THE BUSINESS CASE FOR SUSTAINABLE SOURCING:

A Corporate Social Opportunity

HENRIK CHRISTENSSON BJÖRN HOLMDAHL

Master thesis in Industrial Engineering and Management

The School of Business, Society and Engineering, Mälardalen University Västerås

i

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This report is the degree project of our education, Industrial Engineering and Management at Mälardalen University. The study encompasses 30 ECTS and has been conducted in collaboration with Volvo Construction Equipment.

First of all, we would like to express our gratitude to Martin Oldaeus, our manager at Volvo, for providing us with this opportunity. Throughout our thesis he has provided us with guidance, assistance and opportunities to meet and learn from the professionals at Volvo. Additionally, we would like to express a special thanks to William Rydell, our mentor at Volvo. He has made us feel as a part of the Volvo team in Eskilstuna and has always been there to answer questions, or simply a laugh. We would also like to thank all of the employees at Volvo who have provided us with input or have been a part of our study in any way.

We would also like to thank our tutor Roland Hellberg as well as our collogues at Mälardalen University. Last but not least, we would like to extend our deepest gratitude to our families and friends, who have provided us with inspiration and encouragement. Not only in this project but throughout our entire education. All of you have been of great importance and without you, the project would not be the same.

Thank You!

Henrik Christensson Björn Holmdahl

ii

The Business Case for Sustainable Sourcing:

A Corporate Social Opportunity

Date: June 8th, 2020

Level: Master Thesis in Industrial Engineering and Management, 30 ECTS

Title: The Business Case for Sustainable Sourcing: A Corporate Social Opportunity (Affärsfallet för Hållbar Leverantörsutvärdering: En Social Affärsmöjlighet)

Authors: Henrik Christensson Björn Holmdahl

April 24th, 1993 April 7th, 1992

School: Mälardalen University

Institution: The School of Business, Society and Engineering Tutor: Roland Hellberg

Examiner: Pär Blomkvist

Principal: Volvo Construction Equipment Manager: Martin Oldaeus

iii

ABSTRACT

Sustainability has become a prevalent societal value and is ubiquitous in public discourse. Securing sustainable economic growth on increasingly globalized markets is perceived by many as one of the greatest challenges of our time. Supply chains have become globally dispersed and are increasingly complex to manage. Companies are experiencing higher expectations from their stakeholders in terms of their sustainability performance. They can no longer renounce responsibility for the actions of their suppliers and need to manage their sourcing activities so as to ensure sustainable supply chains. This poses a challenge but can at the same time present a business opportunity. There have been attempts to identify a business justification and rational for pursuing sustainability in sourcing. However, previous research has been primarily theoretical and has lacked practical applicability. The current study seeks to investigate the key features of the business case for sustainability. It also seeks to identify how the business case can be realized in sourcing activities. The current study has an exploratory design and revolves around a single case company. It utilizes both primary- and secondary data as well as a rigorous literature review. The primary data consist of a pre-study as well as interviews whereas the secondary data consist of a review of the current sustainability- and sourcing processes of the case company. The study culminates in a thematic analysis of the empirical data as well as a subsequent discussion. The empirical data indicates that the market is exhibiting an increasing demand for products with a strong sustainability profile. Additionally, it indicates that sustainable sourcing will become increasingly important for complying with regulations, attracting employees and reducing risk throughout the supply chain. Currently, suppliers’ sustainability performance is predominantly managed through the screening process and there is no functional metric available for practitioners to quantitively evaluate it. Rather than relying solely on sustainability requirements, the empirical data indicates that it is through cooperation and joint initiatives the greatest results can be achieved. We conclude that there is business case for pursuing sustainability as it: reduces risk and costs; increases companies’ ability to retain and recruit employees; cost efficiently comply with regulations; retain and attract customers and increase overall competitiveness. In order to realize the business case, it is imperative for companies to formulate clearly defined goals and subsidiary objectives to follow up on established trajectories. Since there is no metric suitable for measuring sustainability performance it is advisable to adopt a reductionist approach. The screening process should be devoted to binary variables while the evaluations process should be concerned with those who can be quantifiably evaluated. Companies should work closely with suppliers by identifying opportunities for synergistic value creation and engage in joint initiatives. Finally, companies need to communicate their efforts and achievements to all concerned stakeholders.

iv

SAMMANFATTNING

Hållbarhet har kommit att utvecklas till ett framträdande socialt värde och tar stort utrymme i samhällsdebatten. Många menar att en av vår tids stora utmaningar är att säkerställa hållbar ekonomisk utveckling på allt mer globaliserade marknader. Försörjningskedjor har blivit allt mer globalt spridda och svåra att hantera. Företag möter högre förväntningar gällande deras hållbarhetsarbete. De har inte längre en möjlighet att avsäga sig ansvar för sina leverantörers handlingar utan måste aktivt jobba för att säkerställa ett hållbart värdeskapande i sina försörjningskedjor. Detta innebär nya utmaningar men också nya möjligheter. Det har gjorts tidigare försök att identifiera ekonomiska motiv för hållbar leverantörsutvärdering. Tidigare studier har dock varit teoretiska och saknat praktisk applicerbarhet. Den här studien ämnar att undersöks huruvida hållbar leverantörsutvärdering erbjuder en affärsmöjlighet. Vidare ämnar studie att undersöka hur en sådan affärsmöjlighet kan realiseras i praktiken. Den aktuella studien har en explorativ utformning och fokuserar på ett enskilt fallföretag. Studien använder sig av både primär- och sekundärdata samt en gedigen granskning av relevant litteratur. Primärdatan består av en förstudie samt intervjuer medans sekundärdatan består av en redogörelse för fallföretagets hållbarhetsarbete samt för deras leverantörsutvärdering. Studien kulminerar i en tematisk analys och en efterföljande diskussion. Empirin visar att det finns en ökad efterfrågan för produkter med en stark hållbarhetsprofil. Den indikerar även att hållbar leverantörsutvärdering kommer att bli allt mer betydelsefullt för att uppfylla regulatoriska krav, attrahera personal samt att minska risker i försörjningskedjorna. För närvarande hanteras leverantörers hållbarhetsarbete genom screening-processer och det finns i dagsläget inget funktionellt mätetal som kan användas kvantitativ utvärdering. Snarare än att ställa krav, visar empirin att det är genom samarbete och gemensamma initiativ som man uppnår de bästa resultaten. Vi konkluderar att det finns en affärsmöjlighet i att jobba med hållbar leverantörsutvärdering då man kan: reducera risker och kostnader; öka företagets möjlighet att behålla och rekrytera personal; möta nya lagar och regler på ett kostnadseffektivt sätt; behålla och attrahera nya kunder samt öka företagets konkurrenskraft. För att realisera affärsmöjligheterna som finns måste företag etablera konkreta mål. I och med att det inte finns något mätetal som lämpar sig för att mäta hållbarhet borde företag använda sig av ett reduktionistiskt tillvägagångssätt. Screening-processen borde hantera binära variabler medans utvärderingsprocessen borde vara ägnad till de som kan kvantifieras. Företag borde jobba för att identifiera möjligheter att skapa ett gemensamt värde tillsammans med leverantörer och engagera sig i samarbeten. Slutligen är det viktigt att företag kommunicerar sina initiativ och resultat till samtliga berörda parter.

