The role of the local business climate

for self-employment among

immigrants

- A cross-sectional study between Swedish municipalities.

BACHELOR THESIS WITHIN: Economics NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: International Economics AUTHOR: Matilda Gustafsson, Joakim Olsson TUTORS: Lina Bjerke, Jonna Rickardsson JÖNKÖPING May, 2018.

2

Bachelor Thesis in Economics

Title: The role of the local business climate for self-employment among immigrants - A cross-sectional study between Swedish municipalities.

Authors: Matilda Gustafsson & Joakim Olsson Tutor: Lina Bjerke & Jonna Rickardsson Date: May, 2018

Key terms: Self-Employment, Business Climate, Immigrants, Natives

Abstract

This study examines the relationship between the local business climate and the share of self-employed immigrants in Sweden on a municipal level. These results are then compared to the relationship between the local business climate and the share of self-employed natives. The study also compares the share of self-employed immigrants as well as natives that are still in business after one year. The variables that are used to assess the business climate have been used in previous research that has tested the impact of the business climate. The results show that regional differences in the business climate can explain differences in the share of self-employed immigrants to some extent. The results also show that while most variables are significant for both self-employed immigrants and self-employed natives, the business climate influences the share of self-employed natives more than the share of self-employed immigrants. This indicates that the functions in the local business climate can be more available to natives than to immigrants. The share of self-employed immigrants who are still in business after one year has an insignificant relationship with the local business climate, whereas the share of self-employed natives who are still in business after one year has a moderately significant relationship with the local business climate. Hence, the business climate influences regional differences in the share of self-employed who are still in business after one year more for natives than for immigrants.

3

Contents

1 Introduction ... 4 2 Literature review ... 7 3 Methodology ... 12 3.1 Data ... 12 3.2 Dependent variables ... 12 3.3 Independent variables ... 13 3.4 Empirical model ... 17 3.5 Empirical method ... 194 Empirical results and analysis ... 21

4.1 Descriptive statistics ... 21

4.2 Regression results and analysis ... 22

5 Conclusions ... 29

6 References ... 31

4

1 Introduction

The immigration inflow to Sweden has increased steadily over the last few years. The largest groups of people that migrate to Sweden today are fleeing from war, violence and oppression (Sweden Statistics, 2018). The steady increase of immigrants has given rise to a divided political debate. According to opinion polls from the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter, immigration and integration is the dominating issue among Swedish voters in the forthcoming election in 2018 (DN, 2017).

The level of employment among immigrants has been consistently lower than the level of employment for domestically born Swedes for over a decade (Statistics Sweden, 2017), showing that there are issues for immigrants to become assimilated into the Swedish labour market. Barriers in the labour market for immigrants are for instance discrimination, low levels of education and lack of social networks with natives which has been found to increase the probability of finding work (Bursell, 2012; Lundborg, 2013; Lindgren et al., 2010). During 2017, unemployment among immigrants decreased somewhat, but it was still several percentage points higher than that of native-born individuals (Statistics Sweden, 2017). In other words, there are structural integration issues for immigrants in Sweden. One solution to this problem, that was a popular political discussion in the 90s in Sweden, was that self-employment could resolve the issue of immigrants falling in to structural unemployment (Slavnic, 2013).

There is also previous researchthat suggests that many immigrants are involuntarily becoming

self-employed because they cannot enter the regular labour market (Ljungar, 2007). A report presented by the government confirms that this was the case in the 80s and 90s for many immigrants (SOU, 1999:49). Research finds that factors within the business climate affect entrepreneurship in Sweden, hence native entrepreneurs as well as immigrant entrepreneurs should be influenced by the business climate. For instance, the size of the public sector has been found to have an influence on the level of self-employed (Nyström, 2012).

The purpose of this study will thus be to investigate how the local business climate relates to the share of self-employment among immigrants in different municipalities in Sweden. It will also examine the relationship between the business climate and the share of self-employed immigrants who are still in business after one year. The study will compare self-employed immigrants and self-employed natives to see if there are differences between the two groups. The definition of the business climate that this study will use is inspired by the definition that is used by the Confederation of Swedish Enterprises: “the sum of institutions, attitudes, laws

5

and knowledge that faces the enterprises each day” (own translation). In other words, the definition of the business climate that we will use will encompass several aspects of the business climate. The components that we will include are formal institutions, attitudes from local business owners, knowledge, supply and demand of products and services as well as employees, the well-being of the municipality, and factors that induce entrepreneurship. The definition of the business climate will be discussed further in the literature review section.

Fölster and Jansson (2015) find a significant positive relationship between the business climate in a municipality and the level of labour integration for immigrants in Sweden. Hence, the prevailing business climate in a given municipality explains part of the labour integration outcome in that municipality. Andersson and Hammarstedt (2010) find that self-employment among immigrants in the current generation has a positive effect on the rate of self-employment for future generations, indicating that self-employment today can lead to reduced unemployment for coming generations. This is an example of path dependence, meaning that previous start-up rates affect current start-up rates, creating persistence in the start-up rates (Andersson and Koster, 2011).

Earlier research focuses to a large extent on national structures that prevent immigrants from becoming integrated into the regular labour market (Klinthäll et al., 2016). However, there is not much research about whether the local business climate can explain differences self-employment among immigrants in municipalities in Sweden. Stevenson (2001) finds that the majority of new businesses are started in the three largest city regions and statistics from Statistics Sweden (2016), show that the share of immigrants who become self-employed differ in different regions. Nyström (2012) studies differences in entrepreneurship in municipalities in Sweden and finds that factors in the local business climate have an influence of the level of self-employment. However, Nyström (2012) does not discuss or study the impact of the business climate on the immigrants who are self-employed and whether there is a connection between those variables. Also, Nyström does not investigate whether the local business climate has a positive impact on immigrant owned businesses in a longer perspective.

As already mentioned, there are differences in the proportion of immigrants that start businesses in different Swedish municipalities. Therefore, it is of great importance to analyse these differences and to understand whether the prevailing business climate in a certain municipality has a significant effect on the level of self-employed immigrants, both from the initial start-up and those who are still active after one year. This paper examines these relationships and

6

immigrants in different municipalities in Swedenwhich has not yet been done on the level of

municipalities before.

In the following section we present the theoretical background for the study where we examine the factors within the business climate that are related to the share of self-employed as well as research about self-employed immigrants. Next, we present the method and perform a cross-sectional study on Swedish municipalities by using data from Statistics Sweden, the Confederation of Swedish Enterprises and the Swedish Companies Registration Office. Then, we describe how the variables should be related to the share of self-employed. In the section after that we present and discuss our empirical findings. In the last section we arrive at our conclusions.

An important aspect to point out in this paper is that we do not distinguish between different ethnicities of immigrants. Instead, we define “immigrants” as all people that are born outside of Sweden which is important to keep in mind. Immigrants are a very heterogenous group, meaning that different groups of immigrants may have different relationships with the local business climate when becoming self-employed. Nevertheless, we will examine immigrants as a homogenous group since we are not interested in examining different ethnicities.

