Consumers rituals inside shopping

malls

A qualitative study on consumers shopping rituals inside Swedish shopping

malls

Antonio Tortorici

Pierre Alefjord

Stockholm Business School

Master’s Degree Thesis 30 HE credits Subject: Marketing

Program: Master's Programme in Marketing , 120 HE credits

Spring semester 2020 Supervisor: Jon Engström

Acknowledgements

We would like to offer our sincere gratitude to all those who have contributed in one way or another during the process of this thesis. Without these people, this thesis would not have been possible. We would especially like to thank the following people:

Jon Engström

Our supervisor who throughout this journey has assisted us with ideas and guidance that have been paramount to the quality of this research study.

Michael Cronholm

For putting us into contact with the interviewees of our pre study. His help and support in that initial phase of our study was of great value in shaping the scope of our study.

Mattias Celinder & Robert Felczak

The two mall managers were able to take time to be interviewed for our pre study. Their expertise and knowledge assisted us in reaching the scope of our study which laid the foundation of our work throughout this journey.

All interviewees

A special thanks to all 20 people who took their time to be interviewed for our study. Their insights and thoughts have been incredibly valuable and is what shaped the outcome of the study

Family and friends

Finally, a big thanks goes to all those people that helped us going through this thesis and supported us during this time.

Abstract

Beyond simple shopping needs, nowadays consumers are continuously looking for the consumption of new experiences. This contemporary consumer request also unveils inside shopping centers, which as scholars recognize, are shifting functionality towards becoming centers for customer engagement.

Following this trend, marketers are continuously looking into new ways to increase offer attractivity and consequently spur customer engagement. Rituals represent a possible new lens to study consumer behaviour inside the mall landscape and disclose new hidden consumers' processes for value creation.

By conducting a pre-study with two mall managers, we sensed their perspective of the mall and individuated the challenges of shopping centers future development and new consumer shopping trends. In a second phase, we focused on analysing the consumer perspective and utilization of the mall by observing their shopping rituals. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 consumers constituting of both Young Professionals and families.

In conclusion, different types of rituals were individualized and analysed. By applying rituals to the shopping behaviour of consumers inside shopping malls yielded several insights that resulted to be useful for managers and a valuable contribution to academic research. The results show that mall visitors consume specific rituals inside shopping malls depending on both the target groups (young professionals or families) of consumers as well as the mall experience type (seductive, functional, interactive museum or social). Young Professionals tended to be more spontaneous and socially oriented. However, families tended to shop for functional reasons and often have a planned script of their shopping ritual that they follow throughout their shopping journey at a shopping mall.

Keywords: Rituals, Consumer rituals, Shopping center, Malls, Experiential marketing, Value creation, Customer experience

Table of contents

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.2 Problematization ... 2

2. Literature review ... 4

2.1 The role of malls ... 4

2.2 Consumer behaviour ... 5

2.2.1 Service dominant logic ... 5

2.2.2 The mall experience types ... 6

2.2.3 The servicescape model ... 7

2.2.4 The expanded servicescape model ... 8

2.3 Rituals ... 9

2.3.1 Ritual Behavioural construct ... 10

2.3.2 Ritual structural elements ... 11

2.3.3 Value Creation in rituals ... 12

2.3.4 Rituals in shopping ... 13

3. Empirical setting & research design ... 15

3.1 Research design ... 15

3.2 Pre-study ... 16

3.2.1 Motivation ... 16

3.2.2 Pre-Study Design, Method and Process ... 16

3.3 Empirical setting ... 17

3.4 Data collection process ... 17

3.5 Data analysis method ... 18

3.6 Quality of research ... 19

4. Findings & analysis. ... 21

4.1 Pre-study findings... 21

4.1.1 Increased focus on the experience ... 21

4.1.2 Changed consumer behaviour ... 21

4.1.3 The importance of atmosphere ... 22

4.1.4 Summary of pre-study ... 22

4.2 Main study findings ... 23

4.2.1 Ritual artefacts ... 23

4.2.2 Rituals scripts ... 26

4.2.3 Ritual performance role ... 29

4.3 Summary ... 35

5. Discussion ... 37

5.1 Rituals ... 37

5.1.1 Adaptation of the ritual framework ... 37

5.2 Key insights on mall experience types... 38

5.3 New framework ... 38

6. Conclusion ... 40

6.1 Summary ... 40

6.2 Managerial implications ... 41

6.3 Limitations ... 42

6.4 Suggestions for future research ... 42

References ... 43

Appendices ... 50

1. Table 1. Interviews pre-study ... 50

2. Table 2. Interviews main study ... 50

1

1. Introduction

This section will start with a brief background of the study field. The next part will problematize the current studies in this field and how a gap emerged that current academia has failed to address. Lastly, the research questions of the study are presented.

1.1 Background

‘’The retail apocalypse is far from over” (Taylor, 2019). This statement was the topic of several

newspapers when recently numerous shopping centers shut down. Consumers’ practices have changed, and therefore malls had to adapt to a new digitalized world. Nowadays, going to the mall is yet a massive consumer trend but people go there for different purposes than their parents used to. In such a delicate moment, managers need to find new solutions to float on the surface of profitability.

The history of shopping malls is extensive; sixty years ago, the first indoor mall was built in Minnesota (Feinberg & Meoli, 1991). From 1956 until today, consumer malls' usage and social role have changed immensely. Ritzer (1999) coined the term ''Cathedral of

consumption'' to describe these places of massive hyper-consumption. This name was

attributed to malls, which nowadays hold the role of the cathedral not only as a symbol, but even as the focal point where the world of consumption originates (Vincenzo, 2018). The parallelism between the mall and the cathedral is not merely metaphorical but extends even on a physical level. For example, today, communities use the location of a mall as a reference point for orientation in the city landscape; malls are used as the meeting location of young, old, and families on a daily basis. Over more, both malls and churches claim explicitly and implicitly to be much more than a simple material building. Malls strive to represent not just a marketplace, but a more sacred place where consumerism pilgrims to go. This phenomenon can be observed by looking at the architecture through which the mall is designed and managed. The servicescape inside a mall is structured in a way that could resemble a sort of

''sacred city'' for consumerism and to escape reality and enter their world inside (Rosenbaum

& Massiah, 2011). Most of the decorative elements present inside malls are alike and tend to recreate meanings to the Eden, such as trees, fountains, the fragrance of freshly baked bread, and more (Zepp, 1997). Due to all these attributes, the shopping center is intended to appear as a peaceful and stress-free environment.

During the transformation of the mall through history, real estate developers understood the importance of the symbolism in the consumer behaviour field. For example, designers

2

recognized the value of a food court as an indispensable space where to consume the ceremonial meal with the family. Nowadays, consumers are looking for complex meanings into services and products so while shopping they are driven by the fulfilment of higher needs such as social acceptance. If taken into consideration the human and social components of the experience inside the mall, the huge value it produces for the community surrounding it must be recognized. People of all ages gather at the mall to have social interactions and conduct activities together.