TABLE OF CONTENT

1 INTRODUCTION ... 3 1.1 Problem Statement ... 4 1.2 Purpose ... 5 1.3 Research Questions ... 5 1.4 Scientific Contribution ... 51.5 Scope & Delimitations ... 5

2 METHODOLOGY ... 6

2.1 Research Design ... 6

2.2 Primary Data Collection ... 7

2.2.1 Pre-Study ... 7

2.2.2 Interviews ... 7

2.2.2.1. Identification and Selection of Interviewees ... 8

2.3 Secondary Data Collection ... 9

2.4 Literature Review ... 9

2.5 Data Analysis ... 11

2.6 Evaluation of Methodological Approach ... 11

2.6.1 Validity ... 11

2.6.2 Reliability ... 12

2.6.3 Generalizability ... 12

2.7 Research Ethics ... 13

3 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 14

3.1 Corporate Social Responsibility ... 14

3.2 Sustainability ... 14

3.3 Stakeholder Theory ... 15

3.4 Supply Chain Management ... 17

3.5 Sustainable Supply Chain Management ... 17

3.6 Sourcing ... 19

3.7 Defining Concepts ... 21

4 LITERATURE REVIEW ... 22

4.1 The Business Case for Sustainability ... 22

4.1.1 Cost and Risk ... 23

4.1.2 Gaining Competitive Advantage ... 24

4.1.3 Reputation and Legitimacy ... 25

4.1.4 Synergistic Value Creation ... 26

4.2 Sustainable Sourcing ... 26

4.2.1 Criteria ... 27

4.2.2 Screening ... 29

4.2.2.2. Environmental Management Systems ... 30

4.2.2.3. Self-Assessments & Audits ... 30

4.2.3 Evaluation ... 30

5 ANALYSIS OF EMPIRICAL DATA ... 32

5.1 The Business Case for Sustainability ... 32

5.1.1 Reputation & Brand Image ... 32

5.1.2 Regulations & Risk ... 35

5.1.3 Joint Sustainability Initiatives ... 36

5.2 Sustainable Sourcing ... 37

5.2.1 Screening ... 37

5.2.2 Evaluation ... 39

6 DISCUSSION ... 41

6.1 The Business Case for Sustainability ... 41

6.1.1 Cost & Risk ... 41

6.1.2 Gaining Competitive Advantage ... 42

6.1.3 Reputation & Legitimacy ... 43

6.1.4 Synergistic Value Creation ... 43

6.2 Sustainable Sourcing ... 44

6.2.1 Screening ... 44

6.2.2 Evaluation ... 46

7 CONCLUSION ... 48

REFERENCE LIST ... 50

APPENDIX 1: CASE COMPANY ... 65

APPENDIX 2: INTERVIEWEES ... 72

APPENDIX 3: INTERVIEW QUESTIONS - SUSTAINABILITY ... 73

APPENDIX 3: INTERVIEW QUESTIONS – SOURCING ... 74

APPENDIX 4: INTERVIEW QUESTIONS - SUPPLIERS ... 75

DECLARATION OF FIGURES & TABLES

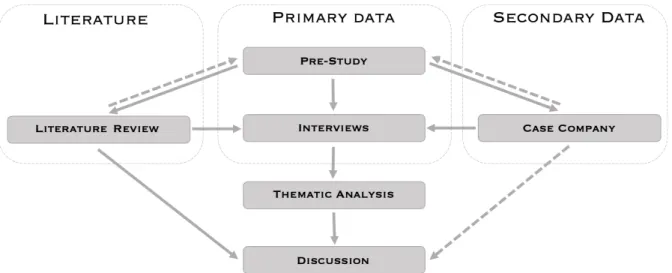

Figure 1. Research Design 6

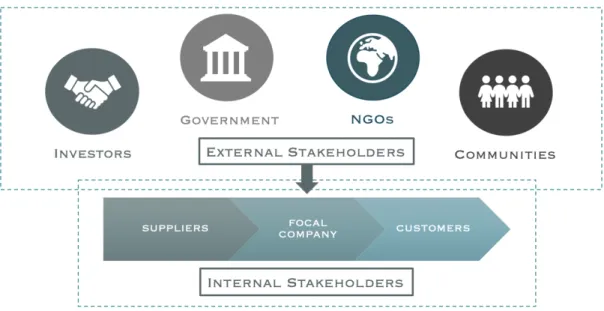

Figure 2. Internal & External Supply Chain Stakeholders 19

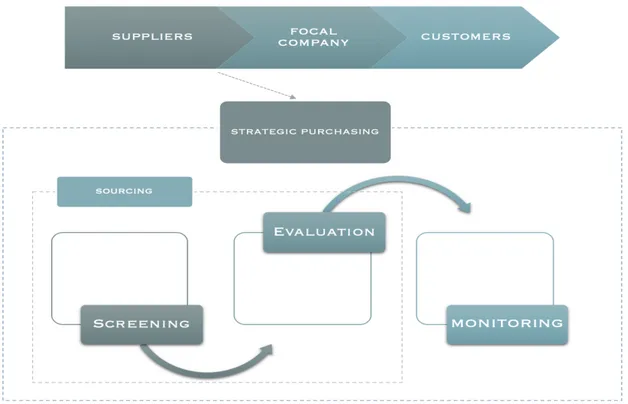

Figure 3. Conceptualization of Sourcing 20

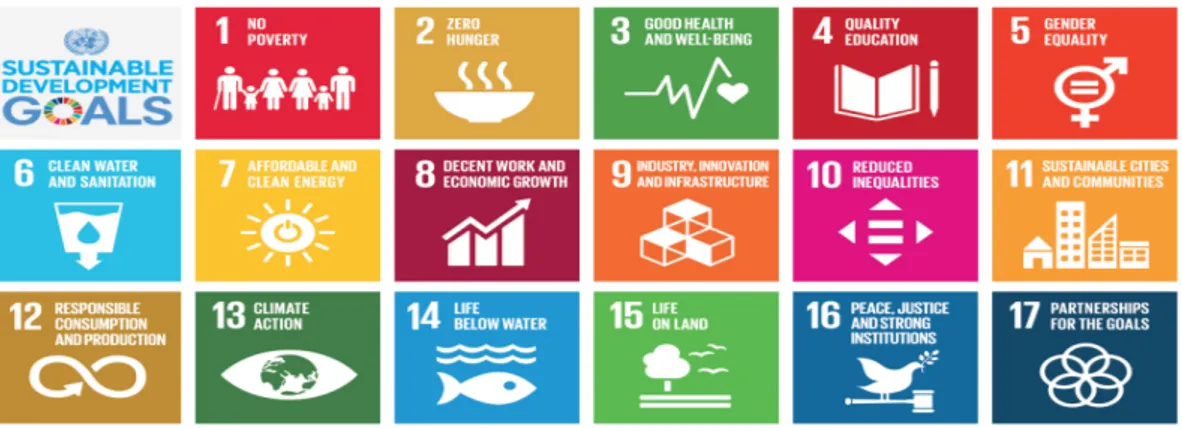

Figure 4. UN Sustainable Development Goals 66

Figure 5. Enterprise Risk Management – Sustainability Factors 67

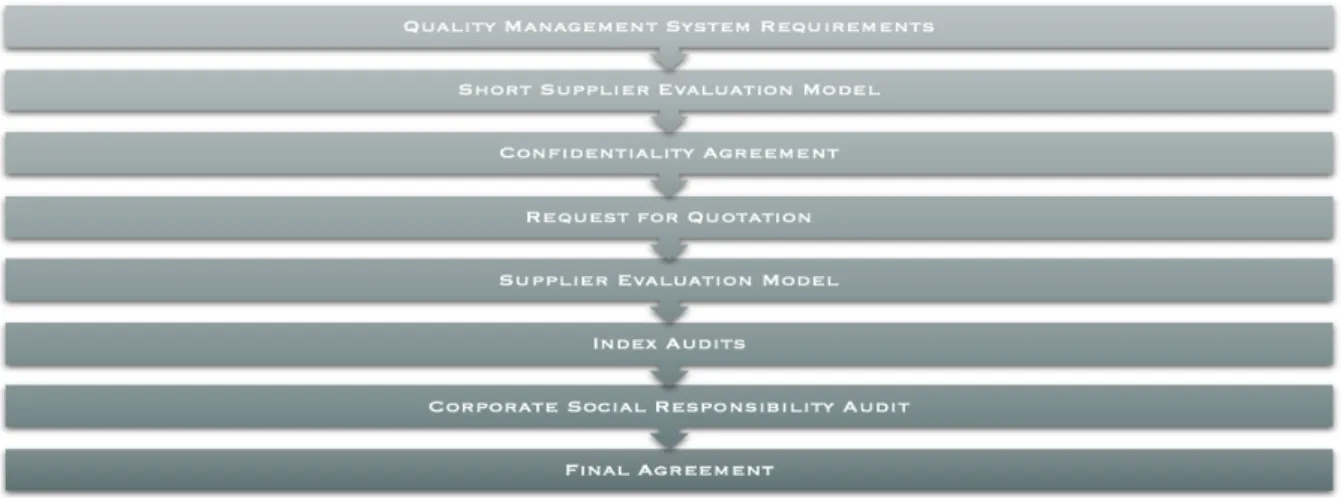

Figure 6. Sustainable Purchasing Program 68

Figure 7. Volvo Group Global Sourcing Process 70

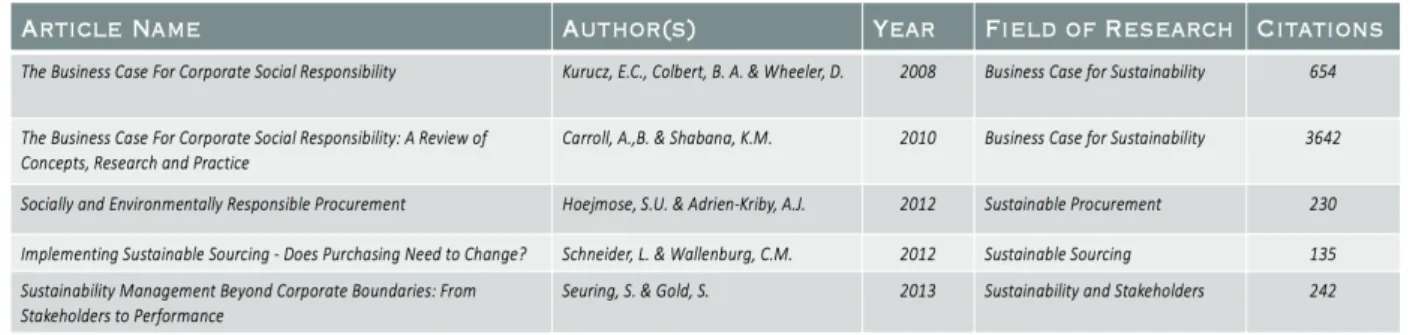

Table 1. Access Point Articles 10

Table 2. Definitions of Concepts 21

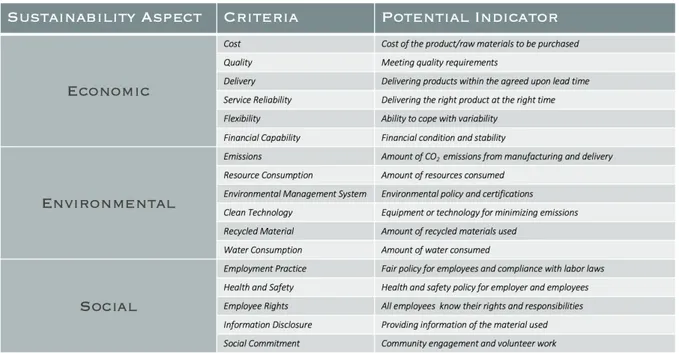

Table 3. Sustainability Criteria 28

Table 4. Interviewees – Sourcing 72

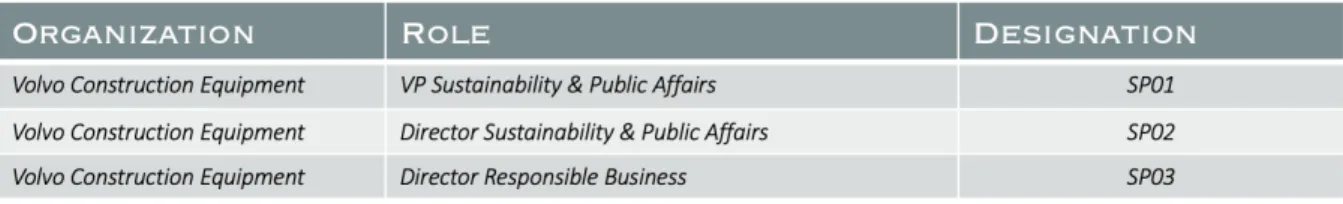

Table 5. Interviewees – Sustainability & Public Affairs 72

1 INTRODUCTION

