The immateriality of decay

Exploring (Digital) Decay through Design Fiction

[Thesis Project / Interaction Design Master] [K3 / Malmö University / Sweden]

[Time of Examination / May 28th / 2018] [Supervisor / Susan Kozel]

Abstract

This project explores the qualities of decay and digital decay, with a focus on their immaterial qualities. It then suggests that Design Fiction, when emphasizing the fiction, can address some of this immateriality. It analyzes a specific Design Fiction method, proposing some modifications better suited for the design goals. Lastly, through the altered method, it describes the creation of a Design Fiction narrative.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction...1

1.1 Motivation...1

1.2 Positioning within IxD — Digital Decay and Design Fiction...1

1.3 Research Focus...2

1.4 Expected Contributions...3

2. Decay...4

2.1 Definition...4

2.2 Qualities of Decay...4

2.2.1 Decay through History...4

2.2.2 Decay and Memory...5

2.2.3 The process of decay...5

2.3 Digital Decay...5

2.3.1 Qualities of Digital Decay...6

2.4 Related Work...7

3. Methodology...11

3.1 Definition of Design Fiction...11

3.2 Qualities of Design Fiction...11

3.2.1 Design Fiction and Speculative Design...12

3.3 Design Fiction as Research...12

3.4 Types of Design Fiction...13

3.5 Design Fiction as Anti-Solutionist...13

3.6 Summary...14

3.7 Expected Outcomes...14

3.8 Related Work...14

4. Design Process...16

4.1 Conceptual Exploration...16

4.2 Design Fiction Method...17

4.3 Workshop...19

4.4 Creating the design fiction artifact...21

4.4.1 World building...21

4.4.2 Developing a story...21

4.4.3 Prototyping the artifact...22

4.5 The final movie...23

5. Evaluation and discussion...25

5.1 The Gift from my Parents...25

5.2 Process evaluation...25

5.2.1 Perspectives for Design Fiction...25

5.2.2 Perspectives for Decay, Digital Decay and Memory Studies...26

5.3 The politics in Design Fiction and Decay...26

6. Conclusion...28

7. Acknowledgments...29

8. References...30

9. Media and artworks cited...31

10. Appendix...32

10.1 Stories Developed in the workshop...32

10.2 Timeline developed in the workshop...33

List of Figures

Figure 1: Experiments made revealing different types of digital decay on a photography...7

Figure 2: One of the results posted by Ohlman...8

Figure 3: Current state of the video as in May 20th 2018...9

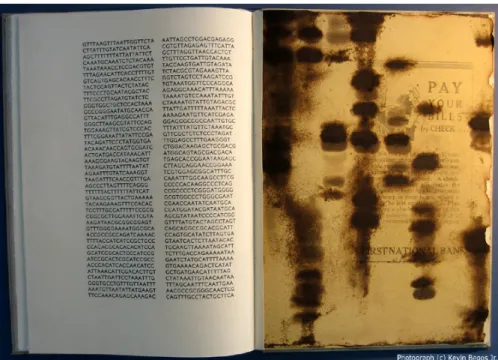

Figure 4: Picture of the Deluxe Edition of Agrippa...9

Figure 5: Encrypted text at the end of the poem...10

Figure 6: Stll of Duas de Cinco showcasing some of the technologies...15

Figure 7: Broken gate with garbage around and abandoned bicycle...16

Figure 8: Damaged car...16

Figure 9: Damaged book and used toothbrush...17

Figure 10: Participants on the walk...19

Figure 11: Participants drawing the timeline...20

Figure 12: A representation of the timeline drawn by the participants...20

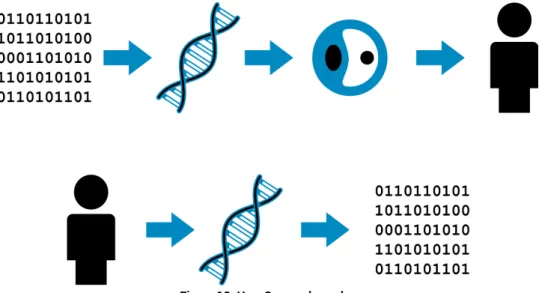

Figure 13: How Genomely works...22

Figure 14: Original image on the left, compared to the retrieved from the bacteria DNA....22

Figure 15 Comparison between different types of footage used...23

Figure 16: The result of image displacement in blocks...24

1.

Introduction

“Like our bodies and like our desires, the

machines we have devised are possessed of a heart which is slowly reduced to embers.”

W.G Sebald, Rings of Saturn, p. 170

1.1 Motivation

One of the themes that the German writer W.G. Sebald was interested in is decay — his sprawling prose uses ruins as an opportunity to explore history, time, memory and identity. And while decay is often regarded as something negative, it can also reveal hidden qualities, such as history or usage. Take for instance a folded piece of paper: the creases reveal exactly how one should fold it again, if needed. Or how shoes are stiff and hard when first bought, but get softer and more comfortable through use. Think of how Paul Dourish (2004) in his text that grounded Embodied Interaction, describes how the “wear and tear” of records cards in hospitals reveal information beyond their written content (p. 20). And while mass produced objects are all identical when created, through their use in different contexts, decay may render them unique. These benefits are of course temporary, because ultimately everything collapses beyond repair. Yet, there is something valuable in both fighting and coming to terms with decay — in the same way that Sebald saw his writing as something worth pursuing, despite the fact that eventually, it will be lost.

When Dourish described the many attributes of a physical record card, he recognized the limitations that a digital equivalent would bring. Even though they would be easier to read and access, they are exempt from the effects of physical manipulation and deterioration. Thus, he argued for computational systems that are not only representational, but participates in the world. But, there’s another way of seeing digital artifacts: while we might perceive them as pristine and immune to the effects of use, this is not entirely accurate. They’re still bound to physical materials and infrastructures, already prone to decay and destruction — just at a different pace and manner.

“Futurists and antiquarians both work with the nature of time. [...]

Because the future is just a kind of past that hasn’t happened yet. And obsolescence is innovation in reverse.”

(Sterling, 2001, p. 11) 1.2 Positioning within IxD — Digital Decay and Design Fiction

When speaking of Interaction Design, one definition is that of the shaping of digital materials (Löwgren, 2007). While one might disagree with this particular definition, it shows how central digital materials are to the field. However, here I will adopt the broader definition brought by Kolko (2011) of “a dialogue between a person and a product, service, or system” (p. 13). I’m also using his definition to inform my understanding of artifact, which would be what people interact with. But due to the importance of digital materials, the topic of digital decay seems to be of great relevance to Interaction Design. Digital Decay is a subject that has been discussed in the last 20 years, with many warnings about an oncoming Digital Dark Ages (Kuny, 1997) or a forgotten century, as the vice-president of Google, Vint Cerf states (Sample, 2015). Yet, even if we disregard the most

portentous undertones of the subject, there are many qualities in decay to be explored, not all of them negative (Edensor, 2005; Trigg, 2006; DeSilvey, 2006; Almond, 2009; Franzke, 2013 and Haslop, 2016).