Even if having great importance in our society, the mall concept is facing difficulties in surviving. Indeed, the retail industry is undergoing a massive paradigm shift due to the increase in popularity of e-commerce, which creates a challenge for physical retailers to stay relevant (Kim, 2002; Frishammar, Cenamor, Cavalli-Björkman, Hernell & Carlsson, 2018). Malls cannot compete with e-commerce platforms when it comes to price convenience and product selection, that is why they should switch the source of their competitive advantage to something that e-commerce cannot compete with, like experiences. (Fantoni, Hoefel and Mazzarolo, 2014). This shift is creating a struggle in managers' understanding of what and where the value of malls resides. Malls have historically been a place for consumers to go to in order to find clustered shopping stores in which everybody can find many product alternatives in the same area complemented by minor support facilities like cafés and restaurants. Today instead, shopping malls contain an increasing amount of experiences and services in their tenant mix, so that shopping centers are becoming a destination for experiences rather than places for shopping products.

1.2 Problematization

Many scholars and practitioners acknowledge the fact that there is a significant shift for shopping malls changing their tenant mix towards being more experience focused (Kim, Lee & Suh, 2015; Westfield, 2020). Despite this, little attention is given to studying the perception of malls from a consumer’s point of view, and the entire value creation process. From this condition arose the idea of trying to find a proper lens to investigate contemporary consumer habits inside shopping malls. A few scholars have identified rituals as an essential technique to understand and enhance the value creation process of consumers (Servadio, 2018); this has caused the production of several works in this domain. Rituals are consumer-centric processes which, if used properly can help marketers increase engagement and satisfaction. However, scarce studies have been conducted specifically on shopping rituals and not a singular one connected to the mall context to our knowledge.

A common misconception that we faced was that scholars tend to generalize shopping experience and overlook the critical contextual factors a shopping mall can provide (Gilboa, Vilnai‐Yavetz & Chebat, 2016). Another fallacy is to believe that value creation is a one-way stream from service provider to consumer. The truth is that it is a process in which both

3

parties contribute and co-create value. Thus, recent literature has mainly been focused on describing methods for managers to deliver perfect service to consumers. However, lacking in explaining the idiosyncratic consumer values (Servadio, 2018). Although a few scholars have attempted to provide alternatives to the provider perspective of service (Heinonen, Strandvik, Mickelsson, Edvardsson, Sundström & Andersson, 2010), comparatively lower attention has been given to understanding how value emerges from consumers’ angle. Value creation is not a one-flow process; it comprises a multi-layered and complex system of actions, roles, and objects (Tetreault & Kleine, 1990). From a theoretical point of view, it is defined as a set of interactions between the service provider and the receiver, which outputs are more valuable than inputs. The idea behind this research is to find and analyse the source of value through the consumer point of view, opening a new consumer behaviour perspective. Rituals, as Servadio (2018) mentioned, are consumer-centric processes that are happening inside the actor realm rather than on the outside. In this sense, rituals are practices in which managers have little control over and in which they have confined consciousness. A ritual point of view can help to understand the mechanics that bring consumers to value creation, which can be invisible to service providers; this approach can be an interesting theoretical lens for discovering new routes of the value creation process. Hence, the first research question of our study is:

1. How can rituals better understand consumer behaviour inside a shopping mall?

This study primarily investigated two target groups, young professionals, and families. Rituals of these groups are valuable to look at since they are two main target groups for malls. This thesis sought to establish a model for understanding and take benefit from consumer shopping rituals. Henceforth, the second research question of our study are formulated as:

2. How are rituals expressed among young professionals and families inside a shopping mall?

From an academic perspective, this thesis aims to bring new knowledge to the context of shopping malls and consumer behaviour as a field through answering our research questions. From a practitioner’s side, we aim to provide managers with insights that may be used as foundation for decision making and be a perspective to consider when structuring a shopping mall offering.

4

2. Literature review

This chapter provides the theoretical framework that will be used in this study. In part 1, the role of malls will be investigated. Part 2 delves into consumer behaviour and service, focusing on purpose as well as influential factors of the shopping context. Lastly, part 3 will address the subject of rituals and the implications it has on shopping. These areas will then constitute the lens that will be used as our framework in our study and will be applied to the researched phenomena, which will be presented in the forthcoming section.

2.1 The role of malls

The International Council of Shopping Centers (2020) defines a shopping center as “A group

of retail and other commercial establishments that is planned, developed, owned and managed as a single property, typically with on-site parking provided.” However, shopping malls

function stretches beyond that since it serves as a sanctuary for consumers to gather in activities that create value beyond the tangible and visible benefits of products (Fantoni, Hoefel & Mazzarolo, 2014). Malls came to existence in 1956 to provide a community with a centre for which people can indulge in shopping, socialize, and participate in cultural activities (Gruen & Smith, 1960). The focus of malls has historically centred around price and location, which were the two most fundamental factors until the 1970s, while concepts such as service, branding, and design gained focus a decade later (McGoldrick & Andre, 1997). The rise of the shopping centre’s popularity inevitably increased competition in the market. This change caused a managerial shift of focus, from the fulfilment of basic needs only (price and location) to a fulfilment of higher needs such as experiences, values, and social meaning (ibid). Shopping malls hold both the practical dimension of clustered retail stores but also the societal role of being a destination to socialize where experiences are co-created with other consumers (Matthews, Taylor, Percy-Smith & Limb, 2000).

A big trap many malls are caught in is that they take a conformist approach by mimicking major mall actors and put less focus on creating values that are discerning from the mass. A reactive approach to this change of malls offerings and tenant mix have led to many malls end up providing similar things and thus becoming more and more alike (Ibrahim & Ng, 2002). This conformist development is causing malls to be repetitive in their evolutionary process and tend to lack identity since there are no apparent idiosyncratic features for consumers to distinguish one mall from the other (Kim, Sullivan, Trotter & Forney, 2003). Managers influenced by utopian ideals of perfection, mistakenly often recreate a sort of

‘’blandscape’’ of cluttered stores, which lands in the etymology of the word utopia, the Greek

word for “no-place” (Warnaby & Medway, 2018). Jewell (2001) states that malls are often lacking the essential elements of soul and ability to build relational networks, thus becoming

5

a building for “placelessness” and it is through customer experience and engagement a mall will gain its identity.

Sweden currently has 250 malls and stands for an annual turnover of 177 billion crowns (HUI, 2020). “The retail apocalypse” has been a common word in the media for some time, and dead malls have been pointed out as an indicator that retail is dying (Taylor, 2019). Nevertheless, the truth is that boring retail is dying (Ferreira & Paiva, 2017). Between 2010-2016, 20 malls out 40 500 in the US closed, which in relation to the total amount is considerably small (HUI, 2020), and the causes goes beyond a downturn in retail. However, this challenging situation serves as a reminder for shopping malls that they cannot be static in their role; they need to adapt and be shaped to what consumers ask. The paradigm shifts for malls going towards experiences is altering the role it fulfils (Westfield, 2020). Consumers spend longer sessions at the mall which creates a more significant emphasis on culture and not solely on shopping, since experience has moved from a consequence to a purpose (Kim, Lee & Suh, 2015).

