This is the published version of a paper published in .

Citation for the original published paper (version of record):

Akkaoui, S., Johansson, A., Yagoubi, M., Haubek, D., El Hamidi, A. et al. (2020)

Chemical Composition, Antimicrobial activity, in Vitro Cytotoxicity and Leukotoxin

Neutralization of Essential Oil from Origanum vulgare against Aggregatibacter

actinomycetemcomitans.

Pathogens, 9(3): 192

https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9030192

Access to the published version may require subscription.

N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper.

Permanent link to this version:

Pathogens 2020, 9, 192; doi:10.3390/pathogens9030192 www.mdpi.com/journal/pathogens Article

Chemical Composition, Antimicrobial activity,

in Vitro Cytotoxicity and Leukotoxin Neutralization

of Essential Oil from Origanum vulgare against

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans

Sanae Akkaoui 1, Anders Johansson 2, Maâmar Yagoubi 3, Dorte Haubek 4, Adnane El hamidi 5,

Sana Rida 6, Rolf Claesson 7 and OumKeltoum Ennibi 8,*

1 Research laboratory in oral biology and biotechnology, Faculty of dental medicine, Mohammed V University in Rabat, Rabat 10 000, Morocco; sanae.akkaoui@um5s.net.ma 2 Division of Molecular Periodontology, Department of Odontology, Umeå University, 901 87 Umeå, Sweden; anders.p.johansson@umu.se 3 Microbiology Laboratory, faculty of medicine and pharmacy, Mohammed V University in Rabat, Rabat 10 000, Morocco; m.yagoubi@um5s.net.ma 4 Section for Pediatric Dentistry, Department of Dentistry and Oral Health, AarhusUniversity, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark; dorte.haubek@dent.au.dk 5 Materials, Nanotechnologies and Environment laboratory, Faculty of Sciences, Mohammed V University in Rabat, Rabat 10 000, Morocco; adnane_el@hotmail.com 6 Department of endodontics, Research laboratory in oral biology and biotechnology, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Mohammed V University in Rabat, 10 000 Rabat, Morocco; s.rida@um5s.net.ma 7 Division of Oral Microbiology, Department of Odontology, Umeå University, 901 87 Umeå, Sweden; rolf.claesson@umu.se 8 Department of Periodontology, Research laboratory in oral biology and biotechnology, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Mohammed V University in Rabat, Rabat 10 000, Morocco; * Correspondence: o.ennibi@um5s.net.ma Received: 27 January 2020; Accepted: 3 March 2020; Published: 5 March 2020 Abstract: In this study, the essential oil of Origanum vulgare was evaluated for putative antibacterial activity against six clinical strains and five reference strains of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, in comparison with some antimicrobials. The chemical composition of the essential oil was analyzed, using chromatography (CG) and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry coupled (CG– MS). The major compounds in the oil were Carvacrol (32.36%), α‐terpineol (16.70%), p‐cymene (16.24%), and Thymol (12.05%). The antimicrobial activity was determined by an agar well diffusion test. A broth microdilution method was used to study the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC). The minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) was also determined. The cytotoxicity of the essential oil (IC50) was <125 μg/mL for THP‐1 cells, which was high in comparison with different MIC values for the A. actinomycetemcomitans strains. O. vulgare essential oil did not interfere with the neutralizing capacity of Psidium guajava against the A. actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin. In addition, it was shown that the O. vulgare EO had an antibacterial effect against A. actinomycetemcomitans on a similar level as some tested antimicrobials. In view of these findings, we suggest that O.vulgare EO may be used as an adjuvant for prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases associated to A. actinomycetemcomitans. In addition, it can be used together with the previously tested leukotoxin neutralizing Psidium guajava.

Keywords: Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans; periodontitis; Origanum vulgare; essential oil; antimicrobial activity; minimum inhibitory concentration; minimal bactericidal concentration; cytotoxicity; leukotoxin neutralization

1. Introduction

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans is a capnophilic Gram‐negative coccobacillus, widely known as one of the putative pathogens associated with periodontitis, mainly in adolescents and young adults[1]. Pathogenesis of periodontitis is very complex, including immunogenetic factors, life style, proportion, and composition of specific periodontitis associated bacterial species, including A. actinomycetemcomitans in the oral biofilm [2]. The contribution of A. actinomycetemcomitans in initiation and progression of the disease is due to various virulent factors released in periodontal tissues [3]. A total of seven serotypes (a,b,c,d,e,f, and g)[2,4] of A. actinomycetemcomitans have been isolated from periodontal lesions worldwide. Patients seem to be colonized by a single serotype for life [2]. Among virulence factors of the bacterium, the leukotoxin (LtxA) is the most studied [3,5]. It activates or kills immune cells, helping the bacterium to survive in a site of infection. A specific variant of A. actinomycetemcomitans produces more LtxA than other variants [6]. This highly leukotoxic clone, JP2, has been associated with aggressive forms of periodontitis in Morocco [7,8]. According to the 2017 World Workshop of Periodontology, aggressive periodontitis is included in the category of “periodontitis”, which is characterized based on stages and grades. Extension and distribution of periodontal lesions allow distinguishing localized, generalized, and molar‐incisor distribution forms [9].

Aggressive periodontitis treatment of is based on mechanical debridement with antimicrobials as adjuvants. This aims to allow the elimination of A. actinomycetemcomitans and other bacterial species which penetrate the periodontal epithelial tissue [10]. However, given the increasing resistance of oral bacteria to antimicrobials and the side effects caused by antiseptic agents often used in dentistry (i.e., dental staining and taste alteration) [11], the search for new natural agents as alternative therapeutic products with fewer side effects (e.g., gastric problems) and less bacterial‐ resistance development has become a necessity.

Morocco has, by its geographical diversity, great natural resources for cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants. Surveys performed in Morocco among the population in different regions have shown a frequent therapeutic use of this natural heritage in traditional medicine [12,13].

Many studies through the world have been carried out to screen medicinal and pharmacological properties of different plants and essential oils, to integrate them into the therapeutic arsenal, according to standards of quality and effectiveness [14,15].

However, the use of medicinal plants and essential oils is limited in dentistry, and their antimicrobial activities on oral bacteria are not widely studied. We have previously reported that, in Moroccan population, O.vulgare is used as a mouthwash in traditional medicine [13].

O. vulgare is a widespread aromatic plant naturally growing in different parts of the world, including Northern Africa, the Mediterranean area, the Arabian Peninsula, Central Asia, and Europe [16,17]. It belongs to Lamiaceae family, and it is known for being a rich source of EOs, which have proven to possess a large variety of biological activities because of their chemical compounds [18]. The abundance of different compounds of EOs of Origanum species may show some variations because of ecological and environmental effects, geographical location, and time of collection [19–21]. We have additionally evaluated the possibility to neutralize the LtxA by administrating a mouth rinse with LtxA neutralizing agents released from leaves of Psidium guajava [22].

