MOHAMMAD H. AL-HARTHY

CROSS-CULTURAL

DIFFERENCES IN PATIENTS

WITH TEMPOROMANDIBULAR

DISORDERS-PAIN

A Multi-Center Study

MOHAMMAD H. AL -HARTHY MALMÖ UNIVERSIT CR OSS-CUL TUR AL DIFFEREN CES IN P A TIENT S WITH TEMPOR OMANDIBUL AR DISORDERS-P AIN DOCT OR AL DISSERT A TION IN ODONT OL OG YC R O S S - C U L T U R A L D I F F E R E N C E S I N P A T I E N T S W I T H T E M P O R O M A N D I B U L A R D I S O R D E R S - P A I N

Malmö University

Faculty of Odontology Doctoral Dissertation 2016

© Mohammad Al-Harthy 2016 Cover illustration: Ali Algarni ISBN 978-91-7104-704-5 (print) ISBN 978-91-7104-705-2 (pdf) Holmbergs, Malmö 2016

MOHAMMAD H. AL-HARTHY

CROSS-CULTURAL

DIFFERENCES IN PATIENTS

WITH TEMPOROMANDIBULAR

DISORDERS-PAIN

A Multi-Center Study

Malmö University, 2016

Faculty of Odontology

Department of Orofacial Pain and Jaw Function

This publication is available at: www.mah.se/muep

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... 9 SUMMARY IN ARABIC ... 12 POULÄRVETENSKAPLIG SAMMANFATTNING (SUMMARY IN SWEDISH) ... 15 PREFACE ... 18 THESIS AT A GLANCE ... 19 ABBREVIATIONS ... 20 1. INTRODUCTION ... 21 Temporomandibular disorders (TMD)...21Definition and prevalence ...21

Diagnosis of TMD ...21

Management of TMD ...22

Pain Sensitivity and TMD ...23

Pain Comorbidity and TMD ...24

Culture ...25

Culture and context ...25

Culture and pain sensitivity ...25

Culture and pain comorbidity ...26

Culture and TMD-pain patient’s beliefs in treatment ...26

2. HYPOTHESES ... 28

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS ... 30

Study centers and data collection (I–IV) ...30

Patients with TMD and TMD-free controls (I–IV) ...30

Ethical considerations (I-IV) ...31

Self-report questionnaires ...32

RDC/TMD (I-IV) ...32

Comorbid pain conditions questionnaire (III)...33

Survey of treatments received questionnaire (IV) ...33

Explanatory Model Form (IV) ...34

Experimental protocols ...34

Pressure pain measurements (II) ...34

Electrical stimulation tests (II) ...36

Translation of commands and instruments (I-IV) ...36

Statistical analysis (I-IV) ...37

5. RESULTS... 39

Subject and pain characteristics (I-IV) ...39

Pressure and electrical pain (II) ...42

Comorbid pain conditions (III) ...44

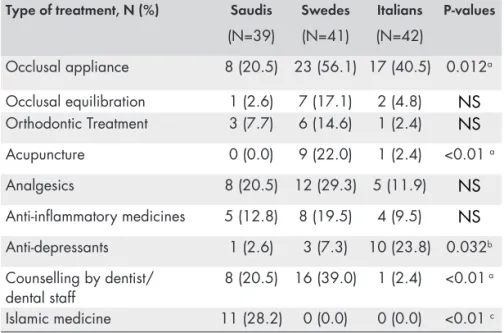

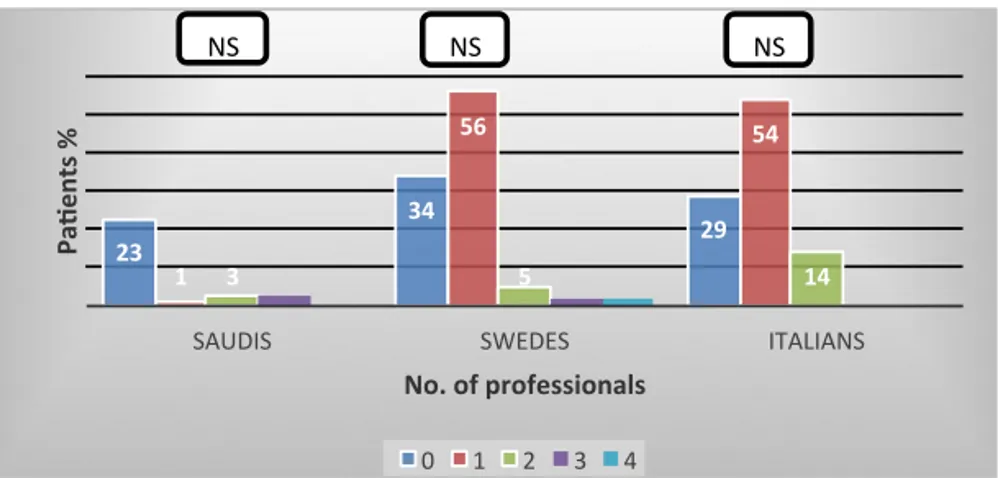

Treatments received and pain beliefs (IV) ...48

6. DISCUSSION ... 52

Culture ...53

Prevalence and gender ratio (I-IV) ...54

Age and education years (I-IV) ...54

RDC/TMD Axis I and Axis II (I-IV) ...55

Pain sensitivity (II) ...56

Pain comorbidities (III) ...58

Headache (I and III) ...59

Other pain comorbidities (III) ...61

Beliefs (IV) ...61

Treatment received (IV) ...62

Strengths and limitations (I-IV) ...65

7. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES ... 67

Future perspectives ...68

8. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... 70

9. REFERENCES ... 73

ABSTRACT

The overall objective of this thesis was to investigate patients with TMD-pain and TMD-free controls in three cultures (Saudi Arabia, Sweden, and Italy) to determine the influence of culture on and cross-cultural differences in pain prevalence and intensity, sensitivity to mechanical and electrical stimulation, pain-related disability for four comorbid pain conditions (back, head, chest, and stomach pain) in the last 6 months, and the type of treatment that patients with TMD pain received.

The specific aims were:

(i) To determine the frequency of TMD pain in Saudi Arabians (I).

(ii) To compare psychophysical responses to mechanical and electrical stimuli in female TMD patients and TMD-free controls, nested within each of three cultures (Saudi, Italian, and Swedish) (II).

(iii) To assess pain prevalence and intensity, and pain-related disability associated with comorbid pain conditions by testing for the interaction effect between three different cultures and case-status (III).

(iv) To assess the type of treatment that female patients with TMD-pain in three cultures received, and their beliefs about the factors that contribute to and aggravate TMD, as well as the factors that are important to include in TMD treatment (IV).

Study (I) material included 325 Saudi Arabian patients (135 males, 190 females) aged 20–40, who were referred to the Specialist Dental Center at Alnoor Specialist Hospital, Makkah and answered a history questionnaire. We offered a clinical examination to patients reporting TMD pain in the last month and assessment according to the Arabic version of the Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (RDC/TMD).

Of these patients, 58 (18%) reported TMD pain and 46 underwent clinical examination. All TMD pain patients had a diagnosis of myofascial pain, and 65% had diagnoses of arthralgia or osteoarthritis. The TMD-pain group reported high levels of both headaches/migraines in the last 6 months (93%) differing significantly (P < 0.01) from the TMD-pain-free groups.

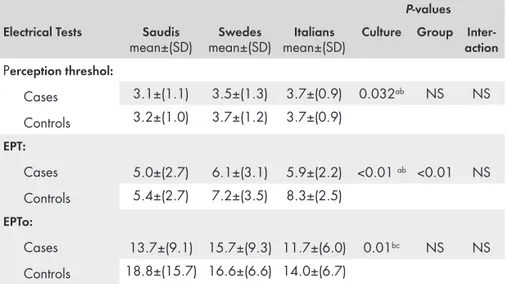

All pain group were suffering at least from one TMD subdiagnosis The TMD-pain group had high depression and somatization scores but low disability grades on the Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS). Studies (II-IV) compared 122 female cases of chronic TMD pain (39 Saudis, 41 Swedes, and 42 Italians) to equal numbers of age-matched TMD-free controls. The study (II) measured pressure pain threshold (PPT) and tolerance (PPTo) over one hand and two masticatory muscles, and electrical perception threshold, electrical pain threshold (EPT), and electrical pain tolerance (EPTo) between the thumb and index fingers. Italian females reported significantly lower PPT in the masseter muscle than the other cultures (P < 0.01) and in the temporalis muscle than Saudis (P < 0.01). Swedes reported significantly higher PPT in the thenar muscle than the other cultures (P = 0.017). Italians reported significantly lower PPTo in all muscles than Swedes (P < 0.01) and in the masseter muscle than Saudis (P < 0.01). Italians reported significantly lower EPTo than other cultures (P = 0.01). TMD cases reported lower PPT and PPTo than TMD-free controls in all three muscles (P < 0.01).

