The Making of ‘Sustainable

Consumerism’

A critical discourse analysis of the discourse of sustainability found in

Oatly’s product advertisements

Julia Lindkvist

English Studies - Linguistics Bachelor Thesis

15 credits

Spring semester 2020

Table of Contents Abstract ... 1 1. Introduction ... 2 1.1 Aim ... 2 2. Background ... 3 2.1 Situational background ... 3 2.1.1 Sustainability ... 3

2.1.2 The Sustainable Food Industry ... 3

2.1.3 The Plant-based Food Industry ... 4

Oatly ... 5

2.2 Theoretical and Methodological Background ... 5

2.2.1 Advertising as discourse ... 5

2.2.1 Critical Discourse Analysis ... 7

2.2.2 AIDA as a conceptual framework ... 8

2.3 Previous works ... 9

3. Design of Study ... 10

3.1 Data and material ... 10

3.1.1 Material ... 10

3.2 Method ... 11

4. Results & Discussion ... 11

4.1 Textual analysis ... 11

4.1.1 Product descriptions on website ... 12

4.1.2 Packaging in-store ... 21

4.2 Comparison of advertising strategies on the two platforms ... 25

5. Conclusion ... 25

Abstract

With the help of various advertising strategies this study addresses the Swedish, plant-based food-production company Oatly, and their advertisements to see how the discourse on sustainability is approached. By using critical discourse analysis, and primarily Fairclough’s three-dimensional-model for analysing discourse (1989, 1995) as well as the marketing framework AIDA, these advertisements have been analysed to see how the company manages to tempt and persuade their consumers into consumption. This paper seeks to understand how Oatly portrays their products as the “right” choice, by acting on and creating social, public understandings. But who decides what is “correct” and what is not, and how does a company act on contemporary social conventions to portray themselves as the “good” choice? Through a textual analysis of Oatly’s product descriptions on their website as well as of the product packaging in-store, this report has established that Oatly acts on public

understandings of environmental sustainability to persuade their audience into consumption.

1. Introduction

In today’s markets, businesses are expected to be accountable for their impact on the global environment, with increasing pressure from stakeholders. Because of this, companies employ various strategies to contribute to global sustainable development. Thus, by identifying and framing environmental issues in their advertisements, companies can shape public

understanding of the given discourse.

One increasing contribution to sustainable development is the plant-based food industry, and the adaption of such diets is increasing throughout the world (Jones 2020; Frangoul 2020). This increase creates opportunities for food production companies to create products that meet the consumers’ demands, with products and services that facilitate the everyday of individuals following a plant-based diet or individuals simply wanting to minimize their carbon footprints. Thus, by advocating pro-environmental benefits of their products through product advertisements, companies are able to increase their sales.

A company that already seized this opportunity and managed to contribute to the market with sustainable products is Oatly (Ridder 2019). With catchy advertisements and skilful marketing strategies, Oatly is on the rise to crush the dairy alternative market (“How Oatly became the oat milk brand to beat” 2020). However, Oatly has been facing criticism throughout the years from agricultural farmers as well as consumers, as they have been vilifying the dairy industry as the thieves of the global environmental degradation and

questions around sustainable consumption have thus arisen (Woodford & Trimble 2019). Can consumption really be sustainable if the goods we purchase are not necessities?

1.1 Aim

This study will investigate the discourse of environmental sustainability in Oatly’s product advertisements. Critical Discourse Analysis will be used as a support to examine how Oatly approaches environmental sustainability and how they portray their products to be sustainable and ethical, i.e. the “right choice” through advertising. This will be done by examining and comparing methods of advertising strategies on Oatly’s product descriptions on their website and product packaging in-store. With advertising theories, in combination with CDA and AIDA as framework, this study will seek to answer the following research questions:

1. What linguistic advertising strategies does Oatly take advantage of when using the discourse of sustainability to make people buy into their beliefs and products?

1.1 Does Oatly portray their products as the ‘right choice’, and if so, how? 1.2 How does Oatly’s advertising language attempt to persuade the customer

to buy their products?

2. What different/similar strategies are present in their advertising on packaging in-store and product descriptions on their website?

3. How does Oatly’s approach to the discourse of sustainability relate to the wider social context?

2. Background

In order to investigate how Oatly approaches the discourse surrounding sustainability with various advertising strategies, and how advertisers contribute to the public apprehension of environmental issues, one must first understand the present social context.

2.1 Situational background

According to Fairclough (1989), language is a form of social practice. This, he means, is because language is a part of society, a social process that is conditioned by other parts of society. He argues that all humans’ actions are determined by social conventions, and even when people believe themselves to be cut off from social influences, they use language that is subject to a particular social phenomenon (1989). Therefore, to analyse verbal as well as visual language, one must consider the society in which it is produced.

2.1.1 Sustainability

Environmental issues can be many things: air pollution, deforestation, population growth, etc. To monitor and limit these issues, the earth’s resources must be balanced which can be achieved by sustainable development. With sustainability, one means the act of reducing human footprints on the environment as well as preserving natural resources for future generations (Morawicki 2012).

2.1.2 The Sustainable Food Industry

The modern food system is contributing to widespread environmental damage and inadequate health and livelihoods of the global populations (Baldwin 2015). The dominant source of environmental degradation by food supply is the agricultural production, and thus the goal of sustainability in the food industry is to produce and consume foods that support the well-being of future generations (2015).

Many individuals in today’s societies seek environmentally friendly alternatives and for ways to reduce their carbon footprints (Boström & Klintman 2011). As a result,

companies employ various strategies to make their contribution to the global environment more sustainable. This might be done by approaching a long-term sustainability program due to ethical reasons. Yet what motivates businesses today might rather be because “it is

becoming important in public perception” (Morawicki 2012:17). When companies make environmental claims about a product or service, they attempt to attract more customers to increase their sales (2012). By labelling products with positive connotations such as

“sustainable”, the advertiser can inform customers about environmental qualities that might otherwise not be present in their claims (2012). This creates a competitive advantage in relation to alternative products offered by competitors, where such labelling is not used, or where the environmental advantages are not emphasized (2012). As a result, consumers might express their political views by choosing the products that use the environmental labels and boycott the products that do not (Boström & Klintman 2011). However, it can be argued that such labelling is merely a political affair and that it might tempt consumers into

unnecessary consumption, which in turn could do more damage to the environment than not purchasing the products (2011).

