Hybrid organizations

and resilience as drivers

for sustainability

A framework for rural development

Sofia Kullberg & Anna Stumper

Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation

Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits Spring 2020

Abstract

Sustainable development has often been associated with the urban context, but rural areas play a significant role in the resilience and the viability of a country’s economic, social, and environmental sustainability. Yet, statistics show how the population in rural areas is decreasing around the world and in Sweden, this has resulted in the closure of social and public services in rural areas. Previous research suggests that hybrid organizations are a beneficial way to organize to tackle complex societal challenges due to the value-driven organizational set-up that is both mission-centered and market-oriented. The purpose of this research is to explore how local rural communities can use hybrid organizations to drive sustainability and build resilience by using Röstånga Tillsammans as a case study. The design of the research is qualitative and interviews, complemented by documents were used as data collection methods. Based on previous literature we developed a preliminary theoretical framework that identifies the characteristics of resilience- and sustainability-driven hybrid organization: (i) community infrastructure, (ii) diverse and innovative economy, (iii) human-environment connection, (iv) community networks, stakeholder relationships and collaboration, (v) knowledge, skills, and learning, (vi) engaged governance and leadership, and (vii) long-term perspective. The findings support previous research that a hybrid organizational structure is beneficial for driving sustainable development, due to the greater flexibility and adaptability, allowing for greater projects and opportunities, while still ensuring the mission of the organization. The results add new knowledge by suggesting that hybrids can help increase community resilience by contributing to increased local capability of dealing with change and uncertainties. The findings from the case study support our developed framework, however, it becomes evident that hybrid organizations for local development act as means to build resilience with sustainable development as the main outcome. Thus, we conclude that the framework for resilience and sustainability-driven hybrid organization needs to be rephrased as resilience-driven hybrid organization

for sustainable development.

Keywords: Hybrid organizations, rural development, community resilience, sustainability, adaptive

List of abbreviations

CMC Computer mediated communication CSR Corporate Social Responsibility

IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

RT Röstånga Tillsammans

RUAB Röstånga Utveckling AB SDGs Sustainable Development Goals SDH Sustainability-Driven Hybrid TBL Triple bottom line

List of tables

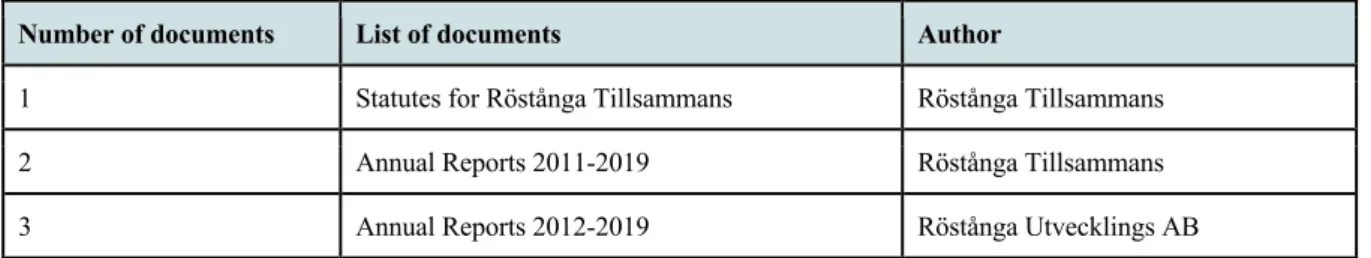

Table 1 Preliminary framework for resilience and sustainability-driven hybrid-organizations………… 13 Table 2 Overview of interviewees……… 16 Table 3 Overview of documents……….. 17

List of figures

Figure 1 Weak vs. strong sustainability……….. 7 Figure 2 An Integrated concept of community resilience……… 11 Figure 3 Organizational structure RT & RUAB………. 20

Table of contents

1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.1.1 Research problem ... 2

1.2 Previous research ... 2

1.2.1 Hybrid organizations and sustainable development ... 3

1.2.2 Rural sustainable development and resilience ... 3

1.2.3 Importance of place and agency ... 4

1.3 Purpose ... 5 1.3.1 Research questions ... 5 1.4 Layout ... 6 2 Theoretical framework ... 7 2.1 Sustainable development ... 7 2.2 Hybrid organizations ... 7

2.2.1 Sustainability-driven hybrid organizations ... 8

2.3 Resilience ... 9

2.3.1 Resilience – general implications ... 10

2.3.2 Community resilience – a definition ... 10

2.3.3 Characteristics of community resilience – an integrated concept ... 11

2.4 Preliminary framework for resilience and sustainability-driven hybrids ... 13

3 Research design ... 14

3.1 Case study research ... 14

3.1.1 Object of case study: Röstånga Tillsammans ... 14

3.2 Data collection and analysis methods ... 15

3.2.1 Semi-structured interviews ... 15

3.2.2 Document analysis ... 16

3.2.3 Qualitative thematic analysis ... 17

3.2.4 Validity and reliability ... 17

3.3 Limitations and reflection ... 18

4 Analysis ... 19

4.1 About the organization ... 19

4.2 Community infrastructure ... 20

4.3 Diverse and innovative economy ... 21

4.4 Human-environment connection ... 22

4.5 Community networks, stakeholder relationship, and collaboration ... 24

4.6 Knowledge, skills and learning ... 25

4.7 Engaged governance and leadership ... 26

4.8 Long-term perspective ... 28

5 Discussion ... 30

6 Conclusion ... 33

6.1 Limitations and further research ... 33

References ... I Appendices ... V

1

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

Sustainable development is often been associated with the urban context, but rural areas play a significant role as part of reconstructing our whole society towards sustainability. Rural sustainable development is an important phenomenon for the resilience and the viability of a country’s economic, social, and environmental sustainability. Investment in infrastructure, education, and health are essential for rural sustainable development and to create opportunities for areas in regard to productivity, income, and meeting basic needs (United Nations, 2015). The rural decline has resulted in a drastic decrease in both quantity and quality of services accessible to rural citizens, an aging population as young people move out of rural areas, leading to the closure of schools in rural areas (Li et al., 2016).

In Sweden, the larger proportion of the population lives in cities and urban areas (SCB, 2019), and the demographic differences between citizen in urban and rural areas vary with differences in average income, educational level, health, and social capital (Larsson et al., 2020). The decline in rural areas in Sweden has resulted in the closure of social services and public authorities such as the public employment service, the public insurance agency, local police, and tax offices, which has negatively impacted the welfare system and thus is a threat to equality (Erlingsson, 2020). Many of the rural areas in Sweden also face challenges in the reconstruction of society towards increased sustainability such as sustainable infrastructure, climate-smart agriculture, and societal resilience. To meet the challenges caused by rural decline, countries around the world are introducing different policies and measures to stimulate the rural economy including improvements of infrastructure and restructuring dispersed settlement patterns (Li et al., 2016). In Sweden, the government has established a proposition for a cohesive politic for Sweden’s rural areas that conclude that there should be equal opportunities for citizens to live and work in rural areas in Sweden and with the aim of long-term sustainable development (Swedish Government, 2017). The Parliamentary Rural Committee (2017) describes how rural areas are one part of society’s solutions to challenges including the climate crisis, but in order to do so, it must be possible to live and work there. Yet, many Swedish rural areas continue to face great challenges as public services and facilities are rationalized and close down. These top-down legislations, planning, and investment programs often face the risk of failing as they are not aligned with the real needs of the local citizens. Local governments are learning from such failures and are tackling the problem of depopulation by encouraging the collective self-reliance of citizens to shape and sustain their local living environments (Li et al., 2016). Rural communities consequently face the challenge of self-organize and find new ways to drive sustainable development and build resilience.

