DISSERT A TION: MIGR A TION, URB ANIS A TION, AND SOCIET AL C HAN GE C HRIS TIN A HANSEN MALMÖ UNIVERSIT

SOLID

ARIT

Y

IN

DIVERSIT

Y

CHRISTINA HANSEN

SOLIDARITY IN DIVERSITY

Activism as a Pathway of Migrant Emplacement

in Malmö

Dissertation series in

Migration, Urbanisation, and Societal Change

Doctoral dissertation in International Migration and Ethnic Relations Department of Global Political Studies

Faculty of Culture and Society

Information about time and place of public defence, and electronic version of the disser-tation: http://muep.mau.se/handle/2043/29782

© Copyright Christina Hansen, 2019

Cover: TZUNAMI – Aida Samani and Ossian Theselius

ISBN 978-91-7877-016-8 (print) ISBN 978-91-7877-017-5 (pdf) Holmbergs, Malmö 2019

Malmö University, 2019

Faculty of Culture and Society

CHRISTINA HANSEN

SOLIDARITY IN DIVERSITY

Activism as a Pathway of Migrant Emplacement

in Malmö

Dissertation series in Migration, Urbanisation, and Societal Change

1. Henrik Emilsson, Paper Planes: Labour Migration, Integration Policy and

the State, 2016.

2. Inge Dahlstedt, Swedish Match? Education, Migration and Labour Market

Integration in Sweden, 2017.

3. Claudia Fonseca Alfaro, The Land of the Magical Maya: Colonial

Lega-cies, Urbanization, and the Unfolding of Global Capitalism, 2018.

4. Malin Mc Glinn, Translating Neoliberalism. The European Social Fund and

the Governing of Unemployment and Social Exclusion in Malmö, Sweden,

2018.

5. Martin Grander, For the Benefit of Everyone? Explaining the Significance

of Swedish Public Housing for Urban Housing Inequality, 2018.

6. Rebecka Cowen Forssell, Cyberbullying: Transformation of Working Life

and its Boundaries, 2019.

7. Christina Hansen, Solidarity in Diversity: Activism as a Pathway of Migrant

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments ... v

Main activist groups featured in the thesis ... ix

Glossary and abbreviations ... x

List of Figures ... xiv

PREFACE ... xvi

INTRODUCTION ... 1

Aim and research questions ... 11

The dilemma of categorising ... 15

‘The activist’ ... 16

‘The migrant’ ... 17

Using the activist lens ... 23

Emplacement ... 26

Previous research and this thesis’ contributions ... 28

Outline of the thesis ... 32

1 LOCATING ACTIVISM ... 39

Activism in cities ... 43

The construction of ‘us’ ... 45

The extra-parliamentary left in Sweden ... 48

Activist groups in Malmö ... 56

What cities can teach us ... 68

Neoliberalism and urban restructuring ... 73

Immigration and segregation ... 89

Border enforcement and the city as refuge ... 92

A locus of power ... 101

Where there is power there is resistance ... 103

Activism as politics ... 104

The creation of something new ... 108

Activism and public space ... 112

Solidarity ... 115

Commoning ... 122

Activism as city-making ... 126

2 DOING FIELDWORK ‘AT HOME’ ... 129

Creating the field ... 130

Multi-sited and multi-sighted fieldwork ... 131

Choosing the place ... 133

Methods, material, and fieldwork ... 133

Biographical interviews ... 137

Empirical data and the analytical process ... 138

Reflections on the academic-activist relationship ... 139

Being an ‘insider’ ... 140

Emotions and positionalities ... 142

Ethical considerations ... 144

3 NOT ALL CITIES HAVE A MÖLLAN ... 147

From working class pride to slum ... 156

The upgrading of Möllevången ... 159

Unregulated labour ... 168

A changing commercial infrastructure ... 172

Increased rents and homeownership dwellings ... 175

Characteristics of the activist scene ... 178

Activism against gentrification and segregation ... 180

Narrating Möllevången ... 187

Politicised boundary making ... 196

Consolidating Möllevången as anti-racist ... 200

4 THE ACTIVISTS ... 205

What is activism and who is an activist? ... 209

Privileged actors? ... 223

Finding scapegoats ... 235

Creating new norms ... 238

Negotiating identities and boundaries ... 241

5 ACTIVISM AND ENFORCED DEPORTATION ... 247

Stop REVA ... 250

Preparations ... 253

The Stop REVA demonstration, 9 March 2013 ... 257

Activists and mainstream media ... 259

Online-offline activities ... 263

Awareness-raising activities ... 268

Social and political frictions ... 273

Stress and burnout ... 277

Local anchoring and legitimacy ... 278

Trapped in direct action ... 280

Civil disobedience, direct action, and unlawful activities ... 282

Challenges, ambivalences, and conflicts ... 290

Solidarity vs. charity ... 297

‘It could be me’ ... 306

6 EMBODIED SOLIDARITY ... 310

Creating friendships ... 312

The role of friendship in activism ... 314

Networks of connected friends ... 318

Material and emotional effects ... 319

The challenge of inequality in friendship ... 322

Creating alternative structures ... 325

Self-organising as key ... 335

Are there ‘safe spaces’? ... 340

Migrants becoming activists ... 342

Migrants’ political socialisation ... 349

Forging new social relations ... 354

7 COLLECTIVE ACTION ... 360

Creating alliances ... 365

Exploring common grounds ... 368

The eviction ... 384

Challenges, ambivalences, and conflicts ... 388

Commoning in relations of inequality ... 391

Creating mass mobilisations ... 398

‘Kämpa Showan’, 9 March 2014 ... 399

One week later, 16 March 2014: ‘Kämpa Malmö’ ... 408

Half a year later: ‘Neo-nazis out of Malmö’ ... 415

Challenges, conflicts, and police brutality ... 429

Collective struggles and the meaning of space ... 434

8 WHAT DIFFERENCE DOES ACTIVISM MAKE? ... 441

Perceptions of success and failure ... 443

Producing new spaces ... 447

Connecting people, places, and struggles ... 450

What is to be done? ... 453

Farewell Möllevången? ... 456

CONCLUSIONS ... 459

Creating pathways of emplacement ... 474

Contributions and further research ... 476

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, I wish to thank my supervisor at Malmö Uni-versity, Maja Povrzanović Frykman, who has, from the start, been enthusiastic about my project. To have such a supportive, sharp-eyed, and passionate academic role model is rare, and it has been decisive for my own intellectual development and for the accom-plishment of this thesis. I am grateful beyond words for her guid-ance. Her commitment to the small yet vital details of the human experience never ceases to amaze and inspire me. I would also like to say a big and warm thank you to Nina Glick Schiller, who, in her position as co-supervisor, has shown great support in reading and commenting on my drafts and giving encouragement on my chosen topic. I am grateful for our last—and very important— theoretical discussions, which helped me pull my thesis together.