2.1.3 The Plant-based Food Industry

Because of livestock products being the largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, the plant-based food industry has become an increasing contribution to the sustainable development (Division for Sustainable Development Goals, “Flexitarianism”, n.d).

A plant-based diet is a diet that excludes all animal products, including red meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy products (Ostfeld 2017). The global expansion of such diets can be due to various factors. Individuals might seek to avoid eating animal-based products due to ethical or weight-management reasons. One of the biggest motivations, however, is environmental concerns (Jones 2020).

At the current moment, agriculture plays a partial role in the global environmental issues debate, such as climate change, land degradation, water pollution as well as

biodiversity loss (Gerber et al 2013). Animal-based products are said to account for 60% of global food-related emissions, and three-quarters of the land used for food production, whilst only yielding 18% of our globally consumed calories (Poore & Nemecek 2018).

The adaption of a wholly plant-based diet can be argued to be an expression of political views and identities, as individuals take part in the reforming of the modern food production by avoiding animal-based products (Boström & Klintman 2011).

Since plant-based diets are increasing throughout the entire world (Jones 2020; Frangoul 2020), it creates opportunities for food production companies to produce products that meet the consumers’ demands.

Oatly

Because Oat milk sales have been exploding in the last couple of years, the international, Swedish based brand Oatly has become a category leader with the distribution of products in more than 20 countries around Europe and Asia ("How Oatly became the oat milk brand to beat" 2020).

Their products are 100% plant-based and their goal is to deliver “products that have maximum nutritional value and minimal environmental impact” ("The Oatly Way: Oatly: the Original Oat Drink Company" n.d).

Oatly have been criticized for their controversial marketing campaigns, as they have been vilifying the dairy industry as the thieves of the global environmental degradation. A huge part of the agricultural business considers Oatly to be hypocrites, as farmers argue that they are losing their jobs in step with Oatly growing bigger and bigger (Woodford & Trimble 2019). However, no matter the backlash, Oatly continues to expand rapidly with an almost 500% increase in sales in the last few years (Quilt 2020).

2.2 Theoretical and Methodological Background

2.2.1 Advertising as discourse

It can be argued that media discourses such as advertising can help shape the public understanding of environmental issues and thus construct a discourse surrounding sustainability that will brand the given company as the “most sustainable” or “more sustainable” choice.

Advertising as discourse is based on assumptions that advertisements are produced with intentions of persuading the consumer to purchase the given product, or to present the same product as desirable as possible to the consumer (Karlsson 2015).

Adverts can be distinguished by various categorizations, as proposed by Cook (2001). These are ‘hard-sell’ and ‘soft-sell’ ads, whereas hard selling “makes a direct appeal”

(2001:15) and soft selling acts more on letting the consumer know that life will be better with the product. Cook classifies two techniques, called ‘reason’- and ‘tickle’ ads. The reason ads motivate purchase, whilst tickle ads simply appeal to “emotion, humour and mood”

(2001:15).

Angela Goddard (1998) claims that advertisements are short-lived but contain longstanding effects that leave messages about the culture that produced them. She argues that these messages function as a reflection of values of the powerful groups in society who produced the text, and thus proposes that advertisements are a “powerful contribution to how we construct our identities” (1998:3). She asserts that advertising problematizes aspects of life which can be solved through a product and that adverts do not have to be aiming to sell us anything but are intentionally used to sell ideas in order to benefit the advertiser (1998).

Fairclough agrees, as he views the language of advertising as one of the most pervasive modern discourse types (1989). He examines the ideological stem behind

advertisements and outlines three elements of approach: the building of images, relations and consumers. He proposes that adverts must establish some sort of image of the product by approaching them as available to the targeted consumer. In this section, the brand name plays a partial role. Effective brands must create a notion of their brand-name and products as something good, and something the consumers want to be associated with (O’Shaugnessy & O’Shaugnessy 2004). For companies that want to reach customers globally, a strong brand name is therefore essential (Belch & Belch 2001). Another technique of building the image of a product is by carefully chosen vocabulary (Fairclough 1989), as language is sensibly

chosen to construe a reality and to imply blame or innocence (Strauss & Feiz 2014). The advert must establish trust with its audience and build a relation (Fairclough 1989). So, to communicate effectively with customers, producers must understand who their target audience is. But also, what they know about the company’s product and how to communicate with them to influence their decision-making process (Belch & Belch 2001). The source needs to be credible for the consumer to be persuaded, which is achieved when the audience can trust in the communicator’s knowledge (Kelman 1961). For information to be understood as truth by the audience, the advertiser must thus emphasize the certainty of the information. This can be accomplished by applying linguistic elements that emphasizes the certainty of the information (Delin 2000). Fairclough (1989) also points out that adverts construct the nature of the audience, for example by presupposing that they have certain knowledge and beliefs or by implying that they should have.

The attractiveness of the source is vital, which means that the audience wants the advertiser to be similar and familiar (Kelman 1961). By persuasion through a process of identification, the receiver is motivated to seek some type of relationship with the source and thus adopts similar beliefs, attitudes, preferences, or behaviour (Belch & Belch 2001). This relationship can be built up through direct addressing. By using the personal pronoun “you” to address the customer, advertisers suggest intimacy and shortens the distance between themselves and the consumers (Fairclough 1994: Cook 2001).

To persuade the targeted audience into consumption, many advertisers take advantage of “buzzwords”. Such terms suggest a kind of electrical charge as a result of making a

connection, a motive for making their product desirable and a ‘must’ to buy (Goddard 1998). Buzzwords frequently consider topics that are thought important at the time, which might make individuals feel obliged to purchase the product (1998). In an age concerned with pollution, phrases such as “kinder to the environment” are likely to be received

sympathetically. People’s concern about the artificial nature of food is met by expressions such as “fewer additives” etc. (1998). Buzzwords can also be used at the basis of comparison, by portraying the chosen product with positive references. This branding thus creates a notion of the other product as not being as good (1998). Imperatives can also work as a persuasion technique for tempting the consumer into consumption, since they create the effect of advice coming from an unseen authoritative source (Danesi 2015).

The observations outlined in this section illustrate how advertisements work to persuade the audience into consumption. To understand how public understandings are mediated through advertisements and how adverts reveal assumptions of the given discourse, the following section on Critical Discourse Analysis has been utilized.