In the last decades sustainability has undergone a transformation from a societal concept to an integral component of corporate management and strategy (A. Lee et al., 2009). Through continuous transformation the concept is portraying an increased complexity and interdependence of other global challenges (Reuter et al., 2012). Sprung from an increased public interest in sustainability, there has been a demand for companies not only to report their financial performance but also their social- and environmental performance (Hubbard, 2009). Companies are expected to contribute to collectively beneficial outcomes, and their role in ensuring a sustainable future are fundamental (Windolph et al., 2014). The evolving business climate is compelling companies to re-evaluate corporate strategy and to redefine current methods of measuring performance (Hubbard, 2009). Given the imperative profit-seeking in competitive markets, the question arises whether companies should contribute to the public good at the expense of profit (Reuter et al., 2012). This has been intensely debated and is shrouded in controversy. The traditional perception of sustainability as being a zero-sum game imposes an expectation to quantify and balance trade-offs between sustainability and profit (Burke & Logsdon, 1996). However, there has been an alteration in how sustainability is perceived and many now argue for the possibility of a win-win situation, where profit and sustainability are not mutually exclusive (Byggeth & Hochschorner, 2006). This prompts the question: how does corporate financial performance relate to the normative expectations of sustainability? Research on the relationship have shown mostly a positive correlation, however the empirical evidence is not conclusive (Barnett, 2007).

Companies are experiencing increased global competition and their value chains are becoming more geographically dispersed (Bozarth et al., 1998). To increase competitiveness, organizations are becoming leaner, focusing on their core competencies by outsourcing and leveraging supplier competence and technology (Kannan & Tan, 2002). These changes brought with them an increased complexity in business networks and magnified the importance of coordinating ones supplier base (Omurca, 2013). Once viewed merely as a support function for production (Carr & Smeltzer, 1997) upstream activities have evolved. They are now considered as some of the most important processes in terms of financial success (Sjoerdsma & van Weele, 2015). The perception of purchasing as fundamentally operational changed as companies realized its strategic importance (Carr & Smeltzer, 1997). Managers started to acknowledge purchasing costs’ impact on profitability (Scannell et al., 2000) and realized the strategic value of taking advantage of external competence (Tatikonda & Stock, 2003). In today’s business climate managers are faced with a number of difficult decisions and the intrinsic ad hoc nature of strategic purchasing implies constant revaluation, analyzation and a case by case approach (Tatikonda & Stock, 2003). Sourcing was conceived due to a growing dependence on suppliers, which made strategical selection critical (Sarkis & Dhavale, 2015). Identifying and selecting superior suppliers is a very complex process, requiring comparison and evaluation of several desirable dimensions (Omurca, 2013). Criteria used in supplier evaluation are most commonly those which are quantifiable, such as quality, delivery and cost. Their relative importance depends on the specific purchase (Omurca, 2013).