Cultural differences appeared in PPT, PPTo and EPTo. Overall, Italian females reported the highest sensitivity to both mechanical and electrical stimulation, while Swedes reported the lowest sensitivity. Mechanical pain thresholds differed more across cultures than did electrical pain thresholds. Cultural factors may influence response to type of pain test.

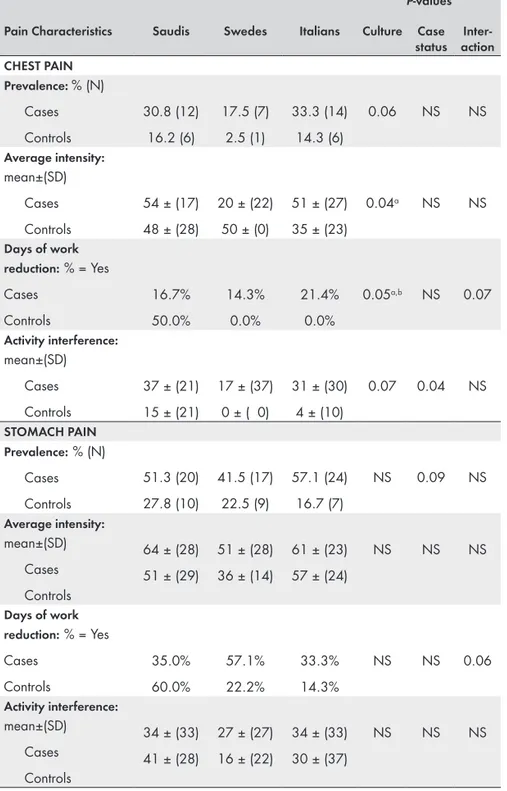

In Study (III), self-report questionnaires assessed back, chest, stomach, and head pain for prevalence, intensity, and interference with daily activities in the last 6 months. Logistic regression assessed binary variables and ANCOVA provided parametric data analysis, adjusting for age and education.

Back pain was the only comorbid condition that varied in prevalence across cultures; Headache was the most common comorbid pain condition in all three cultures; the average head pain intensity was lower, however, among Swedes compared to Saudis (P = 0.029). The total number of comorbid conditions did not differ cross-culturally, but the TMD group reported more comorbid conditions compared to TMD-free controls (P < 0.01). For both back and head pain, TMD cases reported higher average pain intensities (P < 0.01) and interference with daily activities (P < 0.01) than TMD-free controls. Among TMD patients, Italians reported the highest pain-related disability (P < 0.01).

This study indicates that culture influences the comorbidity of common pain conditions with TMD. The cultural influence on pain expression is reflected in different patterns of physical representation. Study (IV) compared patient characteristics, treatment beliefs, and type of practitioner advice received before referral for TMD treatment. Patients responded to a questionnaire that assessed treatments received, then completed an explanatory model form about their beliefs regarding which factors contribute to and aggravate TMD, and what factors are important for treatment to address.

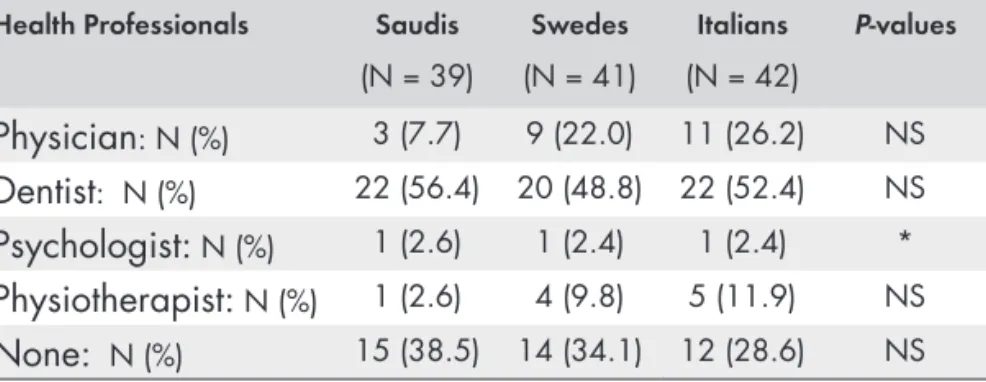

Of the various treatments, Swedes most commonly sought behavioral therapy and Saudis Islamic medicine (P < 0.01). Swedes received acupuncture and occlusal appliance therapy significantly more than Saudis (P < 0.01) or Italians (P = 0.012). Italians were significantly less likely than Saudis and Swedes (P = 0.042) to believe that TMD pain treatment should address behavioral factors.

Among Saudi, Italian, and Swedish females with chronic TMD pain, culture did not influence the type of practitioner consulted before visiting a TMD specialist or their beliefs about factors contributing to or aggravating their pain. Overall, the treatments patients received and beliefs about behavioral factors differed cross-culturally. Islamic medicine was fairly common among Saudis and acupuncture was

يبرعلاب ةلاسرلا صخلم

(SUMMARY IN ARABIC)

ملاآ ىلع تافاقثلا فلاتخا ريثأت ديدحتو ةنراقمو ةسارد وه ةلاسرلا هذه نم ماع لكشب فدهلا لباقم يف اهنم نوناعي نيذلا ىضرملا نم ةنيع يف يغدصلا كفلا لصفم ةمزلاتم تابارطضاو ةفلتخم نادلبو تافاقث ثلاث يف كلذو ،تابارطضلااو ملالآا هذه اهيدل تسيل نكلو ةهباشم ةنيع تافاقثلا تافلاتخلاا هذه ريثأت ةسارد ىلإ ةفاضإ .ايلاطيإو ديوسلا ، ةيدوعسلا ةيبرعلا ةكلمملا يه فدهت امك .يئابرهكلاو يكيناكيملا زيفحتلا لباقم يف ةيساسحلاو ، مللأا راشتناو ةدش لدعم يف لك يف ةنمزم ضارمأ ةعبرأ ببسب زجعلاب ةلصلا تاذ ملالآا ىلع تافاقثلا فلاتخا ريثأت ةساردل تاعانقلاو ىقلتملا جلاعلا عونو ،ةقباسلا رهشأ ةتسلا للاخ )ةدعملاو ردصلاو سأرلاو رهظلا( نم .يغدصلا كفلا لصفم ةمزلاتم تابارطضاو ملاآ نم نوناعي نيذلا ىضرملا ىدل دجوت يتلا :يلي اميف صخلتت ةلاسرلل ةيليصفتلا فادهلأا )I( .نييدوعسلا دنع يغدصلا كفلا لصفم ةمزلاتم راشتنا ىدم ديدحتل :لاوأ نيناعي يتلالا ءاسنلا نم ىضرملا يف ةيئابرهكلاو ةيكيناكيملا تارثؤملل ةباجتسلاا ةنراقمل :ايناث يف لكاشملا هذه نم ةيلاخ ةيواسم ةنيعو يغدصلا كفلا لصفم ةمزلاتم تابارطضاو ملاآ نم )III( .ةيديوسلاو ةيلاطيلإاو ةيدوعسلا( ثلاثلا تافاقثلا لك مللأا تلااح بحاصي يذلا مللأاب قلعتملا زجعلا رادقمو ، هتدشو مللأا راشتنا ىدم مييقتل :اثلاث ةيضرملا تلااحلا نيبو ثلاثلا تافاقثلا فلتخم نيب لعافتلا ريثأت رابتخا قيرط نع ةيضرملا .ةفاقث لك يف ضارملأا مهيدل تسيل نمم اهلباقيامو ةمزلاتم تابارطضاو ملاآ نم نيناعي يتلالا تاضيرملا هل تعضخ يذلا جلاعلا عون مييقتل :اعبار وأ/و ثودح يف مهاست يتلا لماوعلا لوح نهتادقتعمو ، ثلاثلا تافاقثلا يف يغدصلا كفلا لصفم )IV( .جلاعلا يف اهلاخدلإ ةمهملا لماوعلا نع لاضف ، تابارطضلااو ملالآا هذه مقافتوحوارتت ، )ثانإ ١٩٠ و روكذ ١٣٥( نييدوعس ةضيرمو اضيرم ٣٢٥ )I( ةساردلا تلمش رونلا ىفشتسمب يصصختلا نانسلأا بط زكرم ىلإ اوليحأو ، اماع ٤٠ - ٢٠ نيب مهرامعأ ريياعملا بسح يضرملا خيراتلا خيراتلا نايبتسا ىلع ةباجلإاو ،ةمركملا ةكم يف يصصختلا ةخسنلا )RDC/TMD( يغدصلا كفلا لصفم ةمزلاتم تابارطضاو ملالآ ةيصيخشتلا ةيثحبلا يغدصلا كفلا لصفمو هجولاب ملاآ دوجوب دافأ نمل يريرسلا صحفلا ءارجإ مت دقو .ةيبرعلا اضيرم ٤٦ يريرسلا صحفلل عضخ دقو .روكذملا نايبتسلاا بسح قباسلا رهشلا للاخ .ةضيرمو لصفم ةمزلاتم تابارطضا مهيدل ةساردلا ةنيع نم )٪١٨( ٥٨ نأ ةساردلا جئاتن ترهظأو لك نم ةيلاع تايوتسم مللأا نم يناعت يتلا ةعومجملا تركذو .مللأاب ةطبترملا يغدصلا كفلا مهمو ظوحلم فلاتخاب )٪٩٣( ةبسنب ةيضاملا رهشأ ةتسلا للاخ يفصنلا عادصلا / عادصلا نم .مللأا نم يناعتلا يتلا ةعومجملاب ةنراقملا دنع نم لقلأا يلع دحاو صيخشت مهيدل مللأا ةعومجم يف ىضرملا عيمج نأ حضتا امك ةعومجم ىدل نأ امك ، يغدصلا كفلا لصفم ةمزلاتم تابارطضاو ملاآ ةيعرفلا تاصيخشتلا .ةددحملا ريغ ةيدسجلا ضارعلأاو بائتكلاا تارشؤم نم ةيلاع تلادعم مللأا ملاآ نهيدل نمم ةضيرم ١٢٢ ىلع ةنراقم تاساردك )I-IV( تاساردلا تيرجأ دقو تايديوس ٤١ ، تايدوعس ٣٩( ناك ثيحب ةنمزملا يغدصلا كفلا لصفم ةمزلاتم تابارطضاو ةمزلاتم ملاآ نهيدل تسيل ثانإب رامعلأا سفنبو ةيواسم دادعأب نهتنراقم تمت )تايلاطيإ ٤٢ و .ةلود لك يف يغدصلا كفلا لصفم ماهبإ نيب ةلضع ىلع هلامتحا ىدمو مللأاب ساسحلإا ةيادب سايق )II( ةساردلا تنمضت دقو ،ةيئابرهكلا ةبذبذلل كاردلإا ةيادب سايقو ، غضملا تلاضع نم نيتنثاو ىنميلا ديلا ةبابسو تافلاتخا ترهظ دقو .ةبابسلاو ماهبلإا نيب يئابرهكلا مللأا لامتحا ىدمو يئابرهكلا مللأا ةيادبو .تاسايقلا هذه يف تافاقثلا نيب يف ،يئابرهكلاو يكيناكيملا زيفحتلا يلكل ةيساسح ىلعأ تايلاطيلإا ثانلإا نأ حضتا ثيح تافاقثلا نيب يكيناكيملا مللأا لامتحا ىدم تفلتخا دقو .ةيساسح لقأ تايديوسلا نأ حضتا نيح لماوعلا رثؤت دق .نأ ىلإ حوضوب ريشي اذهويئابرهكلا مللأا لامتحا ىدم لعف امم رثكأ ةفلتخملا ..مللأا رابتخا عونل ةباجتسلاا يف ةيفاقثلا ملاآو ةدعملاو ردصلاو رهظلا ملاآ ةدشو راشتنا لدعم مييقتل تانايبتسا )III( ةساردلا تلمش امك .ةيمويلا ةطشنلأا يف اهنم لكل لخدتلا ىدمو سأرلا

