Follow generational

footsteps, or minimize

future footprint?

Exploring the motives behind Gen Z’s meat consumption and the

implications on the marketing of meat substitutes

BACHELOR’S DEGREE PROJECT THESIS WITHIN: Business administration NUMBER OF CREDITS:15hp PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Marketing Management

AUTHOR: Nora Berggren and Sandra Pöder JÖNKÖPING May 2021

Bachelor’s degree Project in Business Administration

Title: Follow generational footsteps, or minimize future footprint? Authors: N. Berggren and S. Pöder

Tutor: Jasna Pocek Date: 2021-05-22

Key terms: Gen Z, Sustainable consumption, Consumer behavior, Gender differences,

Stereotypes, Marketing

Abstract

Background: The environmental changes leave the younger generation (Gen Z) to worry

about their future, which means implementing changes in their consumption behavior. With global meat consumption drastically increasing, Gen Z has the potential to frame their food consumption patterns for the future. Existing research lacks an understanding of the young consumer's motives for their meat consumption and how marketing can reach the young consumers.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to explore the motives of Gen Z's sustainable

consumption, and more precisely, meat consumption, and what implications their perceptions can have on the marketing of meat substitutes.

Method: This is an exploratory qualitative study, where sixteen semi-structured, in-depth

interviews of participants from Gen Z were held and analyzed inductively. The collected data was analyzed through the Gioia method to find patterns and further develop a theory.

Conclusion: The empirical findings suggest that awareness is the key driver for women of

Gen Z to change their consumption patterns. However, the same awareness is not affecting the male participants to the same extent. Moreover, the findings suggest that the best

approach to reach the young consumers is through digital channels and through neutralizing the concept of avoiding meat. This study contributes to research regarding the consumption patterns of Gen Z and provides insight into a crucial segment of the modern market.

Acknowledgements

Before we present our research, we want to show appreciation to those who made it possible. The support provided by external parties is what made it possible for us as authors to finish our thesis in an enjoyable and efficient manner.

First and foremost, we want to showcase our deepest appreciation towards Jasna Pocek for her continuous support and feedback as our tutor. The tutoring provided by Jasna made it possible for us to develop our thesis efficiently and has helped us realize the potential of both ourselves as authors and our research.

Moreover, we want to send out our gratitude to the sample used in this study. The participants in the interviews contributed with both their experiences and time, making it possible for us to continue our research with relevant findings.

Also, we want to send thank you to all the people who was appointed the role of our

opponents during the continuous seminars, which has helped us to develop and improve the content of our research.

_________________________ ___________________________ Nora Berggren Sandra Pöder

Table of contents

1. INTRODUCTION ... 7 1.1BACKGROUND ... 7 1.2PROBLEM ... 8 1.3PURPOSE ... 9 1.4RESEARCH QUESTION ... 9 1.5DELIMITATIONS ... 10 2. FRAME OF REFERENCE ... 10 2.1METHOD... 102.2CONSUMER BEHAVIOR AND MOTIVES... 11

2.2.1 Gender based consumerism ... 12

2.2.2 Meat consumption ... 13

2.3SUSTAINABLE CONSUMPTION ... 14

2.3.1 Sustainable food consumption ... 15

2.4GENERATION Z ... 18

2.5MARKETING ... 19

2.5.1 Gender roles and marketing ... 19

2.5.2 Marketing towards Gen Z ... 19

2.5.3 Marketing meat substitutes ... 20

2.6GAPS IDENTIFIED IN PREVIOUS LITERATURE ... 20

3. METHODOLOGY AND METHOD ... 21

3.1METHODOLOGY ... 21 3.1.1 Research philosophy ... 21 3.1.2 Research approach ... 22 3.1.3 Research design ... 23 3.2METHOD... 24 3.2.1 Primary data ... 24 3.2.2 Sampling approach ... 24 3.2.3 Semi-structured interviews ... 26 3.2.4 Interview questions ... 27 3.2.5 Data analysis... 27 3.3ETHICS ... 28

3.3.1 Anonymity and confidentiality ... 28

3.3.2 Credibility ... 28 3.3.3 Transferability ... 29 3.3.4 Dependability ... 30 3.3.5 Confirmability ... 30 4. FINDINGS ... 31 4.1AWARENESS ... 32 4.1.1 Impact... 32 4.1.2 Education ... 33 4.1.3 Health ... 33 4.2CONVENIENCE ... 34 4.2.1 Price ... 35

4.2.2 Habits ... 35 4.3SOCIETAL NORMS... 36 4.3.1 Gender norms ... 36 4.3.2 Upbringing ... 37 4.3.3 Stereotypes ... 38 4.3.4 Role models ... 39

4.4PREFERENCES AND SUGGESTIONS ... 40

4.4.1 Marketing ... 40

4.4.2 Products and placement ... 42

5. ANALYSIS ... 43 6. CONCLUSION ... 49 7. DISCUSSION ... 50 7.1CONTRIBUTIONS ... 50 7.2PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS ... 51 7.3LIMITATIONS ... 51 7.4FUTURE RESEARCH ... 52 8. REFERENCE LIST... 53 7. APPENDICES ... 66

7.1APPENDIX 1:INTERVIEW GDPR CONSENT FORM ... 66

Tables

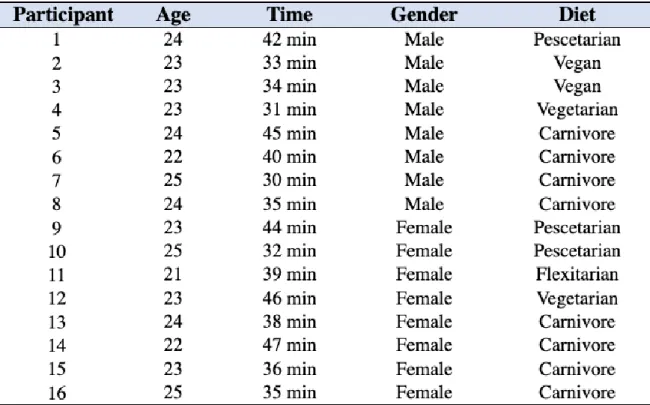

Table 1: Data breakdown ... 25

Figures

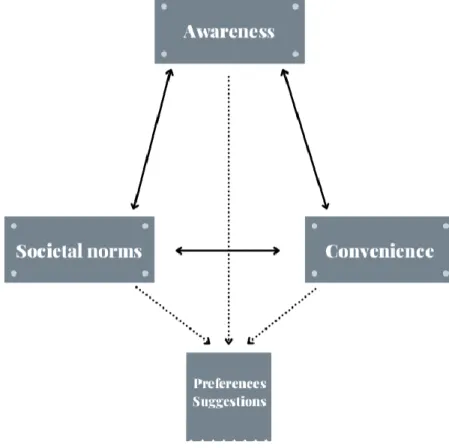

Figure 1. Coding process ... 31 Figure 2. Relationship between the aggregate dimensions ... 48

1. Introduction

This chapter contains a background to the research and introduces the increased awareness of environmental changes where generation Z's food consumption is noteworthy for the future. Furthermore, the problem and purpose are presented along with the two identified research questions to carry out the study. Lastly, the delimitations of the study are stated.

