The leadership role in Lean

implementation in the

different management tiers

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Major NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 credits

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Global Management AUTHOR: Christian Ricardo Burneo Del Salto

Master Thesis Global Management

Title: The leadership role in Lean implementation in the different management tiers Authors: Christian Ricardo Burneo Del Salto

Tutor: Jean-Charles Languilaire Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Leadership, Lean Management, Management tiers, Managerial skills.

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to identify a customized leadership style that catalyses a successful lean management adoption process within each management tier. For establishing the

aforementioned tailored style, individual behaviors from leadership styles recommended by literature to be optimal for lean adoption where studied. The behaviour individualization offered a wider set of combinations to develop a custom leadership style. Lean managers, categorized in the management tier they perform, ranked the behaviours they found to be essential with the highest score, and behaviours that are not effective in lean management ranked in the lowest positions. Further on, these results were contrasted with lean consultant’s perspectives on the matter, as they bring an external point of view to compliment and understand the context of management and lean. Literature findings where used to develop data gathering tools, as well as a comparing point between practical findings and theoretical propositions. Moreover, findings on leadership behaviors are linked to Katz’s skill managerial model. Critical Dynamic Leadership (CDL) is the leadership style suggested for lean implementation. Addressing each management tier, CDL for work-floor, CDL for middle-level and CDL for top-level management, CDL presents a set of tailored leadership styles developed for each management tier. CDL answers the behaviours leaders need to develop to foster lean, while leaving an open window for critical dynamism. Critical dynamism refers to the ability to understand the space and time context and the power of adaptability to such circumstances, having first analysed the situation critically. In a practical perspective, organizations can address these findings to have a holistic understanding on what lean represents, how it acts and what factors to take into account when facing its

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1. Background ... 1 1.2. Problem Discussion ... 5 1.3. Problem Formulation ... 6 1.4. Purpose ... 7 1.5. Research Questions ... 71.5.1. RQ I - What leadership behaviors are linked to a successful Lean Management implementation? ... 7

1.5.2. RQ II – How are the leaders in different management levels involved in the implementation of Lean Management? ... 8

1.6. Delimitations ... 8

2.

Literature Review ... 10

2.1. Lean Management & Lean Leadership ... 10

2.1.1. Lean Management ... 10

2.1.1.1. Toyota’s Leaders ... 12

2.1.2. Lean Leadership ... 14

2.2. Leadership ... 18

2.2.1. Optimal leadership styles for lean adoption ... 19

2.2.2. Leadership behaviors to catalyse a successful lean adoption ... 21

2.3. Management Tiers ... 23

2.3.1. Involvement of the management tiers ... 23

2.3.2. The Domino Effect/ Cascading Effect ... 24

2.3.3. Katz’s managerial skills & tiers model ... 25

3.

Methodology ... 29

3.1. Research Philosophy ... 29

3.2. Research Approach ... 30

3.3. Literature research ... 34

3.4. Empirical Data Collection ... 34

3.4.1. Multiple-Choice Questionnaire ... 35

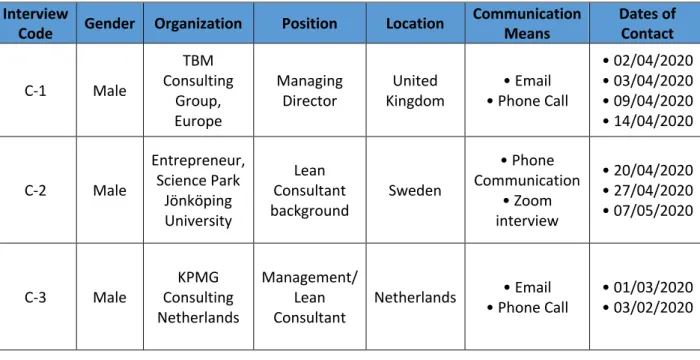

3.4.2. Semi-structured Interviews ... 38

3.5.1. Validity ... 39

3.5.2 Limitations ... 40

4.

Empirical findings ... 42

4.1. Work floor-level Management ... 42

4.2. Middle-level Management ... 44

4.3. Top-level management ... 47

5.

Analysis ... 50

5.1. Research-Question 1: Analysis and results ... 50

5.2. Research-Question 2: Analysis and results ... 56

5.2.1. Work-floor level management’s leadership behaviors ... 56

5.2.2. Middle level management’s leadership behaviors ... 59

5.2.3. Top-level management’s leadership behaviors ... 61

5.2.4. Leadership behaviors in each management tier ... 64

5.3. Critical Dynamic Leadership tailored for each management tier. ... 65

6.

