Degree Project, English and Learning

15 credits, advanced levelOral Corrective Feedback in Swedish

Primary Schools

Muntlig korrigerande återkoppling i svenska grundskolor

Malin Knutsson

Sandra Köster

Grundlärarexamen F-3, 240hp

Date for the Opposition Seminar 24th March 2020 Examiner: Shaun Nolan Supervisor: Damon Tutunjian

FAKULTETEN FÖR LÄRANDE OCH SAMHÄLLE

1

Preface

In this degree project, we have been equally involved throughout the working process. To some extent we have had different responsibilities but we both have carefully read through each other’s section. We conducted the interviews and observations together and we made the analysis of the materials in full cooperation.

Hereby, we have equally contributed to this work.

_______________________________ _______________________________

2

Abstract

English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers use different strategies to support language acquisition when teaching. This study focuses on one particular strategy: Oral Corrective Feedback (OCF). It is provided to support learners’ oral language skills, and takes numerous potential forms which can either be implemented implicitly and/or explicitly. According to many studies, recast is the type of OCF most commonly used by EFL teachers. Studies demonstrate however, that recast is the least effective approach for EFL learners’ uptake. The aim of this research study is to investigate how Swedish EFL teachers provide students with OCF. In addition, the intention is also to explore teachers’ and students’ perceptions of the usefulness of OCF for their skills development in English. The focus of this research study is on Swedish primary schools of grades 4-6. Two types of data-gathering methods were used in this study: interviews and observations. The results confirm that both explicit and implicit OCF was provided when observing the teachers’ approaches and strategies in classroom settings. Surprisingly, this research study reveals that recast was not favoured by the Swedish EFL teachers as they considered other types of OCF to be more beneficial to EFL classroom settings.

Key words: oral feedback, corrective feedback, oral feedback types, teachers’ approach, students’ reactions and responses to oral corrective feedback.

3

Table of Contents

Preface ... 1 Abstract ... 2 Table of Contents ... 3 1. Introduction ... 52. Aim and Research Questions ... 7

3. Background ... 8

3.1 Corrective Feedback………...8

3.2 When to use Corrective Feedback ... 9

3.3 Different types of Corrective Feedback ... 9

3.4 Student preferences of OCF ... 12

4. Methods ... 13

4.1 Participants ... 13

4.2 Materials and Procedure ... 14

4.2.1 Interviews ... 14

4.2.2 Observations ... 15

4.3 Ethical Considerations ... 16

5. Results ... 17

5.1 Teacher Interviews ... 17

5.1.1 ‘What do Teachers know about OCF?’ ... 17

5.1.2 ‘What Strategies do Teachers enlist for implementing OCF in the Classroom; why and when do they implement them; and how have their Approaches changed over Time?’ ... 17

5.1.3 ‘How do Teachers’ perceive their Students’ Reactions and Responses to the OCF provided?’ ... 21

5.2 Classroom Observations ... 23

6. Discussion ... 26

6.1 ‘What do Teachers know about OCF?’ ... 26

6.2 ‘What Strategies do Teachers enlist for implementing OCF in the Classroom; why and when do they enlist them; and how have their Approaches changed over Time?’ ... 27

6.3 ‘How do Teachers perceive their Students’ Reactions and Responses to the OCF provided?’ ... 28

7. Conclusion ... 30

7.1 Summary of Key Results ... 30

4

References ... 33

Appendix A ... 35

Interview Questions in English ... 35

Appendix B ... 37

5

1. Introduction

At a time of globalisation and internationalisation, English plays a major role. As Shamiri and Fravardin (2016) emphasise, speaking has often been regarded as the most essential language skill. Consequently, in order to be able to communicate in the English-speaking world students need to know how to speak English. In order to enable oral communication worldwide amongst young people, English as a school subject, and in particular those aspects which focus on oral communication, ought to be of great importance. It is therefore imperative to find methods to optimally design the teaching to develop and progress young students’ oral English skills. The application of Corrective Feedback (CF) is one such strategy to support the uptake of learners’ oral English skills (Ellis, 2009; Shamiri & Farvardin, 2016; Ölmezer-Öztürk & Öztürk, 2016).

Russell and Spada (2006) define CF as “any feedback provided to a learner, from any source, that contains evidence of learner error of language form” (p. 134). Lyster, Saito and Sato (2013) take more restrictive approach by claiming that CF is necessarily teacher-directed and functions as a critical scaffolding element for the promotion of second language growth. Under this conceptualisation, teacher-directed CF in educational contexts is necessary to expand and strengthen students’ language proficiencies. According to Lyster et al. (2013), CF can be present in either written or oral form (oral CF – OCF), and in this latter form, can be applied either implicitly or explicitly. Ellis (2007) further argues that OCF is a highly complex phenomenon that manifests cognitive, social and psychological dimensions, and teachers must consider that students are usually on different levels in processing information, interpreting different contexts, and have different backgrounds. Also, according to Russel (2009), whether and how to correct errors depends upon the methodological perspective to which a teacher subscribes.

Lyster et al. (2013) state that providing OCF can be challenging for teachers in some cases, yet it plays an integral part in education: without teachers’ support in correcting errors, the same mistakes would continue to be made without their existence being obvious to the students. In addition, according to Lyster et al. (2013) research has shown OCF to be an effective tool in second language acquisition classrooms. Nevertheless, correcting a student during communicative interactions can also generate emotional issues, such as embarrassment or anxiety, since oral correction is an immediate indication to the student that an error has been

6

discovered (Ölmezer-Öztürk & Öztürk, 2016; Safari, 2013; Roothooft & Breeze, 2016). This suggests that such an approach has potential limitations.

Recent reports and test results from the Swedish educational context reveal a clear need for guidance and strategies to address deficiencies in the oral performance and development of Swedish L2 English learners at the primary school level. According to a nationwide report evaluating Swedish primary schools in 2003, almost half of the students in grade 5 reported feeling somewhat uncertain when speaking English in the L2 English classroom. Furthermore, during an evaluation of student performance in the Swedish national subject exams for grade 5 in 2007, it was found that 10% of the students did not meet the requirement for approval on the oral exam (Myndigheten för skolutveckling, 2008). Likewise, a 2018 report by the Swedish National Center for Educational Evaluation investigating the learning outcomes in English for Swedish students in grade 7 showed that only 53% of the students achieved ‘good knowledge’ of oral skills.

The use of OCF has the potential to develop and increase young students’ oral English skills. The Swedish steering documents (2011), however, do not provide any instructions or guidelines governing the use of OCF in Swedish primary schools. In the absence of directives from Skolverket (2011), the effective use of OCF is not regulated, and might therefore result in great uncertainty and a lack of directive for EFL teachers when seeking to determine the best possible way to implement the use of OCF in the classroom. With this in mind, the current research study aims to examine how Swedish primary school EFL teachers provide students with OCF given the lack of guidance from Skolverket (2011). Furthermore, the intention is also to explore EFL teachers’ and students’ perceptions of the usefulness of OCF for English skills development.

