Unprofessionalism in the

audit profession

“to be an auditor, you have to act like one...” - Pentland (1993, s. 608)

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Accounting NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonom AUTHOR: Anna Blomquist & Elin Jonasson TUTOR: Annika Yström

JÖNKÖPING May 2020

ii

Master Thesis in Business Administration, Accounting

Title: “Unprofessionalism in the audit profession” Authors: Anna Blomquist & Elin Jonasson Supervisor: Annika Yström

Key terms: audit profession, unprofessionalism, professionalism, the SIA, disciplinary cases Date: 2020-05-15

Background and problem: The audit profession have developed through the history as the auditor’s

associations has becoming rule-making bodies. Auditors has become an even more important function, which leads to greater responsibility and more obligations. Auditors are seen as a profession, and in exchange for them to perform their work they need to be seen to act in the public interest, being independent, act with integrity, having knowledge and competence and being dedicated to their work. It has also been seen in previous research that the professional appearance and behavior matters in the audit profession. Due to the scandals in the audit profession over time, the need for supervisory boards has increased. It is the Swedish Inspectorate of Auditors (SIA) that perform the supervision of the auditors in Sweden and ensure that existing rules and standards are being followed. In previous research of disciplinary cases issued by the SIA, it is seen that professional wrongdoings made by auditors was of importance. However, no previous research has investigated what types of professional wrongdoings auditors commits.

Aim: The aim of this study is to explore what manifests unprofessionalism in the audit profession.

Disciplinary cases concerning professional wrongdoings will be analyzed in order to understand how the Swedish audit profession’s supervisory body, the SIA, assesses cases that relates to unprofessional behavior.

Methodology: Disciplinary cases concerning professional wrongdoings between 2006-2019 has been

analyzed through a qualitative content analysis. The disciplinary cases have been sorted into categories concerning professional aspects that have emerged from previous research and auditor’s code of conduct. The result has been analyzed and compared to previous research and the frame of reference.

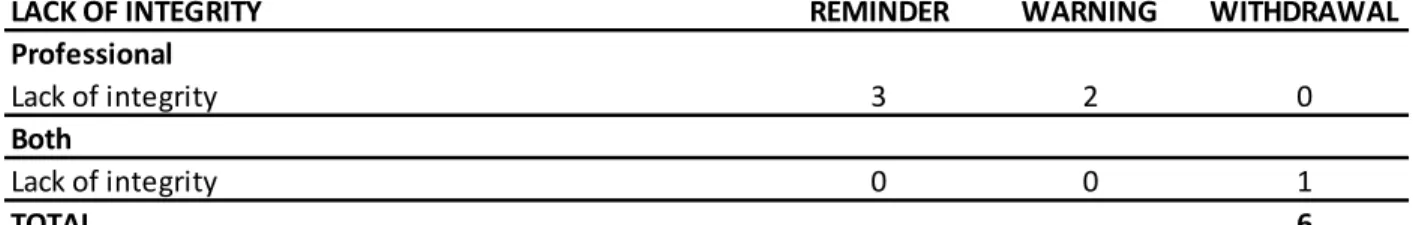

Result and conclusions: The types of professional wrongdoings the auditors commit are Lack of independence, Shortcomings in the auditor’s own business, Lack of dedication, Not fulfilled requirements, Personal shortcomings, Not act in public interest and Lack of integrity. The types of professional wrongdoings occurred most frequently was Lack of independence, Shortcomings the auditor’s own business and Lack of dedication. Lack of independence had the highest share of the total disciplinary cases issued, while Shortcomings in the auditor’s own business seem to be the most severe one as it had the largest share of withdrawal of the auditor’s authorization or approval.

Future studies: As this study only take the perspective of the SIA, it would be further interesting to see

how the auditor’s perceive professionalism and what aspects they find important in order to obtain a professional role. Hence, conducting a study from the perspective of the professionals would give a more nuanced picture of what it means being a professional. In addition, it would also be interesting to investigate how the audited client’s perceive professionalism in the audit, and what aspects of professionalism they find important in order to obtain trust for the auditor.

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank our eminent supervisor Annika Yström for all feedback during this thesis. She has been a great support to us, by always being available and showing a commitment without limits. With positivity and encouragement, she has been an invaluable support for us.

We would also like to thank the members of our seminar group, for great feedback during the process. Thank you! Jönköping, May 2020 ___________________ ____________________

Anna Blomquist

Elin Jonasson

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION ...1 1.1 BACKGROUND ... 1 1.2 PROFESSIONALISM ... 3 1.3 PROBLEM DISCUSSION ... 6 1.4 PURPOSE ... 7 1.5 STRUCTURE OF THESIS ... 8 2. FRAME OF REFERENCE ...102.1 REGULATIONS OF AUDITORS AND AUDIT IN SWEDEN ... 10