2.2.1 Critical Discourse Analysis

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is an approach within linguistics to analyse the

interconnectedness of discourse, power, ideology, and social structure (Simpson et. al 2019). The concept of discourse, when speaking in terms of CDA, is the broader ideas

communicated by a text (Van Dijk 1993; Fairclough 2000; Wodak 2001). Our everyday experiences are constituted, communicated, and mediated by discourse, whether it is by texting a friend, immersing in politics by reading a newspaper, or simply by looking at advertisements and product packaging (Strauss & Feiz 2014). Textual and visual content can thus be studied to see how they categorize people, the events and the social context where the

text takes action. It can also be studied to reveal what kind of events and persons that are foregrounded, and which are backgrounded (Machin & Mayr 2012).

One widely used approach within CDA is Fairclough’s three-dimensional model for analysing discourse (1989, 1995). It is a framework used to examine power structures in language as written or spoken, for example by the use of vocabulary, grammar, and cohesion (Simpson et al., 2019). Fairclough’s CDA model investigates the textual process of

production, the process of interpretation, and the social conditions of production and

interpretation (Fairclough 1989). In the first stage, the textual analysis, the formal properties of the text are examined. Here an investigation of linguistic features is done, by examining vocabulary, grammar, and various forms of speech acts (1989). This can be done by looking at individual items such as adverbs, pronouns of addressing, as well as metaphors and other items of figurative language (Strauss & Feiz 2014). The second step, the discursive, or the interpretation level, is concerned with the relationship between the text and the interaction, as it sees the text as a product of its production (Fairclough 1989). It is the relationship between the linguistic and semiotic messages from the textual analysis that might reveal messages of various power structures (Strauss & Feiz 2014). The social practice, the explanation,

examines the relationship between the production and the social context: how the social determination of the processes of production affects the social context. This stage portrays a particular discourse as a part of a social practice and seeks to show how this practice is determined by social structures (Fairclough 1989) and reveals the assumption of what is seen as normal and correct versus what is not in society (Strauss & Feiz 2014).

2.2.2 AIDA as a conceptual framework

To understand how marketing and advertising communication works, and how global brands expand so rapidly, analysts have been offering various hierarchy-of-effect (HOE) models throughout the years. These models are based on a concept of logical events leading to sales (Cramphorn 2006). One of the most influential models is AIDA, its name being an acronym for Attention, Interest, Desire, and Action (2006).

To easier understand the discourse of advertising, and to examine the linguistic character of social and cultural structures with CDA, the conceptual framework AIDA can be applied as a tool for structure. Although the model might be argued to be oversimplified (Blythe 2006) it can still be used as a useful guide to a variety of communication types. In

combination with CDA, both help analysing the interconnectedness of discourse, power, ideology, and social structure.

The first stage, Attention or Awareness, is where the consumer comes across the brand, by for example an advertisement. Here the advertiser must capture the targeted viewer’s attention immediately, or the consumer might be lost for good (Priyanka 2013). Interest is the stage where the customers' interest in the product needs to be aroused. This section should use emotions to persuade the targeted consumer into believing that the purchase of this product will solve their problems, or simply ease their everyday lifestyle (2013). The third step, Desire, is achieved when the costumer’s desire is aroused by the product. This step is where the advertiser must persuade the consumer into desiring the product, by providing clear examples of the advantages of the company’s product, whilst taking the lifestyle of the targeted customer into account (2013). Action, the last step, is where the desire into a product or service has been aroused, and now the producer/advertiser must convince the costumer into completing a purchase (2013).

2.3 Previous works

Many previous studies addresses advertisements that approach discourses of environmental issues, such as “It’s not easy being green” (Budinsky & Bryant 2013), a multimodal critical discourse analysis on television advertising. This study offers a creditable insight into

environmental discourse in advertising since they argue that major corporations accompanied by big media are leading individuals’ attention away from necessary needs and replacing it with what they call “green consumerism” (2013). They mean that by purchasing a product that is claimed to be beneficial for the environment, the action still operates within a capitalist context that is more concerned with profit for the company than the actual environmental benefits. Although their examination uses adverts that focus on chemical cleaners and vehicles, which can be argued to be more harmful to the environment than oat-products production, it still offers a valuable method of critically observing advertisements. The study uses Huckin’s (1997) approach to CDA, and although the present study uses Fairclough’s variation, it still studies the adverts similarly. Akin to their study, the present study will identify the genre (advertising), how the context of the text is presented as well as examine the language used in the text.

Other, similar studies approach the advertising and marketing of Oatly. Ledin and Machin (2019) uses a Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis and Social Semiotics

approach, and reviews both packaging and various campaigns. The present study will, however, be a more concentrated one, examining the discourse of advertising on the product descriptions on Oatly’s website in comparison with in-store packaging. Similar to Ledin and Machin’s study, this paper studies the social context in which the advertisements take place, as well as it investigates the language used in the adverts.

The AIDA model has been applied in a variety of different advertising and marketing studies. One of these is a neural network analysis of advertising effectiveness for renewable energy technologies by Sharifi et.al’s (2019). They successfully use the model to reveal that the attention towards the advertising activities will lead to an increased adoption of these technologies. Akin to their study, this study uses theories of advertising effectiveness to understand how efficient adverts can increase the consumption of given products or services. Sharifi et.al’s (2019) study argues that by providing customers with necessary information about the advantages of a product, the decision-making choices of the consumer will be affected.

3. Design of Study

The present study aims to investigate the discourse on sustainability and how it is approached with various advertising strategies in Oatly’s advertisements by a qualitative study on product descriptions on their website, as well as on packaging in-store.

3.1 Data and material

In an attempt to reveal the underlying social apprehension of the discourse on sustainability in advertising discourse, the plant-based food production company Oatly has been studied. This is primarily due to their rise in sales during the last couple of years (Quilt 2020), and their products being available in almost every Swedish supermarket.

3.1.1 Material

The material for this study is collected from Oatly’s official website and their products that are available in the big Swedish supermarket chains. Both will respectively be compared and discussed in this study. At the moment of writing this paper, Oatly has a total of 38 different products for sale varying from drinks to ice cream. This study will be examining one product of each section as listed on their official website, i.e. Oat Drink, On the Go, Oatgurt,

Cooking, and Ice Cream. The examination will thus use the product that is listed first to the

far left in each section on Oatly’s website, i.e Whole/Deluxe Oat Drink, Chocolate on The

Go, Havregurt Natural, iMat Cooking Cream and Chocolate Ice-cream.

