Degree Project in English Studies and Education

15 Credits, Advanced Level“I’ll take it first in English and then in Swedish”

- A Study Regarding Teachers’ Language Use in English Class

”Jag tar det först på engelska och sen på svenska”

- En studie om lärares språkanvändning under engelsklektionen

Livia Berne

Grundlärarexamen med inriktning mot åk 4-6, 240 hp 2018-03-23

Examiner: Shannon Sauro

Supervisor: Malin Reljanovic Glimäng

CULTURE, LANGUAGES AND MEDIA

2

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude towards the participating teachers in this study. Thank you for sharing your knowledge and experiences! I also want to thank my supervisor Malin Reljanovic Glimäng, her comments and insight has helped me to clarify points and refine the text.

3

Abstract

This study sets out to examine the teacher perspectives of the use of Swedish and English during English teaching in year 4. Whether the first language, in this case Swedish, should be included is a much debated questions, and, there is no unanimous answer. On the one hand, scholars promote the sole use of the target language in the classroom and argue that such an approach would result in the students communicating more in English. On the other hand, the first language, in this context Swedish, is seen as a resource which can aid language learning. In addition, there appear to be a gap between this discussion and practice on ground. Therefore, this study aims to examine a few teachers’ beliefs and motivation for their language use. The study is conducted through lesson observations and qualitative interviews with four Swedish primary school teachers who teach English. Results show that two of the four teachers believe that the ‘English Only’ approach is most advantageous. Whereas the other two believe that the learners need translations to support their understanding. Swedish is used in every classroom to a varying degree; however, all the teachers motivate its use with the same reasoning: the students’ low proficiency in English makes it too difficult to use the target language only. Furthermore, the teachers find the need to include the first language in order to reach and support all learners. However, one can question this approach as it does not include the learners whom have other first languages than Swedish, and who are forced to learn English via Swedish. The results imply that teachers may need further education on how to work with Swedish and multilingualism in a conscious and pedagogical way.

4

Table of contents

Introduction ... 5

Purpose and Research Questions ... 7

Theoretical background ... 8

3.1 Terminology ... 8

3.2 How languages are learnt ... 9

3.2.1 The distinction between acquisition and learning ... 9

3.2.2 The role of input in language learning ... 9

3.2.3 Multilingualism as a resource for language development ... 10

3.3 Previous research... 10

3.3.1 English only – a monolingual approach... 11

3.3.2 The L1 as support for learning - Translanguaging... 12

3.4 What approach is advocated in the Syllabus? ... 14

Methodology ... 16

4.1 The Participants ... 16

4.2 Ethical considerations ... 17

4.3 Instruments used for data collection... 18

4.3.1 Observation ... 18

4.3.2 Semi-structured teacher interviews ... 19

4.4 Procedure ... 20

Results and Discussion ... 22

5.1 Teacher Beliefs Regarding Language Use ... 22

5.1.1 The teachers’ beliefs regarding their use of English in the classroom ... 22

5.1.2 The teachers’ beliefs regarding their use of Swedish in the classroom ... 25

5.1.3 Teachers’ motivation for using Swedish... 27

5.2 Teacher perceptions of using the students’ mother tongues as a resource ... 29

5.2.1 Teachers’ view of multilingualism ... 29

5.2.2 The teachers’ beliefs on using the students’ mother tongues in the classroom ... 30

Conclusion ... 32 6.1 Limitations ... 33 6.2 Further research ... 33 References ... 35 Appendix ... 38 8.1 Information to participants ... 38

5

Introduction

This study concerns teacher beliefs regarding the use of language in the English classroom. Within the field of teaching English, there are different approaches to the use of language. On the one hand, the first language (L1), in this context Swedish, is seen as a resource for the development of a new language (Cummins, 2007). On the other hand, scholars assume that a new language is learned best through the explicit use of the target language (TL), which in this context refers to English.Yet another perspective in the debate, is the large number of students who have Swedish as a second language. In multilingual classrooms, which are common in Sweden, there are several languages present and the question is whether the teacher can use other languages as support or if the learners are forced to take the de- tour via Swedish. According to Lundahl (2012), learning English through Swedish, as in the textbook glossary lists, is a direct barrier for students with a lack of knowledge in Swedish.

During my education at Malmö University, the teachers have always promoted an ‘English Only’ approach. As student teachers we learned that the amount of input provided by the teacher is vital for the students’ language development. In my experience, there seems to be a gap between the approach advocated by theorist in second language acquisition (SLA) and practice on the ground. I have noticed this during my teachers’ practicum (VFU). As I do my best to speak English at all times during my lessons, I meet students who seem frustrated and who claim that they “don’t understand anything” and question why I speak English. This tells me that the students are surprised and unfamiliar with the teacher speaking English during class. I have also observed English lessons where the teacher only speaks Swedish. Similarly, a review from Skolinspektionen (2011) describes lessons in which neither the teacher nor the students spoke a single word in English. I wonder what may have caused this discrepancy.

Evidently, the amount of English spoken in the classroom varies enormously. One of the reasons behind the broad spectra may be the openness of the Syllabus (2011a). The Syllabus provides a clear idea of what should be taught and learned, however, it does not tell the teacher how to teach (Lundahl, 2014). By not explicitly taking a stand regarding the use of English during class, teachers around the country make their own interpretations of the Syllabus (2011a). Lundahl (2014) states that “it is an unfortunate oversight that the syllabus for English does not make any mention of the

6

need for a consistent use of English” (p.41). However, the Commentary material (Skolverket, 2011b) states that since mediation has been excluded from the Syllabus, it is possible to conduct teaching entirely in the target language. Mediation refers to the ability to translate and interpret.

There also appear to be two opposing attitudes towards language use in the classroom among researchers in the field. Several scholars argue for the exclusive use of target language (Ellis, 2005., Lundberg, 2016., Edstrom, 2006). Enever (2011) found that in classes where the teacher spoke a lot of English, the students also spoke more English during class. Furthermore, Lundberg (2016) describes the risk with over-using the first language and translating everything into Swedish. If the students know that the instructions will be followed by a Swedish translation, they will rely on the translations. She points out that it is not necessary for the students to understand every single word that is being used during class, but rather that they learn to use other strategies, such as the ability to guess the meaning (ibid.).

However, several scholars question the strict attitude towards English only and argue for the need to revisit and further research the role of the first language in the second language classroom (Cook, 2001., Cummins, 2007., Jingxia, 2010). Both Cook (2001) and Cummins (2007) stress the value of using the first languages as a resource and point out that there are several situations where the L1s may in fact aid and not prevent learning. Similarly, a study by Lee and Macaro (2013) showed that the use of only English to explain grammatical structures was very time-consuming and that students, especially young students, developed a greater vocabulary when the teacher used both first and target language. Of course, this does not mean that the first language is used explicitly nor that the teacher translates everything, as communication in the target language undoubtedly assists second language learning. Stoltz (2009) conclude that it is the teacher who decides when and how the first- and target language is used, and further states that the ability to do so, plays a crucial part in the students’ language development. With this as a backdrop, there is a need to look closer at how some teachers in the field motivate their use of Swedish and English in the classroom.

