1

Moving Beyond

Trade-offs

BACHELOR DEGREE PROJECT THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Sustainable Enterprise Development AUTHOR: David Appelqvist & Maja Paulsson

JÖNKÖPING: May 2020

Exploring the linkage between Financial Return and

Social Impact

2

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Moving Beyond Trade-offs: Exploring the linkage between Financial Return and Social Impact

Authors: David Appelqvist & Maja Paulsson Tutor: Oskar Eng

Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Investing management, Trade-offs investment, Social & financial return

Abstract

Background: A growing momentum around the potential of impact investing to contribute to development in both environmental and social sustainability has challenged the way business is operating, offering solutions for both the people and planet. Previous studies have claimed that trade-offs between purpose and profit are inevitable in order to successfully achieve sustainability goals, which requires practitioners in the financial discipline to invent new investment approaches to manage dual outcomes. Here, it becomes evident to move beyond trade-offs to avoid that one goal outperforms the other, considered as a vital question to address towards a new investment paradigm.

Purpose: This study aims to explore the nexus between social impact and financial return, and thus understand the different factors that enable managers in the impact investing industry to successfully manage the trade-offs between pursuing dual values.

Method: An interpretivist approach is followed throughout the study with an exploratory nature that is used to analyze two company cases. In total, two participants were interviewed through qualitative and semi-structured questions; two managers in the impact investing field.

Conclusion: The findings reveal the interconnection of impact measurement, values and impact management. The authors have derived a model that graphically represents the Impact-Return Nexus Model (IRNM) which enhances the impact awareness and long-term value creation. The result of this study shows how the synergy between social impact and financial return will improve the performance on both sides. Accordingly, the cases present that a nuanced impact-approach tends to scale both impact and profits.

3

Table of Content

... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ... 5 1.1BACKGROUND ... 5 1.2PROBLEM DISCUSSION ... 91.3INTRODUCING THE COMPANIES ... 10

1.4PURPOSE STATEMENT ... 11 1.5RESEARCH QUESTION ... 12 1.6DELIMITATIONS ... 12 1.7TERMINOLOGY ... 13 2. FRAME OF REFERENCE ... 14 2.1IMPACT INVESTING ... 15

2.2NEXUS BETWEEN SOCIAL IMPACT AND FINANCIAL RETURN ... 18

2.3INSTITUTIONAL COMPLEXITY AND HYBRID ORGANIZING ... 19

3. METHODOLOGY & METHOD ... 23

3.1METHODOLOGY ... 23 3.1.1 Research Paradigm ... 23 3.1.2 Research Approach ... 24 3.1.3 Research Design... 24 3.1.3.1 Multiple-Case Study ... 25 3.2METHOD ... 25 3.2.1 Data Collection ... 26 3.2.1.2 Selection Process ... 26 3.2.2 Interviews ... 28 3.2.2.1 Interview Questions ... 28 3.2.2.2 Semi-structured Interviews ... 29 3.2.3 Credibility ... 30 3.2.4 Validity of Fieldwork... 30 3.2.5 Reliability of Fieldwork... 31 3.3DATA ANALYSIS ... 31 3.4ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 33 4. EMPIRICAL FINDINGS ... 34

4.1IMPACT INVEST SCANDINAVIA... 34

4.1.1 The Impact Journey ... 35

4.1.2 Impact ... 36 4.1.2.1 Long-term view... 37 4.1.3 Values ... 38 4.1.4 Impact Management ... 39 4.1.4.2 Business Model ... 39 4.1.4.3 Sector specialization ... 40

4.2LEKSELL SOCIAL VENTURES ... 40

4.2.1 The Impact Journey ... 41

4.2.2 Impact ... 42

4.2.2.1 Long-term view... 43

4

4.2.4 Impact Management ... 45

4.2.4.1 Business model ... 47

4.2.4.2 Sector specialization ... 47

5. ANALYSIS... 48

5.1IMPACT INVEST SCANDINAVIA... 48

5.1.1 The Impact Journey ... 48

5.1.2 Impact ... 49 5.1.2.1 Long-term view... 49 5.1.3 Values ... 50 5.1.4 Impact Management ... 51 5.1.4.1 Business Model ... 52 5.1.4.2 Sector specialization ... 52

5.2LEKSELL SOCIAL VENTURES ... 53

5.2.1 The Impact Journey ... 53

5.2.2 Impact ... 53 5.2.2.1 Long-term view... 54 5.2.3 Values ... 54 5.2.4 Impact Management ... 55 5.2.4.1 Business Model ... 56 5.2.4.2 Sector specialization ... 56

5.3MOVING BEYOND TRADE-OFFS ... 56

6. CONCLUSION ... 58

7. DISCUSSION ... 60

7.1THEORETICAL CONTRIBUTION ... 60

7.2MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS ... 60

7.3LIMITATIONS ... 61

7.4SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH ... 62

REFERENCES... 63

FIGURES ... 69

FIGURE 1.SPECTRUM OF IMPACT INVESTING ... 69

FIGURE 2.IMPACT VALUE CHAIN ... 69

FIGURE 3.PROCESS OF DATA ANALYSIS ... 69

FIGURE 4.IMPACT-RETURN NEXUS MODEL (IRNM) ... 69

TABLES ... 70

TABLE 1.FOUR CORE CHARACTERISTICS OF IMPACT INVESTING ... 70

TABLE 2.SEARCH PARAMETERS FOR FRAME OF REFERENCE ... 70

TABLE 3.OVERVIEW OF INTERVIEWS ... 70

TABLE 4.OVERVIEW OF CASES ... 70

APPENDICES ... 71

APPENDIX 1.FIGURES FROM SURVEY GIIN2019 ... 71

APPENDIX 2.PRE-QUESTIONNAIRE... 72

... 73

5

1. Introduction

In the first chapter, the authors introduce the background to the choice of subject which includes the relevance of this study. Further, the problem discussion and gaps are revealed, followed by introduction of companies, purpose statement, research question and delimitations of the study. A terminology list of definitions used in this paper are presented.

1.1 Background

In today’s society, we are living in a world that is experiencing a rising wave of environmental problems, e.g. degradation of natural resources, loss of biodiversity, climate change, and social problems, e.g. growing poverty, inequality, and ethical dilemmas. An universal effort in addressing the global challenges of environmental, social and economic development has been presented by the United Nations’ in the 17 “Sustainable Development Goals” (United Nations, 2015). In the past decades, the primary focus of the sustainability debate has been the degree to which environmental goals often are at the expense of economic growth.

