The effect of conscious

consumerism on

purchasing behaviors

The example of greenwashing in the cosmetics industry

THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration

NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Double degree program

AUTHORS: Manon BERNARD, Lilana PARKER

TUTOR: Jasna POCEK

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Authors: Tutor: Date: Key terms:The effect of conscious consumerism on purchasing behaviors: the example of greenwashing in the cosmetics industry

Manon Bernard and Lilana Parker

Jasna Pocek

2021-05-24

Purchasing intentions, purchasing behaviors, greenwashing, cosmetics industry, consumer skepticism

Abstract:

Background:The green market has boomed in the past few years in many industries including the cosmetics sector and businesses must now recognize sustainability as part of their overall business strategy. More specifically, the natural and organic beauty market has grown at an unprecedented rate in the last decade. The pressure on businesses to respond rapidly to rising customer demand for green goods has resulted in a deceptive marketing tactic known as "greenwashing." Although, many obstacles have created a gap between the intention to purchase and the actual purchase of green alternatives preventing organizations from benefiting from greener strategies.

Purpose: The purpose of this research is to learn about consumer behaviors when it comes to

green consumption and how greenwashing affects their buying decisions in the cosmetics industry. In addition to that, conducting a cross-cultural study brings insights on the impact cultural background can have on shaping green consumer profiles.

Method: The research is a qualitative study using an interpretivist paradigm. In addition to that,

the study follows a grounded theory approach. In order to collect primary data, in-depth interviews were conducted with nineteen participants from fourteen different countries.

Conclusion: Three key factors affecting customers’ buying intentions in the cosmetics industry

emerged from the results as well as four barriers preventing consumers from adopting green purchasing behaviors.

Acknowledgement

First and foremost, we would like to express our heartfelt appreciation to those who have helped us with our thesis.

We would like to start by expressing our gratitude to our tutor Jasna Pocek. We received a lot of valuable insight and input from her during the process. Without her involvement and encouragement, this study would not have been the same.

We would also like to thank all the participants that took part in our interviews. They invested time and provided us with their perspective on our topic. This research would not have been possible without their contributions.

Finally, we would like to thank the opposing groups for challenging us in interesting debates and providing constructive input during the seminars. It has allowed us to keep on improving our study.

Table of contents

I. Introduction: ... 7 1.1 Background ... 7 1.2 Problem discussion ... 8 1.3 Purpose ... 9 1.4 Research questions ... 101.5 Contribution to the research ... 10

1.6 Delimitation ... 10

1.7 Structure of the report ... 11

II. Frame of reference ... 12

2.1 Method ... 12

2.2 Conscious consumerism ... 13

2.2.1 The cosmetics industry ... 13

2.2.2 The green consumer profile ... 14

2.3 Greenwashing ... 16

2.3.1 Definition ... 16

2.3.2 The different forms of greenwashing ... 16

2.3.3 Lack of regulations ... 18

2.3.4 Origins and effects of greenwashing ... 18

2.4 Consumer perception ... 19

2.4.1 Factors influencing intentions ... 19

2.4.2 Consumer attitudes ... 21

2.4.3 Obstacles to green consumption ... 21

III. Research Methods ... 23

3.1 Research paradigm ... 23

3.2 Research approach ... 23

3.3 Research design ... 24

3.4 Sampling method ... 25

3.5 Data type & form ... 26

3.6 Data collection tools and process ... 27

3.7 Data analysis... 30

3.8 Ensuring trustworthiness and consistency ... 30

3.9 Ethical consideration ... 32

4.1 Social influences ... 34

4.1.1 Social media ... 34

4.1.2 Relatives ... 34

4.1.3 Trends ... 35

4.2 Quality and product performance ... 36

4.2.1 Product Performance ... 36

4.2.2 Health ... 37

4.3 Barriers to green consumption... 37

4.3.1 Financial barrier ... 37

4.3.2 Education ... 38

4.3.3 Convenience barrier... 39

4.4 Consumer skepticism ... 40

4.4.1 Advertising and Packaging ... 41

4.4.2 Greenwashing ... 42

4.4.3 Consumer trust ... 43

4.4.4 Information ... 44

V. Analysis ... 46

5.1 Consumers purchasing intentions ... 47

5.2 The impact of greenwashing on purchasing behaviors ... 50

5.3 Barriers ... 51

5.4 The evolution of the consumer’s role ... 53

VI. Conclusion... 55 VII. Discussion ... 56 7.1 Theoretical contributions ... 56 7.2 Implications ... 56 7.3 Limitations... 57 7.4 Future research ... 57 VIII. References ... 59 IX. Appendix ... 66 8.1 GDPR consent form ... 66 8.2 Interview guide ... 68

Tables

Table 1: Selection process for the Frame of Reference ... 13 Table 2: Data Breakdown ... 29

Figures

Figure 1: Data analysis outcome ... 33 Figure 2: Influences on consumers’ purchasing intentions and the impact of greenwashing on

7

I. Introduction:

This first part provides the readers with a background of the study and presents the purpose and the research questions of the study. The contribution to the research is explained in this section as well as the delimitations of the study.

1.1 Background

Concerns about global warming and emissions, growing consumer understanding of environmental issues, and environmentally friendly supply chains are all putting pressure on businesses to behave responsibly (Kahraman & Kazançoğlu, 2019). The depletion of natural resources has raised the issue of environmental protection, which has resulted in the development of environmentally friendly consumption known as "green consumerism” (Moisander, 2007). Consumers are becoming increasingly conscious of their power when it comes to making ethical purchase decisions, and they believe that by changing their purchasing habits, they can affect ethical dilemmas (Gillani & Kutaula, 2018). The green market has boomed in the past few years in many industries with green energy, sustainable fashion, organic food and green cosmetics, to name just a few. Green is a term defining practices or products “that will not pollute the earth and are less harmful to the environment than the standard alternatives in terms of polluting the earth or depleting natural resources and can be recycled or conserved” (Shamdasani et al., 1993).

With 75% of millennials actively looking to make greener changes in their homes and lifestyles (Glass Packaging Institute, 2014), organizations can no longer focus merely on generating profit but must consider corporate social responsibility in their business strategy. Indeed, consumers expect companies to be involved in environmental or philanthropic causes (De Jong et al., 2017; Krafft, & Saito, 2015; Kotler, 2011). Companies recognize the growing demand for green products and are shifting their strategies by implementing sustainable practices such as green marketing (Riccolo, 2021). Aji and Sutikno (2015) define green marketing as “a concept and

8

strategy adopted by a company to advertise its green practices as an expression of its concern for environmental issues”.

