DISPARITIES IN SENTENCING DEPENDING ON

ETHNICITY, GENDER, AND AGE AS AN OUTCOME

OF DISCRIMINATION WITHIN THE SWEDISH LEGAL

SYSTEM: AN INTERSECTIONAL ANALYSIS

CAMILLA SVENSSON

Degree project in criminology 60 credits

Criminology, master program August 2018

Malmö University Health and society 205 06 Malmö Supervisor: Lotti Rydberg Welander

DISPARITIES IN SENTENCING DEPENDING ON

ETHNICITY, GENDER, AND AGE AS AN OUTCOME

OF DISCRIMINATION WITHIN THE SWEDISH LEGAL

SYSTEM: AN INTERSECTIONAL ANALYSIS

CAMILLA SVENSSON

Svensson, C. Disparities in sentencing depending on ethnicity, gender, and age as an outcome of discrimination within the Swedish legal system: an intersectional analysis. Degree project in criminology, 15 credits. Malmö University: Faculty of health and society, Department of Criminology, 2018.

Abstract

Previous research has indicated that disparities in sentencing exist within legal systems depending on social characteristics such as ethnicity, gender, and age. The purpose of this study is to investigate what kind of disparities in sentencing are present within the Swedish legal system. It hypothesizes that variations in sentencing are affected by stereotypical perceptions of offenders in regard to ethnicity, gender, and age as well as a legal system that is governed by Swedish norms and values. The data of the study derive from 164 previous convictions from the 2017 issue of Stockholm’s Tingsrätt. The data were analyzed through Ordinary Least Square analysis (OLS) and binary analysis to identify the best predictor of ethnicity, gender, and age in sentencing outcomes as well as examine interaction effects within the social groups. The results of the study are in line with those of previous research and illustrate tendencies toward disparities in sentencing outcomes depending on the social characteristics of ethnicity, gender, and age. In addition, the interaction effects indicate that the social features of youth, non-Swedish nationality, and male gender in combination reflected the highest risk of harsh sentencing compared to other combinations. Sentencing disparities are arguably outcomes of stereotypical perceptions of offenders and an “ethnically” Swedish legal system that is governed by Swedish norms and values. Further research is required to enhance knowledge of disparities in sentencing due to the effect of an “ethnically” Swedish legal system. Such research is needed to determine how provisions that concern equality can become actual conditions.

INTRODUCTION ... 4

The Swedish legal system and discrimination ... 7

DISPARITIES IN SENTENCING ... 8

Ethnicity ... 8

Gender ... 9

Age ... 9

Disparities in sentencing from an intersectional approach...10

Intersectional approach and theoretical framework ...11

Purpose, research questions, and hypotheses...11

METHOD ... 12 Data ...12 Limitations ...14 Ethical considerations ...14 Measures ...14 Dependent variable ...14 Independent variables ...14 Analytical strategy ...15 RESULTS ... 15 Descriptive analysis...16

Standard OLS regression analyses ...16

Binary regression analysis ...17

DISCUSSION ... 19

Limitations ...23

Conclusion ...23

Further research ...24

INTRODUCTION

The Swedish legal system is an institution to maintain a law-proof society that protects each individual in society from crime. The legal system also creates norms and values in society regarding “right” and “wrong” through legislation that is expected to be objective, neutral, and protective of the security of life and property (Police, 2011; Schömer, 2016). However, recent research has detected trends that indicate that the Swedish legal system is not entirely objective and neutral; rather, it may suffer from institutional and structural discrimination (Diesen, 2005; Kardell, 2006; Pettersson, 2006; Sarnecki, 2006). For example, trends in crime statistics reflect that individuals who originate from outside of Swedish tend to be suspected of crimes to a greater extent than ethnically Swedish individuals (Kardell, 2006).

Unlike countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, which have recognized discrimination in the judiciary as a pronounced problem, Sweden does not acknowledge this issue. In Sweden, there are denials of formations such as "we" and "them" at the structural and institutional levels, which complicates the problem of discrimination and its investigation (Sarnecki, 2006, SOU 2005: 56). Therefore, more research on this topic is needed to address discrimination at the institutional and structural levels, as it can lead to the maintenance and reproduction of discriminatory acts against specific groups in society. It is reasonable to assume that there are ideals and norms in Sweden that are characterized by equality, justice, and a belief that it is unacceptable to engage in discrimination due to features such as ethnicity. For example, Sweden has a law instigated to protect individuals from discrimination. In addition, the existing discrimination presumably does not occur with the intention of discriminating. Rather, discrimination is instead due to automated cognitive processes, and those cognitive processes are based on prejudices, performances, and stereotypes (Diesen, 2005; Lindholm & Bergvall, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Thörnqvist, 2008; SOU 2005: 56).

Prejudice, perceptions, and stereotypes about individuals can cause discrimination. However, they are impossible for humans to avoid, and the use of prejudice, perceptions and stereotypes is a necessary cognitive function that prevents people from cognitive congestion. Stereotypes refer to an individual's inner image and representation of other individuals and social groups. These mental images of others create expectations of other people and specific social groups in social interactions. Such inner perceptions and expectations in turn encourage a classification of others that is known as social categorization. Stereotypes and social categorization of other people make the world more manageable, as they facilitate social interaction by dictating how to behave as well as expectations regarding the behavior of others (Fiske, 2013).

Stereotypes and social categorization are based on different criteria and personal attributes, such as ethnicity, gender, and age. People apply these social categories to not only others but also themselves. When an individual self-identifies into a group, it becomes his or her “in-group,” wherein the individual can feel safe and familiar. Groups with which the individual does not identify are accordingly termed

“out-groups,” and the individual can perceive them as foreign as well as more dangerous and threatening (Fiske, 2013; Kteily, Cotterhill, Sidanius, Sheehy-Skeffington & Bergh, 2014).

Perceptions of other people, social groups, in-groups, and out-groups are not always accurate, which can lead to misconceptions and misunderstandings about how other people are as individuals or are likely to behave. The highest risk in this regard affects individuals who are categorized into out-groups. The individuals categorized into out-groups are increasingly associated with negative stereotypes, such as a greater tendency towards dangerous and threatening behavior compared to in-group individuals. Out-groups are also more frequently regarded as less sophisticated than in-groups, which can often lead to the perception that out-groups are less complex. Another assumption is that the culture of individuals in out-groups explains their behavior to a greater extent than in the in-group. Such perceptions of out-groups as less sophisticated and complex and the use of their culture to account for their behavior can lead to discrimination (Fiske, 2013; Kteily et al., 2014; Schömer, 2016; SOU 2005:56).

Negative stereotypes apply to out-groups more often than to in-groups, which may also influence their heavier discrimination (Fiske, 2013; Kteily et al., 2014). This problem can arise not only in social integration but also at the community level. People create expectations of social groups based on stereotypes that can contribute to discrimination at the individual level as well as within various domains of society, such as within the legal system, media and the labor market. Knowledge of other people, social groups, and cultures emerges through subjective representations and from society, including its judiciary and other institutions. However, media and politics also have a role in knowledge production. From a social perspective, the generally negative stereotypes of individuals who belong to out-groups can have far-reaching consequences, such as discrimination within the judiciary (Kteily et al., 2014; Sarnecki, 2006, SOU 2005: 56).

