WIMONRUT BOONSATEAN

LIVING WITH TYPE 2 DIABETES

IN A THAI POPULATION

Experiences and socioeconomic characteristics

MALMÖ UNIVERSIT Y HEAL TH AND SOCIET Y DOCT OR AL DISSERT A TION 20 1 6:4 WIMONRUT BOONS A TEAN MALMÖ LIVIN G WITH T YPE 2 DIABETES IN A THAI POPUL A TION

L I V I N G W I T H T Y P E 2 D I A B E T E S I N A T H A I P O P U L A T I O N : E X P E R I E N C E S A N D S O C I O E C O N O M I C C H A R A C T E R I S T I C S

Malmö University,

Health and Society Doctoral Dissertations 2016:4

© Wimonrut Boonsatean 2016 ISBN: 978-91-7104-688-8 (print) ISBN: 978-91-7104-689-5 (pdf) ISSN: 1653-5383

WIMONRUT BOONSATEAN

LIVING WITH TYPE 2 DIABETES

IN A THAI POPULATION

To my beloved family and my wonderful relatives วันนี้เหนื่อย... ใช่ว่าพรุ่งนี้จะไม่ไหว วันนี้ท ้อ... ใช่ว่าพรุ่งนี้จะต ้องถอย วันนี้เจ็บ... ใช่ว่าจะไม่เหลือใคร เพราะพรุ่งนี้ ก็จะเป็นวันใหม่ สิ่งใหม่ๆ ย่อมเข ้ามา

CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... 7 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS ... 9 INTRODUCTION ... 10 BACKGROUND ... 11 Type 2 diabetes... 12Life with diabetes ... 14

Experience of living with diabetes ... 14

Social determinants effects on life with diabetes ... 15

Management of life with diabetes ... 18

Sociocultural context and its influence on the experience of living with diabetes ... 19

Thai style or Thainess ... 20

Family closeness ... 21

Thais’ hierarchical system ... 21

Spirituality and religion: Buddhism ... 22

Theoretical framework ... 24

AIMS ... 26

MATERIAL AND METHODS ... 27

Design ... 27

Setting ... 28

Revised illness perception diabetic version questionnaire (IPQ-R) ... 33

Revised diabetic self-management questionnaire (DSMQ-R) ... 34

Measurement of the psychometric properties of the instruments ... 34

Data analysis ... 35

Analysis of the psychometric properties of the instruments ... 36

Statistical analysis ... 36

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 38

RESULTS ... 40

Phase I ... 40

Handling daily living despite vulnerable conditions ... 40

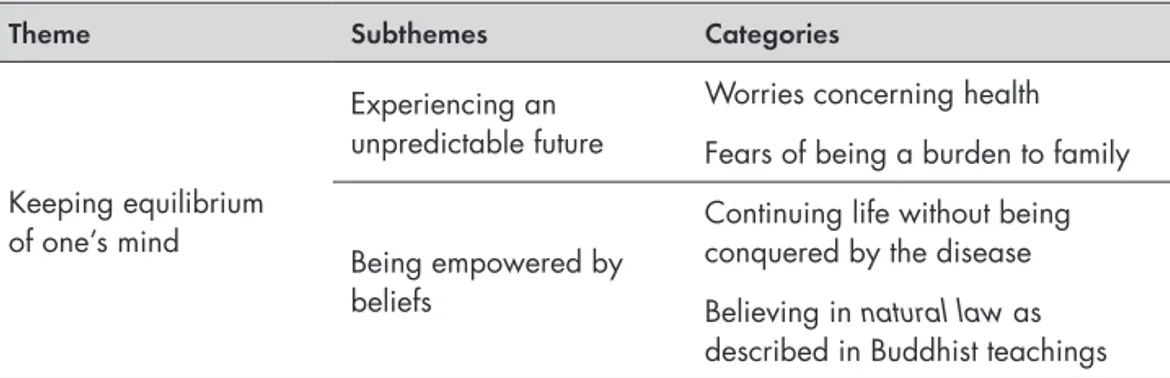

Keeping equilibrium of mind by one’s beliefs ... 42

Phase II ... 42

Psychometric properties of the translated instruments ... 42

Perception and self-management among women and men ... 43

Perception and self-management of people living in different socioeconomic conditions ... 44

DISCUSSION ... 45

Maintaining equilibrium in life with diabetes ... 45

Context-dependent: make it different ... 46

Vulnerable condition of life with diabetes ... 48

Women and diabetes ... 49

METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 52

Research design ... 52

Samples and sampling ... 52

Data collection ... 53 Measurement tools ... 53 Limitations ... 53 CONCLUSION ... 56 FUTURE IMPLICATIONS ... 57 FUTURE RESEARCH ... 58 SVENSK SAMMANFATTNING ... 59 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 62 REFERENCES ... 64

ABSTRACT

Type 2 diabetes is a matter of global concern, and has been shown to have an impact on an individual’s way of living, family, and social life. In addition, there is limited knowledge concerning the life experiences of Thai people with diabetes. The aim of this thesis was to explore the experiences of people with type 2 diabetes who live in partly low socioeconomic suburban areas of Thailand. Both qualitative analyses with 19 women of low socioeconomic status with diabetes and quantitative analyses, including 220 people with diabetes, were conducted in the suburban communities near Bangkok between 2012 and 2015.

The thesis consists of the results of four studies described in four papers. In paper I the aim was to explore how Thai women of low socioeconomic status handled their lives with diabetes. The findings showed that the women went through many stages of changes in the process of adaptation in handling their vulnerable situation influenced by diabetes and socioeconomic status. A threatened loss of status was sometimes seen as a barrier to handling their disease, whereas empowerment by one’s family helped them to feel powerful and gave them a sense of hope in living with this disease. Paper II illuminated the life experience of Thai women of low socioeconomic status living with diabetes. The findings revealed that women confronted susceptible feelings such as worrying about an unpredictable future and fears of being a burden to their family. However, they were able to maintain a balance through empowerment via the inner and outer sources of their beliefs. In paper III the aims were to investigate and compare the illness perception and self-management among women and men with diabetes,

questionnaire) demonstrated acceptable content validity and reliability, including internal consistency, inter-rater, and test-retest reliability. The findings showed that the illness perception and self-management strategies among the women and men had similar patterns, except for three aspects of illness perception. Whereas the women more often perceived the consequences of diabetes and fluctuating symptoms, the men felt more confident about efficiency of the treatment prescribed by the healthcare professionals. Furthermore, the illness perception, especially the confidence in controlling diabetes by themselves and the confidence about treatment effectiveness, in both women and men showed a weak possitive association with many aspects of self-management strategies. Paper IV examined the illness perception and self-management of Thai people with diabetes according to their socioeconomic status, as defined by income and educational level. The participants of the low-income and low-education groups perceived more negative consequences of diabetes, and the participants in the high-income and high-education group felt more confident in controlling the diabetes by themselves and were more confident about the treatment effectiveness. The participants in the low-education group perceived more fluctuating symptoms of the disease, and the high-education group showed greater understanding of their disease conditions. Furthermore, the participants in the low-education group demonstrated less effective self-care in terms of overall self-management strategies and physical activity.

The Thai people with type 2 diabetes demonstrated an ability to be able to adjust to their life situation and to keep a balance in their minds to continue their usual life with the disease. Their experiences of living with diabetes were partially affected by sex differences and socioeconomic characteristics. It may be helpful to take educational level into consideration when designing specific and proper interventions for people with diabetes in low socioeconomic areas. The Thai sociocultural context, especially in terms of family closeness and Buddhist beliefs, might also have an effect on the life of people with diabetes.

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS

This thesis is based on the following papers referred to in the text in Roman numerals I-IV. The papers have been reprinted with permission from the publishers.

