Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation

Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits Summer 2018

Supervisor: Jonas Lundsten

The Role of Smart City Concept in

Sustainable Urban Planning from Policy

Perspective

Case Study of Malmö

Maryam Alavibelmana

Robert Fazekas

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our families, who have been always supportive. Also, we would like to thank our supervisor Jonas Lundsten, who has supported our research with great knowledge, support and encouragement.

And, finally, we thank all our interviewees, whose input and expertise was invaluable to conducting this research, and appreciative the time and knowledge they have decided to share with us.

Maryam Alavibelmana and Robert Fazekas Copenhagen, August 2018

Abstract

Smart city as a concept or term is the contemporary buzzword which is referred as a means to deliver urban sustainability. In recent years, different smart city initiatives have emerged worldwide, which are advocated increasingly by the private and public sectors. However, there has been a considerable amount of critiques by social and urban scholars who question the current understanding and practice of the smart city, raising doubt if the current smart city is sustainable. The most frequently mentioned critiques indicate that the current smart city which does not have a common definition and theoretical foundation is intensively dominated by technical perspective and the role of private sector. This thesis aims to find out how this current understanding and application of smart city concept affect the urban planning practices and urban policy-making. By taking Malmö as a case study and conducting policy analyses, the research shows that this trend leads to the project-based practices which in the absence of strategic and holistic vision toward the smart city as a concept might not fulfil sustainability criteria, cannot be a beneficiary means for sustainable urban planning, and is a poor concept for social sustainability. It shows that although private sector is an integral part of smart city practices, public sector -municipality -needs to take leadership position in defining smart city based on the real city’s demand and integrate it into the urban planning strategies.

Keywords: Smart city concept, Social sustainability in urban planning, Malmö, Policy analysis, Urban

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1. Need for sustainable cities ... 1

1.2. Emerge of Sustainability ... 3

1.3. Different concepts for sustainable cities ... 4

1.3. Literature Review ... 7

1.3.1. Challenges and critiques in Smart City concept and projects ... 7

1.3.2. Sustainable development in smart city discourse and the main disciplines... 10

1.4. Context information and challenges ... 12

2. Problem Formulation ... 14

3. Objective and Research Questions ... 15

4. Research Design ... 16

4.1. Method ... 16

4.2. Case study selection ... 21

4.3. Ethic Consideration ... 21

5. Analytical framework ... 22

5.1. Social sustainability in urban planning ... 22

5.1.1 The planners’ triangle ... 25

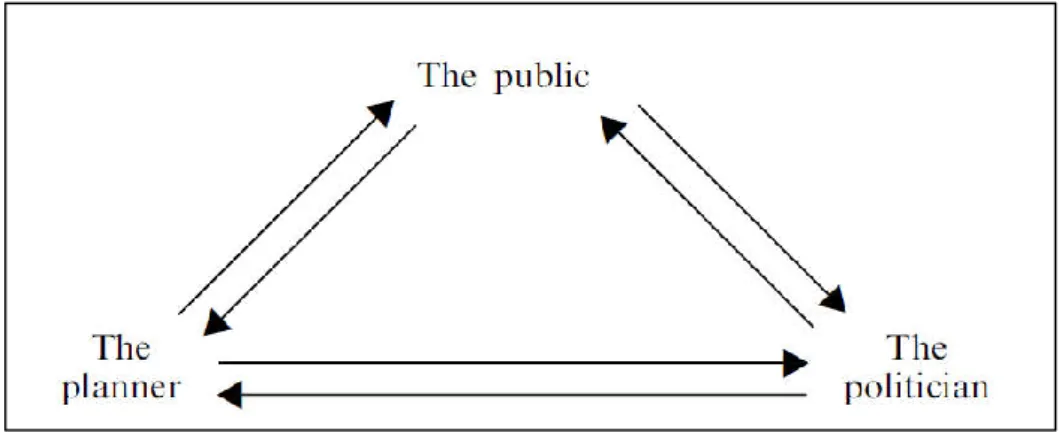

5.1.2. Planning actors: Stakeholder engagement in planning ... 28

5.2. Urban utopia, conception, and visionary ... 29

5.3. Smart city definition and dimensions ... 31

6. Analysis ... 36

6.1. Smart city concept and strategies ... 36

6.1.1. Semantically use of sustainable city and smart city ... 36

6.1.2. Lack of definition, the clear strategic approach, and framework ... 36

6.1.3. Thematic integrated strategies ... 40

6.2. Smart city projects in Malmö ... 44

6.3. Actors and partnership ... 50

7. Discussion and Recommendation ... 54

7.1. The needs for strategic vision and planning, fitting to the city scale... 54

7.2. The tension between stakeholders’ interest ... 57

7.2.1. Public interest vs. private interest ... 57

7.2.2. Demand sector vs. Supply sector ... 59

7.2.3. National scale vs. City scale ... 59

7.3. Potential of smart city concept in Malmö ... 61

9. Recommendations for further study ... 64

10. References ... 65

Appendix ... 74

Appendix 1: Literature review table ... 74

Appendix 2: Interview Guides ... 75

Appendix 3: Extracted quotes from documents... 76

Appendix 4: The brief Description of projects ... 77

Appendix 5: Climate Smart Hyllie ... 79

List of Figures

Figure 1: The majority of publications on Smart City based on subject area. ... 10Figure 2: The main disciplines among which social debates within the smart city have been taken place. ... 11

