LICENTIATE THESIS

E

XPLORING SUSTAINABLE

MANUFACTURING PRINCIPLES

AND PRACTICES

Claudia Alayón

DISSERTATION SERIES No. 16, 2016 JÖNKÖPING 2016

ii

Exploring Sustainable Manufacturing Principles

and Practices

Claudia Alayón

Department of Industrial Engineering and Management School of Engineering, Jönköping University

SE-551 11 Jönköping, Sweden Claudia.Alayon@ju.se

Copyright © Claudia Alayón 2016 Dissertation Series No. 16

Publisher: School of Engineering, Jönköping University P.O. Box 1026

SE-551 11 Jönköping Tel.: +46 36 10 10 00 www.ju.se

Printed in Sweden by: Ineko AB

Kållered, 2016

v

Abstract

The manufacturing industry remains a critical force in the quest for global sustainability. An increasing number of companies are modifying their operations in favor of more sustainable practices. It is hugely important that manufacturers, irrespective of the subsector they belong to, or their organizational size, implement practices that reduce or eliminate negative environmental, social and economic impacts generated by their manufacturing operations.

Consequently, scholars have called for additional studies concerning sustainable manufacturing practices, not only to address the paucity of related literature, but also to contribute to practitioners’ understanding of how to incorporate sustainability into their operations. However, apart from expanding the knowledge of sustainable manufacturing practices, it is first key to understand the ground set of values, or principles, behind sustainable manufacturing operations. For that reason, the purpose of this thesis is to contribute to the existing body of knowledge regarding sustainable manufacturing principles and practices.

The results presented in this thesis are based on three studies: a systematic literature review exploring sustainability principles applicable to manufacturing settings, and two empirical studies addressing sustainable manufacturing practices.

In general, it is concluded from the literature that there is a little knowledge about sustainability principles from a manufacturing perspective. In relation to the most common sustainable manufacturing practices, it is concluded that these practices mainly refer to energy and material management, and waste management. Similarly, the study of the adherence of sustainable manufacturing practices to sustainable production principles concluded that the principles concerning energy and materials conservation, and waste management were found to create the highest number of practices. Although most manufacturers still engage in reactive sustainable manufacturing practices driven by regulatory and market pressures, some industrial sectors were found to be more prone to develop proactive sustainable manufacturing strategies than others. Furthermore, SMEs were found to lag behind large organizations regarding adherence to sustainable manufacturing principles.

Keywords: Sustainable manufacturing principles, sustainable manufacturing practices

vii

Acknowledgments

This thesis owes its existence to the help, support and inspiration of several people. Foremost, I would like say a big thank you to my supervisors: Prof. Kristina Säfsten and Prof. Glenn Johansson. Thank you for your time, for being always available to advise me, and for your valuable feedback. This thesis would not have been possible without your continuous support, patience, encouragement and knowledge. Words cannot express how fortunate I feel to have you as my supervisors.

I am grateful to all the companies and respondents, who participated in the interview study, for their cooperation and time. My gratitude also goes to the CEOs from the Swedish surface treatment SMEs who participated in the focus group discussion and the online questionnaire.

I owe thanks to Anna Sannö, my co-author in one of the appended papers. I really enjoyed our “Friday e-mail conversations” and creative discussions.

I wish to express my gratitude to my former and present colleagues at the department of Industrial Engineering and Management, School of Engineering, Jönköping University, for providing a friendly working environment, and for helping me to improve my Swedish. I would like to thank Dean Ingrid Wadskog and the head of the department Anette Johansson for the whole hearted support extended to me throughout the conduct of the research.

To all the PhD students at the School of Engineering, thank you for all the memorable moments. To my close friends, thank you for the formatting tips, the casual conversations about small and big things, and most of all, thank you for being there whenever I needed a friend.

A million thanks to my mom Beatriz, my late dad Pedro Nel, and my grandmother Paloma. Thanks for your unconditional love, for all that you are and who you have taught me to be. Every single day I thank God for you.

Last, but not least, I would like to thank my fiancé Diego for inspiring me with his passion for research, and for being my love, best friend and partner in life.

Claudia Juliana Alayón G.

ix

List of appended papers

This thesis is based on the following papers, which are referred to in the text by their roman numerals. The contributions made by the authors are described for each appended paper.

Paper I

Alayón, C., Säfsten, K. and Johansson, G. (2013). Sustainability in manufacturing: A literature review. Presented at the 20th EurOMA Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 7-12 June 2013.

Contribution to Paper I: Alayón carried out the literature review and analyzed the theoretical data, together with Säfsten and Johansson. The co-authors provided comments and checked the quality of the paper. Alayón was the corresponding author and presented the paper.

Paper II

Alayón, C., Säfsten, K. and Johansson, G. (2016). Conceptual sustainable production principles in practice: do they reflect what companies do? Accepted for publication September 2016 Journal of Cleaner Production. Contribution to Paper II: Alayón, together with Säfsten, planned the empirical studies, which were carried out by Alayón. The data collection tool was designed by Alayón. The data collection tool was refined by Säfsten. The analysis was a collaborative effort between all the authors. Säfsten and Johansson provided comments and checked the quality of the paper. Alayón was the corresponding author.

Paper III

Alayón, C., Sannö, A., Säfsten, K. and Johansson, G. (2016). Sustainable production in surface treatment SMEs: an explorative study of challenges and enablers from the CEOs perspective. Presented at the 1rst Global Cleaner Production and Sustainable Consumption- GCPSC Conference, Sitges, Barcelona, 1-4 November, 2015

Contribution to Paper III: All the authors contributed to the planning of the empirical studies. Alayón and Sannö designed the data collection tools and carried out the empirical studies. Säfsten and Johansson provided comments and checked the quality of the paper. Alayón was the corresponding author and presented the paper.

x

Additional publications by the author, but not included in the thesis

Alayón, C., Säfsten, K. and Johansson, G. (2014). Sustainable Manufacturing Principles in SMEs Presented at the EurOMA Sustainability Forum: A literature review, Gröningen, Netherlands, 24-25 March 2014.

Contribution: Alayón carried out the literature review. Säfsten and Johansson provided comments and checked the quality of the paper. Alayón was the corresponding author and presented the work-in-progress (WIP) paper.

Alayón, C., Säfsten, K. and Johansson, G. (2014). Implementation of sustainable production principles within Swedish manufacturers. In Proceedings of the 6th International Swedish Production Symposium, Göteborg, Sweden, 16-18 September 2016.