De Los Reyes (2006) has cited one example of how negative stereotypes about out-groups can affect domains of society. She has claimed that political discourse often portrays people of other ethnicities as deviant from the majority population, as “the other,” or as a “dangerous group.” Thereby, it situates people of other ethnicities as ignorant of Swedish norms and values and therefore threatening to society (SOU 2005:56). The killing of innocent dark-skinned people in the United States has also exemplified the consequences and outcomes of a political debate that assumes other ethnicities are more threatening than the majority population. Perceptions and stereotypes of African Americans among the police force, which is a part of the judiciary, suggest that they are likely to carry weapons. As a result, police have acted against and shot such individuals even though they were unarmed or not guilty of any crime. Similar events have not yet occurred in Sweden, which may explain why the structural and institutional discrimination in Sweden is not acknowledged to the same extent as it is in the United States and the United Kingdom (Lindholm & Bergvall, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Thörnkvist, 2008; SOU 2005:56). This example demonstrates how negative expectations from stereotypes can lead to behavior against a group – in this case, other ethnic backgrounds. Moreover, it reveals their effect on actions within the judiciary (Cuddy, Fishing & Glick, 2007; Kteily et al., 2014; Sarnecki, 2006; SOU 2005:56).

In this context, the judiciary is not an independent domain but is instead influenced by society and public perceptions as well as stereotypes and norms (Ericson, 2007; SOU 2005:56). However, the judiciary also impacts the norms and values of society. De Los Reyes (SOU 2005:56) have argued that political discourse affects perceptions and stereotypes of specific groups of society, such as other ethnic groups. De Los Reyes (SOU 2005:54) and Kardell (2006) have claimed that the political debate regarding people of other ethnicities forms the category of “the other.” People in this classification are imagined to not understand Swedish culture, norms, or values and are thus perceived as a threat to Swedish society and welfare. In addition to proposing that political discourse maintains perceptions and stereotypes of other groups, De Los Reyes (SOU 2005:56) has proposed that these perceptions prevent non-members of the majority population from obtaining the rights, including the legal rights, of a Swedish citizen. Therefore, the policy reinforces the creation of in-groups and out-groups and may encourage negative beliefs or stigmatization of the latter. This possibility exists not only in politics but also within other social domains, such as the judiciary; therefore, the court is at risk of supporting structural discrimination (Diesen, 2005; Fiske, 2013; Kardell, 2006; Sarnecki, 2006; Schömer, 2016; SOU 2005:56).

Previous studies have related expectations and perceptions of crimes to stereotypical judgments in the legal context. Given the negative stereotypes about out-groups, crimes that are committed by foreigners may be perceived as more severe than the crimes of ethnic Swedes. Such perceptions may lead to harsher criminal sanctions and assessments for individuals who are categorized into out-groups compared to those who are classified into the in-group and have committed the same type of crime. Moreover, assumptions that people of other ethnicities are more dangerous than the majority population can arguably affect judgements throughout the judicial chain (Diesen, 2006; Cuddy et al., 2007; Kardell, 2006; Nowacki, 2016; Sarnecki, 2006; SOU 2005:56; Steffensmeier, Ulmer & Kramer, 1998; Steffensmeier, Painter-Davis & Ulmer, 2017). For example, people of non-Swedish ethnicities tend to receive more and longer prison sentences than ethnic Swedes (Kardell, 2006; Pettersson, 2006). Kardell (2006) has claimed that such differences reflect a form of structural discrimination.

The issue of discrimination and stigmatization in the judiciary is a complicated subject that can yield both positive and negative treatment. Certain stereotypes, such as those regarding women and the elderly in the context of crime, can result in milder assessments by the judiciary. However, other stereotypes, including those related to ethnicity, may result in harsher treatment of affected groups compared to the majority population. Stereotypical perceptions of offenders presumably influence positive and negative treatment. Since women and the elderly are not typical offenders, they may experience a milder assessment and more lenient convictions; conversely, men and younger individuals commit crimes more frequently, so they could be subject to harsher assessments (Burman, 2010; Diesen, 2005; Kardell, 2006; Lindholm & Bergvall, 2006; Pettersson, 2006; Sarnecki, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Thörnqvist, 2008; Yourstone, Lindholm, Grann & Svenson, 2008).

Previous research performed by Burman (2010), Diesen (2005), Kardell (2006), Lindholm and Bergvall (2006), Pettersson (2006), Sarnecki (2006), Schömer (2016), and Shannon and Thörnqvist (2008) found supporting evidence that people of other ethnicities, but also younger and males experience more negative treatment

than ethnic Swedes, elderly and females encounter when in contact with the legal system. Positive and negative treatment both reproduce preexisting stereotypes and prejudices regarding specific groups of society, which may be a form of structural discrimination (Kardell, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Thörnqvist, 2008; SOU 2005:56).

The judiciary is a community domain that produces and reproduces beliefs, stereotypes, and norms regarding “right” and “wrong” by introducing and maintaining laws and assessments that create order in society and dictate attitudes and behaviors surrounding this order to the public. Therefore, it is essential that the judiciary does not treat individuals differently depending on group belonging, such as in the case of individuals of another ethnicity experiencing a higher risk of harsh sentencing compared to Swedish offenders (Kardell, 2006; Sarnecki, 2006). Sweden is described as one of the world’s most equal countries, but tendencies of disparities in sentencing outcomes are argued to be present within the legal system, which may indicate that the legal system performs structural discrimination (Burman, 2010; Diesen, 2005; Kardell, 2006; Lindholm & Bergvall, 2006; Pettersson, 2006; Sarnecki, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Thörnqvist, 2008).

The Swedish legal system and discrimination

The Swedish judiciary has its ground in the Romano-Germanic legal tradition, which is based on readings of the law. The law is supposed to be objective, neutral and precede security of life and property (Schömer, 2016). To maintain such a legal system, the accused individual gets its case tested in a courtroom (SFS 1974:152). A judge and a panel of lay judges examines the case. The judge is the one that performs the final judgment and sentencing, but it is performed in consultation with the panel of lay judges (Sveriges Domstolar, 2017).

The Swedish judiciary is one of the domains in Swedish society with the lowest percentage of members of a non-Swedish background. Thus, Swedish norms and values govern the Swedish legal system and its actors, as well as judges, lawyers, and police officers and therefore is argued to be a “Swedish ethnic” arena. Thus, investigative routines within the judiciary could arguably be based on Swedish norms and values. Therefore, the court is at risk of discriminating against people who deviate from the norm within the Swedish judiciary regarding in-group criteria and attributes of Swedishness (Diesen, 2005; Kardell, 2006; Sarnecki, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Thörnqvist, 2008).

