Communication for Development One-year master

15 Credits 2021

Supervisor: Vittorio Felci

Visibility, conviviality and active listening

A case study of an exogenous project in Africa´s last colony

Celia Sánchez-Valladares Barahona

(Word count: 13642)

2

This research project is dedicated to all the people from Western Sahara who constantly fight for their freedom, being an inspiration of hope and resilience, worldwide.

I would like to acknowledge the twenty-three participants of this study, for their openness and willingness to share their knowledge and experiences. In special, I want to thank the ten Saharawi

activists to whom I had the pleasure to listen. Thank you for inspiring me to write this thesis. Thank you to my supervisor Vittorio Felci, for making of this challenging task a fun experience,

supporting me along the way and keeping me on the right track.

To my mother and my sisters, for believing in me, always and with no doubts. To you Ahmad, for your unmeasurable patience and love. To my father, for giving me the energy to never give up. Finally,

3

Abstract

The occupation of Western Sahara is a question of a forgotten colonization with a very limited framework of international recognition, media acknowledgment and talks. To break the remaining silence and invisibility, human rights activists have developed different initiatives, shedding light on the current situation of Western Sahara. This study investigates the Sahara Marathon campaign, an international sport event that has been developed in the Western Sahara refugee camps of Smara, El Aaiún and Auserd for twenty consecutive years.

Framing the Sahara Marathon as a case study, this degree project aims at inquiring into the potential impact and long-term implications of the international sport campaign, seeking “if” and “how” it contributes towards a social change and an end to the enforced invisibility of “Africa's last colony”, (Güell, 2015). In particular, this qualitative study examines the participatory approach and community engagement promoted through the campaign as well as the awareness-raising and dialogical processes triggered as a result of the Sahara Marathon sport event. The study is grounded on 23 in-depth interviews that have contributed to the external reliability of the research, underlining the reflections shared by organizers of the Sahara Marathon, drivers, freelancers, runners and most importantly human rights activists from Western Sahara. Findings reveal that the Sahara Marathon campaign raises awareness about the current situation in Western Sahara, contributing to a transnational acknowledgment of the conflict. The study also shows that active listening and convivial experiences are promoted throughout the campaign, dismantling stereotypes among communities coming from abroad and Saharawi people living in the refugee camps. In terms of participation, it has been concluded that the campaign uses a participation by consultation approach, needing a new model to showcase the utility and effectiveness of the event as well as to ensure its sustainability in the future.

Keywords: human rights, Western Sahara, social change, Sahara Marathon, visibility, awareness,

participation, conviviality, active listening, stereotyping, colonization, agency, Communication for Development

4

Contents

Abstract ... 3

Introduction ... 5

Historical background on Western Sahara ... 6

Case presentation: The Sahara Marathon... 9

Literature review ... 12

Sport-for-development programs ... 12

Volunteering while doing tourism ... 15

Theoretical framework ... 18

Participatory communication approach ... 19

Dialogical processes and collective action ... 19

Community participation in a development intervention ... 20

Sustainable partnership approach & conviviality ... 21

When Looking good overpasses Doing good - current trends and the White Gaze of development ... 22

Subverting the colonial gaze, shifting towards Indigenous Knowledge ... 23

Research design framework ... 23

Methodological approach ... 24

Selection of participants and research conduct ... 24

Ethics, reflexivity and limitations ... 25

Analysis and research findings ... 26

Visibility as a weapon against silence ... 27

Messengers for freedom ... 28

Conviviality as a hub for new gazes and networks ... 30

Being present but not as hosts ... 33

Looking good while doing solidarity work ... 36

Conclusion ... 38

References ... 41

Appendices ... 47

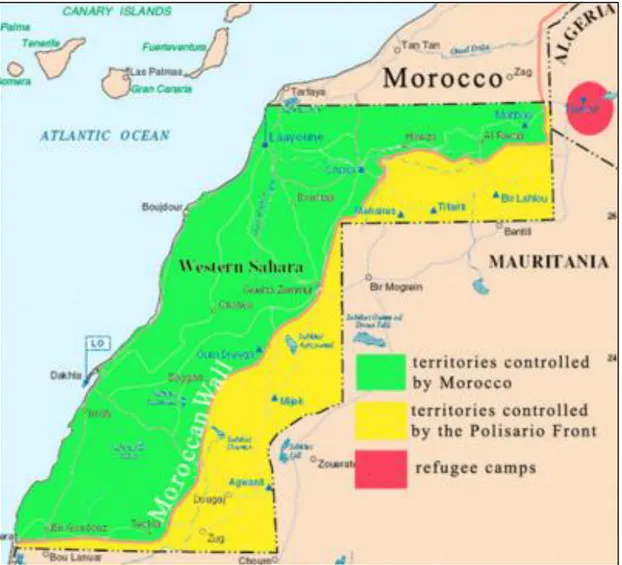

Appendix 1. Map of Western Sahara ... 47

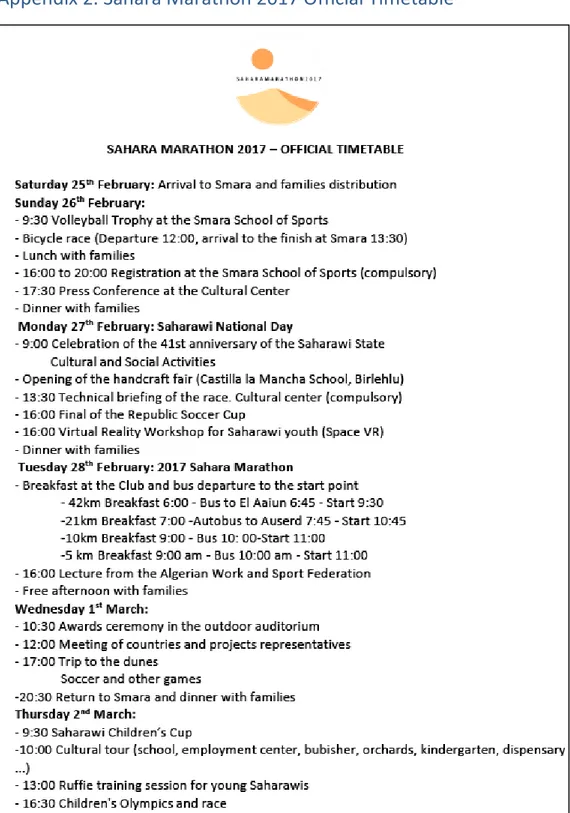

Appendix 2. Sahara Marathon 2017 Official Timetable ... 48

Appendix 3. Interview Guide to Saharawi activists ... 49

Appendix 4. Four samples of Interview Transcripts ... 51

Said ... 51

Nour ... 55

Omar ... 60

5

Introduction

Western Sahara, also known as “Africa's last colony” (Güell, 2015), has been on the list of Non-Self-Governing Territories since 1963. Even though Morocco’s claim to sovereignty over Western Sahara is not recognised by any state, nor by the United Nations (WSRW, 2019, p.4), the conflict of Western Sahara is a question of decolonization (Ruiz Miguel et al., 2018, p.69).