I am deeply indebted to a further number of scholars who have read and provided valuable comments on the manuscript at differ-ent stages of the research and writing process: Margit Mayer, who critically and constructively commented on my final seminar draft; Carina Listerborn, who read and commented on my thesis draft at several different stages; Stellan Vinthagen, who carefully read and generously commented on my mid-term draft; Carl Cassegård, Di-ana Mulinari, Victor Lundberg, Håkan Thörn, Peter Hallberg, Ronald Stade, Peter Parker, Garbi Schmidt, Jonas Alwall, Christina Johansson, Anna Lundberg, Anders Hellström, Stefan Nyzell, Majken Jul Sørensen, Tapio Salonen, Margareta Popoola, Per-Markku Ristilammi, and Stig Westerdahl have all provided me with insightful feedback.

The manuscript has also benefited greatly from the informal yet careful reading and constructive criticism of a number of friends and colleagues: Ulrika Andersson, Måns Lundstedt, Katja Jansson, Jonathan Pye, Mattias Wahlström, Johan Pries, Anders Wester-ström, Julia Böhler, Lena Ek, Fanny Mäkelä, and Maja Sager. Thank you also to Cathrin Wasshede for our lunch conversations and constructive suggestions that inspired my own writing.

I wish to thank all my colleagues at the Department of Global Political Studies and the Department of Urban Studies at Malmö University, especially those within the research programme Migra-tion, Urbanisation and Societal Change, which was an inspiring and supportive research environment and invaluable for my intro-duction to academia and my well-being as a doctoral student. Spe-cial thanks to my peers and fellow PhD students who have read early as well as later drafts at our formal seminars and courses and provided me with thoughtful comments: Martin Grander, Claudia Fonseca, Henrik Emilsson, Malin Mc Glinn, Ioanna Tsoni, Mika-ela Herbert, Ingrid Jerve Ramsøy, Rebecka Forsell, and Jacob Lind. Also, thanks to guest PhD student Noura Alkhalili. Special thanks go to Martin Grander, who provided me with statistics on tenure in Möllevången. Thank you also to Maria Persdotter for her feed-back as discussant at the PhD retreat.

Needless to say, I assume full responsibility for all remaining er-rors of fact and interpretation.

I want to thank everyone I met at the Department of Sociology and Work Science at Gothenburg University who made my several-months stay there as a guest PhD student truly positive. Beyond the generosity shown by Stellan Vinthagen and Håkan Thörn, who warmly welcomed me and made my stay there possible in the first place, I owe a big thanks to Pia Jacobson, who cared for me ad-ministratively and comradely. I also owe thanks to colleagues at the School of Global Studies at Gothenburg University who offered me office space while I was temporarily living in Gothenburg at an earlier stage of my research; especial thanks to Carolina Valente Cardoso, Vanessa Martin, Minoo Koefoed, and Wassim Ghantous. I would further like to thank Magnus Johansson, who involved me in his courses and provided me with the opportunity to teach

about my own research and related topics. Martin Reissner and Frida Hallqvist have supported me administratively in my work, for which I am thankful. Thank you also to Magnus Ericson and Maria Brandström for your support.

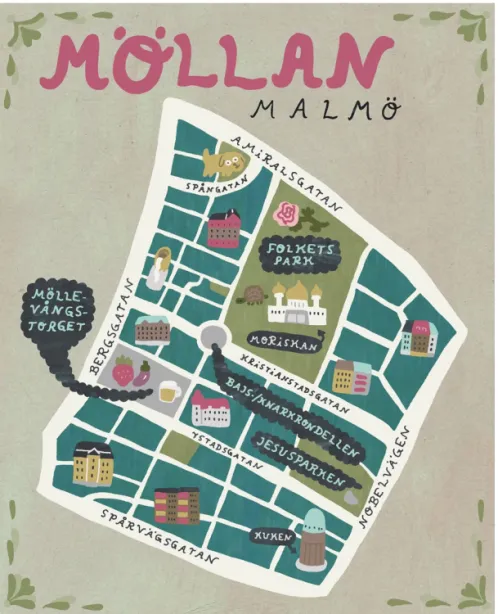

A big thanks to TZUNAMI—Aida Samani and Ossian These-lius—for letting me use their brilliant illustration of Möllevången for the cover of this thesis as well as to RåFILM Media Collective for letting me reuse it after spotting it on their promotional poster. A big thanks to Nanna Johansson—Swedish cartoonist and radio presenter—for letting me use her illustration of Möllevången to ge-ographically guide the reader in this urban ethnography. Thanks also to Jonathan Pye, Victor Pressfeldt, and Lars Brundin for let-ting me use their photographs. Thanks a million to Eric Bergman who did a fantastic job proofreading this thesis.

My gratitude also goes to my flatmates in Malmö during the pe-riod I was a pregnant doctoral student: Moa, Johan, and Sara— thanks for abiding with me. And my dear, loving friends—Katja, Lena, Weronika, Moza, Ulrika, Nura, Wellington, Lucas, Linda J., Maja, Linda S., Frida, Michaela, Mathias, Nina, Sara, Rosa, Tora, Lisa, David, César, Gloria, Nomi, and Henning—the world would be a truly dull place without you. My dear closest family—my mom Birgitta, dad Jørgen, and sister Victoria—although you ha-ven’t really known what I have been up to these past few years, your unconditional, practical, and financial support of my wishes and decisions (ever since I can remember) have been decisive for finishing this thesis.

My dear partner Jonathan Pye, words are not enough to express my gratitude for your kind and patient support, which was crucial for my research and writing. I appreciate our conversations about politics and activism, which have inspired me. I love you so much and I wish that we grow old together. Our daughter, who was born when three out of my four years of doctoral studies were completed, helped take my mind off of work during the writing-up of this dissertation. When you, Atla, came into my life, this grim and unjust world was filled with beauty.

Last but not least, I owe my most sincere gratitude to the activ-ists I’ve met in the course of my fieldwork and life, who invited me

into their political lives and shared their experiences of activism and the causes that mean so much to them. I hope I do justice to their efforts, their missions, and the generosity they showed me, although I am well aware that I might not have focused on, or written about, the perspectives that the activists themselves think of as the most important. To show my gratitude, I dedicate this book to all activists who have directly contributed to it and to all activists who have indirectly contributed to my project: for your relentless refusal to accept that the way things are is how they have to be.

Main activist groups featured in the thesis

Aktion mot deportation (Action Against Deportation): https://www.facebook.com/aktionmotdeportation/ Allt åt alla (Everything for Everyone):

https://alltatalla.se/malmo

Asylgruppen (The Asylum Group): http://asylgruppenimalmo.se/

Kontrapunkt (Counterpoint, a social centre): http://www.kontrapunktmalmo.net

Skåne mot rasism(Scania Against Racism): https://www.facebook.com/skanemotrasism/

Glossary and abbreviations

AFA Antifascist Action

Amalthea Bokkafé A leftist bookshop and café in Möllevången Autonomous Activists involved in radical, left-wing,

ex-tra-parliamentarian groups

Autonomt motstånd Autonomous Resistance: activist group that existed in Malmö (1997–2003) and im-portant precursor to Allt åt alla, formed in 2009

Asylstafetten The Asylum Relay: a recurrent pro-asylum march taking place every summer since 2013, starting from Malmö and goes to dif-ferent, politically defined places (e.g. Stock-holm, Almedalsveckan in Visby, Åstorp refugee detention centre)

