J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O LJÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY

C o n ta g i o n i n t h e N o r d i c

B a n k i n g c r i s i s

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Olli Kannas from statistics Finland who provided us with HEX (general) share index and Joakim Fredriksson from NASDAQ OMXS30 Stockholm who helped us with the Swedish stock market index.

A b s t r a c t

This paper analysis’s whether there was contagion during the Nordic banking crisis. It draws a relationship between the exchange rate and stock returns and uses the interest rate to control for common shock during the crisis. Several aspects of the Nordic crisis are being discussed and presented as well as background information concerning the oc-currences during the period of turmoil. Further it provides a survey of theoretical litera-ture on previous studies on financial contagion. The empirical analysis employs a least squares model in testing for contagion, computing the residuals and testing for the coef-ficient correlations. Testing through the least squares revealed that though contagion ex-isted, it was not through the exchange rate but through the stock market returns. The fixed exchange rate burden was felt by the interest rate and thus, contagion occurred through the interest rate. Contagion appears to spread more easily to countries, which are closely tied in the pattern of stock trading. All the Nordic countries (Sweden, Finland, Denmark and Norway) except Denmark suffered from the banking crisis, this because its macroeconomic surprises were smaller and an initial light debt burden. In the econometric testing we did not include this macroeconomic surprise.

Key words: foreign exchange, common shocks, correlation coefficient,contagion, Nordic Crisis

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 Purpose and outline……… ... 2

1.2 Background ... 2

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 5

2.

1 Definition of contagion……… ... 5

2.2 Pure contagion ... 5

2.3 Fundamental based contagion ... 6

2.3.1 Financial linkages ... 6

2.3.2 Trade linkages and devaluation……… ... 7

2.3.3 Common shocks………...……….………7

2.3 Prevention of contagion ... 7

3 NORDIC COUNTRIES AND CONTAGION ... ….9

3.1

Previous Research ... 9

3.2

Interest Rate ... 10

3.3

Exchange Rate... 12

3.4

Stock Returns ... 13

3.5 ERM ... …..14

4 THE MODEL OF REGRESSION ANALYSIS ... …15

4.1

DATA ... 15

4.2

Empirical examination of contagion ... 15

4.3 Statistical testing ... 18

5 SUMMARY OF EMPIRICAL RESULTS ... 19

6 CONCLUSION ... 22

Equations

Equation 1………15 Equation 2………15 Equation 3………17Figures

Figure 1………10 Figure 2………11 Figure 3………12Tables

Table 1……….17 Table 2……….18 Table 3..……….………….….19 Table 4..………..20 Table 5..………..20Appendix

Appendix 1………..26That the Nordic region is closely linked together in many aspects is a statement that would not be contested by many. In economics, the mutual dependence of nations is generally acknowledged, but consequences of this dependence can be that financial fra-gility in one economy easily spreads to others. As the Nordic countries1 experienced a crisis in the early 1990’s, did this mutual dependence imply that the crisis worsened and spread? The experiences of the last decades suggest that this might very well be the true. The wave of globalization has implied a massive increase in the degree of integration between nations. This integration, from an economic perspective, saw the financial lib-eralisation of many national economies. During the 1980’s and 1990’s there was a rapid increase in deregulatory measures taken by many nations. These where not concentrated to specific parts of the globe, but rather, we saw similar movements in Latin America, Europe and Asia.

This financial liberalisation also followed similar patterns in economic movements, as the economic booms following the increased competitiveness of a more open market were followed by economic downturns and crises in many regions of the world. It was the crises of Latin America and even more so Asia in 1997, which gave emphasis to a phenomenon referred to as contagion. There is not a common consensus regarding the definition of contagion, thus the different definitions will be further discussed later in this article. However a broad definition of contagion can be found in;

“Contagion occurs when a shock to one or a group of markets, countries, or Institutions spread to other markets, or countries, or institutions” (Pritsker, Matt 2000 pg.3).

Many theorists link contagion to financial liberalisation, this link refers to a significant increase in the share of foreign assets with respect to GDP. Contagion, as already men-tioned, is subject to many definitions and is more specifically concerned with the inter-national spillovers from asset price and currency movements (Milesi-Ferretti and Lane 2005). Contagion has not been of great interest to economist until the second half of the 1990s when financial crises started spreading across emerging markets, affecting na-tions with apparently good fundamentals, and whose policies only a few months earlier had been praised by market analysts and the multilateral institutions.2

These are occurrences and traits, which are all applicable to the Nordic countries and the crisis of the early 1990’s. Many theorists have argued that it was these deregulatory measures, also enacted by the Nordic countries that caused a wide spread crisis. Further, the close link between this group of nations supplies not only many basic features of the possible existence of contagion. But already observed co-movements are discussed by much of the literature examining the Nordic crisis.

It is with such indicators that this thesis deals with the testing for contagion during the Nordic crisis, supplying not only a specific empirical analysis, but also dealing with opinions on the cause of the crisis as well as the theory of contagion. This will provide further explanations to the dependency of nations in an integrated economic environ-ment and the cause of the Nordic crisis.

Refers to Norway, Sweden and Finland any other definition will be noted 2 See the discussion of Masson (1998)

1.1 Purpose and Outline

The purpose of this thesis is to analyse the effects of the Nordic banking crisis on the Nordic countries and to test whether there was contagious effects during the crisis. We testing for contagion using the Ordinary least squares and the GARCH model.

The paper is outlined such that, Section 1 is the introductory section providing a back-ground for the thesis. Section 2 provides the theoretical framework for contagion. Sec-tion 3 deals with emphasising important aspects of the crisis that relate to contagion theory. Section 4 provides the empirical testing. Section 5 analyses and discusses the empirical results. Section 6 concludes the thesis. Following are references and Appen-dixs 1.

1.2 Background

The Nordic crisis, although not subject to great international debate, was for the affected countries greater and more persistent than any period of economic downturn for many decades. The comparison between the Nordic case and that of the 1997 Asian crisis is not comparable in magnitude, but rather, cause and effect. Most analysts state that the crisis lasted between the years 1990 – 1994 and that the countries with significant tur-moil where Norway, Sweden and Finland.

In the 1980’s there was considerable development in financial markets, which led the Nordic countries to enact several deregulatory measures throughout the later half of the 1980’s. This deregulation implied a major change in the market structure of all three Nordic countries. Prior to deregulation, these economies had enacted heavy restrictions on its banking sector and financial markets.

The restrictive economic policies of the Nordic countries, especially within the banking and financial sector, relied on the principals of keeping a stable and low interest rate and a stabilized banking system. The low interest rate, which was one of the major goals, created an environment where government intervention was relied upon in order to maintain control over lending. This as there was great excess demand for lending due to the low interest rate. Banking profits remained stable as banks where to a large extent protected from domestic as well as foreign competition (Drees and Pazarbasioglu, 1995).

The deregulatory measures taken by the Nordic countries where initiated in Norway 1984 and continued through out the 1980’s in all of the three countries. The major im-plications of these deregulatory measures were increased competition, and with this, a major expansion in lending and risk taking. Not only was the deregulatory measures implemented within a few years, but also implied a shock to the previously heavily regulated system (Drees and Pazarbasioglu, 1995). 3

The similarities of the deregulatory processes and its implications for Norway, Sweden and Finland are not only noted by theorists but also similar when described in an inde-pendent context. Michalesen, Ongena and Smith (2003) mention that, the deregulation of 1984 implied that authorities relaxed reserve requirements,opened Norway to

eign- as well as newly established Norwegian bank competition and allowed for subor-dinate debt to be counted as capital. In the following two years competition was further intensified as foreign banks were permitted to open branches in Norway. As a response to the newly deregulated environment banks aggressively expanded lending. Further Englund (1999) notes that, the major driving force behind the Swedish deregulation was probably the rapid development of financial markets. Swedish interest ceilings were lifted in the spring of 1985. International investments were subject to regulation until currency regulations were lifted in 1989. Interest rates remained high in order to stimu-late private borrowing in foreign currency. This meant that the private sector took on a high level of exchange-rate risk. Honkapohja (1999) describes that this higher risk tak-ing implied that private sector indebtedness went up and real estate and asset prices soared.