2.1.1 THE DEVELOPMENT OF AUDIT REGULATIONS IN SWEDEN ... 10

2.1.2 THE SWEDISH INSPECTORATE OF AUDITORS (SIA) ... 11

2.1.3 DISCIPLINARY CASES ... 12

2.1.4 PROFESSIONAL ETHICS FOR ACCOUNTANT (PEA) ... 13

2.2 PROFESSIONALISM ... 14

2.2.1 BEING A PROFESSIONAL ... 14

2.2.2 PROFESSIONALISM AND ETHICS ... 19

2.2.3 PROFESSIONALISM AND PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATIONS ... 20

2.2.4 “THE NEW PROFESSIONALISM“ ... 21

2.3 PREVIOUS RESEARCH ON DISCIPLINARY CASES ... 22

2.4 SUMMARY OF PROFESSIONALISM AND REGULATION ... 24

3. METHODOLOGY ...27

3.1 RESEARCH APPROACH ... 27

3.2 RESEARCH STRATEGY ... 28

3.3 DATA COLLECTION & DATA SELECTION ... 29

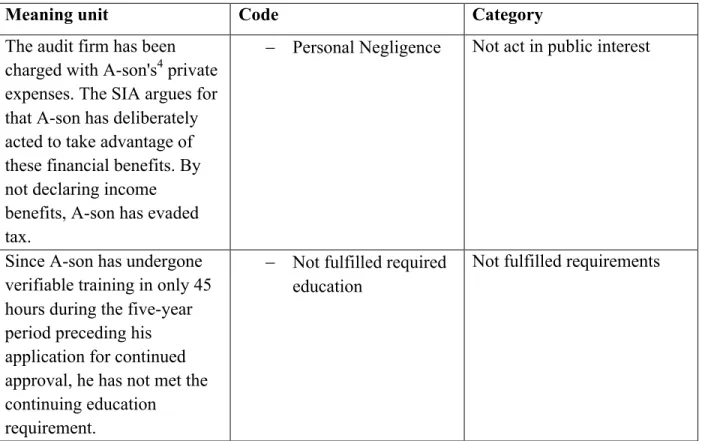

3.4 DATA ANALYSIS ... 31

3.5 RESEARCH ETHICS ... 33

3.6 RESEARCH QUALITY ... 33

3.7 SOURCE QUALITY ... 34

4. EMPIRICS & ANALYSIS ...36

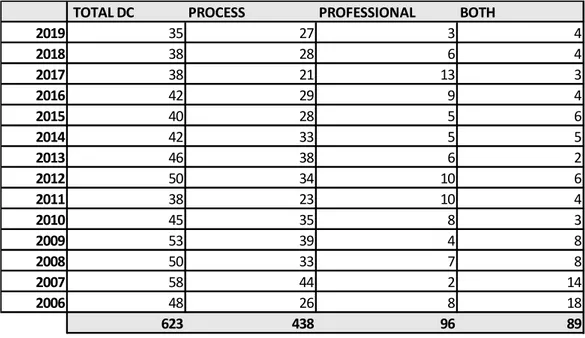

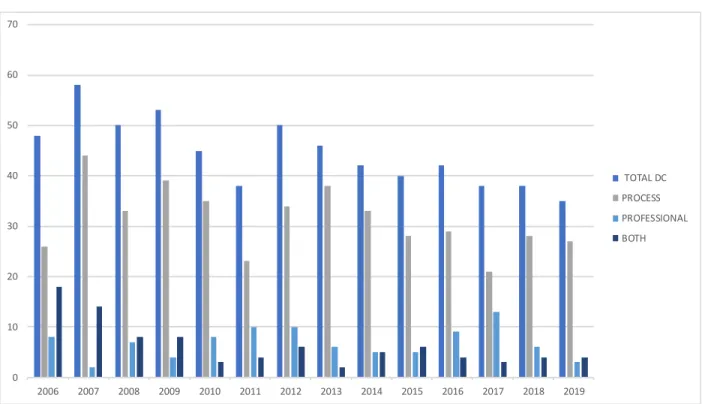

4.1 TOTAL DISCIPLINARY CASES ... 36

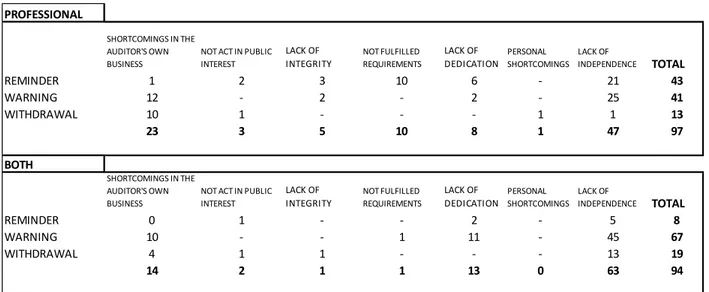

4.2 CATEGORIZATION ... 37

4.3 SANCTIONS ... 40

v

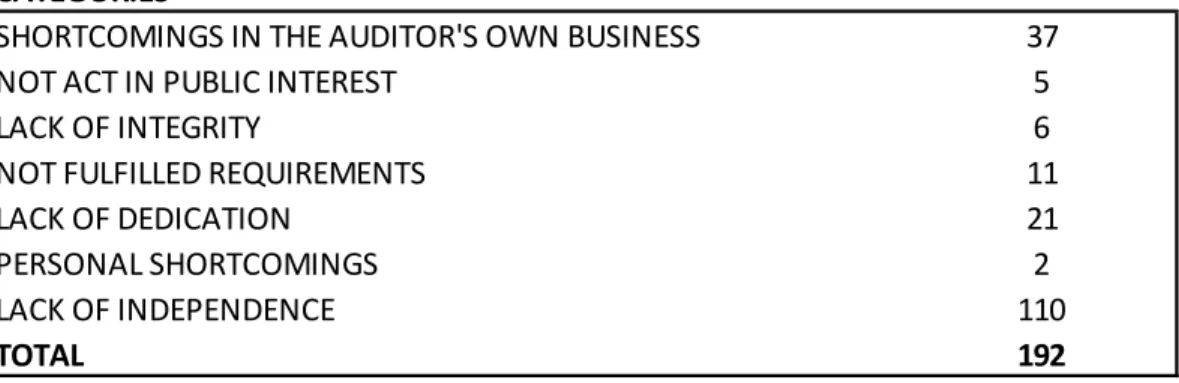

4.4.1. SHORTCOMINGS IN THE AUDITOR’S OWN BUSINESS ... 42

4.4.2 NOT ACT IN PUBLIC INTEREST ... 45

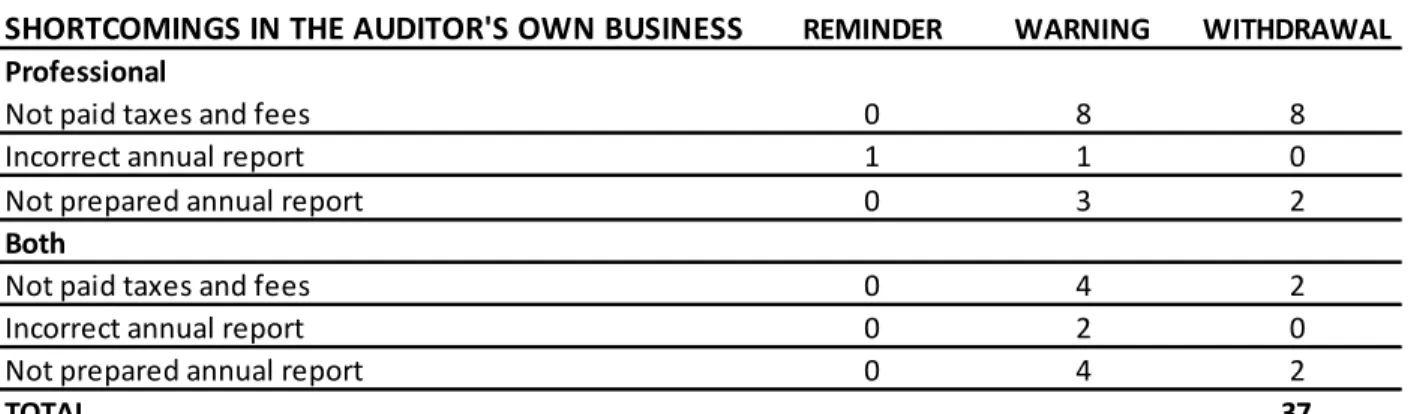

4.4.3 LACK OF INTEGRITY ... 47

4.4.4 NOT FULFILLED REQUIREMENTS ... 49

4.4.5 LACK OF DEDICATION ... 51

4.4.6 PERSONAL SHORTCOMINGS ... 54

4.4.7 LACK OF INDEPENDENCE ... 56

5 CONCLUSION ...60

5.1 CONCLUSION ... 60

5.2 CONTRIBUTION OF THE STUDY ... 62

5.3 LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY & FURTHER RESEARCH ... 63

5.4 DISCUSSION ... 64

vi LISTOFFIGURES FIGURE 1 – FRAMEWORK ... 25 FIGURE 2 – THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE CASES OVER TIME ... 37 LIST OF TABLES TABLE 1 – THE PROCESS OF CODING ... 32 TABLE 2 – DISTRIBUTION OF THE TOTAL DISCIPLINARY CASES ... 36 TABLE 3 – OVERVIEW OF SANCTIONS CONNECTED TO THE CATEGORIES ... 41 TABLE 4 – OVERVIEW OF THE TOTAL PROFESSIONAL WRONGDOINGS ... 42