I. Boonsatean, W., Dychawy Rosner, I., Carlsson, A., Östman, M. (2015). Women of low socioeconomic status living with diabetes: Becoming adept at handling a disease. SAGE Open Medicine, 3. doi:10.1177/ 2050312115621312

II. Boonsatean, W., Carlsson, A., Östman, M., Dychawy Rosner, I. (2016). Living with diabetes: Experiences of inner and outer sources of beliefs in women with low socioeconomic status. Global Journal of Health Science,

8. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n8p200

III. Boonsatean, W., Östman, M., Dychawy Rosner, I., Carlsson, A. (2016). Illness perception and self-management among Thai women and men living with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes (Re-submitted)

IV. Boonsatean, W., Dychawy Rosner, I., Carlsson, A., Östman, M. (2016). Socioeconomic status - influences on illness perception and self-management in a Thai type 2 diabetes population.

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) has become a matter of growing concern for healthcare professionals because of the global increase of this disease (Shaw, Sicree, & Zimmet, 2010). Diabetes is acknowledged as a long-term condition, which includes various complications (Scobie & Samaras, 2012), and it is one of the common chronic diseases in Thailand (Thonghong, Thepsittha, Jongpiriyaanan, & Gappbirom, 2013). Sometimes T2D is considered as a lifestyle disease because it is subject to various forms of adaptation and modification of daily living (Paterson, Thorne, & Dewis, 1998; Paterson, Thorne, Crawford, & Tarko, 1999), and it also has an effect on many aspects of people’s lives (Scobie & Samaras, 2012).

When it comes to the issue of the experiences of living with T2D in Thailand, there is a lack of knowledge about how people live with this disease. Due to the reason that diabetes is perceived as a heredity and common disease, most people do not feel frightened when they are diagnosed with it. They accept medical recommendations but continue to live with their usual life. Strict adherence to controlling diabetes is performed when people are admitted to the hospital; however, after being discharged from the hospital, they have to go back to living their life as usual in the community and take more or less full responsibility for controlling their lives with diabetes. Since living with diabetes is complex and requires day-to-day adjustment to suit individuals’ lives, the way in which people with T2D experience their life situations and any factors affecting their experiences need to be further studied. Increased knowledge in this field may assist healthcare professionals in gaining a better understanding of the patients’ perspectives and in designing proper and effective interventions for this population.

BACKGROUND

Living with diabetes is seen as a complex, progressive, and multidimensional process affected by a broad range of individual characteristics such as sex, income, or education (Beryl Pilkington et al., 2010; Walker, Smalls, & Egede, 2015) and influences from the social context (Sissons Joshi, 1995; Sowattanangoon, Kochabhakdi, & Petrie, 2008). To put this subject in perspective, it is necessary to be concerned not only about the disease but also about the ways that people experience the disease and in what ways the disease influences people’s lives, as this may have important implications for health and healthcare.

Health is one aspect of a person’s life experiences, which is subjective and highly individual (Bennett, Perry, & Lawrence, 2009). The definition of health, established in the constitution of the World Health Organization (1948), stated that “Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity.” This definition confirms health from a holistic view, and suggests that it cannot be solely explained according to one dimension. In fact, health and illness are interwoven in people’s lives and affect not only their body but also the way in which they describe or identify themselves. Additionally, health and illness are also influenced by many factors embedded in the social context of people. Health is considered as a multifactorial phenomenon and is more complex than an individual’s lifestyle choices, and may include socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental issues (Bennett et al., 2009). People can experience health whether they have a disease or not; in other words, people can feel healthy even if they have a disease. Diabetes is one example of a chronic disease that affects people’s way of living (Moser, van der Bruggen,

This chapter focuses on the individual’s life with diabetes and the effects of socio-demographic factors and social context on the individual’s life. These effects and interactions are described according to the scope of the adjusted Social Ecological Model used in this thesis. Information on type 2 diabetes and brief information about the model used are also included in this chapter.

Type 2 diabetes

T2D is a chronic metabolic disorder, where the body cannot utilize glucose from food because of either insufficient insulin production or inactive insulin (Sönksen, Fox, & Judd, 2005). It has a strong genetic background related to the genes of ß-cells in the pancreas. In addition, unhealthy life habits (sedentariness and high consumption of carbohydrates or fat) and obesity have also been suggested to be risks in developing diabetes (Scobie & Samaras, 2012). Furthermore, diabetes increases the risk of macrovascular and microvascular diseases, leading to serious complications (retinopathy, nephropathy, hypertension, stroke, and cardiovascular disease), which may result in amputation (Naemiratch & Manderson, 2007). These overall microvascular complication rates decrease when blood glucose control is improved. For example, for every percentage point decrease in HbA1c there is a 35% reduction in the risk of microvascular complications (American Diabetes Association, 2002).

The worldwide prevalence of diabetes among adults aged over 18 years in 2014 was estimated to be 9% (World Health Organization, 2015). Global estimates of diabetes among adults indicate the large burden of diabetes, especially in developing countries (Guariguata et al., 2014). This is in consistent with the sharp increase in the prevalence of T2D that has been observed in the South-East Asian region (Ramachandran, Snehalatha, & Ma, 2014). In Thailand, T2D has been found to be one of the five most common chronic diseases (Thonghong et al., 2013) and only 28% of patients are able to control their disease (Sudchada et al., 2012). The diabetes prevalence in the last decade (2003-2013) of Thai people has tended to increase (Bureau of Non Communicable Disease, Ministry of Public Health, 2014), to approximately 6.4% in 2013 (Guariguata et al., 2014), and the admission rate of Thai patients with diabetes to public hospitals in 2013 was 1,081 persons/100,000 population/year (Bureau of Non Communicable Disease, Ministry of Public Health, 2014).

Various international studies have explored the dissimilarities in developing diabetes with regard to racial background and ethnicity (Peek, Cargill, & Huang, 2007; Sequist, Adams, Zhang, Ross-Degnan, & Ayanian, 2006), sex (Tenzer-Iglesias, 2014), and socioeconomic status (Elgart et al., 2014; Hwang & Shon,

2014; Tang, Chen, & Krewski, 2003). Ethnic minorities (Peek et al., 2007) and people with a low income or low education (Elgart et al., 2014; Hwang & Shon, 2014; Tang et al., 2003) are more like to have high prevalence of diabetes and attending complications, especially dyslipidemia and hypertension (Sequist et al., 2006). Higher rates of complications may lead to poor diabetes control (Gaede et al., 2003). In developing countries, as in Thailand, urbanization and industrialization have driven changes in lifestyles, and these rapid transitions are accompanied by increased risk factors for T2D (Guariguata et al., 2014).

Diabetes care in Thailand belongs to the health services delivery system provided by the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH), which supplies about 90% of healthcare services ranging from primary to tertiary healthcare (Chunharas & Boonthamcharoen, n.d.). Specialized medical services and formal health educational sessions for chronic diseases, including diabetes, are usually provided by specialist doctors and nurses in the public hospitals at the tertiary healthcare level (including some general hospitals, regional hospitals, and university hospitals) and in the large private hospitals (ibid). Most people living in communities are under the responsibility of the Health Promoting Hospitals (HPHs), a frontline healthcare service of the MOPH which delivers mostly preventive and promotive care. Diabetes care is included in the primary medical care service (basic curative care) provided by the staff of HPHs under the supervision of the doctor from community or provincial hospitals (Chunharas & Boonthamcharoen, n.d.).