1.1 Background

The environmental changes are ever so present in today's society, leaving the younger generation, Generation Z, to worry about their future, and implementing changes in the consumption behavior (Büttner and Grübler, 1995). With Gen Z being a key stakeholder in the threatened future, the following study will analyze the members of the generation and their attitudes and motives towards sustainable consumption, more specifically in terms of food and meat. Moving forward in the research, the authors have chosen to identify the timespan of Gen Z as people born between 1995-2015 with support from previous researchers, including Priporas et al. (2017) and Özkan (2017).

Kymäläinen et al. (2021) state that generation Z is noteworthy for the future as they have the potential to frame their food consumption patterns. However, researchers disagree on how willing the generation is to consume greener goods, which highlights the relevance for further investigation into the generation’s perceptions on sustainability and dietary choices (Bulut et al., 2017; Kymäläinen et al., 2021; Stubbs et al., 2018).

The population has grown dramatically in the past years, and consequently, global meat consumption has nearly doubled in the last 50 years (Stubbs et al., 2018). According to Funk et al. (2020), beef production is one of the highest culprits of greenhouse emissions and reducing the consumption of meat could reduce the emissions substantially. Moreover, Funk et al. (2020) discuss the fact that a reduction in meat consumption is not only good for the environment but also for an individual's health, which further highlights the relevance of how Gen Z consume meat.

The negative aspects of meat consumption have led more people to start considering a vegetarian lifestyle, and in 2016, 13% of consumers in Europe avoided beef and red meat (Statista, 2016). Segiova-Siapaco and Sabaté (2018) describe some common motives to adopt a plant-based diet as being lifestyle and health, ethical and religious beliefs, and in recent

years, social and environmental concerns. Regarding the latter, the authors further connect the increasing social and environmental concerns as being a driver for plant-based diets, as the production of plant-based food requires far fewer natural resources compared to regular meat (Segiova-Siapaco & Sabaté, 2018).

In relation to a decreased meat consumption, Rosenfield (2020) informs that women are more likely to opt for a plant-based diet, compared to men. The same author further describes that meat has a high association with masculine identity. According to Grau and Zotos (2016), the difference between female and male attitudes and behaviors originates from a long history of gender stereotypes where marketing has, for a long time, contributed by portraying men and women in stereotypical ways.

How Gen Z consumes meat will be analyzed in the context of Sweden, and the interest in the demographic comes from the country being regarded as a leading nation in social

responsibility questions, along with a lack of analysis on how the generation of the future will carry on the legacy (Naukowe et al., 2013).

1.2 Problem

Mertens et al. (2021) discuss how individual behavior and attitudes are crucial aspects to change and aid the environment, as human actions are closely related to pollution and environmental decay. Even though meat consumption is a highly discussed topic in relation to the climate crisis, it is evident that habits regarding food are not easily changed

(Kymäläinen et al., 2021; Segiova-Siapaco & Sabaté, 2018; Stubbs et al., 2018). Still, the existing literature agrees that more sustainable consumption is a must to make a change for the better (Mertens et al., 2021; Funk et al., 2020; Rosenfield, 2020). There are several different areas of sustainable consumption that could benefit from further analysis and better understanding, but as Rosenfield (2020) highlights, overconsumption of meat affects the environment substantially and continually emphasizes that researchers need a better understanding of why individuals choose a vegetarian diet.

The issue at hand is that Generation Z is still to be investigated in terms of their food consumption, as it is a young generation but still has such an impact on the future, both in terms of the environment and how businesses are run (Kymäläinen et al., 2021). Hence, marketers need further exploration into what drives the meat consumption of meat to be able

to reach out to the segment with substitutes in an efficient manner (Djafarova & Bowes, 2021; Williams & Page, 2011).

1.3 Purpose

This research strives to gain a more in-depth understanding of the Swedish members of Gen Z and their perceptions regarding sustainability and meat consumption. Moreover, due to previous research making it evident that there are clear gender differences in dietary choices, the study will investigate how these prejudices and stereotypes are considered by Gen Z (Brough et al., 2016; Pinna, 2019). Hence, what follows is an exploratory study that aims to find a correlation between consumer's meat consumption and their perception of

sustainability issues, to further investigate how the segment of Gen Z can be reached

efficiently by marketers, all while exploring if there are any differences between the genders.

With the help of existing literature, the researchers will build up semi-structured interviews to gain the right information (Collis and Hussey, 2014). The research will undertake an

inductive approach as the focus will lay on observing consumer´s thoughts and feelings, and later find patterns and develop a theory that will help to provide suggestions for future research.

Furthermore, the study is done completely from a consumer's perspective, as the focus is to analyze their behavior and motives and not that of businesses. The following research wishes to understand how consumers perceive things and what motivates them to opt for plant-based options instead of meat, so that the marketing of substitutes can be done as efficiently as possible to overcome gender biases and target the young consumer segment of Gen Z.

1.4 Research question

Having a background of the topic, combined with the purpose of this study, it is possible to formulate the research questions. This study aims to gain an in-depth understanding of

consumer´s behavior and attitudes towards sustainable consumption. The research is targeting generation Z consumers and compares stereotypes between genders and meat consumption. To make the study feasible, the following research questions have been formulated:

Q1: What motives drive the meat consumption of Gen Z?

1.5 Delimitations

Delimitations of this study have been made to restrict the scope of research. As the study has identified Generation Z as their key stakeholders, the research is delimited to individuals born between 1995-2015. Generation Z is a new and young generation, which means that there exists limited research about them in terms of sustainability and meat consumption. Moreover, the study is delimited to participants living in Sweden. Another substantial

limitation to have in mind is that this research investigates consumer behavior. A consumer's perception can vary in many ways, such as values, beliefs, and norms (Jansson et al., 2010). It is, therefore, significant to keep in mind that the results only reflect a small portion of

consumer's thoughts and feelings within this broad subject.

2. Frame of reference

In this chapter, previous research is presented to form the body of the research. The chapter begins with a method describing how researchers constructed the frame of reference. The chapter further entails important explanations of sustainable consumer behavior, gender-based consumerism, and Generation Z. The chapter ends with the identified gaps from existing research.

2.1 Method

The following section will analyze previous research within relevant areas applicable to this thesis. To make sure that the basis of this thesis was valid, previous research was used as a tool for defining a gap that could be further examined to contribute to the already existing information. Relevant articles were found through Google Scholar and Primo based on the following keywords: 'Consumer behavior', 'Sustainable consumption', 'Meat consumption, 'Generation Z', 'Gender-based consumption' and 'Gender stereotypes in advertising' and later compared to the ABS-list to examine the impact factor.

With the desire for a structured literature review, an excel file was developed stating key-concepts of the articles, year published, ABS-list ranking, future research defined, and personal comments from the authors of this thesis. To keep the research of the following thesis relevant, the publishing year of the primary articles used ranges from the year 2021 to 2017 and maintain a relevant impact factor on the ABS-list. To have a relevant base, 15 articles all found in journals with a high impact factor ranking were deemed the most relevant

to begin with and were further analyzed and summarized to compare the themes, which were identified throughout the main articles as: 'Environmental crisis', 'Sustainable consumption', 'Generation Z / Future generations', 'Stereotypes and motives connected to vegetarian diets', 'Gender differences', 'Food consumption' and 'Consumer behavior'. The mentioned themes being found throughout the selected articles further promotes the relevance of usage. As the research went on, a large number of articles were further incorporated from the ABS list to ensure validity and thorough understanding on the subjects, a concept which can be identified as snowballing (Wohlin, 2014).