TABLE 5 – CODES FOR “SHORTCOMINGS IN THE AUDITOR’S OWN BUSINESS” ... 42

TABLE 6 - SANCTIONS FOR “SHORTCOMINGS IN THE AUDITOR’S OWN BUSINESS” ... 43

TABLE 7 – CODE FOR “NOT ACT IN PUBLIC INTEREST” ... 45

TABLE 8 - SANCTIONS FOR “NOT ACT IN PUBLIC INTEREST” ... 46

TABLE 9 - CODE FOR “LACK OF INTEGRITY” ... 47

TABLE 10 - SANCTIONS FOR “LACK OF INTEGRITY” ... 48

TABLE 11 - CODES FOR “NOT FULFILLED REQUIREMENTS” ... 49

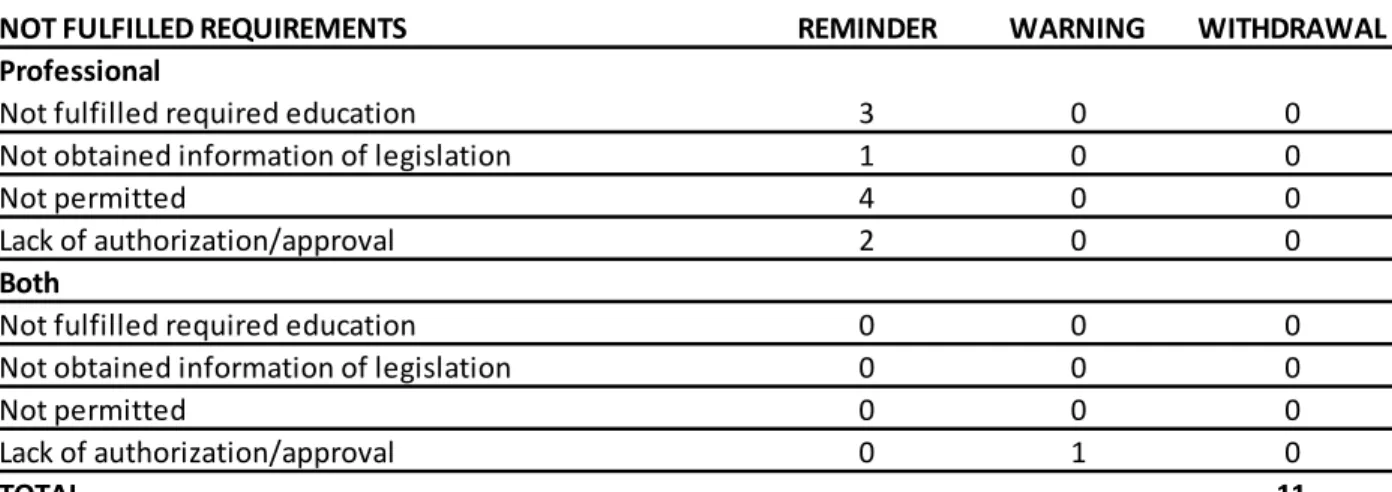

TABLE 12 - SANCTIONS FOR “NOT FULFILLED REQUIREMENTS” ... 50

TABLE 13 - CODES FOR “LACK OF DEDICATION” ... 52

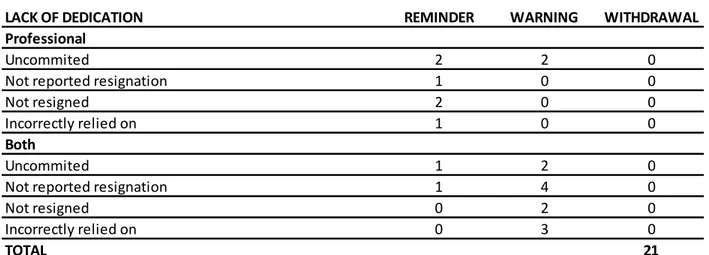

TABLE 14 - SANCTIONS FOR “LACK OF DEDICATION” ... 53

TABLE 15 - CODE FOR “PERSONAL SHORTCOMINGS” ... 54

TABLE 16 - SANCTIONS FOR “PERSONAL SHORTCOMINGS” ... 55

TABLE 17 - CODES FOR “LACK OF INDEPENDENCE” ... 56

vii

ABBREEVIATIONS

FAR Swedish Institute of Authorized Public Accountants

GAAS Generally Accepted Auditing Standard

IEASBA International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants ISA International Standards on Auditing

PEA Professional Ethics for Accountants RP Audit Process

RS Auditing Standard

SARA Swedish Annual Reports Act (1995:1554)

SCA Swedish Companies Act (2005:551)

SCRO Swedish Companies Registration Office

SEC American Securities and Exchange Commission

SIA Swedish Inspectorate of Auditors

SPAA Swedish Public Accountants Act (2001:883)

SSA Swedish Society of Auditors

SSBPA Swedish Supervisory Board of Public Accountants

STA Swedish Tax Agency

viii

TRANSLATION

Annual Reports Act Årsredovisningslag (1995:1554)

Disciplinary Board of Public Accountants Tillsynsnämnden Generally Accepted Auditing Standard God Revisionsed Professional Ethics for Accountants God Revisorsed Public Accountants Act Revisorslag (2001:883)

Stockholm Chamber of Commerce Stockholm Handelskammare Swedish Companies Act Aktiebolagslag (2005:551)

Swedish Companies Registration Office Bolagsverket Swedish Inspectorate of Auditors Revisorsinspektionen

Swedish Institute of Authorized Public Accountants Föreningen Auktoriserade Revisorer Swedish Society of Auditors Revisorsamfundet

Swedish Supervisory Board of Public Accountants Revisorsnämnden

1

1.

INTRODUCTION

In this section, background to the research problem is presented together with an overview of the concept of professionalism. The problem formulation and the purpose of the study is then formulated.

1.1 BACKGROUND

In the end of 19th Century companies in Great Britain sought capital by selling shares in the companies. Almost a third of all the companies went bankrupt (Carrington, 2010a). The solution of this problem was to introduce audit of financial statements. In Sweden, the first regulation of audit in certain companies was introduced in 1895, without requirement of special education of the auditor or its independence (Wallerstedt, 2009) and in the same year the first organization for auditors was founded, Swedish Society of Auditors (SSA). The purpose of the foundation was to increase the status of the audit profession, i.a. through regulation (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). In 1897 it became mandatory for public companies in Sweden to have approved or authorized auditors (Carrington, 2010a).

Until today the view of the purpose of the auditor has changed from originally discover fraud towards the idea of “examination” (Power, 2003). The Kreuger crash in Sweden had a great impact on the audit profession, and the crash enhanced the flaws in the regulation of the auditors’ ethics, i.a. regarding independence (Wallerstedt, 2009). Therefore, the need for ethics regulation became clear.

In 1932, the Swedish Institute of Authorized Public Accountants (Föreningen Auktoriserade Revisorer, henceforth called FAR) was formed (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). The first rules were introduced in 1933 by FAR’s members but was rewritten the following years. A couple of years later after the formation of FAR, discussions about the regulation of ethics of the profession of auditors emerge again (Wallerstedt, 2009). At first, the rules concerned how auditors acted collegially within the profession, to later focus on the auditor’s behavior towards third parties and the development of generally accepted auditing standards (GAAS) (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). In 1942 the content of code of ethics was expanded to 15 principles which included professional conduct in the profession (Wallerstedt, 2009). The introduction of the ethic regulations became an important milestone to enhance the audit profession in Sweden (Öhman & Wallerstedt, 2012). In

2

1977, Generally Accepted Auditing Standard (GAAS) and Professional Ethics for Accountants (PEA) was introduced by FAR (Wallerstedt, 2009).

It is stated in the SPAA (Swedish Public Accountants Act 2001:883) 19§ that: “an auditor must

comply with Professional Ethics for Accountants”. It is FAR that establish the ethical code in

Sweden, which is based on the International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IEASBA):s Code of Ethics. The Code of Ethics are principle based (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013) and comprises of five main pillars: integrity, objectivity, professional competence, confidentiality and professional conduct.

Since auditors act in trust, it is of considerable importance that they do not abuse that trust (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). The SCA (Swedish Companies Act 2005:551) states: "The auditor shall, to

the extent that generally accepted auditing standards declare review the company's annual report as well as the accounts and the administration of the board and the CEO" (ABL 2005:551). GAAS

requires planning of the audit process, allocation of competence and performance of the auditor's assignment together with the reporting and documentation of the audit assignment (Mannheimer, 1981).

Following the scandals occurred during the development of the audit profession where the reason has been shortcomings in audit quality, the need for supervisory boards has increased (Eilifsen & Willekens, 2007). Since 1995 the Swedish Inspectorate of Auditors (SIA)1 was assigned to perform supervision of the auditors in Sweden and ensure that the existing rules and standards are being followed. The SIA’s surveillance should be based on a general and objective point of view. When the audit contains errors, the SIA assigns disciplinary actions in the form of a reminder, warning or withdrawal of the auditor’s authorization or approval (Sevenius, 2019). However, the relationship between the auditors and the SIA has been criticized in media, and it has been debated what requirements can be imposed on the authority for it to act as a support rather than as an impediment (Träff, Clemedtson & Brännström, 2005).

The auditing profession with the role and assignments that an auditor has today, has developed and strengthened through the history when auditors’ associations became rule-making bodies

3

(Öhman & Wallerstedt, 2012). Hence, the auditor has become an even more important function in society, which has led to greater responsibility as well as more obligations (FAR, 2006).

1.2 PROFESSIONALISM

Professions belongs to the more debated and difficult subject in social science (Brante, 2005). One reason for the interest of professions is that we today are seen to live in a knowledge society, and professions are carriers of the knowledge (Brante, 2005). Professions’ motives and interests has been discussed over the years, and many definitions of what constitutes a profession has derived from different social theories. According to Brante (2005) these definitions are difficult to operationalize in empirical research. The broad definition of who are included in the concept or not becomes a political matter. He claims that a broader definition of the concept should include abstract knowledge, uncertainty/risk relation, trust, exchangeability and access. However, the aim of this study is not to define whether audit is a profession or not. Professionalism is not about only possessing knowledge or expertise in a certain area but also to use this knowledge in compliance with ethical norms (Suyono & Al Farooque, 2019).

