“I survived”: Coping Strategies for Bullying

in Schools

A Systematic Literature Review from 2009-2020

Arfa Imran

One-year master thesis 15 credits Supervisor

Interventions in Childhood Mats Granlund

Examinator

Spring Semester 2020 Madeleine Sjöman

SCHOOL OF EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION (HLK) Jönköping University

Master Thesis 15 credits Interventions in Childhood Spring Semester 2020

ABSTRACT

Author: Arfa Imran

I survived: Coping Strategies for Bullying in Schools

A Systematic Literature Review from 2009-2020

Pages: 30

Bullying has been recognised as the most severe problem for children in school

settings in the past few decades. It can have a tremendous psychological impact on the child, which can affect not only his or her learning but also everyday functioning and overall well-being. Understanding how students handle ‘bullying incidents’ in different situations may help researchers set new foundations to develop more comprehensive and effective educational and intervention programs.

The purpose of this systematic literature review was to investigate the use of different coping strategies for bullying in middle and high school children. A search for

scholarly articles evaluating such measures has been carried out in ERIC, SCOPUS, and PSYCH INFO, which resulted in seven articles. 12 coping strategies emerged as a result which included self-control, compliance, relaxation, retaliation, seeking

assistance, distancing, concealment, verbal aggression, blame, victimization, self-harm, and drug abuse. Coping strategies for bullying in these articles covered a wide range of essential aspects to counter bullying incidents and stress, bullying definitions, and bullying situations. Limitations and implications for future research and practice have been considered.

Keywords: bullying, victimization, victims, coping, strategies, mechanisms, school, middle school, high school

Postal address Högskolan för lärande och kommunikation (HLK) Box 1026 551 11 JÖNKÖPING Street address Gjuterigatan 5 Telephone 036–101000 Fax 036162585

Table of Contents

1.Introduction ... 4 1.1 Bullying ... 4 1.2 Types of Bullying………..4 1.3 Coping Behavior………5 2.Aim………...8 3. Method………53.1 Systematic Literature Review………..6

3.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria……….. 9

3.3 Search Procedure………..10. 3.4 Data Extraction……….12 3.5 Quality Assessment………..12 3.6 Data Analysis……… . 16 4.Results………16 4.1 General Characteristics……….17 4.2 Main Findings………...21 4.3 Bullying Situations………...26

4.4 Different Locations for Bullying………..26

4.5 Different Reasons for Bullying………....26

5. Discussions………27

5.1 Reflections on findings and practical implications………...28

5.2Methodological issues……….…29

5.3 Limitations………. 29

6.Conclusion……….31

7.References………..31

Appendix A Extraction protocol for full-text screening………...38

Appendix B Thematic Analysis of Coping Strategies……….39

Appendix C Types of Bullying and the Coping Strategies employed……….41

1.Introduction

1.1Bullying

School bullying may not have been looked at as a problem that could impact or affect education, but sadly it is not the case anymore. Research has proved that “Bullying” has emerged as one of the most serious problems of recent years, that has plagued the world of education. Research has proven that bullying behaviours often result in both serious short- and long-term outcomes that are not only damaging for the victims, but the perpetrators are also affected by psychological distress. Besides, Craig (1998) found that repeated

victimization in children can lead to problems such as stress, anxiety, and depression. Bullying is also associated with peer rejection, an early dropout from school, criminal

behaviour, adult psychopathology, and even suicidal behaviour in most extreme cases. (Crick, 1995; Parker and Asher, 1987). The most frequently occurring type of traditional bullying was, name calling, followed by threats and intimidation, then physical bullying and social exclusion (Green et al., 2010).

Educationists have defined bullying in many ways, but they have agreed upon some common aspects: such as unwanted, abusive, aggressive, and repetitive behaviour to harm or terrorize someone. It is anger and aggression towards individuals with weak self-defence, with an imbalance of power between the aggressor and victim (Nansel et al., 2001; Naylor, Cowie, & del Rey, 2001; Olweus, 1994).According to Olweus (1993) bullying behaviour should essentially consist of three elements: it must be harmful, repetitive and it should consist of a difference of power which can be physical, social, or any other, between the bully and the victim. Bullying in school is a severe problem affecting between 7 and 35% of children and adolescents in Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, and Japan (Smith et al.,1999).

Since bullying is associated with severe mental and physical health issues in children therefore, educationists and health workers must have a good understanding of the problems related to bullying. This can help not only to develop prevention programs but also intervention outcomes that can benefit victims and bullies equally.

1.2 Types of Bullying

“Bullying behaviour” can be seen in many different forms. It may be demonstrated through physical or verbal abuse, like being regularly kicked or punched, continuous teasing, name- calling, swearing, being threatened, spreading lies and false rumours , passing on nasty notes, vandalising or even taking one's property by force, or being isolated from groups and

activities (Fitzgerald,1999).There was a clear distinction made by Olweus (1993) between “direct bullying” (open attacks on a victim) and “indirect bullying” (e.g., social isolation) and he laid more importance on indirect bullying due to its invisible nature. Other researchers identified three types of bullying (Fitzgerald, 1999) as physical (e.g., beating, punching, pushing, kicking), verbal (e.g., nasty name calling, verbal abuse, threatening, insulting, spreading gossip or rumours), and psychological (e.g., damaging or vandalizing one's

possessions, writing threatening or frightening notes, isolating socially). Hawker and Boulton (2000) categorized five different types of bullying: (a) indirect, (b) relational, (c) physical, (d) verbal, and (e) generic (e.g., making fun of, harassing, or tormenting).

According to the researchers the most common form of bullying is the physical bullying, However, indirect bullying, such as name- calling and teasing, may also be as common as physical bullying (Seals & Young, 2003). Whereas, indirect bullying behaviours, such as verbal bullying or social exclusion, might be more harmful and may not decline with age (Bauman & DelRio, 2006). Besides, boys tend to use physical power, and girls tend to display verbal types as an indirect form of bullying (Rivers & Smith, 1994).

The continuous abusive encounters may result in devastating situations for the victims that may cause anxiety, anger, depression or other negative thoughts and feelings that can cause extreme reactions towards others or oneself (Carney, 2000; Hazler, 1996, 1997). Self-declared victims have reported feelings of vengeance, anger, self-pity (Kempf, 2011) and public humiliation which can lead to tragic consequences in many cases (Rigby and Slee, (1999). As a result, humiliation and self-pity emerge with suicidal ideation (Stillion, 1994) In contrast, the related feelings of anger and vengefulness have led to aggression against the school peers (Elliot, Hamburg, and Williams, 1998). How victims cope with bullying is, therefore, essential.