The aim of the present work was to study the antibacterial activity of O. vulgare EO of Moroccan origin on A. actinomycetemcomitans. In addition, we explored its cytotoxicity and checked how it cooperates with the leukotoxin neutralizing properties.

2. Results

2.1. Chemical Composition of the Essential Oil

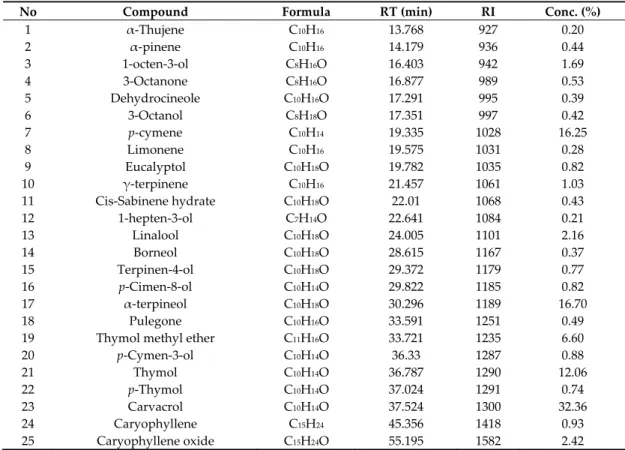

The chemical analysis of O. vulgare EO was performed by using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) technique. The 25 identified components and their relative percentage are summarized in Table 1. The major constituents were as follows: Carvacrol (32.36%), α‐terpineol

(16.70), p‐cymene (16.25%), and Thymol (12.06%) (Figure 1). Thus, the EO of O. vulgare is dominated by oxygenated monoterpenes.

Figure 1. Chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) chromatogram of O.vulgareEO.

Table 1. chemical composition of O. vulgareEO.

No Compound Formula RT (min) RI Conc. (%)

1 α‐Thujene C10H16 13.768 927 0.20 2 α‐pinene C10H16 14.179 936 0.44 3 1‐octen‐3‐ol C8H16O 16.403 942 1.69 4 3‐Octanone C8H16O 16.877 989 0.53 5 Dehydrocineole C10H16O 17.291 995 0.39 6 3‐Octanol C8H18O 17.351 997 0.42 7 p‐cymene C10H14 19.335 1028 16.25 8 Limonene C10H16 19.575 1031 0.28 9 Eucalyptol C10H18O 19.782 1035 0.82 10 γ‐terpinene C10H16 21.457 1061 1.03 11 Cis‐Sabinene hydrate C10H18O 22.01 1068 0.43 12 1‐hepten‐3‐ol C7H14O 22.641 1084 0.21 13 Linalool C10H18O 24.005 1101 2.16 14 Borneol C10H18O 28.615 1167 0.37 15 Terpinen‐4‐ol C10H18O 29.372 1179 0.77 16 p‐Cimen‐8‐ol C10H14O 29.822 1185 0.82 17 α‐terpineol C10H18O 30.296 1189 16.70 18 Pulegone C10H16O 33.591 1251 0.49 19 Thymol methyl ether C11H16O 33.721 1235 6.60 20 p‐Cymen‐3‐ol C10H14O 36.33 1287 0.88 21 Thymol C10H14O 36.787 1290 12.06 22 p‐Thymol C10H14O 37.024 1291 0.74 23 Carvacrol C10H14O 37.524 1300 32.36 24 Caryophyllene C15H24 45.356 1418 0.93 25 Caryophyllene oxide C15H24O 55.195 1582 2.42 RT: retention time; RI: retention index; Conc.: Concentration 2.2. Antimicrobial Activity

The inhibition zones obtained respectively when the O. vulgare EO, Amoxicillin (AM), Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (AMC), and Doxycycline (DO) were tested against six clinical strains and five reference strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans are shown in Table 2. All tested strains showed inhibition zones in the presence of the EO (27.6 μg) (37–69 mm). The susceptibility to the antimicrobials varied among the strains (Table 2).

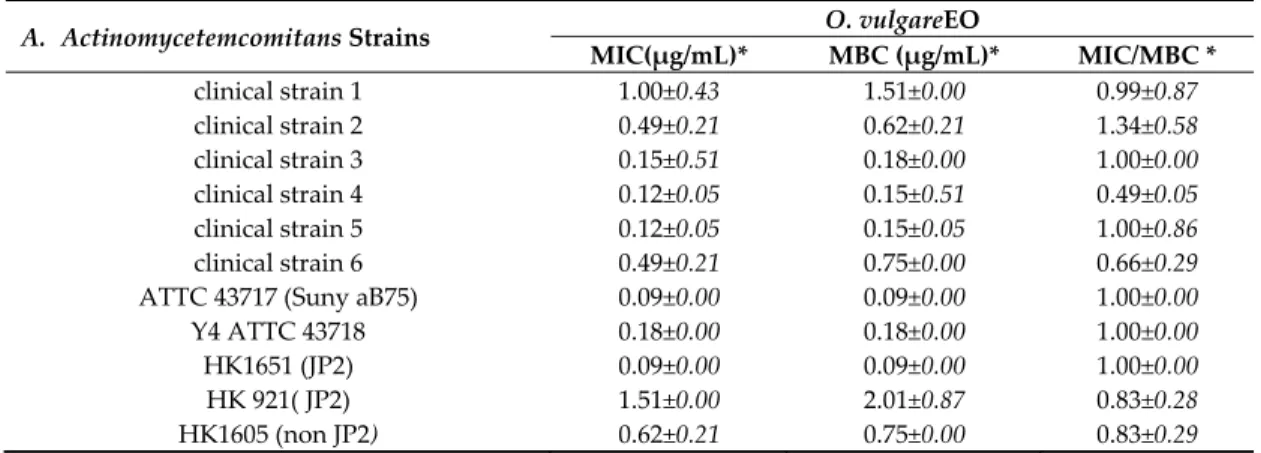

The serial diffusion test in 96‐well microplates showed MIC values in the ranges of 0.05 to 1.51 μg/mL and 0.09 to 2.01 μg/mL for MBCs (Table3). For MBC/MIC ratio, all the values found were lower than 4, considering EO as bactericidal agents.