7

2. Aim and Research Questions

In this research study, teacher interviews and classroom observations are used to examine how EFL teachers at Swedish primary schools provide students with Oral Corrective Feedback (OCF) given the absence of direction from Skolverket. The aim is also to explore teachers’ and students’ reactions and responses as to the usefulness of OCF for English skills development. This study will have a quantitative dimension where the authors will present a classification of the different types of OCF used by the teachers that were observed, as well as the frequency of occurrence of each type. The study will also be qualitative in that the authors will determine how Swedish students react and respond to OCF and identify the perceptions of Swedish teachers towards their own use of OCF.

The research questions, all pertaining to the Swedish primary school context, are as follows: ‘What do teachers know about oral corrective feedback?’

‘What strategies do teachers enlist for implementing oral corrective feedback in the classroom; why and when do they implement them; and how have their approaches changed over time?’

‘How do teachers perceive their students’ reactions and responses to the oral corrective feedback provided?’

8

3. Background

This section will provide a general overview of the significance of Corrective Feedback (CF) provided in classrooms. In section 3.1, the concept of CF will be defined. In section 3.2, a description of when to use CF in educational contexts will be explained. In section 3.3, various types of CF will be presented. Lastly, in section 3.4, the research currently supporting the use of CF in relation to students’ preferences will be discussed.

3.1 Corrective Feedback

The definition of feedback can be found in many contexts and is not only limited to education. Feedback is characterised as “a process in which the factors that produce a result are themselves modified, corrected, strengthened, etc. by that result” or “a response, as one that sets such a process in motion” (“Feedback”, n.d). Askew (2000) however, describes feedback differently: “a judgement about the performance of another with the intentions to close a gap in knowledge and skills” (p.6). Feedback described as above can also be applied within educational contexts, but the most common definition of feedback in classroom settings is known as ‘Corrective Feedback’ (CF).

Irons (2008) states that teachers are encouraged to think about what it is they are trying to achieve when providing CF. Furthermore, the quality and timeliness of feedback are key features for learners, and a good relationship between the teacher and the learner also influences learning progression. It is the teacher’s role to provide relevant CF without making a student feel anxious, upset or create misunderstandings through direct or indirect correction. Mohd Noor, Aman, Mustaffa and Teo (2010) further claim that good CF is given without personal judgment or opinion, fact based, always neutral and objective, constructive and focused on the future.

Waring and Wong (2009) claim that oral CF (OCF) in EFL-classrooms is not limited to the correction of errors but can also appear in form of ‘praising’ – often used in the absence of feedback where a student can respond or correct an utterance. An expression such as “very good” is an example of praising. However, Waring and Wong (2009) describe praising as something vague and unclear, seldom actually defining what the teacher considers to be ‘very

9

good’. For this type of feedback to function as support or to provide guidance, Waring and Wong (2009) emphasise the importance of being consistent when praising students.

3.2 When to use Corrective Feedback

Irons (2008) emphasises that feedback can be given in different contexts. However, Shamiri and Fravardin (2016) claim that correcting students’ errors can be challenging for teachers due to a variety of factors such as teachers’ background knowledge. Providing feedback that enhances students’ knowledge is what all teachers want to aim for, therefore teachers should be careful when providing CF in order not to discourage students from using the language.

The timing of CF can be provided immediately after an error is made, or be delayed and provided later, once the communicative activity is finished. The focus teachers differentiate between is fluency and accuracy, and whether or not the activity involves communicative interaction between learners. Teachers choose to delay giving CF when the practice is focused on instruction to encourage fluency in the classroom. According to Hernández Méndez and Reyes Cruz (2012), the criteria for both immediate and delayed CF are fulfilled when instructions focus on form aiming to promote accuracy.

Teachers ought to provide CF in moderation. Hernández Méndez and Reyes Cruz (2012), claim that excess correction can have a negative effect on a learner’s attitude or performance, whereas providing too little feedback can also be perceived as a hindrance for efficient and effective language learning. Studies conducted in classrooms reveal that students can modify their output depending on the kind of CF provided (Safari, 2013). Hence it is crucial to find the correct balance when giving CF in classroom settings. However, providing CF as suggested is not easy for teachers. These challenges will be investigated in this research study.

3.3 Different types of Corrective Feedback

CF can be classified into six different types: explicit correction, recast, metalinguistic feedback, clarification request, elicitation and repetition. The six groupings can be subdivided into two groups: reformulation and prompts. Explicit correction and recast are examples of a reformulation, since both these types of CF supply students with the correct answer without letting the student adjust the errors. Prompts on the other hand include more than one signal

10

when compared to reformulation, such as metalinguistic feedback, clarification request, elicitation and repetition (Shamiri & Farvardin, 2016; Ölmezer-Öztürk & Öztürk, 2016).

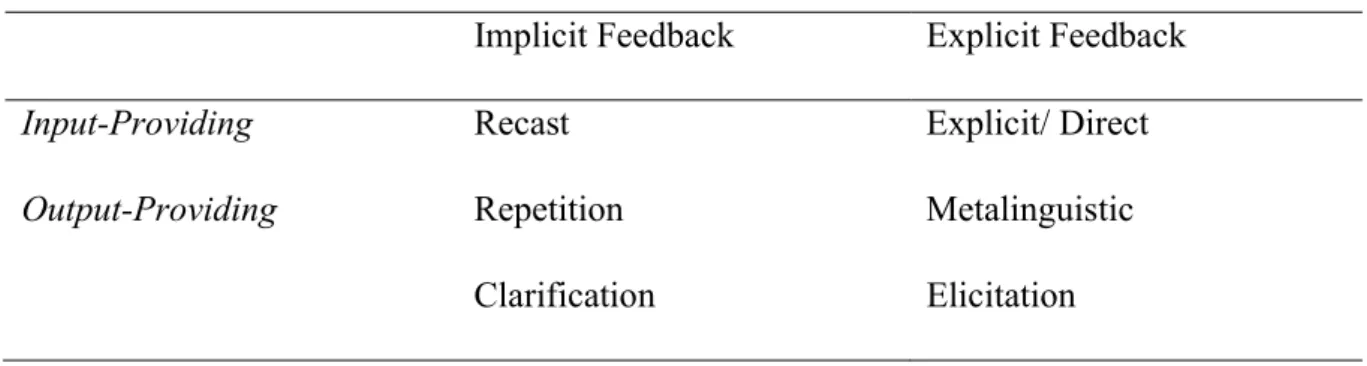

Shamiri and Farvardin (2016) classify feedback strategies as being either input-providing, in which the teacher provides the correct form to the student, or output-providing, in which the teacher encourages the student to self-correct. Shamiri and Farvardin (2016) also suggest that the different types of feedback can be categorised as shown in the table below (adapted from Ellis, 2012, p.139) describing how the correct form is provided:

Table 3.1 Taxonomy of Corrective Feedback

Implicit Feedback Explicit Feedback

Input-Providing Recast Explicit/ Direct

Output-Providing Repetition Metalinguistic

Clarification Elicitation

To further understand the theory behind the different methods of CF used in education as investigated by Lyster and Ranta (1997), a short description of the types is given below:

‘Explicit feedback’

The type of feedback that provides the learner with the correct form, while at the same time indicating that an error has been made, usually accomplished as below:

Example: S: On May.

T: Not on May, in May. We Say, “It will start in May”.