In the pursuit of corporate sustainability, the upstream activities play a particularly pivotal role (Carter & Easton, 2011). Cautionary tales where suppliers have transgressed established ethical standards and compromised the reputation, legitimacy and financial performance of the customer, amplifies the importance of managing suppliers’ sustainability compliance (Reuter

et al., 2012). Even so, in everyday business the reputational- and litigation risk of not managing suppliers’ sustainability compliance is frequently neglected in the pursuit of cutting cost and increasing profit (Reuter et al., 2012). Effective management of a company’s sustainability policies can arguably be obtained by integrating them in the process of screening and evaluating suppliers (Sarkis & Dhavale, 2015). The process of sourcing is already complex and integrating additional conflicting criteria add yet another dimension of complexity (Sarkis & Dhavale, 2015). There are some obstacles to integrating sustainability as a criterion (e.g. the difficulties of quantifying it; the tradeoff with the traditional criteria; the lack of supplier transparency and the difficulties of obtaining validated data of sustainability performance) (Genovese et al., 2013). In an attempt to simplify these complexities, some analytical tools have been developed for integrating sustainability in sourcing (Sarkis & Dhavale, 2015). However, according to Baskaran et al. (2012) mathematical models are perceived to be too complex for practical use, exposed to subjectivity and are dependent on qualitative indicators. Research on how sustainability can be integrated as a criterion for strategic supplier selection are limited (Winter & Lasch, 2016) and the corporate benefits of pursuing it is still ambiguous.

1.1 Problem Statement

To survive in the global business climate, companies have to be agile in order to cope with continuous evolvement. They experience increased complexity in their business networks and value chains which are becoming vastly dispersed (Omurca, 2013). They are no longer solely valued based on their financial performance as environmental and social performance per se have become a source of competitiveness (Winter & Lasch, 2016). The perceived importance of sustainability has been altered and many now argue for the possibility of financial benefits. (Carroll & Shabana, 2010). Krause et al. (2009) argue that “companies are only as sustainable

as the suppliers that compose their supply chain” (p. 21), which would emphasize the

importance of upstream activities in sustainability efforts (Carter & Easton, 2011). Companies are becoming leaner, focusing more on their core competence and the strategic significance of outsourcing and leveraging supplier competence is intensifying (Sarkis & Dhavale, 2015). The process of sourcing is complex and the traditional dimensions of selection criteria are often considered as insufficient (Omurca, 2013). Some argue for including sustainability as a criterion in screening and evaluation which may influence suppliers to improve their overall sustainability performance. Even so, this introduces another dimension of complexity to the process (Gualandris et al., 2014). In both practice and academia, the integration of sustainability as a criterion are becoming more common. However, there is seldom an evident business rationale or justification. The lack thereof impedes the use amongst practitioners and stresses the importance of further research to establish more applicable methods. Practitioners refer to a business case as “a pitch for investment in a project or initiative that promises to yield

a suitably significant return to justify the expenditure” (Carroll & Shabana, 2010, p. 92). For the

purpose of this report, a business case is conceptualized as the business justification and rationale for pursuing an investment. In the business case for sustainable sourcing, sustainability should be utilized as a means to ensure long term profitability rather than being the ultimate goal.

1.2 Purpose

The purpose of this study is to investigate which are the key features of the business case for sustainability. It aspires to present a business case which is substantiated by rigorous research consisting of a comprehensive literature review as well as empirical data. In order to fully capitalize on a potential business case, the study seeks to identify methods for realizing sustainability which are applicable to common sourcing operations.

1.3 Research Questions

RQ1: Which are the key features of the business case for sustainability? RQ2: How can the business case be realized in sourcing activities?

1.4 Scientific Contribution

This study combines different aspects of sustainability research with empirical observations in order to produce results which are practically applicable. Where previous research has been confined to the theoretical realm, the current study seeks to be of great importance to researchers and practitioners alike. There is an ambition to create clear incentives for businesses to adopt the presented ideas by emphasizing business rationale and justification. Even though a business case for sustainable sourcing has been investigated and discussed before, there is an apparent tendency to omit how practitioners can capitalize on the opportunity to create profits. Combining empirical research, in the form of interviews with salient stakeholders, and a comprehensive literature review, the study complements existing knowledge by bridging the gap between academia and business practices. Furthermore, the lack of clarity in regard to key terms and concepts are ubiquitous in prior research. The analysis, discussion and subsequent results presented in this report rests on a well-defined terminology provided by a robust theoretical framework.

1.5 Scope & Delimitations

The current study seeks to develop a business case for sustainability in terms of a general description of a business opportunity, rather than quantified estimations of net profit. Sourcing activities were limited to screening and evaluation of suppliers; excluding commonly associated activities such as managing relationships with suppliers and up-stream supply chain strategy development. This was deemed necessary in order for the study to be manageable and executed within the given time frame. A large variety of methods for implementing sustainability in sourcing were investigated, to provide an account of available approaches. Therefore, it was neither appropriate nor feasible to do any in-depth research on any individual method. Even though the current study includes all aspects of sustainability, the financial dimension of the concept is to no great extent referred to explicitly. Nonetheless, it permeates the study which puts an emphasis on applicability and business rationale. The study revolves around a single case company (i.e. Volvo CE) which is a manufacturer of heavy construction equipment. The case company was carefully selected so as the results would be indicative for the entire industry. Alas, extending the study to multiple cases could possibly provide more nuance. The scope encompasses the heavy construction equipment industry, but the researchers believe that the study can be of great benefit for parties operating in other sectors.

2 METHODOLOGY

The methodology section provides a detailed description and justification as for how the research was designed. This is done to improve the reliability and generalizability of the study. Furthermore, the interconnection between the different sources of data collection and a more detailed account of their individual structure is provided. Subsequently, an account is given for the method of analysis as well as a comprehensive evaluation of the overall methodology. The objective of the section is to offer transparency and to invite scrutiny.

2.1 Research Design

In the design of the study, the research problem served as the foundation and decisions were made to ensure validity and reliability. Previous research has to the most part been confined to the theoretical realm. Therefore, the researchers argue that the study encompasses a previously unexplored field of research. The aforementioned tendency to omit practical applicability incentivized a research design that would ensure results that could be utilized in business practices. The exploratory nature of the research problem and the absence of a hypothesis supported the use of a research design with intrinsic flexibility. An exploratory design was deemed suitable because it would allow adaptation to information and problems

ad hoc. To obtain in-depth insight, qualitative methods of data collection were chosen.

Furthermore, the composition of them was aimed at enhancing practical applicability and validity. The research was designed to consist of both primary- and secondary sources of data, a literature review, a thematic analysis and subsequently a discussion. This is illustrated in figure

1. Quantitative methods of data collection were not deemed appropriate since the objective was to investigate a complex cause and effect relationship with difficulties of quantification. Figure 1. Research Design

Note. This figure is an illustration of how the research was designed. The solid lines represent the primary flow of information whereas the dashed lines represent the secondary flow of information. Own illustration.

The primary data consists of a pre-study and interviews. The pre-study was used to establish a frame of reference and to explore and develop the relevance of the preliminary research problem. It was additionally the primary source for identifying salient stakeholders as interviewees. Through an iterative process, information gathered in the pre-study was used to

determine the scope of the literature review and interviews. In the literature review a theoretical frame of reference was established and a comprehensive account of prior research was compiled. The exploratory nature of the study called for a thorough review of literature to determine the scope of the current study. The interviews constituted the primary source of empirical evidence. They were used to extract information and to gain insights, which were only deemed obtainable from experts within the field. The secondary data consist of a review of the sustainability and sourcing processes of the case company. It did not provide answers to the research questions, rather it provided background to the analysis and complemented the information gathered in the interviews. The combination of a theoretical and practical perspective was used to ensure the relevance and adequacy of the interview questions. In the analysis, the interviews were analyzed thematically and was collated with the secondary data, to provide more substance. The study culminated in an extensive discussion based on the perspectives of the literature review and analysis.

2.2 Primary Data Collection

As previously mentioned, primary data was collected in both the pre-study and the interviews. The former consisted of unstructured interviews whereas the latter consisted of semi-structured interviews. An extensive account of their individual structure is provided in the subsequent section. The primary data collected through interviews and was considered the most relevant; therefore, it was treated accordingly.