Discussions & Theoretical Contribution ... 67

6.1. Conclusion ... 67

6.2. Theoretical Contribution ... 67

6.3. Practical Contributions ... 68

6.4. Future Research ... 68

Figures

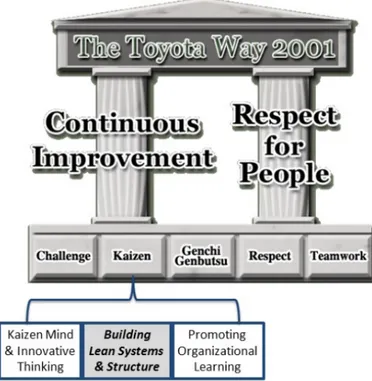

Figure 1 The House of Lean/ The Toyota Way 2001 ……….……….. 11

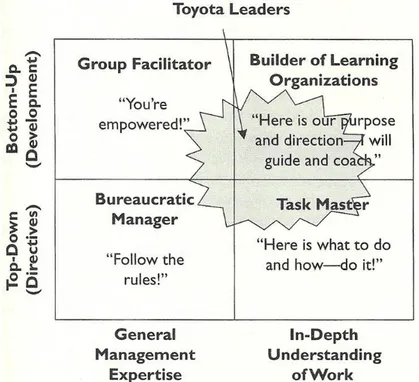

Figure 2 The Toyota Leadership Matrix ……….……….. 13

Figure 3 Core values of lean management ………….………... 15

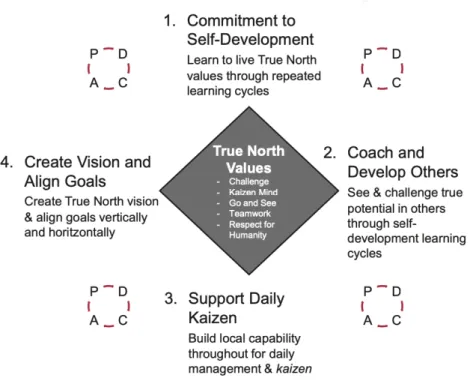

Figure 4 The Diamond Model for Lean Leaders ……….. 17

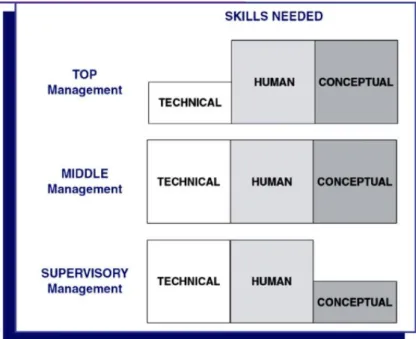

Figure 5 Katz's three managerial skills model ……….……….. 27

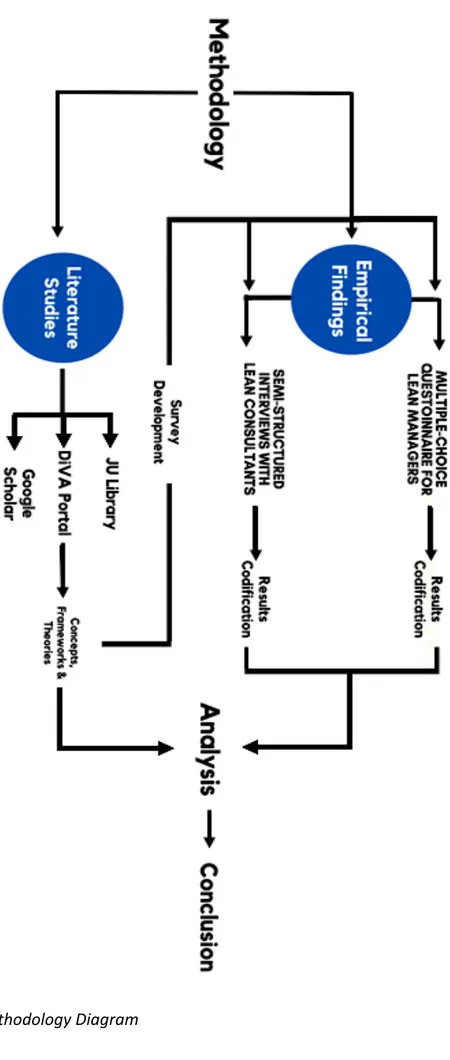

Figure 6 Methodology Diagram ………... 33

Figure 7 Work floor management leadership behaviors in lean adoption ……....…...43

Figure 8 Middle-level management leadership behaviors in lean management adoption………...45

Figure 9 Top level management level leadership behaviors results…..………47

Figure 10 Optimal leadership behaviors in lean adoption ………...…..………....51

Figure 11 All management tiers leadership behavior comparison ….………....65

Tables

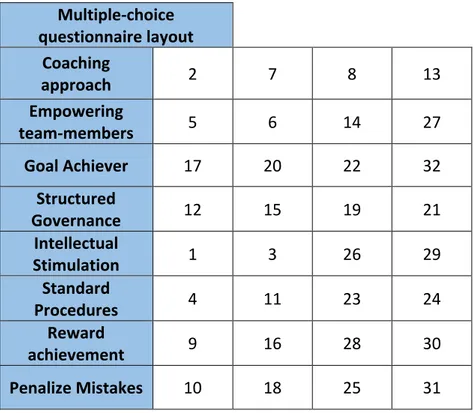

Table 1 Leadership behaviors that catalyze a successful lean adoption process ... 22Table 2 Survey Layout………. 36

Table 3 Scoring System ... ………36

Table 4 Multiple-Choice Questionnaire for Lean Managers………. 37

Table 5 Interviewed consultants’ information……….. 39

Table 6 Work floor leadership behaviors results……….. 43

Table 7 Medium management level leadership behaviors results………..45

Table 8 Top-level management leadership behaviors results………47

Table 9 Optimal leadership behaviors in lean management adoption results …..…… 50

Table 10 All management tiers leadership behavior comparison ………..56

Table 11 CDL custom Leadership Style to catalyze a successful lean adoption………...……….………..66

Appendix

Appendix 1 Inerview for lean consultants ... 771. Introduction

______________________________________________________________________

This chapter presents an introduction to the lean management concept and the underlying factors that are related to the success or failing of Lean Management implementation. Furthermore, the problem discussion will be developed followed by the problem formulation, the purpose of the study and the research questions. This chapter will end with the explanation of the delimitations of the study to define the scope of this research.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1. Background

Globalization and technology innovation have pushed markets to a new era of challenges; an era of fading market borders where consumers have more decision power over the products and services they consume than ever before. The increased interrelatedness of regions, society and business environments enhanced the local, regional and global competition level for organizations (Achanga, shehab, Roy and Nelder, 2005; Garza-Reyes, Betsis, Kumar & Radwan Al-Shboul, 2016; Loh, Yusof & Lau, 2019). While the pressure from the demand side to deliver personalized products and services became stronger, industries were pushed to enhance their market strategy and boost the quality of their products and services, while reducing costs and cycle times (Garza-Reyes, Betsis, Kumar & Radwan Al-Shboul, 2016; Loh, Yusof & Lau, 2019). Such circumstances placed both technological and social organizations on a crossroad on whether to adapt to the new circumstances or perish on them (Achanga, shehab, Roy & Nelder). Many responded to this dilemma by taking the decision to enter the lean journey (Loh et al., 2019).

Lean management can trace back its origins to the manufacturing sector, when a need for process improvement and waste control emerged. Nevertheless, over the years it has earned recognition in other sectors, now being possible to find lean management or lean practices in any industry, from manufacturing to services or governmental institutions (Dekier, 2012; Jadhav et al., 2013; Gaiardelli et al., 2019). The core concept for a company to go lean, regardless of the industry, is the constant thriving to find and apply improvements for excellence through the removal of waste by eliminating inefficient processes and enhancing and maximizing the value chain activities (Dekier, 2012; Jadhav et al., 2013). The latter, in a traditional lean setup, is done through the utilization and applying of practices and lean tools such as, Just In Time (JIT), Total Quality Management (TQM), Continuous Improvement,

Resource Planning and Supply Chain Management (SCM) (Jadhav et al., 2013). All stated practices and concepts are contributing to the maximization of customer value (Jadhav et al., 2013). The dual focal point on enlarging business value through process innovations and the reduction of waste, positioned lean management to be considered as one of the greatest management inventions for business improvement of the twentieth century (Jadhav et al., 2013; Bocquet, Dubouloz & Chakor, 2019). Hence, many organizations have adopted the lean principles in their organizational culture (Jadhav, Mantha, Rane, 2013; Nogueira, Sousa & Moreira, 2018).

Over the years, studies have been widely performed on the low success rate of lean implementation (Loh et al., 2019). These studies showed that despite of the increase in adoption of lean, less than 10 percent of companies achieved the desired level of success on its implementation (Jadhav et al., 2013). Also, more recent studies mention that only a small percentage (2-3%) of the companies manage to achieve the desired level of success (Loh et al., 2019; Salhieh & Abdallah, 2019). Other studies explain different values, such as the census elaborated by Industry Week in 2008, where the results found state that 75 per cent of companies starting the lean journey do not reach any improvements, and less than 2 per cent achieve the amount of anticipated results (Van Landeghem, H., 2014). Moreover, practice shows that organizations attain significant success in the first years after lean adoption, but it eventually ceases to show tangible results in the long term due to stagnation (Trekner, 2016; Salhieh & Abdallah, 2019). Sisson & Elshennawy (2015) state that 70 per cent of the organizations that took the step to lean implementation, return to their original business practices. Literature exhibits that the failure of organizations implementing lean is due to multiple factors: culture/structures, the human factor and leadership (CSHL factors) (Jadhav et al., 2013; Alefari, Salonitis & Xu, 2017; Loh et al., 2019).