Several scholars have proposed the idea that society culture is built in retail spaces where consumers' experiences and identities are formed (Gardner & Sheppard, 2012; Shields, 1992; Hollenbeck, Peters & Zinkhan, 2008; Shim & Santos, 2014). A shopping mall can be seen as a place that is equivalent of a retail version of a theatre where consumers roles and rituals are a part of shaping an experience, but also contribute to self-fulfilment (Langrehr, 1991) since it allows consumers to engage and transform their own identities (Varman & Belk, 2012). However, it is also necessary to consider that the role of malls and the meaning for consumers vary between countries and cultures (Farrag, El Sayed & Belk, 2010). Shopping malls are heavily rooted in American consumption (Kowinski, 1985; Ahmed, Ghingold & Dahari, 2007), while in third world countries, it is a new phenomenon providing a passage for consumers to enter a desired western lifestyle (Varman & Belk, 2012).

2.2 Consumer behaviour

2.2.1 Service dominant logic

The service-dominant logic theory was introduced by Vargo & Lusch (2008), marking a shift from the traditional good-dominant logic. They sustained that the fundamental unit at the base economic exchange consists of service. Under this perspective, consumers do not acquire goods and services but receive resources to generate services. This theory produces plenty of new marketing theories that changed the view on the mechanics of value creation completely. The change of perspective affects even the nature of the service, which is made of processes and is built on the fundamental and central role of intangible resources like competencies and abilities (Vargo & Lusch, 2008). Products are only a means through which consumers satisfy their needs and desires through the process of utilization and

6

consumption. It derives service to be the utilization of resources that belongs to somebody for benefitting somebody else.

A service-dominant logic opens a new frontier even for what concerns the value creation process (Bettencourt, Lusch & Vargo, 2014). It causes a shift from looking at businesses not only as input to output conversion but as a process for co-creating value with customers (Grönroos & Gummerus, 2014). The shift also contributed to the birth of the term

‘’Servitization’’ which refers to industries selling goods that started using a service approach

rather than a one-off sale.

2.2.2 The mall experience types

Bagozzi (1975) expressed that marketplaces are generally a mix of different exchanges where consumers go to both fulfil their utilitarian needs but also their psychological and social needs. Consumers' motivation for shopping may be caused by many different reasons (Eroglu, Machleit & Barr, 2005). However, most literature fails to distinguish the difference between shopping in general and the mall experience, using the same frameworks and assumptions interchangeably (Gilboa et al., 2016). Henceforth, scholars who are seeking to investigate the mall experience fall short since they apply the same framework used to research shopping practice without including the contextual factors that exist for malls (ibid).

Arnold & Reynolds (2003) raise hedonic motivations as a prime reason for consumers to shop. However, it may also be contextual and situation-specific, for example, when a consumer is usually shopping for social purposes but at a given moment switch and realize he/she needs to buy a particular item (Baker & Wakefield, 2012). In a study by Gilboa et al. (2016), they found through their research four prevalent mall experiences that motivate consumers: seductive, functional, interactive museum, and social scene experience.

● Seductive experience is connected to episodes of impulse buying and emotional association with the mall. For this reason, atmospherics as well as the interaction between the person and staff, display a crucial role.

● Functional experiences are shaped by a utilitarian point of view where a goal-oriented behaviour is shown for shopping goods or services; high emphasis is placed on the commercial aspects and less on the mall environment.

● The third type of mall experience is composed of consumers who perceive the malls as an interactive museum. They give great attention to atmospherics and visual displays; hence it is a behavioural pattern primarily based upon exploration in order

7

to find new things with no prior intention of buying a specific good in mind. Much focus dwells on eye-catching visual displays that generate attention.

● Lastly, the fourth type of consumer is the one who sees the mall as a social arena, a centre for interaction and socialization. The commercial aspect is virtually ignored, and the emphasis is set on meeting friends and family as well as other elements that shape enjoyment (ibid).

2.2.3 The servicescape model

Bitner (1992) developed the Servicescape model. This is a framework useful for managing the physical environment of a service encounter. The model has been used by many academics and practitioners as a tool to study and evaluate the performance of a service (Reimer & Kuehn, 2005; Tombs & McColl-Kennedy, 2003). The servicescape is an applied stimuli-response model which has found numerous applications in the service sector. If taking in consideration the evaluation of a service, this model cannot be taken on the side of discussion. The servicescape takes into consideration all those elements present inside a store which are part of the consumer experience such as: external and internal facility’s design, physical layout, and employee’s roles.

The most crucial notion that this framework demonstrates is that the service experience is a combination of physical and human interaction in which an organism (the consumer) reacts to stimuli created by the surrounding actors and factors. For example, during the shopping activity, consumers' experiences are shaped by other actors such as other consumers, and employees but as well as ambient condition, functionality, and symbolism. It is proven by Bitner (1992) that atmospherics can stimulate different cognitive, emotional, and physiological responses inside customer minds. The servicescape model recognizes even the subjectivity of the experience, depending on the consumer's status in the purchasing phase. Indeed, the model takes into consideration the internal personal moderator, such as mood, personality differences, and the purpose of being there, which can shape overall experience judgment.

Previous literature showed that practitioners tend to identify the atmospherics as a critical component shaping the overall experience (Siew, 2011). Several scholars have examined the response of consumers to environmental components in a retail environment (Turley & Chebat, 2002; Sharma & Stafford, 2000; Parsons, Ballantine & Jack, 2010; Turley & Milliman, 2000). Donovan & Rossiter (1982) describe the process of how consumers are influenced by atmospherics as; environmental stimuli, which place the consumer in an emotional state like pleasure or arousal which ultimately affects the consumer's willingness to buy. Like claimed by Gilboa et al. (2016), the dynamics in one specific retail store is not representative for shopping behaviours of a mall in general. However, all necessary factors shaping the

8

atmosphere need to be taken into consideration rather than focus on one factor individually since atmospherics is context-specific, so a holistic analysis is required.

2.2.4 The expanded servicescape model

Considering the shortcomings generated by the servicescape framework, Rosenbaum & Massiah (2011) tried to fill the gap by further developing the model. The authors formulated an expanded servicescape framework which does not only consider the objective and managerially controllable stimuli, but even the perceived environment. The new framework says that a perceived servicescape includes physical, social, socially symbolic, and natural environmental dimensions. As such, the model can complete Bitner’s (1992) framework by adding the knowledge necessary to understand the complexity of the subjective responses generated by the environmental stimuli. Doing so, the model can help managers in better understanding the value generation inside the service setting.