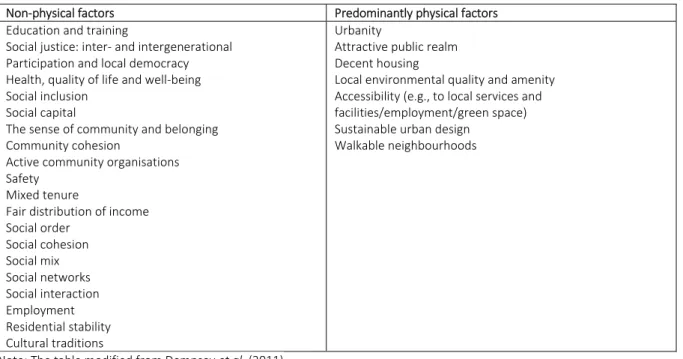

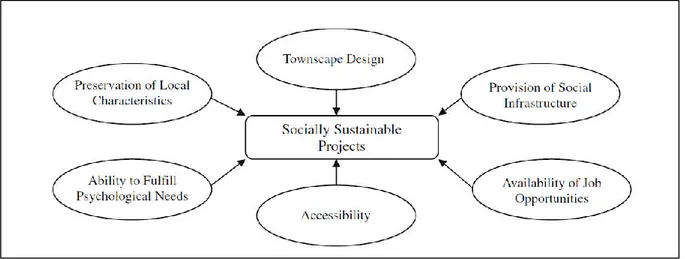

Figure 3: Influential factors of socially sustainable projects ... 24

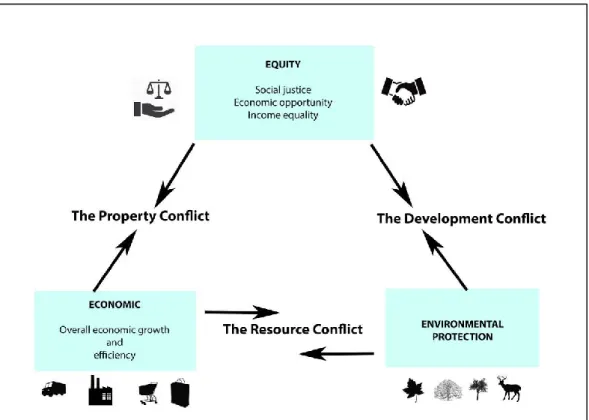

Figure 4: Planners’ triangle ... 26

Figure 5: Lash’s model ... 29

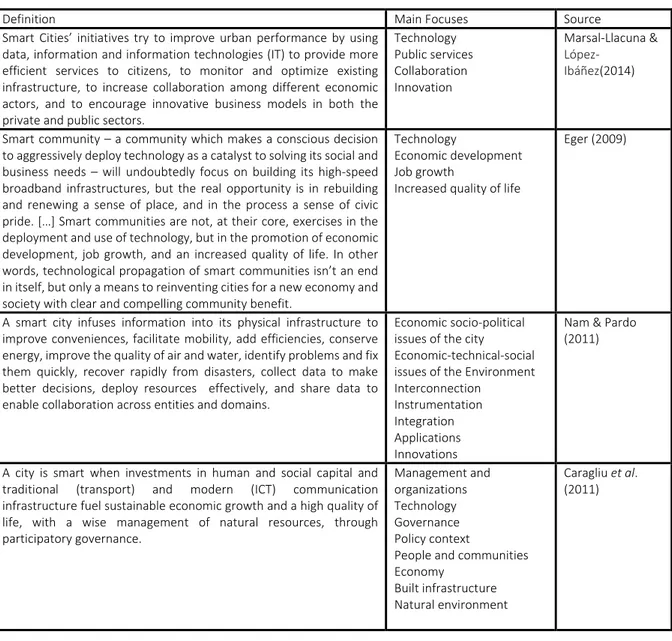

Figure 6: Smart city dimensions ... 34

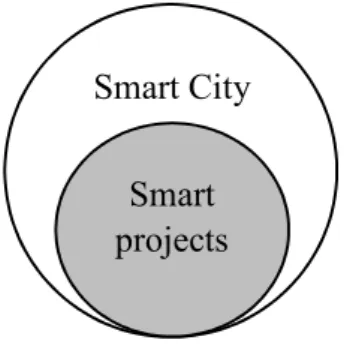

Figure 7: Smart city concept and projects relations where projects are defined based on the smart city concept . 34 Figure 8: Sustainability dimensions in Comprehensive plan of Malmö ... 41

Figure 9: Prioritised standpoints in Skåne strategy ... 41

Figure 10: Mans steps for creating attractive city. ... 43

Figure 11: Prioritised development areas ... 47

List of Table

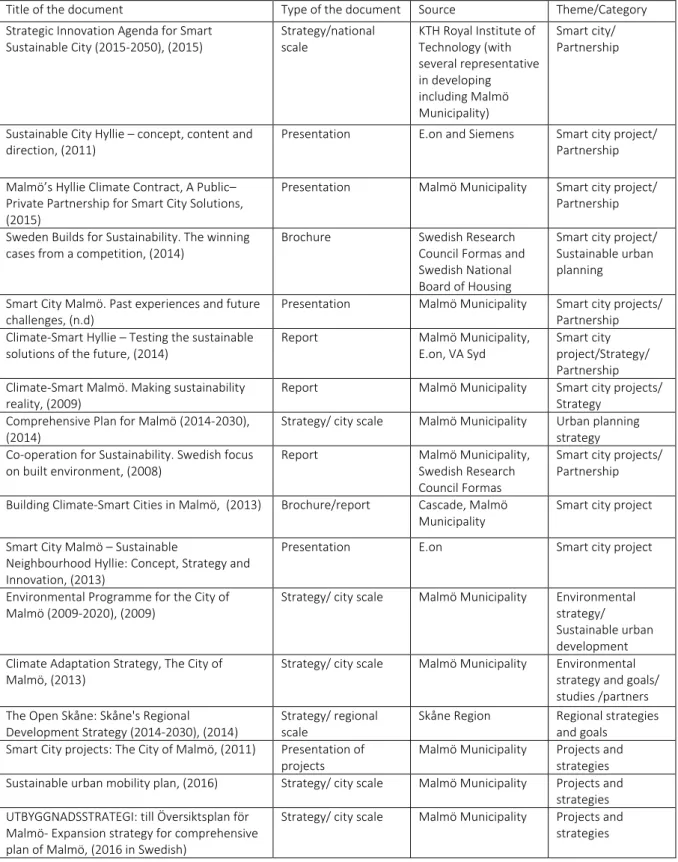

Table 1: The list of documents ... 18Table 2: The List of representatives of interviews ... 20

Table 3: The social dimensions of sustainable development: urban social sustainability... 23

Table 4: Key definitions of social sustainability ... 25

Table 5: Different definitions of the smart city with main focuses ... 32

Table 6: Smart city project actions ... 35

Table 7: List of Smart City projects in Malmö ... 44

Table 8: Themes from literate review and their disciplines ... 74

Table 9: The main goals and actions in smart Hyllie ... 81

Abbreviations:

SSC – Sustainable Smart City SC- Smart City

PPP- Public-Private Partnership EU- European Union

UN- United Nations

1

1. Introduction

There have been different paradigms and concepts to deal with urban issues and complexity, which were dominated in different eras as the leading ones. The contemporary approach, which is getting more and more popular, is Smart City, the concept which is practised and defined in the neoliberal context and presented in many cases as a utopia (Grossi & Pianezzi, 2017) and sustainable development. This concept is being used widely with this promises that it will solve the complexity of urban setting and challenges, promote quality of life, and create sustainable cities (Monfaredzadeh & Berardi, 2015). However, there is no specific definition and framework for this popular concept to define in which areas it should be deployed especially in theoretical discourse within urban planning and social science while several billion Euros have been allocated to that (Vanolo, 2016).

On the other hand, the recent literature started to criticise this concept for different reasons and many of them raising doubt if the current smart city approach is sustainable and also some claimed that is not sustainable (Yigitcanlar & Teriman, 2014; Haarstad, 2016; Vanolo, 2016; Beretta, 2018; Cugurullo, 2018; Martin et al., 2018). One of the frequently mentioned challenges are domination of private sector and technical perspective in current smart city which not only neglect other dimensions of sustainability especially social aspects, but deploying this concept as a means of marketing and branding so that the current practices of smart city are not applied for addressing sustainability or challenges but for branding and business competitiveness even with controversial results.

This research mainly aims to show how this lack of definition along with the domination of techno-private practices could create misunderstanding between the smart city and the sustainable city and affect sustainable urban development. To discover this, city of Malmö is taken as the case study and the way smart city as concept and initiatives play role in the city development and sustainability objectives is analysed.

The following sections provide a background as an introduction. At first, the historical background is introduced about different main approaches and paradigms which influenced urban development worldwide. It shows how various urban concepts which emerged based on urban challenges could affected the municipal and urban development practices, and how sustainability emerged based on those practices. This provides an introduction why Smart City concept as the contemporary buzzword is relevant to be addressed. Then in continues, Smart City relating to sustainability are reviewed among literature, followed by reviewing the context of case study context.

1.1. Need for sustainable cities

Cities have become the primary living space for humans, and since 2007 more than half of the World population lives in urban areas, and studies estimate that this number will increase to 70% by 2050 (World Bank, 2018). This trend projects that people’s lifestyle is facing to transition in relation to economic activities, social structures and their relation to nature due to the fact that primarily people lived and worked in rural areas. Cities are continually facing new challenges in both developed and developing countries. These challenges are complex, therefore a single solution cannot be sufficient to solve these socio-economic and environmental issues. Industrialisation and capitalism stimulated social and economic processes globally which generated inequality in the distribution of wealth. This inequality created different urban areas where residents do not have the same level of accessibility to resources and services (Lipietz, 1995). The increase of the population in cities also causes environmental degradation through the intense usage of individual transportation and land use. This fact turned academia, decision and policy-makers to the need for more sustainable cities, thus various concepts were

2

developed such as the zero-waste city, compact city, eco-city, just city and among these the concept of smart city became one of the responses to these complex urban challenges (Fainstein, 2000; Chourabi et al., 2012; Albino et al., 2015).