Cultural and hierarchical company structures are considered as two of the main key factors for the implementation of lean. Change in structure, systems, processes and culture are required when implementing lean (Aij et al., 2015; Aij & Teunissen, 2017; AlManei, Salonits, Tsinopoulos, 2018). The introduction and guiding of such changes are challenging. Often, the development of core values coming along with the change is neglected, causing failure of lean implementation (Loh et al., 2019; Salhieh & Abdallah, 2019). Several scholars stated that core lean values are the basis of a lean thinking culture in an organization whereas lean tools or lean management frameworks (5S, visual management) put these values in action

(Salhieh & Abdallah, 2019). When such lean values and/or culture are not present, the aforementioned tools or practices cannot be applied (Salhieh & Abdallah, 2019). When leaders do not understand the need for the systematic change, lean initiatives tend to fail (Aij & Teunissen, 2017). Cultural infrastructure has proven to be a critical factor when an organization is implementing lean (Pakdil & Leonard, 2015). The identification and understanding of this infrastructure are considered as important for the adaptation of lean principles as the other lean practices. The underlying lean processes can cause conflicts with the already existing organizational culture, that can lead to a failure of lean implementation (Pakdil & Leonard, 2015).

Another essential factor in an unsuccessful lean management implementation process is the lack of awareness of the importance of the human factor. When it comes to the human factor, many frameworks neglect it or only worth it partially. Nonetheless, a strong human factor is considered as one of the main factors for a successful implementation of lean (Gaiardelli, Resta & Dotti, 2019; AlManei et al., 2018). Mann (cited in Jadhav et al., 2013; Gaiardelli et al., 2019) highlighted the importance of the human factor for the adoption of Lean Management, stating:

“Focus on the people and the results will follow. Focus on the results, and you’ll have the same troubles as everyone else: poor follow-up, lack of interest, no ownership of improvements, diminishing productivity”.

The involvement of the human factor and their motivation are key for a successful implementation of the lean approach. However, the lack of understanding, enthusiasm and commitment of the workforce, including the different management levels, are the main barriers for a successful lean implementation (Alefari et al., 2017; Gaiardelli et al., 2019).

The last factor for a successful implementation of lean is leadership. Multiple studies point out the importance of leadership, as being the catalyst that will ensure consistency between the lean operations practices, tools and principles (Camuffo and Gerli, 2012). Mann (2009) strengthens this by stating:

“There is a missing link in lean. This missing link is the set of behaviors and structures that make up a lean management system. Lean management bridges a critical divide: the gap between Lean tools and Lean thinking”.

Leadership is also seen as the cornerstone for a successful lean implementation (Mann, 2009; Camuffo & Gerli, 2012; Dombrowski & Mielke, 2014; Aij et al., 2015; Alefari et al., 2017; Aij & Teunissen, 2017; Patri & Suresh, 2018; AlManei et al., 2018; Tortorella, de Castro Fettermann, Frank & Marodin, 2018; Loh et al., 2019). The latter can be explained by the several studies emphasizing that leadership is the basis for the development and implementing of cultural structures to create an environment that possess the conditions in which lean can blossom (Mann, 2009; Tortorella et al., 2018). Furthermore, leaders also have the crucial role to engage with all employees, instruct and motivate them (Tortella & Fogliatto, 2018; Tortorella et al., 2018). When leaders are not able to grasp the need to understand and implement the required changes and convey them to the workers, lean implementations often fail (Aij & Teunissen, 2017).

The culture/structure elements and the human factor (employees’ and managers’ motivation) are dependent on strong leadership (Mann, 2009; Dombrowski & Mielke, 2014; Tortorella et al., 2018). As literature states, leadership is the missing link that will ensure the successful implementation of lean management, this research will focus on the leadership element in lean management. Literature has classified transformational, transactional and empowering leadership to be the catalyzers for successful lean management implementation (Poksinska et al., 2013; Tortorella & Fogliatto, 2017; Alefari, et al., 2017; Tortorella et al., 2018; Noqueira et al., 2018; Burawat, 2019). This research will look at the distinct behaviors belonging to these leadership styles and what leadership behaviors lean managers involved in their personal experience with lean management adoption and function. As leadership styles do not automatically cascade from one level of management to another, and one leadership approach does not necessarily work or satisfying other levels of management, behaviors from managers at the three different management levels will be analyzed (Lowe, Gale & Sivasubramaniam, 1996; Nealey & Blood, 1968; Coad, 2002). This with the purpose of determining what behaviors form the most optimal leadership style that can catalyze a successful Lean Management adoption throughout different management levels.

1.2. Problem Discussion

As it is shown in the literature, leadership is the basis to successful lean adoption (Mann, 2009; Camuffo & Gerli, 2012; Dombrowski & Mielke, 2014; Aij et al., 2015; Alefari et al., 2017; Aij & Teunissen, 2017; Patri & Suresh, 2018; AlManei et al., 2018; Tortorella, de Castro Fettermann, Frank & Marodin, 2018; Loh et al., 2019). When the lean philosophy is implemented successfully, an organization's overall performance will improve. It will lead to the enlarging of business value, cost reduction, improving quality, reduction of waste and it can push a business towards great growth (Jadhav et al., 2013; Sisson & Elhennaway, 2015).

Over the years, the perspective of hierarchical structures in organizations changed. Previously, decisions were mainly made from the top-level down and the middle and lower levels merely followed decisions (Oshagbemi, & Gill, 2004). Nowadays, organizations have tended to adopt a more horizontal hierarchy model where decision-making and several responsibilities are assigned to middle and supervisory management levels (Grover, Jeong, Kettinger & Lee; Oshagbemi, & Gill, 2004; Yukl 2013). Research shows that for a company-wide, successful implementation of lean, all three levels of an organization should be involved (Mann, 2009). Despite the important role of leadership for the implementation of lean, the leader is not the player adding the value to the processes. Dombrowski and Mielke (2013) describe an analogy where the work-floor employees act as the players on the field in charge to score and are coached by the leader/manager. The leader is described as the strategy creator, team builder and skill developer. The latter metaphor illustrates the importance of the involvement of all three levels of management in the implementation of lean (Mann, 2009). Nevertheless, Mann also mentions that the lower levels of the organizations are often poorly involved, leading to insufficient lean design at the lower levels causing lean implementation to fail. Finally, he points out the key role of managers at different levels in a successful lean implementation and that effective leadership in lean comes from both sides of the hierarchical ladder; from the top, as well as from the lower levels (Mann, 2009).

When investigating deeper into the extensive body of literature on Lean Management and Leadership, it is observable that researchers tend to leave out the different tiers of management for the lean adoption process. (Nogueira et al., 2018; Loh et al., 2019; Gaiardelli et al., 2019; Seidel, Saurin, Tortorella & Marodin, 2019). This fact contradicts the aforementioned Mann’s statements, addressing the importance of leadership at the different

management layers when dealing with lean management adoption (Mann, 2009), creating a gap of knowledge on the information that is set to be considered of fundamental importance on the cultural adoption of lean.

Several studies on the connection between lean and leadership have attempted to explain the intertwined relationship between lean leaders and lean employees (Tortorella et al., 2018). As lean implementation carries abrupt changes, the role of the lean leader is crucial. However, these changes also demand managers to adapt their leadership behaviors to current situations (Aij et al., 2014).