The concept of professionalism has been discussed in previous research. One crucial aspect for professions in general is that they must be seen to act in the public interest (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). According to Evetts (2003) professionalism expects professionals to be worthy of trust, to maintain confidentiality and conceal guilty knowledge by not exploiting it for evil purposes. In return for professionalism in client relations, professionals are rewarded with authority, privileged rewards and higher status (Evetts, 2003). A crucial aspect of auditor’s professionalism is independence (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013; Hall, 1968; Broberg, 2013). For the auditor to perform his or her work in a credible manner and obtain confidence for the audit report, the auditor must be objective in his or her opinions and not be affected by external pressure. Another aspect of professionalism is that people outside the profession cannot assess or decide the quality of the auditor’s work (Hall, 1968; Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). Compared to other professions, auditors cannot illustrate a material result of their performance as their final product is the audit report. The public have no other option than to trust the audit report, and in order for auditors to legitimize this they need to be seen to act in the public interest (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). Further, the professional association have an important role to fulfil in protecting the profession's domain (Greenwood, 2002). By creating rules and norms and monitoring the individuals in the profession, the profession will gain legitimacy from society (Greenwood, 2002).

4

The society has strict expectations of what an auditor must do in state and legal sense and that the auditor consistently will comply with the applicable audit regulations (Mannheimer, 1981). Also, it exists a preconception of how an auditor should act. Pentland (1993) expressed it as: “to be an

auditor, you must act like one...”, and equates the status of an auditor with the status of a priest. It

becomes important for an auditor to follow the norms the society has implemented, and display the right behavior is decisive in order to obtain professionalism (Pentland, 1993). It is discussed that the professional appearance of the auditor is not only to dress properly, but also how they talk and present themselves. According to Anderson-Gough, Grey & Robson (2002) even the handshaking and signing one’s name matters. The auditor’s commitment to work reflect their role, like taking short lunch breaks, the positivity to work overtime and not prioritize their private life is a part of the professional appearance of the auditor. Thus, the description of how an auditor is expected to be is more allocated in appearance and attributes rather than the knowledge they possess (Anderson-Gough et al., 2002). Attributes such as long working hours, dress codes and commitment to work legitimize the professional aspiration in terms of appearance and conduct to greater extent than other professions (Pentland, 1993; Anderson-Gough et al., 2002). However, the prerequisite for the audit profession is knowledge, independence and confidentiality and to follow the principals of PEA (Träff, et al., 2005).

Criticisms towards the audit profession arises during scandals which gets strong attention in the media. The problem, however, is that it is not only the individual auditor who are held accountable in the media, but the profession as such and its relationship with other actors are also questioned (Carrington, 2011). Among other things, the relationship between the auditors and the SIA has been criticized (Carrington, 2011). In order for the audit profession to maintain and gain trust, they are expected to assume their responsibilities and act responsible. Dietz & Den Hartog (2006) claims that when distrust exists, behaviors are controlled by sanctions and threats. Therefore, it is of most important to have a system of sanctions that is considered reliable to maintain the trust. Previous research involving disciplinary cases has studied the errors committed by auditors and the type of errors the supervisory body considers more serious (Brown & Calderon, 1993; Campbell & Parker, 1992; Carrington, 2010b; Andersson & Selmosson, 2011). Findings from these studies shows that professional wrongdoings seem to be considered more serious to the regulatory body, than when the auditor is committing a technical error. For this reason, it becomes

5

further interesting to investigate disciplinary cases with focus on cases where professional wrongdoings have occurred.

Carrington (2010b) investigated the concept of a sufficient audit, where he sought to answer the question how the audit process and professionalism interrelates in order to obtain a sufficient audit. He investigated the disciplinary cases by the SIA between 1995 and 2003. Carrington’s study (2010b) showed that the supervisory body consider professional appearance to be of importance. Moreover, Carrington highlighted the difference between the consequences of the punishment given to auditors. A withdrawal of authorization or approval can be considered more devastating for the individual auditor, as the career in auditing ends. If an auditor receives a reminder or a warning it has no direct consequence, except from the possible “shame”. Although, the disciplinary cases published from SIA are anonymous. Carrington (2010b) argue that since the users of financial statement has no other option than trusting the auditor the display of professional behavior becomes important.

Carrington (2010b) categorized professional wrongdoings in five sub-categories: “lack of independence”, “shortcomings in the audit organization”, “failure to cooperate with, or resist, the SIA’s investigation”, “not registered with, or paid the fee to, the SIA” and “unprofessional conduct”. The last-mentioned category, unprofessional conduct, was described as behaviors and actions where the auditor was considered to have act unprofessional but was not related to independence, the organization or the auditor's interaction with SIA. These errors can be present even though the auditor followed standards and rules, and the audited financial statements does not necessarily contain errors for this type of wrongdoing to occur (Carrington, 2010b). However, it is not specified what this category of error contains more precisely except for one example of a case where the auditor was being threatful towards the client an. Yet, 71 cases in this category occurred between 1995-2003 (Carrington, 2010b). This category also had a large proliferation of different punishment in the study, which lead us to the question: what consider SIA to be unprofessional behavior? Can an unprofessional behavior of the auditor lead to a withdrawal of the authorization or approval in one case, but only a warning in another? How unprofessional can an auditor be to only receive a reminder? Our study will process these types of questions, by investigating what level of professionalism the SIA considers low.

6

1.3 PROBLEM DISCUSSION

Research within professions have had difficulties to give an exact definition of the study object, and it is difficult to find the internally and externally distinctive characteristics (Brante, 2005). Auditors in Sweden have an ethical code to follow and must comply with PEA to perform their work in a professional manner. However, we can see from previous research that professional failures still occur (Carrington, 2010b). It exists studies that explore what constitutes professionalism (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013; Broberg, 2013; Pentland, 1993; Grey, 1998), but not when the professionalism fails. The previous research that has examined disciplinary cases has not gone deeper into what constitutes auditor’s professional failures. Furthermore, Broberg (2013) suggest that if auditors work under too much influence of supremacy and collective aspects, the auditors might not reflect themselves on what it means being a professional, and hence their professionalism might be undermined. It therefore exists a need to concretize the concept of professionalism, and what aspects of professionalism that are included in the audit profession. A way to provide more knowledge in the concept of auditor’s professionalism is to look at when auditors fail in their professional role, thus by examining unprofessionalism.

Understanding when one has violated rules and standards could be considered uncomplicated for the individual, and the judgement whether a rule or standard has been violated or not ought to be objective. The reasons that process wrongdoings occur can have several explanations. The individual might be aware of the error, or the error was not committed intentionally. Professional wrongdoings, however, is about assessments and “doing the right thing”. The assessment whether a professional wrongdoing has been committed can be considered more subjective. Further, in some disciplinary cases the punishment is so severe that the auditor’s authorization or approval is withdrawal which leads to serious consequences for his or her career. Although, in some cases the punishment is only a reminder or warning that has no direct consequences for the auditor (“a slap on the hand” as Carrington (2010b) expressed it).

For this reason, it becomes interesting to investigate how SIA argues for the decisions in the disciplinary cases, and how they resonate of what is unprofessional behavior and if it exists a grey zone in what unprofessionalism is.

7

Professionalism is an abstract concept according to previous research. However, as far as we know, no studies have attempted to define what constitutes professionalism based on what is not

professionalism. One way to concretize the concept is to study disciplinary cases where

the supervisory body assess auditors to act unprofessional. In order to understand what manifests the concept of professionalism, our study will contribute to the understanding of the concept of professionalism by looking at what is not considered professional behavior, i.e. unprofessionalism.

1.4 PURPOSE

The aim of this study is to explore what manifests unprofessionalism in the audit profession. Disciplinary cases concerning professional wrongdoings will be analyzed in order to understand how the Swedish audit profession’s supervisory body, the SIA, assesses cases that relates to unprofessional behavior.

8

1.5 STRUCTURE OF THESIS

The overall design of the study will be presented below, where a brief description of each chapter is given.

Introduction

In this chapter, background to the research problem is presented together with an overview of the concept of professionalism. The problem formulation and the purpose of the study is then formulated.

Frame of reference

In this chapter, the study’s theoretical framework is presented. The chapter begins with a presentation of the development of regulations in Sweden together with a review of the role of the SIA and the disciplinary cases as well as Professional Ethics for Accountant. Thereafter, professionalism is presented with a starting point of a profession in general to the audit profession together with what constitutes professionalism and professional associations. The chapter concludes with a brief summary of the framework.