In the business world, stakeholders direct and indirect needs are central in sustainable development, defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without

compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland,

1987). Applying this definition of sustainable growth to the financial sector, two aspects appear to be relevant in this study. Firstly, capital has a function to be stored for a long period of time, which shows that the financial discipline has the ability to meet, or not to meet, the needs of future generations. Secondly, mainstream finance is characterized by short-term approaches and profit-maximization which is proven to undermine sustainability practices (Soppe, 2004). Therefore, new investment approaches are needed to achieve a balance between “doing good” and “doing well” (Emerson & Bonini, 2003).

6

However, it has become evident that trade-offs are inevitable to achieve the sustainability goals as realization of one target goal may restrain or be at the cost of others. Hence, there is a need to ensure collective action among multiple actors across sectors since conflicting interests are identified as the main reason why the implementation of the SDGs is not fully achieved. It opens up for a dilemma of how to coordinate these problems and reach a win-win solution, which remains unsolved (Barbi et al., 2017).

Furthermore, since the inception of e.g. environmental finance, socially responsible investing and social impact bonds, the financial sector has contributed to sustainable progress in a positive manner (Wiek et al., 2014). The origin of impact investing began in 2007, where the Rockefeller Foundation held a conference for philanthropists and investors to discuss new funding opportunities with positive social and environmental impact. The former president, Judith Rodin, stated in her speech that if impact investments would be part of traditional finance and represent only 1% of the world’s managed assets, the future would turn into a much better place. In this way hundreds of billions of dollars would be aimed towards some of the world’s most pressing social problems (Brandenburg & Rodin, 2014). These discussions eventually formed the term impact investing (Höchstädter et al., 2014).

For the purpose of this review, we focus on the field of impact investing, defined as the intention to direct capital to companies that are expected to yield positive social and environmental outcomes in addition to financial gains (Reeder & Colantonio, 2013). Impact investing goes along with the promise of responsible investing and sustainable investing, that is to provide the market with a scaled positive impact that solely governmental authorities and non-profit organizations are not able to do alone (Cangioni et al., 2015). Unlike traditional investors, impact investing is unique in the sense that it has a direct interest in the nature of measurable social and environmental outcomes. This approach encourages multiple sectors and actors with the possibility to generate dual returns (Andersen et al., 2018).

The essence of impact investing has emerged from different investment types, shown in figure 1. Based on this spectrum, impact investing can be defined as an investment

7

approach that ranges between traditional investing and philanthropy (Sonen Capital, 2020).

Figure 1. Spectrum of Impact Investing.

Furthermore, impact investments are considered as an important force towards sustainable transformation with the potential for remarkable scaling in addressing social and environmental problems (Andersen et. al., 2018). Besides the potential of generating positive social and environmental outcomes, impact investors contribute to organizational growth by providing capital funding for social entrepreneurs and to the development of social innovations (Ormiston et al., 2015).

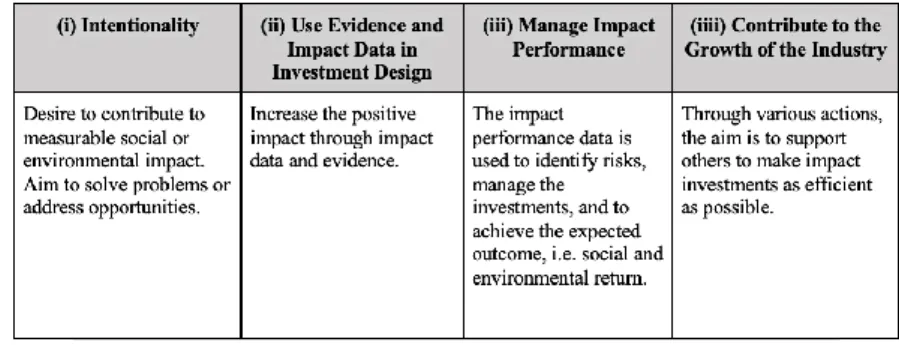

Today, the marketplace of impact investing consists of an ecosystem of global standards and networks with various actors involved such as non-profit organizations, governmental authorities, private foundations, and institutional investors (Andersen et al., 2018). In order to define the practice of impact investing, leading investors have created four core characteristics of impact investing (See table 1). These serve as reference points for investors and will help them to understand fundamental aspects of impact investing (GIIN, 2020).

8

Table 1. Four Core Characteristics of Impact Investing.

The generally accepted system to measure impact intentions into impact results is IRIS; the impact reporting and investment standards. This system is managed by the Global impact investing network, which aims to inform investors on impact management decisions to drive greater impact results. Together, they provide impact data and how-to-guidance for practitioners in the field to increase performance (IRIS, 2020). Despite the fact that impact investors have different intentional levels on both impact and financial return, their financial performance is often reported to be in-line or outperform expectations. According to a survey conducted by GIIN (2019), most impact investors pursue market-rate returns (see Appendix 1).

Although there are recent studies that support the broad adoption of impact investing, lack of conceptual and practical clarity may constrain the growth of the market. More specifically, investors are facing difficulties to enter the market due to this uncertain framing which hinder both governmental support and incentives for environmental and social investments (Höchstädter et al., 2014). Consequently, challenges of how to access sustainability performance of companies and how to measure social and environmental returns appear central in the current debate (Bertil, 2016).

9

1.2 Problem Discussion

Global Challenges

It is evident that today’s society is facing intractable social dilemmas and degrading environmental problems due to lack of renewal and innovation. As stated by Statistics Sweden, most of the co2 impact is generated by multiple actors, e.g. public and private actors, non-profit associations and individuals, whose activities in society are the major forces of rapid economic expansion and productivity (Statistiska Centralbyrån, 2019). Accordingly, different actors in society are all contributors to the global crisis and need to take collective responsibility in the transformative phase of achieving sustainable development (United Nations, 2015). Consequently, the financial sector is facing new and long-term solutions needed to address these challenges.

Incentives for Social and Environmental Innovations

Historically, there has been a lack of funding for social innovations. Impact investors are a new type of investees that account for social, environmental, and economic returns. The market for impact investing is currently in development although there are barriers that hinder its expansion (Höchstädter et al., 2014). Access to funding and capital for social entrepreneurs is a challenge in order to ensure organizational growth and contribute to a holistic impact (Bugg-Levain et al., 2011).

