Making the inaccessible accessible - the oxymoron of

online luxury distribution

A qualitative study on consumer responses towards the distribution of luxury in

an online multibrand context

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration – Marketing NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAM OF STUDY: Civilekonom

AUTHORS: Filip Jönne & Conrad Walz

TUTOR: Mart Ots

I

Master thesis within Business Administration

Title: Making the inaccessible accessible - the oxymoron of online luxury distribution Authors: Filip Jönne & Conrad Walz

Tutor: Mart Ots Date: 2020-05-18

Keywords: Luxury, Internet retailing, Online distribution, Brand alliance, Louis Vuitton, Amazon

Abstract

Background - Luxury companies have long been reluctant to adopt the internet as a mode of distribution. A luxury brand’s concept of exclusiveness is seemingly incompatible with the ubiquitous nature of the internet. Hence, many luxury brands are fearful that distributing their products on third-party online retail platforms might decrease the brands’ vital aura of luxury.

Purpose - The purpose of this study is to explore consumer perceptions, attitudes and purchase intention towards a luxury brand being distributed on an online multibrand marketplace. This research aims to fill the existing gap on the ambiguous nature of luxury branding and distribution in an online multibrand context.

Methodology - A qualitative approach including ten semi-structured interviews with Swedish millennials were conducted. A case study of a hypothetical brand alliance between Louis Vuitton and Amazon was developed, presented and discussed. Collected data was analyzed through thematic analysis.

Findings - Results show that the online distribution of a luxury brand did influence consumer perceptions of the luxury brand when seen online. However, it did not result in a change in their overall attitude or purchase intention towards the luxury brand. Additionally, it was found that consumers were not willing to buy luxury on an multibrand marketplace platform.

II

Acknowledgments

We want to express our sincerest gratitude to those who have been part of the development and completion of this thesis.

First of all, we would like to thank our tutor Mart Ots for his guidance and invaluable advice throughout this thesis process. We are deeply appreciative to have been under his supervision and for his knowledgeable feedback, which has aided us during this time. We would also like to thank all other faculty members and fellow students who have provided us with counsel and constructive criticisms throughout the course of this paper.

Secondly, we want to acknowledge all participants that took part in this study. We are forever thankful for your participation and the insights you provided us with.

Lastly, we would like to give a special thanks to family members and friends who have been by our side and provided support throughout the course of this thesis process.

Filip Jönne Conrad Walz

Jönköping International Business School 18th of May 2020

III Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ... 1 1.1.BACKGROUND ... 1 1.2PROBLEM STATEMENT ... 2 1.3PURPOSE ... 4 1.4RESEARCH QUESTION ... 4 1.5DELIMITATIONS ... 6

2 THEORETICAL FRAME OF REFERENCE ... 7

2.1THE CONCEPT OF BRANDING ... 7

2.2BRAND IMAGE ... 7

2.2.1 Brand congruence ... 9

2.3 The luxury brand ... 9

2.4RETAILER STORE IMAGE ... 10

2.5INTERNET AS A DISTRIBUTION CHANNEL FOR LUXURY GOODS ... 12

2.6BRAND ALLIANCES AND BRAND SPILLOVER EFFECTS ... 13

2.7ONLINE BEHAVIOR OF LUXURY CONSUMERS ... 15

3. METHODOLOGY ... 18

3.1RESEARCH PHILOSOPHY ... 18

3.2RESEARCH DESIGN ... 18

3.3RESEARCH APPROACH ... 19

3.4RESEARCH STRATEGY ... 20

3.4.1 Case study selection ... 21

3.4.2 Interview strategy ... 23 3.5DATA COLLECTION ... 25 3.5.1 Sampling technique ... 25 3.5.2 Interview guide ... 27 3.5.3 Interview design ... 29 3.6DATA ANALYSIS ... 31 3.7QUALITY OF DATA ... 32 3.7.1 Data integrity ... 32

3.7.2 Reflexivity and subjectivity ... 33

IV

4. FINDINGS ... 34

4.1CONGRUENT LUXURY PERCEPTIONS TOWARDS LOUIS VUITTON AS A BRAND ... 34

4.2LUXURY ON A MONOBRAND WEBSITE IS LESS BUT STILL LUXURIOUS... 36

4.3MIXED USAGE OF MONOBRAND AND MULTIBRAND ONLINE STORES ... 38

4.4UBIQUITOUS PERCEPTIONS TOWARDS AMAZON’S MARKETPLACE ... 39

4.5THE BRAND ALLIANCE IS PERCEIVED AS INCONGRUENT ... 40

4.6AMAZON REDUCES LUXURY AURA OF LOUIS VUITTON ... 41

4.7LOUIS VUITTON ELEVATES AMAZON ... 43

4.8UNEVEN CHANGES IN ATTITUDES AND PURCHASE INTENTION TOWARDS THE BRANDS ... 44

5. ANALYSIS ... 46

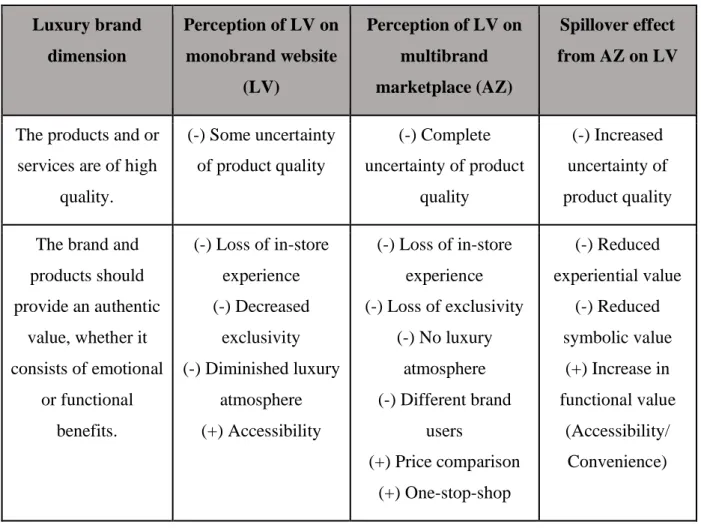

5.1CONGRUENT LUXURY PERCEPTIONS TOWARDS LOUIS VUITTON’S BRAND ... 46

5.2LUXURY ON A MONOBRAND WEBSITE IS LESS BUT STILL LUXURIOUS... 46

5.3MIXED USAGE OF MONOBRAND AND MULTIBRAND ONLINE STORES ... 47

5.4UBIQUITOUS PERCEPTIONS TOWARDS AMAZON’S MARKETPLACE ... 48

5.5THE BRAND ALLIANCE IS PERCEIVED AS INCONGRUENT ... 48

5.6AMAZON REDUCES LUXURY AURA OF LOUIS VUITTON ... 49

5.7LOUIS VUITTON ELEVATES AMAZON ... 52

5.8UNEVEN CHANGES IN ATTITUDES AND PURCHASE INTENTION TOWARDS THE BRANDS ... 53

6. CONCLUSION & DISCUSSION ... 55

6.1CONCLUSION ... 55

6.2THEORETICAL AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS ... 56

6.3ETHICAL AND SOCIETAL IMPLICATIONS ... 57

6.4LIMITATIONS ... 58 6.5FUTURE RESEARCH ... 59 7. REFERENCES ... 61 8. APPENDICES ... 69 8.1APPENDIX 1 ... 69 8.2APPENDIX 2 ... 71

1

1. Introduction

The following chapter will first introduce the background of the topic of distributing luxury brands in an online context. Thereafter, the identified problem is stated, and the purpose of the study is explained. This will be followed by introducing the research questions and the delimitations of this study.

