Gender representations of dark fictional characters:

A hermeneutic analysis of Harry Potter fan

discussions on Reddit

Student: Jason Maurer

Course: Media and Communication Studies: Master's (One-Year) Thesis-VT20 Advisor: Asko Kauppinen

Date: June 7, 2020 Word count: 17,297

Abstract

The aim of this thesis was to deepen our understanding of how audiences represent male and female dark fictional characters (DFCs) by exploring how Harry Potter fans discuss four of these characters on Reddit. Drawing on affective disposition theory as a guiding framework as well as previous investigations of gender representation and online fan cultures, I collected and analyzed 117 posts (containing 9,693 comments) about four DFCs from the Harry Potter franchise. I chose two male DFCs (Lord Voldemort and Severus Snape) and two female ones (Bellatrix Lestrange and Dolores Umbridge) for my investigation. The data were analyzed using a productive hermeneutics approach. Fans’ representation of these characters intersected with the extent which the characters’ fictionality was salient, how they were visualized, the online culture of Reddit, and fans’ presumed identification with these characters. Bellatrix was defined by her portrayal by Helena Bonham Carter in the films and her combination of valuable masculine and

feminine traits. Moreover, she was a figure of pure fantasy, which allowed fans to love her depravity. Umbridge and Snape, by contrast, were hated for intruding into the fantasy that Harry Potter offered, reminding fans of bullying and overly controlling teachers. Snape, however, was redeemed by his complexity and embodiment of geek masculinity.

Voldemort was valued for his intellect and power but also criticized as a peer failing to rise to his intellectual potential; fans at turns identified with and undercut him through humor. Taken together, the results indicate a need to qualitatively explore how DFCs are received by audiences, as it can add further nuance to our understanding of how morality and gender influence media consumption.

Keywords: fictional characters, villains, media fans, Harry Potter, Reddit, gender representation, morality

Table of Contents

List of Tables and Figures ... 5

Acknowledgments ... 6

1. Introduction ... 7

2. Background ... 8

2.1. Dark Fictional Characters, Gender Representation, and Audiences ... 8

2.2. Online Fandom and Harry Potter... 10

3. Literature Review ... 11

3.1. Overview ... 11

3.2. Gender Representation ... 12

3.3. Character Engagement ... 15

3.4. Online Fan Spaces and Harry Potter... 19

3.4.1. Fan Studies and Gender Representation ... 19

3.4.2 Representation in the Harry Potter fandom ... 21

3.5. Theoretical Framework... 23

4. Methods ... 25

4.1. Data Source: Reddit ... 25

4.2. Data Collection ... 27

4.3. Data Analysis ... 31

4.3.1. Analytical approach ... 31

4.3.2. Researcher position... 34

4.3.3. Data analysis procedure ... 35

4.3.4. Trustworthiness ... 35

4.4. Ethical Considerations ... 35

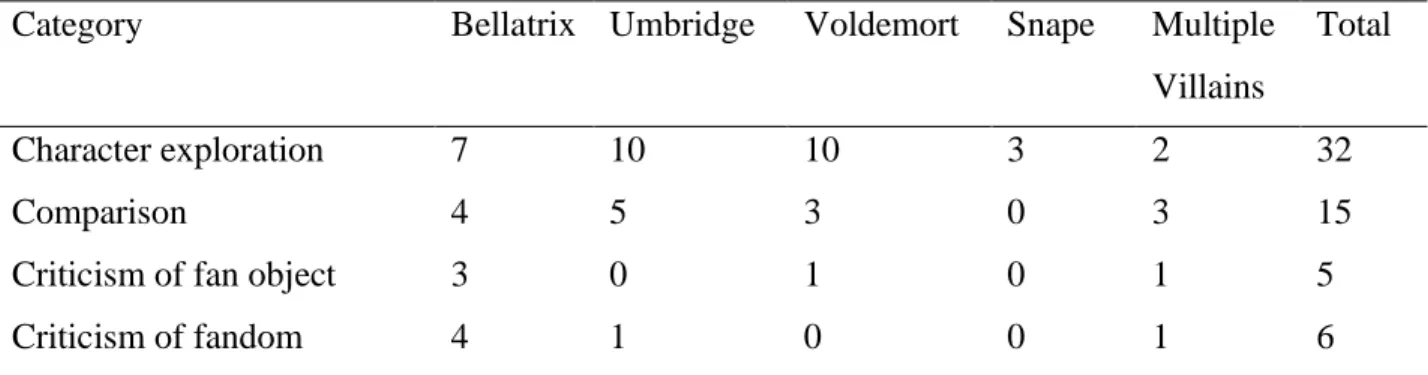

5.1. Description of Sampled Posts ... 36

5.2. The Salient Fictionality of Bellatrix Lestrange ... 38

5.2.1. Contrasting Characterization ... 38

5.2.2. Bellatrix’s Autopoetic Feedback Loop ... 41

5.3. Umbridge and Snape: Everyday Hatred ... 45

5.4. Voldemort as an Intellectual Peer ... 49

6. Conclusions and Limitations ... 52

References ... 56

Appendix A: Table of Posts... 67

List of Tables and Figures

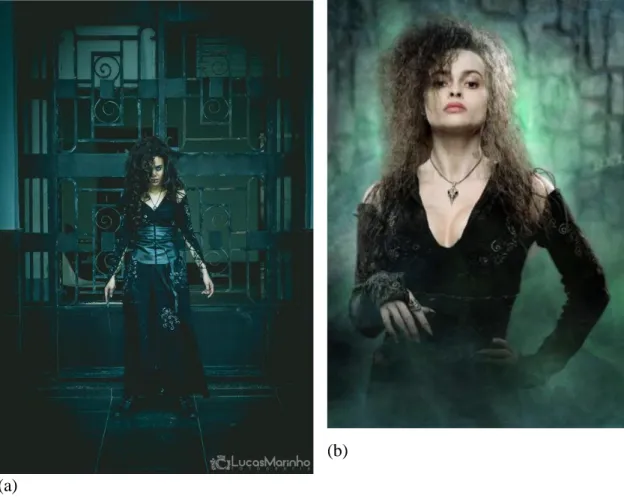

Figure 1. Timeline of release of Harry Potter books and movies (Cuntz-Leng, 2015) ... 11 Figure 2. The basic hermeneutic circle (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2009) ... 33 Figure 3. Contrasting images of (a) a cosplay photograph of Bellatrix Lestrange from /r/harrypotter and (b) a photograph of Helena Bonham Carter as Bellatrix Lestrange

(“Bellatrix Lestrange,” 2012). ... 42 Figure 4. Bellatrix cosplay photograph. This post was closed for commenting because the poster received too many sexist and harassing comments ... 43

Table 1. Definitions of post categories extracted from /r/harrypotter ... 29 Table 2. Number of posts for each category and character ... 36

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Kauppinen, for his support and advice, and in particular for introducing me to Zotero – it has saved my life in writing this thesis.

I would like to credit the original idea for this thesis – looking at how fans represent the gender of DFCs – to my friend and fellow writer, Emma.

Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Mia, for all her support and love throughout the last two months. It cannot have been easy to be quarantined with a thesis writer.

1. Introduction

Popular media centering on dark fictional characters (DFCs), including villains, antiheroes, and morally ambiguous characters (Black et al., 2019), are becoming increasingly popular: Todd Philips’ 2018 film Joker, depicting an origin story of the

murderous Batman villain the Joker, grossed over US$1 billion throughout its theatrical run (Joker, n.d.). Maleficent, the evil witch first depicted in Disney’s Sleeping Beauty in 1959, was the protagonist of two Hollywood films in the past decade. Their popularity suggests that audiences are resonating with something within their “darkness.” This thesis is an attempt to deepen our understanding of that resonance by exploring how fans – arguably the most actively engaged subsection of media audiences – construct DFCs in their online discussions. I pay particular attention to the construction of gender, which is not only a ubiquitous feature of daily life but also naturally aligns with themes of power, sexuality, violence, and morality, the distortion of which seems to characterize our most loved and hated DFCs. I frame my results in terms of affective disposition theory (ADT, Raney, 2004), which can help to explain how gender representation influences our engagement with DFCs. I was guided in this exploration by the following research question: How do fans represent male and female dark fictional characters from Harry Potter in their discussions on Reddit?