Sustainable development is not a new phenomenon and most often defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987, p. 16). Over the past decades organizations and governments have engaged in sustainable initiatives building on the concept of the ‘triple bottom line’ (TBL), a framework often used to evaluate sustainability taking into consideration economic, social, and environmental aspects. However, lately, this view of sustainable development has been criticized by both scholars and activists, as organizations often trade-off between the aspects and most times value the economic profit the highest (Elkington, 2018; United Nations, 2019; European Environmental Bureau, 2019). As the lack of capacity of communities, ecosystems, and landscapes to provide the goods and services that sustain our planet's well-being appears to increase and the mainstream ‘green’ growth approach and greater efficiency by itself cannot solve sustainability issues, new alternative paradigms of understanding and implementing sustainability are emerging. Resilience thinking is one of these paradigms and offers a new approach to managing resources by embracing human and natural systems as complex entities, acknowledging the continuous need for adaptation through cycles of change, and aim to understand the qualities of such system that must be maintained or enhanced to achieve sustainability (Walker & Salt, 2012). Resilience thinking sees communities and ecosystems they make use of as integrated, interdependent, complex, and adaptive social-ecological systems (Lerch, 2017; Berkes & Ross, 2013). As defined by Martin and Sunley (2015) resilience is “the capacity of a regional or local economy to withstand or recover from market, competitive and environmental shocks to its developmental growth path, if necessary by undergoing adaptive changes

2 to its economic structures and its social and institutional arrangements, so as to maintain or restore its previous developmental path, or transit to a new sustainable path characterized by a fuller and more productive use of its physical, human and environmental resources” (ibid., p. 13).

In this context, some scholars have called for new business models on how to manage businesses efficiently under sustainability principles and in the last decade, the phenomenon of hybrid-organizations is increasingly discussed in academic research as a way to organize and address both cross-sector challenges and sustainability issues (Haigh & Hoffman, 2012; Stubbs, 2017). The increased focus on corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the sustainable development movement together with a general trend toward hybrid organizations have increased expectations on organizations to respond to ever more complex and pluralistic institutional environments (Alexius & Furusten, 2019a). The characteristics of hybrid organizations are argued to open up opportunities, as these organizations have a broader set of resources available and the ability to expand their practices, allowing for innovation, the creation of new products and services, and to establish new ways of organizing (Mair, 2015). Hybrids reject old notions of trade-offs among economic, environmental, and social systems and generate mutually enhancing connections between business, and the communities and natural environments supporting them (Haigh & Hoffman, 2012). By using a value-driven business model that is both mission-centered and market-oriented it enables the sustainability of the hybrid organization while also positively contribute towards societal challenges (Boyd, 2009). These organizations exist around the world in different sizes, sectors, and with different societal goals. One rural community that exemplifies the characteristics of a hybrid-organization is Röstånga Tillsammans. The organization was founded back in 2009 after a group of committed residents in the village of Röstånga, in southern Sweden, decided to do something to stop the negative demographic and economic development of their community. Together they have bought and/or developed a museum, a restaurant, a brewery, and several apartment buildings in the community. The organizational structure keeps the profit in the local community, creates jobs, and contributes to the sustainable development of the local economy. The hybrid organization made up of a charitable initiative and a commercial development society combines economic and social goals. This study will explore how and in which way the hybrid organization has contributed towards building resilience and the continuous sustainable development in the village of Röstånga.

1.1.1 Research problem

The problem that we identified, is that data and research show how the population in rural areas is decreasing around the world and in Sweden, this has resulted in the closure of social and public services in rural areas. Rural communities consequently face the challenge of self-organizing in order to find new ways to drive sustainable development and build resilience. This study will look into how rural communities can self-organize to drive sustainability and build resilience through the use of hybrids.

1.2 Previous research

While there is substantial literature dealing with hybrids organizations and another stream of research on resilience as well as sustainability, studies on hybrid organizations as a means for building resilience and sustainable development are limited. Yet, there are few studies suggesting that using hybrid organizations can lead to improved sustainability and resilience in different communities, countries, or sectors (Douglas et al., 2018; Pape et al., 2020; Gibb et al., 2016). Douglas et al. (2018) study concludes that hybrid organizations in the context of Fiji contribute to the improved social and economic well-being for individuals, families, and communities, by providing employment, education, financial and support services, sustainable agriculture projects, and facilitating networking. These services are also shown to build community resilience, improve personal and family security, create opportunities for the future, advanced leadership skills, and to sustain the environment. By engaging in commercial activities such as product sales, service fees, project levies, and investment income these hybrid organizations are able to support their social mission and be less reliance on charity, government funding, or philanthropy. In the study, human wellbeing was described as “incorporates economic, social, environmental and cultural features that enable people to live a meaningful, dignified and satisfactory life” (Douglas et al., 2018 p. 508). Pape et al. (2020) study indicates signs of more market-based, hybrid organizations in the European third sector and suggests this is one of the responses to building resilience. The researchers

3 acknowledge that while it may be too early to tell it seems like the period following the global financial crisis in 2008 has led to an increase of hybrid organizations, as many third sector organization addressed self-sustainability by forming ways to provide economic support to their social mission (Pape et al., 2020). While focusing predominantly on financial sustainability in the Scottish social housing sector Gibb et al., (2016, p. 453) concluded that resilience is about “organizational flexibility, strategic repurposing, good governance, evolution and learning both across all levels of staffing but also in terms of a cultural openness to innovation, evidence, and research”. Their research suggests that models of hybrid organizations have been developed in response to market and other external pressures and to deal with changed circumstances and the evolving demands of the sector.