For the concept of lean leadership, there are no specific set of leadership behaviors, template or framework describing the topic. Hence, lean leadership is a concept that has not been widely accepted by the research community (Mann, 2009; Aij et al., 2014). By now, many authors have identified the need for a leadership fit to lean adoption, but only few holistic concepts exist (Dombrowski, 2014). Especially lower and middle management are management tiers with the least clear approaching techniques or rules for lean implementation (Dombrowski, 2014).

However, findings on the available literature on leadership behaviors and lean management result contrasting. Where few authors mention transformational leadership to be the catalyzer for successful lean implementation (Poksinska, Swartling & Drotz, 2013; Tortorella & Fogliatto, 2017; Alefari et al., 2017; Tortorella et al., 2018; Burawat, 2019), Nogueira et al. (2018) state empowering leadership to be the key for the implementation process (Nogueira et al., 2018), while Alefari et al. (2017) state transactional leadership as the essential driver for the implementation of Lean Management.

1.3. Problem Formulation

In the above documented discussion, the following issues in relation to lean management and leadership are coming forward. Initially, the literature shows contradicting statements on the best leadership styles to use for a successful Lean Management implementation, and no framework or template with a general acceptance or consensus has been agreed. Following this, the lack of research on the different management tiers related to leadership in lean management is observed. As a consequence, considering that multiple authors are pointing out the failing of lean management implementation and lack of longitudinal organizational

results (Dombrowski & Mielke, 2014; Holmemo & Ingvaldsen, 2015; Erthal & Marques, 2018; AlManei et al., 2018; Salhieh & Abdallah, 2019; Loh et al., 2019), raises the question if organizations that are implementing lean management would benefit from a tailored leadership style for each management level. The identified gap in the literature will be addressed in this study. Combining the contradicting views on leadership styles for lean management adoption and the lack of research on how leadership catalyzes lean adoption in different management tiers, the research problem was composed as:

“What leadership styles catalyze a successful lean adoption within each management tier?” 1.4. Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to determine what leadership style works best at each management level to catalyze a successful Lean Management adoption.

1.5. Research Questions

The aforementioned problem formulation and purpose leads to the following research questions:

1.5.1. RQ I - What leadership behaviors are linked to a successful Lean Management implementation?

To be able to determine what is the best leadership style is to catalyze a successful Lean Management adoption, it is important to understand the grouped leadership behaviors that are forming the predetermined leadership styles. In order to get a comprehensive view of what these leadership behaviors are, different literature is used in the form of academic research papers, conference papers and books. Another approach for understanding the leadership behaviors that foster lean adoption will be the use of a multi-option questionnaire, based on the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ). With this questionnaire, data will be gathered on what leadership behaviors are considered to be essential for lean managers from different management tiers (upper, middle, work-floor level), to adopt lean philosophy. Behaviors exhibiting the highest scores on each management level will be compared to each other to understand overall differences on leadership approaches for each management tier. In addition to this questionnaire, interviews with lean consultants will be conducted, in order to contrast the perspective of managers experiencing lean adoption firsthand, with those

perspectives of external agents to the organization that guide the company to achieve successful lean management engagement.

1.5.2. RQ II – How are the leaders in different management levels involved in the

implementation of Lean Management?

Different tiers within a company have different idiosyncrasies leading to diverse manners of handling and understanding processes. As the aim of this research is to determine what leadership style is the most optimal for lean management adoption within each management tier, it is important to understand how each level is involved when performing under lean culture. To research this component, similar steps are taken as in RQ-1. The main source of data is the use of different literature theoretical propositions, such as academic research papers, conference papers and books to create an overview of what is already known about the different management tiers in relation to Lean Management. This is complemented by the distribution of the multi-option questionnaire, destined for managers with lean experience. The questionnaire will provide data on what leadership behaviors are common at each management tier. Additionally, what lean leaders perceive to be the most optimal leadership behaviors to foster a successful lean cultural engagement. Results gathered with lean consultants will also be useful to reach conclusions for RQ-2.

1.6. Delimitations

This research has four delimitations that were predetermined to understand the reaches and confines of this analysis.

Starting with the demarcation of the lean concept focused on in this research. “Lean” is nowadays a widely used term (lean service, lean entrepreneurship, lean product development, lean Manufacturing, lean Management) and has many elements and tools (5-S, establishing a pull flow etc.) to reach the underlying goal of lean, “the maximizing of customer value through the

minimizing of waste elements”. Therefore, the first delimitation is that this study will focus on

lean management, where the focal point of attention is on all tasks and requirements that are necessary to effectively manage activities under lean principles within a business. This study will not go into depth on the different tools and elements that are distinctive for Lean Management performance, as an analysis on the lean operational process is not the aim of the research.

The survey to rank leadership behaviors that catalyze a successful lean adoption process are destined for lean managers or managers with experience in organizations performing with lean culture. The latter means that employees’ perspectives are not considered in this research.

The third delimitation is that this research only focuses on the implementation phase of lean management and focuses on the behaviors of managers that contribute to succeed in the implementation of Lean Management. The reason for this is that the implementation phase has to be solid since it is the first step that a company will take towards becoming lean. Hence, this research will not consider other phases of maturity on lean culture within an organization and will focus on how to create prosperous conditions to adopt lean management through a leadership perspective.

A last delimitation is the focus on leadership behaviors of managers rather than styles for the analysis. It is important to highlight this perspective, as the purpose of the research is finding the best leadership style. Nevertheless, in order to determine an optimal leadership style, it is necessary to understand what behaviors managers consider that compose the most optimal leadership style for lean adoption. As a consequence, the research will be analyzing the behaviors of managers on the three different management levels. After analyzing the gathered data, the information will be categorized into distinct leadership styles or style that will ensure a successful Lean Management implementation.

2. Literature Review

______________________________________________________________________

The purpose of this chapter is to provide the theoretical background on the topic of lean management, leadership and managerial skills & tiers. The description for each of the concepts is provided to gain a contextual understanding on the factors involved to answer what leadership style is optimal for lean adoption.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1. Lean Management & Lean Leadership

Lean management and lean leadership are two closely intertwined concepts, that share a variety of similarities, but do not describe the same topic. Such differentiation will be explained in the following sub-chapters. Additionally, this will provide further clarification on the purpose of searching for an optimal leadership style to foster lean adoption, taking into account that lean leadership is not a widely accepted concept in the research community. An explanation on the limitations and underlying reasons why the concept lean leadership is refuted for this research are given.

2.1.1. Lean Management

The lean movement can find its roots in the Toyota Production System (TPS). It was originated in the beginning of the twentieth century, in Japan (Dekier, 2012; Liker & Ross, 2017). Over the years, lean has evolved and turned into an attractive idea for companies looking for methods to add value to its processes. Hence, it is now possible to find this concept widely acknowledged (Alefari, Salonitis & Xu, 2017). The Toyota Production System and Lean Manufacturing were predecessors of the concept of lean management, having later evolved to a more holistic philosophy, including human factors rather than only manufacturing processes (Dekier, 2012). The difference between lean manufacturing and lean

management is the focus and objectives each of these concepts carry. The first concept is

focused on the production process improvement, whereas lean management deposits another focal point on the management of human development in the organization. Dekier (2012), defines lean management as a method for managing companies that assumes adaptation to the actual market conditions via organizational and functional alterations, with its main task targeting the development and adjust of the companies’ policies and management styles.