1.3 Bullying Situations

Many theories, models and programmes have emerged in the 1990s with guidance on how to prevent or intervene in peer-on-peer abuse situations (Hazler, 1996; Olweus; 1997, Smith et al., 1999). Each of these many programmes places initial and continuous emphasis on the ability of adults and youth to recognize problem situations as they occur rather than placing sole emphasis on identifying bully or victim characteristics. Vaillancourt et al, in 2010 explained previous studies provided by researchers to identify bullying locations in school children are limited to responses based on the given choices, and not the experiences of the children. Children often experience peer victimization at or near their school in areas of limited adult supervision, such as the playground, cafeteria, bathroom, or hallway (Beale & Scott, 2001). Rapp-Paglicci et al in 2004 reported that very few studies have thoroughly explored dangerous locations at schools, but those that have found hallways, cafeterias, bathrooms, classrooms, playgrounds, and locker rooms to be dangerous areas or “hot spots” where bullying tends to occur. They further elaborate that bullying usually occurs at places where teachers and authorities are absent.

Bullying situations may also look at the different reasons why school children are bullied. A growing number of researches have concluded that minority youth maybe the victims of peer victimization because of their racial, ethnic, minority background, rather than personal reasons (Lai and Tav 2004).

1.4 Coping Behaviour

Coping is defined as the cognitive or behavioral effort to eliminate the negative emotions elicited by excessive demands (Monat and Lazarus, 1991). Lazarus (2006) has defined coping as a person’s effort to handle environmental stress and to deal with the emotions that are a result of the stress. The ability to cope with the stressful situations of life is essential in promoting psychological and emotional health (Lazarus, 2006).Individuals’ definitions of

coping strategies may change from one context to another. Thus, some strategies may be used in seriously threatening situations, while quite different strategies are used to handle everyday problems (Lazarus, 1999). To focus on general coping strategies has occasionally been

considered as appropriate when describing coping in situations of chronic or prolonged stress (Gottileb,1997). It has been further elaborated as the person's cognitive and behavioural efforts to reduce or tolerate the internal and external demands of the person-environment transaction that is appraised as tiring or exceeding the person's limits.

Coping has two significant functions: dealing with the problem that is causing distress (problem-focused coping) and regulating emotion (emotion-focused coping)

(Folkman and Lazarus, 1986). Previous research (e.g., Folkman & Lazarus, 1980, 1985) have shown that people use both forms of coping in almost all types of a stressful situation.

The Problem-focused forms of coping includes aggressive attempts to change the situation, as well as calm, sensible efforts to solve the problem. The emotion-focused forms of coping include distancing oneself, self-controlling, seeking social support, escape-avoidance, accepting responsibility, and positive reappraisal.

Folkman and Lazarus (1980) developed a scale called the Ways of Coping Checklist, which assessed coping based on their Transaction Model. This scale examined emotion-focused and problem-focused coping using a 68-item checklist, that described different types of coping behaviours. The stress and coping theory on which the 68-item scale was based, required that the subject focused on a current serious stressor. Initially, it had two scales the problem-focused scale: that dealt with managing the source or the problem, and the

emotion-focused scale: that handled regulations of emotions. The emotion-focused theme

mainly addressed, strategies that employed cognitive or behavioural techniques to handle the emotional outcomes of stress. The problem-focused category involved problem-solving approach that specifically attempted to solve the problem. The scale used eight categories to examine coping strategies. Confrontive coping, taking aggressive action to change a situation; distancing, detaching oneself from the situation and minimizing its importance;

self-controlling, regulating ones feelings and emotions; seeking social support, discussing the problem with somebody else and receiving emotional and informational support; accepting responsibility. Recognizing how one contributed to the problem and attempting to make a change; escape-avoidance, thoughts and behaviours to escape and avoid the problem; planful problem solving, analysing the issue to resolve it; and positive reappraisal, thinking

positively about the situation (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980; Frydenberg & Lewis, 1991; Ways of Coping Questionnaire, 2009).

The second theory of coping that contributed to the development of the present study suggested that coping could be divided into two orientations aimed at addressing stress: approach and avoidance (Roth & Cohen, 1986). Approach coping strategies focussed on the threatening stimulus and addressing the threat directly. Approach strategies also included taking action that could resolve a stressful situation but could also lead to increased anxiety resulting from facing the distressing situation. Avoidance strategies involved staying away from the stressor and escaping the threatening stimuli. Avoidance strategies were associated

with reducing stress, but rarely contributed to a resolution of the problem (Roth & Cohen, 1986) emotions and outwardly directed anger.

Peer victimization, or bullying, is a common problem for children and youth that often requires cognitive or behavioural strategies to deal with negative outcomes. The

methods that are chosen by many students to cope with a stressful problem such as bullying, may vary from person to person and also differ from how they address other distressing events (Skinner, Edge, Altman, & Sherwood,2003). Therefore, it is vital to understand the nature of coping strategies with bullying and the various factors that may influence students’ choices to implement specific strategies. Such factors include how often the student is involved in bullying, either as a victim or as the bully.

With the help of longitudinal studies, Kochenderfer and Ladd (1997) in the USA found that bullying was more persistent for five‐ to six‐year‐old male victims who peers thought “fought back” in response to bullying, compared with male victims of the same age who were perceived by peers as “having a friend help” in bullying situations. Using self‐ and peer‐nominations in a study of 12‐ to 13‐year‐old victims, Salmivalli, Karhunen and

Lagerspetz (1996) in Finland found that “helplessness” and “counter‐aggression” in female victims were behaviours associated with initiation or continuation of bullying. In contrast, for male victims only “counter‐aggression” was associated with this. Behaviours related to diminished or discontinued bullying were a lack of “helplessness” for female victims, and “nonchalance ” as well as a lack of “counter‐aggression”, for male victims.

According to a study cited in more comprehensive research (Smith et al.,2001), the most common coping methods used by victims include: ignoring the bully, asking them to stop, requesting an adult for help and fighting back; and the least common was running away, asking friends for help and crying. Researches, at the primary and secondary school level have shown that, in general, some of the successful strategies include informing a teacher, asking friends for help, and ignoring, whereas, some unsuccessful strategies are fighting back, acting passive or showing helplessness.(Hunter et al.,2004; Naylor et al., 2001; Salmivalli et al., 1996;Smith et al., 2001, 2004).

Confiding in someone about a bullying experience is one of the many strategies, or coping mechanisms, victims can use to reduce their problem and manage the stress of being bullied (Kochenderfer-Ladd & Skinner, 2002). Few systematic reviews so far are based on how bully-victims themselves perceive bullying and strategies for coping with bullying. Such reviews require that primarily qualitative studies focusing on children’s perceptions and

2. Aim

The purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyse what previous qualitative research studies report about the coping behaviour pattern used by children in a bullying encounter. And, how bullying has been defined by children in the researches.

The three research questions are as follow:

1. What coping behaviour, reported by previous studies, is used by school children to handle bullying in a situation?

2. How has bullying been defined by the researchers to the participants in these studies? 3. How a bullying situation is described by the victims in these researches?

3

. MethodThe research question has been devised using the PEO (population, exposure, outcome) method. This framework is more suitable to formulate questions for qualitative research.

