ISSN 1654-3602 ISBN 978-91-85835-46-1 HHJ

School of Health Sciences Jönköping University Dissertation Series No. 47, 2013

On Oral Health in Young Individuals

with a Focus on Sweden and Vietnam

A Cultural Perspective

Disser tation Series No . 47, 2013 On Oral Health in Young Individuals with a Focus on Sw eden and Vietnam - A Cultural Perspectiv e BRI T T M A RI E JA C OB SS O NDS

BRITTMARIE JACOBSSON

DS

Brittmarie Jacobsson has a PhLic in Oral Health Science from the School of Health Sciences in Jönköping, and a Master’s Degree in Public Health from the Nordic School of Public Health in Gothenburg, Sweden. She is a Dental Hygienist and a University Lecturer at Centre for Oral Health at School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University in Jönköping, Sweden. This book is her PhD thesis in Oral Health Science.

A detailed understanding of the factors influencing oral health is necessary to deliver effective oral health promotion and prevention. These factors are known as the determinants of oral health. In this Thesis culture is investigated as one of the oral health determinants.

Sweden today has a mixed population with people from many different countries displaying entirely different characteristics. The immigration process, such as changing living conditions as a result of settling in a new country and adopting new lifestyles, comprises sociobehavioural factors that have been shown to affect the risk of oral diseases, particularly in children. The culture context that an individual live in, the material condition and the knowledge and behaviour one has received from childhood constitute the basic elements for a child’s future living. Knowledge of different cultures can enhance communication and understanding efforts between health care providers and the population they serve.

In Vietnam there is an Oral Health Education Program, but the effect of this is not sufficient. To create an effective Oral Health Education Program, it is a prerequisite to have knowledge about oral health and disease. An epidemiological study describing the oral health situation among children in Da Nang was therefore performed.

To receive more knowledge about immigrants from Vietnam and other foreign countries, their food habits and awareness about oral health issues is one way to gain a better insight about these families living in Sweden but still have cultural values and beliefs in their habits and in their minds.

Due to the result of this Thesis, the findings provide strong evidence that culture is an important oral health determinant of dental caries and gingivitis in children. To strengthen the role of health communication with families of different cultures in both Sweden and Vietnam, there is obviously a need to improve the promotion of oral health care programmes for children with foreign-born parents in Sweden as well as for children in Vietnam.

On Oral Health in Young Individuals

with a Focus on Sweden and Vietnam

A Cultural Perspective

Brittmarie Jacobsson

Akademisk avhandling

För avläggande av doktorsexamen i Oral Hälsovetenskap som med tillstånd av Nämnden för utbildning och forskarutbildning vid Högskolan i Jönköping framläggs till

offentlig granskning fredagen den 6 december 2013 kl.13.00 i Forum Humanum, Hälsohögskolan, Högskolan i Jönköping.

Opponent: Professor Svante Twetman

Odontologisk Institut, Avdelning för hälsovetenskap Köpenhamns Universitet – University of Copenhagen

On Oral Health in Young Individuals

with a Focus on Sweden and Vietnam

A Cultural Perspective

Brittmarie Jacobsson

Akademisk avhandling

För avläggande av doktorsexamen i Oral Hälsovetenskap som med tillstånd av Nämnden för utbildning och forskarutbildning vid Högskolan i Jönköping framläggs till

offentlig granskning fredagen den 6 december 2013 kl.13.00 i Forum Humanum, Hälsohögskolan, Högskolan i Jönköping.

Opponent: Professor Svante Twetman

Odontologisk Institut, Avdelning för hälsovetenskap Köpenhamns Universitet – University of Copenhagen

Abstract

Title: On Oral Health in Young Individuals with a Focus on Sweden and Vietnam. A Cultural Perspective.

Author: Brittmarie Jacobsson

Opponent: Professor Svante Twetman

Language: English

Keywords: Child dentistry, dental caries, diet, epidemiology, gingivitis, immigrant

ISBN: 978-91-85835-46-1

Abstract

AIM: The overall aim of this thesis was to study culture as an oral health determinant for dental caries and gingivitis

in children living in Jönköping, Sweden, in relation to children living in Da Nang, Vietnam. MATERIALS AND METHODS: In 1993 and 2003, cross-sectional studies with clinical examinations and questionnaires were

performed in Jönköping, Sweden, with a random sample of 130 children from each of four age groups; 3, 5, 10 and 15 years. The final study sample comprised 739 children, 154 (21%) with two foreign-born parents and 585 (79%) with two Swedish-born parents (Paper I). In , all 15-year-olds (n=143) at one school in Jönköping, Sweden, were asked to participate in a questionnaire study connected to clinical data. The final sample comprised 117 individuals, 51 (44%) with foreign-born parents and 66 (56%) with Swedish-born parents (Paper II). In 2008, a cross-sectional study with clinical examinations and questionnaires was performed in Da Nang, Vietnam with 840 randomly selected children, 210 in each of four age groups; 3, 5, 10 and 15 years. The final sample comprised 745 individuals (Papers III and IV). RESULTS: In 2003, the mean number of decayed (initial and manifest) and filled

tooth surfaces was significantly higher in all age groups in children with foreign-born parents compared with children with Swedish-born parents. The gap between children with foreign-born parents and Swedish-born parents increased over the ten-year period from 1993 to 2003. The odds ratio of dental caries development among 10- and 15-year-old children with foreign-born-parents was more than six times higher than for their counterparts with Swedish-born parents (Paper I). Fifteen-year-olds born in Sweden of foreign-born parents and those who had immigrated before one year of age had a caries prevalence similar to 15-year-olds with Swedish-born parents, whereas the caries prevalence in children who had immigrated to Sweden after 7 years of age was 2-3 times higher (Paper II). Among the 3- and 5-year-olds in Vietnam, 98% suffered from dental caries, compared with 91% of 10- and 15-year-olds (Paper IV). The distribution of the most frequent values of decayed and filled primary tooth surfaces (dfs) in 5-year-olds was 16–20, and of decayed and filled permanent tooth surfaces (DFS) in 15-year-5-year-olds was 1–5. The maximum dfs was 76–80, and significant numbers of children had dfs between 20 and 50. The percentage of tooth sites with plaque and gingivitis was higher for children in all age groups with foreign-born parents compared with children with Swedish-born parents, except among the 15-year-olds in 2003. In Vietnam, the prevalence of plaque and gingivitis was high in all age groups, especially in 10- and 15-year-olds. Fifteen-year-olds in Sweden with foreign-born parents had a higher intake of snack products between principal meals compared with 15-year-olds with Swedish-born parents (Paper II). In Sweden, most children in all age groups brushed their teeth themselves or with help from their parents twice or more than twice a day (Paper I). Among 3- and 5-year-olds in Vietnam, about half of the parents reported that their children brushed their teeth themselves or with help from parents twice or more than twice a day (Paper III). All 3-year-olds and 99% of 5-year-olds in Sweden brushed their teeth with fluoride toothpaste (Paper I). Among 15-year-olds in Sweden with foreign-born parents, 88% reported that they brushed their teeth with fluoride toothpaste at least twice a day compared with 98% of 15-year-olds with Swedish-born parents (Paper II). In Vietnam, 44–78% of the children used fluoride toothpaste for toothbrushing and 51% consumed sweets between principal meals at least once a day (Paper III). Sweetened milk was the most common source of this sugar intake for the 3- and 5-year-olds (Paper III).