The concept of Swedishness is built upon an underlying myth about Swedish culture and similarities in appearance. People who appear to be Swedish and act in accordance with Swedish culture, values, and norms are categorized as Swedes (Kardell, 2006). If the judiciary is in fact a Swedish ethnic arena, then there is a risk of discrimination depending on in-group and out-group categorization. Moreover, it is possible that the judiciary perceives people who deviate from Swedishness to be less sophisticated, and they therefore receive convictions that are built upon negative stereotypical perceptions of a specific social category (Diesen, 2005; Kardell, 2006; Sarnecki, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Thörnqvist, 2008). A Swedish ethnic judiciary can increase the risk of founding judgments on stereotypical perceptions of specific social groups or individuals and other extra-legal factors rather than only on extra-legal factors, which is expected of an objective and neutral judiciary. Previous research has indicated that such extra-legal factors can affect decisions and encourage milder or harsher assessments depending on

stereotypical perceptions of specific groups. These results imply that the judiciary may perform some form of structural discrimination (Kardell, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Törnqvist, 2008; SOU, 2005:56; Steffensmeier et al. 2017). Discrimination is rarely explicit within the legal system since professionals of the judiciary have an intention to not discriminate. As an “ethnically Swedish” area, the legal system is inspired by Swedish culture, norms, and values, which may neglect other cultures or pursue an understanding of them beyond existing stereotypical beliefs when investigating criminal cases. Discrimination is an unconscious process that depends on perceptions and stereotypes of other cultures instead of a calculated action by professionals within the legal system. Studies have reported that individuals from other ethnicities did not receive the same advantages as Swedes in investigations because of misconceptions that are built on stereotypical perceptions about people of other cultures and ethnicities (Diesen, 2005; Sarnecki, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Thörnqvist, 2008, SOU 2005:56).

Fiske (2013) has claimed that the ability to distinguish oneself from one’s values, stereotypical perceptions, prejudice, and political opinions is impossible since a person is rarely aware of his or her prejudices, perceptions, and stereotypes regarding other groups. The legal system may not be free from bias because it is comprised of humans who exert the law, which could increase the risk of discrimination and the reproduction of prejudices and stereotypes. The likelihood of experiencing discrimination may, therefore, rise for certain groups, as Swedish norms and values govern the judiciary and exclude certain groups, whose behavior may be judged more severely than that of Swedish offenders depending on stereotypical misconceptions about other groups. Previous research indicates that criminal assessment differs between and within groups, some groups tend to receive harsher assessment and some groups more lenient. Different combinations of social characteristics also seem to affect sentencing outcomes. The social characteristics of interest in this study are ethnicity, gender, and age (Diesen, 2005; Fiske, 2013; Kardell, 2006; Pettersson, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Törnqvist, 2008; SOU 2005:56).

DISPARITIES IN SENTENCING

Ethnicity

Previous research on the Swedish judiciary has highlighted a disparity in sentencing depending on the offender’s ethnicity. Those non-Swedish offenders tend to get more extended sanctions of prison than Swedish offenders (Diesen, 2005; Kardell, 2006; Pettersson, 2006). Pettersson (2006) has also found that Swedes were more likely than other ethnicities to receive certain kinds of sanctions, such as a sentence to forensic psychiatric care. Such an effect could reflect milder assessments or indicate that Swedish offenders are not held responsible for their actions to the same extent as non-Swedish offenders. Pettersson (2006) has also claimed that a forensic psychiatric care examination displaces the responsibility of the individual to the circumstance and can convey that the individual does not need to take accountability for his or her actions to the same extent as in the case of a prison sanction. Such tendencies toward disparities within the judiciary system may be due to stereotypical misconceptions about ethnic groups, that they would be more dangerous than the majority population and a significant problem for the society

(Diesen, 2005; Kardell, 2006; Pettersson, 2006; Sarnecki, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Törnqvist, 2008; SOU 2005:56).

Ethnicity does not exist independently of an individual’s perceptions; rather, it is socially created (Kardell, 2006). Kardell (2006) has described ethnicities in relation to other ethnicities. According to Kardell's (2006) definition of Swedishness, a typically Swedish name would categorize an offender as a Swede, while a non-typically Swedish name would classify the offender as a non-Swede. The present study employs this socially created definition for an estimation of ethnicity, and the names of offenders are assumed to reflect their ethnicity (Harris, 2015; Hofstra & de Shipper, 2018; Kardell, 2006; Treeratpituk & Giles, 2012).

Gender

Gender is like ethnicity in that it is independent of an individual’s perceptions and is socially created. Male and female genders were established in relation to each other. Attributes that are typical of females therefore categorize an individual as female, and male attributes have a likewise effect. The present study assumes this socially constructed definition of gender (Burman, 2010; Fiske, 2013; Yourstone et al. 2008).

Burman (2010) and Yourstone et al. (2008) have argued that gender disparities in sentencing depend on stereotypes about men and women. Men are more often categorized as aggressive, whereas women are viewed as more passive. Steffensmeier et al. (2017) have also evaluated such disparity and determined that males are frequently perceived as more dangerous and threatening than females. Burman (2010), Steffensmeier et al. (2017), and Yourstone et al. (2008) have proposed that such stereotypical perceptions of men and women can encourage harsher or milder assessments on the basis of extra-legal rather than legal factors. In addition, an aggressive offender is viewed as more responsible for his or her actions than a seemingly passive offender. Bontrager Ryon, Chiricos, Siennick, Barrick, and Bales (2017) have also found evidence of disparities in sentencing outcomes depending on gender. However, they observed differences within gender groups depending on the offender's age. Unlike the male group, females did not receive more lenient sentences as they aged.

Age

Previous research on offenders and age as a predictor of sentencing outcomes has revealed that older individuals tend to receive more lenient sentences. This may be surprising since such judgments of older people do not need to consider the same legal aspects that apply to the younger population. By law, people below the age of 21 years are only sentenced to prison under exceptional circumstances (Blowers & Doerner, 2015, Kardell, 2006). Blowers and Doerner (2015) have reported that individuals above the age of 60 years are 40% less likely than young offenders to receive a harsh sentence. Such a result contradicts legal statutes and suggests that older individuals are assessed more leniently depending on extra-legal factors, namely stereotypical perceptions of offenders, and not on legal factors.

Bontrager Ryon et al. (2017) have also studied age as a predictor of sentencing. Their results suggest a curvilinear correlation of age. Moreover, they indicate that the youngest portion of the population – 18 to 20-year old’s – receive the most lenient sentences. Offenders between 21 and 29 years of age were the most likely to receive the harshest sentence, and offenders between 40 and 49 years old were the least affected by receiving a lenient sentence depending on age. Age-based

differences are arguably an effect of stereotypical perceptions of younger and older individuals. Both Bontrager Ryon et al. (2017) and Blowers and Doerner (2015) have claimed that older people are perceived as less threatening than younger individuals and therefore receive more lenient sentences. Bontrager Ryon et al. (2017) have explored the age of offenders with an intersectional approach. The results of age as a predictor not only differed between males and females but also depended on the offender’s ethnicity. Older male offenders received more lenient sentences with age, but female offenders did not. Similar results have been obtained for ethnicity: whites were sentenced with greater leniency as they aged, while blacks and Hispanics were not (Bontrager Ryon et al. 2017).

Disparities in sentencing from an intersectional approach

Previous research on discrimination has demonstrated the importance of studying the topic with an intersectional approach. Experiences of discrimination do not only depend on an individual's ethnicity but also depending on gender and age. Discrimination does differ depending on the different combinations of an individual's social characteristics, the intersectional of the social characteristics’ ethnicity, gender, and age. Black feminism was the first to identify the importance of an intersectional approach. Black women observed that they experience a different kind of discrimination than black men and white women since they are both black and women (Nowacki, 2016; Potter, 2013; Steffensmeier et al. 1998, 2017).