The newly deregulated environment saw a large increase in the operations of financial companies as the economic environment became increasingly competitive. This in-crease implied a direct link between financial companies and the savings- and union banks. High-risk loans exercised by the financial companies where indirectly funded by banks. This was a result of the rapid expansion of financial companies, which had been funded through bank loans (Drees and Pazarbasioglu, 1995). When discussing the lend-ing boom Drees and Pazarbasioglu state that “Overall, the vulnerability of banks to credit losses increased in all three countries since no additional operating profits were being generated during the lending boom to compensate for the greater lending risks…”(Drees and Pazarbasioglu, 1995 p. 22)

The rapid Norwegian credit expansion saw an end in 1987 as bank loan losses had be-gun to accumulate. During 1986, loans to cyclically sensitive firms also came into jeop-ardy as the oil-dependent Norwegian economy experienced a sharp decline in asset val-ues, this due to the price decrease of North Sea Brent Blend crude oil from 27$ to 14.50$ a barrel. Between the years 1986-89 the annual number of Norwegian bankrupt-cies increased from 1,426 to 4,536 establishments. The bankrupt firms were mostly unlisted and small, operating in real estate, transport, construction, retail store, fishing and hotel and restaurant industries. Following these events real bank loan growth de-creased to 3.6% in 1988 and 2.8% in 1989. Also, commercial loan losses, measured as a percentage of total bank assets, increased from 0.47% in 1986 to 1.60% in 1989. Sunnmørsbanken was the first Norwegian bank to announce its insolvency. Between 1988-89 three other small commercial banks and four savings banks made similar an-nouncements (Ongena et al 2003). This was the first sign of the shift from a general fi-nancial crisis to a banking crisis for all three Nordic countries.

During the years 1990-1992 the crisis had not only severely affected the Norwegian banking system but also spread to Sweden and Finland. In Norway, 85% of commercial bank assets were under government control and only eight commercial banks remained in operation. Other major financial institutions, such as savings banks, finance compa-nies and mortgage compacompa-nies also experienced record losses during this period. The impact of the crisis was long lived, as Norwegian banks did not return to their pre-crisis stock prices until the summer of 1997 (Ongena et al 2003).

During this period the Swedish banking sector saw severe financial difficulties for many of its largest actors. Large banks such as Första Sparbanken, Nordbanken and Göta Bank went bankrupt. While the two largest banks, SE-Banken and Handelsbanken ex-perienced an 80 percent decrease in their stock quotations. The bankruptcy of these three large banks was due to excessive losses, which were directly linked to bad loans to

real estate and share purchasing. The extensive crisis experienced by the financial - and banking sector resulted in the disappearance of 200 out of the 300 financial companies from the market, and an estimated loss for the period 1990 – 1993 of 200 billion SEK. Although the financial crisis has been observed to have culminated in 1993, unemploy-ment rates remained high. There was also high risk of credit loss on private loans. The macroeconomic effects of the financial crisis were evident as real GDP decreased by 6 % from 1991 – 1993. Unemployment figures rose from 1.1 % in June of 1990 to 9 % in 1993 (Lybeck, 1994).

In Finland the boom took an abrupt end in 1990 when GDP growth declined from +5.4% to –6.5% during the period 1989-1990. This implied that private investment as well as consumption and net exports of goods and services declined sharply. This de-cline continued, although not as substantial, through out 1992 and 1993. The economic downturn came to an end in late 1993. Most difficulties dealt with high unemployment rates, which continued to increase through out 1994 affecting one-fifth of the labour force. Five years later unemployment was still at high levels, amounting to 11% (Hon-kapohja, 1999).

In Norway, Sweden and Finland many insolvent banks where backed by some form of government funding in order to stabilize the banking systems. Further, exchange rate and inflationary pressure sought the abandonment of the fixed exchange rate regimes for all three Nordic countries. Additionally it is noted that monetary and fiscal policies had weak counter-cyclical effects due to the fixed exchange rate regimes in these countries. For example, Englund (1990) clearly states that the decision to let the Krona float aided the decrease of the interest rate.

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This section provides definitions of contagion and the different types of contagion, which are pure contagion and fundamental based contagion. It provides the main idea on what this thesis is about, the main feature of this section is that is makes you under-stand how contagion can exit and what factors are responsible for it also explains how contagion can be prevented.

2.1 Definition of Contagion

In recent times, there has been extensive and comprehensible literature about contagion but little agreement of the results has been made. The main problem lies in that fact that most economists have not yet agreed upon a general definition for contagion. The first systematic theoretical treatment of this question was carried out by Gerlach and Smets (1995). They were motivated by the links between the fall of the Finnish Markka in 1992 and a subsequent attack on the Swedish Krona, the paper considered two countries linked together by trade in merchandise and financial assets. In their model, a successful attack on one exchange rate would lead to real depreciation, which enhances the compe-titiveness of the country’s export. This would produce a trade deficit in the second country, a gradual decline in the international reserves of its central bank, and ultimately an attack on its currency.

Contagion refers to the spread of market disturbances, mostly on the downside, from one country to another (Claessens and Forbes 2001). It is observed through co-movements in exchange rates, stock prices, sovereign spreads and capital flow. Conta-gion can arise from the overlapping claims that different reConta-gions or sectors of the bank-ing system have on one and another. When a region suffers a bankbank-ing crisis, other re-gions suffer a loss because their claims on the troubled region fall in value. If the spill over effect is strong enough, it can cause a crisis in the adjacent regions (Allen and Gale 2007).

2.2. Pure contagion

A type of contagion that occurs when the transmission of a financial crisis cannot be linked to observed changes in macroeconomic or other fundamentals. It results solely from the behaviour of investors and other financial agents (Claessens, Dornbusch and Park 2001). Pure contagion thus refers to a crisis which is triggered by a crisis else-where. But, which cannot be explained by changes in fundamentals or any sort of me-chanical spillover. Rather it is possibly caused by shifts in market sentiments or changes in interpretation, given the existing information. Market spillovers results from real market inter-linkages between the affected countries, for instance; spillovers through trade links have been emphasized in the discussion about contagion (see Ei-chengreen, Rose, and Wyplosz (1996) and Glick and Rose (1999)).

Contagion takes place when there is co-movement that cannot be explained by funda-mentals. Take as an example, a crisis in one country may lead investors to withdraw their investments from other markets, without distinguishing between differences in their economic fundamentals. Withdrawals of this type are individually rational. Other kind of rational withdrawal includes an increase in the export prices or uncertainty in the political system of government.

Asides rational withdrawal there is also irrational withdrawal. These are often the result of herding behaviour among investors. Investors withdraw their capital because others are doing the same.

2.3 Fundamental based contagion

Fundamental based contagion arises due to the spillover that results from the normal in-terdependence among market economies. Inin-terdependence implies that shocks whether it is of global or local nature, are transmitted across countries through real and financial linkages (Calvo and Reinhart 1996). Fundamental based contagion can be divided into financial linakages,trade linkages and competitive devaluations and finally common shocks.