1.1. Background

The retail industry has undergone tremendous change throughout the recent decade. The fast-paced industry of retail has moved beyond traditional brick-and-mortar stores and into the ever-changing universe of e-commerce. Retail’s fast adoption of the internet has been proven to successfully cater to the new shopping behaviors and preferences of the younger generations. Online multibrand fashion retailers (store carrying multiple brands) like Asos, Net-a-Porter and Farfetch are only a few prosperous examples of how digital business models are capable of outperforming traditional concepts of retail (Berridge, 2018). However, fashion’s migration online and its many opportunities does not come without challenges for varying companies. One sector that has been notably resistant to fully adopt e-retailing has been the one of luxury fashion (Kluge & Fassnacht, 2015).

Numerous luxury fashion brands have their own monoband webstore (stores carrying only one brand). Only a few brands have taken the step towards e-retailing through the use of multibrand online fashion retailers like Net-a-Porter, Farfetch and Yoox. However, no luxury fashion brand has fully embraced the realm of e-retailing and emerged themselves into major online marketplace platforms such as Amazon and Alibaba (Berridge, 2018).

Even though some luxury fashion brands has partially adopted e-commerce, many are still reluctant to make their products available on the world’s biggest e-marketplaces. According to Kestenbaum (2017), online marketplaces are intermediary web-based platforms which provides products from several companies. The marketplace itself is the mediator which provides the distribution of the goods. In contrast to a multibrand platform, an online marketplace possesses a broader product assortment strategy, containing products from several different product categories, markets and industries (Kestenbaum, 2017).

Luxury companies fear the possibility that their prestigious brand image will be damaged by the ubiquity and impersonal characteristics of the internet (Kapferer & Bastien, 2012). Using

2 the internet as a distribution channel for luxury brands could reduce its exclusivity and remove the treasured in-store customer experience that can be delivered in physical stores. Preserving a feeling of luxury and a cherished reputation is essential to the success of luxury brands. Therefore, many luxury brands are also fearful that the store image of third-party online retail destinations might influence, debase or remove the brand’s vital aura of luxury. This type of brand influence on another brand is often referred to as brand spillover effects (Berridge, 2018).

1.2 Problem statement

According to Dubois and Paternault (1995), the essence of distribution is to make products readily available for appropriate customers. Mass manufacturers often base their business on low prices and high intensity distribution tactics to meet the demand of many customers. Contrary, selective distributors, such as luxury companies, seek to restrict the accessibility of goods by utilizing high prices and limited production strategies in order to achieve high brand desirability (Dubois & Paternault, 1995; Fassnacht, Kluge & Mohr, 2013). Luxury brands need to be careful to not overexpose their brand as it might dilute brand desirability. Kapferer and Bastien (2012) argues that distribution can be used as a tool to create and maintain an image of scarcity. Furthermore, the perception of scarcity is said to be an essential factor for success for luxury brands (Brun & Castelli, 2013). Simultaneously, luxury companies are desirous to increase sales to new or existing customers through various combinations of old and new innovative distribution channels to ensure long-term growth (Keller, 2009).

Luxury companies face the dilemma between raising brand awareness and increasing sales while simultaneously keeping a high perceived brand luxuriousness. It is the paradox in making the inaccessible accessible that lies at the core of the online distribution challenge of luxury goods online (Kluge & Fassnacht, 2015). Therefore, academics and luxury managers have been reluctant to fully accept the internet as a mode of distribution due to its ubiquitous characteristics, making luxury goods available to almost to everyone - all the time (Kapferer & Bastien, 2012; Chevalier & Gutsatz, 2012).

The luxury brand environment online has changed over the years. 17 years ago, Riley and Lacroix (2003) argued that the opportunity of making purchases online from a luxury website had the least importance for luxury brands. More recent research has proven that there has been a substantial change in the last two decades. Abtan et al. (2016) identified that the possibility

3 of distributing and selling luxury goods online has become one of the most important aspect of luxury brand online strategy.

From a manager’s point-of-view, the internet creates another channel to achieve higher profits and sales by being able to reach out to more customers (Chevalier & Gutsatz, 2012). With the use of monobrand online stores, managers of luxury brands are able to control all market communication, the product catalogue, pricing and interactions with potential consumers (Quintavalle, 2012; Chevalier & Gutsatz, 2012). However, creating and maintaining an online distribution channel necessitates capital together with technological and logistical know-how. It might also cannibalize other sales channels. Additionally, an online presence come with increased transparency which can facilitate price wars and the production of counterfeits based on the information provided on the site (Kluge & Fassnacht, 2015; Kapferer & Bastien, 2012; Gastaldi, 2012).

From a customer’s point-of-view, the ability to access luxury products online, at any time of the day, enhances their feelings of shopping convenience compared to the shopping experienced in an in-store context (Okonkwo, 2009). It has also been argued that the consumers of luxury appreciate the accessibility and greater assortment of goods that is a result of the online channels, along with the familiarity of shopping from their homes (Quintavalle, 2012; Liu, Burns & Hou, 2013). However, the possibility of feeling, touching and smelling the products that is considered for purchase is absent in an online context, which has been proven to be an important dimension in the market for luxury goods (Okonkwo, 2009; Kapferer & Bastien, 2012). Apart from that, issues also include the perceived risk and security measures regarding online transactions and the delivery of such valuable goods (Wu, Chen & Chaney, 2013; Liu et al., 2013).

Previous studies have empirically explored motivations dictating luxury consumers’ shopping behavior online (Liu et al., 2013; Riley & Lacroix, 2003; Wiedmann, Hennigs & Siebels, 2009) and the design of luxury brand websites (Kluge, Königsfeld, Fassnacht & Mitschke, 2013; Riley & Lacroix, 2003; Seringhaus, 2005). Brand alliances and spillover effects between brands and retailers has also been extensively studied (Park, Milberg & Lawson, 1991; Simonin & Ruth, 1998; Nabec, Pras & Laurent, 2016). However, no academic research has empirically researched how consumers perceive potential brand spillover effects between a luxury brand and the store image of an online multibrand marketplace distributor.

4 1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this study is to explore consumer perceptions, attitudes and purchase intention towards a luxury brand being distributed on an online multibrand marketplace. By empirically exploring consumer perceptions, attitudes and purchase intention towards a luxury brand in an online context, this research aims to fill the existing gap on the ambiguous nature of luxury branding and distribution in an online multibrand setting. Within academia, it has been called upon to conduct research on how consumers respond to making luxury goods available on multibrand online stores by using real-world examples (Kluge & Fassnacht, 2015), something this study can contribute with.