Additionally, sources found on Google Scholar and Primo that are not listed on the ABS-list, and articles published before 2017, have been used as complementary sources if deemed useful and credible, especially in terms of the topic of food and meat consumption. The mentioned articles, along with an extensive amount of ABS articles, means that the literature review has been based on 65 different sources, to ensure a relevant and credible interpretation of previous findings.

2.2 Consumer behavior and motives

According to Ajzen (1991), explaining human behavior is a complex task. Therefore, several authors have used the theory of planned behavior to understand consumer decision-making (Ajzen, 1991, 2015; Lee et al., 2015; Vermeri & Verbeke, 2008). The theory suggests that the consumer's intentions are what constitutes the behavior in question (Ajzen, 2015).

Furthermore, these intentions are determined by three kinds of beliefs and considerations (Ajzen, 2015). Ajzen (2015) identifies the first one as behavioral belief, and it refers to the perceived consequences of carrying out the behavior, either positive or negative. The second consideration is the normative beliefs, which include the perceived social pressure and expectations and the behaviors concerning performing the behavior (Ajzen, 2015). The same author identifies the third consideration as control beliefs and concerns the perceived

presence of elements that can influence an individual's ability to perform the behavior. Ajzen (2015) notifies that it is of high importance to recognize that the theory does not presume rationality from the part of the decision-maker, which means that unconscious biases, self-serving motives, and paranoid tendencies, etc., are poorly informed. Furthermore, the same author states that with recurrence, behavior becomes habitual and lacking conscious

Lee et al. (2015) argue that the theory of planned behavior is one of the most valid theories in predicting consumers' behaviors, especially when it comes to their food selecting behavior. Additionally, Vermeri and Verbeke (2008) suggest that self-related variables should be added when exploring consumers' food choices since personal or contextual aspects can inhibit positive attitudes from being articulated in action. Moreover, Vermeri and Verbeke (2008) identify perceived availability and perceived consumer effectiveness as vital factors in behavioral control. Perceived availability refers to if consumers feel like they can effortlessly obtain a product, and perceived consumer effectiveness refers to how consumers believe that their efforts can provide a solution to a dilemma (Vermeri & Verbeke, 2008). Lastly, Jansson et al. (2010) explain that consumer attitudes are context-specific and associate consumption-level attitudes and behaviors to personal values.

2.2.1 Gender based consumerism

The difference between gender has for a long time been explained by the biological differences (Costa Pinto et al., 2014; Fischer & Arnold, 1986; Hyde, 2014; Pinna, 2019). Moreover, numerous authors express that psychological differences are substantial as well (e.g., Carter, 2014; Fischer & Arnold, 1986; Hyde, 2014). It is necessary to understand and research gender similarities and differences as it leads to stereotypes and influences people's behavior (Hyde, 2014). Fischer and Arnold (1986) recognize gender identity and gender role attitudes as two main factors to distinguish the differences in behavior. Gender identity refers to traits associated with masculinity and femininity, which are commonly used to illustrate psychological differences. However, Fischer and Arnold (1986) states that research shows that both men and women possess masculine and feminine traits, although to different degrees. Gender role attitudes refer to the perceptions about the roles applicable to men and women (Fischer and Arnold, 1986). Moreover, Pinna (2019) and Carter (2014) agree with previously stated facts by explaining gender identity as to which degree a person identifies themselves with feminine or masculine traits. Furthermore, Pinna (2019) describes that different personality traits are linked with consumer behavior.

Various authors agree that there is a difference between men's and women's attitudes towards sustainable consumption (e.g., Brough et al., 2016; Bulut et al., 2017; Pinna, 2019; Sreen et al., 2018). Bulut et al. (2017) recognize that women express more superior pro-environmental beliefs than men. Hence, women relate more closely to a higher level of sustainable

about societal issues than men. Sreen et al. (2018) and Vicente-Molina et al. (2018) reinforces the statements describing that women are more concerned about environmental problems. Furthermore, the authors attempt to explain why the differences have occurred and connect them to previously described gender-based theories. Similarly, Pinna (2019)

identifies gender differences regarding environmental concerns to be theoretically explained in relation to institutional trust, safety concerns, and risk perceptions.

Another suggestion of the difference between gender's sustainable consumption is the concepts of femininity vs. masculinity (Brough et al., 2016; Pinna, 2019). Brough et al. (2016) propose that the gender gap rises from differences in personality traits, where

sustainable consumption is more connected to feminine attributes. Both men and women hold stereotypes against sustainable and ethical concerns, and suggestively, men are more

concerned about their masculine identity (Brough et al., 2016). Therefore, men want to avoid being associated with femininity and sustainable consumption. Pinna (2019) provides similar suggestions by stating that ethical behavior is rooted in gender identity, where sustainable consumption is appeared to be more feminine. Although several authors point out that there exists a difference between men's and women's sustainable consumption, most researchers agree that it is not a factor on its own but rather a part of multiple reasons (Brough et al., 2016; Bulut et al., 2017; Pinna, 2019; Sreen et al., 2018).

2.2.2 Meat consumption

There are several aspects of why a person would choose a vegetarian diet. However, one of the most underlying motivations for a person to avoid meat is found to be gender (De Backer et al., 2020; Dowsett et al., 2018; Funk et al., 2020; Mertens et al., 2021; Modlinska et al., 2021; Kubberød et al., 2002; Rosenfield et al., 2020). Furthermore, De Backer et al. (2021) and Modlinska et al. (2021) state that meat is highly associated with masculinity, and this contradiction is not uncommon in Western culture. For ages, European, Asian, and American men have consumed more meat than women which De Backer et al. (2020) and Modlinska et al. (2021) argues is due to the strong culture, where men are more associated with power, masculinity, and wealth. Mertens et al. (2021) add on these facts by stating that it is rare to adapt to a vegetarian lifestyle in Western countries, and men are the least likely to adapt to it. The strong culture connected between men and meat has led to the preconceptions that "real men eat meat" (De Backer et al., 2020; Dowsett et al., 2018; Funk et al., 2020; Mertens et al., 2021; Modlinska et al., 2021; Kubberød et al., 2002; Rosenfield et al., 2020). De Backer et

al. (2020) explains that men consider it more natural to eat meat because it makes them strong and masculine. Furthermore, various men do not consider a meal complete without meat. Modlinska et al. (2021) aim at explaining how the differences have occurred and notify that a study showed that the differences appear already in early childhood, where girls were more positive to fruits and vegetables, and boys preferred meat, fast food meals, and eggs.

Several other authors recognize the difference between genders and connect it to women being more positive towards healthy and pro-environmental behavior (e.g., Dowsett et al., 2018; Funk et al., 2020; Kubberød et al., 2002; Mertens et al., 2021). For example, Funk et al. (2020) argue that women are more willing to consume healthier food, and it is more feminine to eat smaller and healthier food portions. Additionally, Mertens et al. (2021) recognize the difference between genders in pro-environmental concerns and that women are more likely to avoid eating meat. Dowsett et al. (2018) agree with Mertens et al. (2021) statements by adding that women tend to use indirect strategies for dissonance reduction of animal meat. In contrast, men use more direct approaches, such as human dominance and denial of animal pain (Dowsett et al., 2018).