Understanding how audiences’ connection with DFCs intersects with gender representations provides us with a deeper knowledge of how fictional men and women are treated by audiences. For the media producers creating these characters, such knowledge could help them create better, more engaging characters that stay with audiences past the moment of consumption. For scholars, such knowledge would open a much wider area of investigation into how fictional men and women influence, and are influenced by, our conceptions of morality.

The structure of this thesis is as follows. Section 2 contextualizes my investigation through an overview of DFCs, gender representation, and the Harry Potter fandom. Section 3 outlines past literature and theory on gender representation, character engagement

(particularly ADT), and fan studies, and brings this together under an actionable framework that helped guide my analysis. Section 4 discusses the data source (Reddit), data collection

method, and data analysis method. Section 5 shows the results of my hermeneutic analysis and discusses these results in the context of theory. Section 6 concludes with a summary of the knowledge I have generated and directions for future research.

2. Background

2.1. Dark Fictional Characters, Gender Representation, and Audiences

DFCs are wildly popular and influential: Bela Lugosi’s portrayal of the vampire Dracula in 1931 defined the character for generations (Nuzum, 2008); Lord Voldemort, the main villain of the Harry Potter series, has been invoked in analyses of prominent political issues, such as the War on Terror in the 2000s (Turner, 2005) and in relation to the dangers of media consolidation (Slack, 2007); and Darth Vader, the iconic villain of the original Star Wars trilogy, has a species of beetle named after him (Young, 2014). Beyond these large-scale examples are countless everyday ones: In an interview I conducted for a research methodology exam at Malmö University (Maurer, 2020), the interviewee

mentioned invoking DFCs as exemplars of how not to act: “So if I have a friend having this issue or that issue, I say… “I mean, think of it like this, you know this character is doing that.” And oftentimes I will point to a villain, and say “He’s/she’s being Bellatrix

[Lestrange].1 Would you marry Bellatrix?” However, in that same interview, the

interviewee expressed a deep enjoyment of the very qualities that he was ostensibly

referencing here – Bellatrix’s wanton disregard for moral standards. His response illustrates the complexity of how audiences engage with DFCs – we may simultaneously hate them, love them, want to see more of them, and find them illustrative of larger truths.

This complexity is what I believe makes DFCs such interesting representations. But what exactly is meant by “representation”? According to Hall (2013), a representation is basically how we language to create meaning. The meaning created is not a fixed process of the language or of the world, but is constructed by members of a culture: “It is us – in society, within human cultures – who make things mean, who signify” (p. 45). Following this constructivist approach, which Hall (2013) links to the work of Foucault, Barthes, and Saussure, representations are in constant flux across time and culture. They are the sites of

negotiation of “truths” about the world, so examining them can tell us something about how society understand the concept or object being represented.

What do DFCs tell us about ourselves and about our society? There are myriad possible answers. DFCs are both illustrative and taboo; they are metaphorical car crashes that disgust us but still draw a crowd. Our moral principles and the monitoring thereof should reject them as uniformly loathsome, and yet we may discount these failings in the name of enjoyment (Raney, 2004). Teasing out exactly why we have such conflicting reactions to DFCs can reveal what we understand about those darker parts of our lives. To begin to understand the representation of DFCs, both in media texts and among audiences, we must look at the features of those characters that are most salient in our lives. In this thesis, I pay attention to gender.

Gender is our socially constructed understanding of sex-linked differences – the roles, attributes, and behaviors that we learn to assign to binary categories of “masculine” and “feminine” through social learning (Amason, 2012). The way gender is represented in media has been a particularly active area of investigation over the past few decades, often with attention to how certain constructions of masculinity and femininity are privileged and others denigrated (Armstrong, 2013; Gallagher, 2013), whether it be in news, TV shows, films (Armstrong, 2013), or books (Underwood et al., 2018). For instance, women are more likely to be invisible, portrayed as stereotypically feminine (Sink & Mastro, 2017) or violently murdered on TV (Guerrero-Pico et al., 2018), while they are more likely to be hypersexualized in action films (Heldman et al., 2016). Men, by contrast, tend to be depicted as aggressive, domineering, and promiscuous (Sink & Mastro, 2017).

Studying media representations of gender is important for understanding how masculinity and femininity are constructed in society; however, to fully understand “when gender matters” (Hermes, 2013, p. 62), we also have to look at how audiences reproduce and transform gendered facets of everyday living. According to Hermes (2013),

“Qualitative audience studies have arguably been the best possible expression of feminist engagement in media studies” (p. 61) in part because they help us understand “unequal gender relations without imposing ideological dogma or political correctness” (p. 61). Feminist audience studies have also helped to elevate popular culture as a viable area of study (Hermes, 2013), making it quite natural to explore fictional characters, and DFCs in

particular, qualitatively from a feminist approach. Such studies can bring us closer to understanding the meaning these characters have in our lives and how their gendered representations play a role in the creation of that meaning, as well as how we challenge those representations.

2.2. Online Fandom and Harry Potter

The ways in which audiences engage with media representations is perhaps best exemplified in studies of popular culture fans and fandoms. According to Lanier and Fowler (2013), fans “they creatively (re)produce culture, thus contributing directly to societal discourse” (p. 284). Fans’ unique forms of engagement with media texts,

particularly creative outputs like fanfiction, and the strong affective attachment they exhibit towards particular media texts arguably makes them a uniquely extreme subset of a broader audience, but as Jenkins (2012) noted, “there is no sharp division between fans and other readers” (p. 54). Thus, studying fans can help us in delineating the many articulations of how audiences construct gender. Indeed, although fans are arguably bound by their shared love of a text, this does not mean that they share ideologies or even interpretations of the same text (Jenkins, 2012; Kustritz, 2015). In fact, contestation is a key fan practice through which they “[make] sense of the world through felt and shared experiences” (Lamerichs, 2018, p. 19). For that reason, their discussions about fictional characters are a rich vein of meaning through which we can begin to understand audiences’ reception of DFCs.

Nowadays, the sheer number of fandoms forces scholars to narrow their focus to avoid being buried in data. This is especially true since the advent of the internet, which has made fandoms more accessible as well as changed the ways in which fans discuss and perform their affective connection to media texts (Lanier & Fowler, 2013). The Harry Potter fandom has presented scholars with an important site through which to explore the role of digital technology in fandoms, both because the original books were being published “as the internet shifted to Web 2.0” (Walton, 2018, p. 234) and because the online fandom is immense: Harry Potter has the most stories on fanfiction.net, at over 819,000 (just under four times that of Twilight, at 220,000). Moreover, the fandom remains highly active. The Harry Potter fandom has had an enduring impact on online fandom as a whole, being a progenitor of many practices common to fandom today, such as podcasting, blogs, and

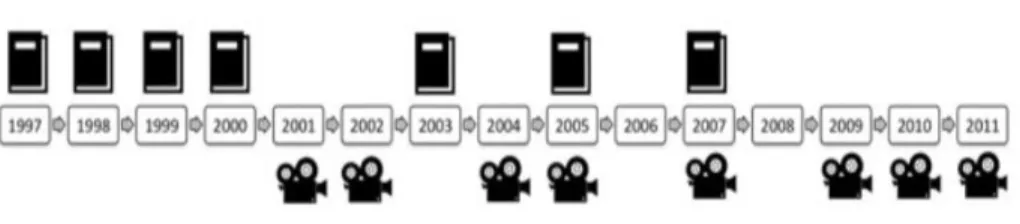

beta-reading (Jenkins, 2011). Moreover, given that the books were released alongside the movies (see Figure 1 for a timeline), Harry Potter provides a unique look into how fans integrate and make sense of texts across different media, particularly how they integrate the different portrayals of a character into a unified image (Cuntz-Leng, 2015). For these reasons, it is an ideal fandom to explore fan cultures and practices and the impact of fandom on the media landscape.