Impact Investing Market

Currently, traditional investors are concerned with how to connect financial incentives to measurable social and environmental outcomes. Due to lack of demand and supply for long-term approaches, there are limited developed standards and financial models available in impact investing (Höchstädter et al., 2014). With regards to the uncertainty of financial and impact returns in the investment field, the authors have identified an opportunity to investigate this way of conducting business further. Additionally, there is a need for an understanding of how impact investors conduct their business to overcome structural challenges and decrease risk associated with innovation and investment decisions. According to GIIN’s report in 2019, business model execution and management risk are considered as the most severe contributors of risk in impact investment which shows a gap between investor interest and knowledge (GIIN, 2019).

10

Existing studies have addressed the challenges and opportunities associated with measuring and delivering social impact. Hence, there is a gap between interest and information on how to successfully manage impact investment outcomes. Most studies that have explored the expectations and performance of impact investing have lacked critical and theoretical components (Agrawall, 2019).

Based on these problems, we have identified both an opportunity gap; exploring the linkage between financial return and social impact, and a knowledge gap; understanding how financial incentives and intentional social impact are managed on firm-level.

1.3 Introducing the companies

Impact Invest Scandinavia

Impact Invest was founded by Ruth Brännvall in 2012 and started as the first investor network in the Nordic region for impact investments. Today, Impact Invest is an advisor and intermediary with the aim of increasing capital and financial solutions for social entrepreneurs with the potential to tackle the most urgent social issues. Their various activities include running a networking platform where members of the network, both entrepreneurs and investors, are offered training in how to create, measure and

implement social investments.

Leksell Social Ventures

Leksell Social Ventures provides social entrepreneurs and ideas in society with resources needed to drive social development and effectively tackle pressuring social problems. Founded in 2014 by Laurent Leksell, LSV offers direct investments on scalable and measurable social ideas and outcome models that enable increased social services in society leading to greater impact results, also known as social impact bonds. Their goal is to contribute to social innovation and a better Sweden through their network of private, public and non-profit actors.

11

1.4 Purpose Statement

The purpose of this study is firstly to investigate and examine the connection between financial returns and social impact returns. In specific, the aim is to understand the different factors that enable company managers in the impact investing industry to successfully manage the trade-offs between financial returns and social impact outcomes.

By investigating impact investors in the impact investing field, our aim is also to see if there are any opportunities in practice where there are no trade-offs between financial return and social impact return. It is considered as a vital question to address in the investing industry since there is no commonly used framework that is broadly accepted and allows impact investors to decide whether and how to invest without trade-offs (Evans, 2013).

With regards to the identified challenges and unsatisfactory studies discussing these topics, the purpose is to investigate decision making and its trade-offs effects (hindering or fostering) on impact outcomes.

Furthermore, we aim to raise awareness of what impact one can make, mainly in terms of investors through capital funding but also to encourage entrepreneurs to contribute to a wider impact through renewal of their business models. Hence, we are interested in how the market of impact investing can further progress because we believe this topic is important in order to facilitate sustainable solutions. It is our personal belief that positive societal impact and negative externalities should be a part of evaluation models in corporate finance in order to create support and incentives for sustainable innovation and progress.

12

1.5 Research Question

In order to meet the purpose of this study, the following research question has been developed.

RQ: How do these companies manage the trade-off between financial returns and social impact when conducting their business?

1.6 Delimitations

As stated in the background, impact investing is an emerging investment strategy where the marketplace of impact investing consists of an ecosystem of global standards and networks with various actors involved (Andersen et al., 2018). However, the scope of all actors in the field is too large for this single study, therefore the focus has been limited to impact investment companies in Sweden. Thus, the selected companies are seen as pioneers and highly influential in the impact investing industry in the Swedish context.

The study has also been limited to managers in the field of impact investing, and the analysis is limited to how they conduct their business and manage the trade-offs that arise when investing for both financial return and social impact.

13

1.7 Terminology

Hybridity: A combination of multiple organizational identities, multiple organizational forms and multiple institutional logics (Battilana & Lee, 2014).

Impact: The difference between the given outcomes of a certain action, and the outcomes without it occurring (Reeder & Colantonio, 2013).

Impact investor: A person with the intention of delivering social and environmental impact alongside financial returns (Mendell et al., 2013).

Impact investing company: An enterprise with the objective to maximize positive impact for their clients, partners, and society at large (Emerson & Bonini, 2003).

Investment manager: A person that is responsible for investment processes on behalf of clients (Investopedia, 2019).

Paradox theorising: Accepting conflicting tensions between elements that persist over time to stimulate creativity (Mogapi et al., 2018).

Social impact: How people and the society are affected by outputs and outcomes of a company's activities (Höchstädter et al., 2015; Ormiston et al., 2015).

Stakeholder: A person with an interest in an organization's achievements that can affect or be affected by the organization’s activities (Fassin, 2009).

Trade-off: A decision that involves an exchange where one return is being sacrificed for another of more or equal value (Glac, 2008).

14

2. Frame of Reference

In this section, the frame of reference is presented. It follows the process of collecting an assortment of literature related to the topic of interest. Further, a review is presented on the theoretical framework of previous studies on impact investing; the terminology, the nexus between financial return and social impact, and the institutional complexity and hybrid organizing.

In the following, the Frame of Reference is the result of a research based from a systematic review, that is a research with the aim to identify, analyze and summarize the existing literature within the topic of interest. Firstly, we selected a large amount of peer reviewed articles that were suitable to the purpose of the study. As the topic is a relatively new phenomenon, we chose to direct our attention to research that has been conducted in the past ten years to access the most recent knowledge. Further, we selected journals in the ABS guide to justify credibility.

Table 2. Search Parameters for Frame of Reference.

In the process of sorting literature, we scrutinized the articles in order to move from a broad to narrow selection of relevant articles. The purpose of the following frame of reference was to guide the reader from a holistic approach to the topic of interest. As the fundamental of the whole study is the practice of impact investing, we defined the concept and its terminology in the first subject. Furthermore, we introduced the theoretical framework including concepts and models evaluating social and environmental return.

15

Ultimately, we guide the reader through the nexus between social impact and financial return and the institutional logics and hybrid organizing in impact investing.

2.1 Impact Investing

The market for impact investors is growing, thus conceptual and practical definition of the term becomes more evident. The terminology of impact investing is still relatively new to the market, however, it is emerging within the investment industry. The simple definition of impact investing can be described as investments that generate a positive social, environmental and economic impact, while achieving a financial return (Mendell et al., 2013; O'Donohoe et al., 2010). Moreover, similarities between philanthropists and impact investors are identified, where impact investors constantly aim to attain social objectives (Brest et al., 2013). Multiple scholars describe impact investors as socially motivated. Furthermore, impact investing occurs when there is a specific need and a linkage between impact investing and the bottom of the pyramid, since it often targets customers from developing countries with low incomes (O’Donohoe et al., 2010).