Contribution: Alayón, together with Säfsten, planned the empirical studies, which were carried out by Alayón. The analysis was a collaborative effort between all the authors. Säfsten and Johansson provided comments and the quality of the paper. Alayón was the corresponding author and presented the paper.

xi

Table of contents

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 Sustainability in manufacturing operations ... 1

1.2 Problem area ... 4

1.3 Purpose and research questions ... 6

1.4 Scope of the thesis ... 7

1.5 Outline of the thesis ... 8

CHAPTER 2 FRAME OF REFERENCE ... 11

2.1 Sustainable development and manufacturing ... 11

2.2 Sustainability principles ... 12

2.3 Sustainable manufacturing principles ... 13

2.3.1 LCSP Sustainable production principles ... 15

2.4 Sustainable manufacturing practices ... 16

CHAPTER 3 RESEARCH METHODS ... 19

3.1 Research design ... 19 3.2 Research methods ... 21 3.3 Data collection ... 21 3.3.1 Paper I ... 23 3.3.1 WIP paper ... 24 3.3.2 Paper II ... 24 3.3.3 Paper III ... 25 3.4 Data analysis ... 27 3.5 Research quality ... 29

CHAPTER 4 SUMMARY OF RESULTS ... 33

4.1 Current state of sustainable manufacturing principles ... 33

4.2 Current sustainable manufacturing practices ... 38

4.2.1 Exploration of sustainable manufacturing practices published in the literature ... 38

4.2.2 Exploration of sustainable manufacturing practices in a practical context. ... 42

4.3 Adherence of sustainable manufacturing practices to sustainable manufacturing principles ... 48

xii

CHAPTER 5 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS ... 55

5.1 Discussion ... 55

5.2 Discussion of the research method used ...63

5.3 Conclusions ... 64

5.4 Scientific and industrial contribution of the research ... 66

5.5 Suggestions for future research ... 67

xiii

List of figures

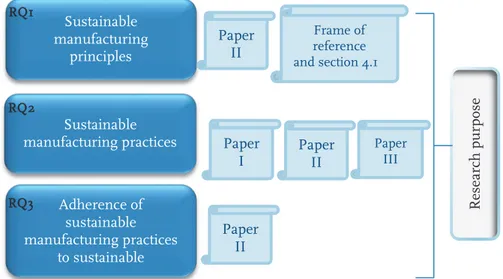

Figure 1. Research questions in relation to the research purpose ... 20

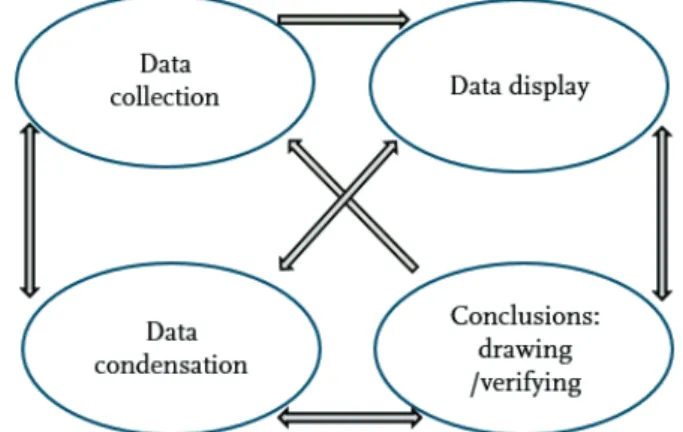

Figure 2 Data analysis process ... 28

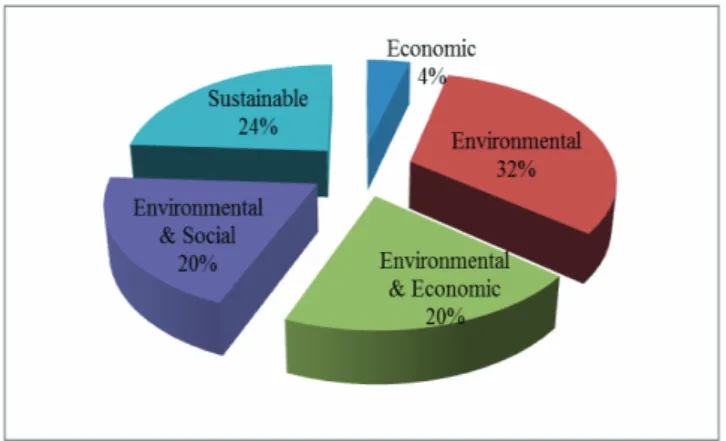

Figure 3 Dimensions of sustainable development addressed in the sample 39

List of tables

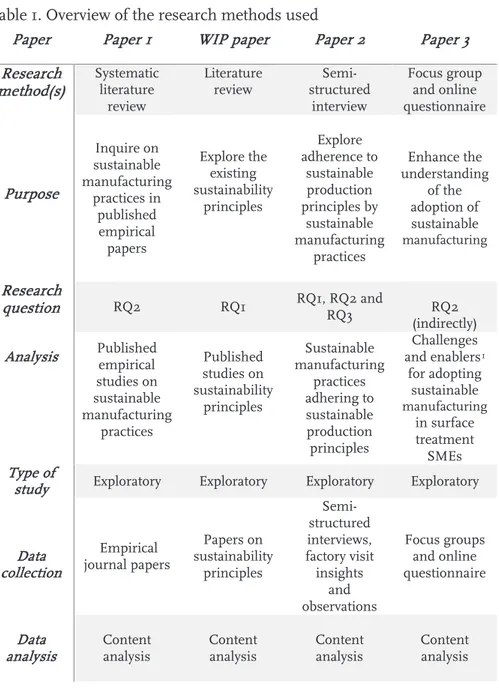

Table 1. Overview of the research methods used ... 22Table 2. Paper II sample overview ... 25

Table 3. Identified principles of sustainable production ...35

Table 4. LCSP principles of sustainable production ... 38

Table 5. Categorization of reviewed papers by sustainability aspects that were addressed (presented in Paper I) ... 40

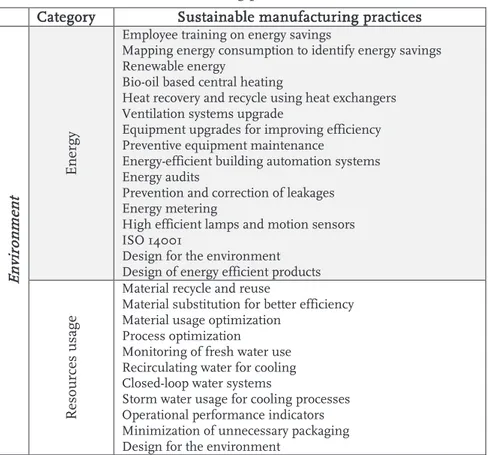

Table 6. Sustainable manufacturing practices ... 43

Table 7. Challenges for sustainable manufacturing and manufacturing practices needed to overcome them ... 46

xv

Definitions

Manufacturing: The interconnected activities and operations involved in producing a single part, or multiple parts to be assembled to form a final product. In manufacturing, raw materials are transformed with the assistance of technology, physical and chemical processes, labor, and tools, into components or final products within manufacturing industries. Therefore, it is possible to state that while all manufacturing is a type of production, all types of production do not always involve manufacturing (adapted from CIRP, 1990; Bellgran and Säfsten, 2010).

Production: The process of transforming a set of input elements into a set of output elements with economic value. Production constitutes the outcome of the industrial work in different fields of activity (e.g. agriculture production, music production, oil production, energy production, manufacturing production). The outcome of the production could be either a tangible, or intangible product (production by service). The research presented in this thesis adopts the notion of production as superior manufacturing, since the term production is associated with a branch of industry or line of business (adapted from CIRP, 1990; Murthy, 2005; Bellgran and Säfsten, 2010).