Figure 1. Timeline of release of Harry Potter books and movies (Cuntz-Leng, 2015)

The Harry Potter fandom is also ideal for studying the gender representation of DFCs, since the original text has so many: Lord Voldemort, the nearly immortal dark wizard responsible for the deaths of Harry Potter’s parents and much of the conflict over the course of the books; Severus Snape, a morally ambiguous teacher who troubles Harry’s school life but offers aid when needed; Dolores Umbridge, who imposes dictatorial rule over Hogwarts in Harry’s fifth year; and Bellatrix Lestrange, a dark witch with a fanatical devotion to Voldemort and his cause, to name just a few. In this thesis, I aimed to

understand how fans of this transmedia franchise construct these four DFCs in their discussions on the fan subreddit /r/harrypotter.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Overview

To make sense of how fans construct gendered representations of DFCs, I outline past research on how gender representations in media and how audiences engage with fictional characters. From there, I move into research on fans and the online space in which

they actively engage with media representations, particularly the Harry Potter fandom. Finally, I combine these research areas in my analytical framework.

3.2. Gender Representation

Studying gender representation in media can help illuminate how we ideologically construct women and men and dictates their meaning and place in society. Early feminist scholars – most notably Gaye Tuchman and her colleagues – were preoccupied with the representation of women and to what extent their presence and experiences in reality were reflected in media (Gallagher, 2013). In their seminal book, Hearth and Home: Images of Women in the Mass Media, Tuchman, Daniels, and Benet (1978, as cited in Armstrong, 2013), showed that women were “symbolically annihilated” in popular television programs and the news – that is, underrepresented and deprived of agency, being cast as housewives or in subordinate positions to males. In being rendered “invisible”, they were deprived of their ability to share their experience and made mere symbols of the “biases and

assumptions of those who define the public—and therefore the media—agenda” (Gallagher, 2013, p. 23).

Gallagher (2013) notes that these early feminist scholars focused on the representation of middle-class white women; thus, they failed to acknowledge the intersectional nature of discrimination against women (Crenshaw, 1991) and seemed to “assume that the representation of men’s experience was unproblematic” (p. 24–25). Still, their work provided a strong foundation for further work. Moreover, subsequent research has confirmed many of the observations of early scholars in television (Daalmans et al., 2017; Downs, 1981; Sink & Mastro, 2017), films (Fischer, 2010; Hoerrner, 1996; Lauzen, 2015; Neville & Anastasio, 2019), and news media (D’Heer et al., 2020). For instance, Hoerrner (1996) content analyzed representations of Disney film characters and found that only 21% of the 134 characters she examined were female. In a study of portrayals of gender on primetime television series, Sink and Mastro (2017) found that women are not only underrepresented but they also exhibit more gender-stereotypical characteristics (i.e., are family-oriented and likeable); moreover, men continue to exert dominance over women. However, representations of women and men have changed since the 1970s. Neville and Anastasio (2019) noted that in popular U.S. films in 2016, women were more likely to

occupy positions of occupational and social power compared to films released in 2002. Similarly, Baker and Raney (2007) found that, in children’s superhero television programs, there were few clear instances of gender-stereotypical behavior. However, in both studies, women were significantly underrepresented.

Added to these findings are notions of sexualization and objectification, or the reduction of women into collections of pleasurable body parts meant for male consumption, which rose to prominence with the work of Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon in the 70s and 80s (Nussbaum, 1995). In her seminal essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Laura Mulvey (1989) writes: “women are simultaneously looked at and

displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness” (p. 19). She describes the tendency for women to be displayed in such a manner for consumption by men as “the male gaze.” The male gaze has had an enduring impact on feminist media theory and it remains relevant because women are still often defined by this “to-be-looked-at-ness”: they are more likely to be sexually objectified, which manifests in terms of how their bodies are depicted (e.g., thinner body types, camera angles) and the (lack of) clothing they wear (Heldman et al., 2016; Sink & Mastro, 2017). Attention has also been paid to masculinity – as Sink and Mastro (2017) note, both women and men tend to be represented in terms of exaggerated forms of masculinity and femininity (so-called “hypermasculinity” and “hyperfemininity”) in media. The former is based on the tendency to display aggression and dominance and the latter to display submission and sexualization.

However, the abovementioned foundational studies did not explore specific character types (e.g., DFCs). The representation of DFCs has been attended to in literary studies, such as Aguiar's (2001) in-depth Jungian analysis of the “bitch” (“…that vital woman, empowered with wit, anger, ruthless survival instincts…”, p. 1). She claims that these characters tend to be stereotyped in male- and female-authored fiction as either noble angels or sensuous devils lacking in purpose. However, her focus on archetypes leaves little room for nuance and she is not concerned with media beyond literature.

This literary perspective is joined by research on “the violent woman” and “female action leads” in film and television, such as Heldman et al.'s (2016) content analysis of the ways in which female action heroines in films have “devolved” into hypersexualization

since the 1960s. Heldman et al. (2016) notes that their depiction often reinforces notions of “women’s second-class social status” (p. 3), including inferior physicality, presenting toughness or strength as a “sin” to be rectified through self-sacrifice, and, most notably, hypersexualization (which they operationally define as “‘scantily clad’, partially or fully nude, and/or presented as ‘sexualized body parts’ through selective camera angles”, p. 4) and objectification. This sexualization has been criticized as disempowering because it undercuts the character’s symbolic threat of male dominance (Arons, 2001) and because of its potential to harm the health (mental and otherwise) of women (Heldman et al., 2016). However, the focus of these studies on action leads – who are morally ambiguous at best – means that we cannot generalize their results to less moral characters who do not occupy the limelight.

As for the representation of men and masculinity, violence, dominance, and power have been seen as more prototypical, along with toughness (which is valorized as opposed to denigrated), an emphasis on achieving goals and problem-solving, and an adherence to rationality and a rejection of emotion (Fejes, 1992; Hodkinson, 2017). Citing Fiske, Hodkinson (2017) notes that these images may be considered less as reflective of men’s experiences and more as “unrealistic fantasies when compared to the lack of independence, control or power which characterizes most ordinary men’s lives” (p. 257). This hegemonic masculine representation is also open to sexualization, assuming a straight female or gay male gaze (Hodkinson, 2017), which may negatively impact men (Hobza et al., 2007). However, other forms of masculinity have risen to prominence as well, particularly in the context of geek media (“geek masculinity”) – these masculinities place less emphasis on physical power and more on intellectual power but also can be characterized as an example of “failed masculinity” (Blodgett, 2020).

Overall, past literature clearly indicates the importance of gender representation in media. Besides affecting how we view ourselves and our bodies, the quality and diversity of representations may influence the possibilities we feel are available to us in navigating our lives, to what extent we feel heard and understood in the cacophony that makes up modern society, and how we view and treat others. As Sink and Mastro (2017) write: “the definition of women provided by mass media content holds social significance” (p. 5). I would argue that the same is true of the definition of men. If we fail to consider

representation, no matter whether it is at the level of the popular culture or reactions to that culture (as in audience studies, which I will turn to next), then we will ultimately fail to understand and correct the vast power imbalances that we see across not only gender, but also class, race, sexuality, ableness, and other demographic strata.

3.3. Character Engagement

Research on gender representation in media has often focused on the media texts, applying feminist theory and content analysis to deconstruct how women and men are portrayed. This fails to capture the other side of representation – that is, the work of audiences in constructing, interpreting, and otherwise engaging with representations. Scholars have long since discounted the “passive and receptive” audience conceived by early media theorists (e.g., the Frankfurt school; Hodkinson, 2017) and have more or less accepted that audiences are active interpreters of mediated messages (Hall, 2013). This understanding has produced a considerable amount of insightful research on how audiences interpret and engage with media texts, including the fictional characters populating these texts.