2.3.1 Financial linkages

According to Claessens et al (2001), economic integration of an individual country into a world market, will typically increase both trade and financial links. In their article, Caramazza, Ricci and Salgado (2004), argued that contagion arises when two countries have the same lender. In essence if country X suffers from a financial crisis, country Y would be affected if the creditor would need to change its portfolio. Spillovers can also emerge through financial market inter-linkages, which result to shifts in investors’ port-folios.4 Common bank lending channels belong to this category. There are several mechanisms for which banking centres can cause cross-border spillovers. Rijckeghem and Weber (1999) argued that losses in one country could lead to selling of assets in other countries, in an attempt to restore their capital-adequacy ratios. Calvo (1999) stated that, similar mechanism is at work if investors upon receiving a margin call based on the decline in price in one asset, decide to sell assets in other countries. Most impor-tantly, if banks are faced with losses on their securities portfolio or have a rise in non-performing loans in one country, they are likely to try to reduce their overall value at risk (Rijckeghem and Weber 1999). Therefore risk management techniques may then dictate a decrease in exposure, in the riskiest markets or in credit lines in historically correlated markets (Folkerts-Landau and Garber, 1998).5

2.3.2 Trade linkages and competitive devaluations

Glick and Rose (1999) and Eichengreen, Rose and Wyplosz (1996) argued that coun-tries with trade links easily transfer crisis to each other. Whenever a financial crisis cause currency depreciation in one country its trading partners could experience de-clines in asset prices, outflow of capital or speculative attacks. If a country experiences

4Dornbusch, Park and Claessens (1999) provides reference to this literature.

5

A number of further reasons for financial spillovers have been discussed in the literature. To the extent thatinvestors allocate fixed proportions of their assets to (individual) emerging markets, changes in the weight given to the emerging market asset class as a whole affect all countries equally (Buckberg, 1996). Asymmetricinformation can amplify the effects of portfolio rebalancing (Kodres and Pritsker, 1999). Lack of liquidity is a further reason why a crisis in one market may lead financial intermediaries to liqui-date other emerging market assets (Goldfajn and Valdes, 1997). Finally, regulations involving ratings, such as regulations which disallow holdings of non-investment grade securities, or link capital require-ments to them, may also play a role. To the extent that downgrades are implemented more frequently in emerging markets after a crisis, this may well add to sell dynamics in a crisis.

a financial crisis with a devalued currency as a result, investors would withdraw their investment from the country as well as it trading partners. The reason being that inves-tors would foresee a decline in export to the crisis country, causing deterioration in the trade balances.

Another channel in this category is competitive devaluations. When a crisis country de-valuates its currency it reduces the export competitiveness of other countries that com-pete in third markets (Claessens, Dornbusch and Park 2001). Gerlach and Smets (1994) argued that if a country devaluates its currency it will experience a temporary increase in competitiveness due to the fact that prices will be sticky. This means that for some time, country B will have a harder time competing with country A and as a result miss out on ex-port possibilities since it now is more lucrative to trade with country A. If this situation oc-curs, country B may also be the target of the next currency crisis as their growth decreases. This is especially the case if country B’s exchange rate is not floating freely since it is thus forced to keep the predetermined exchange rate level. According to Corsetti et al.(1998b), a game of competitive devaluation can cause larger currency depreciation than is required by the initial deterioration in fundamentals.

2.3.3 Common shocks

A concurrent occurrence of financial crisis may stem from the relations of a common shock with macroeconomic fundamentals. A global shock in industrial countries can trigger a large capital outflow from an emerging market. A situation of common shocks is seen in changes of the US interest rate, which has been linked to movements in capi-tal flows to Latin America (Calvin and Reinhart, 1996 and Chuhan et al., 1998). A large appreciation of the U.S dollar during 1995-97 and Japan’s weak growth during the 1990’s may have been a contributing factor to the weakening of the external sector dur-ing the Asian crisis (Caramazza, Ricci and Salgado, 2004). Common shock can lead to increased co-movements in asset prices or capital flows. Interest rates are usually used to test for common shock during a crisis.

2.4 Prevention of contagion

The key question is how a country can curb or prevent contagion. Caramazza, Ricci and Salgado (2004) argue that financially integrated countries are more vulnerable to conta-gion because of the ties between them. A way of preventing financial integration is through inserting capital controls; such as taxes and barriers of different kinds, policy such as this would remove the financial ties and thus the risk of a contagious crisis. Other policies, which are aimed at limiting contagion are; limit exchange rate flexibility and avoid short-term debt. Capital controls can curb contagion if the financial links are important transmission channels.

Contagion can be stopped if there is restriction regarding bank lending. Mishkin (2000) pointed out that the financial liberalisation process in Asia caused bank lending to in-crease dramatically. When there are no restrictions like interest rate ceilings and thus quality of borrowers’ declines, credit extension will grow at a higher speed than GDP implying high-risk taking.

Edwards (1999) evaluates if capital controls in Chile were useful in avoiding contagion. He measures them as correlation between domestic and Asian interest rates, while con-trolling for domestic devaluation and exchange rates versus the US. He concludes that control on capital inflows should have been able to protect Chile from relatively small

shocks. Though it might not be able to prevent contagion arising from large external shocks.

Exchange rate flexibility can be used to reduce contagion by avoiding some of the over-valuation scenarios that begin with and limit the scope of speculation. There are usually speculative attacks when the exchange rate is fixed or floated by the central bank. This causes a situation where creditors start demanding their money back. Despite that the capital has disappeared from the country, the central bank still has to repay money using its foreign exchange reserves at an already agreed upon exchange rate. When this oc-curs, other investors begin to understand that capital withdrawal is made from a country. Following this, speculations arise on how long the central bank can keep the local cur-rency’s peg. Morris and Song Shin (1998) claimed that both the European exchange rate in 1992 and the Mexican peso in 1995 were victims of speculation, which certainly con-tributed to the preceding crisis. Gregorio and Valdes (2001) discovered that in measur-ing contagion with a real depreciation variable, they found that exchange rate flexibility increases contagion. Their result however, was only marginally significant, fewer than two weighting matrices.

Leitner (2005) used a model conducted by Allen and Gale (2000) which showed that fi-nancial linkages between banks can help stop contagion. His model confirms that a strong bank can help another bank that is close to bankruptcy, by cross holding of de-posits. The idea is to insure against individual liquidity shocks. When banks construct a common buffer, they get the incentive to help others in need of capital and thereby stop the stimulant needed for contagion. The principle behind this is if other banks do not help the bank close to bankruptcy, they may very well be the next victims.

3 NORDIC COUNTRIES AND CONTAGION

This section provides some further notifications and occurrences, which emphasizes the link between certain aspects of the Nordic crisis and contagion. The section provides the main ideas by other theorists on probable cause of the crisis and some of the events of the crisis, which have been directly discussed when theorising contagion. The aim of the section is to highlight features of the crisis that further strengthens the empirical analy-sis carried out in section 4. It should also be noted that some of the aspects discussed will not be included when testing for contagion. Rather it will serve as an extended ba-sis on which one will better understand the evidence for contagion in the Nordic criba-sis, as well as features which are beyond the scope of this thesis.

3.1 Previous research

Much of the research presented includes the mentioning of factors, which can be related to the definition and theory of contagion. The conclusions reached concerning causes and effects of the Nordic crisis also link very closely to the literature put forward on contagion. Jonung et al (1996) mentioned that financial deregulation in all Nordic coun-tries implied increased financial and foreign integration. Thus, the disinflationary poli-cies and international interest rate developments contributed to an interest rate shock. Similar conclusions are also presented by other articles, which will be discussed later in this section. The interest rate shock applies to the already mentioned section 2.2.2.3 Common shock, which discusses the impact of sharp interest rates movements. This top-ic is further addressed when talking about the ERM6 impact on Nordic interest rates and the inter-linkages between Nordic interest rates. These ideas are the most prominent when discussing the reasons for the Nordic countries extensive crises. Not only, is there a wide consensus that these factors had some, if not major, cause on the Nordic devel-opment during this period. But it also deals with variables, which have been present for most definitions of and theorizing on contagion.

Much of the work put forward by Englund on the Swedish experience, and by Steigum, explains how the Nordic countries experienced difficulties in handling a fixed exchange rate with, prior to the crisis, booming economies. There is also great emphasis on the increased inter-linkage between financial markets as deregulation was implemented. All of these factors are mentioned as bases for contagion by for example Calvo and Rein-hart (1996).

The Swedish interest rate rose further according to Englund due to three major factors, international interest rate increases due to the German reunification, an increased re-strictive fiscal policy due to inflation targeting and a tax reform increasing the post tax interest rate return (Englund, 1999).