1.2.1 Hybrid organizations and sustainable development

The phenomenon of hybrid organizations is increasingly discussed in the academic studies, (Boyd, 2009; Haigh & Hoffman, 2012; Haigh & Hoffman, 2014; Schmitz & Glänzel, 2016; Alexius & Furusten, 2019a; Alexius & Furusten, 2019b; Mair et al., 2015; Stubbs, 2017), suggesting that these types of organizations may have certain abilities to facilitate complex contemporary change processes and sustainable development challenges (Alexius & Furusten, 2019b; Holt & Littlewood, 2015; Haigh & Hoffman, 2012; Haigh & Hoffman, 2014). Previous research on hybrid organizations distinguish between two main areas: (i) Public/private for-profit hybrids and (ii) Private for-profit/third sector hybrids (Grossi et al., 2017). Studies in the first area are predominantly based on public administration and public finance concepts, while the second area primarily focuses on management, organizational theory, and social policy. Further, researchers in the second field are increasingly recognizing that hybrid organizations can play an important role in tackling global sustainable development challenges. Simultaneously, some also argue that acute environmental, social, and economic challenges open up opportunities for hybrids (Holt & Littlewood, 2015). Alexius and Furusten (2019b) highlight the importance of organizational forms for sustainable transformation in society and suggests that hybrid organizations may have particular characteristics to facilitate this. The conclusion of their study suggests that hybrids have the ability to build trust between actors from different sub-paths and create neutral spaces for connection, dialogue, and exchange, but recognizes that in some cases it may only be temporary. Haigh and Hoffman (2012) highlight that hybrid organizations often are characterized by having close relationships based on trust, compassion, and vitality that are recognized as foundational to organizational resilience, learning, and innovation. Further, they identified three main objectives for ‘sustainability-driven hybrids’ where their approach differs from traditional organizations including social and environmental change as organizational objective, mutually beneficial relationships with stakeholders, and progressive interaction with markets, competitors, and industry institutions (Haigh & Hoffman, 2012). Other than sector-based differentiations, various studies have identified different features, measures, or dimensions of hybridity. For instance, Santos et al., (2015) identified two key dimensions that may differ in social hybrids; the value spillover and the level of overlap between customers and beneficiaries. Based on those variables they created a matrix to describe the four different types of social hybrid organizations. In doing so they describe how these different types of hybrids can be managed to avoid the risk of mission drift and better achieve economic sustainability. In their study Mair et al. (2015) address how hybrid organizations combine different institutional logics and in what way hybrids create their governance structures and practices, and describing the mechanisms that determine organizational resource use, in the processes of evolving the organization and resolving any conflicts between stakeholders.

1.2.2 Rural sustainable development and resilience

In the context of urbanization and the resulting rural decline with its accompanying rural depopulation and reduction in the diversity and quality of services available to rural communities, the term rural development becomes important (Li et al., 2016). In addition, Drolet (2012) states that other challenges like climate change are not only global or national issues but impact local economies and development. This implies that all disasters are first and foremost, at least from a short-term perspective, local and show the need for local capacity to meet these challenges (Drolet, 2012). Local development does not distinguish between urban and rural and can be defined as development “at a local scale with the aim of addressing local concerns, adding value to local resources and mobilizing local actors” (Moseley, 2003,

4 p. 7). Rural areas can be defined as areas with low population density, scattered villages, and small towns (Moseley, 2003). Another definition describes rural areas as “isolated areas away from more dynamic centers of activity that are set aside from centers of decision making, with economic and social structures closely dependent on agricultural activity” (Schouten et al., 2012, p. 166). Rural areas can also be described as social-ecological systems with social, economic, and ecological characteristics. Rural development can, therefore, be defined as “local development as nuanced by rurality” (Moseley, 2003, p. 7). Hobbes (2010) focuses specifically on social equity when it comes to rural development. Sustainable rural development merges sustainability and development goals, which can also be translated into the People-Profit-Planet approach of sustainable development (Hobbes, 2010). In the context of rural development, “People” stands for the protection of basic needs fulfillment. “Profit” can be translated into system-level economic growth, supported by opportunities for local value addition and effective investment. “Planet” in the context of rural development stands for biodiversity conservation and sustainable land use (Hobbes, 2010). Still, according to Schouten et al. (2012), rural areas experience problems in achieving sustainable development. In order to respond to unpredictable challenges like climate change, rural decline, resource depletion, and shifting markets, rural communities need the capacity to invest in their future – sustainability (Hobbes, 2010). Resilience thinking takes the unpredictable future into account and therefore offers a helpful framework for the management of rural changes. A resilient social-ecological rural system has the capacity to react to external challenges, while it is still able to provide the services and goods that support the quality of life (Schouten et al., 2012).

In line with Schouten et al.’s (2012) definition of rural areas and their dependency on agricultural activity, the focus of previous research on rural sustainable development and resilience is primarily in the context of agriculture and food production (Horlings & Kanemasu, 2015; Li et al., 2016; Tisch & Galbreath, 2018; McManus et al., 2012; Schouten et al., 2012; Herman, 2015; Hennebry, 2019; Gobattoni et al., 2015; Drolet, 2012). Tisch and Galbreath (2018) claim that resilience becomes especially important for agriculture when it comes to frequent extreme weather events as a result of climate change. Another stream of literature focuses on tourism (Quaranta et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016) and one on energy production (Horlings & Kanemasu, 2015). An example mentioned by Horlings and Kanemasu (2015) is the Scottish Shetland Islands. While currently dependent on oil and low-value mass production in fisheries and agriculture, they explore building resilience and environmental sustainability through a multi-sectoral high-quality food production with regional and niche market branding, in addition to their potential for renewable energy resources. Key drivers behind the potential change are the foreseeable end of oil resources and the problematic environmental and socioeconomic results of high-volume low-value food production and agriculture (Horlings & Kanemasu, 2015). According to Quaranta et al. (2016), tourism can revitalize the economies of rural areas through triggering processes of agricultural diversification. Tourism in rural areas is crucial because of its possibility to integrate and valorize territorial resources while promoting local community participation in the development process (Quaranta et al., 2016).

1.2.3 Importance of place and agency

Two important factors that affect resilience in rural development can be identified in previous research. The first being the importance and sense of place and/or community (Horlings & Kanemasu, 2015; Markantoni et al., 2019; Quaranta et al., 2016; Tisch & Galbreath, 2018; Schouten et a., 2012; Moseley, 2003; Maclean et al., 2014; Norris et al., 2008; McManus et al., 2012). The second factor is government and policy support for local action, which translates into the importance of agency (Horlings & Kanemasu, 2015; Li et al., 2016; Markantoni et al., 2019; Drolet, 2012; Wilson et al., 2018; Schouten et al., 2012; Moseley, 2003; Hobbes, 2010; Maclean et al., 2014; Norris et al., 2008). Markantoni et al. (2019) stress that valuing the local environment and nature are key factors for communities to strive to enhance the surroundings of their community and creating an attractive place to live. Strong community ties and the promotion of a greater sense of community are highly important for building strong community resilience (Quaranta et al., 2016). Research also shows that deep, local embeddedness and the resulting experience in local farming builds adaptive capacity and the development of resilience to adapt to stresses caused by extreme weather events (Tisch & Galbreath, 2018). These social ties of farmers within one community prove to be significant for resilience because the facilitated the exchange

5 of specific knowledge useful for adapting to weather-related events (Tisch & Galbreath, 2018). Schouten et al. (2012) also stress how strong connections within rural communities build capacity to respond to disturbances and shocks. A place-based approach becomes important in the context of rural diversity (Horlings & Kanemasu, 2015). In Horlings and Kanemasu’s (2015) example of the Shetland Islands, the individual characteristics of the region are even highlighted in a place-based brand summarized by the phrase “pride of place”. This goes in line with Moseley (2003) who describes adding value to local resources as a strategy for rural development. The importance of place is even highlighted in the European LEADER program, where the community is seen as central to local development and the territorialization of development initiatives is a key element (Moseley, 2003).