The particular strain of audience studies examining character engagement has been located at the intersection of film studies and psychological research. These studies were primarily concerned with processes by which audience members come to enjoy fictional characters in films and television shows. Arguably the most important theory of this tradition is affective disposition theory (ADT). Initially conceived by Zillmann and Cantor (1972, as cited in Raney, 2004), and later expanded by Raney (2004), ADT explains how we come to like and enjoy characters in film/television. Its original incarnation proposed that audiences come to like or dislike (i.e., form affective dispositions toward) characters based on their specific conception of morality – that is, audiences tend to like characters that they consider to be moral and dislike characters they consider immoral (Raney, 2004). When these liked characters experience positive outcomes in the narrative, the audience member experiences enjoyment; by contrast, when the liked characters experience a negative outcome or a disliked character a positive outcome, audiences’ enjoyment may suffer (Raney, 2004).

However, Raney (2004) pointed out that this is far too simplistic a theory to explain audiences’ actual feelings and behaviors in connecting with fictional characters. For

instance, it cannot explain enjoyment of morally ambiguous characters (i.e., characters who engage in distinctly immoral behaviors but for ultimately moral ends) or villains – we should dislike these characters because they violate our conceptions of morality. Yet like them we do. Raney (2004) offered a modified version of disposition theory to explain this problem: he posed that liking may sometimes precede moral judgment, such as when we expect a character to behave a certain way or we are more naturally aligned with that character’s personality. Accordingly, when a liked character behaves immorally, we use moral disengagement (a concept springing out of psychological research on group formation; Raney, 2004) to continue liking and enjoying the character. Moral disengagement describes the set of strategies by which we turn off our more or less constant “moral monitoring” of our environment, such as moral justification (deeming the moral violation to be a necessary or appropriate response to the situation), minimizing harm (downplaying the harmful effects of the violation), and dehumanization (depriving the victims of humanity and agency).

Subsequent research has provided support for this expanded theory (e.g., Krakowiak & Tsay-Vogel, 2011, 2013; Sanders & Tsay-Vogel, 2016). Krakowiak and Tsay-Vogel (2011) conducted an online post-test study of 312 students and found that Raney’s (2004) version of ADT was supported: liking mediated the relationship between moral

disengagement and enjoyment of a narrative about a morally ambiguous character, indicating that to like such characters, individuals must engage in some form of moral disengagement. They expanded on this in a later experiment (Krakowiak & Tsay-Vogel, 2013) and found that, in line with ADT, moral disengagement mediated the positive effects of character motivation and outcome on their evaluation of the characters’ attributes, which in turn influenced how much they liked the characters. Both these studies clearly supported that moral disengagement is involved in how people relate to fictional characters with undesirable qualities (e.g., selfishness)2. However, neither study examined why we connect

with some characters and not others – we do not like all DFCs, after all. Some are

undoubtedly more appealing or interesting to audiences than others and we are not necessarily driven to like and morally disengage with all of them.

To explain in part why we connect better with some characters, researchers have looked to the concept of identification. Cohen (2001) defines identification as an

“intermittent feeling” of imagining oneself as being that character and temporarily adopting their identity (p. 250), thereby more directly experiencing the narrative. Drawing on this definition, Sanders and Tsay-Vogel (2016) investigated how it factored into the ADT framework by surveying a student sample of Harry Potter fans and found that identification and moral judgments (i.e., how moral a given character was perceived as) predicted to what extent people morally disengaged from a character in the text, indicating that identification fits into ADT as well. They did not, however, fit character liking into their model, so it is not entirely clear from their results how identification affects liking or enjoyment.

Nevertheless, considering the findings of earlier studies (e.g., Krakowiak & Tsay-Vogel, 2011), both may be involved.

There are problems with this line of research. Character engagement researchers like Raney (2004) and Sanders and Tsay-Vogel (2016) are firmly entrenched in a positivist paradigm (Blaikie & Priest, 2017) – their aims are to elucidate the psychological

mechanisms involved in how people enjoy and engage with fictional characters at the moment of exposure. Cohen’s (2001) definition of identification, while widely used, suffers from the same problem: he stresses that this is a “fleeting” sensation that occurs “during exposure to a media message” (p. 250), which would suggest that it can only occur while we are consuming a given media text. However, such studies cannot explain much beyond that moment – why some members of the audience continue to like and engage with characters long after they have consumed the media text. Relatedly, the focus of these studies (and ADT) on narrative enjoyment – which is typically defined in terms of hedonic pleasure (Tamborini et al., 2010) – as an outcome precludes our understanding of how affective dispositions, moral disengagement, and identification relate to engagement with characters outside the narrative context. Are these processes more enduring features of our relationship with a given character that play out in other modes of interaction with fictional characters across different mediated environments? Ultimately, I think that ADT could be useful for reliably predicting engagement with DFCs beyond narrative enjoyment because

it encapsulates why we connect with these characters; it seems a natural extension to add specifics about how we connect with these characters. It may be a matter of extending the definition of enjoyment beyond mere pleasure, such as satisfying various needs (e.g., to connect with others; Tamborini et al., 2010). It is also worth expanding ADT’s application to other forms of media – it was conceived and expanded to explain attachment to

characters in films and television (Raney, 2004). There is thus a lack of understanding of how it applies to character engagement in a transmedia context.

The use of positivist methodologies in these studies also limits our understanding of audiences’ own language and experiences of character engagement, which links back to representation: how do audiences themselves construct these characters (particularly in terms of gender) and how do these constructions interact with their affective dispositions, engagement, etc. towards these characters, particularly DFCs? Gender has been to some extent addressed in studies of character engagement, albeit mostly from a media effects perspective and focusing on children (e.g., Eyal & Rubin, 2003; Lonial & Auken, 1986). These studies found that audiences seemed to identify more strongly with same-gender characters than with opposite-gender ones, although this difference is less apparent among adults (Lonial & Auken, 1986; Meyer, 2009). However, these studies used quantitative methods and focused on breaking down antecedents and consequences of character engagement, without giving consideration to the social realities being constructed by audiences. Moreover, they did not consider the moral dimension so intrinsic to DFCs. I did find a qualitative study in this tradition (Meyer, 2009), which examined how violent female characters in film are interpreted by audiences. Meyer (2009) found that these characters were praised for exhibiting more feminine traits and condemned for their use of violence – thus, dominant gender ideology was essentially reproduced by audiences in their

interpretations of violent women. Unfortunately, Meyer’s (2009) study is only applicable to film characters and took place in a controlled environment, meaning that it could not capture audiences’ natural discourses in interpreting characters.

The lack of qualitative research on character engagement, particularly using a feminist approach, may reflect a broader trend that feminist audience research is becoming increasingly less visible in the literature (Cavalcante et al., 2017). Still, this does not mean

it is not being conducted. In fact, character engagement, representation studies, and audience research naturally meet in fan studies.

3.4. Online Fan Spaces and Harry Potter

3.4.1. Fan Studies and Gender Representation

Fan studies arose out of audience research in the 1980s and 1990s, with Ang’s (1985, as cited in Lamerichs, 2018) study of Dallas fans being cited as one of the first fan studies. It exploded as a field with the works of Henry Jenkins and Camille Bacon-Smith on science fiction fan conventions (Lamerichs, 2018). These studies established the qualitative tradition of fan studies. They also established the tradition of examining the creative works fans base off of their favored texts, particularly fanfiction (Jenkins, 2012). The development of the field since, as Lamerichs (2018) notes, has been “highly

interdisciplinary” (p. 15), particularly as fan cultures have moved online: some researchers continued in the vein of Jenkins (2012) by taking a ethnographic approach in a particular fan community (see, for example, Baym, 2000), whereas others began applying literary and textual analyses to fanfiction and the discussions surrounding these texts (e.g., Scodari & Felder, 2000) in order to explore what the original texts mean to fans and how fans play with these texts (Hellekson & Busse, 2006).