Morocco´s occupation over Western Sahara entails continuous human rights violations against people of Western Sahara, such as enforced disappearances, torture, killing and the plunder of natural resources over the territory (Human Rights Watch, 2019, p.403). Still, albeit the extreme character of the situation, the case of Western Sahara has been referred on many occasions as a “forgotten conflict” (FCA, 2019), scaled by a 10out of 11 within the forgotten crisis assessment index of 2019, with some of the lowest grades in relation to media coverage and public aid per capita. In order to raise awareness of the current situation in Western Sahara, a variety of international development campaigns take place in the Saharawi refugee camps every year. This is the case of International Encounters of Arts and Human “ARTifariti”, the international cinema festival “Fisahara”, and the international sport event “Sahara Marathon”. Celebrated throughout twenty consecutive years, the Sahara Marathon defines itself as a solidarity campaign, which main goals are to fight against the hindering and lack of acknowledgement of the conflict, preventing the Saharawi cause from being forgotten and addressing informational gaps as well as to raise funds for developing humanitarian aid projects in the refugee camps while encouraging the international community to translate awareness into action after they come back to their home countries (Muñoz, 2018, p.23). This research will analyse the Sahara Marathon sport event, to investigate the campaign approaches to Social Change, aiming to contribute to the field of Communication for Development and Sport-for-Development research. Through a case study of the campaign, this degree project uses the lens of community participation, inclusion, engagement and visibility, as a qualitative and exploratory research conducted through twenty-three in-depth interviews. Finally, this case study aims at providing a glimpse into processes of development, behavioural and social change, exploring the potential impact, implications and contributions of the campaign towards a social change and a status-quo shift in the question of Western Sahara.

The main research questions that guide this degree project are the following:

• What are the potential effects and implications of the Sahara Marathon campaign for a social change in the situation of Western Sahara?

6

• How do people of Western Sahara perceive this campaign and how do they participate in the Sahara Marathon international sport event?

To answer these research questions, I start with historical background information on Western Sahara, continuing with the case study presentation of the Sahara Marathon campaign. This is followed by a literature review about sport-for-development research and volunteer tourism as well as the existing gaps and challenges within these fields of study. I then provide a theoretical framework and methodology section that include concepts such as the community participatory approach, active listening and manufactured consent as well as the research conduct, ethics, reflexivity and limitations within the study. The main findings of the Sahara Marathon case study are then analysed and presented in relation to the theoretical framework. Finally, the concluding section provides an answer to the research questions as well as some suggestions for future research.

Historical background on Western Sahara

Western Sahara is located on the West coast of Northern Africa, bordering Mauritania in the South, Morocco in the North, Algeria in the East and the Atlantic Ocean in the West. The territory has an extension of 266 000 km1 (Codina et al., 2018, 13), although 80% of its territory remains under

Moroccan control and occupation2 (Human Rights Report, 2018, p.1). Most of the people of Western

Sahara belong to the nomad’s indigenous population known as the bidan society and the primary language in Western Sahara is Hassaniya3.

Chronologically, moving back to the sequence of events that occurred over the territory, on November 28th of 1884, Spain4 signed a treaty of protectorate with some independent Saharawi

tribes and founded the city of Villa Cisneros5 (Ruiz Miguel et al., 2018, p.17), colonizing the territory6

and instilling a continuous plunder of natural resources7 over the Saharawi territory and its people.

Despite the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols on 1949, as well as the first attempts

1 A map of Western Sahara can be found in the Appendix 1.

2 Within the 20-remaining percentage of the liberated territories, there are included the refugee camps of

Tindouf, in Southern Algeria, in which 173.600 Saharawi refugees live for the past 46 years under extremely difficult circumstances and almost entirely dependent on humanitarian aid (UNHCR, 2018, p.4).

3 a dialect that comes from the Arabic language.

4 formal colonial and administering power of the territory. 5 the city of Dakhla.

6 Spain communicates the treaty of protectorate to the foreign powers that met in the Berlin Conference on

December 28th, 1884.

7 The phosphate reserves discovered in Bou Craa in 1947 are an example of this plunder of natural resources.

The Bou Craa phosphate reserves became the first source of mineral revenues for the Spanish colonial power. By then, Western Sahara was also known as Spanish Sahara.

7

toward the decolonization of Western Sahara during the 60s with the UN Special Committee on Decolonization in 19638, the requests to Spain both in 1965 and 1966 to decolonize the territory9

and to hold a referendum for Western Sahara’s self-determination under the United Nation supervision10, resulted into failed attempts. A few years after, in 1973, the legitimate representative

of the people of Western Sahara “El Frente Popular para la Liberación de Saguia el-Hamra y Río de Oro”11 is founded and recognized by the United Nations as the legitimate representative of the

Saharawi people (UNOCHA, 2019). The same year, a first military operation occurred in Western Sahara between Polisario and Spain to achieve the independence from the Spanish colonial rule. Two years after, in 1975, the International Court of Justice urged the need for the right to self-determination to apply, stating that: prior to Spanish colonization, the territory belonged to neither Morocco nor Mauritania, not having legal ties with any of both12. Despite of the advisory opinion

from the International Court of Justice, on 6th of November 1975, the then King of Morocco Hassan II initiated “the Green March” to claim sovereignty over the territory. This apparently peaceful demonstration entailed the invasion of Western Sahara’s territory, which forced over half of the Saharawi people to flee from their home country.

Even though the invasion of Western Sahara was condemned by the UN Security Council, less than two weeks after and six days before the death of the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, Spain signed the Madrid Accords13 together with Mauritania and Morocco, in an attempt to cede the

administering power of the territory to both Mauritania and Morocco, and to get exempt from the unfulfillment of its International Law obligations. Afterwards, Morocco signed the Rabat Accords together with Mauritania, dividing Western Sahara´s territory. Then, the war begins and lasts until the cease-fire in 1991. Within this period of time, on 26 February 1976, Spain formally withdraws de facto as a colonial power and, one day after, on February 27, the Polisario Front declares the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), and the refugee camps of Western Sahara are established in the middle of the desert, in Tindouf, South-west Algeria.

8 The General Assembly resolution 1514 (XV) declared Western Sahara a “non-self-governing territory to be

decolonized”, in accordance with the 14 Dec 1960 Declaration on the Granting of Independence of Colonial Countries and People.

9 In 1965, The UN General Assembly adopted its first resolution on Western Sahara, the General Assembly

resolution 2072 (XX) of 17 December 1965

10 General Assembly resolution 2229 (XXI) of 20 December 1966 on the “Question of Ifni and Spanish Sahara”.

In this resolution, it is noted that the Spanish government, as administering power over the territory, had not yet applied the provisions of the 14 Dec 1960 Declaration. More information can be found here:

http://www.worldlii.org/int/other/UNGA/1966/101.pdf

11 herein referred to as Frente Polisario or Polisario Front.