COP 15 Conference of the Parties, 2009 UN Cli-mate Change Conference in Copenhagen COP 21 Conference of the Parties, 2015 UN

Cli-mate Change Conference in Paris

‘Dublin’ ‘Dublin’ refers to a person who applied for asylum in Sweden, but whose application was rejected by the Swedish Migration Board on the basis that the asylum seeker was already registered in another country in the European Union (EU). The Dublin Reg-ulation states that every person seeking asy-lum should do so by filling in an applica-tion in the first country of arrival in the EU (which, for many migrants, are the coun-tries in Southern and Eastern Europe); in 2014, minors were exempted from this rule

(Regulation EU No 604/2013). Many peo-ple subject to the Dublin Regulation stay in Sweden undocumented for 18 months or more. After that period, ‘Dublins’ may seek asylum anew in Sweden

Ensamkommandes

förbund The Unaccompanied’s Association: a for-mal organisation made up of young refu-gees for young refugees. It was formed in May 2013 in Malmö and later spread to 17 other towns and cities in Sweden

ESF European Social Forum

FARR The Swedish Network of Refugee Support Groups (Flyktinggruppernas Riksråd): an umbrella organisation for individuals and groups working to strengthen the right of asylum

Fika ‘A coffee and cake break’ together with col-leagues, friends, or family

Flyktingfängelse ‘Refugee prison’: the official name for mi-grants’ and refugees’ detention centres in Swedish is flyktingförvar (refugee custody),

förvar literally meaning ‘storage’. Activists

use the term ’refugee prison’ in order to in-form the general public of how it resembles a prison and to not allow language to dis-tort reality by calling it something different Glassfabriken Ice Cream Factory: an anarchist café in

Möllevången (2001–2015)

G8 Group of Eight: the most powerful indus-trial nations (reformatted as G7, the Group of Seven, in 2014).

Knarkrondellen The Drug Roundabout: the standard, popu-lar name for a roundabout in Möllevången (which formally has no name)

Kämpa Malmö An imperative meaning ‘Keep on fighting, Malmö’, literally translated as ‘Fight,

Malmö’: the main slogan and term used to describe the large-scale anti-nazi protests in 2014

LGBTQ Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer Mangla A radical class struggle-oriented feminist

group

Möllan Popular name for Möllevången

Möllevångsgruppen The Möllevången Group, formed in 1994: important predecessor to the Möllevången Festival and Kontrapunkt

Nassar Slang term for nazister (nazis) NGO Nongovernmental organisation Nyanländas Röster Newcomers’ Voices: an activist group

formed by and for newcomers in Malmö OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development

Punkväggen The Punk Wall (sometimes called the Crust Wall) is the popular name for the north-eastern corner of the square

Möl-levångstorget, where punks used to hang out in the 1990s and beginning of the 2000s

PUT Permanent residence permit (permanent uppehållstillstånd)

REVA Legally secure and efficient work for en-forcing deportations(Rättssäkert och

effek-tivt verkställighetsarbete): a joint

adminis-trative project 2009–2014 between the Swedish police, the Prison and Probation Service, and the Swedish Migration Agency (Migrationsverket)

RWM Refugees Welcome Malmö

Skåne/Scania The southernmost county of Sweden, also called Skåne County in English

SDL Swedish Defence League

SEK Swedish Kronor

SMO Social Movement Organisation

Sorgenfrilägret A Roma settlement in Malmö (2013–2015) located in Norra Sofielund, Malmö

SOU Statens offentliga utredningar (‘State public reports’), reports appointed and convened by the Government of Sweden

SUF The Anarchosyndicalist Youth Federation (Syndikalistiska Ungdomsförbundet) SYLF Support Your Local Feminist: a radical

feminist group

Tältaktionen The Tent Action: a protest camp lasting six weeks in spring 2014. It aimed to protest the deportation of four asylum seekers whose applications were rejected and to show solidarity with, and raise awareness of, other rejected asylum seekers in the same situation

Vänner/Friends The non-homogenising term used to refer

to people in precarious legal conditions connected to the activist scene: undocu-mented people, asylum seekers, and Roma migrants, whom the activists assist in dif-ferent ways and create alliances with to forge joint struggles

Ung vänster The Young Left of Sweden: the youth or-ganisation of the Swedish Left Party WTO World Trade Organisation

List of Figures

11. Möllevången by cartoonist Nanna Johansson. xxiii 2. Sticker on a bench on the square Möllevångstorget

saying, “We put out the fires that fascism has lit”,

signed Antifascist Action, May 2016. 203 3. The 90-meter graffiti wall (made legal in 2013)

along Folkets Park next to Knarkrondellen with the painted words, “Anti-fascism is self-defence”,

16 March 2014. 203

4. Light installation in Knarkrondellen on which someone has scribbled the text, “If we all are just nice and we are nice to each other everything will turn out fine… Except nassar [nazis]. Give

them shit. Fuck the fascists!”, December 2013. 204 5. Protestor wearing a mask with the face of Justice

Minister Beatrice Ask, 9 March 2013. Photo by

Jonathan Pye. 308

6. Masked protesters with cardboard signs, 9 March

2013. Photo by Jonathan Pye. 308

7. Leaflet announcing the Stop REVA demonstration

in Malmö. 309

8. Poster announcing the Solidarity Carnival Against

REVA. 309 9. Activists protesting their own deportation, standing

by the monument the Glory of Labour on the square

Möllevångstorget, 11 February 2014. 359

1 All photographs taken by the author unless otherwise stated.

List of Figures

11. Möllevången by cartoonist Nanna Johansson. xxiii 2. Sticker on a bench on Möllevångstorget saying, “We put out

the fires that fascism has lit”, signed Antifascist Action Malmö, May 2016....199

3. The 90-meter graffiti wall (made legal in 2013) along Folkets Park next to Knarkrondellen with the painted words, “Anti-fascism is self-defence”, 16 March 2014....199

4. Light installation in Knarkrondellen on which someone has scribbled the text, “If we all are just nice and we are nice to each other everything will turn out fine… Except nassar [na-zis]. Give them shit. Fuck the fascists!”, December 2013....200 5. Protestor wearing a mask with the face of Justice Minister

Be-atrice Ask, 9 March 2013. Photo by Jonathan Pye....302 6. Masked protesters with cardboard signs, 9 March 2013.

