Smell, Memory

and Games

Exploring the potential of the sense of

smell in memory games

Maxime Barnier

Master thesis project -‐ Interaction Design Master at K3 Malmö University -‐ Sweden 2015

Supervisor: Simon Niedenthal Examiner: Jonas Löwgren Examination: 2nd June, 2015

Table of contents

Abstract ... 4

1.Introduction ... 5

2. Research focus ... 6

3. Literature overview and related works ... 8

3.1 An Understanding of smell and scents in our society ... 8

How the sense of smell works ... 9

The classification of smell ... 10

The power of smell ... 12

3.2 The human memory ... 13

Long-‐term store and Chunking ... 15

Training the memory of smells ... 16

3.4 Learning with games ... 16

Game and Gamification ... 16

Tangible product ... 19

3.5 Smell in game design ... 21

4. Methodology ... 25

4.1 Research through design ... 25

4.2 A Game design approach ... 25

5. Process and results ... 27

5.1 Defining an olfactory game sharpening the memory ... 27

Guess my face ... 27

Gameplay ... 28

5.2 Experiments ... 32

Prototype 1 ... 32

Prototype 2 ... 39

7. Reflect ... 49 Conclusions ... 49 Discussion ... 50 Further works ... 51 Acknowledgments ... 52 References ... 53

Abstract

This study is focused on the impact of smell on the memory in the context of games. The aim is to understand what the effects of smell on human’s memorization and learning process are. The research topic is explored through creating a memory game designed specifically for the study: “Guess My Face”. In this game, the players have to memorize pictures of faces parts using their specific scents. The game’s goal is to manage to compose a random face provided by the game with the face parts that the players learned. However, the difficulty lies in the fact that the players do not see the face parts pictures during the game and so, have to rely on their sense of smell alone.

The game intends to contribute to the research area in different ways. First, it provides a technological solution for involving the inclusion of smell in games by using smell boxes connected to the computer. Second, the playtestings of the game highlight issues that a game designer has to take account by involving smell: balancing the strengths of the scents, participants experiencing dizziness after smelling a lot of different scents, the amount of time that smells remain in the air, the fact that coffee can be used to neutralize scents. Finally, the game contributes to the exploration of the way that smell triggers memories and how it could help for enhancing learning.

Through the iterations of testing, the study reveals that smell is a sense that people do not often rely on for memorizing and they prefer visual memory. Moreover, we learn that players memorize pictures more easily when scent is involved, as they use several cognitive strategies or reflexes: characterizing the scents with adjectives or identifying their origin (fruits, woods), involving emotions (disgust, strangeness), and relying on personal experience (creating a link between a scent and picture thanks to the

memory of a person/object/event). This cognitive behaviour shows that smell has the potential to enhance memory by creating meaningful knowledge and making the assimilation of information easier, an arena that has been dealt with by George Miller in his ’chunking theory’ (Thompson et al., 2005).

1.Introduction

Since I started to work in interaction design, I intended to understand and explore the game design arena. This choice is based on the idea that games could be an efficient way to motivate people arouse their interest in a particular subject or activity that they usually would not deal with. For example, my last master project was focused on gamification and the learning process for children with Down’s syndrome. I analyzed the ways games could be adapted for this purpose. For this study, I wanted to go a step further by dealing with game design in more detail and exploring its limits. Working with the sense of smell was a proposition of Simon Niedenthal, a researcher in the area of smell and games at Malmö University. I chose to explore this topic, as it was an opportunity for me to deal with games from a different perspective. However, I saw that current trend in the digital area is to use smell for immersion enhancing. A lot of products and concepts started to come out, such as diffusion devices for laptops. Moreover, most of the previous work involving smell in digital media has dealt with immersion enhancement and, unfortunately, proposed experiences that did not work or caused too many issues (Niedenthal, 2012). As such, I understood that smell

remains opened for studies and could even open up potentials other than immersion. I remembered that smell has the particularity to bring back people’s memories. I saw this as a potential enhancement of games which uses memory and by extension, in my own work, another way to help the learning process within games.

This study aims to create a game that explores the potential of scents in human memory. As such, I would like to contribute for several domains. The first one is the game design area, as the project could contribute to a personal investigation of combining smell and games through rules, challenges, etcetera. Secondly, the

potential effects of smell on memory could contribute to psychological knowledge and could open up on new ways of learning. Finally, the domain of interaction design could be enriched by the technology developed during the project (combining smell and digital devices) and moreover, the project could contribute to the creation of new interaction design projects involving the effect of smells on memory.