One of the qualities revealed in decay, significant to this research project, is its ability to tell stories. Or, more precisely, its ability to suggest stories. Design Fiction is an approach that uses fictional objects as a medium for commentary or debate. And while there’s plenty written about Design Fiction regarding it as a Critical Design methodology, there’s less about the fiction in Design Fiction. While Sterling (2013) states that “Design fiction doesn't tell stories” and Morrison et al. (2013) suggest that “there is a need to focus less on the fiction and more on the design in design fictions” (p. 54), it misses one of the main characteristics and strengths of Design Fiction, which is contextualizing its design, questioning its social or ethical consequences, putting the human experience at its center, and communicating those ideas in an accessible medium.

I would also like to clarify some different uses of the term "material" during this research. When thinking of digital materials and what "material" in that case means, Leonardi (2010) draws from three dictionary definitions of materiality: matter, practical instantiation and significance. The first refers to material perceived as tangible or physical; the second refers to material as in opposition to the theoretical or abstract; and the third refers to importance or relevant. I find the first two definitions of relevance to this research — when I refer to digital materials or materiality I'm using the first while, when describing something as material or immaterial, I'm referring to the latter. The first definition also needs another clarification: Leonardi (2010) makes a point that albeit commonly used to refer to the physical and tangible, matter does not necessarily convey physical properties, but a set of qualities:

"[...] when those researchers describe digital artifacts as having “material” properties, aspects, or features, we might safely say that what makes them “material” is that they provide capabilities that afford or constrain action." (Leonardi, 2010)

1.3 Research Focus

Taking this into account, this research will focus on the immaterial qualities from both Design Fiction and Digital Decay. It will start by examining the definition and characteristics of decay and digital decay, the definition and characteristics of design fiction and the development of a design fiction artifact.

• How can decayed artifacts (digital or not) can contribute to the material spectrum of Interaction Design, specially when engaging with what is generally considered immaterial or intangible – such as imagination, memory and fiction.

• How can Design Fiction, as an Interaction Design methodology, reveal the qualities, consequences and human experiences that emerge when interacting with Digital Decay?

1.4 Expected Contributions

According to Lindley (2015), due to its early stages of development, Design Fiction processes and final results inevitably are relevant not only to the area that it is being applied (Digital Decay, in this case), but to Design Fiction itself. Thus, the expected contributions are twofold: one is to understand digital decay in interaction design, not only as something that should be avoided (as cautioned in the Digital Dark Ages) but as a design material, one that might present positive or even poetic qualities. The second is the possibilities of design fiction as a methodology for conveying ideas and immaterial qualities. It examines how the fiction can contribute to this goal and what methods can support this objective.

2.

Decay

This section will discuss Decay, its definition and, drawing from fields such as history, archaeology and philosophy; some of its immaterial qualities. Then it will explore Digital Decay, its causes and some of its own particular characteristics. 2.1 Definition

"The history of decay corresponds with a critical

awareness of the mutability of time."

(Trigg, 2006, p. 97) First and foremost it is important to clarify the definition of decay used in this research — and how they might relate to the idea of waste and ruin. I will adopt and elaborate on the definition used by architect and digital media researcher Almond (2009), who suggests decay as a “natural, entropic process of degradation over time.” (p. 55). By using the word natural, he differentiates between decay that occurs through use and time, and decay that is intentionally caused, which he calls damage. I find this distinction problematic, for damage might refer to the result of decay, regardless of intention. Rather, I prefer to understand natural decay as inevitable — so while decay might be accelerated or slowed, it can’t be stopped. The use of entropic in relation to decay is more satisfactory, as it hints to a process that is chaotic and unpredictable: so while decay might be expected, its results are unexpected or without control. As for degradation, it implies a subjective aspect to decay: one where the original properties of an object are worsened or lost. This definition of decay also encapsulates the concept of destruction — it might differ in terms of time span and intention, but the results are the same nonetheless. Lastly, while this definition applies to physical decay, I find it suitable to other types, such as the decay of a society — or digital decay.

The byproducts of decay can be referred as waste or ruins. As Edensor (2005) states, “[…] the fate of nearly all things is to eventually become waste when they lose their value or relevance” (p. 109). If waste is the result of decayed objects, then ruins are the result of decay in man made spaces, buildings and structures. Thus, much of the discussion about decay will be as in reference to ruins.

2.2 Qualities of Decay 2.2.1 Decay through History

Dylan Trigg is a philosopher who works in areas such as phenomenology and existentialism, and philosophies of space and place. Trigg (2006) describes how humanity’s relationship with decay changed: ancient civilizations such as the Mesopotamians were almost fervently against it (p. 98) while at the end of the Roman Empire, decay brought “nostalgia, piety and abstinence” (p. 99). Moving to our era, his position is that our current times are characterized with the end of reason as the propeller to progress. The result is cultural pessimism: an acknowledgment of the environmental, political, economic and social collapse, resulting in apathy and cynicism (p. 116). Due to its fragmented quality, he sees a distinction between ruins and monuments. In this fragmentedness he identifies ruins as an ally, something to be celebrated and a constant reminder of the exhaustion of reason as a conduit for progress (Trigg, 2006, p. XIX).

2.2.2 Decay and Memory

By considering ruin as a reminder, Trigg (2006) brings up the connection between decay and memory. Edensor (2005, p. 125) points out that ruins possess “temporalities”, conjuring histories, memories or past trends. This association of memory and decay is further strengthened by both having this fragmented quality (Edensor, 2005, p. 140). Yet, Edensor further argues that ruins do not evoke only the past, but quietly they suggest the present and future (p. 125). This view is shared by Schacter & Madore (2016) who state that remembering the past and imagining the future both rely in a form o memory called “episodic memory” (p. 246).

Almond (2009) describes decay and memory as existing in an “inextricable relationship” (p. 11). For him, decay requires memory to exist: if we don’t remember how it was then there is no way of establishing decay. And with our ability to recognize patterns of decay, one could visualize the previous state of a decaying object even without actually knowing how that object really was. Lastly, Trigg (2006, p. 97) argues that ruins are both material and immaterial (and here one should infer that he’s referring to ruins as matter): while physically present, they demand a reaction from us:

"In the gaze of decayed place, decline individuates itself. What we see in the place rouses the imagination. Through an imperceptible yet dormant correspondence between consciousness and the ruin, an uncanny dynamic emerges in which ruin and subject are recognized in each other." (Trigg, 2006, p. 97) This is similar to how geographer DeSilvey (2006, p. 318) sees the degradation of cultural artifacts: rather than perceiving them as negative, she adopts an interpretative approach, in which decay does not erase cultural memory, but actually transforms them.