1.4 Research question

Luxury companies has struggled to fully consider and incorporate e-commerce into their marketing and branding strategies. Existing opinions on whether luxury companies should emerge themselves into e-commerce differ greatly. Kapferer & Bastien (2012) argue strongly against the incorporation of online elements in luxury brand strategy. Kapferer and Bastien have gone from being totally opposed to selling luxury products online towards a more generous, yet doubtful, approach by stating that “selling luxury products online is extremely dangerous” (Kapferer & Bastien, 2009; 2012). However, authors like Okonkwo (2007:2010) and Batat (2019) argue for the incorporation of digital and e-commerce elements in luxury branding strategies. Abtan et al. (2016) even argue that luxury companies have to divulge into e-retailing in order to stay competitive in today's fast changing fashion retail environment.

Many luxury companies have come a long way since their initial skepticism and unwillingness to enter the world of the internet. Today, many luxury companies have come to the realization that the internet possess tremendous potential and have thus carefully created their own online monobrand webstores. However, Deloitte’s (2017) report of the global powers of luxury goods found that 78% of all online luxury product purchases are bought on multibrand online retailers. Despite this fact, there are currently no luxury fashion brands present on Amazon, a world leading multibrand online marketplace. Luxury brand managers fear that the ubiquity of e-commerce and especially the image of certain online marketplaces might “spillover” and hurt their own brand image (Kluge & Fassnacht, 2015).

However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no academic research to support these specific claims. Therefore, the following research questions has been created:

5 RQ1: How do consumers perceive a luxury fashion brand image in a monobrand online context?

RQ2a: How does an online multibrand marketplace influence consumer perceptions towards a luxury brand?

RQ2b: How does a luxury brand image influence consumer perceptions towards an online multibrand marketplace?

RQ3: How do consumers perceive a luxury brand and an online marketplace brand after being exposed to a brand alliance between the parties in terms of their purchase intention?

The following illustration provides a visualization of the research questions and the context in which they will be studied. An explanation of the illustration can be found bellow.

RQ1 will research the perceptions towards Louis Vuitton’s brand image in the context of its own monobrand website. RQ2 will research the perceptions towards Louis Vuitton’s and Amazon’s image in the context of Amazon's multibrand marketplace and how they influence each other. RQ3 will research how a brand alliance between the brands influence consumers’ overall attitude and purchase intention towards Louis Vuitton in general, towards Louis Vuitton products on Amazon and finally towards products on Amazon.

6 1.5 Delimitations

This study seeks to explore if the distribution of a luxury brand on an online multibrand marketplace influence consumer perceptions, attitudes and purchase intention towards a luxury brand. This exploration is delimited to a case study involving a hypothetical brand alliance between two real-world brands, one being Louis Vuitton and the other being Amazon. Furthermore, this study is delimited to only explore perceptions, attitudes and purchase intentions from the perspective of Swedish millennials familiar with both brands included in the case study. Millennials are defined to be those born between 1982 and 1998 (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2017).

7 2 Theoretical frame of reference

This chapter will introduce the underlying literature used to understand the phenomena of online distribution of luxury brands. This includes key concepts such as luxury branding, store images, brand alliances and the online consumption of luxury goods.

2.1 The concept of branding

Throughout the last decades, branding has become a top management priority for many organizations as it has become widely accepted that a brand can be one of the most valuable assets a company can possess (Keller & Lehmann, 2006). However, there is little agreement within academia and the corporate world on what constitutes a brand and how it should be defined (Simões & Dibb, 2001). Definitions of a brand vary greatly, from simply being a symbol of differentiation to more complex definitions stating that brands are multidimensional constructs which can possess personalities. The complexity of branding is not limited to its definition, but also extends to its management. The dynamic state of brands and their relationship with consumers require careful planning and execution of a combination of strategies in order to create and maintain a successful brand (Simões & Dibb, 2001). Within the field of marketing research, one of the most prevalent takes on brand equity is the one interpreted from a consumer perspective (Cobb-Walgren, Ruble & Donthu, 1995). Keller (1993) states that the success of a brand is often judged by its customers and can be referred to as Customer-Based Brand Equity (CBBE). Kapferer (2012) concluded that a high brand equity mainly stems from three essential concepts: brand knowledge, differential effect and consumer response to marketing. Among other things, brands with high brand equity are usually associated with being able to demand higher price premiums, have a high percentage of market share and loyal customers (Keller, 1993). Consequently, successful brands with high CBBE can be seen to reap benefits such as a high profitability and an advantage over competitors (Keller & Lehmann 2003; Vázquez, Del Río & Iglesias, 2002).

2.2 Brand image

The concept of brand image has long been an area of interest for marketers, especially within the luxury industry, as much of the brand equity lie within its imagery (Keller, 2009). The image of a brand makes reference to how consumers perceive a brand (Nandan, 2005). In turn, the perceptions consumers possess of a brand is stated to be created during the process of interpreting the facets of brand identity (Roy & Banerjee, 2014). A commonly adopted definition of brand image is the one formulated by Keller (1993), who explained brand image

8 as “perceptions about a brand as reflected by the brand associations held in consumer memory”. In other words, a brand image is often the perceptions of a brand from consumers’ point of view (Nandan, 2005).

As a brand image is created when consumers decode company-projected brand cues, it seems appropriate to further explain this decoding process in more detail. According to Keller (1993), there are several different types of brand image associations that can occur when decoding a brand identity. These associations can be divided into three main categories: attributes, benefits and attitudes.

According to Keller (1993), brand attributes refers to consumers’ opinions about what features and characteristics a product or service possess and what role they play during purchase and consumption. Brand attributes can be separated in product and non-product related attributes depending on their level of contribution to product or service performance. Product related attributes are heavily dependent on product category and vary thereafter. Non-product related attributes are external influences that affect purchase and consumption behavior of consumers. Keller (1993) states that there are four central forms of non-product related attributes: price information, packaging or product appearance information, user imagery and usage imagery. Keller (1993) explains that price information is a fundamental part of a purchase but cannot be used as a predictor of product or service quality. Hence, the price of a product is to be considered as a nonproduct-related attribute. However, price information is a vital part of a brand’s image since consumers tend to organize products and brands in relation to each other depending on their product category, perceived value and overall price level. Likewise, packaging and product appearance information is an influencing factor and part of purchase decisions and consumption. Furthermore, Keller (1993) has found that how consumers perceive other users of a brand also affects a brand’s image. Such associations generally stem from demographic, psychographic and other factors. The timing of when a branded product or service is utilized is another important association making up a brands image, such as time of usage, the location of usage and type of activity carried out during usage. According to Keller (1993), user and usage attributes are cornerstones of a brand’s perceived personality.