فلتخم نيب راشتنلاا لدعم يف تفلتخا يتلا ةديحولا ةيضرملا ةلاحلا يه رهظلا ملاآ تناك ددعلا فلتخي مل .ثلاثلا تافاقثلا عيمج يف اعويش رثكلأا سأرلا ملاآو عادصلا ناك امك .تافاقثلا ملاآ نم يناعت يتلا ةعومجملا تركذ نكلو ،تافاقثلا نيب ةبحاصملا ةيضرملا تلااحلل يلكلا تسيل نم عم ةنراقم ةبحامصلا ةيضرملا تلااحلا نم ديزملا يغدصلا كفلا لصفم ةمزلاتم تايلاطيلإا تناك يغدصلا لصفملا مزلاتم ملاآ ةعومجم نمضو .ةمزلاتملا هذه ملاا مهيدل .مللأاب طبترملا زجعلل ضرعتلل رثكلأا ةمزلاتم ملاآ عم ةعئاشلا مللأا تلااح ةبحاصم يف رثؤت ةفاقثلا نأ ىلإ ةساردلا هذه ريشتو .ةيعيبطلا هضارعأ راهظإو مللأا نع ريبعتلا يف ةفاقثلا رثؤت امك ، يغدصلا كفلا لصفم عونو ،جلاعلا ةقلعتملا مهتادقتعمو ىضرملا صئاصخ ةنراقم تمت )IV( ةساردلا يفو لصفم ةمزلاتم تابارطضاو ملالآ جلاعلا بلطل مهتعجارم دنع اهوقلت يتلا ةيبطلا ةروشملا مييقت نايبتسا يف ىضرملا باجأ .لاجملا اذه يف يصاصتخلال مهتلاحإ لبق يغدصلا كفلا يف مهاست يتلا لماوعلا لوح مهتاعانقو مهتادقتعم نع ايريسفت اجذومن ةئبعتو ةدراولا تاجلاعلا .اهنمضتي نأ بجي جلاعلا اهنأ نودقتعي يتلا لماوعلا ىلإ ةفاضإ ، ةلكشملا مقافت وأ ثودح تايديوسلا تاضيرملا نأ تاجلاعلا نأ دجن ىضرملا اهيلإ ىعس يتلا تاجلاعلا ىلإ رظنلا دنع لباقملابو .ةيومفلا ةزهجلأاب جلاعلاو ةينيصلا ربلإا اميسلا يكولسلا جلاعلا ىلإ رثكأ نيعس .يملاسلإا بطلاب جلاع ىلع لوصحلل ظوحلم لكشب لوصحلل تايدوعسلا تاضيرملا تعس لكشب ةيكولسلا تاجلاعلا نم يلأ جلاعلا نمضتي نأ ةيمهأب ندقتعي مل تايلاطيلإا تاضيرملا .صوصخلا اذه يف تايدوعسلاو تايديوسلا هندقتعي امم لقأ هتراشتسا متت يذلا بيبطلا صصخت ىلع رثؤي لا ةفاقثلا فلاتخا نأ ةساردلا هذه نم حضتي ىلع ةفاقثلا رثؤتلا كلذكو ،يغدصلا كفلا لصفم ةمزلاتم ملاآ جلاع ييصاصتخا ةرايز لبق فلاتخا رثأ امني ، امومع مهملاآ مقافت ، ثودح يف مهست يتلا لماوعلا لوح ىضرملا تادقتعم .ةيكولس قرطل جلاعلا نمضت ةيمهأب داقتعلاا يف تافاقثلا

POULÄRVETENSKAPLIG

SAMMANFATTNING

(SUMMARY IN SWEDISH)

Det övergripande syftet med denna avhandling var att undersöka patienter med TMD-smärta och individer utan TMD-smärta i tre kulturer (Saudiarabien, Sverige och Italien) för att utvärdera vilket inflytande kulturen och tvärkulturella skillnader har på förekomst och intensitet av smärta, känslighet för mekanisk och elektrisk stimulering, smärtrelaterade funktionshinder för fyra samsjukliga smärttillstånd (rygg, huvud, bröst och mage), och vilken typ av behandling som patienter med TMD-smärta fick.

De specifika målen var:

(i) Att bestämma frekvensen av TMD-smärta hos individer i Saudi Arabia (I)

(ii) Att jämföra upplevelsen av mekaniska och elektriska stimuli hos kvinnliga TMD patienter och TMD-fria individer inom var och en av tre kulturer (Saudisk, italiensk och svensk) (II).

(iii) Att bedöma smärtans prevalens och intensitet, och smärtrelaterade funktionshinder vid samsjukliga

smärttillstånd genom att testa interaktionseffekten mellan tre olika kulturer och fall-status (III).

(iv) För att bedöma vilken typ av behandling som kvinnliga patienter med TMD-smärta i tre kulturer mottagna, samt deras uppfattning om vilka faktorer som bidrar till och förvärrar TMD, liksom vilka faktorer som är viktiga att inkludera i TMD behandling (IV).

I materialet för Studie (I) ingick 325 patienter från Saudi Arabien (135 män, 190 kvinnor) i åldern 20-40, som remitterats till specialistkliniken Specialist på Al Noor specialistsjukhus, Mecka och besvarade ett frågeformulär om TMD. Patienter som rapporterade TMD smärta under den senaste månaden erbjöds en klinisk undersökning och bedömning enligt den arabiska versionen av Research Diagnostic Criteria för TMD (RDC/TMD).