Research has highlighted the fact that it is difficult to predict green behavior therefore we cannot define a specific green consumer profile even though Krafft and Saito (2015) have identified three major profiles (Cervellon et al., 2011; Gabler et al., 2013). Besides, many barriers have created a gap between the intention to purchase and the actual purchase of green alternatives which have consequently prevented companies from benefiting from greener strategies (Gabler et al., 2013; Cervellon et al., 2011; Tsakiridou et al., 2008). As there are many different consumer profiles, Gabler et al. (2013) have suggested conducting cross-cultural research to understand if countries were an influence on shaping these profiles as his research was only conducted in the United States. Busic et al., (2012) cited from Newholm and Shaw (2007) that very few studies have undertaken cross-country comparisons of ethical consumerism. The goal is to obtain a more accurate interpretation of ethical consumption thanks to a cross-cultural investigation.

Following the movement of organic food consumption, consumers have realized the importance of using green cosmetics. In addition to the national beauty industry exploding, the natural and organic beauty market has seen exponential growth in the last decade and is expected to reach $25.11 billion by 2025 (Riccolo, 2021). However, eco-friendly cosmetics contribute to less than 15% to the total market value of the global cosmetic industry (Bhawna, 2020).

The necessity for companies to adapt quickly to the rising consumer demand for green products has led to a deceiving marketing practice: greenwashing (Krafft & Saito, 2014). Due to ambiguous regulations and a lack of clear marketing guidance, many companies are able to bypass marketing legislation and use greenwashed claims in their advertising without punishment (Krafft & Saito, 2014).

9

As green products have become increasingly popular in the marketplace, more consumers have looked for eco-friendly alternatives (Kim & Chung, 2011; Nimse et al., 2007). However, some consumers are outraged, claiming that many businesses are misrepresenting their products as being greener than they really are (Hsu, 2011; Aji & Sutikno, 2015). As consumers are being more suspicious of organizations’ eco-friendly claims, they are now questioning the act of buying “green” products. This distrust for corporate green communication has led to consumer skepticism (Krafft, & Saito, 2015; Darnall et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2008).

A lot of research has been conducted to understand greenwashing practices, but few have addressed consumer behavior regarding green products (Cervellon et al., 2011). While sustainable initiatives have boomed in many industries such as green energy, food, tourism, packaging, fashion, architecture, government, and construction;the cosmetics industry has been overlooked by the existing research (Nguyen et al., 2019). The authors will observe the gap between consumer green purchasing intentions and the consumer's actual purchasing behavior as scholars have tried to understand why individuals lean towards ethical consumption but fail to change their purchasing behavior (Baek et al., 2015; Cherry and Caldwell, 2013; Kim et al., 2016; Yoon et al., 2016). This problem will be approached through the consumer’s perspective. In addition to this point of view, the authors have chosen to apply a cross-cultural perspective as it was suggested as a future research direction by Gabler et al. (2013). With the amount of information at their disposal nowadays consumers are able to make their own research and can more or less identify the “greenness” of a product. Therefore, the objective is to understand the consumer’s attitude when purchasing personal care products and when confronted with greenwashing, with a special focus on the belief-behavior gap.

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this research is to understand consumers’ perception of greenwashing and the effect it has on their purchasing behavior. This thesis contributes to the research by completing the gaps previously identified such as the belief-behavior gap as well as the cross-cultural research and understanding consumer behavior when it comes to green consumption (Gabler et al., 2013; Cervello et al. 2011). This research has an exploratory purpose combined

10

with a theory development purpose (Collis & Hussey, 2013). In other words, the purpose is to identify patterns about a phenomenon and build a theory from it. In this particular research, the authors will describe how the consumers perceive and react to greenwashing and develop a theory to understand how the purchasing behaviors have evolved due to greenwashing.

1.4 Research questions

The basic research problem must be sufficiently centered so that a reasonably homogeneous group of people can share their experiences with the subject. The study will address the following research questions:

Q1: What factors influence consumers’ purchasing intentions in the cosmetic industry?

Q2: How has greenwashing in the cosmetics industry changed consumers’ purchasing behaviors?

1.5 Contribution to the research

This research will add to the understanding of how consumers perceive green cosmetics and how it is impacting their purchasing behaviors. This study will help companies and marketers understand consumers behaviors towards green cosmetics. It will also give insights to companies and marketers thinking about orienting themselves towards a more sustainable business model or to consumers thinking about adopting a different way of consumption.

1.6 Delimitation

It is important to note that this study does not try to understand the whole concept of greenwashing, both from an organization’s and a consumer’s point of view. In fact, the research focuses on the consumer’s perspective. Moreover, the study is limited to the cosmetics industry

11

therefore the results may not be transferable to understand consumers’ purchasing behaviors in another industry.

1.7 Structure of the report

The thesis is composed of six main parts. It starts with an introduction of the topic and the problem studied. The second part is the frame of reference which presents some insights regarding the topic and previous research done. The third part explains the different methods used to collect data and answer the research questions. The empirical findings are then presented and analyzed. Lastly, the authors conclude by answering the research questions and discussing the limitations of the study.

12

II. Frame of reference

This part summarizes previous research and literature on the topic of greenwashing in the cosmetics industry. The concepts presented in the introduction are further explored to serve as a basis for the interpretations of the findings which will allow the development of a theory.

2.1 Method

The frame of reference investigates knowledge and previous research related to the topic of this study. The following section is divided into three parts, the first one examines the field of conscious consumerism and the rise of this movement. The second part analyses the different theories around greenwashing, how this phenomenon emerged and how companies apply it in their strategies. The last part focuses on consumer perception and behaviors, and highlights the gaps identified during the research. In order to find relevant scientific articles, the research was done through databases like Google Scholar, Jönköping University Library Primo and Kedge University Library.

To keep track of the research, two Excel files were created, one classifying all the keywords search on databases with the number of results found, and another one describing relevant articles found with for each article: the name of the authors, the main topics approached (keywords), a summary, personal comments, future research suggested by the article and the link to the article. The last file helped gather previous knowledge and figuring out what future research could complete this already existing knowledge. The main keywords to find relevant peer-reviewed articles were conscious consumerism, green marketing, greenwashing, cosmetics industry, purchasing behavior, consumer skepticism and green cosmetics. Moreover, the recency of the article was a criterion in the selection of articles for the frame of reference.

13

Frame of reference

Data bases Jönköping University Library Primo, Google Scholar, Kedge University Library

Main theoretical fields

Marketing, Sustainability, International Management

Search words Conscious consumerism, green marketing, greenwashing, cosmetics industry, purchasing behavior, consumer skepticism, green cosmetics Literature types Academic articles, books, review articles, scholarly journals

Criteria for article selection

Peer-reviewed articles, key words, recency

Selected articles 42 articles

Table 1: Selection process for the Frame of Reference

2.2 Conscious consumerism

The rising environmental threat of global warming and pollution has created a need for sustainable practices from organizations and responsible consumerism making the green trend a part of the world economy (Cervellon et al., 2011). Many consumers are willing to pay reasonable premium prices for environment‐friendly products, due to environmental and health concerns (Kahraman & Kazançoğlu, 2019). Conscious consumption is a lifestyle that recognizes that individual consumption has larger consequences than a mere private impact and that consumer power can transform society. As a consequence, consumers voice their values by purchasing from socially responsible companies and by boycotting unethical companies (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014; Vitell et al., 2015; Zollo et al., 2018). However, ethical purchases produced with fair wages and worker treatment and made sustainably can be impractical and quite expensive (Husted et al., 2014; Zollo et al., 2018).