2.2.1 Pre-Study

Investigating how sustainability can be realized in sourcing activities for enhancing, rather than impairing business performance, is complex and involves combining many different streams of knowledge. It was deemed necessary to devote great effort to find an appropriate approach and to identify relevant fields of knowledge to be further investigated. This process was crucial as many preexisting notions would be proven wrong. By conducting a pre-study, certain initial ideas could be discarded allowing new ones to take form. This resulted in narrowing down the scope of the study so as to be manageable. The pre-study consisted of a number of unstructured interviews with employees of the case company, who possessed insight, competence and expertise in the field of research. The interviewees consisted of sourcing practitioners, but company-internal experts on sustainability were also consulted. The pre-study was not executed in isolation, rather a constant exchange of input with the secondary data and literature review contributed to refining the purpose of the study.

2.2.2 Interviews

The interviews constitute the foundation of primary data. Even though the pre-study also provided information from first-hand sources, its purpose was to support and increase the relevance of the current study rather than directly contributing to existing knowledge. The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured fashion which allowed certain degrees of flexibility whilst being based on a framework of questions formulated ex ante. The interviews were conducted with the use of digital video meeting technology (i.e. Skype for Business). The interviews were conducted so as to feel less formal and more like a casual conversation in order to make the interviewees feel comfortable and encourage them to speak freely. All interviews were audio recorded so they could be re-visited and the risk of information loss due to real-time transliteration was eliminated. Audio recording also allowed the interviewers to focus on

the conversations rather than taking notes, further fostering a relaxed environment for open, honest and productive interviews.

The study’s exploratory nature and purpose was allowed to dictate the development of the interview questions. Formulating open-ended questions impeded the interviewees propensity to give short answers whilst encouraging comprehensive accounts of their subjective opinion. Thus, each interview could be taken full advantage of in terms of extracting relevant information. There was a conscious decision to avoid asking multiple questions at once so to ensure clarity as to what question the interviewee actually responded to. When conducting interviews, there is always an inherent risk of the results being contaminated by the researchers’ personal bias as they seek specific answers by asking leading questions (Kothari, 2004). This was taken into consideration when developing the interview questions, which was screened by a third party in order to strengthen the integrity of the data collection. Furthermore, all pre-formulated questions are included in the appendix with full transparency, to invite scrutiny. The interviews were conducted in Swedish with the exception of a few which were conducted in English. It was considered appropriate, when possible, to let the interviewees speak their native language as it allowed them to express themselves more freely. Interviews conducted in Swedish were subsequently transcribed to Swedish, but all data published in the report has been translated to English. Since the interviews were semi-structured there was room for opportunism as certain responses called for follow-up questions which increased the extraction of relevant information. In regards to bias and subjective interpretation, follow-up questions can be problematic (Rubin & Rubin, 2011). Formulating such questions using the interviewees’ own words safeguarded, to some degree, against such problems. It could have been fully avoided by conducting fully structured interviews, but such a method was deemed inferior due to the lack of freedom to capitalize on opportunities in real-time. The choice of interview structure was also related to the rigidity of the preparatory work as it made the interviewers (i.e. the researchers) knowledgeable within the field and able to ask relevant follow-up questions. The purpose and theoretical framework of the current study called for a heterogenic group of interviewees (i.e. stakeholders), each of which selected based on their ability to provide information from a specific point of view. In order to extract relevant information, the questionnaire was differentiated to some degree, in terms of order and formulations. This inevitably impairs comparability but strengthens the results without infringing on replicability (Kothari, 2004).

2.2.2.1. Identification and Selection of Interviewees

Considering how the study is structured, with stakeholder theory constituting the theoretical lens, the sample size was confined to the stakeholders of the focal firm. There was neither enough time nor resources available for all of these stakeholders to be interviewed which meant there had to be a strategic selection of those deemed most important. Their importance was judged based on their saliency as stakeholders which in the context of the current study is equivalent to their respective ability to impact financial performance. This in turn was determined based on information gathered from the literature review and the pre-study. It is important to note the difficulties of making such judgments with great accuracy. Fortunately, the analysis of empirical data did not necessitate an explicit ranking of stakeholders based on saliency. Due to the aforementioned constraints in time and resources, interviews could not be conducted with all stakeholder groups which had been deemed as salient. Rather, some stakeholder groups were strategically chosen to represent those which were not available to

be interviewed. A total of 11 interviews were conducted with stakeholders who had all been deemed as salient. Since the study puts an emphasis on applicability there was an apparent need to interview sourcing practitioners. Tapping into their knowledge and expertise provided crucial information in regard to how sustainability can be integrated in sourcing practices. Furthermore, internal experts in Sustainability & Public Affairs were interviewed. These interviewees all work in close collaboration with both customers, governments and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs). Therefore, they could arguably be representative and convey the demands of those stakeholder groups. Finally, since the study seeks to investigate sustainable sourcing practices, a supplier of the focal firm was interviewed. The interview method required a selection of interviewees which were not just relevant in terms of saliency as stakeholder but also possessed the right type of expertise and knowledge. Therefore, the selection process included screening of experience and specific position within each respective organization. For example, if a potential interviewee had only been in their current position for a short period of time or their professional duties was not directly connected to the relevant study, or at least appropriately adjacent to it, they were not included. VCE connected the researchers to potential interviewees but were to no capacity involved in the selection process, as that would make the study biased.

2.3 Secondary Data Collection

One of the most important aspects of the current study is that it aims at producing results which are applicable for real life practices. This permeates the entire research design and without investigating how companies incorporate sustainability in sourcing practices the study would lose relevance and run a risk of being stuck in the realm of academia. Investigating a large sample size of companies was deemed too time consuming so an alternative feasible method which did not compromise the final results had to be found. Therefore, a single case company was strategically selected and chosen based on the following set of criteria. It needed to: Be large enough to have well established procedures and processes; have a purchasing function with a global sourcing strategy; be purchasing a wide variety of products and have some pronounced sustainability ambitions. Volvo Construction Equipment (VCE) met all of these criteria and had the advantage of being easily accessible as one of their sourcing divisions was located in proximity to where the researchers were based.

As a part of the Volvo Group, VCE is intrinsically affected by the groups overarching goals and efforts. Much of the secondary data is therefore not exclusive for VCE, but rather concerns the entire group. It consists of consolidated information found on the Volvo Group and VCE’s websites. The information gathered consist of current sustainability initiatives as well as purchasing- and sourcing procedures. Confidential information which would have had to be omitted from the report was not used in any capacity, in order to provide full transparency and ensure replicability. Since it is not a primary source of data but rather complimentary information, it can be found in Appendix 1.

2.4 Literature Review

The theoretical foundation of the study is composed of two distinctive parts: a theoretical framework and a literature review. They fill different purposes, the former provides an account of key concepts and theory on which the study stands, while the latter contains a review of literature directly related to the research problem. By separating the two, the information

which is conveyed in the report becomes more accessible to the reader as semantic and theoretical discussions are contained within the theoretical framework. Following the same logic, it could be argued that the section is redundant. Even so, there is a large number of terms and concepts which, albeit ubiquitous in public discourse, are vague and lack definitions which are commonly known and recognized. By establishing a theoretical framework, the report seeks to bring clarity, mitigate unambiguousness and minimize the risk of misinterpretation. As stakeholder theory and supply chain management stands as the two main pillars of theory on which the study rests there is a relatively thorough review of them. Furthermore, concepts such as corporate social responsibility, sustainability and sourcing are discussed and defined. The literature review contains literature which covers the business case for sustainability and sustainable sourcing. These two combined forms a solid literary foundation for the current study and provides a review of current research within the field. There might be an apparent lack of focus due to the duality of the section, but the purpose of the research demands incorporation of different streams of knowledge.