2.2.3 The process of decay

Edensor (2005) points out other additional characteristics of ruins: he suggests that, albeit mundane, they still hold the promise of something unexpected, being ripe with “transgressive and transcendent possibilities” (p. 4). During the process of decay, objects transform, usually in unexpected in chaotic manners. It reveals their inner workings, such as exposed pipes and wire in a damaged wall; mass produced artifacts, once identical, become unique. Paradoxically, objects also tends to hybridize, their materials spilling and wrapping on each other, becoming inseparable. (Edensor, 2005, pp. 108 – 114). Thus, the process of decay not only transforms objects and structures, they transform our relationship with them. 2.3 Digital Decay

"But maybe the unexpected software glitches are a

metaphor for digital aging, or even digital imagination."

(Almond, 2009, p.31) Digital decay can be defined as decay caused by the decomposition of binary code (Haslop et al, 2017). While the separation between digital and physical seems natural or even obvious, it is important to note that they are intimately related: physical damage to computers will affect its data. As Sterling (2001)

states: “Very little materiality, is very, very far from no materiality at all” (p. 15). Thus, many (but not all) causes of digital decay are actually from physical decay. The causes, as described by Sterling, can be summarized as:

Archival — Bits don’t have an ideal archival medium and while a well stored piece of paper might last 200 years, there is no digital equivalent that lasts more than 50 years: tapes demagnetize and CDs delaminate in a considerably shorter time.

Obsolescence — OS can be replaced, updated or simply go out of market, applications might be render incompatible, servers might go down and weblinks redirect users to empty pages.

Accessibility — Compression algorithms might render data unreadable, encrypted data without keys become useless and moving data around might cause errors, resulting in corrupted files.

One major consequence of digital decay is what some refer to as an upcoming Digital Dark Ages, where most of the information from the 20th century might be lost in the future, causing a gap in knowledge similar to the one perceived after the fall of the Roman Empire (Kuny, 1997). While this is in no way an unworthy effort, there are other possibilities of seeing digital decay beyond preservation. Working with the frame of architecture and computational design Haslop (2016) explores how digitally decayed files can materialize in architecture. She explains that while there is plenty of literature related to preservation in the Digital Dark Ages (see Schlieder, 2010; Smit et al., 2011; Maltz, 2014), there’s “little on embracing digital glitches as an aesthetic of the aged that has its own value and heritage” (p. 16).

2.3.1 Qualities of Digital Decay

It was already mentioned the role that temporality plays with decay — when speaking of its digital counterpart, this seems to be less so. Sterling (2001, p. 21) stats than, different from a painting that fades slowly and nostalgically, software fails occur instantly and fatally, as in the blue screen of death. Thus, while decay in the physical world might be viewed as beautiful or poetic, digital decay brings a “temporal anxiety” (Haslop, 2016, p. 13)

However, between working 100% as intended and complete computer failure, there’s another space where digital decay manifests: the glitch. Haslop (2016) defines the glitch as “a sudden malfunction or fault caused by the harsh reality of digital decay” (p. IX)

Figure 1: Experiments made revealing different types of digital decay on a photography From left to right: original image, the image displayed in lower resolution, the image with multiple compression applied, and the image glitched, as result of data error

Further, Haslop identifies on the glitch an opportunity to see the human in the digital:

“Glitch deepens the appreciation of human agency and creativity within the digital realm of architectural design in the way glitch humanizes the computer” (Haslop, 2016, p. 14) Almond (2009) establishes the potential of analogy between the physical and the digital. Since the creation of our digital artifacts, we imposed metaphors on them. He argues that two of these metaphors stand out: memory and decay (p. 9). He then describes the situation of a friend, who had a problem with its digital camera: “slices of old images stored on the memory card were forcing their way into the most recently taken images.” (Almond, 2009, p. 74). Almond describes the results as “mesmerizing”. Similar to Haslop, Almond sees a human quality on these results. He writes:

“The machine is effectively decaying its digital memories, but in a way which is creative. One can extract undeniable similarities between this phenomenon and the human mind, and its tendency to fill in the gaps of a decaying memory through imagination, and even the blending together of very separate experiences into a single memory.” (Almond, 2009, p. 74)

2.4 Related Work

Other qualities of digital decay can be seen on the related work presented in this section. The first reveal surprise and beauty, while the second questions some other desired effects of decay, while the last explores the connection of decay and memory.

The Eventual Decay of the Super Mario Brothers

To the artist Andrew Ohlmann (2007), there’s beauty in things that are dying. He notices how his love for electronic music stems from glitches, distortions and feedback. For him, those “mistakes” add an appeal to a style that would be otherwise cold and impersonal.

One of his projects consisted of hacking a Super Mario Bros ROM (a file that contains the data from the original game cartridge). He opened the file in a text editor and changed a few parameters, while keeping the same file size. He then ran the modified ROM in a program that emulated the original console and watched the outcomes. While the majority of the results in the game in an unplayable state, the few instances where the game actual run were noteworthy. He writes:

“The resulting images and experiences one gets from hacking Super Mario Brothers in such a fashion are glorious. Colors shift at will, Mario walks through walls, music changes when you stomp on an enemy, the background turns into walls and walls of text. When you insert glitches into the game, you decay it in some fashion.” (Ohlman, 2007)

Figure 2: One of the results posted by Ohlman

The Eventual Decay of the Super Mario Brothers brings attention to the fragility of digital materials, where a few changes on its code can render the entire artifacts inaccessible. But more importantly, it reveals the joy and surprise in unexpected glitches: sprites get repurposed and data is displayed where it shouldn’t be. The act of hacking the game is not one with a specific objective, but one of curiosity and exploration.

3 Years and 6 Months of Digital Decay

For the fair Internet Yami-Ichu London, at the Tate Modern, Japanese artist Shinji Toya presented and sold CDs containing an audio file. The audio instructed the audience to visit a website that screened the movie “Is the Beauty in Forgetting?” The video is about forgetting in the digital age, speculating on the negative effects of having memories that never disappear. For Toya, since digital media can be easily replicated, it can exist indefinitely and, in case of personal data, this might have negative effects.

The screening of the video started on April 7th, 2016 and during the passage of time, its audiovisual quality has been deteriorating: the sound is filled with noise while the images are getting more and more distorted. After three years and six months, on October 7th 2019, the entire video will be gone. This period of time corresponds to the lifetime of an average CD-R media.

Figure 3: Current state of the video as in May 20th 2018

Here Toya anchors the digital decay directly with its physical medium. It also uses the artwork to speculate on how digital decay could happen in the internet, where forgetting might be desirable.

Agrippa (a book of the dead)

Figure 4: Picture of the Deluxe Edition of Agrippa Photo by Kevin Begos Jr.