The results that the study finds are that the business climate, in terms of our definition, partly explains the regional differences in the share of self-employed immigrants, but that it explains regional differences in the share of self-employed even more for natives. This indicates that the local business climate influences natives more than immigrants and that the functions in the business climate are more available to natives than to immigrants. One of these functions could be business networks. Hence, policy makers could perhaps try to facilitate the networking process for self-employed immigrants. In addition, rural municipalities can try to attract immigrant entrepreneurs through benefits, in order to increase entrepreneurship. Also, the study finds that the business climate is insignificant for the survival of the business after one year for immigrants, but that it has some influence on the survival of native-owned businesses. The business climate only seems to influence self-employed immigrants in the start-up process; not in the longer run, although we only look at the survival after one year.

7

2 Literature review

In general, the level of self-employment among immigrants – especially immigrants that come from outside of Europe – in Sweden has increased more than the level of self-employment among native Swedes since the 1990s (Andersson och Hammarstedt 2011; Najib 1999). Ljungar (2007) argues that one of the main reasons that immigrants in Sweden become entrepreneurs is because of structural problems in the labour market, hindering them from finding work. Becoming self-employed might not be preferred by an immigrant, but it may be the only option so as not to become unemployed. In other words, immigrants are in general necessity-based entrepreneurs. The fact that many immigrant business owners start enterprises in branches with strong competition and low profits indicates that self-employment is necessary; not desired. These results are similar to what is discussed in Reynolds et al. (2004) regarding the topic of the motivation behind new firm formation where they argue that there are often two main motivations for people to start new firms; seeking an opportunity or becoming an entrepreneur out of necessity because of for instance unemployment.

Andersson (2011) finds that self-employment among immigrant men, with the exception of men that originate from the south of Europe and the Middle East, leads to lower incomes in comparison to immigrant men who have been previously employed in the regular labour market. Hjerm (2004) finds that self-employed immigrants have substantially lower incomes than immigrants who are employed in the regular labour market.

Hammarstedt (2004) concludes that higher education leads to a lower propensity to become self-employed, both among immigrants and native-born entrepreneurs. However, Eliasson and Westlund (2012) find that the entrepreneur’s level of education increases the probability of becoming an entrepreneur in both rural and urban areas in Sweden. Hence, the level of education shows different results for the probability of becoming an entrepreneur in Sweden. Armington and Acs (2002) find that regions in the United States with more college graduates have a positive effect on new firm formation in those regions.

Andersson (2015) finds large regional differences when measuring the number of new establishments per 10 000 inhabitants in Swedish municipalities. He also asserts that the employment rate and the regional income level are negatively related to the number of start-ups in a region and suggests that it is due to less necessity-based start-ups. Andersson (2015) claims that the reason why median income is negatively related to the number of start-ups is because the opportunity cost of starting an enterprise increases as the income increases. Davidsson et al. (1994) is one of the first studies that shows variation in the level of new firm formation between

8

municipalities in Sweden. They show that population density and unemployment have significant results on the variation in the level of new firm formation, where the population

density is positively significant while unemployment is negatively significant. However,

Armington and Arc (2002) find thatthe relationship between unemployment and new firms is

insignificant. Armington and Arc (2002) discuss differences between US states and show that the rate of the states’ college graduates, income growth and population growth have a significant positive relationship with the number of new firms started relative to the labour force. In addition, more entrepreneurial role models in a region influence the probability of becoming an entrepreneur (Blanchflower and Oswald, 1998; Arenius and Minniti, 2005). Hence, the entrepreneurial activity in regions with more companies should increase.

When it comes to research about the relationship between the unemployment rate and the number of start-ups, there are varying results as to whether this relationship should be positive or negative. One possible explanation to this ambiguous result could be what Audretsch, Dohse and Niebuhr (2015) find; that the structure of the regional unemployment has an effect on whether the results are significant or not. They examine new firms with different levels of technology and find that the significance of the results varies depending on if you treat those who are unemployed as a low-skilled or high-skilled labour force in terms of education instead of as a homogenous group.

Westlund et al. (2014) find that social capital, measured as firm perception of local public attitudes to entrepreneurship and as the share of small businesses, have an impact on the propensity to become an entrepreneur in Swedish municipalities. They also show that there is a slight difference between rural and urban municipalities when it comes to social capital and that social capital has a stronger impact on start-ups in rural municipalities than in urban ones. However, Eliasson and Westlund (2012) show that there are no differences in the start-up rates between rural and urban municipalities in Sweden. They also find that most variables affecting the rural regions also affect the urban regions.

As already mentioned, Fölster and Jansson (2015) find evidence that a good business climate in a Swedish municipality increases the level of integration in terms of the number of immigrants finding work in that municipality. However, there is no evidence that there is a positive relationship between the local business climate and the level of self-employed immigrants. Fölster et al. (2015) assert that the business climate is “a consequence of institutions and actions that arise endogenously” and that actions can be taken to improve the local business climate such as reducing the time for administrative processes for enterprises.

9

Acemoglu et al. (2005) argue that nations' growth can largely be explained by the nations institutions rather than traditional models (exogenous factors) and find support by studying historical examples that economic institutions that favour property rights and that prevent groups with political power from gaining too much political power in a society generate economic growth. They also imply that economic growth occurs through endogenous factors in the form of economic institutions and not through exogenous factors.

Many regulations and policies are determined on the national level in Sweden, which suggests that there are similar institutions across regions. However, Andersson et al. (2012) show that there are differences in start-ups between municipalities in Sweden. One of their findings

suggests that there are regional factors that influence the number of start-ups since most

municipalities with high rates of start-ups in 2007 also had high rates of start-ups in 1987. This leads them to argue that national regulations cannot be the only determinant of the number of start-ups. One factor that could explain the regional differences would be if there are differences

in the local institutions.Also, Qvist (2012) investigates the governance of the local integration

process for immigrants in two municipalities in Sweden. He finds that most of the decisions and the responsibility for integrating immigrants is made on the local level and that the government mainly provides poor guidelines for the municipalities on how the integration process should be executed. The fact that there is no clear national integration process for immigrants could be a possible explanation as to why there are regional differences in the integration process in Sweden. Also, there may be differences in competence when it comes to the local representation of national regulations (Fölster and Jansson, 2015).

Baumol (1990) is one of the first to highlight the effect of institutions on entrepreneurship and asserts that there are different uses of economic resources from entrepreneurs in different institutional settings. Nyström (2008) examines the business climate on the national level and finds evidence that a smaller government sector, a good legal structure, security of property rights and less control of credit have a positive effect on the level of self-employment. Thus, in regard of the local business climate, these factors contribute to a better business climate, in terms of the local institutional settings, facilitating for entrepreneurs to start enterprises. However, Nyström (2008) does not distinguish between native-born entrepreneurs and immigrant entrepreneurs.