7

Purpose and Research Questions

The purpose of this study is twofold. Firstly, I aim to gain a deeper understanding of how the teachers use the target- and first language during English class. Secondly, the study seeks to shed light on the teachers’ beliefs regarding their own use of Swedish versus English during class. Thus, the overarching research question in this project is: How do four primary school teachers perceive the use of the target language and the use of the first language during English teaching? More specifically, I will explore the following sub-questions to gain a deeper understanding of teachers’ beliefs:

• How do the interviewed teachers describe their own beliefs and arguments regarding teachers’ use of the target- versus the first language in the English classroom? How do they motivate their beliefs?

• How do the teachers perceive the language use of students with another L1 than Swedish during English class?

8

Theoretical background

In the following chapter I firstly define and explain the use of key terms central to this research. Secondly, I will unpack the theoretical concepts that underpin the study. This is followed by an overview and discussion of where current and significant scholars and theorist stand in the question of target- versus first language use in second language teaching, and specifically English teaching. Finally, I will review and discuss the steering documents in relation to the use of English and Swedish during English class.

3.1 Terminology

As often seen in academia, different authors might use the same concepts in different ways. It is therefore important to define how the terms are used in this degree project. The distinction between second and foreign language depends on how the language functions in a particular country or cultural context (Littlewood, 1984). Since English is considered to be well established in Sweden, it will be referred to as a second language (Littlewood, 1984). Henceforth, second language (abbreviated L2) and target language (abbreviated TL) will be used when referring to the new language that is to be learned, in this case English. First language in this context refers to Swedish. Whereas, mother tongue is used to discuss the students who master and use another language than the majority language Swedish. There is also a need to define the use of the concept

Multilingualism. Källkvist, Gyllstad Sandlund and Sundqvist (2017) write that “English

classrooms in Sweden are by their very nature multilingual spaces as students speak at least one other language” (p.27). However, I believe that such a broad definition implies that the learners in the classroom have knowledge of English. Which in turns, raises the issue of what it means to know a language. How proficient does one have to be to know a language? Kemp (2009) describes that most researchers in the field use the term bilingual for user of two languages, and multilingual when referring to individuals who use three or more languages. However, she also gives examples of definitions which “do not use a numeric scale but make a binary distinction between monolinguals, who know one language, and multilinguals, who know more than one language” (Kemp 2009, p.15). In regard to this, multilingualism will henceforth be used as an umbrella term for bilingual and multilingual and will refer to students who master and uses more than one language.

9

3.2 How languages are learnt

3.2.1 The distinction between acquisition and learning

The distinction between acquisition and learning is usually linked to Krashen (2009) and has had a great influence on teaching English. Krashen (2009) describes language acquisition as a subconscious process where the participants are using the language to communicate in natural and real situations. The assumption is that the learners are unaware of their language development just as children are when they develop their first language. This is also the approach advocated by Krashen (2009) himself, and thus the teachers’ use of the TL plays a crucial part in his hypothesis. According to his theory, the TL should be used as the medium of education, to communicate a message and therefor fulfill an authentic purpose. Language learning, on the other hand, refers to conscious knowledge of language, such as grammar, or rules, which may be more known as formal knowledge. Krashen’s description of this concepts and the difference between them gained a lot of popularity in the 80s, after a long tradition of grammar teaching his approach was focused on natural communication (Lundahl, 2014). Lundahl (2014) explains that many teachers were inspired by Krashan’s ideas since they had “found that many of their learners were better at explaining rules than using the language” (p.148). Tornberg (2009) refers to Kelly (1969) who claims that the grammar-translation method has existed throughout the history of language teaching. As the name reveals, the grammar-translation method lays focus on learning grammatical rules and applying those rules by translating sentences from the first- to the target language (Tornberg, 2009).

3.2.2 The role of input in language learning

According to Krashen (2009), input refers to the language that the students are exposed to. He argues that input can be comprehended in different ways. He further points out that we acquire language only when it “contains structure that is ‘a little beyond’ where we are now” (Krashen 2009, p. 21). Likewise, Lundhal (2014) describes that “comprehensible input means that the language used by the teacher is adapted to the learners’ language level while providing a suitable challenge – in order to develop further, learners need to be exposed to new language” (p.40). Of course, input alone is not sufficient for acquiring a language (Lundahl, 2014., Swain, 2000), but its role cannot be disregarded. Ellis (2005) argues for the need to expose the learners to the target language and state that generally, “the more exposure they receive, the more and the faster they

10

will learn” (p.217). The teachers use of the language obviously play a significant role in the amount of input that the learners are exposed to.

3.2.3 Multilingualism as a resource for language development

Having knowledge of several languages is pointed out as valuable in current literature on language learning (Lundahl, 2014., Lundberg, 2016). Multilingualism is a recourse as it allows the individual to draw from a broad base of language which in turn may promote the development of a new language (Lundahl, 2014). Since different languages may support one another it is of great importance that multilingualism is viewed as a resource. By making several languages visible in the classroom the teacher confirms that such knowledge is positive and gives a sense of pride to students with other mother tongues than the majority language (Lundberg, 2016).

The concept Translanguaging has recently gained a lot of ground in the discussion of second and foreign language acquisition. Translanguaging as a pedagogy is based on two assumptions. First, it takes multilingualism as the norm and suggests that languages functions together rather than viewing language as separate entities. In fact, translanguaging means going beyond the socially constructed boundaries of named languages (Wei, 2018). Likewise, Kemp (2009) points out that numbering languages entails a narrow view of what language is. The second principal for translanguaing is that the teacher allows and encourages the students to use their total language repertoire as a resource for learning (Garcia, 2017). According to Wei (2018) translanguaging is neither to be confused with code-switching nor aimed to replace the term code-switching. Unlike codeswitching, research in translanguaging does not concern or attempt to study the ability to mix and separate languages, but it extends beyond. In accordance with Wei (2018), I will examine the use of a translanguaging pedagogy by looking at the role of Swedish and the students’ mother tongue in English teaching.

3.3 Previous research

There is no unanimous view of how the TL is to be used in second language teaching. The effectiveness of an English only approach is questioned by Källkvist et. al. (2017). They point out that there currently is no research-based answer to that question (Källkvist et. al., 2017). Similarly, Cummins (2007) states that there is limited support for monolingual instruction, that is, the

11

exclusive use of the TL without recourse to students’ L1s. With regard to the ambiguity of the discourse, there is a need to further describe the view according to current research. I therefore divided the following part into two different sections, English only, and the L1 as support for learning.