Table 2. Mean diameter of inhibition zones (mm) obtained by the agar diffusion method and the interpretation according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters Version 9.0, valid from 2019‐01‐01. A. a. strains Inhibition Zone Diameter (mm)1* p‐value EO Antimicrobials O. vulgare 27.6 μg

AMC2 AML3 DO4 SP5 CIP6 MH7 VA8 MTZ9

25 μg 25 μg 30μg 100μg 5μg 30 μg 30 μg 5 μg Breakpoints S >15 R <15 note 10 note11 no info S >30 R <30 S>24 R <21 no info no info clinical strain 1 37.33 ± 2.08 31.66 ± 1.15 30.33 ± 0.57 25.00 ± 0.00 ** 29.66 ± 0.57 28.33 ± 0.57 36.00 ± 1.73 0.00 0.00 <0.001 S S S S ‐‐ R S ‐‐ R clinical strain 2 51.33 ± 0.57 ** 32.66 ± 0.57** 29.33 ± 1.15** 23.33 ± 0.57 22.66 ± 0.57 26.66 ± 0.57** 36.33 ± 0.57** 14.33 ± 0.57** 0.00 <0.001 S S S S ‐‐ R S ‐‐ R clinical strain 3 65.66 ± 0.57 ** 30.66 ± 0.57 30.66 ± 1.15 25.66 ± 0.57 28.66 ± 1.15 29.33 ± 1.15 38.33 ± 2.08** 15.66 ± 0.57** 0.00 <0.001 S S S S ‐‐ R S ‐‐ R clinical strain 4 63.66 ± 0.57 ** 32.00 ± 1.00 28.66 ± 1.15 27.66 ± 0.57 27.66 ± 1.15 33.00 ± 1.00 39.33 ± 0.57** 15.00 ± 0.00** 0.00 <0,001 S S S S ‐‐ S S ‐‐ R clinical strain 5 65.33 ± 0.57 ** 31.00 ± 1.73 27.33 ± 0.57** 23.33 ± 0.57** 28.33 ± 0.57 31.66 ± 0.57 38.00 ± 1.73** 14.66 ± 0.57** 0.00 <0.001 S S S S ‐‐ S S ‐‐ R clinical strain 6 56.33 ± 1.52 ** 31.00 ± 0.00 27.66 ± 0.57 22.66 ± 0.57** 27.00 ± 1.00 31.66 ± 0.57 34.66 ± 0.57** 15.33 ± 0.57** 0.00 <0.001 S S S S ‐‐ S S ‐‐ R ATCC 43717 (Suny aB75) 69.66 ± 0.57** S 40.33 ± 0.57** S 25.66 ± 0.57 S 28.33 ± 0.57 S 29.33 ± 0.57 ‐‐ 30.66 ± 0.57 S 33.66 ± 0.57** S 24.66 ± 0.57 ‐‐ 0.00 R <0.001 ATTC 43718 Y4 65.33 ± 0.57** S 25.33 ± 0.57 S 34.33 ± 0.57 S 28.66 ± 0.57 S 28.66 ± 1.15** ‐‐ 31.00 ± 1.00** S 33.33 ± 0.57 S 24.33 ± 0.57 ‐‐ 0.00 R <0.001 HK1651 (JP2) 67.66 ± 1.52** S 28.33 ± 0.57 S 27.66 ± 0.57 S 28.33 ± 0.57 S 27.33 ± 0.57 ‐‐ 34.33 ± 0.57 S 32.00 ± 1.73 S 23.66 ± 0.57** ‐‐ 0.00 R <0.001 HK 921(JP2) 37.00 ± 1.73 S 29.66 ± 0.57 S 27.66 ± 0.57 S 29.00 ± 0.00 S 25.66 ± 0.57 ‐‐ 34.66 ± 0.57 S 29.33 ± 1.15 S 20.33 ± 0.57** ‐‐ 0.00 R <0.001 HK1605 (non JP2) 46.00 ± 1.00** S 29.33 ± 0.57 S 22.66 ± 0.57** S 26.66 ± 1.15** S 29.33 ± 1.15 ‐‐ 29.33 ± 1.15** R 32.00 ± 1.00** S 19.66 ± 0.57** ‐‐ 0.00 R <0.001 Calculation of Inhibition Zone Diameter includes the diameter of the well (6mm). *Mean ± Standard deviation; R: resistant;S: susceptible; EO: essential oil. ** p< 0.01: the inhibition zone diameter of a group (EO or antimicrobials) vs. the inhibition diameters of all other groups for each strain. 1 Diameter of inhibition zones, including diameter of well 6 mm, 2Amoxicillin + Clavulanic Ac,3 Amoxicillin, 4 Doxycycline; 5Spiramycine; 6Ciprofloxacine; 7Minocycline; 8Vancomycin; 9Metronidazol.10Breakpoint is missing for Amoxicillin; however, susceptibility can be interred from ampicillin, for which the breakpoint is: S > 16 and R< 16 mm.11

breakpoint is missing for Doxycycline; however, isolates susceptible to tetracycline are also susceptible to Doxycycline. Breakpoint for tetracycline is: S ≥ 25 and R< 22.

Table 3. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC) of O. vulgare EO for the selected A. actinomycetemcomitans strains. A. Actinomycetemcomitans Strains O. vulgareEO MIC(μg/mL)* MBC (μg/mL)* MIC/MBC * clinical strain 1 1.00±0.43 1.51±0.00 0.99±0.87 clinical strain 2 0.49±0.21 0.62±0.21 1.34±0.58 clinical strain 3 0.15±0.51 0.18±0.00 1.00±0.00 clinical strain 4 0.12±0.05 0.15±0.51 0.49±0.05 clinical strain 5 0.12±0.05 0.15±0.05 1.00±0.86 clinical strain 6 0.49±0.21 0.75±0.00 0.66±0.29 ATTC 43717 (Suny aB75) 0.09±0.00 0.09±0.00 1.00±0.00 Y4 ATTC 43718 0.18±0.00 0.18±0.00 1.00±0.00 HK1651 (JP2) 0.09±0.00 0.09±0.00 1.00±0.00 HK 921( JP2) 1.51±0.00 2.01±0.87 0.83±0.28 HK1605 (non JP2) 0.62±0.21 0.75±0.00 0.83±0.29 *Mean± standard deviation. 2.3. Cytotoxicity The O. vulgareEO showed a dose‐dependent cytotoxic effect in cultures of PMA‐differentiated THP‐1 cells (Figure 2). Concentrations of oil above 125 μg/mL causedsubstantial decreased cell viability after 24 h of exposure.

Figure 2. Cytotoxicity of O.vulgare essential oil.

PMA‐differentiated THP‐1 cells were exposed to different concentrations of oil for 24 h and cell viability determined with neutral red uptake staining. Mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments are shown.