Relevant literature was identified by using the snowball method in which a limited number of articles deemed relevant to the study acted as access points from which further research was identified. By reviewing the aforementioned articles’ sources, as well as articles which had cited them, more relevant information could be found. The “access point articles” were found using Google Scholar, complimented by PRIMO (a search tool provided by Mälardalen University). Search words used were: “sustainable sourcing, sustainable procurement, sustainability benefits and business case for sustainability”. Since they are crucial for the literature review the access point articles was not solely judged by the relevance of their respective topics but also by the number of citations and publication year. As illustrated in table 1. Lecy and Beatty (2012) discusses the snowball method in terms of levels where level one is the access point articles, level two articles which are cited in those articles and level three articles which are cited in level two articles. The method requires selectivity as the number of articles increases exponentially and in general, all relevant information has been mapped by going to level three (Lecy & Beatty, 2012). The current study went to level three in the mapping of relevant literature but to improve the coverage, additional searches were made using variations of aforementioned search words.

Table 1. Access Point Articles

Note. This table displays the access point articles used in the literature review, the number of citations and the publishing year was the primary indicators of their relevance. Own illustration.

2.5 Data Analysis

The study was deemed to require a sophisticated and systematic method of data analysis. The objective of the analysis was to convert data into clear, credible and transparent results. A thematic analysis was considered appropriate as it is a method used for identifying, interpreting and presenting themes in the dataset. However, a thematic analysis was solely applied to the primary data, the secondary data was not analyzed per se but rather served as a complement. According to Liamputtong (2009) there are a few main steps which a researcher should take when performing a thematic analysis. The steps are the following: familiarization with the data; initial coding; revising the tentative themes as well as structuring, defining and naming the themes. In the process of a thematic analysis, the steps mentioned by Liamputtong (2009) served as a foundation. Once data had been collected through the interviews, the researchers transcribed the data. In the process of transcribing, notes of initial thoughts were taken and sentences or paragraphs with high perceived significance was highlighted. Secondly, the transcribed information was screened for tentative themes and suitable codes were assigned to words and phrases. The codes were chosen so that they would comprise the essence of meaning and the codes were assigned to themes which encompassed them. The themes were then revisited and evaluated based on their perceived correlation to the codes across the dataset. A thematic map was then structured where the themes were defined and named. Each theme was assigned a number of codes and the themes was separated into two main categories, based on which research question they served as a basis for answering. Finally, the thematic map was used for analyzing the meaning of the themes and their correlation to the underlying research problem. The direct answers provided in the interviews, combined with the thematic analysis of underlying patterns and meaning was deemed a source of credible results. By incorporating these sources of empirical evidence to the information gathered in the case study, the analysis could provide holistic results. Thus, the aforementioned issues with practical applicability was addressed, yet providing results with validity, reliability and generalizability.

2.6 Evaluation of Methodological Approach

The exploratory research design and qualitative method of data collection have both its strengths and weaknesses. An exploratory design’s intrinsic flexibility was the most significant benefit, because it would allow the study to adapt to new information and obstacles ad hoc. The most prominent disadvantage of the methodological approach was limited generalizability due to the sample size. However, this was considered to be outweighed by the increased validity which the design provided. Consistency in the data collection process was the most significant measure of increasing reliability. However, some may argue that the use semi-structured interviews could impair it. A major obstacle which would come to impair the study was the outbreak of the COVID19 pandemic. It obstructed the interview process by limiting the sample size of interviewees and forced most interviews to be conducted through Skype rather than as personal interviews, which would have been preferred.

2.6.1 Validity

Several measures were taken to increase validity. The research was designed through a rigorous process, where several different design choices were evaluated. With a tripartite method of data collection, the researchers could validate the primary data obtained through the

interviews with the secondary data collected through the literature review and case study. The qualitative method chosen was deemed to significantly increase validity, by providing a deep insight to the research problem. The use of quantitative method could have infringed it, whilst it would have improved reliability. By adopting an exploratory design, the researchers could adapt to information ad hoc and the interview questions could be more accurately phrased. However, the exploratory design could be argued to increase the risk of researchers’ bias affecting the study. In an attempt to minimize this risk, the interview questions were carefully and precisely worded. The sampling process was deemed the most important measure. According to the theoretical lens of the study (i.e. stakeholder theory), all interviewees were chosen through a rigorous process. Through the pre-study and the literature review, salient stakeholders were identified and chosen as interviewees. The process was considered an important measure, since the selected interviewees was not only considered experts in their field but also due to their saliency as stakeholders to the focal company. Extending the study to include more interviewees and to potentially observe several case companies could have increased the validity, albeit, due to the time constraint this was not deemed feasible.

2.6.2 Reliability

By providing a detailed account of the research design and the reasoning for the choices made, the researchers sought to provide full transparency. In the case study no confidential information was used, which was a measure for increasing the reliability. Although confidential information could have provided further valuable information, it was perceived as damaging to the reliability. The most important measure for increasing reliability was to apply the methods used consistently. Therefore, the researchers sought to ask the questions in the same order and phrase the questions in the same way in each interview. The semi-structured nature of the interviews could be argued to infringe with reliability, since follow-up questions may differ from interview to interview. Yet, this was deemed to be compensated by the positive effects on validity. The opportunity to ask follow-up questions, allowed more in-depth insight and provided an ability to probe interviewees further in their specific areas of expertise. Furthermore, the use of a thematic analysis sought to provide further transparency, by providing insight to how the collected data was analyzed.

2.6.3 Generalizability

In terms of generalizability, the sample selection process was identified as a primary obstacle. The selection of a single case company may be argued to impair with how representative the results are for other sectors of industry. This was taken into consideration when designing the study, since the purpose was to provide business justification and rationale for pursuing sustainability in sourcing. However, it was deemed more important to provide valid results than to ensure generalizability. An alternative research design could have encompassed several case companies. Even so, by studying a single case a wider spectrum of salient stakeholders could be included in the study. Thus, substantiating a more accurate business case for sustainability.

2.7 Research Ethics

This study was conducted ethically in accordance with principles and guidelines provided by the Swedish Council of Research (SCoR). There are two main issues regarding ethical research: the nature of the research itself and the researchers personal conduct (Swedish Research Council, 2019). As for the former, the researchers hope that the results produced in the study can be used to increase sustainability in business practices and thus contribute to assuring sustainability on a societal level. There is a desire that the results presented in the study will provide incitement for businesses to be more sustainable in their sourcing practices. The researchers dispute any potential claims that the study encourages “green washing” or any other maleficent business practice. Any and all ideas brought forth in this report is aimed at creating a gain, not only for the focal firm, but for society as a whole. If you see to the personal conduct of the researchers, SCoR refers to four guiding principles presented by All European Academies (ALLEA). These principles guided the study and dictated how it was conducted. The four principles are listed below and are direct citations from the report The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity published by ALLEA (2017):

- “Reliability in ensuring the quality of research, reflected in the design, the methodology, the analysis and the use of resources.”

- “Honesty in developing, undertaking, reviewing, reporting and communicating research in a transparent, fair, full and unbiased way.”

- “Respect for colleagues, research participants, society, ecosystems, cultural heritage and the environment.”

- “Accountability for the research from idea to publication, for its management and organization, for training, supervision and mentoring, and for its wider impacts.” The study has since its infancy been open to scrutiny and has welcomed input and constructive criticism. All information presented in this report which pertains previous research on the subject is heavily cited as to assure reliability. Furthermore, all definitive statements, which are not presented as conclusions drawn from observation done in the current study, are cited and based on previous research. In the case of direct citations, it is made clear that they are direct citation and there is no ambiguousness as to who the originator of the statement is. The interviewees were fully informed of the context for which the interviews were to be used and got a briefing of the current research ex ante. No information was kept from the interviewees and all questions directed at the nature, purpose and confidentiality of the research, was answered truthfully by the researchers. All interviewees were informed and fully aware that the interviews were being recorded and given the opportunity to go through the recordings after the interviews were concluded so as to assure their opinions were not being misrepresented. Some information regarding the interviewees were deemed necessary to include in the report as it strengthens the integrity of the research. The information includes; current position, which organization they represent and how they relate to the focal company. All interviewees were informed and made aware of this and was given the opportunity to be anonymous to the extent that aforementioned information was not being excluded.