Horlings and Kanemasu (2015) mention the importance of effective mobilization and cultivation of social capital for rural development. This is linked to the second research stream of factors that affect resilience in rural development – government and policy support for local action or the importance of agency. In their study, Li et al. (2016) show the effectiveness of bottom-up initiatives in rural development with a strong leadership shown by local committees or self-organized actions from stakeholders. They also stress how structural societal conditions like power relations, decision-making processes, mechanisms of resource allocation, access to diverse services like education impact the local resilience-building capacity (Li et al., 2016). Markantoni et al. (2019) call for a change of the role of governments, from providers to facilitators and enablers. Building adaptive capacity for rural community resilience requires appropriate mechanisms at the local level with the right resource support (Markantoni et al., 2019). Drolet (2012) stresses the importance of government involvement and support with a range of policy and program approaches. However, according to Wilson et al. (2018), such policies need to be realigned to local needs instead of being top-down without taking local circumstances into account. This goes in line with Schouten et al. (2018) who’s findings show that the “execution of detailed policies at the national level suppresses the role and influence of lower layer governmental institutions” (ibid., p. 170). The importance of agency is also highlighted in the European LEADER program, where bottom-up approaches, active participation of community members, and local needs and resources embedded in local action plans are highly important (Moseley, 2003). According to Moseley (2003), “rural development can only be pursued successfully at the local level, none of them is more important than local development, which involves bringing to bear the full range of local resources, human and material, to resolve identified concerns” (ibid., p. 1).

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of the research is to explore how local rural communities can use hybrid organizations to drive sustainability and build resilience. The study also aims to theoretically contribute with increased knowledge regarding the characteristics of resilience and sustainability-driven hybrid organization for local rural development.

1.3.1 Research questions

This research aims to address the following questions:

1. How can local rural communities drive sustainability and build resilience with hybrid-organizations?

2. How can a resilience and sustainability-driven hybrid organization be characterized?

To get increased understanding and answer the research questions, this study looks at the hybrid organization Röstånga Tillsammans as a case.

6

1.4 Layout

The thesis is divided into six sections: (i) introduction, (ii) theoretical framework, (iii) research design, (iv) analysis, (v) discussion, and (vi) conclusion. The first chapter provides background to the research, previous literature on hybrid organizations, resilience and rural development, and the research purpose. The second chapter presents our theoretical framework, which is divided into three parts: sustainable development (2.1), the concept of hybrid organizations (2.2), resilience (2.3), and the preliminary framework for resilience and sustainability-driven hybrids (2.4). Chapter 2.2.1 describes which hybrid model this research focuses on – the sustainability-driven hybrids. Chapter 2.3.1 gives general implications about resilience and its connection to sustainability, 2.3.2 gives a detailed definition of community resilience and 2.3.3 describes characteristics of community resilience. Chapter 3 presents the design of the research, introducing the case study of Röstånga Tillsammans and Röstånga Utvecklings AB, selected data collection and analysis methods, considerations of validity and reliability and finally the research limitations. Chapter 4 analyzes the results from our empirical research structured according to the preliminary theoretical framework described in 2.4. Chapter 5 discusses the findings from our primary research on the basis of the preliminary theory. Finally, chapter 6 summarizes the findings and provides further research recommendations and limitations.

7

2 Theoretical framework

The following chapter aims to first present the general theory about sustainable development, hybrid organizations, and resilience. Secondly, we connect the concepts of sustainability-driven hybrids and community resilience and from that derive a preliminary framework upon which the analysis in chapter 4 is based.

2.1 Sustainable development

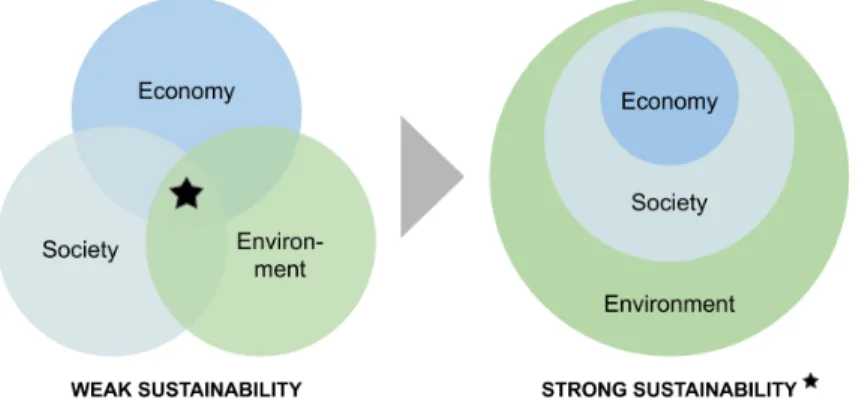

Sustainable development is not a new phenomenon and already back in 1972 with the release of ‘Limits to growth’ the debate concerning earth’s ecological and social limits to economic growth emerged (Ekins, 1993). As mentioned in the background the definition most often used for sustainable development is taken from the Brundtland report: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987, p.16). Sánchez et al. (2013, p. 2) further elaborate on the definition and describes how “Sustainable development implies the preservation of the earth‘s ability to sustain life in all its forms, based on democratic principles, gender equality, a state based on the rule of law, and respect for fundamental rights, including those of freedom and equal opportunities, in order to achieve a continuous improvement in the quality of life and well-being of the planet‘s present and future inhabitants”. The purpose of the Brundtland report was to explore the connections between economic growth, social equity, and environmental degradation, to generate policies that integrated the three aspects. The concept of evaluating the three aspects of economic, social, and environmental sustainability developed into the framework ‘triple bottom line’ (TBL). Over the last decade, many organizations and governments have incorporated the TBL and sustainability goals to address sustainability issues. The most important and significant globally spread goals are the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), created by the United Nations in 2015 and adopted by all UN member states. The 17 SDGs are all integrated and recognizes that sustainable development needs to balance economic, social, and environmental sustainability. The aim of the SDGs is to “end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity by 2030” (United Nations, 2020). Yet, some scholars and activists criticize that mainstream definition of sustainable development because of the oxymoron of continuous economic growth on a planet with limited resources and advocates strong rather than weak sustainability (Elkington, 2018; United Nations, 2019; European Environmental Bureau, 2019). Figure 1 shows the concept of strong sustainability which acknowledges that society operates within the planets ecological boundaries and that the current economic system is created within our society and do not trade-off between economic, ecological, and social systems (Ekins et al., 2003).

Figure 1 Weak vs. Strong Sustainability (Derived from Ekins et al., 2003)

2.2 Hybrid organizations

Because of the inherent hybrid nature of hybrid organizations, various scholars have defined hybrid organizations in different ways, and some even argue that all organizations may have some element of hybridity (Grossi et al., 2017). Schmitz and Glänzel (2016) identified three different streams of research defining the concept of hybrid organizations. They include the hybridity as partnerships and

8 collaborations between markets and hierarchies, for example, networks of firms, alliances, or cooperatives. Secondly hybrid organizations as a combination of public and private organizations, that have both a public and a market orientation. The third explanation, which also seems most prominent in literature, focuses on hybridity as the combination of economic and social goals (Boyd, 2009; Dees & Anderson, 2003) and/or environmental goals (Holt & Littlewood, 2015). Boyd (2009) describes how hybrids blur the line between nonprofit and for-profit organizations as they equally emphasis their common-good mission and their financial performance. Dees and Anderson (2003, p. 18) define that “Hybrid organizations, as we are using the term, are formal organizations, networks or umbrella groups that have both for-profit and nonprofit components”. Therefore hybrids do not fit into one ideal type of organization such as the corporation, the political organization, or the non-governmental organization, but is rather characterized by a mix of operational logics and a blend of traditional organizational structures (Alexius & Furusten, 2019a). Because of this, it is understood that hybrids are easily adapted to managing colliding worlds at institutional intersections and offer better opportunities for innovation (Alexius & Furusten, 2019a). Mair et al. (2015) identified three attributes of hybrid organizations: (i) a variety of stakeholders, (ii) the pursuit of multiple and often conflicting goals, and (iii) engagement in diverse or inconsistent activities.

