Feeling Connected;

Supporting remote non-verbal communication for

infants born with Deafblindness

Alexandra Veskoukis

Interaction Design

Two-year Master’s Program Thesis Project I, 15hp Spring 2020

Supervisor: Henrik Svarrer Larsen

Abstract

The purpose of this design project is to propose qualities in communication that could be considered when developing an assistive communication device for infants with

Deafblindness in order to make the infant feel connected to the context and for the caregiver to feel connected to the infant, without having physical contact.

In order to investigate the problem definition, What qualities could a device have that

supports remote interpersonal non-verbal communication? and the two sub-questions: How can the device instill a sense of security, safety and support? and: How can an infant with Deafblindness sense communication?, human-centred design methods were used

through a double diamond process.

The design process resulted in six qualities, Direct, Spatially informative, Fluent, Individual,

Turn-taking, Feedback and a final concept supporting these qualities.

Keyword

Interaction design, Assistive communication, Non-verbal communication, Haptic communication, Deafblindness, Autonomy

Content

Abstract Content

1. Terms ... 5

2. INTRODUCTION ... 6

2.1. Aim and problem definition ... 6

2.2. Stakeholders ... 7

2.3. Structure of the report ... 7

3. BACKGROUND THEORY ... 8

3.1. The need for physical contact ... 8

3.2. Communication ... 8 3.3. Existing practices ... 11 4. METHODS ...16 4.1. Project Plan ...16 4.2. Discover phase ... 17 4.3. Definition phase ... 17 4.4. Development phase ... 18 4.5. Delivery phase ... 18 5. DESIGN PROCESS ... 18 5.1. Discovery phase ... 18 5.2. Definition phase ...19 5.3. Development phase ... 24 5.4. Delivery phase ... 31

6. MAIN RESULTS AND FINAL DESIGN ... 35

6.1. Main results ... 35

6.2. Final design concept ... 36

7. DISCUSSION ... 38

8. CONCLUSION ... 40

9. REFERENCES ... 42

1. Terms

To create clarity in this thesis project, I will define the following terms used throughout this paper.

Deafblindness – The Nordic definition of deafblindness is “a combined vision and hearing

impairment of such severity that it is hard for the impaired senses to compensate for each other” (Nordens välfärdcenter, 2020, paragraph 1). Individuals born Deaf or who become Deaf in early childhood, refer themselves as Deaf with a capital D (Donaldson & Rutter, 2017). In this project, Deafblind, with a capital D, refers to individuals born with

Deafblindness, while deafblind refers to individuals who was not born with Deafblindness.

Infant - In this project one of the target groups are infants who are born with Deafblindness.

When born with Deafblindness, many infants tend to have other syndromes that either causes the disability or is additional to the disability. Depending on the syndrome, cognitive development varies, and the learning curve looks different with each infant’s cognitive health and personality (Gleason, 2017; Preisler G. , 2005). Therefore, the term infant in this paper does not refer to a specific age group but the level of cognitive development. The term Infant refers to an individual who has the same cognitive development as to an individual in the infancy period. The infancy period is after birth and before developing a language.

Caregiver - In this project, the other target group is caregivers to infants who are born with

Deafblindness. When referring to caregivers in this paper, it does not reflect the mother or father to the infant but can also reflect other safe relationships in the home environment, e.g. sibling, grandparents or therapist.

2. INTRODUCTION

Every year 6-8 people are born with Deafblindness in Sweden and there are around eighty different syndromes that can cause this disability (NKCDB, 2020). Depending on the syndrome, cognitive development varies, and the learning curve looks different with each child's cognitive health and personality (Gleason, 2017).

According to Tenesaca, Yun Oh, Lee, Hu & Baiit it is important to expose the infant to a form of communication the day the infant is born. However, because over 90 percent of infants with Deafblindness have caregivers with intact hearing who are usually not fluent in sign language, an established form of communication is delayed and can cause challenges in the linguistic, cognitive and social-emotional developments (Tenesaca et al., 2019). As the caregiver cannot rely on hearing and sight, non-verbal communication forms, e.g. signs, gestures, touch cues, object cues, tactile symbols, movement cues and/or contextual cues take place before reaching an age where the child can start learning tactile sign language

(Cawthon, 2017; Gelling, 1999; Withrow, u.d.). Non-verbal communication forms mostly require physical contact by either e.g. using hands, movements, touch or giving objects or symbols to the infant (Preisler & Ahlström, 1997; Withrow, u.d.).

By communicating and interacting with the infant, a trusting relationship where the infant feels secure, safe and supported is established, which is needed to create a base from where the infant later can explore the world from. In order to communicate and interact with the infant, the caregiver needs to keep the infant physically close to their body for the infant to feel their movements. The caregiver is the greatest tangible support because it allows for fluency and social interaction (Cawthon, 2017; M. Estenberger, personal communication, April 24th, 2020; NKCDB, 2019; raisingchildren, 2019). However, it is not always possible to obtain physical contact and it is at times like these the infant can feel stressed, anxious or alone in the world, as the world ends at the infant's fingertips (NKCDB, 2019).

Being a caregiver to an infant with disabilities can be challenging, therefore caregivers can get informational and emotional support from centers, organizations and communities

(raisingchildren, 2019; Sense, 2019). But according to my research there is a lack of tangible support in the form of a physical device that can support the fluency and social interaction in communication when physical contact is impossible.

2.1.

Aim and problem definition

Gleaned from literature and fieldwork, the value of this design project is creating a secure, safe and supportive base for the infant, where a healthy relationship between caregiver and infant can prosper. The target groups are infants born with Deafblindness and the caregivers to such infants. In today’s situation, infants with Deafblindness do not have access to

information about who and where individuals in their surroundings are, unless they have physical contact with the individuals.

The design challenge in this project is to create an assistive communication device that could inform the infant about who and where the caregiver is and their location in their immediate environment. By doing so, the aim is to create a feeling of connection between the infant and the caregiver.

The following problem definition intends to generate knowledge in the field of assistive communication within Interaction design.

What qualities could a device that supports remote interpersonal non-verbal communication for infants with Deafblindness have?

With qualities, this design project refers to qualities in communication. Remote refers to not having physical contact but being in the immediate environment. Interpersonal

communication refers to having knowledge of the individual’s personal and unique way of

communicating.

In order to answer the problem definition, this design project has investigated the following sub-questions: How can the device instill a sense of security, safety and support? and, how

can an infant with Deafblindness sense communication?

2.2.

Stakeholders

This design project is in collaboration with Certec. Certec is part of the Department of Design Science, Factuality of Engineering at Lund University which undertakes research and

education on Rehabilitation engineering and design. In order to proceed with this design project, it was important for me to share Certec’s ambition, which is in achieving better opportunities for people with disabilities by engaging technology and to “emanate from the individual’s perspective and situation”(Certec, 2015, paragrapgh 3). Certec has also

contributed with the project suggestion:” Haptic toys or communication device; Persons who are born deaf-blind have severe difficulties in learning how to communicate and to explore their surroundings. What would a digital system look like that lets a child with deaf blindness explore or communicate haptically (with the touch sense)? This project could take on various forms – like interactive toys or remote haptic communication” (Certec, 2020, paragrapgh 5). This design project originates from the above mention project suggestion. Furthermore, Certec also contributed with contacts from the The National Resource Center for

Deafblindness (NKCDB).The contacts from NKCDB are three experts who have contributed to this project with both theoretical and experiential values, preferences, practices and knowledge regarding Deafblind communication, assistive devices and child development, presented both in the background theory and in section 5.2.1.