Sustainable manufacturing: The ability to smartly use natural resources for manufacturing by creating products that, by using new technology, following regulatory measures and adopting coherent social behaviors, are able to satisfy economic, environmental and social objectives, thus preserving the environment while continuing to improve the quality of human life (Garetti and Taish, 2011).

Sustainable manufacturing practices: The actions, initiatives, and techniques that positively affect the environmental, social or economic performance of a manufacturing firm, helping to control or mitigate the impacts of the firm’s operations on the triple bottom line.

Sustainable manufacturing principles: Fundamental values that guide organizational practices relating to the environmental, social and economic sustainability dimensions, with the aim of attaining sustainable manufacturing operations (adapted from Veleva and Ellenbecker, 2001). Sustainability principles: Deal with moving organizations toward sustainability by changing their vision/mission, their use of natural and

xvi

human resources, their production and energy practices, and their products and waste management (Shrivastava and Berger, 2010).

Sustainable production: “The creation of goods and services using processes and systems that are non-polluting; conserving of energy and natural resources; economically viable; safe and healthful for employees, communities and consumers; and socially and creatively rewarding for all working people” (LCSP,1998; Veleva and Ellenbecker, 2001).

1

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

This chapter describes the background and the problem area. Also, the purpose and research questions are presented. The chapter ends with the scope and the outline of this thesis.

1.1 Sustainability in manufacturing operations

Companies are considered to be “key players on the societal path towards sustainability” (Koplin et al., 2007, p. 1060). In the past, most companies have separated sustainability considerations from their own business strategies and performance evaluation; in this way, economic performance indicators have been the main criteria by which companies have been assessed (Clarkson, 1995). This scenario began to change in the late 1980s when a few manufacturing sectors started adopting practices to help with the minimization or elimination of waste. These were the first signs of sustainable manufacturing (Lazlo et al., 2013; Courtice, 2013).

The growing trend of considering sustainability in manufacturing settings is clearly evident in government initiatives, such as the EU’s growth strategy “Europe 2020”, that calls for joint efforts towards a “resource efficient Europe" (European Commission, 2010). This government initiative is aimed at committing both the EU and its member states to this sustainability agenda, supporting the shift towards a low carbon economy, and promoting an increase in the use of renewable energy sources, without compromising energy efficiency (European commission, 2010). Nevertheless, at present, it is not only the policy-makers who are pursuing the establishment of a long-term environmental, economically, and socially sustainable society, but also consumers, whose awareness of sustainability issues along all stages of a product’s life cycle has significantly increased (Vermeir and Verbeke, 2006; UNEP, 2012; Nielsen; 2015). These demanding conditions have driven manufacturers to respond to sustainability issues.

Global economies are strongly influenced by the manufacturing sector. This sector is made up by of a large variety of subsectors, ranging from basic to advanced production practices and techniques, involving different sizes of firm, generating development and employment. Data, provided by the statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community (NACE), placed manufacturing as the second largest

2

economic sector in the European Union (Eurostat, 2012), with approximately 2,1 million companies employing around 30 million people and thereby contributing to 22.4% of employment within the EU non-financial businesses economy (Eurostat, 2012). These statistics reflect how the industrial sector plays a significant role in the economic well-being of Europe (European commission, 2015). However, this sector is also responsible for a variety of negative impacts on global environmental sustainability. As an example of the key role this sector plays in global sustainability, the industry sector consumes the same amount of energy and emits the same level of greenhouse gases as the transport and construction sectors (IEA, 2012; UNIDO, 2014). Still, the energy demands of the industry sector have been growing faster than in any other sector, contrasting with the continuing efficiency gains (IEA, 2012).

One of the most important events that helped to establish and disseminate the sustainability concept was the publication of “Our Common Future” (Brundtland,1987), in which the first definition of sustainable development was presented. This report is widely known as the Brundtdland report in reference to Gro Harlem Brundtland, who chaired the commission to whom this report was presented. In the Brundtland report, the United Nations, or more specifically, the World Commission on Environment and Development, called on countries around the world to assume the responsibility for the anthropogenic impact on the environment. From that point, sustainable development has formed an essential concept that has shaped the manufacturing scenario. The term sustainable development covers the three dimensions (social, economic and environment) that constitute the triple bottom line (Elkington, 1998).

Aware that the production of every product or service has repercussions on the environmental and social dimensions of sustainability, sustainability demands are assumed to be tackled by all type of manufacturers, regardless of their organizational size and manufacturing subsector. The increase in academic research with a focus on sustainability in operations (Corbett, 2009) is a reflection of the strong sustainability demands on manufacturers. However, in the sustainable manufacturing literature, previous studies have mainly addressed sustainability from its environmental perspective (e.g. Seuring and Müller, 2008; Despeisse et al., 2012), and mainly studied large companies (e.g. Gaughran et al., 2007; Seidel et al., 2009). For example, a study presenting short-term projections of the manufacturing scenario in the United Kingdom (Tennant, 2013) stated that manufacturing strategies largely involve energy and resource efficiency programs. In spite of this bias on focusing on the environmental dimension of sustainability within large organizations, there is an

3

undeniably increasing interest in sustainability from its triple bottom line perspective, from both practitioners and academics.

Recognizing the outstanding and highly visible participation of the manufacturing sector in global sustainability, stakeholders over the years have developed initiatives for integrating sustainable development approaches at company, supply chain and economy levels. An example of this is the EU’s growth strategy Europe 2020, an effort to guide Europe towards a more sustainable, inclusive and smart economy (European Commission, 2010).The concern of manufacturers regarding the impact of their operations on sustainability is higher than it was 30 years ago (Winroth, 2012) but, to meet the EU´s national targets relating to employment, energy/climate change, innovation, education and social inclusion, manufacturers, irrespective of size or subsector, must take decisive action. Apart from governmental pressures for adopting sustainable manufacturing practices, the literature has reported that organizations engaging in sustainable supply chain management practices are also strongly driven by pressure from consumers, workers, investors and unions (Hall, 2000; González-Benito and González-Benito, 2005; Mollenkopf et al., 2010), compliance with legal requirements (Zhu and Sarkis, 2006; Zhu et al., 2008), improvements in the company´s reputation, cost reduction, improvement of overall performance and the creation and maintenance of competitive advantage (Noori and Chen, 2003; González Benito and González-Benito, 2005).

This broad variety of stakeholder pressures for integrating sustainable development into manufacturing, plus the perceived benefits (i.e. economic savings and positive image) derived from environmental and social initiatives (Petrini and Pozzebon, 2010), has shaped the growing trend in firms worldwide for integrating sustainability into their business practices (Jones, 2003; Bielak et al., 2007; Gunasekaran and Spalanzani, 2012). The consequences of these pressures and drivers for sustainability produce the existing challenging scenario for manufacturers. As the pressures grow, there has been a call to clarify what sustainability is from an operational perspective for manufacturers, as well broaden the understanding about the way in which sustainability might be attained within manufacturing organizations. Increasing the knowledge regarding how organizations can operationalize sustainability constitutes a valuable contribution towards the attainment of national and global sustainability goals.