3.3.1 English only – a monolingual approach

The English only approach partly draws upon Krashen’s theory on the role of comprehensible input as well as his thoughts on how one acquires a language (Ho Lee, 2012). Several theorists in the field have argued for monolingual methods which implies that the target language is to be used exclusively (Ellis, 2005., Lundberg, 2016., Lundahl, 2012., Krashen, 2009). Methods such as

immersion and the Direct method aim for authentic use of language by mimicking the way the L1

is acquired, and using the TL in all situations, both as medium and as target (Turnbull, 2018). Immersion refers to a student being completely surrounded by the target language. An example of this is seen at international schools where several subjects are taught in English and the common language between all students is English. This approach aims to strengthen both languages, creating multilinguals. Whereas, the Direct method viewed the L1 as contaminating to L2 learning and advocated the sole use of the target language without translation (Lundberg, 2016). Using the L2 only became a norm in language teaching and is still relatively established. Of course, there are different reasons for taking this position as well as a broad variation within the field, from ignoring the L1s to forbidding the use of them during class.

One reason for using mainly English in the classroom is described by Lundahl (2012), namely, the large number of students who have Swedish as a second language. Learning English in Swedish, or with support of translation as in the glossary lists, is according to Lundahl (2012), a direct barrier for students with lack of knowledge in Swedish. Cook (2001) agrees that the presence of several L1’s in the classroom would justify the exclusive use of TL. However, Lundahl (2012) also argues for the use of Swedish when for example, providing feedback to the students since the feedback is useless unless understood by the learner.

Yet another reason for TL only is pointed out by Lundberg (2016). She argues that the amount of input provided by the teacher affects the students’ oral output of the TL. This is in line with results

12

from other studies which found that in classes where the teacher spoke a lot of English, the students also spoke more English during class (Crichton, 2009., Stoltz, 2009., Enever, 2011). Lundahl (2014) agrees and state that as the exposure increases the students are encouraged to use the language. Crichton (2009) argues that the teachers way of using the TL “sends a strong implicit message about the teacher’s attitude to the value of speaking the language” (p.19). With that said, a total exclusion of the L1 is nearly impossible when teachers and students share another language (Turnball, 2001., Rabbidge & Chappell, 2014). However, one could question the validity of the correlation between the amount of input and the learning outcome as it may be affected by several surrounding factors.

Nevertheless, there are studies which show that the exclusive use of TL could have negative effects on the students’ emotional relation to learning the new language as well as their identity (Cook, 2001., Hall & Cook, 2012., Littlewood & Yu, 2011., Inbar-Lourie, 2010). For instance, Littlewood and Yu (2011) write that “depriving students completely of this support by immersing them in a strange environment, where they feel disoriented and powerless, has been identified as one possible source of demotivation, especially for students with more limited proficiency” (p. 70).

3.3.2 The L1 as support for learning - Translanguaging

During the 21st century the debate has shifted in perspectives on the view of language use in the classroom. Recently, scholars acknowledge that the use of students’ L1s may in fact aid and not prevent learning (Cummins, 2007., Cook, 2001., Inbar-Lourie, 2010., Lee & Macaro, 2013., Ho Lee, 2012., Littlewood & Yu, 2011., Jingxia, 2010., Hall & Cook, 2012). Although this is in fact not a new insight, but it “is a matter of common experience that the mother tongue plays an important part in learning a foreign language” (Swan 1985, p. 85).

Cummins (2007) addresses this issue with an English only approach in the context of multilingual classrooms just as Lundahl (2012), but from another point of view. He points out that languages are not isolated but consist in relation to one another, which is why the L1s of the students should be used as support (Cummins, 2007). Turnbull (2018) maintains that “L2 learning is maximised when learners have access to all pre-existing language skills, and not making use of both the L1 and L2 in the classroom is a waste of a valuable resource” (p.55). Lundahl (2014) does agree that

13

one can make use of the first language and recognizes the fact that knowledge of different languages can support language development. However, he points out that in many classrooms in Sweden, the teacher speaks more Swedish than English. With that said, using the L1s as support is not equivalent to translation nor does it reduce the significant role of interaction in the TL (Cummins, 2007). Strategies such as comparing grammatical structure and making cross-language connections can be used to scaffold language learning (Cummins, 2007, Littlewood & Yu, 2011., Lee & Macaro, 2013). For instance, a study conducted by Lee and Macaro (2013) shows that the use of only English to explain grammatical structures was very time-consuming and that students, especially young students, developed a greater vocabulary when the teacher used code-switching.

To be brief, code-switching refers to the shift between first- and target language within a sentence or a conversation (Jingxia, 2010). Littlewood and Yu (2011) also claim that the L1 can be used to clarify the meaning of words and that its use makes the development move faster. They refer to studies which “use a 'sandwich technique' for presenting dialogues: each new utterance is

presented in the sequence TL - L1 – TL” (Littlewood & Yu 2011, p.71). The authors point out that such structures can aid understanding and create links between the languages. On one hand, these methods may be referred to as translanguaging. On the other hand, it is important to point out that the learners and the teachers in most of the reviewed studies shared the same L1. In the multilingual classrooms that are common in Sweden today, the teacher may not know the students’ languages, and so the question is if and how the teacher will be able to use the learners different mother tongues for support (Lundahl, 2012).

A number of studies investigate the reasons for using the L1 versus TL in the second and foreign language classroom in different contexts (Edstrom, 2006., Jingxia, 2010., Littlewood & Yu, 2011.,

Lee & Macaro, 2013., Stoltz, 2009., Rabbidge & Chappell, 2014., Inbar-Louri, 2010). As they attempt to learn more of the role of the teachers’ L1 talk, I could distinguish three common reasons

for its use. Namely: when explaining new grammar; to make sure that all learners understand; and for managerial purposes. On the other hand, one might argue that these are opportunities for input and communication in the TL that are lost. Thus, I ask, how do teachers reason and explain their choices? Littlewood and Yu (2011) discuss one of the reasons for the teachers’ use of the L1 in these situations. When reviewing studies, they found that teachers often mentioned the students’ lack of proficiency in English as a factor for not using only English. Yet another reason for using

14

the TL was mention by Cook (2001). She explains that teachers often resort to the L1 when “the cost of the TL is too great”, for instance, when it is too time-consuming (Cook 2001, p. 418).