2. Research focus

In the field of interaction design, olfaction is a topic still open for studies. The idea of combining scents and technologies appeared in the middle of the 20th century with

projects such as Aromarama1, which intended to add an olfactory immersion in a

theatre. However, the potential of such a combination remains blurry and researchers continue to build prototypes looking into the topic2.

The gaming industry is currently evolving thanks to new technologies which improve players’ experiences through the means of immersion. A noteworthy example is the Oculus Rift, which simulates real human vision in video-‐games, and is currently developing the means to extend its immersion potential to olfactics with the FeelReal add-‐on (see Figure1).

Figure1. FeelReal prototype, an Oculus Rift add-‐on providing seven different smells for game immersion (Ocean, Jungle, Fire, Grass, Powder, Flowers, Metal), as well as cool or hot blasts of air.

However, it seems that smell in games could provide more than just the potential of immersion. Smell has other impacts on human behavior that could expand on original gameplays, or even train cognitive processes through gamified applications or more serious games.

Smell and the memorization of past experience have a close connection, as illustrated by Jean-‐Pierre Royet et al. (2013) in their study of the impact of expertise in olfaction:

« […] the development of cerebral imaging techniques has enabled the

identification of brain areas and neural networks involved in odor processing, revealing functional and structural modifications as a function of experience. »

1 Henry Hart (2014). Innovations in Cinema: "AromaRama" - National Board of Review. 2015.

Available at: http://www.nationalboardofreview.org/2014/01/innovations-cinema-aromarama/

[Accessed 16 March 2015].

2 http://www.digital-olfaction.com/news-about-digital-olfaction/among-presentations-at-dos-2nd-world-congress-2014

In the novel ‘In Search of Lost Time’ (Proust, 1913), the author uses madeleine cakes as a vehicle to illustrate the ability of smell to trigger past memories. In the same way, using smell in games could be a way to handle memorization processes and perhaps to train the memorization of specific information.

Such a study could contribute on different levels. Firstly, as smell remains a sense with unknown potential, exploring the impact of olfactory interaction on memory could help researches to go deeper in the understanding of the relation between smell and cognitive processes. Secondly, as it seems that the brain shows improved potential for elasticity if we train our memory (Belleville et al. 2010) providing an example of memory training through games could open up the creation of tools for aiding the treatment of memory disorders, such as Alzheimer’s Disease.

Specifically, this study will explore the effects of scent on human memory and cognitive processes in order to create a specific olfactory memory game.

The method will follow a game design approach as the research will be fed thanks to playtestings of game prototypes. These playtestings will highlight issues and feedback about the game experience and the manner in which smell interacts with the players’ memorization mechanics. This information will then open up on game improvements and new iterations of play testing.

Research question:

How can a game be enriched by the effect of smell interaction on human memorization mechanics?

The study will first outline current understanding of the sense of smell, and will then focus on theories of human memory in order to understand more precisely how smell has an impact on human cognitive processes for memorization. Moreover, as the research aim is to create a memory game, we will talk about designing games and game knowledge that could improve the final product.

3. Literature overview and related works

3.1 An Understanding of smell and scents in our society

Humans do not rely often on their smell. This is understandable as 3.5% of the

information about our environment comes from our sense of smell, as opposed to 83% from sight and 11% from hearing (Gould and Roffrey-‐Barentsen, 2014). Smell can provide effective information for detecting danger (for example, smoke or gas) or checking food quality (rotten meat, soured milk), but society has moved away from using this sense as the primary alert for this kind of danger through such measures as expiration dates on food packaging and installing fire alarms in buildings.

In the ‘Foul and the Fragrant’ (Corbin, 1986), the author criticizes how the society came to deodorize the environment through the suppression of odours in public places and how that process made people intolerant to new scents. One of the sources in the book refers to epidemics, such as Cholera in 1832 France, which to led people avoiding crowds, public smells and sources of disease, and supported keeping to private, clean areas, i.e. houses. The idea of keeping away scents was sustained by the bourgeoisie social class who intended to maintain the “Purity rule.” This law involved using fragrance and fresh clothes in order to get rid of natural body scents and secretions referring to human’s bestial origin. Today, the tradition continues through the

expansion of the advertisement and manufacture of deodorisation products for use in the home and personal-‐hygiene.

However, even if humans being try as much as possible to limit their sense of smell, it remains the most important sense for other animals. Animals use this powerful sense for detecting prey and food, as well as for understanding their surrounding area and some species have a more developed sense of smell than others (Van Brakel et al., 2014). The dog’s nose, for example, is sensitive enough to smell and identify some forms of cancer in other species. Likewise, the bee has a very acute sense of smell, which is sensitive enough to identify the bacteria from human breath. Mosquitoes use their sense of smell to detect chemicals to evaluate the stress level and the presence of disease in potential prey, allowing them to choose the most desirable blood.