4

1.2 Problem area

Sustainability demands are assumed to be tackled by all type of manufacturers. However, some manufacturers such as SMEs still lack knowledge of how to attain sustainable manufacturing (Seidel et al., 2009). A basic starting point to support all type of manufacturers aiming at sustainable manufacturing is to broaden the knowledge about what sustainability is from an operational perspective, and to enhance the understanding about the ways in which sustainability can be incorporated by manufacturers, regardless of their size. Following this line of reasoning, by studying sustainable manufacturing principles and translating these principles into practice, it should be possible to connect the conceptual sustainable manufacturing principles with practice.

From a semantic point of view, principles constitute values that guide actions, conducts and organizational practices (Glavič and Lukman, 2007; Shrivastava and Berger, 2010). In the literature, sustainable manufacturing principles have been defined mainly from a broad and conceptual perspective, and have mostly addressed environmental concerns (e.g. Al-Yousfi, 2004; Tsoulfas and Pappis, 2006; Lindsey, 2011). Academics have also called for a better understanding of the empirical reality surrounding the adoption of these sustainability principles among organizations (Shrivastava and Berger, 2010). Furthermore, further studies of sustainability principles from an operative perspective and taking a triple bottom line approach are necessary in order to address this knowledge gap.

Using the manufacturing lens, sustainable production principles have been associated with guiding and moving companies closer to a sustainable production state by addressing aspects such as resource use, energy practice, product and waste management, thereby making companies more responsive to sustainability demands (Shrivastava and Berger, 2010). The literature presents some studies that discuss sustainability principles from an operative perspective (Gladwin et al., 1995; Al-Yousfi, 2004; Tsoulfas and Pappis, 2006; Lindsey, 2011; Despeisse et al., 2012). However, only two of these studies introduced sets of sustainability principles addressing the three dimensions of sustainability (Veleva and Ellenbecker, 2001; Despeisse et al., 2012), with none of them including empirical data on the operationalization of the principles from the perspective of both large companies and SMEs.

To this point, it is clear the importance of exploring sustainable manufacturing principles for a deeper understanding of the sustainability demands, as well as taking the opportunity to research the whole manufacturing sector in a more comprehensive manner by including

5

manufacturing companies regardless of their size. Now, let us consider the other aspect dealt in this thesis: sustainable manufacturing practices.

The study of sustainable manufacturing practices is critical in broadening the understanding of how sustainability might be incorporated into manufacturing operations. According to Roberts and Ball (2014), many sustainable manufacturing practices are being overlooked at a factory level because they are not being reported at all within academic and industry literature. Nevertheless, it would appear from the published body of studies on sustainable manufacturing practices, that further studies of this subject are needed (Despeisse et al., 2012; Roberts and Ball, 2014).

The literature on sustainable manufacturing practices has predominantly focused on the environmental dimension of sustainability (e.g. Montabon et al., 2007; Yüksel, 2008; Despeisse et al., 2012; Schoenherr and Talluri, 2013; Singh et al., 2014; Roberts and Ball, 2014). Most studies have been of large companies (Petrini and Pozzebon, 2010). Consequently, there are a significantly smaller number of studies about sustainable manufacturing practices in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (e.g. Biondi and Iraldo, 2002; Vives, 2005; Lawrence et al., 2006). The current body of studies also shows how little attention research into sustainable manufacturing practices in SMEs has received among scholars (e.g. Kurapatskie and Darnall, 2013).

Based on the above, and on the evident imbalance of research with respect to organizational size, it can be stated that there is a need for further studies exploring sustainable manufacturing practices from a triple bottom line perspective and using a representative/inclusive empirical sample of the manufacturing sector (i.e. equally involving companies regardless of their size). Correcting this paucity of research into sustainable manufacturing practices is required not only to obtain a comprehensive understanding of how the manufacturing sector is adapting its operations to be more responsive to sustainability demands, but also to help companies achieve sustainability objectives (Roberts and Ball, 2014). As further studies of the operationalization of sustainable manufacturing principles and sustainable manufacturing practices are needed, a way of connecting these two areas may be by exploring how manufacturers’ operations (practices) adhere to sustainable manufacturing principles. Increased knowledge about the connection between sustainable manufacturing principles and sustainable manufacturing practices is needed to show, from an empirical perspective, how high level sustainability concepts might be incorporated into daily manufacturing operations.

Thus, this thesis is based on the need for further studies: (i) of the operationalization of sustainable manufacturing principles; (ii) exploring

6

sustainable manufacturing practices and (iii) to find a cohesive connection between conceptual sustainable manufacturing principles and sustainable manufacturing practices. Similarly, the small amount of research on sustainable manufacturing practices shows that there is a lack of research involving a triple bottom line approach of sustainability, with such work being limited to large companies. The motivation for this research, coupled with the lack of existing studies, shows that research on sustainable manufacturing practices is still in its infancy, thus constituting a promising and interesting field of research.

1.3 Purpose and research questions

This thesis attempts to address the apparent research gap, or lack of insights, in studies connecting conceptual sustainable production principles (involving the three dimensions of sustainability) with sustainable manufacturing practices (considering all sizes of companies). The purpose of this thesis is to contribute to the existing body of knowledge regarding sustainable manufacturing principles and practices.

To fulfill this purpose, the following research questions were considered:

RQ1. What is the current state in the literature regarding sustainability principles aimed at manufacturing industries?

Answering this question should provide a better understanding of the existing state of the published scientific material, or the existing body of knowledge on sustainability principles that could be potentially implemented within a manufacturing context.

RQ2. What are the main aspects that current sustainable manufacturing practices are responding to?

This research question hopes to provide a better understanding of the main sustainability aspects being addressed though sustainability practices among manufacturers.

RQ3. How do manufacturing practices adhere to sustainable manufacturing principles?

7

This research question involves the analysis of how manufacturers operations currently adhere to sustainable manufacturing principles.

1.4 Scope of the thesis

The research presented in this thesis explores the existing body of knowledge regarding sustainable manufacturing principles and practices, therefore the unit of study is the manufacturing company. The context of the research is the integration of the fields of operations management and sustainability, which some scholars also refer as the field of sustainable operations management (Kleindorfer et al, 2005; Drake and Spinler, 2013; Gunasekaran and Irani, 2014). This field is relevant to the future of manufacturing as it plays a crucial role in providing mode of actions or solutions for the current sustainability challenges faced by many companies (Kleindorfer et al, 2005). The research follows the triple bottom line approach defined by Elkington (1998), who stated that organizations looking to achieve sustainable development need to work on three dimensions: environment or planet, social or people, and economics or profit. Therefore, all three dimensions of sustainability were considered in order to address the purpose of this research, contrary to the majority of studies within operations management literature that have focused on the environmental issues while overlooking the social dimension of sustainability (Kleindorfer et al., 2005).