Fans offer unique insight into how audiences interact with media texts because of the prominence and enthusiasm of their connection to these texts. Arguably what defines a fan – or at least what makes them an interesting subset of the audience to explore – is an affective commitment to a media text (Lamerichs, 2018; Lanier & Fowler, 2013). “Being a fan is an experience that is grounded in feeling – an admiration of texts that are used to connect to others and the world itself” (Lamerichs, 2018, p. 18). They are consumers and producers, which Lanier and Fowler (2013) note does not necessarily involve “the creation of an artifact, but encompasses the creation of value and meaning” (p. 285). Lamerichs (2018) argues that fans’ affectivity is often evident in their performance and social communications, which would suggest that their spaces – both offline and online – are primarily emotional ones, wherein fans can play out their attachments to the texts and complain about disruptions to textual integrity (Milner, 2010). Expressions of attachment

are not always emotional – fans may also “maintain a critical distance” to apply more reasoned aesthetic judgments (Lamerichs, 2018, p. 19).

Feminism has a long tradition in fan studies, with early fan scholars believing that fanfiction was written mostly by women (Stanfill, 2020). Fanfiction and fan discussion is where gender representation has been primarily located in fan studies – particularly in the context of “shipping” (pairing characters romantically, Walton, 2018) and “slash” (i.e., shipping characters of the same sex; Allington, 2007). As might be expected given the sheer diversity of fan communities, particularly online ones, gender is constructed quite differently across fanworks and fan discussions, ranging from the resistant to the normative (Kustritz, 2015; Stanfill, 2020). For instance, in their exploration of Bronies (fans of My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic), Hunting and Hains (2019) found that male fans

reproduced traditional gender hierarchies in discussions by denigrating women’s and girl’s media through the use of masculinized discursive practices, including the application of masculine taste norms. Miller (2018), operating within the same fandom, conversely found that men constructed a form of “discordant masculinity” through their textual engagement that was ultimately progressive. The focus of these studies, however, privileged

protagonists (Kustritz, 2015; Wills, 2013) or did not examine specific characters (Hunting & Hains, 2019). To my knowledge, fan scholars have not examined the gender

representation of DFCs.

The diversity of fan spaces makes prediction of discourses on character

representation difficult, which may explain the conflicting portrayals of fandom as largely progressive or largely reactionary (Lanier & Fowler, 2013). The digital revolution has only made this more apparent. While early studies of online fandoms dealt with small private online spaces and employed ethnographic approaches to understand the cultures of these “pocket realities” (Scodari & Felder, 2000), as fandoms grew and digital technology became more integrated with social life, these realities became much more trafficked and far less distinct. Fan texts are now more widely disseminated and fans’ impact on media texts is far greater than ever before (Lanier & Fowler, 2013). Perhaps as a result, fan scholars have limited their focuses to specific fan spaces and fandoms; not doing so risks information overload.

The digitalization of fandom has not been without its problems. The anonymity of online fan spaces has allowed for the proliferation of toxic practices and discourses – much of which is racist, sexist, and homophobic (Guerrero-Pico et al., 2018; Massanari, 2017). One high-profile event solidly rooted in fandom is the 2014 #Gamergate incident, in which video game fans launched a coordinated campaign of harassment against female game creators and critics across multiple sites (e.g., Reddit, Twitter, 4chan). This and other sexist harassment campaigns have been attributed both to the anonymity-afforded disinhibition of online spaces and, at least in the case of geek media, the perceived threat of these female fans to male fans’ construction of masculinity (Blodgett & Salter, 2018; Massanari, 2017). Accordingly, online fan spaces are fraught with conflicting ideologies. The sites of such ideological contestation are no doubt the very activities that define fandoms – their engagement with the media texts, including their discussions about DFCs.

Researchers interested in online fan communities have also privileged so-called “cult fandoms” wherein fans “manifest a great degree of involvement and expertise on the products on which they comment” (Lacalle & Simelio, 2017, p. 449). The focus on these active communities, while helpful in understanding how fans co-opt and reconstruct media texts, gives us less of an indication of how more “spontaneous fans” participate in these communities and how the online platform’s affordances encourage certain types of

communication (Lacalle & Simelio, 2017, p. 452). Arguably, the openness and anonymity of popular social networking spaces – such as Reddit or Twitter – lowers the threshold for participation, giving researchers access to a broader range of fan perspectives on media texts (and hence the characters within them). Conversely, LiveJournal communities may be more closed (or perceived as such) and focused on creative production (e.g., fanfiction; Hampton, 2014), thus raising barriers to entry and making communications more intimate. For that reason, it seems necessary for researchers to expand their study of fandoms to more open online spaces.

3.4.2 Representation in the Harry Potter fandom

Many scholars have explored fans’ representations of Harry Potter characters, particularly in terms of gender and sexuality, through close readings of slash fanfiction and ethnographic study of fanfiction communities (e.g., Duggan, 2017; Hampton, 2014;

Kustritz, 2015). For instance, Kustritz (2015) examined fans’ views on feminism and gender roles through their representation of non-canonical relationships between Hermione Granger and Severus Snape, two main characters from the series, in a Harry Potter

fanfiction community. Walton (2018) examined how fans reproduced, rather than

contested, heteronormative ideology in their discussions about whether Hermione should end up romantically involved with Harry or his best friend, Ron Weasley. Popple (2015) examined how Muggle Quidditch players3 struggled to enact and preserve the gender

equality of the game represented in the books.

Still, Harry Potter research has a number of important gaps. First, there is surprisingly little research on the DFCs. Severus Snape, arguably the most morally ambiguous character in the series, has received some attention in terms of engagement (Alderton, 2014; Cuntz-Leng, 2015). However, more villainous characters (e.g., Lord Voldemort, Bellatrix Lestrange), whose actions are less redeemable, also require

examination because they are, according to ADT, less likeable and their actions are harder to justify. Second, the transmedia nature of Harry Potter has not been much considered. Cuntz-Leng (2015) attempted to do so by positing an “autopoetic feedback loop” in the portrayal of Snape. She proposed that Snape’s portrayal across the books, films, and fanfiction gradually blended over time into a uniform image of the character. This interesting phenomenon is, however, marred by a lack of description of her methods and data sources. Expanding on this feedback loop would be valuable for helping us better understand how characters blend (or not) across different media. Finally, Harry Potter fan studies have typically neglected the possible impact of platform on how fans discuss characters. These studies have examined discussions in more private fan spaces, such as Walton’s (2018) focus on Harry Potter websites, or ignored platform (e.g., Alderton, 2014). It is problematic to assume that platform does not affect how characters are discussed, particularly public platforms like Reddit or Tumblr. Reddit, despite being made up of a vast array of differing subcommunities (subreddits), may attract people with particular discourse styles (Massanari, 2013; Shelton et al., 2015). As such, it is necessary to consider the platform context when examining fan discussions.

3 Quidditch is a magical game played on broomsticks; Muggle Quidditch is a version of the game played in

This thesis represents an attempt to address these gaps in the literature. In other words, it is an attempt to better understand gender representation in fandom and expand character engagement theory through qualitative methods while focusing on a unique public online fan space.

3.5. Theoretical Framework

This thesis lies at the nexus of character engagement studies, studies of gender representation, and fan studies, bound together under a general framework of ADT. I chose ADT as the overarching framework in spite of its current applicability to primarily visual media because it offers a way of marshalling these somewhat diverging traditions for a clear analytical purpose.