12 Western Sahara, Advisory Opinion of 16th January 1975, I.C.J. Reports 12, 162

13 Also known as the Tripartite Agreement, the Madrid Accords were signed without the prior consultation of

8

Figure 1. Western Sahara refugee camps, Smara 2020. Credit: Celia Sánchez-Valladares/2020

After four years of continuous fighting, the Polisario Front and Mauritania signed peace in 1979, a peace that triggered the annexation by Morocco of two-thirds of Western Sahara´s territory (Hagen & Pfeifer, 2018, p.19), invading the area previously controlled by Mauritania14. One year after, in

1980, a 2720 kilometre-long15 sand-berm surrounded by mines is built by Hassan II16, cutting

diagonally through Western Sahara from its northeast-corner down to the southwest near the Mauritanian border (Beristain, et al., 2017, p.31). The wall exists up until today and is commonly known as The Wall of Shame (Bachir, 2017, p.79).

Around that time, by the end of the 1980s, the United Nations designed a peace plan which set out a voting from Western Sahara to decide whether being an independent country or being integrated

14 and despite the United Nations condemnation of Morocco´s occupation. More information can be found in

the General Assembly Resolution 34/37 of 21 November 1979 on “the continued occupation of Western Sahara by Morocco”: https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/un-documents/document/ares3437.php

15 Recognized as the second-longest wall after the Wall of China, the wall or berm is a physical witness of the

war that opposed Morocco and the Polisario Front between 1975 and 1991 after Spain´s withdrawal (Ruiz Miguel et al., 2018, p.16).

16 Hassan II was the King of Morocco by that time. The sand-berm was erected between 1981 and 1971,

dividing the Saharawi people and their territory. Eduardo Galeano describes it as follows, in Muros (2010): “And nothing, nothing is talked about the Moroccan Wall, which for 20 years has perpetuated the Moroccan occupation of Western Sahara. This wall, mined from up till down, surrounded by thousands of soldiers, measures 60 times more than the Berlin Wall. Why is it that there are such high-sounding walls and such silent walls? Could it be because of the informational blockage walls?” The full text is available at:

9

with Morocco17. Up until now, the MINURSO remains to be one of the very few international UN

missions with no mandate to report on human rights violations (Hagen & Pfeifer, 2018, p.21), not having been implemented yet. Since the creation of the MINURSO until now, Morocco has offered economic support, employment and other subsidies for people from Morocco to settle in the occupied territories of Western Sahara, as well as signed trade agreements18 that plunder the natural

resources over the Saharawi territory19.

Last 13th of November 2020, after weeks of peaceful demonstrations led by people of Western

Sahara in the area of The Guergerat20, Morocco sent a military operation in the buffer zone, violating

the 1991 ceasefire agreement. As a result, the Polisario Front declared war on Morocco (UN News, 2020). Currently, the Saharawi people are waiting for support from the international community to help resolve the long-standing conflict by facilitating the celebration of the referendum that was promised three decades ago by the United Nations. Up until now, silence is again veiling the current scenario.

Case presentation: The Sahara Marathon

21The Sahara Marathon campaign is an international sport initiative developed for twenty consecutive years in the refugee camps of Western Sahara22. During its first editions, the Sahara Marathon sport

event was organized by a group of volunteers from different countries together with the Saharawi Ministry of Culture and Sports. Currently, the management of this international sport event is handled by the Spanish association “Proyecto Sahara”23 as well as the Saharawi Arab Democratic

17 This promising political solution, mandate and referendum for Western Sahara´s self-determination is also

known as the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO), and it was approved by the UN Security Council in 1991. More about it can be read in the Security Council Resolution 690, “The Situation Concerning Western Sahara” of 29th April 1991.

18 Trades agreements between the European Union and Morocco are signed such as the “EU-Morocco

agricultural agreement 2012” which includes products from Western labelled as Moroccan. See more in: Western Sahara Resource Watch, 2017: “Label and Liability”: https://wsrw.org/a214x2321

19 including oil exploration, phosphate, agricultural and fishery products among other resources.

20 More information about The Guerguerat area can be found in the following article:

https://www.publico.es/internacional/narcotrafico-milicias-resiliencia-guerguerat-frontera-sahara-occidental-invadida-marruecos.html

21 Information about the Sahara Marathon case study has been gathered from four interviews conducted with

organizers of the campaign as well as available information at the campaign´s official websites: saharamarathon.org; proyectosahara.com and the book “Una huella en el desierto” (Muñoz, 2018)

22 Located in Tindouf, Southern Algeria, the Saharawi refugee camps are administered as state provinces by

different local committees, popular councils and SADR departments which act as intermediary benchmarks for exogenous projects to take place in the refugee camps (Farah, 2009, p.82).

10

Republic Ministry of Sport in coordination with a team of volunteers from different nationalities which swings in between five or six to fifteen or seventeen members every year.

Figure 2. Runners of the Sahara Marathon preparing for the race. Credit: Celia Sánchez-Valladares/2020

The Sahara Marathon campaign takes place for a week during the last week of February, coinciding with the anniversary celebrations of the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic proclamation, on February 27th. On average, around 500 people from 25 different nationalities come to the Saharawi refugee camps to participate in the yearly campaign. During the Sahara Marathon week, participants from the international community24 are hosted by Saharawi families at their houses, distributed

among different state provinces25 and districts26 within the Saharawi refugee camps. The hosting

families receive economic fees as well as food and water provisions for each of the participants27,

apart from voluntary donations.

Most of the humanitarian aid projects created throughout the twenty editions of the Sahara Marathon campaign are related to sport activities and infrastructure, such as sport centres, sports equipment and training projects. Nonetheless, other heterogeneous projects have been

24 The term participants from abroad, runners from abroad and participants from the international community

refer to the same concept and will be included interchangeably within this case study.

25 Also known as Wilayas 26 Also known as Dairas

27 Most frequently, runners who have attended prior editions of the campaign continue staying with the same

11

implemented as well such as a Youth Centre, Internet infrastructures or schools twinning plans28 and

other projects emerged from the runners after they came back from the campaign29.

The current coordination among the team managing the campaign is based on a regular communication between the Spanish association Proyecto Sahara and a facilitator or “change agent” (Schulenkorf & Edwards, 2012, p.4) from Western Sahara who lives in Spain and liaises with the association and the Saharawi authorities, transmitting the association’s different requests and ideas for each year´s editions.