Created in 1992 by novelist William Gibson, artist Dennis Ashbaugh and publisher Kevin Begos Jr., the work consists of a poem written by Gibson contained in an artist’s book, built by Ashbaugh. Two editions were published: a small and a deluxe version. The deluxe consists of a case with pages of DNA sequences, set in a double column of 42 lines;

copperplate etchings by Ashbaugh and a 3.5" floppy disk containing the poem. The small version was set in single columns and didn’t contain the etchings.

The floppy disk in particular became notorious by encrypting itself after its first use, rendering it useless afterwards. And since the poem scrolls down automatically on the screen, even recording it might be challenging. Similarly, the text in the pages of the book were printed with photosensitive chemicals, fading gradually after light exposure. Decay is also highlighted by the contents of the poem, which deals with Gibson’s memories of his father, who died when he was young and a photo album that he found (Dannat, 1992).

Figure 5: Encrypted text at the end of the poem This instance of the program is being run in an emulator

Agrippa is an artwork that meshes the theme of decay in different ways, both tangible and intangible: the pages physically fade away as does Gibson memories of its father. As for the self-encrypting floppy disk, it become an archival challenge: to be classified, it has to be read, which immediately prevents further queries.

3.

Methodology

As the previous chapter pointed, one of the qualities of decay (digital or not) is that of conveying or suggesting stories. In addition decay can also be poetic or nostalgic, qualities that are often found in fiction. Here I’ll describe the methodology used in this research, Design Fiction, which also use stories, but to convey possible futures. Further, I’ll discuss the expected outcomes of the project and related work.

3.1 Definition of Design Fiction

Initially coined by Sterling (2005, p. 30), Design Fiction was popularized by Julian Bleecker, who described it as “a conflation of design, science fact, and science fiction” (Bleecker, 2009, p. 6). For him, design is the act of materializing ideas, while design fiction is the act of imagining near future worlds and creating artifacts that inhabit this world. Later, Sterling himself formulated his own definition as “the deliberate use of diegetic prototypes to suspend disbelief about change” (Sterling, 2012). While he doesn’t elaborate on the term diegetic, he’s most likely referring to Kirby’s (2010), who defines diegesis simply as the fictional world (Tanenbaum, 2014).

3.2 Qualities of Design Fiction

To Bleecker the fiction part is as important as the design: a good story not only tells about the object, but involves people and social practices. When describing the props used in the 2002 movie Minority Report he states:

“They aren’t primarily useful as design ideas for future technologies — although they are often received as such, and every advantage. Instead, and in their most useful mode as design fiction objects, they serve to incite conversations that are more cautionary than aspirational.” (Bleecker, 2009, p. 27) This view is shared by Tanenbaum, who states that design fiction “uses narrative structures to explore and communicate the possible futures for technology” (Tanenbaum, 2014, p. 22). For him, the rules and constraints contained in a fictional world are the reasons for the power behind design fiction. Tanenbaum recognizes the potential of storytelling, arguing that when we situate a design within a story we are forced to tackle more complex issues such as ethics, values, politics or emotions. In terms of HCI research, he sees design fiction as potential for a “method of envisioning”, a “tool for communication” and “inspiration and motivation for design” (Tanenbaum, 2014, pp. 22-23). He sees all these potentials unified through a narrative: and while a good story structure and characters are necessary, he also argues that the interpretation and understanding of the spectator is equally important.

Finally, Kirby (2010) suggests that fiction can help audiences became acquainted with future technologies. This is done by establishing the necessity of the technology, the normalcy of it and its viability. He uses the example of the 1981 movie Threshold, which depicted a successful heart transplant procedure one year before the first actual one took place and helped. Evidently, as put by Bleecker, one could imagine the opposite, where a technology depicted negatively may serve as a cautionary tale. In fact, Doctorow (2018) points out in a video essay

how the book 1984 from George Orwell gave the audiences a vocabulary to discuss the effects of a totalitarian state in the 20th Century — in this case, literally a new term, orwellian.

Thus, I identify in fiction a further potential for exploring or revealing immaterial qualities (e.g. emotion, imagination, insecurities etc.) contained within the design artifacts. If we examine Leonardi’s (2010) second definition of material, the practical instantiation, one could argue that Design Fiction materializes these qualities.

3.2.1 Design Fiction and Speculative Design

One other similar type of methodology which sometimes is used interchangeably from Design Fiction is Speculative Design (Dunne & Raby, 2013, p. 100). Dunne & Raby (2013) argue that Design Fiction, by coming from the technology industry, put a stronger emphasis on future technologies and ultimately suffers from “dependence on referencing the already known” (p. 100). Thus they favor Speculative Design as a mean of envisioning things that are very different, suggesting completely different times or places. Auger (2013) on the other hand, argues that the word “fiction” immediately suggests that “the object is not real” (p. 12), while the word speculative suggests “a direct correlation between ‘here and now’ and existence of the design concept” (p. 12).

There is of course a problem of what fiction is: it could be a suggestion of something that is not real (as Auger interprets) or it could be a narrative that depicts imaginary characters and events. Since the definition by Sterling already suggest the presence of diegesis, here I’ll adopt the second definition. And here is where I draw the core difference between the two methodologies: while Dunne & Raby (2013) consider the objects in Speculative Design as “props for nonexistent films” (p. 89), in Design Fiction they would be props for existent films. Hence, if in Speculative Design the prop is the protagonist and the fiction is secondary (Dunne & Raby, 2013, p. 100), the opposite is true for Design Fiction.

3.3 Design Fiction as Research

Meanwhile, Grand & Wiedmer (2010) see in design fiction and the notion of possible futures a design research strategy, one that benefits from the qualities of Cross (2006) “designerly ways of knowing” (p. 5). Here’s how they describe what should be Design Fiction:

“[...] systematically questioning and deconstructing the self-evident, transcending it towards new, possible futures; concretely materializing, visualizing and embodying relevant controversies and perspectives in the form of artifacts, interfaces, installations and performances; asking ‘how the world could be’ instead of discussing how the world is; thus taking the inherent contingency of the world seriously and thereby exploring insights from different disciplines.” (Grand & Wiedmer, 2010, p. 5) Markussen & Knutz (2013) further expands the possibility of Design Fiction as a research activity. They claim that even though Grand & Wiedmer (2010) propose a “toolbox” for Design Fiction, they never detail how the tools should be used. Rather, Markussen & Knutz start by re-emphasizing the role of fiction (as in Bleecker), suggesting that the designers should be authors as well. Then, they propose the use of poetics of design fiction as a methodology. They define poetics

as a discipline within literary theory and semiotics concerned with “verbal and compositional techniques of fictional world making in the literary work of art” (Markussen & Knutz, 2013, p. 231). When applied to design fiction, they propose that this poetics take shape in “various techniques for prototyping possible futures, the role of utopias and dystopias in design research experiments and the types of knowledge that may result from practicing design fiction” (Markussen & Knutz, 2013, p. 232). Further they also propose a 4-step method for Design Fiction, which will be explored in detail in the design process chapter.