After realizing the success of their organizational culture model, Toyota decided to expand their business model outside of home soil. And so, after having been tested and succeeded in the North American market, Fujio Cho, Toyota Motor Company President in 1999, decided to set a written document stating the principles of Lean Management. He struggled to get consensus within Toyota about a lean concept, mainly receiving the argument that the company was a complex living organism, impossible to be set in documents. And so, the only way he could get a general approval was by calling it The Toyota Way 2001, clearly stating that such concepts were optimal under the 2001 conditions. It has not been updated until this day (Liker, J. & Ross, K., 2017).

These principals were described as a house founded on two pillars (Fig 1). These pillars represent Continuous Improvement & Respect for people. Continuous improvement represents the technical principal of lean; constantly challenging processes searching for more effective ways to produce them. The second pillar describes a more complex, intricate factor; the respect for people.

Figure 1: The House of Lean/ The Toyota Way 2001. Source: Adapted from Liker, J. & Ross, K. (2017)

The Toyota Way 2001 explains that the respect for people not only considers a nice treatment between the parts. It goes beyond it, to explaining that respect for people also encompasses keeping members challenged, in pursuit of constant evolution and self-development. It explains the respect company members should have for customers and its need, to all the human agents participating in the context of the company. This concept is maintained intentionally generic, in order to include all of these related, undirect human factors. (Liker, J. & Ross, K., 2017).

The house foundations are formed by the core values of The Toyota Way, tools needed to achieve continuous improvement and respect for people. These cores, also known as The

True North Principles, are: Challenge, Kaizen, Genchi Genbutsu, Respect, Teamwork. This

core foundations start as a chain process, where a team member would face first the Challenge of developing themselves in this topic. Following next, Kaizen describes of constant improvement (Dekier, 2012; Jadhav et al., 2014; Liker & Ross, 2017). Genchi Genbutsu represents the rule how kaizen should be practiced, stating that members should learn processes through observation and trial and error. The last two values, Respect and Teamwork, focus on people and the underlying concept is that respect between parts is imperative to achieve results.

2.1.1.1. Toyota’s Leaders

As the research states on previous chapters, Lean management was developed in Toyota’s headquarters in search for business and culture development. Hence, it is of great importance to understand the roles and responsibilities leaders ought to possess according to the developers of the model.

The Toyota company has its own view towards leadership, which is built on the Toyota’s principle: “Grow leaders who thoroughly understand the work, live the philosophy, and teach it to others” (Liker, 2004). Jeffrey Liker (2004) illustrates a two-dimensional leadership matrix (Fig. 2) where it is set out what makes leadership at Toyota different compared to conventional leadership.

Figure 2: The Toyota Leadership Matrix. Source 1: Adopted from Liker (2004)

The matrix explains how leaders can rule both from top- down (decisions implemented by directives) or bottoms-up (initiative where people are empowered to develop solutions and make the right decisions on their own). Even though motivated, proactive people are a key factor for a lean culture, the Toyota leadership model has one step further on this approach, the technical understanding of the company’s processes. An in-depth understanding of the work in addition to general management expertise complete the characteristics of a Toyota leader (Liker, J., 2004).

Each quadrant explains different categories of managers, concluding with Toyota’s particular leadership approach on the top-right corner. The leader on the bottom-left quadrant, the

bureaucratic manager, describes the leader that promotes the idea of being able to rule any

business only by looking at figures and following standardized procedures. This concept of what a leader is, represents the antithesis of what Toyota understands for leadership, avoiding addressing all the human development factors that leaders should carry while performing under a lean organizational culture. (Liker, J., 2004).

The leader depicted on the top-left quadrant is the group facilitator. This leader is set to have excellent motivational skills that can stimulate the team to pursue goals and objectives. Nonetheless, his lack of technical knowledge can limit their tasks. Group facilitators are catalysts for team development but cannot go into further capacitation due to his technical knowledge limitations.

Continuing on the matrix, in the bottom-right corner, the task master leader is depicted. This leader is described as a person who possesses technical skills (the know-how), but is lacking soft skills, creating barriers in the working processes. These managers are often seen as manipulators and have trust issues with less experienced workers. In similarity with the bureaucratic manager, task master managers base their work on giving orders, although, in contrast with the bureaucratic managers, the task master’s orders are specific and detailed.

Finally, the Toyota leaders are depicted in the top-left quadrant. These leaders are characterized by the combination and balance of in-depth understanding of the work and the ability to guide and mentor new team members. Toyota’s leaders rarely give orders but help employee’s self-improvement by challenging them with questions (Liker, J., 2004).

Consequently, the concept of leadership proposed by Toyota when developing the lean management concept, proves that a lean manager/leader ought to possess a wider set of skills than managers performing under more traditional organizational cultures. This updated concept of leadership depicts one of the fundamental differences and aggregated values lean management brings to the organization.

2.1.2. Lean Leadership

Dombrowski and Mielke (2013) attempted to define the relationship between leadership and lean into one general concept, designating it as Lean Leadership. They define the concept as follows:

“Lean leadership is a methodical system for the sustainable implementation and continuous improvement of Lean Production Systems. It is an explanation of the collaboration between employees and leaders, who are equally trying to search for perfection” (Dombrowski & Mielke 2013;

Dombrowski and Mielke (2013) related the aforementioned True North principles of lean and various approaches of different authors into a comprehensive framework that sets the core values of their concept of Lean Management, (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Core values of lean management. Source: Adopted from Dombrowski & Mielke (2013)

Improvement culture is stated to be all behaviors leaders show combined, that are constantly

seeking for excellence and perfection, where zero waste, zero inventories, and zero defects is the goal. The objective of this principle is the constant drive to improve processes by trying to find the root cause of the failures in the processes, not in people. Here, Dombrowski and Mielke (2013) emphasize on the aspects that leaders ought to understand failures differently and in-depth; the long-term thinking of leaders being an important aspect to ensure a lean implementation to become successful (Dombrowski & Mielke, 2013).

Self-development describes a cornerstone aspect for leaders. When undergoing a cultural change

to become lean, leaders need to develop new leadership skills, skills that they do not necessarily portrait their own personality. Through the use of the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle leaders constantly go through short learning cycles to develop themselves to develop into lean leaders (Dombrowski & Mielke, 2013). The PDCA cycle is focused on a continuous quest to find improvement in product processes (Silva, A., Medeiros, C., Kennedy Vieira, R., 2017).

Qualifications of workers is a third fundamental principle of Lean leadership. Similar to the

self-development of the leaders themselves, the workers have to constantly develop as well. This development goes further than taking a class or learning technical procedures. The qualification of the workers happens on the work-floor, where they are constantly solving real-life problems. By empowering employees and making them responsible for their actions, a workers' solution-thinking ability will be developed (Dombrowski & Mielke, 2013).

Gemba (Genchi Gentbutsi) is the Japanese name for the work-floor and is the fourth

fundamental principle of lean. To understand the processes and find the root causes, leaders have to go to the work-floor and see the processes with their own eyes. Doing this shows the appreciation of the leaders towards the work-floor employees. Leaders can take proper decisions given the fact they got a first-hand impression of the issues in the processes (Dombrowski & Mielke, 2013).