9

In particular, the social dimension expands on Bitner’s (1992) framework by demonstrating that among customers, their behaviours are also influenced by consumption settings and humanistic elements (Rosenbaum & Massiah, 2011). These elements primarily represent other customers and employees, along with their quantity in the ambience and their assert emotions. The socially symbolic dimension extends Bitner’s (1992) work by suggesting that a consumption setting also contains signs, symbols, and artifacts that are part of an ethnic group’s symbolic universe. This possesses specific, often evocative meanings for group members which in turn influence customers differently depending on their customer segment (Rosenbaum & Massiah, 2011).

Rosenbaum & Massiah (2011) marks a new stream of research which opens to the consideration of the subjectivity of stimuli inside the servicescape. Their framework generates multiple implications, both on a managerial and theoretical side. In particular, the authors mentioned the importance of empirically studying the responsiveness to stimuli among different target groups. The expanded model also aids to assist to “understand the

confluence of several environmental stimuli and their dimensions that influence customer behaviour and social interaction” (Rosenbaum & Massiah, 2011, p. 472).

2.3 Rituals

This section will confer a comprehensive understanding of rituals first, and secondly, the focus will shift towards rituals constructs. As Tetreault & Kleine (1990) pointed out, it could be difficult to distinguish habitual acts with rituals. At first, the two categories could seem similar, but if digging into the detailed construct of rituals, the differences will be more evident. Rituals imply the involvement of a main actor and the generation of multiple layers of meanings which develop a big range of emotions; differently from habitual acts which instead can be considered only repetitive actions, learnt and repeated according to a mechanical mechanism.

Starting from the work of Servadio (2018), we found a framework that goes through the multiple components of rituals and permits to identify theoretical components that frame a ritual as such. The work of Servadio mainly takes inspiration from the previous literature written by Tetreault & Kleine (1990) and Rook (1985). Servadio defines rituals as: ‘’An

extraordinary symbolic activity detached from everyday life, carried out through the orchestration of four structural elements: ritual artefact, scripts, actor’s role, and an audience’’

(2018, p. 53).

All these factors are then examined in a ritual setting and interacting with one another for the creation of value. There exist two dimensions of rituals that distinguish them from habits; the behavioural construct of rituals and its structural elements (Servadio, 2018).

10

2.3.1 Ritual Behavioural construct

In this first paragraph, focus will be given to the behavioural construct of the ritual behaviour. Specifically, the focus will be given on three aspects which constitute the main dimensions for identifying rituals.

1. Rituals emphasize both cognitive understanding and ways of doing things.

Social practices are recognized as routine behaviours placed in a social situation. These practices are habitually absorbed within the culture in which an individual has been raised in; it implies a reduced subjective intention compared to rituals. In this context, the subject is merely replicating the social structures without carefulness. A good example could be queuing at the cashier of the supermarket. Rituals, on the other side, require a more conscious awareness or cognitive proactivity (Tetreault & Kleine, 1990). The subjects carrying out rituals require active participation and involvement. Ritual behaviours are constructed by multiple layers of engagement, comprehending the personal experience of attending a ritual occasion and the set of social rules displayed by the belonging culture (McGrath, 2004). An example of a ritual is the ceremony of a family dinner which involves active participation.

2. Rituals displays symbolic meanings, feelings, and emotions.

Practices and rituals have a communicative function for connecting the sender of the message with the external spectators. For rituals, the communicative function is even more marked because in many cases it is associated with rites of passage (Turner, Abrahams & Harris, 2017). The consumption of alcohol for example is considered a transition from childhood to adulthood. The valence of rituals can even come from the symbolic meaning that is rooted in the structure of our society; for example, greeting other people is a symbol that the relationship has been unaltered from the last meeting (Goffman, 1967). Again, in this case, the difference between practice and ritual is a blurred line that depends on the degree of involvement of the subject (Servadio, 2018). Setting the table for example is an everyday routine but setting the table for Christmas eve has a bigger valence in terms of emotions and feelings, which turns a practice into a ritual.

3. Rituals are dynamic.

Practices like rituals are dynamic; this means that by repeating it over time, they can change, adapt, and evolve. Practices, even if standardized by the social construct, are not static actions because its element of the construct (i.e., objects, knowledge, or meanings) changes over time (Korkman, 2006). However, the practice can be considered mechanical due to its repetitive nature. Rituals instead, any time it is performed involve some new improvisation and interpretation carried from the subject. For some rituals, the guidelines of actions can be

11

stricter (i.e., wedding and ceremonies), while others it can be more flexible; it depends on situation to situation (Driver, 1991).

The main difference stands in the fact that rituals are not carried out as mere routine, while they are conducted with consciousness and some degree of improvisation. Improvisation and spontaneity give the ritual events an extraordinary feeling (Servadio, 2018).

2.3.2 Ritual structural elements

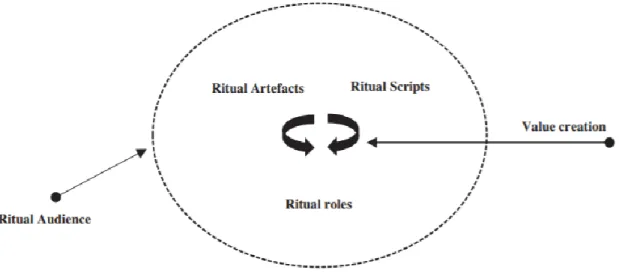

Previously the focus has been on identifying rituals from behavioural characteristics. Now instead the attention will be given to the structural components of the ritual process. According to Rook (1985), there exists some set of features that permits individualized rituals under a mere empirical point of view. Figure 2 presents the framework proposed by Servadio (2018) to show the connection between the four elements contributing to value creation of rituals: ritual artefacts, ritual scripts, ritual roles, and ritual audience.

Figure 2: Framework (Servadio, 2018)

Ritual artefacts

According to Rook (1985), artefacts are consumer products that are used in a ritual setting. These are objects that would be considered ordinary in a standard setting, but if introduced in a ritual context, it turns into a ‘’sacred item’’ having a symbolic meaning. As Rook (1985) observes, artefacts have the power of not only refer to the material and tangible aspect of the object but as well to evocate symbolic meanings that are part of the total experience.

12

Ritual scripts

Considering the ritual as a set of actions happening in sequence implies the existence of a script which set the rules and the time sequence of actions (Servadio, 2018). In some cases, scripts can be formally defined and rigid (i.e., weddings), while in other situations, it can be more loosely and casual (e.g., an everyday meal with family). The script comprehends all those actions, carried out according to certain norms, rules, and conventions. Somehow the script is what guides the actor to choose and consume ritual artefacts (ibid).

Ritual performance roles

As previously stated, these performances of actors are always guided by a predefined script, which can be more or less specific. The most detailed ritual scripts describe the role of each participant, their actions, and their functions. For example, in church celebrations, it is prescribed that the priest has the role of conducting the ceremony, the pages help the priest, the chorus sing and the public listens and intervene with few words. In rituals, every participant has an active role, which can be outstanding compared to the other actors.