Hybrid organizations exist in all sectors across the globe and although they can be any size, they are typically micro or small- to medium-sized. What may differ between hybrids are the institutional forces that shape them and the value that they aim to create (Holt & Littlewood, 2015). The context and environment will influence the hybrids business model, revenue stream, leadership, and governance, and further affect their goals (Holt & Littlewood, 2015). In the third sector complex hybrid organizational forms arise as charities, voluntary, and community organizations face different challenges in forms of tasks, legitimacy, or resource environments. (Skelcher & Smith, 2015), but also emerge as these third sector organizations find new revenue sources to fund their social mission. According to Alter’s hybrid spectrum organizations can be placed along the spectrum, depending on the level of mission vs financial motives and the level of stakeholder vs shareholder accountability (Boyd, 2009). In the spectrum between traditional nonprofits and traditional for-profits, he identifies nonprofits with income-generating activities, social enterprises, socially responsible businesses, and corporations practicing socially responsible. While hybrid organizations are similarly characterized to concepts such as “social enterprises” some authors argue that hybrid organizations is a less politically tainted concept and a more neutral term (Alexius & Furusten, 2019a) that also better reflect the heterogeneity of the legal forms, mission, and context that the organizations operate within (Holt & Littlewood, 2015).

Hybrid organizations are most often registered as for-profit businesses and operate with competitive products or services in a market-oriented manner. Any decisions or actions taken are linked to the organizations’ common-good mission and need to contribute positively to this (Boyd, 2009). Because these organizations are mission-driven they may value non-financial performance explicitly and while they need to be profitable to sustain, they may regularly underperform in the financial are in relation to the general market performance. Hybrid organizations often prefer financial and managerial autonomy (Haigh & Hoffman, 2011) and are generally privately owned by a connected set of shareholders that buy into the mission rather than the open financial market (Boyd, 2009). These entities are often controlled by a group of closely connected individuals, either family or personally connected (Boyd, 2009).

2.2.1 Sustainability-driven hybrid organizations

Stubbs (2017) identified one research stream of sustainable business models that originates from the hybrid business model literature and a second research stream that has its origin in corporate social responsibility. For this study, we have focused on the stream emerging from the research on sustainable hybrid models and have decided to use the ‘sustainability-driven hybrid business model’ (SDH), developed by Haigh & Hoffman (2012), as part of our framework, as we agree with Stubbs (2017 p. 302) that “to date, it is the most comprehensive discussion of the characteristics of a sustainable hybrid business model in the literature”. The sustainability-driven hybrid business model (SDH) encompasses three main objectives that distinguish hybrids from traditional organizations: social and environmental change as organizational objective; mutually beneficial relationships with stakeholders; and progressive interaction with markets, competitors, and industry institutions (Haigh & Hoffman, 2012).

9 Sustainability-driven hybrids challenge the current norms about economic growth, profit, nature, and society and go beyond mainstream corporate sustainability by incorporating a focus on doing ‘more good’ rather than doing only ‘less harm’, in regards to environmental and social impacts (Haigh & Hoffman, 2014). The SDH have nine characteristics including; socially and environmentally embedded mission, longer time horizons, positive and engaged leadership, creation of mutually beneficial relationships with stakeholders, progressive interaction with markets, competitors and industry institutions, challenging the need for economic growth, internalizing social and natural contexts, valuing nature beyond its resource value, and setting aside the notion of profit as the dominant objective of the firm (Haigh & Hoffman, 2012).

Hybrids use the market to benefit their social and environmental goal but “challenge the notion of trade-offs between economic, ecological, and social systems and instead of developing business models that develop synergies between them, hybrids allow for-profit activities to be undertaken in ways that address sustainability issues” (Haigh & Hoffman, 2014 p. 227). Due to their mission and sustainable development practices hybrid organizations often operate on a longer time scale resulting in a slower, steady, or limited growth compared to traditional profit-driven businesses. A majority of hybrid leaders are participative or transformational in their leadership style. The leaders of sustainability-driven hybrid organizations embody the organizations’ strong social and environmental missions and their everyday activities and approaches to management reflect those values. The style of leadership is an example of positive and engaged leadership, characterized by their ethics, participative management, and the drive toward achieving the organizational goals (Haigh and Hoffman, 2012).

Hybrids operate locally and create close relationships based on mutual trust and compassion with communities by employing local people, involving them in decision-making, training them in specific sustainable techniques, and paying above average salary to enable a better quality of life (Haigh & Hoffman, 2012). These close relationships enable hybrid organizations to positively impact local and social-environmental systems, that in return provide high-quality resources needed to meet market expectations and be economically sustainable. Hybrids are an example of a compassionate organization, by processes of participative management, diversity representation, and task autonomy, which creates a sense of family, expressing empathy, and building trusting relationships within the organizations. Furthermore, by challenging the presumed need for perpetual economic growth and valuing nature beyond its resource value hybrids seek to act as an example in the market that other organizations might emulate in order to create beneficial change for society (Haigh & Hoffman, 2012).

2.3 Resilience

Not only have rural areas been exposed to simultaneous and interacting global stresses like climate change, but also to local change processes like urbanization, land abandonment and degradation, coastalization, and depopulation (Imperiale & Vanclay, 2016). As a reaction to these stresses and the resulting decline of rural areas, the term rural resilience has become popular in recent times (McManus et al., 2012). There has also been an implication of shifting rhetoric – from sustainability to resilience (Holt, 2014). Whereas sustainability assumes the maintaining of balance on the social, environmental and economic dimension, resilience takes a more critical approach to environmental crises assuming recurrent disruption and disequilibrium (Holt, 2014). Resilience highlights the need for flexibility and quick recovery. It is about adaptation and not risk mitigation (Holt, 2014). Resilience, therefore, implies an on-going change and transformation process which requires a more autonomous approach in local decision-making (Holt, 2014). In addition, the concept of resilience focuses explicitly on the challenges of humankind’s existence within ecological systems and therefore complements sustainability-thinking (Lerch, 2017). The embeddedness of humankind within ecological systems and the resulting challenges strongly link to the strong sustainability concept described in 2.1. Sustainability and resilience are inextricably linked, especially because sustainability is a key outcome of resilient ecological systems (Bec et al., 2018; Serfilippi & Ramnath, 2018). The concept of resilience is even articulated in Target 1.5 of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals: “By 2030, build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social and environmental shocks and disasters” (United Nations, 2015). According to Serfilippi and Ramnath (2018), “resilience programming should, therefore, incorporate normative sustainable thinking based on the outcome, and implementations should focus on long-term

10 program and policy impacts” (ibid., p. 651). Resilience, however, differs from sustainability in that it is not an end in itself but a means, a process to promote sustainability.