Many current urban challenges originated in the industrial city which started to evolve in the middle of the 19th century when mass production led the way to more organised capitalism and later transformed into Fordism (Pacione, 2009). Historically, there has been a general trend of population movement from rural to urban areas with an increasing number of people living in cities and towns which is often driven by the search of work. The priority in the industrial city was accessibility, and as a result, factories concentrated near gateways and consumers (Pacione, 2009). These factories also demanded a large number of workforce thus more, and more labours moved to urbanised areas from the rural parts of the country. The urban structure of the industrial city was primarily characterised by two things: first of all, factories dominated the urban view, while social segregation influenced a division of neighbourhoods (Pacione, 2009). The mass number of labours were mainly lived close to their workplace in crowded and unhealthy districts without basic infrastructure. These living areas were often organised by capitalists and factory owners, therefore the local governments did not have the power or interest to regulate these areas, however this changed when different labour movements widespread and started to protest for labour rights and better living conditions at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries (Mommaas, 2004). Later, expanded voting rights and citizens’ representatives started to improve labour’s neighbourhoods by developing housing and hard infrastructure (e.g., sewage system, concrete road, public lighting and electricity in houses, etc.) in many industrialised countries (Mommaas, 2004; Pacione, 2009). However, the city was highly polluted due to the heating and electricity of residential and non-residential buildings and factories which were based on coal or other polluting resources. This form of the economy created most of today's cities’ urban structures, and these cities were highly unsustainable socially, economically and environmentally, and did not change fundamentally until the Second World War.

States and local governments stimulated and encouraged the economic boom after the Second World War which generated an enormous improvement in the infrastructure especially in urban areas, and the new road systems prioritised individual transportation. Thus, people who lived in the crowded and polluted cities were enabled to move in proximity to the city, in the agglomeration due to the widespread of cars. The urban sprawl caused environmental degradation by involving more lands for the built environment at the expense of the natural environment (Nefs, 2006). In order to have a better understanding of this post-war period and the general mindset, we have to see that the general thinking of people was that social and economic processes and the environment were entirely controllable by human action (Lane, 2005). Therefore, this mentality strongly influenced rapid urbanisation and urban restructuring which generated profound problems in society and nature.

This era was followed by Post-Fordism which was characterised by specialisation, the flexibility of work and based on the development of communication, mobility and mass market. The ‘old economy’ shifted from industrial production to a service and knowledge-based economy. The process of deindustrialisation affected the industrial areas and harbours of large cities from where most of the productions were outsourced to other countries due to economic reasons (Jessop, 2005). The high number of low skilled labours lost their jobs, so the unemployment rate rapidly increased in urban areas, while the rural areas’ economy was unable to provide jobs due to automation (Jessop, 2005).

The oil crisis in 1973 caused an economic recession and accelerated the transformation process. The neoliberal ideology was the response and became dominant in many segments of the economy and urban planning as well from the 1980s. Thus the promotion of market mechanisms and managementalism in the city governments appeared as a solution for urban problems (Harvey, 2005). The so-called neoliberal state became sort of an agent of the market rather than a regulator, and for instance started to privatise public owned properties and to implement neoliberal urban policies, therefore the private sector turned

3

into the dominant driving force, and private investors started to shape cities (Elwood, 2002; Smith, 2002). Since the state needed additional income due to the recession and did not have the financial resource to maintain and renovate publicly owned properties, these properties were purchased by private investors. The value of certain districts close to the inner-city was increased, where often residents lived from the working-class or various disadvantaged social groups (e.g., unemployed, ethnic minorities etc.), thus these districts were the targets of rehabilitation programmes and attracting investors. This phenomenon is called gentrification that may induce displacement due to higher housing prices which can push out the low-paid or unpaid residents and local businesses over time. The consequence of this phenomena was a transformational process from low-class to middle-class neighbourhood (Atkinson, 2000).

Furthermore, liveability became a vital factor in making cities attractive by providing various opportunities to their residents and communities (Florida, 2002). As a consequence, cities have been competing each other nationally and globally for skilled people and investors, therefore competitiveness plays a key role among cities such as among businesses (Florida, 2002). In addition to that from a neo-liberal perspective, the value of competitiveness and the measurement of performance as a managerial tool became more widespread and frequently used to compare cities and in the creation of various city rankings. There have been multiple city rankings with a focus on liveability, business attractiveness, innovation or smartness, etc. The normalising power of neoliberalism generates competition among cities through transforming their differences from the norm they assumed in the chosen criteria to be the best practice. This approach, for instance, can influence the allocation of financial resources to improve the city’s position on different rankings, thus city decision-makers can extract resources from more relevant areas and choosing solutions what do not solve the city’s problems (Kornberger & Carter, 2010).

1.2. Emerge of Sustainability

The socio-economic imbalance in cities is the result of social and economic change brought by globalisation and the shift from industrial development to information development (Egger, 2006). Therefore, a strong need emerged for sustainable cities. The well-known Brundtland Report sparked a debate in thinking around its core themes on the environment, development, and governance. The report has led to an academic response since its release in 1987 from examinations of the word ‘sustainability’ to economic and equity issues and institutions, environment and included urban issues as well. The call for sustainable development was a pragmatic response to the challenges of the period while the goals of the report were widely embraced (Sneddon et al., 2002). Thus, the concept of sustainability has been an integral part of development work since the late 1980s.

The concept of sustainable cities and its links with sustainable development have been discussed since the early 1990s, although the call for sustainable urban development appeared in the 1976 UN-Habitat (Habitat, 1976). A clear definition was formulated for sustainable cities which should be a foundation for all cities: “sustainable cities should meet their inhabitants’ development needs without imposing unsustainable demands on local or global natural resources and systems (UN, 2013 from Satterthwaite, 1992, p. 3).” This definition shows that both developing and developed countries should take responsibility and contribute in order to achieve this goal.

Since 2015, United Nations has 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which are interrelated, although every one of them has their own targets to achieve. One of the goals is Sustainable Cities and Communities sets targets by 2030, and mainly focus on affordable housing, access to sustainable transportation systems, increase the degree of participation and inclusion among residents towards sustainable city planning. Moreover, it highlights the protection of poor and vulnerable residents from

4

different diseases (e.g., poor water quality) and providing inclusive and quality green public space for people. However, according to the UN report (2013, p. 54) these targets “require functioning city governments able both to ensure that such benefits are realised, and to adopt a sustainable framework that encourages the city’s growth within ecological limits.”

In developing countries access to basic public services (e.g., water, sanitation, electricity and health care) remains inadequate. Due to overpopulation and intense migration from rural areas to large cities, challenge the institutional capacities for improving accessibility to infrastructure and public services. Although, upper middle and high-income countries with urban centres that already have access to basic public services face the challenge of increasing efficiency in energy and water usage, reducing the generation of waste and improving their recycling systems. Large and wealthier cities, in particular, may have well-managed resource systems, however they also have larger ecological footprints (UN, 2013). Furthermore, effective urban management is a condition for sustainable cities which requires multilevel cooperation among local, national and global communities and establishing partnerships to mobilise public and private resources.

Creating policy framework for the sustainable development of urban areas is one of the cornerstones as well as democratic legitimacy, and stakeholder consultation is vital since policies are the set of ideas or plans that are used as a foundation for decision-making in fields such as politics, planning, business. In the administrative system, the policies’ role is control of change and show a direction or approach for decision-makers (Solesbury, 2013).

European Union (EU) studies (Eurostat, 2016; 2017) and UN reports (2013) indicate the phenomenon of urban paradox by underlining that urbanisation provides new jobs and opportunities for millions of people in both developed and developing countries and has contributed to poverty eradication efforts worldwide. At the same time, rapid urbanisation adds pressure to the resource base and increases the demand for various services and resources (UN, 2013). Although cities are often the places of jobs and opportunity with access to quality education, healthcare, a wide range of services and also innovation is concentrating there, many cities are characterised by high poverty, segregation, high crime rate and high air and noise pollution. By comparing urban areas to the rural, the labour market is more dynamic by providing flexibility which makes cities more attractive to businesses and people.