‘Recast’

Reformulates all or part of the incorrect word or phrase to show the correct form without explicitly identifying the error. Recasts is another type of input-providing feedback, since research indicates the correction being implicit rather than explicit. The corrected mistake is not immediately given to the learner. According to Ellis (2008), recast is “an utterance that

11

rephrases the learner’s utterance by changing one or more components; for example subject, verb, object while still referring to its central meaning” (p.227).

Example:

S: I have to find the answer on the book? T: In the book.

‘Clarification Request’

Indicates that the student’s utterance was not understood and asks the students to reformulate or repeat their answer. This type of feedback can cause problems when it comes to comprehension or accuracy. According to Lyster and Ranta (1997), implicit feedback as clarification requests is applied only when it followed by a student error.

Example:

S: What do you spend with your wife? T: Excuse me? Say again? (Or sorry?)

‘Meta-linguistic Feedback’

Gives technical linguistic information about the error without explicitly providing the correct answer. The feedback refers to comments or questions posted by the teacher, for example using linguistic terms concerning stress and verb tense. “This kind of CF makes the learner analyse their utterance linguistically, not quite in a meaning-oriented manner” (Shamiri & Farvardin, 2016, p.1068).

Example:

S: There are influence person who. T: Influence is a noun.

‘Elicitation’

Prompts the students to self-correct by pausing, so that the student can fill in the correct word or phrase. An example is when the teacher asks questions or pauses to directly elicit the correct form from the student.Lyster and Ranta (1997) highlight that “teachers can also use questions to elicit correct forms, such as, how can we say X in English?”. Elicitation is thought to be the least explicit output-providing form of CF since it leads to students correcting their mistakes themselves.

12 Example:

S: This tea is very warm T: It´s very?

S: Hot.

‘Repetition’

Repeats the student’s error while highlighting the error or mistake to draw learner’s attention to it. In so doing, teachers change their intonation to emphasise the error. Shamiri and Farvardin (2016) consider repetition as an implicit form that is output-provided, since no form is supplied to the learner.

Example:

S: I will showed you. T: I will ‘showed’ you? S: I will show you.

(Safari, 2013;Shamiri & Farvardin, 2016; Ölmezer-Öztürk & Öztürk, 2016).

3.4 Student preferences of OCF

Lyster, Saito and Sato (2013) state that studies have revealed that students’ preferences are essential in determining the effectiveness of OCF since they can affect learning behaviour. Likewise, it has been shown that there is a potential difference between teachers’ intentions and students’ interpretations of CF that could negatively impact learning. Studies also indicate that students’ preferences differ according to their cultural backgrounds, previous and current language learning experiences, or proficiency levels (Lyster et al. 2013). It is also highlighted that students in general prefer receiving encouraging feedback that motivates them, rather than feedback that solely highlight errors.

13

4. Methods

This section presents the methods and the material used to conduct this study, as well as the ethical considerations guiding the procedure. The aim was to collect a small sample of data to provide an understanding and knowledge regarding teachers' and students' perceptions regarding Oral Corrective Feedback. In section 4.1 the selection of participants will be explained. In section 4.2 the procedure of data collection will be described. Lastly, in section 4.3 we will present the ethical considerations applied during the research study.

4.1 Participants

The participants of the study comprised teachers and students from two primary schools situated in the south of Sweden. Ethical considerations dictate that all participants and the schools have been anonymised.

The two schools are hereafter referred to as ‘School A’ and ‘School B’. School A is a heterogeneous primary school with students from grades K – 9. School B is a homogeneous primary school with students from grades K – 9. School A is a state school while school B is a private school. Both schools have approximately 550 students. Similarly, both schools provide English instruction from grade 1. At school A, the students have approximately three English lessons per week. At school B, however, the students have about four English lessons per week. Also, at School B there is an extra teacher present for one to two lessons per week.

In total six EFL teachers were interviewed. Each of the teachers that were interviewed holds a university teaching degree and all except one are qualified to teach English at grade 3 to 6. The working experience among the teachers varied from 2 years to 31 years. The teachers’ ages varied from 28 to 61. Hereafter, the teachers are referred to as ‘Teacher 1’, ‘Teacher 2’ etc. in the study. Teacher 1, Teacher 2 and Teacher 3 work at School A. Teacher 4, Teacher 5 and Teacher 6 work at School B.

14 Table 4.1 Teacher Interviews

Teacher 1 Teacher 2 Teacher 3 Teacher 4 Teacher 5 Teacher 6

Age 53 58 61 28 37 52

Qualified for teaching English

yes no yes yes yes yes

Working experience

31 years 18 years 15 years 2 years 10 years 23 years

The intention was to conduct observations in six different classrooms at two primary schools, but due to the winter holidays, a lack of time meant that only three observations could be made. The classes observed were grade 4, grade 5 and grade 6 at School B. Three lessons, each one lasting between 40-50 minutes, were observed using non-participant observations.

Table 4.2 Classroom Observations

Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6

Teacher T4 T6 T5

Number of students present (boys/girls) 21 (12/9) 21 (10/11) 20 (9/11) Age 10 11 12

Number of years taught in English

4 5 6

4.2 Materials and Procedure

4.2.1 Interviews

Since interviews were considered to be the best way to extract information about the teachers’ thoughts and feelings concerning OCF, semi-structured interviews were used as one method to collect data. To create a safe and comfortable environment for the informants, the interviews were held in places suggested by the participants. Likewise, speaking in ones' native language results in a more comfortable atmosphere and more open participants that may speak more

15

freely. Therefore, all the interviews were held in Swedish, lasting for 15-20 minutes. Also, prior to the interviews, the interview questions were supplied to the participants in order to prepare for their interview.

The interviews consisted of 22 set questions constructed and categorised in accordance with the research questions. The questions are presented in English and Swedish in appendices A and B respectively. Each interview was divided into four parts. The first part aimed to establish each teacher’s professional background, in order to understand and analyse various aspects that may have influenced the answers given. For example, teaching experience and ages of the participants were established. The second part focused on each teacher’s knowledge and use of OCF. The third part concentrated on the strategies teachers apply to implement OCF in the classroom and which types of errors they tend to correct. The fourth part aimed to investigate teachers' perceptions of their students’ reactions and responses to the OCF provided.

Also, since Alvehus (2013) claims that an interviewer might not have the time to write everything down while being a good listener, the conversations were recorded to enable an accurate transcript. This allows a more thorough analysis of the collected data. Interviews were conducted prior to the classroom observations.

4.2.2 Observations

Classroom observations were included as part of the research study in order to examine various aspects of teacher student communication in the classroom. More specifically, the observations focus on what types of OCF the teachers provided the students with compared to the teachers’ own perception and views of their own use of OCF during the interviews. Another aspect of conducting observations was to be able to investigate in what ways the students reacted and responded to the OCF given to them. Observations were recorded using a dictaphone (as opposed to via a phone) to ensure that the data was secure and could not be compromised, in line with both ethics’ regulations and GDPR. The dictaphone was supplied by Malmö University.

Prior to the observations, two protocols were created to help the researchers stay focused on the aspects that needed to be examined. The first protocol was made to measure the frequency of each feedback type: explicit correction, recast, metalinguistic feedback, clarification request,

16

elicitation, repetition and other. The second protocol was made to determine the rate of errors made by a student corrected by the teacher. For each protocol, Lyster and Ranta’s (1997) classification of the feedback types was used. The data collected was later analysed quantitatively as well as qualitatively to obtain an understanding of the various types of OCF provided by the teachers during the lessons.