Methodology

In this chapter, the chosen method is presented. Here the abductive research approach is explained. The research strategy of a qualitative method is presented, followed by an explanation of the choice of a qualitative content analysis. The process of the selection of data which consists of disciplinary cases is then elaborated, and further the process of collecting the data is explained. Furthermore, the approach to qualitative content analysis is explained in detail with an example of coding the data. Finally, a presentation of how the authors considered research ethics and research quality in the quality is presented.

CHAPTER1

CHAPTER2

9

Empirics & Analysis

In this chapter, the result of the study will be presented and analyzed. Initially the result has been presented into the two different wrongdoings, process and professional and then professional wrongdoings has been categorized which will be analyzed and discussed. Lastly, the sanctions to the different errors will be analyzed. All the given parts will be investigated and reconnected to the frame of reference.

Conclusion

In the last chapter, the conclusions of the empirical findings and analysis is presented to answer the study’s purpose. Further, the study's limitations and proposals for further research on the concept of professionalism is presented. A discussion of the analysis is presented with the interpretations made by the authors.

CHAPTER4

10

2.

FRAME OF REFERENCE

In this chapter, the study’s theoretical framework is presented. The chapter begins with a presentation of the development of regulations in Sweden together with a review of the role of the SIA and the disciplinary cases as well as Professional Ethics for Accountant. Thereafter, professionalism is presented with a starting point of a profession in general to the audit profession together with what constitutes professionalism and professional associations. The chapter concludes with a brief summary of the framework.

2.1 REGULATIONS OF AUDITORS AND AUDIT IN SWEDEN

2.1.1THE DEVELOPMENT OF AUDIT REGULATIONS IN SWEDEN

The development of the framework for auditors in Sweden is closely connected to the emerge of the SCA. In the period of 1848 - 1895 the SCA established a framework for a further use of the limited company (Wallerstedt, 2001). This led to an ownership with freedom from responsibility for the company's commitments, and a minority ownership without direct transparency or control. In the SCA from 1895, the first statutory requirements for auditing were introduced. In 1899 the first organization for auditors were formed, Swedish Society of Auditors (SSA), with the focus to increase the status of the auditor and the audit i.a legislation (Wallerstedt, 2001).

In 1912, the initial requirements for becoming an authorized auditor of Stockholm Chamber of Commerce was to have a degree from the Stockholm School of Economics, be 25 years old and have had three years’ practice under supervision of an authorized public accountant (Wallerstedt, 2001). However, later it became obvious that the requirements needed became a barrier to entry into the profession, which contributed to a slow growth in the population of authorized public auditors in Sweden (Wallerstedt, 2001). Discussions arise whether the SRS should be able to decide to authorize auditors themselves. In 1922, the SSA sent an official letter to the government and requested that the government should take over the authorization procedure, however they did not fulfil their intention. A year later in 1923, FAR, an organization exclusively for authorized auditors was formed (Wallerstedt, 2001).

In 1930, the Central Board of Auditing that was established in 1919, formed a committee that presented a proposal to establish an official recognition for auditors with lower qualifications than the authorized auditors. From then on there were two kinds of auditors selected by the Stockholm Chambers of Commerce: authorized public auditors and registered auditor (Wallerstedt, 2001).

11

In the SCA from 1944, the authorized auditor was supported with a protected market. The law implied that listed companies and not listed companies required at least one authorized auditor. The duties and competences of the authorized auditor were also regulated by the law and the auditing profession in Sweden was emerging. When the supply of qualified auditors was able to match the demand in 1983, the legislation was revised and established that all limited companies should be audited by an authorized or approved auditor (Wallerstedt, 2001). The audit process (RP) was adopted in 1990 by the FAR board. It was based on principles, rather than detailed rules and provided a great room for professional judgment (Agevall & Jonnegård, 2013).

During the 1980s, authorization and control of the auditor passed from the Stockholm Chambers of Commerce to the state; later, under the SIA in 1995 in connection with Sweden's entry in the EU. The Swedish rules got adopted to EU regulations, “International Standards on Auditing” (ISA) which became mandatory for the union. The aim was to ensure a trustworthy and consistent audit regardless in which country the company is audited (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). RP2 got replaced with the Swedish translation of ISA, the Auditing Standard in Sweden (RS) in 2004 (Larsson, 2005). The RS led to that the audit became more time-consuming and therefore more expensive. More documentation and quality assurance of the audit work is also required (Halling, 2004). On the other hand, FAR believed that the new RS3

would strengthen the confidence for auditors in the society. From 1 January 2011, Sweden complies with ISA as a whole (Lennartsson, 2011).

2.1.2THE SWEDISH INSPECTORATE OF AUDITORS (SIA)

The SIA, formerly Swedish Supervisory Board of Public Accountants (SSBPA), founded in 1995, is the authority with the purpose of monitor authorized and approved auditors as well as registered audit firms while auditing and authorizing auditors. Their focus is to ensure that GAAS and PEA are developed in an appropriate manner and that there are adequate auditors in the society who will perform high audit quality in addition to live up to high professional ethical requirements (Revisorsinspektionen, 2020a).

2 Revisionsprocess

12

According to a new regulation with instructions for the SIA, 3§ (Regulation 2007: 1077), the decision-making body named the Disciplinary Board of Public Accountants within the authority decides on disciplinary actions. Regarding the supervision of qualified auditors and registered audit firms, a disciplinary case can be initiated through different approaches (Revisorsinspektionen 2020b).

When, for example, something has been noticed in the media, or the SIA assesses that there are other factors of risk, an investigation is made about whether or not to start a disciplinary case, a risk-based supervision (Revisorsinspektionen 2020c). There is also a possibility that external people submit notifications to the authority, which also begins a disciplinary case on cause of mistrust of the quality of the audit (Revisorsinspektionen 2020a). The Supervisory Board's decision is then published as a practice (Revisorsinspektionen 2020d).

In the SPAA 32§ (2001:883) its further states, the SIA has three different disciplinary actions;

reminder, warning or withdrawal of the auditor’s authorization or approval. According to 32§ of

the same law, the choice of action is considered how serious a neglect is, for how long it has been going on and the degree of responsibility of the person who has committed the neglect. The SIA explains that a reminder involves a note of the fulfillment with GAAS or PEA, while a warning relates to more serious phenomena. Withdrawal of the auditor's authorization or approval only occurs if, for example, the phenomena are repeated or is of an aggravating nature. If there is no reason for further action, the case is then closed (Revisorsinspektionen 2020c).

2.1.3 DISCIPLINARY CASES

A disciplinary case opens when the SIA receives a notification from a company, a private person or an authority. Disciplinary cases can also be opened without notification from a stakeholder. In these cases, they are opened because of, for example, information in the mass media or because information has emerged in connection with the authority supervision and quality control. The report must contain information about who the report applies to, a description of the case and information about how the auditor, according to the notifier, has disobey his or her obligations. Furthermore, the period of validity should be specified when the SIA does not deal with cases more than five years back in time from the time the auditor became aware of the case. The handling of disciplinary cases is normally written (Revisorsinspektionen 2020e).

13

When a notification results in the opening of a disciplinary case, the auditor has the right to speak. Following, the SIA takes a stand on whether further investigation is needed, such as supplementary information or comments, or whether the case is fully investigated. If it cannot be shown that the auditor has disobeyed his or her obligations, the case is written off. However, if the SIA comes to the decision that an auditor has made a failure, a disciplinary action is notified in the form of a reminder, warning or withdrawal of authorization or approval. A reminder is a remark that an auditor has not followed GAAS or PEA. A warning is a penalty that is used when the neglect is so severe that it can be assumed to result in the withdrawal of the authorization or approval if repeated (Revisorsinspektionen 2020e).

2.1.4 PROFESSIONAL ETHICS FOR ACCOUNTANT (PEA)

In accordance with the SPAA 19§, auditors must follow PEA when performing an audit. The development of Swedish auditor’s practice is strongly influenced by foreign standards. Swedish PEA rests on three pillars (Eklöv-Alander, 2019):

• Independence: an auditor should protect integrity, be objective and adopt a professional and skeptical attitude.

• Competence: the auditor must have knowledge of and experience in accounting and relevant financial conditions and have an auditor's degree.

• Confidentiality: an auditor may not pass on information received by virtue of his assignment if it could be detrimental to the company.