3 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

In the current field of research there is seemingly little to no conceptual consistency, clarifying terms and concepts is of utmost importance for improving clarity. The theoretical framework provides background and a semantic discussion of some core concepts. Furthermore, reoccurring and particularly ambiguous concepts is discussed and subsequently definitions are provided. This is done with the ambition of reducing the risk of misinterpretation and to increase clarity. Stakeholder theory is the theoretical lens being used in the study; therefore, it is also encompassed in the theoretical framework to serve as a basis for the identification of salient stakeholders.

3.1 Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is a continuously evolving concept and remains relevant

in both practice and research (Lindgreen & Swaen, 2010). The concept emerged out of concern that corporations enjoyed too much power without responsibilities or repercussions (D. J. Wood, 1991). Arguably, the concept was conceived in 1953 when Howard R. Bowen published his seminal work: Social Responsibilities of the Businessman (Carroll, 1999). In his book Bowen (1953) described the social responsibilities of businessmen as: “the obligations of businessmen

to pursue those policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of action which are desirable in terms of the objectives and values of our society” (p. 6). One of the fundamental

ideas of CSR is that business and society are interconnected and that society holds companies accountable for their actions (D. J. Wood, 1991). To take social responsibility is not merely to be compliant with minimum requirements, it requires taking an additional step, undertaking a social responsibility which goes beyond those of the law (Davis, 1973). The term was coined by researchers and there is lack of clarity which has made it difficult for businesses to embrace (Clarkson, 1995). With the intent of addressing and quantifying the social and environmental impact of corporate actions, the concept of corporate social performance was coined (Husted, 2000). Clarkson (1995) argue for the importance of measuring performance, which unlike responsibility is quantifiable. When assessing corporate social performance what should be considered is: to which degree social responsibility motivate corporate actions; the social responsiveness of corporate processes and the impact of corporate actions, programs and policies (D. J. Wood, 1991).

3.2 Sustainability

Sustainability is a frequently conceptualized to reflect socially desirable attributes (Holden et al., 2014). The concept is particularly ambiguous and difficult to define (Vos, 2007). Arguably the definition most frequently referred to originates from the report ‘Our Common Future’ (the Brundtland Report) published in 1987 by the UN World Commission on Environment and Development (Ameer & Othman, 2012; Holden et al., 2014; Meadowcroft, 2007; Vos, 2007). The report is often accredited with popularizing sustainable development (Meadowcroft, 2007; Purvis et al., 2018) where it is defined as: “it meets the needs of the present without

compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987, p. 16).

Sustainability has ever since its conception been prominent within research, in public discourse and in corporate strategy (Meadowcroft, 2007). Although being both very complex and contested, it is no longer solely viewed as an ideology but rather as a political concept or principle (Lindgreen & Swaen, 2010). Not unlike other political concepts, such as ‘democracy’, ‘justice’ and ‘liberty’ it has the power to concentrate and guide public discourse. However, it

remains exposed to re-interpretation and examination (Gladwin et al., 1995; Meadowcroft, 2007). Sustainability is often thought of as being socially just and ethically correct (Hansmann et al., 2012) and is often conceptualized to have three dimensions or ‘pillars’: environmental, social and financial. These illustrate the difficulties of balancing trade-offs between three equally desirable dimensions (Purvis et al., 2018). Albeit very similar and often used interchangeably, there is a slight difference between the terms ‘sustainability’ and ‘sustainable development’. An advantage of the former is the required context-specificity for exactly what is being sustained (Sneddon, 2000), which the latter does not. An issue associated with the term ‘sustainable development’ is that the notion of development is often equated with growth (Purvis et al., 2018). The vagueness and ambiguousness of the term ‘sustainable development’ solicitates the exclusive use of the term ‘sustainability’ in this report.

Ever since the concept emerged, a multitude of definitions and vastly diverse interpretations has been generated (Vos, 2007). Unfortunately, the original definition of the Brundtland commission, not unlike many subsequent ones, are ambiguous and far-reaching. Thus providing limited guidance for organizations (e.g. how to distinguish the needs of the present from the needs of the future) (Carter & Rogers, 2008; Gimenez et al., 2012). In ‘Caring for the Earth’ 1991, the World Conservation Union, United Nations Environment Program and the Worldwide Fund for Nature defined sustainability as “improving the quality of human life while

living within the carrying capacity of supporting ecosystems” (IUCN et al., 1991.). This definition

focuses primarily on the ecological limits and not unlike its predecessor this definition is far-reaching and vague. Pezzey (1992) defines sustainability as “non-declining utility of a

representative member of society for millennia into the future” (p. 323). This definition can be

interpreted to suggest an equity constraint rather than considering sustainability simply as desirable goal. Furthermore, it addresses the indefinite time horizon of sustainability. None of the aforementioned definitions are sufficiently conclusive or explicit for the purpose of this report. Vos (2007) argue that you have to consider ‘what’ is actually being sustained for future generations when defining sustainability (e.g. key values of society, quality of life or our ecological system). In an article by Sikdar (2003) sustainability is described as “a wise balance

among economic development, environmental stewardship and social equity” (p. 1928). This

arguably encompasses ‘what’ is being sustained and unless otherwise stated, sustainability will be defined accordingly throughout this report.

3.3 Stakeholder Theory

The normative stakeholder theory can be considered as an extension of CSR, declaring the role and obligation of corporations (Buysse & Verbeke, 2003; Laplume et al., 2008). Managers and executives ought to make the “right” decision and the theory can be seen as a code of business ethics for them to act accordingly (H. Smith, 2003). Stakeholder theory asserts that managers have the obligation to act in accordance with shareholders but also any other individual or constituent which does in any way contribute to the wealth creation of the company (Jensen, 2010; Wagner Mainardes et al., 2011). What constitutes a stakeholder is anyone who may act as a potential benefit or risk to the corporation (Donaldson & Preston, 1995; H. Smith, 2003). Stakeholders may include but are not limited to: customers, suppliers, financiers, owners, internal personnel or external pressure groups (Donaldson & Preston, 1995; Freeman, 1984; Schilling, 2000; Wreder et al., 2009). Stakeholder theory state that corporate managers have two main responsibilities: to ensure that the ethical right of no stakeholder is breached (Laplume et al., 2008) and to balance the interest of all stakeholders’ in decision-making

(Donaldson & Preston, 1995; Wagner Mainardes et al., 2011). In essence stakeholder theory state that it is of utmost importance for a company to adhere to the interest of its stakeholders even if the consequence is a reduced profitability of the company (Laplume et al., 2008). Stakeholder theory differs significantly from the traditional management theories, where profit is the sole reason for companies existence, and the shareholders are the one and only stakeholders of the company (Donaldson & Preston, 1995). Friedman (1962) argued that there is one sole social responsibility of business, to increase its profits under free competition, practicing neither deception nor fraud. In his seminal book Strategic Management: A

Stakeholder Approach, Freeman (1984) challenged the traditional shareholders’ theory by

introducing the notion of stakeholders, hence he is often accredited to be the founder of stakeholders’ theory (Donaldson & Preston, 1995; Garvare & Johansson, 2010; Laplume et al., 2008; Wagner Mainardes et al., 2011). In the book he argue that companies should strive to create value not only for shareholders but rather to any party with a stake in the consequences of its actions. (Laplume et al., 2008; Wagner Mainardes et al., 2011) He also asserted that corporate management was not ready for the upcoming changes in the business environment (Laplume et al., 2008). Freemans work spurred great interest in the academic world. Such an interest that according to Jones and Wicks (Jones & Wicks, 1999) there had been over a hundred articles and a dozen books published which covered stakeholder theory by the year of 1995, a mere 11 years after the book’s publication. Corporate activities, not aimed at creating profit, was a growing practice during the time and companies soon realized they needed a system to account for those efforts (Jones & Wicks, 1999).