4.3 Ethical Considerations

According to Christoffersen and Johannessen (2015) there are four main requirements that must be included during a research process: the information requirement, the consent requirement, the confidentiality requirement and the requirement of usage. In this research study, these ethical requirements have all been adhered to.

Prior to the study, participants were informed of the general aim of the survey and their rights, including that participation in the survey was voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time. They were also notified that the interviews, as well as the observations would be recorded using a dictaphone and that all interview material would be anonymised and kept confidential. The fact that material would be used solely for the purposes of this research project was also pointed out. Finally, they were then provided with a letter of consent to be signed.

17

5. Results

This section contains the information obtained from the interviews and observations conducted with the panel of teachers as described above. The results correspond to the three primary research questions, and the interview questions can be found in appendix A.

5.1 Teacher Interviews

5.1.1 ‘What do Teachers know about OCF?’

In all six teacher interviews, OCF was referred to as a strategy to develop and enhance students’ oral English skills. The teachers interviewed all indicated that they perceived OCF as being easy to provide. Furthermore, the interviewees deemed OCF an important tool in language acquisition, claiming that OCF is frequently used in their lessons. However, they also considered OCF to affect learners both positively and negatively.

The above notion that OCF impacts students both positively and negatively was emphasised by T4 who explained that this is largely dependant on learners’ proficiency. In addition, the majority of interviewees agreed that OCF is given as a matter of course without being given much thought. T2 expanded on this point by responding that OCF was implemented constantly both verbally and in writing. As students are being taught, their use of grammar and any mistakes made naturally lend themselves to OCF being implemented instantaneously.

5.1.2 ‘What Strategies do Teachers enlist for implementing OCF in the

Classroom; why and when do they implement them; and how have their

Approaches changed over Time?’

Answers to questions 7 and 8 varied amongst the interviewees. However, one common factor was that they all agreed on the importance of providing OCF tactfully without offending or singling out individual students. T1 emphasised the importance of creating a positive atmosphere in the classroom and giving students confidence. This in turn results in OCF being perceived as positive and encouraging, leading to students that actively participate in lessons and do not worry about making mistakes. T2 highlighted the importance of providing positive

18

feedback to the whole class before addressing individuals: “Let students make mistakes when in front of the whole class then correct them later when working individually.”

In addition, T3 argued that the correct provision of OCF depended on the context. For instance, it was argued that excessive corrections are counterproductive regarding pronunciation, as repetition will address any shortcomings naturally. T4 sees great value in explicitly correcting students that struggle with difficult words, which T5 expanded upon by expressing that students should be corrected by repeating the phrase in question in the corrected form. Provided this is being done positively, the student will then have the confidence to try again. T6 seemed to believe in letting students make mistakes without immediate corrections being given: “The students are still young and will eventually learn from their mistakes. Repeated corrections will discourage them from speaking.”

In response to question 9, the interviewees agreed unanimously that no guidelines and/or directives from past and present employers regarding the implementation of OCF had ever been given. As a direct consequence of this matter, T6 confirmed that thoughts about providing students with OCF had been shared among the teaching staff. The other interviewees explained that owing to the lack of guidance concerning OCF, a ‘learning by doing’ approach was implemented to address this. These teachers essentially were left to their own devices and learnt the implementation of OCF on the job on a trial and error basis.

The responses to question 10 indicated that teachers generally speaking seemed reluctant to correct students’ grammar mistakes, even in discussions. Particularly special needs or low-performing students that struggle with both written and spoken aspects of language learning were mentioned in this regard, since the teachers believed that providing excessive OCF would impact their learning process negatively. This was mainly attributed to excessive corrections making them feel inadequate and hindering progress.

The responses to questions 11, 12 and 13 were similar in nature. As students are at different levels of ability, they need different levels of support. As such, those with difficulties tend not to be corrected as much as the better performing students in order to encourage them to participate as much as possible. Letting them make mistakes without singling out individuals is instrumental in boosting their confidence and giving them the motivation to keep trying. T2 confirms this by choosing to always highlight the positive aspects of low-performing students’

19

contributions and not singling out weaker students: “It is important to correct students quietly on a one-to-one basis sitting beside them and whispering in their ear.” T1, 2 and 3 agreed that one should refrain from correcting weaker students’ pronunciation, as discussed above.

T4 believes in providing the same type of OCF, adapting the approach to the type of student one is dealing with. T5 and T6 however modify their approach depending on the students’ response, with no response meaning that the student needs to be approached differently.

The principal areas of correction were identified as pronunciation and grammar. The principle of different accents resulting in different pronunciations of the same word can be hard to grasp for year 4 students, who might pronounce a word a certain way only to be corrected by a teacher for something that is essentially correct. Likewise, there are different words for the same object, such as ‘pants’ vs. ‘trousers’ which are both correct depending on the speaker’s origin. In these cases, it was agreed that teachers need to correct such perceived mistakes tactfully and not based on personal preference. T3 addresses this issue by only correcting students’ utterances in context, claiming that it is more important to motivate confident learners’ that are positive and engaged in the activities.

T2 finds it easier to correct high-performing learners, who tend to be quicker to correct their mistakes than low-performers. In addition, OCF is received better than by low performers: “When there are difficulties to pronounce certain words, I often encourage the whole class to come up with the correct pronunciation rather than singling out one student’s mistakes in front of the class.”

In the past, teachers focused on the correction of students’ written work rather than their speaking skills, contrary to present day teaching practices where speaking skills are more of a focus. This is a direct result of increased exposure to spoken English on TV and the Internet, resulting in students generally having good pronunciation skills. The emphasis of oral skills is on students being able to make themselves understood and corrections govern the content of a sentence rather than the pronunciation.

The answers to question 14 suggest that the implementation of OCF has changed over time. Teachers generally seem to provide less OCF and instead focus on setting a good atmosphere in the classroom. This results in motivated and engaged learners, thus perceiving OCF as

20

positive with students being open to corrections. All teachers agreed that they do not correct learners as frequently as in the past, in order not to inhibit the learning process, with T4 suggesting that: “I correct the students more directly today than before.”

There is a suggestion that students evaluate the OCF they receive for relevance. T1 and T3 attribute this to teenagers not being as open to such feedback as they were in the past owing to changes in society where teachers are now perceived differently. As a result, teachers need to adapt their approach to OCF to ensure it is of maximum benefit to the student.

The answers from question 15 revealed that teachers do reflect on their teaching. Whilst T3, T4, T5 and T6 did not address this aspect in detail, they agreed that they reflect on the OCF they provided. T1 analysed the corrections afterwards to identify different ways of reaching all students more successfully. T2 reflected on the use of American pronunciation when teaching, sometimes confusing the learners who may be more accustomed to English received pronunciation as per the teaching material used. Different pronunciations of the same words occur, for example the word ‘tomatoes’ being pronounced differently depending on the origin of the speaker. T1 said “I sometimes reflect on how I teach and correct my students; it is important not to correct the students when you do not know them well.”