2.4. A. actinomycetemcomitans Leukotoxin Neutralization

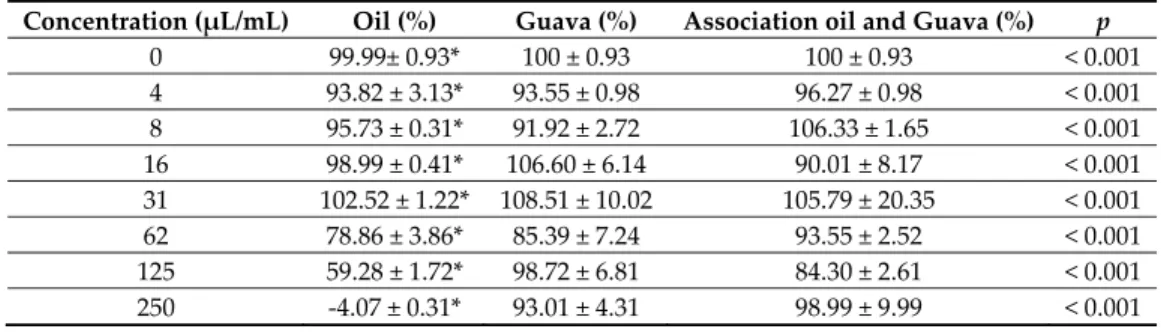

The O. vulgare EO showed no neutralizing effect on A. actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxicity estimated in cultures of PMA‐differentiated THP‐1 cells (Table 4). The presence of oil from O. vulgare did not affect the inhibitory effect on leukotoxicity exhibited by the extract from the Psidium guajava leaves.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

0

16

31

62

125

250

500

1000

TH

P-1

Ce

lls viabi

lity

(

%

)

Table 4. Leukotoxicity (200 ng/mL) in presence of Psidium guajava or O. vulgare EO alone or in

combination after 2 h incubation in cultures of PMA‐differentiated THP‐cells. Result is expressed as percent viable cells in relation to control cells (100%) based on quantitative neutral red uptake analyses. Mean ± SD of triplicate analyses.

Concentration (μL/mL) Oil (%) Guava (%) Association oil and Guava (%) p

0 99.99± 0.93* 100 ± 0.93 100 ± 0.93 < 0.001 4 93.82 ± 3.13* 93.55 ± 0.98 96.27 ± 0.98 < 0.001 8 95.73 ± 0.31* 91.92 ± 2.72 106.33 ± 1.65 < 0.001 16 98.99 ± 0.41* 106.60 ± 6.14 90.01 ± 8.17 < 0.001 31 102.52 ± 1.22* 108.51 ± 10.02 105.79 ± 20.35 < 0.001 62 78.86 ± 3.86* 85.39 ± 7.24 93.55 ± 2.52 < 0.001 125 59.28 ± 1.72* 98.72 ± 6.81 84.30 ± 2.61 < 0.001 250 ‐4.07 ± 0.31* 93.01 ± 4.31 98.99 ± 9.99 < 0.001 *Significant difference (p < 0.001). 3. Discussion The use of natural products, such as Eos, as antibacterial agents is expanding in oral hygiene and dentistry. In Morocco, a major herbal‐producing nation, many studies have been carried out on the antimicrobial activity of Moroccan plant extracts and EOs [23,24]. However, there are few reports on the effects of Moroccan EOs on periodontal pathogens. The EO of O. vulgare was selected for this study on the basis of its traditional use for the treatment of oral diseases [13]. The results of the present study showed that the essential oil of O. vulgare exhibited a strong antimicrobial activity against all tested clinical and reference strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans. The antimicrobial activity of an EO is well‐known, and it is linked to its main constituents. The O. vulgare EOs is characterized by the dominance of various antibacterial compounds. Chemical analyses of this oil revealed that the main constituents of the oil were carvacrol 32.36%, α‐terpineol 16.70%, p‐cymene 16.24%, and thymol 12.05% (Figure 1 and Table 1). All these compounds have strong antibacterial activity, as shown in previous studies[25–27]. Linalool (an alcohol) is one of the components of the essential oil of O. vulgare present in lower concentration (Table 1). However, this compound was found to have antimicrobial activity against various oral and non‐oral microbes [28– 30].

In this study, we used the agar diffusion test to study the antibacterial activity of O. vulgare EO against clinical and reference strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans. Substantial antibacterial activity against both JP2 and non‐JP2 strains was observed. The diameters of the inhibition zones obtained were greater than 20 mm, (going from 37.00 ± 1.73 mm for strain HK 921(JP2), to 69.66 ± 0.57 mm for strain ATCC 43717 Sunny aB75) (Table 3). The studied strains showed a high sensitivity to the studied essential oil when 27.6 μg of it was used.

For analyzing the susceptibility of the A. actinomycetemcomitans strains to the tested antimicrobials, and according to the EUCAST (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing), breakpoints for Haemophilus influenzae was used, as there is not one associated to A. actinomycetemcomitans [31].

Based on the EUCAST interpretation values, all 11 tested A. actinomycetemcomitans strains were susceptible to AMC and MH. All isolates were also susceptible to AML if ampicillin‐derived breakpoints were used. Furthermore, eight strains were susceptible to DO if tetracycline‐derived breakpoints were used. Susceptibility to SP, VA and MTZ could not be validated, since no breakpoints for H. influenzae are available in the EUCAST database. Inhibition zones are usually absent when susceptibility of A. actinomycetemcomitans to MTZ is tested under aerobic conditions.

For studying the antibacterial effect of the essential oil to the selected A. actinomycetemcomitans strains, compared with corresponding effect of the antimicrobials, the inhibition zones were used. Since all inhibition zones induced by the essential oil (27.6 μg) were significantly larger, it indicates that the oil has a substantial antibacterial effect on A. actinomycetemcomitans.

A range of different antimicrobials have been used as adjuvant for treatment of periodontitis during the last decades. This has raised questions about risk for resistance development among the antimicrobials and also doubts about the beneficial value of this treatment strategy. However, a range of clinical studies have shown that use of a combination of MTZ and AML in conjunction with standard periodontal treatment of aggressive forms of periodontitis achieves better clinical and microbiological results than treatment without these antimicrobials [32–34] .

Regarding resistance development among these antimicrobials, different results are reported. However, the breakpoint for MTZ is not available. Thus, susceptibility testing of this antimicrobial is not relevant. Based on usage of breakpoint value for Haemophilus influenzae, most reports of susceptibility of A. actinomycetemcomitans to AML show that the prevalence of resistant isolates of the bacterium is low [35]. In addition, when isolates earlier found to be resistant to this antimicrobial were retested, the opposite result was achieved [36].

For the microdilution test, the results obtained for MIC are mainly in accordance with the diameters of the inhibition zones observed in the well diffusion test. On the other hand, the O. vulgare EO showed bactericidal activity with promising MBC results and an MBC/MIC ratio below 4. The MBC values were similar or almost identical to those of MIC. O. vulgare EO had the highest inhibitory activity against ATTC 43717 (Suny aB75) (CMI = 0.09 μg/mL) and the highest bactericidal effect against the reference strains ATTC 43717 (Suny aB75) and HK1651 (JP2) (CMB= 0.09 μg/mL) (Table 3). These results are consistent with those obtained in previous work on other tested non‐oral Gram‐ negative bacteria [37–39] reflecting a higher antibacterial activity on this oral bacterium.