2.2.1 The cosmetics industry

Consumers are increasingly interested in a green lifestyle as they expect personal benefits from green products in addition to them being environmentally friendly (Nguyen et al., 2019). Some chemicals have been proven to be highly polluting as well as harmful for our body. Because an

14

increasing number of individuals have decided to adopt a healthier lifestyle, a growing number of consumers demand healthier cosmetics that will be gentle on the skin and minimize the harm to the environment (Stone et al., 1995). Cosmetics is a billion-dollar market, Germany alone generates 6-billion-euro sales per year (190 €/ second) (Cervellon et al., 2011). Cosmetics have been defined in the section 201(i) of the U.S Food Drugs and Cosmetics Act (1938), as a product, except soap, “intended to be applied to the human body for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering the appearance”. The Act adds that cosmetics may also be considered as a “product intended to exert a physical, and not a physiological, effect on the human body”, and that “the raw materials used as ingredients of cosmetic products are by law also cosmetics”. The first line of organic cosmetic was launched towards the end of the 70’s by Dr Hauschka. However, it is not until two decades later that major cosmetic brands adopted the organic concept and decided to create greener alternatives such as Beauté Bio by Nuxe and Agir Bio Cosmétiques by Carrefour. By 2011, the European market for organic cosmetics was growing by 20% every year (Cervellon et al., 2011). Green cosmetics have become a symbol of well-being and environmental responsibility in the cosmetics industry due to their long-term benefits on health and the protection of the environment (Jaini et al., 2019). In fact, using green cosmetics is now part of a lifestyle based on self-care and sustainability (Lin et al., 2018).

2.2.2 The green consumer profile

Krafft and Saito (2015) have identified three types of green consumers. The first type is the health-conscious consumer whose main objective is to purchase products for health benefits. The second one is the environmentalist, whose major concern is to protect the planet and finally the quality hunter, whose beliefs are that green cosmetics have superior benefits. McEachern and Mcclean (2002) define green cosmetics as a multifaceted construct for environmental protection, pollution reduction, responsible use of nonrenewable resources, animal welfare, and species preservation. Research has highlighted the fact that it is difficult to predict green behavior therefore we cannot define a specific green consumer profile but rather a diverse range of profiles (Cervellon et al., 2011; Gabler et al., 2013). In addition, Ajzen (1985) stated that if a person has a positive mindset when engaging in a particular activity, they will be more likely to do so. Indeed, as Peattie (2010) noted, although field research has revealed variations between countries and cultures, there are striking similarities in the growing environmental

15

values, concerns, and interest in green consumption. Various studies back the positive relationship between consumers' attitudes and green purchasing intentions in different cultures, such as Asian, American, and European. This relationship works in different product categories (Chan & Lau, 2001; Kalafatis et al., 1999; Tarkiainen & Sundqvist, 2005; Kim & Chung, 2011). According to Shah (2013), a green consumer is one who is aware of environmental concerns and responsibilities, a consumer who is committed to environmental causes to the point of switching from one product to another even if it comes at a higher cost. A green consumer is an individual who aims at purchasing eco-friendly products. Products that have minimal to no packaging, made from natural materials, and made without polluting the environment are all examples of eco-friendly products (Shah, 2013). Besides, cruelty free products attract green consumers as animal welfare is becoming a major motivator with the expansion of the vegan lifestyle. Finally, some research has also demonstrated that the typical green consumer is usually wealthier and more educated than the average consumer but there has been a democratization of green purchasing especially in Europe and North America (Cervellon et al., 2011).

Conscious consumerism is a trend being driven by consumers who make purchasing decisions based on their core values rather than “income, demographics, geography or other factors” (Godwin, 2009). Consumers' motivational attitudes are impacted by their level of ethical awareness. In fact, social motivators are more powerful than personal motivators in influencing ethical conduct (Freestone & McGoldrick, 2008; Bucic et al. 2012). Even though this trend is a growing movement, research has mentioned that consumers’ biggest concerns are the elevated prices, product performance and a lack of choice (Cervellon et al., 2011). These barriers have created a gap between the intention to purchase and the actual purchase of green alternatives (Tsakiridou et al., 2008). A good example of this gap is the study by Cowe and Williams (2000) in which they found that in the United Kingdom, “more than one third of consumers described themselves as ethical purchasers, when ethically accredited products such as Fair-Trade lines only achieved a 1-3% share of their market”. In this phenomenon, 30% of consumers claim to have a conscious consumption whereas only 3% of purchases are ethical. Cowe and Williams (2000) call it the “30:3 phenomenon”(Bray et al., 2010). Many researchers undertook studies to find why consumers with positive intentions about ethical consumption often fail to purchase in accordance with these values (Baek et al., 2015;Cherry & Caldwell, 2013; Kim et al., 2016; Yoon et al., 2016; Zollo et al. 2018). Behavior is influenced by far more than attitudes alone, even though it is one of the main influences. Attitudes, experiences, feelings, and social norms

16

have an impact on consumers’ behaviors (Kelkar et al., 2014). This gap prevents companies from truly benefiting from greener strategies (Gabler et al., 2013). This conclusion can explain the reasons for companies to favor greenwashing over actual sustainable changes.

2.3 Greenwashing

2.3.1 Definition

Nowadays, consumers have to be aware that companies shifting to sustainable practices are not automatically sustainable. Before analyzing these practices, it is important to define what sustainability means. According to the Brundtland Report (1987), sustainable development is “a development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. In order to stay ahead in a highly competitive market where consumers demand more choice and ever greater effectiveness, businesses must develop innovative sustainable goods (Bom et al., 2019). Thus, to appear more sustainable, companies have started using greenwashing (Aji & Sutikno, 2015). As explained by Greenpeace, greenwashing is “the act of misleading consumers regarding the environmental practices of a company or the environmental benefits of a product or service”. It involves suggesting a better environmental performance than the actual environmental behavior justify De Jong et al. (2017). This practice goes back to the mid-1980s when consumers were receiving information about products through different communication channels such as television, radio and print news. At this time, access to information was limited and consumers had to trust those environmental claims (Riccolo, 2021). This practice can negatively affect the market causing consumers to be suspicious about green products and lose trust toward the organization's future claims (Kahraman & Kazançoğlu, 2019).