Hoshia Kanri ensures that different teams at different levels have aligned goals regarding the

continuous improvement processes by showing them the target that has to be achieved. The latter is done by systematically aligning the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycles of the teams (Dombrowski and Mielke, 2013). In lean, the improvement activities are decentralized, as effective leadership in lean occurs from the upper level, as well as the lower levels in the organization (Mann, 2009).

To compliment the concept given, Jeffrey Liker and Gary Convis proposed a methodological process to adopt these aforementioned principles in the core values of a company searching to become lean. The Diamond Model for Lean Leaders (Fig. 4) describes a four-step cycle, where the focal point is constantly on the aforementioned True North principles.

Figure 4: The Diamond Model for Lean Leaders. Source: Liker, J. & Convis, G. (2011)

For the first step, the leader has to accept towards self-development and learn how to live the lean core values. Up next, we find the second step, where self-development leads to the coaching and development of followers. In the third step, the support for Kaizen on a daily basis is found; this is the step where the actual constant improvement takes place. The last step in the cycle is the creation of vision and the alignment of goals, through the setting of targets. Between every step, the leader undergoes short improvement cycles, using the Plan-Do-Check-Act system. The latter supports the process of constant improvement of the lean culture as well as employees (Dombrowski & Mielke, 2014).

Nevertheless, no broadly accepted term for lean leadership, or a consensus for a framework describing the process on how to achieve an optimal leadership style when facing lean adoption has yet been achieved. Moreover, this research focuses on finding optimal leadership behaviors to later configure a custom leadership style to catalyze lean adoption, hence, Dombrowski’s and Mielkes framework for “lean leadership”, is not taken into account for data research; rather, it is used to understand the approach taken by the different authors when researching on the topic. This delimitation would not affect the results of this research, since the mentioned framework proposes a path to become a lean leader. In contrast, this investigation aims to contribute with general understanding of lean management, and what

leadership factors catalyze its correct adoption within the different management tiers of the organization.

2.2. Leadership

Literature explains multiple definitions for leadership. Yukl (2013) emphasizes on the fact that there is not one correct definition of leadership, as the execution of leadership depends on the context the mentioned leadership is carried out (Yukl, 2013). However, to state the concept on how leadership is described in this research, three descriptions for leadership will be stipulated. For the first concept, Aij and Teunissen (2017) define leadership as “the process

by which one person sets the purpose or direction for one or more other persons and helps them to proceed competently and with full commitment” (Aij & Teunissen, 2017). Bass (2008) gives a second

definition for leadership as “the ability to influence, motivate, and enable others to contribute to the

effectiveness and success of the organization of which they are members”. Dekier (2012) also describes,

in a third definition, how leadership should be understood when a company faces lean adoption. He states that it is imperative that leaders are aware that their roles are dynamic, and they cannot constraint to a specific set of rules or a sequence of steps to achieve their goals. In his article, The Origins and Evolution of Lean Management System, he also specifies that a leader needs to be constantly conscious of the management style that is being carried on each situation. Additionally, he explains that a leader should be a catalyzer to improve the team members performance and is categorically unacceptable for him to take credit for his employee’s actions.

Decker gives a final recommendation for managers facing lean adoption: the imperative improvement of the leader’s soft skills. The reason for so, is the categorically importance of such skills on terms of social interaction. Daniel Goleman (1995), defines soft skills as the emotional intelligence of oneself; and that the possession of soft skills is a bigger determinant for an individual’s ultimate success or failure than technical skills or intelligence (Goleman, 1995).

Consequently, as it has been discussed before, lean management focuses more on the human factor than the technical skills when seeking for employee development in the lean culture. Thus, having strong communication and social skills, will facilitate and improve the performance of a team. Soft skills, also known as interpersonal skills, are vastly considered as critical factor to achieve organizational results within a company, with research supporting

the positive correlation between leader social skills and performance and salary (Riggio, R.E. & Tan, S.J., 2013).

2.2.1. Optimal leadership styles for lean adoption

When an organization undergoes a cultural change process, a leader is forced to tailor his leadership behaviors to the context he is in, as a different context leads to the need of different behaviors (Yukl, 2013; Aij et al., 2014; Yang, 2015). Organizations implementing Lean Management undergo immense and profound changes, and leaders have to modify their leadership behaviors to fulfil the distinct needs of lean (Aij et al., 2014; Dombrowski and Mielke, 2014; Aij, Visse & Widdershoven, 2015). When looking at studies on the role of leadership behaviour in relation to Lean Management implementation, only a few authors have managed to define this relationship (Tortella & Fogliato, 2017; Loh et al., 2017; Noqueira et al., 2018), resulting in mainly three leadership approaches linked to Lean Management implementation: Transformational, Transactional and Empowering leadership (Poksinska et al., 2013; Tortorella & Fogliatto, 2017; Alefari, et al., 2017; Tortorella et al., 2018; Noqueira et al., 2018; Burawat, 2019). To determine what behaviors construct the most optimal leadership approach to catalyse a successful Lean Management adoption, the styles of transformational, transactional and empowering leadership are decomposed into leadership behaviours that compose the mentioned styles.

Transformational leadership behaviour is, according to multiple studies, stated as the missing link

for a successful lean implementation (Poksinska et al., 2013; Tortorella & Fogliatto, 2017; Alefari, et al., 2017; Tortorella et al., 2018; Burawat, 2019). The transformational leader features four behavioural dimensions: (I) Idealized influence, where an idealized vision of the future is expressed; (II) inspirational motivation, the expression of positive messages to build confidence and stimulate others. Both of these dimensions possess charisma as an intrinsic characteristic. (III) The third behavioral dimension is individual consideration, where the individual needs and desires for development are considered. (IV) The last behavioral dimension is intellectual stimulation, here the subordinates' interests are heightened and the thinking out of the box attitude is stimulated to solve issues (Bono & Judge, 2004; Bass, 2008; Vito et al., 2014; Noqueira et al., 2018).

Transactional leadership is also stated to be a catalyzer to successful lean management

interaction between leader and follower (Vito et al., 2014). To foster the above, Avolio and Bass (2002) as well as Noqueira et al. (2018), state that transactional leaders exhibit two main behaviors: management by exception and contingent-reward behavior. Transactional leaders find comfort in working within boundaries set by organizations and are resisting towards change as they prefer to maintain the status quo (Schweitzer, 2014). Leaders are able to ensure a certain level of performance of their followers by rewarding and disciplining their efforts and achievements. Through constant monitoring of followers completing tasks and only taking actions when something is not going as expected, followers are pushed to achieve a certain goal (Schweitzer, 2014). Transactional leaders stipulate specific behaviors to ensure followers comply to set standards: I) Decision making is formal and limited to the leader. II) Leaders tend to reduce and discourage intrinsic behaviors through the following of formalized procedures (Schweitzer, 2014). III) To ensure compliance of the formalized procedures by follower’s leaders exhibit contingent reward behavior. Transactional leaders have a fast understanding and insight when followers achieve a predetermined goal and will reward them for their efforts (Noqueira et al., 2018). The ability to have a fast understanding and insight of specific situations is an important skill to have for the monitoring and checking of subordinates and to understand when to make interventions in the process or reward the subordinate (Bono and Judge, 2004; Bass, 2008; Noqueira et al., 2018). IV) The transactional leader may also own empathic behaviors to be able to reward the subordinate in a correct and proper way for their accomplishments (Bass, 2008).