All Thai citizens can access healthcare services from various health facilities with or without payment depending on the type of health insurance schemes they possess. These schemes comprise civil servants’ medical benefits for state enterprise employees, social security for private employees, and universal health coverage which covers the remainder (Chunharas & Boonthamcharoen, n.d.; Faramnuayphol, Ekachampaka, & Wattanamano, 2011) more than 75% of the Thai population (Deerochanawong & Ferrario, 2013). People can get free essential treatment and care at a specifically-recommended hospital that is stated in their health insurance schemes. However, if people can afford the cost of treatment, they can seek healthcare services from other hospitals. Although all people possess one type of health insurance scheme, inequalities in access to treatment still persist in Thailand (Deerochanawong & Ferrario, 2013). There are differences in the types of healthcare services for people in various localities and for those with various levels of social status (Chunharas & Boonthamcharoen, n.d.). Family members

Life with diabetes

Type 2 diabetes has been shown to intrude into an individual’s daily living and requires life-long changes in many aspects of life (de Alba Garcia et al., 2007). Living with diabetes may be considered not only on the individual level, including lifestyle changes or emotional control, but on the family level (Caban et al., 2008) and in social life as well (Manderson & Kokanovic, 2009). This topic provides information concerning the experiences of people’s life with diabetes, the effects of personal and social factors on their lives, and how they manage their life with the disease.

Experience of living with diabetes

Living with a chronic disease, such as diabetes, is a complicated experience that is typified by an ongoing and continuous shifting process (Paterson, 2001). This experience will influence people’s perception of their health from a subjective perspective, which is individualized and involves many dimensions of people’s lives. People with diabetes do not want other people to label them as having the disease (Youngson, Cole, Wilby, & Cox, 2015). Rather, people describe their lives with diabetes in a way that makes sense to them, for example referring to themselves as a “diabetic person” or “patient,” and they struggle to live with this identity (Manderson & Kokanovic, 2009; Olshansky et al., 2008). The image of diabetes in people’s minds was shown according to two aspects: first was seriousness because the disease shows continuous progression and life-threatening characteristics; second was endurance because living with diabetes is difficult and requires energy to cope with it (Hörnsten, Sandström, & Lundman, 2004). Western studies have found that people express a psychological burden when living with diabetes, such as feeling different from others (Vermeire et al., 2007), being ashamed or feeling stigmatized for having diabetes (Hörnsten et al., 2004; Utz et al., 2006), and being afraid of future complications of the disease (Olshansky et al., 2008). Some people perceive diabetes as something that has taken over and dictated their lives, and the only way out is to die (George & Thomas, 2010). The study of Gillibrand and Flynn (2001) found that some people try to use “ignoring” or “reality avoidance” as coping strategies in order to accept having diabetes.

While living with this shifting process, people with diabetes attempt to persist with their living by continually learning and sharing knowledge with other people, creating a supportive environment, and developing personal skills (Paterson, 2001). When people appraise a disease as an opportunity for meaningful change in relation to their world, wellness seems to be presented in the foreground and people understand that it is possible to have wellness although living with diabetes

(ibid). Eastern studies have found positive experiences of life on the part of people that see positive challenges in living with diabetes and that perceive support from others, especially family members (Yamakawa & Makimoto, 2008). Additionally, Thai people express the idea that they can continue their usual life despite having diabetes because the disease is not seen to affect their ability to work or to perform daily activities (Naemiratch & Manderson, 2008).

Social determinants effects on life with diabetes

The social determinants of health are described as economic and social conditions or circumstances that influence people’s health (Marmot, 2005). This broad definition emphasizes the conditions such as poverty, education, socioeconomic status, and social structure that influence the health of the population or limit the ability of people to achieve health equality e.g. availability of community-based resources, access to education or healthcare services, economic and job opportunities, and social support (Koh, Piotrowski, Kumanyika, & Fielding, 2011). In this thesis, the aspect of sex differences will be discussed under the topic of social determinants. Although sex is not a factor in the social determinants of health, it is considered a significant covariant that also has an effect on health outcomes (Walker, Gebregziabher, Martin-Harris, & Egede, 2014). This topic then focuses on socioeconomic status, which is defined according to income and educational level, and sex differences, which are related to the differences in the biological construct of women or men.

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status has been found to affect individuals’ life with diabetes (Beryl Pilkington et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2015). People with T2D living in low socioeconomic areas with a low income have described their hardships in confronting the daily struggle to survive (Beryl Pilkington et al., 2010), and several international studies have identified the association between T2D and socioeconomic status (Elgart et al., 2014; Jaffiol, Thomas, Bean, Jégo, & Danchin, 2013; Tang et al., 2003). The relationships between an increased prevalence of diabetes with a decreasing level of income, education, and socioeconomic status can be found in contemporary studies (Hwang & Shon, 2014; Jaffiol et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2003), except for a study in Sri Lanka, which arrived at a contrary result (Pubudu De Silva et al., 2012). Furthermore, socioeconomic status (educational

Many studies have explored the impact of socioeconomic status on glycemic control (Reisig, Reitmeir, Döing, Rathmann, & Mielck, 2007; Ricci-Cabello, Ruiz-Pérez, Olry de Labry-Lima, & Márquez-Calderón, 2010; Walker, Gebregziabher, et al., 2014; Walker, Smalls, Campbell, Strom Williams, & Egede, 2014) and the diabetes management of people in various countries (O’Neil et al., 2014; Shrivastava et al., 2016). Low socioeconomic status has been found to be related to poor glycemic control, which is measured by high values of fasting plasma glucose (FPG) (Kollannoor-Samuel et al., 2011) and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) (Kollannoor-Samuel et al., 2011; Reisig et al., 2007). A study conducted with Indian people with diabetes has shown that increased costs in diabetes care have forced people into economic hardships in the family and are related to inadequate disease management (Shrivastava et al., 2016). In addition, greater economic hardships were found to be associated with sub-optimal medication taking and less regular physical activity (O’Neil et al., 2014).

Research studies that are focused on the association between income (Mann, Ponieman, Leventhal, & Halm, 2009; Thomas, Jones, Scarinci, & Brantley, 2003) or educational level (Agardh et al., 2011) and people’s lives with diabetes have also shown similar results as the studies of socioeconomic status. According to the suggestions of Telfair and Shelton (2012), education may be the most basic component of socioeconomic status because it can provide opportunities for future occupation and earning potential. Additionally, education also enhances an individual’s sense of control (Mirowsky & Ross, 1998; Slagsvold & Sørensen, 2008), which is considered an important factor in helping people gain knowledge and life skills; therefore, better-educated people have more ready access to health resources for promoting healthy behaviors (Adler & Newman, 2002). Moreover, education is considered one factor that can predict adherence to self-management, especially diet management, among African people with diabetes (Abubakari et al., 2013). Earlier studies have reported the association of higher diabetes knowledge with better medication adherence and better glycemic control (low HbA1c level) in Malaysian people with diabetes (Al-Qazaz et al., 2011). Regarding the effect of income on people with diabetes, a higher prevalence of diabetes distress (Pandit et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2003) and suboptimal diabetes knowledge and beliefs (Mann et al., 2009) have been more often found in people of low income. Additionally, low-income status has been identified as one of the barriers to performing effective diabetes management (Vest et al., 2013).

Sex differences

Differences in the biology, social roles, and attitudes of women and men may have different impacts on individuals’ health (Phillips, 2005). An earlier study

has identified different biological risks in developing diabetes between women and men (Tenzer-Iglesias, 2014). Women are more likely to have diabetes than men, with the risk of developing the disease 1.65 times greater than that of men (Sobers-Grannum et al., 2015). Furthermore, fluctuations in estrogen level during the menstrual cycle can affect the effectiveness of glycemic control; when the estrogen level is high, the body is resistant to insulin (Bruns & Kemnitz, 1994).