The interviewees had different ideas regarding the provision of OCF. T1 considered not singling out individual students as being most important: “It is important for the students to learn from their mistakes and for them to dare to pronounce a word incorrectly without feeling uncomfortable.” T2 argued that “words can be pronounced or spelt the same way but have different meanings, and these kinds of error need to be corrected and discussed with the whole class” again emphasising the need to create a positive atmosphere in the classroom. This thought was then expanded upon, stating that “I seldom correct students’ grammar such as tense, since I think that they are still too young to handle such a correction.”

T3 and T5 consider it vital not to correct students’ pronunciation in front of the class as this tends to be good, owing to reasons described above. This ties in with T4’s view, who focuses on having students receive OCF in a manner that is beneficial to them and helps the learning process. As explained above, the general consensus among the teachers is that repetition will ensure correct pronunciation over time.

21

There were considerable differences in opinion concerning the question of when students should be provided with OCF. T1, T2, T3 and T5 suggested that OCF should only be provided during classroom discussions or when reading aloud. This results in an ideal platform to correct pronunciation as well as grammar in a less formal setting, thus giving the student the maximum benefit from the OCF provided. T4 and T6 disagreed with this notion, suggesting that OCF ought to be used frequently in lessons regardless of the nature of the task.

5.1.3 ‘How do Teachers perceive their Students’ Reactions and Responses to the

OCF provided?’

The answers to question 16 indicated clearly that OCF is received differently depending on students’ age. Younger students tend to be more open to receiving such feedback than students of year 5 and 6. T2 and T4 confirm this by agreeing that year 4 students consider getting feedback as being natural, and it is not perceived negatively. T1, T3 and T5 suggest that OCF is not always received positively by the older students of years 5 and 6 who have a higher tendency to take such corrections personally, as confirmed by T3: “Some students are not open to teachers’ corrections whilst others that are motivated and driven take teachers’ corrections positively.”

T1 referenced the above discussion to Carol Dweck’s book “Mindset: The New Psychology of Success”, referring to students having a ‘static mindset’. Generally speaking, the sense of entitlement and not being open to corrections that is prevalent in children of the present day hinders their progress by not being open to feedback from teachers.

For questions 18-22 the responses varied. Generally, the teachers thought that OCF mostly supported language development but with exceptions. This was dependent on the frequency of OCF provided, and being careful not to single out individual students by correcting them in front of the whole class. Additionally, it was confirmed that providing excess OCF negatively impacts learners’ motivation and results in having learners not wanting to speak.

The answers to questions 19 and 20 were similar. T1 emphasised the importance of letting learners reflect on their mistakes and not offering corrections straightaway, suggesting that such corrections are more effective in small groups. This contributes to students gaining confidence and responding positively to the feedback given, a view that is echoed by T3 and T6 who

22

suggested that language development is aided by students in small groups helping each other. All teachers agreed on the importance of not providing excessive OCF, since applying OCF in moderation results in motivated and engaged students rather than putting them under undue pressure with excess corrections.

In response to question 21, it was unanimously agreed that on occasion, the provision of OCF can make students uncomfortable. This can be mitigated against by working in smaller groups and providing corrections sparingly. T1 seemed to be aware of challenges concerning students’ attitudes, referring to students having a static mindset. This issue, as described earlier, makes it difficult for teachers to encourage students to try harder despite making mistakes. T1 tries hard to ensure that students understand that any criticism is not personal, but quite often OCF is considered to be the opposite – negative and a personal attack.

According to question 21, the interviewee agreed that there are occasions when students feel uncomfortable as in question 19 and 20. Teachers can avoid students feeling insulted or uncomfortable by working in smaller groups, providing corrections in moderation. Also, by using digital tools for learners with special needs teachers adjust their teaching according to the learners’ response to OCF. Furthermore, T1 argued that “Students have a mindset that is static and cannot always accept changes to development.” For example, to learn requires effort from students. This can trigger a learner’s negative self-image if they receive OCF in a context which is not accepted. As T1 stated: “The criticism is not personal but can be interpreted as negative and personal.”

The response to question 22 showed that generally students respond positively to OCF, provided the classroom environment is positive and engaging. One way to ensure this is for teachers to have a good relationship with their students. Having confidence in the teacher is another important factor. Once students feel they can trust the teacher, any feedback received is more likely to be perceived as positive. T5 confirms this, stating “It is easier to correct students whom I have a close relationship to and meet regularly. They do not take my feedback negatively.”

23

5.2 Classroom Observations

In addition to teacher interviews, classroom observations were conducted. The purpose of the classroom observations was to examine the role of OCF in classroom settings, as well as students’ responses to the OCF provided. The interviews informed the authors about the teachers’ beliefs and experiences of OCF, whilst the observations revealed the actual use of the different types of corrective feedback. For purposes of this study, the students were observed in their natural environment in the classroom during a normal school day. The results from the observations will be presented and analysed in two tables.

The classroom observations were made at school B, in three classes – grade 4, 5 and 6. The teachers who participated in the interviews were those whose classes were observed – T4 (grade 4), T5 (grade 6) and T6 (grade 5). The observations were conducted over a period of approximately 45-50 min, covering three school hours. School B, as mentioned before is a homogeneous school and has more English teaching compared to school A.

Prior to the observations, two protocols were constructed to facilitate the field studies. The first protocol was made to measure the frequency of each feedback type occurring. In the protocol corresponding box was ticked whenever there was a verbal correction of a student’s utterance. The second protocol was made to determine the rate of errors made by the students and corrected by the teacher.

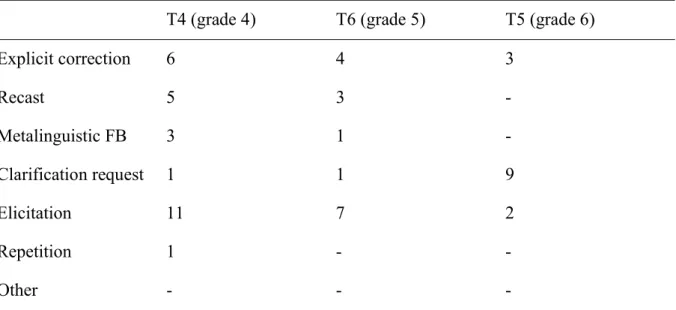

Table 5.1 Type of Feedback and Frequency of Occurrence (raw count) by Teacher T4 (grade 4) T6 (grade 5) T5 (grade 6)

Explicit correction 6 4 3 Recast 5 3 - Metalinguistic FB 3 1 - Clarification request 1 1 9 Elicitation 11 7 2 Repetition 1 - - Other - -

-24

Table 5.1 shows that the most frequently given corrections were elicitation and clarification request, depending on the year concerned. Elicitation was, by far the most frequently given feedback type in year 4 and 5. In year 6 however, clarification request was mainly used. Clarification, however, was only provided once in year 4 and 5. On the other hand, elicitation request was found only twice in year 6. It is noteworthy that studies have shown that recast and explicit correction are generally the OCF types most commonly used by teachers in education (Shamiri & Farvardin, 2016; Ölmezer-Öztürk & Öztürk, 2016). Likewise, it was identified during the observations that recast and explicit correction were being provided regularly but in moderation. This could be due to teachers wanting the learners to try to correct themselves before providing the correct form.