2.3.2 The different forms of greenwashing

Carlson et al. (1993) classified greenwashed advertisements in four different categories of environmental advertising claims. Commercials can use vague terms such as “natural”, it can omit important information, use outright lies or even use a combination of these categories. These environmental claims can be oriented at the product, the process, the image,

17

or the environment. Research correlating the effectiveness of green advertising and green commitment, have found that environmentally committed consumers are more receptive to green advertising than other consumers(Kim & Shin, 2010; Kim et al. 2016).

TerraChoice (2010) classified the different claims into “sins” such as the “sin of hidden trade-off” (when only one or some of the behaviors are really green), the “sin of irrelevance” (when the green behaviors make no significant improvements), the “sin of lesser of two evils” (when the green behaviors merely reflect a comparison with truly bad previous behaviors), and the “sin of fibbing” which refers to lies. Regarding communicative features, TerraChoice mentioned the “sin of no proof” (when claims are unsubstantiated), the “sin of vagueness” (when claims cannot be verified), and the “sin of worshipping false labels” (when fake or questionable certification icons are used), (De Jong et al., 2017).

As shown by several studies, different environmental claims can be used by companies to improve their green image. Here is an empirical list of those claims: green, natural, organic, ecofriendly, sustainable (Kahraman & Kazançoğlu, 2019). We can also notice different levels of product “greeness” with terms such as biodegradable, biodynamic, and ecological. Many ethical questions have been raised regarding cosmetics such as, the protection of the environment, the use of chemical ingredients in production processes, and animal welfare. A rising number of cosmetics brands now use ethical claims in order to attract consumers with a moral and distinctive image of their brand and by promoting common characteristics between the consumers and the brand (Chun, 2014). Although the retailers using green marketing without giving specific explanations of how they minimize their impact on the environment are usually looked upon with skepticism. Jones (2019) examined greenwashing used in advertising and noticed that no matter how responsible a company is, it uses consumer empowerment narratives to influence them. In order to identify when a company uses greenwashing consumers need to know that less responsible companies use emphasizing philanthropy, scientific innovation, and recycling whereas more responsible companies tend to use emphasizing political action, third-party ecolabels, and longevity (Jones, 2019).

18

2.3.3 Lack of regulations

As organic cosmetics are considered a mega trend, companies play with the fact that some words have never been clearly defined and therefore can mean anything causing consumer confusion. As mentioned above, it is the case with the term “natural” which has been overused but has no clear meaning although it influences the consumer to think it is not processed and does not include chemicals (Cervellon et al., 2011). In 2014, Aggarwal and Kadyan stated that the average highest greenwashing sector is the personal care sector. Researchers have also mentioned the lack of regulations to explain the extent of greenwashing in cosmetics. An alarming fact is that out of 80,000 chemicals currently manufactured in products within the U.S., only a few hundred have been tested for safety. Many of these untested, or unstudied, chemicals can be found in cosmetics (Riccolo, 2021).

According to Delmas and Burbano (2011) due to the lack of punitive repercussions, differences in legislation across countries and complexity over effective jurisdiction of cross-country activities is a key driver of greenwashing. As a consequence, marketers widely use this deceiving practice with no fear of breaking present legislation. Therefore, there is little incentive for companies to stop using greenwashing, although when consumers feel deceived, they lose trust both towards the advertised product and the company (Newell et al., 1998). Besides, Lyon and Montgomery (2013) state that companies are less likely to greenwash now as they are facing more risks since social media makes it easier for consumers to verify environmental claims.

2.3.4 Origins and effects of greenwashing

There can be numerous reasons why companies would use greenwashing, Delmas and Burbano (2011) identified four main reasons for it. The first explanation may be the firm’s character, particularly if competitors and consumers expect them to highlight their environmental performance. The second reason is an incentive structure and ethical climate. An incentive structure refers to a system rewarding managers for their performance often leading to unethical behaviors, and the ethical climate of a company is defined by organizational members' common expectations and values that certain ethical reasoning or actions are expected standards for decision making. These expectations and norms differ from companies

19

and are sometimes based on an egoistic ethical climate, leading to greenwashing. The third reason mentioned is organizational inertia in which the company presents itself as green before the requirements are met. The final driver is the lack of effectiveness of the business’s internal communications. That is to say when there is a lack of coordination and communication between the different parts of a company limiting the development of a globalized environmental strategy. Delmas and Burbano (2011) also created a typology of environmental strategies based on two dimensions, the environmental claims and environmental performance of an organization. This classification is composed of four types of companies: silent brown organizations, silent green organizations, greenwashing organizations and vocal green organizations. "Silent brown" organizations have a poor environmental performance and no communication about it, "silent green" organizations do not communicate about their good environmental performance, "greenwashing" organizations combine bad environmental performance with positive communication about their environmental performance and "vocal green" organizations combine good environmental performance with positive communication about their environmental performance (Delmas & Burbano, 2011).

Greenwashing, according to Polonsky et al. (2010), introduces deceiving green claims to the market, lowering the appeal of genuine green goods. As a consequence, consumers could no longer trust all green product and the support from stakeholders, enterprises, customers and society for the green movement would decrease as well as the green consumption market share (Gillespie, 2008; NGuyen et al. 2019).

2.4 Consumer perception

2.4.1 Factors influencing intentions

A major limitation to the development of green consumerism is the lack of information and consumer trust (Cervellon et al., 2011). Kahraman and Kazançoğlu (2019) have identified eight main factors that influenced consumers purchasing intentions for green products: perceived greenwashing, perceived green image, price perception, environmental concern, green trust, skepticism, perceived risk and purchase intention. Perceived greenwashing is influenced by visual and verbal elements for example, Kahraman and Kazançoğlu (2019) demonstrated that “70% of the participants said that using green color as the dominant color in

20

the ads and package color convinces them to feel that products are natural”. Perceived green image is influenced by the origin of the brand, for instance if a company has been producing green products, it appears as more reliable than other companies which started producing green products later. Consumer’s experience with the brand also has an impact on a company’s perceived green image. In addition, prices have a major effect on the purchasing decision as it is often perceived as a quality indicator. Kahraman and Kazançoğlu (2019) found that consumers expect natural products to be expensive because they are made with natural raw materials and made sustainably. Environmental concerns refer to consumers’ attitudes towards environmental protection issues. Green trust is the willingness to rely on the product based on a conviction or assumption about its environmental performance. Skepticism regarding green claims can negatively affect purchasing intentions. To minimize skepticism, consumers research the products natural properties and labels. Consumer perceived risk is defined by Peter and Ryan (1976) as the perception that is connected with the possible consequences of a wrong decision. The notion of perceived risk has been further developed by Aji & Sutikno (2015) into five different risks: financial risk, social risk (traditions, peer group), psychological risk, performance risk and physical risk. Finally, regarding the purchase intention factor, De Jong et al. (2017) confirmed that greenwashing does not affect consumers purchase interests as a real commitment from organizations is necessary to have positive effects on consumers.