The monolingual approach has been the norm in language teaching for a long time. It may be a consequence of a tendency among teachers to feel guilty when using the L1 (Hall & Cook, 2012). For instance, Edstrom (2006) writes that she was surprised about the amount of L1 that she used and felt regretful and guilty over the use, however, results from the study conducted by Hall and Cook (2012) reveals that only around one third of the participants confirmed that notion, whereas the majority felt that the use of the first language helped the learners “to express their own identity during lessons” (p.17).

The risk though, is that teachers depend on the L1 and translate everything into Swedish (Lundberg, 2016). She and other scholars describes how the teachers use the L1 without reflecting over the didactic purpose (Lundberg, 2016., Cook, 2001., Stoltz, 2009,. Ellis, 2005). Having text translated into Swedish has little to do with language development according to Lundahl (2014).

In a study conducted by Stoltz (2009), he found that the teachers often asked a question in French and then directly repeated it in Swedish. This structure makes the students listen less actively as they rely on the teacher’s translation (Lundberg, 2016). Furthermore, Lundberg (2016) points out that it is not necessary for the students to understand every single word that is being used during class, but rather that they learn to use other strategies, such as the ability to guess the meaning. This is also seen in the Knowledge requirement for E in year six. It states that the students can

facilitate their understanding of the content of the spoken language and texts, by choosing and applying a strategy for listening (Skolverket 2011b, p.35).

3.4 What approach is advocated in the Syllabus?

Unlike the syllabus for upper secondary school which state that “Teaching should as far as possible be conducted in English” (Skolverket 2011c, p.53), the syllabus for the compulsory school (2011b) makes no such explicit statements. However, Källkvist et al. (2017) maintain that “they provide ideological support for English Only” (p.27). The activities mentioned in the syllabus are divided into three parts: reception, production and interaction. This division draws upon the Common

15

CEFR is not included in the syllabus, namely mediation, which includes the ability to interpret and translate. According to the Commentary material (2011a), the exclusion of mediation makes it possible to conduct the teaching entirely in the target language, which can help students who do not have Swedish as their mother tongue.

The Syllabus provides a clear idea of what should be taught and learned, however, it does not tell the teacher how. Lundahl (2014) describes that “the Swedish educational modal is based on the idea that methodology should not be controlled at the national policy level” (p.39). Furthermore, Lundahl (2014) states that “it is an unfortunate oversight that the syllabus for English does not make any mention of the need for a consistent use of English” (p.42). Based on my interpretation of the Syllabus for English, I believe that it supports the use of English only, or perhaps ‘English mainly’ is a better description. This conclusion is drawn upon two different but related parts in the Syllabus. Firstly, the core content includes “oral and written instructions and descriptions (Skolverket 2011b, p.33). Furthermore, according to the Knowledge requirements for grade E in year 6 the students must show their understanding of the essential content in clearly spoken and simple English by for example, acting on the basis of the message and instructions in the content. If the students are supposed to be able to do this alone they must be given plenty of opportunities to practices this ability. By providing the students with instructions in English, they are given the opportunity to practice their ability to “understand and interpret the content of spoken English” (Skolverket 2011b, p.32).

16

Methodology

The following section describes the methodological considerations for this study. The section starts with a discussion of the ethical considerations. Secondly, I will present the participants as well as the context of the study. Thirdly, an explanation and discussion of the instruments used for data collection is presented. And finally, the section ends with a presentation of the procedure, including the analysis of the collected data.

4.1 The Participants

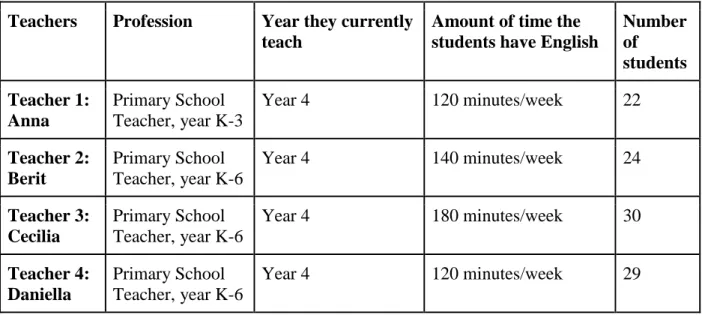

The present study involves four English teachers from four different schools, all of whom agreed to take part in the project voluntarily. The participating teachers (See table 1) were selected for this study since they all teach English in year 4 in the same municipality, although in areas with different socio-economic status.

Table 1: Participants of the study.

Teachers Profession Year they currently teach

Amount of time the students have English

Number of students Teacher 1: Anna Primary School Teacher, year K-3 Year 4 120 minutes/week 22 Teacher 2: Berit Primary School Teacher, year K-6 Year 4 140 minutes/week 24 Teacher 3: Cecilia Primary School Teacher, year K-6 Year 4 180 minutes/week 30 Teacher 4: Daniella Primary School Teacher, year K-6 Year 4 120 minutes/week 29

The first teacher, henceforth referred to as Anna, completed her degree in 2017 and has since then been working at a K-6 school, with approximately 240 students. In her class, which I also visited for observation, about 75% of the students have another mother tongue than Swedish and a couple of the students came to Sweden in first grade. The class consists of 22 students, though during the

17

observation 18 students were present. They have English three times a week, for a total of 120 minutes.

The second teacher, referred to as Berit, has been working as an English teacher in primary school since she completed her degree in 2011. The school serves approximately 320 students in grades K-6. Berit works as a homeroom teacher in fourth grade where she teaches English and Social Science. With the exception of two students, all the students in the class have Swedish as their first language. The class consists of 24 students, whom were all present during the observation. They have English three times a week for a total of 140 minutes.

The third teacher, referred to as Clara, works at an International School with approximately 720 students in grades 4-9. The school differs from the others since the teaching in several subjects is in English, mainly performed by native English-speaking teachers. Clara was educated in the US and got her degree in 2016. Since then she has been working in Sweden (for about three semesters). Clara teaches English and science in year 4 in a class of 30 students. They have English three times a week, for a total of 180 minutes. All students except six have Swedish as their first language, of these, about four students have English as their mother tongue.

The fourth teacher, referred to as Daniella, has been working as an English teacher in primary school since she completed her degree in 2003, with the exception of a couple of years. Her degree lets her teach almost all subjects in years K-6 although, right now she teaches English in years 4,5 and 6. The observed class is a grade 4 with 29 students, however, only 21 students were present during the observation. They have English three times a week, for a total of 120 minutes. Most of the pupils in this school have Swedish as their L1.