The cytotoxicity of the essential oil of O. vulgare EO in concentrations was below 125 μg/mL when analyzed in cultures of human macrophages (THP‐1 cells). The IC50‐value for the oil was much lower than the MIC‐values for antibacterial effect, suggesting an advantage for its use as a clinical chemical agent. EO seems to be toxic for cells. Previously, it has been shown that carvacrol and other oregano constituents can be cytotoxic at high doses [40,41]. Thus, further investigations are needed to achieve maximum positive antimicrobial effect of O.vulgare EO without cytotoxic effects. In addition, this oil did not interfere with the LtxA neutralizing capacity of extract from Psidium guajava leaves. It has been shown that components extracted from Psidium guajava bind to LtxA and completely abolish its activity [42].

A mouth rinse containing water extract from Psidium guava leaves has been tested on adolescents in Morocco with the presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans from the JP2 genotype in their subgingival plaque [22]. Results from this pilot study are limited, but they indicate that LtxA neutralization alone was not sufficient for eradication of A. actinomycetemcomitans and its pro‐inflammatory effect.

A. actinomycetemcomitans is a germ that is mostly associated with aggressive forms of periodontitis. One of its virulence factors is LtxA, which plays an important role in pathogenicity. Periodontal infections due to strains that produce high levels of LtxA are strongly associated with a serious disease. LtxA selectively kills human leukocytes and can affect the bodyʹs functioning local defensive mechanisms [5]. Previous studies on the role of LtxA in host–parasite interactions have focused mainly on polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) [43,44]. In periodontal inflammation, macrophages have an important role in regulating inflammatory reactions and tissue degradation and remodeling [45]. LtxA causes a rapid inflammatory cell death in macrophages, which might cause an imbalance in the pro‐inflammatory response [46].

We can conclude that the O. vulgare EO has the potential to be used as a preventive or therapeutic agent against periodontitis in individuals colonized with A. actinomycetemcomitans. Its cytotoxic properties can be overcome by the possibility to cooperate with the LtxA neutralizing compounds of Psidium guajava.

4. Materials and Methods

The present study was carried out after obtaining approval from the Biomedical Ethics Committee (Ref. 400/2010); the individual patientʹs written informed consent was obtained before the collection of the plaque samples for the study.

4.1. Plant Material and Extraction of Essential Oil The aerial part of O. vulgare was purchased at a local market in Rabat, Morocco. A portion (100 g) of the aerial parts of the plants was hydrodistilled during 3 hours, using a Clevenger system. The obtained essential oil was dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate and, after filtration, stored at +4 °C, until it was tested and analyzed. 4.2. Gas Chromatography Coupled with Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) The chemical composition of the EO was analyzed by using a gas chromatograph (Perkin Elmer ClarusTM GC‐680) fitted to a mass spectrometer (Q‐8 MS Ion Trap), operating in electron‐impact EI (70 eV) mode. Non‐polar column HP‐5MS (Methylpolysiloxane 5% phenyl, 60 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm thickness) was used (the GC/MS was done atthe Platform of physicalchemistry analysis and characterization, Faculty of Sciences, Mohammed V University in Rabat, Morocco). The chromatographic conditions were as follows: injector temperatures at 280 °C; carrier gas, helium at flow rate of 1 mL/min; temperature program ramp from 60 to 200 °C, at gradient of 2 °C/min. After holding 1 min at 200 °C, another ramp was operated from 200 until 300 °C, at 20 °C/min, and final hold for 5 min. The GC/MS system was controlled by TurbomassTMsoftware; a library search was carried out, using the combination of NIST MS Search and literature. The NIST version was 2.0 g, built May 19, 2011. The relative number of individual components of the total oil was expressed as a percentage of each peak area relative to total peak areas. The retention indices (RI) were obtained by injecting in HP‐5MS a mixture of continuous series of straight chain hydrocarbons (C8‐C31), under the same conditions as described above. 4.3. A. actinomycetemcomitans Strains The antimicrobial capacity of O.vulgare EO and of following selected antimicrobials, Amoxicillin (AM), Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (AMC), Doxycycline (DO), Ciprofloxacin (CIP), Minocycline (MN), Vancomycin (VA), and Metronidazole(MTZ) was tested against six clinical isolates and the following reference strains: ATTC 43717 (Suny aB75), Y4 (ATCC 43718),HK1651(JP2),HK 921 (JP2), and HK1605 (non JP2). HK 1651 was obtained from Department of Odontology, Umeå University, Sweden. HK 921 (JP2) and HK1605 (non JP2) were obtained from Department of Dentistry and Oral Health Aarhus University, Denmark.

The bacterial strains and essential oil were stored at the laboratory of oral biology and biotechnology, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Mohammed V University in Rabat. The tests were performed at the same laboratory.

4.4. Subgingival Plaque Sampling

The clinical A. actinomycetemcomitans strains were obtained from subgingival plaque samples collected from patients with periodontitis. The patients were recruited at the Clinical Department of Periodontology in the Center of Consultations and Dental Treatments (CCTD) in Rabat‐Morocco.

The sampled patients were diagnosed with aggressive periodontitis and had pockets of 5 mm or greater confirmed by clinical and radiological examination. Subgingival sampling of periodontal biofilm was performed, using absorbent paper point (medium size, Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland). Then, the papers were pooled and placed in a tube containing 1.5 mL of phosphate buffer saline (PBS). All plaque samples were collected by the same examiner.

4.5. Culture and Isolation

Once in the laboratory, the sample was vortexed before being seeded into the culture medium Dentaid‐1[47]and used for selective isolation and growth of A actinomycetemcomitans. Plates were incubated at 37 °C, in air, with 5% CO2; and after 3–5 days, they were carefully examined for the presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans. Identification of the bacterium was based on colony morphology, positive catalase reaction, and negative oxidase reaction. Putative A.

actinomycetemcomitans colonies were further elucidated by microscopy, Gram stain, and enzymatic activity, including indole and fermentation of glucose, xylose, maltose, and mannitol [48]. The isolates were then stored at −80 °C in glycerol broth.

4.6. In Vitro Antimicrobial Susceptibility Assay

The antimicrobial effect of O. vulgare was tested in two ways. The agar well diffusion method was used to determine the antibacterial activity in comparison with corresponding activity of selected antimicrobials. A microdilution assay was used for the calculation of MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration). MBC (minimal bactericidal concentration) of the oil was also determined.

4.6.1. Agar Well Diffusion Method

Agar well diffusion method [49–51] was used to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of essential oil from O. vulgare.