An interesting fact about perceived greenwashing is the effect labels have on consumers as a majority of them consider labels as an important criterion when choosing a green product. In fact, one out of two consumers declared they did not trust companies’ environmentally friendly claims and needed an official third-party certification (Cervellon et al., 2011). Somehow, Europeans feel lost between the various labels (national, European, third-party certifications). For instance, the eco-label guarantees a production respectful of the environment, but it does not certify that the product is organic (Cervellon et al., 2011). There is a misconception on labels guarantee for example the Cosmébio label only requires 10% of the ingredients of the final product to be organic. Moreover, this research has found that participants have the same perception of products that were 75% or 99% organic. This is an interesting finding for manufacturers that might want to trade off costs-benefits of these additional 25% or so of organic ingredients (Cervellon et al., 2011).

21

2.4.2 Consumer attitudes

Consumer attitudes have also been analyzed by Lin et al. (2018) based on a tri-component model study which are the affective tri-components, cognitive tri-components, and conative components. The affective components are about emotional feelings. Most participants want to support green cosmetics for emotional reasons because they want to protect the environment and preserve themselves (Lin et al., 2018). However, they found out that consumers were less concerned about green cosmetics compared to traditional cosmetic brands because they focused on product performance rather than green elements (Lin et al., 2018). Cognitive components deal with consumer knowledge of the topic. Respondents with sufficient knowledge of green cosmetics had strong supportive behaviors toward green cosmetics (Lin et al., 2018). However, the major issue for the green cosmetics industry was that consumers lacked sufficient knowledge of the standards of green cosmetics such as the origin of the ingredients, the manufacturing process or the environmental impact (Lin et al., 2018). Lastly, conative components refer to behavioral tendencies.

Lin et al. (2018) found three major factors influencing the formation of attitudes. The first category is knowledge about green cosmetics, the second one is lifestyle and the third one is mass media and family or friends’ recommendations. Regarding the lifestyle category, consumers generally favor comfort and quality rather than caring about minimizing their impact on the environment and society (Bamberg, 2003; Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002; Sharma & Joshi, 2017) as well as personal experience. Finally, as Kim and Chung (2011) have said, a consumer’s previous experience with organic products significantly impact the purchase intention for organic personal care products.

2.4.3 Obstacles to green consumption

Gabler et al. (2013) present in their study two barriers limiting the consumer’s incentives to purchase green products. The first one concerns the lack of green subjective norms, where consumers do not feel social pressure to act green and the second barrier refers to a low perceived behavioral control among individuals that creates a feeling that personal actions are not enough to make a difference and contribute to the larger issue. Other barriers can limit the purchase of green products. For example, consumers’ perceptions of a green product can build

22

barriers as green products are often perceived to be too expensive, they require knowledge and effort to search for information and they can also be difficult to obtain (Tan et al., 2016). When the consumers fail to establish a correct understanding of a product's or service's environmental features during the information-processing process (Turnbull et al., 2000), it is a phenomenon called consumer confusion. Consumers’ lack of knowledge or ability to check the environmental and consumer values of green products leads to misperceptions and skepticism which are common (Ottman et al., 2006; Aji & Sutikno, 2015). These feelings cause the consumer to develop negative perceptions about the product’s environmental aspects (Turnbull et al., 2000).

Three distinctive types of green consumer confusion can be distinguished. First of all, there is unclarity confusion which is defined as a lack of understanding. This type of confusion may be caused by technological complexity or conflicting information for instance. Similarity confusion is the incorrect brand evaluation caused by the perceived physical similarity of products. Finally, overload confusion is caused by too much information regarding the choice of brands. With such a vast quantity of information available, it may be difficult for consumers to focus on the vital points, thus causing confusion (Mitchell et al., 2005). Even if greenwashing has a negative effect on consumers' perception of an organization's integrity, De Jong et al. (2017) found that consumers still have a better opinion of companies using greenwashing than companies which do not consider the environmental aspect at all.

If consumers no longer trust environmental claims and labels used by companies, this could unconsciously lead to disinterest toward green communication and restrict the development of environmentally friendly products (Do Paço & Reis, 2012). It is also important to note that, highly skeptical consumers are not as easily convinced by advertising (Anuar et al., 2013; Aji & Sutikno, 2015).

23

III. Research Methods

The following section focuses on the method the authors selected to conduct their research. The first segment introduces the research paradigm, the research approach as well as the research design. The next segment details the sampling method used to collect data. All the information about data, such as data type, data collection and data analysis is defined in the following segment. Finally, the last part of the methodology refers to the ethical implications.

3.1 Research paradigm

Research is based on a philosophy or a paradigm. According to Saunders et al., (2007), a research philosophy is defined as the development of knowledge and the nature of that knowledge. The research philosophy chosen gives assumptions about the way we view the world and establishes the methodology and research strategy that will be used (Saunders et al., 2007). The most common research philosophies are positivism, rationalism, realism, pragmatism, hermeneutics and interpretivism. This thesis follows the interpretivism paradigm. This paradigm involves an inductive process with a view to providing interpretive understanding of social phenomena within a particular context (Collis & Hussey 2013). The findings are derived from qualitative methods of analysis based on the interpretation of qualitative research data (Collis & Hussey 2013). Interpretivist research philosophy states that the social world can be interpreted in a subjective manner (Žukauskas et al., 2018). It suggests that every person sees the world in different ways and in different contexts. As a result, their attitudes and behaviors are unpredictable (Khan, 2014). This study aims at interpreting and understanding consumer’s purchasing behaviors in a subjective manner through qualitative research.

24

The two most common research approaches are quantitative and qualitative study. Since this study follows an interpretivist research philosophy, a qualitative approach is used. This approach involves collecting qualitative data and analyzing the new data using interpretative methods (Collis & Hussey 2013). It is more clearly defined by Cresswell (2005) as a type of educational research in which the researcher relies on the view of participants, asks broad, general questions, collects data from participants primarily in the form of terms, explains and analyzes these words for themes, and conducts the investigation in a subjective and biased manner. A qualitative study is a meticulous research that aims at answering the questions the study has raised.In a qualitative research, the literature review supports the purpose of the study and helps identify the underlying problems (Soiferman, 2010). In this case, the frame of reference does not usually guide the research questions as it would in quantitative research (Soiferman, 2010). This is done to ensure that the literature does not limit the information the researcher will learn from the interviewees (Creswell et al., 2007). Moreover, the research is based on the consumer's perspective of the phenomenon where the focus is on their intentions and purchasing behaviors rather than from an organization’s point of view.