As we have seen, the human sense of smell, as well as its role in our culture, is

comparatively limited. Nevertheless, a powerful potential remains in that the sense of smell can trigger memories in human’s cognitive process.

How the sense of smell works

If we want to understand the origin of smells, we need to zoom in to the atomic level. Indeed, through the eyes of biologists, smelly elements are actually simple chemical components made from specific atoms. It seems it is possible to count on one hand the atoms that contribute to smells detectable by humans: nitrogen, sulphur, oxygen, carbon and hydrogen. Different combinations of these elements create the entire olfactory spectrum that we experience in our world. Although the identification of these “smell molecules” seems to be clear and understood in the scientific community, the specific way that these molecules are interpreted by the human brain is not fully understood. Two different theories exist which attempt to define it, the first is focused on molecule shapes being detected by our olfactory sensors, and the other deals with the wavelengths of the atoms. According to Luca Turin (2005), biophysicist in the science of smell, experiments have evidenced that smell molecules are specific depending on the vibrations they induce in our olfactory sensors. In that way, the smell molecules send neuron messages by triggering electron transfers thanks to their particular vibrations.

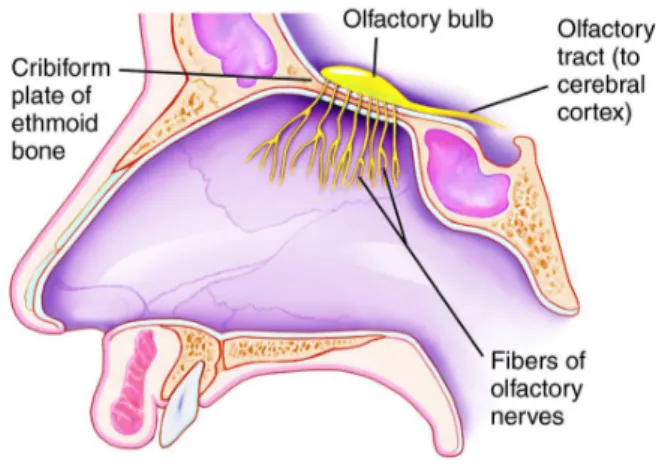

From a biological perspective, the area responsible for smell detection and identification is situated above the nasal cavity. This small system is comprised of olfactory nerve fibres that are stimulated by smelly components and detect around 350 signals. The stimulation of these nerves enable the identification of thousands of odours. The signals gathered in the olfactory bulb are sent to the brain via the nerves and interpreted in order to identify a specific smell (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Representation of the human olfactory system, University of Delaware.

It is important to highlight the role of pheromones as they contribute an important behavioural impact on life beings, and are an essential means of communication for

animals. Pheromones do not have to be mingled with scents and have different characteristics compared to that of scents. This idea is supported by the fact that pheromone sensors are separated from the olfactory bulb, even if they exist in the same area of the nose (Van Brakel et al., 2014). Pheromones are used by animals mostly to find a mate in order to reproduce. Ants rely on pheromones to communicate with each other and find food. However, for human beings the effect of pheromones is still a controversial subject, even if some maintain that they have an impact on

behaviour. As an example, an experiment showed that employees became cheerful, happier and more social when love pheromones were secretly spread in their office. Although pheromones remain a topic of interest and are still open to exploration, they will not be studied throughout this project, as they do not act on emotions and

memorization, but rather on behaviour.

The classification of smell

There is a complexity around the analysis and classification smell. Indeed, there is no efficient ways to describe a smell. As Jospeh Kay (2004) explains in his study of scent in HCI (Human Center Interface):

“The difficulty is that we have no good

abstract or higher-‐level categories, other than the smells themselves. What does mint taste like? Well...mint.” (Kay, 2004)

In addition, smells are subjective and this interferes with any attempts to make a smell classification system as everyone has their own opinions and tastes regarding scents. For example, a scent described as “floral” could not be identified as such if someone perceives it as unpleasant. In that way, it seems that the scientific area still struggles to create a reproducible and rigorous classification scheme for smells (Kay, 2004).

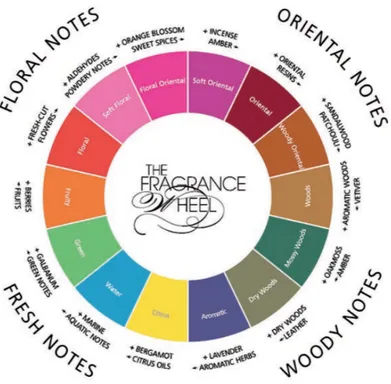

The domain of perfumery, however, creates its own classifications based on human’s perception of smells. One of the most known smell graphs comes from Michael Edwards (see Figure 3). Most perfumes today are based on this representation as it provides a clear vocabulary and logic for identifying and describing scents.