The European Exchange rate Mechanism included as member countries, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom

Similar notations are made by Steigum saying that during the 1980’s, pressure of finan-cial market deregulation increased as finanfinan-cial market operations became more effi-cient. During this period international financial integration increased and around the mid 1980’s the Norwegian economy experienced rapid deregulatory measures. Following this, there was increased pressure on the Norwegian Krona causing its devaluation in May of 1986, accompanied by raised interest rates in an attempt to defend the currency (Steigum, 2003). Such close linkages are explicitly discussed in Allen and Gale (2007) and is noted also when Englund describes the Swedish deregulatory process.

Further turmoil concerning interest rates and exchange rate speculation are also de-scribed by both Steigum (2003) and Englund (1999), factors that are mentioned in the work on contagion by Claessans and Forbes (2001).

Englund states that as the currency crisis lagged the banking crisis by one year there is no direct link between the two occurrences. However, he states that there is an indirect link between Sweden’s high interest rates in defending the exchange rate and the dee-pening of the banking crisis (Englund, 1999). Such movements have already been men-tioned and observed in the figures above. Further, Gerlach and Smets (1994) explicitly discuss such a scenario.

Englund further notices that the increased volume in international financial services and transactions increased Sweden’s international dependence. Also noted is the Swedish economy’s higher interest rate average, which is weighted to about 4% higher than that of the international average (Englund, 1990).

Englund also writes that, high inflation and continued real appreciation was the major factor for the volatility of the Swedish exchange rate. This forced a hiking of the interest rate as speculative pressure increased. Englund recognizes two major reasons for this situation, the 1991 tax reform increasing post tax interest rate return and the high inter-national interest rates of the ERM crisis. These pressures were according to Englund (1999) so strong that Sweden experienced a real interest rate shock. Also acknowledg-ing that the fixed exchange rate policy may have contributed to these effects, rather than if it hade been left to float at an earlier stage. The theorizing behind the Nordic crisis as well as the events surrounding it coincides with much of the research put forward on contagion. Already mentioned references have provided basis for the interest rate and exchange rate analysis of contagion. These are also the factors, which seem to have the most coinciding opinions on the major factors contributing to the Nordic crisis by re-searchers. See also section 2.2.2 Fundamental based contagion, which emphasizes fi-nancial linkages.

3.2 Interest rates

For the pre-crisis period Englund (1999) states that, Sweden had for a long period of time experienced higher inflation rates then than many other countries. As there was a continuous real appreciation of the exchange rate, six devaluations followed after 1973. The 16% devaluation in 1982 left Sweden with a temporarily undervalued currency. Real appreciation continued and devaluation expectations were reflected in higher inter-est rates. Lying above the international average by 1-2.5% since the second world war, the difference in interest rates rose by as much as 5-6% under periods of currency spec-ulation, for example in the year 1985. This higher average is clearly displayed in Figure

evi-dence and support that the Swedish economy was overheated. After the devaluation car-ried out in 1982 the Swedish exchange rate had experienced a real appreciation of 15%. The only measures taken to counterbalance this trend were occasional rises of the inter-est rate (Englund, 1999).

As the Swedish banking crisis coincided with the exchange rate mechanism,(ERM) cri-sis in 1992, Sweden, with its unstable currency of high inflation and devaluations, raised its interest rates further to 16% by august 1992. As Swedish banks were heavily dependent on international market access, government measures where taken in order to provide liquidity. Overnight interest rates were continuously adjusted upward reaching levels of 500% in September of 1992. The rise in interest rate is evident when looking at the year 1992 in the above mentioned figureNorway had similar patterns and raised the after tax interest rate from 0% in 1987 to 7% in 1992 (Steigum, 2003).As explanation for the economic instability of the Norwegian economy Steigum emphasizes two major causes, pro-cyclical monetary policy and the fixed exchange rate policy. This according to Steigum (2003) made Norway vulnerable to credit supply shocks and external inter-est rate shocks.

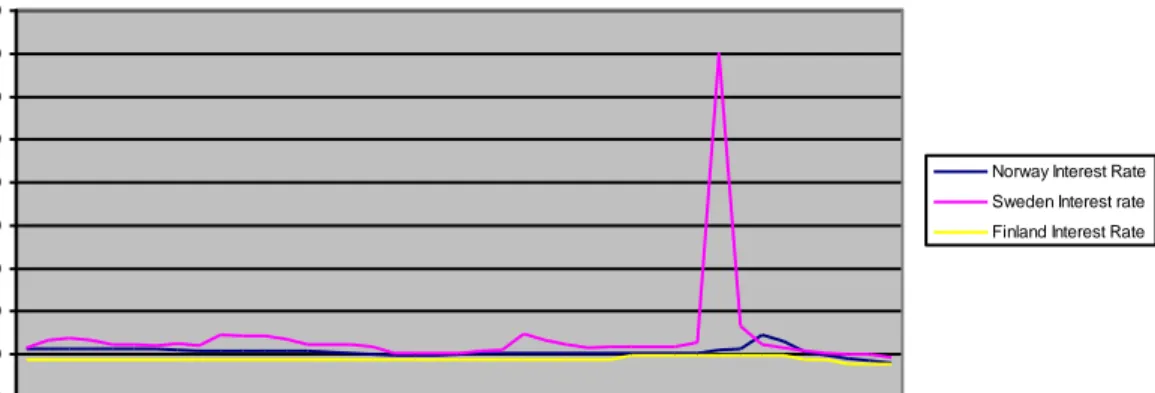

Figure 1 Nordic Countries Interest Rates Jan1990 - May 1993 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 1990 Jan 1990 Mar 1990 May 1990 jul 1990 Sep 1990 Nov 1991 Jan 1991 Mar 1991 May 1991 Jul 1991 Sep 1991 Nov 1992 Jan 1992 Mar 1992 May 1992 Jul 1992 Sep 1992 Nov 1993 Jan 1993 Mar 1993 May Year/Month I n te rs t R a te

Norway Interest Rate Sweden Interest rate Finland Interest Rate

(Figure 1interest rate calculated using data from the Nordic Central Bank)

In the figure we see some evidence of contagion as interest rate hikes and shocks follow the Nordic countries, as the values seem to display some common features concerning interest rate values. The most important features of the interest rate movements are that they coincide very closely to the periods of exchange rate pressure. Specifically impor-tant to note is the period for the year 1992. This is in coherence with the theory put for-ward emphasizing the movements of interest rates due to currency speculation, specifi-cally concerning a situation of fixed exchange rates as in the Nordic case. Thus it is also expected that any evidence of contagion will be reflected in the interest rates. The

above-mentioned figure seems to support these ideas. It can also be seen that interest rates decreased after the floating of the Nordic currencies.

3.3 Exchange rates

As a first acknowledgement Steigum (2003) states that there have been further cases of crisis due to speculative attacks on exchange rates. Secondly, it is also stated that finan-cial deregulation does not imply higher risk of crisis occurrence, or such extensive im-pacts as was experienced by Norway, Sweden and Finland. Thirdly, Steigum notes the striking similarities between the occurrences in Norway, Sweden and Finland during the crisis period. (Steigum, 2003) These are clearly displayed in Figure 2 where we notice similar exchange rate movements for all countries. We also see the effects of the spe-culative attacks following the floating of the Nordic countries currencies in the second half of 1992.

Figure2 Nordic Countries Exchange Rates Jan1990 - May 1993 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 9 9 0 J a n 1 9 9 0 Ma r 1 9 9 0 Ma y 1 9 9 0 J u l 1 9 9 0 Sep 1 9 9 0 N o v 1 9 9 1 J a n 1 9 9 1 Ma r 1 9 9 1 Ma y 1 9 9 1 J u l 1 9 9 1 Sep 1 9 9 1 N o v 1 9 9 2 J a n 1 9 9 2 Ma r 1 9 9 2 Ma y 1 9 9 2 J u l 1 9 9 2 Sep 1 9 9 2 N o v 1 9 9 3 J a n 1 9 9 3 Ma r 1 9 9 3 Ma y Year/Month E xc h ang e Rat e

Norway Exchange rate Sweden Exchange rate Finland Exchange Rate

(Figure 2 exchange rate calculated from the Nordic Central Bank)

The Floating of the Finnish Markka on the 8th of September 1992, after the speculative attack due to ERM turmoil, appeared to trigger speculations against the Swedish Krona (Gerlach and Smets, 1995).