2.3.

Structure of the report

In section two, a presentation of the chosen subject, the design challenge and problem

definition are given. Section three is a presentation of the theoretical background followed by existing practices within the chosen field. In section four, the design process and methods with the reasoning of applying them are given. In section five a more detailed description of the methods, the results and implications are given. In section six the main results and a final design is presented. In section seven a discussion of said results and design are given. In section eight, the conclusion of this design projects is summarized.

3. BACKGROUND THEORY

This chapter will provide a theoretical framework for this project and an overview of existing practices as references to previous work investigating non-verbal communication.

3.1.

The need for physical contact

For an infant born with Deafblindness to obtain good interactions with the surroundings and the caregivers, the infant needs to be in a comfortable position where maximum physical contact with the caregiver is possible. Whenever the caregiver does not have maximum physical contact, it is important to have some sort of physical contact so that the infant can have access to information, which creates a sense of safety. A caregiver can continue

obtaining the physical contact by sitting close to the child or by keeping some kind of physical contact , as long as it is not intrusive or sudden (K. Jönsson, personal communication, April 22nd, 2020; NKCDB, 2019).

When having physical contact with an infant with Deafblindness it is important that the touch is not experienced by the infant as intrusive. Intrusive areas to touch can be the head and hands, while shoulders, back and arms can be experienced as less intrusive. Even though the infant's hands are the greatest tools for exploring the surroundings, they are also body parts that can experience touching as intrusive, therefore it is important to let the infant explore the surroundings by itself and not touch the infant's hands to teach or show the infant the objects. The caregiver should instead place their hands underneath the infant's hands to support the infant in exploring (NKCDB, 2019).

3.2.

Communication

As the main purpose of this research is to investigate how infants and caregivers

can communicate remotely, it is important to define communication. Communication is the general process of forwarding verbal or non-verbal information or a message from one place or person to another. It cannot develop in solitude but needs to have two or more active participants (Cambridge dictionary, 2020; NKCDB, 2019).

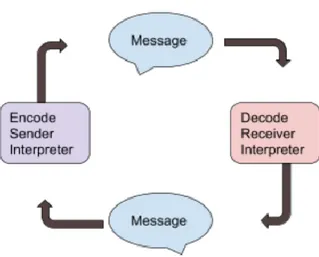

3.2.1. Impersonal vs. interpersonal communication

West and Turner explains that communication can either be impersonal or interpersonal (West & Turner, 2009), describing that impersonal communication is when

communication is based on social or cultural information, meaning that the individuals do not know each other but are basing their interaction on social context, age, gender or the situation. Interpersonal communication is the process of forwarding information between two participants simultaneously, striving to create and sustain a shared meaning.

“When individuals in an interpersonal communication increasingly predicate their behavioral choices during interactions on psychological level knowledge, that is, knowledge about the unique personal characteristics and history of their partners, their interactions become more interpersonal and less impersonal (Berger, 2015,p.8)”.

Both Karin Jönsson and Monika Estenberger from NKCDB explained that infants with Deafblindness communicate in different forms all the time by behaving in different ways. Also in a relationship between an infant with Deafblindness and a caregiver, behaviors of communication need to be seen and confirmed through imitation or another way of

confirmation, interpreted and then negotiated by the caregiver and the infant, in order to find a common understanding (appendix 2 &3).

“Usually Deafblind people express themselves in ways we cannot see, we who are traditionally bound to signs from hands and head. Infants with Deafblindness express

themselves a lot through the rest of the body and when we see those expressions, which could be a body movement or gesture, we must be able to confirm them because we cannot just give them a smile, they will not be able to perceive that. We have to physically confirm it and after that we can transform their own expressions to a more conventional tactile signs” (M.

Estenberger, personal communication, April 24th, 2020, paragrapgh 5).

To understand and to be understood are human basic needs that are very important for an infant's cognatic, emotional and social development and for a caregiver not to feel powerless (Chen & Haney, 1995; Sense, 2019). How we behave always communicates something and we always behave in some way (Watzlawick, Bavelas, & Jack, 2011).

“We cannot not communicate. Actively or Inactively, words or silence all have a message value; they influence others and these others, in turn, cannot not respond to these

communications and are thus themselves communicating” (Watzlawick et al., 2011, p.30). When an infant with intact hearing wants to establish contact with the caregiver, he/she can do so by giving out a sound. In return, the caregiver answers, acknowledging the attempt of communication. In the book, Prosody in Interaction, Barth-Weingarten, Reber and Selting describes that the interplay of prosodic features in the sound, such as pitch, loudness, tempo and rhythm, will let an infant with intact hearing and caregiver to start establishing

interpersonal communication fluently by interpreting and negotiating a common understanding of the prosodic features. When the infant has a more fundamental

understanding of interpersonal communication, which happens around when the infant is 12- 18 months of age, verbal-symbolic communication begins (Barth-Weingarten et al., , 2010; Stern, 1995).

Interpersonal communication does not happen automatically in a relationship, the

individuals must engage in the process of developing an understanding by being aware of the communication form and what is being communicated in order to give feedback to make sure the person is being understood (NKCDB, 2019). According to the interactional model of communication, feedback is the quality that makes communication interactive between two people and can be both verbal and non-verbal (West & Turner, 2009).

Another quality of the interactional model of communication is that it is turn-taking.

Turn-taking is very important for deafblind communication in order to structure a frame so as to

identify who the sender and who the receiver of the message is (M.Estenberger, personal communication, April 24th, 2020; NKCDB, 2019).

3.2.2. Non-verbal communication

If behavior is communication, then non-verbal communication is every behavior in the universe that does not use words (Hinde, 1972). Within interaction design, Cooper, Reimann, Cronin and Noessel refer to behavior in artefacts, environments and systems as product and system behaviors (Cooper et al., 2014). Therefore, it is important to set the base for what non-verbal communication is in this design project. Non-verbal communication in this project refers to Hinde’s description of human behavior i.e. when an individual behaves in a certain way to achieve certain feedback; it adjusts accordingly to facts, to gain and preserve skills and to prioritize different possible courses of actions (Hinde, 1972).

Tactile sign language is a non-vernal communication form. When communicating using tactile sign language, one is signaling onto another person's hand and to do so a turn-taking structure is very important to achieve by using a method called listen- and speaking hands. That means that the listener place their hands above the speaker’s (NKCDB, 2019).

In the book “Med kroppen som redskap” which was developed by the Chizombezi Deafblind Center together with the Norwegian foundation Signo, they describe, that contact with a child with Deafblindness is established by physical contact, to “knock before you enter” (NKCDB, 2019, p.20). Each infant reacts differently to touch, therefore it is important to find what the infant perceives as less intrusive. When contact is being established, people with

Deafblindness, like most individuals, usually want to know who it is” knocking” To show who it is, the person with Deafblindness could touch the persons face or could recognize a cue that describes who it is, e.g. mums hair band or a touch cue, which creates security. (NKCDB, 2019; Withrow, u.d.).