Figure 3. The Fragrance wheel developed by Michael Edwards in 1983. This representation is a modern one as the schema comes from “Fragrances of the world” published in 2010.

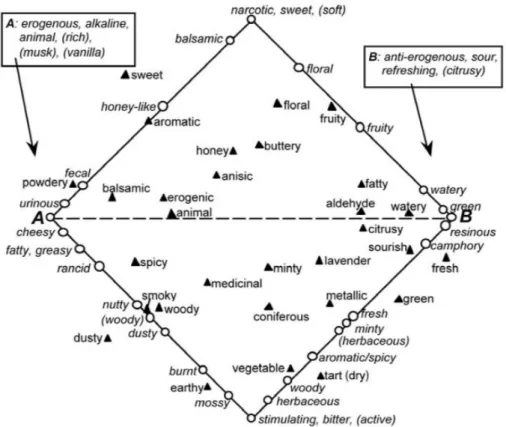

For Laura Dona (2009), who works as a fragrance coach by formulating the language of scent for customer services, smell is not as relative as people think. She presents the work of Zarzo and Stanson that, for her, found an efficient solution for developing a common scent classification. Based on the previous classification theories of Paul Jellinek (Smell mapping created in 1951) and the database of Boelens-‐Haring (list of scents compounds), they created a two dimensional sensory map of odor descriptors (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Two dimensional sensory map of odors descriptors by Zarzo and Stanson.

But this representation remains complicated for laypeople, and while the mapping provides a clear and detailed development of scent compounds, the simplicity of Michael Edwards’ wheel delivers a simple method for classifying scents.

The power of smell

Previously, we saw that smell for humans is limited and minimized in society compared to the other senses. However, the loss of smell could have serious consequences on human’s health and psychology. In fact, without smell, humans could experience a great change in quality of life quality and behaviour. A study has shown that patients with olfactory impairment can experience social isolation and anhedonia (the inability to experience pleasure).

From a biological perspective, smell has an impact on our eating behaviour as it triggers the craving of a specific food depending on which nutrients an individual may be lacking. This particularity extends to the stimulation of appetite for similar food: after exposure to a specific odour, such as banana, we develop an appetite for the food in question and related sweet products, for example, a chocolate brownie.

What is of interest in this study is the potential of smell to trigger memories. This particular experience is often illustrated through the example of Proust’s madeleine cakes. In his book ‘In Search of Lost Time’ (1931) the author talks about how the smell of cake dipped in tea brings back strong memories from his childhood. Madeleine episode became a touchstone for smell-‐memory studies and inspired poets as well as psychologists. Indeed, psychologists saw in Proust’s novel a concept to explore in order to understand the effect of scent on human memory. However, through the analysis of psychologist Avery Gilbert (2008), it seems that what Proust describes is not what most people experience when memories are triggered in their minds thanks to

particulars scents. Gilbert describes the fact that, in the process of reminiscing through scents, the emotional experience is automatic unlike Proust’s experience of him

himself triggering the memories. Moreover, Avery Gilbert highlights that Proust’s experience deals first with pleasure and emotions, and second with experiences, pictures, sounds and mood. Through this analysis, Avery Gilbert concludes on the fact that the scientific community used to base their research on a complex neuronal process that does not seem to be the one that people commonly experience by smelling scents.

Scientists explain that smell can trigger pictures, people, sounds and moods in our minds because of the proximity between the brain area responsible of the olfaction and the area dealing with emotions (Thompson et al., 2005). Another aspect shows that olfaction is connected with memory: a study has shown that the loss of smell precedes the onset of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia (Belleville et al., 2011).

Since the relation between smell and memory appears to be linked, we will continue on an understanding of human memory and its cognitive mechanisms.

3.2 The human memory

For Thompson et al. (2005), memory is the origin of consciousness since without memory, beings can’t have minds. The development of the memory seems to be at the very origin of the evolution of complex forms of life, as it remains at the genetic level. For example, some animals’ reflexes and behaviours appear to be assimilated at their birth. This understanding involves the fact that memory is not limited to the

memorization of simple information (pictures, sounds), but that it involves more complex processes and capacities.