Fiscal measures taken by the Swedish government allowed for a temporary decrease of the over-night interest rate, but as speculations against the Krona reassumed it was left to float on November 19th, bringing about an immediate devaluation of 9% which would reach 20% by the end of the year (Englund, 1999).

As the case of Sweden and Finland, Norway’s fixed exchange rate had been undermined due to inflation and devaluations. The 9% devaluation in May 1986 had implied increa-singly high interest rates in order to defend the Norwegian Krona against speculative at-tacks. However, as Sweden devalued its currency in November 1992, the Norwegian Krona came under increased pressure, this resulting in the floating of the currency on

December 10th. The Norwegian depreciation, which amounted to 4%, was however rela-tively small (Steigum, 2003).

Further supporting the movements of the interest rate are the observations and notations concerning the exchange rate. Prior to the floating of the Nordic currencies in late 1992 any speculations against them triggered interest rate movements. After floating the cur-rencies, any significant movements can be observed in the exchange rate.

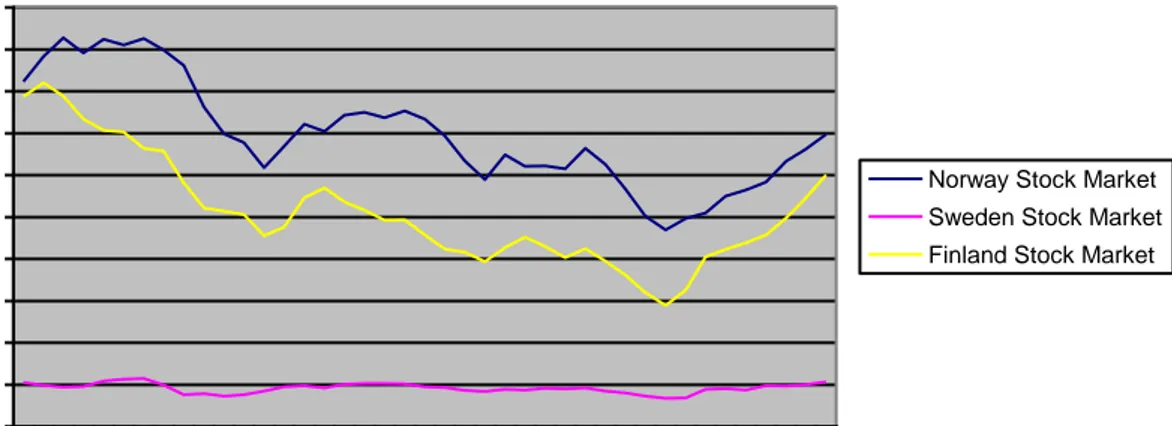

3.4 Stock Market

Stock market movements have not been extensively discussed in the research literature on the Nordic crisis, but do display some evidence of contagion. There are clear co-movements between the Nordic countries stock market indexes for the observed period. The movements of the stock markets are displayed in Figure 3, most notable is the neg-ative shock in late 1992 following the floating of the Nordic currencies.

Figure 3 Stock Market Nordic Countries Jan 1990 - May 1993 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400 1600 1800 2000 1990 Jan 1990 Apr 1990 jul 1990 Oc t 1991 Jan 1991 Apr 1991 Jul 1991 Oc t 1992 Jan 1992 Apr 1992 Jul 1992 Oc t 1993 Jan 1993 Apr Year/Month S to ck Ma rke t Ind ex

Norway Stock Market Sweden Stock Market Finland Stock Market

(Figure 3 stock market for the nordic countries calculated from OMX,HEX and the Bank of Norway) Also, we clearly observe the developments towards recession as the boom of the stock markets decrease substantially starting in 1990. This stock market boom was mentioned by Kokko, where he states that, in the period 1980 - 1989 the Swedish stock market was also booming reaching 1144 percent increase for the period, comparing to a global aver-age of 333 percent. When the crisis finally hit, it reduced real estate prices with 75 per-cent in five years while the stock market rates decreased by 50 perper-cent in the three years following its initiated decrease (Kokko, 1999).

The movements shown in the above figure seem to suggest strong evidence of inter-linked markets and possible contagion.

3.5 ERM

Although beyond the scope of this thesis, the European exchange rate mechanism (ERM) failure has been mentioned in many empirical results as having major effects on the Nordic situation. Thus, this section will briefly discuss empirical evidence and theo-rizing on the ERM impact for the Nordic countries.

Gerlach and Smets conducted an analysis and found evidence of contagion by empiri-cally testing exchange rate contagion for the Nordic countries through the use of interest rate data. Although including data from other ERM-countries, Gerlach and Smets find economically relevant evidence of exchange rate contagion, this due to speculative at-tacks, which in turn created devaluation expectations. Also observed are interest rate fluctuations between Nordic countries due to decisions of currency floating (Gerlach and Smets, 1995).Kraay notes the impact of speculative attacks on the Nordic curren-cies, as a result of devaluations among the countries as well as the ERM collapse of 1992. He also emphasizes that the distinction between the monetary policy implications of a speculative attack to those of market interest rates is difficult (Kraay, 2003).

Lindberg writes that the ineffectiveness of the fixed exchange rate policy7 as a result of the ERM-peg led to speculative attacks (Lindberg, 1993). A similar conclusion is drawn bySteigum who finds that the similar occurrences of Sweden, Norway and Fin-land during the crisis was to a great extent the result of its fixed exchange rate and its tie to the German monetary policy, resulting in a interest rate shock (Steigum, 2003). Fur-ther Steigum (2003) states that the German unification and its economic policy directly affected all Nordic countries interest rates as the fixed exchange rate was to ben upheld. A tighter economic policy had to be implemented due to rising German interest rates during the 1990’s.

4 THE MODEL OF REGRESSION ANALYSIS

In this section a descriptive summary of the data sources is presented followed by the process of how we carried out the regression with summary of the regression results.

4.1 Data

The data for Sweden was collected from Riksbank.se; the interest rate for Sweden is the key interest rate; it is the marginal average on a monthly basis. The exchange rate8is the Swedish krona dollar exchange rate, and the stock market index is the omxs30 monthly data. Finland’s interest rate is the base rate which was retrived from the bank of Finland, the exchange rate is the Finnish makka dollar exchange rate, and the stock market data was gotten from statistic Finland and it is the HEX general share index on a monthly basis. The data for Norway was collected from the central bank of Norway ;( it consist of the interest rate exchange rate and stock returns) the exchange rate is the Norwegian krone dollar rate on a monthly basis. We used the dollar exchange rate to ensure that they are all fixed to a particular currency to minimize the problems we might have with the exchange rate across different countries. The US interest rate is the federal fund ef-fective rate on a monthly basis which matures overnight.The stock market index was for the US was gotten from NASDAQ composite close on a monthly basis. The dollar is used because of its pivotal role in many foreign exchange deals.

4.2 Empirical examination of contagion

Based on the model on which we are going to test for contagion, we define contagion as the spread of market disturbances from one country to another. This is observed in movements in exchange rates, stock prices and interest rate. In our model we would first estimate the correlation coefficient of financial variables as was done by Park and Song (2001). Then as Calvo and Reinhart, (1996) and Frankel and Schmukler, (1996) showed in there model that a marked increase in correlations among different countries’ markets is regarded as evidence of contagion. For each series we run two sets of regressions that test for contagion in both countries.