Auditors also have ethical rules to adhere to, in complement to the regulations. The SIA has determined that section 110 of IESBA’s Code of Ethics applies to the application of PEA (Eklöv-Alander, 2019). The starting point in the Code of Ethics is that auditors work in the public interest (IESBAs Code of Ethics). The IESBA has described what is required of auditors in order to serve the public interest, and what requirements this place on auditors in their professional practice. These ethical standards include five main principles, that are presented below:

“110.1 A1 There are five fundamental principles of ethics for professional accountants: (a) Integrity – to be straightforward and honest in all professional and business relationships

14

(b) Objectivity – not to compromise professional or business judgments because of bias, conflict of interest or undue influence of others.

(c) Professional Competence and Due Care – to:

(i) Attain and maintain professional knowledge and skill at the level required to ensure that a client or employing organization receives competent professional service, based on current technical and professional standards and relevant legislation; and

(ii) Act diligently and in accordance with applicable technical and professional standards.”

(d) Confidentiality – to respect the confidentiality of information acquired as a result of professional and business relationships.

e) Professional Behavior – to comply with relevant laws and regulations and avoid any conduct that the professional accountant knows or should know might discredit the profession” (IFAC,

2018).

These are the five fundamental principles of IESBA:s Code of Ethics, which auditors are expected to apply in their work practice (Eklöv-Alander, 2019).

2.2 PROFESSIONALISM

2.2.1BEING A PROFESSIONAL

Over the years, there has been many definitions of a profession (Brante, 2005). Many attempts have been made at defining the concept of profession, mainly based on social theories. From the functionalistic perspective, professions are seen altruistic and act in the public interest (Brante, 2005; see Parson, 1939). However, this perspective became criticized. This criticism derived from the Weberian perspective, where opponents claimed that professions are not altruistic and do not act in the public interest. Instead enhanced the professions self-interest where professions are used to gain monopoly in certain areas in order to create power and to maximize self-interest by using education to legitimize this (Brante, 2005). Brante (2005) however suggests that the definition of a profession should not involve the motives or interests of the profession. Further, he also claims that a complete definition of a “profession” cannot be obtained.

15

However, in this study we do not aim to investigate whether audit is a profession or not. Auditors are seen as a profession (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013) and Broberg (2013) claims that the importance is not whether an audit is seen to be a profession or not today, but whether auditors are expected and/or perceived to be professionals. As auditing has traditionally been perceived as a profession, it is a notion that matters in order to understand the audit work today (Broberg, 2013). While a profession is a work that meets the academic criteria, professionalism is an ethical attribute that is independent of if the work is a profession or not (Suyono & Al Farooque, 2019). In general, professionalism is not only about to have the expertise or knowledge to complete a certain task but also to do it in compliance with ethical norms (Suyono & Al Farooque, 2019). In the social model, professions are seen as emerging to serve the public interest and gain status by society because of their performed functions (Reynolds, 2000). The primary characteristics of a profession are in general that a profession involves skills that is based on theoretical knowledge; the profession is organized and is represented by an association of distinctive character; and integrity is maintained by adherence to a code of conduct (Reynolds, 2000; see Millerson, 1964 and Kultgen, 1988). Further, it exists characteristics that relates to the profession’s relation to society. This includes that professionals are acting in the public interest, that the professional service is indispensable and that the professionals are independent (Reynolds, 2000). The discussion of professions and professionalization has usually been based on the assumption that certain attributes and characteristics that distinguish features of professions (Espinosa-Pike & Barrinkua, 2017). The most common attributes of professions are autonomous professional organizations, special skills and knowledge, accreditation and code of ethics (Espinosa-Pike & Barrinkua, 2017).

Mautz (1988) argue that there exist two groups of professionals. One that complies of experts, that want to give the best service to clients and maximize the revenues over time. The other group has the same expertise and motivation, but the members act in the public interest. In return they will receive monopoly in their area of expertise and a social contract is established. Mautz (1988) also argue that the qualifications of this type of profession includes having a definable body of knowledge, specialized education, a formal organization, a code of ethics, standard of practice, procedure for disciplining members and public acceptance. Many of these qualifications are according to Mautz (1988) subjective, and it can lead to a debate of what occupations that is included in this definition of a profession. Professions have an exclusive franchise from society,

16

and a sole right to perform a specific service. Since society has accepted the profession’s right to perform the specific services, society expects the professionals to act in the interest of society (Mautz, 1988).

Hall (1968) argues that professionalism includes five aspects. One aspect is dedication to the profession, which refers to the dedication the professional has for his work even if there is a lack of extrinsic rewards. Social obligation is the feeling of acting in the public interest, and professionals must be independent and be able to make decision without external pressure. Further, Hall (1968) argues that professionalism includes confidence in the profession, which refers to that the work of the professional can only be assessed by others in the profession. Finally, professionalism includes joining formal organizations and relationships with colleagues that creates knowledge and professional awareness.

These aspects are also in line with what Broberg (2013) suggests is included in professionalism. Broberg (2013) investigated the auditing concept by focusing directly on the work of the auditors through a case study of auditors in Big 4 firms. She found that professionalism includes three categories of concern. The first is auditor attitude and approach, and relates to auditors having integrity, being independent, impartial and sceptic. It includes the auditor to being responsible, courageous and interested and devoted. Further, it is important that the auditor is loyal to the role. The second category refers to the auditor having knowledge and competence. It is important for auditors to have the social skills it takes to discuss with clients and colleagues and to interact with different kinds of people. The last category included audit behavior, meaning that auditor must act in an appropriate manner and having appropriate appearance. Broberg (2013) also found that professionalism was strongly associated with professional judgement.

Independence and autonomy of control are the core characteristics of the accounting profession (Carrington, Johansson, Johed & Öhman 2013). Compared to the average employee who tries to not be corruptly influenced, auditors have an obligation to resist corrupt influence in his work (Warren & Alzola, 2008). In general, it can be said that independence is equated with the fact that the auditors in their work and in their opinions are objective and independent in relation to their current and potential clients (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). That the auditor is independent in relation to the client is a prerequisite for the auditor to be able to carry out his audit of the company in a credible manner and for the market participants (and others) to be able to have confidence in

17

the audit report. That the auditor should be independent has therefore long been regulated as well by law as by professional ethical rules (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). Society expects the auditor to be trustworthy in their work and provide reliable accounting reports. This is important for society, as the financial market depends on the reliability of the accounting reports. Independence hence plays an important role for the function of the economic system (Warren & Alzola, 2008). Professionalism also includes professional appearance and physical attributes. There are several studies (Pentland, 1993; Grey, 1998; Anderson-Gough et al., 2002) where findings showed that the audit profession is more about appearance, behavior and conduct rather than knowledge. Auditors seek to produce comfort in the audit process which in turn produces comfort for the society, and they can trust that the audit is done in a correct way (Pentland, 1993). The audit must also be done by the right people in the audit team, and the auditor’s signature is seen as a sacred symbol that ensures that the audit is complete (Pentland, 1993). Professional conduct plays a major role and being a professional includes behavior as much as technical competence and knowledge (Grey, 1998). Professional appearance includes attributes such as dress codes and commitment to work (Anderson Gough et al., 2002; Pentland, 1993; Grey, 1998). Although, this does not mean that knowledge is irrelevant (Grey, 1998).

Carrington (2010b) investigated the concept of sufficient audit from the SIA’s point of view, by investigating disciplinary cases in Sweden. His findings showed that professional wrongdoings were seen to be more serious than process wrongdoings. In line with Anderson- Gough et al. (2002), he concluded that since auditors possess a weaker knowledge base compared to other professions, professional behaviour becomes more important. Also, the auditor cannot show off a material result of their work (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). Compared to an engineer who creates a construction which can be assessed by the material result, the auditor’s material result is only the audit report. People outside the profession cannot assess the quality on the audit report, and the outsiders can only trust that the quality of this is sufficient (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). In order to legitimize the fact that people outside the profession cannot assess the quality of the professional’s work, the professional must be seen to act in the public interest (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013).

From these studies we can draw the conclusion that professionalism for the auditor includes conduct and appropriate behavior in order to legitimize themselves and gain confidence from

18

clients and other external parties because of their rather weak knowledge base. From the perspective that professions act in self-interest, the reason for them to gain legitimacy is to obtain their monopoly on their area of expertise in society (Erlingsdottir & Jonnergård, 2012) and thus get status and relatively high income.