4.2 Ethical considerations

In accordance with Vetenskapsrådet (2002), this study follows the four main concepts for conducting research: the information requirement, the consent requirement, the confidentiality requirement and the requirement of usage. Firstly, the information requirement was met. All participants were contacted via e-mail with a letter attached to it (see appendix 1), however, to reduce my impact on the interaction in the classroom, the information about the purpose of the

18

study was limited. This choice gave rise to an ethical consideration. However, Bryman (2004) describes that there is no need for all details concerning the study to be included as it may affect the outcome. Furthermore, I asked for general consent for the observation through the

responsible teacher, who in this context is considered a representative of the participants

(Vetenskapsrådet, 2002). In accordance with the confidentiality requirement, all participants were

anonymous, and the data was handled with great caution. Finally, the requirement of usage, which state that the collected material only be used in this degree project, was meet.

4.3 Instruments used for data collection

This study has a qualitative approach. The intention of a qualitative method is to gain an insight into the actual perception of the interviewee. The reality is described by the participants’ perceptions and interpretations (Bryman 2004). In addition, the study makes use of two types of data. As Alvehus (2013) points out, a study gets higher validity if several different methods are used in the investigation, so called triangulation. The interviews were the main focus since the purpose of the study was to capture and analyse the teachers’ perceptions of the language use. In addition, the observations during class were carried out to deepen my understanding of the communication and language use before the interviews. This, in turn, enabled me to ask questions based on what had been observed, and allowed both me and the interviewee to draw from examples from the observed lesson.

4.3.1 Observation

As mentioned, the observations in this study were used as a complement to deepen and give perspective to the data from the interviews. The data gathered from the observations was

therefore mainly used as a common reference during the interviews but will also be discussed in relation to the results from the interviews. I observed one lesson with each of the participating teachers (a total of four lessons during English class) to investigate the teachers’ language use. Language use in this study refers to what language the teachers choose to use during their lesson, and how it was used. Observation as a method is especially useful when gathering data of

behaviour in the natural environment (Patel & Davidson, 2011). Johansson and Svedner (2006) describe different observation methods. To carry out the observations in this study, the Critical Incident Technique was used, thus, limiting the observations to focus of the questions formulated

19

beforehand (Johansson & Svedne, 2006). Johansson and Svedner (2006) further describe how to precede when using the technique: “One sits and observes the whole class and as soon as one of the events you have defined occurs, you use continuous observations to describe as much of the episode as possible." (Johansson and Svedner, 2006, p.58, my translation). The event or criteria which triggered the observations was: the use of Swedish and the use of strategies when English was not sufficient.

One limitation of the observation as a method is the impact that the researcher may have on the informants. Although I took the role of a non-participating observer, I still must be aware of my impact on the group. For example, one of the participants said that she felt nervous and more conscious during class because of my presence. Patel and Davidson (2011) describe how the informants may alter their behaviour because an observer is present, this is also known as the observer effect.

4.3.2 Semi-structured teacher interviews

The observations were followed by semi-structured interviews. The choice of method was based on the purpose, which was to investigate the teachers’ perceptions of the language use and the

reasons behind the teachers' choice of language (Bryman, 2004). The questions were therefore structured according to three themes, which are (i) personal information and background (ii) beliefs regarding the use of Swedish and English during class (iii) beliefs regarding the use of the students’ different mother tongues. The interviews for this study can be referred to as semi-structured since the questions were formulated beforehand but allowed for openness and

flexibility. For instance, I asked open-ended questions and follow-up questions depending on the answers from the responders. Bryman (2004) puts emphasis on giving the respondent freedom and states that the interviewer does not have to “slavishly follow a schedule, as is done in quantitative research interviewing” (pp.321-323).

However, the risk with the method is that the informant is affected by unconscious signals that the interviewer may send out, and that the responder therefore expresses what he/she believes the researcher wants to hear (Bryman, 2004). With that in mind, I tried to create an open and relaxed environment by stating that I was there to learn more and that there were no correct answers but that the focus was on their beliefs and thoughts regarding their language use.

20

4.4 Procedure

As I searched for participants for this study I contacted twenty different schools in the south of Sweden. Four teachers responded positively and were, together with their class, able to participate in an observation followed by an interview within two weeks.

The observations were undertaken with the teachers’ permission. The time for the observation and interview were scheduled based on the teachers’ request and availability. Approximately 10 minutes before each observed lesson I meet with the teachers to confirm that everything was in order and that the teacher had informed the students of my presence beforehand. We also decided on where I could sit to minimize my effect on the students. During each observation I sat in the back and did not participate in the lesson in any way. I took notes on my computer regarding the teachers use of Swedish and English in class. I also wrote down questions, which were then used during the interview. I systematically observed a lesson in each class followed by an interview. This approach turned out to be successful since it meant that I and the interviewee had a common experience to refer to and discuss. For instance, I was able to ask questions similar to: “I saw that you did this, what are your thoughts on that?”.

As mentioned, the observations were followed by an interview within a period of 3 days, but they were mostly conducted directly after the observed lesson, depending on the teachers’ suggestions. Each interview lasted for approximately 30 minutes. Moreover, the audio was recorded using a standard application. Bryman (2004) highlights that words and phrases might be lost if the researcher only takes notes. This also allowed me not only to make corrections and double check the data, but it also meant that I was able to concentrate and pay attention to the informant. Furthermore, the interviews were carried out in the informants’ respective first language. Since it was important for me that the informant felt comfortable and were able to express themselves freely. For the same reason the informants choose the place where the interview was held.

However, the extent to which the interviews were structured varied in the study. This, depending on the teachers’ availability. For instance, one of the interviews were done in a more casual matter as the teacher had break duty and we walked around the school while interviewing. I am aware that this may have affected the responses from the teacher as well as my ability to focus and ask

21

follow-up questions. This may be referred to what Bryman (2004) calls an ‘unstructured’ interview.

I then moved on to the analysis of the material. All the interviews were recorded and were then transcribed. After that, I read the transcriptions several times and marked findings which seemed interesting in relation the questions. Of course, the things that I found interesting were subjective and were also inspired by the theories and previous knowledge found in the field, as presented earlier. This in turn, might affect the results and might mean that I missed other significant discoveries, however, there was a need to limit and specify the search. I also wrote summarizes of each interview to get a clearer view of its content. The findings were then organized in a table which made similarities and differences between the informants visible. The notes from the observations of each class were then reviewed. The notes only concerned the teachers use of language, which also includes body language. This since, body language is used as a strategy which supports communication. If the teacher used body language to support the English explanation instead of, for instance: using Swedish then I took notes of this. I then compared the finding in the interviews to the observations to find contradictions or confirmations of what the teachers said. Lastly, I connected and compared the finding with the theoretical background and previous research in the field.