Figure 1. An illustration of the interactional model of communication.

3.3.

Existing practices

This section presents an overview of existing practices. Two are examples for individuals with deafblindness who have linguistic skills, Mobile Lorm Glove and the DB-hand. Two examples for individuals without linguistic skills, Heartbeat and An Interactive Playmat for

Deaf-blind infants. An analysis of the latter’s strength, what opportunities the examples provide

and their weaknesses. Finally, an example that is not within the field of interaction design but is an inspirational practice that support the fluency in communication followed by an analysis of its strengths, opportunities and weaknesses.

3.3.1. Existing practices for individuals with linguistic skills

There are many different assistive communication devices for individuals with deafblindness who have linguistic skills in form of wearables. Two examples of existing practices are the

Mobile Lorm Glove and the DB-hand.

3.3.1.1. Mobile Lorm Glove

The Mobile Lorm Glove is a prototype made in a participatory design process and aims on providing individuals with deafblindness the possibility to communicate using Lorm manual alphabet without having to obtain physical contact with the other person. The assistive communication device lets people with deafblindness communicate remotely via SMS by composing messages on the palm of their glove and sending it to the recipient. The glove consists of fabric pressure sensors in the palm of the glove and vibrating motors on the back that lets the wearer perceive incoming messages. Although the research continues in verifying the effectiveness and functionality of the glove system, the overall feedback of the prototype from the individuals with deafblindness were positive and had caused a “euphoria around the lightweight device and its textile interface” (Gollner, Bieling, & Joost, 2012, p. 130).

Left to right: Figure 2a) Vibrating motors on the back of the glove.

3.3.1.2. DB-hand

Caporusso's aim in developing the DB-hand was to focus on giving individuals with

deafblindness autonomy in communication, access to information and mobility by creating an assistive hardware and software system. He saw the need for assistive devices that do not focus on sign language sensors, because both sign language and fingerspelling are visual methods and therefore excludes people with deafblindness. Caporusso describes assistive technologies that convert text messages to manual alphabets as being “more expensive than efficient” (Caporusso, 2008, p.446). Instead of sign language or fingerspelling, the DB-hand uses the Malossi alphabet, which uses different touch-and pinch points on the palm of the hand of the recipient. The DB-hand consists of embedded sensors and actuators that

translate text messages into tactile communication and vice versa. The vibrating actuators are cheap and easy to embed in wearables making the glove flexible, easy to wear and

comfortable. It uses the structure of turn-taking so that an input signal and output tactile communication never interfere with each other as they are not simultaneous. The DB-hand's software converts and interprets the hardware impulses. To verify the effectiveness of

communication, mock-ups of the device were tested during the development. The results of the finding regarding the software was that a system owe to be designed to be adaptive according to the users learning speed of it. (Caporusso, 2008).

3.3.2. Existing practices for individuals without linguistic skills

As many assistive communication devices are for individuals with linguistic skills, it was harder to find good examples that gives infants with Deafblindness the same autonomy as the

Mobile Lorm Glove and the DB-hand does. Two examples that focuses on giving individuals

with Deafblindness autonomy is the Heartbeat and An Interactive Playmat for Deaf-Blind

Infants.

3.3.2.1. Heartbeat

Heartbeat is a technological device developed by Saskia Damen and Ingrid Korenstra to

prevent social isolation and reduce insecurities among people with deafblindness and

especially the ones with cognitive disabilities ( Saskia & Korenstra 2015). The technical device consists of a small box with a big red button and an electronic pulsator that transmits a signal to a pager worn by the caregiver. Once the button on the box is pressed, a signal

Left to right: Figure 3a) Image of touch and pinch points of the Malossi alphabet. Figure3b) Photo of the DB-hand.

the pager (caregiver) is. If the pager is close by, the vibrations are stronger and if the pager is further away, the vibrations are weaker. The idea originated from when an eighteen-year-old boy born with Deafblindness got very worried when he did not know where the staff was. In those situations, he started to undress himself naked because he knew then that the staff would come to his aid. Since the boy did not like loose lying objects around him, the

researchers had to place the device on his body. It took three months for the boy to accept the device around his waist but once he accepted it, he became calmer by pushing the button (Saskia & korenstra, 2015).

Strengths Gives direct feedback, gives information(distance)

Opportunities Nuances in tactile vibration, spatial awareness(distance), information creates security

Weakness: Static, does not give a sense of direction, might not be comfortable- might not be suitable for an infant and is a one-way communication (Linear model of communication).

Picture 4. The heartbeat device.

Source:https://nkcdb.se/overgivenheten-minskar-med-enkel-apparat/

Figure 5. Results from the existing practices analysis done at the start of the development phase, 5.3.1.

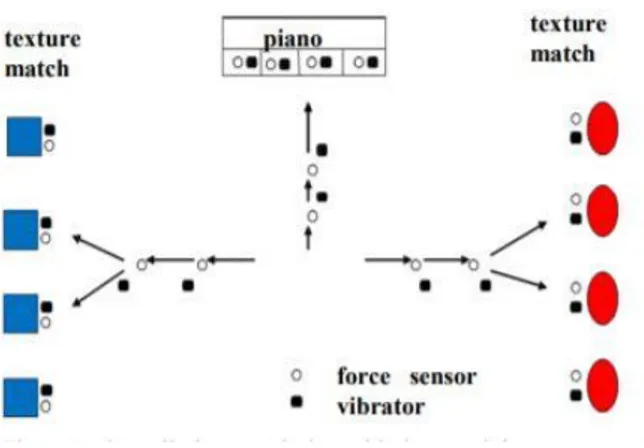

3.3.2.2. An Interactive Play Mat for Deaf-blind Infants

O’Bryan, Parvez and Pawluk focused on creating a toy for infants with Deafblindness to support their exploration of the world since there were so few devices designed for them (O’Bryan et al., 2012). The interactive play mat introduces three activity areas, one for remembering and repeating vibrations and two areas for matching textures. The mat consists of pressure sensors that measure the direction of the infant's movement, which turns the vibrators on further along in the direction the infant is moving, in order to encourage

exploration. At the time of publication of the research paper, they had not done testing of the interactive mat but were intending to at the Virginia Project for Children and Young Adults with Deaf-Blindness. Before finalizing the design, a few final modifications was expected. (O’Bryan et al., 2012).

Strengths Gives direct feedback, Tactile vibrations, invites for movements, provides infant autonomy in learning and exploring

Opportunities Provides autonomy to the infant and caregiver and

stimulates tactile memory and movement by using pressure sensors to locate movements

Weakness: Static, excludes caregivers’ participation (no chance to connect), no communication

Figure 6. Illustration of the three areas.

Source: O’Bryan, Parvez, and Pawluk ,2012. An interactive Play Mat For Deaf-Blind Infants. 240https://doi.org/10.1145/2384916.2384972

Figure 7. Results from the existing practices analysis done at the start of the development phase, 5.3.1.

3.3.2.3. Resonance board

The resonance board is a hollow wooden platform where the infant can play and explore with its whole body, either alone or together with a caregiver. It is designed by Dr. Lilli Nielsen a psychologist focusing on educating blind children through an approach called Active

Learning1. The concept with the platform is that the infants can perceive sound in the form of vibrations, allowing for direct feedback from an action taken. The action can be that the caregiver or infant is playing with toys or other objects on the platform, playing with instruments or tapping the board itself. It is up to the caregiver’s imagination what to introduce to the infant. The feedback from the platform aids the development of spatial awareness, auditory awareness and to become an active learner (Washington Sensory Disabilities Services , 2020).