2000

CONCLUSIONS: Culture is an important oral health determinant for dental caries and gingivitis in children.

Abstract

Title: On Oral Health in Young Individuals with a Focus on Sweden and Vietnam. A Cultural Perspective.

Author: Brittmarie Jacobsson

Opponent: Professor Svante Twetman

Language: English

Keywords: Child dentistry, dental caries, diet, epidemiology, gingivitis, immigrant

ISBN: 978-91-85835-46-1

Abstract

AIM: The overall aim of this thesis was to study culture as an oral health determinant for dental caries and gingivitis

in children living in Jönköping, Sweden, in relation to children living in Da Nang, Vietnam. MATERIALS AND METHODS: In 1993 and 2003, cross-sectional studies with clinical examinations and questionnaires were

performed in Jönköping, Sweden, with a random sample of 130 children from each of four age groups; 3, 5, 10 and 15 years. The final study sample comprised 739 children, 154 (21%) with two foreign-born parents and 585 (79%) with two Swedish-born parents (Paper I). In , all 15-year-olds (n=143) at one school in Jönköping, Sweden, were asked to participate in a questionnaire study connected to clinical data. The final sample comprised 117 individuals, 51 (44%) with foreign-born parents and 66 (56%) with Swedish-born parents (Paper II). In 2008, a cross-sectional study with clinical examinations and questionnaires was performed in Da Nang, Vietnam with 840 randomly selected children, 210 in each of four age groups; 3, 5, 10 and 15 years. The final sample comprised 745 individuals (Papers III and IV). RESULTS: In 2003, the mean number of decayed (initial and manifest) and filled

tooth surfaces was significantly higher in all age groups in children with foreign-born parents compared with children with Swedish-born parents. The gap between children with foreign-born parents and Swedish-born parents increased over the ten-year period from 1993 to 2003. The odds ratio of dental caries development among 10- and 15-year-old children with foreign-born-parents was more than six times higher than for their counterparts with Swedish-born parents (Paper I). Fifteen-year-olds born in Sweden of foreign-born parents and those who had immigrated before one year of age had a caries prevalence similar to 15-year-olds with Swedish-born parents, whereas the caries prevalence in children who had immigrated to Sweden after 7 years of age was 2-3 times higher (Paper II). Among the 3- and 5-year-olds in Vietnam, 98% suffered from dental caries, compared with 91% of 10- and 15-year-olds (Paper IV). The distribution of the most frequent values of decayed and filled primary tooth surfaces (dfs) in 5-year-olds was 16–20, and of decayed and filled permanent tooth surfaces (DFS) in 15-year-5-year-olds was 1–5. The maximum dfs was 76–80, and significant numbers of children had dfs between 20 and 50. The percentage of tooth sites with plaque and gingivitis was higher for children in all age groups with foreign-born parents compared with children with Swedish-born parents, except among the 15-year-olds in 2003. In Vietnam, the prevalence of plaque and gingivitis was high in all age groups, especially in 10- and 15-year-olds. Fifteen-year-olds in Sweden with foreign-born parents had a higher intake of snack products between principal meals compared with 15-year-olds with Swedish-born parents (Paper II). In Sweden, most children in all age groups brushed their teeth themselves or with help from their parents twice or more than twice a day (Paper I). Among 3- and 5-year-olds in Vietnam, about half of the parents reported that their children brushed their teeth themselves or with help from parents twice or more than twice a day (Paper III). All 3-year-olds and 99% of 5-year-olds in Sweden brushed their teeth with fluoride toothpaste (Paper I). Among 15-year-olds in Sweden with foreign-born parents, 88% reported that they brushed their teeth with fluoride toothpaste at least twice a day compared with 98% of 15-year-olds with Swedish-born parents (Paper II). In Vietnam, 44–78% of the children used fluoride toothpaste for toothbrushing and 51% consumed sweets between principal meals at least once a day (Paper III). Sweetened milk was the most common source of this sugar intake for the 3- and 5-year-olds (Paper III).

2000

School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University

On Oral Health in Young Individuals

with a Focus on Sweden and Vietnam

A Cultural Perspective

BRITTMARIE JACOBSSON

DISSERTATION SERIES NO. 47, 2013

School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University

On Oral Health in Young Individuals

with a Focus on Sweden and Vietnam

A Cultural Perspective

BRITTMARIE JACOBSSON

©

BRITTMARIE JACOBSSON, 2013 Publisher: School of Health Sciences Print: Intellecta InfologISSN 1654-3602

©

BRITTMARIE JACOBSSON, 2013 Publisher: School of Health Sciences Print: Intellecta InfologAbstract

AIM: The overall aim of this thesis was to study culture as an oral health determinant for dental caries and gingivitis in children living in Jönköping, Sweden, in relation to children living in Da Nang, Vietnam. MATERIALS AND METHODS: In 1993 and 2003, cross-sectional studies with clinical examinations and questionnaires were performed in Jönköping, Sweden, with a random sample of 130 children from each of four age groups; 3, 5, 10 and 15 years. The final study sample comprised 739 children, 154 (21%) with two foreign-born parents and 585 (79%) with two Swedish-born parents (Paper I). In 2000, all 15-year-olds (n=143) at one school in Jönköping, Sweden, were asked to participate in a questionnaire study connected to clinical data. The final sample comprised 117 individuals, 51 (44%) with foreign-born parents and 66 (56%) with Swedish-born parents (Paper II). In 2008, a cross-sectional study with clinical examinations and questionnaires was performed in Da Nang, Vietnam with 840 randomly selected children, 210 in each of four age groups; 3, 5, 10 and 15 years. The final sample comprised 745 individuals (Papers III and IV). RESULTS: In 2003, the mean number of decayed (initial and manifest) and filled tooth surfaces was significantly higher in all age groups in children with foreign-born parents compared with children with Swedish-born parents. The gap between children with foreign-born parents and Swedish-born parents increased over the ten-year period from 1993 to 2003. The odds ratio of dental caries development among 10- and 15-year-old children with foreign-born-parents was more than six times higher than for their counterparts with Swedish-born parents (Paper I). Fifteen-year-olds born in Sweden of foreign-born parents and those who had immigrated before one year of age had a caries prevalence similar to 15-year-olds with Swedish-born parents, whereas the caries prevalence in children who had immigrated to Sweden after 7 years of age was 2-3 times higher (Paper II). Among the 3- and 5-year-olds in Vietnam, 98% suffered