Table 1 PEO method

PEO

What coping behaviour (Outcome), reported by previous studies, is used by school children (Population) to handle bullying in a situation (Exposure)?

3.1 Systematic Literature Review

To answer the research questions a systematic literature review was conducted used. A systematic literature review (SLR) identifies, selects, and critically appraises previous research to answer a formulated question (Dewey, A. & Drahota, A. 2016). A systematic review is research on its own but can address much broader questions than empirical studies can (e.g. uncovering connections among many empirical findings (Baumeister & Leary, 1997). According to the nature of the research questions for this paper, a qualitative approach would be more suitable for the systematic review. The qualitative approaches are more in- depth and insightful findings of the quantitative study, whereas, the quantitative approach can be used to verify the findings from a qualitative study (Aveyard, 2014).

3.2 Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The criteria used for the inclusion and exclusion during the screening process were established based on the three questions: What coping behaviour, reported by previous studies, is used by school children to handle bullying in a situation?

How has bullying been defined by the researchers to the participants in these studies?

How a bullying situation is described by the victims in these researches? The review aimed to identify the coping methods used by school children during bullying situations in school premises. The review included studies with typically developing school children and the focus was on how they coped with verbal, physical or relational bullying. The chosen time frame for the studies spanned from 2009-2020. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in the Table 2.

Table 2

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Topics Inclusion criteria Exclusion criteria

Population

Age

Typically developing school children

8 -17 years

Elementary, middle school or upper- middle school

1-7 years

Exposure Bullying emotional,

physical, and relational

Articles that only include cyberbullying Outcome Personal Coping strategies,

behaviour patterns,

Articles that only include interventions by professionals or family

support

Design Qualitative (empirical) Quantitative Empirical studies

Publications Peer -reviewed, academic journals, systematic reviews

in English

reports, books and other non-academic articles in

other languages

Year 2010-2020 Articles before 2010

3.3 Search procedure

The database search for this systematic literature review began in February 2020. As shown in figure 1, the databases used for the search were ERIC, PsycINFO, and Scopus. In the database Eric, the Thesaurus search was performed, in combination with free search terms, while in Psych INFO and Scopus databases only free search terms were used in advanced search options. All the searches were limited to scholarly articles published in the English language. The search words used in the database ERIC were “bullying or harassment or teasing” AND “coping strategies or coping skills or coping or cope” AND “school "Bullying" AND "Elementary schools" AND "Middle schools" AND "coping strategies" OR "coping skills".” The search gave 66 results. The search words for psych INFO were “school bullying” AND “coping strategies in students”,” which turned out 53 articles.

The search terms used for Scopus were “Coping measures OR strategies

“AND “Bullying” in AND “schools” “coping AND experience”.” The initial databases search identified 165 articles; and were screened for titles and abstracts, 15 remaining articles were

screened for the inclusion criteria. The remaining 10 full-text articles were further screened for eligibility, 3 were excluded during the data extraction process. The three excluded studies emphasized more on stress and coping strategies, related to reasons and factors other than bullying and peer victimization at school such as examination, peer-pressure, depression and competition etc. However, there was some material related to bullying in these studies.

Figure 1 Flow chart showing the selection process of the articles

The remaining seven articles were included in the narrative synthesis and

summary. Seven articles were identified that answered the research questions and matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria; these were qualitative evaluations of bullying experiences and the coping strategies or behaviours employed by the school going children and

adolescents. These articles were published between 2009 and 2020 in journals related to bullying, harassment, and peer victimization.

Total number of records from combined databases

(n = 165)

Records screened for titles and abstracts

(n = 165)

Records excluded based on titles and abstracts

(n = 150)

Full-text articles excluded (coping strategies used for reasons other than bullying)

(n =3) Full-text articles assessed for

eligibility (n =10)

Studies included in qualitative synthesis

(n = 7)

ERIC PsychINFO SCOPUS

Records screened with inclusion criteria

(n=15)

Duplicates removed (n=5)

3.4 Data Extraction

The extraction protocol for full-text articles has been presented in a table in Appendix A. The information that has been extracted included title of the article, authors, year of publication, country where the study took place, aim or the purpose of the study, research questions, study design, general information about the participants (number, age, gender, personality

traits),recruitment procedure of the participants, type of school, type of bullying, definition of bullying, situation for bullying, coping strategies for bullying, practical implications of the study, limitations and conclusions discussed in these articles and quality assessment criteria.

3.5 Quality Assessment

Quality assessment of the included articles was performed using the CASP checklist for qualitative research (CASP, 2018), adjusted to fit the context of this review. An overview of the Quality Assessment is presented in a table in Appendix B.

3.6 Data analysis

Data analysis was performed during and after the data extraction. An identification number was assigned to each study (as shown in a table in Appendix B) and was used onwards instead of referencing. Information about the methodology and the data in the studies for bullying was thoroughly analysed, to get an overview of what types of bullying encounters that reported, how the encounters were coped with, and how they were questioned by the researchers in these studies.No coding or analysis software was used during the procedure. The first stage of the analysis consisted of engaging in repeated immersive reading of the entire verbatim

transcripts to gain a thorough understanding of its contents. In the second stage the citations from the interviews were read thoroughly, and the meaning units were highlighted. In the third stage the meaning units were summarised to more specific statements. Following, these statements were coded and put into their respective themes (as shown in Table 3). The codes and themes were derived from the 68 items from WCCL (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). For example, retaliation was taken from ‘stood my ground and fought for what I wanted ’,

seeking social assistance was derived from ‘talked to someone who could do something about

the situation’, relaxation was formed from ‘came up with a couple of different solutions to the problem’ and self-blamed was derived from ‘criticized or lectured myself. ‘To answer the second research question, questions, and statements to describe bullying to the participants, used by the researchers were analysed and the bullying situations reported in the context of those questions were also analysed. There were no descriptions or definitions of the term

‘Bullying’ found in the seven studies reviewed for this systematic review. For bullying situations content analysis was performed which consisted of three steps (see Table 3). The content from the transcripts was read thoroughly. The meaning units consisting of responses related to the actual incidents or situations of bullying were colour coded. And finally, these codes were placed in more specific themes.

Table 3 Examples of Themes for Coping Strategies derived through Content Analysis

Study Citations Codes Themes

1 ‘I always stop because then if you get

into a fight you get suspended or you get in trouble from your parents and all that, so I think ahead when I’m getting mad’.

Keeping control of the emptions

Self-Control

2 ‘When I started to learn bakery, I was

new there, they were all babes there and I was such a country girl and I knew that they didn’t like me. Actually, I was just such a quiet student and I didn’t do pretty much anything.’

Cursing or blaming oneself

4.Results

4.1 An overview of the Quality Assessment

There was a precise aim given for six of (one, two, three, four, five, and six) studies that were included for the review. Only one study (seven) did not mention a well-defined aim or a research question. An appropriate qualitative approach and qualitative research design was clear in all seven studies. The ways of data collection were mostly observations, records, structured and semi-structured interviews, that were audio and video taped.

