Do the Swedish Female Consumers

Walk Their Talk?

A qualitative study exploring the Intention-Behavior gap

in sustainable secondhand fashion consumption

MASTER THESIS WIHITN Business Administration – Marketing

NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 hp PROGRAMME: Civilekonom

AUTHOR: Amanda Persson 960813-3600 & Elin Pedersén 960919-5285

TUTOR: Adele Berndt JÖNKÖPING: May 2020

Master thesis in marketing

Title: Do the Swedish Female Consumers Walk Their Talk? Authors: Amanda Persson & Elin Pedersén

Tutor: Adele Berndt Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Intention-Behavior gap, Sustainable fashion consumption, Secondhand fashion, Sustainable intentions, Sustainable behavior

Abstract

Background: In the last decade, the world has been facing global challenges of climate change as the climate has worsened significantly. Excessive consumption has been identified as one of the biggest contributors to the climate change where people purchase more products than what meets the basic needs. The excessive consumption of products has been prominent in the fashion industry, where female consumers generally purchase more clothes than men. Today, the fashion industry is dominated by fast fashion, where consumers purchase more clothes with a shorter life span. Thus, the fashion waste increases, leaving serious

environmental effects. Sweden is said to be one of the greenest countries in the world but is still one of the countries with the highest levels of consumption globally. The private

consumption is high in Sweden and one of the biggest consumer markets that have a negative effect on the environment is the fashion industry. As a result, sustainable fashion

consumption is becoming more important.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to explore the sustainable behavior of Swedish female consumers and later understand how different factors is affecting the IB gap in sustainable (secondhand) fashion consumption.

Method: To be able to achieve the purpose of this exploratory study, a qualitative research strategy was applied. The empirical data was collected through in-depth interviews held with Swedish female consumers with intentions to purchase secondhand fashion, which later was interpreted and analyzed through an abductive approach, incorporating a thematic analysis. Conclusion: The results of this study showed that the behavior of intenders can be characterized by sustainable intentions that do not translate into behavior. Further, the behavior can be characterized by a weak social support system (barrier), poor availability (barrier), low task- and maintenance self-efficacy, high recovery self-efficacy, and no planning. In addition, the results of this study showed that the behavior of actors can be characterized by sustainable intentions and sustainable behavior. Further, the behavior can be characterized by a strong social support system, good availability, high task- and recovery self-efficacy, medium to high maintenance self-efficacy, and planning. The comparison between intenders and actors showed that the perceived barriers for intenders was contributing factors to the IB gap together with their low task- and maintenance self-efficacy through their most likely negative effect on intenders planning. Intenders lack of planning was shown to serve as a negative mediator between intention and behavior, which thereby contributes to the IB gap.While the recovery self-efficacy was high for both intenders and actors, actors has recovery self-efficacy for the desired behavior of purchasing secondhand on a regular basis, while intenders does not.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to each and everyone who have

helped and encourage us in prosperity and adversity throughout the entire process

of conducting this thesis.

First of all, we would like to thank our supportive, patient, and inspiring supervisor

Adele Berndt for everything she has done for us. We are so grateful for all the

feedback and every answer on our never-ending questions.

Secondly, we would like to thank our meticulous and helpful co-working seminar

participants for always sharing their thoughts and opinions with us.

Lastly, we would like to thank each and every one who devoted their time and effort

to participate in our study. Without you, this would never been possible.

Amanda Persson Elin Pedersén

Jönköping International Business School May 2020

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 7

1.1 Background ... 7

1.2 Sustainable Fashion Consumption ... 9

1.3 Problem ... 10

1.4 Purpose ... 11

1.5 Research Questions ... 11

1.6 Contribution ... 12

1.7 Key Terms Definitions ... 12

2. Theoretical Framework ... 13

2.1 The Intention-Behavior Gap ... 13

2.2 Sustainable Consumerism ... 14

2.3 Previous Research ... 14

2.4 HAPA Model ... 15

2.5 Principles of HAPA ... 17

2.5.1 Principle 1: Motivation and volition ... 17

2.5.2 Principle 2: Two volitional phases ... 18

2.5.3 Principle 3: Postintentional planning ... 18

2.5.4 Principle 4: Two kinds of mental simulation ... 18

2.5.5 Principle 5: Phase-specific self-efficacy ... 19

2.6 Constructs of the adapted HAPA model ... 20

2.6.1 Intention ... 21

2.6.2 Action ... 22

2.6.3 Barriers and Resources ... 23

2.6.4 Task Self-Efficacy ... 25 2.6.5 Maintenance Self-Efficacy ... 26 2.6.6 Recovery Self-Efficacy ... 27 2.6.7 Planning ... 28 2.7 Consumer Groups ... 29 2.8 Research Model ... 32 3. Research Methodology ... 33 3.1 Methodological Reasoning ... 34 3.1.1 Research Philosophy ... 34 3.1.2 Research Design ... 35 3.1.3 Research Approach ... 36 3.1.4 Research Strategy ... 37 3.1.5 Research Method ... 38 3.1.6 Sample Strategy ... 40 3.1.7 Sample Selection ... 41

3.2 Data Collection Techniques ... 42

3.2.1 Primary Data ... 42

3.2.2 Secondary Data and Literature Review ... 42

3.2.3 Qualitative Interviews ... 43

3.3 Data Analysis ... 45

3.5 Ethical Considerations ... 50

4. Empirical Findings ... 52

4.1 Intenders ... 53

4.1.1 Intention and Action ... 53

4.1.2 Barriers and Resources ... 55

4.1.3 Task Self-Efficacy ... 56

4.1.4 Maintenance Self-efficacy ... 57

4.1.5 Recovery Self-efficacy ... 58

4.1.6 Planning ... 58

4.2 Actors ... 60

4.2.1 Intention and Action ... 60

4.2.2 Barriers and Resources ... 62

4.2.3 Task Self-efficacy ... 63

4.2.4 Maintenance Self-efficacy ... 64

4.2.5 Recovery Self-efficacy ... 65

4.2.6 Planning ... 65

5. Analysis and Discussion ... 68

5.1 Intenders ... 68

5.1.1 Main theme 1: Sustainable Intentions ... 68

5.1.2 Main Theme 2: Weak Social Support System & Poor Availability ... 70

5.1.3 Main Theme 3: Low Task Self-Efficacy ... 71

5.1.4 Main Theme 4: Low Maintenance Self-Efficacy ... 72

5.1.6 Main Theme 6: Non-Planner with Weak Implementation Intentions ... 74

5.2 Actors ... 75

5.2.1 Main theme 1: Sustainable Intentions & Actions ... 75

5.2.2 Main Theme 2: Strong Social Support System & Good Availability ... 76

5.2.3 Main Theme 3: High Task Self-Efficacy ... 77

5.2.4 Main Theme 4: Medium-High Maintenance Self-Efficacy ... 78

5.2.5 Main Theme 5: High Recovery Self-Efficacy ... 79

5.2.6 Main Theme 6: Action & Coping Planner with Strong Implementation Intentions ... 79

5.3 Connection & Comparison ... 80

5.3.1 Connection Intenders ... 80

5.3.2 Connection Actors ... 81

5.3.3 Comparison ... 83

6. Conclusion ... 87

6.1 Purpose and Research Questions ... 87

RQ 1. ... 87 RQ 2. ... 88 RQ 3. ... 88 6.2 Implications ... 89 6.2.1 Theoretical Implications ... 89 6.2.2 Managerial Implications ... 90 6.2.3 Societal Implications ... 91 6.3 Limitations ... 91 6.4 Future Research ... 92 References ... 111