Av dessa patienter rapporterade 58 (18%) patienter TMD smärta, varav 46 patienter blev kliniskt undersökta. Alla TMD smärtpatienter hade diagnosen myofascial smärta, och 65% hade diagnoser av ledsmärta eller artros. Gruppen med TMD-smärta rapporterat hög frekvens av huvudvärk/migrän under de senaste 6 månaderna (93%),vilket skiljer sig signifikant från de TMD-smärta-fria gruppern.

Alla i smärtgruppen hade minst en underdiagnos av TMD-smärta. TMD-smärta gruppen hade höga värden på depression och somatisering, men låga värden på dysfunktion enligt graded chronic pain scale.

I Studierna (II-IV) jämfördes 122 kvinnliga patienter med kronisk TMD-smärta (39 saudiska, 41 svenskar och 42 italienare) gentemot lika många åldersmatchade TMD-fria kontroller. I Studie (II) mättes smärttröskel (PPT) och tolerans (PPTo) för tryck över ena sidan av två tuggmuskler, samt smärttröskel (EPT) och smärttolerans (EPTO) för elektrisk stimulering mellan tummen och pekfingret.

Kulturella skillnader visades i PPT, PPTo och EPTo Generellt rapporterade italienska kvinnor den högsta känsligheten för både mekanisk och elektrisk stimulering, medan svenskarna rapporterade minst känslighet. Mekanisk smärttröskel skilde mer mellan olika kulturer än elektrisk smärttröskel. Kulturella faktorer tycks ha en påverkan på svaret av dessa test av smärta.

I Studie (III) bedömdes smärtans prevalens, intensitet och påverkan på dagliga aktiviteter i rygg, bröst, mage och huvud genom självrapportering i frågeformulär.

Ryggsmärta var det enda samsjukliga tillstånd som varierade i prevalens i olika kulturer; huvudvärk var det vanligaste i alla tre kulturer; där den genomsnittliga intensiteten av huvudvärk var lägre hos svenskar jämfört med saudier. Det totala antalet samsjukliga tillstånd skilde sig inte tvärkulturellt, men gruppen med TMD rapporterade fler samsjukliga tillstånd jämfört med den TMD-fria gruppen. För både ryggsmärta och huvudvärk, rapporterade TMD gruppen högre genomsnittlig smärtintensitet och störningar i dagliga aktiviteter än den TMD-fria gruppen. Bland TMD patienter rapporterade italienare de flesta smärtrelaterade funktionshindren.

Denna studie indikerar att kulturen påverkar samsjukliga smärttillstånd vid TMD. Kultur påverkar upplevelsen av smärta och i sin tur dess fysiska förmåga.

I Studie (IV) jämfördes patienters karakteristika, tilltro till behandling, och vilket råd som getts av läkare /tandläkare innan remiss skickades för TMD behandling. Patienterna besvarade en enkät som angav vilka behandlingar som getts samt ett formulär om sina föreställningar om vilka faktorer som bidrar till och förvärrar TMD, och vilka faktorer som är viktiga att ta hänsyn till vid behandling.

Av de olika behandlingarna var det vanligast att svenskar sökte beteendeterapi och saudier islamisk medicin. Svenskar fick akupunktur och bettskenor betydligt oftare än saudier eller italienare. Italienarna trodde i mindre utsträckning än saudier och svenskar att behandling för TMD-smärta bör innefatta beteendemässiga faktorer. Bland saudiska, italienska och svenska kvinnor med kronisk TMD smärta, hade kultur ingen påverkan på vilken typ av läkare / tandläkare som konsulterades innan besöket hos en TMD specialist, eller deras föreställningar om faktorer som bidrar till eller försvårar deras smärta. Sammantaget fanns det kulturella skillnader avseende vilka behandlingar patienterna fick och deras tro på beteendefaktorers betydelse för TMD. Islamisk medicin var ganska vanligt bland saudier och akupunktur var vanligt bland svenskar.

PREFACE

This thesis is based on the following studies

I. Al-Harthy M, Al-Bishri A, Ekberg E, Nilner M.

Temporomandibular disorder pain in adult Saudi Arabians referred for specialised dental treatment. Swed Dent J. 2010;34(3):149-5.

II. Al-Harthy M, Ohrbach R, Michelotti A, List T. The effect of culture on pain sensitivity. J Oral Rehabil. 2016 Feb;43(2):81-8.

III. M. Al-Harthy, T. List,, A. Michelotti, R. Ohrbach. Influence of culture on pain comorbidity in females with temporomandibular disorders. (Submitted)

IV. M. Al-Harthy, T. List ,R. Ohrbach, A. Michelotti. Cross-cultural differences in types and beliefs about treatment in female patients with temporomandibular disorders. (Manuscript)

Published papers are reprinted with the kind permission of the copyright holders.

THESIS A

T A GL

AN

CE

TH ES IS AT A G LAN CE St udy A im s M etho ds M ain F indi ng s/C onc lus ions Illu st ra tio ns (I ) Te m por om andi bul ar di sor de r (T M D )-pa in i n adul t S audi A rabi ans ref err ed f or spe cia liz ed den tal treat m en t To det er m ine t he f req uen cy of TM D -p ain in S audi A rab ian s. Th e stu dy inc lude d 325 pa tie nt s ( 135 m ale s, 19 0 fem ale s) w ho ans w ere d a hi stor y que stionna ire . P atie nt s r epor ting TM D -p ain in th e l ast m on th w ere off ere d a c lin ic al e xa m in atio n. H is to ry que stionna ire s a nd c lini ca l e xa m ina tions fo llo w ed th e A rabi c ve rsion of th e R esear ch D iag no st ic C riter ia f or T M D (RD C/ TM D ). Prev al en ce o f TM D -p ain w as 1 8% . A ll p atie nts w ith TM D -pa in ha d a di agnos is of m yof asc ial pa in , a nd 65% had ar th ralg ia o r o ste oa rth ritis . H ead ach es di ffe red bet w een pa tie nts w ith TM D -p ain and thos e w ithout (P < 0. 001 ). G rade d C hr oni c P ain S cal e a sse ssm en ts cla ssif ie d 4 5% o f th e p atie nts w ith TM D -pa in in G rad e I, 53% in G rad e II, 2 % in G rad e III, and 0% in G rad e IV . (II) Th e ef fect o f cu ltu re o n pa in se nsitiv ity To com pa re ps yc hophys ica l res pons es t o m ec ha ni ca l a nd ele ctr ic al s tim uli in fe m ale pa tie nts w ith T M D -p ain and TM D -fr ee co ntr ols, n est ed w ith in th ree c ult ure s ( Sa ud i, Ita lia n, a nd S w edi sh) . Th is c ase -cont rol study c om pa red 122 fem al e pa tie nts w ith TM D -pa in (39 Sa udi s, 41 S w ede s, a nd 42 I tali ans ) w ith ag e- a nd ge nde r-m atc he d TM D -fr ee co n-tro ls. D en tis ts m ea sur ed th e p re ssu re pa in t hr eshol d ( PPT ) a nd tol er an ce (PPT o) on one ha nd a nd t w o m ast ica tory m us cle s; an d t he e lec tri ca l p er cep tio n thre sh old an d t he el ect rical p res su re thr eshol d ( EPT ) a nd tol er an ce ( EP To ) be tw ee n t he thum b a nd i nde x f inge rs. C ul tur al di ffe renc es be tw ee n gr oups ap pear ed in P PT , P PT o a nd E PT o. O ve ra ll, It alia n fem ale s r epor ted t he hi ghe st s ens itivi ty t o bot h m ec ha nic al a nd ele ctri ca l s tim ula tio n, w hil e Sw ed es r ep orte d th e lo w est s en sitiv ity . M ec ha ni ca l pa in t hr eshol ds di ffe red m or e acr oss cu ltu res th an d id el ect rical p ai n thre sh old s. C ult ura l f ac tors m ay inf lue nce res pons e t o t ype of pa in t est . (III) Inf lue nc e of c ul tur e on pa in c om or bi di ty i n fem al es w ith TM D To assess p rev al en ce, p ai n int ens ity, a nd pa in-rel ate d di sabi lity of c om or bi d pa in condi tions by t est ing f or the int er act ion ef fect b et w een th e va rious cu ltu res an d cas e sta tus . Th is c ase -cont rol study c om pa red 122 fem al e TM D -p ain (39 S audi s, 41 Sw ed es , an d 42 I tali ans ) w ith a ge - a nd ge nde r-m atc he d TM D -fr ee co ntr ols. Se lf-r epor t que stionna ire s a sse sse d ba ck, ch es t, s tom ach , a nd he ad pa in f or pre va le nc e, p ain in te nsity , a nd int erf ere nc e w ith d aily a ctiv itie s. C ul tur e i nf lue nc ed the a ssoc iate d c om or bi di ty of ot he r c om m on pa in c ondi tions w ith T M D . B ac k pa in w as t he onl y c om or bi d c ondi tion w ith a sig nifi ca ntl y d iffer en t p rev al en ce acr oss cu ltu res ; S w ed es rep ort ed a l ow er p rev al en ce tha n S audi s ( P = 0. 002) . H ead ach e w as com m on a m ong th e t hre e c ult ure s. C ultu re see m s to aff ec t t he e xpr ess ion of pa in. (I V ) C ro ss-cu ltu ral d iffer en ces in t ype s a nd be lie fs a bout tre atm en t i n f em ale pa tie nts w ith T M D To assess in fe m ale p atie nts w ith T M D -pa in fro m th re e cu ltu res : (i) Type of tr ea tm en t s ou gh t (ii) B el ief s a bout cont ri-but ing an d a ggr ava ting fact ors and i m por tant fac tor s t o i nc lude in tre atm en t. Thi s s tudy co m par ed 12 2 f em al e pa tie nts w ith T M D -pa in (39 S audi s, 41 Sw ede s, a nd 42 I tali ans ) c onc erni ng pat ien t ch ar ac teri stic s, tr ea tm en t b elie fs, an d t re atm en t so ug ht b efo re r efe rra l fo r TM D treat m en t; t he ir be lie fs r ega rdi ng cont ribut ing an d a ggr ava ting fact ors f or TM D ; a nd i m por tant fa ctor s t o i nc lude in i ts t re atm en t. C ultu re d id not inf lue nc e t ype of pr ac titi one rs cons ul ted be for e v is itin g a TM D sp ec ia lis t, or be lie fs a bout cont ribut ing a nd a ggr ava ting fact ors f or ch ro nic TM D -p ain . T reat m en ts so ug ht a fte r d iagn osi s an d b el ief s a bout the im por tanc e of inc ludi ng be ha vi ora l f ac tors in tre atm en t d iffe red cro ss-cu ltu rally . I sla m ic m ed icin e w as fai rly co m m on am on g Sa ud is a nd acu pu nc tur e w as c om m on a m ong S w ede s.ABBREVIATIONS