Keller (1993) argues that brand benefits relates to the perceived personal value consumers derive from product or service attributes. These benefits can be differentiated into three categories depending on their underlying motivation. The three categories of brand benefits are

9 either functional, experiential or symbolic in nature. Functional benefits are usually linked to product-related attributes and originate from consumers’ motivation to fulfill basic biological needs and desires, like physical protection and problem avoidance. Feelings that arise when consumers use a product or service are referred to as experiential benefits. Experiential benefits are also connected to product-related attributes. However, experiential benefits satisfy other needs and desires like cognitive and sensory stimulation. Symbolic benefits are usually linked to non-product-related attributes of a product or service. Consumers’ derive symbolic benefits through consumption to satisfy their need for social approval and self-expression. Therefore, brands that are perceived as prestigious, exclusive or fashionable can be of more value to consumers as they might better align with their self-concept.

According to Keller (1993), brand attitudes refers to consumers’ overall evaluation of a brand. Brand attitudes are in turn linked to the aforementioned product and non-product-related attributes. Brand attitudes are especially important for a brand since they have been proven through the theory of planned behavior to be great predictors and drivers of consumer behavior (Ajzen, 1991).

2.2.1 Brand congruence

An important aspect of brand image is brand association congruence (Keller, 1993). Congruence among brand attributes, benefits and attitudes relates to the extent to which these associations carry a unified meaning. Brand image cohesiveness is important as they can form consumers’ general perceptions about a brand. Congruence among brand associations is especially important as a diffuse brand image, one with little or no association congruence, can create several unfavorable conditions. Incongruity could, for example, result in confusion in regard to the meaning of the brand and its values. It could also make new brand associations weaker, more short-lived and potentially less favorable compared to congruent ones. Furthermore, incongruent brand images are more likely to change as an effect of competitive action compared to cohesive brand images. This is because of the low interconnectivity between associations of incohesive brands (Keller, 1993).

2.3 The luxury brand

Just like the many definitions of a brand, there are numerous ways of defining a luxury brand. Although voluminous research has been made previously within the area, there is no universally

10 established definition of a luxury brand (Ko, Costello & Taylor, 2019). The reasons for the lack of consensus revolve around the relativity of luxury. Berthon, Pitt, Parent and Berthon (2009) argues that a major issue with determining one single definition is that luxury consists of more than a set of attributes or characteristics. Basically, it is impossible to claim that something is to be regarded as luxury by only observing the item at hand. One must also consider differences at a social and individual level. What might be perceived as luxury by one individual or culture might not be perceived in the same way by others. What is meant by luxury has also been found to fluctuate over time (Mortelmans, 2005; Cristini, Kauppinen-Räisänen & Kourdoughli, 2017).

Ko et al. (2019) conducted research which aimed at finding commonalities between definitions for luxury brands. The study depended heavily on previous research within the area and found that it is essentially the customer evaluations of a brand that determines its luxury status. Managers and boards of brands might invest heavy efforts on its brand identity and campaigns, but it is still the perception in the eye of the customer that decides if a brand is to be regarded as a luxury brand. Nevertheless, Ko et al. (2019) made the following conclusions about what dimensions consumers generally considers when distinguishing a luxury brand from a non-luxury brand:

1) The products and or services are of high quality.

2) The brand and products should provide an authentic value, whether it consists of emotional or functional benefits.

3) The brand has a distinguished and reputable image on the market through qualities including artistry, craft and quality of service.

4) The brand satisfies the criteria for demanding a price premium.

5) The brand is able to create a deep relationship and commitment to the customer.

Based on the findings made by Ko et al. (2019), this study will make use of a luxury brand which fits the dimensions described above.

2.4 Retailer store image

Just like consumers can create images of individual brands, they tend to form brand images of entire stores (Yun & Good, 2007). However, unlike brand images, store images are instead evaluated based on rather different characteristics compared to brand images (Kwon & Lennon, 2009). The exact dimensions making up the entirety of a store image is heavily case dependent.

11 Nonetheless, three types of store attributes have been identified to cover essential parts of consumer perceptions and overall attitude towards an offline store image. These are merchandise attributes, service attributes and store shopping atmosphere attributes (Yun & Good, 2007).

Merchandise attributes make reference to associations related to the products carried by the particular store (Yun & Good, 2007). Such associations often cover the quality of the products, depth and width of product assortment, product design and price levels. Service attributes include cover associations related to level of perceived service from store personnel and opportunity of self-service. It also includes associations to return policies and delivery services. Store shopping atmosphere attributes are stated to include consumers perceptions of the general shopping space, shopping convenience along with the pleasantness of shopping. Additionally, it is stated that the aforementioned attributes of store images can generate a multitude of functional and emotional benefits similar to those generated by brand images (Yun & Good, 2007).

Moreover, retailing’s transition from physical brick-and-mortar stores to online retail destinations has introduced new dimensions to the three previously identified attributes on which consumers base their perceptions and attitudes (Yun & Good, 2007). In contrast to offline store merchandise attributes, online merchandise attributes are heavily based on product information (textual and visual). The importance of product information is stated to be because the consumers are unable to physically examine the products. Online service attributes are different from offline mainly because the lack of personal interactions with store employees. Consequently, online service attributes are based on the perceived extent of provided information and how easily the information is found. It also includes customer-support, site search functions and price comparison. For online store shopping atmosphere, the most crucial component is a convenient website design in terms of product display, feel of site navigation and overall attractiveness (Yun & Good, 2007).

According to Merrilees and Miller (2001), strong store images are able to influence consumers in various ways. It was found that a strong store image could result in high store patronage intention, willingness to pay higher prices (price premiums) and consumer loyalty.

12 2.5 Internet as a distribution channel for luxury goods

As mentioned in the introduction, luxury brands have long been hesitant to completely embrace e-commerce because it has been believed that online retailing would weaken the brand’s luxury image and result in reduced brand desirability (Kapferer & Bastien, 2012). The perceived lack of control over important branding elements such as online shopping environment, pricing and customer service has further contributed to the belief that luxury has no place on the internet. Instead, luxury brands have been holding on to its traditional offline retail concept with a distinct focus on an exclusive shopping experience, under the assumption that luxury consumers would not be willing to pay a premium price for luxury products online (Kluge & Fassnacht, 2015).

However, during the past few years, this presumption has been contested by the success of multibrand online luxury retailers such as Farfetch and Yoox (Berridge, 2018). The success of these e-commerce businesses has proven that consumers are willing to purchase luxury goods online at the same price premiums as in offline stores. Furthermore, online sales of luxury goods have seen a steady increase over the last years. In 2018, online sales grew with 22% and now represents 10% of the total luxury market (Bain & Company, 2019).

According to Beauloye (2020), it is no longer viable for luxury companies to neglect the internet as a part of their omnichannel strategy. The expectations of the modern luxury consumers are changing, and luxury brands need to adapt and invest in an online presence, whether it be through a monobrand website or through a multibrand retailer. As the industry is starting to realize the potential of the internet as a mode of distribution, more and more luxury companies are adopting an omnichannel strategy (Beauloye, 2020).