The literature on ethnicity-, gender-, and age-related disparities in assessments by the judiciary have highlighted differences in assessments within legal systems. Previous research has also illuminated the importance of an intersectional approach when investigating disparities in sentencing outcomes, as disparities in assessment seem to differ also within the groups of ethnicity, gender, and age (Nowacki, 2016; Steffensmeier et al. 1998, 2017).

Steffensmeier et al. (1998, 2017) and Nowacki (2016) have studied the United States legal system and examined how stereotypes of offenders may affect sentencing outcomes. Their intersectional approaches included ethnicity, gender, and age as predictors of sentencing outcome. The initial assumption of both studies was that the legal system may treat offenders positively or negatively depending on the offender’s group belonging. Their findings reveal that ethnicity, as a predictor of a harsher sentence, differed within groups when including gender and age as further predictors. For instance, young Hispanic women were at a higher risk of harsh sentencing than black women. However, when studying only ethnicity, black women were the most likely to receive a harsh sentence. For males, young black men faced the highest risk of harsh sentencing. These results reflect the importance of an intersectional approach, as sentencing outcomes differ within groups in terms of ethnicity, gender, and age (Nowacki, 2016; Steffensmeier et al. 1998, 2017). Swedish research on disparities in sentencing has been consistent with international studies, as researchers who have investigated the Swedish judiciary have also found disparities in sentencing according to group belonging (Burman, 2010; Kardell, 2006; Lindholm & Bergvall, 2006 Pettersson, 2006; Sarnecki, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Yourstone et al. 2008). However, there is a lack of knowledge in the Swedish context about disparities in sentencing. No research has included all three predictors of sentencing: ethnicity, gender, and age. Swedish research has considered only two of these predictors in the same study. The research of Nowacki (2016) and Steffensmeier et al. (1998, 2017) has demonstrated the need to include several

predictors when exploring sentencing outcomes in order to identify differences that may exist within the groups of interest. The present study aims to include ethnicity, gender, and age in its investigation potential disparities in sentencing in the Swedish legal system to gain insight into differences within and between groups. If sentencing disparities based on group belonging exist within the Swedish judiciary, the legal system could perpetuate structural discrimination.

Intersectional approach and theoretical framework

Existing research has emphasized the importance of adopting an intersectional approach on the matter of sentencing outcomes. This was applicable when studying outcomes of sentencing in terms of the outcome of one variable and the outcomes of different variable combinations. The variables of ethnicity, gender, and age do not always have the same effect when analyzed separately as when they are analyzed in variable combinations (Nowacki, 2016: Steffensmeier et al. 1998, 2017).

Nowacki (2016) and Steffensmeier et al. (1998, 2017) have indicated that stereotypical beliefs and commonly held perceptions can lead to discrimination within the legal system specifically in regard to blameworthiness, the protection of society, and practical implications of sentencing. The social categories of ethnicity, gender, and age – whether separately or in combination – create a specific social position for an individual with regard to these aspects, which can contribute to disparate treatment within the legal system that is derived from stereotypical perceptions and beliefs. Varying degrees of blameworthiness, the protection of society, and practical implications being applied to the same behavior may be due to prejudices, perceptions, and stereotypes based on ethnicity, gender, and age. These social categories and their intersections are not only individual attributes but also cultural categories that shape the distribution of criminal sanctions (Steffensmeier et al. 2017).

The theoretical framework adopted by Steffensmeier et al. (2017) consists of stereotypical perceptions of an offender depending on the individual's combination of ethnicity, gender, and age, which can affect sentencing outcomes in regard to blameworthiness, the protection of society, and practical implications of sentencing. The following study adopts the same intersectional approach and theoretical framework as Steffensmeier et al. (2017). Thus, it assumes that sentencing outcomes may be affected not only by legal factors but also extra-legal factors in the context of stereotypical and commonly held perceptions of offenders regarding the social characteristics of ethnicity, gender, and age.

Purpose, research questions, and hypotheses

Since the Swedish legal system is arguably an “ethnically Swedish” domain and is thus dominated by Swedish norms and values, the routines of investigation may be based on Swedishness and its associated implications, including norms and values, and any demonstrated inconsistency with these Swedish categorizations may be perceived as a sign of deviance. Therefore, the Swedish legal system is at risk of discriminating against people who deviate from the norm on the basis of extra-legal factors, such as the stereotyping of offenders, and could, in so doing, produce and reproduce structural discrimination (Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Törnqvist, 2008; SOU, 2005:56; Steffensmeier et al., 2017). The present study applies an intersectional approach to investigate whether discrimination exists within the Swedish legal system in regard to sentencing outcomes. It considers whether stereotypical perceptions of offenders and the prevailing “ethnically Swedish”

culture and norms within the legal system affect sentencing outcomes based on ethnicity, gender, and age. Disparities in sentencing outcomes for similar crimes depending on an offender’s ethnicity, gender, or age could indicate structural discrimination within the Swedish legal system. The present study hypothesizes that commonly held perceptions, stereotypes, and prejudices regarding specific social characteristics and groups in terms of ethnicity, gender, and age influence the judiciary, which, in turn, impact upon disparities in sentencing outcomes.

Accordingly, the research questions for this study are as follows: What are the differences in assessment outcomes within the Swedish legal system attributable to an offender's ethnicity, gender, or age? What are the interaction effects of ethnicity, gender, and age on these possible differences?

The hypothesis of this study is that disparities in sentencing dependent upon ethnicity, gender, and age are present within the Swedish judiciary and influenced by the stereotypical perceptions of the offenders. The hypothesis is based on previous research, which indicates that people of non-Swedish ethnicity receive the harshest sentences, that males are sentenced more harshly than women, and that sentences are less lenient for younger offenders than for older ones. Males, younger people, and people of non-Swedish ethnicities comprise the social groups that are perceived as the most blameworthy for their actions and the most dangerous. Thus, they are viewed as the groups from whom society needs protection, and thus can expect to receive the harshest assessments. Therefore, the present research hypothesizes that men, young people, and non-Swedish individuals receive the harshest sentences. The elderly, on the other hand, are often perceived as sickly, which can suggest potential complications with sustaining their imprisonment. Therefore, the present research hypothesizes that the elderly receives more lenient assessments as a result of the of practical implications of their sentences. In addition, the elderly, women, and Swedes are likely to be perceived as less dangerous, less blameworthy in their actions, and viewed as the groups from whom society does not need to be protected. These groups are, therefore, hypothesized as receiving the most lenient assessments (Steffensmeier et al., 2017).

The interaction effects hypothesis is that young males of non-Swedish origins receive the harshest sentences of any of the combinations. However, other combinations of ethnicity, gender, and age are expected to differ. The contribution that the above hypotheses may make in this field is to potentially address the knowledge gap regarding the influence of stereotypical perceptions on crime assessment and sentencing outcomes.

METHOD

Data

The data for this study were derived from 164 convictions issued by Stockholm’s Tingsrätt in 2017. These convictions were demarcated within the Swedish Penal Code Chapter 3 as “Crimes Against Life and Health” (Brottsbalken kap: 3, 1962:700 “Brott mot liv och hälsa”), and as crimes only “against a person.” The age range of offenders was established as 21 years and older since statutory assessments of younger offenders are more lenient than assessments of offenders who are above the age of 21 (Kardell, 2006). The judgments declared a conviction of “crime against life and health” as the primary crime or as a secondary crime.