22

Results and Discussion

This section presents, describes and discusses the data collected through the semi-structured interviews conducted with the four teachers (Anna, Berit, Cecilia, Daniella). The data is analyzed and presented in relation to the research questions: How do the interviewed teachers describe their own beliefs and arguments regarding teachers’ use of the target- versus the first language in the English classroom? How do they motivate their beliefs? And, how do the teachers perceive the language use of students with another L1 than Swedish during English class? In some cases, quotes are also provided, and these were all transcribed and translated into English by me, with the exception of the quotes by Cecilia, since she spoke English. The results are then related to the previous research and theory presented in the theoretical background as well as the findings from the observations. Thus, this section combines results and discussions, with a systematic organization of presenting results first under each subheading and then providing analysis and discussion in the following paragraph.

5.1 Teacher Beliefs Regarding Language Use

5.1.1 The teachers’ beliefs regarding their use of English in the classroom

All four teachers maintain the importance of speaking English during the lesson, and my

interpretation is that they all believe that it is possible to only use the target language. Two of the teachers (Anna and Cecilia), state that they aim for exclusive TL use in classroom

communication. These statements are well in line with the perception I received during the lessons I observed, except for when texts were translated. Both Anna and Cecilia point out the importance of the students being exposed to the language and compares this to how a child learns his first language. Anna says: “I guess it’s like when a baby develops his first language. I mean, when you learn Swedish, then you firstly understand and then you learn how to talk”. Cecilia expressed similar opinions by saying: "Yes, the best way to learn a language is to be immersed by it, just to be surrounded by it completely". Anna describes that an ‘English Only’ approach was promoted during her teacher training, she also states that she agrees with its benefits to some extent. However, she further explains that depending on the learners it may be difficult.

23

what I was told during my education anyway”. Both Daniella and Berit seem to believe that it is possible to only use the target language as they both state that they speak almost no Swedish in the sixth grade. At the same time, Daniella questions the need for a strict use of English only, saying that: “It is not written in stone, I don’t believe that it must be in one way or the other. One might be a bit more flexible. Maybe I have one student who makes an ‘English only’ approach impossible. Then I’ll have to adapt my teaching accordingly”. Both Daniella and Berit describe that they often use English followed by a translation in Swedish. My interpretation is that Daniella does this to avoid linguistic breakdown as she often mentions the need for all students to be included. She says that: "Everyone must feel calm and confident that they know what to do, but that they also feel comfortable, safe and of course that they enjoy learning English”.

Meanwhile, Berit mentions this structure of communication several times. She refers to it as a method and says, "I'll take it in English and then Swedish, and so I believe that when they've heard the same phrase several times, then eventually it'll stick”.

The first two teachers’ reasoning regarding the way in which a language is developed draw from Krashen’s (2009) distinction between learning and acquiring a language. According to his theory on language acquisition, the learners are unaware of their language development. He compares this process to the way children acquire their first language (Krashen, 2009). Cecilia described her beliefs regarding the need for input and exposure to the language. Likewise, Ellis (2005) argues for the need to expose the learners to the target language and state that generally, “the more exposure they receive, the more and the faster they will learn” (p.217). From the observations, my general experience was that the students in these classes did speak more English than in the other two. This would confirm Lundahl’s (2014) hypothesis: that the teacher’s use of English encourages the learners to also use the language. However, as both teachers still use Swedish somewhat, I do not believe that the approach can be referred to as monolingual. For instance, Cecilia did find the need to provide translations to support the students’ learning. This in turn, may be referred to as translangugaing. Just as Cummins (2007) points out: languages are not separated but exists in relation to one another, which is why the L1s of the students should, in his view, be used as support (Cummins, 2007). Littlewood and Yu (2011) also claim that the L1 can be used to clarify the meaning of words and that its use makes the development move faster. Moreover, Anna’s lesson revolved a great deal around translation of words and text. This in turn, is much like what was seen in the study conducted by Enever (2011). In other words, the students are faced with a lot of

24

translation tasks. When it comes to the communication structure mention by both Daniella and Berit (saying it first in English and then in Swedish), one may make comparisons to the ‘sandwich technique’ mentioned by Littlewood and Yu (2011). As pointed out by the authors, such a structure can aid understanding and create links between the languages. On the other hand, Lundberg (2016) states that a situation where the teacher translates everything can arise very easily. But she further explains that this misguided goodwill in fact deprives the students of opportunities to practice their ability to understand English (Lundberg, 2016). As seen in the study conducted by Stoltz (2009) such translations are often used by the teacher and may at times be a bad habit more than a pedagogical strategy. He also states that such use of language may hinder language development as the students lose valuable input (Stoltz, 2009). However, I must point out that I did not notice any such communication during the observed lessons. In fact, from what I saw, Berit used almost only Swedish. This is consistent with the review from Skolinspektionen (2011) as well as Lundahl (2014) who points out that in many classrooms in Sweden, the teacher speaks more Swedish than English. Of course, since I only observed one lesson, one cannot make any conclusions or general statements about her use of English on other occasions.

Furthermore, the teachers were asked whether they used any strategies when the students did not seem to understand the English instruction. Three of the four teachers reported that they could tell when the students did not understand on their facial expressions: “I notice from the response I get. If they don’t understand, then it shows on their face. Some students ask”, says Berit. Furthermore, they all give examples of strategies that they use: a variety of visual aids, including pictures and drawing on the white board; rephrasing and using a simpler language; using body language or objects in the room; and translating to Swedish. Unlike the other teachers, Anna reflects on the difficulties when a student does not understand neither the Swedish nor the English word or concept:

It is difficult, when I for instance translate something to Swedish because someone doesn’t understand and then when they don’t understand it in Swedish either. What do you do then? If you have the possibility to explain one to one, then you can give picture support, but when leading the whole class, there is just no time. It’s frustrating. I’m sure that there are several students who feel the same way, that they don’t understand the concept in neither Swedish nor English.

25

Although, the teachers all claim that they use several strategies, I noticed a vast difference between the teachers during the lessons I observed. It was clear that the teacher who could not translate to Swedish, Cecilia, used far more body language, rephrased and gave more example to concretise her message. Whereas, the others, from what I saw, often translated or said it in Swedish directly. Based on what Anna said, the students’ may profit from a translanguaging pedagogy, which uses the students’ whole language repertoire (Wei, 2018). To simply translate to Swedish, is perhaps used as the easy way out. Lundberg (2016), argues that such communication hinders language learning as students do not develop strategies to understand a message in English, such as guessing the meaning by looking at the body language, the context or a single word.

5.1.2 The teachers’ beliefs regarding their use of Swedish in the classroom

Three themes were found when looking at the teachers’ beliefs regarding how they use Swedish: when explaining new things like grammar; to maintaining control in the classroom; and when instructing individual students who seem to struggle.