In all the studies the sample population consisted of participants who were victims of bullying or peer harassment either at the time of the study or in the past. Therefore, a purposeful sample of voluntary participants was used in studies one, three, four, five and six. In contrast, a convenience sample due to the non-availability of voluntary participants, was used in studies two and seven. However, the relationship of the researcher to the topic has not been defined in any of the studies. There was a clear and detailed description of the

technique and steps involved for data analysis and sufficient data was provided to support the findings of all the studies. Consent for participation was taken from the participants or the guardians and some concerned institutes. However, there was no mention of the consent for the research to take place for any of the studies. At the end of each study specific findings were given along with its value and significance to the stakeholders.

The comparison was made based on the percentage of criteria the articles fulfilled on the CASP (2018) checklist. Five of the articles are considered to have good quality (80% of the quality criteria fulfilled), one article is of moderate quality (50% quality criteria fulfilled) and two articles were of low quality (<50% of the quality criteria fulfilled). Since the remaining number of articles after the inclusion and exclusion criteria in this

systematic literature review was small, therefore, no articles were excluded due to low quality. The quality assessment overview is shown in a table in Appendix B.

4.2 General Characteristics of the studies

Out of the seven studies included in this systematic literature review, two were conducted in the USA, two in Australia, two in Taiwan and one in Estonia. The participants for all the studies belonged to public schools from primary to the high school level. Whereas, two schools were vocational schools (two, four). Data from three studies were collected from schools located in economically disadvantaged areas (three, five and six). For the other studies, there is the economic situation of the schools or the area is not mentioned. ( see Table in Appendix C).The recruitment of the participants for most of the studies (one, four, five and

six) shows some similar features, such as the participants were victims of either long or short term bullying and were located by the school teachers, administrators, heads and counselors or even parents through observations or school records. One study (three) has used a

convenience sample, i.e., participants with easier access for the interview. One study has only interviewed students to know the increase in dropouts from a vocational school (two), and finally, one study (seven) does not specify how they sampled the interviewees. In all the studies, the average age of the participants ranged between 9-15 years, apart from one study (six) in which the highest age range was up to 18 years.

4.3 Reasons for Bullying

The most commonly present types of bullying were verbal and physical abuse, whereas relational abuse was also notified in studies one and two. Three studies did not mention any personality traits of the victims that were seen to be targeted by the bullies (one, three and seven), whereas the study two shows that victims of quiet and submissive nature were targeted more. Also, students that were unfit for a group were often subjected to bullying. Study four mentions students of smaller and weaker physiques were more vulnerable to bullying. Moreover, students with disabilities were often targeted. A lot of students were victimized due to their race, colour, appearance, size, clothes or even skin condition, less intelligent or smart students as well as more intelligent students were equally bullied. Siblings with disabilities and family characteristics were also a reason for bullying for some students (five).

4.4 Main Findings

The self-reported strategies used by the students to handle bullying distinctly fall into the problem-focused and emotion-focused categories. However, only three studies (one, three and six) out of the seven mentioned their use (as shown in table 5). Self -control, compliance, retaliation, verbal aggression, and victimization are all problem-focused strategies.

Meanwhile, relaxation, concealment, selfblame, and drug abuse are emotion -focused strategies (one). Whereas, seeking social support and distancing were both used as problem-focused and emotion-focused strategy concurrently. In study three all the strategies used were based on problem-focused approach, whereas strategies were not specified as emotion-focused or problem -focused in study six.Twleve themes of coping strategies were identified used by the victims in schools, during or after the occurrence of a bullying situation.

The themes are explained in detail below. Quotations from the student interview citations have been used to examine the results.

1.Self -Control

Self-control defines holding back emotions or exerting restraints. Students have often

explained how much they wanted to react and fight back to end the unpleasant encounter with the bully, but they just feared that it might escalate the problem (one, five, six, seven). There had been times when they wanted to show a power equal to their bully, but they often controlled their anger and aggression due to some reason.

A student reported I always stop because then if you get into a fight you get suspended

or you get in trouble from your parents and all that, so I think ahead when I’m getting mad (one).

Another student stated, It feels like I just want to beat them up or something, but I can’t do that

because I’ll get suspended and get F’s, if you get F’s, you have less of a chance to get a job. (one)

2. Compliance

Some students explained using compliance to end the bullying situation they were going through (one, three, five). These behaviours included giving up, being more submissive and accepting what the bully was saying about them and mostly agreeing with the bully to end the situation. One student state, you are not encouraging it. You’re not giving them anything to ... you’re

not encouraging them (one). In the same study it was reported: If you want people to stop calling

you names. they say you fat, say, Yeah, I’ve been fat for like, ten years of my whole life.

3.Relaxation

Students mentioned many different activities that they used, either to calm themselves or to relieve stress during and after bullying incidents (one, four and five). Mainly they talked about crying, breathing exercises, drawing, listening to music, reading a book, or even using

mindfulness and distraction techniques

.

In study five, a victim stated, I usually draw a picturebecause I am really good at that and I go back after the situation has passed. 4. Retaliation

Standing up for oneself, fighting back verbally and physically, showing aggression, counter-attacking bullies were some of the prevalent retaliating techniques used by many students (one, three, four, five, six, seven). In study one a student responded to this as, You kind of give the bully the power um and ... you can stick up for yourself and show you’re as strong as a bully. You

just either are not showing it or you’re scared. According to many students, fighting back made

them more powerful and helped to end the situation.

A victim added, I feel being targeted is unfair. I believe I have the right to stand on the same ground with them. Thus, I stood up to fight back. The thought of fighting back emerged as a

result of being ridiculed for a long time (four).

5. Seeking Assistance

The technique seeking assistance was the most commonly found in all the studies (one, three, four, five, six, seven) apart from just one (two) study in Estonia, in which the participants mentioned being fearful of informing their families or the school. It included seeking help or informing parents, siblings, or other close relatives of the family. Approaching friends or classmates were also common among students. Very often students sought help from teachers, administrators, counselors, or other school authorities.

In some cases, informing parents and teachers was helpful to many students as they got rescued from the bully by the assistant. A 10-year-old male stated, I talked to my dad about [the bullying] and he helped me out tremendously…he told me that there’s going to be some

bullies out there…he said start speaking up, tell your teachers.(one)

But mostly school authorities had either failed to intervene or overlooked such problems in the schools. Another student in the same study revealed, I react [to bullying] by going to tell someone and, if they’ve been bullied before, then they know the situation and they can help. That’s how I react. I tell someone who knows about bullying.

7. Distancing

This strategy was used by most of the participants in studies one, two, three, five and seven. Some participants thought that it was a better idea to stay at a distance from their bullies or to avoid coming in contact with them in at all. They would try their best to escape and evade their bullies or places where they might come across them. Victims reported letting the

bullying happen, ignoring it, walking away, or just letting it go. A participant who was bullied already in the basic school says that she had to leave her hometown and choose some

vocational school further away, because those girls who bullied her in basic school went to the nearest vocational school (four).Sometimes they reported “running away” as an effective way of ending a stressful incident. In study one, a participant stated that, and then at recess and lunch, when I went outside and I would see them, and then I would just try and walk away.