Ritual audience

Rituals have an audience, which is composed of individuals taking part in the ritual but not obligatorily having an active role. Sometimes the audience can be intimate, like a family during dinner time and other events can be much broader like a graduation ceremony. During the ritual, actors and audience are connected emotionally through a unique bounding that is characteristic of the social nature of rituals (Driver, 1991). As Servadio states: ‘’A ritual

audience refers to a temporary social gathering in which individuals develop alternative ways of being together and in doing so enhance their sense of togetherness’’ (Servadio, 2018, p. 63).

2.3.3 Value Creation in rituals

In this section, we will dig into the mechanics through which consumers create value from rituals. Specifically, value creation though rituals could be decomposed following the model proposed by Heinonen, Strandvik & Voima (2013), which dissect the query in 5 more questions: how, when, what, who and where value is created and determined? (Servadio, 2018).

How is value created?

’In rituals value emerges through a multi-layered process script-based’’ (Servadio, 2018, p.

219). The value generates through the integration of collective practices and individual experiences. Scripts can be divided in different layers: the first one is the common objectified

13

set of actions that everybody does. The second one is introduced by personal involvement which reveals a subjective interpretation.

When is value created?

Value is created in an extraordinary, temporary timeframe (Servadio, 2018). The extraordinary term refers to a liminoid mental state, specifically this evolves through a longitudinal three stage process (i.e. pre-liminoid, liminoid, and post-liminoid).

What is value based on?

Value is based on customer configuration of feelings, emotions, and material elements. From a service perspective, value is only based on the application of a know-how, (skills and knowledge) on products (Vargo & Lusch, 2008). In rituals, however, the atmospherics or objects in the servicescape are also emphasized (McCracken, 1988) because the materiality is considered the resource that helps customers to express a symbolic idea of value.

Who determines value?

Determination of value has a multiple nature: it can be an individual source and so personal satisfaction or can be collective, fulfilling a need for collectivity (Wallendorf & Arnould, 1991). Therefore, value emerges dynamically in diverse subjects and contexts (Servadio, 2018).

Where is value determined?

The value is determined in customer symbolic ecosystems called communitas. From a service perspective, communitas may refer to customers' ecosystems (e.g. Heinonen, Strandvik & Voima, 2013), wherein a community of customers and other related subjects partake in co-creation and thus all together determine value (Servadio, 2018).

2.3.4 Rituals in shopping

Shopping is a social action, interaction, and experience which structures and influences the everyday practices of people (Falk & Campbell, 1997). In the present consumerist society, individuals shop every day multiple times, inevitably. Nevertheless, everybody has some shopping rituals that are manifested by each consumer's internal processes and preferences. The marketplace’s landscape has changed over time, and so have consumers' behaviour. Consumers nowadays present high-class needs, which attempt to be fulfilled through methods of self-actualization, like shopping. This passage allows members of the society to engage in self-construction of their self-image (Baker, 2006). Shopping, in some cases, can

14

have a potent symbolism, which affixes a deep meaning to the action itself, which is enhancing the significance for the consumer. The marketplace is not anymore the place consumers go for shopping commodities only, but it is the place where consumers go and build their identity in a social context by answering questions like ‘’who am I?’’ and ‘’what do

the others think about me?’’ (Solomon, 1983). People use shopping for different reasons. For

example, some people use it for stress relief as a therapy, others to socialize or to be inspired. Different intentions and motivations move consumers. Some individuals shop to fulfil a social need and strive towards being a part of a social community. In this case, shopping is the action that brings social acceptance; shoppers go through the shelves of stores thinking about what to buy, constrained by the image that they want others to have of themselves (Baker, 2006). Against this background, the correct usage of rituals can be the cause shaping the view a person has about him/herself (Goffman, 1967).

The reasons behind this consumer behaviour stand in the foundation of cultures which are made of different norms and standardized behaviour which determine what should be considered normal and what is not. Human beings naturally judge and evaluate themselves according to their material possessions and belongings (Belk, 1988). However, it is not only the possession that is important to self-identity creation but even the way through which consumers acquire them (Pavia, 1993). In the shopping activity resides an experiential value that is attached to the action itself. It is common today to see people going to the mall only for the sole purpose of going there without a precise consumption need to fulfil. Consumers enjoy going shopping not only for the final consumption, but even for the meaning of the activity itself (ibid).

Several researchers claim that shopping has become a soothing ritual that is vital for the development of contemporary life (Thomas & Peters, 2011; Baker, 2006). Rituals are a way of claiming possession or ownership of an experience, something that illustrates the identity of a consumer because it is created by themselves (McCracken, 1990). Baker (2006) likewise claims that one's identity may depend on and is created by their shopping rituals. It is also something deeply rooted in social relations and contributes to individuals' connection to a group or collective (ibid). Thomas & Peters (2011) state that rituals are essential for determining the way consumers shop and this is something that marketers are conscious about and utilizes this knowledge in order to design advertising and promotions that appeal to consumers.

15

3. Empirical setting & research design

This chapter describes the research design of our study and the process of how empirical data was collected. Firstly, an overview of the research design will be presented following a section describing the path of the pre-study. After this, the steps taken for data collection along with how the analysis of data was conducted will be presented together with raising the empirical setting of the study. In the last section, the chapter concludes by discussing the quality of our research.3.1 Research design

The aim of this thesis is to study consumers' shopping rituals based on individual perceptions and beliefs; the results will not be statistically significant as a quantitative study would seek to find. Given the nature of rituals as a social experience and considering that we aimed to investigate the creation process and how they are given meaning, our research can be considered as qualitative (Denzin & Lincoln, 2000). To conduct qualitative studies, means to interpret a certain phenomenon of which you can gain insights about the underlying reasons, motivations, and opinions (Bryman & Bell, 2011; Sale, Lohfeld & Brazil, 2002). This is in line with our study of consumer rituals and the experience of shopping malls.

Qualitative studies are based on interpretivism (Sale et al., 2002; Secker, Wimbush, Watson & Milburn, 1995) and constructivism (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). From an ontological perspective, several truths and realities co-exist, and they are based on the individual's construction of reality (Sale et al., 2002). Crotty (1998) defines constructivism as realities that are contingent upon social practices and the interaction between the individual actors of which it transmits within a social context. Constructivism does not consider reality as something objectively existing on its own, its mere existence originates from interaction between different individuals (Bryman & Bell, 2011). By considering reality as a social construct, it is continuously changing, which makes it applicable for our study and method due to the fact that realities exist within contexts. From an epistemological perspective, an interpretive path was taken for this study, where we aimed to investigate through interaction with the subject, consumers behaviour and attitudes. Sale et al. (2002) claim that the interviewee and the object of the study are interchangeably linked, which makes the findings co-created and conceived at that moment. Hence, it is not an absolute truth we aim to find as a positivistic approach would do.

Rather than testing a pre-formulated hypothesis, we conducted an exploratory pre-study where the scope of our study emerged from seeing patterns and ideas during the process. In the light of this, it may be appropriate to characterize our approach as inductive (Bryman &

16

Bell, 2011). Unlike a theoretical approach, our study is based upon empirical research focusing on observed phenomena from which we developed insights from, which can be contrasted to theory-driven studies that lack empirical abutment.