Borjas (1986) finds that it takes time for an immigrant to accumulate enough capital to start a business soon after arriving in a new country and that the person in question has usually stayed in the new country for a few years before he or she starts an enterprise. Also, research has shown

10

that immigrants often find informal ways of financing their businesses because it is in general more difficult as an immigrant to find financing through bank loans (Yazdanfar and Abbasian, 2013). Aldén and Hammarstedt (2014) show that immigrant entrepreneurs are being denied bank loans to a greater degree than native born entrepreneurs and that immigrant entrepreneurs often have to pay a higher interest on their loans. As previously mentioned, Nyström (2008) finds support that less control of credit has a positive effect on the level of entrepreneurship. The fact that it is more difficult for immigrants to find financing in formal ways suggests that the conditions in the business climate for immigrant entrepreneurs are less favourable than for native entrepreneurs.

Kremel, Yazdanfar and Abbasian (2014) discover that self-employed immigrants in Sweden tend to use formal business networks less than native Swedish entrepreneurs in the early stage of the start-up process. Instead, immigrant entrepreneurs use informal networks such as friends and family and ethnical networks to start their businesses. Ethnical networks can however be an obstacle to immigrant self-employment due to increased competition for certain products and services (Andersson and Hammarstedt, 2015). On the other hand, they also show that ethnical concentration in an area, for example a municipality, can increase the level of ethnical businesses by for instance creating a market for certain products and services. In other words, by increasing the demand for certain products, the local business climate can become better for self-employed immigrants.

Looking at the mechanisms within the business climate that nurture entrepreneurship in the form of start-up rates, the entrepreneurial culture, or norm, is an important factor. Putting entrepreneurship into a social context, the propensity to become an entrepreneur increases if it is socially acceptable to become an entrepreneur (Davidsson et al., 1994; Blanchflower and Oswald, 1998; Arenius and Minniti, 2005). This can be measured as the number of companies per capita where more companies per capita means that there is a larger entrepreneurial culture. Other mechanisms in the business climate that breed entrepreneurship are demand and better communication (Tillväxtanalys, 2013). Also, research find that unemployment gives rise to necessity-based self-employment (Reynolds et al., 2004). Research finds that it is difficult for immigrants to enter social networks with natives as well as formal networks. (Lindgren et al., 2013; Kremel, Yazdanfar and Abbasian, 2014). Hence, it may be more difficult for immigrants to capture the entrepreneurial opportunities in municipalities where the entrepreneurial culture is prominent than for natives. As already mentioned, immigrants often become self-employed out of necessity, indicating that this is the case.

11

As mentioned in the introduction, the components that we will include in our definition of the local business climate are formal institutions, attitudes from local business owners, knowledge, supply and demand of products and services as well as employees, the well-being of the municipality, and factors that induce entrepreneurship. Formal institutions will be represented by the public sector size, measured as the share of people in a municipality that work in the public sector; knowledge will be represented by the share of people who have studied at a higher level at some point; attitudes will be represented by the scores from local entrepreneurs that the municipalities have received in the survey conducted by the Confederation of Swedish Enterprises as well as the number of companies per capita, where more companies per capita means that there is a positive attitude toward entrepreneurship within the municipality; supply and demand, both for products and services as well as employees, will be represented by population density. In addition, the municipal tax rate will be included to capture the well-being of the municipality. Median income is considered an opportunity cost within the business climate, where a higher median income means that there is a higher opportunity cost to become self-employed. The number of companies per capita and the share of unemployed will represent the factors that give rise to self-employment within the business climate. Population density is also considered a factor that gives rise to self-employment since a denser population increases demand. Together, all the independent variables represent the local business climate and this is the definition that will be used throughout the paper.

Taking into consideration the previous research about self-employment in Swedish municipalities, there are regional differences in the level of start-ups. There is research suggesting both that there are differences in entrepreneurship between rural and urban areas and that there are no differences. The differences between regions in the level of employment in total in Sweden suggests that there are regional differences in the level of self-employed immigrants as well. However, research about regional differences, in terms of the local business climate, in self-employment among immigrants has not been done before. Therefore, the next sections will examine this relationship and it is why this paper contributes to the research about self-employment among immigrants.

12

3 Methodology

This section presents the data, econometric model and econometric method used in this paper.

3.1 Data

The data used in the regressions on the self-employment level among immigrants and natives consist of cross-sectional data where the sample is on each of the 290 municipalities in Sweden, in the year 2015. Data on the self-employment level among immigrants and natives is retrieved from Statistics Sweden and consist of those who are between the ages 20-64. Cross-sectional data on the survival rate of those still self-employed after one year are sampled from 264 municipalities since this data is not collected in some municipalities by Statistics Sweden. All independent variables except for local business perception of the business climate and the number of companies in each municipality were gathered from Statistics Sweden. The perception of the local business climate is gathered through a survey conducted by the Confederation of Swedish Enterprises. Their survey is measuring the attitude among local businesses and politicians on how they perceive the local business environment. In this study we will only use the answers from local businesses since we are only interested in the perceived business climate from the perspective of an entrepreneur. They send out the survey to 70 000 businesses in total; 200 each in smaller municipalities and 400 each in larger municipalities. The largest municipalities Malmö, Gothenburg and Stockholm differ as they send out 600 questionnaires in Malmö and Gothenburg and 1200 in Stockholm. In 2015, there were 31 361 entrepreneurs across Sweden who answered the survey with an answer frequency of 48 % and it ranged between 32 % and 59 % for the municipalities individually. The number of companies in each municipality is collected from the Swedish Companies Registration Office, which is an office in which every Swedish entity must register before being able to do economic transactions. Thus, they should have highly accurate statistics over the number of companies per municipality.

We will also use data from year 2010 and compare whether the results are different to those in 2015.

3.2 Dependent variables

Self-Employment, Immigrants

The dependent variable in our regression is the share of immigrants who are employed through self-employment. This data is collected from Statistics Sweden, who calculate this as the total number of self-employed immigrants divided by the total number of people employed. This captures how well each municipalities’ business environment influences the choice of

13

immigrants to become self-employed regardless of the size of the municipality. To determine whether the person will be categorized as self-employed or employed in the regular labour market, Statistics Sweden looks at the source from which the individual earns the greatest taxable income. For instance, if a person works both in the regular labour market and has a company and earns most of her taxable income from self-employment, she will be categorized as self-employed.

Still in Business after one year, Immigrants

This variable shows the percentage of immigrants who are self-employed that are still in business one year after the launch. Statistics Sweden calculate this as the total number of immigrant entrepreneurs in 2015 plus the total number of immigrant entrepreneurs in 2014 divided by the total number of entrepreneurs in 2014.