2.3.1 Resilience – general implications

The concept of resilience is rooted in the sciences of physics and mathematics and describes the “capacity of a material or system to return to equilibrium after displacement” (Norris et al., 2008, p. 127). This describes how a material bends and bounces back after it was stressed instead of breaking. More specifically, in physics, it is defined as “the speed with which homeostasis is achieved” (Norris et al., 2008, p. 127). As mentioned by Norris et al. (2008) and Berkes and Ross (2013), the concept of ecological resilience was first mentioned by Holling (1973), who’s view on resilience was inspired by physics and is based on “the observations of the dynamics of the boreal forest ecosystem, with its uncertainties, abrupt shifts, and renewal cycles” (Berkes & Ross, 2013, p. 7). In ecology, resilience is characterized by the ability for self-renewal and maintenance in the face of disturbance and to absorb the aforementioned, while retaining basic function and structure (McManus et al., 2012; Berkes & Ross, 2013; Lerch, 2017). This concept is not easily adapted to human socio-ecological settings but is still increasingly used to identify how communities and organizations react to external stressors like economic, social, and environmental challenges (Serfilippi & Ramnath, 2018). In contrast to some other interpretations that view resilience as resistance, this paper views resilience as the ability of communities to change and transform over time to achieve long-term resilience and sustainability (Serfilippi & Ramnath, 2018). Therefore, resilience can be described as a change management approach (Bec et al., 2018). Since change, in general, is inevitable, resilience as a management approach does not focus on avoiding change but rather on how change can be leveraged to achieve the most desirable and sustainable outcome (Bec et al., 2018). This is the ideal perspective for regional rural development and encompasses multiple aspects including institutional, economic, social, and environmental dimensions (Bec et al., 2018).

Hennebry (2018) defines resilience as “the ability to adapt in anticipation of, or response to, shocks” (ibid, p. 100). Therefore, resilience in social and economic contexts can be defined as “the ability to embrace change, with a capability to adapt seamlessly to largely exogenous events in a form termed stable adaptation” (McManus et al., 2012, p. 21). Resilience-thinking offers a framework to deal with processes of change, reorganization, and transformation, while being able to retain the same function (Herman, 2015). Rural decline and the resulting social and economic challenges for rural communities can be encompassed in the process of building community resilience, which is important for positive community development. Community resilience can, therefore, play a key role in strengthening rural areas, because it implies healthy and socially sustainable transformative changes at the community level (Imperiale & Vanclay, 2016). It is also an opportunity for said communities as they can actively and dynamically react to exogenous events rather than being passively exposed to unmanageable external forces (McManus et al., 2012).

2.3.2 Community resilience – a definition

Even though it raises the same concerns, the variation in the meaning of community further complicates the concept of resilience. Norris et al. (2008) describe communities as complex, built, natural, social, and economic systems that influence each other. Throughout the literature, two general paths for community resilience can be identified. Whereas the first one is concerned with the prevention of disaster-related problems of community members, the second path is more concerned with community resilience that “describes effective organizational behavior and disaster management” (Norris et al., 2008, p. 128). In resilience-thinking, communities, and ecosystems they make use of are seen as integrated, interdependent, complex, and adaptive social-ecological systems (Lerch, 2017; Berkes & Ross, 2013). Adaptive capacity in this context is a combination of strengths, attributes, and resources available to a community “that can be used to prepare for and undertake actions to reduce adverse impacts, moderate harm, or exploit beneficial opportunities” (Serfilippi & Ramnath, 2018, p. 649; IPCC, 2012). This implies that community resilience is more about building and identifying a community’s strengths and continually change and adapt rather than focusing on overcoming deficits (Berkes & Ross, 2013). This goes in line with Magis’ (2010) definition of community resilience as “existence, development, and engagement of community resources by community members to thrive in an

11 environment characterized by change, uncertainty, unpredictability and surprise” (ibid., p. 401). Martin and Sunley (2015) define resilience as “the capacity of a regional or local economy to withstand or recover from market, competitive and environmental shocks to its developmental growth path, if necessary by undergoing adaptive changes to its economic structures and its social and institutional arrangements, so as to maintain or restore its previous developmental path, or transit to a new sustainable path characterized by a fuller and more productive use of its physical, human and environmental resources” (ibid., p. 13). Community resilience can also be defined as “the way in which individuals, communities and societies adapt, transform, and potentially become stronger when faced with environmental, social, economic or political challenges” (Maclean et al., 2014, p. 146). All these definitions focus on the adaptive capacity in the face of change.

The concept of adaptive capacity implies a focus on short and long-term planning to identify risks and assess the community’s ability to address future changes (Norris et al., 2008). In addition, it is the capacity of a community to influence resilience through social networks and learning (Berkes & Ross, 2013). The building of community resilience on the community-level makes practical sense because of how the political system is structured. It gives room to react faster, more flexibly, and gives local community decision-making power over issues that most affect them (Lerch, 2017). This leads to another highly important requirement for community resilience – agency (Berkes & Ross, 2013). Active agency of communities in community resilience implies that communities are primarily responsible for their own well-being and that they have the primary decision-making power (Magis, 2010; Lerch, 2017). As community resilience can be developed, rural areas experiencing some of the already mentioned challenges are well served to develop it (Magis, 2010).

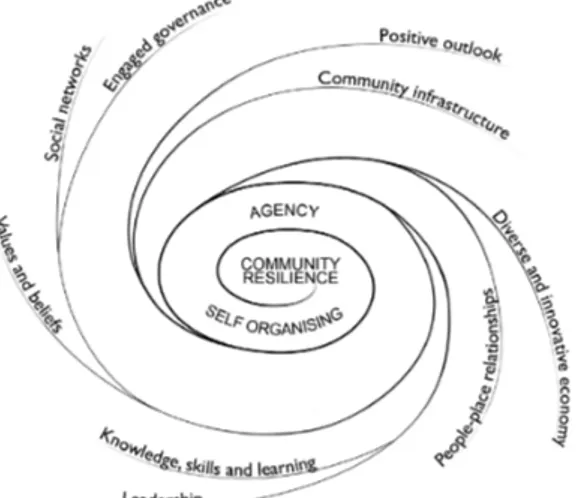

2.3.3 Characteristics of community resilience – an integrated concept

Communities cannot control all of the external conditions that they are affected by. They are, however, able to change and develop conditions that increase their resilience (Berkes & Ross, 2013). Maclean et al. (2014) developed six characteristics of social resilience, namely: (i) knowledge, skills, and learning; (ii) community networks; (iii) people-place connection; (iv) community infrastructure; (v) diverse and innovative economy, and (vi) engaged governance. These characteristics will strengthen the community’s adaptive capacity, their ability to transform and become stronger when faced with social, economic, and environmental challenges (Maclean et al., 2014). Berkes and Ross (2013) developed these characteristics and added (vii) values and beliefs, (viii) leadership, and (ix) a positive outlook including readiness to accept change. In the integrated concept for community resilience (Figure 2) these strengths are drawn together through the process of agency and self-organizing to develop community resilience (Berkes & Ross, 2013). In the interest of simplification for reasons of comparison, this paper will focus on the proposed characteristics by Maclean et al. (2014). It can also be argued that the additional characteristics by Berkes and Ross (2013) can be integrated within Maclean et al.’s (2014) framework.