1.3. Different concepts for sustainable cities

Several concepts were developed from architects, planners, environmentalists in order to create sustainable cities, improve the current urban structure and tackle socio-economic challenges. In the 1960s, Jane Jacobs an American-Canadian journalist was one of the first activists who drew attention with her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities on the negative effects of urban renewal policies that destroy urban communities and create isolated urban spaces. Her book influenced both planning professionals and the general public by focusing on the needs of residents and the social aspects of urban planning (New York Times, 2006; Gehl, 2007; 2013).

Jacobs’ book and fresh approach created a solid foundation for new urbanism movements such as “just city,” walkable and carless cities which attempt was to design cities for people. The concept of “just city” by Susan Fainstein (2000) argues that urban planners need a normative theory of justice because their motivation to tackle inequality did not produce workable alternatives under pro-growth regimes. Inequality remained in cities mainly due to the imperfection of planning procedures, thus she emphasises the need for involving marginalised social groups by creating democracy, diversity and social justice (Fainstein, 2000; Healey, 2003). Furthermore, Fainstein (2000) highlights the importance that public investments and regulations should support and produce equitable outcomes rather than make the wealthy wealthier.

5

These new urbanism movements also strived to improve quality of urban life by orienting and re-think urban design towards pedestrians and cyclists which ideas were the most popular in European cities, especially in Scandinavian cities such as Copenhagen, and later from the 2000s in New York and some Australian and New-Zealander cities. For instance, by implementing sustainable concepts in urban planning, Copenhagen transformed from a car-dominated city into a pedestrian- and cyclist-oriented city in less than 30 years (Gehl, 2007; 2013).

Furthermore, various concepts were inspired by biological systems and using biologist and environmentalist terms to understand urban structures as ecosystems. For instance, the urban metabolism concept represented a holistic approach to urban planning by modelling complex urban systems’ flows such as water, energy, waste and people etc. (Rotmans et al., 2000).

During the last decade, European cities have implemented “compact city” strategies in their urban development. These strategies focused on effective urban development policies in relation to renewal within the existing urban fabric. These were various densification policies, intensive land use, including the redevelopment of brownfields and other types of underused lands (Van der Waals, 2000; Nefs, 2006). Professionals argue that with densification and intensive land use cities can slow down and control urban spawn, thus cities do not have to occupy more lands for the built environment from the natural environment. Although densification can slow urban sprawl down, research shows that this type of concentration of people and buildings generate more air and noise pollution (Nefs, 2006). Also, building high rise buildings are consequences of densification which often causes alienation and a weak sense of community among residents, therefore it has a negative social and environmental impact (Gospodini, 2002; Nefs, 2006).

The rapid development of technology, particularly information and communications technology (ICT) in the 1990s created a solid foundation for involving new digital solutions and increasing efficiency in tackling urban complexity. Thus monitoring, analysing and optimising complex urban systems and interacting directly with communities and citizens became more accessible than ever before. The concept of “smart city” and other similar terminologies such as digital city, intelligent city, information city and knowledge-based city emerged and started to appear in urban developments and strategies. The concept of the smart city was introduced already in 1994, and after the appearance of smart city projects which were supported by the European Union, the number of publications regarding the topic has considerably increased since 2010 (Dameri & Cocchia, 2013). By nowadays, “smart city” became a buzzword and a part of a new trend of sustainable urban development, while this concept is widely used today, there is still not a clear and consistent understanding of its meaning (Caragliu et al., 2011; Chourabi et al., 2012). Researchers, national planning agencies, municipalities and even private companies often use their own fabricated definitions (Dameri & Cocchia, 2013).

According to Cohen (2015), three generations of smart cities are identified. The first generation is driven by large multinational technology companies to adopt their technologies in order to increase efficiency and innovation in cities, therefore it potentially generates economic growth and attracts Richard Florida’s creative class to the city. In this case the public sector does not have sufficient knowledge of the implementable technology, thus basically they implementing the companies’ plans and solutions without questioning them (Cohen, 2015).

The second generation is led by forward-thinking mayors and city officials to use smart city solutions as tools to improve quality of life. Several leading cities have recognised the opportunity for implementing technology to increase the quality of public services for their residents and visitors as well. These cities often use the latest technologies in their smart city projects and supporting the growth of smart city industries by facilitating network and hold specific smart city expos in their cities (Cohen, 2015).

6

And the third generation started to appear in recent years with a strong focus on collaborative planning and co-creation in smart city initiatives. In this type citizens are important partners in developing projects and active public participation plays a key role by encouraging a bottom-up planning process (Cohen, 2015).

Several European cities such as Amsterdam, Vienna, Barcelona, Stockholm, Copenhagen and Manchester are considered as leaders and role models for implementing the concept of smart city in their cities. Although the majority of smart city initiatives are implemented and get attention in highly developed countries and regions (e.g. EU, USA, South Korea, Japan etc.), large and developing economies such as China, India, Brazil with rapid urbanisation are also focusing on integrating the concept of smart city in their urban strategies and policies, therefore they have started to become an attractive market for investors (Cohen, 2015). The implemented smart city initiatives have various characteristics by each city or country. Several cities implement smart city projects in one specific district and concentrating on smart city solutions by creating high-quality housing, these are for instance in Hafencity (Hamburg), Nordhavn (Copenhagen), Hackbridge (London), Hammerby Sjöstad (Stockholm), Oulu Arctic City (Oulu, Finland) and also Hyllie in Malmö while the others are promoting e-governance which is the application of ICT for delivering public services and exchange of information between the public sector and citizens. The City of Amsterdam created, for instance, an online platform for public participation and co-creation in order to develop a better city for their residents (Cohen, 2015; Trivellato, 2016). The City of Barcelona established a wide collaboration with private sector and research institutes within the scope of Barcelona’s smart city strategy. Thus, the strength of Barcelona’s smart city strategy relied on its comprehensive approach which based on a clear governance model to support the smart city strategy which also resulted in better and more efficient coordination of the different internal and external stakeholders (Ferrer, 2018).

Knowledge-sharing and cooperation are fundamental in smart city projects due to its complexity, therefore the distribution of tasks between different actors and stakeholders is essential. Neither local authorities, urban planners nor private companies able to run smart city projects on their own, so they have to bring new ways of partnership to get complex and multidisciplinary smart city projects workable. Public-private partnership (PPP) is often the framework between them which is, in general, a long-term cooperative arrangement between one or more public and private actors (Klijn & Teisman, 2002). Although public authorities and municipalities have the policy-making powers and access to wide range of data, they do not have the financial resources and knowledge to execute a smart city project, especially when the latest technologies are implemented there, thus experienced private companies with the know-how are involved (Klijn & Teisman, 2002; Anthopoulos et al., 2016). However, this process can question the credibility and independence of the public decision- and policy-makers in general due to the large transnational companies’ financial and influential power (Buck & While, 2017). In addition to this, national and local governments often lack sufficient expertise to bid effectively, let and negotiate contracts, and the legal instruments to enforce the contracts of those projects (Buck & While, 2017). Since the newer technologies for implementing digital solutions in cities are getting more affordable and available, the need for integrating the concept of the smart city in urban strategies and policies became relevant and urgent (Trivellato, 2016). In fact, numerous cities are struggling with the interrelated phenomenon, and urban planners are responsible for dealing with and tackling them. This indicates the key role of urban planning in relation to the smart city concept, especially by considering the recent critiques against the smart city concept that challenge the sustainability of the smart city concept. The representatives of the smart city concept often claim that it is a solution to manage complex environmental and socio-economic challenges, however, many critiques have emerged in need of re-defining smart city model and initiatives as it might neglect the complexity of a city, especially the social aspects.