Figures

Figure 1: HAPA Model 17

Figure 2: Excluding Components in Original HAPA Model 20

Figure 3: Intention Construct in The Adapted HAPA Model 21

Figure 4: Action Construct in The Adapted HAPA Model 22

Figure 5: Barriers and Resources Construct in The Adapted HAPA Model 23 Figure 6: Task Self-efficacy Construct in The Adapted HAPA Model 25 Figure 7: Maintenance Self-efficacy Construct in The Adapted HAPA Model 26 Figure 8: Recovery Self-efficacy Construct in The Adapted HAPA Model 27

Figure 9: Planning Construct in The Adapted HAPA model 28

Figure 10: Postintentional-preactional Stage (Intenders) 31

Figure 11: Actional Stage (Actors) 32

Figure 12: Research Model 33

Tables

Table 1: Trustworthiness 48

Table 2: Participants List 52

Table 3: Initial Findings Intenders 60

Table 4: Initial Findings Actors 69

Table 5: Main Findings Intenders 76

Table 6: Main Findings Actors 83

Table 7: Comparison of Main Findings 85

Table 8: Barriers 87

Appendices

Appendix 1: Search Process 97

Appendix 2: Interview Guide (English) 98

Appendix 3: Interview Guide (Swedish) 101

Appendix 4: Participant List 103

Appendix 5: Thematic Analysis 104

5.1 Initial Coding 104

5.2 Searching and Reviewing Themes 111

1. Introduction

In this chapter, the researchers will present a general introduction of the research topic of sustainable fashion consumption. Further the gap between intention and behavior and how this relates to consumption of secondhand fashion is brought to notion. A solid background together with a discussion of the problem highlights the disparity between consumers intentions and behavior in sustainable fashion consumption and thus presents a motivation of why the study is relevant. The purpose and contribution of the research will be presented as well as the research questions along with definitions of key terms for the thesis.

1.1 Background

Will the world burn down or survive to sustain life for the next generations? The world is facing existential threat caused by the climate change. In the last decade, the climate has worsened with the significant increases in the fluctuations of average temperatures around the globe (Vincze et al., 2017). Melting ice, droughts, floods and Amazon fires are just a few of the catastrophic effects fueled by the climate change. Even though all these warning signals are displayed, and disasters continue to happen, the humankind maintains the same lifestyle and continues to live like there was no tomorrow. How much longer can earth support life?

The global challenge of climate change is due to the actions of humans to a large extent where excessive consumption has been identified as one of the biggest contributors (Terlau & Hirsch, 2015). Several scholars identify this problem as overconsumption where the core of the problem is the growing materialism and the excessive use of resources where consumers purchase more products than what meets the basic needs (de Graaf et al., 2014; Humphery, 2009; Håkansson, 2014). Excessive consumption is directly related to excessive production where the higher demand of products requires more natural resources, increased emissions and waste of resources (Terlau & Hirsch, 2015). Overconsumption exists in many different industries and entails different environmental issues. Clothing overconsumption in the fashion industry, dominated by fast fashion, is a global issue with serious effects on the environment (Diddi et al., 2019). The characteristics of fast-fashion is just-in-time production that constantly adapts to new trends, low prices and shorter lifespan clothing, resulting in consumers buy more than they need (Pookulangara & Shephard, 2013). When consumers buy more fashion with a

environmental effects (Jung & Jin, 2016). Hence, the fashion industry is of interest when performing a study on sustainable consumption and where contributions can be made.

Depending on geographical location, the environmental consciousness and sustainable development of consumers differs. One of the countries that is foremost in sustainable development where the consumers are considered sustainably aware is Sweden. The Environmental Performance Index is a national scale, ranking 180 countries based on their environmental performance. The EPI for 2018 placed Sweden in the top five sustainable countries in the world (Wending et al., 2018). With a high environmental performance, including environmental health and ecosystem vitality, Sweden is one of the “greenest” countries in the world. However, Sweden is not an exception for contributing to the climate change. A study conducted by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Gullers Grupp, 2018) showed that 95% of the respondents believed that Sweden would be affected by the climate change and 86% thought that it was necessary to act for a difference. These results show that people in Sweden are aware of the ongoing climate change, and they believe that today’s behavior of the Swedish population has to change. The same study showed that 78% think that their own acting can make a difference (Gullers Grupp, 2018). Despite this, the numbers showing the consumption-based emissions in Sweden has only decreased from 40,82 to 37,29 from 2008 to 2017 (Allerup, 2019).

In a report published by the Konsumentverket (2018), it was revealed that the private consumption of the Swedish consumer is high when compared to other countries in Europe and Sweden is one of the countries that has the highest levels of consumption globally (Konsumentverket, 2018). In the report, it was determined what consumer markets that have the biggest impact on the environment, with a measurement based on supply, price, social norms, access to information and simplicity. The three stated consumer markets that contributed to the biggest negative effect on the climate in 2018 was; vehicle fuel, airplane travel and fashion. Further, fashion is not only one of the product categories that require most natural resources in production, but also the category where it is most difficult to make sustainable choices according to the Swedish consumer. According to Roos (2019), the consumption of fashion has slowed down in recent years and improvements have been made as consumers buy more secondhand fashion and less fast fashion. However, it is suggested that the consumption of newly produced fashion needs to decrease further for Sweden to reach their long-term sustainability goals (Konsumentverket, 2018). With an alternative consumption

routine, where consumer swap they consumption of newly produced fashion for secondhand fashion, one can still purchase the same amount of fashion without leaving environmental footprints on our planet.

Previous studies have shown that women in Sweden have a more positive attitude towards the environment and sustainability than men and are more willing to change their behavior towards sustainable consumption (Gullers Grupp, 2018). The same study shown that Swedish women are more optimistic towards the possibility to implement a sustainable action in order to positively affect the environment. In addition to that, women tend to purchase more fashion than men. According to Adolfsson (2019), the fashion consumption of women was 34,6% higher than men in 2018. This was discovered through a survey showing that men purchase the same amount of clothes in 2018 as they did in 2000 (2,6kg), while women’s fashion consumption has increased from 2,7kg to 3,5kg between the years of 2000 and 2018. Hence, women are more prone to purchase fashion than men. Furthermore, women fit the profile of the subgroup that are more likely to purchase sustainable fashion. Thus, it is suitable for this study since the researchers aims to explore a group of individuals that are willing to change in order to push sustainable consumption of fashion forward through marketing interventions.