Pho-to by Jonathan Pye....302

7. Leaflet announcing the Stop REVA demonstration in Malmö....303

8. Poster announcing the Solidarity Carnival Against RE-VA....303

9. Activists protesting their own deportation, standing by the monument the Glory of Labour on Möllevångstorget, 11 Feb-ruary 2014....352

10. Activists stand together with Roma migrants to protest their eviction from the Sorgenfri settlement, 1 November 2015. Photo by Victor Pressfeldt, first published in Brand (Allt åt al-la Malmö 2015)....390

10. Activists stand together with Roma migrants to protest their eviction from the Sorgenfri settlement, 1 November 2015. Photo by Victor Pressfeldt, first

published in Brand (Allt åt alla Malmö 2015). 397 11. Evicted dwellers of the Sorgenfri settlement

and Malmö activists watching the film Taikon during their sit-in outside the City Council Hall. Photo by Lars Brundin, first published in

Sydsvenskan (Chukri 2015). 397

12. The square Möllevångstorget viewed from the monument the Glory of Labour during the Kämpa

Showan demonstration, 9 March 2014. 439

13. Portrait of Showan with the hashtag #kämpashowan painted on a parking garage (P-Huset Anna) in

central Malmö, 16 March 2014. 439

14. Möllevångstorget 16 March 2014. People

gathering to join the demonstration ‘Kämpa Malmö

— Antifascism is self-defence’. Photo by Jonathan Pye. 440 15. Blood on the asphalt. Mass blockade of the

Party of the Swedes in Limhamn, 24 August 2014. 440

xv

11. Evicted dwellers of the Sorgenfri settlement and Malmö activ-ists watching the film Taikon during their sit-in outside the City Council Hall. Photo by Lars Brundin, first published in

Sydsvenskan (Chukri 2015)...390

12. Möllevångstorget viewed from the monument the Glory of Labour during the Kämpa Showan demonstration, 9 March 2014....431

13. Portrait of Showan with the hashtag #kämpashowan painted on a parking garage (P-Huset Anna) in central Malmö, 16 March 2014....431

14. Möllevångstorget 16 March 2014. People gathering to join the demonstration ‘Kämpa Malmö — Antifascism is self-defence’. Photo by Jonathan Pye....432

15. Blood on the asphalt. Mass blockade of the Party of the Swedes in Limhamn, 24 August 2014...432

PREFACE

I moved to Malmö,2 located in the southernmost part of Sweden,

in 2004 to take an undergraduate course at the recently founded university as the first one in my family to acquire higher education. I moved from Båstad, a rural town with approximately 5,000 in-habitants located about an hour’s drive north of Malmö. I had vis-ited Malmö in my teens and while most of my friends from school moved to the two larger cities in Sweden—Stockholm and Gothen-burg—or abroad to cities such as Copenhagen, London, and even Sydney to work, I found Malmö attractive for its grassroots politi-cal activities and international character, with residents from all over the world and stores with foreign foods to be found around the centrally located neighbourhood of Möllevången. I used to buy chickpeas and tahini when visiting the city and bring them home to Båstad where they went old in the fridge because I didn’t know how to prepare them. After having lived in Malmö for more than ten years, hummous is now a natural part of my everyday food habits.

“Malmö was called Sweden’s Chicago at the time”, as one of my schoolmates remembers Malmö’s reputation in the 1990s, “a place that was kind of lawless”. However, despite the city’s bad reputa-tion, poverty, and high crime rates, most of my friends from school back in Båstad eventually moved to Malmö too. Everything they wanted in terms of education, leisure, and work opportunities—as

2 As the third largest city in Sweden, Malmö has a population of 335,000 inhabitants, compared

with Gothenburg’s 566,000 and Stockholm’s 950,000 (SCB 2018c), and is located in the country’s southernmost county of Scania. Malmö is connected by the Øresund Bridge with Denmark’s capital Copenhagen.

nurses, restaurant staff, or in the cultural sector—they found there despite its relatively small size and, importantly, living there was cheaper compared to Gothenburg and Stockholm.

Upon moving to Malmö, I immediately got to know people with Latin American backgrounds: political refugees, children of politi-cal refugees, and those who had moved to Malmö and Sweden on-ly recenton-ly to live with their Swedish partners whom they had met in their home countries.3 These people constituted my first social

network in Malmö and some of them became close friends. We had the Spanish language in common and an interest in politics and music. In fact, moving to Malmö meant regaining the Spanish that I had learnt fluently as a child—while growing up in Spain un-til the age of ten—but which I had lost during my teenage years due to not being able to practice it in the small town in which I then lived. It was the ‘non-Swedishness’ of Malmö that instantly made me like the city, even to feel ‘at home’ in a sense that I had never experienced in the various places and different countries that I had lived in while growing up. I moved into a studio (sublet, short-term contract) flat in Möllevången. Gradually, I became ac-quainted with the extra-parliamentarian political circles connected to the neighbourhood. Just living in the area made me somehow feel ‘political’. It was easy to ‘consume’ politics and be a partici-pant (without being an activist) in the political activities taking place in the city and especially in the neighbourhood of Möl-levången. I attended Kvinnocafét (the Women’s Café), which was arranged every other week in 2004 by a group of activists affiliated with The Möllevången Group,4 where we met over coffee and

cakes to learn and talk about feminism.

Activists from other Swedish cities perceive Malmö as having a very distinct activist scene. One described it as more continental and polarised. “The left is more radical; it looks more like the ac-tivism in Denmark and Germany.” Another activist said that there is always something going on in Malmö compared to Stockholm;

3 It became quite common for Swedish middle-class youth born in the 1980s, after finishing high

school, to travel abroad to study or work while ‘exploring the world’, some of whome attended Swedish left-wing oriented colleges (folkhögskola) located abroad.

4 Möllevångsgruppen (The Möllevången Group) was one of the first important groups of activists in

people hand out leaflets in the streets and “even the local hair-dressers put up demo posters inside their windows saying ‘Anti-fascism is self-defence’”. A person who became an activist upon moving to Malmö, where she participated in a demonstration for the first time in her life, perceived the activism in Malmö as main-stream—meaning activism is conducted by ‘ordinary people’—and not as subcultural as in her city Umeå located in the north of Swe-den.

Among local activists, Malmö is called ‘Kärlekens huvudstad’ (the Capital of Love), expressed repeatedly on social media and daily speech. ‘Love’ here means radical love as articulated through resistance against racism, sexism, and inequality. A similar and re-lated expression circulating is ‘Motståndets huvudstad’(the Capital of Resistance), referring to the activist scene in the city. A third nickname is Crime City (original use in English), due to its reputa-tion as a crime-ridden city.5 We find many names for those we

love.

Malmö is indeed a place with a reputation. It carries associations of an industrial past and contemporary social problems such as crime, poverty, and segregation. Activists perceive Malmö through the lens of Möllevången as the centre of their experiential knowledge of the city and through it, they bring in new associa-tions, such as anti-racism, diversity, and a vivid political life. When talking about Malmö, many activists are actually talking about Möllevången. Activists are not only found in Möllevången, howev-er. Through their activities in different parts of the city, the activ-ists are trying to expand the space of Möllevången.

The activists I talked to have compared Möllevången to Nørre-bro in Copenhagen, Kreuzberg in Berlin, and even Exarcheia in Athens—iconic neighbourhoods characterised by a central location in their respective cities, affordable housing, ethnically diverse populations consisting largely of low-income households, the pres-ence of anti-racist and pro-asylum activism, and a high percentage of leftist voters in local and national elections. With a population

5 The nickname Crime City is related to the national and international image of Malmö as rough.

The local roller-derby team Crime City Rollers was founded in 2010 and a film was made about them in 2013: Crime City Love (Levin 2013).

of just over 300,000, it is safe to say that Malmö hosts one of the most, if not the most, vibrant and visible activist scenes in Sweden today.