The involvement of different actors before, during and after the campaign includes people from Western Sahara who arrange different aspects of the campaign such as: the selection of runners and athletes from Western Sahara and Algeria30; logistics-employment needed within the campaign

which includes: a health section coordinating medical assistance; checkpoints within the Marathon itinerary31; security and vehicles coordination32; media coverage33; institutional taskforces

coordinating the presence of Saharawi authority members within different key activities34; as well as

a constant coordination with the Saharawi Ministry of Sports.

Apart from the marathon race35, the Sahara Marathon sport event includes a side-event program

carrying different activities throughout the week that complement the marathon event. This side-event program has been varying along the years36. For instance, a children’s race37 is held every

edition, one day after the 42km marathon. Other activities include visits to schools, medical centres and museums; a press conference and race briefing; a Saharawi cultural festival, etc38. The effects

28 Through the school twinning plans, communication exchanges are created among children from Spain and

Western Sahara by post, apart from the gathering of some monetary donations.

29 More information about the projects developed thanks to the Sahara Marathon participation fee can be

found here: http://www.proyectosahara.com/p/nuestros-proyectos.html

30 which varies every year in between 80 to 100 runners from Algeria and 150 runners from Western Sahara. 31 such as supply stations and refreshments points coordinated by the local Saharawi people every two

kilometres throughout the race.

32 monitoring the race and transporting runners to participate in the different key activities of the campaign. 33 with local media and journalists covering the event.

34 such as during the ceremony awards, giving the prizes to the race winners.

35 each participant can choose to run a distance of either 5, 10, 21 or 42 kilometres. All the races are held

simultaneously; the 42-kilometer marathon begins in El Aaiún; the half marathon of 21km starts from Auserd; and the 10 and 5 km races start from Smara. Throughout the whole week as well as during the race, a medical service accompanies and assists the participants if needed.

36 An example of the Sahara Marathon official program can be found in the Appendix 2. The program attached

was facilitated after the interviews conducted for this research by one of the Sahara Marathon organizers as well as a runner who participated in the campaign.

37 The children’s race is also known as “Children´s Olympics”, and is conducted with the aim of raising sport

awareness among children.

38 the awards ceremony; an excursion to the dunes together with the hosting families as well as a trip to the

Wall of Shame in some of the campaign’s previous editions; art workshops; football matches; bicycle races as well as visits to the projects funded by the Sahara Marathon, among others.

12

and implications of the Sahara Marathon campaign and its side-event program will be discussed in the analysis section.

Literature review

This literature review encompasses three fields that inform both the theoretical framework as well as the analysis and findings of the study: sport, tourism, and development. Due to the lack of existing literature focused solely on the Sahara Marathon campaign, this literature review is based on similar research, with the aim of analysing the potential effects and implications of international sports events.

Sport-for-development programs

In this chapter, we first inquire into the characteristics of international sports campaigns, covering the main approaches and key aspects of sport-for-development programs. Subsequently, we discuss the existing gaps and challenges within the field of study.

During the last decades, sport-for-development events have grown exponentially as they have been recognized to be apolitical and flexible tools with universal and transnational meanings, (Darnell, et al., 2019, p. 184). This increased recognition came about after the United Nations embraced sports programs as key instruments for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals agenda39.

From this standpoint, sport programs were seen to be potential tools capable of promoting peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development and empowerment, providing access to justice for all and building effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels (UNOSDP, 2018, p.16). In particular, Marathons appear to be an effective way to induce changes in the perception of oneself and others40.

According to Coalter (2010, p.304), one of the key features of sport programs is their contribution to the development of human capital and social relationships. For Schulenkorf & Edwards (2012, p.8), this is triggered by bringing together unlike groups of people that might have otherwise never shared the same space, thus creating new narratives or discourses in which culturally, politically, or geographically divided societies find commonality and gather around a mutual bond. Besides, the

39 in particular, the SDG Goal 16 of “Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions”:

https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/peace-justice/

40 This was a clear outcome from a research undertaken in 1971 with a group of 8 to 12 people who did not

have prior connections before the race but developed a very high level of harmony and tolerance among each other after their participation (Weissman et al., 1971, p. 669).

13

processes of community cohesiveness prompted by sport events possess a symbolic power capable of triggering intergroup togetherness and reconciliation (Chalip, 2006, p.111).

From this perspective, Franklin (2003, p.48) arguments that, when social cohesion is prompted, a new “communitas”41 emerges as a unique social bond between strangers who happen to have in

common the fact that they are in some way traveling or on holiday together. In this context of conviviality, emotional friendships and cross-cultural interactions are likely to appear (Palacios 2010, p. 875). Furthermore, the unfolding social cohesion triggered has the potentiality to increase support and engagement in social change (McGehee, 2012, p.99).

Specifically, when sport-based initiatives are developed in refugee camps, the United Nations Office on Sport-for-Development and Peace (UNOSDP, 2015, p.5) argues that sport programs can deliver social, psychological, and physiological benefits to the host communities. Named benefits are funds as well as awareness-raising and social mobilization, with the potentiality of creating new synergies and networks (UNOSDP, 2015, p. 17). From a different angle, Norman (2020, p.188) adds a critical theoretical consideration into Sport for Development research when the sport event occurs in sites of confinement, such as in refugee camps. From her perspective, Norman (2020, p.193) argues the need to develop a critical analysis of sport-for-development interventions seeking the way in which these events occur, understanding if they empower the host communities (promoting community cohesion and social acceptance) or further marginalize them.

The latter can happen if the sport-for-development program does not engage certain community members who usually do not take part in sport activities (Hover et al., 2016, p. 21). The non-participation in sport events and/or side-event programs is a challenge that can be overcome by winning local support (Bull & Lovell, 2007, p. 246) as well as involving active citizens who are keen to connect with other members of the community (Misener & Schulenkorf, 2016, p.333).

Another factor identified as a challenge within this field of study is the research of intangible social impacts triggered by sport campaigns. These can be for instance: cultural understanding, social interaction, and community cohesion. Indeed, Bull & Lovell (2007, p. 234) argue that intangible outcomes remain vague and unexplored, being rarely evaluated and less publicly newsworthy compared to the solid facts and figures more usually associated with economic impact. On this matter, Schulenkorf & Edwards (2012, p.6) note that looking beyond direct impacts requires incorporating further strategies into sport intervention projects in order to achieve “wider long-term outcomes for individuals and their communities”. According to Coalter, (2010, p.298) new strategies 41 Schulenkorf & Edwards (2012, p.2), on the other hand, names this concept as “imagined communities” or

14

can be applied by, for instance, including side-events in the sport-for-development interventions. Side events need to be implemented through a bottom-up approach in which local communities take ownership through collaborative decision-making processes. On the contrary, exogenous projects planned and implemented without an interaction, consensus and solution-oriented approach carry the danger of employing a dominant paternalistic approach.