Considering the phenomenon to be studied (i.e. sustainable manufacturing practices and principles), the unit of study, and in order to prepare the groundwork for the subsequent theoretical framework, it is pertinent to explain what it is understood by manufacturing. This distinction is relevant, as scholars in both the operations management and the sustainability fields seldom present precise definitions of manufacturing and production, and often use these terms interchangeably (CIRP, 2014). In this research, manufacturing is defined as the interconnected activities and operations involved in producing a single part, or multiple parts to be assembled to form a final product. In manufacturing, raw materials are transformed, with the assistance of technology, physical and chemical processes, labor, and tools into components or final products within manufacturing industries. It is possible to state that while all manufacturing is a type of production, all types of production do not always involve manufacturing. Although this definition is adapted from previous definitions given by CIRP (1990) and Bellgran and Säfsten (2010), it differs from the latter one in the sense that manufacturing is not considered as superior production, but on the

8

contrary, this research uses the notion that production is superior manufacturing (CIRP, 1990). Thus, the manufacturing definition adopted in this research is consistent with the use of the term within leading sustainability literature in studies addressing the manufacturing industry. Production is defined as the process of transforming a set of input elements into a set of output elements with economic value. It is the outcome of the industrial work in different fields of activity (e.g. agriculture production, music production, oil production, energy production, manufacturing production). Therefore, by understanding production as superior manufacturing, the term production is associated with a branch of industry or line of business, making the distinction between production related to tangibles (i.e. production by integration or disintegration) or intangible products (i.e. production by service) possible. The former definition was adapted from CIRP (1990), Murthy (2005), and Bellgran and Säfsten (2010).

However, since there is a lack of consensus among academics as to the use of manufacturing and production terms, this research sometimes presents these terms interchangeably but only for citation purposes (e.g. sustainable production principles and sustainable manufacturing principles). The author of this research is aware of the difference between these definitions as stated above.

1.5 Outline of the thesis

The research presented in this thesis is comprised by five chapters and three appended papers.

In Chapter 1: Introduction, the background of the research area, the research problem highlighting the motivations for the study, the research purpose and the research questions are presented. This chapter ends with the scope and limitations of the thesis, followed by the thesis outline.

In Chapter 2: Theoretical framework, the frame of reference around the two principal topics of this research is introduced. First, it elaborates on the connection between sustainability development and manufacturing. Then, definitions and previous studies about sustainability principles and, more specifically, sustainable manufacturing principles, are presented. This is followed by the introduction of the definition and previous studies relating to sustainable manufacturing practices.

In Chapter 3: Research methods, the research design and the research methods are outlined. This is followed by describing the data collection

9

tools, data analysis, and final considerations about the quality of the research.

In Chapter 4: Summary of the results, the main theoretical and empirical findings from the appended papers with regard to the research questions are described.

In Chapter 5: Discussions and conclusions, the findings presented in the previous chapter are discussed the light of previous research. This is followed by a discussion regarding the methods used. Thereafter, the main conclusions are drawn, where the research questions are answered. The chapter ends by suggesting future studies.

Regarding the three appended papers, Paper I identified research trends from existing empirical studies of sustainable manufacturing, thus presenting a brief view of the current status of published research. Paper II described an overview of how current manufacturing operations, specifically sustainable manufacturing practices, adhere to sustainable production principles. Thus, this connects conceptual sustainable production principles with the sustainable practices reflecting these principles. Finally, Paper III explored the challenges and enablers for implementing sustainable manufacturing in surface treatment SMEs. Thus, insights regarding the needed sustainable manufacturing practices for facing sector specific challenges were extracted from Paper III and presented in this kappa.

11

CHAPTER 2

Frame of reference

This section presents the theoretical foundation for this research. It is divided into two main blocks: sustainable manufacturing principles and sustainable manufacturing practices.

2.1 Sustainable development and manufacturing

Sustainable development was first defined in “Our common future”, better known as the Brundtland Report (1987). The concept, which is still being used by the European commission, was defined as “meeting the present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland, 1987, p.15). In regard to this, Brookfield (1987) stated that this environmental report presented a novel focus on the politicization of environmental problems and its connection with social problems such as poverty and inequality. In the same sense, from an enterprise perspective, Elkington (1998) created the triple bottom line concept, stating that organizations looking to achieve sustainable development needed to work on three pillars or dimensions (the triple bottom line): environment or planet, social or people, and economics or profit. However, despite this definition of sustainable development, there is still limited consensus among scholars on the definition of sustainability (Berns et al., 2009).

Based on the definition of sustainable development, the concept of sustainable manufacturing emerged. This term was first mentioned in 1992 during the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development – UNCED. Later, De Ron (1998) defined sustainable production as an industrial activity that generates products which meet the needs and wishes of the present society without sacrificing the ability of future societies to meet their needs and wishes. Alongside De Ron´s definition, the Lowell Center for Sustainable Production – LCSP, University of Massachusetts, Lowell – defined sustainable production as: “The creation of goods and services using processes and systems that are non-polluting; conserving of energy and natural resources; economically viable; safe and healthful for employees, communities and consumers; and socially and creatively rewarding for all working people.” (Veleva and Ellenbecker, 2001, p. 520).

12

In a similar way, Garetti and Taisch (2012, p.85) defined sustainable manufacturing as “the ability to smartly use natural resources for manufacturing, by creating products and solutions that, thanks to new technology, regulatory measures and coherent social behaviours, are able to satisfy economic, environmental and social objectives, thus preserving the environment, while continuing to improve the quality of human life”.

For many years, large enterprises have made up the visible tip of the iceberg of contributors to global anthropogenic impacts on sustainability. These type of organizations are commonly acknowledged as the usual sources of such impacts resulting from manufacturing operations. On the other hand, SMEs have not been in the spotlight in the ongoing global debate regarding the adoption of sustainable manufacturing. Studies presenting sustainable manufacturing practices seem not to reflect the responsibility of all companies to mitigate or eliminate the negative effects of non-sustainability, as scientific research is still heavily focused on large manufacturers.

2.2 Sustainability principles

According to the dictionary definition, the term “principles” refers to a fixed or predetermined set of policies, ways of action or conducts. For Glavič and Lukman (2007, p.1876), principles “are fundamental concepts that serve as a basis for actions, and as an essential framework for the establishment of a more complex system”. For Shrivastava and Berger (p.248, 2010), principles constitute “sets of values, standards, guidelines or rules of behavior that describe the responsibilities of or proper practices for organizations”. These are some of the many definitions where the term “principles” alludes to guidance for further work. Similarly, principles have been defined as “the key concepts that serve as a basis for action” (Roberts and Ball, p.163, 2014).

One of the first attempts made to publish sustainable principles was by Daly (1990). He defined sustainability principles at a high level with a general approach. Some of the principles proposed by him were: 1) for renewable sources management, the harvesting rates should equal regeneration rates (sustained yield) and waste emission rates should equal the natural assimilative capacities of the ecosystems; 2) the sustainable use of non-renewable sources requires the investment in the exploitation of these type of resources being paired with an equivalent investment in a renewable substitute (e.g. oil extraction paired with tree planting for wood alcohol); 3) technologies that increase resource productivity (i.e. the amount of value extracted per unit of resource) must be prioritized, instead

13

of those technologies that focus on increasing the resource throughput (Daly, 1990). Two years later, these basic principles were refined and published by Costanza and Dali (1992).

In addition to these attempts at defining sustainability principles, governments in various countries have tried to establish their own sustainable development principles (e.g. The Government of Western Australia, 2004). The establishment of these sustainability principles at a higher level have shaped the way governments, industries and communities approach sustainability. This, as principles are usually introduced into a country’s legislation, forming a starting point for defining governance strategies or public policy (Government of Western Australia, 2004).