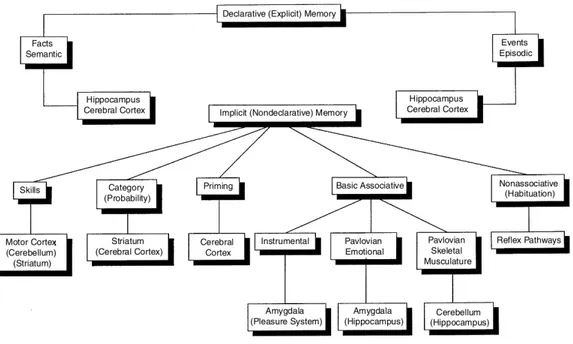

According to Thompson et al., memory is divided into several kinds of memory which deal with specific memorization mechanisms and occur in different parts of the brain (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Schema of the different types or forms of memory and the respective brain structure involved (Memory: The key of Consciousness, 2005)

On the one hand, we talk about declarative or explicit memories. This memory is the one that we are conscious of, that we can access just as easily as opening drawers from labelled shelves. This explicit memory is composed by semantic memories: the total knowledge of semantic sets (words, numbers, names) and episodic memory, dealing with memorizing events and experiences (What did you eat for breakfast? Which music did you listen yesterday?). According to Thompson et al. (2005), declarative memory is made up of short-‐term or “working” memory. This particular memory is the one that we often use to remember tiny pieces of information such as addresses, phone numbers etcetera, and it remains for just few seconds. The authors highlight that this memory is responsible for consciousness or awareness and even general intelligence.

On the other hand is Implicit, or Non-‐declarative, memory dealing with knowledge and information that we are not directly aware of. As an example, Thompson et al. (2005) talks about people who could refer to information that they heard during unconscious phases (Priming learning). Moreover, this kind of memory seems to be responsible for learning to walk and talk. In that domain, Pavlov’s work on conditioning comes into play. Conditioning was focused on behavioural changes induced by stimuli: The experiments from this research area showed that a subject could “learn” a specific behaviour by being stimulated by the same stimulus that triggered the behaviour in question.

Conditioning is dividing in several kinds of learning: the habituation (becoming insensitive to a repeated stimulus), associative learning (acting in response to a

stimulus), emotional learning (the stimulus involves emotions), instrumental learning (acting before the stimulus occurs), priming (presented above) and probability and category learning (get the right stimulus pattern the more you are stimulated). These aspects shows how declarative memory deals with unconscious memories and knowledge: we are not aware of these behaviours and reflexes, but our nerves become more and more familiar with these stimuli. Further proof that this non-‐ declarative memory process is innate for living beings can be found in that scientists discovered that foetuses became less and less sensitive to loud noises the more they were stimulated.

The memory involved in this study refers mostly to declarative memory and, more specifically, to “working memory”.

Long-‐term store and Chunking

Working memory has two aspects: short-‐ and long-‐term storage. The short-‐term store refers to data that we keep for few seconds or minutes.

In our study, we are going to focus on the understanding of long-‐term storage. The most common way to memorize is through repeating information. This process, called “maintenance rehearsal” is limited, as a single distraction could erase the retained information.

However, studies show that there are other methodologies that help in the memorization of information long-‐term. George Miller, a specialist in cognitive psychology devised the chunking memory, also translated as “psychological or

perceptual unit” from Thompson et al. (2005). This theory explains that we memorize through chunks of information (units of information). In the example presented by Thompson et al. (2005), there are twelve chunks (12 letters). However, as the order creates simple words, the chunk is reduced to 3 (see Figure 6). The logic is the smaller a chunk is, the easier it is to memorize.

Figure 6. The original test involved twelve different letters. In this case, the letters form three distinctive words that make the letters memorization easier.

The process to reduce the chunk remains in our ability to recode information into something familiar and meaningful. The example from the Thompson’s book (2005) presents an amateur runner that memorized about 70 digits by linking the number pattern with times made in world record running.

Based on the theory of chunks, the ability to memorize depends on the depth of processing, or in other words, how many layers of logic are needed to reach the information to memorize. In that way, chunking is a way to learn which draws upon the knowledge we have already assimilated.

Training the memory of smells

According to cognitive science, working memory is trainable and could improve several cognitive skills depending on specific exercises (Morrison & Chein, 2010). In this way, it seems that mental tasks such as multitasking, attention or the speed of mental

processing could be trained and improved. The long-‐term store seems open for training the acquisition of specifics, chunking or mnemonic process like, for example, memorising smells.

Thompson et al. (2005) explain that a short-‐term sensory memory for smell exists, but has the same default compared to the visual one as it can preserve information for brief periods, and could be subject to a lot of interferences.