The selection of data is based on the first product to the far left being the most eye-catching one, grounded on the assumption that the targeted viewer will be able to digest information quickly once images and graphics are placed towards the left (Alter & Oppenheimer 2009). This increases the processing fluency and facilitates the digestion of media and information for the targeted reader (2009).

3.2 Method

The main goal of this study was to examine how Oatly approaches the discourse of

environmental sustainability in their advertisements by persuasive advertising strategies. The study sought to understand the discourse surrounding environmental sustainability, and how Oatly as a company constructs a public understanding of the issue.

The study has used various advertising strategies, combined with AIDA as a

theoretical framework to analyse various rhetorical techniques for persuasion, such as choice of vocabulary. To study the use of language and how it links to a broader societal concern Fairclough’s three-dimensional model (1989, 1995) has been utilized.

The study has examined the method Oatly uses to approach the discourse on sustainability, as well as sought to comprehend how they depict social determinations.

4. Results & Discussion

To answer my proposed research questions, the analysis and discussion will be divided into an examination of the product description on the website, as well as the products in-store. The two examinations will be compared in a separate section in the end.

4.1 Textual analysis

Textual content can express concepts and ideas as it serves as a communicative mechanism for structures, concepts, and choice. Language is carefully chosen to construe reality and to imply blame or innocence (Strauss & Feiz 2014). Thus, this part of the examination will investigate the textual content of the advertisements. The sections will be divided into different subsections, following the AIDA framework, to look for various strategies used by Oatly to persuade the consumer in the following steps: Attention, Interest, Desire, and

Action. Furthermore, to facilitate reading, further headlines such as modes of addressing and choice of vocabulary will be applied.

4.1.1 Product descriptions on website

This section will seek to examine product descriptions of five products in total. The data in this section is collected from Oatly’s official website (https://www.oatly.com/int/).

Attention/Awareness

In this stage, Oatly must capture the targeted viewers’ attention immediately to make them aware of their product (Priyanka 2013). To achieve this, various attention-seeking devices must be applied.

Brand logo

Since a strong brand name is essential for companies that want to reach customers globally (Belch & Belch 2001), Oatly tries to emphasize their brand by marketing themselves as original. This statement is used since they want to reach customers not only in Sweden where they are established, but also expand their sales worldwide.

The logo consists of capital letters, stating the ingredient the product is fabricated of: Oat, accompanied with the suffix -ly and an exclamation mark. The logo is placed on the top of each product, occupying a third of the packaging, except the ice-cream packaging (see Figure 5) where it occupies 2/3.

Slogans and labels

To attain and sustain the consumer’s attention, Oatly must persuade them into believing that their products are beneficial. It can be argued that Oatly already has identified their target audience as being people who are aware of and wanting to improve the environment by using various products that contribute to less global emissions (Gerber et al., 2013). Thus, to

approach this audience, Oatly uses positive evaluation of their products with vocabulary, slogans and labels that regularly relates to their beliefs.

Goddard argues that slogans “uses the idea of the kind of permanent marker or identifying sign that distinguishes a whole company” (1998:105), and that the best slogan is the one that gives useful information about the product as well as attract consumers at the very sight. On the lid of the ice-cream package (see Figure 5) the slogan “Wow, no cow!” is written. This is a comparative reference that portrays Oatly’s products as better than dairy products because it contains ‘no cow’. Similar positive attributes can be seen on each product packaging on the website:

(1) Oatdrink Deluxe (see Figure 1): Amount of CO2 per kg. (2) Chocolate Drink (see Figure 2): “Powered by oats”.

(3) The Oatgurt Natural (see Figure 3) and Chocolate Ice-cream (see Figure 5): “Totally vegan”.

(4) iMat Cooking Cream (see Figure 4): “100% plant-based”.

Labels or slogans like these claims in various ways that they are advantageous for various reasons. Due to social perceptions, words like “plant-based” (see Figure 4) and “vegan” (Figure 3 and 5) associates with positive factors, because such alternatives being the better choice in terms of environmental sustainability (Baldwin 2015). Since these words are the counterpart of “dairy” and “omnivore”, it characterises the comparative form as the damaging choice (Goddard 1998). Once a consumer chooses plant-based products over dairy products it can be argued that they are expressing their political views and identities. This is because they play part in the reforming of the modern food production by avoiding dairy products. (Boström & Klintman 2011).

Humour, sarcasm and informal language

Advertisers need to set up an intimate relationship between themselves and the consumers to be able to persuade, which can be accomplished by using language that creates an illusion of intimacy. A way to attract consumers and to make them aware of the brand is by adverts containing humour, sarcasm and informal language (Danesi 2015). Throughout the product descriptions on the website, there are humorous messages, such as visible in example (5):

(5) If you use this super delicious oat drink when you bake, your muffins, cakes, and breads will come out so moist that it may not even bother you when people use the word “moist” (Oat Drink Deluxe)

Humorous elements like that of example (5) enhance effectiveness and attract the consumer’s attention by increasing their liking of the ad and their affection towards the product and brand. But it can also easily distract the audience from arguing against the message (Belch & Belch 2001). Humour can also be expressed to communicate an idea fast and vividly by the use of similes, see example (6) and (7):

(6) It swims around the cup so naturally, like a dolphin in the ocean that just escaped from a zoo. (Oat Drink Deluxe)

(7) Oats, water, a pinch of salt and rapeseed oil — all smoother than a velvet sofa. (Oat Drink Deluxe)

As well as by the use of sarcasm combined with idioms, such as seen in example (8):

(8) If you’ve lived under a rock your whole life up until five seconds ago when you clicked on this page, we’d like to inform you that this ice cream does not contain any dairy. (Chocolate Ice-Cream)

Due to the use of humour and sarcasm throughout Oatly’s various product descriptions, they create a perception of who they are as a company: an identity that is more equal to that of the consumer. The targeted reader’s interest will thus be obtained by the use of a conversational, familiar, and informal language.

Positive evaluation: Adverbs and adjectives

Humour combined with conversational and informal language is not the only way to draw attention to textual content. As seen in the above examples: (5-8), the choice of vocabulary also plays a partial role because it helps to build the image of a product (Fairclough 1989).

One feature of vocabulary that Oatly frequently uses are adverbs and gradable adjectives, to describe and sometimes exaggerate the advantages of their products. In

to describe the taste of Oat Drink Deluxe. Both words lack any scientific research reference, making them inconsequential. However, it operates as an attention-seeking device, since this kind of vocabulary have been warily chosen to promote positive associations in the mind of the targeted reader. This use of adverbs and adjectives is also present in example (8), where they illustrate the way oat milk behaves in a glass, with the intensifying adverb “so” and the accompanying adverb “naturally”.