ADT posits that the way we feel about a character – to what extent we like them or not, which is likely to be affected by countless different factors (including how much we identify with them, our exposures to similar past characters, etc.) – influences how we morally position ourselves in relation to that character, which in turn influences our enjoyment of their behaviors and outcomes. What connects a character to an audience member is therefore grounded in affectivity and an understanding of what is good or bad (Raney, 2004). ADT therefore seems a particularly useful way of understanding fan connections with DFCs because fans are more or less defined by their strong affective engagement with a media text (Lanier & Fowler, 2013). The theory’s basic tenets can help in interpreting how fans treat the DFCs of Harry Potter by orienting me towards the nature of these affective connections (not just whether they like, hate, etc. a character, but whether they identify with that character or relate that character to some aspect of their lived

experience beyond identification) and how the most salient feature of DFCs – their immorality – plays into fan constructions of these characters. Moreover, while ADT does not explicitly account for how gender representations interact with engagement with fictional characters, it does allow us to speculate on this through its consideration of identification in character liking; in other words, it offers a useful template on which to build. Overall, ADT offers a good structure for interpreting the wealth of information contained within fan discussions.

Another reason for choosing ADT is that that it is in dire need of further nuance. Despite work done by Raney (2004) and others to empirically support the theory, it remains overly simplistic and somewhat limited in scope because previous studies based on the theory used primarily quantitative methods. First, it assumes an overly general audience who bring to their consumption experience a set of moral principles that they would apply in reality; it does not clearly account for the possibility that audiences may have distinct moral principles depending on the genre (fantasy and science fiction in particular, given the extent to which they offer a “subversion of human norms”; Leavenworth, 2014, p. 40). This is not a weakness per se; in fact, ADT’s reliance on a quantifiable definition of morality (e.g., care, purity, Eden et al., 2015) is partly what allows for researchers to make

generalizations about audience responses to fictional characters. Nevertheless, in showing that to apply unique moral principles to DFCs, I might offer researchers knowledge on which to build more specific quantitative measures of morality for fictional characters. Second, ADT only applies to the moment of consumption and does not explain how audiences carry their feelings and understanding into other forms of character engagement. Third, it does not account for how the characteristics of the character, particularly gender, may affect audiences’ dispositions. This latter point is important because it would allow us to more clearly understand how gender representations influence affective dispositions and moral disengagement. Finally, it has been strictly applied to film and television, and does not clearly cover transmedia properties. Overall, research using qualitative methods would go a long way towards bolstering and expanding the theory for use in subsequent research.

My thesis, therefore, represents a novice’s attempt at fleshing out this theory through qualitative methods. First, I focus on a subsection of the audience demonstrating lasting engagement with a transmedia text (Harry Potter fans). Second, I draw on literature from gender representation to elucidate how specific elements of ADT – particularly affective engagement and morality – interact with the characters’ “to-be-looked-at-ness” (Mulvey, 1989), masculinity/femininity, power, violence (Meyer, 2009), and more. Finally, I draw on online research of public platforms relevant to fans (e.g., Massanari, 2017) to contextualize fans’ discussions of DFCs as occurring within a relatively masculinized platform (Reddit).

4. Methods

4.1. Data Source: Reddit

The data for this thesis were taken from a subreddit of the popular social news site Reddit, which styles itself as the “front page of the internet.” Created in 2005 by

entrepreneurs Steve Huffman and Alexis Ohanian (Fiegerman, 2014), Reddit has grown into one of the most trafficked websites worldwide, fourth only to Google, Facebook, and YouTube in 2018 (Marantz, 2018). The site is generally referred to as a “social news site,” thereby differentiating it from social networking sites like Facebook, which are primarily for meeting and connecting with other users. Reddit users (redditors) create their own communities (subreddits) around almost any area of interest and post links pertaining to those interests. As an open-source platform, redditors have considerable control over subreddits – they can even download and rewrite the entire codebase (Massanari, 2017). Within subreddits, redditors can comment on posted content and vote on that content. They may upvote posts or comments that they agree with or enjoy, which makes the post more visible in searches and front pages; downvoted content is made less visible. Upvotes and downvotes are aggregated into a score for each link or comment, which contributes to a redditor’s “karma” score – their contribution to the Reddit community (Massanari, 2017).

Subreddits are mostly managed by volunteer moderators; site administrators take an extremely hands-off approach. Accordingly, Reddit has a reputation for hosting off-color and often odious content. For example, it was a primary site for “The Fappening” (where over 100 female celebrity nude photographs were leaked) in 2014 (Massanari, 2017). Because of Reddit’s relative anonymity and the fact that users can create multiple accounts and reform banned subreddits under different names (see Massanari, 2017, for examples), racist and sexist content continues to proliferate on the site. Despite its reputation, Reddit remains popular, particularly among young men (Herring & Stoerger, 2014; Reddit Statistics For 2020, 2019). Massanari (2017) notes that “Reddit’s most popular subreddits and general ethos tend to coalesce around geek interests—technology, science, popular culture (particularly of the science fiction, fantasy, and comic book variety), and gaming” (p. 331). Fandoms have a clear presence on Reddit, particularly fandoms pertaining to the abovementioned geek interests (e.g., Harry Potter, Marvel).

However, as both Massanari (2017) and Shelton et al. (2015) note, Reddit is comparatively underutilized by media researchers. My literature search revealed few studies of fandoms on Reddit, the exception being a study on “dark fandoms” – fandoms centered around mass or serial murderers like the Columbine shooters Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris (Broll, 2019). One reason for this may be that Reddit’s operational platform and internal culture makes for a different, less cohesive fan space. The relative ease of entry, pseudoanonymity, and “carnivalesque” culture of Reddit (Massanari, 2017) may provide a less stable and safe space for fans to disclose their shared interests and form connections. When compared to online fan forums and message boards (which tend to be private or semi-private and dedicated to a specific text), subreddits are far more open – they are generally accessible by anyone with a Reddit account. Individuals that comment and post on fan subreddits therefore may be a mix of actual fans and trolls, people with a passing curiosity, or people expressing sexual interest in a cosplay model. Moreover, the

overarching culture of Reddit, coupled with its operational structure, may make Reddit fan spaces more prone to toxic behavior, as Massanari (2017) discovered in her three-year ethnographic study. Another reason may be that Reddit is not widely known for its fandoms, meaning that fan scholars might opt for more visible sites of fan culture.

Nevertheless, as Shelton et al. (2015) found, redditors often take advantage of the relative anonymity of Reddit to make deeply personal disclosures, and tend to

compartmentalize their interactions on Reddit from those on other platforms. As a result, long-term relationships were almost never sustained on Reddit – “their conversations instead would shift to other applications such as Facebook, Meetup.com, or IRC” (p. 6). As such, subreddits may be isolated spaces where fans can discuss their love and modes of engagement with DFCs in a way that is different from those in more private fan spaces. For one, the social ties may be weaker, which combined with the uninhibited nature of Reddit culture, may make certain forms of engagement more intense and honest. Given the potentially shameful nature of loving DFCs – particularly those perceived as Nazi analogues, such as Voldemort and Bellatrix (SueTLC, 2007) – more fans may express engagement with DFCs on Reddit than on private fan spaces. This, combined with the searchability of Reddit and the fact that character limitations for comments and posts are

much greater (e.g., when compared to Twitter), makes Reddit a particularly interesting source of data on DFCs.

The subreddit I chose, /r/harrypotter, also known as the Great Hall (a reference to an area of Hogwarts), was created in 2008 – just three years after Reddit was founded. As of April 26, 2020, it has 785,8494 members. Moreover, despite the fact that the main book

series ended in 2007 and the final movie came out it 2011, links about the main series (including discussions, fanworks, questions, and other types of media) are posted daily to the subreddit. Moderators hold a variety of activities every month, including discussion weeks, fan fiction discussion days, and quizzes and other challenges. Moreover, users can be “sorted” into one of four houses (paralleling the four Hogwarts Houses), each of which has their own semi-private discussion space. Posts can be given different labels (e.g., “discussion,” “fanworks”), thus facilitating easy categorization.