Self-employment, Natives

This variable shows the share of natives who are employed through self-employment. Statistics Sweden calculate this as the total number of entrepreneurs divided by the total number employed. The same distinction for whether an individual is categorized as self-employed or as employed in the regular labour market is used as in the categorization for self-employed immigrants.

Still in Business after one year, Natives

This variable shows the percentage of natives who are self-employed that are still in business one year after the launch. Statistics Sweden calculate this as the total number of native-born entrepreneurs in 2015 plus the total number of entrepreneurs in 2014 divided by the total number of entrepreneurs in 2014.

3.3 Independent variables

This section shows the variables for which we will regress our dependent variables on. There are in total nine explanatory variables and five dummy variables. The variables of interest are Perception of the local business climate, Tax, Unemployment, Public Sector,

Foreign-background and Unemployment Immigrants. The control variables are Income, Education and Population Density. Together, the independent variables compile the business climate as is discussed in the literature review.

14 Perception of the local business climate

To test whether the business climate has a relationship with the immigrants who are self-employed, this study will use data from a survey that is conducted yearly by the organisation the Confederation of Swedish Enterprises. Local business owners answer questions about the local business climate and assess how well the prerequisites for owning a business are in the municipalities. For instance, they answer questions about the supply of competent work force, competition from the local government and information from the local government. They use a scale from 1-6 where 1 is bad and 6 is excellent. This data is commonly used in previous research about the local business climate (see e.g Fölster, Jansson and Gidehag, 2014; Nyström, 2012) and according to Lindström (2008) the only ones who can truly asses the business climate are the agents operating within it.

Tax

One of the variables of interest will be the municipal tax rate because it might induce incentives for entrepreneurship and affect an entrepreneur’s ability to accumulate capital. Thus, differences in the tax rate between regions might affect the level of entrepreneurship. Also, the municipal tax rate is an indication of the well-being of the municipality, where a low tax rate means that the municipality is doing well whereas a high tax rate means that it is doing worse. Davidsson et al. (1994) find that the municipal tax rate has no relationship with entrepreneurship, which is similar to the result Nyström (2012) finds.

Total unemployment

This variable represents the share of total unemployment in the different municipalities. The variable of unemployment has been very common when measuring regional differences in new firm formation and is often used in papers (see e.g. Davidsson et al., 1994; Armington and Acs, 2002; Eliasson and Westlund, 2012). It is interesting to study its correlation to self-employment since the choice of becoming an entrepreneur could be out of necessity rather than out of opportunity seeking, which a positive relationship would indicate (Reynolds et al., 2004).

Public Sector size

This variable is the total number of people employed in the public sector and governmental controlled institutions, or companies, per capita. Nyström (2008, 2012), finds that the size of the public sector has a negative effect on new firm formation across regions and nations.

15

The education variable shows the share of inhabitants who have studied at a university at some point. This could increase the probability of becoming an entrepreneur as it increases the supply of skilled labour, which might be a motivation for some entrepreneurs to locate the business to certain municipalities (Nyström, 2008; Armington and Acs, 2002). However, research shows that higher education can also decrease the probability of becoming an entrepreneur (Hammarstedt, 2004).

Population Density

The idea behind population density is that a denser population will increase demand since there will be more potential customers in the municipality (Nyström, 2008). Population density is used as a variable in most research about firm formation and explains differences in the level of entrepreneurship in many papers (see e.g. Davidsson et al., 1994; Armington and Acs, 2002; Eliasson and Westlund, 2012; Nyström, 2012).

Median Income

A higher median income should lead to a higher demand of products and services from the population all else equal, which should increase the level of entrepreneurship in a municipality. However, a high wage in the labour market may lead to an increased opportunity cost Andersson (2015) of becoming self-employed, which should decrease the level of entrepreneurship. The structural problems for immigrants to gather financial capital and resources (see e.g. Yazdanfar and Abbasian, 2013; Borjas, 1986; Nyström, 2008) indicate that income is an important factor when deciding to become an entrepreneur.

Companies per capita

This variable is the total number of companies within the municipality. This includes all companies that are registered in the Swedish Companies Registration Office. Previous research finds that many entrepreneurs' decision to become entrepreneurs is influenced by other entrepreneurs in their social network. Thus, on an aggregate level more companies could influence others to make decision of entering self-employment (Blanchflower and Oswald, 1998; Arenius and Minniti, 2005).

Foreign Background

This variable represents the share of the municipalities’ population that is foreign-born and those who are native-born but who have foreign-born parents. Andersson and Hammarstedt (2011) show that ethnic concentration in a municipality can create markets for ethnical goods

16

and services which has a positive effect on the level of self-employment. However, they also find contradicting results that a higher share of ethnic concentration leads to higher competition which has a negative effect on the level of self-employment. Kremel, Yazdanfar och Abbasian (2014) find that foreign-born entrepreneurs are more likely to make use of ethnical networks than native-born entrepreneurs. However, we do not know the ethnicities of the business owners we have included in our data. We include this variable as a proxy for any possible markets that may have arisen in a municipality due to ethnical concentration.

Unemployment Immigrants

This variable represents the share of total unemployment among immigrants in different municipalities. According to Ljungar (2007) many immigrant entrepreneurs choose to become self-employed because of structural problems in the regular labour market. A higher share of unemployment among immigrants might lead to more immigrants choosing to become self-employed; not because of a good business climate but as a necessity to create earnings.

Regional Dummies

Our model will also include dummy variables for what type of municipality a given municipality is categorized as. The reason for this is because there is research showing that there are differences in the start-up rates between rural and urban municipalities (see e.g. Eliasson and Westlund, 2012). We will use the categorization made by the Swedish Board for Economic and Regional Growth (The Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth, 2018). The different types of municipalities are:

Large city municipality, defined as a municipality that has less than 20 % of the population

living in rural areas and who together with adjacent municipalities have a combined population of at least 500 000 inhabitants.

Urban municipality in proximity to a large city municipality, defined as a municipality that

has less than 50 % of the population living in rural areas and at least half of the inhabitants have less than 45 minutes of commuting time by car to an urban area with at least 50 000 inhabitants.

Urban municipality remotely located, defined as a municipality that has less than 50 % of the

population living in rural areas and less than half of the inhabitant have less than 45 minutes of commuting time by car to an urban area with at least 50 000 inhabitants.

17

Rural municipality in proximity to a large city municipality, defined as a municipality that

has at least 50 % of the inhabitants living in rural areas and at least half of the inhabitants have less than 45 minutes of commuting time by car to an urban area with at least 50 000 inhabitants.

Rural municipality remotely located, defined as a municipality that has more than 50 % of

the inhabitants living in rural areas and less than half of the inhabitants have less than 45 minutes of commuting time by car to an urban area with at least 50 000 inhabitants.

Rural municipality very remotely located, defined as a municipality where all inhabitants are

living in rural areas and have more than 90 minutes of commuting time by car to an urban area with at least 50 000 habitants.