Oatly also uses gradable adjectives to point out, with the help of superlative

adjectives, that their products are the “best”. In example (9) they use the superlative adjective “best”, instead of the absolute “good” or the comparative “better”, to evoke a positive

association of their product.

(9) So only the best is good enough, huh? (Oat Drink Deluxe)

By using the superlative of “good”, they claim that their product is unquestionably the

foremost product of milk alternatives on the market. This once again generates an impression of other alternatives as less “good” (Goddard 1998).

Direct addressing and interrogation

Direct addressing is a technique for the advertiser to establish relations, as well as it suggests intimacy and shortens the distance between themselves and the consumers (Fairclough 1994; Cook 2001). When the advertiser is persuading the audience with this method of

identification, the relationship between the two parts become more or less equal, and the advertiser becomes more attractive and credible to the audience (Kelman 1961).

It is also possible to involve the reader in a conversational and equal relationship by using imperatives and interrogatives. To engage the consumer rather than to simply convey information, the advertiser can address the reader directly and include questions that might engage him or her (Delin 2000).

Example (10) uses attention-seeking verbal language that engages the consumer by targeting him or her with a carefully worded question at the start of the advertisement (Goddard 1998). It starts with a rhetorical question and presumes the habits of the consumer in the answer:

(10) What do you think about that line? You are probably unconvinced (…)

(11) A bunch of friends or family members all sit down to dinner. One is lactose intolerant, two are vegetarian, one is vegan, one loves meat and the other doesn’t want anything to do with anything that comes from a cow. What do you do, make four different dishes?

In example (10) and (11) the pronoun “you” is used to show that they are addressing the targeted consumer individually. Not only is this way of making the consumer feel involved, but also a way for the advertisers to raise a problem in the addressee’s mind, which can then be solved by the means of a product (Goddard 1998). Oatly does this in example (11), where they create a problem: a family gathering where the different members are either allergic, plant-based, or omnivore, and all need to be fed. Instead of making a different dish for each diet, which is the problem, Oatly offers the solution in means by their product.

Interest

Interest is the part of AIDA where Oatly must focus on building the consumer’s interest (Priyanka 2013). This section should act on emotions, as well as introducing the benefits of the products and how it will fit the lifestyle of the consumer.

Choice of vocabulary, Positive Evaluation and Presupposition

Oatly manages to persuade their audience by writing in a style that feels similar and familiar to that of the consumers. The choice of words can reflect the advertiser’s evaluation of a product, which shows their attitudes and bias. Thereby the advertisers can imply their

positive and negative values regarding what is good and bad (Fairclough 1994). Oatly already supposes that their target audience is plant-based or enough environmentally conscious to adopt a more plant-based lifestyle, and thus proposes that their product is (see example (12):

(12) The obvious choice when you want to swap whole cow’s milk for

something good for the planet. (Oat Drink Deluxe)

Oatly presupposes that their audience is in a certain way and wants certain things, which is a method called presupposition. It is the use of linguistic forms that imply the existence of

something or some fact (Delin 2000). This is done with linguistic elements that emphasizes the certainty of the information, such as definite expressions (2000). In the noun phrase in example (12) Oatly uses the definite article “the” before the adjective “obvious” to stress the fact that their product is the one you want to purchase if you were to switch your dairy milk to a substitute. The phrase thereafter, “something good for the planet”, denotes that dairy milk is not as good for the planet as oat milk is, and once again, Oatly is vilifying the dairy industry as an unsustainable alternative.

Credibility

Oatly persuades the addressee’s interest by improving their credibility as they make the audience believe that they are reliable and have knowledge in their area of the subject

(Kelman 1961). Oatly supports this by repeatedly providing the consumer with advantages of their products, as well as providing scientific references to prove the truth of their statements. Using facts supported by scientific references to enhance the benefits of their products can be seen in The Oat Drink Deluxe:

(13) Actually, Oat drink Whole has lots of healthy unsaturated fat*. *Replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats in your daily diet contributes to maintaining a recommended cholesterol level.

The use of positive adjectives like “healthy” in example (13) implies positive components of their products that might not be found in other products. In example (13) Oatly also

problematises aspects of life that can be solved by their product, by stating that the replacement of saturated fats with unsaturated fats will contribute to a maintaining of a recommended cholesterol level. Not only do Oatly provide their facts with support from scientific references, but they also act on their credibility as a company:

(14) What you think about it, on the other hand, is the big question unless you’ve already tried our chocolate oat drink because then it’s highly likely that you love it as much as we do. * *Pure chance without a statistical survey of how many people like chocolate oat drink. (Chocolate Drink)

In example (14) they build up credibility in their statement by acting on trust. Even though they do not provide any scientific support that reinforces the product to be likeable, they

assume that the consumer will like it because they say so. This is accomplished by using embellishing adjectives: instead of using the adjective “like”, they use “love”, as if to emphasize the flavour.

Another method of enhancing the credibility of the source is by using a spokesperson in the firm’s advertising (Belch & Belch 2001). This strategy is used frequently by Oatly for example on the Chocolate Drink, see example (15) and on The Oat Drink Deluxe, see example (16):

(15) Our product manager would like us to write “it’s an amazing chocolate oat drink” here. But you probably already know we think it’s great,

otherwise, we wouldn’t have added it to our Oatly lineup.

(16) Anna says it is just about perfect.

Desire

To turn the consumers' interest into desire, Oatly must create a strong motivation for purchasing their products. This can only be achieved if the adverts have used the right appeals (Priyanka 2013).

Comparative reference: Buzzwords, adjectives, adverbs

Oatly uses comparative references throughout their product descriptions, as seen below:

(17) Healthy unsaturated fat (Oat Drink Deluxe)

(18) Maintaining a recommended cholesterol level (Oat Drink Deluxe) (19) Extra protein (Oatgurt Natural)

(20) Healthy lifestyle (Oatgurt Natural)

These are used to create a stronger liking for the products, because they are words that usually occur as the basis for comparison. Comparative references are strongly connected with the product’s quality that makes it a ‘must’ to buy (Goddard 1998). Comparative references are also used to create a sense of that the company’s products are more beneficial than their rivals, which is visible in example (21) and (22):

(21) Plant-based ice cream is just as good as ordinary ice cream. And by "just as" we mean "equally" or "more”. (Chocolate Ice-cream)

(22) It’s the obvious choice when you want to swap whole cow’s milk for something good for the planet. (Oat Drink Deluxe)

In example (21) Oatly portrays their product as the better choice in terms of taste, by

gradually describing the flavour, as if to convince the reader. If the taste is “just as good” that is good enough for making a purchase, but if the flavour is better, a sense of desire for the product is aroused. In example (22) Oatly stirs the consumer’s desire by portraying their products as “the obvious choice”.