CAM Complementary and alternative medicine

CPI Characteristic Pain Intensity

DC/TMD Diagnostic Criteria for TMD

EPT Electrical pain threshold

EPTo Electrical pain tolerance

GCPS Graded Chronic Pain Scale

IADR International Association for Dental Research

NIH National Institute of Health

NS Non-significant

NSAIDs Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

NRS Numeric rating scale

OPPERA Orofacial pain: perspective evaluation and risk assessment

PPT Pressure pain threshold

PPTo Pressure pain tolerance

RDC/TMD Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD

SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist-90-Revised

SPSS Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

TMD Temporomandibular disorders

TMD-pain Temporomandibular disorders-pain

TMJ Temporomandibular Joint

Tukey’s HSD test Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference test

1. INTRODUCTION

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD)

Definition and prevalence

TMD encompasses a group of musculoskeletal and neuromuscular conditions that involve the temporomandibular joints (TMJs), the masticatory muscles, and all associated tissues [1] with a prevalence of approximately 5%−12% [2, 3]. Epidemiological studies on TMD have been done in several countries worldwide and TMD-pain appears to be 1.5–2 times more common in women than men [4, 5] and occurs in young and middle-aged adults [4-6], as well as children and adolescents [7-9].

Although the difference in TMD prevalence between males and females is still not well understood, some have proposed theories to explain why females are more affected than males [10]. With regards to incidence, some recent studies reported that TMD symptom incidences were marginally greater in women compared to men and this unexpected finding mainly related to prevalence-incidence bias. Cross-sectional designs investigate the prevalence of health conditions at just one point of time without recording whether cases were resolved later [11].

Diagnosis of TMD

In the past, examining signs and symptoms was the preferred way to study the epidemiology of TMD without diagnosing subgroups of TMD. This absence of a unified taxonomy among epidemiological studies limited comparison of their data [12, 13]. The Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (RDC/TMD), published in 1992 [13], provided an initial step to address these shortcomings. They were

intended primarily for research purposes, allowing standardized methods for gathering relevant data and enabling comparison of findings among diverse clinical investigators [13]. Reliable diagnosis is critical in establishing a clinical condition and determining a rational approach to treatment, and the RDC/TMD is the most widely used TMD diagnostic system for clinical research [14]. The RDC/TMD diagnostic system was the first available diagnostic system for TMD that is empirically based, uses operationally defined measurement criteria to generate computer-derived diagnostic algorithms for the most common TMD forms, and provides guidelines for conducting a standardized clinical physical examination. The RDC/TMD (i) divides the most common forms of TMD into the three groups of diagnoses − myofascial pain, disc displacements, and other joint conditions, such as arthralgia, arthritis, and arthrosis − and (ii) allows multiple diagnoses to be made for a given patient [13].

The RDC/TMD Axis II assesses psychological status, yielding a profile of chronic pain dysfunction, depression, and somatization[13]. It has been formally translated and then back-translated into more than 20 languages [14, 15]. Researchers found that the RDC/TMD demonstrates sufficiently high reliability for the most common TMD diagnoses, supporting its use in clinical research and decision-making [14].The International RDC/TMD Consortium is affiliated with the International Association for Dental Research (IADR) and conducts at least one scientific meeting per year in conjunction with IADR meetings in order to disseminate research related to TMD and discuss criticisms [16]. The National Institute of Health (NIH) supported the validation study proposed by Schiffman and his colleagues [3] to investigate the validity and reliability of the RDC/TMD and supported the development of the Diagnostic Criteria of TMD (DC/TMD), which is valid for clinical use in addition to scientific research compared with the RDC/TMD criteria, which were intended primarily for research purposes [17]. A second study supported was the Orofacial Pain: Perspective Evaluation and Risk Assessment (OPPERA) which investigated the risk factors related to TMD [18].

Management of TMD

Because the etiology of orofacial pain is complex and associated with many predisposing factors, there is no single specific or “gold

standard” treatment of choice. Thus the recommended treatment is a multidimensional approach to management after specific diagnosis of the problem, including all kinds of possible treatments. Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is defined as the integration of (i) best research evidence with (ii) clinical experience and (iii) patient values. Integrating these three elements is essential in order to achieve optimal clinical outcomes and quality of life for the patient.

From an evidence-based perspective, clinically relevant research has indicated which interventions provide the most effective treatment of TMD/orofacial pain. In addition, studies describing clinicians’ experience and which treatments they prefer and perform have been done [19, 20]. However, these sometimes seem to conflict with the personal preferences and unique concerns, expectations, and values of the patients [21]. As in other chronic pain conditions, patient education and reassurance is a very important element at the beginning of any treatment. Clinically, the best approach is to consider all conservative management modalities before any invasive or surgical interventions unless expert application of the conservative treatments fails to create improvement or satisfactory outcomes.

Another important idea to keep in mind is that there is no golden management modality for every case with the same orofacial pain diagnosis. Rather, it is better that treatment plans consider each case depending not only upon its diagnosis, but also other factors. This means that a treatment modality that is appropriate for treating one case might not be the best treatment modality for another case with the same diagnosis. Combination treatment is recommended for managing chronic TMD in general.

Pain Sensitivity and TMD

Evidence strongly supports TMD as a musculoskeletal condition characterized by increased sensitivity to mechanical stimulation [22-24]. Studies have used both mechanical and electrical stimuli to measure pain sensitivity in the orofacial region [25, 26]. Mechanical stimulation, i.e. a pressure stimulus, activates nociceptors on the A-delta and C fibers, whereas electrical stimulation activates non-nociceptive and non-nociceptive A-beta, A-delta, and C fibers. TMD differs significamtly in PPT both regional as well as non regional areas. One of the characteristcs of TMD is pain upon palpation;

nevertheless, TMD-pain facilitates greater central sensitization by increasing the synaptic efficacy of neurons (second-order and above) in nociceptive pathways [11].

Pain Comorbidity and TMD

Comorbidity is defined as a “concurrent existence and occurrence of two or more medically diagnosed diseases in the same individual” [27]. While TMD is typically considered a primarily localized disorder of the jaw, substantial comorbidity occurs with facial, back, chest, and abdominal pain conditions [4]. Moreover, current data indicate that TMD is a complex disorder that must be viewed from a biopsychosocial illness model, further emphasizing that TMD is more than a localized orofacial pain condition [28]. Among US samples, 69% to 76% of orofacial pain patients report pain extending beyond the head and face [29], and among individuals with chronic TMD, the most common comorbid chronic pain conditions are back pain, neck pain, and headache, as reported by adults and adolescents in both the US [30, 31] and Sweden [32].