3.4 Empirical model

The purpose of this thesis is to examine the relationship between the municipalities’ business climate and the share of self-employment among immigrants out of the total number of working people in Sweden. To analyse this relationship, we will do regressions on both the share of self-employed immigrants as well as the share of self-self-employed natives to be able to analyse any differences between the two populations.

Another model will be used and another regression will be run on only self-employment among immigrants but in which we have included more specific factors for immigrant entrepreneurs. This model should be accurate description of factors influencing this group. The specific factors that have been included in the model are the share of people with a foreign background in a given municipality and the share of unemployed immigrants; not the total share of unemployed

people in a municipality.

Another set of regressions will be run where on a model where the dependent variable will be the share of self-employed immigrants/natives out of the total number of people employed who are still running a business after one year. The models will have the same independent variables as in model one and two (for immigrants). The reason for this is to control for whether there is a positive impact of the business environment in a longer perspective and not only in the start-up process.

All variables, except the share of total unemployment and the share of self-employed who are still in business after one year (immigrants/natives), are in logarithmic form because they are more normally distributed when they are logged than when they are in their original form. By inspecting the R-squared we should be able to detect if the business climate overall, as defined in the literature review, has the same relationship with foreign-born entrepreneurs as with

18

native-born entrepreneurs. By examining the beta-coefficients individually we aim to draw conclusions about how the individual factors in the business climate relate to the share of self-employment among immigrants.

1st model:

LnSelf − employi

= 𝛽1𝑖+ 𝛽2∗ Ln𝐵𝑢𝑠 𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐𝑖+ 𝛽3∗ 𝐿𝑛𝑇𝑎𝑥𝑖+ 𝛽4∗ 𝑈𝑛𝑒𝑚𝑖+ 𝛽5∗ Ln𝑃𝑢𝑏 𝑆𝑒𝑐𝑖+ 𝛽6

∗ Ln𝐶𝑜𝑚𝑝𝑖+ 𝛽7∗ Ln𝐸𝑑𝑢𝑖+ 𝛽8∗ Ln𝐼𝑛𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑒𝑖+ 𝛽9∗ Ln𝑃𝑜𝑝 𝐷𝑒𝑛𝑖+ 𝛽10

∗ 𝐷1(large city)𝑖+ 𝛽11∗ 𝐷2(rural very remotely located)𝑖+ 𝛽12

∗ 𝐷3(rural in proximity to large city)𝑖+ 𝛽13∗ 𝐷4(𝑢𝑟𝑏𝑎𝑛 𝑟𝑒𝑚𝑜𝑡𝑒𝑙𝑦 𝑙𝑜𝑐𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑑)𝑖

+ 𝛽14∗ 𝐷5(𝑟𝑢𝑟𝑎𝑙 𝑟𝑒𝑚𝑜𝑡𝑒𝑙𝑦 𝑙𝑜𝑐𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑑)𝑖

2nd Model

LnSelf − employ (immigrant)𝑖

= 𝛽1𝑖+ 𝛽2∗ Ln𝐵𝑢𝑠 𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐𝑖+ 𝛽3∗ 𝐿𝑛𝑇𝑎𝑥𝑖+ 𝛽4∗ Ln𝑃𝑢𝑏 𝑆𝑒𝑐𝑖+ 𝛽5∗ Ln𝐶𝑜𝑚𝑝𝑖+ 𝛽6

∗ Ln𝐸𝑑𝑢𝑖+ 𝛽7∗ Ln𝐼𝑛𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑒𝑖+ 𝛽8∗ Ln𝑃𝑜𝑝 𝐷𝑒𝑛𝑖+ 𝛽9∗ Ln𝐹𝑜𝑟 𝐵𝑎𝑐𝑘𝑖+ 𝛽10

∗ Ln𝑈𝑛𝑒𝑚, 𝐼𝑚𝑖+ 𝛽11∗ 𝐷1(large city)𝑖+ 𝛽12∗ 𝐷2(rural very remotely located)𝑖

+ 𝛽13∗ 𝐷3(rural in proximity to large city)𝑖+ 𝛽14

∗ 𝐷4(𝑢𝑟𝑏𝑎𝑛 𝑟𝑒𝑚𝑜𝑡𝑒𝑙𝑦 𝑙𝑜𝑐𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑑)𝑖+ 𝛽15∗ 𝐷5(𝑟𝑢𝑟𝑎𝑙 𝑟𝑒𝑚𝑜𝑡𝑒𝑙𝑦 𝑙𝑜𝑐𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑑)𝑖

3rd Model:

Still in Bus𝑖= 𝛽1𝑖+ 𝛽2∗ Ln𝐵𝑢𝑠 𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐𝑖+ 𝛽3∗ 𝐿𝑛𝑇𝑎𝑥𝑖+ 𝛽4∗ 𝑈𝑛𝑒𝑚𝑖+ 𝛽5∗ Ln𝑃𝑢𝑏 𝑆𝑒𝑐𝑖+ 𝛽6

∗ Ln𝐶𝑜𝑚𝑝𝑖+ 𝛽7∗ Ln𝐸𝑑𝑢𝑖+ 𝛽8∗ Ln𝐼𝑛𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑒𝑖+ 𝛽9∗ Ln𝑃𝑜𝑝 𝐷𝑒𝑛𝑖+ 𝛽10

∗ 𝐷1(large city)𝑖+ 𝛽11∗ 𝐷2(rural very remotely located)𝑖+ 𝛽12

∗ 𝐷3(rural in proximity to large city)𝑖+ 𝛽13∗ 𝐷4(𝑢𝑟𝑏𝑎𝑛 𝑟𝑒𝑚𝑜𝑡𝑒𝑙𝑦 𝑙𝑜𝑐𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑑)𝑖

+ 𝛽14∗ 𝐷5(𝑟𝑢𝑟𝑎𝑙 𝑟𝑒𝑚𝑜𝑡𝑒𝑙𝑦 𝑙𝑜𝑐𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑑)𝑖

Self-employ (immigrants/natives)i = Percentage of the employed immigrants/natives whom are self-employed (logarithm).

Bus perci = The businesses perception measured by the municipalities' average score in the survey (logarithm).

Taxi = Income tax rate of the municipality (logarithm).

Unemi = The share of total unemployment in the municipality.

Pub seci = Size of the local government by measuring number of employed in the public sector per capita in the municipality (logarithm).

Compi = The number of companies in the municipality (logarithm).

Edui = The share of inhabitants that has attended some form of higher education (logarithm).

Incomei = Median income in the municipality (logarithm).

Pop Deni = The municipalities' population density per square kilometre (logarithm).

For Backi = The share of inhabitants within the municipality whom has foreign background

19

Unem Imi = The share of immigrants who are unemployed in the municipality (logarithm).

Still in Bus (immigrants/natives)i = The share of self-employed immigrants/natives who are still

in business after one year.

D1 = 1 if the municipality is categorized as large city municipality, 0 otherwise.