Some authors state that a long history of meat being associated with real men has led to persistent stereotypes, which makes it harder for men to adapt to vegetarianism (Modlinska et al., 2021; Rosenfield et al., 2020). In contrast, De Backer et al. (2020) imply that the

contradictions may be too stereotypical sometimes and states that it is not applicable for all men. De Backer et al. (2020) continues to explain that an increasing number of men have started to question the male norms and privileges. Furthermore, they want to change the old forms of masculinity. However, Modlinska et al. (2021) still imply that people hold more prejudices against vegetarian men and that they face more resentment in their social groups.

2.3 Sustainable consumption

There are no contradictions in previous research regarding the fact that people are more aware now than ever of how their consumption affects the environment (e.g., Eberhart & Naderer, 2017; Pinna, 2019; Sharma & Jha, 2019; White et al., 2019). Hume (2010) states that borders separating countries are no longer an obstacle for consumption, a contributing factor towards environmental degeneration, which has left sustainable consumption as a development goal conducted by the United Nations (Feil et al., 2020; Sigurdsson et al., 2020; Ülkü & Hsuan, 2017; Valor et al., 2020). For further explanation regarding the impact of

sustainability being a part of the development goals of the UN, the United Nations (2016) put the goals into place with the desire to generate a more sustainable future to protect the planet and the people.

Sustainability, as is, has accumulated an extensive number of definitions by different authors over the years, as discussed by Hume (2010), who went on to further state that there are roughly over 300 different definitions. However, in connection to consumption, it will hereby be defined as obtaining and utilizing resources efficiently, respecting the social and

environmental impact, generating a higher quality of life for current and future generations, a definition provided with support from previous findings (e.g., Govindan, 2018; Sharma & Jha, 2017; Ülkü & Hsuan, 2017; White et al., 2019). Govindan (2018) further explains that sustainable consumption is not necessarily equivalent to less consumption but rather an approach to acting smarter when buying.

The heightened realization of how everyday consumerism affects the environment has led to increased pressure on adapting a more sustainable mindset, as previously touched upon. However, Eberhart and Naderer (2017) argue that knowledge has yet to transfer into action, which is enforced by Pinna (2017) who states that daily sustainable practices are limited, and the market for ethical products significantly smaller than that of ‘ordinary’ products. The concept of awareness not generating action is further supported by author Hume (2010), who expresses the concern that the lack of a clear definition for the concept of sustainability is a factor resulting in trouble in terms of sustainable practices. Vermeir et al. (2020) further discuss the fact that the lack of action can be a cause of denial, or lack of understanding of the threat that is put on the environment based on consumption habits.

2.3.1 Sustainable food consumption

Feil et al. (2020) state food consumption as one of the main issues concerning sustainable development, while Funk et al. (2020) further highlights livestock production and

consumption as a responsible actor in all sorts of activities linked to climate change, such as pollution, deforestation, and loss of biodiversity through increased greenhouse emissions. To be more specific, Valor et al. (2020) provides information stating that households'

consumption patterns of food are what causes 60 % of greenhouse gas emissions globally. The increasing emissions in connection to food come as no surprise when considering that Staniškis (2012) stated that the consumption of food is 30% higher than the regeneration

capacity of the planet, and since then, the world population has continued to grow (Govindan, 2018; Reisch, 2013).

Naturally, the increasing environmental impact of food production and consumption leaves a responsibility on consumers to change one's behavior in terms of food choices (Feil et al., 2020; Funk et al., 2020). The concept of sustainable consumption has previously been defined with help from previous research, and it is closely related to the definition that Valor et al. (2020) provides for sustainable food consumption, which focuses on meeting basic needs using the minimum number of natural resources and emissions so that the quality of life for future generations does not diminish.

A more sustainable approach to food consumption is not an overnight mission since it requires changes in consumer behavior and lifestyles due to how embedded food is in the social context (Govindan, 2018; Okumus et al., 2021; Funk et al., 2020).

However, a good place to start is transparency in the food market, where customers get a chance to distinguish products based on sustainable features without extra effort (Feil et al., 2020; Reisch et al., 2013).

An overlapping theme present in previous research regarding a journey towards sustainable food consumption is the impact of reducing the production and intake of red meat (Funk et al., 2020; Hoek et al., 2017; Reisch et al., 2013). Funk et al. (2020) further state that in Europe, the greenhouse emissions connected to beef production are the highest per kg of all foods produced, yet there is resistance towards the substitution of meat products. The rejection of reducing the amount of meat in one's diet despite the impact it leaves on the environment, and animals, are further discussed by several authors, who mainly connect it to the stereotypes revolving around vegetarians, the consumers' upbringing and heavily

embedded habits formed by social norms (Cheah et al., 2020; Feil et al., 2020; Funk et al., 2020; Okumus et al., 2021).

2.3.1.1 Vegetarianism

As discussed, sustainable consumption is often connected to a decrease in how much meat is consumed (Reisch et al., 2013). Hence, discussing the topic of a diet excluding meat is highly relevant (Hoek et al., 2017). The concept of vegetarianism is not unfamiliar in history, and it keeps constantly evolving (Corrin & Papadopoulos, 2017). Although different definitions

exist, this research will define a vegetarian as someone who excludes their meat intake

(Bowman, 2020; Corrin & Papadopoulos, 2017; Nezlek & Forestell, 2020; Segovia-Siapco & Sabaté, 2018). Furthermore, more concepts of vegetarianism have arisen in recent years. For example, a Lacto-vegetarian excludes meat and eggs but allows dairy products. In contrast, Ovo-vegetarian allows eggs but excludes dairy and meat products. Additionally, a pescatarian avoids meat but allows seafood. And lastly, a vegan diet excludes all types of animal

products (Bowman, 2020; Corrin & Papadopoulos, 2017; Nezlek & Forestell, 2020).

Most authors agree that only a tiny portion of the world's population adopts a vegetarian diet (Asher & Peters, 2020; Corrin & Papadopoulos, 2017; Nezlek & Forestell, 2020; Segovia-Siapco & Sabaté, 2018). According to Segovia-Segovia-Siapco and Sabaté (2018), India is the leading country in the number of vegetarians, and only 3.3% of the United States population are vegetarian, where slightly more women than men adapt to it.

Corrin and Papadopoulos (2017) inform that no more than 10% of the population in

developed nations are vegetarians. Similarly, Nezlek and Forestell (2020) state that no more than 10% of citizens in Western industrialized countries are vegetarians. Despite the low numbers, Asher and Peters (2020) still state that an increasing number of people in the United States have reduced their meat consumption to some extent in recent years. Additionally, Bowman (2020) explains that the demand for plant-based foods is increasing. The same author further explains that plant-based foods contain sources of dietary fiber, vitamin C, magnesium, and other nutritional vitamins. With the rise of customers wanting more natural, clean, and sustainable food choices, plant-based foods are good alternatives. Plant-based foods are set to continue to grow in demand in the next following years (Bowman, 2020).