The data excluded certain cases; namely convictions of homicide, attempted homicide, infanticide, procurement, convictions with secrecy, and crimes in close relationships, in order to limit data errors. According to previous research, discrimination against minorities is most visible in cases in which the offender has no prolonged relationship with the victim and the crime is not of an overly severe character (Pettersson, 2006).

Previous research has also indicated that investigations typically address the types of crimes upon which stereotypes and prejudices would have the most significant impact on sentencing (Pettersson, 2006). The demarcation of crimes and convictions also facilitates case comparisons. It is problematic to compare overly broad categories of crime; for instance, homicide should not be compared to traffic offenses. The outcomes of such crimes differ, and the procedure and underlying causes for committing such actions obstruct reasonable comparisons (Petterson, 2006).

Further designations were the type and length of the convictions. The type of verdict for investigation was any judgment with a sanction of prison and a minimum length of two weeks. The demarcation of sanctions of prison facilitated comparison and analysis between sanctions. As in the example of traffic offenses versus homicides, it would have been problematic to compare prison terms and fines (Petterson, 2006).

The social characteristics of interest to this study were the offender’s ethnicity, gender, and age. The offender's citizenship, which could be identified from the respective verdict, determined his or her ethnicity. When the offender was a Swedish citizen, the convictions did not reveal the offender's origin. In these cases, the name of the offender was presumed to indicate his or her origin. Both the first name and surname were considered since studies have reported that the use of both first names and surnames can increase accuracy in determining ethnicity (Hofstra & de Schipper, 2018). Names that contained “Å,” “Ä,” or “Ö” were categorized as ethnically “Swedish,” as these are letters of the Swedish alphabet. In addition, individuals with a surname ending with –sson were also classified as “Swedish.” Such surnames are the Swedish version of the English surname suffix –son; for example, the English “Anderson” would be “Andersson” in Swedish.

For individuals whose names could not be associated with Swedish ethnicity by the chosen demarcation, online research was conducted for the names to determine their origins. Previous studies have indicated that such a method provides a high degree of accuracy in determining ethnicity. A study by Treeratpituk and Giles (2012) has reported 85% accuracy in name-ethnicity estimation by identifying the origin of names on Wikipedia. Hofstra and de Schipper (2018) have also conducted a study of name-based determinations of ethnicity with a miscalculation of only 1.3%. Although the name-ethnicity determination has received criticism, name and ethnicity have a stronger correlation in Sweden than in many other countries. Therefore, this method should be considered valid to determine ethnicity (Kardell, 2006). Ethnicity was divided into three categories – “Swedish,” “European,” and “non-European” – that are similar to those in Kardell’s study (2006).

The second social characteristic that was chosen for investigation is gender. Determination of gender was based on the pronoun that verdicts used for each accused individual. Gender was coded as “male” or “female” since the verdicts employed only male and female pronouns.

As the third and final social characteristic of interest, age was calculated from the birth year of the accused individual. The age variable was recoded into ordinal data to enable a comparison of three age groups: “Young, 21-30,” “Adult, 31-40,” and “Older, 41+.”

Limitations

As a limitation to the data, the determination of ethnicity might have included errors. For instance, in cases where information was not available in the verdicts, individuals may have been coded to an incorrect ethnicity. Such cases were rare in the dataset, however, so the effect of such errors should not substantially bias the data.

A similar limitation was present for the gender variable. Even if the pronouns within the judgments were female or male, they might include accuracy errors regarding an individual’s ”real" gender. For example, there could have been offenders who were categorized as female or male in the verdicts but who did not self-identify as either female or male. Nevertheless, the individuals’ own experiences of discrimination were not the focus of this study, so neither of these limitations should significantly affect the data.

Ethical considerations

The data for this study were descriptive and derived from public documents; therefore, a consent claim was not necessary. However, the approval of the ethics committee was required and obtained. As in all types of research, the data were handled confidentially to preclude any possibility of identifying the individuals whose convictions and sentences inform this study (Codex, 2017).

Measures

Dependent variable

The dependent variable for this study was the “length of the sentence” in terms of the number of months for which an individual was sentenced to prison. Sentence durations were sourced from the 2017 Tingsrätt verdicts. The crimes that underlie these verdicts were those in the Swedish Penal Code Chapter 3, “Crimes Against Life and Health” (Brottsbalken kap: 3, 1962:700, “Brott mot liv och hälsa”). The dependent variable was coded as a continuous variable using the natural log of the sentence. The briefest prison sanction in the dataset was 0.5 months, while the highest was 50 months.

In the binary regression analysis, the dependent variable of sentencing was divided into categories of “lenient” and “harsh” types. “Lenient” sentences were prison sanctions of up to one-and-a-half months, whereas “harsh” sentences were a minimum of one-and-a-half months. The data excluded judgments that sanctioned youth care, forensic psychiatric care, fines, or community service.

Independent variables

The independent variables were ethnicity, gender, and age. The variable of ethnicity was coded into three categories of ethnicity: “Swedish,” “European,” and “non-European” individuals. The reference category throughout the analysis was "Swedish" ethnicity. The gender variable was treated as a dummy variable with categories of “male” or “female.” The reference category throughout the analysis was "female." The age variable was divided into three groups: “Young, 21-30,”

“Adult, 31-40,” and “Older 41+”, with the third group serving as the reference category. The chosen reference categories were the groups that were estimated to receive the most lenient sentences.

Analytical strategy

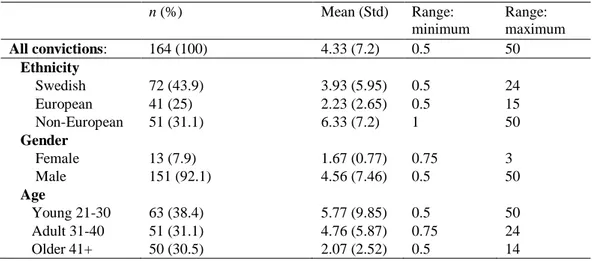

The data conducted were analysed by four different analyses, to be able to investigate the possible differences in assessment outcomes that may be present within the Swedish legal system. First, a descriptive analysis was conducted (see Table 1.1) to visualize the variance of the predictors and enable evaluations of the regression analysis. Second, one Ordinary Least Square (OLS) analysis was conducted (see Table 1.2) to determine if ethnicity, gender, or age was the best predictor of sentencing outcomes. Another OLS analysis (see Table 1.3) was performed that included the interaction effect of the predictors in order to study the variations within each group of ethnicity, gender, and age (Field, 2013; Pallant, 2011).

Last, a binary regression analysis of the variables was conducted to explore the predictability of social characteristics for sentencing in terms of the odds ratio, whereby the odds of a harsher sentence increase with combinations of the social characteristics of ethnicity, gender, and age. The binary logistical regression (see Table 1.4) was performed stepwise. It first included the predictor of gender then subsequently age and ethnicity to observe increased or decreased risk of a harsh sentence with each predictor’s variation in predictability. For this analysis, the dependent variable was recoded as a dummy variable of a “lenient” or “harsh” sentence instead of using the natural log of the sentence (Field, 2013; Pallant, 2011).