D2 = 1 if the municipality is categorized as rural municipality very remotely located, 0

otherwise.

D3 = 1 if the municipality is categorized as rural municipality in proximity to a large city

municipality, 0 otherwise.

D4 = 1 if the municipality is categorized as urban municipality remotely located, 0 otherwise. D5 = 1 if the municipality is categorized as rural municipality remotely located, 0 otherwise.

The base dummy is if the municipality is categorized as urban in proximity to a large city.

3.5 Empirical method

In this paper there will be a total of six regressions estimated using ordinary least squares. In the model, the correlation is high between some of the explanatory variables, as can be seen in table 3 (see appendix), which is why we conducted a variance inflation factor test (VIF). VIF shows that none of the variables have a value above ten, which indicates that there is no serious multicollinearity. However as there are correlations between the variables we suspect that multicollinearity is still present which is why we in table 8 and table 9 have run regressions where we exclude some of the correlated variables. The implication of these results is then discussed in the empirical analysis. The models also show signs of heteroscedasticity, according to the Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey test, which is why we include robust standard errors when we estimate the models.

Hypothesized results.

Below is a table with the results we are expecting based on what previous research finds. The municipal tax rate, public sector size and median income should be negatively related to the share of self-employed. Local business perception, the share of unemployed, companies per capita, population density and the share of unemployed immigrants should be positively related to the share of self-employed. The relationship between the share of self-employed and the share of highly educated as well as the share of people with a foreign background is ambiguous because previous research finds different results.

20

Table 1 Hypothesis table

Variables Expected Sign (+/-)

Perception of Local Business Climate +

Tax -

Unemployment +

Public Sector Size -

Companies +

Education ambiguous

Income -

Population Density +

Foreign Background ambiguous

21

4 Empirical results and analysis

This section presents the empirical findings based on our data and models as well as the analysis based on these findings.

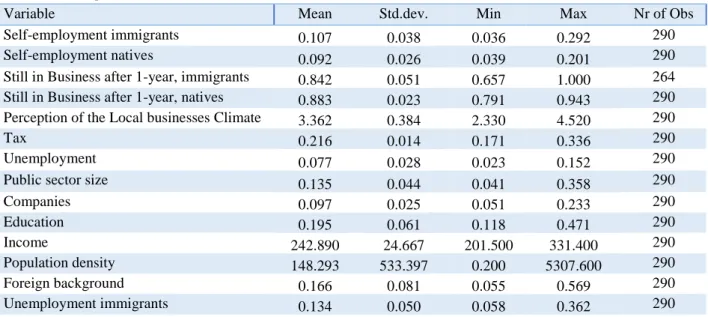

4.1 Descriptive statistics

All variables in the descriptive statistics are presented in their non-logarithmic form. The variables for Self-employment and Still in business after one year show that there is more variation among immigrants than there is for natives. This indicates that the regional differences are quite large in the share of self-employment between municipalities. There is also a large variation in the share of unemployment among immigrants between municipalities as well as in the share of foreign-background in the municipalities. The number of companies per capita and population density show large variations. The municipalities with the largest populations have the highest values for all three variables. Education also shows large variations and the municipality with the largest value is Lund. Lund has a large university and a rather small population which should explain the large share of highly educated. All tax rates are between 17.12 % and 23.9 % except for the municipality Gotland which has the highest tax rate, namely 33.6 %. The reason why this municipality's tax rate is substantially higher than the rest is because this is the tax rate both for the municipality and the county. There is usually one individual tax rate for the municipality and another one for the county. Therefore, Gotland is unique in Sweden since it is classified as both a municipality and a county. Hence, the high tax rate. Since Gotland is an outlier we decided to exclude it from the model, but the results had no significant change.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Variable Mean Std.dev. Min Max Nr of Obs

Self-employment immigrants 0.107 0.038 0.036 0.292 290

Self-employment natives 0.092 0.026 0.039 0.201 290

Still in Business after 1-year, immigrants 0.842 0.051 0.657 1.000 264 Still in Business after 1-year, natives 0.883 0.023 0.791 0.943 290 Perception of the Local businesses Climate 3.362 0.384 2.330 4.520 290

Tax 0.216 0.014 0.171 0.336 290

Unemployment 0.077 0.028 0.023 0.152 290

Public sector size 0.135 0.044 0.041 0.358 290

Companies 0.097 0.025 0.051 0.233 290 Education 0.195 0.061 0.118 0.471 290 Income 242.890 24.667 201.500 331.400 290 Population density 148.293 533.397 0.200 5307.600 290 Foreign background 0.166 0.081 0.055 0.569 290 Unemployment immigrants 0.134 0.050 0.058 0.362 290

22

4.2 Regression results and analysis

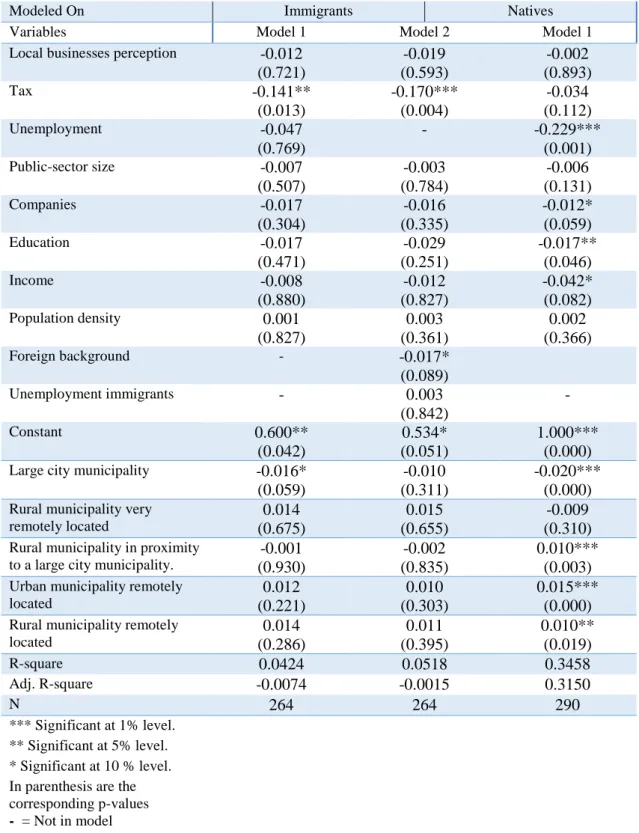

Models 1, 2 and 3 are regressions with the share of self-employed immigrants as the dependent variable while model 4 and 5 have the same independent variables as in model 1 and 2. However, the dependent variable in model 4 and 5 is the share of self-employed natives. In the appendix the corresponding regression results with data from year 2010 are presented.

Table 4. Independent variable: Self-employment. 2015.