Abstract

AIM: The overall aim of this thesis was to study culture as an oral health determinant for dental caries and gingivitis in children living in Jönköping, Sweden, in relation to children living in Da Nang, Vietnam. MATERIALS AND METHODS: In 1993 and 2003, cross-sectional studies with clinical examinations and questionnaires were performed in Jönköping, Sweden, with a random sample of 130 children from each of four age groups; 3, 5, 10 and 15 years. The final study sample comprised 739 children, 154 (21%) with two foreign-born parents and 585 (79%) with two Swedish-born parents (Paper I). In 2000, all 15-year-olds (n=143) at one school in Jönköping, Sweden, were asked to participate in a questionnaire study connected to clinical data. The final sample comprised 117 individuals, 51 (44%) with foreign-born parents and 66 (56%) with Swedish-born parents (Paper II). In 2008, a cross-sectional study with clinical examinations and questionnaires was performed in Da Nang, Vietnam with 840 randomly selected children, 210 in each of four age groups; 3, 5, 10 and 15 years. The final sample comprised 745 individuals (Papers III and IV). RESULTS: In 2003, the mean number of decayed (initial and manifest) and filled tooth surfaces was significantly higher in all age groups in children with foreign-born parents compared with children with Swedish-born parents. The gap between children with foreign-born parents and Swedish-born parents increased over the ten-year period from 1993 to 2003. The odds ratio of dental caries development among 10- and 15-year-old children with foreign-born-parents was more than six times higher than for their counterparts with Swedish-born parents (Paper I). Fifteen-year-olds born in Sweden of foreign-born parents and those who had immigrated before one year of age had a caries prevalence similar to 15-year-olds with Swedish-born parents, whereas the caries prevalence in children who had immigrated to Sweden after 7 years of age was 2-3 times higher (Paper II). Among the 3- and 5-year-olds in Vietnam, 98% suffered

from dental caries, compared with 91% of 10- and 15-year-olds (Paper IV). The distribution of the most frequent values of decayed and filled primary tooth surfaces (dfs) in 5-year-olds was 16–20, and of decayed and filled permanent tooth surfaces (DFS) in 15-year-olds was 1–5. The maximum dfs was 76–80, and significant numbers of children had dfs between 20 and 50. The percentage of tooth sites with plaque and gingivitis was higher for children in all age groups with foreign-born parents compared with children with Swedish-born parents, except among the 15-year-olds in 2003. In Vietnam, the prevalence of plaque and gingivitis was high in all age groups, especially in 10- and 15-year-olds. Fifteen-year-olds in Sweden with foreign-born parents had a higher intake of snack products between principal meals compared with 15-year-olds with Swedish-born parents (Paper II). In Sweden, most children in all age groups brushed their teeth themselves or with help from their parents twice or more than twice a day (Paper I). Among 3- and 5-year-olds in Vietnam, about half of the parents reported that their children brushed their teeth themselves or with help from parents twice or more than twice a day (Paper III). All 3-year-olds and 99% of 5-year-olds in Sweden brushed their teeth with fluoride toothpaste (Paper I). Among 15-year-olds in Sweden with foreign-born parents, 88% reported that they brushed their teeth with fluoride toothpaste at least twice a day compared with 98% of 15-year-olds with Swedish-born parents (Paper II). In Vietnam, 44–78% of the children used fluoride toothpaste for toothbrushing and 51% consumed sweets between principal meals at least once a day (Paper III). Sweetened milk was the most common source of this sugar intake for the 3- and 5-year-olds (Paper III). CONCLUSIONS: Culture is an important oral health determinant for dental caries and gingivitis in children. There is an urgent need to improve oral health care promotion and preventive programmes for children with foreign-born parents in Sweden, but also a great need for such programmes for children in Vietnam.

Keywords: Child dentistry, dental caries, diet, epidemiology, gingivitis, immigrant

from dental caries, compared with 91% of 10- and 15-year-olds (Paper IV). The distribution of the most frequent values of decayed and filled primary tooth surfaces (dfs) in 5-year-olds was 16–20, and of decayed and filled permanent tooth surfaces (DFS) in 15-year-olds was 1–5. The maximum dfs was 76–80, and significant numbers of children had dfs between 20 and 50. The percentage of tooth sites with plaque and gingivitis was higher for children in all age groups with foreign-born parents compared with children with Swedish-born parents, except among the 15-year-olds in 2003. In Vietnam, the prevalence of plaque and gingivitis was high in all age groups, especially in 10- and 15-year-olds. Fifteen-year-olds in Sweden with foreign-born parents had a higher intake of snack products between principal meals compared with 15-year-olds with Swedish-born parents (Paper II). In Sweden, most children in all age groups brushed their teeth themselves or with help from their parents twice or more than twice a day (Paper I). Among 3- and 5-year-olds in Vietnam, about half of the parents reported that their children brushed their teeth themselves or with help from parents twice or more than twice a day (Paper III). All 3-year-olds and 99% of 5-year-olds in Sweden brushed their teeth with fluoride toothpaste (Paper I). Among 15-year-olds in Sweden with foreign-born parents, 88% reported that they brushed their teeth with fluoride toothpaste at least twice a day compared with 98% of 15-year-olds with Swedish-born parents (Paper II). In Vietnam, 44–78% of the children used fluoride toothpaste for toothbrushing and 51% consumed sweets between principal meals at least once a day (Paper III). Sweetened milk was the most common source of this sugar intake for the 3- and 5-year-olds (Paper III). CONCLUSIONS: Culture is an important oral health determinant for dental caries and gingivitis in children. There is an urgent need to improve oral health care promotion and preventive programmes for children with foreign-born parents in Sweden, but also a great need for such programmes for children in Vietnam.

Original Papers

This thesis is based on the following papers, which are referenced in the text with Roman numerals:

Paper I

Jacobsson B, Koch G, Magnusson T, Hugoson A. Oral health in young individuals with foreign and Swedish backgrounds – a ten-year perspective.

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry 2011;12:151–158.

Paper II

Jacobsson B, Wendt LK, Johansson I. Dental caries and caries associated factors in Swedish 15-year-olds in relation to immigrant background. Swed Dent

J 2005;29:71–79.

Paper III

Jacobsson B, Ho Thi T, Hoang Ngoc C, Hugoson A. Oral Health of Children in Da Nang, Vietnam. Sociodemographic conditions, knowledge of dental diseases, dental care and dietary habits. Submitted.

Paper IV

Jacobsson B, Ho Thi T, Hoang Ngoc C, Hugoson A. Oral Health of Children in Da Nang, Vietnam. Dental caries, caries associated factors and gingivitis. Submitted.

Papers I and II have been reprinted with kind permission of the respective journals.

Original Papers

This thesis is based on the following papers, which are referenced in the text with Roman numerals:

Paper I

Jacobsson B, Koch G, Magnusson T, Hugoson A. Oral health in young individuals with foreign and Swedish backgrounds – a ten-year perspective.

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry 2011;12:151–158.

Paper II

Jacobsson B, Wendt LK, Johansson I. Dental caries and caries associated factors in Swedish 15-year-olds in relation to immigrant background. Swed Dent

J 2005;29:71–79.

Paper III

Jacobsson B, Ho Thi T, Hoang Ngoc C, Hugoson A. Oral Health of Children in Da Nang, Vietnam. Sociodemographic conditions, knowledge of dental diseases, dental care and dietary habits. Submitted.

Paper IV

Jacobsson B, Ho Thi T, Hoang Ngoc C, Hugoson A. Oral Health of Children in Da Nang, Vietnam. Dental caries, caries associated factors and gingivitis. Submitted.

Papers I and II have been reprinted with kind permission of the respective journals.