Years after Sterling coined the term, Lindley (2015) acknowledges that design fiction, while still in its infancy, has become ambiguous and hard to define. He proposes a pragmatic framework, whereas instead of pinpointing an exact definition of design fiction, it should be viewed according to its context. Therefore, when examining research through within his framework, he concludes design fiction can be applied to all the three categories presented by Frayling (1993): research into design, research through design and research for design.

3.4 Types of Design Fiction

Continuing with his pragmatics framework, Lindley (2015) suggests a range of Design Fiction artifacts, which he separates them in three categories: intentional design fiction, incidental design fiction and vapour design fiction. The first is the one practiced by designers, who use the suspension of disbelief of storytelling intentionally to suggest and propose new designs. The second category is when design fiction activity happens as a by-product of storytelling, such as in the movies 2001: A Space Odyssey from 1968 and the already mentioned Minority Report — while their primary objective is art or entertainment, they might still inform design fiction activities. The last one refers to corporate films such as A Day Made of Glass by Corning Incorporated (2009) or Productivity Future Vision by Microsoft Corporation (2011): while presenting future possibilities in filmic version, for Lindley they lack any critical or exploratory element usually present in design fiction, being more of a borderline case.

3.5 Design Fiction as Anti-Solutionist

Lastly, Blythe et al. (2016) suggests Design Fiction as a strategy against what they describe as “solutionist” design. Drawing from city planning critiques, they illustrate a tendency in “prototyping reductive ‘silver bullet’ solutions for complex social, political and environmental problems” (Blythe et al., 2016, p. 2). They argue that one of the reasons on why solutionist design is so appealing is how they are represented: one example given is Le Corbusier’s Radiant City, a problematic proposal that nonetheless was materialized thanks to its poetic description. In fact, this might fit perfectly on the vapour design fiction described by Lindley (2015). However, by making a connection to Critical Design, the Italian Anti Design and the Radical Design, Blythe et al. (2016) suggest Design Fiction as a rejection of this approach. Drawing from the notion of unuseless objects (objects that solves one problem while creating many others) or questionable concepts (intentionally flawed solutions to complex problems), they suggest that deliberate use of “unuseless, partial or silly objects”, instead of offering immediate solutions, can help in articulating and exploring problem spaces while stressing the fragility

3.6 Summary

Here I explored Design Fiction as a methodology that places design artifacts in a fictional setting (diegesis). It uses a narrative not only for conveying the qualities of properties of an artifact, but to unfold possible conflicts, social or ethical concerns. While it does present design artifacts, they are not the protagonists of the narrative: the characters are. Thus, I see Design Fiction as a methodology that puts the human experience in the center — and here I’m also taking a stance that stories are always about humans. Design Fiction is also not about necessary offering solutions to certain situations, but exploring possible problem spaces, starting debates and conversations.

By being anti-solutionist and closely aligned with critical design, Design Fiction is also a valid research methodology. This research in particular will adopt Frayling’s category of research through design, which Lindley (2015) describes as “a method for simultaneously producing knowledge and insights that pertain to design fiction practice, as well as other domains” (p. 5).

3.7 Expected Outcomes

The previous section explained how Design Fiction presents artifacts are contained within narratives. However, narratives come in different types and forms. By having close ties to science fiction films, movies tend to be the preferred outcome of design fiction (Lindley, 2015). Kirby (2010, p. 45) states that movies have the advantage of showing how a technology works — something that a novel, no matter how evocative, can’t. This would be true if one understands diegetic prototypes only as objects. However, here I prefer to use the definition of prototype as “any representation of a design idea—regardless of medium” (Houde & Hill, 1997, p. 379), which is better aligned with my use of the term artifact. Thus, there is no reason to limit Design Fiction only to movies. For instance, Edwards et al. (2016) presented the outcome of their research as a written narrative in form of a fictional journal. As Lindley (2015) points out, there is no specific medium for Design Fiction.

Nonetheless, movies do have their own benefits: not only they are a visual medium but they can also incorporate a temporal element, usually a difficulty when presenting digital materials (Löwgren, 2007, p. 11). Another advantage of film is a familiarity of audiences with cinematic language (Bleecker, 2009 and Kirby, 2010), facilitating the communications of its ideas. For this reasons, this project will also use film as its medium.

3.8 Related Work

Here I present two examples of Design Fiction that uses the narrative to debate about the repercussions of design artifacts. They also demonstrate how different mediums can approach its subject matter.

Duas de Cinco e Cóccix-ência

Directed by Cisma in 2014 as a video clip for two songs by Brazilian rapper Criolo, Duas de Cinco e Cóccix-ência depicts the musician hometown Grajaú, a district south of São Paulo, in the year of 2044. Currently plagued by social issues, Grajaú have high crime rates and lacks access to many public services. Its futuristic counterpart doesn’t fare much better: albeit filled with futuristic gizmos and other advanced

technologies, none of its problems seems to be gone. The movie follows a groups of students who decide to skip class, manage to get hold of a gun and commit a series of crimes against more affluent citizens – a story most likely is still happening today.

Figure 6: Stll of Duas de Cinco showcasing some of the technologies

Combining impressive special effects against an impoverished backdrop, the movie is effective in showcasing technologies that range from positive, such as the equipment employed in classrooms, to oppressive, such as the floating surveillance cameras that follow citizens. But most of the time these artifacts are just indifferent: background objects that the characters can’t relate to. The video offers a perspective of Design Fiction from an unrepresented group, where technology is designed in a way that does not acknowledge their existence.

Liking What You See: A Documentary

Written in 2002 by American science fiction writer Ted Chiang, this short story imagines a technology that, when implanted on the brain, induces deliberate neural lesions to its users, resulting in a fictional syndrome called “calliagnosia”. While sufferers from this syndrome are still able to recognize faces, they can’t appraise them, thus being unable to tell if someone is beautiful or ugly.

The protagonist of the story is Tamara, who had the implant for most of her life but recently chose to deactivate it. When a student organization proposes that every student at her university adopts the calliagnosia process, Tamara must reflect if she wants it back or not. Written as a documentary, characters give their first-person testimonials about their experiences and opinions. This allows Chiang to explore different points of views and consequences of this new technology. There are concerns about how works of art will be experienced, about beauty standards and how they might be transformed and victims of disfigurements such as burn scars tell how much improved their life became. Chiang avoids giving a definite answer of whether calliagnosia is good or not, leaving the reader to take its own conclusions.

By using writing as a medium, Chiang is able to suggest complicated imagery, such, how one would look to a face without being able to tell if it is pretty or not? It is a narrative unconcerned with evoking the look and feel of a certain technology, instead being more interested in the

4.