1 Active Learning is an approach that promotes the development of individuals with disabilities and is based on Dr. Lilli Nielsen’s work (Active Learving Space, 2020).

Strengths Direct, Fluent, gives feedback, provides autonomy in learning and exploring, Individualized, Supports communication.

Opportunities Infants and caregiver can develop an interpersonal

communication that they both can connect to and can also lead to developing a turn-taking structure.

Weakness: Caregivers must physically be present to interact and communicate.

Figure 9. Results from the existing practices analysis done at the start of the development phase, 5.3.1.

Figure 8. Snapshot from an informational video about the Resonance board. A deafblind girl interacts with the toys on the resonance board, listening to feedback from her actions.

4. METHODS

In this project, human-centered design methods have emanated accordingly to the structures of the four phases in a Double diamond process. The four phases in a double diamond is structured to explore widely and open up in phases 1 and 3 and to focus and narrow down in phase 2 and 4 (Design Council, 2020). The process helped me to understand the individual and the situation and in addition to that, it pushed this design project forward by finding focus points.

In human-centered design, it is important to include the human throughout the project. But due to the circumstances of the CoVid-19 pandemic, I have chosen not to physically include the target groups as it has a risk of breaking one of Gelling’s seven principles of ethical healthcare research, which is that there is a risk of causing harm to the participant (Gelling, 1999). That means that testing of the prototype has not been with the target groups but instead with participants with both hearing and sight. I am aware that we cannot assume that the experience is the same for an infant with Deafblindness as to an individual who has both hearing and sight, but their experiences can guide this design project to a certain extend. In addition to that, the functionality and feasibility of the concept has been discussed with Kirsten Rassmus-Gröhn from Certec and Linda Eriksson from the NKCDB, presented in 5.4.2.

In this section, a brief description of each phase is presented followed by a description of the methods and the reasoning why the methods were chosen for this design project.

4.1.

Project Plan

Figure 10. Illustration of what methods were used in which phase of the Double diamond process in this project.

4.2.

Discover phase

In this phase methods that help to understand the individual and the situation are important to use so as to not base anything on assumptions. These methods include Ethnographic research where one talks or spends time with the target group, but due to the current situation of the CoVid-19 pandemic, I did not make any firsthand observations on how Infants with Deafblindness and caregivers interact or communicate with each other. Instead, I made secondhand observations by using netnographic research methods, such as reading and following blogs of caregivers with infants born with Deafblindness and listening to podcasts of interviews and personal stories of people born with Deafblindness. I chose not participate in the comment section of the blogs that I was following because I found the conversations between caregivers to children with Deafblindness and the content of the blogs to have “thick descriptions” (Geertz, 1973).

Ethnographic research online is not based on a word search but needs to have a grounding in what you are looking for, a research purpose. E.g. linguists look at the language in forums or social media platforms and sociologists look at interactions or habits (Kozinets, 2010). Netnographic data collection includes a variety of data including, images, conversations, video and interviews conducted via email or Zoom (Kozinets, 2016).

In this project, the purpose of using Netnography was to understand lived experiences from caregivers to Infants with Deafblindness and from people with Deafblindness. During the discovery phase, netnographic research methods assisted this project to find the design challenge, to explore the design situation and to investigate what practices exist today, presented in 3.3 as existing practices.

Since this project deals with individuals classified as vulnerable, I needed to ensure that the design project would be ethically sound. Therefore, research within ethics was conducted which led to the decision to strive to adhere to Gelling’s seven principles of ethical healthcare research (Gelling, 1999).

In accordance to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), data collection has been stored on my personal computer at home, which only I can access. The individuals who have participated in this design project have signed a consent form, appendix 1, and the experts have given verbal and written consent via email to use insights gathered from the interviews. Other collected data through netnographic research, are publicly archived data and I have therefore not asked for consent to use it as a source of second hand information in fieldwork, because it is public domain.

4.3.

Definition phase

During this phase, it is important to choose methods that help you synthesize (Design Council, 2020) by finding patterns and forging connections so that the design challenge can be identified (Kolko, 2010). Once identified, I conducted structured expert interviews and semi-structured expert interviews, presented in 5.2.1, in order to get inspiration and information about specific topics. The specific topics were about remote non-verbal communication and existing communication devices. This helped me to gain an in-depth understanding of the target groups, get technical information about existing assistive devices, one of which was Heartbeat, presented in 3.3.1.1, and to confirm insights from the theoretical

part, which would fuel the design process ahead. Methods to synthesize in this phase included insights mapping, Point of view, Scenario building and to reframe the design challenge, I used the method; How Might We (Interaction Design Foundation, 2018).

4.4.

Development phase

In this phase, I used methods that support ideation in order to explore different answers to the defined design challenge (Design Council, 2020). At the start of the development phase, I went back to look at the existing practices I found during the discovery phase. At this point, I had a clearer direction and focus of the project and therefore did an analysis of the existing practices that are for individuals without linguistic skills. Furthermore, I used methods such as Brainstorming and Sketching simultaneously, as the two methods worked together and helped me to visualize ideas that would support the fluency in a remote non-verbal

communication. After having some initial ideas, I prioritized and forged ideas to create a final sketch. I used the method of embodied sketching to generate experiential qualities to

sketching.

4.5.

Delivery phase

In this phase, I tested the Houde & Hill Look & Feel prototype in order to improve or exclude design choices (Design Council, 2020). The prototype was tested by two 18 month old

children, one 8 year old child and discussed with Kirsten Rassmus-Gröhn from Certec and Linda Eriksson from the NKCDB.

5. DESIGN PROCESS

In this section, a detailed description of how the methods presented in section 4 were applied, what results they gave, my analysis of them and how they inspired for further development. The result being a final concept of an assistive communication device, presented in section 6.

5.1.

Discovery phase

In this phase, literature and netnographic research assisted to explore, inspire and get an understanding of the design space in order to “emanate from the individual’s perspective and situation” (Certec, 2015, paragrapgh 3)

5.1.1. Literature and netnographic research

The theoretical background presented in section 3 is gleaned from literature -and netnographic research conducted during this phase.

Literature research gave me a solid basic understanding of the field. By listening to podcast interviews and by reading blogs of caregivers to Infants with Deafblindness, I could validate quantitative insights gathered from literature research with qualitative insights from

individual stories and experiences from people with Deafblindness and caregivers to infants born with Deafblindness.

5.1.1.1. Results and Implications

To obtain good interaction with an infant, the infant needs to feel comfortable and the interaction cannot be experienced as intrusive or sudden. Head and hands can be experienced as intrusive, while shoulders, back and arms are often experienced as less intrusive (NKCDB, 2019).

In order to make the infant feel understood, it is important to respond to the infant’s attempt of communication. The qualities of feedback and turn-taking are important for this to

happen (NKCDB, 2019; West & Turner, 2009).

To be able to develop an interpersonal communication the quality of fluency is what allows a conversation to be unpredictable (Barth-Weingarten et al.; NKCDB, 2019).