Patients with one pain condition seem strongly predisposed to having another [33]. For example, a case-control study that examined comorbidity between back pain and TMD-pain in a Swedish sample concluded that patients with TMD have a higher probability of reporting back pain than those without TMD [32]. While TMD may be defined by the specific local structures associated with the patient’s pain complaint, the persistence of pain and other factors seem to facilitate high comorbidity [30]. Such comorbidity affects both prognosis and the efficacy of condition-specific treatments [34]. Moreover, understanding comorbidity of other chronic pain conditions with TMD will increase awareness of their overlap, which will improve TMD diagnosis and management [35]. Increasing dentists’ understanding of TMD and the identification of comorbidity with other chronic pain conditions will improve the multidisciplinary approach in managing such conditions, facilitate well-designed treatment planning in order to restore function, and minimize suffering from orofacial pain. A recent study concluded that poor health status, that is, multiple pain comorbidities is a strong indicator of TMD-pain incidence [11].

Culture

Culture and context

The definition of culture that anthropologists famously used belonged to Edward B. Tylor in 1987: “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society” [36]. Culture represents a set of values, beliefs, experiences of living, attitudes, and learned patterns of behavior shared by the members of a particular society [37-39]. Context, according to the Oxford University Press Dictionary, is:” The circumstances that form the setting for an event, statement, or idea, and in terms of which it can be fully understood.” Culture must always be seen in its particular context, which is made up of historical, religious, economic, social, political, and geographical elements that both influence culture and respond to it [40]. However, culture is not the only factor that influences health beliefs and behavior. Demographic characteristics such as individual, educational, socioeconomic, and environmental factors also play a role. These factors form the context around each individual within a culture and affect the extent to which an individual’s behavior matches cultural expectations [36].

This thesis uses cultural differences as a synonym for ethnic differences among individuals of three countries residing in their country of birth.

Culture and pain sensitivity

Studies have shown that culture is an important factor affecting perception, experience, and expression of pain [41, 42]. Cross-cultural studies reveal that description and perception of pain are culturally specific [39]. From the neurophysiological point of view, no differences were assumed between different cultural groups based on differences in the biocultural pattern of pain. Within each culture, people may react to their pain similarly in terms of pain perception, expression, and response due to shared experiences that may influence neurophysiological processing of nociceptive information, as well as the psychological, behavioral, and verbal responses to pain [43].

Both pain-free subjects and individuals with chronic pain show cross-cultural differences in pain sensitivity for a wide range of psychophysical methods [44-47]. For example, among pain-free

subjects, South Indians demonstrate higher capsaicin-induced pain intensity and lower pressure pain thresholds (PPT) than Danish Caucasians [46], whereas South Asians show lower thermal pain thresholds than Caucasians [45]. Swedish Caucasians exhibit higher tolerance to thermal pain and pressure pain than Middle Eastern Caucasians [44]. However, there was no cross-cultural difference between adults from Japan and the USA in electrically induced dental pain [48].

The literature also shows the influence of gender on experimental pain measures and pain experience [44, 47, 49]. In a meta-analysis by Riley et al., pressure pain showed the largest gender differences [50] and most studies published since then support the conclusion that females are more sensitive to pressure pain than males [51]. Others have found significant between-gender differences in electrical pain threshold (EPT) and in both electrical (EPTo) and pressure pain tolerance (PPTo) [44].

Culture and pain comorbidity

Since biopsychosocial context defines pain for each individual, cross-cultural differences might be expected in patterns of comorbidity among these common pain conditions. Studies show cross-cultural differences in prevalence, pain intensity, and pain-related disability in several chronic pain conditions, such as back pain, neck pain, headache, and TMD-pain [47, 52]. A population study of these multiple pains across four different cultural groups found a predominance of female subjects for each condition, as well as variations in the prevalence of each condition [53]. Evidence of cultural differences in the prevalence and impact of common chronic pain conditions, such as comparing individuals with TMD and those without TMD across cultures, however, is limited.

Culture and TMD-pain patient’s beliefs in treatment

Beliefs are defined as “things that are accepted as true, especially as a tenet or a body of tenets, in contrast to knowledge which is considered as true” [54]. Beliefs are built on personal knowledge. An attitude towards a particular behavior represents a summation of beliefs about that behavior and determines the behavior. Culture determines beliefs that are learned by socialization [55] and, since culture cannot

be defined separately from its context, it is hard to isolate any cultural belief and cultural behavior from its socioeconomic context [36].

Cultural differences occur in patient attitudes toward medical care and pain coping strategies [56, 57]. For example, African Americans and Latinos were more frequently concerned than their white counterparts about taking potent opioid medications for cancer pain due to the risk of side effects and addiction [58, 59]. They preferred to take analgesics for severe pain, while trusting in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for treating mild to moderate pain [58, 60]. African-American women reported using prayers and religious strategies more than Caucasian women in order to cope with chronic pain [61, 62].

A large epidemiological survey of chronic pain in Europe found differences between countries in the treatments provided. Acupuncture, physiotherapy, and prescription of weak opioids were more common in Sweden, while prescription of Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) was more common in Italy [63]. These differences may be related to availability and traditions of treatment. For example, in Sweden acupuncture is commonly provided within the medical system, whereas other countries view acupuncture mainly as complimentary medicine or alternative medicine, provided by other therapists.

2. HYPOTHESES

The studies in this thesis tested these hypotheses: Study (I)

1. The group of dental patients will show subdiagnoses of TMD. 2. Gender makeup and psychosocial status will differ between

the TMD-pain group and the TMD-pain-free group. Study (II)

Sensitivity to mechanical and electrical stimuli will differ between cultures and between patients with chronic TMD and TMD-free subjects.

Study (III)

Prevalence, pain intensity, and pain-related disability associated with common comorbid pain conditions (back, chest, stomach, and head pain) in the last 6 months will differ across cultures and be greater among individuals with chronic TMD-pain than in TMD-free controls.

Study (IV)

Female chronic TMD cases from three cultural groups will show cultural differences in their beliefs about treatment and in the type of treatment they received.

3. AIMS

The specific aims of this thesis were: Study (I)

To determine the frequency of TMD-pain among Saudi Arabians. Study (II)

To compare psychophysical responses to mechanical and electrical stimulation in female patients with TMD and TMD-free controls from each of three cultures (Saudi, Italian, and Swedish).

Study (III)

To assess prevalence, pain intensity, and pain-related disability of comorbid pain conditions in the last 6 months by testing for the interaction of effects between three different cultures and TMD case status.

Study (IV)

To assess the type of treatment female patients with TMD from three cultures received, and their beliefs regarding the contributing and aggravating factors for TMD, and important factors to include in their treatment.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study centers and data collection (I–IV)

Study (I) invited 335 consecutive Saudi dental patients who had been referred to the Specialist Dental Center at Al-Noor Specialist Hospital in Makkah, Saudi Arabia to participate in the study. The patients had been referred from primary and secondary health care clinics for specialized care unrelated to TMD-pain.

Studies (II–IV) included consecutively selected female patients (N = 122) with chronic TMD (39 Saudis, 41 Swedes, and 42 Italians) diagnosed according to the RDC/TMD [13] in three case-control studies. In Studies (II–III) we age-matched these patients with 121 TMD-free female controls (39 Saudis, 40 Swedes, and 42 Italians).

Studies (II–IV) involved four study sites: (1) the Department of Orofacial Pain and Jaw Function, Faculty of Odontology, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden, (2) the Department of Orthodontics and Temporomandibular Disorders, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy, (3) the Specialist Dental Center, Al-Noor Specialist Hospital, Makkah, Saudi Arabia, and (4) the Dental Center, King Fahd General Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. We consecutively recruited our subjects from new patients at these clinics. In Naples, we recruited TMD-free controls from the people accompanying patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. At the other three centers, we advertised in clinical and community settings to recruit controls. Data analysis combined the participants from the two Saudi study sites.

Patients with TMD and TMD-free controls (I–IV)

Inclusion criteria for Study (I) were: (1) age 20–40 years and (2) ability to communicate in an interview. The exclusion criterion was

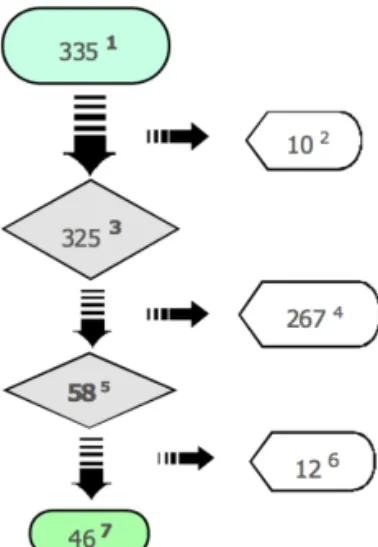

acute dental pain. Of 335 initial consecutive patients, 10 met the exclusion criterion. From the resulting sample of 325 patients, 58 patients reported TMD-pain according to item 3 in the RDC/TMD history questionnaire [13]: “Have you had pain in the face, jaw, temple, in front of the ear, or in the ear in the past month?” Of these 58, 12 declined clinical examination because they either had no time or were not interested. So Study (I) comprised 46 patients diagnosed with TMD via the RDC/TMD after clinical examination (patients with TMD-pain) and 267 who did not report TMD-pain (TMD-pain-free controls).