On a different note, it is important to highlight the current growing demand for evidence and transparency in the field of Sport for Development research. For instance, Misener (2015, p.132) argues that there is almost no research addressing the potential utility of small-medium scale sport events. On the contrary, the primary focus has been mainly set on large-scale sport events, which has made a challenge to understand how sport events can be used for more inclusive, positive social outcomes. In this line of research, Chalip (2006, p.123) affirms that more work is needed to explore how post-event euphoria can be translated into emerging social initiatives and community development.

We could then ask ourselves: how are small-medium scale sport programs entailing social change, inclusive participation, and mutual understanding?

To cover this question, it is first important to understand the categories of impact unleashed by sport-for-development initiatives. According to Minnaert (2012 p. 362), sport events can unleash impacts related to individuals, including increased employment opportunities and new networks strengthened between groups of people. Another type of impacts created by sport-for-development initiatives are community impacts, which include participation and social cohesion. In this category, sport programs are understood to enable face-to-face exchanges and dialogues between individuals from across the globe, an aspect that, according to Brown & Morrison (2003, p.74) may contribute to international cooperation, social bonds and mutual understanding. Kersting (2007, p.279) defines these outcomes as social constructs and cohesive forces that hold nations together, shaping their relationships.

Notwithstanding, for sport events to achieve desired positive and sustainable social impacts, sport-for-development initiatives need to be pleasant and/or beneficial, meeting and reflecting the local demands (Schulenkorf & Edwards, 2012, p. 8). Additionally, to sustain the host community's enthusiasm for an external project, the initiators of that venture should recognize the prominent value of freedom-of-action and self-determination from the indigenous population, spending considerable effort in developing cross-cultural consultative and operational guidelines for the event program (Hollinshead, 1992, p. 59).

15

Still, several authors have signalled a lack of studies rooted in local experiences, arguing that an interpretive perspective is missing, with an inadequate understanding of the legacy of sport events and non-giving enough space to the insights, details and depth of the program´s results (Waadenburg et al., 2015, p. 101). In this instance, Simpson (2004, p.690) points out the need to questioning the presumption that by bringing Glocal communities together and by creating new encounters, it may not be sufficient to generate structural changes and cross-community understanding.

In addition to this, Misener (2015, p.136) points out a lack of strategic approach concerning how sport events bring potential benefits and social outcomes for the host communities. Indeed, even though host communities are both the source and the beneficiaries of the social development concept, there is a lack of empirical research on sport events impacts and long-term outcomes (Schulenkorf & Edwards, 2012, p.8). A particular challenge seems to be an absence of impact measurement tools to reflect on the social implications triggered by transient sport events on local societies, which would otherwise guarantee its sustainability (Ziakas, 2015, p.691).

One key feature of this field of study is clear: active community participation is fundamental in sport-for-development programs. As Minnaert (2012, p.364) affirms, host communities and local organizations must be involved throughout all decision-making phases of the sport campaign, including its approach, preparation, organizational processes as well as its legacy and social impact.

Volunteering while doing tourism

In this literature episode, we argue the need for a broader framework that critically assesses the benefits and costs of volunteer tourism events and their contribution to development. Following the previous discussion, it is important to highlight “the centrality of volunteering in sport” (Coalter, 2010, p. 304) and thus, this second chapter will cover the co-relation between sport-for-development programs, volunteering and tourism.

During the last two decades, volunteer tourism has been considered one of the fastest growing and expanding niches from the tourism industry across the world (Vrasti, 2012, p.2). This growth has been caused by the global reach, wide appeal and universal character of volunteer tourism events, as well as an increased willingness from societies to contribute to other communities while being on vacation (Brown & Morrison, 2003, p.73).

Lyons et al. (2012, p.362) define volunteer tourism as a form of ethical tourism in which people pay money to participate in development projects, fostering new encounters that may trigger mutual

16

understanding and respect42. These encounters can at the same time unleash a deeper connection to

the visited place and visited communities (Brown & Morrison, 2003, p.73). According to Misener (2015, p.138), the intangible impact of cross-cultural understanding is ensured when the tourism sport events and their side-event programs are embedded in the host society’s structures, offering opportunities for volunteers to interact with the host communities. Indeed, Mostafanezhad (2013, p. 162) argues that the socializing rationale behind cultural tourism (even if superficial), seems to be the foremost attraction for volunteer tourists. Through affective encounters with cultural others, volunteer tourists want to “make a difference”, promoting one-to-one exchanges and dialogues to understand and appreciate more their global neighbours (Brown & Morrison, 2003, p.74). At the same time, sport tourism events can represent political issues and social inequalities, subsequently increasing social awareness and perhaps leading to a consciousness-raising experience and social change (McGehee, 2012, p.101).

Brown and Morrison (2003, p.77) name the motivation of being part of a good cause while on vacation as “Mini-mission” or “Mission Lite”, defining it as an opportunity for the traveller to have a cultural exchange with local communities, getting in return memories for a lifetime. On the other hand, participating in international sport campaigns involves traveling, which may contribute towards new knowledge, cultural awareness, tolerance and dialogue, reducing racial, cultural or social boundaries and leading towards peaceful outcomes (Raymond & Hall, 2008, p. 532).

Nonetheless, and despite its growing popularity, the field of volunteer tourism is albeit under-theorized (Butcher & Smith, 2010, p.28). This lack of research requests the need for a critical leveraging approach towards the planning and implementing strategies of tourism events before they take place (Bull & Lovell, 2007, p. 236). In this regard, Simpson (2004, p.690) sees a lack of pedagogy for social justice in volunteer tourism events, with the risk of offering a simplistic understanding of reality in which the public face of development is one dominated by the value of western “good intentions”, combining the hedonism of tourism with the altruism of development work.

We could then ask ourselves again, how are these types of events enhancing mutual understanding, inclusive participation, and social change?

According to Hover et al. (2016, p.13), the social impact created throughout volunteer tourism campaigns can be analysed by the sense of trust, hope and reciprocity triggered during the social interactions that emerge from a sport volunteering event. In addition, themes of the campaign's 42 Vrasti (2012, p.6), on the other hand, conceptualizes volunteer tourism as a spontaneous act of kindness in

17

side-event activities must be culturally inclusive, heeding indigenous holistic conceptions of the environment in which they are developed (Hollinshead, 1992, p. 58). This has an important significance as sending organizations need to manage their programs through pre-departure preparation43, orientation and debriefings, providing accountability, and reflecting on the learning

outcomes for these events to become potential catalysts of social change (Ziakas, 2015, p. 699). On the contrary, according to Mostafanezhad (2013, p.151), the legitimization of sport tourism events will be celebrated as a cultural practice that perpetuates the anesthetization of poverty rather than its politicization. If that is the case, the oversimplification of the context may become an act of spectatorship in popular humanitarianism (Darnell et al., 2020, p.4).