Among other studies that reviewed existing sustainability principles, Shrivastava and Berger (2010) worked on organizing the information published about main agreements concerning environment and development problems from 1968 until 2009. According to the authors, the agreements (e.g. the International Conference on Environment and Economics (OECD), Kyoto protocol), had the potential to spawn general sustainability principles, represented as “articulated desired changes” for governments, corporations, financial institutions, and individuals. The study also reviewed industry-specific sustainability principles proposed by several industry associations and national and international institutions. According to Shrivastava and Berger (2010), an increasing number of industries have been realizing that sustainability principles are needed as a guide to operate in the new economy, nevertheless little data published on adoption of these principles.

The principles mentioned above mostly covered defining policies and programs regarding sustainability, falling short when it came to applying these principles to the shop floor, or translating them into an actual transformation process.

2.3 Sustainable manufacturing principles

From an organizational perspective, Shrivastava and Berger (2010) defined sustainability principles as a set of basic criteria aimed at mitigating the impact of operations on the triple bottom line. Thus, sustainability principles deal with “moving organizations toward sustainability by changing their vision/mission, their use of natural and human resources, their production and energy practices, and their products and waste management” (Shrivastava and Berger, p.249. 2010).

14

Among the first attempts at establishing a set of sustainable principles from an operative perspective, Gladwin et al. (1995) presented a set of eight operational principles and their associated techniques of sustainable behavior.

Similarly, Veleva and Ellenbecker (2001) introduced a set of principles linked to corresponding indicators, framed under the concept of sustainable production as defined by the Lowell Center for Sustainable Production. This set of sustainable production principles are based on the following six main aspects that organizations need to tackle in order to make their operations more sustainable: energy and material use, natural environment, social justice and community development, economic performance, workers, and products.

Later, Al-Yousfi (2004) introduced four general principles that organizations implementing clean production approaches had to follow: 1) minimize the use of non-renewable resources; 2) manage renewable resources to ensure sustainability; 3) reduce or eliminate, hazardous/toxic and harmful emissions or waste into the environment; 4) achieve these goals in the most cost-effective manner, emphasizing sustainable development. Nevertheless, this set of sustainability principles was strictly focused on the environmental dimension of sustainability.

Similarly, Tsoulfas and Pappis (2005) described a set of twenty-six environmental sustainability principles with the purpose of guiding the operation and design of green supply chains; however, many of these principles were applicable to the production process. In contrast to the principles described by other authors, this structure was exclusively based on the environmental dimension.

Lindsey (2010) presented a set of three sustainability principles applicable to all segments of society and to all disciplines. These principles were posed with the aim of developing and implementing improved systems.

Finally, Despeisse et al. (2012) defined sustainability principles as a series of “rules”, usually followed by sustainable manufacturing initiatives or practices. The principles presented by these authors focused exclusively on environmental sustainable manufacturing principles.

Most scholars still use the term “sustainability” in “sustainability principles” to refer exclusively to environmental concerns. Indeed, the majority of studies addressing sustainability principles have only described environmental sustainability principles.

Thus, in light of the existing definitions of sustainability principles and considering the above mentioned examples of principles, for the purpose of this research sustainable manufacturing principles are defined as a set of criteria or guidelines to be followed by manufacturing companies in

15

order to translate a sustainable development policy into the operations required in the transformation processes, with the purpose of improving the environmental, social and economic performance of a company.

2.3.1 LCSP

Sustainable production principles

In order to study the empirical adherence by manufacturers to the sustainable manufacturing principles, this research used, as its guiding criteria, the LCSP principles of sustainable production, which adopt a triple bottom line approach and reflect the six main aspects of sustainable production (the LCSP principles were briefly introduced in section 2.3 of this thesis, and are further described in section 4.1). However, although these principles were created to promote a better understanding for companies about what sustainable production actually is, to date there is no scientific literature describing empirical testing of the LCSP principles. Paper II focuses on the sustainability principles from an operative perspective, filling the gap in current literature regarding how manufacturing companies translate sustainability into operative actions.

The LCSP principles can be described as follows: referring to sustainable products, Principle 1 concerns practice such as product design, product efficiency, long-lasting and easily recycled products, and environmentally-friendly and user-friendly product characteristics. Regarding energy and materials, Principle 3 involves energy reduction, non-renewable resources, water and materials consumption and safe material usage for the environment, workers and customers. On the natural environment, Principle 2 addresses reduction or elimination of waste. Principle 4 focuses on hazardous emissions to air and water, hazardous physical agents, technologies or work practices and the use of hazardous substances.

Principles 5, 7 and 8 mostly address aspects relating to workers. Principle 5 mainly deals with the reduction of the risks that workers are exposed to. Principle 7 concerns practices that aim to increase employee efficiency, employee’s improvement suggestions, employee creativity, and reward systems. Principle 8 covers practices that provide opportunities for employee advancement, safety and wellbeing, job satisfaction, training, gender equality, and turnover rate reduction.

Finally, regarding economic performance, Principle 6 encompasses practices aimed at reducing environmental health and safety compliance costs, improving participatory management style, promoting stakeholder involvement in decision-making, and increasing customer satisfaction; all these have the purpose of ensuring company profitability. Referring to community development, Principle 9 deals with increasing employment

16

opportunities for locals, developing community-company partnerships, and increasing community spending and charitable contributions to local communities.

2.4 Sustainable manufacturing practices

According to Shrivastava and Berger (2010), due to the theoretical or abstract nature of the sustainability principles, practices are originated. Currently, an increasing number of organizations are integrating sustainable practices into their manufacturing operations in order to improve not only their environmental performance but also their social and economic performances.

In scientific literature, often sustainable manufacturing practices are presented centered on the concept of resource productivity, which advocates higher resource efficiency as a means of waste reduction (Lazlo et al., 2013). Thus, sustainable manufacturing practices have mostly been defined from an environmental perspective. Reflecting this, Nordin et al. (2014) viewed sustainable manufacturing practices as aiming to minimize the impacts of manufacturing operations on the environment while optimizing the production efficiency of the company. Taking this definition as a departure point, and considering also the definition of sustainable development (Brundtland, 1987), for the purpose of this thesis sustainable manufacturing practices are defined as the actions, initiatives and techniques that positively affect the environmental, social or economic performance of a firm, helping to control or mitigate the impacts of the firm’s operations on the triple bottom line.

It is worth mentioning that, before the term sustainability was coined, Bowen (1953) introduced the concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR). For Bowen, CSR represented an obligation for companies to take responsibility for the impact of their activities on human, social, ethical and ecological environment over the course of their business activities. Hence, CSR came to be considered as the introduction and implementation of sustainable development within the sphere of management (Kechiche and Soparnot, 2012). Likewise, Perez-Batrez et al. (2010, pp 193) stated that the CSR concept includes the term sustainability. Whilst similar, CSR and sustainability are not identical. Both are voluntary corporate acts which can have different purposes and outcomes. All the sustainability initiatives can be labeled as CSR initiatives, but some CSR initiatives cannot be directly related to sustainability. Conscious of the difference between the two terms, this research focused on sustainability, as CSR is a broader field that is related to policies and practices from a

17

strategic or business level, while sustainability alludes to practices from an operational level that directly address manufacturing.