Oatly also establishes a desire for the product by the use of predications such as adverbs and adjectives to describe the advantages of the products. This helps the consumer believe in the product. Predicates conveys the good features of products and might inevitably also reflect ideological values (Fairclough 1994). The selection of this positive vocabulary “draws upon a set of systems of meaning that provide many alternative ways of saying the same thing” (Delin 2000:132).

Oatly uses adverbs followed by adjectives with positive connotations to

persuade their consumers by creating an image of their product as being the best. This is seen throughout the product descriptions on the website, as a means of maintaining the desire for the products, see example (23), (24) and (25):

(23) super delicious, really great, perfectly creamy. (Oat Drink Whole) (24) pretty awesome, so good. (Oatgurt)

(25) super easy, absolute minimum. (Creamy Oat)

Action

Establishing a relationship between the advertiser and the addressee is not the only crucial part of the strategy of persuading consumers. It might work in the latter parts, to raise awareness, capture interest and arouse desire, but for the consumer to purchase the product- they must feel like they need it. The motive for this can be expressed through so-called “reason ads” which suggest a motive or reason for purchase (Cook 2001) and encourages the

consumer to act quickly.

Imperatives

Oatly frequently uses the persuasive technique of imperatives, since these can work as a strategy to encourage the consumer to complete the purchase (Danesi 2015). An example of this is in the product description of iMat, see example (26):

(26) Try this product. Just take it home and whip up something for your family.

Don’t tell them that you swapped the old cream for iMat. We are pretty sure that they will not be able to tell the difference.

Oatly are indicating that their product works as well as dairy cream by using the imperative phrase “Just take it home”, which leaves the audience with little room for argument. Another example where they address the audience directly and encourages them to act immediately, is on the Chocolate Ice-cream product description, see example (27):

(27) We recommend trying our chocolate ice cream immediately because you might be surprised how perfect the name of this product really is.

The use of the verb “recommend” at first implies a notion of slow purchase, but afterward, they use the conjunction “immediately”, which contradicts the former. It suggests a quick action of purchase, to ensure that they are not missing out on anything. Oatly creates the effect of advice coming from an unseen authoritative source, by using the pronoun “we” as they approach the customer.

The mode of convincing for action also works when they encourage consumers that already have tried their product to continue, by providing them an upgrade of the product. This is done in the product description of the Oatgurt, with a line stating in capital letters “Updated recipe! Omg! Say hi to Oatgurt Natural 2.0!”. They describe the product as already being a favorite but stating that even these favorites can need some improvement. They let the reader know that they, see example (28):

(28) Increased the acidity a little, removed the flavoring, added a special salt to round out the flavor and some extra protein too, all while making it even whiter and creamier.

This is a strategy used to create a sense of necessity to try this new, upgraded version.

4.1.2 Packaging in-store

This examination will seek to find what linguistic persuasion techniques Oatly uses on their packaging in-store.

Attention

As discussed on 4.1.1 Product descriptions on website, the audience’s attention will be caught by striking and engaging textual content.

Direct addressing

Oatly is not afraid of addressing the target reader directly, which suggests a relationship between the addresser and addressee that is equal (Fairclough 1989). This technique is visible on the packaging of Oat Drink Deluxe (see Figure 6), where they state, “You are one of us now”. This simple statement, with assistance of the personal pronouns “you” and “us”, can be argued to work as an “implicit authority claim” (Fairclough 1989:128), as Oatly portrays the community “us” (i.e the plant-based community) as an aspiration.

Logo and Slogans

Since a strong brand name is important, each product’s packaging contains Oatly’s logo. It is apparent that Oatly wants their logo to be well-known and trusted, since today’s consumers have a tremendous number of choices available in nearly every product category but have less time to make selections (Belch & Belch 2001). Thus, a well-known brand name simplifies the decision-making process for the consumers (2001). A recurring slogan that captures the targeted consumer on the various products is “Wow, no cow!” (see Figure 7). It identifies their product as the “good” choice because products containing cow (dairy) are not as “good”. With this statement, they are indicating that they are superior to the milk-industry.

Figure 7 Figure 6

Interest

When the attention and awareness have been attained, Oatly must seek to preserve the audience’s interest for the chosen product or brand.

Vocabulary and slogans

Since vocabulary is a central element in building the image of a product

(Fairclough 1989) it is vital for keeping the target consumer’s interest. By now, once the targeted person is holding the physical product in their hands and reads through the text, the company must maintain interest for the purchase to be finalized. This can be achieved by carefully worded vocabulary and slogans. A slogan Oatly uses repeatedly is “Post Milk Generation” (see Figure 8). By this three-word slogan, we already get the sense that the previous generation has been a generation of dairy-milk lovers and that there is a revolution coming up, which encourages the contemporary generation to turn into a plant-based one. This

statement exposes the previous generation as something bad, since the contemporary generation is “post” it. In the packaging of Oatgurt Natural (see Figure 8) Oatly gives the reader an introduction to what this movement is about. They describe it as; see example (29):

(29) A non-profit mindset that works to inform the public about the health andsustainability advantages of plant-based diet.

In example (29) Oatly relies on their consumers’ trust in the brand instead of providing scientific references to their statement. The reader is encouraged to cut out a temporary membership card from the carton and take it with them wherever they go. So not only is Oatly a company, but also a movement in which they encourage their consumers to join. The packaging of Oatgurt Natural, therefore, can be argued to work as a ‘reason ad’, because it suggests a motive or reason for purchase (Cook 2001). Not only on the packaging of Oatgurt

Natural does Oatly encourage the targeted consumer, but this technique is also similarly used

on the packaging Creamy Oat. The addressee is encouraged to cut out letters from the

cardboard that says, “Eat More Plants”, since the action of this might cause “a minor revolution” (see Figure 9):

On the other side of the package (see Figure 10): they address the reader with “Hey Oat Punk”. They encourage the reader to drink their oats and “then cut out the stencil on the side of this carton and create your own political piece of art” (see Figure 10). By this simple statement, they presume that the act of eating more plants is co-related with a political

movement that aims for change. This persuasion technique creates a relationship between the producer and consumer that is more than merely consuming and producing.