The omnichannel strategy can be adopted either through the development of a fully owned website, through a third-party platform or a combination of both (Woodworth, 2019). The most common form of online luxury distribution is through the format of a monobrand websites. This type of distribution channel can be developed in-house but is most commonly outsourced as the luxury companies themselves often lack the required technological know-how. The monobrand website is stated to be used by luxury brands that are in the initial face of digital adoption where the website is mainly used for marketing purposes and as a sales point for entry-level luxury products (Woodworth, 2019).

13 Another less frequently used format of online luxury distribution is through third-party multibrand retailers (Woodworth, 2019). However, this mode of distribution has been proven more successful than monobrand distribution in terms of percentage of total online sales. According to research made by Deloitte (2017), multibrand retailers accounted for 78% of all online luxury sales. This represents a lack of online channel investments from many luxury brands (Deloitte, 2017). Further, Beauloye (2020) claims that luxury companies utilizing multibrand distribution channels are mostly limited to digitally born luxury brands that leverage these channels in combination with monobrand channels. Luxury brands that were initially introduced though the internet is therefore currently being described as role models for traditional luxury brands that are hesitant to diversify their online distribution strategy to incorporate the use of multibrand websites. One example of a traditional luxury brand that has been able to incorporate multibrand platforms into its online distribution strategy is Louis Vuitton (Beauloye, 2020).

Additionally, most of the online multibrand retailers of luxury goods are niche platforms that exclusively host luxury brands (Woodworth, 2019). Even though the multibrand approach to online luxury shopping has been proven successful, it has not yet reached the biggest multibrand marketplace retailers like Amazon or Alibaba (Danzinger, 2020). Throughout this thesis, online marketplaces are defined as intermediary web-based platforms which provides products from several companies (Kestenbaum, 2017). The marketplace itself is the mediator which provides the distribution of the goods. In contrast to a multibrand platform, an online marketplace possesses a broader product assortment strategy, containing products from several different product categories, markets and industries (Kestenbaum, 2017).

2.6 Brand alliances and brand spillover effects

Since this thesis explores the relationship between two brands, (1) an online marketplace brand and (2) a luxury brand, it is needed to explore previous research within the field of cooperative brand marketing. However, since there is a tremendous amount of research done within different subareas of cooperative brand marketing, we have chosen to restrict this literature review to focus on brand alliances and spillover effects of such alliances.

A study by Simonin and Ruth (1998) found that preexisting attitudes towards a brand alliance could have “spillover” effect on each of the brands entering the alliance. Further research on brand alliances has shown that consumers have expectations of how certain brands should be distributed and have preconceptions about how the products should be displayed when for sale

14 (Buchanan, Simmons & Bickart, 1999). Furthermore, it has been found that the perceived congruity or “fit” between consumers’ brand associations of the two brands could influence potential spillover effects. Arnett, Laverie & Wilcox (2010) has formally described the fit between brands as “the degree to which consumers perceive that the relationship is appropriate and logical”. According to Keller and Aaker (1992), consumers are more likely to question brand alliance between two brands if the alliance is perceived as incongruent. Additionally, the study by Simonin and Ruth (1998) found that brand familiarity was an important mediating factor influencing potential spillover effects between brands. It was found that brands with higher familiarity experiences less spillover effects from the partnering brand with lower familiarity, while the brand of lower familiarity experiences more spillover effect from the partnering brand with higher brand familiarity. According to Simonin and Ruth (1998), brand familiarity acts as a moderator of spillover effects in a way that can be explained by cognitive dissonance theory. The theory of cognitive dissonance suggest that consumers tend to accommodate new information in a way that creates the least cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957). For example, when an individual, who hold strong cognitions about a brand, is exposed to new incongruent brand information, he or she tends to eliminate the state of cognitive dissonance by rejecting or only partly accept the new information. However, when an individual hold weak cognitive association to a brand, they tend to experience less cognitive dissonance and hence be more susceptible to new and incongruent information (Simonin & Ruth, 1998).

Within brand alliance research, it has been shown that the alliance between two brands can provide a wide array of both positive and negative spillover effects. For example, a study by Park et al. (1991) indicated that a brand alliance can result in the benefit of overcoming incongruent or contradictory brand associations between two different brands. The study found that two brands could enter into an alliance to successfully implement products that were rich in taste but low in calories, two attributes that were perceived to be negatively correlated with each other. The study by Park et al. (1991) and its findings relates to the current study as a potential alliance between a luxury brand and an online marketplace could result in successfully overcoming incongruent associations such as of scarcity and mass appeal. However, a study by Nabec et al. (2016) found that if a selective fashion brand, that employ selective distribution tactics, where to be sold through an online mass retailer, consumers might reevaluate both brands due to the apparent contradiction between existing brand associations and the new information. On the one hand, Nabec et al. (2016) explains that a brand alliance between a

15 selective fashion brand and a mass online retailer’s brand could negatively affect the selective brand in terms of store image transfer, change in value perceptions and purchase intentions, potentially resulting in brand dilution. On the other hand, it has been found that a mass retailer's brand might experience an increase in its perceived status and in brand awareness, together with gaining similar intrinsic features as the allied selective brand. Hence, when an online mass retailer ally with a selective brand, it can result in new brand associations and image evaluations for both entities, for the better or for the worse (Nabec et al., 2016).

In this master thesis, a similar scenario will be studied to the one presented by Nabec et al. (2016). However, the two allied brands will include a luxury brand and an online multibrand marketplace. It can hence be argued that this study further examines the nature of brand alliances and potential spillover effects but in a scenario with increased brand association incongruity between the allied parties.

2.7 Online Behavior of Luxury Consumers

Okonkwo (2007) states that there are several differences between offline and online shopping and between non-luxury and luxury consumer behavior. One major difference is that the ordinary decision-making process of offline non-luxury goods often starts with recognizing a need followed by information search, a purchase, usage and product evaluations. However, with luxury goods, the purchase decision process is much controlled by irrational feelings and emotions. In an online context, these psychological elements play an increasingly important role for luxury goods.

In order to better understand luxury branding online, one must grasp underlying motivations and drivers behind luxury consumption. One of the most prominent theories within the field of luxury consumption is the theory of conspicuous consumption. Conspicuous consumption was first addressed in 1899 by Veblen in “the theory of the leisure class”. Veblen (1899) suggest that individuals consume luxury in order to demonstrate wealth, power and social status. Using the theory of conspicuous consumption, Bearden and Etzel (1982) discovered that publicly consumed luxury products were more frequently purchased for conspicuous reasons, compared to privately consumed luxury goods. Moreover, it has been identified that consumers perceive the value derived from luxury brand consumption in terms of its capacity to project a person's self-image (Hung, Chen, Peng, Hackley, Tiwsakul & Chou, 2011). Han, Nunes and Dreze (2010) found that the extended-self-concept can be used to account for symbolic values

16 consumers derive from the possession of luxury goods. These findings originate from the ideas presented by Belk (1988), which assume that individuals use possessions to create and modify their identity in relation to who they think they are and who they aspire to become. Furthermore, luxury brands have been found to be popular among uniqueness seeking consumers due to the brands special characteristic of being perceived as scarce and unattainable (Bian & Forsyth, 2012).