During the observations OCF was provided regularly in all grades, but more frequently and differently in grade 4. The reason could be the learners’ different proficiency levels and teachers adapting their teaching according to the learners’ different needs. Furthermore, it was discovered that in grade 5 the teacher varied the use of the different OCF types, whereas in grade 6 the different types of OCF were used in moderation focusing mostly on clarification request. This could be due to the learners age, or their more advanced language skills. Also, the teacher in grade 6, T5, had a different approach to correct learners compared to the other two teachers. The least commonly used type of CF observed by the researchers was repetition and metalinguistic feedback. This is not surprising, as these types of CF are confirmed as being the least used in education according to research done by Shamiri and Farvardin (2016).

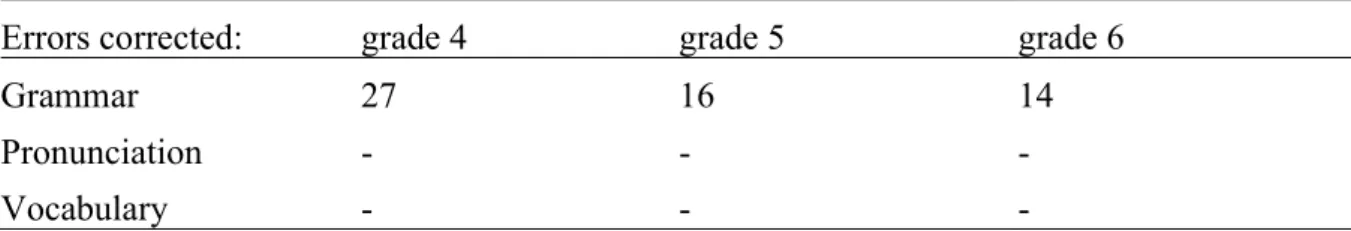

Table 5.2 Errors corrected

Errors corrected: grade 4 grade 5 grade 6

Grammar 27 16 14

Pronunciation - - -

Vocabulary - - -

Table 5.2 illustrates that all corrected errors focused on grammar. During the observations the teachers worked with grammar focusing on the use of tense, as well as vowels and consonants, concentrating on the applicable use of ‘a’ or ‘an’. Consequently, no corrections were identified regarding learners’ pronunciation or use of vocabulary. During the observations, it was noticed that OCF was provided more frequently in grade 4 compared to grade 5 and grade 6. It was also

25

observed that the target language was not used as often in class 4. Since younger students do not have enough vocabulary to understand and follow the instruction only in the target language, the teacher must adapt the teaching to meet the needs of all students. The amount of CF given in grade 5 and grade 6 was equal and mainly focused on the use of tense.

26

6. Discussion

The aim of this research study was to explore and investigate how EFL teachers at primary schools in Sweden provide students with OCF. Furthermore, the aim was also to examine teachers’ and students’ perceptions and opinions towards OCF. The investigation is quantitative in that the authors present a classification of the various types of OCF used by the teachers as well as the relative frequency of occurrence of each type in their usage. The investigation is also qualitative with the authors seeking to determine students' reactions and response to OCF.

Even though there are several types of OCF, not all of these were detected in the observations. Furthermore, the data collected reveals that teachers have different thoughts regarding OCF and focus on different parts of language learning, making the outcome from the interviews and the observations comparable and interesting to analyse. The important role of feedback, however, was identified and recognised by all six teachers. Also, school B teachers’ knowledge and perception of OCF that emerged during the interviews were consistent with their OCF strategies used in the classroom during the observations. In the following sections, the authors discuss how interview and observation data specifically informs each of the three research questions.

6.1 ‘What do Teachers know about OCF?’

The teachers interviewed all referred to OCF as a method used to support and improve students’ speaking skills in English. The interviewees considered OCF as being an important tool in language acquisition and pointed out that being easy to provide, it is used frequently throughout their lessons. Similarly, the important role of feedback has been emphasised by Ellis (2009), claiming that in both behaviourist and cognitive theories of second language (L2) learning, feedback is seen as a means of fostering learner motivation and ensuring linguistic accuracy, hence contributing to language learning. Also, when researching the effectiveness of OCF, Lyster and Sato (2010) found that OCF as a supportive strategy was especially good for young learners.

None of the teachers interviewed had been given tuition covering the provision of OCF to students during their teaching training. Nor had the interviewees, except one, received guidelines or directives from their employer regarding this matter.

27

6.2 ‘What Strategies do Teachers enlist for implementing OCF

in the Classroom; why and when do they enlist them; and how

have their Approaches changed over Time?’

The interviewees all highlighted the importance of timing. Mohd Noor, Aman, Mustaffa and Teo (2010) claim that providing feedback at appropriate times and providing appropriate OCF in accordance with learners’ individual needs helps to facilitate student learning and has equal importance based on instructional activities. The teachers interviewed also claimed that they preferred to provide OCF individually. Likewise, Hernández Méndez and Reyes Cruz (2012) emphasised that individual correction seems to be more effective, as the learners addressed become aware of their errors, notice the error, and correct it accordingly.

During the interviews, all teachers claimed that they provide a varying amount of OCF to students at varying frequency. The teachers stated that because students need different kinds of support, one often chooses not to correct students with difficulties with the same focus or approach, as the more talented students. During the observations the authors found that statement to be correct. Also, Mohd Noor, Aman, Mustaffa and Teo (2010) emphasised the importance of providing quality rather than quantity CF since excess CF can be disadvantageous to students' learning. Mohd Noor et al (2010) also stated that students struggling with language acquisition often have low self-confidence and find it hard to speak in front of others. Consequently, it is important to motivate these students and let them make mistakes. Hernández Méndez and Reyes Cruz (2012) however claimed that shyness or low motivation should not be factors to consider in the provision of CF.

Lyster, Saito and Sato (2013) stated that teachers usually focus on grammatical errors when providing OCF to students. This phenomenon was identified in the interviews as well as during the observations. In the interviews the teachers also reflected upon their strategies to correct students’ pronunciation, but they all agreed upon correction of students' pronunciation being a minor issue. Hernández Méndez and Reyes Cruz (2012), on the contrary however, emphasise that generally pronunciation is corrected frequently, although students’ age and proficiency have an impact on how much OCF is provided regarding learners’ pronunciation.

During the interviews it was also revealed that teachers often combined giving praise with OCF in their teaching. The value of providing positive feedback (giving praise) was pointed out by

28

all teachers. Likewise, in the observations it was noticed that providing positive feedback, such as praise created a positive atmosphere and increased learner’s engagement and motivation. However, according to Waring and Wong (2009), corrections are not a key consideration when the teacher praises a student and could consequently result in students receiving praise for both correct and incorrect answers. Also praising could sometimes be perceived as vague and unclear since the students may not understand what it referred to. Combining OCF with praise should therefore be provided in moderation in order not to confuse learners. Furthermore, the observations made showed that the less experience teachers have, the more engagement they showed when providing OCF.

The classroom observations at school B revealed that both implicit and explicit feedback were used during teaching. Likewise, it was noted that similar types of OCF strategies were applied by all teachers except one. The types of OCF types used during the observations were explicit correction, elicitation and clarification request. Studies have shown that these types of OCF have shown the most successful results regarding student generated repair as well as increased student learning (Lyster & Ranta, 1997; Safari, 2013). The conclusions drawn from the interviews with the teachers at school A however revealed that they tend to use recast and explicit correction instead. According to Russell (2009), recast is the strategy that is generally used when correcting students, whereas explicit correction results in giving students a clear understanding of the error made and helps them become aware of and understand their mistake.