There are many reasons for choosing a vegetarian diet discussed by previous research, with the most common underlying factor that appeared in literature are lifestyle and health, ethical beliefs and attitudes, and socio-economical concerns (Bowman, 2020; Nezlek & Forestell, 2020; Segovia-Siapco & Sabaté, 2018). Similarly, Nezlek and Forestell (2020) explain that the most usual reasons for choosing a vegetarian diet in Western countries are concerns about the environment, health, and animals. However, it is significant to remember that these reasons do not exclude each other.

2.4 Generation Z

Southgate (2017) argues that the actual behavior of Gen Z has a limited amount of relevant previous research, mainly due to the young age of the members in the generation up until recently. However, as the age of Gen Z increases, so does the opportunity to go more in-depth on how the members' behavior will affect the future of consumption.

The exact time span of Generation Z is widely discussed, with no precise agreement on what years of birth will establish a belonging in the so-called 'internet generation' (Özkan, 2017). However, with support from previous research, it may be further defined as people who are born between 1995-2015 (Priporas et al., 2017; Özkan, 2017).

Whilst the age-definition of Gen Z may cause scattered interpretations, the technological aspect is a globally accepted in connection to the generation (Grow & Yang, 2018; Southgate, 2017; Šramková & Sirotiaková, 2021; Priporas et al., 2017; Özkan, 2017). Özkan (2017) further argues that it is the constant internet connection from birth that shapes the increasing expectations and altered priorities of Gen Z compared to the previous generation, an

argument further developed by Grow and Yang (2018) as a reason for an increase in consumers who are cynical yet passionate about societal issues. Moreover, Chaney et al. (2017), as well as Kymäläinen et al. (2021), relate the constant connection to why the members of Gen Z are some of the most educated, socially involved and change seeking people.

Additionally, Grow and Yang (2018) adds to the previous authors by stating that the change Gen Z wants to see if connected to society and social issues and that the urge for social change within Gen Z correlates to the desire for a purpose. Gen Z, which Lemy et al. (2021) characterize as a highly environmental conscious one, is the future of the market and will generate new demands on businesses through generational consumption patterns formed through constant access to the internet and historical events (Priporas et al., 2017; Šramková & Sirotiaková, 2021; Özkan, 2017).

In terms of generation Z in relation to general consumption there is room for further

investigation, as the phenomenon is somewhat unexplored. However, what is argued is that the future generation brings their business online, as discussed by Özkan (2017).

Furthermore, Šramková and Sirotiaková (2021) argue that the consumption patterns of Generation Z are changing due to the access of information and education level, an argument

that correlates with Grow and Yang (2018) who further stated that information is what drives the consumption patterns of the generation.

2.5 Marketing

2.5.1 Gender roles and marketing

Gender norms have been a big part of developing advertisements for decades through themes such as colors, cause and gender-stereotyped products, discussed by several authors within marketing (e.g., Antoniou & Akrivos, 2020; Böhmer & Griese, 2020; Nickel et al., 2020). According to Nickel et al. (2020), companies spend a lot of money on gender-based

marketing techniques to adapt the advertisements to biological gender stereotypes, despite the core product being the same. Antoniou and Akrivos (2020) further argue the fact that the gender-stereotyped nature of marketing has a risk of affecting actual aspirations and sense of worth in those who view the advertisements, a statement that Böhmer and Griese (2020) further explore and connect to gender inequality. Nelson & Vilela (2017) examine how marketing and its' gender role biases, such as the caring character of women, could be an underlying factor as to why female viewers respond better to advertisements with a cause, strengthened through correlating arguments from Clark et al. (2019), as well as Jones et al. (2017).

2.5.2 Marketing towards Gen Z

When it comes to marketing, one of the most common segments considered is different age groups, along with other demographic variables (Camilleri, 2017; Chaney et al., 2017; Dolnicar & Grün, 2016). Despite agreeing that age influences consumer features and needs, Chaney et al. (2017) also focus on the one-dimensional aspect of the variable to support the belief that generational segments would be more accurate, as generational targets will develop values from the same historical life events.

Generation Z is the future target for companies, and the nature and experiences of the generation put pressure on the companies to adapt to the new lifestyle (Djafarova & Bowes, 2021; Williams & Page, 2011). Authors agree on the fact that the constant connection of a generation that has never lived without the Internet, as is the case for Gen Z, makes it crucial for companies to consider the consequences of a highly aware audience (e.g., Chaney et al., 2017; Djafarova & Bowes, 2021; Munsch, 2021; Southgate, 2017). Williams and Page (2011)

discussed the then prepubescent Gen Z as liberal, street smart and technologically competent, which alters brand perception and the effectiveness of marketing strategies.

Furthermore, Southgate (2017) describes Gen Z as people with a much lower attention span than previous generations due to the constant exposure to new things, which the author further states as crucial to recognize when marketing towards the age group. With the characteristics of Gen Z in mind, the attention span and constant online connection, Munsch (2021) opens for discussion that the best way to market is through digital channels, preferably humorous and straight to the point.

2.5.3 Marketing meat substitutes

C. Fuentes and M. Fuentes (2017) clearly states the lack of research on meat substitutes in marketing, despite the growing interest in plant-based diets. Furthermore, introducing meat substitutes through marketing is a complex task since the aim is to make it a more natural part of everyday life for consumers (Fuentes & Fuentes, 2017).

Meyer and Bäumer (2020) argue that the complexity of meat substitute marketing can be handled through the concept of social marketing. Social marketing is further explained by Meyer and Bäumer (2020), with support from Brennan and Parker (2014), as a concept of marketing that aims at changing consumer behavior in connection to social causes to aid society and personal well-being. Bogueva et al. (2017) use the success of social marketing in relation to other societal matters, such as decreased tobacco usage, as further validation of why it would be useful to reduce meat consumption. Brennan et al. (2020) connect social marketing to the food industry when it comes to so-called health foods, such as plant-based options, and the authors state that to reach different segments of the market, companies need to adopt a social marketing approach and adjust it to influence change in consumer behavior.

2.6 Gaps identified in previous literature

Generation Z is, as mentioned, still a very young demographic, and there is more than enough room to contribute with further research on the generation (Hume, 2010; Sreen et al., 2018). Hence, while extensive research exists about consumer behavior and motives, a gap can be found concerning Generation Z and how this crucial segment of the future market perceives things (Feil et al., 2020; Hume, 2010).

Furthermore, as stated by authors such as Funk and Siegrist (2020), context matters, and meat consumption specifically related to Swedish consumers have not received an extended

amount of effort in research. Hence, as demographic features can alter the perceptions and attitudes of people, especially towards a sustainable form of food consumption, the Swedish market is deemed a gap in the literature surrounding meat consumption (Bulut et al., 2017; Feil et al., 2020; Okumus et al., 2021).

Additionally, previous research may benefit from the exploration of gender differences, as the statement of the differences is studied, but the reasons why or how the stereotypes are evident in consumers are not (Mertens et al., 2021). Furthermore, once again connected to the desire to explore Gen Z, how the gender differences are prevalent in consumption patterns, still to this day, would suffice from further investigation.

With the presented gaps found based on existing literature, this study will aim to fill them by exploring how Swedish Gen Z'ers perceive sustainability and how they motivate their food consumption while examining if embedded gender-based stereotypes are evident throughout the results.

3. Methodology and method

The following chapter outlines and argues for the chosen method of the study. The chapter starts with research philosophy, approach, and design and further explains the collected data, sampling process, and interviews conducted. The chapter ends with how the analysis proceeded and the ethical considerations of the findings.