6. Concealment

This strategy included hiding feelings or the actual event from everyone. It is most evidently seen in the studies one, two and seven. In typical cases the participants mentioned being secretive about their feelings due to shame, embarrassment and fear of being bullied or being harmed by their bullies or by school authorities (in terms of getting suspended) or by the parents (getting reprimanded) or for other reasons. They thought it was best not to share their experiences or incidents with anyone and keeping their feelings and emotions inside to avoid future bullying. For example, an eighth-grade boy felt that, look like they can take it, but deep

inside they are really hurt, and they just don’t say anything (one).

In another study it was explained that most of the subjects experienced harassment as private personal events; none of the boys reported these incidents to the

teaching staff. They explained how ‘‘telling’’ is not an option because of fears that the teacher would then tell their parents—or that they would not be taken seriously by their teacher. In study one, a student said, some try to hide their feelings...so people won’t pick on them anymore’. Another child said, ‘I just try to keep it in, so I won’t say anything to nobody.

8. Verbal Aggression

Studies one and three show the use of verbal aggression to cope with the bullying situation. Students reported that yelling, screaming at, and verbally abusing the bully, to end the bullying situation was always helpful. The participants further added that sometimes the bullying became very difficult to manage and nothing seemed to work and that was the time when they made use of this coping mechanism.

A girl said, the other day someone was getting on my nerves so bad I couldn’t take it

anymore and I yelled at them. Like I couldn’t keep it any longer and I had to yell at them. (one)

Another student reported, ‘It may sometimes get so worse that one starts acting like a bully himself.

“Sometimes you get so mad, you say mean things to them so then you could become the bully instead

of them, pretty much. Another victim reported, I get really mad or I just say something and then they

say something back and that makes me even madder. (one)

9. Self-Blame

Some victims believed that it was their fault that they were bullied or something in them might have annoyed the bully, so they must have done something that caused other people to victimize them.

This strategy was described infrequently by the victims in the studies (one). A victim

narrated: When I started to learn bakery, I was new there, they were all babes there and I was such a country girl and I knew that they didn’t like me. I was just such a quiet student and I didn’t do pretty much anything.

10. Victimization

Some victims in study four reported using this technique. They often became bullies to stop bullying. A student reported that he could not end his miserable situation of being the victim always and he thought of doing something to help himself, otherwise, he would have been continually bullied for his entire life. He explained:For me, I think that perhaps I can learn and imitate the bullies' behaviours so that I can follow their behaviors and say curse words to others who

are also bullied by them. It may make me feel better.

Some of them described it as transfer of target from one victim to another.

I simply wanted to transfer the target of victimization. I realized that, when I began to bully someone else, they (the original bullies) would transfer their target to that one. Then, I would not be their

primary target. They victimized others when they could not control the situation and when they

thought that there was no other way to end it. The screamed and yelled and even engaged in physical fights to cope with the stress or the bullying incident.

11.Self- Harm

This is one of the most negative approaches to deal with bullying among all the other

approaches. Only victims in two studies (two and five) were seen to use this strategy. Victims reported that harming themselves made them relieved of stress and anger that was caused by bullying.

12. Drug Abuse

This coping method is also one of the harmful methods among all the others. Only victims from study five reported using this method to ease their stress and to escape bullying

encounters. They reported depending on drugs and using alcohol to escape the pain the they suffered from after the bullying encounter.

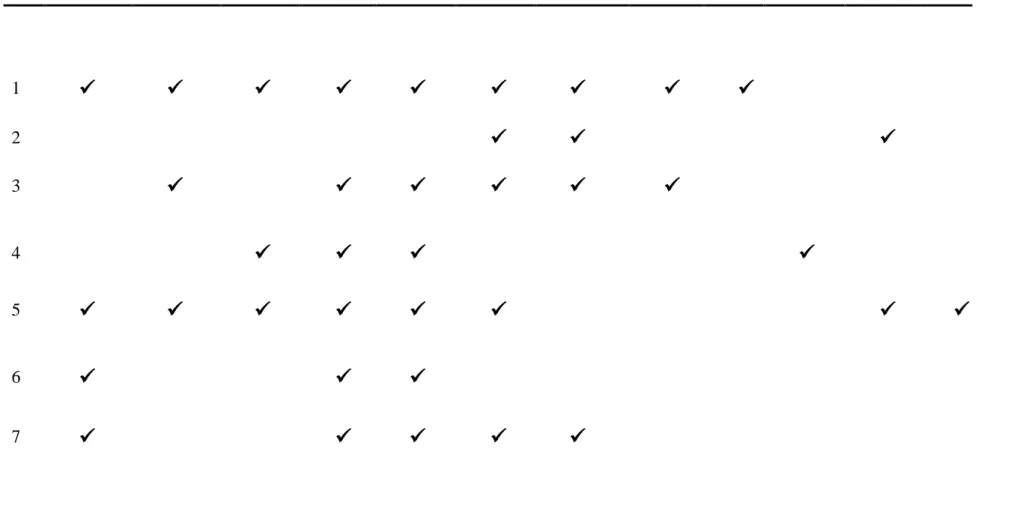

Table 5 Coping Strategies employed by Victims

IN Self-control Compliance Relaxation Retaliation Seeking Assistance

Distancing Concealment Verbal aggression

Self-blame

Victimization Self-harm Drug Abuse 1

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

2✓

✓

✓

3✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

4✓

✓

✓

✓

5✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

6✓

✓

✓

7✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

4.5 Definitions of Bullying

Bullying was not defined by the researchers to the participants at any time, in any of the seven studies. Defining bullying may have yielded different responses from the ones that have been given in the studies. It could help develop a further understanding of what the participants understood by the term ‘bullying’ and the contextual background of the situations.

4.6 Bullying Situations

The open-ended responses of the participants that consisted of content related to the

description of the bullying encounters or situations were divided into two broad categories a) different locations and b) different reasons. However, they were not mentioned in every article. Table 6 shows the studies in which the bullying situations were discussed by the participants

.

4.7 Different locations for bullying

In four studies (two, three, five and seven) students had reported about how they were victimized in different areas of the school and how these areas were chosen by the bullies to assist in the act of bullying. (see Table 6) These areas included classrooms during and after lectures, toilets (mainly girls’ toilets), playgrounds, corridors, dormitories, and hostel rooms. A student reported that, “ One time when I was playing soccer with my friends and other people and someone wanted to play with us but someone didn’t want him to, and I said come on let him play it won’t hurt anyone and the other guy said shut up to me, and I told the guy just play, it won’t hurt you.”( see table in Appendix E)

4.8 Different Reasons for bullying

The participants in the studies (three, four and five) gave many reasons as to why they were bullied and why some victims appeared more vulnerable to the bullies. They explained that they or their friends were victimised due to different colour, race, gender, clothing, disability or medical condition, family background (if someone belonged to a lower-income family) sibling having a disability, being more intelligent or less intelligent, for one’s behaviour or personality and even when someone was trying to save a friend from being bullied.. For example a participant narrated, “I had a medical condition in my leg that went on for a year and a half but my ‘friend’ didn’t seem to get that so after weeks of him kicking my leg and tripping me up I finally turned around and punched him so hard in the chest and cracked his rib.”