According to Wearing (2015, p. 123), this process of commodification, trivialization and over simplicity may also reinforce existing stereotypes and deepen the dichotomy of “Us” vs “Them” if the sport tourism program has not been carefully managed. Indeed, for many of the cases in which no real consultation of the local community is held, the development of sport-tourism events relates to processes of “manufactured consent44” that emerge by power imbalances between the privileged

volunteers and the host communities, creating an atmosphere for the “Othering” (Lyons et.al, 2012, p.371). Raymond & Hall (2008, p.533) add to this view by arguing that a merely facilitated contact with “The Other” does not necessarily lead to respect and long-term international understanding but may instead reinforce stereotypes in the mind of the guest rather than challenge them.

Similarly, Vrasti (2012, p.114) notes uneven power relationships between guests and hosts camouflaged in the “helping discourse” of volunteering events. According to Raymond & Hall (2008, p.531), volunteer tourists assume positions of “expertise” by the neoliberal discourse of traveling to help others as “humanitarian saviours”. This position may unknowingly reproduce cultural images of Western superiority (Palacios, 2010, p. 867) and locate tourists as primary actors for social and economic development in the hosting country where the sport program takes place (Mostafanezhad, 2013, p.161). In this context, volunteer tourists tend to receive more benefits than the hosts (Palacios, 2010, p. 861) carrying a position of benevolence and rationality (Coalter, 2010, p. 298) that represents the challenge of extricating anti-colonial touristic events from their colonial roots (Darnell et al., 2019, p. 136). Moreover, Butcher & Smith (2010, p.27) relate volunteer tourism projects as part of the colonialist and neo-colonialist forces that create new forms of dependency. Similarly, Butcher (2003, p.336) compares the sensitivity of relations between guests and hosts in the same

43 providing contextualization, workshops and information about the historical background and current

situation of the event´s location.

44 The theoretical concept of manufactured consent is further explained in this degree project under the

18

light as relations between countries. According to him, volunteer tourists become a vehicle for cultural imperialism, bringing western culture to bear on the indigenous and local environment. Within this field of study, one thing seems clear: the implementation of sport and volunteering events should not be automatically assumed as beneficial for both guests and hosts communities (Raymond, 2008, p. 48). On the contrary, sport-for-development initiatives need to be strategically planned, managed, leveraged and evaluated to achieve long-term positive outcomes (Schulenkorf & Edwards, 2012, p.8). In addition, a key strategy for sport volunteer programs to enhance positive social impacts is community mobilization and partnerships with local organizations, embracing the core values of residents and host communities (Taks et al., 2015, p.3). Involving local community members in the different event processes safeguard the respect of the hosting community culture, values, norms, and opinions as well as increase the public support of the event itself (Misener, 2015, p. 144). Furthermore, evidence suggests that sport tourism programs must ensure a bottom-up endeavour with the local community, guaranteeing active and equal participation as well as a reached intergroup consensus through all the event phases (Ziakas, 2015, p. 693). As a result, awareness building and social interaction between hosts and guests appear to be more profound (Wearing, 2015, p. 123).

To realise a sustainable form of development triggered by sport tourism events, there needs to be real community involvement and intersectoral cooperation, in which local residents receive a higher number of responsibilities over time, increasing their engagement and active participation as well as having the leading role over the project in the long-term (Schulenkorf & Edwards, 2012, p.5). Lastly, for this long-term sustainability to be applied, volunteer sport events need to build an analysis of the legacy left behind, evaluating what has been done, being aware of the potential benefits and costs and learning from the past to improve the event in the future (Hover et al., 2016, p.11).

Theoretical framework

This degree project draws upon the participatory communication approach, including the paradigm of “Doing good vs looking good” as an analytical category. Throughout this theoretical frame, and including concepts such as community engagement, indigenous knowledge, active listening and manufactured consent, this study investigates the potential impacts and implications of the Sahara Marathon campaign, analysing the international sport event approaches to Social Change and Communication for Development. This theoretical framework will provide a structure for what to

19

look for in the data and, as Kivunja (2018, p.47) states, it will help to make connections between abstract, concrete and reflective elements of the information gathered within the research process.

Participatory communication approach

The participatory approach to communication, also known as community engagement approach, is described by Manyozo (2012, p.18) as a fundamental component of Communication for Development that allows for the articulation and incorporation of multiple voices and interests in the development intervention. Through community-based and bottom-up approaches, the participatory community approach conceives communities as agents of change and not subjects of aid, developing strategies that place the local citizens at the heart of each development process. Thereby, local individuals are actively involved in the design, planning, management, implementation, and evaluation phases that affect their lives, defining themselves what they value and their own interests (Manyozo, 2012, p. 194). In this way, the role of communication is not to disseminate information in order to change individual behaviours, but to promote the inclusive expression of the communities´ needs and wishes (Scott, 2014, p.49).

The participatory development paradigm has the capacity to stimulate citizen-driven social change processes by empowering individuals to be engaged and act (Tufte, 2017, p.40). Thus, the central focus of participatory communication is the empowerment of citizens through their active involvement in the identification of problems, the development of solutions and the implementation of new strategies. This is done through a two-way communication and grassroots process-focused approach, which enhances structural change and collective action (Tufte, 2017, p.157).

Dialogical processes and collective action

Following the participatory communication approach, voice and active listening are recognized as two key factors that need to be embedded within any participatory development and communication practices for a long-lasting commitment towards empowerment and social change. Couldry (2010, p.15) defines voice as a value and process that provide accountability for personal stories and experiences to be told but also be listened through storytelling, dialogues and discussions. On the other hand, Lacey (2013, p.14) observes that: “Without a listening public, opened to give those voices a hearing, there can be no guarantee of the plurality of voices or the exercise of freedom of speech”. In this framework, Tufle & Mefalopulos (2009, p.20) remark the significance of providing reflective time and space for local communities to define their problems, voice their concerns, articulate their needs, formulate solutions and act on those by and for themselves.

20

As a result, participatory communication practices and dialogic spaces are fostered through the exercise of citizen engagement, uttering the voices of local communities and inciting social change (Tufte, 2017, p.122). Specifically, horizontal communication appears to be a benchmark within any participatory development process, facilitating the emergence of new linkages and networks. According to Heimann (2006, p.605), horizontal communication builds a field in which everyone communicates and interacts at an equal level, regardless of their context or status. For this to be achieved, a collective dialogical process must be applied within all stages of a participatory development project, empowering all stakeholders to be actively involved, shaping decisions and influencing the objectives and outcomes of the development initiative (Tufle & Mefalopulos, 2009, p.26).

Community participation in a development intervention

Tufle and Mefalopulos (2009, p.15) specify four categories of community participation within a development project. The first one, empowerment participation, is characterized by joint decision making, an equal partnership between stakeholders during the development intervention as well as open and interactive community practices, knowledge exchange and ownership led by the local communities. The second category, participation by collaboration, depends on outsider facilitators who pre-determine the project objectives. In this collaborative approach, horizontal communication and capacity building are attained for all stakeholders, requiring an active involvement in the decision-making process to decide on how to achieve the pre-set goals, which offers the potentiality to evolve into an independent form of participation.