12

Knowledge, skills, and learning refer to both the individual and the group’s capacity to respond to local

needs and issues. It not only includes knowledge partnerships but technology and innovation and skills development and consolidation (Maclean et al., 2014). In addition to knowledge sharing amongst stakeholders, Bec et al. (2018) also mention the importance of diversification in opportunities for education, training, and learning as important characteristics. Furthermore, the combination of traditional and scientific knowledge leads to community resilience building (Chiang et al., 2014). The characteristic of community or social networks draws strongly from the concept of social capital and includes “all social processes and activities that support people and groups in a place” (Maclean et al., 2014, p. 149). It is important to create an identity and vision. When it comes to change, networks are not only helpful in providing the necessary support and identifying opportunities, but also enable further network building (Maclean et al., 2014). Reinforcing and building new community relationships increases social capital which in turn enables people to coordinate their activities with the aim of creating mutual benefits and mitigating opportunistic behavior (Meadows, 2008; Gobattoni et al., 2015). Norris et al. (2008) characterize networks by “reciprocal links, frequent supportive interactions, overlap with other networks, the ability to form new associations, and cooperative decision-making processes” (ibid., p. 138).

Especially when it comes to community resilience, the characteristic of people-place connection is a fundamental element for community resilience (Mclean et al., 2014; Norris et al., 2008). This characteristic acknowledges human-environment interdependencies and connections, encompasses holistic management approaches, and the concept of stewardship (Maclean et al., 2014). There are two main themes connected to people-place connection: (i) connection to place and (ii) sustainable livelihood development. Human identity is strongly connected to a community including relationships, shared experiences, history, culture, smells, and sounds – general emotional associations with the sense of home (Lerch, 2017). The strong connection to a place creates passion and commitment to protect and preserve the surrounding area and drives communities to build and enhance adaptive capacity to cope with change (Maclean et al., 2014). In addition, a strong sense of belonging contributes to a strong sense of community, which in turn has the potential for resilience (McManus et al., 2012). A sense of community can be described as a process of bonding with other members of the same group and includes shared values and mutual concerns (Norris et al., 2008). Research even highlights that the possibility of resilience is higher when members of a community identify themselves with the said community (McManus et al., 2012). The people-place characteristic also integrates the values and belief characteristic proposed by Berkes and Ross (2013) as the strong connection to a place and community influence an individual’s values and beliefs.

Community infrastructure is required for the support of a community’s needs and actions and

encompasses diverse services and facilities such as health services, community centers, appropriate transport options, local cultural activities, and so forth (Maclean et al., 2014). Community infrastructure also plays an important role in improved local economic development. Bec et al. (2018) also mention the need for diversification in opportunities for education, training, and learning. Diverse and innovative

economy stresses the need for a regional economy that is made up of different industries and services

and has a supportive structure for new and exciting opportunities (Maclean et al., 2014). Norris et al. (2008) highlight the dependency of community resilience on economic diversity. A strong, diverse, and local economy also reduces the vulnerability of a community and is important for the ability to cope with change (Maclean et al., 2014). Engaged governance encompasses collaborative approaches to regional decision making (Maclean et al., 2014). Stakeholders should not only have the opportunity to participate but also to get some responsibility in community resilience building (Lerch, 2017). In addition, as proposed by Berkes and Ross (2013) engaged governance also includes engaged leadership. Especially transformational leadership shows important characteristics for engaged governance. A transformational leader sets out to empower, is a strong role model for their followers, creates a vision, and can build trust and foster collaboration amongst people (Northouse, 2016). The feeling of empowerment plays a crucial role to motivate community members to work together towards solving common problems (Imperiale & Vanclay, 2016). This characteristic can also be found in the factor of agency and self-organizing. Community resilience needs to be grounded in human agency, mutual trust, and shared willingness to work for the common good of the community (Norris et al., 2008). The shared willingness also connects engaged governance to the last characteristic proposed by Berkes and Ross (2013), a positive outlook on the future including readiness to accept to change.

13

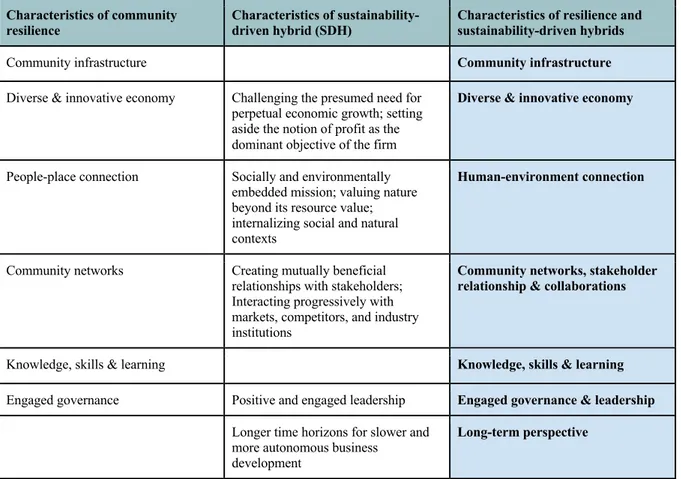

2.4 Preliminary framework for resilience and sustainability-driven hybrids

In this section, we attempt to identify the core set of ideas from the theory on hybrid organizations and resilience by linking the two strands of literature. For the purpose of this research, we developed our theoretical framework for assessing hybrid organizations from the perspective of sustainability and resilience by putting together the framework by Haigh and Hoffman (2012) on sustainability-driven hybrid organizations and the framework on characteristics of resilience by Maclean et al. (2014). We have found much overlap within the characteristics. Six characteristics of community resilience match with eight of nine characteristics of sustainability-driven hybrids. Table 1 illustrates how different characteristics match. The left column shows the characteristics of community resilience, the middle column shows the matching characteristics of sustainability-driven hybrids and the right column shows our developed characteristics of resilience and sustainability-driven hybrids. They include (i) community infrastructure, (ii) diverse and innovative economy, (iii) human-environment connection, (iv) community networks, stakeholder relationships and collaboration, (v) knowledge, skills, and learning, (vi) engaged governance and leadership, and (vii) long-term perspective. These seven characteristics of resilience and sustainability-driven hybrids will be used to analyze the following case and answer the research questions. For further definition of the characteristics of the framework see Appendix I.

Table 1 Preliminary framework for resilience and sustainability-driven hybrid-organizations Characteristics of community

resilience Characteristics of sustainability-driven hybrid (SDH) Characteristics of resilience and sustainability-driven hybrids

Community infrastructure Community infrastructure

Diverse & innovative economy Challenging the presumed need for perpetual economic growth; setting aside the notion of profit as the dominant objective of the firm

Diverse & innovative economy

People-place connection Socially and environmentally embedded mission; valuing nature beyond its resource value; internalizing social and natural contexts

Human-environment connection

Community networks Creating mutually beneficial relationships with stakeholders; Interacting progressively with markets, competitors, and industry institutions

Community networks, stakeholder relationship & collaborations

Knowledge, skills & learning Knowledge, skills & learning Engaged governance Positive and engaged leadership Engaged governance & leadership

Longer time horizons for slower and more autonomous business

development

14

3 Research design

After considering the overall purpose of the study and the theoretical framework, the following chapter will define our choice of research design. Within this chapter we discuss the case study approach, the scope of the research, the data collection and analysis methods, as well as reliability, validity, ethical considerations and research limitations.