Table 6 Bullying situations in different studies

IN

Different Locations Different Reasons1 - -

2 Classrooms,

Playgrounds, corridors -

3 Dormitories, hostels, The difference in ethnicity, intelligence, disability of the victim trying to save friends.

4

Family background of the victim Personal characteristics of the victim 5 Classrooms, Playgrounds, corridors Absence of teachers 6 - - 7 Playgrounds, toilets - Not mentioned

5. Discussion

This systematic review was conducted to review empirical articles based on qualitative methodology published in the 2009-2020, that have analyzed school bullying. Seven studies were identified that qualitatively explored coping strategies used by children in schools in different bullying situations. The studies cover countries with high economic status, across the globe from Australia, Taiwan, Estonia to the USA and therefore, there were many cultural similarities found in these studies. This review can offer several unique contributions to the field of coping with bullying in schools.

According to the results, coping strategies such as self-control, relaxation, concealment, and compliance were used by the victims to handle everyday problems whereas seeking assistance, distancing, retaliation, victimization, self-harm and drug abuse were used in more threatening situations, which is in line with the studies by Lazarus (1999).

Results further indicate that students employed both problem-focused and emotion focused strategies, but problem-focused strategies were more commonly used to address bullying, but with limited success. This finding demands additional research in future to determine why individuals felt that they were unsuccessful while using problem-focused to solve problems related to bullying, to meet better results in future.

Furthermore, the results show that many students discussed seeking assistance from others, as both an emotion-focused and problem-focused perspective, as they looked for a friend, a classmate or a relative to seek emotional support when they were undergoing stress and pain from a bullying situation which is similar to studies conducted by Folkman and Lazarus (1986).Whereas some students in the results, also described using this coping method to seek help from others, so that they could intervene and play a role to get them rid of the bully. Kochenderfer-Ladd and Skinner showed similar results in 2002. Moreover, the results of this study suggest that children’s coping is a complex phenomenon that may need to be examined, that accounts a simultaneous use of multiple strategies by analysing how

different strategies are used together and the effectiveness of various combinations of coping strategies. In addition, the results of this study further demonstrate that ‘distancing’ has been used to avoid interaction with the bully. Many victims believed to be distant from the bully, which was an effective way of escaping any bullying situation. At the same time, it was an effective strategy to overcome stress, anxiety, and fear by keeping oneself out of sight of the bullies.

bullying situations.Similarly,self-control, concealment and ignoring the bully were more frequently practiced strategies as shown by the results of this preview, especially, when the bullying took place in a classroom or in the presence of a teacher or a staff member. This suggests that school staff does not assist the victim, in fact, it acts as a support for the bully, who is encouraged by the attitude of the staff, and hence, repeats the bullying behavior. However, some more harmful coping strategies such as self-blame, victimization, self-harm and drug addiction are very infrequently employed by participants in these studies, which shows a use of less harmful coping methods in the last ten years.

Many victims in this study reported that emotion-focused coping was often ineffective in solving problems related to bullying, which was a consistent finding with the studies conducted by Ben-Zur (2005). Additionally, according to the victims in the results of this study, the coping strategies were unsuccessful when they showed intense emotions such as crying or expressing anger verbally in the presence of the bully, probably because it made the bully feel more powerful than before. This understanding demonstrated an awareness of a bully’s motives and recognition of why certain emotional responses were unlikely to be effective. Despite this understanding, victims may have trouble controlling their emotions during a bullying situation. Some students discussed emotion-focused coping through the use of stress reducing exercises or relaxation strategies that involved calming down during a bullying incident or diverting one’s mind at home after a tough day at school. Both boys and girls generally reported these strategies to be helpful in reducing stress and regulating their emotions.

The findings of this study also indicate that the most frequently used coping strategies were retaliation, seeking social help and distancing. Victims of traditional bullying have also been noted as often reluctant to seek support by informing adults. One apparent reason for this can be due to the fear of getting reprimanded by school authorities, parents or being more bullied in future, by annoying the bullies which has also been observed by Naylor et al in 2001. This may be a sign of the changing trends in the bullying world. It might be of interest to educationists or professionals who plan interventions for such cases to know who the victim confides in and determining who they find most helpful to resolve a bullying situation as many of the participants reported that they felt comfortable with their parents and peers more than the school authorities. Another interesting finding of this research is the fact that many students across different cultures reported carefree and non-helpful attitude of the school authorities, which included school staff, counsellors and even school heads in some cases. Participants stated that even after reporting about the bully and the incident several

times no action was taken by the school and the complaint was often curbed, and this can be one of the significant reasons of increase in school bullying cases and also draws our attention to the weak policy making and implementation of rules in schools. This is an indication of the existing gap between the empirically based bullying interventions and what is delivered in schools (Patton et.al ,2017).

Finally, this study clearly shows that all types of harassment and bullying victimization occur across both supervised and unsupervised places within the school

premises. Although strict surveillance is an obvious and common measure that many schools take in this regard, but schools should also introduce and improve more planning and

intervention in this regard. Where school personnel is required to be more vigilant especially around children who are vulnerable to peer abuse, student volunteers, mediators and peers can act as support for assistance.

5.2 Methodological issues

This review could have been more extensive by increasing the number of databases used for the research. Another methodological issue with this review is the need for peer review to avoid the researcher bias especially during the analysis of the qualitative data. Peer review would have been required during several steps of this systematic literature review. After finalising the search terms and performing database search, a single reviewer applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to the found studies. Some inclusion and exclusion criteria such as year and language of publication or setting of the intervention were easy to assess and the decision making based on these criteria was simple. Other inclusion and exclusion criteria, especially criteria related to the quality of the study, were more complex.

Most of the studies included in this review did not discuss the ethical

considerations for the conducted studies other than obtaining consent for the interviews from the participants, school authorities and parents, no formal consent or approval has been obtained for any authoritative institutes to carry out the research. Additionally, the relationship of the researcher with research has not been disclosed in any of the studies undertaken for the review, which leaves a question mark on what interests the researcher could gain from the research.

The definitions for the term ‘bullying’ or any explanation of this term have not been included in any of the studies, therefore, it gives no knowledge about how the students were explained and questioned about the bullying experiences. This fact leaves the victims’

understand how researchers investigated the matter, what kind of questions elicited the given responses, as bullying definitions may vary from person to person and from one culture to another. Moreover, determining the circumstances, timings, behaviours, and causes are essential aspects of bullying that can only be interpreted by the victim. Victims

‘understanding and interpretation of the term ‘bullying’ can reveal necessary information about their choices and preferences for the use of specific coping strategies. Age and gender differences can give more in-depth insights into how they view bullying. Victims’ agreement or disagreement with the researchers’ definitions can remove any ambiguities in the analysis of the data.

