relevance of teaching the English language to ELS-students through children’s literature.

Students who learn English as a foreign or second language both stumble across the same types of obstacles in learning the English language, and the importance to introduce

children’s literature in their education is regarded as equal to this paper, thus both ESL, EFL and L2 students are treated in the same way. ESL, EFL and L2 are argued in this paper as students who does not speak English by mother tongue but are in a process of learning the language through school. EL however, is a term used for students who is trying to develop their native language, in this case English.

Children’s literature is used in this paper as the material the studies which are of importance to this paper used. Neuman & Kaefers (2018) study include a read aloud book which was read in front of various classrooms, Birketveit & Rimmeride (2017) investigated what effect authentic picture books may have to students in grades 4-6 in Norway. Roslina (2017) used picture books in her study to see whether that would motivate the children to learn the English language. Read aloud book, authentic picture books and picture books are examples of what Children’s literature means to this paper.

6

2. Aim and Research Questions

Teaching and motivating students to learn English in grades 4-6 is a challenging task as a teacher. In order to motivate students to learn the language Schools and teachers use different methods, this papers aim is to find out why you should use children’s literature in an English learning classroom. Children’s literature could be included in students’ education in different ways to reach different results. Additionally, another aim of this paper is to find out why and how you should work with children’s literature in order to reach the learning goals stated in the curriculum.

The specific research question are as follows:

7

3. Method

The studies used in my research was found using either ERC or ERIC, databases which are both accessible online via the MAU-network. I narrowed my initial question in order to find relevant studies. My initial question was “how good of a method is reading children’s literature for vocabulary learning?” The question boiled down to “why use children’s literature in a ESL-classroom” after having taken part of current studies. The studies of my research were all peer-reviewed and published between 2013-2020. Total studies used for this research is 5 empirical and 6 supporting studies.

The search words “Child books” and “Vocabulary” gave me a total of 211 hits in ERC, amongst them Neuman and Kaefers (2018) study. Similarly, the search words “Children’s literature OR Children’s books” and “ESL OR English as second language” gave me a total of 72 hits in ERC, among them Louie and Sierschynskis (2015) study.

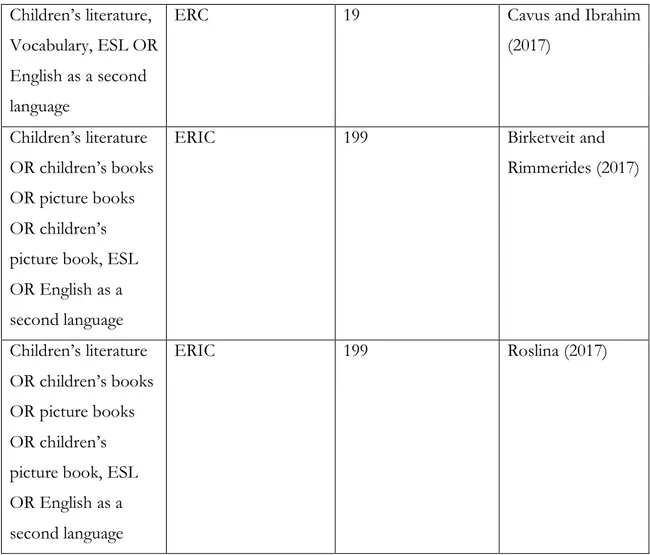

The search words “Children’s literature and “Vocabulary” and “ESL OR English as a second language” gave me a total of 19 hits in ERC, among them Cavus and Ibrahim’s (2017) study. Furthermore, I searched for “Children’s literature OR children’s books OR Picture books OR children’s Picture books” and “ESL OR English as a second language” in ERIC, which gave me 199 hits, among them I selected Birketveit and Rimmerides (2017) study. With the same search words, I also found Roslina’s (2017) study.