Initially, the bacterial strains were cultivated on slant cultures for 24 hours. Subsequently, bacterial suspensions were prepared in 0.85% NaCl, and the turbidity was adjusted to McFarland 0.5 (approximately 1 × 108 CFU/mL). The turbidity was confirmed by a Sensititre® Nephelometer. At first, the agar plates were seeded by swabbingwith a cotton swab. Then, 30 μLof the essential oil (27.6 μg) was added to wells (diameter 6 mm) made in the center of each agar plate after 15 minutes [52,53]. Doxycycline (disc: 30 μg) was used as positive control [54]. The plates were incubatedat 37 °C, in an aerobic atmosphere containing 5% CO2, for 48 hours. All tests were carried out in triplicate, in separate experiments. Diameters of the inhibition zones were measured as (mm), including the diameter of the well. The antibacterial activity was considered if an inhibition halo of growth larger than 6 mm (size of the well) was produced.

4.6.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Determination

The MIC of O. vulgare EO was determined by using a broth assay in 96‐well microplates (Sigma‐ Aldrich, USA), as recommended by NCCLS, for the determination of the MIC (NCCLS, 1999). All tests were performed in Mueller Hinton broth (MHB) supplemented with Tween 80, (final concentration of 0.5% v/v), aimed to improve the solubility. The bacterial strains were cultured overnight, at 37°C, in Dentaid‐1. The turbidity of the inoculums was adjusted to McFarland 0.5. The turbidity of the suspensions was confirmed with the Sensititre® Nephelometer. Serial dilutions ranging from 48.42 to 0.09 mg/mL of the EO were prepared in a 96‐well microplate, including one growth control with “MHB + Tween 80”, one sterile control containing “MHB and Tween 80”, and another sterile control made of “MHB +Tween 80 +EO”. Amoxicillin (10 mg/mL) was used as positive control. The plates were incubated under normal atmospheric conditions, at 37 °C, for 24 hours. After incubation time, 40 μL of 2 mg/mL Triphenyl Tetrazolium Chloride (TTC) indicator solution (indicator of microorganism growth) was added to all wells of the microplate. Subsequently, the plates were re‐incubated for 2 hours, at 37 °C [55]. Bacterial growth was monitored when the TTC indicator was red.

4.6.3. Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MCB) Determination

To measure the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC), 10 μL of cultures was taken from wells of the microplate of MIC, with no visible turbidity, inoculated on blood agar plates, and incubated for 48 hours, at 37 °C, under 5% CO2 [56]. MBC was defined to be the lowest concentration of essential oil that killed 99.9% of the microorganisms in culture on the agar plate after the incubation time. The MBC/MIC ratio was calculated to show the nature of the antibacterial effect of essential oils. In a ratio less than 4, the essential oil was classified as a bactericidal essential oil, and in a ratio more than 4, it was classified as a bacteriostatic essential oil [57]. Each MIC and MBC value was obtained from three independent experiments.

4.7. Cell Culture Cells of the human acute monocytic leukemia cell line THP‐1 (ATCC 16) were cultured in RPMI‐ 1640 (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MI, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma‐Aldrich), at 37 °C, in 5% CO2. Before determination of leukotoxic activity, the THP‐1 cells were seeded in 96‐well cell‐culture plates, at a cell density of 105 cells/mL in 100 μL culture medium supplemented with 50 nMphorbol 12‐myristate 13‐acetate (PMA, Sigma‐Aldrich), and incubated for 24 hours. The PMA‐ activated THP‐1 cells exhibited adherent properties and enhanced sensitivity to the LtxA.

After differentiation with phorbol 12‐myristate 13‐acetate (PMA), THP‐1 cells acquire a macrophage phenotype, which is similar to primary human macrophages in many aspects [58,59]. This is the common way to use THP‐1 cells in cell assays. The adherent phenotype is macrophage‐ like and easier to study in cytotoxicity assays. Twenty‐four hours prior to LtxA exposure, the culture medium was discarded, and 100 μL fresh medium without PMA was added to each well of the THP‐1 monolayer. 4.8. Cytotoxicity Assay The cell monolayers of PMA‐differentiated THP‐1 cells were exposed to different concentrations of the oil for 24 h, at conditions described above. The proportion of viable cells in each well was determined by the neutral red uptake method and expressed in relation to that of the control cells cultured in plane medium [60]. Cytotoxicity (LD50) was expressed as the lowest concentration (ppm) that kills ≥ 50% of the cells. 4.9. LtxA Purification LtxA was purified from A. actinomycetemcomitans strain HK 1519, described in detail previously [61]. The purified LtxA was basically free from lipopolysaccharides (LPS) (<0.001% of total protein) and visualized by SDS‐polyacrylamide gel separation. 4.10. Preparation of Psidium Guajava Leave Extract Guava leaves were collected in Ghana by Dr. F.Kwamin and transported with a courier to Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden. Guava leaves at a concentration of 250 g/liter of water, were boiled for 10 minutes before the leaves were removed by filtration, and cleared from debris by centrifugation. The supernatant was aliquoted and stored in a refrigerator until use. The amount of dry substance was determined by evaporation of the extract, which contained 10.0 mg/mL H2O. 4.11. LxtA Neutralization Assay The cell monolayers of PMA‐differentiated THP‐1 cells were exposed to different concentrations of the oil or guava for 15 min, before the LtxA (200 ng/mL) was added. The different mixtures were incubated for 2 h, at conditions described above. The proportion of viable cells in each well was determined by the neutral red uptake method, as described above. 4.12 Statistical Analyses Statistical analysis was carried out by using SPSS for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Inhibition zone diameter, MIC, MBC, MBC/MIC, and cell viability values, as continuous variables with a normal distribution, were expressedas mean ± standard deviation. For statistical differences between the inhibition diameter of the nine antimicrobial agents (EO, AMC, AMX, DO, SP, CIP, MH, VA, and MTZ), andthe cell viability in presence of EO, Guava, and the association “EO +Guava”, the One‐Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction was performed. A p‐value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were carried out, using SPSS for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The present study indicates that O. vulgare EO may find application as an antibacterial agent on periodontitis associated with A. actinomycetemcomitans and shows the possibility of Psidium guajava to overcome its cytotoxic properties. However, further investigations on mechanisms of action and toxicity need to be continued.

Author Contributions: S.A., extraction of essential oil, culture and isolation of A. actinomycetemcomitans, in vitro

antimicrobial susceptibility assay, statistical analyses, and drafting the manuscript; A.J., cell culture, LtxA purification, cytotoxicity assay, LtxA neutralization assay, and the drafting of the manuscript; M.Y., culture and isolation of A. actinomycetemcomitans. D.H., culture and isolation of A. actinomycetemcomitans. A.EH., gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC/MS) assay; R.C., in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility assay. OK.E., recruitment of patients, subgingival plaque sampling, culture and isolation of A.

actinomycetemcomitans, drafting the manuscript, and work supervision; S.R., helped with funds. All authors have

read and agreed on the content of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received funding from CNRST (National Center for scientific and Technological

Research (PPR116/2016), Morocco.