Blended Value Approach

In impact investing, there are various actors and creators that play different roles in the creation of environmental and social returns.

“In truth, the core nature of investment and return is not a tradeoff between social and financial interest but rather the pursuit of an embedded value proposition composed of both.”

- Emerson & Bonini, 2003.

The conceptual foundation that commonly describes the base of impact investing is the “Blended Value Proposition”, invented by Jed Emerson in the beginning of 2000s. Additionally, in order to understand the implications one needs to move beyond the conventional belief that economic value “doing well” is at the cost of social value “doing

good” (Emerson & Bonini, 2003). This approach states that all organizations’ have the

16

non-profit motives. Therefore, they are enabled to continuously create all three types of values while investors provide capital funding.

Theory of Change

Impact investing is generally defined in two key factors, such as (i) the intent of the investor to attain social or environmental impact and (ii) the tangible outcome of the impact. A third factor describing the change initiative and how to achieve the goals is comprehended in the theory of change (Jackson, 2013). The theory of change defines the philosophy, assumptions, effects, correlations and expected results of any project or program. The change initiative arises in program evaluation and when analyzing the performance data. Moreover, the theory of change is a way to measure data and performance of impact investments, which also can be used together with other data collection and analysis methods. Another assumption of the theory of change is that it empowers all parties to better accept and enhance the processes of change (Bertl, 2016). The core elements; intent, impact and change, and their correlation, is an ongoing discussion in the field since the theory of change is not seen as an acceptable tool, instead it is seen as a useful framework within the field of impact investing (Jackson, 2013).

Terminology

Based on this understanding, impact investing follows the line of responsible investing, which considers social, environmental and governance issues in the investment decision. In contrast, the impact investor has the intention to invest if the outcome is positive social or environmental impact (Bugg-Levain et al., 2011). Some critiques have been expressed regarding the nature of impact investing. More specifically, any investment is considered to have the potential of creating a positive social or environmental impact, yet some approaches are closer to the activity than others (Bugg-Levain et al., 2011).“Impact washing”, which is the practice of labeling investments to benefit from the positive attributes of a trend, is assumed to increase as the market grows (Harji, 2012). Hence, there is a need for a clear understanding of what impact investing stands for, both in terms of conceptual basis and practice, before the market experiences exponential growth (Höchstädter et al., 2014).

17

Some scholars argue that impact investing goes under the same meaning of responsible investing and sustainable investing, as these investment forms are similar in their approach to integrate non-financial issues in the investment process. Although impact investing often is associated with many other terminologies, for instance social finance, mission-related investing, and triple bottom line, it differs in the attempt to address social and environmental concerns while generating financial gains with the predicted social or environmental outcome being central (Hebb, 2013).

In difference to traditional investments, impact investments are different through their hybrid goals (Doherty et al., 2012). As such, impact investments mismatch with both the logic and tools in traditional finance. New approaches are needed for investments that have the intention of achieving measurable social and financial return, thus a key component of such investments is the measurement of potential social and/or environmental impact of the investment (Brandstetter et al., 2015).

The Impact Value Chain

Assessment of impact is the process of recognizing future effects of a given action and measuring the proposed outcomes (Reeder & Colantonio, 2013). By its nature, it provides information on projects to guide actors and stakeholders involved in decision making. In the business context, the impact value chain can be viewed as a practical framework since it makes crucial contrasts between inputs needed for a given change, the activities that apply to those inputs, and the outputs that results from the activities. In Impact investing, outcomes that can be measured in both quality and quantity are significant in order to estimate the intended impact and net change. Moreover, a model that was created to show how to generate social value is seen in figure 2. It describes the impact value and how to separate outputs from outcomes, also described as the intended impact of an investment (Clark et al., 2004).

18

Figure 2. Impact Value Chain.

2.2 Nexus Between Social impact and Financial return

The concept of social responsibility has been discussed for many decades and indicates a strong relation to social impact and financial return. Thus, managers in traditional businesses usually view social responsibility as an expense of the business that consequently have a negative effect on the financial returns (Friedman, 1970). However, Friedman argues that this is not the case, and that companies that seek profit at the same time in respect to their social responsibilities will be better off in the long run. In addition, organizations may include social impact into their strategies to increase the total business value (Emerson & Bonini, 2003). These statements have formed the interest and practice of impact investing since the drivers of the market is that investors can seek social impact and financial return simultaneously (Agrawall, 2019).

Furthermore, conventional investors that consider impact investments have the desire to know if their primary goal of generating financial return will be affected by their secondary goal of creating an impact. Conventional philanthropists usually reflect on the same problem but on the contrary. This is one reason why the relationship between financial returns and impact needs to be defined (Saltuk, 2011). Investors consider factors of risk, return and impact when making investment decisions. However, these will alter depending on their intentions. This assumption is classified in two investment strategies, i.e. financial-first and impact-first (Ormiston et al., 2015). The financial-first investors tend to be traditional banks, pension funds, and institutions that seek market-competitive

19

financial return. On the other hand, impact-first investors tend to be different kinds of foundations and charity organizations, and their main intention is to generate social and environmental returns with a minimum level of financial return. In contrast, the categorization might be divided into financial-first and impact-first investors depending on their choice of return, and that each set of return varies from investor to investor (Reeder & Colantonio, 2013). Accordingly, impact investors’ business models are defined by their willingness to sacrifice social impact or financial return, which means that impact-first investors sacrifice financial return while financial-first investors tend to do the opposite (Evans, 2013).

The subject and the tension between financial and social return have for a long period been a prominent dilemma within the field of impact investing. However, according to Evans, there is no acknowledged framework that empowers impact investors to predict how they will be capable of investing without a trade-off (Evans, 2013). A framework would facilitate investors to develop investment strategies for increased economic returns and social impact, but also for understanding and adapting specific investment contracts. The trade-off is common due to the rare case of investments that generate both a financial return and social or environmental impact. In addition, the ideal state in impact investing is when there is no existing trade-off between financial return and social return, instead they are integrated with each other (Ormiston et al., 2015). Nevertheless, an interesting study showed that the majority of impact investors were willing to sacrifice financial return for a larger impact and believed that the trade-off between impact and financial return was not necessarily a choice (Saltuk, 2011).