3.1 Case study research

Regarding the lack of previous research and based on the nature of the research questions, the approach is of inductive qualitative nature. According to 6 and Bellamy (2012), inductive research is used to develop a theory “from a position in which we have no real idea of what might turn out to be plausible, relevant or helpful about the subject of interest” (ibid., p. 76). The researcher as the primary instrument for data collection and the search for meaning and understanding are key factors of qualitative research (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). Our intention is to understand the social phenomena linking the use of sustainability-driven hybrid-organizations with characteristics of community resilience in the rural context. Because we connect two concepts in a new way, we argue that the approach is of inductive nature. The preliminary framework that we developed will be used as a form of analysis to organize the data. As the community of Röstånga with its NGO Röstånga Tillsammans (RT) and the community company Röstånga Utvecklings AB (RUAB) present naturally occurring cases, we suggest producing an exploratory single case study. The aim of exploratory research is to contribute with new knowledge or add to existing knowledge and is associated with a relatively unstructured and open approach which is advantageous for qualitative research (Brown, 2006). According to Kohlbacher (2006), case study research matches best with the intention to investigate a complex issue, which in our case is the use of a resilience and sustainability-driven hybrid-organization for rural sustainable development. Case studies are traditionally used to contribute to scientific knowledge of, amongst other things, organizational and social phenomena (Yin, 2013). Furthermore, they are relevant when the purpose of the research is to answer a “how” or “why” question about a contemporary, naturally occurring phenomena, where it is not possible to disconnect the phenomenon’s variables from their context, which is the case with Röstånga (Yin, 2013).

In order to answer the research questions, this case study is build upon the twofold case study approach of Yin (2013). First, “a case study is an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon (the case) in depth and within its real-world context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context may not be clearly evident” (ibid., p. 16). Second, “a case study inquiry copes with the technically distinctive situation in which there will be many more variables of interest than data points and as one result, relies on multiple sources of data needing to converge in a triangulating fashion, and as another result benefits from the prior development of theoretical propositions to guide data collection and analysis” (ibid., p. 17). Case studies offer more detailed, rich, and complete analysis for the unit of study than other qualitative approaches (Flyvberg, 2011). Therefore, a case study research design facilitates the intensive study and in-depth analysis of the social phenomena of Röstånga and gives us access to underlying causal mechanisms. An important difference between other qualitative methods and case study research is the role of theory development prior to data collection (Yin, 2013). The preliminary theoretical framework is critical for defining and interpreting units of analysis and linking the data to the propositions (ibid.). Through an inductive approach, we have developed a theoretical framework linking the concepts of sustainability-driven hybrid-organizations and characteristics of community resilience, that serves as a basis for our analysis and interpretation of our data. In addition, the preliminary theoretical framework plays a crucial role in the generalizability of case study research (Yin, 2013).

3.1.1 Object of case study: Röstånga Tillsammans

The most important defining characteristic of a case study is the object of study – the case – which occurs in a bounded context (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). In contrast to other qualitative methods, which focus on the topic of analysis, a case study is characterized by the unit of analysis (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015; Yin, 2013). A case study is therefore an in-depth study of a bounded system. Silverman (2014)

15 calls for purposive sampling when it comes to case study research because this allows the researcher to choose a case based on theory, features, or processes in which they are interested in. In addition, “the desired case should be some real-life phenomenon that has some concrete manifestation [and] cannot simply be an abstraction, such as a claim, an argument or even a hypothesis” (Yin, 2013, p. 34). Dees and Anderson (2003) define hybrid organizations as “formal organizations, networks, or umbrella groups that have both for-profit and nonprofit components” (p. 18). Based on the requirements for case selection, our research questions, and the definition of hybrid organizations, we choose to study the case of Röstånga.

Röstånga is a village located in southern Sweden, in the southeast corner of the northwest county of Skåne. Located just on the southeast of the natural park Söderåsen it is the smallest village of Svalövs municipality and has a population of 1500 (Svalövs kommun, 2016). Back in 2009 citizens of the village and local associations got together to discuss ways to work together to develop the rural area. The aim was to stop the negative demographic and economic development of their community and to prevent the local school from closing down. Different development groups evolved, covering areas including housing, nature, culture, and enterprise. To formalize and structure the process, RT was founded. RT is registered as a nonprofit organization and has the aim of initiate, drive, and coordinate development projects in Röstånga and the surrounding area. In 2011 RT took the next step and founded the for-profit shareholding company RUAB focusing on property development. The hybrid organization made up of a charitable initiative and a commercial development company combines economic and social goals. The nonprofit initiative is and remains the majority owner of the development company in order to guarantee comprehensive transparency and openness.

3.2 Data collection and analysis methods

The following chapter outlines the selected data collection and analysis methods, that we considered relevant for the case study: (i) semi-structured interviews, (ii) document analysis, and (iii) qualitative thematic analysis. Due to the current COVID-19 pandemic, we are unfortunately restricted in the use of further data collection methods like focus groups or observation. The use of multiple data collection methods is usually a major strength of case study research (Yin, 2013). In our case, the use of two sources of data and our strong foundational theoretical framework create an in-depth understanding and a broader, holistic outlook of the studied issue (Silverman, 2014). According to Yin (2013), this also contributes to the overall quality of our case study and results in more convincing findings or conclusions.

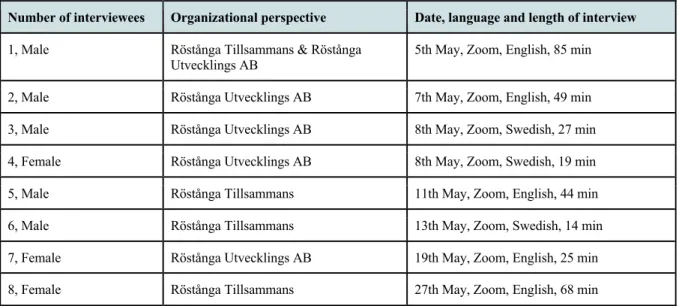

3.2.1 Semi-structured interviews

In contrast to everyday conversations, a research interview has a purpose and a structure (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). Qualitative interviewing in general and semi-structured interviews in particular are especially helpful in assessing individuals’ perception and experiences in a certain situation or process, which cannot be observed in a formal questionnaire (Silverman, 2014). They provide a rich source of data about people’s experiences, views and opinions (ibid.). In contrast to structured questionnaires, semi-structured interviews resemble a more guided conversation (Yin, 2013). The open-ended questions are more flexibly worded which allows us to respond differently to each interviewee and their unique view on the situation (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). According to Silverman (2014), flexible open-ended questions make it possible to access interviewee’s views, understandings, opinions, and experiences, because it is likely to get a more considered response from the interviewee in contrast to closed questions. In addition, they leave room to further explore particular themes or responses.

Semi-structured interviews are based on an interview guide, which includes both more and less structured questions (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). It includes questions focused on specific data required from all respondents, but also questions, that are more flexibly used to explore emerging themes if the researcher deems them necessary (ibid.). The interview guide also does not predetermine the wording or order of the questions, which leaves room for the researcher to go with the flow of the conversation (ibid.). For this research, we based the interview guide (Appendix II) on our proposed theoretical framework. This allowed us to later guide the analysis with the framework and make sure, that the collected data is descriptive and helps in answering the research questions. This also goes in line with