The growing importance of sustainable manufacturing over the years has led to an increased interest in the study of sustainability practices. Researchers (e.g. Millar and Russell, 2011; Hurreeram et al., 2014; Habidin et al., 2015) have studied sustainable manufacturing practices within different industry sectors and countries. Nevertheless, the vast majority of studies on sustainability practices have tackled mainly environmental practices, as well as the effects of sustainability practices on company performance, and sustainability practices among countries and sectors (e.g. Montabon et al., 2007; Despeisse et al., 2012; Schoenherr and Talluri, 2013).

The main drivers for undertaking sustainable business practices are both external (government regulations, profit and not-for-profit organizations) and internal pressures (strategic objectives, top management vision, employee safety and wellbeing, cost savings, productivity and quality) (Gunasekaran and Spalanzani, 2012).

Previous studies of sustainable manufacturing practices have described recycling, proactive waste reduction, remanufacturing, environmental design, and market research into environmental issues as the environmental sustainability practices that most strongly affect company performance (Montabon et al., 2007). Similarly, Hurreeram et al. (2014) determined that the most common environmental sustainability practices among large companies were eco-design, renewable energy usage, energy and material optimization, recycling, product life cycle and end of life cycle management, and waste minimization.

19

CHAPTER 3

Research methods

This chapter starts by describing the research design, and research methods used to achieve the research purpose. Then the description of the data collection, data analysis and insights regarding the quality of the research are presented.

3.1 Research design

Once the research problem is defined, the next stage is usually to plan the research design. The research design aims to describe the methodological decisions taken in regard to the research study. This includes aspects concerning data such as “what” to research, “where” to collect the data, by what means the data are gathered and how the data are analyzed (Kothari, 2004). The purpose of this licentiate thesis was to contribute to the existing body of knowledge regarding sustainable manufacturing principles and practices. In order to fulfill this purpose, three research questions of an exploratory nature were raised. Thus, at the initial stage of this thesis, an exploratory study approach to sustainable manufacturing principles and sustainable manufacturing practices was deemed appropriate to gain familiarity with these two subjects, and also to acquire new insights into them (Kothari, 2004). This agreed with Voss et al. (2002), who stated that exploratory research is mostly used during the early stages of a study in order to contribute to the identification of potential research questions of interest.

The first research question (RQ1) was intended to increase the understanding of the underlying concepts that can be used as a basis for the sustainable manufacturing practices in manufacturing organizations. Therefore, it aimed to identify the sustainability principles that could be potentially implemented within a manufacturing context. In this kappa, the frame of reference, section 4,1 and Paper II contributed to answer the RQ1.

The second research question (RQ2) explored sustainable manufacturing practices in order to identify the main sustainability aspects those practices respond to. Information regarding sustainable manufacturing practices was gathered from literature and empirically. Therefore, Papers I, II and III build upon each other, forming the basis of an answer to RQ2. Paper I explored sustainable manufacturing practices

20

in published empirical studies. The work described in Paper II added to this research question by presenting current sustainable manufacturing practices commonly carried out within the manufacturing industry. The work described in Paper III partially or indirectly answered this question by presenting the perceived sustainable practices needed to overcome sector-specific challenges for adopting sustainable manufacturing. Hence, Paper III provides insights about the lack of sustainability practices. Papers I, II and III answer this research question by clarifying the main sustainability aspects being addressed though sustainability practices among manufacturers.

The third research question (RQ3) studied how manufacturers’ operations, through their sustainable manufacturing practices, adhere to sustainable manufacturing principles. This research question adds to the general discourse on how industry adopts principles of sustainability and applies them in practice. RQ3 tries to fill the gap in current literature regarding the connection between conceptual sustainable production principles taking a bottom line approach and the sustainable manufacturing practices reflecting these principles. Paper II presents more details to fully answer this research question. Figure 1 shows a graphic representation of how the appended papers, and specific sections of this kappa, contributed to answer the research questions and the research purpose.

Figure 1. Research questions in relation to the research purpose.

Sustainable manufacturing principles Sustainable manufacturing practices Adherence of sustainable manufacturing practices to sustainable Rese arc h p u rp ose Paper I Paper II Paper III Frame of reference and section 4.1 Paper II Paper II RQ3 RQ2 RQ1

21

3.2 Research methods

Considering that the area of sustainable manufacturing practices is still in its infancy, and few empirical studies have been carried out on this topic involving all types of organizations regardless of their organizational size, an exploratory type of research was suitable for this research. Exploratory approaches are often used during the early stages of researching a phenomenon when looking for insights into a specific problem.

The choice of the research method also depends to a large extent on the form of the research questions (i.e. “what”, “how”, “where” and “why” types of questions) (Yin, 2009). In this research, the first and second research questions address the study problem using a “what” type of question to identify the sustainable manufacturing principles and practices. Similarly, the third research question was framed as a “how” type of question, also implying an exploratory approach.

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the three appended and the non-appended work-in-process papers (WIP) in relation to the research methods used, which helped to contribute to answer the three research questions.

The survey character of the research was appropriate for exploring the sustainable manufacturing practices and principles as the survey methods often involves the use of multiple data collection tools (Kerry, 2002), implying at the same time the collection of data from individuals about them or the social institutions they are part of (Rossi et al., 1983).

3.3 Data collection

The research presented in this thesis used, as its main data collection tools for collecting empirical qualitative data, interviews, focus groups and direct observations (Hancock, 1998). The other way of classifying the data collection tools is by the sources of the data, that is, primary and secondary (Kothari, 2004). Table 1 shows that the data collection tools used in this research were literature reviews (for obtaining secondary data), and semi-structured interviews, direct observations, focus groups and online questionnaires (for obtaining primary data).

22

Table 1. Overview of the research methods used

Paper Paper 1 WIP paper Paper 2 Paper 3

Research method(s) Systematic literature review Literature review Semi-structured interview Focus group and online questionnaire Purpose Inquire on sustainable manufacturing practices in published empirical papers Explore the existing sustainability principles Explore adherence to sustainable production principles by sustainable manufacturing practices Enhance the understanding of the adoption of sustainable manufacturing Research question RQ2 RQ1 RQ1, RQ2 and RQ3 RQ2 (indirectly) Analysis Published empirical

studies on sustainable manufacturing practices Published studies on sustainability principles Sustainable manufacturing practices adhering to sustainable production principles Challenges and enablers1 for adopting sustainable manufacturing in surface treatment SMEs Type of

study Exploratory Exploratory Exploratory Exploratory

Data collection Empirical journal papers Papers on sustainability principles Semi-structured interviews, factory visit insights and observations Focus groups and online questionnaire Data

analysis Content analysis

Content analysis Content analysis Content analysis

1The term enabler in Paper III is interpreted and referred to in this thesis as perceived

practices needed to overcome sector-specific challenges for implementing sustainable manufacturing.

23

3.3.1 Paper I

In order to explore the main topics of this research, sustainability manufacturing principles and sustainable manufacturing practices, both traditional and systematic literature reviews were used. A literature review was used in Paper I, to obtain a greater subject knowledge and awareness of how to frame and scope the research by giving an insightful overview of the current state of the study field (Croom, 2009). Knowledge of sustainable manufacturing principles and practices is crucial in the initial stages of licentiate studies. In this sense, a systematic literature review was used to explore the topic (Jesson et al., 2012), while allowing the identification of research gaps, trends and therefore the identification of further studies (Petticrew and Roberts, 2006; Torgersson, 2003).