However, using the chunking process could be a way to assimilate smells: as scent can be described with knowledge of basic adjectives (wood, floral, oriental, fresh) the process seems easy. However, according to Joseph Kay, using adjectives for describing smells is not that effective. A better option would be to assimilate scent with known object or person (leather, tomato, roses).

There exists another way to memorize smell, but it involves prior-‐knowledge of a basic smell classification system. This process involves identifying smell components, but this strategy is very limited because, as Andrew Livermore and David G.Laing (1998) explain in their study, most people can identify around 3 or 4 different scents from a mixture, even if it is made of just a few molecules. This is the associative process. If this limit is reached we will experience the mixture as a whole scent (associative process).

Through this analysis, training the memorization of smell seems to rely first on training the assimilation of the scents with objects and elements known and second, on

extending its own vocabulary for classifying the scents.

3.4 Learning with games

Game and Gamification

Before getting deeper into the understanding of gamification, we are going to focus on the basic definition of “what is a game?” For Caillois (2001), the answer is clear and involves six parameters: free, separate, uncertain, unproductive, governed by rules, and make-‐believe.

A game is free as it is not mandatory, the player has the choice to get involve or not within the game. A game is separate with limits of space and time that were defined in advance. ‘Uncertain’ refers to the fact that the outcomes of games are not previously known or defined. A game is unproductive as no good is created within the game. Rules are set and practicable only within the game. And finally, a game puts the players in a fake reality as opposed to real life.

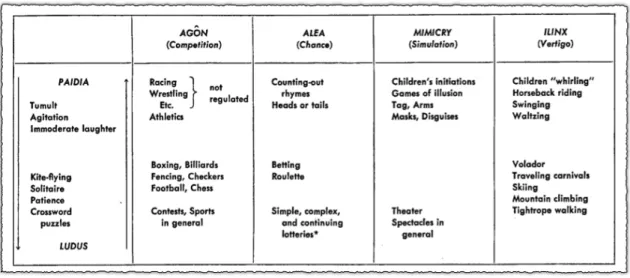

Additionally, Caillois (2001) defined different categories of game: Agôn (competitive games), Alea (games of chance), Mimicry (mimic games), and Ilinx (games involving sensations such as fear, dizziness, etcetera). Moreover, Caillois (2001) makes a distinction between two different kinds of “play”. While one (Ludus) refers to ruled and measured activities, the other (Paidia) allows the player to create and improvise. Combined with the four categories, Paidia and Ludus play offer a large range of games, defined in Caillois’s table (see Figure 7). This definition of play has been a basis in the game design arena as it enables the categorisation of practically all games.

Figure 7. Caillois’ categories of play table. (Caillois, 2001)

This classification is used by Katie Salen (2004). Compared to Caillois’ table, the

authors make a distinction between play and games, and present their relation to each other. There are two ways of thinking: game is part of game or play is part of game. However a general thought underlines the definition of each term: On one hand, “Play” refers to every kind of playful activity more or less organized and mostly open to “free” actions exploration. On the other hand, games refers to playful activities with clear and explicit rules. Specifically, the author shares a clear definition of game:

« A game is a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome. »

Conversely, Katie Salen (2004) describes toys as a kind of play that does not have rules or specific goals.

From this understanding, the author highlight one particular kind of game: puzzles. For them, puzzle games are special in the way that there is a single solution for succeeding within the game system.

With the development of the Internet and the rise of video games, the beginning of the 20th century welcomed a new form of playing. Games started to be integrated in

our daily life by way of gamification. Gamification was known has a manner to motivate and arouse the interest of people for non-‐ludic activities.

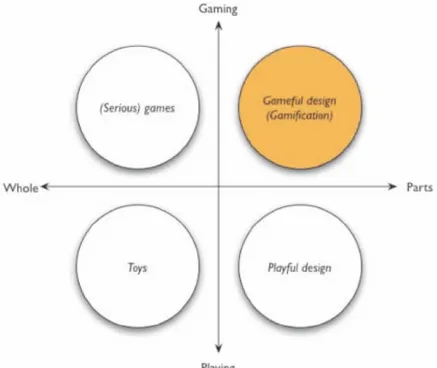

From the perspective of Sebastian Deterding (2011), gamification can be defined through two parameters, “game”-‐“play”(understood as “ludus” and “paidia” from Caillois’s definition) and “whole”-‐“part” (see Figure 8). By such, Deterding explains that what makes gamification different from toys, serious game, and games is its focus on game design elements rather than a whole game.

Figure 8. Gamification definition schema (Deterding, 2011)

More precisely, gamification uses components or elements from games that arouse interest and motivation. Some examples of these elements are known as leader boards, profile statuses, ranks and badges. But the list remains blurry as people from

different domains (games, marketing) define their own “motivating game elements” depending on their own marketing strategies (Priesbatsch, 2010).