3.2 Pre-study

In order to obtain deeper insights within the sphere of Swedish shopping centres and determine the scope of our research, a preliminary study was conducted. Based on literature research, we gained insights and ideas on what we thought would be interesting to explore; hence we conducted interviews with managers of two shopping malls in Sweden. In this section, the motivation, process, and findings will be presented.

3.2.1 Motivation

“2025 is the tipping point year when more than half of the retail square meterage will be dedicated to experiences rather than a product” (Westfield, 2020, p. 4). What brought our

attention to this field was the debate going on regarding the shift for shopping malls moving from product offerings towards becoming a destination for experience. Along with this, the topic covered by the media regarding the death of retails business has been prominent in the sector which made it intriguing to look further into.

3.2.2 Pre-Study Design, Method and Process

As the nature of a pre-study is to explore a subject in order to find alternative paths for our scope, we identified two stakeholders willing to support our research. The aim was to build a basic knowledge of the business and get some valuable insights. We chose to conduct two semi-structured interviews with managers of Swedish shopping malls (Table 1). Even though pre-written questions were brought to the interview sessions, they were hardly used. During the sessions, the focus was on the respondent to freely raise the topics they seemed most crucial and shape the conversation according to that. As this was an exploratory phase of our study, it was more appropriate to let the interviewee steer the interview since we as researchers were scouting the water looking for the most important and relevant topics we could cover. The purpose of the pre-study is to hear their view to guide us rather than testing specific pre-made assumptions (Gillham, 2005). To gather interviews with experts, a snowball sampling technique was used. Through the usage of personal contacts which referred us further, this snowball effect of sampling allowed us to obtain access to relevant actors in the field (Goodman, 1961; Bryman & Bell, 2011). Even Though this technique does not yield us any generalizable results due to its contextualized nature, we were gained access further into a subject and key stakeholder where the referrals helped us to navigate the

17

terrain and find the most relevant actors according to them (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981). Despite the limited amount, we gained sufficient insights in order for us to determine the scope of the research. One interview was conducted face to face and the other one over the telephone.

Both interviews were recorded and transcribed in order to be analysed and to identify relevant statements and key themes that could be used to investigate further in our study.

3.3 Empirical setting

We decided to interview the most relevant target of consumers for shopping centers: Young professionals and families. Our decision is sustained by previous research, which indicates that families (Kim, Kang & Kim, 2005) as well as younger consumers (Bawa, Sinha & Kant, 2019; Zietsman, 2006) are the most vital segments to attract due to their high frequency of visiting and duration of time spent at shopping malls. These consumer segments are also the most important in terms of living status constellations which may be contrasted to kids and elderly that are weaker in terms of buying power. Hence, these two groups were chosen because they represent the most important target group for malls having the biggest consumption inside malls. The criteria for defining the customers segmentation was taken by general and widely accepted definitions of the two customer segments. 1) Families are a constellation of two individuals that are either married or/and living together with children. 2) Young professionals refer to people in their 20s and 30s who are employed in a profession or white-collar occupation, as well as do not meet the criteria of consumer group 1.

3.4 Data collection process

Considering that we aimed to investigate consumer perception on shopping rituals in a contextual setting, a survey would not likely yield the most insightful answers, rather interviews deemed more appropriate due to its flexible nature (Gillham, 2005). Interviews allow us to get as close as possible to participants' practices and realities of which we can develop deep insights from (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe & Lowe, 1991). We chose to conduct semi-structured interviews as it allowed us to obtain a deeper understanding though the possibility to ask follow up questions in order to clarify certain aspects as wells dive further into a subject that the interviewee raised as more important (Bryman & Bell, 2011).

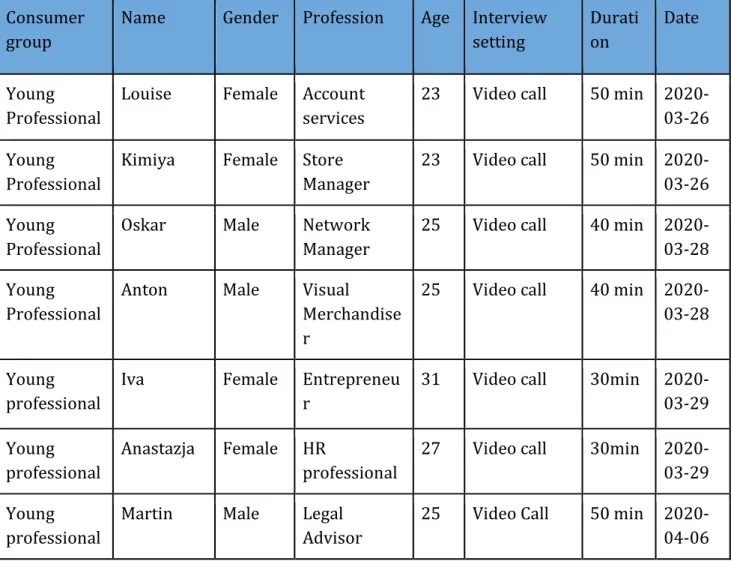

Twenty people were interviewed in pairs, which is ten constellations of people that were interviewed during ten interview sessions in total. They are divided into two groups, young professionals, and families. Each constellation of people knew each other from before and had insights on the others shopping habits. With families, the husband and wife were

18

interviewed together while in the case of young professionals, two friends were interviewed together. Vernham, Vrij, Leal, Mann & Hillman (2014) state that collective interviewing is an appropriate method for detecting truthfulness among pairs. Collective interviewing is common when interviewing deceiving suspects (Vrij, Jundi, Hope, Hillman, Gahr, Leal & Granhag, 2012), however giving the nature of rituals being subconscious, this interview technique deemed appropriate in revealing truths about the interviewees shopping rituals. A convenience sampling method was used for gathering data about consumers which consisted of people easily accessible to the researchers (Etikan, Musa & Alkassim, 2016). In order to avoid national cultural factors affecting the outcome, we set a criterion that all interviewees need to be Swedish citizens. Due to the spread of the Covid-19 virus, physical contact was limited. We initially strived towards conducting face to face interviews, it was an option that was not possible due to the semi quarantine situation in Sweden where people are mostly at home and not willing to meet other people. Hence, we chose to conduct video calls online as it is the next best option available for our qualitative study (Nehls, Kim, Smith & Schneider, 2015).

3.5 Data analysis method

“Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 79). It is an approach for analysing data that codes it

into themes for the researcher to identify patterns. However, what is seen as a theme lies in the eyes of the researcher and its judgment. A theme is not necessarily determined by how big something is; the emphasis is instead placed on relevancy and reoccurrence of insightful data (ibid). Joffe (2012) states that thematic analysis will show the most prominent constellations of meaning in the data obtained; these constellations may include dimensions such as cognitive, affective, and symbolic. Based upon the aforementioned, thematic analysis deemed to be the most appropriate method to use for this study when analysing our data since it is highly compatible with our observed phenomena.