Sampling of cases and controls for Studies (II–IV) included patients (1) of female gender (2) 18–75 years old, (3) with sufficient spoken and written language skills in the host language, (4) able to complete questionnaires (instruments), and (5) identifying with the dominant culture of the study site. Three criteria influenced our assessment of the cultural identification of participants: (i) the participant and at least one parent were born in the host culture, (ii) the participant spoke the host language at home while growing up, and (iii) the participant self-identifies as a member of that culture.

To be included as a case, patients also had to (1) report pain in the face, jaw, temple, in front of the ear, or in the ear occurring in the last month and persisting for at least the prior three months and (2) show at least one pain diagnosis according to the RDC/TMD [13].

Likewise, TMD-free controls had to be (1) pain-free in the TMJ and masticatory muscles for the past month, (2) not using medication or treatment for orofacial pain (a confirmation of being pain-free in the masticatory region), and (3) matched with one of the cases for age (± 2 years) and study site. These studies excluded any cases or controls with dental pain, orofacial neuropathic pain conditions, burning mouth syndrome, auto-immune diseases, or significant mental impairment that would prevent compliance with study instructions.

Ethical considerations (I-IV)

In Study (I), because there was no scientific research ethics committee in the area at the time of the study, the Director of Health Affairs in Makkah, Saudi Arabia granted ethics approval for the study. The regional research ethics committee in Lund, Sweden provided the preliminary ethics approval for the project. All patients were

informed about the study and signed informed-consent forms. They also learned that choosing not to participate would not influence their care at the Center.

In Studies (II–IV), all participants signed informed-consent forms before enrollment. The project followed the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and the regional ethics review board in Lund approved it as a multi-center study (daybook no. [Dnr] 366/2008). After the study, an orofacial pain specialist at each study site offered treatment to all patients with chronic TMD.

Self-report questionnaires

RDC/TMD (I-IV)

In Study (I), two trained dentists interviewed the 335 patients using the Arabic version of the original history questionnaire of the RDC/TMD [15]. Of these, we excluded 10 because they refused to participate due to lack of time, severe dental pain, or communication difficulties (Figure. 1). The dentists performed the interview in a room adjacent to the examination room. For cultural reasons, a female dentist interviewed women who were accompanied by their husbands or male relatives. A dentist calibrated according to the RDC/TMD protocol performed the clinical examination.

In Study (I), original Arabic RDC/TMD [13] history questionnaire, some questions were modified or deleted so as to be acceptable in the Saudi (Arabic-Muslim) culture. In Islamic culture, any sexual relation is reserved exclusively for the confines of marriage. Translation of the RDC/TMD excluded this issue, addressed in questions 19-g and 20-b, to prevent loss of cooperation and avoid legal troubles for the health workers and interviewer. The authors of this study believe that deletion of the item about sexual relations (20-b) in the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R), does not affect the total score for depression since the sum of the scores of all answered items is divided by the number of items answered [64].In accordance with the RDC/TMD Axis I, the study evaluated physical findings with a clinical assessment of TMD signs and symptoms. It assessed pain intensity with a numeric rating scale (NRS, range 0–10). The RDC/ TMD divides the most common forms of TMD into three groups of diagnoses − myofascial pain; disc displacements; and other joint conditions, such as arthralgia, arthritis, and arthrosis − and allows multiple diagnoses for a single patient [13].

In Studies (II–IV), all participants were asked to complete the RDC/ TMD history questionnaire regarding education and marital status. The individuals with TMD also reported pain duration and, from the Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS) [65], intensity of current pain, worst pain, and average pain over the prior 6-month time period using an 11-point numeric rating scale (0=no pain and 10=pain as bad as it could be). Characteristic pain intensity (CPI) was calculated as the mean of the three ratings, multiplied by 10; this measurement has acceptable reliability and validity [66]. In addition, pain-related disability was assessed using three measures of activity interference due to pain (daily activities; recreational, social, and family activities; ability to work) and days lost from usual activities measure in the GCPS. The three activity interference measures used an 11-point numeric rating scale (0=no interference, and 10=unable to carry on any activities); scoring was performed in the same manner as for CPI. The grade of chronic pain was calculated for TMD cases only and ranges from 0 (no pain) to IV (severe dysfunction), reflecting the severity and impact of TMD pain on function.

Comorbid pain conditions questionnaire (III)

The Comorbid Pain Conditions questionnaire was based on prior research [4]. For each of back, chest, stomach, and head pains, a filter question inquired into the presence of each pain condition in the previous 6 months; a positive response to a condition lead to the following pain-condition specific questions: (i) average pain intensity in the previous 6 months using the same 11-point numeric rating scale as for the CPI scales; (ii) number of days work was reduced >50% (hereafter, days of work reduction); and (iii) activity interference due to pain, measured with the same three scales as for TMD pain. Even though individual measures within the CPI have lower reliability [66], only average pain intensity (rather than the typical 3 measures comprising the CPI) was assessed for the comorbid conditions in order to reduce subject burden, a method used elsewhere [4].

Survey of treatments received questionnaire (IV)

In Study (IV), the first survey question assessed the types of practitioners from whom patients sought treatment for their TMD-pain. These practitioners included physicians, dentists, psychologists, physical therapists, and others. This survey of the types of treatment

patients received covered 30 treatment modalities frequently used to manage TMD-pain, including both treatments recommended by the treating practitioner and those suggested by the patient’s own beliefs. We categorized these modalities into six main groups for easier representation: occlusal therapy and occlusal equilibration, physical therapy, pharmacological treatments, TMJ and maxillofacial surgery, behavioral therapy, and complementary therapy.

Explanatory Model Form (IV)

In Study (IV), the explanatory model form This instrument was developed by Massoth and Dworkin based on Pilowsky’s illness model [67]. It begins: “People who have facial pain or limitations in jaw function often say that their problem is a combination of physical, behavioral, and/or stress/emotional factors.” It then provides patients with examples of each factor item in a box at the top of the instrument to help them understand what these factors mean. The examples we gave for physical factors included traffic accident, surgical intervention, head trauma, joint inflammatory disease, and/ or other medical problems. Examples of behavioral factors included oral habits, grinding or clenching the teeth, and jaw muscle tension. Some examples of stress/emotional factors were problems with family, work, or school; anxiety; and feeling down and/or depression. Three questions queried patients’ beliefs concerning (1) how important each of these three factors was in contributing to their TMD-pain, (2) how important each was in aggravating their TMD-pain, and (3) whether management of TMD-pain should include the factor. For each item, the patient would grade her opinion and beliefs on a 0–4-point scale (0 and 1 = Not at all important, 2 and 3 = Moderately important, and 4 = Extremely important). For statistical purposes, we dichotomized these items into Not important (scores 0 and 1) and Important (scores 2, 3, and 4: moderately and extremely important). There are no psychometric data available for this checklist. The instrument is available at http://www.rdc-tmdinternational.org/OtherInstruments/ ExplanatoryModelScale.aspx.

Experimental protocols

Pressure pain measurements (II)

Study (II) took pressure pain measurements using a digital pressure algometer (SOMEDIC, Hörby AB, Sweden) with a constant

application rate of 30 kPa/s. The tip was a rubber probe with a surface area of 1 cm2, as used in other studies [68, 69]. The pressure pain threshold (PPT) represents the level of pressure (kPa) that the subject first perceives as painful. Pressure pain tolerance (PPTo) is the most painful pressure (kPa) the subject could tolerate [26]. We applied pressure over the muscles in this order: (1) the right anterior temporalis muscle, (2) the central part of the right masseter muscle, midway between the upper and lower borders and 1 cm posterior to the anterior border, and (3) the palm side of the thenar muscle of the right hand on the point connecting the longitudinal axis of the thumb and index finger [70].