4.2. Data Collection

The unit of analysis was the post, including the post title, content (e.g., text, images, hyperlinks), and comments. This allowed me to encapsulate fans’ competing

understandings of the DFCs of interest. To ensure that posts were relevant, I conducted searches using Reddit’s inbuilt search function, limiting all results to the /r/harrypotter subreddit. I focused on two male and two female DFCs (Bellatrix Lestrange, Lord Voldemort, Dolores Umbridge, and Severus Snape) to ensure that I had enough data and because these characters offer a good range in terms of personalities and textual exposure. Snape and Voldemort, who are both male, are featured in every book and movie in the main Harry Potter series, whereas the two female DFCs are featured in less than half of the books/movies (Bellatrix is featured in three books and four movies and Umbridge in two books and two movies). Although one might argue that these differing levels of textual exposure biases comparison, fans are not limited in their discussions or affective attachments to the most prominently featured characters in a text. As noted by Jenkins (2012), “Fan critics pull characters and narrative issues from the margins; they focus on details that are excessive or peripheral to the primary plots but gain significance within the fans' own conceptions of the series” (p. 155). Less exposure may even encourage

discussion, as fans will not be as bound by the textual material as they would when

discussing more well-defined characters. Indeed, Bellatrix had the highest number of posts among all characters. The characters also have clear parallels in terms of their roles in the story: Umbridge and Snape, as teachers at Hogwarts, are entrenched in the protagonists’ everyday lives, acting as normalized disruptive forces who hinder Harry, Ron, and Hermione’s actions within a relatively domestic sphere. In contrast, Bellatrix and Voldemort are outside threats whose aggressive actions reshape and reorient the protagonists’ everyday lives.

To obtain posts featuring discussions of these four characters, I conducted searches with combinations of the following keywords: “Umbridge,” “Snape,” “Voldemort,” “Bellatrix,” “like,” “love,” “evil,” “discussion,” “identify.” Initially, I conducted searches using only the character’s names; however, only the most relevant 250 posts were

displayed, so I had to employ more focused searches in line with my research question and ADT to obtain further data. The search results were organized by relevance and were not limited by date. I selected posts that mentioned at least one of the four characters in the title or that discussed the DFCs of the series in general, in order to obtain contextual information on how Harry Potter fans discussed DFCs. Both textual (e.g., discussion prompts,

questions) and visual (e.g., cosplay photographs, fanart) posts were selected, as both types featured discussions and commentary. Relevant posts were downloaded into NVivo 12 using the NCapture extension of Google Chrome (QSR International, Doncaster, Australia). I read through the posts and comments again in NVivo and removed those that did not discuss the character at length. This resulted in the retrieval of 153 posts with 10,436 comments. I subsequently removed all posts with fewer than 10 comments to ensure data manageability. From the posts, I extracted the title, number of comments, score and percentage of upvotes5, the relative date of the post, the poster’s username, the focal

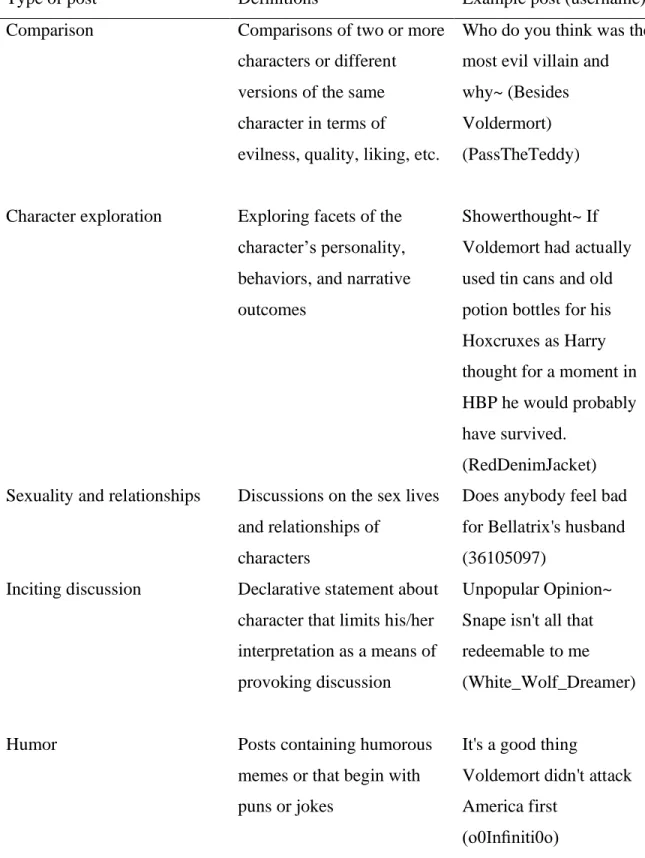

character(s), and the type of post (see Table 1 for a list and criteria used to define each type of post). See Appendix 1 for the full table of posts.

5 The score calculation method used by Reddit is not publicized to prevent users from abusing the system; it is

some combination of the number of upvotes minus the number of downvotes (Massanari, 2017). The higher the score, the more visible the post.

Table 1. Definitions of post categories extracted from /r/harrypotter

Type of post Definitions Example post (username)

Comparison Comparisons of two or more

characters or different versions of the same character in terms of

evilness, quality, liking, etc.

Who do you think was the most evil villain and why~ (Besides Voldermort) (PassTheTeddy)

Character exploration Exploring facets of the character’s personality, behaviors, and narrative outcomes

Showerthought~ If Voldemort had actually used tin cans and old potion bottles for his Hoxcruxes as Harry thought for a moment in HBP he would probably have survived.

(RedDenimJacket) Sexuality and relationships Discussions on the sex lives

and relationships of characters

Does anybody feel bad for Bellatrix's husband (36105097)

Inciting discussion Declarative statement about character that limits his/her interpretation as a means of provoking discussion

Unpopular Opinion~ Snape isn't all that redeemable to me (White_Wolf_Dreamer)

Humor Posts containing humorous

memes or that begin with puns or jokes

It's a good thing

Voldemort didn't attack America first

Criticism of fan object Posts that begin with a complaint about the way characters are represented in the fictional universe or portrayed by the actor or media producer

Unpopular opinion~ I hate movie Bellatrix (helloclarice-93)

Criticism of fandom Posts that criticize how characters are represented in fan fiction or other

fanworks, or in fan discussions

Does anyone else hate the theory that Umbridge was raped by centaurs

(Minxie)

Liking the DFC Expressions of love or appreciation for a given DFC or discussions of why certain DFCs are liked

Random question. As evil as bellatrix is, why do people like her so much (myself included)~ I don’t think it’s a bad thing, I’m just curious to hear as to why

(jiujitsuguy93)

Fanwork Posts containing fan fiction,

cosplay photographs, and fanart

My Bellatrix cosplay! (Aureliabex)

Other fan engagements Posts containing fan-related engagements that do not fit into other categories, such as posting photos of actors from other media texts with text placing these

photographs in the Harry Potter universe

Friendly reminder that this is what Voldemort would've looked like if he hadn't gone and fucked his shit up.

One challenge I faced in selecting posts was whether to divide posts by medium. Ultimately, however, I felt that doing so would overlook interesting results. Particularly, it would prevent me from exploring Cuntz-Leng's (2015) autopoetic feedback loop, which posists that the depictions of a character across different media converge over time. She writes: “The diffused nature of transmedia franchises like Harry Potter with large and productive fan communities makes it futile to distinguish text, performance, and reception, underlining even more their bond and their interdependency” (p. 83). For this reason, I made no attempt to distinguish the depictions of the character between the films and books in my selection of posts. Rather, I have assumed that fans who are still engaging with these characters long after completion of the main series have arrived at a more or less unified image of these characters, which makes distinguishing between how they receive the film and book versions “futile.”

4.3. Data Analysis

4.3.1. Analytical approach

I analyzed data using the hermeneutic approach of Patterson and Williams (2002). Although they situate their approach in the field of tourism and recreation studies (being from that background), it remains grounded in the productive hermeneutics tradition of Gadamer and the authors draw on social and psychological research when outlining its ontological, epistemological, and axiological commitments and methods – they frame it, in other words, as a general social scientific method. Moreover, I found their approach

accessible, well-developed, and relevant to answering my research question.