The last two categories are defined as participation by consultation and participation by information (Tufle & Mefalopulos, 2009, p.15). Also known as tokenism, participation by consultation consists of an advisory process in which outsider stakeholders possess the decision-making power and consult the primary local stakeholders, who are the ones providing answers to the questions exposed. After informing and consulting the primary stakeholders, outsider parties are not required to include the local input into practice. Lastly, the least participatory approach is participation by information, in which primary local stakeholders are just informed about what the intervention consists of, barely having space to give their feedback and not influencing in any decision-making processes.

Among these categories, Govind and Babu (2017, p.6) add a new level of participation known as manufactured consent. In this new approach, an agreement is manufactured to legitimize the implementation of a development project, not through free choices but unequal power relations and conceptions of “common sense”, from which primary stakeholders are left with not much free choice to opine differently (Govind & Babu, 2017, p.17). Through manufactured consent, external change

21

agents drive the development processes offering very little or no room for participation, as well as a lack of knowledge and information (Tufle & Mefalopulos, 2009, p. 16)

If manufactured consent or passive participation applies, and a development program is not implemented through participatory communication, the local population would become objects of development instead of change agents with autonomy, and the aid relationship would turn into “an ill-concealed extension of the colonial rule” (Hossain, 2017, p.88). An example of it applies with the concept of “Clanship”, a term opposed to community participation and engagement in which organizational management is distributed between just a few members, becoming more of a business-like initiative that is characterized by “a capitalistic commoditisation of workers” (Mannan, 2015, p.152).

Sustainable partnership approach & conviviality

One of the theories that inform this study is the sustainable partnership approach model of development. The partnership approach involves collaborative planning and decision-making processes through dialogue, community-led projects and processes of communication and social change based on equal power relations (Manyozo, 2012, p. 191). As Wilson (2018, p.67) argues, the partnership approach is built from an alternative development discourse that questions the development assistance enthusiasm and the established aid hierarchies between donors and beneficiaries. For this partnership model to be effective, it needs to be applied away from hierarchical and paternalistic narratives of rescue (Wilson, 2018, p.73).

Another theory that guides this study is convivial solidarity. Conviviality refers to the Spanish term “Convivencia” and represents a bottom-up, local and participatory approach applied through interconnectedness, diversity and mutual aid (Hemer et al., 2020, p.8). As Encarnación Gutiérrez (2020, p.118) describes, conviviality may experience simultaneously the paradox of proximity and distance, as each given encounter requires a contextualization to see existing power relations and imbalances as well as structural divisions that sustain a “living together” but also a “living apart”. These emerged “new communitas” (Franklin, 2003, p.48) are capable of breaking down social rules and prompt multicultural exchanges, which may also enhance community participation, socialization and networking (Chalip, 2006, p. 124).

On the other hand, Deniz Neriman Duru (2020, p.133) positions convivial solidarity as an outcome from practices of collective work, including face to face social interaction, a shared sense of humanity and social justice. Following this principle, convivial solidarity gives space, attention, and legitimacy

22

to local communities but also a narrative of humanization based on a “Collective We” (Chouliaraki, 2013, p. 28).

Both research frameworks bring us to the context of communication for development and social change, stating the need to get rid of the saviour complex, strengthening people’s stories, informing citizens about different ways in which they can contribute to social change, and appealing to empathy rather than compassion (Waisbord, 2018, p.175).

When Looking good overpasses Doing good - current trends and the White

Gaze of development

Whist participatory communication processes equalise doing good interventions by challenging power relations and “giving voice to the voiceless” (Tufte, 2012, p.79), non-inclusive development interventions evolve into looking good interventions, new forms of dependency and hegemony (Pieterse, 2010, p. 212). In particular, when “looking good” overpasses “doing good”, development interventions become a spectacle of public appearance, lacking accountability towards the actual benefits for the local communities and missing a pathway towards positive social change (Wilkins, 2018, p.76). According to Waisbord (2018), looking good practices equate development aid interventions with charity projects, perpetuating “development as a Western story, casting the Global South as secondary characters and dismissing the fact that social change demands tackling long-standing inequalities” (ibid, 2018, p.173).

Tufte (2012, p.153) attributes looking good interventions to the current crisis of development; a crisis of participation and inclusion in which people do not have an influence on the decisions that affect their lives. Researchers such as McEwan (2018, p.151), define the discursive power of development as a hierarchical, oversimplified and homogenized vision of the world that is rooted in European imperialism and false assumptions of western domination and superiority. This philosophy and power hierarchies of “first the West, then the rest” (McEwan, 2018, 135), evokes “The Otherization of the world” (Clammer, 2012, p. 91), perpetuating stereotypes instead of challenging them (Tufte, 2017, p.106). As a result, the dichotomy of “Us” vs “Them” contributes towards a pattern of delegitimization and dehumanization, portraying people by a sensationalistic depiction of suffering (Wright, 2018, p.92).

In this context, development interventions are performed “in favour of a selected group and at the expense of another group or the environment” (Tavernaro, 2019, p. 20), as distant and oppressive acts (Desai et al., 2014, p. 46) that can trigger compassion fatigue from “ironic spectators of vulnerable others” (Chouliaraki, 2013, p.3). Pailey (2019, 733) refers to this paradigm as the “White

23

gaze” of development: a colonial and paternalistic frame of the field that assumes whiteness as a superior reference of power, in which “white is always right, and west is always best”. Specifically, the “white gaze” conditions the theory and practice of development by categorizing different parts of the world into oppositional judgment binaries and unequal power structures (Pailey, 2019, p.734).

Subverting the colonial gaze, shifting towards Indigenous Knowledge

The perpetuating inequality within traditional development discourse can be challenged by acknowledging the white gaze of development and transferring the agency to the global South to express authority, make decisions and participate as active subjects in the processes of development and social change (Tacchi, 2016, p.120). From localism, alternative ideas, text and imaginary, McEwan (2018) highlights the necessity of new types of knowledge and politics of representation that contests the Western cultural hegemony and suppresses the gap between North and South, “disrupting the power relations of speaking for distanced others” (ibid, 2018, p.317).

Indigenous knowledge is a key feature embedded within the participatory communication approach as it represents plural and dynamic voices from the local communities and brings innovative solutions to development challenges (Manyozo, 2012, p. 80). According to Clammer (2012, p.11), indigenous knowledge (IK) represents a shift of the developmental paradigm, subverting Eurocentric and hegemonic representations of the world, while empowering local communities through participation and autonomy. Significantly, IK places the community at the centre, expanding knowledge creation and “giving ownership on the part of the indigenes” (Clammer, 2012, p. 40). This people-centred approach (Clammer, 2012, p.11) supposes a shift from exogenous to endogenous development interventions, unleashing new community networks, actors, voices and forms of participation (Clammer, 2012, p. 67).