Table 3

Search words Search engine Hits Result

Child books, Vocabulary

ERC 211 Neuman and

Kaefer (2018) Children’s literature

OR children’s books, ESL OR English as second language

ERC 72 Louie and

Sierschynski (2015)

8 Children’s literature,

Vocabulary, ESL OR English as a second language

ERC 19 Cavus and Ibrahim

(2017)

Children’s literature OR children’s books OR picture books OR children’s picture book, ESL OR English as a second language

ERIC 199 Birketveit and

Rimmerides (2017)

Children’s literature OR children’s books OR picture books OR children’s picture book, ESL OR English as a second language

ERIC 199 Roslina (2017)

Table 4 shows what search words I decided to include and which words I have excluded. “Children’s literature” is a concept I use for picture books, children’s books, wordless picture books, I use “children’s literature” as a broad term. “Picture books” is literature with both text and pictures in them, “wordless picture books” are literature with only pictures and no text. However, I did not include informational books, which would be textbooks and workbooks, or children’s own written literature in my research.

Furthermore, in my research I include ESL, EFL, second language and L2 students, I have only included those studies based on students who attend to middle-school and below or is below 12 years of age. I decided to include EL students, because they have the same challenges as any other EFL-student, but in a different arena. This means that I have excluded studies based in Universities, college, and even upper middleschool in this paper.

9

In my search I have included teaching and learning English but focused on research that are conducted at schools, therefore excluded homestudies and otherwise parent-teaching at home.

Table 4

Inclusion Exclusion

Children’s literature Picture books

wordless picture books Children’s books Digital books

Books aimed at grown-ups Informational books (textbooks/workbooks)

Children’s own written literature

ESL-classroom EFL-classroom Second language L2 students EL

Middle-school students and below

University

Upper middle school College

Teaching English in school Learning English

At home studies Homestudies

Table 4 shows what search words I decided to include and which words I have excluded. “Children’s literature” is a concept I use for picture books, children’s books, wordless picture books, I use “children’s literature” as a broad term. “Picture books” is literature with both text and pictures in them, “wordless picture books” are literature with only pictures and no text. However, I did not include informational books, which would be textbooks and workbooks, or children’s own written literature in my research.

Furthermore, in my research I include ESL, EFL, second language and L2 students, I have only included those studies based on students who attend to middle-school and below or is below 12 years of age. I decided to include EL students, because they have the same challenges as any other EFL-student, but in a different arena. This means that I have excluded studies based in Universities, college, and even upper middle school in this paper.

10

In my search I have included teaching and learning English but focused on research that are conducted at schools, therefore excluded homestudies and otherwise parent-teaching at home.

In the next section I will summarize findings of current research on the use of children’s literature in the ESL-classroom.

11

4. Results

Knowledge of English in our digitalized world is necessary for everybody, the digital world has enabled us to break barriers between countries which makes it possible to anyone to make an international career. Canvus & Ibrahim (2017) reports that the English language is already a language that that is of most importance in order to make a professional career within any profession. Roslina (2017) states the idea that without a common language you are going to have a hard time to convey ideas, opinions, and feelings between another, which are all vital skills in order to enable yourself to make a professional career. According to the Swedish curriculum for English, Roslina (2017), Canvus & Ibrahim(2017), Birketveit & Rimmeride (2017), Louie & Sierschynski (2015) and Neuman & Kaefer (2018) it is known that children’s literature can help EFL-students to explore and improve different areas of the English language whilst working with it in different ways. The findings show that children’s literature can and should be used for different purposes. Reading, listening, writing,

speaking, grammar as well as a rise in motivation are possible outcomes by working with children’s literature in an EFL-classroom.

Neuman & Kaefer (2018) studied twelve schools in metropolitan arenas in America over the course of one year, note that within the schools there is a mix of EFL-students and native English-speaking students. The study shows that many students in those areas lack motivation in earlier years of their education. Neuman & Kaefer investigates whether low-income children can improve their oral language vocabulary through a shared read-aloud book reading program. The researchers had the teachers of the selected classrooms read a series of books which had progressively higher density of vocabulary. The goals presented to the teachers were at the end of the project to have taught the students to be able to use 230 new words. Their results show that the native speaking students that participated had some improvement of their vocabulary. However, EFL-students within the same classrooms surpassed the oral improvements some native speaking students had and were able to engage in different discussions in a more complex way.

Cavus & Ibrahim (2017) conducted a study in Cyprus on 37 students who are 12 years of age. The researchers investigated the possibility to integrate mobile devices in classrooms to

12

encourage improvement of learning skills such as vocabulary, pronunciation, listening and comprehension through children’s stories. The project was implemented during a period of 4 weeks, where the students were prompted to spend 1.5 hours in front of the application where the children’s stories were displayed. Their data is collected through a pre-test before the project were set in action, which were compared to another test made at a later date. The study shows that work with children´s stories improved the children’s´ language skills such as vocabulary, pronunciation, listening and comprehension, because they were more motivated when they used their mobile devices in the project.