2.3 Institutional Complexity and Hybrid Organizing

Institutional logics

Impact investing and social entrepreneurship are emerging in contradictory fields, thus are dealing with different institutional logistics in mainstream finance and philanthropy (Battilana et al., 2014; Pache et al., 2010). Practitioners in these fields are exposed to high expectations in successfully mastering institutional demands of finance logics, i.e. maximizing economic value for owners, and philanthropy logics, i.e. welfare engagement

20

and generation of positive social and environmental values (Greenwood et al., 2014). However, as impact investors and social ventures experience pressure to comply with competing demands on performance, navigation is required to deal with institutional complexity. In order to remain profitable and produce new innovative solutions, impact investing organizations are struggling to prevent that one logic outperforms the other resulting in business failure (Jay, 2013).

According to literature, social enterprises generate income to cover their costs without accepting financial donations (Hart et al., 2008). Hence, the end users of their products and services are often a mission oriented and severe group of clients with less financial possibilities. This indicates that prices need to be low to meet the user’s preferences and simultaneously be competitive in order to successfully carry out a conventional business model, which is difficult as success of one implies the other. This self-sustainable approach is considered as one of the most distinct reasons why financial sustainability is challenging to achieve for social enterprises (Doherty et. al., 2014).

Hybridity

Furthermore, one important characteristic of social ventures that distinguish them from pure capitalist firms and philanthropic organizations is their simultaneous effort in pursuing social and financial objectives, defined as hybridity (Mersland et al., 2020). Additionally, impact investing organizations share characteristics from both non-profit and for-profit firms. This business approach features them as hybrid organizations in their aim to integrate different aspects of institutional logics at the same time (Brandstetter et al., 2015).

Moreover, hybridity, i.e. an organizations pursuit in combining economic and social values, is considered as the main reason why conflicting financial and social logics often create tension (Doherty et al., 2014). Consequently, failure to reach a desired balance between the dual logics often results in either an organizational collapse or in a trade-off where the organization is forced to sacrifice one outcome at the cost of one logic over another.

21

Although hybrid organizations are known to combine elements with conflicting identities at its core, research shows that the financial logic in terms of the profit-focus often dominates the impact-focus, in particular when actors are passive in responding to external forces (Mogapi et al., 2019). In this case, the tensions between creation of dual values affects both the organizational culture and the outcome of activities (Pache & Santos, 2013). Pache and Santos identify organizational tensions that can arise in three ways. Firstly, such activities can either result in decoupling, i.e. exposing one image of logic to the public while performing activities internally on the other. Secondly, compromising is the activity that guarantees that a minimum level of each logic is followed. Thirdly, combining, i.e. focus on integrating the tensions, that through creation of an organizational identity ensures logics are maintained together.

As such, organizations can manage conflicting logics by separating one from the other or removing them (Mogapi et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the aim of hybrid organizations is to operate in balance between generating social impact and financial return since mastering both logics defines a successful business (Hart et al., 2008). In other words, a social venture is considered successful if it can deliver social value while remaining financially self-stable.

Paradox theorizing

With regards to the tensions that arise between conflicting logics of social and financial motives, paradox theories have emerged in response to how to pursue both (Jay, 2013). Instead of determining whether to trade-off one logic over another, paradoxes should be managed over time in order to achieve a balance between the forces (Mogapi et al., 2019). Although reaching an equilibrium is the desired state, one prominent assumption in paradox theorizing is that conflicting tensions can be accepted as a source for innovation and welcomed new opportunities.

Furthermore, the study of new organizational forms challenges the nexus between financial returns and social or environmental impacts, which is in an area in development. In the studies of the demonstrated tensions, social enterprises have been the focus and have contributed to the emergence of organizational approaches that apply, for instance, the paradox theory, stakeholder theory, and institutional theory (Besharov et al., 2013).

22

Impact investors are operating in a broad field where existing models for different types of hybrid organizations tend to be incompatible. However, many scholars argue that actors in impact investing operate at the nexus of dual logic demands instead of responding to other pressuring demands that require them to either decoupling or compromising. In contrast, impact investors aim to deliver different types of value and seek to identify hybridity that allows for change when dual logics require it (Battilana & Dorado, 2010; Pache & Santos, 2013).

23

3. Methodology & Method

3.1 Methodology

The third chapter of this thesis presents the research philosophy and process applied throughout this study. This part also describes the research approach, data collection and selection process used to conduct the study. It follows a process analysis leading to the final discussion on ethical considerations.

3.1.1 Research Paradigm

When conducting scientific research, the research paradigm is the part of methodology that refers to the philosophical framework that serves as a guidance of how research should be carried out. The research paradigm is determined by philosophies that consist of the perception of existing nature and knowledge; thus, the same phenomenon can be investigated in multiple ways depending on the selected approach. This part will serve as a base for the selected design and techniques for collecting data and conducting analysis in the study (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Collis and Hussey identified two research paradigms, where interpretivism perceives the phenomenon under study subjectively. This approach acknowledges the different subjects combined in this study and the nature of dealing with the trade-off between social impact and financial returns when conducting business. In contrast, positivism perceives phenomenon objectively, which is not the most suitable approach to adopt in this study due to the limitation of existing knowledge and implemented studies of managing trade-offs between social and economic logics in the financial sector. The uniqueness of the phenomena under study are the main reason why such an approach affected the capability to carry out scientific significance in the research. In order to discover the underlying meaning of how the trade-offs are managed on a company level, interpretivism is the appropriate approach to answer the research questions. Hence, an interpretivist approach allows reality to be shaped from the observer’s interpretation through adopting a subjectively mindset to understand the individuals (Collis & Hussey, 2014), who have

24

experienced the tensions between realizing both social and economic values. Therefore, multiple interpretations and different observations can result from the same interview session.

3.1.2 Research Approach

There are two contrasting approaches that can be adopted when conducting research, i.e. deductive and inductive. This study is a qualitative research that is theory building and will therefore follow an interpretivist research philosophy with an inductive reasoning. An inductive process aims to form an analytical understanding of social phenomena, whereas a deductive process aims to build analytical theories to recognize social phenomena. The objective of this approach is to find an interpretive understanding of a social phenomenon within the selected research question, which is why the interpretivist and inductive approaches are most appropriate for this study (Collis & Hussey, 2014). This approach will also generate opportunities for future research since new theories and hypotheses are developed through the existing knowledge (Bryman & Bell, 2015).

3.1.3 Research Design

The methodologies and methods selected in a study are reflected by the design of a research, with the aim of answering the research questions and fulfilling the research purpose (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The authors of this thesis wish to explore how companies in the impact investing industry manage the trade-off between generating social impact and financial returns when conducting their business. In order to fulfil this purpose, the design applied in this research is an exploratory case study, which is commonly associated with qualitative research that follows interpretivism and the inductive approach (Saunders et al., 2012). This type of exploratory study is appropriate in cases when there are non-existing or few studies conducted relating to the topic beforehand (Collis & Hussey, 2014; Saunders et al., 2012).