6.3 ‘How do Teachers perceive their Students’ Reactions and

Responses to the OCF provided?’

Lyster et al (2013) claimed that students’ preferences are crucial for two reasons: firstly they can influence learning behaviours and secondly, there could be an confusion between teachers’ intentions and students’ interpretations. This may have a negative effect on language learning. Furthermore, as stated by most of the teachers interviewed, Lyster et al (2013) claim that students tend to prefer receiving CF in most contexts, but factors such as students’ cultural backgrounds, previous and current language experiences and proficiency level need to be considered. Also, since learners have different attitudes towards OCF, teachers should be aware of this and decide whether to consider it for the provision of CF. Because OCF can cause emotional issues and discourage learners' language acquisition, the teachers emphasised the importance of letting students make mistakes. Consequently, students should not be corrected

29

on all occasions since OCF can be understood differently depending on students’ individual needs (Hernández Méndez & Reyes Cruz, 2012).

The teachers that were interviewed believed that most students interpret OCF as positive. Hernández Méndez and Reyes Cruz (2012) claim that teachers in general think that students do not get annoyed or feel bothered when provided with OCF which backs up the results from the interview. However, the interviewees also stated that students’ perceptions of the OCF provided to some extend depended on what grade they attended. According to the interviewed teachers, younger students respond positively and are more open minded to receive OCF compared to older learners. The interviewees revealed that older students tend to perceive OCF as a personal attack and therefore do not respond to the OCF given. Likewise, Dweck (2018) stated that students nowadays avoid challenges, give up easily and ignore criticism – referred to as having a ‘static mindset’, resulting in having learners that are not open to OCF.

The importance of letting learners reflect on their mistakes and correct their utterance afterwards rather than straightaway was also emphasised in the interviews. Lyster et al. (2013) confirm this by stating:

Learners are likely to benefit more from being pushed to self-repair by means of prompting, especially in cases where recast could be perceived as approving their use of non-target forms and where learners have reached a developmental stage in their use of the non-target forms (p.30).

In this case, during the observations the authors noticed that this was effective on learners when elicitation, explicit and clarification corrections was provided.

Overall, the interviews revealed students’ general attitudes when receiving feedback as being positive. The same phenomenon was identified during the observations. The comments made by the interviewees emphasised the importance of knowing your students well, having a positive atmosphere, not singling out individuals, as well as providing OCF in moderation. Also, according to Hernández Méndez and Reyes Cruz (2012), it is important to know students very well in order to know if OCF can be used or not.

30

7. Conclusion

7.1 Summary of Key Results

In this research study the authors explored and investigated how Swedish EFL teachers provide students with OCF and examined teachers’ and students’ perceptions and opinions towards OCF. During the study it was revealed that teachers have different thoughts regarding OCF and focus on various parts of language learning, making the results comparable and interesting to analyse.

The important role of OCF was identified and recognised by all teachers. Also, the importance of teacher-student communication to find the type of OCF that will benefit both was noted. The answers the teachers provided during the interviews corresponded to the observations made in the classroom studies. The teachers, however, had different views regarding which OCF strategies to use. All interviewees however emphasised the significance of knowing their students well and the importance of providing OCF in moderation. Also, the interviewed teachers all stressed that OCF should be provided correctly according to students’ needs, and that care must be taken not to single out individuals.

During the observations it was seen that the way in which the OCF was given to a student varied according to the learners’ different needs, proficiency level and age. It was also noted that the different OCF strategies that were applied during the observations did not correspond to those most commonly used by EFL teachers worldwide, one such example being recast. The teachers however, pointed out the importance of being constructive and positive when giving OCF. The importance of providing a combination of OCF and praising was emphasised, with the interviewees considering this to be motivating and encouraging for the students. This therefore makes it beneficial to the learners’ language acquisition.

Throughout the process it was observed by the authors that the type of OCF strategy used had a major impact on how students interpret and accept teachers’ corrections. Likewise, all teachers that were interviewed considered the correct use of OCF to have a positive effect on learners’ language development. OCF needs to be applied with care since the students are young children wanting to learn and can respond to corrections in a negative way. Also, the interviews

31

revealed that the teachers that were interviewed noticed that their use of OCF had changed over time and they could all identify differences in the way they provided OCF in the past compared to the present.

There are some limitations associated with the survey. Firsty, the data is gathered from one municipality only. The results of the study may have been different if the data collected had been obtained from different municipalities with varying socio-economic backgrounds. Also, the number of interviewees could have been larger to ensure more accurate results. Furthermore, the results obtained from the interviews only reveal what the teachers believe to be working in educational contexts, factual evidence such as assignments or students’ thoughts were not investigated. The observations only involved three lessons at one school and had they been carried out for an extended period this would enable observations of several lessons, and not just at one school. Observations at different schools would probably result in having more valid data. As a suggestion for further research, the study should also take the limitations that were discussed into account.

Lastly, this study resulted in an increased awareness of the variety of OCF strategies that can be provided to students, and the importance to fulfill the students’ individual needs. As future teachers, the authors have learned that OCF has a major impact on students’ language acquisition. The knowledge gained during this research study will unquestionably influence their future teaching strategies – being aware of the limitations that some forms of OCF provide will mean that the focus will be put on using a variation of OCF strategies. As the study confirms, the key to success in delivering OCF lies in adapting its use to best suit the individual student’s needs, and future teaching will be influenced by a customised approach for the individual learner.

7.2 Suggestions for further Research

In addition to the above-mentioned proposal, a suggestion for further research is to expand this study to a larger scale. Since this research study involves perceptions from a small sample – six teachers and observations from three classrooms, the results may have a certain bias. A study conducted over a longer period of time, such as one year, would have provided a more valid and reliable result concerning the effectiveness of OCF. This would have given the opportunity

32

to both observe and teach a class to investigate which type of OCF is most beneficial to learners’ uptake through the authors’ own teaching.

Conducting student interviews could also have revealed how students feel about OCF to support language learning. Do they learn from it? Do they feel offended when provided OCF? Exploring this area exceeded the scope of this particular research study.

33

References

Alvehus, J. (2013). Skriva uppsats med kvalitativ metod. Stockholm: Liber. Askew, S. (2000). Feedback for learning. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Christoffersen, L., & Johannessen, A. (2015). Forskningsmetoder för lärarstudenter. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Dweck, C.S. (2018). Du blir vad du tänker. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

Ellis, R. (2007). Corrective feedback in theory, research and practise. University of Auckland. Retrieved from: http://www.celea.org.cn/2007/keynote/ppt/Ellis.pdf

Ellis, R. (2008). A typology of written corrective feedback types. ELT Journal, 63(2), 97-107. Ellis, R. (2009). Corrective Feedback and Teacher Development. L2 Journal, 1 (1), 3-18. doi: 10.5070/l2.v1i1.9054

Ellis, R. (2012). Language teaching research and language pedagogy (2nd ed.). USA: Wiley-Blackwell, Inc.

Feedback. (n.d). In Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved from:

http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/feedback?showCookiePolicy=true Hernández Méndez, E., & Reyes Cruz, M.R. (2012). Teachers' Perceptions About Oral Corrective Feedback and Their Practice in EFL Classrooms. Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development, 14(2), 63-75. Retrieved from:

http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1657-07902012000200005&lng=en&tlng=en.