Legitimation refers to the process by which professions justify its existence to the public, the state and other institutions (Neu, 1991). The auditing profession has an interest to maintain trust and uses four sets of practices that helps to maintain trust from society: professional entrance requirements, maintenance of professional technology, “good works” activities and disciplinary activities (Neu, 1991). Disciplinary activities are important since they are necessary for the image of the audit professions self-regulation, and they also fulfil a stigma management function (Neu, 1991). The educational requirements have three purposes. It convinces the public that they are professionals, and that they are legitimate experts in the area. It also creates a homogeneity of the “product”. Finally, it also convinces the public that auditing has legitimacy as other professions, such as law and medicine (Neu, 1991). Society trust professionals to use their knowledge in a socially responsible manner. In return for this, professionals receive higher salaries, high social status and control over their area of expertise (Neu, 1991).

According to Brante (2005), the trust for the profession is maintained through the emphasis on ethical codes, strict professional integrity and disciplinary mechanism by altruism. This also means, that only others in the profession can assess the competence of the individual professional and therefore it is important that the profession have confidence. The confidence is then strengthened through strict professional integrity and the establishment of ethical committees. The research previously examined explains the direct interaction between society and the auditors and how society perceive the audit profession. To investigate how the regulatory body in Sweden assess unprofessionalism, the focus of this thesis will lie on the role of the professional associations (the supervisory body) and how they assess disciplinary cases regarding unprofessionalism. However, we believe that in order to understand the concept of professionalism it is relevant to also examine the concept from the direct interaction between external parties and auditors.

19

2.2.2 PROFESSIONALISM AND ETHICS

Pasztor (2015) claims that ethics is not necessarily something that means the same to everyone but is rather something that is personal. Ethics is often something one see as rules, because basically all organizations have their own rules of ethics. Ethics are not emotions, laws and rules, religion or science. Ethics in a profession demands professionalism and includes for example that one has sufficient professional skills for the task one takes on. It is considered unethical to take on task that one does not have the skills to handle (Egidius, 2011). The client sacrifices his or her integrity when hiring the professional, and in exchange the client requires full confidence in the people they hire. As a professional you are required to have a sense of what is ethical. Although, it can be discussed whether this is something that is evident from the ethical requirements of the professional organization or if it something one should be aware of (Egidius, 2011).

It exists a contract between the professions and the society, and they uphold their responsibility by establish a code of conduct (Reynolds, 2000). The purpose of a profession’s code of ethics is to gain legitimacy to the profession, and to provide guidance for ethical conflict resolution (Reynolds, 2000; see Sawyer, 1991)

Pasztor (2015) argue that ethics is personal and is something that the individual must reflect on. There is a difference in defining what is ethically right, compared to following the rules and norms that an organization demands to be followed (Pasztor, 2015). Suddaby, Gendron & Lam (2009) argue that much of the critique of professional ethics has focused on the individual professional. Their result showed that this is inaccurate, and instead ethics must also focus on the way which professional work is organized in order to address the seriously ethical issues in professional service firms (Suddaby et al., 2009).

Strictly adhering to given regulations and norms can be directly unethical, as one exits one’s moral responsibility by saying one has only followed rules and norms. The more laws and regulations laid down by the state, authorities and organizations, the less the need for precise ethical codes in professional organizations and the less the general principles of humanity found in interaction ethics are needed (Egidius, 2011). From the perspective of the audit profession, Broberg (2013) claims that if auditors work under too much influence of collective aspects of discipline, they will not act as professionals and hence not develop as professional. She proposes that auditor’s professionalism will be undermined if auditors are not given enough freedom and space to act and

20

develop as professionals (Broberg, 2013). Broberg (2013) states that because supervisory bodies, regulators, associations, and in particular the accounting firms create the rules of the audit profession they emphasize the matters that are important for professionals to define themselves. By letting the system decide what it means to be a professional, the individual auditor might not reflect on what being a professional implies, as more individual engagement would lead to. She claims that reflection on an individual level is important for the process of professionalism (Broberg, 2013).

2.2.3 PROFESSIONALISM AND PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATIONS

Professional associations play a crucial part in gaining legitimacy (Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013). One characteristic of a profession is that the profession organizes themselves (Broberg, 2013). According to Greenwood, Suddaby & Hinings (2002), the role of the professional associations is creating and maintaining the professional identity. They suggest that professional associations are important for three reasons. First, the professional associations are arenas where the professionals interact and create collective representations of themselves. Professional associations encourage professional development and interactions with their members which leads to a collective self-presentation, that enables and reproduces the profession's shared opinions and understanding (Greenwood et al., 2002). Second, the professional associations have an important role in the profession's interaction with other communities in the society. It is the professional associations that protects the domain of the profession and negotiates with other parties to develop and legitimize this. Lastly, professional associations can play an important role in monitoring individual professional practice and stand for the development and maintenance of professional values (Greenwood et al., 2002). Hence, supervisory bodies such as SIA and other professional associations are important since they create shared meanings and understandings (Greenwood et al., 2002).

In conclusion, one function of the professional associations is to protect the professional domain, by developing ethical codes and regulations that works as a framework for the professionals that in turn make the profession to gain legitimacy in society. In order to understandwhat constitutes unprofessionalism from the perspective of the regulatory body in Sweden, it hence becomes important to understand the role of the professional associations.

21

2.2.4 “THE NEW PROFESSIONALISM“

Professionalism has changed as professionals now work in large-scale organizations and international organizations (Evetts, 2011; Suddaby et al., 2009). Professional service work has become commodified, and this changes the professional work relations (Evetts, 2011). When practitioners become more organizational employees than professionals, the traditional employer-professional trust is changed towards more supervision and assessment. The relationship between the professional and the client is also changed towards a customer-relation through the establishment of quasi-markets, customer satisfaction surveys and evaluations (Evetts, 2011). As the statutory audit was abolished for small firms in 2010, Swedish audit firms had to diversify and change their organizational structure in order to adapt (Broberg, Umans, Skog & Theodorsson, 2018). Research has shown that auditing and commercialization are inconsistent, as auditors are more prone to perform their professional duties rather than business developing activities (Broberg et al., 2018). Also, it has been seen unethical to take an active role in marketing. Research after the Enron scandal has showed that commercialization of the audit industry is a driver of unethical behavior and of reduced audit quality and independence (Suddaby et al., 2009; Carter, Spence & Muzio, 2015).

Auditors can maintain both professional and organizational identity, and at the same time hold both organizational and professional values (Broberg et al., 2018). Broberg et al., (2018) suggest that regulators might not consider commercialization as something negative that must be de-limited. Further, they enhance that professionalism is under constant change, and that changes in regulations must be made in consultation with individual auditors.

Broberg et al. (2018) further found that both professional and organizational identities drive commercialization of audit firms. They also point out that even though an auditor has a strong identification with the audit firm, it may not indicate that the auditor is ignoring professionalism. Instead auditors’ professionalism includes both organizational and occupational professionalism (cf. Evetts, 2011). Further, a stronger organizational identity can show how “organizational values” exists in a professional’s everyday work while the “professional values” are imposed from above (i.e the regulators) (Broberg et al., 2018; cf Evetts, 2011). Professional values are hence not present in the professional everyday work but is something that improves the occupations status.

22

2.3 PREVIOUS RESEARCH ON DISCIPLINARY CASES

Several studies have investigated disciplinary cases from oversight bodies. Campbell & Parker (1992) conducted a study in US where they intended to clarify the SEC’s (American Securities and Exchange Commission) philosophy of independent auditing and to document the violations of generally accepted auditing standards in the releases. They analyzed the releases concerning independence between 1972 and 1989. The most common audit failure where SEC took actions was when auditors failed to exercise due care. Campell & Parker (1992) stated that professional judgement, healthy skepticism and lack of independent auditor determination of economic substance over form was the aspects that the SEC emphasized.

Brown & Calderon (1993) conducted a similar study as Campell & Parker (1992), where they analyzed disciplinary cases issued by SEC. They divided the error made by the auditor into two categories, auditing-related and accounting-related errors. The most common audit-related error the SEC imposed an action against, was lack of independence and lack of skepticism. SEC imposes three different types of sanctions: permanently or temporarily barring the defendant from practice before the SEC or public censure. However, they found that SEC made their own interpretations of the rules which led to variations and personalization in the sanctions against the auditors, particularly in the last years before the study (Brown & Calderon, 1993).