According to Sean A. Munson et al. (2014), the efficiency of gamification comes from its power to change tedious activities into meaningful and motivating experiences. By using the example of health care, the author defines the potential of the gamification for making people change their behaviour. Munson et al. (2014) base their research on behavioural theories and explains that gamification has the role of triggering the right psychological lever in order to make people motivated.

For Munson et al. (2014), there are three different ways for health tracking: personal informatics, games and gamification. Personal informatics is defined as a tool that collects and interprets data from one person (step counter, sleep tracker, etcetera). In that case, the concept is simply providing information to the user. On the other hand, games are presented as engaging fantasies that motivate the player through its task by providing goals and fast feedback on the accomplished task to succeed in these goals. The challenges that games provide through their goals make failure fun. The

motivation power of games is also highlighted in the idea that they could make activities really immersive thanks to well-‐written stories. In that way, emotions in games have an actual impact on the player’s motivation. Moreover, games could display statuses that make the evolution of the player progressing in the game visible. This opens the possibilities of ranking and competition that, in turn, make the activity even more challenging and motivating. This also explains that sharing and competition make the activity more social, and make the player think that they are part of a

community with players who support each other. From this understanding of games, the author explains that gamification is situated between personal informatics and games. In other words, gamification could have the role of providing actual

information from the “real world” while providing a singular playful experience that motivates the player to gather and play with this data.

This opens the possibilities of how many mechanics gamification could keep from games in order to provide the motivation required for the players.

As we saw, gamification provides an interesting aspect of games regarding a potential to arouse interest and motivate the players to do tasks and activities. In this way, elements from gamification seem to be accurate for the development of this thesis project, as it involves an assimilation of scents from the player.

Tangible product

Embody interaction is a concept described by Paul Dourish (2001) and defined as:

In other words, embody interaction refers to how digitalized systems integrate our physical and social environment. In our case, embody interaction could be understood as the potential of using tangible object for digital game.

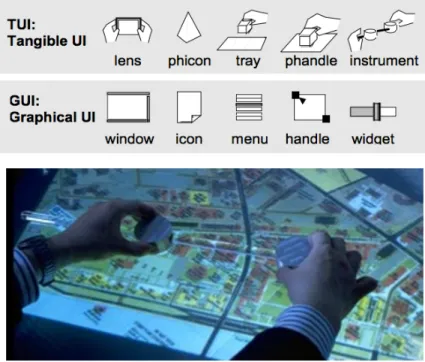

As Dourish (2001) explains through the example of MIT Media Lab’s project “Tangible Bits” (see Figure 9), there is a trend that intends to digitalise tangible tool we

commonly use. The watch is one of the examples, as the time is now displayed on most applications. However, it explains that even if digital and physical media seems to be informationally the same (they provide the same information) the manner of how we interact with them is different: they are not interactionally equivalent. That is to say, extracting digital elements and making them tangible is actually meaningful as it provides another experience.

Figure 9. “Tangible Bits” explores the relation between Tangible and Graphical elements from a user-‐ interface and how these two domains are linked. The project proposes three prototypes: metaDESK, transBOARD and the ambiantROOM. (Dourish, 2001)

From a game design perspective, the idea to combine digital and tangible elements is an emerging concept supported by the development of mobile devices. Indeed, these technologies, combined with our surrounding objects, offer a new panel of

interactions for games. The Volumique Editions explore this potential through a large panel of projects combining tablets, smartphones, books and board games (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. “Les éditions Volumiques” is a group exploring the potential of combining books and tangible objects with mobile devices. Their aim is to give a second life to non-‐digital objects such as books that still provide interesting interaction potentials.

One of the interesting points to deal with in relation to a tangible object is its impact on the learning process. Studies show that incorporating a tangible object in teaching material for children could help them to learn 15% more efficiently (Fumard, 2014). However according to Paul Marshal (2007), tangible interfaces in the learning process does not seem that efficient, as the possibilities of learning enhancement are different from one project to another. As such, a tangible object should be carefully designed to fit in with the learning goals (Marshal, 2007).

As this study’s game will involve learning and recognizing smells, the interaction within the game could improve the learning process of the player, thanks to concrete objects.

3.5 Smell in game design

In this section, we will define an understanding of games that involve smell and

The use of smells in board games aims mostly at children, with the purpose of allowing them to discover and explore the scents. For adults the same purpose exists, but it presents another facet as it contributes refining the player’s smell acuity. Such games involve, for example, identifying the components of a wine (see Figure 11). In these cases, the player’s main goal is to guess one or several scents from the game materials and create a “personal library” of scents from exploratory learning.