3.3 Research design

In accordance with the interpretivism paradigm and the qualitative approach, this research follows an inductive grounded theory approach. In the inductive approach, theory follows data whereas in the deductive approach, data follows theory. In fact, an inductive logic aims at understanding the way humans interpret their social world whereas a deductive logic aims at making causal relationships between variables (Saunders et al., 2007). Qualitative analysis is also referred to as inductive thought or induction reasoning because it moves from direct findings about a particular individual to broader generalizations and theories (Soiferman, 2010). This approach is also recommended when there is not enough literature about the phenomenon or if this knowledge is fragmented (Lauri & Kyngäs, 2005). The inductive approach works by making basic observations and measurements, and then goes on to finding themes and trends in the data. Eventually, this data will allow researchers to identify concepts to further explore and the results of the exploration may later lead to theories (Creswell, 2005). The main goal of the inductive approach is to build theories whereas the deductive approach’s aim is to test theories that have been presented in the literature.

25

Grounded theory is defined as the theory that was derived from data, systematically gathered and analyzed through the research process (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). This theory focuses on data collection and analysis. As a method of analysis, grounded theory establishes an interpretation or a hypothesis around the central themes that emerges from the data. This approach focuses mostly on people’s behavior such as consumer’s for instance. A grounded theory strategy is applied to identify a variety of business and management issues (Saunders et al., 2007). Data collection in grounded theory begins without the development of an initial theoretical framework, the theory is then constructed on the basis of data collected by a series of observations (Saunders et al., 2007). This data is used to generate predictions, which are then evaluated in additional experiments to validate or refute the predictions (Saunders et al., 2007).

In addition to an inductive approach, conducting exploratory research is the research design best suited for the study as it aims at developing ideas and patterns about a phenomenon rather than testing a theory already existing. The purpose is to explore a phenomenon that has limited information and research available on the subject area and achieve new insight into this phenomenon for future research. Furthermore, Denscombe (2010) states that qualitative research, exploratory research as well as studies of human interaction and small-scale research are well suited types of research for a grounded theory approach.

3.4 Sampling method

A sample is a subgroup chosen to represent the population studied. As we are doing qualitative research and using the interpretivism paradigm, we will not use a representative sample but rather an exploratory sample. A representative sample enables researchers to generalize their findings to the population (Omona, 2013). Indeed, when doing research under an interpretivism paradigm, the goals is not to make generalizations from the sample’s results therefore choosing the random sampling method is not needed (Collis & Hussey, 2013).

Exploratory samples are used in small-scale research which is typically qualitative research. As stated by Denscombe (2010), an exploratory sample is based primarily on the need to gather new insight and discover new ideas or theories. In an exploratory sample, the explorer studies the topic in depth and tries to gather more details than in a representative sample, which is one

26

of the reasons why exploratory samples are small-scale samples (Collis & Hussey, 2013). The other reason why small-scale samples are used in this type of research, is that an exploratory sample does not focus on having enough participants to allow generalizations but rather on collecting enough information (Omona, 2013). There are numerous non-random sampling methods that can be used in qualitative research such as the snowball sampling, the theoretical sampling, the maximum variation sampling, the homogenous sampling, the purposive sampling, the quota sampling, and the convenience sampling (Omona, 2013).

For the purpose of this study, a heterogeneous sampling (also called maximum variation sampling) was used. In the heterogeneous sampling method, a wide range of individuals, groups, or settings is purposely selected and allows for multiple perspectives of individuals to be presented that exemplify the complexity of the world (Creswell, 2002). In fact, for the purpose of this cross-cultural research, interviewees were selected to represent a various number of countries and continents. Depending on the country, research revealed diverse consumer attitudes and consumers perceptions (Busic et al., 2012; Auger et al. 2008; Srnka, 2004; Vitell, 2003; Vitell et al. 2001). Differences in ethical perception were noticed depending on the consumer’s culture. Moreover, interviewees were selected to represent both genders, female and male. The heterogeneous sampling was combined with a convenience sampling and a snowball sampling to some extent. In fact, convenience sampling was used as the interviewees were also selected for their availability and willingness to participate in the research at the time it was being conducted (Omona, 2013). In addition to the convenience sampling, a snowball sampling was used in the middle of the data collection in order to have people from countries that were not part of the sample yet. Indeed, the snowball sampling (also known as a network sampling) involves asking participants who have already been selected for the study to recruit other participants (Omona, 2013).

3.5 Data type & form

The type of data collected and used in this study to answer the research questions is primary data. It was collected in the form of qualitative data as it is a qualitative research. Hox and Boeije (2005) define primary data as data collected for the specific research problem at hand, using procedures that best fit the research problem. In fact, the data was collected by the

27

authors themselves, they did not use already existing data to answer the research questions. The data collected is qualitative data, which means non-numerical data that describes through text, audio or visual material, the characteristics of a subject. Qualitative data has the capacity to capture temporally evolving phenomena in rich detail (Langley & Abdallah, 2011). Qualitative data can be a printed material such as texts, figures, diagrams, images, but it can also be an audio or visual material such as recordings of interviews, focus groups and videos (Collis & Hussey, 2013). Thus, in this study, primary data was collected through in-depth interviews and later analyzed by the authors to develop a theory.

3.6 Data collection tools and process

Creswell et al. (2007) have identified four techniques of qualitative data collection which can be used by researchers. These techniques are field work, observation, interviews (including group interviews and focus groups), and document analysis. The authors have decided to conduct interviews to build a theory. Scholars have classified interviews in three main categories, unstructured, semi-structured and structured interviews which are usually needed for quantitative research (DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, 2006). For qualitative research data collection especially in a grounded theory approach, the most common interviewing format is semi-structured in-depth interviews (DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, 2006). Moreover, interviews are often the only data source for qualitative research and are usually scheduled in advance at a designated time and location (DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, 2006). These types of interviews either occur individually or in groups, in this particular case, interviews were conducted one person at a time based on a collection of predetermined open-ended questions, with additional questions arising from the interviewer-interviewee conversation (DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, 2006). In fact, interviewers should be prepared to depart from the planned itinerary during the interview because digressions can be very productive as they follow the interviewee’s interest and knowledge (DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, 2006).

The authors conducted cross-cultural research since Gabler et al. (2013) suggested expanding the research to multiple nationalities. The sample includes nineteen individuals from Egypt, Sweden, France, Spain, Senegal, Latvia, Mexico, England, China, Vietnam, Jordan, Gambia, the United Arabic Emirates, and the USA. Qualitative research highlights interpretation and

28

flexibility and this approach is necessary for cross-cultural research because the focus of such research is on meanings and interpretations people give to their behaviors (Liamputtong, 2010). Tillman (2002) defines culture as the ‘individual and collective ways of thinking, believing, and knowing’ of a group. According to Liamputtong (2010), this culture may include the ‘shared experiences, consciousness, skills, values, forms of expression, social institutions, and behaviors’ of the group. When research is taken from a culturally sensitive perspective, the researchers acknowledge ‘the complexity of an ethnic group’s culture, as well as its varied historical and contemporary representations’ (Liamputtong, 2010).