Roslina (2017) studied 15 students who attends a school in Medaso Kolaka, Indonesia. The participants are perceived to lack motivation to learn the English language, due to infrequent tutors that mostly have non-formal education to be teachers. This study puts most focus on how the application of picture story books improve the students reading skills, with one control group reading children’s literature without pictures and the other group with pictures. Roslina’s conclusions are based on gathered data through questionnaires, reading tests, observation sheets and interviews. The conclusions of her study show that children’s literature with pictures help stimulate students’ motivation, imagination as well as creativity, which is seen as a contributing factor to help grow student’s confidence and autonomy to continue learn the English language. Her results also show that those students who were treated with pictures ended up being more active because they were encouraged by the pictures to know the meaning of the text.

Birketveit & Rimmeride (2017) investigated what effect authentic picture books could have on 11-year-old Norwegian EFL students’ motivation and writing skills. In this study, Birketveit & Rimmeride let 21 students pick 3 books from a list of 70 authentic picture books they were to read within a time span of 4 weeks. Through logbooks, a questionnaire, interviews and students’ written texts before and after the reading project the researchers could come to the conclusion that being able to choose what material you were going to process in your education rose their interest and therefore also motivation to learn.

Additionally, some of the students was under the impression that they would not be able to complete the task, which due to them being motivated had an easier time completing than the students expected. Lastly, the study shows that the student’s ability to formulate adverbs

13

were increased. However, in order to be able to use a varied selection of adjectives whilst writing themselves, they would need to be taught in a different environment.

Louie & Sierschynski (2015) investigated if it is possible to develop reading habits, stimulate oral language and facilitate literacy development using wordless picture books. In their study they went to an American school but laid focus on ELs, in this particular study They

followed two ELs who were quite new to the language. The two students looked at the wordless picture books together with a teacher and discussed the content together. The conclusion of the project is that through discussion of the content provided with other ELs and the teacher, the students are able to develop a deeper understanding of vocabulary, both written and oral. Therefore, as a biproduct increases their enjoyment towards the English language.

14

5. Discussion

The studies used in this paper are in a consensus that children’s literature can and, in some cases should be used in English education. However, their research points in slightly different directions.

Roslina (2017) suggests that learning English as a second language is a stressing activity, because we know just how important the language is. Roslina argues that many people have recognized that English is becoming a global language and is quickly becoming to be a necessary skill to have to match the global need. Cavus & Imbrahim (2017) confirms the fact that knowing English is a major factor for a potential professional success. Because of this there are many people mastering English as their foreign language. (Roslina, 2017) Knowing that the English language is a global language spoken in many parts of the world tells us that English as a subject in schools, especially in countries who does not speak English by mother tongue, is of most importance in order to be able to communicate with the outside world. However, it also tells us that the expectations to learn English as a second language is quickly rising in line with our globalizing world.

5.1 Motivation

Studies show that working with children’s literature gives a wider range to find material that fits with the individuals needs and interests. Provided that English is a subject of most importance and therefore often quite stressful amongst students, teachers all around the country try to find a way to make the learning process fun and interesting. English

classrooms in Sweden today use different types of bought teaching materials to find a thread throughout their education. Research shows that in order to motivate students’ in their English learning process they have to be center of their education, an aspect that might be missed whilst working with teaching materials.

Birketveit & Rimmeride (2017) let students choose which children’s literature they would like to work with in their study, as a result the learners experienced a state of flow which enhanced their motivation to learn. Four skills that is necessary to learn within the English

15

language is reading, listening, writing, speaking. These four skills can be taught in different ways that is more or less motivating to EFL-students. Roslina (2017) and Neuman & Kaefer (2018) both mentions that students in low-income areas generally have low motivation to attend and learn in their school. The reasons for low motivation for learning English in the early years are several. Roslina (2017) identified that infrequent tutors and tutors without a formal education, inappropriate teaching material and simply a lack of attention in early years are factors that may disturb ESL-students English education. We have learnt that motivation is a crucial phenomenon in all learning, not least in English as a second language. (Birketveit & Rimmeride, 2017) To engage students in their learning and make them the center of their own education is crucial to motivate students to appreciate their learning. (Jagtøien, Hansen, Annerstedt, 2002) Furthermore, motivation can be found where the students interest lay, Cavus & Ibrahim (2017) found that mobile phone ownership and interest for them is increasing among younger children, and therefore put the cellphones in the center of the students’ learning.