RESULTS

Descriptive analysis

The descriptive analysis included means and standard deviations of the sentencing for each predictor (length in months sentenced to prison), standard deviation (std), and the range (see Table 1.1). The descriptive analysis distinguished 72 individuals with Swedish ethnicity, 41 with European ethnicity and 51 of non-European ethnicity. Swedish individuals received a mean sentence of 3.93 months with a standard deviation of 5.95 months. Europeans were sentenced to prison for 2.23 months on average with a standard deviation of 2.65 months. Finally, non-Europeans were sentenced to 6.33 months in prison on average with a standard deviation of 7.2 months. The analysis included 13 women with an average prison sentence of 1.55 months and a standard deviation of 0.77 months. Meanwhile, the study featured 151 males with an average sentence of 4.56 months and a standard deviation of 7.46 months.

The first age group, "Young, 21-30 years old,” included 63 individuals with an average prison sentence of 5.77 months and a standard deviation of 9.85 months. The group “Adults, 31-40 years old” had an average sentence of 4.76 months in prison and a standard deviation of 5.87, and it included 51 individuals. The oldest age group, “Older than 41 years,” contained 50 individuals with an average sentence of 2.07 months and a standard deviation of 2.52 months.

Table 1.1: Descriptive data for the dependent variable (length of sentence in months) and

independent variables (ethnicity, gender, and age), number (%), mean, standard deviation (std), range of months of sentencing, minimum, and maximum.

Length of sentence (months)

n (%) Mean (Std) Range: minimum Range: maximum All convictions: 164 (100) 4.33 (7.2) 0.5 50 Ethnicity Swedish 72 (43.9) 3.93 (5.95) 0.5 24 European 41 (25) 2.23 (2.65) 0.5 15 Non-European 51 (31.1) 6.33 (7.2) 1 50 Gender Female 13 (7.9) 1.67 (0.77) 0.75 3 Male 151 (92.1) 4.56 (7.46) 0.5 50 Age Young 21-30 63 (38.4) 5.77 (9.85) 0.5 50 Adult 31-40 51 (31.1) 4.76 (5.87) 0.75 24 Older 41+ 50 (30.5) 2.07 (2.52) 0.5 14

Standard OLS regression analyses

The data were first analyzed through a standard OLS regression analysis (see Table 1.2) to identify which variable is the best predictor of sentencing within the Swedish legal system. The only significant result of the OLS analysis reveals age to be the best predictor of harsher sentencing (β -0.19). The predictor of age conveys that younger offenders are more likely to receive a harsher punishment. The predictors of gender and ethnicity appeared to be equivalent predictors of sentencing. The predictor of gender (β 0.12) suggests a higher likelihood of receiving a harsh sentence for men, while the predictor of ethnicity (β 0.12) indicates that individuals who are of a non-Swedish ethnicity are more likely to receive a harsh punishment. However, neither gender nor ethnicity was significant as a predictor of sentencing. The predictors can explain 7% of the variance in sentencing (R2 0.07).

Table 1.2. Standard OLS Regression of “Sentencing”: unstandardized B, standard errors SE B,

standardized β, regression coefficients and explained variance, R2

B SE B β R2 (n)=164 Gender 3.19 2.04 0.12 0.0144 Age -1.63* 0.67* -0.19* 0.0342 Ethnicity 1.02 0.67 0.12 0.0142 All predictors 0.07 *p <0.05 **p <0.01 ***p <0.001

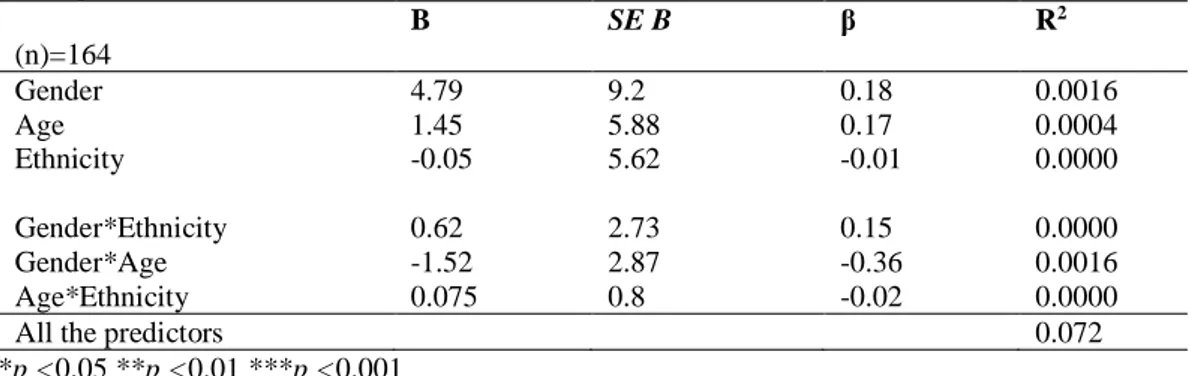

A second OLS analysis was conducted and included the variables of interactions of ethnicity, gender, and age in order to study their effects (see Table 1.3). The results of interaction effects imply that sentencing differed within groups, although none of the effects was significant.

The interaction of gender*ethnicity (B 0.62) conveys that the effect of ethnicity on sentencing outcomes was stronger for males than for females. Males of non-Swedish ethnicity were at higher risk of receiving a harsh sentence compared to Swedish males; however, for females, the effect of ethnicity did not affect sentencing. The risk of receiving a harsh sentence in regard to ethnicity did emerge

among men in the study but not among the women. This interaction effect evidences that gender and sentencing outcomes differ according to ethnicity.

The interaction effect of gender*age (B -1.52) indicates that an offender’s age affected sentencing outcomes but differed in terms of gender. This effect implies that older males were sentenced more leniently, but older females were not. Moreover, it suggests that gender and sentencing outcomes did differ depending on age.

The last interaction effect of age*ethnicity (B 0.075) supports differences in the effect of age and sentencing outcomes between ethnicities. Older offenders of non-Swedish ethnicities received harsher sentences than older non-Swedish offenders. Therefore, age and sentencing outcomes apparently differed depending on ethnicity. The predictors explain 7.2% of the outcomes of sentencing (R2 0.072). Table 1.3. Standard OLS Regression of “Sentencing” that includes the interaction effects of gender,

age, and ethnicity: unstandardized B, standard errors SE B, standardized β, regression coefficients and explained variance, R2

B SE B β R2 (n)=164 Gender 4.79 9.2 0.18 0.0016 Age 1.45 5.88 0.17 0.0004 Ethnicity -0.05 5.62 -0.01 0.0000 Gender*Ethnicity 0.62 2.73 0.15 0.0000 Gender*Age -1.52 2.87 -0.36 0.0016 Age*Ethnicity 0.075 0.8 -0.02 0.0000

All the predictors 0.072

*p <0.05 **p <0.01 ***p <0.001

Binary regression analysis

Binary regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the predictors’ predictability for sentencing (see Table 1.4). The results reflect how predictors of social characteristics of ethnicity, gender, and age can increase or decrease the risk of harsh sentencing. The analysis was performed stepwise to enable an evaluation of the heightened or diminished risk of receiving a harsh sentence, with the variation in predictability of the predictors occurring in a stepwise combination. The analysis included gender as a predictor and yielded a result of OR 1,046. This result indicates that males were at a 1,046-time higher risk of receiving a harsh sentence compared to a female offender. However, the result was not significant.