Abbreviations

ANOVA Analysis of Variance CI Confidence Interval

CIOM Council for International Organisations of Medical Science

CRFA Common Risk Factor Approach

CSDH Commission on the Social Determinants of Health De Decayed enamel/initial dental caries in the

permanent dentition

Dd Decayed dentin/manifest dental caries in the

permanent dentition

Ded Decayed enamel/initial and dentin/manifest dental

caries in the permanent dentition

dfs Decayed and filled primary tooth surfaces DFS Decayed and Filled permanent tooth Surfaces dft Decayed and filled primary teeth

DFT Decayed and Filled permanent Teeth dl Decilitre

F cohort Children with two parents with foreign backgrounds FS Filled Surfaces in the permanent dentition

g Grams

GDP Gross Domestic Product GI Gingival Index

km2 Square kilometres

n Number

NFA National Food Administration

NOHSV National Oral Health Survey of Vietnam OR Odds Ratio

p-value Statistical significance level

PLI Plaque Index ppm Parts per million

S cohort Children with two parents with Swedish backgrounds SD Standard Deviation

SE Standard Error UN United Nations

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees US United States

WHO World Health Organization

Abbreviations

ANOVA Analysis of Variance CI Confidence Interval

CIOM Council for International Organisations of Medical Science

CRFA Common Risk Factor Approach

CSDH Commission on the Social Determinants of Health De Decayed enamel/initial dental caries in the

permanent dentition

Dd Decayed dentin/manifest dental caries in the

permanent dentition

Ded Decayed enamel/initial and dentin/manifest dental

caries in the permanent dentition

dfs Decayed and filled primary tooth surfaces DFS Decayed and Filled permanent tooth Surfaces dft Decayed and filled primary teeth

DFT Decayed and Filled permanent Teeth dl Decilitre

F cohort Children with two parents with foreign backgrounds FS Filled Surfaces in the permanent dentition

g Grams

GDP Gross Domestic Product GI Gingival Index

km2 Square kilometres

n Number

NFA National Food Administration

NOHSV National Oral Health Survey of Vietnam OR Odds Ratio

p-value Statistical significance level

PLI Plaque Index ppm Parts per million

S cohort Children with two parents with Swedish backgrounds SD Standard Deviation

SE Standard Error UN United Nations

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees US United States

Contents

Introduction ... 1

Oral Health ... 1

Dental Caries ... 2

Gingivitis ... 3

Dental Care and Oral Health Status in Sweden and Jönköping ... 4

Dental Care and Oral Health Status in Vietnam and Da Nang ... 6

Oral Health Determinants ... 9

Knowledge and values ... 10

Oral hygiene habits ... 10

Fluoride use ... 11

Dietary habits ... 12

Culture ... 13

A multicultural society ... 15

Sweden as a multicultural society ... 17

Vietnam as a multicultural society ... 18

Rationale for the Study ... 20

Overall and Specific Aims ... 21

Demographic Data ... 22 Sweden ... 22 Jönköping ... 22 Vietnam ... 23 Da Nang ... 24 Participants ... 25 Paper I ... 25 Paper II ... 26

Papers III and IV ... 26

Methods ... 29 Paper I ... 29 Clinical examination ... 29

Contents

Introduction ... 1 Oral Health ... 1 Dental Caries ... 2 Gingivitis ... 3Dental Care and Oral Health Status in Sweden and Jönköping ... 4

Dental Care and Oral Health Status in Vietnam and Da Nang ... 6

Oral Health Determinants ... 9

Knowledge and values ... 10

Oral hygiene habits ... 10

Fluoride use ... 11

Dietary habits ... 12

Culture ... 13

A multicultural society ... 15

Sweden as a multicultural society ... 17

Vietnam as a multicultural society ... 18

Rationale for the Study ... 20

Overall and Specific Aims ... 21

Demographic Data ... 22 Sweden ... 22 Jönköping ... 22 Vietnam ... 23 Da Nang ... 24 Participants ... 25 Paper I ... 25 Paper II ... 26

Papers III and IV ... 26

Methods ... 29

Paper I ... 29

Questionnaire ... 29

Paper II ... 29

Clinical data... 30

Questionnaire ... 30

Papers III and IV ... 31

Clinical examination ... 31

Questionnaire ... 31

Diagnostic Criteria ... 32

Number of teeth (Papers I, II and IV) ... 32

Dental caries ... 32

Clinical caries (Papers I, II and IV) ... 32

Radiographic caries (Papers I and II) ... 32

Decayed and filled primary and permanent tooth surfaces (Papers I, II and IV) ... 33

Plaque (Papers I and IV) ... 33

Gingival status (Papers I and IV) ... 33

Background data (Papers I, II, III and IV) ... 33

Dietary habits (Papers I, II, III and IV) ... 33

Oral hygiene habits and fluoride exposure (Papers I, II, III and IV) .... 34

Statistical methods... 34

Reliability and validity ... 35

Ethical Issues ... 36

Ethical approval ... 36

Informed consent ... 37

Ethical aspects of methods ... 37

Confidentiality ... 39

Principles regulations ... 39

Results ... 40

Oral Health Status ... 40

Number of teeth (Papers I and IV) ... 40

Caries-free individuals (Papers I and IV) ... 40

Questionnaire ... 29

Paper II ... 29

Clinical data... 30

Questionnaire ... 30

Papers III and IV ... 31

Clinical examination ... 31

Questionnaire ... 31

Diagnostic Criteria ... 32

Number of teeth (Papers I, II and IV) ... 32

Dental caries ... 32

Clinical caries (Papers I, II and IV) ... 32

Radiographic caries (Papers I and II) ... 32

Decayed and filled primary and permanent tooth surfaces (Papers I, II and IV) ... 33

Plaque (Papers I and IV) ... 33

Gingival status (Papers I and IV) ... 33

Background data (Papers I, II, III and IV) ... 33

Dietary habits (Papers I, II, III and IV) ... 33

Oral hygiene habits and fluoride exposure (Papers I, II, III and IV) .... 34

Statistical methods... 34

Reliability and validity ... 35

Ethical Issues ... 36

Ethical approval ... 36

Informed consent ... 37

Ethical aspects of methods ... 37

Confidentiality ... 39

Principles regulations ... 39

Results ... 40

Oral Health Status ... 40

Number of teeth (Papers I and IV) ... 40

Plaque and gingivitis (Papers I and IV) ... 47

Sociodemographic Data (Papers I, II and III) ... 50

Living conditions, place of residence, parental marital status and number of siblings ... 50

Parents’ education and family economy ... 50

Time at school ... 51

Knowledge and Values (Papers I and III) ... 51

Oral Hygiene Habits (Papers I, II and III) ... 54

Dietary Habits Study (Papers I, II and III) ... 55

Principal meals ... 55

Snacks between principal meals ... 55

Sugar consumption ... 57

Associations between Dental Caries and Foreign and Swedish Backgrounds (Papers I, II and IV) ... 59

Caries in Relation to Age at Immigration (Paper II) ... 63

Dental Resources (Papers I and III)... 64

Discussion ... 65

Methodological considerations ... 65

Culture as an Oral Health Determinant ... 68

Comprehensive Understanding ... 74

Culture as an Oral Health Determinant ... 74

Conclusion ... 76

Clinical Implications ... 77

Research Implications ... 79

Svensk sammanfattning ... 80

Oral hälsa hos unga individer med fokus på Sverige och Vietnam. Ett kulturellt perspektiv. ... 80