3.1 Methodology

3.1.1 Research philosophy

Crossan (2013) explains that a good research project requires consistency between the purpose of the research study, the research questions, the chosen methods, and the personal philosophy of the researcher. The same author further explains that an understanding of the two research philosophies, i.e., positivism and post-positivism, needs to be understood. Positivism adopts a distinct quantitative approach, while post-positivism aims at exploring and describing an in-depth happening from a qualitative perspective (Crossan, 2013). Khan (2014) adds on these facts by stating that a paradigm is a set of assumptions or a framework

that describes how the world is distinguished. The same author also identifies two paradigms, named positivism and interpretivism (also known as post-positivism). A positivist researcher aims at understanding how the world works to be able to control and predict it. An

interpretive philosophy recognizes that the world is subjective, and individuals form their reality (Khan, 2014).

Furthermore, Crossan (2013) describes that post-positivism is more appropriate within the world of modern science and arose when the grounds of positivism were no longer fully defensible. The new philosophy proposes an alternative to reality, as it is not a rigid thing. Instead, it is created by those individuals involved in the research (Crossan, 2013). A post-positivist philosophy is, therefore, more applicable to this study as the aim is to get an in-depth understanding of how consumers perceive and feel towards sustainable consumption and what might influence them.

Crossan (2013) explains that several aspects influence an individual's attitude, such as gender, culture, cultural beliefs, and reality construction. The philosophy recognizes the complicated relationship between the individuals and external structures and accepts that it can exist multiple realities of the truth (Crossan, 2013). The researchers expect that the answers from the interview will be intricate and obscure to apply to one specific actuality. Therefore, the post-positivist philosophy will allow the research to gain a better understanding of the participants and aid the journey towards a desired outcome for the study (Crossan, 2013).

3.1.2 Research approach

Given the post-positivist philosophy of the study, an inductive approach will be applied (Gioia et al., 2013). Inductive research assumes developing a theory based on observations and empirical findings (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Collis and Hussey (2014) further explain that the reasoning is the opposite of deductive, where you move from the general to the particular, while in an inductive case, general conclusions are created from specific instances. Azungah (2018) further explains that findings do not rise from prior models or theories but directly from the analysis of raw data. The goal of the study is to gain an understanding of an individual's thoughts and feelings, and an inductive approach will help to have an open mind and to generate richer answers (Azungah, 2018). The structure will, therefore, be to formulate a research question within the given topic, gather the necessary information to construct an

interview, observe the results gathered, and lastly, make assumptions and suggestions for future research.

3.1.3 Research design

This study is exploratory research as it intends to explore the research questions, rather than offer final solutions to living problems (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The results will help gain a better understanding of the issue, but do not intend to present clear evidence (Collis & Hussey, 2014). To be able to answer the questions of "why" and "how" something has occurred, the chosen approach is a qualitative study (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The same authors further explain that with the help of qualitative data, the researchers will gain an in-depth understanding of the question. Hammarberg et al. (2016) describe that a qualitative method is appropriate when answering questions about perspectives, experience, and meaning. The reason for not choosing a quantitative study is that the results usually reveal factual data, which cannot be applied to this research. Moreover, the qualitative approach leads to interacting with less participants but gives far richer and in-depth answers compared to a quantitative study (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

In alignment with a qualitative approach, the research is inspired by a grounded theory. According to Khan (2014), grounded theory derives from data collection and analysis. The concept is concerned with an inductive approach as its purpose is to generate theory from data. Khan (2014) further mentions that assumptions will thrive from inductive data. The strong connection to an inductive approach and making new assumptions makes it a perfect fit for this study.

According to DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree (2006), interviews are one of the most used strategies for collecting qualitative data. Interviews can be further divided into unstructured, semi-structured, and structured forms. Structured interviews are commonly connected to quantitative data and are therefore not applicable in this case. Instead, the interviews will be semi-structured. The aim is to schedule the desired interviews in advance and prepare open-ended questions, giving space to other discussions that might emerge during the conversation.

In terms of maintaining qualitative rigor, the study will take insights from the Gioia

methodology (Gioia et al., 2012). The approach rises from a well-specified research question and recognizes semi-structured interviews as the heart of the studies. The methodology pays

heavy consideration to the initial interview protocol to ensure that it is focused on the

research question. Moreover, it pays equal consideration to the revision of the protocol as the progress as it may take twists and turns and requires modification. The methodology is an excellent fit for this study as the goal is to get new insights where the consumer´s thoughts and feelings are in focus.

3.2 Method

3.2.1 Primary data

In line with a qualitative study, the researchers prepared to gather data from empirical findings. A total of 16 individuals were chosen to conduct in-depth, semi-structured interviews. The aim was to open up to profound discussions where the participants got the chance to discuss their perceptions of sustainable food consumption and the contradictions between meat and masculinity. The semi-structured interviews, supported by the Gioia et al. (2012) method, allow rich answers while staying in line with the research question.

Moreover, it was expected that the interview questions and discussions were to be adjusted throughout the process as the authors gained experience and realization in how the original questions played out, which further made the choosing a semi-structured method to the data collection relevant (Collins & Hussey, 2014).

3.2.2 Sampling approach

The sample used for the interviews were gathered based on key-characteristics to go with the research question. More specifically, participants were considered based on being members of Gen Z and Swedish citizens who are also living in Sweden full-time, and gender since the research craved an equal number of men and women to generate a relevant result. Due to the fact the interviewed participants needed to share some key-characteristics to provide a relevant result, a non-probability sampling approach was used.

To further specify, quota sampling was the approach chosen, based on the targets sharing some characteristics but still being a relevant representation of the population and since an equal number of interview subjects were used, i.e., the same amount of men and women were interviewed, as well as an equal amount of meat- and non-meat eaters within the genders (Etikan & Bala, 2017). When choosing the quota sampling approach, sampling biases were considered and avoided by not using participants based on easy access (Sharma, 2017).

The specific nature of the research and focus on distinct diets restricted the authors' usage of their close networks. Therefore, an invitation to be interviewed was posted to social media, specifically Instagram, where subjects could volunteer their contribution if their

characteristics matched. In other words, a voluntary sampling approach was implemented within the quotas, securing the relevance of the participants' characteristics and habits to the research (Murairwa, 2015). Furthermore, the research was unmistakably affected by the ongoing pandemic, which is why convenience sampling had to be implemented to some extent, as there was a limited opportunity to venture out and connect with new contacts (Etikan et al., 2016).

The different approaches to sampling mentioned were all used collectively to ensure that, despite the particular circumstances, the authors still based the results on a relevant sample representing the desired population. We conducted sixteen interviews, with eight female and eight male participants, where four of each gender ate meat, and the other four did not, as presented in Table 1: Data breakdown. The sampling approach applied meant that regardless of the number of relevant participants, the recruiting stopped when the pre-decided number of people for each category had been found.

3.2.3 Semi-structured interviews

The interviews followed the guidelines for what is known as semi-structured interviews, which aids the journey towards gathering independent thoughts through open-ended questions with the opportunity for follow up questions (Adams, 2015). Collins and Hussey (2014) describe semi-structured interviews as a way to gain a more in-depth understanding of the fundamental areas of the research, which was deemed highly relevant in relation to this study. To ensure that all the main concerns were brought up throughout the data collection, an interview guide with open-ended questions was developed. The interview guide was based on the research question as well as previous research and was used throughout the process of the interviews while still leaving an opportunity for follow-up questions and altercations if needed.