7

Many of the concepts mentioned above have become integrated parts of urban policies and sustainable urban strategies. The concept of the smart city, such as other concepts, was created recently as a solution to solve urban complexity and improve the quality of urban life, and assisting sustainable urban development. However, the current application and understanding of smart city concept have faced intense criticism from different perspectives, raising this question if this concept is as beneficial as it is advocated by developers or not. These critiques are covered in the literature review section.

1.3. Literature Review

This section aims to give an overview of the recent literature on smart city concept and projects. The literature on the smart city is very fragmented addressing different issues from technical to ethical ones. The main perspective to sample the literature has been generally in line with the context of the thesis which aims to look at the smart city from social and urban science perspective in relation to sustainability.

Based on the review of the literature, the section is divided into two main parts. The first part covers the critical perspective which has massively emerged among literature especially from the social and urban point of view, and the second one addresses the main approaches among those literatures that tried to look at the smart city from specifically sustainability point of view.

1.3.1. Challenges and critiques in Smart City concept and projects

There has been a growing body of literature which criticising the smart cities in recent years, especially from urban scholars, suggesting in general that there is taken insufficient account of social and political consideration in envisioning smart cities (Cowley et al., 2018). In fact, although the smart city is expected to lead society towards sustainability and is meant to improve quality of life (Sujata et al., 2016), there are some controversies over its contribution toward sustainable development, communities, and people. The main concerns relate to its possible destructiveness end to the societal aspect which might be overlooked by the current interest of leading cities to implement some certain smart policies and projects.

Four main schools of thought among literature in relation to smart cities are recognised by Kummithaa and Crutzen (2017), namely restrictive, reflective rationalistic, or pragmatic, and Critical school of thought. Through this categories, they aimed to show that the critical debates within the literature have attracted attention dramatically since 2014, however, the first type of critiques had started among the second school of thought.

At the beginning, the debates were some reflections on smart cities, taken a positive stance and claimed that these technologies would enhance the humane capacities, economic prosperity, and ecological integrity, though they expressed concern about the dominant role of private markets or some speculative “risky and arcane” conditions under which municipalities have to invest massively in private-oriented smart products as infrastructure (Kummithaa & Crutzen, 2017).

This is because most of smart cities activities are associated with large private companies like IBM, Cisco, and Siemens, etc. as the main promoters (Vanolo, 2016; Grossi & Pianezzi, 2017; Martin et al., 2018) while city is a complex socio-economic phenomenon so there is a concern about overlooking this complexity and taking the city as an implicit phenomenon by private corporates (Greenfield, 2013), especially regarding social challenges. The sensitivity of this issue becomes more considerable if we remember that many urban and social policies developed by planners and public sectors have failed to

8

solve or anticipate the interrelated problems in some cases, if we, for example, observe the process of gentrification and segregation in urban planning (Batty, 2014).

In this sense, there is a concern about taking control by the private sector which seeks mainly profit and competitiveness, not the public concerns in the condition that studies claim the competitiveness and social cohesion cannot be convergent (Monfaredzadeh & Berardi, 2015; Trivellato, 2016).

The dichotomy between sustainability and competitiveness or entrepreneurialism has been a highly-mentioned concept in smart city debates in order to show that the former has been sacrificed for the latter. This debate tries to remark that these two dichotomies might not have much in common (Monfaredzadeh & Berardi, 2015; Grossi & Pianezzi, 2017) or elaborating that technocratic and entrepreneurial approach to urban development not rooted in the substantial requirements for urban transformation (Haarstad, 2016). Experiences in many cities have shown this scarification. For example, City of Austin has attempted to merge the entrepreneurial agenda with the sustainability agenda, but in practice, it used the latter just as a selling point to facilitate the former (Mihailova, 2017).

Since the contribution of literature, which was dominantly technology-oriented, could not justify the benefits of the smart city over its possible negative implication, the discursive tried emphasising on prioritising people over the technology such as engaging people and other stakeholders in planning or focusing on innovation. By doing so, they drew attention to humanistic elements over technology (Eger, 2003 and argued that smart cities would need to focus on people and their capabilities more than just concentrating around ICTs or technology (Kummithaa & Crutzen, 2017).

The final and the recent school of thought, by Kummithaa and Crutzen (2017), which was recognised as the Critical school of thought aims to “encapsulates the growing dissatisfaction around the very concept of the smart city and its practice.

The critiques go even further to tackle the softer social issues which is difficult to measure such as happiness: if people in this very smart city have necessarily happy life, good relationship, and sense of community? Do they really enjoy and perceive their life as good standard (Hollands, 2015)? In some projects, smart initiatives could positively contribute to improving healthcare service like smart housing for elderly or patients. Yet, even in those projects, the challenges remain such as potential over-reliance on automation, the “medicalization” of the home environment, privacy and security, informed consent, plugging issues, and psychological aspect (Demiris & Hensel, 2009).

In these debates, the central concern are toward citizens and their communities who might be the final loser of this game due to the threat of losing social inclusion, their right to the city, and being burdened more with the economic and social implications which will happen by privatisation of urban space (Beretta, 2018). In fact, although the smart city concept and those who advocate it are claiming ‘smart city is for people,’ critics argue that it is not much clear that what exactly people means, to what extent, and in which ways it can help them (Haarstad, 2016). Cowley et al., (2018) by looking at public perception towards smart projects aimed to show that the magnitude of current dystopian speculative to smart city in the literature is not near to reality, but finally they could not deny that there is a dominance of ‘entrepreneurial’ and ‘service user’ modes of smart city than the real social perspective towards citizens.

Vanolo (2016) who analysed the role and place of citizens in envisioning the smart city concludes that “all imaginaries in smart city concept speak about the citizens of the smart city and speak in the name of them, but very little is known about citizen’s real desires and aspiration (Vanolo, 2016, P.36).” He mentions that the citizens’ voice is absent in many envisioning smart city and where they are considered as an active citizen they are discounted as an urban sensor. So, he raises concern about the future of citizens, as political subjective with the right to speech or privacy being with responsibilities, in the smart city in which they might be subjected by technologies that will hamper their freedom.

9

All the given challenges implying the threat for social justice in general (Mihailova, 2017; Beretta, 2018) because the studies showed and argued that for example, digital innovations have potential to disempower and marginalize citizen and the benefits of these innovations will not be distributed evenly (Martin et al., 2018). Generally, critics are calling that there is a need for re-thinking about our life in a “very technologically driven, corporately controlled, heavily marketed, even environmentally sound smart (Hollands, 2015, P.73)”, and ask the smart city about its contribution toward social and political aspect of development (Kummithaa & Crutzen, 2017; Han &Hawken, 2018).

The technical perspective in the smart city is also seen in tension with the real demands of society (Angelidou, 2015). The domination of technology in practicing current smart city is mentioned as a force in smart city concept.

Smartness is right now identified with innovation hinged on the technology, precisely those technologies that the economic actors involved in the process of providing public goods are able to provide (Grossi & Pianezzi, 2017). It is projected that the annual spending on the smart city projects will be $16 billion by 2020 (Angelidou, 2015) or by another estimation, the global smart city technology market will worth more than $27.5 billion by 2023 (Grossi & Pianezzi, 2017). And, with the help of the technology advancement, an increasing number of technology vendors and consultancies are looking for a niche in smart city product market (Angelidou, 2015) and the benefit that they can obtain out of that, based on the given figures, is huge (Grossi & Pianezzi, 2017).

This technology push, which implies continual releasing new products into the market due to the rapid advancement of technology, is based on supply without considering the expressed need of society. Therefore, it is seen in tension with the demand pull, referring to the solutions and products which is developed and commercialised based on the scientific research in response to the demand on the side of society (Angelidou, 2015; Buck & While, 2017). In studies, it is mentioned that there are asymmetries in the and-demand side of the smart city so that the current smart city projects are more supply-driven (Angelidou, 2015; Buck & While, 2017)

All these increasing critiques can be related to the insufficient consideration of social dimension which is overlooked on the expense of understanding more technical aspects of smart cities to the benefit of environmental practices (Monfaredzadeh & Krueger, 2015). However, many critics argued that primary objectives of the smart city like economic growth or energy efficiency, which are still defined in a consumerist culture, not only could not promote social equity, also cannot protect the environment alone (Martin et al., 2018).