The analysis then incorporated both gender and age and consequently indicated that the group with the highest likelihood of receiving a harsh sentence was the age group of offenders between 21 and 30 years old, who experience an increase in risk that is 4,328 times higher than that of the oldest age group (OR 4,328). The group of 31- to 40-year-old offenders faced a 2,374-time higher risk of receiving a harsh sentence compared to the oldest age group (OR 2,374). Both of these results were significant.

The OR (1.25) of gender in the second step of the binary regression analysis indicated that the predictors of gender and age in combination increased the risk of harsh sentencing for males by 1.25 times. This result evidences that the risk of receiving a harsh sentence for males increased alongside their age. Nevertheless, the result was not significant.

In the third step, the binary regression analysis included all three predictors of sentencing: gender, age, and ethnicity. The predictor of ethnicity indicated that Europeans had a lower risk (OR 0.553) of receiving a harsh sentence compared to Swedes. However, also in comparison to Swedes, non-Europeans had a 1,655-time higher risk of receiving a harsh sentence. Still, these results were not significant. The effect of the age predictor also increased when the analysis included ethnicity as a variable. The results within the age groups reveal that the group of 21- to 30-year-old offenders confronts a risk of receiving a harsh sentence that is 4.5 times higher than that of the oldest group (OR 4.5); this was the only significant effect. The age group of 31 to 40 years old had a 1,997-time higher risk of receiving a harsh sentence compared to the oldest group, but this effect was not significant. The effect of a higher age diminished when including ethnicity as a predictor, which indicates that ethnicity as a predictor of sentencing has a more substantial effect on younger offenders than on older ones.

The effect on gender when including ethnicity in the analysis decreased the effect (OR 1.21) in comparison to the analysis in the second step despite a persistent trend of males receiving harsher sentences than females. The decrease in the effect supports that the effect of ethnicity mediates the effect of gender. Nevertheless, the result was not significant.

Table 1.4. Stepwise binary regression analysis of sentencing within gender, age, and ethnicity:

regression coefficients B value, standard errors SE, significance level p, increase/decrease in odds, odds ratio OR Coefficients B SE p OR Step 1 Constant (sentence) 0.15 0.56 0.782 1.167 Gender (ref. cat.=female) 0.45 0.58 0.938 1.046 Step 2 Constant (sentence) -0.79 0.64 0.223 0.456 Gender (ref. cat.=female) 0.22 0.6 0.713 1.25 Age

(ref. cat. = Older 41+) 0.003

Adult 31-40 0.86* 0.39* 0.026* 2.374* Young 21-30 1.47*** 0.43*** 0.001*** 4.328*** Step 3 Constant (sentence) -0.698 0.68 0.303 0.497 Gender (ref. cat.=female) 0.19 0.61 0.757 1.21 Age

(ref. cat. = Older 41+) 0.004

Adult 31-40 0.69 0.4 0.086 1.997

Young 21-30 1.5*** 0.45*** 0.001*** 4.5***

Ethnicity

(ref. cat. =Swedish) 0.065

European -0.59 0.43 0.17 0.553

Non-European 0.5 0.40 0.213 1.655

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study is to investigate disparities in sentencing depending on the social characteristics of ethnicity, gender, and age. To this end, it examines whether assessments of crime differed according to the ethnic origin, gender, or age of offenders who were convicted at Stockholm’s Tingsrätt in 2017. The analyses revealed a few significant effects. These effects are arguably due to the judiciary, which is affected by commonly held perceptions, stereotypes, and prejudices regarding specific social characteristics and groups in terms of ethnicity, gender, and age. However, the majority of the analyses identified no significant effects between the applied variables despite claims from several studies that disparities exist in sentencing depending on the ethnicity, gender, or age of offenders (Nowacki, 2016; Steffensmeier et al., 1998, 2017). In view of this, the null hypothesis remains unchanged and leaves room for future research to address the knowledge gap regarding the influence of social characteristics, such as ethnicity, gender, and age, on sentencing outcomes.

The results support that disparities exist within the Swedish legal system, or at least in the Stockholm’s Tingrätt of 2017. Even though most of the effects were not significant, certain tendencies are apparent. The OLS of each predictor of sentencing yielded a result that was in line with the conclusions of previous research. People of non-Swedish origins tended to receive harsher sentences than Swedish offenders. Moreover, males were sentenced more harshly than females, and sentences of younger offenders were harsher than those of older offenders. Age was the best predictor of sentencing outcomes and the only significant predictor. Descriptive analysis of the results, however, revealed one deviant effect that is inconsistent with previous research and not visible in the OLS of each predictor. In the descriptive result of ethnicity, Europeans tended to receive the most lenient judgments, which contradicts previous research. Otherwise, it is possible that previous research has not considered such tendencies. Limitations of the study may explain this result; for example, Europeans are not one homogeneous group of people but instead include numerous kinds of stereotypical perceptions, some of which could have resulted in a milder assessment than Swedes. Limitations of the study are further elaborated later in the paper.

The significant effects of age in the study are in line with the literature as well as the hypotheses for the age variable. Younger offenders were at a higher risk of harsh sentencing compared to older offenders despite a lack of obvious legal or actual factors that might affect such result. Analyses of the age variable have indicated that the age group with the highest risk of receiving a harsh sentence is that of individuals in the age range of 21 to 30 years, and the most lenient sentences were issued to the oldest offenders, who were above the age of 41 years. These results are similar to those of Bontrager Ryon et al. (2017), who have presented support that individuals in the 21-29 age range receive the harshest sentences, and older offenders are sentenced with the most leniency despite no attenuating legal factors for older offenders.

Both Blowers and Doerner (2015) and Bontrager Ryon et al. (2017) have argued that criminal assessment is an effect of extra-legal factors, such as stereotypical perceptions of older people. Existing stereotypical perceptions of older people assume, for example, that they are less threatening than younger people. Such a

perception could encourage more lenient sentencing. Younger individuals are subject to the opposing, commonly held perception that they are more threatening than the elderly. The arguments of Blowers and Doerner (2015) and Bontrager Ryon et al. (2017) are relevant for the present study given its similar results. The results of the present study are also consistent with those of Steffensmeier et al. (2017), which evidence that legal decisions are guided by stereotypical and commonly held perceptions of specific social groups in regard to blameworthiness, protection of society, and practical implications. Since older people are perceived as less threatening, they may receive milder assessments, as society does not require protection from non-threatening individuals such as older offenders. Furthermore, the elderly is perceived to be sicklier than the younger population. To imprison sickly people are presumably more problematic and perceptions of the elderly being sicklier may affect why the elderly are not sentenced to prison to the same extent as younger individuals. Steffensmeier et al. (2017) have claimed that such perceptions shape the distribution of criminal sanctions through, for example, milder assessments for older offender’s dependent on practical implications as well as a necessity for protection from younger offenders, who consequently receive harsher sentences. The present study has yielded a similar result (Steffensmeier et al., 2017).