Modeled On Immigrants Natives

Variables Model 1 Model 2 Model 1

Local businesses perception -0.140 (0.434) -0.224 (0.149) -0.097 (0.303) Tax -1.296*** (0.005) -1.955*** (0.000) -0.777 (0.119) Unemployment -2.500*** (0.003) - -3.839*** (0.000) Public-sector size -0.358*** (0.000) -0.284*** (0.000) -0.327*** (0.000) Companies 0.006 (0.945) 0.064 (0.397) 0.287*** (0.000) Education 0.335** (0.015) 0.104 (0.369) 0.242*** (0.004) Income -2.329*** (0.000) -2.225*** (0.000) -1.468*** (0.000) Population density -0.036* (0.097) 0.013 (0.587) -0.046*** (0.002) Foreign background - -0.373*** (0.000) - Unemployment immigrants - 0.016 (0.728) - Constant 8.753*** (0.000) 6.149*** (0.000) 5.334*** (0.000) Large city municipality 0.043

(0.489)

0.176*** (0.004)

0.012 (0.802) Rural municipality very

remotely located 0.397*** (0.001) 0.389*** (0.000) 0.167*** (0.003) Rural municipality in proximity

to a large city municipality.

0.040 (0.380) 0.016 (0.707) 0.182*** (0.000) Urban municipality remotely

located 0.016 (0.710) -0.011 (0.812) 0.063* (0.069) Rural municipality remotely

located 0.239*** (0.002) 0.196*** (0.003) 0.199*** (0.000) R-square 0.4242 0.5193 0.6643 Adj. R-square 0.3971 0.4948 0.6485 N 290 290 290 *** Significant at 1% level. ** Significant at 5% level. * Significant at 10 % level. In parenthesis are the corresponding p-values - = Not in model

23

Some of the variables show high correlations. Therefore, in order to confirm that the results are robust we also test to omit some variables to see if any variables change depending on which variables are included, as can be seen in table 8 and 9. The results for education and population density are varying depending on the variables in the model while the other variables are robust. In the first and fourth model, most individual variables show similar significances and directions for both immigrants and natives, which implies that the same factors in the local business climate can partly explain self-employment for both groups. Some variables relate oppositely to the share of self-employed than is hypothesized from theory. One interesting finding is that the R-squared is much lower for employed immigrants than for employed natives; it is 42.4 % for employed immigrants compared to 66.4 % for self-employed natives. This implies that the local business climate, as defined in the literature review section, explains more of the variation in the share of self-employment for natives than it does for immigrants which indicates that the prevailing business climate has a larger influence on

self-employed natives. A possible explanation as to why the business climate influences the

share of self-employed natives more could be because self-employed immigrants tend to use informal networks and means of financing to a larger extent than self-employed natives (Yazdanfar and Abbasian, 2013; Kremel, Yazdanfar and Abbasian, 2014). This is according to the definition of the business climate that we have used in our paper. There are however variables that are omitted in this thesis, such as measuring the local financial institutions which has shown to have a negative effect for immigrant entrepreneurs (Aldén and Hammarstedt, 2014). We have also disregarded factors of how regional differences in infrastructure quality might affect the self-employment as this has been a important factor of local business climate (Tillväxtanalys, 2013), however as this is set on a national level it is hard to quantify the infrastructure for Swedish municipalities.

The third model shows that when we include variables that are more specific for immigrant entrepreneurs, the R-squared improves from 42.4% to 51.9%. The variable representing the share of foreign-background in a municipality has a negative significant relationship with the share of self-employment among foreigners, which supports the theory that ethnical concentration in an area can increase the competition for certain products and services in an area (Andersson and Hammarstedt, 2015). However, we do not know the ethnicities of the foreign business owners and whether there is actual ethnical concentration in different municipalities, so we do not draw any definite conclusions from this information. The

24

unemployment rate among immigrants shows no significant relationship with self-employment at all.

The relationship between the municipal tax rate and the business climate is statistically insignificant for self-employed natives which is in line with the results that Davidsson et al. (1994) and Nyström (2012) find. However, for self-employed immigrants there is a significant negative relationship, which might indicate that well-being in the municipality is much more important for self-employed immigrants than for self-employed native.

The negative relationship between the unemployment rate and the share of self-employed immigrants out of the total number of people who are working is a different result than what is predicted from previous research. The consensus from previous research is that most immigrants that choose to become entrepreneurs do so as a necessity to create earnings, when structural issues in the labour market force them to enter self-employment. Based on this, the share of self-employed immigrants should have a positive relationship with the unemployment rate. A possible explanation to this result is that immigrant entrepreneurs have a larger tendency to employ others (Klinthäll and Urban, 2010), meaning that those people, who could be potential entrepreneurs, enter the regular labour market rather than become self-employed, which would decrease the share of self-employed people relative to the people in the regular labour market. However, this is not a very probable explanation since most previous research suggests that the share of self-employed immigrants should increase as the unemployment rate increases. The relationship between the unemployment rate and the share of self-employed natives out of the total number of people working is significant and negative as well. However, native entrepreneurs do not necessarily become entrepreneurs out of necessity to the same extent as immigrant entrepreneurs. Native entrepreneurs may be more prone to become entrepreneurs due to opportunity seeking, since they do not face the same structural barriers in the regular labour market as immigrants. Hence, as unemployment increases, natives may become less motivated to seek opportunities, hindering them from wanting to become self-employed. The unexpected results could be because we treated those unemployed as a homogenous group and did not take into consideration whether those unemployed were low-skilled or high-low-skilled (Audretsch, Dohse and Niebuhr, 2015). The results could also be because of the correlation between median income and unemployment. As can be seen in table 8, where we exclude the median income the relationship between self-employment and unemployment is positive which might suggest that the results are from multicollinearity.

25

However, this result has low significance and when excluding median income for self-employed natives the relationship with unemployment is still negative.

The public-sectors size has a negative relationship with both self-employed immigrants and self-employed natives, which is in accordance with previous research from Nyström (2008). Our results indicate that the relationship with the municipalities' government sector helps to explain some variation in the share of self-employed immigrants. The similar results between the groups indicate that a large public sector might crowd out some potential entrepreneurs. Whether the result is that there are more jobs available in total in the municipality or that the public sector might scare or crowd out some entrepreneurs is something that cannot be determined from the results in this paper.

The perception of the business climate from local entrepreneurs has an insignificant relationship with the share of immigrant entrepreneurs in as well as for self-employed natives. Nyström (2008) finds this relationship insignificant which supports the result that the relationship between the perception of the local business climate from local entrepreneurs and the share of self-employed immigrants as well as the share of self-employed natives is not significant. Results from 2010 also support this conclusion, although there is a weak negative relationship in model two in 2010. It is possible that the local business climate does not affect the number of firms in a municipality, but rather the endogenous components within the existing firms. The negative relationship might also suggest a limited ability to perceive how well a business climate is for local businesses and makes the accuracy of this survey as a measurement uncertain.