Acknowledgements ... 83

References ... 86

Plaque and gingivitis (Papers I and IV) ... 47

Sociodemographic Data (Papers I, II and III) ... 50

Living conditions, place of residence, parental marital status and number of siblings ... 50

Parents’ education and family economy ... 50

Time at school ... 51

Knowledge and Values (Papers I and III) ... 51

Oral Hygiene Habits (Papers I, II and III) ... 54

Dietary Habits Study (Papers I, II and III) ... 55

Principal meals ... 55

Snacks between principal meals ... 55

Sugar consumption ... 57

Associations between Dental Caries and Foreign and Swedish Backgrounds (Papers I, II and IV) ... 59

Caries in Relation to Age at Immigration (Paper II) ... 63

Dental Resources (Papers I and III)... 64

Discussion ... 65

Methodological considerations ... 65

Culture as an Oral Health Determinant ... 68

Comprehensive Understanding ... 74

Culture as an Oral Health Determinant ... 74

Conclusion ... 76

Clinical Implications ... 77

Research Implications ... 79

Svensk sammanfattning ... 80

Oral hälsa hos unga individer med fokus på Sverige och Vietnam. Ett kulturellt perspektiv. ... 80

Acknowledgements ... 83

Introduction

In Sweden, several epidemiological investigations describing oral health have been presented, the majority of a descriptive, cross-sectional nature. Jönköping has a long tradition of performing such studies. These epidemiological studies have been helpful for planning and organizing effective dental care systems in Jönköping City and County, especially for promoting preventive oral health care programmes for children. To deepen the cooperation in oral health science between Jönköping University and Da Nang University of Medical Technology and Pharmacy in Da Nang, Vietnam, an epidemiological investigation was undertaken to describe the oral health situation and the knowledge about oral health of children in Da Nang, at the same time broadening knowledge about oral health issues.

Oral Health

Two broad definitions of health and oral health can be identified. The first involves biophysical wholeness.1-2 In this case, the aim is to identify any

pathological sign that indicates the existence of a pathological lesion, e.g. dental caries. An alternative definition of health has been presented by the World Health Organization (WHO),3 which defines health as being different from the

“absence of disease.” Oral health means more than healthy teeth; it is a determinant factor for quality of life. Oral health is integral to general health and is essential for mental and social well-being.4 This definition clarifies the

essential distinction between disease and health. Disease is a narrow concept referring to a pathological process, while health refers to something broader and is largely concerned with individuals’ subjective experience of their bodies.

Introduction

In Sweden, several epidemiological investigations describing oral health have been presented, the majority of a descriptive, cross-sectional nature. Jönköping has a long tradition of performing such studies. These epidemiological studies have been helpful for planning and organizing effective dental care systems in Jönköping City and County, especially for promoting preventive oral health care programmes for children. To deepen the cooperation in oral health science between Jönköping University and Da Nang University of Medical Technology and Pharmacy in Da Nang, Vietnam, an epidemiological investigation was undertaken to describe the oral health situation and the knowledge about oral health of children in Da Nang, at the same time broadening knowledge about oral health issues.

Oral Health

Two broad definitions of health and oral health can be identified. The first involves biophysical wholeness.1-2 In this case, the aim is to identify any

pathological sign that indicates the existence of a pathological lesion, e.g. dental caries. An alternative definition of health has been presented by the World Health Organization (WHO),3 which defines health as being different from the

“absence of disease.” Oral health means more than healthy teeth; it is a determinant factor for quality of life. Oral health is integral to general health and is essential for mental and social well-being.4 This definition clarifies the

essential distinction between disease and health. Disease is a narrow concept referring to a pathological process, while health refers to something broader and is largely concerned with individuals’ subjective experience of their bodies.

Oral health is a part of everyday life, an essential dimension of quality of life. What is meant by good oral health varies considerably across societies and social groups according to local values, expectations and philosophies.5 An

understanding of cultural background allows an important awareness of health beliefs and attitudes.

At a global level, new changing patterns of oral health and oral disease related to changes in living conditions and lifestyles have been reported. A proper understanding of the social context of oral health and illness is a prerequisite to solving emerging challenges. The future challenges for dentistry and oral public health care planning are limited to areas of expertise. This relates to non-clinical dimensions of dental practice, such as oral health promotion, community-based preventive care and outreach activities.5

Dental Caries

Dental caries still poses a large public health problem. Extensive caries can lead to large-scale suffering and reduction in quality of life both functionally and aesthetically.6-7 Caries is the most common chronic disease in childhood,

affecting 75% of children by the age of 15 years.8 It is also one of the most

prevalent oral diseases in several Asian and Latin-American countries.4

Caries is a dynamic, dietomicrobial, site-specific disease,9 resulting from

interactions among the host (tooth and saliva), the microflora (the microbiological ecology in the biofilm on the tooth) and carbohydrates in the food (substrate for the microflora). These factors are involved in cycles of demineralisation and remineralisation. The early stage of caries can be reversed by modifying or eliminating etiological factors, such as the biofilm and sucrose in the diet, and by increasing protective factors, such as regular toothbrushing

Oral health is a part of everyday life, an essential dimension of quality of life. What is meant by good oral health varies considerably across societies and social groups according to local values, expectations and philosophies.5 An

understanding of cultural background allows an important awareness of health beliefs and attitudes.

At a global level, new changing patterns of oral health and oral disease related to changes in living conditions and lifestyles have been reported. A proper understanding of the social context of oral health and illness is a prerequisite to solving emerging challenges. The future challenges for dentistry and oral public health care planning are limited to areas of expertise. This relates to non-clinical dimensions of dental practice, such as oral health promotion, community-based preventive care and outreach activities.5

Dental Caries

Dental caries still poses a large public health problem. Extensive caries can lead to large-scale suffering and reduction in quality of life both functionally and aesthetically.6-7 Caries is the most common chronic disease in childhood,

affecting 75% of children by the age of 15 years.8 It is also one of the most

prevalent oral diseases in several Asian and Latin-American countries.4

Caries is a dynamic, dietomicrobial, site-specific disease,9 resulting from

interactions among the host (tooth and saliva), the microflora (the microbiological ecology in the biofilm on the tooth) and carbohydrates in the food (substrate for the microflora). These factors are involved in cycles of demineralisation and remineralisation. The early stage of caries can be reversed by modifying or eliminating etiological factors, such as the biofilm and sucrose in the diet, and by increasing protective factors, such as regular toothbrushing

important defence factors against caries. Caries therefore results from a disturbance in the balance between attack factors and defence factors.10

Lactobacillus and Streptococcus mutans are tooth-colonising bacteria with a great

ability to produce acid. Simultaneously, they are able to tolerate an acid environment. They are therefore regarded as central to the development of caries. Mealtime frequency, carbohydrate content and food consistency determine the degree of pH-reduction.11-12

In Europe preventive programmes based on information and instruction in oral hygiene, fluoride administration and sugar restrictions have contributed to improvement in oral health.13-14 In spite of the fact that oral health has

improved in recent years, there are still individuals in the population with a large number of decayed teeth. Today, approximately 20% of the population in Europe accounts for approximately 80% of dental caries.15-17 Despite the

widespread decline in caries prevalence in permanent teeth in high-income countries over the past few decades, disparities still remain and many children in low-income families and in minority groups still develop dental caries to a greater extent.8