5.3. Limitations

One limitation of this study is the degree to which the results can be generalized because of the qualitative methodology. In particular, the very small-sized samples studied in these researches do not allow the findings to be applied to the population at large. These studies only cover high -income countries therefore, no lower or middle-income countries have been included which also makes it difficult to generalize the data. Extensive research has been conducted on bullying and victimisation in Western and Eastern high-income countries, far less research has been done in low and middle -income countries (Zych, Ortega, & Del Rey, 2015).

Besides, the studies do not give access to the actual interviews used for gathering data, which makes it difficult to analyze the responses of the participants, contextually. Moreover, these studies do not reveal the background information such as ethnicity or family background of the participants which could have given a different context for the bullying situations.

6. Conclusion

The present study investigates into the coping strategies employed by victims of bullying in schools, to end the situation or to manage stress. Observations provide essential insights into these coping mechanisms. These strategies vary depending on different bullying situations. Future qualitative studies in this area will allow elucidating these mechanisms in the setting of perspectives of the victims about bullying and details of the bullying experiences. This will not only provide a strong foundation for the research and interventions but will also ensure positive social and academic outcomes for students.

References

Aveyard, H. (2014). Doing a literature review in health and social care: A practical guide. Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews. Review of General Psychology, 3, 311-320.

Bauman, S., & Del Rio, A. (2006). Preservice teachers’ responses to bullying scenarios: Comparing physical, verbal, and relational bullying. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 219– 231.

Beale, A. V., & Scott, P. C. (2001). ‘Bullybusters’: Using drama to empower students to stake a stand against bullying behavior. Professional School Counseling, 4, 300–305.

Becker, H. S. (1996). The epistemology of qualitative research. Ethnography and human

development: Context and meaning in social inquiry, 27, 53-71.

*Beilmann, M. (2017). Dropping out because of the others: bullying among the students of Estonian vocational schools. British journal of sociology of education, 38(8), 1139-1151

Ben-Zur, H. (2005). Coping, distress, and life events in a community sample. International

Journal of Stress Management, 12(2), 188.

Besag, V. E. (2002). Bullies and victims in schools: A guide to understanding and

management. Bristol, PA: Open University Press

CASP UK. (2018). CASP Checklists. Retrieved January 8, 2020, from CASP website: https://caspuk.net/casp-tools-checklists

*Chang, Y. T., Hayter, M., & Lin, M. L. (2010). Experiences of sexual harassment among elementary school students in Taiwan: Implications for school nurses. The Journal of

School Nursing, 26(2), 147-155.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP Qualitative Research Checklist [Online]. Retrieved February 14, 2020 from http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists

Craig, W. M., Konarski, R., & DeV, R. (1998). Bullying and victimization among Canadian

school children. Human Resources Development Canada, Applied Research Branch.

Cramer, P. (2000). Defense mechanisms in psychology today: Further processes for adaptation. American Psychologist,55, 637–64

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social‐ psychological adjustment. Child development, 66(3), 710-722.

Dewey, A. & Drahota, A. (2016) Introduction to systematic reviews: online learning

module Cochrane Training https://training.cochrane.org/interactivelearning/module-1-introduction-conducting-systematic-reviews

*Didaskalou, E., Skrzypiec, G., Andreou, E., & Slee, P. (2017). Taking action against

victimisation: Australian middle school students’ experiences. Journal of psychologists

and counsellors in schools, 27(1), 105-122.

Drake, J. (2003). Teacher preparation and practices regarding school bullying. Journal of School Health, 347-356.Retrieved on September 18, 2006 from http://.tcnj.edu/- miller8/Bullying.htm.

Duy, B. (2013). Teacher’s attitudes towards different types of Bullying and Victimization in Turkey Psychology in the Schools, 50(10), 987-1002.

Elliot, D. S., Hamburg, B. A., & Williams, K. R.(1998). Violence in American schools: A new

perspective.

*Evans, C. B., Cotter, K. L., & Smokowski, P. R. (2017). Giving victims of bullying a voice: a qualitative study of post bullying reactions and coping strategies. Child and

adolescent social work journal, 34(6), 543-555.

Fitzgerald, D. (1999). Bullying in our schools. Understanding and tackling the problem: A guide for schools. Dublin, Ireland: Blackhall Publishing

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping (pp. 150-153). New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Gruen, R. J., & DeLongis, A. (1986). Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. Journal of personality and social

psychology, 50(3), 571.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of

personality and social psychology, 54(3), 466.

Frydenberg, E., & Lewis, R. (1991). Adolescent coping: The different ways in which boys and girls cope. Journal of adolescence, 14(2), 119-133

Gottlieb, B. H. (1997). Conceptual and measurement issues in the study of coping with chronic stress. In B. H. Gottlieb (Ed.). Coping with chronic stress. New York: Plenum Press

Hawker, D. S. J., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta‐analytic review of cross‐sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41, 441– 455.

Hazler, R. J. (1996). Breaking the cycle of violence: Interventions for bullying and

victimization. Taylor & Francis.

Hazler, R. J., & Carney, J. V. (2000). When victims turn aggressors: Factors in the development of deadly school violence. Professional School Counseling, 4(2), 105.

Hunter SC, Mora-Merchan J, Ortega R. 2004. The long-term effects of coping strategy use in victims of bullying. Spanish J Psychol 7: 3–12.

Kempf, J. (2011). Recognizing and Managing Stress Coping Strategies for

Adolescents (Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin--Stout).

Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., & Skinner, K. (2002). Children’s coping strategies: Moderators of the effects of peer victimization? Developmental Psychology, 38, 267–278

Kral, M. J. (2007). Psychology and anthropology: Intersubjectivity and epistemology in an interpretive cultural science. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical

Psychology, 27(2-1), 257.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company.

Lazarus, R. S. (1999). Stress and emotion. A new synthesis. New York: Springer

Lazarus, R. S. (2006). Emotions and interpersonal relationships: Toward a person-centered conceptualization of emotions and coping. Journal of Personality, 74, 9–4

LeCompte, M. D., Schensul, J. J., Nastasi, B. K., & Borgatti, S. P. (1999). Enhanced

ethnographic methods: Audiovisual techniques, focused group interviews, and elicitation. Rowman Altamira.

Luhrmann, T. M. (2006). Subjectivity. Anthropological Theory, 6(3), 345-361

*Mackay, G. J., Carey, T. A., & Stevens, B. (2011). The Insider's Experience of Long-Term Peer Victimisation. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 21(2), 154-174.

Meyer-Adams, N., & Conner, B. T. (2008). School violence: Bullying behaviors and the psychosocial school environment in middle schools. Children and Schools, 30, 211– 221.