On the packaging of Oat Milk Deluxe (see Figure 11) they build up the credibility of the company by letting the reader now that they label their products with the amount of co2 they generate: “so that you know how they impact the planet before you decide to buy them. That way you can easily compare them to other food products” (see Figure 11). So, because consumers today have a tremendous number of choices available for food products(Belch & Belch 2001), these simple labels can simplify the decision of purchase for the consumers.

Desire

There is a difference between wanting something and desiring it. To convert the targeted consumer’s interest into a strong desire, Oatly must establish motivations to generate the need for purchasing the product.

Slogans/buzz words

To turn the interest into desire, Oatly uses slogans, or buzzwords that labels the product as plant-based, such as:

(30) “No milk. No soy. No... Eh…Whatever.” (see Figure 12) (31) “Powered by Oats” (see Figure 13)

Figure 10 Figure 11 Figure 9

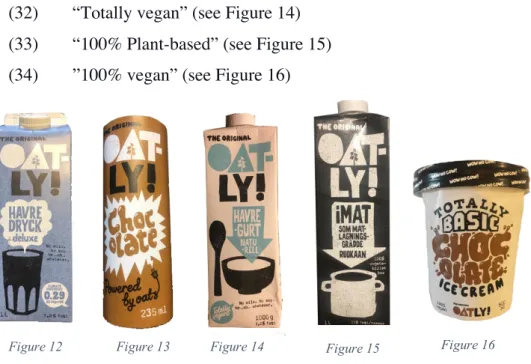

(32) “Totally vegan” (see Figure 14) (33) “100% Plant-based” (see Figure 15) (34) ”100% vegan” (see Figure 16)

Because most consumers are aware of the fact that the dominant source of environmental degradation by food supply is agricultural production (Baldwin 2015), many individuals feel obliged to purchase products with buzzwords like these because they consider topics that are thought important at the current time (Goddard 1998).

Action

This part of the examination investigates how Oatly convinces their audience for the final purchase. The textual content on the packaging of the various products is quite long, so it can be argued that they are imposed to be read once they have been purchased. However, the addressee still needs to be persuaded by the product produced by Oatly, instead of choosing other similar products on the store shelf.

Once again, the buzz words (Goddard 1998) plays a partial role. By providing the predicted consumer with content stating that the product is plant-based and environmentally friendly, it not only arouses desire, but also immediate action for the person with an already plant-based lifestyle. The choice is simple, instead of spending time reading through the ingredients. A further motive for purchase is that of identification. If the consumer has a variety of products in front of them, they might simply go for that one brand they acknowledge (Belch & Belch 2001). Due to the Oatly logo being positioned on top and occupying 1/3 of the packaging, it is absorbed quickly, and the targeted consumer might pick the product up in a rush simply because the brand name is familiar.

Figure 15 Figure 14

Figure 13

4.2 Comparison of advertising strategies on the two platforms

It could be argued that by the product descriptions on Oatly’s website, the company works on creating an interest and desire for the product by catching the addressee’s interest, in the words of Cook (2001) called ‘reason’ ads, because they suggest a motive or reason for purchase (2001). The products in-store work as soft-sell ads, because they are less immediate and less urgent (Simpson et al. 2019). Since they offer the potential customer time to read through the packaging, with information based on benefits with plant-based foods in a more general sense, it works as long-copy adverts (Cook 2001).

Humour as a persuasion technique is used more frequently on their website than on the packaging. This might be because Oatly needs to persuade the consumer before he/she reaches the store. Once in the store, the consumer presumably would like to purchase a product from a brand they know and trust. At this point, the logotype plays a partial role, because a well-known brand name simplifies the decision-making process for the consumers (Belch & Belch 2001). Thereby the significance of allowing their logo to occupy 1/3 of each packaging. If the targeted consumer is in a hurry and is searching for a product that suits their needs, they will turn to a brand they have heard of before and confides in.

Oatly does not describe the benefits of the particular products on the packaging in-store as much as they do on the product descriptions on the website. They rather supply the addressee with catchy and stirring texts such as those of Figure 6, 8, 10 and 11 where they portray their products as beneficial for the environment.

There is unquestionably more textual content on the product descriptions on the website compared to the packaging, which makes it challenging to contribute with a proper conclusion of comparison. However, from the findings, it can be argued that Oatly addresses the aimed consumer with more personal addressing and elements of humour on the website, whilst including more slogans and buzzwords on the content in-store.

5. Conclusion

The intended aim of this study has primarily been to find ideological values of the sustainability discourse presented in linguistic features on Oatly’s various product advertisements, and how Oatly uses these qualities amongst advertising techniques to persuade their audience. Fairclough’s analytical framework has assisted to distinguish the values embedded in words and grammar, and by comparing tactics between the

advertisements on products on the website to those in-store, this study has revealed the change of slant in persuasion techniques.

The AIDA model has been utilized to reveal how attention-seeking devices seem to be more vital when Oatly markets themselves on the physical product packaging, compared to that on the website. Both segments seem to demonstrate that Oatly acts on present social beliefs and political premises to persuade and engage their consumers. The results of this study have hence been similar to M. Sharifi, et al’s (2019) in terms of marketing

effectiveness. Similar to their study, the application of AIDA has revealed that providing customers with advantages of a given products plays a substantial role in the decision-making, making AIDA an effective tool for persuasion.

This study has shown that Oatly persistently highlights environmental benefits of their products as well as displays their products as the “right” and “sustainable” choice with

various linguistic strategies based on already existing social beliefs and values, whilst vilifying the dairy industry by comparative references, portraying dairy products as an unsustainable alternative. Since it is argued that individuals express their political views through consumption (Boström & Klintman 2011), Oatly manages to persuade their audience by acting on already existing social understandings of the discourse surrounding

environmental sustainability, such as labelling their products as “vegan” or “plant-based”. Although they use statistics and numbers that are scientifically based to some extent, it can still be argued that they are merely the “lesser of two evils”- because they advertise products that are not necessities, and thus encourages unnecessary consumerism. As Ledin and Machin (2019) argue in their study, there lies a danger in large businesses approaching discourses such as sustainability, because they can unconsciously pull us in the wrong direction, i.e. consume more unnecessary commodities. However, as Budinsky and Bryant (2013) argue, this kind of consumerism is in itself not destructive, because there are still some products human beings simply cannot live without. There is a need for balance

nonetheless, whereas sustainable products combined with reduced overall consumption will result in the “real” sustainable development.