Acknowledgments: The authors are thankful to Francis Kwamin at Ghana University for the collection of Guava

leaves.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Henderson, B.; Ward, J.M.; Ready, D. Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans: AtripleA*periodontopathogen? Periodontology 2000. 2010, 54, 78–105.

2. Asikainen, S.; Chen, C. Oral ecology and person‐to‐person transmission of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. Periodontology 2000. 1999, 20, 65–81.

3. Zambon, J.J.; Haraszthy, V.I. The laboratory diagnosis of periodontal infections. Periodontology 2000 1995,

7, 69–82.

4. Könönen, E.; Müller, H.P. Microbiology of aggressive periodontitis. Periodontology 2000. 2014, 65, 46–78. 5. Johansson,A. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin: A powerful tool with capacity to

causeim balance in the hostin flammatory response. Toxins. 2011, 3, 242–259.

6. Brogan, J.M.; Lally, E.T.; Poulsen, K.; Kilian, M.; Demuth, D.R. Regulation of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin expression: Analysis of the promoter regions of leukotoxic and minimally leukotoxic strains. Infect. Immun. 1994, 62, 501–508.

7. Haubek, D.; Ennibi, O.K.; Poulsen, K.; Væth, M.; Poulsen, S.; Kilian, M. Risk of aggressive periodontitis in adolescent carriers of the JP2 clone of Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans in Morocco: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. Lancet 2008, 371, 237–242.

8. Ennibi, O.K.; Benrachadi, L.; Bouziane, A.; Haubek, D.; Poulsen, K. The highly leukotoxic JP2 clone of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans in localized and generalized forms of aggressive periodontitis.

Acta Odontol. Scand. 2012, 70, 318–322. 9. Caton, J.G.; Armitage, G.; Berglundh, T.; Chapple, I.L.; Jepsen, S.; Kornman, K.S.; Mealey, B.L.; Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Tonetti, M.S. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri‐implant diseases and conditions–Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S1–S8. 10. Wang, C.‐Y.; Wang, H.‐C.; Li, J.‐M.; Wang, J.‐Y.; Yang, K.‐C.; Ho, Y.‐K.; Lin, P.‐Y.; Lee, L.‐N.; Yu, C.‐J.; Yang, P.‐C. Invasive infections of Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2010, 43, 491–497. 11. Walker, C.B. The acquisition of antibiotic resistance in the periodontal microflora. Periodontology 2000 1996, 10, 79–88. 12. Jouad, H.; Haloui, M.; Rhiouani, H.; ElHilaly, J.; Eddouks, M. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used for the treatment of diabetes, cardiac and renal diseases in the North centre region of Morocco (Fez– Boulemane). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 77, 175–182. 13. Akkaoui, S.; Ennibi, O.k. Use of traditional plants in management of halitosis in a Moroccan population. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 6, 267.

14. Kharbach, M.; Marmouzi, I.; ElJemli, M.; Bouklouze, A.; VanderHeyden, Y. Recent advances in untargeted and targeted approaches applied in herbal‐extracts and essential‐oils finger printing‐Areview. J. Pharm.

Biomed. Anal. 2020, 177, 112849.

15. Barnes, J. Quality, efficacy and safety of complementary medicines: Fashions, facts and the future. Part I.

Regul. Qual. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003, 55, 226–233.

16. DeMartino, L.; DeFeo, V.; Nazzaro, F. Chemical composition and in vitro antimicrobial and mutagenic activities of seven Lamiacea eessential oils. Molecules 2009, 14, 4213–4230. 17. Fikry, S.; Khalil, N.; Salama, O. Chemical profiling, biostatic and biocidal dynamics of Origanum vulgare L. essentialoil. AMB Express 2019, 9, 41. 18. Raut, J.S.;Karuppayil, S.M. A status review on the medicinal properties of essential oils. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2014, 62, 250–264. 19. Johnson, C.B.; Kazantzis, A.; Skoula, M.; Mitteregger, U.; Novak, J. Seasonal, populational and ontogenic variation in the volatile oil content and composition of individuals of Origanum vulgare subsp.Hirtum, assessed by GC headspacean alysis and by SPME sampling of individual oil glands. Phytochem. Anal. Int. J. Plant Chem. Biochem. Technol. 2004, 15, 286–292.

20. Lotti, C.; Ricciardi, L.; Rainaldi, G.; Ruta, C.; Tarraf, W.; DeMastro, G. Morphological, Biochemical, and Molecular Analysis of Origanum vulgare L. Open Agric. J. 2019, 13, 116–124. 21. Khan, M.; Khan, S.T.; Khan, M.; Mousa, A.A.; Mahmood, A.; Alkhathlan,H.Z. Chemical diversity in leaf and stem essential oils of Origanum vulgare L. and their effects on microbicidal activities. AMB Express 2019, 9, 176. 22. Ennibi, O.K.; Claesson, R.; Akkaoui, S.; Reddahi, S.; Kwamin, F.; Haubek, D.; Johansson,A. High salivary levels of JP2 genotype of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans is associated with clinical attachment lossin Moroccan adolescents. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2019, 5, 44–51. 23. Chaouki, W.; Leger, D.Y.; Eljastimi, J.; Beneytout, J.‐L.; Hmamouchi, M. Antiproliferative effect of extracts from Aristolochia baetica and Origanum compactum on human breast cancer cell lineMCF‐7. Pharm. Biol. 2010, 48, 269–274.

24. Hmamouchi, M.; Hamamouchi, J.; Zouhdi, M.; Bessiere, J. Chemical and antimicrobial properties of essential oils of five Moroccan Pinaceae. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2001, 13, 298–302.

25. CanBaser, K. Biological and pharmacological activities of carvacrol and carvacrol bearing essentialoils.

Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 3106–3119.

26. Park, S.‐N.; Lim, Y.K.; Freire, M.O.; Cho, E.; Jin, D.; Kook, J.‐K. Antimicrobial effect of linalool and α‐ terpineol against periodontopathic and cariogenic bacteria. Anaerobe 2012, 18, 369–372. 27. Bagamboula, C.; Uyttendaele, M.; Debevere, J. Inhibitory effect of thyme and basil essential oils, carvacrol, thymol, estragol, linalool and p‐cymene towards Shigella sonnei and S.flexneri. Food Microbiol. 2004, 21, 33– 42. 28. Lin, Z.‐K.; Hua, Y.; Gu, Y. The chemical constituents of the essential oil from the flowers, leaves and peels of Citrus aurantium. Act. Bot. Sin. 1986, 28, 641–645. 29. Alipour, G.; Dashti, S.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Review of pharmacological effects of Myrtus communis L. and ist active constituents. Phytother. Res. 2014, 28, 1125–1136. 30. Cha, J.‐D.; Jung, E.‐K.; Kil, B.‐S.; Lee, K.‐Y. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oil from Artemisia feddei.J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 17, 2061–2065. 31. European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and

Zone Diameters; Version 9.0; 2019. Available online: http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/Dosages_EUCAST_B reakpoint_Tables_v_9.0.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2020)

32. Winkel, E.; VanWinkelhoff, A.; Timmerman, M.; VanderVelden, U.; VanderWeijden, G. Amoxicillin plus metronidazole in the treatment of adult periodontitis patients: A double‐blind placebo‐controlled study.J.