Figure 11. “Le nez du vin” is a board game aiming for a discovery of wine compounds and the development of smell acuity for identifying them. (Editions Jean Lenoir)

The designer Max Vandewiele goes further in the guessing process. His “Smell factory”

game project involves the players ‘scent hunting,’ where identification is the key for succeeding (see Figure 12). Indeed, in this game the player has to identify specific smells from mixtures. By such, the game explores the associative and dissociative process highlighted by Andrew Livermore and David G.Laing G.Laing (1998).

Figure 12. “Smell factory” by Max Vandewiele

The “Spice chess” of Takako Saito explores sensory interaction with the chess pieces (see Figure 13). In this version of chess, the pieces do not have a shape and the player can only recognize each piece’s role (queen, rook, pawn, etcetera) by smelling the boxes. Here, Takako Saito triggers an identification process by using smells. The players can only rely on their sense of smell while playing and have to smell the box to have an understanding of the game state for developing their strategies. From this perspective, “Spice chess” deals with memorization because of the cognitive process involved (e.g. players know that piece X is the pawn because it smells like ginger). With deeper analysis, this game could contribute interesting knowledge to the

understanding memorization triggered by smells.

Figure 13. “Spice chess” by Takako Saito (1964-‐65)

The development of technologies such as Oculus Rift and the rise of video games introduced the sense of smell into games in order to improve their immersive

potential. Different plug-‐in technologies have appeared recently which trigger scents according to the game content displayed on the screen (see Figure 14). This is a hot topic as different companies intend to propose their own scent diffuser technology. However, their efficiency and immersive potential have not been clearly proved so far.

Figure 14. On the left, GameSkunk developed by Sensory acumen (2011), on the right, ScentScape developed by Scent Science (2011). Both are technologies which plug into a computer or console and

spray scents specific to the game or video being played.

From this brief analysis of smell involved in games, we can see that memorization appears mostly in exploratory games like “Le Nez du vin” in which the player learns the wine compound and Takako Saito’s “Spice chess”. As such, the gaming arena is still holds much to explore where scent and memory processes are involved.

4. Methodology

4.1 Research through design

As this study involves designing a game, which explores specific domains, the project’s methodology will be based on a combination of research and design.

Recently, HCI (Human-‐Computer Interaction) researchers studied the potential of using design in the research area by formulating research through design (RtD) (Zimmerman et al., 2007). In the case of Interaction design, Zimmerman et al. (2007) identified three main values (or aims) that the discipline brings to the research process. The first deals with reducing constraints in the research process, meaning that design does not take account of boundaries that the context of research in HCI has set (economic or technological constraints, for example). The second point refers to the potential of design to bring ideas from art and design in order to produce functional and aesthetical products. Finally, design uses empathy to shape its research outcomes, or thinking about how to design efficiently for specific users. For Jonas Löwgren (2013),

the essence of design in research is to create artifacts. An artifact, from an RtD

perspective, is a concretely designed outcome of the research process that provides specific knowledge from the topic studied (Gaver, 2012).

During this research, RtD will be treated as a strict methodology that would involve creating artifact such as storyboards, sketches and games prototypes each times that there is a specific question, topic, idea to explore. Each one will be carefully described with annotated portfolios: sharing my design aims and contributing to a specific knowledge of my research (Löwgren, 2013).

4.2 A Game design approach

For Tracey Fullerton (2004), game design methodology involves an iterative process divided into specific phases: generating ideas, formalizing ideas, testing ideas and evaluating the results. If there is a problem with the design, the idea makes another loop in this iterative process (see Figure 15).

Figure 15. Iterative process applicable for game design perspectives (Fullerton, 2008)

My methodology is inspired by this process as I will generate ideas through

storyboards, formalize my ideas with the materials needed (crafting, coding) and test the game through playtesting. However, the reiteration will not be triggered by design problems alone, but rather if a question or an interesting potential dealing with

memory and smell highlighted through the play testing would need more exploration.

My role as a designer will be to design a game artifact for specific players. The MDA approach explains that this design process involves three layers: Methods (setting the game rules), Dynamism (creating the game system) and Aesthetics (designing what

makes a game “fun” or describes the emotional response of the player) (Kim, 2015).

The process suggests that I will create the game artifact by consideration of the methodology, whereas the player will experience the game primarily through the game artifact aesthetics (see Figure 16).

Figure 16. the MDA approach (Robin Hunicke,)

However, as I need to understand the pIayer’s experience while playing the game artifact, in order to improve the game I will have an empathic approach that will involve designing the game from the perspective of both the designer and the player (see Figure 17).