Design Process

In this chapter I describe the activities conducted for this research: a conceptual exploration, a revision of specific Design Fiction methods, followed by a writing workshop and the creation of a design fiction artifact.

4.1 Conceptual Exploration

In his 1998 novel Rings of Saturn, W.G Sebald structures his meditations around a walking tour on the county of Suffolk in England. Consequently, as a first activity I considered fitting to start my own explorations with a short walk — the objective being finding out examples of decay and what do they tell. The conceptual exploration was also done before any specific Design Fiction method as a way of having a “serendipitous understanding” of the subject — i.e. one coming from spontaneous observations rather than structured research. This exploration was extended to my home, where I examined the decay on different household objects. Here are some insights from the exploration.

Figure 7: Broken gate with garbage around and abandoned bicycle

Decay as Indifference — Close to where I live there are some abandoned bikes: their loose chain, empty tires, rust and awkward position reveal both the amount of time since they were abandoned but also the indifference towards their presence. This indifference can also be seen in a closer abandoned gate, surrounded by garbage.

Decay as Stories — In the street there is also a damaged car — it has been like that for a while. Perhaps the owner doesn’t have time or the resources to repair the car, perhaps he’s waiting for the resolution of an insurance bureaucracy or maybe he doesn’t use the car often enough to justify repairing it. And this comes without asking how the car got damaged to begin with.

Figure 9: Damaged book and used toothbrush

Decay as patterns of use — It can be seen in a book that I’ve never finished: looking closely one can even locate where in the book I’ve stopped. Our toothbrushes are particularly revealing: even though both were bought together, mine is considerably worse, since I tend to brush much harder.

Each insight is of course not exclusionary and in fact, most of them overlap. The experiment showed not only how much decay reveals about objects and places but also how much decay is present in our surroundings. Many of these qualities, such as indifference, are not material, revealing again the potential of decay materializing them.

4.2 Design Fiction Method

After documenting the qualities of decay (both through the exploration and the research conducted), I examined possible methods of exploring decay within Design Fiction. The previous chapter mentioned Markussen & Knutz’s (2013) four-step method for prototyping design fictions. They consist of a writing phase; developing basic rules of fiction; experimental process of world-making and prototyping design fiction — all conducted on a workshop. The first step consisted of the participants reading a fragment of a science fiction story, writing mini-scenarios (such as a remarkable experience or situation they had) and then applying this scenario on the context of the science fiction story. Then participants created the basic rules of the scenarios, the “what-if” stories, such as “what if we live in a society with no money?”. After the basic rules were established, the participants started “sketching” possible interactions and objects that are contained in this scenarios which leads to the final step, of prototyping the artifacts contained in this envisioned future. I adopted Markussen & Knutz method because it goes beyond explaining what Design Fiction is and inform how it can be practiced. By providing a step-wise method, it also adds a systematic approach where each step clearly informs the next — without sacrificing the open

However, there are a few issues from their method: first is how little fiction seems to be involved in their process. In fact, aside from science fiction story presented at the beginning, here’s the only instance, during the mini-scenarios, where an actual story seems to be included:

“Place this ‘strange’ memory in the context of The Civil War in Denmark, by adding a few sentences that would frame the situation as if it was taking place, either before, during or after the civil war (e.g. ‘…this happened just two years after the war’ or ‘…this made me think about when the war would come to an end’ or ‘…from that moment, I knew that the war was about to begin’).” (Markussen & Knutz, 2013, pg. 235) All the other phases follow up with rules, sketches or prototypes, without ever revisiting the potential of narratives. When seeing this process through the previously discussed strengths of Design Fiction, the results are mixed: in one hand, the artifacts are successful in presenting elements of critique or informing the broader context which they contain. Yet, none of them present the potential of fiction for communicating its ideas and engaging its audience, as suggested by Bleecker (2009). Further, the process between Phase 1 and 2 ends up being convoluted, alternating between developing a future scenario, writing stories or experiences within that scenario and then establishing the basic rules of fiction. The result is that the mini-scenarios developed in the first step seem to be completely absent in the final results. For this project, I suggest a reworking of the steps as follows:

Step 1: World building

Objectives: exploring implications of Digital Decay

How: creating a timeline with possible futures stemming from current events and technologies and consequences of decay, exploring “what if” scenarios. The timeline also helps situating between near and far futures.

Differences from Markussen & Knutz: instead of an author handing down the scenario to the designers, the designers themselves take a role as writers. The “what if” scenarios that originally occurred in the second phase is moved here. This points to a more active role for designers in the creation of the fiction. Step 2: Developing stories

Objectives: exploring the human experience within Digital Decay, the fiction within Design Fiction

How: Using writing, creating situations of stories situated within the previous timeline. Drawing inspiration from previous experiences or other references. Differences from Markussen & Knutz: a re-sequencing: parts that were originally in the first step are now moved here.

Step 3: Prototyping diegetic artifacts

Objectives: elaborating on the possible artifacts suggested in previous step, the design within Design Fiction

How: examining what artifacts are contained or suggested in the previous stories and detailing their use and function through sketches or diagrams.

Step 4: Creating the narrative

Objectives: create a narrative that conveys the stories and designs created on the previous steps

How: using traditional storytelling techniques

Differences from Markussen & Knutz: this is an added step, absent previously. It expands the spectrum of design materiality by asking designers to engage more actively in designing with imagination and fiction.

4.3 Workshop

Since one of the main issues of the original method was a confusion of activities in the first two steps, a small writing workshop was conducted to validate the efficacy of the reviewed version. Another objective of the workshop was having different perspectives and accounts of decay and digital decay and a collaborative exploration of possible scenarios. In that sense, the activity was closer to Blythe et al. (2016):

“Rather than attempt to design towards a pre-defined problem space, the workshops encouraged a collective re-imagining of a future world. This differs from participatory design techniques that use collective making as a practical a way of gaining clarity on potential solutions to problems.” (Blythe et al., 2016, p.9) Another focus of the workshop was on the written medium. This was chosen following Edwards et al. (2016) approach of “writing as creative design,” which elicits reflection-in-action. It is also a quick an inexpensive method for storytelling that might be more appropriate for conveying immaterial qualities at this stage of development.

Figure 10: Participants on the walk

Due to time constraints, the workshop was conducted with only 3 participants, aged between 20 and 30, all with some design background. As in the Conceptual Exploration, all participants were invited to a walk, where they were introduced with the topic of decay. During the walk and talk, participants shared their experiences and understandings of the subject. This step was designed as way of getting all comfortable with the subject, while setting the mood of the workshop as something more casual, where ideas could emerge more easily.