The interaction effects of age were significant with gender but not with ethnicity. Still, the effects that could be explained were in line with previous research insights. Likewise, Bontrager Ryon et al. (2017) have concluded that age is relevant in sentencing outcomes depending on the offender’s gender and ethnicity. Men and Swedish offenders received more favorable assessments with age, but this was not true for women, Europeans, or non-Europeans. The argument of Steffensmeier et al. (2017) regarding stereotypical perceptions of offenders in terms of blameworthiness, protection of society, and practical implications can explain this result. Females are often envisioned as victims of crimes, while males are viewed as significantly more aggressive, more likely to be offenders, and responsible for violence and crimes. Moreover, the elderly is assumed to be less dangerous, as are females in general. Therefore, the age advantages regarding assessment, which arguably accompany age, do not produce the same result for females as for males. Women already have an advantage in sentencing due to their gender and guided by perceptions of both age and gender (Blowers, & Doerner, 2015; Bontrager Ryon et al. 2017; Burman, 2010; Yourstone et al. 2008).

However, in its interaction with ethnicity, age only affected sentencing outcomes for Swedes and not for Europeans or non-Europeans. This finding can be explained by stereotypical perceptions of offenders and individuals of other ethnicities as more dangerous to the society than Swedes, which could result in a harsher judgment that is independent of the age of the offender. When the effect of one social characteristic differs within the group, it could arguably have an immense effect on the sentencing outcome for another social characteristic, which in this case is gender or a non-Swedish ethnicity (Blowers, & Doerner, 2015; Bontrager Ryon et al., 2017; Burman, 2010; Steffensmeier et al., 2017; Yourstone et al., 2008). The results of non-significant effects still highlight tendencies among disparities in sentencing that are in line with previous research as well as the hypotheses of the study (Blowers, & Doerner, 2015; Bontrager Ryon et al., 2017; Burman, 2010; Yourstone et al., 2008). Specifically, males received harsher sentences than females

to a great extent, and non-Swedish offenders were subject to more negative treatment through a longer prison sentence.

Evaluating the interaction effects of these tendencies can illuminate the anticipated differences within the groups. The interaction effect of gender and ethnicity reflects that the hypothesis regarding harsher sentences for people of non-Swedish ethnicities only applied to the male group and not to the females. Women of non-Swedish ethnicities seemed to receive equivalent sentences to non-Swedish women, although non-Swedish males were sentenced more harshly than Swedish males. Such result is consistent with the claims of both Nowacki (2016) and Steffensmeier et al. (1998, 2017) that males of ethnicities apart from the majority population are at a higher risk of receiving harsh assessments. These results illustrate a tendency toward disparities in sentencing that does not depend on legal factors but instead of extra-legal factors regarding ethnicity and gender. Moreover, various combinations of social characteristics may affect these disparities. Combinations of social characteristics may yield different outcome effects since of the effect of one social characteristic does not affect sentencing outcomes to the same extent as another. The result of this interaction effect implies that ethnicity as a variable of sentencing affects criminal assessment only for males, as ethnicity is only relevant to aspects of sentencing among the male population.

Further tendencies emerged from investigating the interaction effect of age and ethnicity. This interaction effect, like the other two, evidenced a disparity in sentencing within groups and reinforced previous research conclusions and hypotheses (Nowacki, 2016; Steffensmeier et al. 1998, 2017). This tendency suggests that age advantages in sentencing are present within legal systems only during convictions of a person from the majority population and not when the accused is of a minority ethnicity.

The analyses results convey that the Swedish legal system is at risk of upholding structural discrimination. The tendencies within the results are consistent with those of previous research, which has argued that results that resemble those of the present study would be considered outcomes of a discriminatory legal system (Burman; 2010; Diesen, 2005; Nowacki, 2016; Kardell, 2006; Pettersson, 2006; Sarnecki, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Törnqvist, 2008; Steffensmeier et al., 1998, 2017; SOU 2005:56; Yourstone et al., 2008). Professionals of the Swedish legal system has an intention and obligation to not discriminate and to be objective and neutral. Still, disparities in sentencing seem to persist on the basis of social characteristics; this trend could be interpreted as a form of discrimination, as it does not seem to be legal factors that affect sentencing outcomes (Diesen, 2005; Schömer, 20016; Shannon & Thörnqvist, 2008; SOU 2005:56).

The Swedish legal system is arguably an “ethnically Swedish” area that is governed by Swedish norms and values, and this can affect the justice process. Shannon and Thörnqvist (2008) have cited support for how legal system professionals have worked to affect crime assessments. Assessment that is built upon stereotypical and commonly held perceptions of others might produce and reproduce stereotypes, and the findings of this study support this theory. The sentencing outcomes that produced the data are in line with conclusions of previous research that disparities in sentencing exist within the legal system and are dependent on extra-legal rather than legal factors. Therefore, such sentencing outcomes may depend on

stereotypical perceptions of offenders (Diesen, 2005; Sarnecki, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Shannon & Thörnqvist, 2008).

Previous research has claimed that people of other ethnicities are often viewed as a foreign, dangerous, and threatening group, which fosters perceptions of this specific group. Individuals within this group are arguably sentenced more harshly than the majority population because of the perception that they are more dangerous in comparison. The categorization is an unconscious process; therefore, professionals are at risk of discrimination even if they have an intention to not to. Given the “ethnically Swedish” area of the Swedish legal system, the risk may be even more significant, as understanding other cultures might be particularly difficult when such an understanding develops from stereotypical perceptions and when other cultures are not included in the ruling domain, such as within the legal system (Fiske, 2013; Nowacki, 2016; Kardell, 2006; Schömer, 2016; Pettersson, 2006; Shannon & Thörnqvist, 2008; Steffensmeier et al., 1998, 2017; SOU 2005:56). A further example of how stereotypical perceptions can lead to disparities in sentencing is evident when investigating the interaction effects. When the effect of one social characteristic differs within a group, another social characteristic may largely affect the sentencing outcome. The interaction effect that exemplifies this is, for example, the interaction effect of gender and age. Females are portrayed as victims of crimes more frequently than males, who are more often envisioned as aggressive but also more responsible for crimes. The elderly is perceived as less dangerous, and this applies to females in general. Therefore, the age advantage in regard to sentencing is that age does not impose the same result on females as on males, as females already enjoy advantages in sentencing that are due to gender and ruled by perceptions of both gender and age (Blowers, & Doerner, 2015; Bontrager Ryon et al., 2017; Burman, 2010; Yourstone et al., 2008).

The interaction effect of age and ethnicity and the interaction effect of ethnicity and gender can be interpreted similarly. Non-Swedish ethnicities can be perceived as more dangerous groups, which heavily informs sentencing regardless of the offender’s age or gender. Perceptions of age and gender reflect how dangerous an individual of another ethnicity might be, so such individual would not be sentenced more leniently on the basis of his or her age or gender, which is true for Swedish offenders (Blowers, & Doerner, 2015; Bontrager Ryon et al., 2017; Nowacki, 2016; Kardell, 2006; Pettersson, 2006; Steffensmeier et al., 1998, 2017; Yourstone et al., 2008).

The interaction effects demonstrate how combinations of social characteristics yield different sentencing outcomes. Nowacki (2016) and Steffensmeier et al. (1998, 2017) have illustrated that the combination of black male youth has led to the harshest sentencing in U.S. courtrooms. Similar tendencies emerged within this study since the combination of youth, non-Swedish ethnicity, and male gender imparted the highest risk of harsh sentencing. The combination of young, non-Swedish males encountered a risk that is 4.5 times higher than any other combination. The combination of youth, male gender, and non-Swedish ethnicity remained significant throughout the binary analysis, which supports the existence of disparities in sentencing depending on social characteristics within the Swedish legal system.