But Möllevången is a complex space with a number of interact-ing and paradoxical currents and multiple stories are told of the place. Focusing on political struggles that arise in the context of such conditions, which can be thought of as an incubator for re-sistance, this thesis reveals frictions within the activist scene and Möllevången. The chapters that follow show how creating a politi-cal space may contribute to gentrification; how solidarity-based ac-tivities (i.e. acac-tivities based on horizontality that strive towards equality) may cover up and even reproduce relations of inequality; and how the construction of Möllevången as ‘anti-racist’ may pre-vent the revelation of the extensive unregulated labour force and the fact that abuse of racialised migrants occurs in the neighbour-hood. Notwithstanding the specificities of Möllevången, the con-flicts in the neighbourhood reach far beyond the place itself and its perceived boundaries and indeed the city of Malmö itself. These conflicts and contradictions are indicative of what is happening in many parts of Europe.

The voices that come forward in this thesis are only a few out of many politically engaged people living in and around Möllevången. I know I miss out on stories that would be worthwhile telling. My ambition was never to write an exhaustive story of activism in Möllevången, however. Drawing on a representative sample of ac-tivists, I want to convey the experiences of activism in Malmö and Möllevången that tell us something beyond the very place: how the particularities of a certain city, and even of a certain local neigh-bourhood, affected by global processes of restructuring, disposses-sion, and migration, have enabled this kind of activism. Activism helped me to trace the global processes that affect Malmö and to explain the ways in which the particular, historically embedded, local, socio-political dynamics are crucial for understanding the lo-cal responses to these processes. The specific activist groups fea-tured in this thesis were selected for being those that, during my fieldwork, affected the most people through their large mobilisa-tions involving citizens from the general public and

solidarity-based work involving people in precarious legal conditions. How-ever, as contradictory as it may seem, this kind of activism is in-creasingly becoming incorporated into the cultural diversity that constitutes the attractiveness of the city in the context of neoliberal economic changes.

The activist scene in and around Möllevången is diverse in terms of lifestyles, age, and backgrounds even within one and the same activist group. Although all my research participants would regard themselves as left-wing in the broadest sense, their political view-points, concepts, theories, and practices differ widely. There are students, the unemployed, the self-employed, white- and blue-collar workers, PhD students, and academics, who live in flat-shares, rented single flats, and tenant-owned flats. Their financial situations vary, ranging from some who rely on benefits to oth-ers—the majority of the activists I met during my fieldwork—who are clearly located in the middle class.6 There are vegans,

vegetari-ans, and meat-eaters and, as far as subcultural fashion is con-cerned, there are hipsters, punks, anti-brand hippies, but also the anti-hippie subgroup that wears mainstream clothing such as Adidas as well as those who don’t care what they wear. Amidst this variation, one important link between them all is Möllevången, which, as a place, enables productive relationships and alliances.

These activists are utterly frustrated by the vast and growing disparities in the world—as of 2017, eight people (all men) own the same amount of wealth as the poorest half of the world’s in-habitants (Oxfam 2017)—and therefore desire a socially just and radically democratic society. Activists in Malmö attempt to find ways to build concrete, practical links between disparate struggles, and to engage in the extremely difficult task of dealing directly with the divisions and inequalities that exist among social groups, such as between white Swedish citizens and racialised Swedish citi-zens, or between Swedish citizens on the one hand, and asylum

6 ‘Middle class’ is a vague term and commonly used to refer to the broad group of people who are

socio-economically located between the working class and the upper class. The definition of the term is highly contested and it is defined differently depending on the political interests of those (e.g., economists) who define it. Some narrower definitions focus on income, profession, or lifestyle. What is termed middle class in common usage is what many leftist oriented activists would identify as the working class.

seekers, undocumented migrants, and Roma migrants on the other. Issues such as economic injustice, racism, and sexism are funda-mental concerns for the activists featured in this thesis. They ques-tion the neoliberal ethics of individualism and personal responsibil-ity for one’s own dispossessions, and instead point at how politi-cal-economic structures constrain the lives of individuals.

The political space of Möllevången has supported emergent ac-tivists. Rather than hiding, some migrants under threat of deporta-tion or evicdeporta-tion have publicly claimed their rights to inhabit the city too, through assertive and sometimes disruptive collective ac-tions in Malmö, such as occupaac-tions, sit-ins, and blockades. How-ever, these actions would not have been possible without the al-ready established network of local activists who support and ena-ble the resource-poor people to concert their oppression into col-lective political actions. Formerly undocumented migrants have be-come prominent activists in Malmö and have formed their own or-ganisations, which adds a new dimension to the activist scene.

Explaining how activism in Malmö contributes to the social and spatial emplacement of people with different social, economic, ed-ucational and migrant backgrounds, and how it creates space for shared experiences and solidarities, is one of the main theoretical points of this thesis. Additionally, I wish to offer an understanding of the particularities of the city while also illuminating the links to other cities. In other words, I wish to contribute to new ways of theorising solidarities born on the ground in an urban context marked by immigration and economic restructuring.

No study in a single place or city can ever prove a point but can offer suggestions for new ways of conceptualising, theorising, and categorising. Things keep changing: Swedish migration policies may have changed by the time this thesis is published, some of the activists might exit the activist scene, new ones might enter, differ-ent conflicts and alliances might emerge, and Möllevången might become a much more gentrified urban place under more surveil-lance than it was at the time of my fieldwork. However, ethnogra-phy allows for showing, in detail, the multiple interconnections be-tween migration, dispossession, and urban restructuring as they emerged at a particular time and in a particular, historically

shaped, local setting. Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork and con-versations with a number of activists, this thesis provides sound empirical groundwork for exemplifying and explaining those inter-connections. It thereby contributes to scholarship pertaining to mi-gration, urban studies, and social movements occurring in times of global economic restructuring.

The activists pose provoking questions: how did we end up here—to the state in which people who have fled from war and are in need of help are being sent back to their war-torn homelands? Why are there such high rents in certain urban areas of Swe-den/Malmö/Möllevången that only relatively wealthy people can afford? Why does the city build tenant-owned flats that only a few people can afford to buy? Why are neo-nazis,7 who wish to abolish

democracy and create a nation based on ethnicity and culture, al-lowed to march in the streets? Scholars, journalists, intellectuals, politicians, and others ask these questions too, but the activists act upon them, and they do so collectively and bodily in the streets and in direct contact with people living in precarious conditions. This thesis is about those actions, about bodily strategies, solidarity, po-litical socialisation, and the friendships that are built and enabled, in large part, through storytelling about a place—the Möllevången neighbourhood in Malmö as an ‘anti-racist zone’—shared by peo-ple who come from near and far and are in different situations and have different needs.

7 In this thesis I do not capitalise neo-nazis, nazis, or nazism unless the words refer to the historical

INTRODUCTION

This thesis concerns the interaction between place, power, and re-sistance by addressing two major interrelated issues: how collective actions and spaces of solidarity are created and enacted in Malmö and how they impact the place (Malmö/Möllevången) and social relations (between activists as well as between activists and non-activists). I explore these issues by analysing a particular political practice—activism as carried out by the extra-parliamentarian left—based on ethnographic material collected 2013–2016 in Malmö, Sweden. A decisive aspect of the context of the collective actions—people joining together for a common cause—that is be-ing studied is the particularity of the city of Malmö, a city with a high density and diversity of activist groups. Their actions are con-centrated mainly within the Möllevången neighbourhood, which, in the period of its transition from industrial to financial capitalism (neoliberalism) and due to its central location and affordable hous-ing, has attracted politically engaged people to live there.