Gingivitis

Plaque-associated gingivitis is the most prevalent form of gingival inflammation and is caused by an accumulation of dental plaque on the tooth surface at the gingival margin.18 Plaque is a biofilm – a community of microorganisms

attached to a surface. These organisms are organised into a three-dimensional structure enclosed in a matrix of extracellular material. Dental plaque is an adherent deposit of bacteria and their products. The response to this biofilm is inflammation of the surrounding local gingival and periodontal tissue. The important defence factors against caries. Caries therefore results from a

disturbance in the balance between attack factors and defence factors.10

Lactobacillus and Streptococcus mutans are tooth-colonising bacteria with a great

ability to produce acid. Simultaneously, they are able to tolerate an acid environment. They are therefore regarded as central to the development of caries. Mealtime frequency, carbohydrate content and food consistency determine the degree of pH-reduction.11-12

In Europe preventive programmes based on information and instruction in oral hygiene, fluoride administration and sugar restrictions have contributed to improvement in oral health.13-14 In spite of the fact that oral health has

improved in recent years, there are still individuals in the population with a large number of decayed teeth. Today, approximately 20% of the population in Europe accounts for approximately 80% of dental caries.15-17 Despite the

widespread decline in caries prevalence in permanent teeth in high-income countries over the past few decades, disparities still remain and many children in low-income families and in minority groups still develop dental caries to a greater extent.8

Gingivitis

Plaque-associated gingivitis is the most prevalent form of gingival inflammation and is caused by an accumulation of dental plaque on the tooth surface at the gingival margin.18 Plaque is a biofilm – a community of microorganisms

attached to a surface. These organisms are organised into a three-dimensional structure enclosed in a matrix of extracellular material. Dental plaque is an adherent deposit of bacteria and their products. The response to this biofilm is inflammation of the surrounding local gingival and periodontal tissue. The

presence of dental biofilm is necessary for gingivitis to occur. The intensity and duration of the inflammatory response varies among individuals and even among different teeth in the oral cavity.19 Behavioural factors play an important

causative role in periodontal disease in children and adolescents.20

Dental Care and Oral Health Status in Sweden and

Jönköping

The development of the Oral Health Preventive Programmes for Children in Sweden began during the early 1970s as a result of epidemiological information from various Public Dental Service clinics. When the oral health programmes began in Jönköping, the county had poorer oral health status than the average in Sweden.21 Through organised, systematic oral health care activities, oral

health gradually improved among children in Jönköping22 and became better

than the average in Sweden. This improvement continued until the early 1990s, when the trend stalled. One of the reasons for stalled improvement was that resources for dental care in the county decreased at the start of the 1990s, in spite of the fact that the number of children increased in the county. Reduced requirements imposed on the Public Dental Service, with reduced economic and staff resources, led to changes in the oral health organisation and clinic-based preventive programmes. However, a conscious choice was also made to reduce primary oral health preventive programmes in schools and kindergartens and to replace them with more individual treatment for patients at risk. During this period there was an increase in the number of children with foreign backgrounds, who had on average poorer oral health status compared with children with Swedish backgrounds.23

All children in the County of Jönköping take part in the same preventive programmes from one year of age or from the year of immigration to Sweden.

presence of dental biofilm is necessary for gingivitis to occur. The intensity and duration of the inflammatory response varies among individuals and even among different teeth in the oral cavity.19 Behavioural factors play an important

causative role in periodontal disease in children and adolescents.20

Dental Care and Oral Health Status in Sweden and

Jönköping

The development of the Oral Health Preventive Programmes for Children in Sweden began during the early 1970s as a result of epidemiological information from various Public Dental Service clinics. When the oral health programmes began in Jönköping, the county had poorer oral health status than the average in Sweden.21 Through organised, systematic oral health care activities, oral

health gradually improved among children in Jönköping22 and became better

than the average in Sweden. This improvement continued until the early 1990s, when the trend stalled. One of the reasons for stalled improvement was that resources for dental care in the county decreased at the start of the 1990s, in spite of the fact that the number of children increased in the county. Reduced requirements imposed on the Public Dental Service, with reduced economic and staff resources, led to changes in the oral health organisation and clinic-based preventive programmes. However, a conscious choice was also made to reduce primary oral health preventive programmes in schools and kindergartens and to replace them with more individual treatment for patients at risk. During this period there was an increase in the number of children with foreign backgrounds, who had on average poorer oral health status compared with children with Swedish backgrounds.23

All children in the County of Jönköping take part in the same preventive programmes from one year of age or from the year of immigration to Sweden.

clinic. These preventive programmes provide structured regular information and recommendations to brush the teeth at least twice a day using fluoride toothpaste. Moreover, fissure sealants of all first permanent molars are recommended in the guidelines of the Public Dental Service in the county.24

From 2 to 3 years of age through 19 years of age, children undergo regular dental examinations once a year. However, the special needs of the individual child are also taken into consideration. If a child has good dental health, there may be more than one year between examinations, while children with special needs may require more frequent check-ups. Three- to 5-year-olds are examined radiographically with two bitewing radiographs when there is proximal contact in the molar region. Unless there are special circumstances, all children from 6–19 years of age are examined radiographically (bitewing examination). In accordance with the instructions for epidemiological registrations in the county, all carious lesions are registered in all teeth and for all tooth surfaces (except third molars). In addition to registering the number of filled surfaces and extracted teeth, each tooth surface with initial or manifest carious lesions is registered. According to the instructions, caries are registered as initial if lesions have not passed the enamel-dentine border and as manifest when the carious lesions extend into the dentine.25 Based on the examination,

all children and adolescents are categorised into one of four risk categories by dentists or dental hygienists. Each child’s dental care is then managed according to an individually based treatment regimen based on risk category. In addition to the basic prevention programme, an additional programme for children and adolescents with high caries risk is implemented. This programme contains more oral hygiene information, motivation, instructions, professional tooth cleaning, strengthened fluoride prevention, fissure sealants, saliva tests and chlorhexidine rinsing.24

clinic. These preventive programmes provide structured regular information and recommendations to brush the teeth at least twice a day using fluoride toothpaste. Moreover, fissure sealants of all first permanent molars are recommended in the guidelines of the Public Dental Service in the county.24

From 2 to 3 years of age through 19 years of age, children undergo regular dental examinations once a year. However, the special needs of the individual child are also taken into consideration. If a child has good dental health, there may be more than one year between examinations, while children with special needs may require more frequent check-ups. Three- to 5-year-olds are examined radiographically with two bitewing radiographs when there is proximal contact in the molar region. Unless there are special circumstances, all children from 6–19 years of age are examined radiographically (bitewing examination). In accordance with the instructions for epidemiological registrations in the county, all carious lesions are registered in all teeth and for all tooth surfaces (except third molars). In addition to registering the number of filled surfaces and extracted teeth, each tooth surface with initial or manifest carious lesions is registered. According to the instructions, caries are registered as initial if lesions have not passed the enamel-dentine border and as manifest when the carious lesions extend into the dentine.25 Based on the examination,

all children and adolescents are categorised into one of four risk categories by dentists or dental hygienists. Each child’s dental care is then managed according to an individually based treatment regimen based on risk category. In addition to the basic prevention programme, an additional programme for children and adolescents with high caries risk is implemented. This programme contains more oral hygiene information, motivation, instructions, professional tooth cleaning, strengthened fluoride prevention, fissure sealants, saliva tests and chlorhexidine rinsing.24

The oral health situation for children in the County of Jönköping during the 30-year period from 1973 to 2003 has been described in several publications.21,26-28

According to the results of the Jönköping Cross Sectional Study in 1993,29

which also evaluated Jönköping Oral Health Preventive Programmes, 15-year-olds showed a stagnation in the number of DFS in 1993 compared with 1983 and there was also a significant increase in the prevalence of plaque and gingivitis. Moreover, it was noted that the use of professional fluoride varnish decreased between 1983 and 1993. Oral health varied considerably in different locations, however, and the percentage of 19-year-olds without proximal manifest carious lesions in 2001 varied between 49% and 69% in different areas within the county.23

The first year that questions about foreign backgrounds were included in the Jönköping Cross Sectional Study questionnaire was 1993, making it possible to study similarities and differences in dental health among subjects with foreign and Swedish backgrounds.