Berit and Daniella both explain that the use of Swedish depends on the situation and on the target of the lesson. When I asked if there are any special occasions when they feel that it is better to use Swedish, they both state that they use Swedish when explaining new grammar: “When I explain new stuff, like grammar. When it's very new and difficult, I'll explain in Swedish", Berit says. Daniella presents a similar reasoning and says that: "Explaining grammar in English to fourth graders may not be worthwhile, as the concepts are difficult for them to grasp in Swedish. It is simply difficult enough to know what a pronoun is in Swedish”.

Explaining grammar is one of the most common reasons for using the L1 according to results in the reviewed studies (Edstrom, 2006., Jingxia, 2010., Littlewood & Yu, 2011., Lee & Macaro, 2013., Stoltz, 2009., Rabbidge & Chappell, 2014., Inbar-Louri, 2010., Hall & Cook, 2012). Daniella states that it is not “worthwhile” to explain grammar in English to fourth graders. Similarly, the results from the study conducted by Lee and Macaro (2013), showed that the use of only English to explain grammatical structures was very time-consuming and that students, especially young students, developed a greater vocabulary when the teacher used code-switching.

26

Yet another reason found is using English for classroom management purposes. As previously mentioned Anna says that she speaks only English in the classroom. However, during the interview she also gives examples of unconscious use of Swedish during class. She seems surprised and a bit ashamed as she explains that: “I realized during the observed lesson that I use Swedish in disciplinary situations. Like, when I said: ’Now you must be quiet’, then all of a sudden, I used Swedish”. She is the only one who reflects and describes such use of Swedish. However, she is not the only one who seems to feel guilty about the use of Swedish. Daniella also admits that she sometimes uses Swedish without reflecting about it. She says: “Sometimes it's just easier, it's not well-thought-out. I guess it can be a pitfall.”

This is in line with the previous research presented which shows that the L1 often is used for classroom management and disciplinary situations (Inbar-Lourie, 2010., Jingxia, 2010). However, Anna is the only teacher who commented on such use of Swedish in this study. With regard to the teachers’ feelings of shame, Hall and Cook (2012) maintain that the norm of only using English in the classroom makes teachers feel guilty when using the L1. This is also in accordance with what Edstrom (2006) writes. She was also surprised and felt regretful about the amount of L1 she used (Edstrom, 2006). However, Hall and Cook (2012) further explain that the majority of the teachers in their study did not report on having such feeling.

Swedish is also used when instructing individual students who seem to struggle. All three Swedish-speaking teachers describe that they often use Swedish when instructing individual students who, according to their experience, have demonstrated that need. Anna gives an example of this when she tells me that: "A student said ‘what should we do? I do not understand anything’, then I'll go over and tell him in Swedish what words are assigned as homework. It is important that he understands what to do and so I want to make sure that he can”. Daniella also describes a similar situation by saying: “For instance, I have an agreement with one student. After an instruction in front of the class, I’ll come to her and explain and discuss what is to be done. First, she tries to tell me what she understood and then I’ll add information if it’s needed”. Surprisingly, even the English-speaking teacher Cecilia gives an example of using Swedish to help a student who was frustrated about writing in English. She explains that she asked a teacher who spoke Swedish to help her reach the student.

27

In my interpretation, these are examples of the teachers using the L1 to avoid communication breakdown. As seen in several studies, the exclusive use of the target language can have negative effects on the students’ identity as well as, their emotional relation to learning the new language (Cook, 2001., Hall & Cook, 2012., Littlewood & Yu, 2011., Inbar-Lourie, 2010). As pointed out by Littlewood and Yu (2011), “depriving students completely of this support by immersing them in a strange environment, where they feel disoriented and powerless, has been identified as one possible source of demotivation, especially for students with more limited proficiency” (p.70). This is also similar to what one teacher in the study conducted by Inbar-Lourie (2010) emphasized. The teacher pointed out the value in using the mother tongue as a resource when introducing a new language because of the emotional attachment the students have to their first language.

5.1.3 Teachers’ motivation for using Swedish

According to the interview responses, one common reason for the use of Swedish had to do with the students’ lack of proficiency in English. All teachers describe the students' language skills as very poor when starting fourth grade. For instance, Daniella says that: "the students could not speak a word of English when they started in the fourth grade". Both Berit and Daniella state this as a reason for using Swedish, pointing to the importance of everyone understanding. Similarly, Cecilia describes the students’ knowledge of English as poor and explains that she uses translations to Swedish in the beginning so that all the students can understand. However, since she does not speak Swedish she uses different methods than the other teachers in this study. She describes how she sometimes asks more advanced students to provide translations. This was also something I noticed during the observation. During the lesson, Cecilia used a PowerPoint in which some words and instructions were translated to Swedish. Anna also refers to her class and tells me that they had little experience of English and that they showed lacking knowledge in tests that she performed. However, unlike the other teachers in this study, she goes on explaining that in spite of this, she stuck to only using the target language. She believes that the students got used to her speaking English and states that they have not yet commented on it.

Just as the results in this study, several other studies reviewed by Littlewood and Yu (2011) found that teachers often mentioned the students’ low proficiency in English as a factor for not using only English. All the teachers seem concerned and point out the importance of everyone

28

participating and understanding. This is in line with the thinking of Jingxia (2010), who emphasizes the advantages of using the first language for an inclusive environment. Yet another example of such reasoning is mentioned by Ho Lee (2012), who states that the most common motive for including the L1 is to make sure that all learners understand. On the other hand, one can question whether the students with a lack of knowledge in Swedish can be considered to be included, as such an approach requires them to learn English via Swedish (Lundahl, 2012). Similarly to Anna’s reasoning about the students getting used to the teacher speaking English, Stoltz (2009) conclude that such an approach could be beneficial for the language development in the long run. Although, he also states that it requires a lot of effort from the teacher (Stoltz, 2009).

Furthermore, it is my interpretation that the teachers view the use of Swedish as a support for learning as they all refer to students making connections between the languages. The teachers point out that when seeing or hearing the difference between Swedish and English the students connect and compare the languages which in turn, leads to learning: “I notice that the students make connections between the languages”, says Berit. Cecilia agrees and states that: “They can hear the difference, the comparisons”. Such strategies or methods could be considered to be translanguaging (Wei, 2018). With that said, using the L1 as support is not equivalent to providing translations for everything (Cummins, 2007). According to Lundberg (2016) the risk is that the learners rely on the translations. The teachers in the study also describe the risks with providing too many translations:

If you have too many then the kids rely on having it translated for them. And so not having it everywhere is nice, and now like half way through the school year I don’t add it a lot. Mostly on new things where the concepts are difficult, like poetry. I don’t translate everything because they would become to reliable and they would just be reading in Swedish and not learning the English language at all so. (Cecilia)

Likewise, Berit says: "Some may think: ‘it's fine because she takes it in Swedish anyway and so I don’t have to worry’". While this is something that all the teachers in this study agree on, the focus on translations are a common feature in the lessons I observed. Two of the lessons revolved around translating a text in the textbook, sentence by sentence. Another teacher also said: “If we translate texts in the book, as we do quite often, then we do direct translations, word for word”. On one

29

hand, several scholars point out that translations and comparisons between languages may enhance the students’ language development (Cook, 2001., Cummins, 2007., Jingxia, 2010). On the other hand, Lundahl (2014) and Lundberg (2016) both state that the activity of translating texts into Swedish has little to do with language development. As seen in a study conducted by Enever (2011), such focus on translations could be the reason for students’ hesitation to speak English during class. In my interpretation, such an approach seems to have similarities with the grammar-translation method (Tornberg, 2009). The risk is that the students get better at translating words than communicating in the language (Lundahl, 2014).