25

The main reasons for choosing this approach is the ability to investigate the phenomenon in relation to its real-life context and identify the relations to the external mechanisms. In fact, using two cases is mainly due to the lack of existing studies and by using multiple cases, it could potentially lead to greater understanding of the topic in difference to a single case study. Thus, the insights provided may lead to a greater sufficiency that can be applied to a greater scope (Yin, 2014). In addition, the aim is to explore the linkage between profits and impact as deeply as possible, and, more specifically, to recognize patterns and identify how they affect the cases (Lin, 1998). The limited sample size and the newness of the overall business field create obstacles to use other approaches, such as descriptive or causal, as these would not be sufficient to gain conclusive findings (Ghauri & Grønhaug, 2010).

3.1.3.1 Multiple-Case Study

By conducting a case study, the researcher is allowed to discover insights from observed settings with the potential to collect rich findings leading to theory development (Saunders et al., 2012). In this study, the case consists of a particular business, namely companies in impact investing, with company representatives that are involved in the investment process and experience the management behavior that we are seeking to understand. The main reason for choosing a multiple-case study is due to the possibility to collect data from multiple sources to provide greater empirical evidence, and, more specifically, through conducting an in-depth analysis of the phenomenon under study in a real-life setting (Yin, 2014).

3.2 Method

When conducting research, methods include the steps and tools used to fulfil the purpose of the study (Collis & Hussey, 2014).There are two main methods used to conduct research; quantitative and qualitative, where the first is used in collection of a large amount of data aimed to be tested statistically whereas the latter is used to analyze a small sample in a specific context which is explained by the participants’ perception rather than

26

by set procedures. The phenomenon of this study relies on the interpretation of the respondents’ and their daily experience in work environments. Therefore, knowledge in this study is treated subjectively and will be interpreted in a neutral manner by the authors (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Denzin & Lincoln (2005) describe qualitative methods as a strong relationship between the socially designed nature of reality, and the relationship between the researcher and the study itself, as well as the specific pressure that shape the investigation. Moreover, how social experience is created and how it generates meaning is something qualitative researchers seek answers to. This enables the study to interpret and understand phenomena from the perspective in the field. Therefore, this study focuses on a qualitative study due to its reliance on human experience, where the aim is to recognize difficulties, patterns and trends regarding the topic at hand.

A quantitative research method is not used in this research due to the linkage with a positivism paradigm, and this research is not associated with that philosophy (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

3.2.1 Data Collection 3.2.1.2 Selection Process

A unit of analysis is the data to be collected and analyzed for the research, and could be a particular type of business, a relationship or group of people. Selecting a unit of analysis where decisions are made is the most appropriate way to conduct business research, such as selecting managers, advisers or owners (Collis & Hussey, 2014). In this study, we have selected companies within a specific type of business, namely impact investing.

The process of finding suitable participants for this study was difficult since there is a limited number of actors that work within impact investing in a social venture and in the context of Sweden. The reason why Sweden as context was selected is due to undeveloped research in the impact investing field. The sample selection of this research was limited since the study focuses on a field which is in development and is nevertheless dependent on participants with experience in the field. When selecting companies, the success of their performance was not considered. However, a criterion of the selected companies

27

was that they needed to conduct a business in the impact investing field, preferably as financiers or intermediates, to understand what factors that determine how they invest for social and financial purposes.

Initially, we contacted eight impact investment and social ventures operating with different investment processes, and due to uncertainties in their level of engagement and responding, two companies were willing to engage in an in-depth interview. Thus, we asked for a contact person on management level with broad knowledge in the investment process to be able to respond to the phenomena and its external mechanisms under study. However, this gave us the opportunity to dig deeper into each case and analyze the findings more in-depth.

A population is identified as a group of people and a sample is a subset of the population (Collis & Hussey 2014). In this research there was one sample used with two participants. The chosen participants were both experienced in the context of Sweden and pioneers in the impact investing field and had an important role for the development of their respective business. Their experience was a crucial factor when selecting the sample due to the need of empirical findings. Therefore, this research focuses on a judgmental sampling method, since the participants were selected by the researchers and all decisions were made prior to the interviews (Collis & Hussey 2014).

The collection of relevant data is a crucial step when finding the answer of the research question. Another crucial step is to identify what type of data that is required, primary or secondary. According to (Collis & Hussey, 2014) primary data are data collected for the specific research project, such as interviews in this case. Secondary data on the other hand are data collected from an existing source, such as main articles and journals in the field of impact investing. This was used to strengthen the empirical findings. Moreover, to achieve the purpose of the research it is essential to choose the right data collection technique. In this research, we focused on primary data through semi-structured interviews, since it allows further elaborations and new ideas on questions with open answers (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

28

3.2.2 Interviews

3.2.2.1 Interview Questions

The purpose of the interviews was to examine the connection between financial return and social impact since the respondents practice particular investment strategies in their work environment. Moreover, the authors aimed to discover what factors that could result in a specific decision, action and outcome, to successfully manage trade-offs. The professional position of the interview participants varied between founders and managers; thus, the interview questions were adjusted for each participant to gain relevance and richness in the information given from each interview. The change in the format was done not only to ensure the most effective answers for the study, but also to respect the time restrictions each respondent was able to deliver. Additionally, the interviews were held in Swedish, which was the mother language of each participant, which also created the best possible space for them to express themselves without being limited to comfort or language hinders.

Initially, we asked for the respondents understanding of the specific impact they aim to achieve with their business, and how it is ensured. Questions about their companies and general work environment were asked and complemented with personal experience regarding their practice of dealing with conflicting logics of financial return and impact return in conducting their business. During the actual interviews, attention was directed towards uncovering the incentives behind their perception of the trade-off, under which circumstances, and whether their activities were connected to the theories used in existing literature.

The structure of the interviews consisted of introduction questions, personal motivations, experience of certain activities and scenario questions to capture the respondents’ awareness of the trade-off taking place. The questions that required answers connected to the trade-off were asked later on in order to avoid the respondent being directed to the critical approach of the phenomena under study.

29

Table 3. Overview of interviews.

In light of the outbreak of COVID-19, we made an united decision to conduct interviews over the telephone instead of face-to-face as planned.