Carrington (2010b) investigated the concept of a sufficient audit, where he sought to answer the question how process and professionalism interrelates in order to obtain a sufficient audit. He investigated the disciplinary cases by the SIA between 1995 and 2003. The type of punishment the auditors received was separated into two categories, where one was “shame” (i.e. where the auditor received a warning or a reminder) and the other one was “economic-consequence (i.e. where the authorization or approval was withdrawal). Further, the underlying wrongdoings for the disciplinary action taken by the SIA were categorized into process-wrongdoings and professional-wrongdoings. The results from the study showed that process wrongdoings were more common than professional wrongdoings. Although, the difference were only 30 cases which means that SIA consider both the audit process and the professionalism of the auditor to be important for a sufficient audit. There were also interesting findings in how SIA punished the different wrongdoings (Carrington, 2010b). The most common punishment in process wrongdoings were warning or reminder, and in only 3 out of 140 cases of process wrongdoings the punishment was

23

withdrawal of authorization or approval. This differed from the professional wrongdoings, where 14 out of 110 cases led to a withdrawal of license (Carrington, 2010b).

Carrington’s study (2010b) showed that the supervisory body consider professional appearance to be of importance. Moreover, Carrington highlighted the difference between the consequences of the punishment given to auditors. A withdrawal of authorization or approval can be considered more devastating for the individual auditor, as the career in auditing ends. If an auditor receives a reminder or a warning it has no direct consequence, except from the possible “shame”. Although, the disciplinary cases published from SIA are anonymous. Carrington argue that since the users of financial statement has no other option than trusting the auditor the display of professional conduct becomes important.

Andersson & Selmosson (2011) analyzed the disciplinary cases that results in SIA withdrawing of the license of auditor. The authors based their study on the same categorization as Carrington (2010b). The authors investigate the types of failures that are most frequently as well as which failures that lead to withdrawal, by reviewing the disciplinary cases. The results showed that the most frequent failure was “error of judgement” or “execution when performing the audit”. The authors states that even if it is the most frequent failure, it does not mean that it is the most likely cause of withdrawal. The results showed two additional areas as critical, “failure to cooperate with the SIA’s investigation” and “unprofessional conduct” (Andersson & Selmosson, 2011). In addition to this study, that is similar to Carrington (2010b) is the study made by Alfredsson & Augustsson (2013). They also used the same categorization of process- and professional wrongdoings as Carrington (2010b) and their conclusion showed that the regulatory body has increased the demands on a sufficient audit due to the corporate scandals that has led to an increased supervision of auditors and stricter regulation. They further concluded that professional appearance is not the most important factor in a sufficient audit, compared to Carrington’s (2010b) conclusion.

Another study that deals with disciplinary cases is Brännström & Hultqvist (2015). They looked at the shortcomings of audit failure by examining disciplinary cases. This study concerned all penalties awarded to the auditors, which means that the cases that included the reminder and warning were included in addition to the cases that led to the auditor's authorization or approval

24

being revoked. The results of the study showed that the two most common deficiencies were "review" and "omission".

Bjerkhoel & Persson (2016) investigated the concept of low audit quality. They used a qualitative content to analyze disciplinary cases where the auditors were assigned a sanction in the form of a withdrawal of authorization or approval. The results showed that audit quality can be defined by low quality audit by the categories; “documentation”, “review”, “ignorance”, “regulatory framework”, “formal shortage” and “does not fulfill the stage of the audit”.

The studies presented has investigated disciplinary cases from different perspectives. However, we have not found any study that focuses entirely on professional wrongdoings or what types of behaviors that is considered unprofessional. Therefore, this study takes this opportunity to investigate the concept of professionalism by focusing on professional wrongdoings and unprofessional behavior of the auditor leading to a sanction.

2.4 SUMMARY OF PROFESSIONALISM AND REGULATION

From the research and regulations previously examined, it becomes evident that the literature and regulation overlap each other in many ways. Aspects of professionalism are regularly included in the IESBA:s Code of Ethics. The research that has been carried out relates to a great extent to how the concept was discussed in the regulations, which is to be expected.

Independence is a central part in professionalism in order to keep confidence from society, the auditor must carry out his or her work without pressure from external parties (Hall, 1968; Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013; Broberg, 2013). It is stated in the IESBA:s Code of Ethics that an auditor should not be influenced by subjective values, conflicts of interest or undue influence attempts by other in their professional or business assessments (110. 1A b. Objectivity). Integrity is stated in the IESBA:s Code of Ethics, meaning to be sincere and honest in all professional and business relationships. Brante (2005) claims that strict professional integrity maintains the trust for the profession. Also, Broberg (2013) says that aspects of auditor’s professionalism include that auditor is having integrity towards clients. As society trust professionals to use their knowledge in a responsible manner (Neu, 1991). Having knowledge and competence is a general characteristic of a profession (Mautz, 1988, Espinosa-Pike & Barrinkua, 2017; Reynolds, 2000). Furher, IESBA:s Code of Ethics states that to develop and maintain the skill and competence required to ensure that

25

clients or employers receive services based on current practice, legislation and techniques. Hall (1968) states that professionalism includes being dedicated to work, even if there exists a lack of extrinsic rewards, which corresponds to Broberg’s (2013) findings that an auditor should be responsible, interested and devoted. Acting in the public interest is a general characteristic of professionalism, (Reynolds, 2000; Mautz, 1988; Agevall & Jonnergård, 2013; Brante, 2005), and is not only evident for the auditing profession but for professions in general, and this is also the starting point in the IESBAs code of ethics.

From the literature examined, we can conclude that the overall goal of professions in general, also for the auditing profession, is to maintain the trust of the society. As Brante (2005) writes, it is important for professionals to maintain trust and legitimize the public. In exchange for the profession being allowed to maintain the monopoly in its area of expertise and having high status and high income, the profession must maintain public confidence and be seen as working for the good of society (Reynolds, 2000; Mautz, 1988). By introducing disciplinary activities in the profession, then confidence of the society increases (Neu, 1991). Here, the professional association plays an important role, as the association communicates the profession to the public and monitors their members (Greenwood et al, 2002).

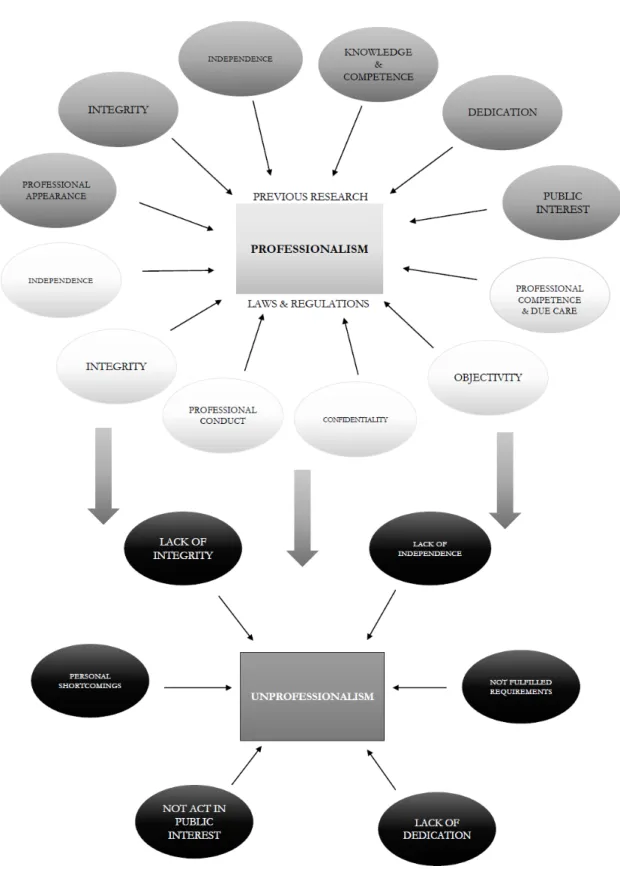

The upper part of Figure 1 illustrates the aspects of professionalism that emerged from the literature studied in the frame of reference. However, as the purpose of this study is to investigate what manifests unprofessionalism in the audit profession, we need to find the reversed aspects of professionalism. The lower part of Figure 1 represents our interpretations of the reversed aspects of professionalism, hence what constitutes unprofessionalism based on previous research and regulations. This is the framework that will be used in order to analyze the data derived from the disciplinary cases.

26

Figure 1 – Framework