It is important to note that the findings in this study cannot provide an objective claim about Oatly’s approach on the sustainability discourse in their advertisements, due to limited data. However, the findings are still sufficient enough to make general speculations, and the conclusion can serve as an interesting area for further research. Thus, to make a claim about a corporation, Oatly in this case, it is important to consider a deeper and more detailed analysis. A suggestion for future studies is hence to collect more advertisements and examine

additional linguistic examples visible in these. Another suggestion is to make a survey method research, where questionnaires are handed out to receive opinions from consumers that purchase Oatly’s products. This would be particularly interesting since it might offer a valuable insight into how individuals perceive “sustainable consumerism”.

References

About Oatly: Oatly: The Original Oat Drink Company. (n.d.). Retrieved March 23, 2020, from

https://www.oatly.com/int/about-oatly

Baldwin, C. (2015). The 10 principles of food industry sustainability. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: WILEY Blackwell.

Belch, G.E. and Belch, M.A. (2001) Advertising and Promotion-An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective (5th Ed), New York: Irwin/McGraw Hill.

Blythe, J. (2006). Essentials of marketing communications (3rd ed.). Harlow: FT Prentice Hall. Boström, M. & Klintman, M (2011). M. Eco-Standards, Product Labelling and Green

Consumerism. Palgrave Macmillan.

Budinsky, J. & Bryant, S (2013). “It’s Not Easy Being Green”: The Greenwashing of

Environmental Discourses in Advertising. Canadian Journal of Communication, 38(2), 207-226. https://doi-org.proxy.mau.se/10.22230/cjc.2013v38n2a2628

Cook, G. (2001). The discourse of advertising. London: Routledge.

Cramphorn, S. (2006). How to use advertising to build brands. International Journal of Market Research, 48(3), 255.

Danesi, M. (2015, April 27). Advertising Discourse. Retrieved from

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/9781118611463.wbielsi137

Delin, J. (2000). The language of everyday life: an introduction. London: Sage publ. Dijk, T. (1993). Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Society, 1(2), 249. Fairclough, N. (1994). Language and power, 2nd ed. Harlow: Longman.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. London: Longman.

Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and Power. London: Longman. FAQ: Oatly: the Original Oat Drink Company. (n.d.). Retrieved from

https://www.oatly.com/int/faq

Flexitarianism: flexible or part-time vegetarianism - United Nations Partnerships for SDGs platform. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/partnership/?p=2252 Frangoul, A. (2020, March 20). Why we may have to change the food we eat to help the planet.

Retrieved from

https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/20/why-we-may-have-to-change-the-food-we-eat-to-help-the-environment.html

Gerber, P.J., Steinfeld, H., Henderson, B., Mottet, A., Opio, C., Dijkman, J., Falcucci, A. & Tempio, G. 2013. Tackling climate change through livestock – A global assessment of

emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome.

Goddard, A. (1998). The language of advertising. London: Routledge.

How Oatly became the oat milk brand to beat. (2020, March 20). Retrieved from

https://adage.com/article/cmo-strategy/how-oatly-became-oat-milk-brand-beat/2245561x Jones, L. (2020, January 2). Veganism: Why are vegan diets on the rise? Retrieved from

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-44488051

Karlsson, Sofia. (2015) Advertising as Discourse. A study of print advertisements published in The New Yorker. Available from Linnæus University.

Kelman, Herbert C. (1961). “Processes of Opinion Change,”. Public Opinion Quarterly, 25(Spring): 57–78

Ledin, P., & Machin, D. (2019.). Replacing actual political activism with ethical shopping: The case of Oatly. DISCOURSE CONTEXT & MEDIA, 34 https://doi

org.proxy.mau.se/10.1016/j.dcm.2019.100344

Machin, D., & Mayr, A. (2015). How to do critical discourse analysis: a multimodal introduction. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Morawicki, R. (2012). Handbook of sustainability for the food sciences. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons.

Oatly, Sustainability Report. (2018). Sustainability Report. Retrieved from

https://www.oatly.com/uploads/attachments/cjzusfwz60efmatqr5w4b6lgd-oatly-sustainability-report-web-2018-eng.pdf

Ostfeld R. J. (2017). Definition of a plant-based diet and overview of this special issue. Journal of geriatric cardiology : JGC, 14(5), 315.

https://doi.org/10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2017.05.008

O'Shaughnessy, J., & O'Shaughnessy, N. J. (2004). Persuasion in advertising. London: Routledge.

PLANT-BASED. In Cambridge English Dictionary. (n.d.). Retrieved March 24, 2020, from

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/plant-based

Priyanka, R., "AIDA Marketing Communication Model: Stimulating a Purchase Decision in the Minds of the Consumers through a Linear Progression of Steps," International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research in Social Management, Vol. 1 , 2013, pp 37-44.

Poore, J, Nemecek, T. (2018, May 31) Reducing food's environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science.

Quilt.AI. (2020, February 27). The Rise and Rise of the Alt-Milk Revolution and What Makes Oatly Stand Out. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@quilt.ai/the-rise-and-rise-of-the-alt-milk-revolution-and-what-makes-oatly-stand-out-5624ebda8154

Ridder, M. (2019, November 18). Oatly: net sales 2012-2018. Retrieved from

https://www.statista.com/statistics/987664/net-sales-of-oatly-ab/

Sharifi, M., Khazaei Pool, J. Jalilvand, M.R., Tabaeeian, R.A., & Ghanbarpour Jooybari, M. (2019) Forecasting of advertising effectiveness for renewable energy technologies: A neural network analysis. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 143, 154

Simpson, P., Mayr, A., & Statham, S. (2019). Language and power: a resource book for students. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Strauss, S. G., & Feiz, P. (2014). Discourse analysis: putting our worlds into words. New York: Routledge.

The Oatly Way: Oatly: the Original Oat Drink Company. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.oatly.com/int/the-oatly-way

Wodak, R. (2001). Critical discourse analysis in postmodern societies. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Woodford, I., & Trimble, J. (2019, September 25). How a promising ad campaign by Swedish Oatly went badly wrong. Retrieved from https://sifted.eu/articles/oatly-ad-campaign-went-wrong/