3.2.2.2 Semi-structured Interviews

In order to explore the perceptions of the respondents’ in the most deeply way possible, the interviews were semi-structured. This structure is appropriate when most of the questions are open-ended and requires further elaboration or clarification, thus allowing space for new concerns and ideas to be brought up during the interview session. The aim of an interpretivist research is to understand the interviewees, their underlying motives, values and motivations for acting in a certain way. In this case, when it comes to the linkage between financial returns and social impact.

The interviews were recorded, especially to ensure that new topics brought up with relevance of the study were transcribed if introduced during the proceedings of the interviews. In order to gain in-depth answers, we asked for further elaboration when needed. In order to obtain more in-depth answers, probes were used to follow-up on topics brought up when the answers given were vague or opened up for more details.

30

3.2.3 Credibility

When conducting qualitative research, it is essential to ensure credibility in order to secure trustworthiness of the data collected, selected, and analyzed in the research (Shenton, 2004). To increase the possibility to analyze findings, an investigator triangulation approach was used as a technique that involves the use of multiple methods and various sources of data. This is a method used to decrease research bias, since it integrates different perspectives to interpret findings in a study while increasing credibility (Collis & Hussey, 2014). For the data analysis and the written arguments, the aim is to be transparent and make it understandable to increase dependability of the study. Although it is difficult to stay completely unbiased, the authors aim to adopt a beginner’s mindset to increase confirmability.

3.2.4 Validity of Fieldwork

“Validity is the extent to which the research findings accurately reflect the phenomena under study.” (Collis & Hussey 2014).

To ensure the data quality and validity of the case study, construct validity, internal validity, and external validity should be considered (Yin, 2014). However, internal validity will not be applied in this study since it is not applicable to exploratory case studies.

First of all, construct validity is about determining if the practical measures are appropriate for the certain case study (Yin 2014). It is suggested to use multiple sources of evidence to increase the validity of the research. In this study the authors used a triangulation approach where multiple methods and various sources of data were used to reach a more valid result. The study demonstrates and increases the construct validity by using both primary and secondary data in the data collection.

Secondly, the external validity refers to generalization and identifies if the study's findings can be generalized in addition to the actual case study (Yin 2014). In this study,

31

the research question begins with “how”, which enables the authors to generalize the findings and increase the external validity.

3.2.5 Reliability of Fieldwork

“Reliability refers to the absence of differences in the results if the research were repeated.” (Collis & Hussey 2014).

This generates an opportunity for other researchers to study the same case with the same method. However, this is not the same as replicating, which would include replicating the results of one case by doing another case study (Yin, 2014). The authors in this study have been taking reliability into account, mainly to reduce errors and bias in the study. The procedures in this study are addressed in the methodology section thoroughly, which enables other researchers to identify if the study is reliable and to see if they can generate the same result by using the same case and procedure.

A possible threat to the validity and reliability of the study is whether the right people were interviewed to achieve the purpose of the study. However, in order to reach our purpose, the authors interviewed experienced actors in the industry of impact investing, and thus increased the reliability and validity in this study.

3.3 Data Analysis

The purpose of conducting a thematic analysis is to identify and examine recurring themes emerging from the empirical findings, which is an interpretivist method used in the process of analyzing qualitative data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The aim of this study is to observe empirical truth, develop patterns, and contribute with valuable knowledge to existing research as it allows for a different focus compared to prior studies. Therefore, the thematic analysis conducted in this research is inductive since the research moves from empirical observation to theory (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Given the qualitative nature of the research, the authors selected this method over content analysis, discourse

32

analysis, and grounded theory, based on its flexibility to develop themes from the data (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

After the data was collected, the first step was to transcribe the interviews to provide the authors a holistic view on how the data can be approached and facilitated in the analysis. In the procedure of listening and reading the data set, specific observations and recurring patterns were noted and highlighted in the margin. As these were summarized in the form of codes, they were given particular labels. The following themes emerged from the procedure: Impact, Values, and Impact Management, followed by sub-themes such as long-term view, business model, and sector specialization.

The general principles of coding were followed in this research, where the codes should be exhaustive; cover the identified areas of the study, and mutually exclusive; must refer to different features of the data. Ultimately, the codes must be applied consistently; where categories are identified from listing codes (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

The interpretivist approach allows the researchers’ own perception of the data and the use of one method is more likely to increase errors in the study (Collis & Hussey, 2014). To reduce subjectivity, two of the authors reviewed the data individually to interpret the data set and compare the findings. This triangulation of data is an approach referred to as analyst triangulation, where more than one observer carries out the data analysis separately (Patton, 1999).

The themes that emerged were analyzed in two ways, internally and externally, to facilitate the data analysis process and provide findings that are crucial in order to answer the research question. Firstly, the internal analysis included an analysis of each case, where the respondent’s experiences in the company were analyzed. This analysis followed an interpretivist study, which allowed explanation of the data based on the authors’ interpretations and understandings (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Secondly, the external analysis procedure was conducted to discover common themes and patterns found in the two cases (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

33

The empirical data is based on a narrative inquiry, which is used to understand and describe the human behavior found in the interview findings. In the narrative context, this enables the authors to share different meanings of stories from specific events and times that occur in social context (Bold, 2012).

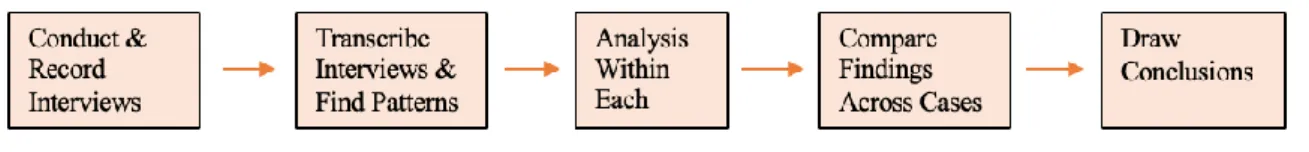

The authors have derived a model to connect different processes with the purpose of analyzing data:

Figure 3. Process of data analysis.

3.4 Ethical Considerations

This study investigates a research topic that is relevant but could also be considered a sensitive topic to discuss for companies in the industry. Therefore, it is important to respect the company's values regardless of the outcome of the study. The two participating companies are presented with respect and honesty in this study. Prior to the interviews the authors asked whether the representatives of the respective companies wanted to be recorded and offer the option to be anonymous. If the participants preferred to stay anonymous, they were informed about the possibility to not being mentioned by name. Moreover, to be as transparent as possible, the authors informed the participants about the research, why it is conducted, and how it is intended to be conducted by sending out a pre-questionnaire (see Appendix 1). It was also vital to ensure that the interviews went as anticipated, and in order to do that the authors had a strong focus on transparency, trust and communication. This generated well-executed interviews where the confidentiality was clearly communicated. Moreover, impartiality is another important ethical consideration and since the study is financially independent, it confirms that there is no partiality.