Clin. Periodontol. 2001, 28, 296–305.

33. Zandbergen, D.; Slot, D.E.; Niederman, R.; VanderWeijden, F.A. The concomitant administration of systemic amoxicillin and metronidazole compared to scaling and root planing alone in treating periodontitis:=a systematic review=.BMC Oral Health 2016, 16, 27.

34. Keestra, J.; Grosjean, I.; Coucke, W.; Quirynen, M.; Teughels, W. Non‐surgical periodontal therapy with systemic antibiotics in patients with untreated chronic periodontitis: A systematic review and meta‐ analysis. J. Periodontal Res. 2015, 50, 294–314.

35. Mínguez, M.; Ennibi, O.; Perdiguero, P.; Lakhdar, L.; Abdellaoui, L.; Sánchez, M.; Sanz, M.; Herrera, D. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis strains from periodontitis patients in Morocco. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 1161–1170. 36. Jensen, A.B.; Haubek, D.; Claesson, R.; Johansson, A.; Nørskov‐Lauritsen, N. Comprehensive antimicrobial susceptibility testing of a large collection of clinical strains of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans does not identify resistance to amoxicillin.J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 846–854. 37. Chao, S.C.; Young, D.G.; Oberg, C.J. Screening for inhibitory activity of essential oils on selected bacteria, fungi and viruses. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2000, 12, 639–649. 38. Oussalah, M.; Caillet, S.; Saucier, L.; Lacroix, M. Antimicrobial effects of selected plant essential oils on the growth of a Pseudomonas putida strain isolated from meat. Meat Sci. 2006, 73, 236–244.

39. Bouhdid, S.; Skali, S.; Idaomar, M.; Zhiri, A.; Baudoux, D.; Amensour, M.; Abrini, J. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Origanum compactum essential oil. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 1563–1570.

40. Llana‐Ruiz‐Cabello, M.; Gutiérrez‐Praena, D.; Pichardo, S.; Moreno, F.J.; Bermúdez, J.M.; Aucejo, S.; Cameán, A.M. Cytotoxicity and morphological effects induced by carvacrol and thymolon the human cell line Caco‐2. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 64, 281–290. 41. Bauer, B.W.; Radovanovic, A.; Willson, N.‐L.; Bajagai, Y.S.; Van, T.T.H.; Moore, R.J.; Stanley, D. Oregano: A potential prophylactic treatment for the intestinal microbiota. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02625. 42. Kwamin, F.; Gref, R.; Haubek, D.; Johansson, A. Interactions of extracts from selected chewing stick sources with Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Bmc Res. Notes 2012, 5, 203.

43. Johansson, A.; Claesson, R.; Hänström, L.; Sandström, G.; Kalfas, S. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte degranulation induced by leukotoxin from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Periodontal Res. 2000,

35, 85–92.

44. Claesson, R.; Johansson, A.; Hanstrom, L.; Kalfas, S. Release and activation of matrix metalloproteinase 8 from human neutrophils triggered by the leukotoxin of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans.

J.Periodontal. Res.2002, 37, 353–359. 45. Kelk, P.; Abd, H.; Claesson, R.; Sandström, G.; Sjöstedt, A.; Johansson, A. Cellular and molecular response of human macrophages exposed to Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin. Cell. Death Dis. 2009, 2, e126. 46. Åberg, C.H.; Kelk, P.; Johansson, A. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans: Virulence of its leukotoxin and association with aggressive periodontitis. Virulence 2015, 6, 188–195.

47. Alsina, M.; Olle, E.; Frias, J. Improved, Low‐Cost Selective Culture Medium for Actinobacillusactinomycetemcomitans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 509–513.

48. Zbinden, R. Aggregatibacter, Capnocytophaga, Eikenella, Kingella, Pasteurella, and other fastidious or rarely encountered gram‐negative rods. In Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 11th Edition; American Society of Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp.652–666.

49. Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J.

Pharm. Anal. 2016, 6, 71–79.

50. Magaldi, S.; Mata‐Essayag, S.; DeCapriles, C.H.; Perez, C.; Colella, M.; Olaizola, C.; Ontiveros, Y. Well diffusion for antifungal susceptibility testing.Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 8,3 9–45.

51. Valgas, C.; Souza, S.M.d.; Smânia, E.F.; SmâniaJr, A. Screening methods to determinean tibacterial activity of natural products. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2007, 38, 369–380.

52. Adwan, G.; Abu‐shanab, B.; Adwan, K. In vitro activity of certain drugs in combination with plant extracts against Staphylococcus aureus in fections. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 4239–4241.

53. Boyanova, L.; Gergova, G.; Nikolov, R.; Derejian, S.; Lazarova, E.; Katsarov, N.; Mitov, I.; Krastev ,Z. Activity of Bulgarian propolis against 94 Helicobacter pylori strains invitro by agar‐well diffusion, agar dilution and disc diffusion methods. J. Med Microbiol. 2005, 54, 481–483.

54. Oettinger‐Barak, O.; Dashper, S.G.; Catmull, D.V.; Adams, G.G.; Sela, M.N.; Machtei, E.E.; Reynolds, E.C. Antibiotic susceptibility of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans JP2 in a biofilm. J. Oral Microbiol. 2013,

5, 20320.

55. Hammer, K.; Dry, L.; Johnson, M.; Michalak, E.; Carson, C.; Riley, T. Susceptibility of oral bacteria to Melaleuca alternifolia(teatree) oil in vitro. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2003, 18, 389–392.

56. Hammer, K.A.; Carson, C.F.; Riley, T.V. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils and other plant extracts.J.

Appl. Microbiol. 1999, 86, 985–990.

58. Maeß, M.B.; Wittig, B.; Cignarella, A.; Lorkowski, S. Reduced PMA enhances the responsiveness of transfected THP‐1 macrophages to polarizing stimuli. J. Immunol. Methods 2014, 402, 76–81.

59. Lund, M.E.; To, J.; O’Brien, B.A.; Donnelly, S. The choice of phorbol12‐myristate13‐acetate differentiation protocol in fluences the response of THP‐1 macrophages to apro‐inflammatory stimulus. J. Immunol.

Methods 2016, 430, 64–70.

60. Repetto, G.; DelPeso, A.; Zurita, J.L. Neutral red uptake assay for thee stimation of cell viability/cytotoxicity. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1125. 61. Johansson, A.; Hänström, L.; Kalfas, S. Inhibition of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxicity by bacteria from the subgingival flora.Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2000, 15, 218–225. © 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).