So, among all, one of the most recognisable critiques is about the unsustainability of the smart city. Many scholars are questioning if smart city is sustainable or recall it as unsustainable (Yigitcanlar & Teriman, 2014; Haarstad, 2016; Beretta, 2018; Cugurullo, 2018; Yigitcanlar & Kamruzzaman, 2018) not because of possible breakage of three main pillars of sustainability and lack of social consideration, but even based on sustainability criteria even in environmental goals which is the dominant aspect of current smart city (Yigitcanlar & Teriman, 2014; Cugurullo, 2018). Colding et al., (2018) by an extensive review of Smart City discourses concluded that there is a lack of clear sustainability contribution within the smart city concept. Moreover, some scholars by conducting empirical study proved this claim, showing this is not only based on the theoretical and political analyses e.g. economic growth and neoliberal ideology (Buck, 2017; Grossi & Pianezzi, 2017; Martin et al., 2018), citizen right (Vanolo, 2016), urban future (Angelidou, 2015), entrepreneurial competitive urbanism (Buck, 2017), etc.

For instance, Yigitcanlar and Teriman, (2014) showed that smart project could not necessarily succeed in CO2 emission, adding that smart city lack sustainability contribution. Cugurullo (2016, 2018) also showed the same shortcoming in eco-city which was disconnected from the natural environment and insensitive to the rest of the built environment in one case (2018) or just was a means of preserving some

10

specific economic and political targets -seeking economic growth to preserve political institution ruling classes (2016).

So, several scholars are recommending further investigation and research on sustainability in smart city or even re-defining the smart city concept and model (Haarstad, 2016; Ahvenniemi et al., 2017; Bibri & Krogstie, 2017; Colding & Barthel, 2017; Ibrahim et al., 2017; Trindade et al., 2017; Macke et al., 2018; Yigitcanlar & Kamruzzaman 2018).

It should be mentioned that this critiques towards sustainability of smart city are in the condition that smart city concept and projects are branded as a sustainable city or utopia by its main advocates (Grossi & Pianezzi, 2017), became a buzzword even, in some cases, as a replacement for ‘sustainable.’

1.3.2. Sustainable development in smart city discourse and the main disciplines

Our literature review showed that as much as the call for re-thinking about the smart city is emerging, there is still no specific and holistic framework and common definition which based on that contribution of the smart city in social sustainability can be mapped. Almost all articles mention to this fact that the smart city does not have a common and agreed definition (Hara et al., 2016; Vanolo, 2016; Grossi & Pianezzi, 2017) as well as a strategic vision to design long-term strategies (Hara et al., 2016).

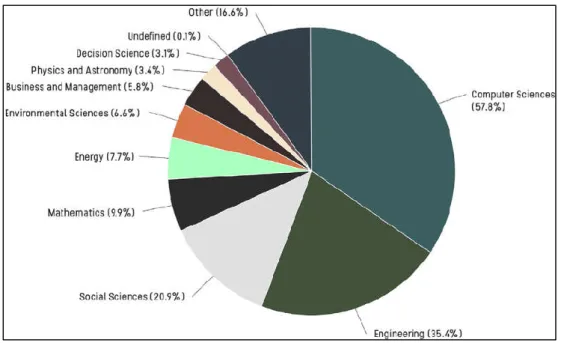

In this sense, one point which can unlock why many critics target technical-oriented perspective of the smart city is looking at the ways and fields of theoretical discourse within which smart city is discussed (Mora et al.; 2017). The domain of discourse on the smart city has taken place in other subject areas, mainly computer science, more than social science. Figure 1 by Colding and Barthel (2017) shows how and from which perspectives smart city has been defined and discussed so far.

Figure 1: The majority of publications on Smart City based on subject area (Colding & Barthel, 2017, p.97).

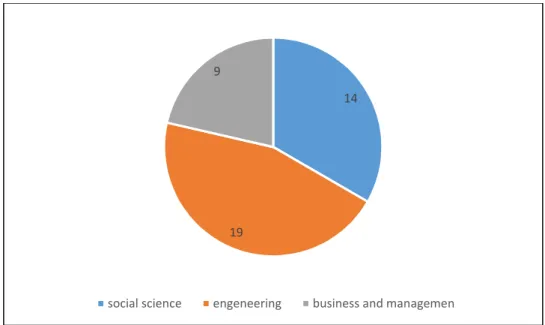

They indicate that the third largest publication falls in the socially based subject. However, our review which was among this social discourse on the smart city revealed that even these socially-based debates had been more developed in engineering and business disciplines than social discipline (Appendix 1,

11

Figure 2). This showed us still the technical and business disciplines have more interest in smart city literature even they try to address the social aspects.

Figure 2: The main disciplines among which social debates within the smart city have been taken place.

Based on our literature review three main approaches can be seen in the literature (Appendix 1, Table 8):

First, the articles that challenge or criticise the smart city from the social point of view. This group has a general critical perspective or analytical arguments based on one social issue such as privacy, equity, neoliberal policies, etc., ending in some recommendations.

Second, the group that evaluated or analysed cases or one smart city project, to explore smart city’s relation to the sustainable development or assess its performance in relation to one criterion of sustainability.

And, the third group, which were quite few, tried to develop a model based on challenges in the smart city that all were a technical solution from engineering disciplines. They tried to develop a model placed with a single aspect like co-design in smart city projects (Mayangsari & Novani, 2015).

It is found that if there is a discourse on the contribution of the smart city to social aspects, they are mainly critiques which result in some general recommendation. For example, Monfaredzadeh and Krueger (2015) had a debate with the aim of investigating social factors in the smart city, but still, they limited their contribution to some arguments and critiques.

Also, Trivellato (2016) tried to assess Milan smart city’s initiatives based on social sustainability. However, he used and modified a framework from Colantonio and Dixon (2009) that is based on the criteria for measuring urban regeneration in Europe. This study is an assessment based on a theory outside the smart city framework and also based on quantitative criteria which were used for a qualitative assessment.

Ahvenniemi et al. (2017) express that “there is a much stronger focus on modern technologies and “smartness” in the smart city frameworks compared to urban sustainability frameworks.” Moreover, it is argued that the smart city is dominated by politics of data-driven, innovation, technology, and

14

19 9

12

economic entrepreneurial urbanism, rather than the complex socio-cultural and environmental context of urban setting (Haarstad, 2016; Macke et al., 2018)

Explanation of Valono (2016) might shed light on this dominant trend by the private sector or technical perspective which mentioned among critiques. He elaborates that the smart city concept did not have a theoretical foundation and defined mainly by companies like IBM and Cisco. He explains that the (valid) process for conceptualising smart city cannot track back as a theoretical concept.

In another study by Mora et al. (2017) it is indicated that “the knowledge necessary to understand the process of building the effective smart city in the real world has not yet been produced nor have the tools for supporting the actors involved in this activity (Mora et al., 2017, P.20).” He concludes that there is a lack of intellectual exchange among those conducting research and isolation from each other, the disconnection which can also be seen between communities lives and the knowledge of the smart city. This point is mentioned in another way by Pierce et al. (2017) who believes the smart city is pluralistic and incoherent social organism with blurred boundaries and conflicting logic and extremely complex challenges. In this sense, Mora et al. (2017) believe that this trend can put future development of this new but divided area of research at risk.