Women and men also vary in their health perceptions and attitudes, which may make them view life with diabetes differently. Verbrugge (1985) has found that childhood socialization and adult role commitments encourage great awareness of physical symptoms and the care for such symptoms among women. Women are more sensitive to body discomfort and try to label their symptoms as physical illness more than men do, whereas men try to tolerate physical symptoms with lower estimation of their illness and feel that it is not manly to be ill (ibid). Other studies have shown that women more often view their living with diabetes in a negative way and worry about future complications (Fitzgerald, Anderson, & Davis, 1995; Koch, Kralik, & Sonnack, 1999; Penckofer, Ferrans, Velsor-Friedrich, & Savoy, 2007). Distress, anxiety, and depression are more often seen as common emotions in women than men (Gucciardi, Wang, DeMelo, Amaral, & Stewart, 2008; Svenningsson, Björkelund, Marklund, & Gedda, 2012; Tenzer-Iglesias, 2014), which can lead them to feel overwhelmed and to find it difficult to manage their life with diabetes (Svenningsson, Marklund, Attvall, & Gedda, 2011). As found in contemporary research, diabetes distress is linked to self-care behaviors and glycemic control (Pandit et al., 2014). On the other hand, uncertainty about glycemic control is a risk factor for anxiety and depression (Collins et al., 2009). Men with diabetes are more likely to believe in themselves and feel hesitant to talk with others about the limitations that diabetes imposes on their lives (Mathew, Gucciardi, De Melo, & Barata, 2012), and they express strong confidence in their ability to control their life with diabetes (Brown et al., 2000). An earlier study has shown that men view their lives in a positive way and feel that diabetes is a part of life that challenges them for the better (Koch, Kralik, & Taylor, 2000). However, both women and men still need support from healthcare professionals in both affective and practical aspects (Mathew et al., 2012).

Other Western studies have reported different aspects in handling diabetes among women and men. Women for example have been seen to be likely to acknowledge and integrate diabetes management into their daily lives by reducing

experiment with new strategies to control their situations, and use moderate intake of unhealthy food in managing their diabetes, excluding when participating in social events (Mathew, Gucciardi, De Melo, & Barata, 2012).

Management of life with diabetes

“Managing life with a disease,” including diabetes, is a phrase used to describe the ability of an individual, in collaboration with family and healthcare professionals, to manage the symptoms, treatment, lifestyle changes, and psychosocial consequences of a disease (Richard & Shea, 2011). A more preferable term which has a close meaning is “self-management,” which is seen as an ongoing and dynamic process, involving the physical, psychological, and social management that is related to diabetes (Boonsatean, 2014). In other words, successful self-management should encompass the multi-level influences (personal, interpersonal, and social level) that have an impact on an individual’s living conditions. The management should be formulated as a collaboration between individuals, family, and the healthcare team; however, individual responsibility seems to be a cornerstone for continuing this process of management in order to develop personal knowledge and skills in living with diabetes (American Diabetes Association, 2014; Boonsatean, 2014).

The process of managing life with diabetes was seen in earlier studies as a cyclical process of continuous change, from being diagnosed with diabetes to being stable in one’s life with the disease, and this process is characterized by active evolution and ongoing new discoveries (Hörnsten, Jutterström, Audulv, & Lundman, 2011; Moser et al., 2008; Paterson et al., 1998). Not all people with diabetes can reach all of the stages in the process of self-management. The obstacles to successful diabetes management have been described in many studies (Nagelkerk, Reick, & Meengs, 2006; Ramal, Petersen, Ingram, & Champlin, 2012; Vermeire et al., 2007), such as insufficient knowledge and incomplete understanding of one’s diet plan, lack of individualized information and coordinated care, limited resources of support, and the relationship to healthcare providers. In order to facilitate successful management, one study mentioned the positive influence of social networks (e.g., family members, friends, neighbors, co-workers) and indicated that family members particularly serve as instrumental and emotional support among low-income people with diabetes (Vest et al., 2013). Another study also mentioned family members as the primary source of support, although people sometimes feel dissatisfied with the help that they receive (Gleeson-Kreig, Bernal, & Woolley, 2002). On the other hand, one study found that most people with diabetes perceived support from healthcare professionals (Oftedal, Bru, & Karlsen, 2011). According to previous studies, low associations were found between social

support and diabetes self-management (Gleeson-Kreig et al., 2002; Oftedal et al., 2011), especially regarding the aspects of diet and exercise (Oftedal et al., 2011).

In managing diabetes to achieve optimal glycemic control, a set of self-care activities is required (Lautenschlager & Smith, 2006). People with diabetes in an earlier study (de Alba Garcia et al., 2007) that exhibited good glycemic control showed greater comprehension and a stricter approach to their diet and plasma glucose levels. Additionally, diet management was also found to be difficult to perform in accordance with medical recommendations, although people recognize the need for change (Mumu, Saleh, Ara, Afnan, & Ali, 2014), and a dietary plan for glycemic control has been linked to the loss of pleasure of women with diabetes (Péres, Franco, Santos, & Zanetti, 2008). Even though modification of one’s diet can be difficult, it is necessary to make such changes in order to manage diabetes. A compulsory set of self-care activities according to the standards of medical care for diabetes comprises lifestyle changes, including adjustment of eating behaviors and increased physical activities, as well as taking anti-diabetic agents, either pills or insulin (American Diabetes Association, 2014). Monitoring carbohydrate intake based on counting or experience-based estimation remains a key strategy in achieving glycemic control (ibid). Most people with diabetes in previous studies (Lautenschlager & Smith, 2006; Lynch, Fernandez, Lighthouse, Mendenhall, & Jacobs, 2012) used portion control as a means to control their plasma glucose level—they tried to consume smaller portions of food and to eat more fruit and vegetables. For adults with diabetes, 150 minutes/week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity are recommended for glycemic control (American Diabetes Association, 2014). Since sometimes a vague meaning of exercise is perceived, people in contemporary research perform it differently or do not regularly exercise (Lautenschlager & Smith, 2006; Lynch et al., 2012). Reducing weight has been mentioned as another strategy to control diabetes, and the people in one study tried to use exercise and limited their diet as methods of losing weight, but few people reach success (Lautenschlager & Smith, 2006).

Sociocultural context and its influence on the experience

of living with diabetes

The term culture can be described as a set of traditions, social organizations, language, values, and beliefs involving the everyday life of people living in the same society (Kleiman, 2006). Culture is shown through observable behaviors

with these backgrounds understand and manage a disease differently from Western people (Gervais & Jovchelovitch, 1998), particularly persons with diabetes (Tseng, Halperin, Ritholz, & Hsu, 2013), and this may reflect different perspectives about health and illness. Western studies have found that people tend to believe in and perform healthcare practices based on a biomedical model and emphasize the issue of self-responsibility in taking care of themselves (Åsbring, 2012; Joffe, 2002). On the other hand, Eastern people in an earlier study seemed to emphasize the holistic view of the body, mind, and sociocultural aspects in dealing with the issue of health and illness (Gervais & Jovchelovitch, 1998). Cultural values and beliefs have been found to influence the life experiences of individuals with diabetes and can shape their health perceptions and practices (Sowattanangoon, 2008). Another study has also shown the effect of the sociocultural context on how people perceive the cause of diabetes (Sissons Joshi, 1995).

When it comes to how the Thai sociocultural context may have an influence on the perceptions and management of people with diabetes, four main aspects can be cited: Thai style or Thainess; family closeness; the Thai hierarchical system; and spirituality and religion, focusing on Buddhism.

Thai style or Thainess

Thainess can be described as what it means to be Thai, including the common ways that Thai people respond to their situation or to other people. Thainess seems to be a fundamental key to understanding the Thai people. Calling everyone as relatives and using it as a prefix before a person’s name, such as “pee nong (sister or brother),” “par (aunt),” or “lung (uncle), is a common way for Thai people to communicate with other people and it can be used to become acquainted or to create relationships with other people (Samakkan, 1999). Burnard and Naiyapatana (2004) have described the Thai personality as follows. Most Thai people try to control their emotions and show emotional neutrality by keeping their feelings inside, even when they confront conflicts or feel unsatisfied. Usually, the Thai people avoid expressing strong feelings and compromise in order to maintain good relationships with other people. Podhisita (1998) has described this behavior by using the term “cool heart (chai yen),” meaning that people confront situations always with a smiling face and try to handle them with care. People with an illness, including diabetes, use the concept of a cool heart to respond when facing anxious situations, and this specific behavior is called Choei Choei (being silent or being indifferent or impartial) in the Thai language (Naemiratch & Manderson, 2008). This can help people avoid anxiety or anger and allows them time to suppress their emotions and to calm down (Podhisita, 1998).