Figure 11: Participants drawing the timeline

After the walk, the participants were invited to fill collaboratively a timeline with possible events related to digital decay. Those included events that ranged from very likely (the end of major corporations that control data nowadays), possible (global warming and the melting of ice caps affecting server farms) to the far fetched (an Electromagnetic Pulse bomb erases all digital information on Earth). While focused on future events, past occurrences were also mentioned as an anchor or inspiration for upcoming scenarios. The discussions also involved other desirable outcomes from decay, such as privacy, concealment or privacy.

Figure 12: A representation of the timeline drawn by the participants. The original version is included in the Appendix.

After finishing the timeline, each participant was invited to write a short story or outline, elaborating one of the scenarios discussed. The complete outlines can be read in the Appendix. Albeit simple, the stories revealed potential tones and styles (comedy, thriller, etc.), approaching subjects such as authenticity or the loss knowledge. While all of the suggest possible systems or practices, none of them are particularly concerned solely with technological objects, as mentioned in Dunne & Raby (2013).

Most importantly, the workshop demonstrated that the rearranged steps were able to flow naturally from one to the other. While the participants didn’t follow with the step of prototyping a design artifact, it is not difficult to imagine how that would fare. The activities also demonstrated that while separated in steps, often one activity would overlap with another — in this manner, they’re better served as guidelines rather than strict rules that can’t be broken. Accordingly, one could see steps 2 and 3 as interchangeable: one might prefer to think of stories before artifacts and vice-versa, and its most likely that they will inform each other in parallel.

One major aspect that could’ve improved the workshop is the presence of examples of digital decay and writing prompts as a guidance for the participants. Although all of them had their repertoire and brought many ideas, having extra material would definitely enrich the results and assist in case there’s any difficulty in generating ideas.

4.4 Creating the design fiction artifact 4.4.1 World building

Having verified the method through the workshop, I’ve started my own Design Fiction activity, this time individually. Continuing with the timeline, I included one future scenario that speculated on the possibilities of one commonly pointed solution for Digital Decay, DNA Storage, as discussed in American Chemical Society (2015). Those speculations included the possibility of using DNA of actual living human beings as storage in opposition of synthetic DNA that is stored in laboratories. Then I sketched some repercussions of this scenario, such as the humans that smuggle data in their DNA, parents that can inject custom data in their offspring DNA or people that have parts of their DNA under copyright restrictions.

4.4.2 Developing a story

With these scenarios in hand I’ve started developing a story of a person that, without having met her parents, discover that her DNA contains data left by her progenitors. To further complicate the narrative, I’ve speculated on the possibilities of the company going out of business and the copyright being transferred to a third-party, and the possibilities of the process of aging decaying the stored data. In this manner, the conflict of the story comes up from the situation of a person suddenly finding out about data left by her parents, the difficulties in obtaining said data and how this data is compromised due to decay.

4.4.3 Prototyping the artifact

Having outlined the story, I proceeded in fleshing out how the design artifact works. I’ve invented a company called Genomely that would offer parents the possibility of leaving memories through DNA storage. This is grounded in an existing technology where, by creating synthetic DNA strands, scientists can manipulate the pairing bases A,T,C,G that later are interpreted as binary code. The result is a storage method that is highly efficient — one gram of DNA might hold 215 petabytes of data — and resilient, if properly stored DNA can last thousands of years (Cornish, 2018).

Figure 13: How Genomely works.

This custom DNA is then injected inside a stem cell that will give birth to the child. The process of editing and inserting this custom data is also grounded on another real-world technology, CRISPR/Cas9, a method of editing genes of living organisms (Vidyasagar, 2018). While highly speculative, this process is not entirely implausible as seen in experiments of inserting video data in bacteria DNA (Ledford, 2017). The experiment also highlights how the video data already decays due to the imperfections of the technique:

Figure 14: Original image on the left, compared to the retrieved from the bacteria DNA Image by Seth Shipman in Ledford (2017)

4.5 The final movie

With the outline and design artifact developed, I proceeded in integrating them in a single narrative. As discussed previously, film was chosen as the medium for the narrative. I’ve decided to separate the story in two parts: the audio would be a narration explaining the experience of the character with Genomely while in parallel the visuals would be about the memories that the protagonist found. Since the beginning there was the idea of the audio and the visual aspects being initially unrelated and, through the narration, their relation becoming evident. While never explicitly stated, it was intentional that the audience would make the connection of the videos shown being the data that the protagonist found — an acknowledgment of Tanenbaum (2014) argument of the importance of audience’s interpretation and understanding.

For the audio I first gathered the outline written in the previous section and expanded in a full script (included in the Appendix). At this stage, one of the main concerns of the text was to keep a style that would sound natural when narrated. It was at this point that the title of film (The Gift from my Parents) was chosen, alluding to both the DNA that she inherited and the data contained within. For the narration itself I commissioned a professional voice over service to provide the audio — a trade of between costs versus time, convenience and quality. Before listening through all the samples I’ve decided to settle with the category of young adult, female, native English speaker. Choosing the voice was quite important and — by listening through the samples, I’ve chosen one in particular that conveyed a nostalgia towards the subject being described, something that I saw fitting for the film. When asked by the service to describe how the voice should be recorded, it was suggested a casual and nostalgic tone, with the latter parts being a little more emotional, since they were directly about the protagonist parents.

To depict the memories of the protagonist, I’ve selected footage that represented past memories — such as vacations, people on the beach, families. There was a combination between older amateur footage from the 50s through the 70s and newer ones, that were professionally recorded.

Figure 15 Comparison between different types of footage used The older recording on the right already showcase clearly signs

of decay, such as dust and scratches

The amalgamation of different types of recordings and the lack of any structural point out to the fragmentedness suggested by Trigg (2006) and is also an attempt to reproduce the tendency of decaying objects to wrap around themselves and

While the fragments were intended to be nostalgic, hinting at past memories, there was also the intention of adding an unsettling layer to the narrative, suggesting the anxiety towards digital decay, as described by Haslop (2016). To achieve this result, different effects were added over the footage. The first was a basic noise effect, followed by the displacement of the image in selected areas, simulating misplaced squares. Then certain parts of the video were designed to have their RGB channels misaligned, simulating an interference of the signal. The result is a “shaky” footage, where the color channel is visible:

Figure 16: The result of image displacement in blocks

Figure 17: An example of the RGB channels misaligned The effect is better perceived at the border of different objects

After the footage and the narration were edited, the remaining elements added were the non-diegetic ones. Those include the two short texts at the beginning, contextualizing the DNA storage and the CRISPR/Cas 9 technologies, the end credits and the soundtrack. The soundtrack was chosen following the criteria of being somber and dark, hinting at the unexpected revelations in the story; without being intrusive or drawing attention from the voice over.

The end result is a 223 second movie, currently hosted at the service Vimeo, accessible through the URL https://vimeo.com/270321807

5.