In order to measure the existence and extent of contagion during the Nordic banking crisis period, we will focus on two financial markets, foreign exchange markets (ex-change rates) and stock markets, as is given in equations (1) and (2) This was provided by Park and Song (2001); and we would develop an ordinary least squares (OLS) model to determine the exchange rate and stock return

Equation

∆S

ti

=C

0+

i∆S

t-i i+

i∆dem

t-i+

ii

t-i j+

ii

t-i us+ e

t se(1)

∆Rti = Co + I∆Rt-ii + t-1- ∆St-ii) + iit-ii + iRt-ius + etse (2)Sti = exchange rate of country i’s currency per U.S. dollar

Krt = dem-dollar exchange rate (deutschmark-dollar) iti and itus= indicates monthly interest rates

Rti and Rtus=stock return in country i and U.S. at time t, measured by stock price index

etse =error term

∆=indicates the first order difference operator Country i= one of the three Nordic countries

(∆demt - ∆Stj)= indicates changes in the dem-dollar exchange rate relative to changes in

the exchange rate of currency of country j.

In our regression we include only lagged values of Rtus and itus because of the time

dif-ference between the US and the Nordic countries.

Changes in the Dem-Dollar exchange rate and the U.S interest rate reflects common shocks, whilst changes in domestic economic fundamentals are often explained by changes in the domestic interest rate. We use the Deutschmark-dollar exchange rate simply because the Deutsch mark happen to be Europe strongest currency and that Germany was the centre of Europe’s market. Both Sweden and Finland fixed their cur-rencies to the Deutsche mark and the Deutsche mark was fixed to the dollar. We used the interest rate to control for any aggregate shocks, which could simultaneously affect the different stock markets. The order of lags will be determined on the basis of Schwarz information criterion. Interest rates are widely used as a tool of monetary pol-icy, thus interest rate are not necessarily reflective of market forces.

Using a time series data from the countries, tested monthly, we estimate equations (1) and (2) by running an OLS regression for the Nordic countries. We the calculate for the correlation of the residuals. The residuals shows the relationship of the countries.During the period of the crisis, an unexpected development in one of the countries for example Sweden or a spill over effect from other countries would be reflected in the residuals. Thus if the residuals for any two of the countries are correlated it is likely that there was contagion between them.

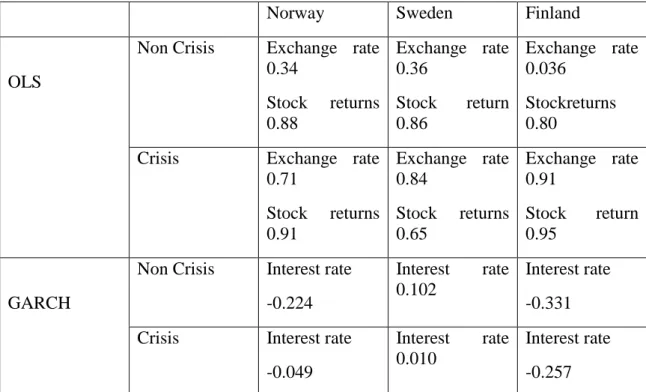

Table 1 show the explanatory power. The numbers used indicates the adjusted R2 . In the table we find that the explanatory powers of the two equations are accepted, when we consider the dependent variables expressed in terms of changes.

. . .” it is good practice to use adjusted R2

rather than R2 because R2 tends to give an overly optimistic picture of the fit of the regression, particularly when the number of ex-planatory variables is not very small compared with the number of observations9”. The explanatory power in equation (1) for Finland during the non-crisis period is low. Since the exchange rates were fixed and our results shows that there was no correlation between the countries, we decided to run another regression for the interest rate which

Henri Theil, Introduction to Econometrics, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1978, p. 135.

was allowed to move during the time of the crisis and to see if there was any conta-gious effect from the interest rate.

In equation (3) we consider a GARCH model of interest rate 10 in the countries we are investigating. We use the GARCH model because the interest rate exhibited volatility clustering during the period of the crisis which the OLS cannot mainly capture.

R

t= c +∑Ф

jx

t-j+ℓ (3)

R would signify the interest rate,

x’s the variables that affect the interest rate.

As in table (1), table (2) also shows that the explanatory power of Finland is low during the crisis and the non- crisis period. It also shows that it decreased in Sweden during the crisis period, for Norway it decreased significantly.

Table 1 shows the explanatory variable

Norway Sweden Finland

OLS

Non Crisis Exchange rate 0.34 Stock returns 0.88 Exchange rate 0.36 Stock return 0.86 Exchange rate 0.036 Stockreturns 0.80

Crisis Exchange rate

0.71 Stock returns 0.91 Exchange rate 0.84 Stock returns 0.65 Exchange rate 0.91 Stock return 0.95 GARCH

Non Crisis Interest rate -0.224

Interest rate 0.102

Interest rate -0.331 Crisis Interest rate

-0.049

Interest rate 0.010

Interest rate -0.257 Numbers indicates Adjusted R2

Using the data available as stated earlier we estimate equation (3) by GARCH model. We then compare the correlations of the residuals for the non-crisis and the crisis period to see if there was contagion. Correlation is measures of how two variables are related, how a variable changes with respect to the other. We then compare equation (1),(2) and (3) for the crisis and non crisis period to check whether there was any significant in-crease in the correlation between both periods.

10 A model first used by Sebastian Edwards(1998) in his paper interest rate volatility, contagion and con-vergence: and empirical investigation of the cases or Argentina, Chile and Mexico.

4.3 Statistical testing

To test for this significance of changes in correlation during the Nordic banking crisis, We therefore use the Anderson’s Z-Test.

The hypothesis for our paper is:

H0:βc

ij=βnc

ijH1:

β

c ij>βnc

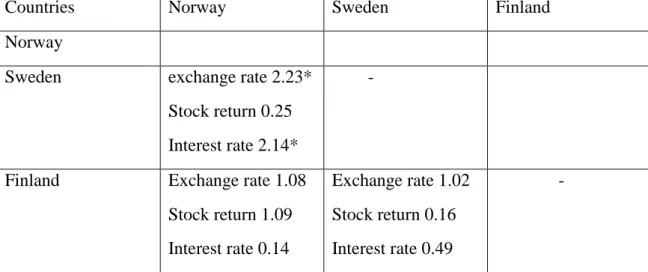

ijThe results from table (2) shows computed value for both the non crisis and crisis pe-riod, the results shows that the statistic test was only significant at 5% level. As stated earlier in our paper correlation coefficient of residuals do not always give a good meas-ure of contagion, this is because they are sometimes unable to differentiate between changes. Our results shows that there was a significance increase in the correlation for the exchange rate and interest rate. The significant test shows that it is significant at 5% level for the relationship between Norway and Sweden for both the interest rate and the exchange rate.

Table 2 significant test

Countries Norway Sweden Finland

Norway

Sweden exchange rate 2.23*

Stock return 0.25 Interest rate 2.14*

-

Finland Exchange rate 1.08

Stock return 1.09 Interest rate 0.14 Exchange rate 1.02 Stock return 0.16 Interest rate 0.49 - *:Significant at 5% level

The increase in the correlation between Norway and Sweden was significant, while the test between Norway and Finland was not significant the relationship between Sweden and finland was also not significant. Also the test for for the relationship of the stock re-turns between Norway and Sweden was not significant.

5 SUMMARY OF EMPIRICAL RESULTS

In our paper we have been studying if there was contagion during the Nordic banking crisis. The banking systems in the early 1980s were heavily regulated and even foreign banks was not allowed to operate until 1990. The regulations were motivated mainly by some principles and objective maintaining a low and stable interest rate, particularly in Norway and Sweden. From the correlation results from equation (1) we could observe that there was a negative correlation of the residuals and this was attributed to the fact that they all were using a fixed exchange rate system. So therefore, during the period of the crisis instead of much of the pressure been felt by the exchange rate, it was borne by the interest rate. You can also see the significant results in the statistical test in table (2). In equation (1) we used the interest rate to control for common shock. After the results we then decided to test again but this time not using the interest rate to control for common shocks.We cannot look into the exchange rate without looking into its effect on the interest rate Vis -a -Vis.