Family closeness

The family is acknowledged by Thai people as an important factor in their lives and provides support for family members in various ways. Being a family member contains profound meaning and refers not only to living together under the same roof but also providing reciprocal attentiveness, encouragement, and understanding (Bunyanetara, 1999). Research has found that family and kinship relationships are included in the meaning of care described by Thai people, which means the support of parents and grandparents, family closeness, and sharing happiness and suffering either in health or in sickness (Lundberg, 2000). Support from the family can help people with diabetes confront daily difficulties and motivate them to manage their disease (Lundberg & Thrakul, 2012). Further, care and concern among family members are important factors in increasing women’s life satisfaction (Puavilai & Stuifbergen, 2000).

Studies conducted among Thai people (Lundberg & Thrakul, 2012), Thai women (Lundberg & Thrakul, 2011), as well as Western people with diabetes (Moser et al., 2008; Samuel-Hodge et al., 2000; Utz et al., 2006) have shown that family members provide support for people with diabetes in many ways, including physical support (reminding people to take their medicine or to follow dietary plans, helping with housework, or providing transportation to the hospital) and emotional support (listening to people’s situation and conflicts). On the other hand, financial support from family members, especially the children, is typically found in the studies conducted with Thai people (Lundberg & Thrakul, 2011; 2012). Children are perceived as the best source of support for their parents and grandparents, especially regarding emotional and financial support (Puavilai & Stuifbergen, 2000). This support relies on Thai social norms where children are expected to demonstrate respect (Khourop), gratitude (Ka-thanyo), and appreciation to their benefactor (Thaubtan boonkhun) (Lundberg, 2000).

Thais’ hierarchical system

Thai society is hierarchical and this play an important role in Thais’ social life (Podhisita, 1998; Sowattanangoon, 2008). This social norm can be seen at every level of the Thai social units—the family, organizations, the community, and society. Hierarchy can be considered as a set of verbal and nonverbal performances linking persons of higher and lower status in order to maintain harmonious relationships—the status of each person will be evaluated by each

(Podhisita, 1998). Each person is expected to behave appropriately according to their evaluated status in both a verbal and nonverbal manner, and those that do not conform to this social norm will be disapproved of or disliked in society (Podhisita, 1998). In the family, parents are in a higher position and children are expected to be compliant and support their parents in every respect, especially when their parents become elderly or ill (Sowattanangoon, 2008). In the healthcare system, a patient has to find one’s status when meeting healthcare professionals and behave properly. A patient for example is expected to pay respect and listen to healthcare providers, whereas a health professional is expected to provide support, benevolence, and compassion (Sowattanangoon, 2008). Studies have found that this social value contributes to conflicts in patients with diabetes; hence, sometimes people with diabetes hide the truth of how they manage their life with diabetes (Naemiratch & Manderson, 2006) and this may lead to less effective patient-healthcare provider communication. However, this conflict can be reduced by using a Thai social norm called krengjai (the consideration for other people’s feelings and not wanting to annoy anyone either in action or feeling) (Rabibhadana, 1999). Krengjai is a mechanism used to protect oneself or others against conflicts in the hierarchical system and to maintain a harmonious relationship among communicators.

Spirituality and religion: Buddhism

The word religion refers to a system of beliefs and religious practices, such as praying, rituals, or worship in a church or a temple (Srisopa, 2001). Spirituality as described by Jenkins and Pargament (1995) refers to the “personal feeling of connectedness to a higher power and the ultimate source of life’s meaning and value” (Sowattanangoon, 2008). Sometimes, these two terms can be used synonymously. This topic uses the term religion according to both meanings.

Religion has been seen to be an important factor in coping and dealing with diabetes and also is positively involved in the physical and mental well-being of people with diabetes. Several international studies have investigated the ways in which people use religious beliefs to improve their mental strength and cope with diabetes (Lundberg & Thrakul, 2013; Samuel-Hodge et al., 2000; Sowattanangoon et al., 2009; Utz et al., 2006). Additionally, religion seems to have a positive impact on the self-management activities of people with chronic disease (Becker, Gates, & Newsom, 2004) and people with diabetes (Lundberg & Thrakul, 2012; Sowattanangoon et al., 2009; Utz et al., 2006), which are often related to glycemic control (Samuel-Hodge et al., 2000). Another study has found that high scores on Buddhist values are significantly related to a better HbA1c

level (Sowattanangoon, Kochabhakdi, & Petrie, 2008), which may imply that Buddhist beliefs may promote self-care activities among Thai people with diabetes.

Buddhism is one of the major religions in the world. It began 2,559 years ago in India when Siddhartha, the Buddha, discovered how to bring happiness into the world. Nearly all of Thai people are Buddhists (94.6%) (Ministry of Information and Communication, 2012) and the Buddhist Era (BE) is used for naming the years in Thailand (BE is 543 years older than the Christian Era).

Buddhism is not only the main religion but also the principal philosophy leading to the way of life among Thai people; hence, it has a strong influence on health beliefs and practices (Burnard & Naiyapatana, 2004). Additionally, Buddhism is a way of thinking and pattern of behavior with logic and reason, which encourage individuals to seek the ultimate truth in their lives that is in accordance with

natural law (Srisopa, 2001). The Buddha has taught people how to live a happy

and peaceful life by taking into consideration one’s own life, understanding it as it is, and coping with daily problems and searching for a way to true happiness (Instilling Goodness School, n.d.). The Buddha also confirmed his belief in human capability, and the idea that humans are their own master and that no higher power can dictate human destiny (Srisopa, 2001).

The Buddhist teaching, called dharma, states suffering (dukkha) and the way out of suffering as the central and important concepts of Buddhism (Phromtha, 1999; Podhisita, 1998). Suffering in the Buddhist view means any condition of life that is unpleasant, distressful, or difficult to tolerate (Podhisita, 1998). Having any disease, including diabetes, is one type of suffering because it disturbs the harmony of one’s life (Ratanakul, 2004a). For Buddhism, mind and body are interdependent, and special attention in Buddhist teaching is focused on the mind and its power in order to develop a healthy mind (ibid) by cultivating correct views of one’s self and his/her own world (Ratanakul, 2004a). Thai people with diabetes acknowledge this Buddhist view and integrate various notions of Buddhist teaching into their life in order to relieve their suffering and continue their usual life (Lundberg & Thrakul, 2013; Sowattanangoon, Kotchabhakdi, & Petrie, 2009).

The common notions in Buddhist teaching described in this thesis consist of the following: (1) the three common characteristics of existence, (2) the round of

existence, and (3) the law of karma. The three common characteristics of existence

refer to natural truths that are connected with human life and that are always found in human existence (Srisopa, 2001). Additionally, the three characteristics

to “me” forever (Phromtha, 1999; Srisopa, 2001); therefore, it is natural for the physical body to continually decay, leading to disease and death from disease. Once Thai Buddhists realize these natural truths, they can develop a sense of renunciation (Srisopa, 2001) in relation to their feeling of suffering and continue a good life, despite having a disease. The round of existence explains human life as a cycle, comprising birth, ageing, illness, and death, which continues through many lives (past life, current life, and future life) (Phromtha, 1999; Ratanakul, 2004b). Holding this notion, Thai people may see disease and death from a disease as a natural part of human life that cannot be avoided. The law of karma emphasizes the causal relation between cause and effect (Ratanakul, 2004a). Karma, meaning intended action, is not a reward or punishment by the Buddha or an external authority, and each individual possesses his/her own karma (ibid). The law of

karma describes the consequences of human actions, which are derived from

people’s previous actions through body, speech, or mind—when doing good people will receive good and vice versa (Podhisita, 1998). Everything that happens in one’s current life course is a result of previously-accumulated karma, and being healthy or having ill-health is a direct result of karma (Naemiratch & Manderson, 2007; 2008; Ratanakul, 2004a). Diabetes is sometimes called a karma disease (rohk

waehn karma) (Sowattanangoon et al., 2009), so having diabetes is perceived

as an unavoidable situation. Holding the aforementioned Buddhist notions may assist Thai people in promoting their psychological well-being and strength when confronting daily struggles, including living with diabetes.