When the interviews were scheduled individually with the sample, the participants were sent a GDPR consent form to sign, to accept the collection of personal data such as gender and age, see Appendix 1. The consent form is applied to make the interviewed people feel more secure and encourage transparency, further promoted throughout the interviews through anonymity agreements and the right to withdraw from participation if uncomfortable with the process of the data collection.

The research questions required a relatively young sample, as that is exactly what Gen Z is, so the age span of participants was 20 to 25 years old. The sample's age had some

implications on the schedule as there were several different time plans to consider. Hence, the timespan of the interviews was somewhat affected and adapted to individual participants. Consequently, the interviews ranged in length from 30 to 60 minutes, based on time available from the interviewed people's perspective and the thoroughness of the answers given.

The interviews were held mainly over Zoom, with a couple of face-to-face interviews if feasible, all to adjust to the restrictions of Covid-19. Moreover, the interviews were all conducted in Swedish since all parties involved were Swedish inhabitants and citizen due to the context of the research and using the participants' mother tongue came naturally. Hence, the interviews were all translated into English from consensual audio files after the meetings.

3.2.4 Interview questions

The research's focus on the consumers' own experiences and beliefs led to using open-ended questions during the interviews, with some probing follow-up questions to generate further discussion. Combining open questions with follow-up details when needed was a helpful tool to discover relevant and elaborated results. Opting for the semi-structured nature of the interviews, the authors had the opportunity to adjust the questions asked based on who was interviewed at the time. Furthermore, alterations were made to the interview guide between meetings to ensure the data collection was as relevant as possible.

The desire to understand consumer motivations behind dietary choices was the base for the development of interview questions. Furthermore, the general perception of sustainability, stereotypes and marketing from the consumers got intertwined in the interviews. All

questions prepared and all follow-up questions formed during meetings were based on using the results to fill a gap found in previous research that had been previously defined. Hence, the questions had to promote a relevant outcome that could contribute to future research. Appendix 2 provides an overlook of the basic questions asked during the interviews.

3.2.5 Data analysis

To analyze the data truthfully, the Gioia method (2012) was applied. The chosen method is widely used in qualitative data and aims at identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns and themes within data (Gioia et al., 2012).The analysis will help the researchers to understand the underlying thoughts and feelings towards sustainable food consumption. Thus, the researchers followed the given steps of the analysis identified by the Gioia method (2012). The interviews were held in Swedish to make the participants feel more comfortable and provide richer answers. The researchers recorded the interviews and further translated and transcribed them into English.

The researchers started by getting familiar with the data. Second, initial codes were generated throughout the entire data set, also called first order concepts. The researchers started the coding process independently and, thereafter, compared the results with each other. As the codes collected were many, they were further grouped into second order themes. Lastly, the researchers collated the second order themes into aggregate dimensions. As a part of the research strives to understand the difference between females' and males' motives to sustainable food choices, the researchers found it foremost to decide the same aggregate

dimensions for both genders and distinguish the differences, if identified, in each dimension. In the next step, the researchers checked if the aggregate dimensions worked with the coded extracts. Once the dimensions were accepted, they were defined and named, and the

researchers could uncover meaningful assumptions and answers to the research questions.

3.3 Ethics

Morrow (2020) explains that research ethics are involved in respecting research participants and protecting the researchers in all aspects of the research study. Furthermore, Golafshani (2003) states that reliability and validity are relevant terms in a qualitative study. The researchers have decided to work with the following aspects of ethical research: Anonymity and Confidentiality, Credibility, Transferability, Dependability, and Confirmability to ensure the high quality of the study.

3.3.1 Anonymity and confidentiality

Crow and Wiles (2008) claim that the participant's anonymity and confidentiality are vital in a social research study. Additionally, the researchers should always ensure that the data cannot be traced back to the participants (Crow & Wiles, 2008). The researchers verified the anonymity of the participants by sending out a consent form in advance stating that the only characteristics that will be used in the report are age and gender (Appendix 1). Moreover, the consent form informed that the participants could withdraw from the interview session at any time. In addition to this, the participants' name was removed and replaced with individual numbers in the report. The participants were given the consent form well in time before the interview, allowing them to read it in advance and later digitally sign it. With these actions, the researchers can expect more rich and expressive answers from the participants (Collis and Hussey, 2014).

Confidentiality concerns the protection of information gathered from the participants (Bell & Bryman, 2007). To comply with the confidentiality, the researchers handed out forms

containing information about the discussed topic and how the researchers were to handle and store the data (Appendix 1).

3.3.2 Credibility

Credibility is concerned with presenting truthful data and interpreting it correctly (Cope, 2014). Although qualitative studies have been criticized for being subjective, biased, and

lacking generalizability, it is argued to use a different approach in examining humans (Cope, 2014). Furthermore, credibility is highly connected to trustworthiness in qualitative studies (Cope, 2014; Golafshani, 2003).

A total of 16 individuals were chosen to participate in in-depth interviews. The researchers are aware that 16 interviews do not allow the answers to be generalized but are more likely to set a foundation for future research. Moreover, Generation Z is a young generation that lacks in research (Southgate, 2017), which makes it harder to replicate the results. In alignment with Generation Z being a young generation, the participants did not cover all ages, as the researchers were only in contact with participants born between 1996-2001. However, the researchers argued that the older segment of the generation would leave richer and more valuable information compared to the younger ones. Furthermore, the participants were chosen from the researcher's network, which means that they had a relationship with almost all participants. The researchers hoped that the familiar relationship would make the

participants feel more comfortable answering the given questions, giving truthful and honest responses. The researchers did also make it clear that the participants could withdraw from the interview at any time or decide not to answer a question.

Researchers agree that triangulation is advantageous to ensure credibility and trustworthiness in a qualitative study (Cope, 2014; Golafshani, 2003). A triangulation process includes using various methods, sources, or researchers for data collection to make more valuable

conclusions (Cope, 2014). Due to the delimitations of this study, it was not possible to combine different methods. Instead, the researchers aimed at interviewing both women and men with different types of diet choices. The researchers prepared well for the interviews by doing heavy research on the relevant topics before setting the questions, bearing in mind that a sample size of 16 participants is too small to generalize the results.

3.3.3 Transferability

Cope (2014) describes transferability as to which the findings can be applied to other settings. It is explained that a qualitative study has met this criterion if individuals who are not part of the study can associate the results with their own experiences (Cope, 2014). However, Cope (2014) argues that the criterion for transferability is reliant on the intention of the qualitative study, as it is more relevant if the research wishes to generalize a subject or phenomenon. This qualitative research uses a small sample size and does not have the goal to generalize.

Not to mention all participants are Swedish, which means that the researchers cannot guarantee similar thoughts and beliefs from other countries or cultures. By knowing the difficulty to generalize and the lack for guaranteeing similar answers across countries and cultures, it could be stated that the research has a low transferability. Nevertheless, Misco (2007) highlights a compromise between reader generalizability and the generation of theory, where grounded understandings in specific settings create explanations and interpretations for future research and have meaning and exploratory power.