1.2 Sustainable Fashion Consumption

Sustainable consumption in fashion can have many different meanings. For some, the concept of sustainable fashion is related to organic cotton, fair trade, eco or ethical production, whereas for others, sustainable fashion is related to secondary markets where no new production is involved, e.g. reuse and disposal (Cervellon et al., 2010). However, it can be argued that reuse, e.g. secondhand fashion, has the greatest impact on the environment (Allwood et al., 2008; Laitala et al., 2012). Even if the products are made out of 100% organic cotton, it still has to go through a production process before reaching the hand of the consumer. Whereas, consumption of secondhand fashion does not include any new production or use of additional resources. For instance, if the emission of producing one t-shirt is 4,5 CO2e (Naturskyddsföreningen, 2019) and there are two persons that use it during its lifetime, then there is only 2,25 CO2e per person that affects the environment, instead of them purchasing one t-shirt each and contributing with 9 CO2e to the environment. Since the greatest environmental effect can be reached with consumption on a secondary market, the term sustainable consumption in this study will refer to secondhand fashion. In addition to that, the secondhand

industry in Sweden is interesting to study since the report has shown that, out of the 12,5 kilos new textiles that people purchased, there were only 2,4 kilos that were reused instead of going to recycling, landfill or incineration (Elander et al., 2014). Out of those 2,4 kilos there were 0,9 kilos that was reused in Sweden, and the rest was sent abroad (Elander et al., 2014). To send clothes abroad also contributes to the greenhouse effect, so there would be an advantage if the clothes could be used in Sweden instead, were they are already located.

Over the last few years, sustainable consumption has seen an increase where the consumers are more environmental aware and engage in reuse and reselling of fashion (Pookulangara & Shephard, 2013). The taboo around purchasing pre-used fashion seem to be shifting and a trend of secondhand consumption has bloomed (Naturskyddsföreningen, n.d.). Thus, today it seems more shameful to purchase new fashion than secondhand fashion. According to Konsumentverket (2020), the change of norms is important to the attitude the consumers have towards sustainable fashion. Secondhand consumption is accepted by the consumers when it becomes a part of the social norm. The social acceptance for this form of consumption is also important for behavioral change of Swedish consumers, where the acceptance work as a motivator to engage in sustainable consumption (Konsumentverket, 2020). With the sustainable fashion trend and shifts of norms in the mind of the consumers, the secondhand marketplace in Sweden has grown. The physical secondhand stores have expanded beyond charity organizations such as Röda Korset to profit-driven companies such as Beyond Retro. In addition to that, the online marketplace for secondhand consumption has grown. Today, several websites such as Tradera, Sellpy and Yaytrade offer both companies and private consumers to sell and purchase secondhand fashion.

1.3 Problem

Despite having intentions to engage in sustainable consumption, consumers do not always purchase secondhand fashion. A previous study shows that 30% of consumers say that they have the intentions to purchase ethically, but only 3% do (Carrington et al., 2010). This is a recurrent phenomenon in social research and ethical behavior studies, called the Intention-Behavior Gap (IB gap), where consumers fail to translate their intentions into behavior (Auger & Devinney, 2007; Carrington et al., 2010). In order to push sustainable development forward, it is important to understand the gap between what consumers intend to do and what they actually do. In a study by Schwarzer et al. (2011) it is argued that people can be characterized

by different psychological states and should therefore be divided into two subgroups based on their ability to engage in a behavior: inactive people (intenders) and active people (actors). Intenders are those that have intentions to engage, but have not yet, while actors are those that actually engage in the desired behavior. Thus, by exploring what characterize the behavior of intenders and actors together with the differences in the behaviors, one can understand the factors contributing to the gap between intention and behavior and the factors that are important to actually engage in the desired behavior.

By interviewing women in Sweden, the researchers are going to explore if there is a gap between intention and behavior, and if so, what is contributing to it, specifically in the case of secondhand fashion. With support from the testing model on green consumption behavior by Nguyen et al. (2019), the Intention-behavior mediation and moderation model of the ethically minded consumer by Carrington et al. (2010), and the HAPA model by Schwarzer et al. (2011), different variables that affect the consumer between intentions and behavior will be explored. For example, a woman has a positive attitude toward the environment and believe that the climate change is a problem and that she can do something about it. She has the intention to engage in sustainable consumption but ends up not doing it. Why does the intention of the consumers not lead to behavior? Do the Swedish female consumers walk their talk?

1.4 Purpose

The purpose of this study is to explore the sustainable behavior of Swedish female consumers and later understand how different factors is affecting the IB gap in sustainable (secondhand) fashion consumption. Through that, the researchers aim to provide marketing managers with a basis for marketing to help them design marketing interventions for secondhand fashion. This in order to bridge the gap between the intention and behavior and engage more consumers in sustainable fashion consumption.

1.5 Research Questions

1. What characterize the behavior of the Swedish female consumer that has the intentions to purchase secondhand fashion on a regular basis but does not behave accordingly? (Intenders)

2. What characterize the behavior of the Swedish female consumer that has the intentions to purchase secondhand fashion on a regular basis and does behave accordingly? (Actors)

3. What are the differences in characteristics of the behavior between intenders and actors, and how does that contribute to the assumed gap between intention and behavior?

1.6 Contribution

This research will contribute to the understanding of the Swedish sustainable fashion consumer in the sense of bridging the IB gap. The report aims to come to a conclusion of what affects the consumer in such way that the intentions does not translate into behavior in order to contribute to the sustainable development in Sweden and reduce the environmental footprint from production of new fashion. By understanding what characterize the behavior of an intender and what characterize the behavior of an actor, the findings and results will serve as a tool to assist marketers when designing marketing campaigns to better fit the target groups of secondhand fashion.

1.7 Key Terms Definitions

Intention-Behavior gap: a gap that arises when consumers fail to translate their intentions into behavior (Auger & Devinney, 2007).

Sustainable fashion consumption: Sustainable fashion consumption covers a range of behaviors including reuse and disposal of clothes (Lundblad & Davies, 2016). In this study, sustainable fashion consumption is focused on reuse of existing clothing, i.e. secondhand fashion.

Secondhand fashion: Secondhand fashion can be categorized as any piece of clothing that has been used before (Cervellon et al., 2012).

Sustainable Intentions: Intentions are usually referred to consumers’ willingness to perform a specific behavior (Cristea & Gheorghiu, 2016). Sustainable intentions are therefore

consumers’ willingness to perform a sustainable behavior, e.g. purchasing secondhand fashion.