Dental Care and Oral Health Status in Vietnam and

Da Nang

To promote oral health and reduce the prevalence and severity of dental diseases, the School Oral Health Promotion Programme was developed and implemented in many primary schools in Vietnam. The programme began in 1982 and includes Da Nang City.

This programme consists of four components: 1. Oral Health Education Programme

2. Fluoride Mouthrinsing and Toothbrushing at School Programme 3. Early Oral Examination and Treatment Programme

The oral health situation for children in the County of Jönköping during the 30-year period from 1973 to 2003 has been described in several publications.21,26-28

According to the results of the Jönköping Cross Sectional Study in 1993,29

which also evaluated Jönköping Oral Health Preventive Programmes, 15-year-olds showed a stagnation in the number of DFS in 1993 compared with 1983 and there was also a significant increase in the prevalence of plaque and gingivitis. Moreover, it was noted that the use of professional fluoride varnish decreased between 1983 and 1993. Oral health varied considerably in different locations, however, and the percentage of 19-year-olds without proximal manifest carious lesions in 2001 varied between 49% and 69% in different areas within the county.23

The first year that questions about foreign backgrounds were included in the Jönköping Cross Sectional Study questionnaire was 1993, making it possible to study similarities and differences in dental health among subjects with foreign and Swedish backgrounds.

Dental Care and Oral Health Status in Vietnam and

Da Nang

To promote oral health and reduce the prevalence and severity of dental diseases, the School Oral Health Promotion Programme was developed and implemented in many primary schools in Vietnam. The programme began in 1982 and includes Da Nang City.

This programme consists of four components: 1. Oral Health Education Programme

2. Fluoride Mouthrinsing and Toothbrushing at School Programme 3. Early Oral Examination and Treatment Programme

Among these components, the most important is the Oral Health Education Programme, which is conducted both in class and at the dentist’s office after examination or treatment. The objective of the Oral Health Education Programme is to provide children with dental knowledge and the skills to develop appropriate attitudes, behaviours and hygiene habits in oral health care so that they can protect themselves from dental diseases such as dental caries and gingivitis after leaving primary school. This programme provides instruction on why and when children should brush their teeth, how to brush, how to choose and conserve a toothbrush and it provides information about healthy food for teeth.30 In Da Nang City, the School Oral Health Promotion

Programme has been presented to primary school children for almost 30 years (Table 1), first in urban areas and some years later in rural areas. In urban areas, the programme was developed earlier in primary schools, often with all four components offered. For schools in rural areas, the programme was not completely implemented, because of difficult economic conditions. In these regions, it was mainly the Oral Health Education and Fluoride Mouth-Rinsing Programme that functioned.

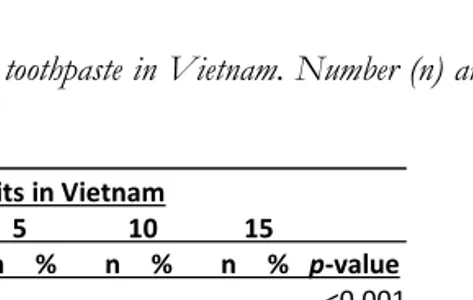

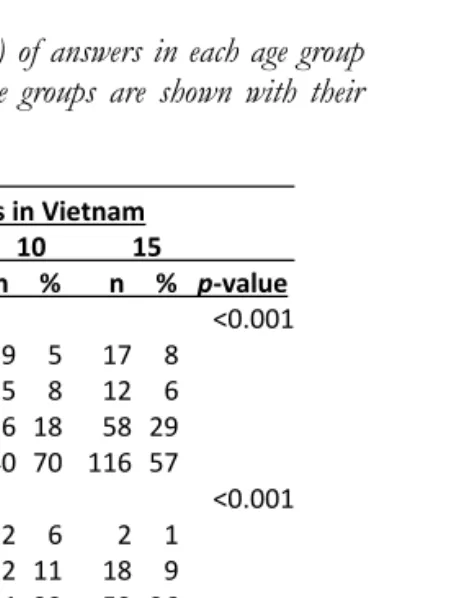

Table 1. The number of children participating in the Oral Health Education

Programme in Da Nang City in 2004,31 in relation (%) to the total number of

children.

Activities Children

n % of total Children Oral health education 74.793 100 Fluoride mouthrinsing 69.358 92.7 Toothbrushing 35.358 47.3 Examination and treatment 43.218 57.8 Sealants 1.814 2.4 Among these components, the most important is the Oral Health Education

Programme, which is conducted both in class and at the dentist’s office after examination or treatment. The objective of the Oral Health Education Programme is to provide children with dental knowledge and the skills to develop appropriate attitudes, behaviours and hygiene habits in oral health care so that they can protect themselves from dental diseases such as dental caries and gingivitis after leaving primary school. This programme provides instruction on why and when children should brush their teeth, how to brush, how to choose and conserve a toothbrush and it provides information about healthy food for teeth.30 In Da Nang City, the School Oral Health Promotion

Programme has been presented to primary school children for almost 30 years (Table 1), first in urban areas and some years later in rural areas. In urban areas, the programme was developed earlier in primary schools, often with all four components offered. For schools in rural areas, the programme was not completely implemented, because of difficult economic conditions. In these regions, it was mainly the Oral Health Education and Fluoride Mouth-Rinsing Programme that functioned.

Table 1. The number of children participating in the Oral Health Education

Programme in Da Nang City in 2004,31 in relation (%) to the total number of

children.