Intervals between repeated pressure stimuli were 30 s for PPT measurements and 60 s for PPTo. PPT measurements in the masticatory muscles have acceptable reliability [71-73]. For analysis, we calculated the PPT as the average of three measurements and PPTo as the average of two (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Pressure pain measurements: digital pressure algometer (SOMEDIC, Hörby AB, Sweden) (A), right masseter muscle stimulation (B), stimulation of the

A

C

B

Electrical stimulation tests (II)

Study (II) measured sensitivity to electrical stimulation using the PainMatcher (Cefar Medical AB, Lund Sweden). The PainMatcher is a controlled constant-current electrical stimulation microprocessor that transmits monophasic square pulses with a frequency of 10 Hz and a pulse amplitude of 15 mA to two electrodes. The intensity slowly increases as the duration of the monophasic pulses increases from zero up to 396μs applied between the thumb and index fingers on the right hand. This testing assessed three distinct constructs: (1) the electrical perception threshold, defined as the intensity of current needed for the subject to perceive pulses in the thumb and index finger, (2) the electrical pain threshold (EPT), defined as the level of electrical stimulus that subjects first perceive as painful, and (3) electrical pain tolerance (EPTo), defined as the most painful electrical stimulus that the subject could tolerate. The psychophysical values obtained using the PainMatcher demonstrate excellent test-retest reliability [74, 75].

We took three measurements for each construct. Approximate intervals between repeated measurements were less than 5 seconds for testing the electrical perception threshold, 30 seconds for EPT, and 60 seconds for EPTo. Analysis evaluated the mean value of three measurements for each construct (Figure 2).

A B C

Figure. 2: Electrical stimulation tests: PainMatcher (Cefar Medical AB, Lund Sweden).(A). Electrical stimulation on the thumb of right hand (B and C).

Translation of commands and instruments (I-IV)

In Studies (I-IV), the procedures for translating the self-report questionnaires on demographics and pain characteristics, instructions for pressure pain measurements, and instructions for electric

stimulation tests involved translation, back-translation, review, and cultural adaptation into the languages of each culture to minimize any cultural misunderstanding of the original commands. The process followed the Guidelines for Translation and Cultural Equivalency by Ohrbach and colleagues, available on the International RDC/TMD Consortium website at http://www.rdc-tmdinternational.org/default. aspx.

Statistical analysis (I-IV)

In all Studies (I-IV), data analysis used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows and all tests employed a significance alpha level of P<0.05. In Study (I), the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test compared several variables on a nominal scale to determine whether differences between the pain and TMD-pain-free groups were significant.

In Study (II), a multiple logistic regression analyzed descriptive statistics of the samples, comparing education and marital status; independent variables included culture (Saudi, Swedish, Italian) and group (cases, controls). To test the primary study hypothesis, a two-way ANOVA (culture, group), including the interaction term, compared the mean values of each of the following variables: PPT, PPTo, electrical perception threshold, EPT, and EPTo. Since age and education differed significantly between the cultures, we adjusted the ANOVA models for these two variables. There were no significant interactions between any of the psychophysical dependent variables. When the ANOVA revealed a significant difference among the three cultures, we employed Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) tests for multiple comparisons.

We determined the minimum sample size based on published data using the same psychophysical measurement methods and assumed a significance level of α = 0.05 and power of 1-β = 0.90 for the comparison of the groups using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test. The threshold for clinical relevance was a difference of 60 KPa with a SD = 70. The calculations gave an estimated sample size of n = 40 for each group.

In Study (III), education was dichotomized to less than high school graduation vs graduation and beyond. Marital status was dichoto-mized to married vs not. Days of work reduction was dichotodichoto-mized

to none vs any, due to the highly skewed truncated distribution. A comorbid pain index was defined as number of pain sites by creating a variable ranging from 0 to 4 (i.e., count of back, chest, stomach, head) in each subject [29], in order to compare total number of pain sites outside the masticatory system.

Continuous variables (e.g., age, pain intensity) were analyzed with ANOVA while dichotomous variables (e.g., marital status, back pain presence) were analyzed with multiple logistic regression; independent variables included culture (Saudi, Sweden, Italy), case status, (TMD cases, non-TMD controls), and the interaction term. Among the three demographic variables, age and education differed according to the cultures and case status, respectively, and the planned models for all other variables were modified by including age and education as adjustment variables. For testing the primary study hypothesis, a two-way ANCOVA (culture, case status, and interaction term) compared mean values for each continuous dependent variable (average intensity, interference with daily activities) for each of the 4 pain conditions (back, chest, stomach, head). And, a similar logistic regression model was used for the dichotomous variables. When the ANCOVA revealed a statistical difference among the three cultures, Tukey’s HSD (Honest Statistical Difference) was used for multiple comparisons. A significance level of 0.05 was used in all tests, though marginally significant results are also identified due to the repeating pattern observed across the co-morbid pain conditions.

In Study (IV), a 2-test (chi-square) or Fisher’s exact test compared gender, education, and marital status. To assess patient data, we used a one-way ANOVA to compare mean values and, if the ANOVA revealed a significant difference between the three culture groups, Tukey’s HSD test for multiple comparisons of pairs of means. Because age and education differed significantly between groups, we used linear regressions to adjust for these variables to avoid any confounding effects.

5. RESULTS

Subject and pain characteristics (I-IV)

The 325 dental patients in Study (I) had a mean age of 29 ± 6. The 135 (42%) male patients and 190 (58%) female patients each had a mean age of 29 ± 6. The TMD-pain group consisted of 58 patients reporting TMD-pain: 79% were women and 21% men (P < 0.01). The TMD-pain-free group (n=267) was 54% women and 46% men without significant gender differences between the groups. Figure 3 shows the basis for selection of patients in the study.

Headaches or migraines in the last 6 months and headaches in the last month were reported in high frequecies in the TMD pain group, 93% and 71% respectively, with differences (P<0.01) between the TMD-pain and non-TMD pain groups. In terms of gender, 81% of females and 61% of males reported headaches or migraines in the preceding 6 months. GCPS grades for females in the TMD-pain group were mainly Grade II (57%), followed by Grade I (41%).

According to the RDC/TMD, a patient can be assigned 0–5 subdiagnoses (one diagnosis from group I, and one diagnosis each from group II and group III for each joint). All 46 patients had a myofascial pain diagnosis; 65% of the patients had a group III pain diagnosis and 22% had myofascial pain only (Table 1).

Figure 3: Selection of patients in Study (I). All consecutive patients between 20 and 40 years of age (1), patients who refused to participate due to lack of time, severe dental pain, or communication difficulties (2), patients who attended the interview and completed the questionnaire (3), patients who did not report TMD-related pain (4), patients who reported TMD-related pain (5), patients who did not attend clinical examination due to either no time or no interest (6), patients who were clinically examined and included in the study (7).

Table 1. Distribution of RDC/TMD subdiagnoses in 46 patients reporting TMD-pain. Subdiagnoses of TMD Males (N=7) Females (N=39) Total (N=46) N N N (%)

Myofascial pain (only)

Without limited opening 3 4 7 (15)

With limited opening 2 1 3 (7)

Myofascial pain combined with:

Arthralgia 1 25 26 (56) Osteoarthritis 1 3 4 (9) Osteoarthrosis 2 2 (4) Disc displacement: With reduction 0 11 11 (24) Without reduction,

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for female TMD cases & TMD-free controls.

P-values

Characteristics Saudis Swedes Italians Culture Case

status action Inter-N Cases Controls 39 39 41 40 42 42 Age (years): mean ± (SD

Cases Controls 32±(10) 34±(15) 40±(12) 0.01b,c NS NS 30±(12) 35±(14) 39±( 8) Education (≥ 12 years): N (%) Cases Controls 23 (59) 34 (83) 26 (62) 0.01b,c <0.01 0.03 36 (92) 37 (92) 31 (74) Marital Status (married):

N (%) Cases

Controls 10 (26) 20 (50) 25 (60) <0.01

b NS NS

15 (38) 23 (58) 29 (69) TMD Cases Only

Pain duration (months):

mean±(SD) 30±(28) 77±(79) 52±(72) <0.01a N/Ad N/A CPI: mean±(SD) 55±(24) 55±(21) 64±(20) 0.11 N/A N/A Activity interference:

mean±(SD) 24±(27) 21±(25) 52±(33) <0.01b,c N/A N/A Graded Chronic Pain:

Grade I–II : N (%) Grade III–IV: N (%) 34 (87) 5 (13) 32 (86) 5 (14) 24 (57) 18 (43) <0.01b,c N/A N/A a Significant difference between Saudis and Swedes, b Significant difference between

Saudis and Italians, c Significant difference between Swedes and Italians, d Not

applicable analysis due to cases only.

For Studies (II–IV), subject characteristics and, for the cases, pain characteristics are displayed in Table 2. The Italians were older than the Saudis and Swedes (P<0.01). Education years received did not differ across cultures, but fewer cases had received at least 12 years of education compared to TMD-free controls (P<0.01). More Italians reported being married compared to Saudis (P<0.01).

TMD pain duration was shorter in Saudis compared with the Swedes (Table 1; P<0.01). Pain intensity (CPI) associated with TMD did not differ cross-culturally. Average TMD pain intensity, as a component of CPI and serving as a comparison for the other pain conditions, was (mean±SD): 55±24 for Saudi, 55±21 for Swede, and 64±20 for Italian cases, with no cross-cultural differences. Disability days ranged 0-30