5.2 Teacher perceptions of using the students’ mother tongues

as a resource

5.2.1 Teachers’ view of multilingualism

The participating schools have a varied number of students with other mother tongues than Swedish. In the classroom where Anna works, about 75% have another mother tongue, according to Anna herself. Whereas, the other observed classes have 2-6 students with another language. Anna and Berit express their beliefs regarding the benefits of being multilingual and state that they have noticed that it is easier for the students with more than one language to learn English. They refer to similar examples of seeing this: “In this class, the students who speak most during class are the ones who came to Sweden only a few years ago”, says Anna. Likewise, Berit says: “I notice that the students with more languages dare to speak more in class, yes…Because they are more confident and know that it sounds different and a little weird”. When I ask Daniella about benefits of multilingualism, she too says that it is difficult to generalize:

The more languages you have, the easier it becomes to learn a new one, but it has a lot to do with the size and richness of the student’s vocabulary. Students who have a strong mother tongue may benefit to a great extent. But there are also many who have a limited language in their mother tongue, and then it is not certain that it is an advantage.

Thus, the teachers describe the positive aspects of multilingualism. Just as Lundahl (2014) points out, multilingualism is a recourse as the languages can be used as a support for one another.

30

However, to simply state that the languages are a resource is of course not enough when the teacher on the other hand, does not encourage the students to use that knowledge.

5.2.2 The teachers’ beliefs on using the students’ mother tongues in the classroom

Even though Anna and Berit both described the benefits of multilingualism, this is not something that is actively promoted during the English lessons. When asking Berit whether the students’ mother tongues may be used in the classroom, she says no and further explains that: “I do not think you should mix. That will just confuse them. They’re only in fourth grade and it’s difficult enough already”. Anna, on the other hand, gives examples of students connecting and making comparisons to their mother tongue during class: “Sometimes words are more like their language, for instance, the other day the text we read was about a cockroach, then one student said: that’s almost like in Spanish: cucaracha”. However, when I ask her whether the mother tongues could be used when for instance translating words, she says that she has not thought about it. The only teacher who states that she uses the students’ mother tongues is Daniella. She refers to students who do not speak Swedish well and states that: “Then you’ll have to work with translations to the mother tongue, otherwise it won’t work”.

It is my interpretation that the translations that Daniella is referring to are used when the students do not understand the Swedish instruction, meaning that the learning goes via Swedish. Just as pointed out by Lundahl (2012) this approach is a direct barrier for students with lack of knowledge in Swedish. He also describes that this is one of the reasons for mainly using English (Lundahl, 2012). Daniella seems to agree: “If the student has a moderate level of English then of course, they would benefit from me only speaking English, that would be fantastic! Then all would be equal”.

All the teachers give the same reason for not using or promoting students’ use of their mother tongues during English class. The teachers’ perception is that there simply is no need to, since all the students know Swedish well. However, Cecilia points out that: “If a student only knew their mother tongue then yes, but luckily we don’t have a situation like that. If it were to ever happen then yes, I would provide their mother tongue translations for things”. Likewise, Daniella states that if she had more students with a lack of knowledge in Swedish then she would have to change her teaching approach: “We only have a few students with lacking knowledge in Swedish and so

31

we are able to work one-to-one. Whereas is you have a class where 80% has another mother tongue than Swedish one would have to use other pedagogical tricks”.

As stated by Daniella, the multicultural classrooms require a different pedagogical approach. Cook (2001) points out that several first languages in the classroom would justify an ‘English Only’ approach. On the other hand, translanguaging practices suggest that language development is supported by the first language. However, it also means that the teacher promotes and includes the students’ languages in an active way (Wei, 2018). Such an approach was not seen in any of the classrooms observations. Berit seems worried about the students getting confused if more languages would be included in the teaching. However, according to García (2017), all students would benefit from a translanguaing approach. By including and making the languages visible in class the multilingual students would be accepted and the monolingual students would learn the value of having several languages (Gracía, 2017., Lundberg, 2016).

32

Conclusion

In this section, a summary of the results based on the research questions will firstly be presented. Secondly, implications for teaching practice will be discussed. Thirdly, the limitations of the study will be presented. Finally, suggestions for future research will be given.

This paper describes four teachers’ beliefs regarding their language use in the English classroom. The teachers’ reasoning regarding their use of Swedish and English differ somewhat between the participants, however, some themes emerge from the interviews. Tu sum up, two of the four teachers believe that the ‘English Only’ approach is most advantageous. However, the other two reveal that they believe that the learners need translations to support their understanding. The main themes found for using Swedish during class is: when explaining new grammar, to manage the class and to support individual students with lacking confidence or understanding in English. In addition, the findings reveal that Swedish at times is used without reflection on the didactic purposes. Furthermore, the teachers all refer to their learners’ knowledge of English as week or non-existing when starting fourth grade, and this is also the main motivation for using Swedish. On the other hand, they all believe that the learners’ knowledge of Swedish is well developed. This in turn, is the main reason given for not using the students’ first languages during class. Despite the fact that all four teachers view multilingualism as positive and beneficial for learning a new language, this is not used as a resource in class.

What stands out as interesting to me is the comparison between Anna, who teaches a class where about 75% have another mother tongue than Swedish, and Daniella, who works at a school were there only are a few students with another language background than Swedish. Daniella describes that if she had more students with another mother tongue than Swedish she would have to use other pedagogical methods since it would not be possible to support students one- to one, as she does now. However, as seen in Anna’s class, such pedagogical tricks are not used. In fact, Anna describes the frustration about not being able to support students one- to one. She also believes that there are several students’ who do not understand the instruction, neither in English nor in Swedish. Yet, it seems as if she has limited strategies for how to handle these situations. To refer to what Daniella said, Anna did not use other pedagogical ‘tricks’. Likewise, Berit said that she thought it was confusing to the students to mix the languages. Thus, one might assume that teachers