With the aforementioned drivers of luxury consumption in mind, Kapferer and Bastien (2012) argues that the online distribution of a luxury brand can reduce motivations to consume luxury as it diminishes the brands so-called “dream value”. Hence, the purchase motivation among luxury consumers can diminish as online distribution of luxury gives “non-qualified” individuals unwanted access to a brand that is intended for the few. This argument builds on the notion that the desirability of a luxury brand originates from a perception of scarcity and exclusivity. Thus, by making a luxury brand available on the internet, consumers’ feelings of scarcity and exclusivity might be reduced due to its ubiquitous characteristics.

Nevertheless, digitalization is becoming a stronger influencing factor for wealthy people’s purchasing decisions. It has been found that more than 40% of luxury purchases are somehow influenced by an online experience (Dauriz, Remy & Sandri, 2014). The online experience of luxury for consumers typically takes place when researching for a product or when seeking inspiration. This is mostly done through search engines and social media (Dauriz et al., 2014). Moreover, it has been found that one of the most prominent benefits contributing to online luxury shopping is increased access and feelings of convenience (Okonkwo, 2007). Being able to shop whenever one desires regardless of physical location is stated to be a driving factor behind the growing phenomena of online luxury shopping (Okonkwo, 2007).

According to Boston Consulting Group’s (2019) report on the development and trends of the global luxury market, there has been a steady increase of millennial luxury shoppers. In this report, the term millennials will include individuals that are born between 1982 and 1998, as suggested by the U.S. Department of Commerce (2017) in a report on the changing economics and demographics of young adults. The Millennial age cohort accounted for around 32% of the personal luxury market in 2017. By 2025, millennials are projected to increase its influence and account for approximately 50% of the market. Furthermore, global data reveals that millennials

17 have been found to make 42% of their luxury purchase through digital channels, compared to 36% of Generation X and only 28% of Baby boomers (Deloitte, 2017).

Furthermore, according to Okonkwo (2007), important factors for the increasing number of online luxury shoppers are the increasing trust in secure payment methods and electronic CRM-systems processing user accounts, deliveries, returns and complaints. These improvements have in turn resulted in consumers being more confident in spending vast amounts of money on online purchases (Okonkwo, 2007). However, one cannot take for granted that consumers favor online shopping over offline shopping. This is because online shopping can be considered as being riskier, especially for fashion products which requires a high involvement decision (Kwon & Lennon, 2009). However, the perceived risk related with online luxury shopping can be reduced when the shopper possesses high brand familiarity and favorable brand associations of the e-retailer and/or product brand (Kwon & Lennon, 2009).

18 3. Methodology

The following chapter will introduce the philosophical approach taken to conduct the research. Thereafter, the research design, research approach and research strategy will be presented with justifications of the chosen methods. How the data was acquired, analyzed and quality-assured is also described in this chapter.

3.1 Research Philosophy

The purpose of this study is to explore consumer perceptions, attitudes and purchase intention towards a luxury brand being distributed on an online multibrand marketplace. Therefore, the researchers have adopted the philosophical approach of interpretivism. According to Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill (2016), interpretivism suggest that reality is a social construct that is subjectively interpreted and assigned meaning by individuals. Hence, the purpose of interpretivist research is to discover new insights and to get a more in-depth understanding of the social world and its contexts by studying these meanings from a subjective perspective. This is in contrast with the purpose of a positivist approach, which seek to discover universal, generalizable, laws for certain phenomena (Saunders et al., 2016). An interpretivist approach implies that it will be possible to explore and obtain a deeper understanding of consumers’ perceptions and attitudes towards a brand alliance between a luxury brand and an online marketplace distribution brand. This is important since consumers’ perceptions and attitudes can be assumed to be of different subjective meaning. Hence, an interpretivist approach is deemed appropriate for the purpose of this study.

Moreover, the phenomenological variation of interpretivism will be applied in this thesis. Phenomenology put further emphasis on how variations in lived experiences influence individuals’ subjective reality and its assigned meaning. By focusing on lived experiences, one can obtain deep insights on how factors such as culture, upbringing and time era contribute to the creation of meaning (Saunders et al., 2016). The risk of applying a positivistic approach to exploratory research is that the rich nuances of the human experience tend to be overlooked and simplified into general behavior. Since this thesis focus on lived experiences of millennials, a phenomenological approach is most suitable.

3.2 Research Design

Based on the purpose of this thesis, an exploratory research design was adopted. This was due to the fact that exploratory research design is beneficial when one wants to obtain greater

19 knowledge about the nature of an issue, problem or phenomenon that is ambiguous (Saunders et al., 2016). In this thesis, the phenomena under investigation is the online distribution of a luxury brand in on an online marketplace. As mentioned in the literature review, there are multiple theoretical fields underpinning the nature of luxury brands, online store images, luxury consumption and brand alliances. On the one hand, it involves well researched areas such as the creation of brand and store images, motivations driving luxury shopping and potential spillover effects in brand alliances. On the other hand, there is the relatively unexplored field of how luxury brands are perceived when distributed in a multibrand marketplace environment.

After deciding upon the research design, the researchers evaluated which research method that would be the most appropriate. For the purpose of this study, a qualitative method was concluded to be the best choice. This is because a qualitative research method is beneficial for studies aiming at understanding behaviors, experiences and feelings (Malhotra, Birks & Wills, 2012). In this case, how a luxury brand is perceived in an online context. Qualitative data collection focus on capturing subjective meanings through words and observations, while quantitative methods focus on identifying universal laws by collecting numerical data (Saunders et al., 2016). Since there is a lack of existing research on luxury brands in an online context, the decision to pursue a qualitative method rest on the difficulty in capturing an unexplored phenomenon through the use of predetermined variables and numbers. Furthermore, a qualitative approach is congruent with the use of an interpretivist approach to research since qualitative data is better suited for exploring the complexities and differences between participants’ lived reality. Hence, further strengthening the argument for the chosen research design.

3.3 Research approach

When conducting research, one must decide on the best way to approach theory development. Grounded in the purpose of this thesis, it was decided to pursue an abductive approach to theory development. An abductive approach makes use of both inductive and deductive reasoning and is frequently applied in practice during business administration research (Saunders et al., 2016). Furthermore, an abductive approach is the course of action one can undertake when there is an abundance of information about a topic in one context but far less in the context in which the current research is to be carried out (Saunders et al., 2016). The topic of this thesis can be considered to match the scenario in which an abductive approach is seen as most suitable. This is because extensive literature exists on underlying concepts such as brand images, brand

20 alliances and luxury consumption. However, there is hardly any information regarding how consumers perceive a brand alliance between a luxury brand and a multibrand marketplace distributor. Hence, motivating the use of an abductive approach.