Irons, A., (2008). Enhancing Learning through Formative Assessment and Feedback.

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business. Retrieved from: file:///C:/Users/Sandra/Downloads/9780203934333_googlepreview.pdf

Lyster, R., & Ranta, L. (1997). Corrective Feedback and Learner Uptake. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19(1), 37–66. doi: 10.1017/s0272263197001034

Lyster, R., & Saito, K. (2010). ORAL FEEDBACK IN CLASSROOM SLA: A meta-analysis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 32(2), 265-302.

Lyster, R., Saito, K., Sato, M (2013). Oral corrective feedback in second language classrooms. Language Learning 46 (1), 1-40.

Mohd Noor, N., Aman, I., Mustaffa, R., & Teo, K. S. (2010). Teacher's verbal feedback on students' response: A Malaysian ESL classroom discourse analysis. In Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences (Vol. 7, pp. 398-405) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.10.054

34

Myndigheten för skolutveckling. (2008). Engelska En samtalsguide om kunskap, arbetssätt och bedömning. Retrieved from:

https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.6bfaca41169863e6a6573d7/1553960625057/pdf2057 .pdf

Nationella centret för utbildningsutvärdering. (2019). Sjundeklassarna är bra på engelska, men för en del är engelskan en utmaning. Retrieved from:

https://karvi.fi/sv/2019/05/09/sjundeklassarna-ar-bra-pa-engelska-men-for-en-del-ar-engelskan-en-utmaning/

Roothooft, H., & Breeze, R. (2016). A comparison of EFL teachers’ and students’ attitudes to oral corrective feedback. Language Awareness, 25(4), 318-335.

doi:10.1080/09658416.2016.1235580

Russel, J., & Spada, N. (2006). The effectiveness of corrective feedback for second language acquisition: A meta-analysis of the research. In J. Norris & L. Ortega (Eds.), Synthesizing research on language learning and teaching (pp. 133-164). Amsterdam: Benjamins. Russell, V. (2009). Corrective feedback, over a decade of research since Lyster and Ranta (1997): Where do we stand today? Centre for Language Studies, 6(1), 21-31. Retrieved from: http://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/v6n12009/russell.pdf

Safari, P. (2013). A Descriptive Study on Corrective Feedback and Learners’ Uptake during Interactions in a Communicative EFL Class. Theory and Practice in Language Studies,3(7). doi:10.4304/tpls.3.7.1165-1175

Shamiri, H., & Farvardin, M. T. (2016). The Effect of Implicit versus Explicit Corrective Feedback on Intermediate EFL Learners Speaking Self-Efficacy Beliefs. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 6(5), 1066. doi: 10.17507/tpls.0605.22

Skolverket. (2011). Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare. Revised 2018. Retrieved from:

https://www.skolverket.se/sitevision/proxy/publikationer/svid12_5dfee44715d35a5cdfa2899/ 55935574/wtpub/ws/skolbok/wpubext/trycksak/Blob/pdf3984.pdf?k=3984

Waring, H.Z. & Wong, J. (2009). “Very good” as a teacher’s response. ELT Journal Volume 63(3), 195-203.

Ölmezer-Öztürk, E., & Öztürk, G. (2016) Types and timing of oral corrective feedback in EFL classrooms: Voices from students. Novitas Royal (Research on Youth and

35

Appendix A

Interview Questions in English Background of participant: 1. How old are you?

2. What is your education?

3. For how long have you been teaching? 4. What grades do you teach?

‘What do teachers know about OCF?’ 5. What is your understanding of OCF?

6. Have you been explicitly instructed in how to provide OCF as part of your education?

‘What strategies do teachers enlist for implementing OCF in the classroom, why and when do they implement them, and how has their approaches changed over time?’

7. What strategies do you use when providing students with OCF?

8. According to you, what is the most important thing to focus on when providing students with OCF?

9. Do you have any directives or guidance for OCF at the school you work at (or at past schools that you have worked at that have influenced your current approach)?

10. Do you sometimes choose not to correct students’ errors? If so, why and in what context do you not correct students’ errors?

11. When do you provide students with OCF?

12. Do you provide all students with the same type of OCF, and with the same frequency? 13. What types of errors do you tend to target? Example pronunciation vs grammar.

14. Can you identify any differences regarding your OCF strategies when you started working as a teacher compared the OCF strategies that you use today?

36

‘How do teachers perceive their students’ reactions and responses to the OCF provided?’ 16. What is your impression of student reactions to the OCF they are provided? How do you think that they interpret the feedback?

17. When students are provided with OCF, can you detect any improvements regarding their language acquisition that might not have had occurred otherwise?

18. According to you, does the use of OCF always support students in their language acquisition?

19. According to you, what kind of OCF do you think is most effective on students’ language development?

20. According to you, what kind of OCF do you think is the least effective on students’ language development?

21. Do you think that there might be situations in which students can feel uncomfortable or offended when you provide them with OCF? If so, why and can it be avoided?

22. What do you think students’ general attitude is towards receiving feedback? Positive or negative?

37

Appendix B

Interview Questions in Swedish Deltagarens bakgrund:

1. Hur gammal är du?

2. Vad har du för utbildning? 3. Hur länge har du undervisat? 4. Vilka årskurser undervisar du i?

’Vad vet lärare om MKÅ? ' 5. Vad vet du om MKÅ?

6. Fick du undervisning om MKÅ under din lärarutbildning?

’Vilka strategier använder lärare för att implementera MKÅ i klassrummet, varför och när implementerar de dessa och hur har deras tillvägagångssätt förändrats genom åren?’ 7. Vilken/ vilka strategier använder du när du ger elever MKÅ?

8. Vad är enligt dig viktigast att fokusera på när du ger elever MKÅ?

9. Har skolan du arbetar på nu, eller under tidigare anställningar, gett några riktlinjer för MKÅ?

10. Väljer du ibland att inte korrigera elevers felaktiga uttalande? Om i så fall, varför och i vilka sammanhang korrigerar du inte dessa?

11. När brukar du ge MKÅ?

12. Ger du alla elever samma typ av MKÅ, och lika ofta?

13. Vilka typer av fel fokuserar du på, uttal eller grammatiska fel?

14. Kan du se några skillnader i dina MKÅ-strategier när du började arbeta som lärare jämfört med de MKÅ-strategier som du använder idag?

38

’Hur uppfattar lärare sina elevers reaktioner och respons på den MKÅ som ges?’ 16.Vad är ditt intryck av elevers reaktioner på MKÅ? Hur tror du att de uppfattar återkopplingen?

17. När elever får MKÅ, kan du upptäcka några förbättringar beträffande deras kunskapsinhämtande som annars kanske inte hade skett?

18. Anser du att MKÅ alltid stöttar elevers språkinlärning?

19. Vilken typ av MKÅ är enligt dig mest effektiv för elevernas språkliga utveckling? 20. Vilken typ av MKÅ är enligt dig minst effektiv för elevernas språkliga utveckling? 21. Tror du att det finns tillfällen då elever känner sig obekväma när du ger dem MKÅ? Om i så fall varför och kan dessa situationer undvikas?