Theoretical framework

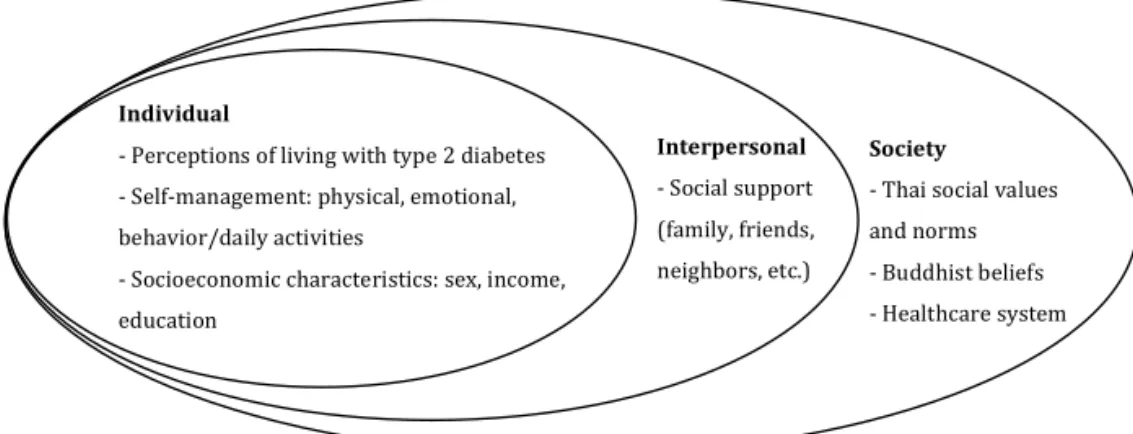

This thesis was influenced by the Social Ecological Model (SEM) (Bronfenbrenner, 1994) to gain insight into the experiences of people’s life with diabetes.

The SEM is rooted in ecological theory, which is widely used in work related to health promotion. The basic concept is linked to human development and growth, a progressive and complex process embracing a broad perspective on health that recognizes environmental features such as physical, social, and cultural factors (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). The influence of these concepts is assumed to be present in the everyday life of people that are living with any chronic disease. Therefore, understanding and improving the quality of care requires a framework that fits the life experience of people, such as that found in the ecological model of human development proposed by Bronfenbrenner (1994).

In this research, the SEM offers a broader perspective on how to understand living with the disease, including T2D. As living with diabetes is complex, it is assumed that the people’s conditions cannot be adequately understood or addressed

from a single level of analysis. The SEM seems to be appropriate as it comprises a more comprehensive approach and allows for the integration of multiple levels of influence that impact an individual’s living conditions. When applying the SEM to the experience of living with diabetes, five levels of influence have been noted: the individual or intrapersonal, interpersonal (family, friends, social groups), organizational or institutional (system, group, culture), community, and public policy levels (Whittemore, Melkus, & Grey, 2004). The key characteristics of the SEM include multiple dimensions among levels, the interaction of influences across levels, and the effects of multiple levels of environmental influences (Bronfenbrenner, 1994).

The model used in this thesis was adjusted from the work of Whittemore et al. (2004) which has a focus on applying the SEM to type 2 diabetes. This approach is considered to be appropriate for obtaining a general understanding of the phenomena dealt with in this study.

Individual

-‐ Perceptions of living with type 2 diabetes -‐ Self-‐management: physical, emotional, behavior/daily activities

-‐ Socioeconomic characteristics: sex, income, education Interpersonal -‐ Social support (family, friends, neighbors, etc.) Society

-‐ Thai social values and norms -‐ Buddhist beliefs -‐ Healthcare system

AIMS

The overall aim of the thesis was to explore the experiences of living with type 2 diabetes of a Thai population who live in suburban, partly low socioeconomic areas.

The specific aims of each paper were:

Paper I To explore how Thai women of low socioeconomic status handled their lives with type 2 diabetes

Paper II To illuminate the life experience of Thai women of low socioeconomic status that were living with type 2 diabetes; specifically, the experiences perceived as meaningful and significant

Paper III To investigate and compare the illness perception and self-management among women and men with type 2 diabetes in Thailand, to examine the association between illness perception and self-management, and to investigate the psychometric properties of the translated instruments

Paper IV To examine the illness perception and self-management of Thai people with diabetes according to their socioeconomic status, as defined by income and educational level

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Design

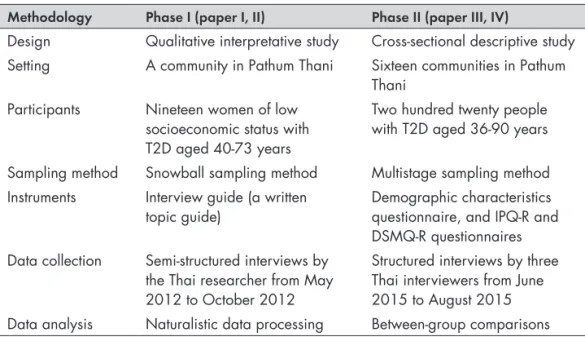

This thesis was conducted using both a qualitative and quantitative methodological approach that comprised four studies, directed towards people with T2D in Pathum Thani province, Thailand. The investigations contained two phases: phase I (paper I, II) and phase II (paper III, IV) (see table 1).

Phase I was conducted using a qualitative interpretative approach. It was an explorative study inspired by the principle of naturalistic inquiry set forth by Lincoln and Guba (1985). This research approach is considered useful for gaining insight into participants’ subjective and multiple realities, which are assumed to be constructed in a specific sociocultural context in which the participants engage (Guba & Lincoln, 1982; Owen, 2008). These realities can be explored through the interpretation or the plausible inferences of the entity of participants’ truth existing in their natural context (Guba & Lincoln, 1982; Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Owen, 2008).

Phase II was carried out using a cross-sectional descriptive study (Mann, 2003). It was applied to capture the information from people with diabetes living in a suburban region in Thailand. The cross-sectional design was assumed to be appropriate for investigating multiple outcomes of interest and may also be used to infer the influences of social factors on individuals at the time of measurement. This design was considered the best way to determine the various aspects of illness perception and self-management strategies, which were measured at one time.

Using both qualitative and quantitative methodologies was assumed to increase the knowledge and to provide nuances concerning the study population.

Table 1. Description of the investigations included in the present thesis

Methodology Phase I (paper I, II) Phase II (paper III, IV)

Design Qualitative interpretative study Cross-sectional descriptive study Setting A community in Pathum Thani Sixteen communities in Pathum

Thani Participants Nineteen women of low

socioeconomic status with T2D aged 40-73 years

Two hundred twenty people with T2D aged 36-90 years Sampling method Snowball sampling method Multistage sampling method Instruments Interview guide (a written

topic guide) Demographic characteristics questionnaire, and IPQ-R and DSMQ-R questionnaires Data collection Semi-structured interviews by

the Thai researcher from May 2012 to October 2012

Structured interviews by three Thai interviewers from June 2015 to August 2015 Data analysis Naturalistic data processing Between-group comparisons

Setting

The study areas in phase I and II were located in Pathum Thani province, Thailand, as stated. This suburban province comprises 1,005,760 inhabitants (women 52.5% and men 47.5%) and most of them are Buddhist (94.7%) (Pathum Thani Provincial Health Office, 2013). Most residents work in the industrial sector (71.1%). The average income of the people in this province was ranked in 2014 as the third highest in the country (11,024 THB/month, approximately 315 USD/month), and the percent of overall unschooled people in Thailand was 4.7% (Ministry of the Interior, 2014).