The data was collected through semi-structured in-depth interviews. The interviewees were selected through heterogeneous, convenience and snowballing sampling methods. The purpose was to select people from as many countries as possible in a short period of time. Indeed, the interviews were scheduled by the end of March 2021 and were conducted during the first two weeks of April 2021. Individuals were interviewed through Zoom meetings, phone calls or in person. In the context of Covid 19, social distancing was respected during the interviews.

The interviews were conducted in English for the most part and a few in French as both authors are French, and it was the mother tongue of some of the interviewees. They were asked about their general purchasing habits, their purchasing behaviors and beliefs regarding the cosmetics industry and their perception of greenwashing in this specific market. Open-ended questions were asked to encourage the participants to talk as much as possible and to understand their perception of the different subjects discussed. The interviews were recorded and transcribed into verbatims. The interviews lasted from 20 minutes to 63 minutes.

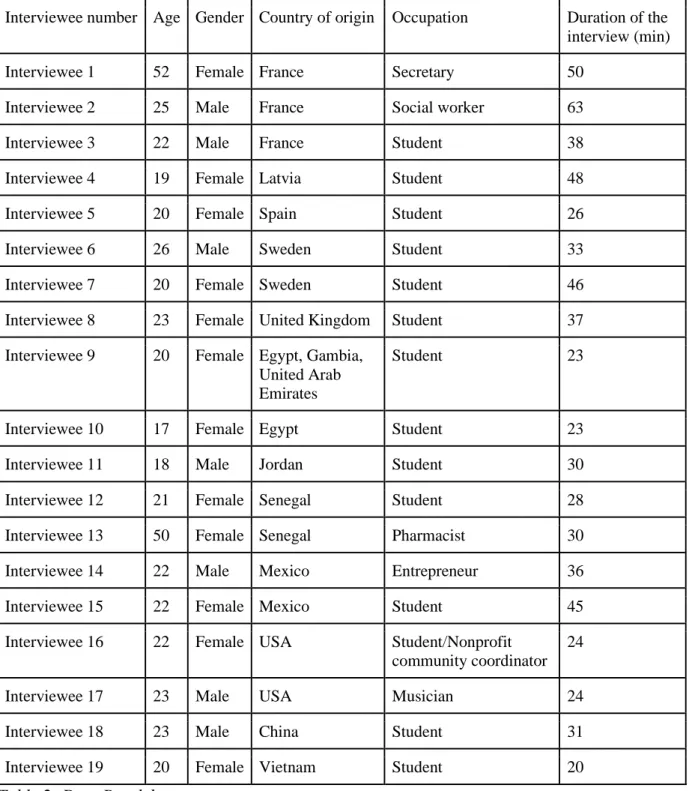

The Table 2 presents general information about the interviewees such as their gender, their age, their activity, and the length of their interview and since the thesis focuses on conducting a cross-cultural study, the table also presents the participants’ country of origin.

29 Interviewee number Age Gender Country of origin Occupation Duration of the

interview (min) Interviewee 1 52 Female France Secretary 50

Interviewee 2 25 Male France Social worker 63 Interviewee 3 22 Male France Student 38 Interviewee 4 19 Female Latvia Student 48 Interviewee 5 20 Female Spain Student 26 Interviewee 6 26 Male Sweden Student 33 Interviewee 7 20 Female Sweden Student 46 Interviewee 8 23 Female United Kingdom Student 37 Interviewee 9 20 Female Egypt, Gambia,

United Arab Emirates

Student 23 Interviewee 10 17 Female Egypt Student 23 Interviewee 11 18 Male Jordan Student 30 Interviewee 12 21 Female Senegal Student 28 Interviewee 13 50 Female Senegal Pharmacist 30 Interviewee 14 22 Male Mexico Entrepreneur 36 Interviewee 15 22 Female Mexico Student 45 Interviewee 16 22 Female USA Student/Nonprofit

community coordinator 24 Interviewee 17 23 Male USA Musician 24 Interviewee 18 23 Male China Student 31 Interviewee 19 20 Female Vietnam Student 20

30

3.7 Data analysis

In order to analyze the data collected during the nineteen interviews, the authors proceeded to their transcriptions and to the coding of these transcriptions. The Gioia method was chosen to code the interviews as it is usually used for a grounded-theory-based interpretive research (Gehman et al., 2018; Nag et al., 2007; Gioia et al., 2013). This coding method is composed of three main steps. The first step is called the “first-order” analysis, it consists of coding the words, phrases, terms, and labels used by the interviewees and identifying concepts that emerge during the different interviews (Nag et al., 2007). During the identification of concepts, it is important to look for similarities and differences among the interviews (Gehman et al., 2018; Nag et al., 2007; Gioia et al., 2013).

Following first-order analysis in which concepts are identified and labeled, authors proceed with the second-order analysis. This step consists in identifying categories which is done by looking for distinct conceptual patterns among the first-order codes (Nag et al., 2007). Finally, second-order categories are being assembled into themes enabling the creation of a theoretical framework (Nag et al., 2007). It forms the basis for building a theory (Gioia et al., 2013).

3.8 Ensuring trustworthiness and consistency

In inductive qualitative studies, trustworthiness and consistency are the two concepts ensuring the quality and credibility of the study. The four criteria ensuring the accuracy of qualitative findings are dependability, credibility, transferability, and confirmability (Guba, 1981).

Dependability refers to the concept of reliability and the stability of findings over time, whether the results would be the same if the same study was replicated with similar participants in a similar context or not (Bitsch, 2005). The different methods to ensure dependability in a study are: using overlap methods, using stepwise replication and leaving audit trail (Guba, 1981). Detailed and comprehensive documentation of the research process and methodological decisions ensure the dependability of research findings. Dependability was implemented in the

31

study by making sure to leave an audit trail. An audit trail offers the possibility for an external auditor to examine how data was collected and analyzed (Guba, 1981). The audit trail for this study is composed of the notes taken prior and after the interviews in addition to the recordings of the interviews.

Credibility, also called internal validity, refers to the equivalence of research results with the objective reality. It is demonstrated by the correspondence of the participants’ perspective with the description of their perspectives by the researcher (Bitsch, 2005). The different methods to ensure credibility are to use prolonged engagement, use persistent observation, use peer debriefing, triangulation, collect referential adequacy materials and to do member checks (Guba, 1981). Credibility was provided in this study by using persistent observation. Persistent observation consists of conducting an in-depth study to gather enough detail and identifying the most relevant characteristics of the situation or problem studied. The persistent observation has been done in the study through in-depth interviews with different consumers.