Sustainable Behavior: Sustainable behavior can be defined as a set of actions that protects the planet by limited the use of resources (Corral-Verdugo et al., 2010). It requires

2. Theoretical Framework

In this chapter, the researchers present a thorough and broad theoretical framework in order to get a deeper understanding of the research topic. Firstly, the researchers will present an explanation of the phenomenon Intention-Behavior gap followed by what previous studies in the field has covered, demonstrating limitations in existing research. Additionally, a thorough explanation of the adaption of the HAPA model in combination with the Green Consumption Behavior-Testing model, and the Intention-Behavior Mediation and Moderation model will be presented. Lastly, the readers will be provided with information about the two consumer groups, intender and actors, with a following research model, i.e. the adapted HAPA model.

2.1 The Intention-Behavior Gap

A widely researched topic in social research is behavioral intention where the relationship between intentions and behavior are studied. Behavioral intentions can be described as people´s decision to perform particular actions (Sheeran, 2002) where people give instructions to themselves in order to behave in a certain way (Triandis, 1980). According to Sheeran (2002), behavioral intentions encompass direction and intensity of decisions that people make, e.g. to purchase secondhand vs. to not purchase secondhand (direction) and how much time and planning people are willing to spend on sustainable fashion consumption (intensity). However, intentions do not always translate into behavior, which results in a gap, i.e. IB gap. The intention-behavior gap (IB gap) is a phenomenon that has been investigated by several researchers through times and there are many suggested factors that contributes to it (Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; Auger & Devinney, 2007; Gollwitzer, 1999). For example, a person has the intention to purchase secondhand, but for some reason he/she does not purchase secondhand. According to Gollwitzer (1999) “the correlations between intentions and behavior are modest; intentions account for only 20% to 30% of the variance in behavior” (p. 493). Thus, the intention itself is not likely to result in a successful behavior, and there are probably other things that contributes to the remaining 70-80% of the variance in the behavior.

2.2 Sustainable Consumerism

Ethical consumer behavior has become an important topic in marketing research as more attention is directed to green consumption and environmental issues (Haws et al., 2014; Peloza et al., 2013). It has been observed that Ajzen’s (1991), Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) generally has been applied among studies on green consumption and ethical consumer behavior, investigating the gap between green consumers intentions and behavior (Carrington et al., 2010; 2014; Nguyen et al., 2019). However, most of the developed theories focuses on how ethics influence consumers attitude towards sustainable behavior and the models fail to consider the disparities between intention and behavior (Fukukawa, 2003; Carrington et al., 2010; Nguyen, et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2017). In other words, many scholars put an emphasize on the attention-behavior gap, where belief determine attitude, attitude leads to intentions, and intention inform behavior (Carrington et al., 2010). The difference between attitude and intentions is that, attitude is a person’s belief and approach, while intentions are what people plan to do in a specific purchase situation (Carrington et al., 2010). According to Ajzen & Fishbein (2005), research in consumer behavior usually correlate the intention with the actual behavior, implying that intention directly lead to behavior. However, they also claim that there is literal inconsistency, meaning that there is always gap between the intention and the actual behavior. In addition to that, Bagozzi (1993), stated that intention is a poor predictor of the actual consumer behavior. Thus, a gap in previous research was found. In addition to that, only few studies have been conducted in the field sustainable fashion consumption, and no previous research investigates why the green consumer do not translate their intentions of purchasing secondhand fashion into behavior, i.e. actually purchasing secondhand fashion.

2.3 Previous Research

While most studies of ethical consumer behavior have explored the attitude-intention gap, some scholars have been directing their focus to the IB gap. One of the scholars that has been researching the actual gap between intention and ethical consumer behavior is Carrington et al. (2010). The study focuses on addressing limitations in previous studies on ethical consumerism by integrating relevant external elements from social psychology in order to develop a conceptual framework that reflects the complex purchase decisions that it true to reality. This with the purpose of developing a model that bridge the IB gap in order to offer strategic directions and insight to marketing managers. In this study, the model by Carrington et al.

(2010) will be included in the planning construct (Section 2.6.7) of the adapted HAPA model by adding implementation intentions in order to translate health behavior into consumer behavior. Another scholar who has focused their study on the gap between intentions and green consumer behavior is Nguyen, et al. (2019). The study presents a theoretical framework and a model to explain positive and negative relationships between green intentions and behavior. This in order to test the relationship between intentions and behavior of the green consumer. In this study, the model by Nguyen et al. (2019) will be included in the barriers and resources construct (Section 2.6.3) of the adapted HAPA model by adding availability as a possible barrier or resource influencing the behavior of the sustainable consumer.

2.4 HAPA Model

Previous models mentioned are not developed to profile consumer groups, nor, design interventions to move the consumer closer to behavior. According to Peattie (2001), many studies of green consumption are focusing on understanding green behavior and argue that it is the wrong field to search when trying to profile green consumers. To be able to explore the factors influencing the IB gap, an adapted version of the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) model have been developed and used in this study (Schwarzer et al., 2011). This since the primary purpose and use of the HAPA model is to explain, predict and describe changes in the health behaviors of patients of rehabilitation and can be applied for consumer behavior with support from previous studies on ethical consumerism by Carrington et al. (2010) and Nguyen et al. (2019). Unlike the models mentioned earlier, HAPA is a stage layered model that subdivide individuals into consumer groups and develop tailored interventions in order to move the consumer closer to behavior. Hence, the HAPA model is supposed to help with theory-guided interventions with the goal of a successful result for each individual, i.e. reaching the stage of action. With the HAPA model as a foundation, combined with previous studies on the ethical consumer gap, the purpose of exploring the gap in order to profiling consumers can be achieved. In addition to that, tailored interventions can be design in order to push sustainable consumption forward.

The HAPA model was developed since researchers thought that there were limitations in the already existing models such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991) and the Social-Cognitive Theory (SCT; Bandura, 2004). TPB and SCT are both continuum models which means that the probability of action is reflected through the position of the people along

a range. What influences the people are then combined into one prediction equation which lead to the interventions being focused on all variables of all people on the range at once, and not specific to each group of people. To give an example of an extreme situation for a clear understanding, having the same intervention for all people on a range could be that you try to sell the same food in the same way to people for the age of five to fifty. You base your intervention on the fact that people eat and buy what they like to eat and what they can afford, i.e. two factors. But you forget about the fact that a five-year-old would not eat the same thing as someone being fifty years old, and the child does not purchase his or her own food, the parents does. Continuum models have the disadvantage of not being able to include the prediction of behavior, i.e. they are not covering the post-intentional factors that is important to be able to overcome the IB gap. This is where the HAPA model has its strengths and thus is a good fit for this study. The HAPA model covers the gap where continuum models lack factors, and therefore the process between intention and behavior has been divided into qualitative stages.