Two important sources of urban social change are of particular interest when studying political activism in Malmö: migration (both internal and international) and neoliberal restructuring. The changing patterns of urban restructuring (gentrification and segre-gation), migration (labour-related and refugees), and the privatisa-tion of the commons have resulted in new forms of activism born on the ground. With the understanding that neoliberalism produces “new battle zones around privatisation, retrenchment and social polarisation” (Mayer 2006, 204), I analyse the trajectories of pow-er as they empow-erge at a particular time in the form of activists’ col-lective actions of resistance and solidarity, many of them (but not

all) in the particular urban location of Möllevången. The term ‘ac-tion’, short for ‘direct action’ or ‘collective ac‘ac-tion’, which is the term I mainly use in this thesis, is used by activists for undertakings varying widely in scale and means as well as in principles, purpos-es, and implications. It can be used “for anything from leafleting in front of a supermarket to shutting down a global summit” (Grae-ber 2009, 359).8 These actions are not isolated instances of

disobe-dience, but rather “clues to underlying structures and relationships which are not observable other than through the particular phe-nomena or events that they produce” (Wainwright 1994, 7).

The activist groups presented in this thesis (see also Chapter 1), I claim, open up spaces for counter-hegemonic politics and ‘em-placement’, which is the social process through which an individual builds or rebuilds networks of connection within the constraints and opportunities of a specific city (Glick Schiller and Çağlar 2015). They are: Aktion mot deportation(Action Against Deporta-tion); Förbundet Allt åt alla (The confederation Everything for Everyone, hereafter called Allt åt alla); Asylgruppen (The Asylum Group); Kontrapunkt (Counterpoint, a social centre); and Skåne mot rasism (Scania9 Against Racism). Their activism concerns

mi-grants’ and asylum seekers’ rights, anti-deportation, anti-racism, anti-fascism, and ‘right-to-the-city’ struggles (e.g., against gentrifi-cation and welfare retrenchment), which they address with strate-gies ranging from solidarity-based work and advocacy to more rad-ical forms of direct action like blockades and sit-ins. These differ-ent strands of struggle are interrelated not only through the indi-viduals and groups of activists who participate and build alliances across these struggles, but structurally: the different struggles emerge as reactions to, and at the intersections of, racism, com-mercialisation, and restrictive migration policies. They form part of a larger network of leftist, extra-parliamentarian activists that strives towards urban and social equality in Malmö, other cities in Sweden, as well as abroad. Even though the activist groups listed

8 In daily usage, it refers to any collective undertaking that has political aims and is carried out with

the awareness that it might be met with hostile intervention on the part of the police or other antag-onists (Graeber 2009, 359).

above differ in many ways, they are analysed as part of the same vivid activist scene in the city—as part of the same ‘alternative mi-lieu’ (for a review of the term see Longhurst 2013)—associated with Möllevången.10 My inclusion of different groups is, however,

not intended to cover up the dividing lines that also exist. In the empirical chapters, I examine the challenges, ambivalences, and conflicts that emerge in their processes of ‘commoning’, which are based on practices of building common spaces, interests, and expe-riences (Dawney 2013).

All activists in this thesis have a connection to Möllevången (popularly called Möllan): an inner-city, socially mixed, gentrifying neighbourhood in Malmö (see Figure 1). They either live or have lived there, or it is the place where they spend much of their daily and activist lives. The neighbourhood is known for its high pres-ence of activists but also of migrants of different origins and with different migration trajectories and times of arrival in Malmö or to Sweden. These characteristics are used in the city’s narrative to at-tract residents, tourists, and investments.

An important understanding of place in this thesis, beyond its actual physical dimensions, is that places are social constructs; they are interpreted, narrated, perceived, felt, understood, and imagined (Soja 1996). Places are imbued with meaning as well as power, which is important in activism. Activists often seek to strategically manipulate, subvert, and signify the places, practices, and narra-tives they are contesting, to defend places that stand for their prac-tices and narratives, and to produce new spaces where such visions can be practiced, both within that place and beyond (Leitner,

10 While my focus is on activities carried out by the above-mentioned groups, it is important to

acknowledge that there are many other initiatives that in a variety of ways resist and contest the ef-fects of neoliberalism, racism, and the enforcement of national borders, including detained migrants in detention centres on hunger strikes; doctors who treat patients in hospitals irrespective of their legal status; children in schools who, together with their parents and teachers, protest the deporta-tion of classmates; alternative media that engage in promoting non-neoliberal forms of knowledge; worker cooperatives; artists; and university-civil society partnerships. There is also NGO-based activ-ism. However, these fall outside the scope of this study. This thesis engages with resistances made by members of, or in the name of, political groups within the extra-parliamentarian left whose principal aims are precisely to enact resistance outside of formal institutions and state structures by using methods of direct action and civil disobedience. I see an important distinction between formal organ-isations and non-institutional, grassroots, and confrontational forms of mobilisation (Juris and Khasnabish 2013, 16).

Sheppard, and Sziarto 2008). Möllevången is a product of various and sometimes conflicting narratives. The concept of narrative, or story, allows one to explain how different people can give the same object different meanings.

This thesis is informed by Doreen Massey’s (1995; 2005) under-standing of place. She argues for thinking of geographical places as temporal and not just spatial, or as set in time as well as in space. History is thus important for a better understanding of an urban place. Stories that are being told and retold about Möllevången in the past and present have influenced the construction of that place. Two historical interpretations are competing: one understands Möllevången to be a slum, as dangerous and thus horrible, and an-other perceives Möllevången as wonderful and fantastic, always inclusive. The claims on its present character depend on “particu-lar, rival, interpretations of its past” (Massey 1995, 185). A narra-tive of Möllevången that is gaining ground today is as an ‘anti-racist’ place or as representing the politically left ‘red zone’ of the city. The stories people tell of Möllevången as ‘red’ (the colour tra-ditionally associated with socialism) help generate strong relations among activists, which are needed in order to facilitate mobilisa-tion, which is the process by which people assemble and prepare for a joint political action. These articulations further attract not only activists and leftist-oriented people in general to the neigh-bourhood but also asylum seekers, especially if their application has been rejected and they travel to Möllevången to seek support from pro-asylum activists. Also, Roma migrants who hold citizen-ship in another EU (predominantly Eastern European) country are attracted to beg here for a living due to its favourable conditions, including the presence of amiable people who defend them if at-tacked by passers-by.

Massey (2005) further sees place as a clash of trajectories: a ‘throwntogetherness’. Möllevången is constructed out of multiple social relations and trajectories—the baker, the shopkeeper, the resident, the activist, the landlord, the undocumented migrant, the tourist, the fieldworker, and the underpaid labour migrant—a mul-tiplicity of relations that is constitutive of its space. If time is the dimension in which things happen one after another and hence

change, space is the (social) dimension of multiplicity and simulta-neity. All these relations are marked by power and thus Möl-levången is also a geography of power, and the distribution of those relations mirrors the power relations we have within society. Space is indeed political because power is distributed unequally (Massey 2013). Some places have power over others (such as Lon-don over Malmö) and some groups over others (citizens over non-citizens, rich over poor).