The hermeneutic paradigm, Patterson and Williams (2002) claim, is an interpretivist paradigm that seeks to reach context- and time-dependent understanding through

interpreting social actors’ communications (e.g., texts). It does not seek to break down phenomena into “discrete elements” but to understand them holistically. From an

ontological standpoint, it holds that “the world as experienced is not solely a construction of an individual's mental processes nor merely a reflection of the external world” (Patterson & Williams, 2002, p. 14). More specifically, it holds that “there is structure in the

other words, human experience is defined by “situated freedom” – not wholly being

dependent on either the environment or intrinsic personal freedoms. Such experience is best captured in “ready-to-hand” modes of engagement (which Patterson & Williams [2002] base on the writings of Martin Heidegger) – that is, everyday, context- and time-dependent personal projects such as writing an e-mail or engaging in discussions online. These modes of engagement are best “viewed as an emergent narrative rather than as predictable

outcomes resulting from the causal interaction of antecedent elements” (p. 18).

Epistemologically, hermeneutics holds that knowledge is co-created by the social actor and interpreter, rejecting the notion that interpretation can be objective. Such knowledge relies on a “forestructure of understanding” (p. 23) – essentially an informed form of biasing by extensive review of relevant literature and reflection on prior experience – and is never universal or generalizable. Instead, multiple interpretations are embraced, with the “bracketing” practice advocated by other qualitative approaches (e.g., content analysis) being rejected as effectively impossible. In summary, then, the hermeneutic approach attempts to delineate and explore “specific instances of a phenomena” through informed interpretation, with the emerging knowledge reflecting a unique instantiation of a much broader holistic phenomenon.

The ultimate goal of this knowledge production process is “understanding,” which Patterson and Williams (2002) emphasize is different from the close-ended, prediction-oriented understanding derived from positivist paradigms. Instead, understanding in hermeneutical terms is “open-ended and subject to change” (p. 28) – there is never a definite endpoint where we arrive at some form of generalizable law. The intent is to communicate what social actors experience within specific contexts based on the ways in which the interpreter (i.e., researcher) has sensitized themselves to the phenomenon of interest.

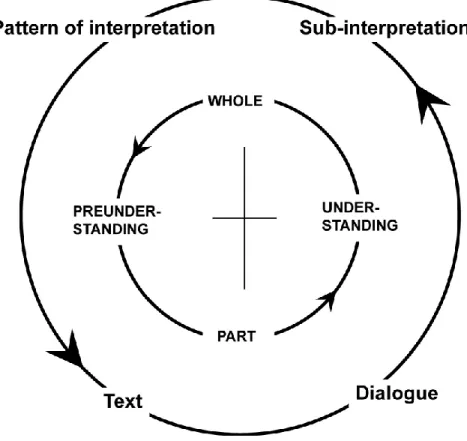

A key aspect of this knowledge-generation process is the “hermeneutic circle,” which refers to the practice of constantly moving between the individual parts of a text and the whole phenomenon of interest (i.e., the forestructure of understanding generated about a given phenomenon) and the act of generating an consistent pattern of interpretation through micro-level “sub-interpretations.” Alvesson and Sköldberg (2009) illustrate this

Figure 2. The basic hermeneutic circle (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2009)

I chose the hermeneutic approach for several reasons. First, it seems naturally suited to the exploration of the polysemic nature of fan interpretations. By embracing a more holistic perspective, I can provide a much richer understanding of the varied ways in which DFCs of different genders are represented in fan discussions. In doing so, I am illuminating areas where later researchers can bring in more rigorous, quantitative approaches (e.g., content analysis) to determine if my interpretations are generalizable.

Second, this thesis embraces areas of study with more or less distinct traditions, bodies of evidence, and assumptions (i.e., character engagement, gender representation, and fan studies). Accordingly, I felt that it was necessary to find a “middle ground” between them wherein I could adopt an informed position (i.e., generate a “forestructure of understanding”) but nevertheless be open to new insights and understandings, which is exactly what the productive hermeneutic approach allows (Patterson & Williams, 2002). It also allowed me to embrace my extensive preunderstanding of character engagement, DFCs, and the Harry Potter fandom, instead of forcing me to “bracket” it to arrive at a more

“objective” understanding (as I would have done with a more quantitative approach like content analysis). I believe this has helped deepen my analysis.

Finally, this approach was most familiar to me. As I come from a background of psychology and literature studies, I was more familiar with text-focused methods of analysis. I felt that embracing this competency was best suited to ensuring rigor.

4.3.2. Researcher position

I have been a fan of Harry Potter since I was about eleven years old – I have read all seven books in the original series, seen all ten films set in the Harry Potter universe, and during my teenage years read and wrote Harry Potter fanfiction. As such, I already have an extensive preunderstanding of Harry Potter and some of its fan cultures. I am therefore what fan studies scholars calls an “aca-fan” – an academic who happens to be a fan (Lamerichs, 2018). The hermeneutic approach allows me to embrace this position as integral to my analysis. For instance, it allows me to explore how fan interpretations more or less draw on textual content from one medium or another (e.g., the books, films, or fanfiction). However, as Lamerichs (2018) notes, “fan studies can benefit from more nuanced discussions on the role of fan identity in relation to the research object and process” (p. 52). In this case, while my aca-fan position positions me close to the text, it does not bring me close to my object of analysis – I have never participated in discussions on /r/harrypotter and am by no means a “redditor.” I do not, therefore, have an entirely insider position. This is disadvantageous in some ways, particularly in how I interpret the contextual role of Reddit culture in fan discussions about DFCs. However, the distance has helped me engage in continual self-reflexivity about my interpretations, which is necessary for their refinement.

Another major contributor to my forestructure is my status as a white heterosexual male. White male privilege is an extensively documented concept describing the ways in which white men tend to benefit from patriarchal systems of oppression in society (e.g., Case et al., 2014). Such privilege is often invisible and implicit; thus, without examination, it might lead me to overlook gendered content. Although I have strived to be self-reflexive, I may have overlooked more nuanced gendered concepts in my interpretations.

4.3.3. Data analysis procedure

I adhered to the approach outlined by Patterson and Williams (2002), eliminating steps not applicable to this thesis (as I did not conduct interviews): (1) I read through the posts and comments, (2) marked meaning units (individual comments discussing the DFC), (3) assigned thematic labels to these meaning units through an open coding process

informed by my forestructure of understanding, (4) considered the interrelationships among these thematic labels, and (5) wrote the interpretive discussion and analysis of these results. Steps 3–5 took place simultaneously and repetitively; I refined the thematic labels as I reflected on the text, in line with the hermeneutic circle (Patterson & Williams, 2002). I ignored comments not directly involved in discussion of the character. I also created a table of posts (Table 2 and Appendix 1) to provide a general overview of the data.

4.3.4. Trustworthiness

Patterson and Williams (2002) point out that a hermeneutic approach need should not rely on trustworthiness criteria conceived for more naturalistic paradigms. Instead, trustworthiness can be judged in terms of “persuasiveness,” “insightfulness,” and “practical utility.” Persuasiveness is defined as the degree to which readers can follow the analysts’ interpretations; insightfulness as the degree to which the analysis increases “our

understanding of a phenomenon” (p. 34); and practical utility is the degree to which the knowledge generated is based on concrete theory and methods. To ensure the

persuasiveness of my study, I have provided participant quotations throughout the analysis as evidence of my interpretations and I have tried to be as detailed as space allows. The insightfulness of my study lies in its attention to DFCs, who are understudied; my focus on a novel fan platform; and my comprehensive sampling procedure. The practical utility of this thesis was ensured by thorough literature review and immersion in related theory, which has helped to ground my interpretations in ADT, gender representation literature, and fan studies.

4.4. Ethical Considerations

Social media research is ethically fraught, particularly in spaces with diverse standards of conduct like Reddit. Researchers must constantly be aware of the extent to