Empowering is the last leadership pointed out by Noqueira et al. (2018) as being the main

element for a successful implementation of Lean Management. Empowering leadership is defined by Wong and Giesnner (2016) to be:

“The process of implementing conditions that enable sharing power with an employee by delineating the significance of the employee’s job, providing greater decision-making autonomy, expressing confidence in the employee’s capabilities, and removing hindrances to performance.”

This definition illustrates several behaviors featured by empowering leaders: (I) coaching, where the leader aims at the development and empowerment of the follower’s self-management traits, self-control and independency; (II) participative decision making, leaders employing empowering leadership behaviors are known for the decentralization of their powers to their followers which creates a shift of autonomy towards the followers. The

followers are involved in the decision-making processes as bureaucratic constraints are eliminated; (III) informing behavior, leaders are notifying their followers with information on the morals and philosophy of the company to ensure the follower sees the bigger picture of the organization. Empowering leadership behavior is leading to higher knowledge sharing and team efficiency, better in-role performance on individual and organizational level and higher creativity as the provided autonomy and freedom to work on tasks by themselves are strengthening innovative thoughts (Yang, 2015; Wong and Giesnner, 2016). Nevertheless, studies also point out that the responsibility that is provided to the followers are said to result in resistant responses, task uncertainty and lower performance outcomes due to a lack of proactivity from the leader (Langfred, 2014; Cordery, Morrison, Wright & Wall, 2010; Maynard, Gilson, Mathieu, 2012; Wong and Giesnner, 2016).

2.2.2. Leadership behaviors to catalyse a successful lean adoption

As it is reviewed on the previous chapter, there are optimal leadership styles suggested by the literature to foster a successful lean adoption process. Furthermore, these leadership styles are split into determinant leadership behaviors. This description will be useful for the development of empirical tools that will be used to gather data for its further analysis.

The most determinant leadership behaviors for the leadership styles suggested by literature is presented in table 1, followed by the description of the intrinsic characteristics of each of the mentioned behaviors.

Table 1: Leadership behaviors that catalyze a successful lean adoption process

1 Wang, Y., Yuan, C., & Zhu, Y. (2017)

2 Sandvik, A., Croucher, R., Espedal, B., & Selart, M. (2018)

3 Hamstra, M., Van Yperen, N., Wisse, B., & Sassenberg, K. (2014)

4 Dong, Y., Liao, H., Chuang, A., Zhou, J., & Campbell, E. M. (2015)

5 Kee, A. N. (2011)

6 Chen, G., Crossland, C., & Luo, S. (2015)

7 Smith, P., Anell, A., Busse, R., Crivelli, L., Healy, J., Lindahl, A., … Kene, T. (2012)

Han, J. H., Bartol, K. M., & Kim, S. (2015)

Leadership Behaviors Characteristics

Coaching Approach 1 • Search of win-win situation between employee/organization. • Cognitive skills and intellectual development of employees.

• Positive, constructive feedback oriented.

Intellectual Stimulation 2 • Employee autonomy and responsibility. • Intrinsic motivation development.

• Challenging tasks.

Goal Achiever 3 • Competence is measured on their level of performance in • Performance attainment & results oriented.

task completion.

Empowering team-members 4

• Responsibility & authority are dispersed among different

tiers in the organization. • Motivate employees’ creativity for task performance,

enhancing innovation for standard procedure.

Standard Procedures 5 • Clear roles and responsibilities to carry a task within the organization.

• Focused on achieving accurate, regular outcomes.

Penalize Mistakes 6 • Manages activities rather than managing people. • Result oriented & internal control focus.

• Severe, negative methods for giving feedback.

Structured Governance 7

• Focuses on setting priority tasks or procedures within the

organization. • Performance monitoring of their employees. • Responsibility & accountability on each individual's tasks.

Reward Achievement 8 • Rewards based on each individual's job performance.

2.3. Management Tiers

Over the years, many studies have focused on the relationship between leadership and the top management levels in organizations. Such fact was mainly due to the position held that, middle and work-floor tiers have no considerable impact on achieving success in the company’s performances (Oshagbemi, & Gill, 2004). This perspective changed throughout time, and organizations started implementing a more horizontal hierarchy, where decision-making was empowered to lower levels in the organization and each hierarchical level got their own responsibilities (Grover, Jeong, Kettinger & Lee; Oshagbemi, & Gill, 2004; Yukl 2013). Each of the different tiers contribute with the organizations’ ultimate objective with different tasks and levels of responsibility.

2.3.1. Involvement of the management tiers

A company represents a complex, interrelated system, where all parts ought to work in tune to be able to reach a same goal; business development. Each management tier represents a critical agent for the holistic system of a company. Therefore, each tier performs different tasks that complement each other’s tasks. Likewise, different requirements are expected from each of the levels. Nevertheless, none of these actions are isolated. They are closely intertwined. Therefore, a holistic alignment of strategy, vision and mission is required to achieve successful rates of lean adoption. The responsibilities and expectations for each management tiers when facing lean adoption are explained in the following paragraphs.

Senior management level dealing with lean management is responsible for introducing,

implementing and adapting a long-term view and lean culture within the organization (Hermkens, Dolmans & Romme, 2017). It also carries an essential role when creating a fostering an environment for individual development and lean adoption (Mann, 2009). The latter is a challenging task, as upper-level managers tend to focus on tools and techniques rather than a profound cultural change that will change the mindset and behavior among the organizational leaders (Hermkens et al., 2017). To accomplish the aforementioned, the upper management level needs to lead by example; by being committed to the philosophy, monitoring the implemented measures and by visiting the work floor (Mann, 2009; Holmemo & Ingvaldsen, 2015; Hermkens et al., 2017).

The middle management involved with lean management is the tier having a difficult position,

the translation, interpretation and implementation of strategic change initiatives to the daily operations on the shop floor. The latter is due because the middle managers are seen as the important player in the facilitating of lean initiatives in the organization, due to their creative ideas and internal networks. Nevertheless, the middle management is dependent on what the upper management expects from them. Here the middle management has a dual role, the role of change leader and the role of executor. It depends on the organizational context, type of strategic change, leadership style of managers, and tasks delegated by the upper management which role is appropriated at what time (Hermkens et al., 2017). Despite the important key position of the middle management in relations to lean management implementation and their responsibility for several operational units within organizations, Holmemo and Ingvaldsen (2015) state that this level of management is often involved too late or too little in the lean implementation.

The work-floor level managers are concerned with the internal decision making, structuring,

coordinating and facilitating work activities. Their main task is the supervision of subordinates, negotiator and monitoring the daily work flows. The lower tier has a short-term perspective of several weeks to 2 years (Grover et al., 1993; Yukl, 2013). Besides the operational role this management level performs, no further literature was found on the work-floor management’s role during lean implementation.