‘Space’, as used here, does not refer to physical space, although there may be physical manifestations of it. Rather, space is an ab-stract place that is socially and structurally produced (Lefebvre 1991). Beyond being a geographical place and a product of story-telling, Möllevången is a space that has a meaning that is not lim-ited to the actual boundaries of the neighbourhood. In this thesis, I will show how Möllevången emerges as an idea of a better place.

The city of Malmö is the entry point for studying how place and space are created though activism that challenges and reconstitutes particular power relations. Drawing on Massey’s (1994) relational and global view of place, I further understand Möllevången, just as any other place, as a product of social relations that stretches far beyond its geographical borders. I will show how Möllevången is not only a ‘neighbourhood’ in the sense of a delineated place on a map, but also a network of social relations and friends in the city who identify with the idea and the place of Möllevången. Howev-er, Möllevången is not just ‘any place’ but an important one in Sweden today due to its rich and supportive activist environment. It is the unique constellation of trajectories that produces particular places and spaces, and, as I have suggested, the activists’ presence in Möllevången plays a central role in this neighbourhood’s partic-ularity. Many activists moved to Malmö because, as many have said, “no other city has a Möllan”. It is a city in which they can be politically active within a supportive milieu in the way they desire. Taking the definition of the political space of Möllevången as a product of interrelations, it becomes clear that “space matters” (Massey 2005). This particular space is not to be seen as a ‘con-tainer’ of activism but as a process that produces relationships and networks (including the processes that produce gender, ‘race’, and

class identities). While places may be designated as private or pub-lic and have different symbopub-lic values expressed in terms of dan-gerous, festive, trendy, politically charged, etc., spaces are gen-dered, raced, and classed (Sewell 2001, 64). In line with Anthony Giddens’s (1984) understanding of social structures as ‘dual’, space shapes people’s actions, but it is also people’s actions that consti-tute and reproduce space. Certain spaces can put constraints on people’s actions, but spaces may also enable actions.

If Malmö and Möllevången, then, are understood as ever-shifting constellations of trajectories, it is in this disorder of ‘throwntogetherness’ that the possibility of political action opens. Since place is open, relational, unfinished, and always under con-struction, it is possible to create alternative imaginaries of the place, to create new spaces, and to challenge the accepted givens of, for example, free market- and state-oriented social relations and formulate disruptive political questions. “It is a world being made, through relations, and there lies the politics” (Massey 2005, 15). The organisation and production of space—for example, who is allowed access to the place and who has power over it (Valentine 2017), who is meant to feel at home there (Ahmed 2007), how long one must be there to become a local—can be challenged and changed.

In the theoretical chapter (Chapter 1), I provide a discussion in which the spatial perspectives of activism and politics are clarified. My take on both space and place in this thesis, in simple terms, is that they are not about physical locality as much as about relations between people, which makes them political. As will become clear in the empirical chapters, Möllevången takes the form of a social network stretched out across the whole city and beyond rather than of a ‘neighbourhood’ in the geographically material and bounded sense. This network of social relation was discerned by using ethnographic methods, which are described in Chapter 2.

The political space of Möllevången, explored in Chapter 3, is de-fined by the density of activists, activist spaces (cafés, social cen-tres, bookshops, etc.), and frequent mobilisations in public spaces, which, together with the stories told about the place, enable and facilitate the transformation of people’s displacement and

dispos-session into collective actions. Möllevången further constitutes an efficient platform for forging ‘politicised collective identities’ (Si-mon and Klandermans 2001): ‘us’ (the dispossessed) against ‘them’ (representatives of dispossessive forces, such as politicians, corpo-rations, institutions, and the state). This ‘us’ created by activists depends on each particular struggle, i.e. the collective effort to ad-dress a political issue. It can be ‘us’ as referring to everyone who makes up the social fabric of the place: residents, workers, as well as Roma migrants, asylum seekers, and undocumented migrants who, with different needs, all claim access to Malmö. However, a more totalising and homogenising ‘us’ is created when referring to the ‘agents of change’ in Möllevången, who are ‘the activists’ and are examined in Chapter 4.

Two central claims are made in this thesis: that (1) activism in Malmö has generated alliances and friendships that cross social, cultural, and ethnic divides; and (2) these relationships constitute an important resource for not only resisting material, emotional, and aspirational dispossessions, but also for enabling resource-poor people to transform their dispossession into large-scale mobi-lisations. The relational opportunities of Möllevången have even enabled the formation of a new generation of formerly undocu-mented migrants to become activists and form their own organisa-tions. In other words, the political space of Möllevången provides the resources and relational opportunities that can support emer-gent activists (Nicholls and Uitermark 2017, 8). Established activist groups have supported the creation of new activist groups: mi-grants with precarious legal status have formed their own organisa-tions (e.g. Ensamkommandes Förbund and Nyanländas Röster, see Glossary) and taken action to assert their rights to be in the city (e.g. Tältaktionen, Asylstafetten, and a 24-hour sit-in outside the Swedish Migration Agency in Malmö). Some of these struggles un-fold at the regional and national scale: for example, the recurrent pro-asylum march Asylstafetten, which took place every summer 2013–2018. The first march, in 2013, lasted for 34 days. The par-ticipants marched 750 kilometres from Malmö to Stockholm call-ing for asylum seekers’ rights (Joorman 2018). However, this thesis does not focus on these new groups and the direct action they take,

but on the established groups that I claim have enabled the for-mation of the new ones.

I am not studying a neighbourhood or city as such but rather us-ing them as points of entry for better understandus-ing how activists create a place through their activities and how the place generates activism. The activists’ political practices play an important role in the making and remaking of Möllevången, which is a place that has been made and remade through historical forms of activism, class struggle, and working-class identity. I therefore approach ac-tivism in this thesis as a ‘city-making practice’ (Çağlar and Glick Schiller 2018). Despite the fundamentally different conditions met by a refugee or a Roma migrant in contrast to a Swedish citizen, they are all nevertheless co-creating the city through the building of social relationships by engaging in solidarity and by protesting against their own and others’ dispossession. Solidarity here means a relationship forged between actors in unequal power relations that aims towards a more equal order.

My research shows that activist sociabilities in Malmö, estab-lished by people who, despite their differences, construct locally embedded solidarities and shared experiences and narratives, ena-ble the transformation of dispossession into political struggle against the growing disparities and displacements of global capital-ism. My research includes the experiences and views of people in relative positions of power (economic, cultural, legal, and social) who inhabit the same city that was founded on the exploitation of the many by the few (Harvey 1976). Hence, activists and residents in more privileged positions (middle-class, citizenship) also experi-ence dispossession. Activists experiexperi-ence dispossessive processes within a concrete setting, “not as the end result of large and ab-stract processes”, but rather “it is the daily experience of people that shapes their grievances, establishes the measure of their de-mands, and points out the targets of their anger” (Piven and Cloward 1977, 20–21). The precarity effected by neoliberalism is not confined to those at the bottom of the class structure, since the antagonism between capital and labour is no longer concentrated in specific places of work, but traverses the whole of society (Tyler 2015). This thesis thus reveals how people of different

back-grounds and positions are affected, albeit in different ways and to different extents, by ‘accumulation by dispossession’ (Harvey 2004) and how they come together and take action against their own and others’ dispossession.