Both public and private healthcare facilities provide different levels of healthcare in this province. The ratio between physicians by population in 2012 (1 : 2,330 population) was higher than the national standard ratio (1 : 6,000 population) (Pathum Thani Provincial Health Office, 2013). All Thai citizens can access public healthcare services with free essential treatment costs depending on the kind of health insurance schemes that the people possess, such as civil servants’ medical benefits, social security, or the universal coverage scheme. On the other hand, people have to pay for the complete cost when using services at private hospitals or other public hospitals that are not specified with their preferential treatment card. The setting areas in this study are the responsibility of the Health Promoting Hospitals (HPHs), a sub-district healthcare unit that provides primary care for 1,000 to 5,000 people. The HPHs deliver mainly promotive and preventive care

in cooperation with the Village Health Volunteers (VHVs), community inhabitants trained to promote health and that offer fundamental care. VHVs act as assistants to the staff and as mediators between the staff and the community residents. The HPHs also provide primary medical care, which is run by general practitioners (internal medicine physician) and the staff in terms of special clinics at the HPHs. The universal coverage scheme is also included in the HPHs’ services. The objective of the program is to provide universal access to essential healthcare for people living in the catchment areas, which is free for all necessary treatment at the HPH and the referral hospital.

Figure 2. A picture of the study area in phase I (with permission from the people in

the picture)

The area studied in phase I belongs to the Royal Irrigation Department (figure 2). This area consists of the people living in poor circumstances and others living in slightly better circumstances. All residents can live there without having any legal contract for renting. Thus, due to the imminent possibility of eviction, their living situation is quite uncertain. On the other hand, the area studied in phase II

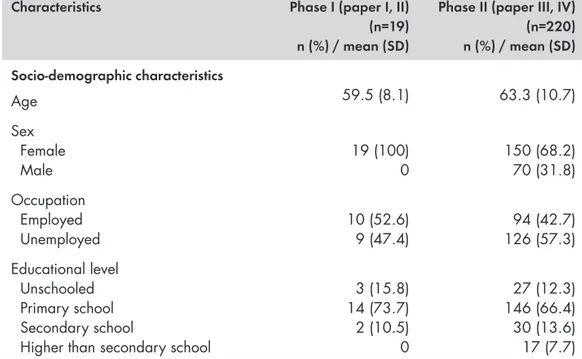

Participants

The participants in both phases I and II were adults living in the society, not hospitalized, that had T2D, and all of them were Buddhists. The eligible criteria for participation in this study were: (1) Thai citizens that could converse in the Thai language, (2) diagnosed with T2D by a physician for at least one year, and (3) taking an oral anti-diabetic agent, insulin injection, or both until the day of the interview. People with diabetes admitted to hospitals at the time of the data gathering or those whose houses could not be found by the interviewers were excluded from the study.

In phase I, only women were investigated, since the prevalence of diabetes among Thai women is higher than that of men (Thonghong et al., 2013), although a few men with diabetes were living in the setting area. Nineteen women with T2D were contacted and all of them agreed to participate in the research. Their age ranged between 40 and 73 years (mean age: 59.5 years). In phase II, 220 persons both women and men participated, corresponding to 46% of the total population diagnosed with diabetes that were contacted (n=478 persons), with an age range between 36 and 90 years (mean age: 63.3 years).

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of the participants in the present thesis

Characteristics Phase I (paper I, II)

(n=19) n (%) / mean (SD)

Phase II (paper III, IV) (n=220) n (%) / mean (SD) Socio-demographic characteristics Age 59.5 (8.1) 63.3 (10.7) Sex Female Male 19 (100)0 150 (68.2)70 (31.8) Occupation Employed Unemployed 10 (52.6)9 (47.4) 126 (57.3)94 (42.7) Educational level Unschooled Primary school Secondary school

Higher than secondary school

3 (15.8) 14 (73.7) 2 (10.5) 0 27 (12.3) 146 (66.4) 30 (13.6) 17 (7.7) (Table 2 continues on next page)

Characteristics Phase I (paper I, II) (n=19) n (%) / mean (SD)

Phase II (paper III, IV) (n=220) n (%) / mean (SD) Illness-related information

Duration of illness 9.2 (6.3) 9.7 (7.5)

Current treatment Oral anti-diabetic agent Oral pills and insulin injection Oral pills and alternative medicine

12 (63.2) 3 (15.8) 4 (21.1) 183 (83.2) 16 (7.3) 21 (9.5) Preferential treatment

Universal coverage scheme Civil servants’ medical benefits Social security Self-payment 14 (73.7) 1 (5.3) 3 (15.8) 1 (5.3) 173 (78.6) 22 (10.0) 15 (6.8) 10 (4.5) Ordinary health service use

Health Promoting Hospital Other public hospitals Private hospital Pharmacy 8 (42.1) 6 (31.1) 4 (21.1) 1 (5.3) 109 (49.5) 94 (42.7) 17 (7.7) 0 Experience of symptoms of diabetes

complications* No Yes Hypoglycemia Severe hyperglycemia Amblyopia

Numbness of hands and feet Comorbidity

No Yes

Hypertension

Hypertension and other diseases+

Other diseases+ 3 (15.8) 16 (84.2) 9 (47.4) 2 (10.5) 1 (5.3) 12 (63.2) 5 (26.3) 14 (73.7) 10 (52.6) 4 (21.1) 0 53 (24.1) 167 (75.9) 17 (7.7) 22 (10.0) 75 (34.1) 123 (55.9) 46 (20.9) 174 (79.1) 60 (27.3) 103 (46.8) 11 (5.0) * The experience of symptoms of diabetes complications could be indicated by more than one symptom.

+ Other diseases included cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and renal disease.

Sampling methods

The snowball technique (Polit & Beck, 2010) was used to include the participants in phase I. The process began with two people, one over and one under the age of the retirement limit in Thailand (60 years), both suggested by the management of the HPH. Each interviewee was asked to suggest another neighbor with T2D. If that person was found to be ineligible, another recommendation was requested until an eligible individual was found.

In phase II, the multistage sampling method (Sedgwick, 2015) was used to select the HPHs. According to Sedgwick (2015), this sampling method is based on the hierarchical structure of natural clusters within the population. In this study, one random sample was selected at each stage at the following levels: district, sub-district, and HPH. All of the people with T2D within the catchment areas of the sampled HPH were invited to participate in the study. The sample size for this study was calculated according to the proportion of Thai people with diabetes and the desired level of precision at 0.05 (Naing, 2003).

Data collection

The data for phase I were collected from May to October 2012 and for phase II between June and August 2015. Different kinds of procedures were used to collect the data in this study. Semi-structured interviews (Polit & Beck, 2010) were conducted in phase I. All of the participants were encouraged to share their experiences in great depth and follow-up questions were asked to better understand their stories. The interview method using specific questionnaires was used in phase II by the three Thai interviewers, who had more than 10 years of experience interviewing people living in communities concerning the issues of health and illness. These interviewers were also trained to use the specific questionnaires of this study prior to the data collection and received weekly follow-up supervision. All of the interviews (phase I, II) took place at the participants’ house or a place suggested by them. Study details, confirmation of the confidentiality of all data, and how to withdraw from or participate in the study were explained to all of the participants before the interview began, and the consent form was signed when the participants agreed to participate in the study. For illiterate participants (3 persons in phase I and 27 persons in phase II), a thumbprint (a normal practice in Thai society) was made instead of a signature to denote agreement to participate. Each interview lasted between 40 and 90 minutes. In phase I, audiotapes of the conversation were made and transcribed verbatim in Thai and later translated into English. All of the data translations were rechecked by a bilingual language expert. In phase II, the participants were asked questions item by item through

the specific questionnaires. An explanation of each item was given on the basis of the discussion, which was agreed to by the team of the Thai researcher and interviewers. A re-interview was requested when omissions were found.