Sprung from the surge of stakeholder theory and a growing public interest in corporate responsibility the concept of triple bottom line accounting emerged (Hubbard, 2009). It is an accounting framework, based on the three pillars of sustainability (Gutowski, 2011). According to the researcher who coined the expression, John Elkington, he started to use triple bottom line publicly in 1994 (Henriques & Richardson, 2013). Elkington published an article that year in which he argued for the benefits of a three dimensional accounting framework (Elkington, 1994) but the term did not appear explicitly in the literature until the year 1998 (Elkington, 1998). Since its conception it has become common in for-profit, nonprofit and government sectors performance reports (Gutowski, 2011). Even though it has been able to accumulate a vast number of advocates, triple bottom line has also had a lot of criticism aimed towards it. With the tools available today it is hard to quantify social and environmental efforts (Gutowski, 2011). Hence, there is an undeniable arbitrariness to what is accounted for (Norman & MacDonald, 2004). Independent of the criticism, corporations and other organizations are undeniably under a lot of pressure to monitor and account for more than just their financial performance (Hubbard, 2009).

There is no clear definition of what constitutes a stakeholder and practitioners seldom define the concept themselves (Donaldson & Preston, 1995). In research however the definitions are numerous, but none is conclusive and widely accepted. In his original work, Freeman (1984) defined a stakeholder as “all of those groups and individuals that can affect, or are affected by,

the accomplishment of organizational purpose” (p. 25). Other researchers follow the same

premise and reflect a similar principle, such as (Wagner Mainardes et al., 2011) who stated that

“the company should take into consideration the needs, interests and influences of people and groups who either impact on or may be impacted by its policies and operations” (p. 228). Evan

& Freeman (1988) consider stakeholders as “those groups who are vital for the survival and

adopted also in this report, to emphasize the impact of stakeholders on business, rather than the contrary.

3.4 Supply Chain Management

In today´s business-performance discourse the term Supply Chain Management (SCM) is ubiquitous and has become a primary competitive tool of modern corporations (Hult et al., 2007; Re, 2004). This has not always been the case (Hult et al., 2007), rather a multitude of macroeconomic and managerial trends have paved the way for it to become an integral part of modern business practices (Seuring et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2008). There was a clear shift in the end of the 20th century where previous ambitions of vertical integration as a means to become self-sufficient was pushed aside for a more streamlined approach (Mullin, 1996; Prahalad & Hamel, 2006). During the 1970’s, managers started to realize that there was a business opportunity in divesting, externalizing support activities and focusing on core competencies (Kakabadse & Kakabadse, 2005). Even though companies saw the advantages of outsourcing early on (Harland et al., 1999) it was not until the 1990’s corporate supply chains were truly globalized. During this time, practitioners and researchers started to realize the importance of a holistic approach to corporate management, encompassing both internal and external operations (Sweeney et al., 2015).

The term supply chain management is commonly believed to have been coined by a consultancy firm in the early 1980’s (Sweeney et al., 2015) but was only used sporadically until a decade later when it started to make a significant presence in the academic literature (Alfalla-Luque & Medina-López, 2009). Even though the concept has been widely investigated and researched the definition of it is still ambiguous (Mentzer et al., 2001). It has been pointed out that the vagueness of the term might to some extent complicate its practical use (Janvier-James, 2011) and that consensus regarding a single definition would improve work within the field (Mentzer et al., 2001). Even so, there are numerous definition available which can provide understanding and insight. (Mentzer et al., 2001). As to bring clarity and reduce confusion regarding the term Stock and Boyer (2009) performed a qualitive analysis which included 166 definitions and resulted in a proposed definition which encompasses all aspects of the concept:

“The management of a network of relationships within a firm and between interdependent organizations and business units consisting of material suppliers, purchasing, production facilities, logistics, marketing, and related systems that facilitate the forward and reverse flow of materials, services, finances and information from the original producer to final customer with the benefits of adding value, maximizing profitability through efficiencies, and achieving customer satisfaction”. (Stock & Boyer, 2009, p. 706)

Arguably the most simplistic and common illustration of the supply chain is that which depicts the relationship of three actors: supplier, focal firm and customer. This is illustrated in figure 2 as it represents an easily accessible depiction of the concept. For the remainder of this report, the term supply chain refers to what is depicted in figure 2.

3.5 Sustainable Supply Chain Management

SCM rose in prominence during the last decade of the 20th century and it did not take long before corporate responsibility got attached to it (Touboulic & Walker, 2015). Even though the concept of a sustainable supply chain was conceived in the 1990’s (Seuring et al., 2008) it was

not until the following decade it really got a foothold in the academic community (Gold et al., 2010; Millington, 2008; Seuring & Müller, 2008). In its infancy, research on Sustainable Supply

Chain Management (SSCM) was primarily concerned with issues such as bribery (Pitman &

Sanford, 1994) and ethical purchasing (G. Wood, 1995). The first published definition can be found in an article from 1996 (Touboulic & Walker, 2015) by Green et al. (1996) which states that: “Green supply refers to the way in which innovations in supply chain management and industrial purchasing may be considered in the context of the environment” (p. 188). The definition does neither include nor allude to SSCM explicitly, rather it refers to a term called Green Supply. There is a general problem related to the apparent arbitrariness of the terminology which has resulted in a lack of a concept base (Carter, 2011). This might impair research within the field as well as corporate application (Chen & Paulraj, 2004). There is a lack of consistency which is evident by the number of different terms used in the literature (Schneider & Wallenburg, 2012). These include, but are not limited to: Green supply (Green et al., 1996); Environmental Supply Chain Dynamics (Hall, 2000); Green purchasing (Zhu & Geng, 2001); Supply Management Ethical Responsibility (Eltantawy et al., 2009) and Sustainable Supply Chain Management (Pagell & Wu, 2009; Spence & Bourlakis, 2009; Tate et al., 2010). The purchasing function of a company is one the most influential on its sustainability performance (Tate et al., 2010; Windolph et al., 2014) since organizations are only as sustainable its upstream supply chain (Handfield et al., 2005; Krause et al., 2009). Companies are now functioning on a supply chain level and according to Seuring et al. (2008) they are increasingly being held responsible for the sustainability performance of upstream activities. Hoejmose and Adrien-Kirby (2012) present three key “drivers” of what they choose to call

Socially and Environmentally Responsible Procurement (SERP): Globalization, fragmented

supply chain and stakeholder pressure. Stakeholder theory is prominent within the field of SSCM and is only second to Resource Based View the theoretical lens most commonly used by researchers (Touboulic & Walker, 2015).

Even though there is a large body of literature which has investigated SSCM in terms of stakeholders’ theory (e.g. Buysse & Verbeke, 2003; Delmas, 2001; Park-Poaps & Rees, 2010; Wolf, 2014), there are few who does so with the intent of valuating the opportunity to increase competitiveness. The available literature is concerned with exploring the drivers of implementation (Hoejmose & Adrien-Kirby, 2012; Sajjad et al., 2015) and to some extent the identification of stakeholders’ concerns (Schneider & Wallenburg, 2012). Even though these studies provide an important account of salient stakeholders and how these relate to sustainability they fail to provide an explicit connection to competitiveness. In sustainability management, stakeholders have often been divided into those who are either external or internal to the firm (Hoejmose & Adrien-Kirby, 2012). The former includes, among others: customers, governments, investors and suppliers as the latter refers to for example: managers and employees. Looking beyond the field of sustainability, Harrison et al. (2010) proposes a framework for the management of stakeholders and value creation where the primary stakeholders are listed as: Owners, Customers, Organizational members and Suppliers. Research has shown how crucial the identification process of stakeholders is (Buysse & Verbeke, 2003). Even so, due to the purpose and scope of this report a thorough investigation will not be conducted. Instead, the consolidation of relevant research (e.g. Hoejmose & Adrien-Kirby, 2012; Schneider & Wallenburg, 2012; Walker et al., 2012) reveals that the following are most important to include: investors, governments, NGOs, communities, customers, suppliers and employees. These are illustrated in figure 2.