Eichengreen and Haussmann (1999) argued in there paper that in a fixed exchange rate system the central bank and government may be prevented from providing lender-of – last-resort services, they also say that because of a fixed exchange rate the central bank would be prevented from engineering inflation and to bring down real value of inde-fensible debts and thereby save the banking system. At the same time, lenders would understand that authorities would resort to tax as last option and thereby they demand a higher interest rate as compensation. However, a higher interest rate makes the banking sector fragile to the extent that debts grow very fast. By fixing its exchange rate, the central bank gives up its ability to influence the economy through monetary policy. When the exchange rate is fixed, the central bank does not allow the foreign exchange market to determine the exchange rate. This is more why the Nordic countries had to in-crease their interest rates. Development during the Nordic banking crisis suggested that the crisis started from Norway and spread to the other two countries. Sweden was the first to experience the crisis from which it spread to Finland.

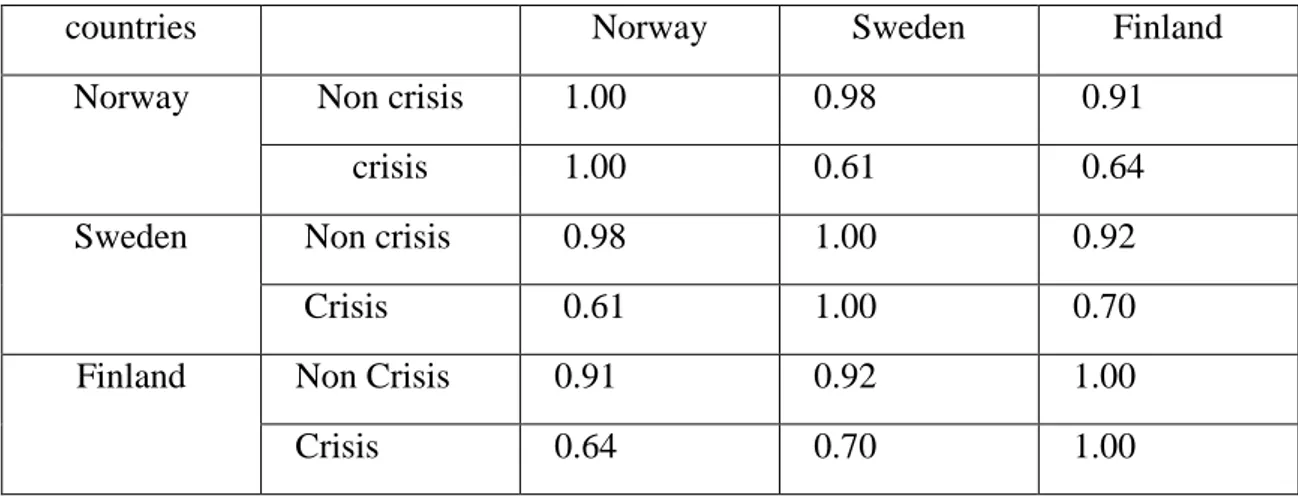

Table 3 shows the correlation of the residuals of the exchange rate

countries Norway Sweden Finland

Norway Non crisis 1.00 0.98 0.91

crisis 1.00 0.61 0.64

Sweden Non crisis 0.98 1.00 0.92

Crisis 0.61 1.00 0.70

Finland Non Crisis 0.91 0.92 1.00

Crisis 0.64 0.70 1.00

The tables shows the correlation of the Nordic countries during the non crisis and the crisis period. Table (1) shows the correlation of the exchange rate table (2) the correla-tion of the interest rate and table (3) shows that of the stock market.

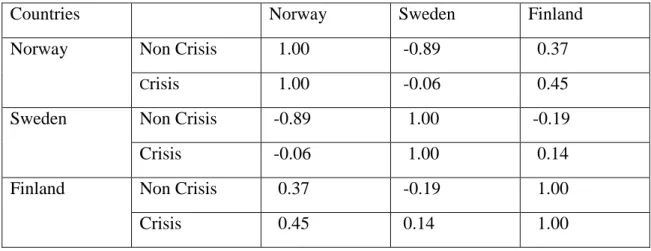

Table 4 shows the correlation of the residuals of the interest rate

Countries Norway Sweden Finland

Norway Non Crisis 1.00 -0.89 0.37

Crisis 1.00 -0.06 0.45

Sweden Non Crisis -0.89 1.00 -0.19

Crisis -0.06 1.00 0.14

Finland Non Crisis 0.37 -0.19 1.00

Crisis 0.45 0.14 1.00

Table 5 shows the correlation of the residuals of the stock market

Countries Norway Sweden Finland

Norway Non crisis 1.00 0.23 -0.19

Crisis 1.00 0.39 0.52

Sweden Non crisis 0.23 1.00 0.16

Crisis 0.39 1.00 0.27

Finland Non crisis -0.19 0.16 1.00

Crisis 0.52 0.27 1.00

Table (4 ), shows the correlations of the residuals of Nordic countries interest rate, there was a significant increase in the correlation coefficient of the residuals of the interest rate between Norway and Finland. It also shows that there is a less significant increase between Norway and Sweden and an increase between Sweden and Finland. During the period of the crisis since the government could not adjust the exchange rate the Swedish Riksbank increased its overnight interest rate to 12 percent.

In the estimations of equation (1) we discovered that the correlation of the residuals for the countries under investigation was uncorrelated, as can be seen from table (3) this re-sults was not expected. But we assume that it is because the countries had a fixed ex-change rate so much of the pressure to be felt by the exex-change rate was geared towards the interest rate. It was surprising to see that the interest rate had more significant coef-ficient in lagged than in the unlagged form.11 This is so because as changes are made in the interest rate during the crisis there was slow adjustment in the economy. A reason why we could not have found a large increase in the correlation was because the interest rate was rigid during the era of regulation and the exchange rates were pegged to

rency baskets. To be more precise Norway, Sweden and Finland pegged their currency to the ECU12 until 1992 when they decided to float the exchange rate.

The results for the stock markets shown in table (5) shows a correlation of the residuals for the countries. Compared to equation (1), equation (2) showed evidence of contagion. We found that there was an increase in the correlation of the residuals from the non-crisis to the non-crisis period in the stock market returns. The correlation coefficient in Swe-den was not as high compared to that of Finland and the reason could be that; SweSwe-den had deregulated its stock market prior to the crisis. The development also showed an in-crease in the correlation between Sweden and Finland, these results suggest that there was contagious effect through the stock market. The results also showed that Finland was more vulnerable to the crisis than Sweden. By 1992, the crisis had not only severely affected the Norwegian banking system but also spread to other Nordic countries as could be seen in the correlations of the interest rate. It increased only significantly be-tween Norway and Sweden but had a much greater significance bebe-tween Norway and Finland. This led to a depreciation of the Swedish krona and the devaluation of the Fin-nish markka. From the results of our empirical findings we could conclude that the cri-sis first broke out in Norway and was contagious to other Nordic countries, they spilled through the interest rate and the stock markets.

The Nordic countries had for a long time had a regulated financial system, and prior to the outburst of the crisis, it is possible that they could have been in crisis. Our results on the exchange rate have shown a high correlation (Table 3) between them indicating a near perfect linear relationship during the non-crisis period. We did not test for Norway because the crisis as we tested started from Norway, but when the crisis started Norway already had a flexible exchange rate. Though, all Nordic countries allowed branches of other banks to start operating in them in the 1990s we assume from our results that they were correlated even before the crisis and those private households were also allowed to trade in foreign currency.

Appendix 1 shows the deregulation process of the Nordic countries in the 1980’s. From our results of the regression we could draw a conclusion that the crisis might have started earlier than 1990, this could be as a result of the deruglation process. They crisis erupted because the economy might have borne these burden for long and could not continue holding any longer.

We however acknowledge that the results we got from the regression did show that though there was contagion but it did could not spread through the exchange rate be-cause it was fixed. It was only the correlation of the interest rate and stock returns that showed the existence of contagion. Which means that the crisis was contagious through the interest rate and stock returns.