In contrast to continuum models, HAPA is a stage model that suggests that the behavior change is less like a range and more like an ordered set of stages into which people can be categorized. These stages reflect either behavioral characteristics or cognitive characteristics (Schwarzer et. al., 2011). Based on a previous study by Weinstein et al. (1998), Schwarzer, et al. (2011) explain that a stage model can be defined by following properties: “(1) Individuals can be classified into different stages by a valid assessment procedure; (2) The stages are ordered.... A person in Stage 1 has to move first to Stage 2 before proceeding to Stage 3 and finally adopting the criterion behavior,” and, “(3) Individuals in the same stage are more similar than those in different stages; that is, they face the same barriers, but these barriers are different from those in other stages” (p. 162). While the HAPA model has both an continuum layer and a stage layer, for this study the latter one is chosen as stage models are beneficial when guiding interventions, i.e. trying to move the consumer from one stage in the model to another, thus increasing the chances of bridging the gap, which is the goal of this study. The model proposes a difference between the process before intention where the person is driven by motivation towards behavior and the process after intention where the person is driven by volition towards behavior. Motivation and volition are the two phases of the HAPA model, and these will be further explained in the following sections.

2.5 Principles of HAPA

As mentioned earlier, the HAPA model (Schwarzer et al., 2011) has two layers; a continuum layer and stage layer. The design of the model is called open architecture and entails a set of principles that it is based on rather than testable assumptions. The principles are constructed to help researchers to apply the model to research and investigations, i.e. they are supposed to help the researchers of, for example, this study to apply the HAPA model into this research (Schwarzer et al., 2011).

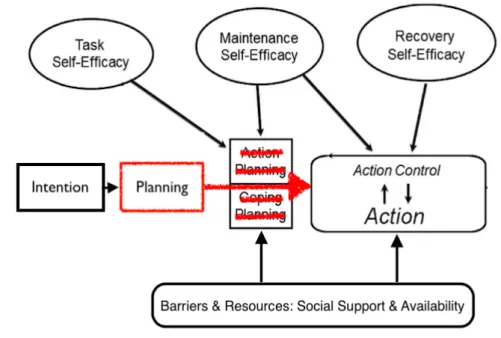

Figure 1: HAPA Model (Schwarzer et al., 2011)

2.5.1 Principle 1: Motivation and volition

The original principle of HAPA (Schwarzer et al., 2011) is stated as: The health behavior process is divided into two phases, motivation and volition. Motivation is the first phase where people develop the intention to perform the behavior. Phase two, the volition phase, is where people already has the intention but is driven by the volition of performing the behavior, i.e. “there is a switch of mindset when people move from deliberation to action.” (Schwarzer et al., 2011, p. 163).

In the case of this study, the motivation phase will not be included since the focus will be on consumers that already has the intention, i.e. are in the volition phase. Thus, the switch of mindset has already happened, and the consumers are driven by the volition to purchase second hand.

2.5.2 Principle 2: Two volitional phases

The original principle of HAPA (Schwarzer et al., 2011) states: The second phase, volition, divide people into two subcategories; Inactive people and active people. Inactive people have not translated the intention of behavior into actual behavior and active people are those who has. These two groups of people are “characterized by different psychological states” (Schwarzer et al., 2011, p. 163). Therefore, one can divide people in the health behavior change process into three categories where they have different mindsets; preintenders (motivational phase), intenders (volitional phase), and actors (volitional phase).

In the case of this study, only intenders and actors will be included since preintenders does not yet have the full intentions to engage in the behavior. Thus, the focus will be on the two volitional phases where there are consumers who have the intention and the will to purchase secondhand fashion but does not, i.e. inactive consumers or intenders and people with the intention and the will who does purchase secondhand fashion, i.e. active consumers or actors.

2.5.3 Principle 3: Postintentional planning

The original principle of HAPA (Schwarzer et al., 2011) states: “Intenders who are in the volitional preactional stage are motivated to change, but do not act because they might lack the right skills to translate their intention into action” (Schwarzer et al., 2011, p. 163). To overcome this barrier, planning is important, since it works as an operative mediator for people between behavior and intention.

In the case of this study it would mean that there could be consumers that has the intention and will of purchasing secondhand clothes, but they are not actually doing it since they, for example, does not know where to purchase it. If the consumers are doing a good job on planning the action of purchasing secondhand fashion, i.e. researching places to purchase secondhand fashion, then they are more likely to translate their intentions into behavior, i.e. not only thinking about purchasing it but actually doing it.

2.5.4 Principle 4: Two kinds of mental simulation

The original principle of HAPA (Schwarzer et al., 2011) states: There are two types of planning; action planning and coping planning. When, where and how the action will be performed is action planning. “Coping planning includes the anticipation of barriers and the

design of alternative actions that help to attain one’s goal despite the impediments” (Schwarzer et al., 2011, p. 163)

In the case of this study it would mean that consumers planning to perform the action or to translate the intention into behavior is performing action planning. This type of planning involves where to purchase secondhand fashion, i.e. in what store. It involves when to purchase it, e.g. what day or time, and how to purchase it, e.g. by yourself or with company, with cash or card. Coping planning on the other hand is planning to be able to cope with setbacks or challenges during the process of translating the intention to purchase secondhand fashion into actually doing it.

2.5.5 Principle 5: Phase-specific self-efficacy

The original principle of HAPA (Schwarzer et al., 2011) states: “Perceived self-efficacy is required throughout the entire process” (p.164), but it differs from phase to phase since people face different challenges in them. There are differences between the challenges in maintenance, initiative, goal setting, planning and action. The result of this is that one should be aware of the difference between preactional efficacy (also called task efficacy), coping self-efficacy (also called maintenance self-self-efficacy), and recovery self-self-efficacy (also called recovery self-efficacy) (Schwarzer et al., 2011).

In the case of this study it would mean that a consumer has different ways of perceiving his or her own ability to purchase secondhand fashion, planning to purchase it, and handle setbacks and challenges related to doing it. The consumer might think that he or she is able to purchase it and plan in but does not think that he or she is able to handle any setbacks, as for example not finding what you are looking for in the matter of item or size.

2.6 Constructs of the adapted HAPA model

Figure 2: Excluding Constructs in Original HAPA Model

The HAPA model (Schwarzer et al., 2011) explores different constructs that affect the IB gap: intention, action (action control), barriers and resources, self-efficacy (task, maintenance and recovery), risk perception, outcome expectancies, and, planning (action and coping). This study is going to exclude outcome expectancies and risk perception, which are factors influencing the intention of the consumer. These factors are excluded since the focus will be solely on factors influencing the actual gap between intention and behavior. Thus, an assumption will be that the consumers already has the intention of consuming secondhand fashion and therefore, the factors affecting intention will not be of interest. The remaining constructs will be discussed in the following sections.