The systematic literature review carried out in Paper I sought to identify empirical studies and practical initiatives carried out by manufacturing companies. The bibliographic search identified 2897 preliminary papers that were screened for eligibility according to these pre-established inclusion criteria: (i) they had an empirical approach to sustainability within manufacturing companies; (ii) they were published in a peer-reviewed journal between 2000 and 2013, (iii) they were written in English, and (iv) they were carried out within manufacturing industries (assembled products or industrial processes). Empirical papers from process industries were included because this type of industry is closely linked to many discrete manufacturing industries. Additionally, and because the study focus was the transformation process (or production function) within companies, papers dealing with other organizational processes out of this scope were excluded. Thus, papers dealing with topics such as eco-design, end of life product recovery, product-service systems, eco-innovation, sustainable consumption, and remanufacturing were excluded from the sample. After applying the inclusion criteria, the sample consisted of 80 papers; however, after full-text screening was carried out, the final sample was reduced to 25 papers. Thus, the systematic literature review used in Paper I provided a structured and transparent means of gathering, synthesizing and appraising the findings of studies aimed at minimizing the bias inherent in non-systematic reviews (Sweet and Moynihan, 2007). Finally, and in order to extract and organize relevant data from the final sample of journal papers, a matrix sheet in Microsoft Excel was created. The matrix contained key data summarizing each paper (e.g. title, country, year of publication, journal, author, research method, topic, industry, sustainability issue addressed in this dimension and key findings).

24

3.3.1 WIP paper

The WIP paper sought to gain knowledge about sustainability principles applicable to manufacturing perspective. In order to attain this, a literature review was carried out.

A bibliographic search was done in the citation database Scopus, using the keywords “sustainable manufacturing principles” and “sustainability principles” identified 289 papers. The final sample was constituted by six papers. Some of the reasons for paper exclusion were: duplicated papers, unobtainable full text papers, and papers where sustainability principles were not the main research focus. The papers that dealt with principles and had the higher number of citations were selected for further analysis.

The sustainability principles were extracted and organized in a matrix sheet in Microsoft Excel. The identified set of principles were grouped under the three dimensions of sustainability.

3.3.2 Paper II

Interviews were the main data collection tool used in Paper II. The interview was chosen as it provides important insights into the phenomena under study, helping to identify other relevant sources of evidence (Yin, 2009). A semi-structured interview was the specific type of interview used in Paper II, characterized by open-ended questions, and often used to collect information from individuals knowledgeable of the situation under study (Hancock, 1998).

An interview guide was designed, based on the principles of sustainable production defined by the LCSP, as well as its corresponding indicators for sustainable production (Veleva and Ellenbecker, 2001). The design of the interview guide was important, especially as semi-structured interviews require the interviewer to have previously identified a number of aspects to address (Hancock,1998). Twelve semi-structured interviews were carried out, within a sample of both large enterprises and SMEs from the following sectors: plastics, metalworking, foundry, engine manufacturers, hydraulic systems and furniture. The exploratory nature of the study made the use of a non-probabilistic purposive sample appropriate. Therefore, Paper II did not attempt to draw statistical generalizations from the results, but presented empirical evidence of adherence to the LCSP sustainable production principles through practices in the manufacturing sector. Respondents interviewed were environmental managers or managing directors. The data were collected by recording the interviews, and by taking handwritten notes. Table 2 shows an overview of the sample studied in Paper II.

25

Table 2. Paper II sample overview

*EM: environmental mmanager; EC: environmental ccoordinator; PM: production

manager; QSE: quality safety and environment manager

The semi-structured interviews were complemented when possible with direct observation (Ghauri and Gronhaug, 2010), carried out during plant tours provided by some of the companies. Direct observation has been used in many disciplines to collect data about processes, organizations, individuals and cultures (Kawulich, 2005). Likewise, direct observation was used in order to gather qualitative data in the form of written field notes about the respondent’s behavior (Papers II and III) and the organizations they belong to (Paper II). According to Dewalt and Dewalt (2002), when direct observation is combined with other data collection tools, the researcher is found to gain a better understanding of the context and phenomenon under study. Therefore, in this research, direct observation was combined with other data collection tools such as semi-structured interviews, an online questionnaire and focus groups.

3.3.3 Paper III

For Paper III, the data were collected using two collection data tools through two stages of empirical studies: focus group discussions and online questionnaire. Both collection data tools had CEOs as their main key respondents.

Focus group discussion is a well-known data collection tool (Morgan et al., 2008), used for gathering large amounts of qualitative data from a moderated interaction between a small group of approximately 6 to 12 individuals (Krueger, 1994; Morgan et al., 2008). A focus group was chosen for the research as it allows the exploration of a topic with little prior knowledge (Williamson, 2002), such as the perceived managerial perception regarding the challenges and enablers faced by SMEs for adopting sustainable production within surface treatment SMEs.

26

The focus group consisted of two groups of 10 CEOs each, where the discussions were moderated around a few planned questions and lasted 45 minutes each.

The focus group started with the moderator asking about the challenges of attaining environmental, social and economic sustainability within surface treatment SMEs. There were also questions regarding the perceived required practices or enablers that, if implemented, could be helpful in overcoming the sector-specific challenges of adopting sustainable manufacturing.

Regarding the sampling method, a non-probabilistic purposive sample involving CEOs from Swedish surface treatment SMEs was used. The CEO respondents in the sample were chosen based on contacts one of the researchers had with a professional association of surface treatment organizations. Keeping in mind that focus groups are concerned with people perceptions, and therefore it is advised they be carried out in a non-threatening environment (Krueger 1994, p.6), the discussions with CEOs were held in Swedish and in small groups in order to create an appropriate discussion environment where all opinions could be raised. It is worth mentioning that the choice of CEOs as participants in the focus groups was motivated by the holistic knowledge CEOs have of the three dimensions of sustainability within SMEs, knowledge usually lacking in other jobs such as environmental coordinator. In addition, the CEOs’ perceptions were valuable to the study as managers play an essential role in determining the environmental impact of their manufacturing operations through the different decisions they take (Klassen, 2000). The data were collected by recording the discussions and handwriting notes by the moderators. Further, the information gathered during the focus groups was used as input to design an online questionnaire; this increased the validity of the questionnaire as a measurement instrument.

For the second stage of the empirical data collection in Paper III, an online questionnaire was employed. This used a non-probabilistic purposive sample of SMEs’ CEOs in order to discover the perceived importance of the identified challenges and enablers from a broader audience of surface treatment SMEs. Based on this chosen sample technique, the results in Paper III provided an overview about the challenges and enablers identified by CEOs.

The online questionnaire was used as it allowed verification of the data gathered during the focus group stage, by identifying the perceived importance of the pre-identified challenges and enablers within a larger audience of SMEs’ CEOs. Regarding the design of the online questionnaire, Likert scales were used in order to determine the perceived importance of the challenges and enablers within CEOs. Once the