Activities Children

n % of total Children Oral health education 74.793 100 Fluoride mouthrinsing 69.358 92.7 Toothbrushing 35.358 47.3 Examination and treatment 43.218 57.8 Sealants 1.814 2.4

Most school dental clinics did not have enough dental materials or drill equipment; therefore, treatment was mainly extraction, calculus removal and, in some schools, filling with atraumatic restoration treatment technique.31 To

make the Oral Health Education Programme in Da Nang more effective, it needs the collaboration of school teachers, compliance in the dental care of school children, and more school dental nurses and dental hygienists who can take an active role in all of these activities.31

In 1989, the First National Oral Health Survey of the population in Vietnam was performed32 and reported poor oral hygiene status and a moderate level of

caries among a sample of 2762 individuals aged 12–15 years. In 1999, the National Oral Health Survey of Vietnam (NOHSV1999)33-34 was conducted to

characterize the oral health of Vietnamese children, and this report enabled the exploration of trends in oral health in Vietnam.35 Both urban and rural areas of

the country were included in the study. In all, 3139 randomly selected children aged 6–17 years were clinically examined for dental caries, fluorosis, calculus, gingival bleeding and periodontal problems. In addition to the examination, a questionnaire was answered by the parents of younger children and by the older children themselves. Dental caries was found to be highly prevalent and severe, but there was also considerable variation in caries prevalence among different geographical areas. The mean number of decayed tooth surfaces in the 6–7-year age group was 12.5 (standard deviation [SD] 12.8), and in the permanent dentition among 14–15-year-olds it was 3.3 (SD 4.5).35 These findings

represented an increase in caries prevalence in 1999 compared with the study performed 10 years earlier.

In 2003, oral health examinations were performed on individuals from two ethnic groups in the Central Highlands of southern Vietnam.36 Dental caries

was prevalent in both the primary and permanent dentition with high caries

Most school dental clinics did not have enough dental materials or drill equipment; therefore, treatment was mainly extraction, calculus removal and, in some schools, filling with atraumatic restoration treatment technique.31 To

make the Oral Health Education Programme in Da Nang more effective, it needs the collaboration of school teachers, compliance in the dental care of school children, and more school dental nurses and dental hygienists who can take an active role in all of these activities.31

In 1989, the First National Oral Health Survey of the population in Vietnam was performed32 and reported poor oral hygiene status and a moderate level of

caries among a sample of 2762 individuals aged 12–15 years. In 1999, the National Oral Health Survey of Vietnam (NOHSV1999)33-34 was conducted to

characterize the oral health of Vietnamese children, and this report enabled the exploration of trends in oral health in Vietnam.35 Both urban and rural areas of

the country were included in the study. In all, 3139 randomly selected children aged 6–17 years were clinically examined for dental caries, fluorosis, calculus, gingival bleeding and periodontal problems. In addition to the examination, a questionnaire was answered by the parents of younger children and by the older children themselves. Dental caries was found to be highly prevalent and severe, but there was also considerable variation in caries prevalence among different geographical areas. The mean number of decayed tooth surfaces in the 6–7-year age group was 12.5 (standard deviation [SD] 12.8), and in the permanent dentition among 14–15-year-olds it was 3.3 (SD 4.5).35 These findings

represented an increase in caries prevalence in 1999 compared with the study performed 10 years earlier.

In 2003, oral health examinations were performed on individuals from two ethnic groups in the Central Highlands of southern Vietnam.36 Dental caries

prevalence in the primary dentition associated with a high frequency of sugar consumption. Oral health studies of schoolchildren in four small rural villages in southern Vietnam were performed in 2007,37 2008,38 200939 and 2010,40

studying oral hygiene, dietary habits and dental caries in different age groups ranging from 2–16 years. In all studies, caries prevalence was found to be high, present in 93–96% of all individuals.40

Oral Health Determinants

A detailed understanding of the factors influencing oral health is necessary to deliver effective oral health promotion and prevention. These factors are known as the determinants of oral health.41 Figure 1 summarises several factors

involved in understanding changes in oral health patterns worldwide.42 Changes

in lifestyle and economic and social conditions are recognized as playing an important role in the changing oral health patterns.5 From a public health

perspective, it is also important to integrate oral health into general health and to understand how these two influences each other.43

Figure 1. Principal factors involved in changing oral health patterns worldwide. Adopted

from Petersen.42 ORAL HEALTH SYSTEMS Delivery models Financing of care Dental manpower Population-directed/ high-risk strategies

ORAL

HEALTH

SOCIETY Living conditions Culture and lifestyles Self-careENVIRONMENT Climate

Fluoride and water Sanitation

POPULATION Demographic factors Migration

prevalence in the primary dentition associated with a high frequency of sugar consumption. Oral health studies of schoolchildren in four small rural villages in southern Vietnam were performed in 2007,37 2008,38 200939 and 2010,40

studying oral hygiene, dietary habits and dental caries in different age groups ranging from 2–16 years. In all studies, caries prevalence was found to be high, present in 93–96% of all individuals.40

Oral Health Determinants

A detailed understanding of the factors influencing oral health is necessary to deliver effective oral health promotion and prevention. These factors are known as the determinants of oral health.41 Figure 1 summarises several factors

involved in understanding changes in oral health patterns worldwide.42 Changes

in lifestyle and economic and social conditions are recognized as playing an important role in the changing oral health patterns.5 From a public health

perspective, it is also important to integrate oral health into general health and to understand how these two influences each other.43

Figure 1. Principal factors involved in changing oral health patterns worldwide. Adopted

from Petersen.42 ORAL HEALTH SYSTEMS Delivery models Financing of care Dental manpower Population-directed/ high-risk strategies

ORAL

HEALTH

SOCIETY Living conditions Culture and lifestyles Self-careENVIRONMENT Climate

Fluoride and water Sanitation

POPULATION Demographic factors Migration

Understanding the factors that influence an individual’s choices and actions is important for all health professionals. With this knowledge, clinicians are more likely to be effective in supporting their patients.41

This thesis describes some oral health determinants, with a special focus on culture.

Knowledge and values

Oral health education is a planned activity that utilizes the population’s knowledge, attitudes, culture and values to promote good oral health habits. Dental health education theory suggests that although a person may be educated about a particular health behaviour, that knowledge will not influence dental health until the person positively changes the behaviour, which then becomes a habit. The values, ideas and beliefs a person possesses influence their behaviour. A person may develop knowledge and values early in life from parents, grandparents, older siblings, teachers and other influential people. Generally, knowledge and values must be changed before behaviour will change.44

In the lifestyle approach, health professionals have traditionally focused on changing the behaviours of their patients to promote health and prevent oral diseases. To focus solely on changing the behaviours of individuals is both ineffective and very costly.43 It is incorrect to assume that behaviour is freely

chosen and easily changed by everyone. Health knowledge and awareness are of little value when resources and opportunities to change do not exist.

Oral hygiene habits

Regular oral hygiene habits are associated with good oral health, while poor

Understanding the factors that influence an individual’s choices and actions is important for all health professionals. With this knowledge, clinicians are more likely to be effective in supporting their patients.41

This thesis describes some oral health determinants, with a special focus on culture.

Knowledge and values

Oral health education is a planned activity that utilizes the population’s knowledge, attitudes, culture and values to promote good oral health habits. Dental health education theory suggests that although a person may be educated about a particular health behaviour, that knowledge will not influence dental health until the person positively changes the behaviour, which then becomes a habit. The values, ideas and beliefs a person possesses influence their behaviour. A person may develop knowledge and values early in life from parents, grandparents, older siblings, teachers and other influential people. Generally, knowledge and values must be changed before behaviour will change.44

In the lifestyle approach, health professionals have traditionally focused on changing the behaviours of their patients to promote health and prevent oral diseases. To focus solely on changing the behaviours of individuals is both ineffective and very costly.43 It is incorrect to assume that behaviour is freely

chosen and easily changed by everyone. Health knowledge and awareness are of little value when resources and opportunities to change do not exist.