2.6.1 Intention

Figure 3: Intention Construct in The Adapted HAPA Model

The Intention construct is where individuals have formed intentions to perform a behavior, but the actual behavior does not take place. In the original HAPA model, both positive outcome expectancies (e.g. the belief that exercising a certain amount of times per week can reduce risk of health problems) and perceived self-efficacy (e.g. the belief of one being capable of follow a training schedule, even if it is tempting to not do it) is needed in order to form intentions to adopt a behavior (Schwarzer et al., 2011). According to (Schwarzer et al., 2011), intentions can be measured through statements such as “I intend to perform the following activities at least three days per week for 40 min” (p. 164).

In this study, the participants have positive outcome expectancies and perceived self-efficacy as they already formed intentions to adopt the behavior, i.e. purchasing secondhand fashion, and those factors will not be explored. However, since sustainable consumer behavior is complex, the measurement used in the original HAPA model cannot be utilized. Consumption of fashion can be very individual and a desired quantity cannot be predetermined as some people may purchase fashion once a week, while other may only purchase twice a year. Therefore, intention will be explored through questions such as “Do you intend to purchase secondhand fashion on a regular basis” (Schwarzer et al., 2011, p. 164). It is then up to people to make a subjective judgement of whether they intend to purchase secondhand fashion on a regular basis, compared to newly produced fashion. According to Schwarzer et al. (2011), intention should be measured in the same way as behavior, and behavior can be measured subjectively or objectively.

2.6.2 Action

Figure 4: Action Construct in The Adapted HAPA Model

The Action construct is the goal of the model and this is where the actual behavior takes place. Every construct that will be mentioned in the upcoming sections is affecting action in one way or another, but the closest and most affecting ones are maintenance efficacy, recovery self-efficacy, planning, and barriers and resources (Schwarzer et al., 2011).

In the original HAPA model (Schwarzer et al., 2011), the action is divided into two parts: action control and action. Action is also stated as behavior, and it can be measured subjectively or objectively. In the terms of rehabilitation and the original purpose of HAPA, the options are to track steps as an objective method and diary logs as subjective method. Action control is a concurrent self-regulatory strategy, which means that whilst the person is pursuing the behavior, he or she is simultaneously evaluating if the currents situation is in line with his or her behavioral standard. It is measured through statements such as “I often had my exercise intention in mind”, “I consistently monitored when, where and how long I exercise”, and, “I really tried hard to exercise regularly” (Schwarzer et al., 2011, p. 165).

In this study it is a construct that contains the actual behavior of purchasing secondhand clothes on a regular basis. It could be explored objectively by asking the consumer how much secondhand they purchased out of their total fashion consumption. Subjectively, it could be explored by asking whether or not they are purchasing secondhand on a regular basis, which would be up to each participant to value what counts as regular basis and not. When a consumer

is in the action construct, they are consuming secondhand, but since this construct is continuously affected by previously mentioned constructs, the consumer is not “stuck” here and is not in a 100% behavioral mode. This is also shown by the fact that the stage is divided into action and action control. The action control in this study is the consumer's ability to learn from themselves in their process of consuming secondhand. By remembering when, where and how the consumer purchase secondhand clothes last time and actually thinking about their original intentions, which is to purchase secondhand.

2.6.3 Barriers and Resources

Figure 5: Barriers and Resource Construct in The Adapted HAPA Model

In the original HAPA model (Schwarzer et al., 2011), barriers and resources have the focus of social support, i.e. support to the person in rehabilitation from family and friends. Schwarzer et al. (2011) define social support as a resource, and the lack of it could be a barrier for engaging in a behavior. Social support can be emotional, informational, or instrumental. For those classified as intenders it can enable the adoption of the behavior, and for those classified as actors, it can enable continuation of the behavior (Schwarzer et al., 2011). This is influencing the person in all stages, and therefore makes it a vital factor of the change of behavior. It is measured through the question “My family/friends…” with answering options e.g. “… have encourage me to perform my planned activities” and “… have helped me to organize my physical activity” (Schwarzer et al., 2011, p. 165). It is stated to be a possible barrier for the

intenders to engage in the behavior, and a possible resource for the actors (Schwarzer et al., 2011).

In this study, barriers and resources is a construct that affects planning and action through external factors that is in collaboration with another model, the Green consumption behavior-testing model (Nguyen et al., 2019). The construct chosen from previously mentioned model is Green Products Availability, which can be seen as a barrier or resource and therefore is included in this part of the HAPA model. The construct is originally stated as a hypothesis: “The availability of green products moderates the relationship between the green consumption intention and the actual behavior such that the more the green products are available, the stronger the positive relationship between the intention and the behavior” (Nguyen et al., 2019, p. 121). In this study, the construct will provide the opportunity to explore if, and how, the availability of secondhand clothes affects the IB gap. The construct strengthens the focus on the actual availability of secondhand clothes. Instead of solely looking at social support, factors such as the availability of secondhand stores, availability of style and size, and if friends and family purchase secondhand will be explored, i.e. factors that is related to barriers and resources that each consumer experiences. A resource for one consumer could be a barrier for another, and through a qualitative study there is an opportunity to explore what each consumer thinks and feel. According to Diddi et al. (2019) the perceived lack of variety and style was one of the things that affected the consumer to not engage in sustainable clothing consumption, which supports the decision of adapting the barriers and resources into this consumer behavior study.

2.6.4 Task Self-Efficacy

Figure 6: Task Self-efficacy Construct in The Adapted HAPA Model

In the original HAPA model (Schwarzer et al., 2011), task self-efficacy is also called motivational self-efficacy and is related to the phase of goal setting. It affects both the Intention and the planning construct. The quantitative study is measuring this construct through the statements “I am certain…” with the alternatives of “… that I can be physically active on a regular basis, even if I have to mobilize myself” and “… that I can be physically active on a regular basis, even if it is difficult” (Schwarzer et al., 2011, p. 165). In other words, task self-efficacy is about whether or not a person believe that he/she can perform the task, even if the task is difficult in some way.

In this qualitative study, the construct will be explored in the way it affects the planning stage since the focus will be on the actual gap between intention and behavior. For example, high task self-efficacy affecting planning could be that the consumer feels like he or she can purchase secondhand clothes even if it will require more effort compared to consuming “regular” clothes. Low task self-efficacy could be that the consumer does not think that he or she is able to purchase secondhand clothes since it requires more effort and therefore decreasing the chances of consuming secondhand.

The importance of self-efficacy in consumer behavior has been shown in the exploratory research of Garlin and McGuiggan (2002). Their study showed that it is practical for marketers

when it comes to implications to have the knowledge of how self-efficacy affect the consumer. Self-efficacy in general has been proven to have a large impact on the performance of different task, no matter if it is task self-efficacy, maintenance self-efficacy (see section 2.6.5), or recovery self-efficacy (see section 2.6.6) (Bandura, 1991; Bandura & Locke, 2003).