The interplay of prosodic features supports infants with intact hearing and caregivers to develop interpersonal communication, which later develops into a language. Prosodic

features in a voice is the pitch, loudness, tempo and rhythm (Barth-Weingarten et al., 2010).

5.2.

Definition phase

At the start of this phase, I used Interviews to get an in-depth understanding about remote non-verbal communication followed by using methods to help synthesize the insights in order to define the design challenge (Kolko, 2010).

5.2.1. Semi-structured and Structured Interviews (appendix 2, 3 & 4)

In order to fuel the design process ahead, this design project used Interviews to investigate the specific topics of remote non-verbal communication and existing assistive devices under the umbrella topic of child development. When conducting a Semi-structured Interview, a set of topics and questions are prepared to both have direction and flexibility in the interview (Interaction Design Foundation, 2020). I conducted two Semi-structured and one structured interview.

The first Semi-structured expert interview was with Karin Jönsson who is a technician and pedagogue at the NKCDB and Horistont. With expertise in computer adaptation and

computer aids for the visually impaired, she focuses on the educational part of it. The topic of this interview was on existing assistive devices and pedagogics.

The second Semi-structured expert interview was with Monika Estenberger, who has a background in pedagogy and psychology. She is working with courses and education at the NKCDB and is an experienced supervisor for staff working with individuals born with Deafblindness. The topics of this interview was on the development, needs and values for infants with Deafblindness and their caregivers.

The third interview was a structured interview because I wanted to get answers to specific questions via email. The structured interview was with Linda Eriksson, who is a pedagogue at the NKCDB. The interview topic was on how spatial location is perceived and experienced by

children with Deafblindness. In addition to that, Linda could also share personal experiences as she has had visual impairment since she was 4 years old and hearing loss since she was 6 years old. In section 5.4.2, Linda also commented the functionality and feasibility of the final design presented in section 6.

5.2.1.1. Results and implications

Both Karin Jönsson and Monika Estenberger highlighted the fact that there is an absence of assistive communication devices for infants with Deafblindness and that this group of people should have the same amount of participation in technology as the rest of the world does. They also highlighted that it is important that the devise does not become a substitute to social interaction but should instead complement it (appendix 2 & 3). Finally they brought up

imitation, explaining that it happens naturally in the early interactions, whether with

Deafblindness or not.

“Alexandra: When speaking to Karin, she also mentioned that imitation is important. Monika: Yes, that is often in the early interactions and happens naturally to children in general who aren’t deafblind as well, turn-taking which later is the foundations for further communication is also regarded as imitation (appendix 3, paragrapgh 7).”

Linda Eriksson highlighted the fact that it is important to get confirmation

and that all oursenses constantly interact with each other (appendix 4).

5.2.2. Insight mapping (appendix 5)

To find patterns and forge connections from literature research and Netnography, I used a method called insight mapping. This is used to” review and analyze all the information to

identify key themes and opportunities” (Eikhaug, Gheereawo, Plumbe, Stören Berg, & Merih,

2010, p.47). This method helped me understand and define the individual’s situation and needs.

5.2.2.1. Results and implications

Through insight mapping, I defined the following needs:

For the infants: - Autonomy in learning and exploring - The sense of a safe presence

Caregiver: - Security, safety and support for their infant - To not feel helpless

For both infant and caregiver: - Participation

- Develop a form of remote communication that both can connect to and develop fluently.

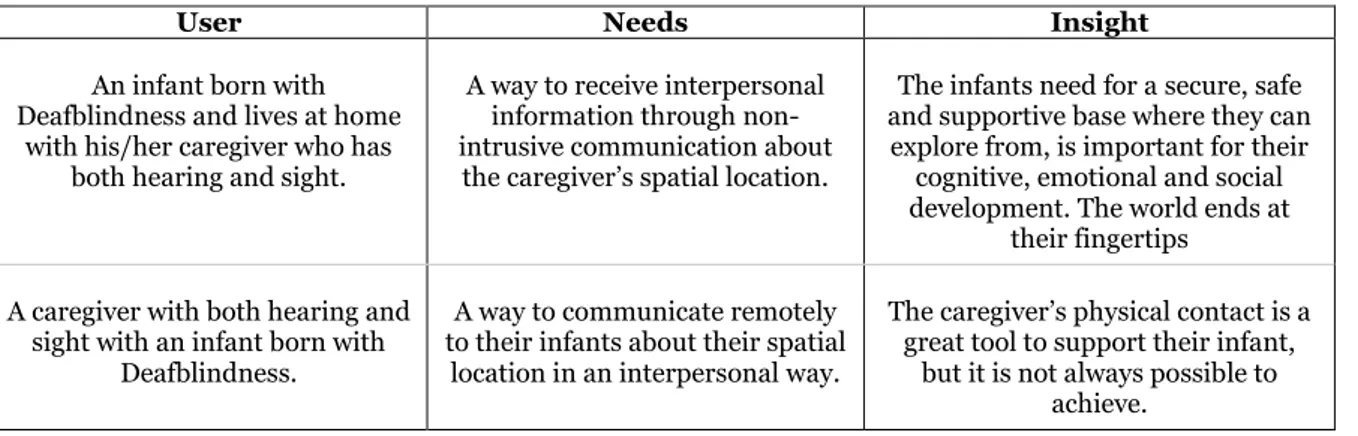

5.2.3. Point of view

After defining the individual and their needs through insight mapping, I needed to find the focus of the design challenge. To do so, the information extracted from Insight mapping (appendix 5), were divided into a user, needs and insight headings. This method is good to frame the problem, create a more narrow focus and to guide innovative efforts through the rest of the design process (Interaction Design Foundation, 2018).

5.2.3.1. Results and implications

Infants born with Deafblindness, need to receive interpersonal information in a non-intrusive form of communication about their caregivers spatial location because it fosters a secure, safe and supportive base from where they can later explore from, which is important to their cognitive, emotional and social development.

Caregivers to infants born with Deafblindness need to find a way to communicate remotely about their spatial location in an interpersonal way because physical contact with the infant is not always possible to achieve.

5.2.4. Scenario building

Through personas, role-playing or in this case, visual storytelling, scenario building can keep insights focused and to ensure that the needs are what is driving the design process (Eikhaug et al., 2010). In this design project, it was important to understand the experience lived by the infant and caregiver when not having physical contact and therefore the method of visual

storytelling was used. Buxton describes that Visual storytelling allows for “ capturing time, dynamics, phrasing- the temporal things that lie at the heart of experience” (Buxton, 2007,

p.279). An infant with hearing can communicate remotely through sound and create interpersonal communication through prosodic features fluently. The caregiver by their presence can acknowledge, interpret, give feedback, and ensure that he/she has understood the infants, this also done through prosodic features. This can create reinsurance in moments when the infant with hearing is feeling stressed or anxious. The visual storytelling is based on a sequence from the documentary Babies (Babies, 2020).

User Needs Insight

An infant born with Deafblindness and lives at home

with his/her caregiver who has both hearing and sight.

A way to receive interpersonal information through non-intrusive communication about

the caregiver’s spatial location.

The infants need for a secure, safe and supportive base where they can explore from, is important for their

cognitive, emotional and social development. The world ends at

their fingertips A caregiver with both hearing and

sight with an infant born with Deafblindness.