When approaching theory development abductively, the researchers often encounter something surprising that might speak against any previously existing knowledge (Saunders et al., 2016). It is then this surprising fact that the researchers aim to explain with the aid of previous literature or new empirical evidence (Saunders et al., 2016). For this particular study, the surprise originated from the realization that no luxury brand was present on the online marketplaces of Amazon, despite the fact that 78% of all luxury consumption online occurs on similar multibrand websites. Therefore, motivating the researchers to assess the justifiability of luxury brand’s fear of multibrand retailers by collecting further data regarding consumer perceptions and attitudes towards a luxury brand in an online marketplace context. Furthermore, the research approach of abduction presents the researchers with the possibility to apply old, suggest modifications to or present new theory (Saunders et al., 2016). This is wanted as answers provided by individuals might reveal information that is consistent, inconsistent or completely new in relation to existing research. Hence, an abductive approach can contribute to increased ability to discuss, analyze and apply the findings of this research.

3.4 Research strategy

According to Saunders et al. (2016), a research strategy is a description of the scope and process of how the researchers went about answering the study’s research question(s). For this thesis, this means that the research strategy should describe the strategy for collecting information with the aim of answering the following research questions:

RQ1: How do consumers perceive a luxury fashion brand image in a monobrand online context?

RQ2a: How does an online multibrand marketplace influence consumer perceptions towards a luxury brand?

RQ2b: How does a luxury brand image influence consumer perceptions towards an online multibrand marketplace?

RQ3: How do consumers perceive a luxury brand and an online marketplace brand after being exposed to a brand alliance between the parties in terms of their purchase intention?

21 Since the research questions seek to fulfill the purpose of this study, it was decided to employ a case study research strategy. A case study was adopted because it allows for interactions between a phenomenon and its context to be understood and studied in-depth (Dubois & Gadde, 2002). Furthermore, the case study strategy was chosen because it provides the researchers with the opportunity to study a situation within a real-life setting (Saunders et al., 2016). Real-world brands were selected for the sake of increased external validity (Kluge & Fassnacht, 2015). The two brands selected for the case study were Louis Vuitton and Amazon. The justification for these choices will be discussed below.

3.4.1 Case study selection Louis Vuitton

For the purpose of this study, Louis Vuitton was chosen as the example to represent a luxury brand. Louis Vuitton is a luxury brand that was founded in Paris, France in 1854. Famously known for their timeless design and focus on the art of travelling, the heritage of the Louis Vuitton brand has grown stronger ever since its founding days (“Louis Vuitton”, 2020). Today, the brand is one of the most well-known luxury brands in the world and is part of the LVMH luxury conglomerate, which had an annual turnover of over $60 billion dollars in 2019 (“Results for LVMH”, 2020). Currently Louis Vuitton’s products can be found in over 460 stores in more than 50 countries (Wendlandt, 2018). Furthermore, according to Okonkwo (2010), Louis Vuitton is one of the most prominent luxury brands online with a well-developed online presence. One can find the brand’s products available in their monobrand online web shop but also in various multibrand specialty online stores. Louis Vuitton is also present on various social platforms. On Instagram the brand has over 37 million followers (Louis Vuitton, 2020) and on Facebook the brand has over 23 million likes (Louis Vuitton, 2020). The above-mentioned facts prove the point that Louis Vuitton is a true luxury brand which focus on the incorporation of online elements in their branding and distribution strategies. Therefore, it is not farfetched to imagine that Louis Vuitton is considering embracing online marketplaces as a mean of distribution. Hence, making it a good example for the purpose of this study as the studied context is realistic.

Amazon

To best fit the purpose of this study, the e-retailer Amazon was chosen as an example of an online marketplace. Amazon was first founded in 1995 and initially focused on selling books over the internet (“Marketplaces Year in Review 2019”, 2020). Since then, the company has

22 grown tremendously and in 2018 Amazon generated over $277 billion in sales. Currently, Amazon is a platform hosting over three million sellers which together accounts for over 60% of total sales. The remaining 40% of sales is generated by selling their own products or by selling goods covered under special vendor agreements. In total, the online marketplace has around 120 million products up for sale. Amazon aim to target “everyone” by facilitating the connection between buyers and sellers across the globe (“Marketplaces Year in Review 2019”, 2020). By targeting “everyone” one could argue that Amazon is different from other multibrand websites discussed in this thesis as Amazon can be considered to be particularly unsegmented. By targeting everyone, Amazon are indirectly also targeting luxury consumers. Hence, being a great fit for this study. Amazon has yet to introduce a Swedish web-domain like Amazon.se. Nevertheless, Swedes have shown indications of having no problem of adopting European counterparts like amazon.co.uk, amazon.de and amazon.it. Furthermore, Swedes spend around SEK 1 billion annually through European Amazon-sites (“The rise and rise of Amazon”, 2019). Additionally, according to a report on European e-commerce

behavior by Postnord (2020), 65% of Swedes have purchased goods on e-marketplaces, of which almost 20% had made a purchase from a European Amazon-site (Postnord, 2020). These facts further strengthen the argument that swedes are familiar and frequent users and consumers of Amazon.

Product selection

The selected product that was displayed throughout the interviews was a Louis Vuitton branded toiletry kit. This specific product was chosen for this study due to four main reasons. Firstly, the product was chosen because it was deemed to represent the brand of Louis Vuitton in an appropriate way. This because of the brand’s heritage of selling quality leather goods. It was also chosen because it was similar in look to their well-known handbags with a distinct color combination and visible logo to ensure recognizability. Secondly, the product is an accessory. An accessory was chosen since accessories has been shown to be the most popular category of luxury goods being sold online. According to Bain & Company (2019), accessories accounted for 42% of all luxury sales online, where the second most sold category (apparel) accounted for 27%. Hence, by using an accessory, the researchers can ensure a high probability that the product selected is suitable for being sold online, and thus also for this specific research. Thirdly, the researchers deemed it important to choose a product that was as gender neutral as possible since no gender was excluded in the research. By using a product that was likely to appeal to all genders, it was possible to use the same illustrations in all interviewees. This, in

23 turn, allows for comparing responses from different genders which otherwise would not be possible if gender-specific products were used. Lastly, it was desired to choose a product that could be both publicly and privately consumed. Even though a toiletry kit can be considered to be consumed mostly privately, this particular product is often also seen to be used in public. Such occasions have been during professional soccer games, NBA-games and through various social media channels. Suggesting it to be considered as both a privately and publicly consumed good. Hence, it could be argued that a purchase could be triggered by conspicuous, personal and socially comparative reasons.

Alliance justification

By combining Louis Vuitton and Amazon, two brands that are one of the most well-known brands in their respective category, the researchers aim to identify individuals that are familiar with both brands more easily. Familiarity with the brands was deemed desirable as it would mean that the study would explore real perceptions and attitudes towards a brand alliance between a luxury brand and an online marketplace. By exploring this topic, the research seeks to contribute with new insight on how such an alliance could be approached, both in terms of further academic research and managerial implications.

Development of case study

In order to give participants a realistic impression of the hypothetical brand alliance, the researchers used photoshop to illustrate Louis Vuitton’s presence on Amazon’s marketplace. This was done by presenting a manipulated picture of a Louis Vuitton product on Amazon's marketplace. The illustration was created with several factors in mind. Firstly, it was deemed important to make sure that the participants understood that the product was present on Amazon. Hence, a typical “product-view” from Amazon was used as the background on which a Louis Vuitton product was placed. Secondly, it was important to show realistic pictures of the chosen product. Therefore, pictures of the products were taken from Louis Vuitton original webshop. Lastly, product information needed to be accurate and representative of the product and the brand. Therefore, product descriptions and price information were also recreated as presented on Louis Vuitton’s website.