Monat, A., & Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Introduction: stress and coping—some current issues and controversies. In A. Monat, & R. S. Lazarus (Eds.). Stress and coping: An anthology (pp. 1–15). New York: Columbia University Press.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with

Naylor P, Cowie H, del Rey R. 2001. Reported reactions to being bullied of a sample of UK secondary school girls and boys. Child Psychol Psychiatry Rev 6:114–1

O'Connel,P., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (1999). Peer involvement in bullying: Insight and challenges for invention. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 437-452.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying in schools: facts and interventions. Research Center for Health

Promotion, University of Bergen, Norway, 2 .

Olweus, D. (1994). Annotation: Bullying at school: Basic facts and effects of a school-based intervention program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35, 1171–1190 Olweus, D. (1996). ‘Bully/victim problems at school: facts and effective intervention’,

Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Problems, 5, 15–22

Orpinas, P., & Horne, A. M. (2006). Bullying prevention: Creating a positive school climate

and developing social competence. Washington DC: American Psychological

Association.

Ortner, S. B. (2005). Subjectivity and cultural critique. Anthropological Theory, 5(1), 31-52. Parker, J. G., & Asher, S. R. (1987). Peer relations and later personal adjustment: Are

low-accepted children at risk?. Psychological bulletin, 102(3), 357.

Rapp-Paglicci, L., Dulmus, C. N., Sowers, K. M., & Theriot, M. T. (2004). “Hotspots” for bullying: exploring the role of environment in school violence. Journal of

Evidence-Based Social Work, 1(2-3), 131-141.

Rigby, K., & Slee, P. (1999). Suicidal ideation among adolescent school children,

involvement in bully—victim problems, and perceived social support. Suicide and Life‐

Threatening Behavior, 29(2), 119-130.

Rivers, I., & Smith, P. K. (1994). Types of bullying behaviour and their correlates. Aggressive

behavior, 20(5), 359-368.

Roth, S., & Cohen, L. J. (1986). Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American

psychologist, 41(7), 813.

Sackett D, Richardson W, Rosenberg W, Haynes R. Evidencebased medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997

Salmivalli C, Karhunen J, Lagerspetz KMJ. 1996. How do the victims respond to bullying? Aggr Behav 22:99–109.

Sapouna, M. (2008). Bullying in Greek primary and secondary schools. School Psychology

Seaton, E. K., Neblett, E. W., Cole, D. J., & Prinstein, M. J. (2013). Perceived discrimination and peer victimization among African American and Latino youth. Journal of Youth

and Adolescence, 42(3), 342-350.

Shweder, R. A. (1996). Quanta and qualia: What is the “object” of ethnographic

method. Ethnography and human development: Context and meaning in social inquiry, 175-182

Siann, G., Callaghan, M., Glissov, P., Lockhart, R., & Rawson, L. (1994). Who gets bullied? The effect of school, gender and ethnic group. Educational research, 36(2), 123-134. Skinner, E. A., Edge, K., Altman, J., & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of

coping: a review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129 (2), 216.

Smith PK, Shu S, Madsen K. 2001. Characteristics of victims of school bullying:

developmental changes in coping strategies and skills. In: Juvonen J, Graham S (eds):

‘‘Peer Harassment in School,’’ New York: Guilford, pp 332–351

Smith PK, Talamelli L, Cowie H, Naylor P, Chauhan P. 2004. Profiles of non-victims, escaped victims, continuing victims and new victims of school bullying. Br J Educ

Psychol 74:565–581.

Smokowski, P. R., & Kopasz, K. H. (2005). Bullying in school: An overview of types of family characteristics, and intervention strategies. Children & Schools, 27, 101–110

Stillion, J. M. (1994). Suicide: Understanding those considering premature exits. Death,

dying, and bereavement: Theoretical perspectives and other ways of knowing, 273-298.

*Sung, Y. H., Chen, L. M., Yen, C. F., & Valcke, M. (2018). Double trouble: The developmental process of school bully-victims. Children and Youth Services

Review, 91, 279-288.

*Tenenbaum, L. S., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., & Parris, L. (2011). Coping strategies and perceived effectiveness in fourth through eighth grade victims of bullying. School

Psychology International, 32(3), 263-287.

Vaillancourt, T., Brittain, H., Bennett, L., Arnocky, S., McDougall, P., Hymel, S., ... & Cunningham, L. (2010). Places to avoid: Population-based study of student reports of unsafe and high bullying areas at school. Canadian Journal of School

Psychology, 25(1), 40-54.

Vitaliano, P. P., Russo, J., Carr, J. E., Maiuro, R. D., & Becker, J. (1985). The ways of coping checklist: Revision and psychometric properties. Multivariate behavioral

Von Marées, N., & Petermann, F. (2010). Bullying in German primary schools: Gender differences, age trends and influence of parents’ migration and educational backgrounds. School Psychology International, 31(2), 178-198.

Whitney I, Smith PK. 1993. A survey of the nature and extent of bully/victim problems in junior/middle and secondary schools. Education Research 35:3–25.

Zych, I., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Del Rey, R. (2015). Systematic review of theoretical studies on bullying and cyberbullying: Facts, knowledge, prevention, and intervention. Aggression

Appendix A: Extraction Protocol for the Full-text screening

General Characteristics Name of the article

Authors Year Title Journal Country Background Information study purpose research questions Theoretical backgrounder Purpose of the study Research question

Methodology Study design

Number of participants

Gender and age of participants

Recruitment of participants where and how Types of school

Description of bullying Type of bullying

Bullying definition Bullying situation Coping strategies

Results /Outcomes Data analysis

Findings

Discussion Limitations

Practical implications

Quality Assessment Items on Quality Assessment Tool CASP

Appendix B An overview of quality assessment of the studies IN Aim Appropriate qualitative approach used Appropriate research design used Ways of data collection Recruitment of participants appropriate Relationship of the researcher defined Rigorous data analysis

Ethics addressed Clear findings Value of research

1 Yes, yes yes 30 mins Interviews with structed and semi-structed questions were

used purposeful sample, the school selected participants who were chronic victims of bullying.

No yes, there was an in-depth analysis, and

the steps were defined well

Only the interviews were approved

yes yes, it has been discussed how it contributes and ads on to the existing studies

2 Yes Yes Yes Observations, interviews and records

Purposeful sample of voluntary participants of

victims.

No Not enough details on the analysis, but detailed results

Ethics for participant were addressed properly

Yes No

3 Yes Yes Yes Audio-taped structured and semi/structured interviews A convenience sample of victims was used

No To some extent with defining some steps of the procedure

Can be useful for Australian government /school

administration and counsellors all over the

world 4 Yes Yes Yes Audio-taped structured

and semi_strucutred interviews A purposeful sample of bully- victims was used

No yes, the procedure for analysing data has been explained

in detail.

Yes, for some matters

Yes Yes, good for people addressing bullying issues.