The obtained relevant data from the interviews were transcribed and then coded into themes of which we will compare the answers from the two consumer groups. The answers were coded into the four parts of Servadios (2018) framework based upon: Artefacts, Scripts,

Performance roles and Audience. Using the categorization of consumers provided by (Gilboa

et al., 2016) in our analysis would be helpful in order to see how homogenous families and young professionals are. It could tell us if the difference within each group is based on what type of mall experience consumer, they are such as: seductive, functional, interactive museum or social scene. Together with the expanded Servicescape model by Rosenbaum & Massiah (2011) that may provide it with a deeper service perspective, both these additional perspectives were used in the analysis. Using these three lenses will serve as a tool to determine the source of shopping ritual and the common denominator for specific shopping

19

ritualistic behaviour. Once the themes of each section of interviewees was identified, they were compared to each other in order to see a possible discrepancy with consumers' desires. Based upon this, we sought to find insights into which can be elaborated on and show the implications it has on shopping malls. These insights can assist experts to create a more customer-oriented experience for shopping malls. The steps in this iterative procedure is not to be seen as sequential but rather as a process of which where the data was compared with literature several times (Easterby-Smith et al., 1991; Spiggle, 1994).

3.6 Quality of research

Credibility

Regarding the credibility of our study, more precisely deliberating the level of the truthfulness of the research, we strived to be as neutral and objective in our findings as possible. Lincoln & Guba (1986) raise that confidence in the truth is essential for researchers, meaning that we display an accurate image of what we find and present its real picture. By transcribing the interviews, we minimized the chance for misinterpretations (Williams, 2011) as well as double-checked with our interviewees if any statements were unclear. Cope (2014) claims that by keeping an audit trail, such as interview transcripts, can increase the credibility of a paper.

Transferability

As earlier mentioned, our study is using an ontological approach, which implies that there are several truths rather than one (Lincoln & Guba, 1986). With this in mind, the results of our study are contextual and dependent on the data we gathered, thus should not be seen as something generalizable, and that may be replicated with an identical outcome. We aimed to bring insights based upon the data we gathered in order to bring an understanding of the phenomena observed. This does not exclude that the insights obtained from this study are not useful and valuable. This is merely something the reader should consider if attempting to use the results of our study in another context.

Dependability

For the interview sessions of this study, pre-written questions were used as a guide, which could help future researchers attempt to repeat the study since the same questions may be used again as a guide in order to strive towards having similar conversations as had in this study. However, it should be noted that even though one may use the same questions as for this study, the outcome might be different since the interviewee might raise other concerns, and henceforth follow up questions by the interviewer would be different.

20

Confirmability

In our study, we aimed to ensure that the responses by the participants accurately reflect their ideas and not influenced by personal biases, which supports the claims by Cope (2014). In order to demonstrate the high level of conformability of our study, we thoroughly describe the method process at all stages and how conclusions and interpretations aroused, transparently. In order to increase the confirmability of our thesis, a data audit “…that

examines the data collection and analysis procedures and makes judgements about the potential for bias or distortion”(Trochim, 2006, p. 12), was conducted at the end of our study.

21

4. Findings & analysis

This chapter is divided in two sections. The first one contains the empirical findings originated from our pre-study. The second section contains the findings from our main study and summarizes the results in the end with a table.

4.1 Pre-study findings

Interviews of the pre-study can be found at Table 1 in the appendices.

4.1.1 Increased focus on the experience

This theme that emerged from our discussion was in line with our previous notion that shopping malls are switching towards becoming more focused on experience and service. This is a factor affecting the tenant mix (the offer) and causes a shift in consumer perception of malls. Celinder does not refer to it as a shopping mall anymore, neither a marketplace, but just a place. Due to this shift, malls are turned into a destination of customer engagement which makes it harder to label it since it includes so much more than what a shopping mall used to be.

Celinder states that food and beverage have had a massive peak in 2018, which was a tipping point where consumers put more money on eating out in restaurants, rather than buying it in a store to cook at home. People are living smaller, which is one reason why people go out more. Both interviewees state that to understand what type of experiences to incorporate is a significant challenge for the industry (Felczak & Celinder). Investing in the appropriate experiences, often results troublesome because it is difficult to quantify and measure the impact on business.

4.1.2 Changed consumer behaviour

Consumption is changing, and henceforth, the offer needs to be adapted to it in order to meet the new demands of consumers. The physical surroundings are the factors which influence consumers actions the most. Felczak claims that consumer interaction with other consumers affects the overall experience; this is a factor creating a challenge to form a balanced tenant mix and structure, so different consumer groups do not collide. Considering instead niched stores with a specific audience makes it difficult for them to be located inside a generic

22

environment like the mall. Essentially the risk is to dilute the brand meaning and messages due to being located at a mall. Felczak also supported that the experience consumers have in the mall, affects the consumer's experience in a particular store. Given the outside impression received from the mall's environment, the customer will bring those impressions with themselves when entering a store, which will make the experience different when visiting a brand´s store inside a mall compared to the same brand's store not located in a shopping mall, all other store service factors equal (ibid).

4.1.3 The importance of atmosphere

The third theme is related to the way that shopping malls emphasize on creating an attractive atmosphere. Celinder stated:

"For us, it is important to have something that creates a soul for a premise."

However, which factors shape the environment of a mall is hard to determine and to specify since it is often subconscious of the consumer (Celinder). Celinder made the analogy between a restaurant visit and a shopping mall. Why do consumers prefer one restaurant over another when they have the same menu and location, but there is something untouchable that makes all the difference and is what determines a bad or a pleasant experience. That factor is the atmosphere, and the creation is constituted by many small details. However, what is appealing to some is not the same for others. It depends on the target audience because some concepts work great at one place but terrible in another (ibid).

Malls who take a reactive approach rather than a proactive will most likely land in looking the same as everyone else; destroying all the distinctive features that distinguish one from the other, which will ultimately lead to extinction. Felczak raised that they have moved past fashion and trends of the shopping mall, which has made them develop a unique character for their mall. This is also in line with what Celinder stated:

''You need to be confident in your concept and be brave to stick to it."

4.1.4 Summary of pre-study

To conclude, in our pre-study, we saw three potential themes of which we wanted to analyse further: 1) Increased focus on customer experience, 2) changed consumer behaviour and 3) atmosphere. We discovered that motivation for consumption and reasons are often hidden in the subconscious of the consumer. Rituals are something that manifests these values of consumers which made it an interesting lens to look at in our study. Based on these insights obtained from these two interviews, along with an extensive literature review and discussion

23

with our supervisor, we landed in the decision of looking at ritual behaviours inside shopping.

4.2 Main study findings

The findings presented in this section is the result of the interviews conducted for the main study. This section is divided into four parts according to Servadio (2018) rituals framework and within each part, the findings on the target groups along with an analysis is given. This chapter ends with a table summarizing each part of the framework. An overview of the interviewees is presented at Table 2 in the appendices.