Research design framework

According to Gorard (2013), research design is a way of organising a research project in order to maximise the likelihood of generating evidence that provides a convincing answer to the research questions (ibid, 2013, p.6). This research project aims at finding out the potential effects and implications of the Sahara Marathon campaign from the perspectives, insights and experiences of human right activists from Western Sahara as well as runners, freelancers and organizers who have or have had a connection with this international sport event. To this end, qualitative research methodologies were used to gather data from the respondents.

24

Methodological approach

The degree project methodological approach consisted of in-depth interviews conducted within a case study of the Sahara Marathon campaign. I decided on this qualitative research method as it aligns with the aim of finding out “how” and “why” (Kulothungan & Oham, 2019, p.12) this campaign may be contributing to a social change in the question of Western Sahara. The methodological perspectives for this research project are constructivist, narrowing the gap between concrete observations and abstract meanings by using interpretive techniques (Markham, 2012, p.6), where meaning-making has been a continually unfolding process (Holstein & Gubrium, 1995, p.2).

Due to the informational blockage about Western Sahara´s situation, one of the challenges I have encountered is the lack of multiple data and literature sources for a descriptive interpretation on the potential implications of the campaign. Thus, to provide solidity to this methodology, and following the conceptualization that defines interviews as one of the most important sources for data in qualitative case study research (Alpi et al., 2019, p.2), I chose in-depth interviewing methodology to contribute to the external reliability of this case study, as it helped me to have a better understanding of the implications of the campaign as well as new perspectives and reflections that I did not anticipate before the interviews. For instance, one of the interviewees from Western Sahara answered the interview questions after having gathered first the opinion of seven young people and three elderly women living in the Saharawi refugee camps of Auserd, El Aaiún and Smara. Prior to our interview, she wanted to ask other Saharawi people about their experiences regarding the campaign, with the aim of “gathering more authentic answers from local people who may feel more comfortable talking to someone they already knew before” (Leila, personal communication, October 11, 2020). Her support and insights shared have undoubtedly enriched the data gathered in this degree project, adding new narrative perspectives.

Finally, the design of the interview guide45 consisted of open-ended questions, inciting the

participants to shape the form and the content of what was said (Holstein & Gubrium, 1995, p.3), and thus allowing enough room for spontaneous answers and questions not initially planned to be explored (Brinkmann, 2008).

Selection of participants and research conduct

A total of 23 participants were interviewed for this degree project, consisting of ten Saharawi human rights activists, four organizers of the Sahara Marathon, two freelancers who have participated in more than one edition of the campaign as well as seven runners coming from Spain, Sweden and 45 An example of the interview guide used with the Saharawi participants of this study can be found in the

25

Italy. The selection of participants was based on people who have and/or have had a connection with the Sahara Marathon in any of its twenty editions. Throughout the research process, I reached out by email to project representatives of different Saharawi organizations such as NOVA46, AFAPREDESA47

and UJSARIO48 since I wanted to include first-hand representative viewpoints from different Saharawi

organizations about the campaign as well as in-depth information on Western Sahara´s situation. As an example, I managed to talk to the Director of Cooperation and Program Coordinator at the Saharawi Ministry of Sport and Youth, who has been involved in the development of the Sahara Marathon for more than ten years.

Besides, last February I visited for the first time the Saharawi refugee camps as a volunteer of Emmaus Stockholm49, supporting the different activities and visits organized by Emmaus during the

same week of the Sahara Marathon. The visit to the camps allowed me to establish a first contact with several people from Western Sahara and runners from abroad. Few of them collaborated in this study and, thanks to their support, I managed to reach out to other runners who have participated in one or more editions of the campaign, thanks to the snowball word-of-mouth effect. At the same time, I researched on the Internet different contact details of Saharawi human rights activists and associations as well as a celebrity from Sweden who participated in the campaign. Positively, most of the people responded showing an interest to participate in this study.

The interviews took an average of 45 minutes to 90 minutes and were conducted through WhatsApp and Facebook messenger as well as by international voice calls at the time that was most suitable for the participants.

Ethics, reflexivity and limitations

Before submerging into this qualitative research project, I reflected on the potential bias of my subjectivity as a researcher. Two years ago, I collaborated in Emmaus Stockholm as a communication´s trainee for six months, mainly working on the issue of Western Sahara. Even though I am aware that the knowledge acquired during my internship may have biased my perception of the conflict, I attempted my best to use that as an advantage as it provided me with an insight and possibly better understanding of the participants' experiences, beliefs, and opinions.

46 The Saharawi Non-Violence Association was created in 2012 and consists of approximately 270 members

that actively work for a dialogical and non-violence approach, https://www.facebook.com/nova.westernsahara

47 AFAPREDESA is the human rights Association of Families of Saharawi Prisoners and Disappeared,

http://afapredesa.blogspot.com/

48 UJSARIO is the Saharawi Youth Union organization operating from the Saharawi refugee camps in Tindouf,

Algeria, http://www.ujsario.com/

49 Emmaus is an organization that works with development and communication advocacy projects, with a

26

In addition, throughout the research process and to the best of my capabilities, I tried to carefully follow all steps to guarantee the ethics of research. First, informed verbal consent to record and use the interviews for this degree project was obtained from each of the interviewees at the start of the conversation. Thanks to audio recording the interviews, the conversation flow was natural, giving me more time to reflect on the previous answers and to arrange the order for the rest of the questions. Additionally, the confidentiality of the interviews and the anonymity of the participants from Western Sahara and others who could relate to Saharawi activists were guaranteed at all stages. In order to do so, I replaced the name of the participants with nicknames, anonymizing them both in the transcripts attached as well as in the analysis and findings section.

The interviews were held in English and Spanish50, although one of the interviews was held in Arabic,

with the help of an interpreter. Each interview was transcribed afterwards and, the ones held in Spanish and Arabic have been also translated into English to allow for a comprehensive analysis. This has eased the process for an adequate interpretation of the reflections and experiences shared during the interviews.

At the beginning of each interview, I introduced the main subject of the study, the aim of the research as well as my interest and passion to find out the answers to the research questions. All the data sources were treated with diligence and impartially to ensure reliability in the study. Lastly, the transcribed51 interviews have been analysed qualitatively by highlighting different themes, insights

and quotes that are included in the following section of analysis and research findings.

Analysis and research findings

The main findings of this research are presented through five major chapters that emerged from the experiences and perceptions shared during the interviews: visibility as a weapon against silence; messengers for freedom; conviviality as a hub for new gazes and networks; being present but not as hosts; and looking good while doing solidarity work. All data gathered from the in-depth interviews has been analysed and discussed in relation to the theoretical framework and research questions.

50 Spanish is the second official language in The Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic. More information about it

can be read in the following article: https://www.farodevigo.es/opinion/cartas-al-director/2015/08/29/espanol-sahara-occidental-16826316.html