A way to communicate remotely to their infants about their spatial

location in an interpersonal way.

The caregiver’s physical contact is a great tool to support their infant,

but it is not always possible to achieve.

5.2.4.1. Results and implications

Visual storytelling of a situation between a caregiver and an infant with intact hearing from the documentary “Babies”.

1.

The 3-week old infant Willow is sitting in his baby seat in the back of the car. He has the company of his sibling who is sitting next to him, who has not developed linguistic skills either. In the front seats are his mother and father. Willow starts to cry, and mom interprets the cry as a hunger cry.

2.

The mother tries to comfort Willow by responding in a comforting, calm and slow tempo sentence; “I’m sorry, Willow. We’re nearly home.”

3.

The family comes home, and the mother sits down to breastfeed Willow. Adam, her husband films them sitting in the living room and whispers to the camera: Stressful for mummy.

Figure 12. Visual storytelling of a situation in a car where an infant with hearing and caregivers try to interpret and remotely communicate with each

other. A graphic composition. Source: Documentary Babies.

Visual storytelling of the same situation but evolving a caregiver and infant with Deafblindness.

1.

The 3-week old infant Willow is sitting in his baby seat in the back of the car. Next to him is his sibling but Willow does not know that, as far as he knows, he is alone. In the front seats are his mother and father, but Willow does not know that either. Willow starts to cry, and mom cannot interpret the cry since a form of communication has not yet been established due to inexperience in non-verbal communication. 2.

Mom decides to reach for Willow to ensure him of her presence and to try and calm him down. This is done by physical contact and the only place she can reach is his head. As Willow was not aware of the approach from his mother and since touching of the head can be experienced as intrusive, the comfort from his mother is experienced as sudden and intrusive behavior, causing Willow to feel fear. 3.

The family comes home, and the mother sits down to see if Willow is hungry by trying to breastfeed him. It turns out Willow is hungry. Adam, her husband films them sitting in the living room and asks the mother how she feels and how it is going because finally it looks like the mother does not feel helpless.

Figure 13. Visual storytelling of a situation in a car where an infant born with Deafblind and caregivers try to interpret and remotely communicate with

each other. A graphic composition. Source: Documentary Babies.

Through the visual storytelling,the following insights were made. The device should support feedback haptically. This could assure the infants that someone is there for him, which could calm the infant down and the mother wouldn’t feel so helpless in that situation. A device that is mobile would be an advantage, e.g. in the car or in the carseat. It should be able to inform the infant where the caregiver is approaching from, so that the infants is prepared for the caregivers touch.

5.2.5. HMW- How Might We questions

How Might We questions are used after defining the design challenge in order to open up for ideation methods in the next phase, the development phase. The goal of this method is to reframe insights to HMW questions that are focused enough to give direction but broad enough to suggest multiple solutions (IDEO, 2015).

5.2.5.1. Results and implications

At this point of the design process, HMW questions helped me reframed my problem

definition from: How can information about the caregiver’s spatial location be communicated to their infant with Deafblindness, to: How might we create a device that allows for

remote interpersonal communication by adding a physical dimension to it? This led to my final problem definition: What qualities could a device that supports remote interpersonal

non-verbal communication for an infant with Deafblindness have?

5.3.

Development

phase

In this section a reflection of existing practices and methods that support ideation in order to explore different answers to the defined design challenge are presented, followed by results and implications of said methods.

5.3.1. Existing practices analysis

The strengths, opportunities and weaknesses analyses presented in 3.3.1. were created during this phase in order to inspire ideation sessions.

The wearable Mobile glove Lorm got positive feedback because of it being lightweight and having a textile interface device. The benefits of a wearable being lightweight are great, as heavy or stiff wearables limits mobility and can be constraining to use. Because of today's sensors and actuators being so small, the possibilities for creating lightweight wearables like the mobile glove Lorm and DB-hand are greater. These academic research projects focus on helping people with deafblindness who already have a language, verbal or non-verbal, to communicate in order to enhance their independence. Assistive devices that support Deafblind communication for infants without linguistic skills are not as many but two examples that exist are Heartbeat and An Interactive Playmat for Deaf-blind Infants. As far as Caporusso’s finding during user testing of the DB-hand; that the system owe to be adaptive to keep pace with the user’s ability to learn in order to increase/achieve fluency. Unfortunately, technical devices like the Mobile Lorm Glove and the DB-hand, where a software system translates communication, the conversation can become static because

in translation. Heartbeat and An Interactive Playmat for Deaf-blind Infants are also static as it is the same in-and output for every person interacting with the devices.

Interpersonal communication is important to sustain because it helps us to establish safe relationships with each other and is foundational between infants with Deafblindness and caregivers in order to establish a form of communication (Barth-Weingarten, et al., 2010; M.Estenberger, personal communication, April 24th, 2020).

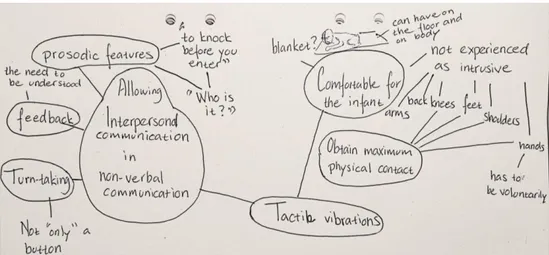

5.3.2. Brainstorming and Sketching

Two of Osborn’s rules of brainstorming encourage people to “withhold judgement and build on ideas of others” (Gerber, 2009, p.97). The method brainstorming is a great method for design teams to develop ideas that can build on each other’s, and in this project, it inspired me as an individual designer to express ideas fluidly. This method was used simultaneously with sketching because both methods are inspired from the field defined as inexpensive

ideas.

Inexpensive ideas means that it should not cost time or effort to produce. The term comes from Bill Buxton’s book: Sketching user Experiences; getting the design right and the right

design. Other attributes that applied to this design project in the development phase were for

the sketches to be quick, timely, disposable, plentiful, ambiguous and lastly suggest and

explore rather than confirm (Buxton, 2007, p.111-113). 5.3.2.1. Results and implications

Brainstorming led me to question and explore how the turn-taking structure of feedback could give nuances to support interpersonal communication. At this point, I knew it was important to give feedback but not in the form if “only” a button, like the device Heartbeat. Brainstorming and sketching supported an ideation session where the idea of transferring prosodic features as an input to vibrations as an output.

By using brainstorming while sketching I connected the results and implications from the methods used up to this point, which in turn resulted in qualities that could support remote interpersonal non-verbal communication. Through these qualities, I could create design criteria for a concept of an assistive communication device.

Figure 14. Picture of a brainstorm that connects implications from methods presented throughout section 5.

Design criteria for an assistive communication device that could support remote

interpersonal non-verbal communication should be as Direct as verbal communication, in order to put the infant and caregiver in the same timeframe. As seen in the analysis in 3.3.1.3 the resonance board is a good example of being Direct. If communication is delayed, it could leave the infant or caregiver wondering if the information has been delivered or perceived. By supporting Turn-taking, a framework for communication is created in order to know who the receiver and sender of information is (M.Estenberger, personal communication, April 24th,2020; NKCDB, 2019). Through Turn-taking, Feedback is supported, which is important in order to confirm that the information has been received or that the individual has been understood (M. Estenberger, personal communication, April 24th, 2020; NKCDB, 2019; West & Turner, 2009).