5.2 Learning goals

Children’s literature can affect the students’ reading comprehension in a positive way if implemented correctly. Whilst exposing EFL-students to children’s literature they get the opportunity to decode a text in two ways, partly through text, and partly to create

understanding through pictures. Pictures cannot be stored in students’ verbal system; however, they can be stored in the imagery system and the other way around. The fact that students are able to decode texts in more than one way to create a greater understanding of the material, and therefore improving their reading comprehension. (Roslina, 2017).

According to Birketveit & Rimmeride (2017) even if a student does not understand 98-99% of the words given in an illustrated book, they can still understand the story following pictures, and furthermore associates the words with what is going on in the story. Discussing children’s literature in smaller groups before, while and after they are being read enhances student’s understanding of the material which can furthermore lead to a greater cognitive development (Neuman & Kaefer, 2018) Louie & Sierschynski (2015) explains that through wordless picture books discussion is where the learning takes place, the material provides students’ opportunities to discuss different outcomes and otherwise book- based oral

16

language. With discussions importance in mind, Vygotsky’s (1934) theory of sociocultural perspective reinforces the fact that learning can be done between two or more individuals. Magnusson (2013) means that when two or more individuals disagree about the same content, they must stand their ground and explain using words to defend their opinion, this while at the same time taking in and evaluating another individual’s opinion, which later on deepens all students involved understanding about the common subject.

Children’s literature has the potential to improve students’ English skills in different ways, Birketveit & Rimmeride (2017) argues reading children’s literature could develop students’ language comprehension, writing style, vocabulary, grammar, and spelling if worked with the right way, their study in particular shows that working with authentic picture books alone improve students writing skills through an increased amount of adverb usage. Cavus & Ibrahim (2017) study agrees with the fact that children’s literature may increase their writing skills. However, they also show that when working with children’s literature in mobile devices even has an opportunity to increase skills such as vocabulary, pronunciation, listening and reading comprehension as well due to the nature of a more adaptive material. Similarly, Roslina (2017) shows us that whilst working with children’s literature that both include pictures as well as text gives the students an increased rate of improving their reading comprehension and decoding of text that are similar to other children’s literature. However, Neuman & Kaefer (2018) tell us that working with read-aloud children’s literature and discussing the material heavily improve EFL-student’s oral skills as they were able to engage in more complex discussions whilst working with the same subject. Neuman & Kaefer (2018), Louie & Sierschynski (2015), Roslina (2017), Birketveit & Rimmeride (2017) and Cavus & Ibrahim (2017) are all in an agreement that working with children’s literature in a thought through way has the opportunity to improve younger students’ cognitive

development in different ways.

In the Swedish national curriculum for English (2018) it is stated that to learn English skills such as listening and reading, you should be able to choose and read different types of texts from different medias. The studies show not only that there is a wide range of different medias where you can find children’s literature, but also in being able to choose could have the opportunity to motivate students’ further education. The curriculum also states that students are supposed to be able to find different strategies to be able to take part of

17

different oral discussions in English. Research shows that reading and working with

children’s literature gives students’ a great opportunity to come across new words and ways to use them in different discussions because they may acquire a deeper understanding of the words when used in different ways such as stories.

Studies show that working with children’s literature gives an opportunity to meet the knowledge levels of the students, because there is a big verity of children’s literature.

Additionally, working with material that interest the students gives them a great opportunity to discuss its content with or without a teacher. The norm for teaching in Sweden has developed heavily during the past 60 years. The national curriculum has been reformed and progressed intact with how that time’s society was like. For example, in Lgr 69 (1969) up until Lpo 94 (1994) you can clearly tell that the norm for teaching and learning is through learning on your own. Information in different forms were to be processed individually to learn. Today teachers work after what is written in Lgr 11, where knowledge should be built on the individuals already accumulated knowledge. Lgr 11 promotes learning with others and therefore also a communicative classroom, where learning is done between different

individuals, not just through the provided material.