2.6.5 Maintenance Self-Efficacy

Figure 7: Maintenance Self-efficacy Construct in The Adapted HAPA Model

In the original HAPA model (Schwarzer et al., 2011), maintenance self-efficacy is one of two parts of volitional self-efficacy. It affects planning and action through the person's beliefs in him- or herself being able to proceed with performing the behavior, even if there are or will be decreasing success results. It is measured through the question “I am capable of continuous physical exercise on a regular basis…” with following alternatives “… even if it takes some time until it becomes routine” and “… even if I need several tries until I am successful”. (Schwarzer et al., 2011, p. 165). In other words, maintenance self-efficacy is about how a person perceives his/her own ability to maintain the behavior.

In this study the maintenance self-efficacy is a construct that affects the planning and the action through the consumers perception of believing that he or she can purchase secondhand even if it will take some effort to change the mindset when looking for clothes, or even it the consumer has to visit several stores to find what he or she is looking for, i.e. even if he/she experience

setbacks or failures. In contrast to task self-efficacy, that is more focused on the consumers perception to start consuming secondhand, the maintenance self-efficacy is about the consumers perception of being able to make this a routine when he or she starts consuming secondhand clothes, i.e. maintaining the behavior.

2.6.6 Recovery Self-Efficacy

Figure 8: Recovery Self-efficacy Construct in The Adapted HAPA Model

In the original HAPA model (Schwarzer et al., 2011), recovery self-efficacy is the second of the two parts of volitional self-efficacy. It is affecting the action, thus the actual behavior, and is measured by statements such as “I am confident that I can resume a physically active lifestyle, even if I relapse several times” (Schwarzer et al., 2011, p. 165)

In this study it is a construct that affects the action of the consumer, i.e. the behavior to purchase secondhand clothes. Recovery self-efficacy is about the consumers perception of being able to proceed to purchase secondhand even if there are times when he or she has a relapse, i.e. purchase newly produced fashion. Even if the consumer would end up in situations where he or she opt out secondhand and purchase from a regular store, the consumer believes that he or she will not give up the behavior to purchase secondhand the next time. It is about the consumers beliefs in themselves to take a setback or failure and keep on going towards the goal of purchasing secondhand. A setback in terms of purchasing secondhand would mean that the

consumer encounters some kind of problem, for example there are no items in the right size, but there is a solution that still enables secondhand purchasing, which is the intended behavior. A failure in terms of purchasing secondhand would mean that the consumer encounters some kind of problem that result in a purchase of newly produced fashion, which is not the intended behavior.

2.6.7 Planning

Figure 9: Planning Construct in The Adapted HAPA Model

In the original HAPA model (Schwarzer et al., 2011), planning is divided into action planning and coping planning. It is affected of intention, task self-efficacy, maintenance self-efficacy, and barriers and resources. Action planning is the when, where and how to perform the behavior. It is measure through the question “For the month after the rehabilitation, I have already planned …” with answers such as “… which physical activity I will perform”, “… where I will be physically active”, and “… on which days of the week will I be physically active” (Schwarzer et al., 2011, pp. 164-165). Coping planning is the planning of handling problems along the way to recovery, to be able to actually perform the behavior despite these problems. It is measured through the question “I have made a detailed plan regarding..” with the options for answer “… what to do if something interferes with my plans”, “… how to cope with possible setbacks”, and “… what to do in difficult situations in order to act according to my intentions.” (Schwarzer et al., 2011, p. 165)

In this study, action planning is related to when, where and how the consuming of second-hand clothes will occur. It could for example be planning to visit secondhand stores further away from home to be able to find other types of clothes and such a trip has to be planned in advance. Coping planning is related to how the consumer will deal with problems that will or could occur. For example, the consumer plans to visit the second-hand store 40km from home if the one 2km from home is not providing the clothes he or she is looking for. Or it could be that, if the secondhand store cannot provide the consumer with a specific piece of clothing for today’s party, he or she will borrow something from a friend. Planning to overcome obstacles but still remain on track to perform the behavior. The choice of adapting planning from HAPA into consumer behavior is supported by the intention-behavior mediation and moderation model of the ethically minded consumer (Carrington et al., 2010). That model is containing a factor called implementation intentions and is affecting the IB gap through the consumers planning of when, where and how he or she will actually perform the intention, which is the same as HAPA’s action planning. Implementation intentions, in its original model, comes after intention and is affected by actual behavioral control and situational context. Actual behavioral control could be compared to HAPA’s three self-efficacy construct in combination with barriers and resources. Situational context could also be compared to HAPA’s barriers and resources, and since self-efficacy and barriers and resources both affect the planning construct in HAPA, the combination of the Implementation Intention and the planning construct in HAPA is a good fit. Implementation intentions is explained as “I will perform action X at time Y or when situation Z arises” (Dholakia et al., 2007, p. 344), which could be that a consumer develops an implementation intention of: “When I need to purchase a new pair of jeans I will go to a secondhand store and look for a pair of jeans that looks appealing to me” (Carrington et al., 2010, p. 144). According to Gollwitzer and Sheeran (2006) this way of planning is increasing the likelihood of actually realizing the intentions and reaching the goal, which proves the importance of the construct in the relationship between intention and behavior.

2.7 Consumer Groups

Classification of individuals are a form of segmentation of consumer markets as the consumers are divided into different groups based on how they behave and what factors that influence the

behavior. According to Gunter and Furnham (1992), classifying consumers through marketing segmentations can help communicators to predict behaviors and adjust their advertising and marketing by determine what factors that distinguish a group of consumers from the overall market. Several scholars argue that the profiling of green consumers is more complex than other consumer profiles and psychographic factors are more critical as demographics is not enough to determine the profile of the consumers (Straughan & Roberts, 1999; Wang, 2014; Sharma, 2015). Thus, the bases of behavioral attribute classification, using psychological segmentation is important to understand why green consumers behave a certain way. This method focuses on creating consumers profiles developed from standardized personality inventories, activities, opinions, interest and lifestyles of the consumers (Gunter & Furnham, 1992).

In order to transform the adapted HAPA model from implicit to explicit, individuals are divided into groups that fits into the motivational or the volitional phase (Schwarzer et al., 2011). In the motivational phase, which is the first of the two, one group is formed where individuals are identified as preintenders. In the Volitional phase, which is the second of the two phases, two groups are formed. In the first group, individuals are identified as intenders, and in the second, individuals are identified as actors. According to Schwarzer et al. (2011), tailored stage-interventions is usually subdivided into three groups. The classification of individuals in the original HAPA model aim to assign specific treatments tailored for each group to move individuals closer to behavior. The purpose of this study is to explore the gap between intentions and behavior of the sustainable fashion consumer that already have the intention to purchase secondhand fashion. Thus, the adapted model will focus on the volitional phase where the consumers have the intentions to engage in the behavior and the consumers are subdivided into two groups of intenders and actors.