6 CONCLUSION

There is not much doubt that it was the deregulatory measures of the 1980’s, which caused the Nordic countries of Norway, Sweden and Finland to be more vulnerable to the effects of financial instabilities. The consensus is also large concerning the misman-aged macroeconomic policies for these countries during the time of crisis. The initial boom following the newly deregulated environment caused banks to be subject to ex-cessive lending and increased risk taking. There was also a clear link between these and newly established financial companies, which increased rapidly during the years of eco-nomic boom.When the crisis finally hit, it started as a financial crisis in Norway and in a short period of time became a general banking crisis. This finally spread to Sweden and Finland in the early 1990’s and saw similar overall trends of development.

The evidence put forward in this article concerning the existence of contagion for these countries during the crisis period are somewhat mixed. There is not any significant indi-cation for contagion in the exchange rate, these where instead manifested in the interest rate. The expected interest rate shocks test positive for contagion. This is very striking as there is not only support for this in the data for the period, but also mentioned and discussed by many theorists. However there could be some explanation for these results as both Sweden and Finland had a fixed exchange rate policy until the later stage of the crisis. It should also be noted that there is evidence of the contagion effects from the ERM turbulence, although beyond the scope of this article there has been some neces-sary notes of its effects. Further and more extensive research on this effect and relation-ship is encouraged.

For the stock market movements there was very clear evidence of contagion with high values before the crisis and a further extensive increase during the crises for Sweden and Finland. This link was highly anticipated, as there is a close link between the coun-tries stock markets. A more noticeable link is the high correlation between Norway and Finland during the crisis period. This is an increase, which did not follow an already clear link. This provides further support for the existence of contagion during the Nor-dic crisis.

The conclusion is such that there are positive results for the existence of contagion; this is not only stated in this article with the support coming from our empirical testing but also through suggestive notations in much of the work put forward on the Nordic crisis, although not of direct reference to contagion. The limitations of this thesis and the scope for which it has been analysed leaves great room for further studies on the subject. This is not only concerned with contagion analysis for the Nordic countries but also for Europe as a whole during the early 1990’s. Also as already mentioned the subject of contagion is relatively new in the economic world and has thus not been extensively treated, leaving much room for further theorising as well as empirical testing. With re-spect to the subject of contagion for the Nordic crisis we do find strong evidence of con-tagion within the stock market. The evidence also suggests that there is positive correla-tion in exchange rate and interest rate movements. Further empirical testing on the sub-ject is recommended, perhaps including further indicators and other European countries.

REFERENCE LIST

Allen, F and Gale, D.(1999) “Bubbles,crises, and policy”Oxford Review of Economic policy.

Allen, F and Gale, D.(2000) ”financial contagion” Journal of Political Economy Allen, F and Gale, D.(2007) ”understanding financial crisis” Oxford University Press Alpo, W. (1998) ,“the collapse of the fixed exchange rate regime with sticky wages and Imperfect substitutability between domestic and foreign bonds”; European economic Review, p.1817-1838

Baig, T. and Goldfajn, I. (1999), “financial market contagion in the Asian crisis”IMF staff papers Vol. 46, No 2

Burkhard, D and Ceyla, P: the Nordic banking crises, Pitfalls in Financial Liberalization? IMF Occasional paper no. 161, Washington DC, April 1998,p. 25

Calvo, S and Reihart, C (1996), “Capital flow to Latin America: Is there evidence of Contagion effect?” in private capital flows to emerging market after the Mexican Crisis.G.A Calvo, M.Goldtein and E. Hochreiter Eds. Institute for international Economics Washington D.C

Caramazza, F. Ricci, L. and Salgado, R. (2004) “International financial

contagion in currency crises”, Journal of International Money and Finance, no 23, p. 51-70

Chuhan, P. Claessens, S. and Manning, N. (1998)”Equity and bond

flows to Asia and Latin America: The role of global and country factors”, Journal of Development Economics 55, p. 439-463

Corsetti, G. Paolo, P. Nouriel R. and Cédric T. (1998b) “Competitive devaluation: A welfare- based approach”, Mimeo

Drees, B and Pazarbasioglu, C. (1998) “The Nordic banking crisis, pitfalls in financial Liberalization” IMF Occasional Paper No. 161, Washington DC.

Dornbusch, R, Drazen, A. (1998), “Political contagion in currency crisis”, University of Maryland, Mimeo

Dornbusch,R. , Yung, C.P. , and Stijn, C. (1999), “contagion: how it spreads and how it can be stopped”. Mimeograph presented for discussion at the WIDER work shop on Financial contagion

Edwards, S. (1999) “How effective are capital controls?” National Bureau of economic Research, working paper, 7413

Eichengreen, B. A. , Rose and Wyplosz, C (1996) “Contagious currency crisis”,

National Bureau of Economic research, working paper no 5681 Eichengreen B. and Haussmann R. (1999) “exchange rate and financial fragility”;

NBER Working paper 7418, Cambridge MA

Englund, P. (1990) “Financial deregulation in Sweden”, European Economic Review 34 p. 385-393

Englund, P. (1999) “The Swedish banking crisis: Roots and consequences” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 15, No. 3

Favero, C. Giavazzi , F. (1999), “Looking for contagion: Evidence from the 1992 ERM Crisis”,

Folkerts-Lauda, D. and Garber, P. (1998), “capital flows from emerging market in a closing Environment, in global emerging markets”.Deutsche Bank research Gerlach, S. and Smets , F. (1995), “Contagious speculative attack”, European Journal Of Political Economy II, pp. 45-63

Goldberg, Linda (1993) “predicting exchange rate crisis”, Mexico revisited: Journal of International economics

Heijskanen, R. (September 1993), “The banking crisis in the Nordic countries”, Economic Review (Kansallis)

Honkapohja, S. Koskela, E. Gerlach, S. and Reichlin, L. (Oct., 1999), “The Economic Crisis of the 1990s in Finland”, Economic Policy, Vol. 14, No 29, pp. 399-436. Jonung, L. Söderström, H. Tson, S. Joakim (1996) “Depression in the North –

Boom and Bust in Sweden and Finland, 1985-1993”, Finnish Economic Papers

Kaminsky, L Graciela, R. and Carmen, M. (1999) “On Crisis, contagion and confusion”, Journal of International Economics

Ekonomisk Debatt, Årg 27, nr 2

Kraay, A. (2003) “Do high interest rates defend currencies during

speculative attacks?”, Journal of International Economics 59 p. 297–321 Krugman, P.R and Obstfeld, M (2007) “International economics: Theory and Policy” Addison-Wesley.

Leitner, Y. (2005) “Financial networks: Contagion, commitment and private Sector bailouts”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 60, no 6

Lybeck, J A (1994) ”Facit av finanskrisen”, SNS Förlag, Stockholm

Masson, P. (1998), “Contagion: Monsoon & Effects, spillovers, and sumps Between multiple equilibria”, IMF working paper 98/142

Morris, S and Shin, HS (1998) “unique equilibirim in a model of self-fulfiling currency attacks” American Economic Review

Ongena, S. Smith, D. C. and Michalsen, D. (January 2003) “Firms and their distressed banks: lessons from the Norwegian banking crisis” Journal of Financial Economics Volume 67, Issue 1, p. 81-112

Pritsker, M. (2000) “The channel for financial contagion” Federal Reserve Board Washington D.C pg 3

Rijckeghem, Caroline van and Weber, B. (1999), “financial contagion: spillover through banking centres. CFS working paper No 1999/17

Steigum, E. (2003) “Financial Deregulation with a Fixed Exchange Rate: Lessons from Norway’s Boom-Bust Cycle and Banking Crisis” Department of Economics,Norwegian School of Management BI, N-1301 Sandvika, Norway Valentin, L. (February 13, 2007) “Financial contagion in emerging markets”, Master Thesis, Stockholm school of economics