As seen in the visual storytelling in 5.2.4, a device that gives Spatial Information could comfort the infant by informing that the caregiver is in the immediate environment without having physical contact.

Since each infant and relationship has its own way of communicating and is being developed by and between two or more individuals fluently (M.Estenberger, personal communication, April 24th, 2020; NKCDB, 2019), an assistive communication device should support the

Fluency of a conversation. By doing so, a chance to develop interpersonal communication is

created. The qualities of pitch, loudness, tempo and rhythm in a person’s prosody is

Individual and can be used to establish interpersonal communication (Barth-Weingarten et

al. 2010). Through that, a negotiation in order to find a common understanding of what the individual prosody and behavior mean is possible (Barth-Weingarten et al., 2010;

M.Estenberger, personal communication, April 24th, 2020; K.Jönsson, personal communication, April 22nd, 2020).

Through sketching, inexpensive and plentiful ideas based on the design criteria and inspired by the strengths and opportunities of the resonance board in 3.3.2.3, concept one was created.

Concept one consists of a square mattress with Micro Vibrator Motors (MVM) placed on all four sides which give spatial information by changing the location of the vibrations

accordingly to where the” buzzer” (the caregiver) is located, e.g. if the “buzzer” is to the right of the mattress, then the right-side of the mattress vibrates. The concept supports

turn-taking and feedback. Communication is based upon taps from the infant and it can achieve a

certain degree of fluency, but it cannot support other bodily behaviors as a form of communication from the infant to the caregiver.

Figure 15. Picture of sketch of concept 1.

1. The infant taps on the mattress. 2. Caregiver has a mobile buzzer that buzzes the same amount of taps that the infant did on the mattress, in the form of vibrating signals. 3. The caregiver taps back (in vibrating form) the same amount, imitating the infant. 4. The infant feels the taps in the form of vibrations in the mattress and from

From concept one, concept two was produced, which is based on the idea of using prosodic features of the caregiver’s voice as an input to be transfer as vibrations to a blanket that the infant is lying on. The features of rhythm and tempo in a voice prosody were chosen as an input because the idea of loudness (stronger vibrations) could convey the distance of the caregiver, inspired by Heartbeat in 3.3.2.1 I did not choose to use the prosodic feature of pitch, as I was unsure if an MVM could convey pitch.

Figure 16. Picture of sketch of concept 2.

The infant lies on a blanket on the floor and moves. The caregiver is in the kitchen and can see or hear that the infant moves. The caregiver says: Hey, hey, I’m here! The prosodic features of rhythm and tempo in the voice is directly transferred to the MVM that is closest to the source of the voice. The infant gets information of where the

5.3.3. Embodied sketching

Like sketching, embodied sketching, is a method used in the early design phase but also includes the experience (Márquez Segura, Vidal, & Ros, 2016). Márquez Segura et al. describe the qualities of embodied sketching to support ideation, include bodily experience and spur creativity (2016, p. 6016). This method helped me explore possibilities and restrictions in design concepts by exploring how we experience vibrotactile stimulations by using different materials. When investigating possible design opportunities that allow for remote

interpersonal communication by adding vibrotactile stimulation, one cannot assume that the perceived experience a person with hearing and sight has, are the same as lived experiences of an infant born with Deafblindness. In this project, embodied sketching was used to explore novel technical possibilities. Embodied sketching evolved to testing and prototyping as each testing gave new insights, which led to a Look & Feel prototype.

5.3.3.1. Results and implications

Through embodied sketching and testing, I investigated if vibrations could be used to give directions of the caregiver’s spatial location and if the intensity of the vibrations could be felt in order to inform the distance of the caregiver.

MVMs were placed in each corner of the wooden frame of a canvas and controlled by a potentiometer each. The aim of the testing was to answer the following questions:

1. Can the user feel where the vibrations come from by holding their hand on the middle of the canvas?

2. Can the user differentiate the intensity of the tactile vibrations?

The first testing resulted in that the participant could not find where the vibrations came from since the wooden frame transferred and amplified the vibrations to the opposite side from where the MVM was placed. The intensity could be differentiated but on the opposite side.

Left to right. Figure 18a) Backside of the canvas with an MVM in each corner. 18b) Participant uses hand to search after the vibration origin. 18c) Participant stops at the opposite side of the vibrating MVM.

In the second testing, the MVMs were placed on the canvas instead of on the wooden frame as in test 1. This resulted in that the participant moved his hand directly to the origin of the vibration and the intensity of vibrations were easier to differentiate.

In the third testing, the same aim and questions as in test 1 and 2 were applied. The

experiential quality of test 2 was applied to the concept of the blanket presented in concept 2. To emulate the sensation of a blanket that transfers vibrations in the same way as in test 2 glass marbles were sawn into a pillowcase with an MVM placed in each corner, separately controlled by potentiometers.

This resulted in that the participant did not move his hand to the vibration point but instead could tell directly what direction the vibrations came from. The vibrations became weaker the further away the participant held his hand from the activated MVM, and he could also feel the change of intensity of the vibrations.

In test four, the same aim and questions as in test 1, 2 and 3 were applied but this time using an Adin vibration speaker on the glass marble pillowcase.

This resulted in that the participant could feel the vibrotactile stimulations from the prosodic features of a voice. This opens up for the possibility to use vibration speakers to transfer the prosodic features of rhythm and tempo in a voice directly and fluently into vibrations instead

Left to right. Figure 19a) Backside of the canvas with an MVM in on the canvas. 19b) Participant uses hand to search after the vibration origin. 19c) Participant stops at on the vibrating MVM.

Left to right. Figure 20a) The inside of the pillowcase, glass marbles and an MVM sawn in. 20b) Participant uses hand to feel the vibration origin.

5.4.

Delivery phase

In this section, testing of a Look & Feel prototype is presented with the aim of evaluating functionality and feasibility of the blanket concept. In addition to that, suggestions for future improvements are presented as a result from a discussion I had with Kirsten Rassmus-Gröhn from Certec and Linda Eriksson from NKCDB.

5.4.1. Prototyping and testing

Houde and Hill explains that a prototype is a representation of a design idea and can have different purposes depending of what the goal is to communicate (Houde & Hill, 1997). A role prototype’s goal is to communicate the concepts functionality in the user’s situation, the Look & Feel prototype’s goal is to transmit haptic and visual experiences, while the

implementation prototype’s demonstrates the technical feasibility.

5.4.1.1. Results and implications

In this project a Look & Feel prototype was created in order to test and evaluate children’s reactions and experience to vibration. By doing so, new insights were made which resulted in suggestions for improvements of the Look & Feel prototype and a final design concept, presented in 6.2.1 as a Role prototype.

The Look & Feel prototype was an improvement of test 3, which was an emulation of a blanket that transfers vibrations in the same way as in test 2. More glass marbles were sawn into the pillowcase to make the blanket bigger but because the fabric did not stretch, the blanket took a different shape than what was intended. Instead of the blanket being square, the blanket took an irregular shape. Despite that, I continued the testing by placing an MVM in each corner marked red, separately controlled by potentiometers, to see if the origin of the vibrations still could be felt. The pillowcase was covered with a colorful textile to draw

attention and the electronics were covered by cardboard so that it would not draw the children’s attention. Each corner where an MVM was placed, an image of an animal was placed for the children to easier describe where the vibrations originated from.