1.4. Context information and challenges

Malmö as the third largest city of Sweden has been undergoing a transformation from an industrial city into an eco-city, and consequently, Malmö’s strategy has strived to market Malmö as an environmentally sustainable, entrepreneurial, and knowledge-based city in order to attract businesses, creative class and people to invest and live there (Mihailova, 2017). Referring Malmö to the knowledge or entrepreneurial city implies that Malmö is a city where its economy is based on attracting talented people and organisations (Mihailova, 2017). In the same regard, Malmö has been mentioned as one of the innovative cities and one of eight emerging tech hubs in the world (Business Sweden, 2015).

As a city where undergone post-industrial urban regeneration, city policy-makers have focused on environmental sustainability sometimes at the expense of equity in the city. For instance, in urban regeneration, there has been a focus on housing developments with advanced environmental solutions (Holgersen & Baeten, 2017; Mihailova, 2017).

Some projects like Bo01 and Augustenborg Eco-city, succeeded to brand Malmö as a sustainable city in environmental solutions in urban planning, although scholars mention to a socio-economic polarisation and segregation which has remained and in some cases reproduced because of those policies and plans (Baeten et al., 2017; Holgersen & Baeten, 2017). Due to this focus, it seems not only policies might neglect other dimensions of sustainability such as the social dimension, but also they resulted in even environmental gentrification (Sandberg, 2014; Mihailova, 2017).

However, Comprehensive plan for Malmö (2014) regarding its transformation believes that “The City of Malmö has experienced a successful transformation from an industrial city in crisis to a modern, environmentally aware and forward-looking city. This new comprehensive plan is a strategy for a new era, looking towards Malmö in the 2030s” (Comprehensive plan for Malmö, 2014, p. 2). However, it could not decline that "Malmö is partly characterised by segregation and social disparity where differences in living standard and public health between different city districts are large (Comprehensive plan for Malmö, 2014, p. 4).

Most studies endorse the Malmö’s succussed in heavily investing on green and environmental urban development but lags behind the social aspect of that (Anderson, 2014; Nordic City Network, 2014; Sandberg, 2014; Mihailova, 2017). This issue is interesting to notice when we look at the previous

13

studies which had recommended that ‘knowledge city’ is no longer the objective that Malmö primarily needs to strive towards. Today there is a great need for the city to be more equal, connected and networked (Nordic City Network, 2014) while, still, some recent studies mention to Malmö’s problem of physical segregation and attribute it to those green type of development (Mihailova, 2017). Our early investigation, also, shows that the largest investment in the smart city as part of those green development (e.g., Hyllie) went mainly for environmental and economic purposes.

In this regard, there has been trying to start changing this direction toward more social sustainability in recent years. For example, the Malmö city set up a commission to produce a document and plan for social sustainability in which, though, the social challenges of the city are introduced and analysed base on the health issue and perspective (Commission for a Socially Sustainable Malmö, 2013; Malmö Stad, 2017). Moreover, the Municipality in partnership with Malmö University created a research lab to bring social innovation in order to tackle social challenges in the city (Malmö University, 2015).

Another issue as contextual information which is related to shaping policy in urban development and the smart project in Malmö is housing policy and trend as the main investment of smart projects went for housing.

The recent trends in housing policy, which has been affected by the changing political atmosphere, resulted in a shift from social housing to the neo-liberal and market-driven system (Andersson & Turner, 2014). These changes in policies paved the road for further deregulations and in favour market-based cooperative housing (Andersson & Turner, 2014).

One of the examples shows the effect of this trend on the urban practice is Hammarby Sjöstad, a so-called Eco-district from Stockholm which is a good example as a result of neo-liberal housing policy, and it is introduce as a reference for future sustainable urban development in Swedish cities, where the smart solutions were used (Khakee, 2007). The development in Hammerby Sjöstad was the first large-scale urban renewal project in Sweden which strongly implemented the neo-liberal planning elements by favouring private developers and setting high quality of housing in order to attract high income residents (Khakee, 2007; Andersson & Turner, 2014). The project became internationally recognised, and it has been taken as a positive case and role model for sustainable urban development (Khakee, 2007). However, the new district suffers from negative social effects such as lack of social cohesion, social mix, affordable rental apartments and the area is identified with low cultural diversity and segregated with high-income residents (Ignatieva & Berg, 2014; Cele, 2015).

Similarly, several studies show (Taşan-Kok, T., & Baeten, 2011; Baeten, 2012; Sandberg, 2014) that the urban planning in Malmö has shifted to a rather neoliberal planning approach in order to assist in the transformation process and to attract high-income and highly skilled residents to the city. Moreover, the same approach and same language in introducing the smart city projects in Malmö such as Hyllie and Western Harbour are see which raise the question about the role of smart city projects in sustainable urban planning in this city.

These political changes are considered dramatic since public housing was one of the cornerstones of the Swedish welfare-state. Therefore, this housing trend questions that if public housing companies can continue working as an important actor for social sustainability in these times when they have to adopt to market conditions.

14

2. Problem Formulation

Taking the previous debate and challenges of the current smart city into consideration, we define the problem based on the current dominant practice of smart city mainly focused on the two main issues. First is related to unsustainable understanding and defining the smart city by the domination of technical perspective and practices (Mora et al., 2017) and lack of integrated discursive (Bibri, 2017) which resulted in the lack of social consideration in the smart city and domination of environmental practices. The second point is related to the branding and marketing practices and the domination of private sector in defining and developing the concept and projects (Angelidou, 2017) which resulted in applying this concept in some developed countries as a means of competitiveness rather than sustainable urban development. These two points which can be seen related are elaborated more in the following paragraphs:

The current smart city concept, which is embedded in neoliberal, techno-centric vision advanced in industry-policy discourses especially in Europe and North America, is primarily technical and digital (Vanolo, 2016; Mora et al., 2017; Martin et al., 2018). In this sense, there is also an increasing concern regarding the role of the private corporation in defining and envisioning smart city so that many label the smart city as ‘private city,’ ‘entrepreneurial city’, or ‘corporate smart city’ (Vanolo, 2016; Grossi & Pianezzi, 2017). On the other hand, in parallel with this fact that Smart City has become a global phenomenon, it has become a fashionable term, being used for branding or marketing purposes with a lack of integrated approach covering sustainability concerns. Thus “the fashionable term ‘smart’ has started to replace ‘sustainable’ in the brand of many projects, for example, China’s Tianjin Eco-City is now also branded as Tianjin Smart City.” (Yigitcanlar & Kamruzzaman, 2018, p.57)

As it mentioned, these two identified points can be considered interrelated. Due to the lack of holistic and integrated view and definition on the concept of the smart city, and also the absence of social dimension in theoretical debates, this trend continues the current technical practices with all its shortcomings and cannot shed light on the missing actions for actors (Bibri, 2017). So, in this absence, the current private-sector-domination, and serving smart city as branding can continually create a misunderstanding between sustainable urban development and this current smart city for policymakers and planners, shifting the implementation of smart city in planning from a sustainable to one- dimensional approach in urban development (Parks, 2018) which can benefit mainly private sector rather than the city and citizens. Policy makers and practitioners increasingly look at researchers for answers to complexity and challenges which raise serious dilemmas, and at times, overwhelmingly perplexing questions (Tonts & Thompson, 2008). Since urban concepts and paradigms affect the municipal plans and practices and also can shape cities, therefore, it is vital to shed light on this phenomenon which received many criticisms.

This trend becomes more crucial for cities such as Malmö which is in transition and suffering mainly from social problems on the one hand, and is massively trying to apply smart-environmental urban projects on the other hand (e.g., Smart Hyllie where are presenting as a model for the future urban development of Malmö). This focus and investment on climate and environmental approaches are in the condition that the main critiques and challenges about Malmö’s policies in urban development is related to social exclusion, segregation, polarization (Holgersen & Baeten, 2017) and gentrification in urban setting (Beretta, 2018) the same issues that critics relate them to smart city (Anderson, 2014; Sandberg, 2014; Mihailova, 2017).