34

4. Empirical Findings

This section presents the overall findings and experiences of the respondents. The cases are divided into Impact Invest and Leksell Social Ventures, presented in separate sections. The empirical findings firstly present the companies’ impact journey and follow the same structure of recurring themes and themes, labelled as impact with the sub-theme long-term view, values, impact management with the sub-sub-themes business model and sector specialization.

Table 4. Overview of Cases.

4.1 Impact Invest Scandinavia

The first interview is held with the CEO of Impact Invest Scandinavia, Ruth, who founded a network for business angels and private investors in 2012 to raise capital for social entrepreneurs. When starting the business, the term of impact investing was not defined, and the market was undeveloped in Sweden. From her office in London, she dives into the story of how she brought the concept from other countries with the aim to increase funding for social companies that could deliver social purposes. In parallel to this she worked to contribute to national standards on impact investing. A short while into the interview we get a sense about her passion for sustainability, as she talks about the organization’s devotion to spread awareness of impact investing and support social

35

investments, and their huge influence in helping unsevered and neglected groups in society.

She keeps referring to this eight-year period in the organization as a bumpy road, as sustainability awareness and interest to invest in social purposes among investors and companies have varied greatly. Ruth is a long-committed social investor and supporter of social innovations, and her way of describing how she manages a business that connects and advises actors in the field gives the authors a feeling of strong dedication. Her way of describing the market for social investing and expressing her thoughts guides the authors through her reflections, and it seems evident for her to give honest responses to our questions. She invites us to imagine both ups and downs with running a social business, and through her direct yet thoughtful answers that often refers to the organization’s purpose-driven work, they show how knowledgeable she is in the field and her genuine interest in global health. When asked about the organization’s ultimate vision, she answers without hesitation:

“In every type of financing and capital, regardless of what kind of investor you are, there must be a dimension of money and its value, that money can make more use than

it does today.” (Ruth)

4.1.1 The Impact Journey

With regards to the various activities that Impact Invest is engaged in, Ruth was introduced to the broad spectrum of social investing in the early 2000’s. When asked about her interest in social innovation, she tells about her background as a business director for a global company where she questioned what she wanted to dedicate her life to. Back in that time, she saw the downside of running a business that is driven by economic principles that do not account for other consequences. Ruth tells a story about a business that values financial figures and states:

“First, you satisfy the owner and the board, so their salary is good enough, and then it is a bonus if the employees feel pleased with their work. When the focus is to make

36

practices more efficient and cut down costs, the end user and produced benefit always get a secondary value.” (Ruth)

The gap between her own values and the company’s value creation evoked an interest in maximizing social value instead of economic value. For about eight years, she has worked with educating the market and showing investors and companies that there is more to business than maximizing profits and shareholder value. She laughs and says:

“I learned a lot in the business world, especially how to run a company and how to stimulate innovation, but I realized that I wanted to maximize impact instead of

economic value. Here is where impact investing becomes interesting.” (Ruth)

Impact Invest has ever since focused on delivering social value, which has been central in how they have shaped the intermediary and advisory platform for both investors and entrepreneurs. Initially, the network was introduced as a practical effort to gather companies and social entrepreneurs who had difficulties in raising capital through the traditional venture capital system. Today, she believes that the concept of impact investing is niched and how you define the market will become less relevant in the future. Over time, values beyond stock values would become more natural when other aspects are included in the validation of a company.

4.1.2 Impact

In the interview, Ruth speaks about how impact can be defined in many different ways and from her own perspective she defines Impact Invest’s organizational impact as:

“The main task is to increase resources and financing for companies that can show well-defined and measurable social or environmental impact.” (Ruth)

According to Ruth, this definition can be interpreted in different ways, but primarily it is about supporting companies who are willing to generate a social or environmental impact. Furthermore, it was clearly observed that Ruth has a vision that there should be a

37

dimension of money and how it can generate impact, no matter what type of investor you are.

Ruth speaks about her passion for social good and the importance of creating an impact by supporting entrepreneurs and companies that are driven by social purposes. As authors we observe that Ruth has a desire to generate a genuine social impact, as it is a personal financial loss for her to run a social business. Moreover, Ruth highlights the importance of being truthful to yourself, your business, and especially to the society by saying:

“Above all, it is about being method-led and evidence-based, not just saying “we are doing something good.” (Ruth)

4.1.2.1 Long-term view

When asked about how Impact Invest reason about the tension between achieving both social and financial returns, Ruth states that she believes that trade-off dilemma is central in impact investment. She tells a story about how she experiences that trade-offs affects decision making:

“Yes, that is number one, all private actors and venture capitalists essentially want a strong benefit financially. In impact investing as a field you see another side, where you

have to invest capital based on what impact you want to scale up.” (Ruth)

Ruth argues that the success of the financial return depends on the scaling and challenge to solve the social problem. The manager says that in most cases, the more difficult the societal problem is that you are trying to solve, the more likely that the financial return will take longer time. She elaborates by saying:

“By proving how you can impact clients' lives, it then shows if it is possible to create an economic model that makes it possible to make x-amount of money.” (Ruth)

38

Ruth tells us a story about a new initiative they were working on, and she describes it as a handbook for investors that are curious to learn more about social innovation and impact investing. With regards to the idea of the handbook, Ruth mentions that there is less available guidance for investors compared to social entrepreneurs. Referring to investors that reach out for Impact Invest’s advice on whether to invest in a business or not, she often receives the question about how to gain financial returns. She states that the topic is frequently discussed since investors are risk averse. Ruth becomes silent for a while and says:

“When it comes to investments and capital, you are very cautious about financial reporting and to follow results. Although, when investors answer questions regarding

the impact effect of the investment, the answers are usually very vague.” (Ruth)

Ruth continues by saying that many pioneers in Europe have the mindset of just making money by doing something good, meaning that the effect or social outcome of their investment is less important. Additionally, Ruth highlights that her business aims to foster the long-term mindset among investors by leaving them with words for thought:

“You show that you can earn money on this product or service, but how do you know if the social impact is well received.” (Ruth)

4.1.3 Values

Ruth experiences that another question that her organization often receives is; how to achieve both impact and financial performance. Based on her knowledge in the field, she believes that trade-offs emerge, particularly between impact and financial performance, and tells how this is managed by Impact Invest through measurement of the impact result. Although the end user and the impact objective are central in their proposed investment strategies, she confirms that there are usually stakeholders involved with different interests.