Instruments

An initial list of topics in the interview guide of phase I was generated through a literature review and previous qualitative studies. A trial of the initial questions was conducted with two women with T2D living in the community. Minor revisions as related to the trial were made as suggested by Polit and Beck (2010). Finally, there were the main open-ended questions as follows. How are your experiences, and your personal feelings and thoughts about life with diabetes? How have you handled your daily life activities since you became sick with diabetes? What has improved the way in which you handle the disease? What hindrances have you encountered?

In phase II, a demographic characteristic questionnaire developed by the team of researchers was used to describe the socio-demographic characteristics and illness-related information. The perceptions of life with T2D and self-management were obtained using two measurement tools: the revised illness perception questionnaire, the diabetic version (IPQ-R) developed by Moss-Morris et al. (2002), and the revision of the diabetes self-management questionnaire (DSMQ-R) developed by Schmitt et al. (2013). These instrumental tools were translated into the Thai language according to the suggestions from the World Health Organization (WHO) process of translation and adaptation of instruments (WHO, 2014). The main applications of this process include forward-backward translation among English and the Thai language by two bilingual experts, discussion within a team of researchers to resolve the inadequate or dissimilar concepts of the translation, and pre-testing the translated measurement with the target population.

Revised illness perception diabetic version questionnaire (IPQ-R)

The IPQ-R questionnaire was used to measure how people perceive their life with diabetes and respond to and cope with their life situation. This measurement is divided into three main sections: identity, diabetes perception, and causal sections. The identity section is focused on the participants’ beliefs about the 14 common symptoms that are associated with diabetes, with a yes/no response. The diabetes perception section consists of 38 items divided into seven subscales that present

(the original name of the subscale was “timeline”), consequences, personal control, treatment control, illness coherence, fluctuating symptoms (original name of the subscale was “timeline cyclical”), and emotional representation. In this study, the terms “timeline” and “timeline cyclical,” which refer to the duration of the illness and recurrences of the disease, were during the analysis process switched to “acute or chronic conditions” and “fluctuating symptoms.” Lastly, the causal section focuses on the participants’ views about the possible causes of their diabetes, which comprise 18 items. A five-point Likert scale—1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (neither agree nor disagree), 4 (agree), or 5 (strongly agree)—was applied to both the diabetes perception section and the causal section. High scores on each subscale of the diabetes perception section represented strongly-held or positive beliefs.

Revised diabetic self-management questionnaire (DSMQ-R)

The DSMQ-R measurement tool was used to access the participants’ self-care activities over the previous 8 weeks. This instrument comprises 27 self-care activities. The first 20 items are developed for non-insulin-treated participants and all 27 items are used for insulin-treated participants and are divided into a sum scale (20 or 27 items) and four subscales: glucose management, diet control, physical activity, and healthcare use. A four-point Likert scale—0 (does not apply to me), 1 (applies to me to some degree), 2 (applies to me to a considerable degree), and 3 (applies to me very much)—was used to measure each item. The scores for the sum scale and each subscale were calculated according to the formula in the scoring guide (Schmitt et al., 2013), which ranged between 0 and 10. High scores indicated more effective self-care.

Measurement of the psychometric properties of the instruments

The psychometric properties of the IPQ-R and the DSMQ-R instruments in this study were tested for content validity, inter-rater reliability, internal consistency reliability, and test-retest reliability according to the suggestion of Cook and Beckman (2006). The content validity was tested by three experts: two nursing Thai teachers with experience in diabetes research, and one advanced practice nurse (APN) specializing in diabetes in Thailand. The experts made comparisons with each item between the English and Thai translated instruments and used a checklist with a yes/no format for their agreement or disagreement. In addition, they also suggested improvements. Inter-rater reliability was tested with three people with T2D, and each person was interviewed three times with the same instrument (each time by a different interviewer). The test aimed to develop a consistent understanding between the three interviewers concerning the key concept of each

item in the instrument. Internal consistency reliability was measured with a pilot study of 30 people with T2D. These people were interviewed by the team of interviewers. A re-interview was conducted two weeks after the initial interview in order to investigate the test-retest reliability.

Data analysis

The data analysis of the qualitative approach in phase I was inspired by naturalistic data processing (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) that established two main steps: induction and construction. The inductive method was used to combine the narratives of the participants’ experiences into various categories, followed by the process of construction, which formulated more abstract meaning through generating categories. According to Shenton (2004), four researchers independently analyzed and identified categories in order to ensure trustworthiness. The process was begun by reading and rereading the narrative materials and then all units of meaningful information were captured. The grouping of homogeneous content and differentiating heterogeneous content according to meaning were carried out, along with rechecking the original data. All of the narrative texts within the groups were considered and interpreted in order to build an abstract meaning and then subthemes and themes emerged. This step of subtheme and theme construction was generated with the collaboration of all researchers. Several discussions and revisions were conducted in order to reach agreement and to manage the pre-understanding of individuals. Ultimately, the main findings of the data analysis were shown to and discussed with the participants in order to ensure that the researchers correctly understood what the participants meant.

The quantitative data in phase II were analyzed using SPSS for Windows version 21.0 (IBM corp., 2012) at the significance level of 0.05. In paper III, data were analyzed and compared between women and men, and paper IV compared subgroups according to the participants’ socioeconomic status, which was defined by income and educational levels. The data on the low- and high-income and low- and high-education groups were used for the analysis. The national poverty line estimated in 2014 (2,835 THB/person/month, approximately 81 USD) (National Statistical Office in Thailand, 2016) was used as a cut-off point for income groups. The educational subgroups were divided according to the participants’ maximum educational level—individuals unschooled and completing education at the primary school were defined as the low-education group and the

Analysis of the psychometric properties of the instruments

The content validity index (CVI) was used to calculate content validity (Pongwichai, 2013). Inter-rater reliability was computed using the percentage of the consistency of each three sets of questionnaires. Internal consistency reliability was examined using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (Pongwichai, 2013). The test-retest reliability was analyzed by testing the association between the scores from the initial interviews and the scores from the re-interviews (two weeks after the initial interview). Pearson correlation coefficient or the Spearman correlation coefficient was used depending on the nature of the data distribution (Kellar & Kelvin, 2013).

Statistical analysis

The categorical demographic characteristics of the participants were computed by frequency and percentage. Median and interquartile were calculated for the continuous demographic characteristics due to the skewed nature of the data. In comparing the differences in the demographic characteristics between the two groups, the chi-square test was used for the categorical data and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for testing the continuous variables (Kellar & Kelvin, 2013).

The IPQ-R diabetic version questionnaire was analyzed according to each section: identity, diabetes perception, and causal section. The experienced symptoms since having T2D were presented using percentages. The identity section was computed with the sum of yes-rated symptoms and the mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated. Each subscale of the diabetes perception section was computed using mean and SD. Both the mean scores of the identity and the diabetes sections among the two groups were tested for the differences using an independent samples t test or the Mann-Whitney U test depending on the nature of the data distribution (Kellar & Kelvin, 2013). The causal section was analyzed using separate items. Each item in the causal section was grouped into a dichotomous variable according to the suggestion in the scoring guide for the IPQ-R questionnaire (Moss-Morris et al., 2002) (scores 1, 2, 3 meant disagreed and scores 4, 5 meant agreed with the item that might have been the cause of T2D) and was presented as a percentage.

The DSMQ-R questionnaire, both the sum scale and subscales, was analyzed for mean scores and SD, and the different mean scores between the groups were compared using the independent samples t test or the Mann-Whitney U test (Kellar & Kelvin, 2013).