2.3.2. The Domino Effect/ Cascading Effect

Nealey and Blood (1968) and Lowe et al., (1996) published studies suggesting that a gratified leadership approach at one level does not automatically work or satisfy at the level above or below (Mann, 2009). Despite the latter, leadership should be demonstrated at all hierarchical levels for organizational success (Khaleelee and Woold, 1996). Supporting such statement, several studies present evidence that the automatic cascading of leadership, also known as the falling dominoes effect, is a phenomenon present in organizations where a management decision reaches the different tiers of the organization in the form of dominoes falling towards each other and creating a chain reaction. A consequence, lower management tiers replicate those behaviors of their upper levels. (Bass, et all., 1987; Lowe, Gale & Sivasubramaniam, 1996; Nealey & Blood, 1968; Coad, 2002). A practical example for these statements is explained by Murphy, L. (2005), in his paper, Transformational leadership: a

cascading chain reaction. Murphy proposes that certain leadership behaviours are replicated, in

empowering leadership behaviour, he states that when lower management tiers start to receive more decision power within the organization’s structure, this behaviour of redistributing power is presented among similar and lower management tiers, where all employees start replicating the empowerment decisions.

Relating the aforementioned to lean management, it is of imperative to note that effective lean management performance comes from both, top-down and bottom-up (Liker, 2004; Mann, 2009). Nevertheless, managers involved in lean management tend to take on one specific leadership style, regardless of their hierarchical position (Tortorella & Fogliatto, 2017). The engagement with only one leadership style may not work or satisfy different levels of management, as each hierarchical level has different tasks and responsibilities when facing lean management implementation (Grover, Jeong, Kettinger & Lee, 1993; Yukl 2013). Furthermore, the involvement of all three aforementioned levels is important in lean implementation, as a flawed design of lean at one of the levels can lead to the failing of the attempt to implement lean (Mann, 2009).

2.3.3. Katz’s managerial skills & tiers model

Robert Katz, in his research, Skills of an effective administrator, identifies three basic skills that every successful manager ought to portray in varying degrees, according to the tier of management he is operating in. This set of basic skills is formed by technical, human and

conceptual skills.

The categorization of these skills was Katz’s response to the issue that organizations where fronting on the second half of the twentieth century. Companies’ where trying to identify a stereotype that made an “ideal executive”. Katz’s response was that they should not lose focus on their real concern: what a man can accomplish. His purpose then was to not emphasize on what “good executives are (innate traits and characteristics), but rather on what they do (the leader skills they exhibit when performing their jobs effectively) (Katz’s, 1974).

To understand how the term skill is treated in this research, Katz (1974) explains:

“[…] skill implies an ability which can be developed, not necessarily inborn, and which is manifested in performance, not merely in potential. So, the principle criterion of skillfulness must be effective action under varying conditions”.

To understand the underlying concept taken for administrator, Katz’s follows, “[…] is one who (a) directs the activities of other persons and (b) undertakes the responsibility for achieving certain objectives through these efforts.”

For the technical skill, it describes the understanding and proficiency of techniques and procedures. It requires specialized knowledge with the ability to apply it under varying circumstances. Technical skills are the most concrete skills, and in this era of specialization, they are required (Katz, 1974). Following next, the human skills describe the ability of managers to function through cooperative effort within the team. “This skill is demonstrated in the way the individual perceives (and recognizes the perceptions of) his superiors, equals, and subordinates, and in the way he behaves subsequently.” (Katz, 1974). Therefore, a manager that can accept viewpoints and perceptions different from his own, is skilled in understanding and communicating with others in their own contexts (Katz, 1974). Finally, the conceptual skill describes the ability to understanding the holistic view of a company. It describes the skill to identify different functions in a company and how the relation and variation of each of them affect the others. It encompasses a global perspective, including the position of the company industry, with the community, political and social. (Katz, 1974).

After describing the skills required for effective leaders, Katz’s carries on with the categorization of the skills required, accordingly to each management. Fig 5 explains his description of the skills required for each management level, as well as

Figure 5: Katz's three managerial skills model. Source: Adapted from Katz (1974).

A graphical representation of the skill distribution among the organizational levels for each management level is shown in Fig 5. It is observable that top management requires a wider development on the conceptual skill, given the fact that their line of management requires the people involved in these stances to have a holistic understanding on the company’s operations. Contrasting this circumstance, dominance of technical skills is not mandatory for a senior level manager, since its involvement with these processes is rather indirect.

Moreover, supervisory management, also known as work-floor level, is in charge of overseeing the operational processes of the company. Hence, technical knowledge and the skills to perform such activities are required for this tier of management. On the other side, having a global vision of the company and its strategy is not crucial for the work-floor tier to achieve its goals.

Afterwards, middle management is considered to be the link between these two management tiers. Therefore, these managers ought to dominate both conceptual and technical skills in order to facilitate communication and understanding between senior and supervisory management tiers.

Even though all three levels require the same set skills, each of the management tiers involve different specific activities, demanding distinct abilities to be fulfilled. Nonetheless, human

skills prove to be the most consistent skill required among any level of analysis. The human

factor is the glue that enables the rest of the skills to work in symbiosis and achieve the aimed results. The main bridge that enables these skills to be developed and mastered, is an optimal leadership approach originated in managers performing in the above-mentioned tiers, that can catalyse the emergence of a constant-improving culture.

3. Methodology

______________________________________________________________________

In the following chapter, the methodology fitting this research is elaborated. To start, the research philosophy will be outlined, followed by the documentation of the research approach. Finally, an overview of the overall methodology approach taken in this research is depicted.

3.1. Relativist Ontology & Social Constructivism: Research Philosophy

The purpose of this research is to comprehend what leadership behaviors suit best at each management tier in order to achieve lean management adoption in an organization’s culture. Hence, it is understood that interactions between people and how communication is transmitted or perceived, depends mostly on the perception of each of the parts involved, where each part can have different interpretations of a same “real” event (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, Jackson, & Jaspersen, 2018). Furthermore, the research is based on the assumption that: the perception and interpretation of real events of each of the team members within a group, is in direct dependence with the background of such member: age, motivations, interests. (Easterby-Smith, et al, 2018). With such statement, it is specified that a singular reality does not exist; outcomes or consequences in a given situation can be directly attributed to the individual or group sharing the same background (Easterby-Smith, et al, 2018).

Thus, the aim was to find a strategy that can guarantee the clearest data compilation possible. For matters of ontological and epistemological stances, this research underlines such concepts as: “ontology is about the nature of reality and existence; epistemology is about the theory of

knowledge and helps researchers understand the best way of acknowledging the topic on research

(Easterby-Smith, et al, 2018). As it is delimited by these concepts, both ontology and epistemology focus in the observation of a same phenomenon through different perspectives, that complement each other in order to have a holistic understanding of such phenomenon and its particular context. Hence, finding an ontological an epistemological approach that match both the nature of the research as well as the related philosophical postures is of crucial importance. The definition of such approaches would then become the pillars for the following steps on data collection and data analysis.

The ontology approach is determined as relativist ontology. The relativist ontology approach suggests that “reality is determined by people rather than by objective and external factors” (Easterby-Smith, et al, 2018). In other words, events in the real world are only a part of reality; reality is constructed after an individual process such events through a personal understanding of