Also, one point is considered to be highlighted: ‘Entrepreneurial and branding’ which is a key characteristic of current Smart City in general (Angelidou, 2017), and, also, has been Malmö’s strategy in specific (Mihailova, 2017). The literature, especially about cities such as Malmö which undergone the post-industrial transition to a knowledge-based approach, showed that being sustainable or precisely socially sustainable and entrepreneurialism has been blurring (Mihailova, 2017).

15

3. Objective and Research Questions

Based on the problem formulation, the objective of this thesis to see how the current smart city which is techno-private-oriented in definition and practice, without social consideration in theory and practice, affect a city and sustainable urban development, or municipal practices as organization monopolise the city planning. In fact, it is aimed to explore how a concept with the given characteristics and without a common definition can be translated into the strategic plan for city development.

Urban planning affects the future of a community with their abilities to understand the history of the community, to respond to the forces for growth, and to anticipate the future of the social, economic, environmental and cultural status of a community. It is not possible to develop a plan for an area before understanding it (Wang & Hofe, 2007). Therefore, without looking at a real case to find out the trends and implications of policies and projects, there is impossible to address gaps within a specific discourse. For this, we take Malmö as a case to address the research question and aims. So, analytical research through which it is possible to understand the past and the present, in order to make recommendations regarding how to predict the future, shapes strategies to direct future is aimed (Wang & Hofe, 2007). Therefore, the research questions are formulated as the following:

How current understanding of the smart city concept affect the strategies and practices in sustainable urban planning? And, what is the understanding of the smart city concept lying behind the formulations in policy making?

To answer these questions as it mentioned before a case is taken to explore how the concept of the smart city is considered and applied in urban policy-making and strategy plans, and how the policymakers and planners are dealing with that: for managing the complexity and as an approach to develop sustainable city or to deploy it based on techno-environmental perspective which is dominated in private sector practice and values. In fact, it tries to find out what are the assumptions and values of the policy-makers and planners in relation to smart city concept and what is its relation to (socially) sustainable urban development.

16

4. Research Design

4.1. Method

A qualitative methodology for data collection and analysis is applied to this thesis since this is preferred when the phenomenon is new (Yin, 2014). The internal realism is taken as an ontological perspective which leads to objective epistemology (Perri & Bellamy, 2012). This is due to our objective and the position of researchers against the data. For this, researchers are independent of data and mainly rely on the existing ones since it tries to find out the reality of what has happened according to policies and projects. Therefore, the epistemology of research is realism, and the investigator is capable of studying a phenomenon without influencing it or being influenced by it (Sale et al., 2002). Therefore, the main method is ‘Document Analysis.’ “Document analysis is a systematic procedure for reviewing or evaluating documents—both printed and electronic material. Like other analytical methods in qualitative research, document analysis requires that data be examined and interpreted in order to elicit meaning, gain understanding, and develop empirical knowledge (Bowen, 2009, P. 27).”

Documents of all types can help the researcher uncover meaning, develop understanding, and discover insights relevant to the research problem (Merriam, 1988). It can be used both as a complement to other research methods and also as a stand-alone method (Bowen, 2009). Atkinson and Coffey (1997) refer to documents as ‘social facts’ which are produced, shared, and used in socially organised ways (cited in Bowen, 2009, p. 47)

Documents contain text (words) and images that have been recorded without a researcher’s intervention and vary in terms of forms, including summaries, organisational or institutional reports, agendas, books and brochures, advertisements, background papers; diaries, journals; event programs, maps and charts, newspapers press releases, program proposals, survey data, various public records, etc. Among them, Non-technical literature, such as reports and internal correspondence, is a potential source of empirical data for case studies in document analysis (Bowen, 2009).

In this research, our main documents encompass strategy and political documents of Malmö Municipality about the smart city, urban development, and social sustainability. These documents as main plans and policies describe the main objectives and strategies, prioritising where development will occur when development is expected to occur, and who will be part of or be affected by the future development (Wang & Hofe, 2007). They are in the form of strategy documents and summaries of plans, agendas, brochures reports, and presentation of policies or projects.

Our sampling for selecting document is mainly based on ‘where’ and by ‘whom.’ So, the resource to retrieve documents is from Municipality of Malmö and the manager of the relevant department, and also from companies as Municipality of Malmö’s partner and co-planner, e.g., E.on.

The time of releasing and publishing of document could not be an issue in sampling as the policy and plan documents in urban development covers a time span as they define the road maps of development for the future. In fact, this criterion becomes effective when the document’s timescale has been finished, being replaced by the new one. However, those previous documents are vital resources to track the history of planning. In fact, the target of documents and the point that they are considered as the current political reference for decision-making are important. This thesis relies on the last version of documents for planning which are mainly plans for 2030 and produced since 2016, 2014 and 2009.

Most main strategy and political documents have the English and Swedish versions. In this thesis the English version of documents are the basis at first place, since regarding one of our problem which is the usage of Smart City for branding and marketing, we aim to see also the possible international perspective of the policies and plan. However, the Swedish version of them are considered, and also if

17

for an important document, the English version has not been provided, the translation of the document is used.

Like other methods, document analysis has advantages and limitations. The advantages of this method (Bowen, 2009) for this thesis’s aim are explained in the following paragraphs.

One of the important advantages of this research is “Lack of obtrusiveness and reactivity: Documents are ‘unobtrusive’ and ‘non-reactive’ that is, they are unaffected by the research process. Therefore, document analysis counters the concerns related to reflexivity inherent in other qualitative research methods like interviews (Bowen, 2009, p.31)”. This point is very important since we intend to see what is happening in reality so in this way we avoid any possible impressions which policymakers possibly try to make, regarding their contribution, decisions, and plans or try to blur the problems. Also, this point should be mentioned that policy documents are the final instruction which defines frameworks for the future plans and strategies for all segments, actors, and developer and also the public in the long and short term. They are presenting the understanding, aims, and decisions of policy-makers, planners and politicians and are needed without any possible personal control and influence.

Availability: availability of a decision and policy would be important not because of the convenience of collecting data, but since we aim to see what is presented in reality and more important from an international perspective to the public and companies. So, how the smart city concept is introduced and framed in political agendas and how the discourse is framing should be taken into account based on those documents which can be seen by others as well.

Exactness: the inclusion of exact statements and references makes documents advantageous in the research process (Yin, 1994) which is important for this thesis aims to look for the reality of planning. Bowen (2009) also mentions some limitations for document analysis, namely insufficient details, low retrievability, and biased selectivity. We should consider and analysis them relating to this thesis. In case of retrievability, the pint is that sometimes access to the document is blocked deliberately (Yin,1994) which is not applicable for this thesis since the policy document, including in urban planning, are the public documents.

An incomplete collection of documents suggests ‘biased selectivity.’ “In an organisational context, the available documents are likely to be aligned with corporate policies and procedures and with the agenda of the organisation’s principles” (Bowen, 2009, p.32).

In this regard, every main relevant data was published publicly by Malmö Municipality were gathered. As it mentioned before, this kind of documents define the decisions for all actors and also the citizens to know about the city’s policies and plan and should be legally available. Therefore, there should not be any specific purpose to publish some special document and not the others. However, even if there is a selective approach to the publishing them, this shows the purpose of the organisation on what and how documents are presented. In case of this thesis aims and problem, to see if the smart city is a means of branding and marketing, this point is positively important.

In relation to the insufficient details, Bowen (2009) elaborates that as documents are usually provided with some purposes other than research, so they are not based on the research agenda. In the case of this thesis, we use the documents to analysis them based on their own specific purposes. It means that, for example, the comprehensive plan of Malmö is analysed to see what the policies are and how this document develops them.

To complete the data collection, we also conducted interviews as a supplementary method to cover some blurred aspects in documents and if there were a need to gather more data concerning a specific topic, e.g., the way of collaboration in smart city planning and projects. For this, the interviewees are selected