Transferability, also called external validity, refers to the degree to which the results can be applied to a context apart from where they were gained or regarding other subjects (Bitsch, 2005). The methods outlined for transferability are to collect thick descriptive data and use a theoretical or purposive sampling (Guba, 1981). The authors established transferability during the study by providing thick descriptions, that is to say detailed descriptions of the context in which the data was collected. As explained by Collis & Hussey (2013), when working with qualitative data, the contextualization is very important to provide some background information. Moreover, the authors used a heterogeneous sampling method therefore participants were selected purposely to contribute to the research question.

Confirmability refers to objectivity, it considers the issue of bias and prejudices of the researcher. Individuals and contexts should be the focus of data, interpretation, and findings and not the researchers (Bitsch, 2005). The methods for confirmability are triangulation and reflexivity (Guba, 1981). Confirmability is ensured in the qualitative research through the authors’ research process and more importantly thanks to an audit trail which documents the research process and where data was collected. The audit trail helped the authors practice reflexivity.

32

3.9 Ethical consideration

Ethical considerations were adopted during the collection of data. Prior to the interview meeting, a GDPR consent form (Appendix 1) was sent to the interviewee in order to present the purpose of the interview, explain how data will be collected and used, and to make sure that the interviewee agreed with the process. The GDPR consent form also informed the interviewee of the possibility to remove itself from the research at any point. Once the consent form was signed and collected by the authors, they were able to proceed to the interview. At the beginning of each interview, the interviewees were reminded that they were being recorded and asked if they had any questions concerning the interview process or the research in general.

33

IV. Empirical findings

This section presents the results and themes identified during the coding of the interviews. Using the grounded theory approach in addition to the Gioia coding method, four main themes which align with the two research questions were identified.

The first theme that emerged following the coding of the interviews (e.g., Figure 1) outlines the importance of social influences, the second theme highlights the importance of quality and product performance in the cosmetics industry, the third theme discusses the different barriers when it comes to sustainable consumption and the last theme examines the impact of marketing.

34

4.1 Social influences

Relatives as well as social media have been perceived as the main source of influence when buying personal care products. These influences initiate change in a general direction which is what we call trends. The importance of trends came back as a recurrent pattern when it comes to changing individuals’ habits of consumption as well as their purchasing intentions in the cosmetics industry. Consequently, the social influences theme regroups three categories: social media, relatives, and trends. In addition to social media, the people surrounding us shape our beliefs which has a strong impact on consumers’ purchasing habits. Depending on the source of influence, it can have a positive as well as a negative impact on purchasing behaviors.

4.1.1 Social media

Interviewees mentioned social media such as YouTube, Tik Tok and Instagram as major influences when it comes to purchasing beauty products. In addition to presenting new products and their features, social media play a role in displaying information about companies whether it is about a company’s shift to be more sustainable or its involvement in unethical practices.

Interviewee 8 from the UK: “Social media has a massive effect on a brand’s reputation because for the American brand Glossier, I have seen a lot of things on social media saying that the CEO and the owners were racist and didn’t support people of color. After seeing all of that, I decided not to support this brand anymore. Same thing happened to Victoria Secret, the CEO didn’t support plus size models or transgender models and now everybody doesn’t feel the same way towards Victoria’s Secret as before.”

4.1.2 Relatives

Interviewees tended to believe that their relatives still had more power to convince them to buy a product than social media. They justify it as they trust their relatives to want the best for them and as no money is involved.

35

Interviewee 4 from Latvia: “I don’t really listen to influencers because they are not that truthful, we never know if they are telling the truth.”.

Interviewee 13 from Senegal: “The biggest influence for me when it comes to cosmetics is my family, especially my sister and daughter. I don’t use social media that much, so I usually follow their advice and discover new products thanks to them”.

4.1.3 Trends

In addition to influences from social media and relatives, social trends appear to play an important role in influencing purchasing behaviors. Trends are social influences as they introduce the consumer to new ways of consumption, and they normalize new concepts. Trends turn certain ideas into appealing lifestyles. In fact, movements such as Greta Thunberg raising awareness on global warming had an impact on people’s mindset whether it is positive or negative.

On the one hand, interviewee 16 from the USA stated that: “Greta Thunberg is a huge influence, once I started watching her videos a few years ago and hearing what she had to say I thought she was a really awesome positive influence”.

On the other hand, interviewee 6 from Sweden did not perceive the impact of this movement as very positive: “Constantly hearing about it in a negative way makes people tired of listening and annoyed”. A few years ago it was fresh and new but now they need to reinvent that trend in a more positive way”.

Interviewee 14 from Mexico discussed how cultural trends impact consumer consciousness: “In Latin America, trends are always late and always come after the USA and Europe. It is one of the reasons why only few people have adopted conscious consumerism in Mexico, it is not a big trend yet”.

36

Interviewee 11 from Jordan confirmed the critical role of trends in the Middle East, also mentioned by the interviewee 9 who used to live in the United Arab Emirates: “In the Middle East people seem to be more likely to buy what is trendy and famous”.

4.2 Quality and product performance

Following the interviews, the quality of a product was one of the most significant influence on purchasing intentions. This research also highlighted consumers’ health concerns.

4.2.1 Product Performance

Quality was mentioned as one of the main criteria when it comes to purchasing cosmetics. A good quality product meant for the interviewees a product that delivered a satisfying performance, and this factor was usually perceived as a more important concern than sustainability.

Interviewee 12 from Senegal: “I am suspicious of green products’ performance [...] and I think it’s the reason why a lot of people are not willing to buy green cosmetics”.

Interviewee 6 from Sweden: “I go for greener products, but they expire quicker than regular alternatives”.

On the other hand, green products were reassuring as some participants assumed it had less chemicals in them.

Interviewee 17 from the USA: “If it can say organically made or plant-based on the bottle, I definitely have more of an influence to buy that because I know then it’s a little more natural, I definitely don’t want harsh chemicals on me”.

37

4.2.2 Health

Health is a critical criterion when choosing cosmetics. Cosmetics are products in direct contact with skin or hair, therefore, finding products with less chemicals and more natural ingredients was considered highly important for consumers. Interviewees thought that a high-quality product is one that does not contain any potentially dangerous ingredients.

Interviewee 19 from Vietnam: “With cosmetics it is different because it is directly used on my skin, luckily I am not a person with allergies but I am careful with the ingredients”.

Interviewee 6 from Sweden: “I am worried about chemicals and long-term effects they can have on your health”.

4.3 Barriers to green consumption

Three main barriers were identified as obstacles towards a greener consumption: the financial barrier, education and convenience.

4.3.1 Financial barrier

Price turned out to be the second most important criteria to purchase cosmetics after quality. It is also perceived as the biggest barrier when it comes to conscious consumption, as eco-friendly alternatives were considered expensive.

Interviewee 14 from Mexico: “Being sustainable is a privilege, everyone can’t be sustainable because of the price. The normal wage of people in Mexico is very low. When you don’t have money problems, you find other problems like the problem of sustainability; but when you have your problems of your own you don’t think of the problem of the planet”.