The first test was conducted with two 18-month-old children who have hearing, sight and basic linguistic knowledge. It resulted in that the images of the animals caught the two childrens attention more than the vibrations. When the toy lion was placed on the vibrator, seen in picture 9, the children petted him for a few seconds and then something els in the room caught their attention. The children did not seem to care too much of the vibrations. The vibrations did not seem to be experienced as scary, intrusive or sudden but nor did it excite them. They did not try to locate where the vibrations came from but seemed to accept its presence.

The second test of the Look & Feel prototype was conducted with an eight year old child who has hearing, sight and fully developed lingustic skills. The aim was to see how the child reacts to vibrations and if the vibrations can be located by using hands and by sitting on it.

By using the hands, the child could locate what animal was vibrating. By sitting on the blanket, the child responded quickly and hesitentfree when it vibrated under the thighs but hestitated and sometime gave the wrong answer when the back vibrated, the one under the bum. Believing that it sometime was the vibrator closest, under the thigh.

Figure 22: A picture from the testing, the children were more interested in their toys on and the visuals next to the

blanket than in the vibrations of the blanket.

Left to right: Figure 21a) Arduino Uno connected to three MVMs, placed in the corners marked red and controlled separately by a potentiometer. 21b) Wires and fragile technology

It seemed like it was harder to locate where the vibrations came from when the vibrator was coming from underneath the bum. It could be that we have more fat on that part of the body or that the vibrations are spreading too wide, making it hard to distinguish the vibrations origin.

5.4.2. A converstaion with the experts

At the end of the delivery phase, I chose to contact Kirsten Rassmus-Gröhn from Certec to discuss the functionality and feasibility of the final concept by presenting the Look & Feel prototype and Linda Eriksson from the NKCDB in order to discuss the functionality and feasibility of the final concept by presenting the Role prototype.

5.4.2.1. Results and implications

From the discussion with Kirsten Rassmus-Gröhn about the Look & Feel prototype, it was acknowledged that it was not enough to use one hand in order to feel where the vibrations came from. As an individual with hearing, the sound of the vibrations might have affected the results. The vibrations spread far; this is not negative nor positive. That means that there are possibilities to take advantage of it. Sound propagation absorbent could limit the vibrations from spreading, which could inform where the vibrations came from in a much precise way. When discussing the Role prototype with Linda Eriksson the importance of it being clear where the vibrations come from was highlighted. If the caregiver is the one with the

microphone (in the mobile), then the infants would only get information from that caregiver and no other individuals in the immediate environment. Sometimes limitations are good but sometimes more possibilities to connect to others is good to have as well.

Figure 23: Eight-year-old child sits on the blanket trying to feel where the vibrations come from.

Suggestion for future improvements would be to have sound propagation absorbent in-between the MVMs to make the origin of the vibrations clearer.

The concept of having multiple caregivers connect to the blanket simontaniously originated from the discussion with Linda Eriksson.

Figure 25: Visual storyline of caregivers sharing their location (direction) by clear vibrations using sound propagation absorbent between each MVM (marked red). In the first frame the

mother connects to the blanket by using the microphone in her mobile phone. In the second frame the dad connects to the blanket as well. The infant understands who they are by what

they say and where they are by clear directions of the vibrations.

Left to right: figure 24a) An illustration of how the vibrations spread through the glass marbles in the Look & Feel prototype. 24b) How sound propagation absorbent could limit the sound

6. MAIN RESULTS AND FINAL DESIGN

In this section, the main results are presented to answer the two sub-questions and the problem definition. A final design concept of a device that could support remote

interpersonal non-verbal communication for an infant with Deafblindness, is presented as a Role prototype.

6.1.

Main results

In order to answer the problem definition: What qualities could a device that supports

remote interpersonal non-verbal communication for infants with Deafblindness have, this

design project investigated two sub-questions: How can the device instill a sense of security,

safety and support? and: How can an infant with Deafblindness sense communication? 6.1.1. What qualities could a device that supports remote interpersonal non-verbal

communication for infants with Deafblindness have?

The methods in this design process resulted in different qualities that lead to the concept of the assistive communication blanket. Following qualities were defined: Insight mapping in 5.2.2, resulted in the quality of fluency in a conversation, visual storytelling in 5.2.4, resulted in the qualities of feedback and spatial information and the methods of brainstorming and sketching in 5.3.2, resulted in the qualities of direct, individual and turn-taking.

The qualities of a device that could support remote interpersonal non-verbal communication for an infant with Deafblindness found in this project are:

Direct, a direct result of an action you take.

Based on Turn-taking, to create a framework for communication. Supporting Feedback, to create a feeling of being understood

Spatially informative, one can get an understanding of where the origin of a voice is/

coming from, e.g. is the person behind me? In that case how far?

Fluency, a conversation is unpredictable, therefore fluency is needed in order to support

interpersonal communication where participants negotiate a common understanding. Individual, prosodic features of a voice can give us other information than what the

word means.

6.1.2. How can the device instill a sense of security, safety and support?

The value of safety is created when the caregiver has physical contact with the infant because the infant then has access to information (K.Jönsson, personal communication, April 22nd, 2020; NKCDB, 2019). Since the caregiver cannot always maintain physical contact, a physical object that gives tangible support should support the infant’s access to that information. How this design project supports the access of information is by using qualities of communication. Therefore the value of safety is created by supporting remote communication through a physical device that can communicate direct information fluently and haptically.

The value of security is created by supporting interpersonal communication in a

non-intrusive and non-sudden way (K.Jönsson, personal communication, April 22nd, 2020; NVC, 2020; Withrow, u.d.)By using the qualities of rhythm and tempo in prosodic features as an input, the output in the blanket is the form of vibrations imitates the rhythm and tempo of the caregiver’s voice. This enhances the conversation to be fluent, which supports the infant and the caregiver negotiation and development of an interpersonal communication (Barth-Weingarten et al., 2010).

The value of support is created by using the qualities of turn-taking and feedback from the interactional model of communication. The qualities support the infant by making him feel understood and that someone is there for him (Chen & Haney, 1995; NKCDB, 2019).

What Why How

Safety To have access to information Communication

Security To know who and where

someone is, in a familiar way Vibrations reacting to individual prosodic features and informing of spatial location,

Supportive To know that someone is

there for you. Turn-taking and Feedback

6.1.3. How can an infant with Deafblindness sense communication?

Communication is the process of forwarding verbal or non-verb information and cannot be developed in solitude but needs to have two or more active participants (Cambridge

dictionary, 2020; NKCDB, 2019). Communication is in all behavior (Watzlawick et al., 2011), behavior as in that we behave in a certain way to achieve a certain feedback (Hinde, 1972). How we sense communication, is by getting feedback (NKCDB, 2019; West & Turner, 2009). In this design project feedback needs to be haptic in order to ensure that information has been received.

6.2.

Final design concept

The final design concept is a blanket that can connect to the microphone of a mobile phone. The mobile phone provides the blanket with the caregiver’s location (direction and distance) and transfers speech into vibrations.

The concept was created by the design criteria presented in 5.3.2.1

Figure 26: What, Why, How chart of the values safety, security and support