Intenders are inactive consumers that fit into the first volitional stage of the model, the stage in between intentions and action in the model, i.e. postintentional-preactional stage (Schwarzer et al., 2011). These consumers intend to purchase secondhand fashion, but do not act on it and fail to engage in the behavior. In this study, consumers that purchase secondhand but not on a regular basis and does not consider it to be a part of their shopping routine will be identified as intenders. Thus, consumers with different behaviors can be classified as intenders. People that have never purchased secondhand fashion before but have the intentions to do it, and, people that purchase secondhand but not on a regular basis will be identified as intenders. In addition

to that, consumers who classify into the volitional phase, but not the action construct will be identified as intenders, i.e. inactive people. Lastly, intenders will be classified based on their psychological states, i.e. mindset, knowledge, and how it differs from active people (actors). According to the original HAPA model, these consumers classified as intenders benefit more from planning the behavior and translate their intentions into action rather than getting a messages of outcome expectancies (Schwarzer et al., 2011). Hence, the consumer in the group of intenders benefit from planning sustainable fashion consumption more than getting a marketing message that inform about the effectiveness and positive outcome of the behavior.

Figure 10: Postintentional-preactional Stage (Intenders)

Actors are active consumers that fit into the second volitional stage of the model, the goal of the model and the stage where the action takes place, i.e. actional stage. These consumers intend to purchase secondhand fashion and do act on their intentions. In this study, consumers that purchase secondhand on a regular basis and consider it to be a part of their shopping routine will be identified as actors. Thus, consumers can be classified as actors even if they engage in consumption of newly produced fashion as long as secondhand is a part of their regular routine and they make sustainable purchases on a regular basis. This means that people that only purchase secondhand fashion, and, people that purchase secondhand fashion on a regular basis will be identified as actors. In addition to that, consumers that classify into the volitional phase and the action construct will be identified as intenders, i.e. active people. Lastly, intenders will be classified based on their psychological states, i.e. mindset, knowledge, and how it differs

from inactive people (intenders). Actors benefit from developing strategies that prepare them for setbacks and adapt to internal and external factors influencing the situation (Schwarzer et al., 2011). Hence, Interventions for this stage should aim to stabilize and maintain the behavior to avoid consumers falling back into the gap.

Figure 11: Actional Stage (Actors)

2.8 Research Model

Theadapted HAPA model will be applied in order to explore internal and external factors that influences the IB gap in sustainable fashion consumption. How do the factors identified in the adapted HAPA model influence consumers? And how does it create a gap between the intention to purchase secondhand fashion and actually engage in the behavior? Further, the adapted HAPA model will be applied when exploring the perspective of two different consumer groups: those who intend to purchase secondhand (intenders) and those who actually purchase secondhand (actors). This in order to understand the difference in the behaviors and what factors that cause the dissonance between intentions and behavior for those who fail to translate their intentions into action. By identifying barriers contributing to the gap, the researchers can determine a basis for marketing intervention. The marketing interventions for each group aim to move the consumer closer to engage in behavior and bridging the IB gap. This in order to help marketing management to set up strategies for sustainable fashion consumption, change

the mindset of the consumers and move the consumer group of intenders toward the actional stage where the consumer engage in sustainable fashion consumption and purchase secondhand fashion.

Figure 12: Research model

3. Research Methodology

In this chapter, the researchers provide information about the methodological reasoning that was done in relation to the purpose of the research. Starting with the philosophy who served

as a guidance for remaining decision, followed by design, approach, and research strategy. Next the researchers present the research method chosen and sample strategy together with sample selection. The chapter present the data collection techniques of both primary and secondary data, such as literature review and qualitative interviews. Lastly, the choice of data analysis is presented together with how the researchers assessed research quality and what precautions that was made in order to ensure an ethical research.

3.1 Methodological Reasoning

3.1.1 Research Philosophy

According to Saunders et al. (2016), research philosophy is conducted of different assumptions that the researches has about human knowledge, realities and how personal values influence the research process, or with other words; epistemological, ontological and axiological assumptions.These assumptions will be the foundation for method, strategy, data collection and analysis, i.e. the philosophy is guiding and/or influencing the researcher in the way he or she constructs and perform the research (Saunders et al., 2016). Therefore, it is important for researcher to understand their own beliefs and assumptions about these things, to be able to make the right choices on the road to a complete research. This research has a philosophy of interpretivism which in general, according to previous research, secures a deep understanding by using several methods, techniques and tools (Denizin & Lincoln, 2011). The philosophical approach is based on the three categories of assumptions, starting with ontology.

Ontology is the assumption about nature of reality (Saunders et al., 2016). According to a previous study (Guba & Lincoln, 1994; Krauss, 2005), the interpretivism believes that the reality is socially constructed, multiple and subjective. This means that researches with a philosophy of interpretivism believes that the reality is based upon each person’s own experience, i.e. biased through that person. Therefore, the reality is not one single, but rather several different since each and every one could have different experience of things and therefore have different realities. This is in line with the beliefs of the researchers of this study. The findings of this study will set the standards of how the researchers experience what the reality looks like. The researchers also believe that each person being interviewed for the study

will have different version of what the reality looks like in relation to the field being explored and that these versions is socially constructed through each person’s social life experiences.

Next is epistemology which is the assumption about knowledge (Saunders et al., 2016). According to Darby et al. (2019), an interpretive research has the epistemological assumption that knowledge being generated is time-bound and context-dependent. They also state that the view of causality is multiple and that the research relationship is interactive and cooperative. This is in line with the beliefs of the researchers of this study. The researchers are of the beliefs that the findings of this study are accurate right now and might not be true in the future, the same is true related to context. This is also shown through the fact that previous research has been done, but not in this particular time period and not on this specific topic and the researchers are not of the beliefs that previous research can be directly applicable on this topic, and therefore need to explore the topic using parts of different previous research. That the view of causality is multiple is something the researchers holds true in this study through the fact that they believe that not only one thing is affecting the consumer through the change of behavior, nor does the same things affect each consumer in the same way. The researchers also believe that the research relationship is interactive and cooperative which is shown through the fact of gathering data being done through in-depth interviews.

Third and last is axiology, which is the values and ethics for both the researchers but also the participants in the research (Saunders et al., 2016). According to previous research, interpretive research has the goal of empathetic understanding in order to produce meaning and push boundaries, making it more like a process and less like an end product (Denzin, 1984). This goes in line with this particular study since the focus is on understanding how the consumers think and behave, but also since it is an exploratory research which is of purpose to pave the way for a quantitative theory testing study as further research.

3.1.2 Research Design

The research design in general is the first step when conducting the process of the research after establishing the idea and research question of the study, according to Toledo-Pereyra (2012). The research design of this study, based on the research questions and purpose, are exploratory. According to Stebbins (2011), “social science exploration is a broad-ranging, purposive, systematic, prearranged undertaking designed to maximize the discovery of generalizations leading to description and understanding of an area of social or psychological