3.4.2 Interview strategy

Since the research questions seek to reveal information about how consumers perceive a certain phenomenon and their attitude towards it, it was decided to employ semi-structured interviews.

24 Semi-structured interviews (SSI’s) was deemed beneficial for this purpose as they are great for exploring the reasons behind individuals’ opinions and attitudes. SSI’s are good for exploring why consumers reason the way they do as the method presents the opportunity of asking the interviewees to explain and elaborate on answers that are of special importance for the study. Furthermore, SSI’s can be argued to be congruent with the chosen research philosophy of this thesis, as it presents the possibility to find and understand underlying meanings (Saunders et al., 2016).

Another factor influencing the choice of strategy is the complexity of the topic of luxury brands and the oxymoron of distributing them online, as described in the introduction. Contrary to questionnaires, interviews are best employed when a large number of questions are to be asked and when open-ended questions are required. They are also preferred when further explanation might be needed or when the logic of questioning might be adapted (Saunders et al., 2016).

In contrast with in-depth interviews, semi-structured interviews (SSI’s) where chosen because they employ a mix of predetermined questions (open and closed) and free discussions about topics that appear throughout the interviews. As mentioned previously, a wealth of literature exists on brand images, brand alliances and luxury consumption. However, limited research exists on luxury brands in an online context. Hence, making SSI’s purposeful for this study in two ways. On the one hand, it is beneficial as it allows the researchers to cover essential aspects of underlying theory. On the other hand, it allows for new information to emerge from the discussions which might not be covered in the theoretical framework (Saunders et al., 2016).

Preparing for SSI’s

When it comes to qualitative methods, such as semi-structured interviews, data quality is often of major concern. One way of mitigating the likelihood of poor data collection is to be well prepared before conducting the interviews. The researchers prepared for the interviews by submerging themselves into relevant academic fields to acquire appropriate knowledge about topics that were to be discussed. By doing so the researchers are more likely to instill feelings of credibility among interviewees, better assess the accuracy of responses and to probe essential but insufficiently answered questions (Saunders et al., 2016).

Furthermore, important questions where crafted and themes were developed before conducting the interviews. These questions and themes were derived from the theoretical framework with

25 the intention to direct the interviews towards the purpose of this thesis. Before each interview, a selection of themes was sent electronically to each participant so they could adequately prepare for the session. The specificity of how the material was sent will be discussed under section 3.5.3 (Interview design).

3.5 Data collection

In the following section the authors will argue for the chosen sampling technique followed by the applied interview design. Thereafter, the specificities regarding the context in which data was collected will be accounted for.

3.5.1 Sampling technique

The sampling technique is a vital aspect of research since an inappropriate sample can invalidate any conclusions made from the research findings (Saunders et al., 2016). As mentioned previously, the purpose of this study is to explore consumer perceptions, attitudes and purchase intention towards a luxury brand being distributed on an online multibrand marketplace. Therefore, it was necessary for the study to conduct research on individuals who were familiar with both brands. Additionally, as this study focus on millennials, only participants who were born between the years of 1982 and 1998 was selected. Millennials were identified to be of specific interest as their online luxury purchasing behavior is disruptive to previously known luxury purchasing behavior of older generations (see section 2.7). Hence, making their perceptions and attitudes towards the online distribution of luxury relevant and congruent with the purpose of this study. Consequently, it was paramount for the study to identify individuals who fulfilled both the brand familiarity and age criteria for the millennial cohort. For these reasons, a purposive sampling technique was used.

Purposive sampling is a sampling technique that rely on the judgment of the researchers to identify and select subjects that provide relevant data. The technique does not aim to be representative nor provide generalizable data. Purposive sampling, being a non-probabilistic sampling procedure, instead promote informational depth and source diversity. Hence being great for exploratory studies (Saunders et al., 2016) and appropriate for this study. Initially, it was recognized that the chosen sample would be quite difficult to identify. Therefore, the sampling procedure started by identifying two individuals, within the social network of the researchers, that fit both sampling criteria. Thereafter, the researchers deemed referrals from the two individuals to be an appropriate way of continuing the sampling process. Referred

26 individuals where then approached with an enquiry to participate in the study and asked for additional referrals. This procedure is also known as a linear snowball sampling technique. This sampling procedure is specifically useful when participants are difficult to identify (Saunders et al., 2016).

In total, ten people were contacted as a result of the snowball sampling procedure described above. All of the referrals were screened before participating in the interview to see if they fulfilled the brand familiarity and age criteria for the millennial cohort. The interviewees consisted of 50% males and 50% females, between the ages of 22 and 39. On the following page, Table 1 presents an overview of the interviewees participating in the study.

Table 1. Participant

number

Gender Age Location Duration

1 Male 22-25 Jönköping 62 min

2 Female 30-38 Linköping 69 min

3 Female 22-25 Jönköping 52 min

4 Male 22-25 Stockholm 33 min

5 Female 26-29 Stockholm 55 min

6 Male 30-38 Linköping 54 min

7 Female 22-25 Jönköping 46 min

8 Male 22-25 Halmstad 47 min

9 Female 26-29 Linköping 49 min

10 Male 22-25 Halmstad 43 min

27 3.5.2 Interview guide

Initially, the researchers developed an interview guide outlining themes and specific questions that were essential for the purpose of the study. Furthermore, the guide was developed to ensure that the order of themes and specific questions asked during the interviews would be perceived as logical. A pilot study was conducted to ensure that the interview questions were formulated in a way that were easily understood by the participants. The interview design was tested on two individual participants within the social network of the researchers that fit the sampling criteria mentioned above. The pilot study revealed valuable information with regards to phrasing and differences in interpretation of questions. This information was used to add, remove and adapt the wording of certain questions to better capture its intended purpose. The pilot study also resulted in some changes of the flow of questions.

Since the interviewees first impression of the researchers might significantly impact the outcome of an interview (Saunders et al., 2016), the interview initiation was outlined prior to conducting the interviews and included the following specificities:

1. Thanking respondents for participating in the study 2. Outlining the themes and topics to be covered

a. Prior luxury shopping experience b. Prior online shopping experience

c. Perceptions and attitudes towards a luxury brand in online contexts 3. Reiteration of GDPR and anonymity agreement

4. The request to record the interview electronically

5. Reconfirmation of consent and assurance that enough time had been set aside

After covering the above-mentioned points of the interview guide, the researchers began to conduct the actual interview. The three themes outlined in the beginning of the interviews were (1) prior luxury shopping experience, (2) prior online shopping experience and (3) perceptions and attitudes towards a luxury brand in online contexts. The numbering of these themes represents the order in which each theme was discussed throughout each interview. Each theme was developed to fit the purpose of the thesis and will be justified and explained hereafter.