Evaluation and discussion

5.1 The Gift from my Parents

The final movie has two stories: one about the protagonist and how she discovered data inside herself, and another, much harder to parse, about her parents. Due to decay, the latter is almost abstract in its construction, merely suggesting to the viewer the life behind those images. Its degradation also provides additional qualities: it is unexpected, with the glitches intended to provoke uneasiness and apprehension.

None of the technologies presented in the movie are impossible and some of them might turn into reality very soon — although probably quite differently. The intention of the movie is not to predict future technologies, but to demonstrate some possible consequences of its application. By grounding the fiction in real, viable events, its message becomes much more powerful, adding almost a certain “urgency” to it.

However, there’s only so much a 4 minute video can achieve, especially when done by a single person with no professional expertise in film making. And not only the content of the movie is far from being an exhaustive examination of decay, it is perhaps doubtful that it can communicate all the ideas included without the supporting research presented. For instance, one possibility for the story that came after the voice recording was finished is that of the decay resulting in combined DNA storage across multiple generations. For that reason, the film can be better understood as a section of the larger project, rather than the encapsulation of everything discussed so far.

5.2 Process evaluation

In terms of the entire process, this project started by adopting the notion of decay and digital decay as potential materials for interaction design, examining through research and a conceptual exploration, what qualities those materials possess — in particular, its immaterial qualities.

Alongside, it used Design Fiction as a methodology — putting an emphasis on the fiction, to explore how decay (and its qualities) can be manifested in design artifacts. Afterwards, it analyzed Markussen & Knutz (2013) 4-step method for Design Fiction, reworking some steps to better accommodate the fictional elements. The final result was the movie, which depicted a design artifact affected by decay and, is simultaneously a design artifact that uses decay.

And so, if one considers the strategies for knowledge contribution outlined by Löwgren (2007); in terms of digital decay the research can be understood under the strategy of “Exploring the potentials of a certain design material, design ideal or technology” (p. 6) while in terms of design fiction, it better fits the approach of “Exploring possible futures which are rather far from current situations” (p. 7). 5.2.1 Perspectives for Design Fiction

This project proposed that the fiction in Design Fiction could be emphasized, and there’s much more on that regard to be explored. First is in investigating how different formats can tackle different subjects — videogames in particular, by being both recent and already closely related to interaction design, seem to be a

promising field. Second is how different narrative techniques can contribute to the practice: Markussen & Knutz (2013) already hinted at how their process relate to Pastiche Scenarios or Steampunk, but a more deep inquiry might be fruitful. Little in this research mentioned the similarities between design fiction and the genre of science fiction. It is safe to say that all forms of design fiction are part of science fiction, whereas the opposite might not necessarily be true. However, while the outcome of both practice might be indistinguishable, this project already demonstrated how different they are in their conception. Furthermore, they also are evaluated differently: this research hinted at how a grounding in reality benefited the design artifact and this and other criteria can be proposed. Those, together with existing design and literary criticism practices

Lastly, this project revealed how a multi-disciplinary approach can benefit Design Fiction, not only by different expertise required for crafting fiction but also for different perspectives when probing future scenarios.

5.2.2 Perspectives for Decay, Digital Decay and Memory Studies

The project demonstrated how rich decay can be as a design material. The same is even truer for digital decay, which is extremely relevant for Interaction Design. By examining the relationship of decay and memory through interaction design, there’s an opening for contribution to the recent field of memory studies.

Memory studies can be defined as a multidisciplinary area concerning with topics such as collective memory or the institutionalization of such memories (Kuhn et al., 2017, p. 4). In fact, when establishing the field, Roediger III & Wertsch (2008) cite a number of disciplines that can make contributions, with perhaps Architecture being the only related to design. And while there are many contributions of interaction design supporting memory studies (see Ciolfi & McLoughlin, 2012; Kostoska et al., 2013; Maye et al., 2017), there’s opportunity for IxD on their own.

5.3 The politics in Design Fiction and Decay

One criticism common towards Speculative Design is a blind spot regarding its own privileged position within society. As Prado & Oliveira (2015) states:

“In its ambition for envisioning how technology reflects social change, it assumes a very shallow perspective towards what these social shifts mean; it avoids going deeper into how even our core moral, cultural, even religious values might—or should—change. While SCD [Speculative Critical Design] seems to spare no effort to investigate and fathom scientific research and futuristic technologies, only a small fraction of that effort seems to be directed towards questioning culture and society beyond well-established power structures and normativities.” (Prado & Oliveira, 2015) This is true not only for Speculative Design but Design Fiction as well: just a glance at the literature presented in this research reveals a lack of diversity among the authors. Similarly, one could argue that this project also doesn’t fully address current normativities. The suggestion of multi-disciplinarity for Design Fiction should extend not only to authors from different fields of study, but for minorities and less represented voices. The previous example of Duas de Cinco + Cóccix-ência already demonstrates the potential of Design Fiction created by such

groups. Meanwhile, Haraway (2011) notion of Speculative Fabulations, which I encountered later in this research, can add a gender and environmental perspective to Design Fiction.

This perspective should also be extended to how one should look at decay. When discussing public spaces, it is not hard to associate that with lower income areas or other difficulties. With the assumption of decay as something positive, one could risk romanticizing about poverty itself. Similarly, one should be careful in not overlooking the crushing effects that decay can bring to people’s lives:

“In recent history, ruins and ruination have become hot political issues. Even when devastation is clearly attributable to so-called acts of God [...] the aftermath of a catastrophe has wide-ranging political implications, which reveal and disrupt assumptions about the power of individual agency, the role of government and community, and the ideology of social, moral, and economic progress.” (Hell & Schönle, 2010, p. 5) The same applies for the effects of digital decay: one should take in account the access and quality of resources and infrastructures available in different parts of the world, how technology fluency is present in different socioeconomic groups and, if data is to be preserved, which data?

6.

Conclusion

The project examined the qualities of decay and digital decay — especially their intangible ones, such as memory and imagination. The results revealed a rich spectrum of design materials that can be explored in Interaction Design.

It suggested Design Fiction as a suitable methodology — for fiction, by focusing on human experiences, is a powerful way of articulating those immaterialities. To do so, it reviewed current Design Fiction practices, formulating a method that could better employ storytelling. Then, it employed this method in the creation of a design fiction artifact, the movie The Gift from my Parents, that deals with a potential solution for digital decay, DNA storage; what happens when these solutions don’t work quite well and the outcomes of decayed digital memories.

7.

Acknowledgments

Foremost I would like to thank Ingrid Skåre for her constant support through this entire project and for the company during its many walks.

I would also like to thank my supervisor Susan Kozel for her invaluable contributions and suggestions, which helped give shape to this project.

Many thanks to Jesper Hyldahl Fogh and Michelle Westerlaken for their feedback during the first draft seminar and the participants of the writing workshop.