Studies demonstrate that EFL-students have multiple reasons to work with children’s literature, such as to rise student’s motivation to learn the language, confidence to speak, vocabulary, written as well as read text. Children’s literature is great material for EFL-students to increase their second language skills. However, studies also show that L1

students do not to the same extent increase and develop their language skills in working with children’s literature, they need to be challenged in more varied ways to expand their

18

6. Conclusion

The findings show that children’s literature can and, in some cases, should be included in young students’ English education. However, I as a teacher must be aware of how I include the material, knowing that different methods may result in different outcomes. As an

otherwise PE teacher, I must motivate my students during a PE session, usually with a game or sport of interest. Furthermore, I must also create a scenario where the students can reach the main goal of the lesson, which in some cases is just a punishment of the game or sport. Similarly, the studies show that children’s literature is just used as a facade for the learning goals of the session. The studies show that I must be aware of how I introduce children’s literature, because different methods yield different results.

Motivation is a key factor to learn anything, especially a language you do not possess by mother tongue, to motivate students to learn is a vital task to succeed as a teacher. The studies show that working with children’s literature in different ways, especially in ways where the students are engaged in what material they are to work with, has a chance to make them more interested in learning the language, thus improving students’ motivation.

Working with children’s literature show that ESL-students may improve skills such as reading, listening, their vocabulary and speaking if the material is engaged in ways that make the students interested. However, the studies show that L1 students do not necessarily improve their language skills as much, which tells us that you should be careful whilst engaging children’s literature in students’ education, the material may not reach the more advanced students the same way ESL-students are, which was a find I did not expect. However, to know that some environments you see in a classroom is not one that makes everyone meet their proximal learning zone is something interesting to keep in mind.

Working with children’s literature in a way that highlights discussion and having to explain the material amongst each other may furthermore improve their cognitive development. Which is a clear goal of the Swedish national curriculum as a whole, the findings also show that depending on how you include children’s literature in student’s education may increase their English skills, such as listening, reading, speaking and writing. However, the findings

19

say that working with children’s literature takes a curtain skill as a teacher, you need to be careful and precise in which skills said teacher is aiming to achieve.

A limit of this research is the fact that working with children’s literature is a broad concept and depending on how you decide to include the material in students’ education the results will vary. Clearly described methods on how to integrate children´s literature into the teaching to reach the aims and goals of the curriculum need to be studied? Upcoming projects within this subject could include more narrow methods and what those methods improve, e.g what does read-aloud sessions improve?

20

7. References

Birketveit, A., Rimmereide, H. E. (2017). Using authentic picture books and illustrated books to improve L2 writing among 11-year-olds. Retrieved from

https://proxy.mau.se/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx? direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1129058&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Cavus, N., Ibrahim, D. (2017). Learning English using children’s stories in mobile devices. Retrieved from

https://proxy.mau.se/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=tr ue&db=ehh&AN=121348499&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Jagtøien, G., Langlo, Hansen, Kolbjørn & Annerstedt, C. (2002). Motorik, lek och lärande. 1. uppl. Göteborg: Multicare

Lgr 11 (2018). Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet: reviderad 2018. Stockholm: Skolverket.

Louie, B., Sierschynski, J. (2015). Enhancing English learners’ language development using wordless picture books. Retrieved from

https://proxy.mau.se/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=tr ue&db=ehh&AN=103383521&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Magnusson, K., Malmgren, Gun & Nilsson, J. (2013). Att göra sin röst hörd: tematisk undervisning i grundskolans mellanår. 1. uppl. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Neuman, B. S., Keafer, T. (2018). Developing low-income children’s vocabulary and content knowledge through a shared book reading program. Retrieved from

21

https://www-sciencedirect-com.proxy.mau.se/science/article/pii/S0361476X17300541?via%3Dihub

Roslina (2017). The effect of picture story books on students’ reading comprehension Retrieved from

https://proxy.mau.se/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=tr ue&db=eric&AN=EJ1143933&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Sweden. Skolöverstyrelsen. (1969-1978). Läroplan för grundskolan: Lgr 69. Stockholm: Utbildningsförl..

Sweden. Utbildningsdepartementet (1994). Läroplaner för det obligatoriska skolväsendet och de frivilliga skolformerna; Lpo 94 : Lpf 94. Stockholm: Utbildningsdep..