4.2.1 Ritual artefacts

During the interviews, there were hardly any of the interviewees who stated that they have a physical item with them that has a symbolic value that is a part of their shopping ritual. However, what was mentioned several times was the atmosphere which was something Rook (1985) refers to as artefacts that stretches beyond material and tangible aspects, meaning intangible factors such as atmospherics.

Young Professionals

During our interviews with young professionals we discovered that they have more clear preferences of the environment compared to families. A majority of the young professionals expressed their attitudes about the atmosphere of a mall as a prime indicator of what shapes their image of a shopping mall and their level of reluctance or appeal according to that. Jakob stated:

“If everything around is boring, I’ll get a boring image of the store as well. All focus is put on the store if located outside a mall but when located inside a mall, all the restaurants and other things around shapes the impression of a store and everything becomes one big store, you do not see it as separate.”

This also highlights that they highly value consistency of a mall which otherwise will result in a scattered brand image. Anton raised this factor:

24

As the quote shows, it is highly important to consider the mix of offers to go together yet have a clear niche which was raised by a vast majority of the interviewees. A big trap that many malls falls into is to take a conformist approach and have the same offering as every other mall has, which makes them indistinguishable (Ibrahim & Ng, 2002) and lack identity (Kim, Sullivan Trotter & Forney, 2003). Many of the interviewees raise the same problematic and they would appreciate a more niched offering instead. As pointed out by Warnaby & Medway (2018), malls tend to end up in a “blandscape” or a no place which was also lifted by Oskar who gave an example:

“The problem with Åhléns city is that they are trying to do everything but end up being nothing.”

This suggests that young professionals are picky, and they often have a clear view in their preferences.

Families

Among the families interviewed of ritual artefacts, there were more contrasting opinions about how they value the atmosphere. A few of the interviewees stated that decorations and events were factors that they highly value. It creates a pleasant atmosphere, leaves impressions, and influences them which ultimately even affects their experience in store. Klas stated:

“The mall as a whole is very important and how it is presented is the first impression you get which shapes the experience of the visit.”

This is also raised by Bitner (1992) who states that atmospherics stimulates emotional responses and affects the mood of consumers. Ingela raised the importance of the shopping mall environment:

“You chose a mall depending how pleasant it is.”

Despite it might be a deal breaker for some families, others put less value on it and are there simply for functional reasons. Dani stated:

“We do not go there without a reason; we always go there with a shopping purpose. It does not happen that I go there to spend time only. Every time I go, I know what I want to buy, I go directly to the store I need, buy what I want, and then go out.”

25

Analysis

The emphasis you put on certain ritual elements may not merely depend on your demographic group belonging, but also the type of consumer you are in terms of motivations. For the consumer type who sees the mall as an interactive museum, it heavily focuses on displays, decorations and styling as well as the one who shops for seductive reasons, the environment of the mall is the most important factor to look at (Gilboa et al., 2016). It was especially lifted by the interviewees who sees the mall as an interactive museum that the mall in many cases serves as a showroom, hence how this is displayed and perceived effects it a lot. We could see that young professionals to a larger extent visits a mall for this reason while families generally tend to be more functional and practical in their preferences while still enjoying events and decorations.

Related to the physical dimension of the servicescape model, our findings fit well with how you may deploy it in order to create value. “Along these lines, the sign, symbols, and artifacts

dimension refer to physical signals that managers employ in servicescapes to communicate general meaning about the place to consumers” (Rosenbaum & Massiah, 2011, p. 474). By

applying the model to ritual artefacts, you are likely to gain attraction among both young professionals and families.

26

4.2.2 Rituals scripts

Young Professionals

A majority of the young professionals interviewed stated that they are generally spontaneous when shopping, partly the sequence of stores they visit but mostly the planning before. Iva shared her line of thought before going to a shopping mall:

“I define myself as an impulsive shopper. I wake up one day. If I realize that I need something one day or I am missing something, then I go online, but then I want to see it personally or try it, so I go there.”

Young professionals do not have that big of a need to plan in advance, they act on need and execute their shopping fast. Oskar stated:

“Spontaneous, I merely try to find a time slot that works for me.”

A consequence we found of this behaviour is that the shopping process itself is less planned as well due to the fast decision to go shopping, they did not spend that much time thinking of the process and sequence of store visits inside the shopping mall. We found in our interviews that young professionals tend to stay less time per visit although they might go there more frequently than families. However, a strong selling point was a niched offering for a majority of the young professionals interviewed. This was raised by Anton that emphasized on the importance of a niched offering:

“It depends on the mall, if they have a lot of nice niched stores, you’ll stay longer compared to malls with just the generic offering.”

This was a noticeably clear finding among the interviewees, a niched offering is a strong factor that attracts young professionals and has a positive impact on experience.

Servadio (2018) often uses eating to describe rituals where it is a ceremony often rooted in social dynamics and plays an important function to exist but also how it is conducted. A majority of the interviewees raised that they value eating when shopping which is in line with the claims by Celinder. Kimiya stated:

“It is the most important aspect that is a deal-breaker for me. If I am sitting at home thinking about which mall to go to, then I’m going to pick the place that I think has the best food offering.”

However, what several of the interviewees raise is that they feel that the mall environment is too hectic to have a pleasant restaurant experience in, hence it merely becomes a necessity.

27

This was a critic most prominent among young professionals who state that the eating experience is a supplement to the shopping ritual that enhances the overall experience.

Families

During our interviews we discovered that families tended to have a clear plan of their visit to a shopping mall. Nayla stated:

“I always plan, even if there is no entertainment included in my visit. I feel that I always plan before shopping. Regardless of where I go, I think about the means of transportation I should take or if I will walk.”

As stated, the practical part dimension of transportation is also considered in their shopping ritual which was also raised by Marwan:

“When I go to the Mall of Scandinavia it means I need to plan in advance because it is far away and so it automatically involves some planning. Especially when I go there for events like movies.”

Ingela described the shopping ritual she and her sister together has served a larger purpose than merely a pleasant experience, it is something that symbolizes their bond and is an activity for them that makes them connect despite not seeing each other for a long time. They always go to the same shopping mall; have the same path of stores they browse and eat at the same restaurant. When asked how she plan their shopping venture:

“It is implicit. It is not something that needs to be planned, it has always been like that and there is no need to plan since both expect it.”

In the interviews, we could see a tendency for families being more inclined to have a pre-set routine rather than young professionals who to a larger extent may be more spontaneous. Nonetheless, when dug more deeply, even people who see themselves as spontaneous shoppers also have systematic sets of actions following a similar procedure when shopping. This indicates that rituals often may be subconscious, and values are hidden which is in line with the results from the pre study.

Analysis

Our results indicate that people who shop for functional reasons often have a pre-planned routine for their shopping ritual that is based on their objective of products to buy. Even though the type of products being bought may be similar, the logic of their path in a mall is