The processes of dispossession produce various forms of physical and social displacement, including border-crossing migration (pre-cipitated by war, so-called development, structural adjustment, im-poverishment, and environmental degradation) as well as unployment, part-time emunployment, lower wage rates, loss of em-ployment security, forced relocation, and downward social mobili-ty (Glick Schiller and Çağlar 2015). Many of the activists I talked to are middle class and thus economically privileged in relation to working-class activists and residents. Furthermore, most activists are Swedish citizens, thus clearly privileged in comparison to resi-dents and activists in precarious legal conditions. However, even Swedish activists (with citizenship) experience and are affected by the changes in Möllevången as well as by the marketisation of housing, labour, and healthcare, although they are usually even more concerned with and affected by the dispossession of people more vulnerable than themselves. I use displacement and disposses-sion (terms further discussed in Chapter 1) to refer to the unpre-dictability and precarity brought about by neoliberal restructuring and migration policies. I also use dispossession to refer to the emo-tional and aspiraemo-tional yearning to foster collective interests and collective ways of being in the ‘post-political condition’, meaning here a condition in which individualism, self-interest, and competi-tion are assumed to be the guiding principles in people’s lives.

While the city is the entry point for studying how place and space are created though activism, activism is my entry point for studying social relations. As a social phenomenon and a process that changes social relations, activism can reveal how various iden-tity markers (such as class, gender, sexuality, ideology, generation, ethnicity, and disabilities) interplay in the creation of ‘us’. The col-lectivities based on such markers are of different scales and con-stantly in flux, meaning that these collectivities encompass all kinds of empirical phenomena: from formal belonging and identification with a particular local activist group to the perceived collectivities

that my interviewees see themselves as being affiliated with, such as ‘no border global citizen’, ‘the working-class’, ‘precariat’, ‘anti-fascists’, or ‘feminists’. This thesis is an exploration of the relation-al impacts of this kind of activism in Mrelation-almö, and how space is cre-ated through concerted action. ‘Space’ enables me to better under-stand social relations and the people who access and appropriate place. Particular attention is paid to how activism enablessocial relationships and even close friendships across the divides of class, ethnicity, legal status, and gender and between Swedish citizens and people with a precarious legal status, such as undocumented migrants or Roma migrants who hold citizenship in another Euro-pean country. Even though a lot of activism takes place online, ur-ban space is nevertheless crucial for the forging of these relations.

Before elaborating on the aim and research questions of this the-sis, I want to make a few remarks on the networks of power within which the activist groups operate. As noted above, all relationships are fundamentally spatial. No space is without power and hence no relationship is either. Space matters precisely because it is relational (Miller 2013). To adopt a multiscalar analysis, which is my inten-tion in this thesis, means to situate activists within various net-works of power. I cannot study activism as a bounded phenome-non but must trace the network of relations that the political groups and activists have with other activist groups, institutions, discourses, media, state institutions, etc. The surrounding condi-tions of a protest event or activist group are crucial for its occur-rence or existence in the form it eventually takes. I intend to make those interdependencies explicit in my explanations, and they are mainly illustrated in the form of challenges, ambivalences, and con-flicts.

As elaborated in the empirical chapters, the activist groups are located in power hierarchies with one another. Each group’s posi-tion of power and influence varies depending on the issue, place, and time of struggle. All collective actions involve “ongoing ten-sions between building and breaking relationships” (Miller 2013, 293). What I want to underline here is each group’s dialectical rela-tionship to the others, as well as to other groups and institutions in society (anti-immigrant groups, the media, the general public,

po-litical parties, NGOs, state institutions, corporations, local gov-ernments, etc). Hence, there are different ‘scales’, or ‘spatialities’, of power in which activist groups act. And these relations are de-pendent on time and place and reshaped through struggle. There-fore, activist groups continuously reshape scalar relations.

Aim and research questions

The overarching aim of this thesis is to explore how activists’ aspi-rations for a more equal society were practiced in Malmö, particu-larly in the neighbourhood of Möllevången, during 2013 to 2016. I analyse activism as a place-making practice that opens new spaces of politics and pathways of emplacement. As an ethnographer studying activism, I aim to analyse the locally embedded emergence of social relations, values, and categories while teasing out the ac-tivists’ tacit, underlying assumptions concerning their activities and subject positions as well as the challenges, ambivalences, and con-flicts found within this specific socio-political practice. As a migra-tion scholar, I aim to identify how activism impacts social relamigra-tions between different people in hierarchies of power in an urban con-text that is affected by global patterns of (labour and refugee) mi-gration and neoliberal restructuring. This thesis is an exploration of activists’ doing in both a discursive and a bodily sense. ‘Bodily’ indicates what is revealed in a place in the form of collective tions or solidarity, and ‘discursive’ indicates the ways in which ac-tivists talk about the issues and people they address.

My approach to Möllevången is based on the understanding that no place is bounded since every place is connected to multiple plac-es (Massey 1995). The local is multiscalar; the global is always ‘here’. Understanding place as multiscalar means defining locality as processes of the mutual constitution of the local, regional, na-tional, and global through time (Çağlar and Glick Schiller 2015). Places have some type of territorially based system of governmental authority, yet are relationally constituted within multiple, intersect-ing trajectories of power (ibid.). To focus on a socio-political prac-tice (activism) in a certain neighbourhood thus requires the consid-eration of regional development, capitalist processes of accumula-tion on a global scale, migraaccumula-tion patterns, and urban restructuring

at the same time. I therefore understand the city, Malmö, as an en-try-point and not as a bounded unit (Glick Schiller and Çağlar 2011) in order to trace and document processes of restructuring, dispossession, migration, and emplacement by looking at activism. Hence, my entry point for studying inequalities and their contesta-tions through activism is twofold: (a) the place, Malmö/Möllevången; and (b) the processes of activism, which are local struggles that travel beyond the borders of Malmö. This the-sis therefore poses questions that address the interconnected fields of urban restructuring, dispossession, and activism.

The overarching question guiding this thesis is: How is solidarity created and enacted in Malmö by left-wing, extra-parliamentarian activists and with what impacts? The more detailed questions asked are:

1. How is activism in Malmö linked to economic and urban re-structuring, migration, and inequality?

2. How is activism facilitated by, and how does it affect, the place in which it occurs?

3. What challenges do the activists face in their attempts of for-mulating common interests and creating common spaces? 4. What are the effects of left-wing, extra-parliamentarian

activ-ism in Malmö on a larger societal scale?

An ethnography of activism is a powerful resource for exploring activism in a particular place and its connection to larger structures of economy and migrations. I make use of theories on how struc-tures impact and engender activism while also recognising the ac-tivists’ agency and their capacity to create and recreate space. This study provides interpretations of social settings, events, and pro-cesses by considering the meanings that the activists involved have given to them (Vidali 2014).

As this thesis explores the locally embedded emergence of social relations and the processes that enabled them, ethnographic