3.3.4 Dependability

According to Cope (2014), a dependable study is achieved if other researchers agree with the decision paths at each stage of the process. Dependability refers to the stability of the data over resembling conditions and that the researcher's findings are consistent with the

empirically collected data (Cope, 2014). Tobin and Begley (2004) share that dependability is accomplished with the help of auditing. An audit trail displays the researcher's documentation of data, method, decisions, and end product (Tobin & Begley, 2004). The researchers decided to record all interviews and further transcribe and translate the answers into a shared

document. The data was further analyzed and interpreted individually at first. Later, the researchers analyze were compared to each other to comply with the triangulation process. The researchers worked with a flexible mindset by carefully reviewing each step of the analysis process and making changes if necessary. Lastly, both the researchers have been a part of each step of the research process, and notes have been taken from every meeting. 3.3.5 Confirmability

Tobin and Begley (2004) describe confirmability as to which degree the data is established objectively and clearly. The interviewers' answers should not be biased presented from the researchers' standpoints but should be objectively derived from the data (Tobin and Begley, 2004). To support the confirmability of the research, it is recommended to demonstrate clearly how the conclusions and interpretations were made, along with using rich quotes from the participants (Cope, 2014). The reader can easily follow the process of the data analysis in section 3.2.5. Furthermore, rich quotes have been used in the findings to support the founded themes. Finally, both the audit trail and triangulation are supportive tools to secure

confirmability (Tobin & Begley, 2004). These two tools have, as discussed before, been considered throughout the research process.

4. Findings

In this chapter, the empirical findings are showcased. With the help of thematic analysis, 1st order concepts, 2nd order themes, and aggregate dimensions are distinguished and

presented. The findings contain rich quotes to enhance the confirmability of the study.

The Gioia method (2012) was used to analyze the data gathered in the conducted interviews. Hence, when transcribing and coding the data we identified four aggregate dimensions namely “awareness”, “convenience”, “societal norms”, and “preferences and suggestions”. Each one of these aggregate dimensions is composed out of second order themes, that in turn are composed out of first order codes, as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Coding process

The specified aggregate dimensions have been found as a continuous topic of discussion within interviews across all genders and dietary preferences and will therefore be used in the following segment to provide a clear overview of the main contributing factors behind the sample's choices in terms of food.

4.1 Awareness

The first aggregate dimension that emerged from the analysis was awareness, which is composed out of the three categories: impact, education, and health. The term awareness explains how aware the participants are of the environmental changes, and what impact the participants believe their actions have on the environment and their own health. Moreover, it was discussed in a handful of interviews how the participants encountered new information regarding sustainability, which was closely related to education.

4.1.1 Impact

Impact refers to how aware the participants were on how their own actions could affect the environment and animals. Furthermore, it also concerns if the participants believed that the meat industry in general impacts the environment in some way. All of the 16 participants agreed that the meat industry harms the environment in some way. Participant #3 states that: "From an environmental aspect, the breeding of animals is extremely inefficient and has an extreme impact on the planet." Participant #13 backs up this statement and declares that: " I absolutely think that meat consumption has a big impact. Especially in terms of export and so on and that there is a lot of pollution involved." Furthermore, both participant #10 and #16 highlights the fact that it is proven that the meat industry harms the environment, and #16 shares that: "[...] we have evidence and I personally believe in it too."

Even though all participants believed that the meat industry harms the environment to some extent, some of them pointed out some alternatives to it. For example, #8 shared the

following: "I believe that we in Sweden can handle these questions rather well by buying local and ecological meat [...]." Additionally, #6 states that: "We have climate compensated meat as well, and good terms for the animals. And then the people who are hunting their own meat are also doing something good for society." In addition to this, #11 believes that:

" [...] it really matters if you eat locally produced meat or imported because of course, the transport has a really big impact on the environment. People often say that cows release so many destructive substances that harms the environment, but so do some substitutes, and chemicals in processed foods, and transport."

The participants were further asked if they believed that the meat industry has an impact on animals. Most of the interviewees answered yes, however, not as many elaborated their

answer further. Participant #4 shares that "In terms of the animals, there are a lot of places in the world with a horrible condition for animals and even if it is better in Sweden, you are still taking the life of an animal after them just living a fraction of it." Furthermore, participant #3 expresses "what we put the animals through today [...] is only accepted because it is the norm."

4.1.2 Education

In addition to the discussion of families and their relation to dietary choices, a frequently addressed second order category as the role of school and education. Participant #9 stated that:

"I think a lot could start in school. I am studying to become a teacher, and I know how big of an impact the school has when it comes to forming young people's

opinions and minds [...] of course, schools can't force people to become vegetarians, but there could be more openness to it and more education about meat and its impact"

.

Moreover, participant #7 said, "I think a lot is based on a need for education in the field and making plant-based options a more natural part of life from a young age, in schools". As mentioned, schools were a general idea explored in the interviews, but the participants' answers illustrated that overall knowledge is needed from any source. Participant #11 demonstrated the importance of general knowledge while saying, "my brother started avoiding meat because he has a friend who is very knowledgeable and interested in

sustainability, so he has made us think more about that", and later went on to state that the knowledge shared made an impact on her own diet as well.

4.1.3 Health

Health is a common motivation behind all sorts of dietary choices, regardless of if that entails eating meat or not. Health is also a concept present throughout the results of the interviews, in different circumstances based on gender and personal preference. Furthermore, health is connected to the aggregate dimension of awareness since the participants discussed how aware they were on the health aspect in terms of eating meat or not. In general, a lot, more specifically six out of eight male participants, did mention working out and the health aspects of protein and growing muscles, either as a justification of their meat consumption or as a general societal identification of male culture.

Among the male participants, #8 stated: "They [boys who work out a lot] want a diet that contains a lot of protein and probably see that the only source to that is chicken and similar types of meat", to which #7 had a relating thought in terms of "[...] the culture at the gym is to talk about how much protein you need and how much chicken you will eat when you get home". As an opposition to the idea of wanting to build muscles and eating chicken being the perfect pair, female participant #11 stated:

"There are surely good nutrients in meat, but you can get that from a diverse diet without meat and you do not need meat to be healthy and feel good [...] you can live a perfectly healthy life without it [meat] despite being a guy".

Female participant #10 explained that "despite my family eating meat, my mom, who is a health coach, has always advocated eating a lot of varied and healthy foods that are good for the body". A lot of the female participants did believe that a varied diet was the source of the nutrients needed to fuel one's body and #16 stated, "We can get all the things we need from other sources than meat, and at least I feel mentally better".

4.2 Convenience

The second aggregate dimension identified in the data analysis is convenience. It is composed out of two second order categories: price and habits. Convenience refers to the participants’ habits, and what factors that could change these. Moreover, it was notified that the majority of participants did not want to sacrifice too much to change their current habits.

When the male participants of the interviews got questions regarding their motivations behind the diets and activities to aid the environment, the concept of convenience was very present throughout the discussion. Male participant #7 stated:

"I have never thought about cutting out meat completely [...] my girlfriend talks about it a lot, but it would require that it is convenient, fast and easy", with male participant #6 further expressing himself by saying: "I want some food that is convenient and goes fast".

The concept of convenience was further explored by the female interview subjects but in a different context, with female participant #13 sharing: "If I were to cook meat, it would mostly be hotdogs because it's convenient".