The number of companies in the municipality has no significant relationship with the share of self-employed immigrants. This suggests that other entrepreneurs in the municipality do not influence immigrants' decisions to enter self-employment to the same degree as natives, which have a significant positive relationship. Whether the causation of this insignificant relationship is due to poor social integration of immigrants in some municipalities or some other factor is however hard to establish without further research. On the other hand, this relationship is significant for immigrants in 2010. Further research on the subject could help develop better policies on a municipal level on how to capture this externality for both natives and immigrants. The share of people with a higher education among the municipalities' inhabitants has a significant positive relationship both with the share of self-employed natives and with the share of self-employed immigrants except for in model two. However, the significant results we find

26

can be the result of multicollinearity, since when dropping the variable median income, the share of education becomes insignificant. Thus, the results here should not be viewed as a truly robust and significant.

Median income is negatively related to the share of immigrants that are self-employed. This is in accordance with previous research (see e.g. Andersson, 2011; Hjerm, 2004; Andersson, 2015) which showed that self-employment among immigrant men tends to lead to lower income than being employed in the regular labour market which increases the opportunity cost of entering self-employment. Hence, if the income in the regular labour market increases, it is probable that people will be less willing to become self-employed.

As has already been stated, many immigrants become self-employed out of necessity since the only other option may be to become unemployed (Ljungar, 2007; Reynolds et al., 2004). It is possible that there are less opportunities to find work in the regular labour market in very remotely located rural municipalities (not rural municipalities in proximity to a large city municipality since this showed no significance) which could explain why there is a positive significant relationship between the share of self-employed immigrants out of the total number of people employed and very remotely located rural municipalities. It is possible that work opportunities are scarce in this type of municipality which is why immigrants may be forced to become self-employed. Similar argumentation could be used to explain the positive relationship for all rural municipalities for native entrepreneurs except maybe not to the same extent as for immigrants. That self-employment for native-born as well as for immigrants has a positive significant relationship with municipalities classified as rural further support these results.

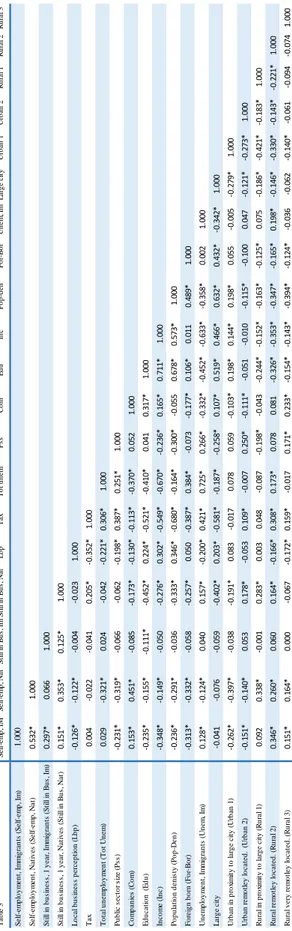

27

The relationship between the local business climate and the share of self-employed immigrants who are still in business after one year is insignificant in all three models. This indicates that our definition of the business climate has no influence on whether immigrant entrepreneurs are still self-employed after one year. The low R-squared supports this result. Hence, the prevailing business climate only appears to affect the share of self-employed immigrants who are in the

Table 5. Independent variable: Still in business after one year. 2015.

Modeled On Immigrants Natives

Variables Model 1 Model 2 Model 1

Local businesses perception -0.012 (0.721) -0.019 (0.593) -0.002 (0.893) Tax -0.141** (0.013) -0.170*** (0.004) -0.034 (0.112) Unemployment -0.047 (0.769) - -0.229*** (0.001) Public-sector size -0.007 (0.507) -0.003 (0.784) -0.006 (0.131) Companies -0.017 (0.304) -0.016 (0.335) -0.012* (0.059) Education -0.017 (0.471) -0.029 (0.251) -0.017** (0.046) Income -0.008 (0.880) -0.012 (0.827) -0.042* (0.082) Population density 0.001 (0.827) 0.003 (0.361) 0.002 (0.366) Foreign background - -0.017* (0.089) Unemployment immigrants - 0.003 (0.842) - Constant 0.600** (0.042) 0.534* (0.051) 1.000*** (0.000) Large city municipality -0.016*

(0.059)

-0.010 (0.311)

-0.020*** (0.000) Rural municipality very

remotely located 0.014 (0.675) 0.015 (0.655) -0.009 (0.310) Rural municipality in proximity

to a large city municipality.

-0.001 (0.930) -0.002 (0.835) 0.010*** (0.003) Urban municipality remotely

located 0.012 (0.221) 0.010 (0.303) 0.015*** (0.000) Rural municipality remotely

located 0.014 (0.286) 0.011 (0.395) 0.010** (0.019) R-square 0.0424 0.0518 0.3458 Adj. R-square -0.0074 -0.0015 0.3150 N 264 264 290 *** Significant at 1% level. ** Significant at 5% level. * Significant at 10 % level. In parenthesis are the corresponding p-values - = Not in model

28

start-process; not the survival of the business. It is possible that immigrants export more than natives, if they utilize connections abroad, which could make the survival of their businesses less dependent on the business climate which could also explain the insignificance of the relationship. However, this is highly speculative and further research on what determines immigrant owned businesses' survival on a regional level must be done to establish if the regional conditions matter for self-employed immigrants. Further research should also be conducted in this area to investigate which factors that contribute to the survival of immigrant owned businesses in a longer perspective than one year.

For natives, unemployment, income, education and companies is statistically significant, however only unemployment has a strong significant relationship with self-employed natives who are still in business after one year. The fact that there is a negative significant relationship between median income and the share of self-employed natives who are still in business after one year indicates that municipalities that have high median wages in the regular labour market might incentivize business owners to enter the regular labour market rather than continue running the business. Similarly, low unemployment might increase the probability of finding work, leading to self-employed abandoning their businesses for employment in the regular labour market. The share of highly educated in the municipality is significant in 2015 but not in 2010 which might be because of multicollinearity reasons previously discussed. Companies per capita have a weak negative significant relationship which might suggest that entrepreneurs may not be influenced by the entrepreneurial spirit in only one year's time. However, it may also be due to high competition in the local market which makes it harder for the self-employed natives to stay in business.

The most striking result is that the local business climate is relevant for native business owners when deciding to stay in business or not whereas it is insignificant for immigrant business owners. This result supports the previous theory that the local business climate and its functions are more available to natives than to immigrants, which could be due to structural barriers such as a higher degree of rejections on bank loans as mentioned before.

29

5 Conclusions

This paper investigates the relationship between the local business climate and the share of immigrants who are self-employed out of the total number of people working in different municipalities in Sweden. It also investigates whether there are any differences in how the local business climate relates to the share of self-employment between self-employed immigrants and self-employed natives. To test this, we based our models on variables previously used when measuring the relationship between the business climate impact and self-employment. Because most literature on the subject of self-employment among immigrants in Sweden finds that most immigrants enter self-employment because they cannot find employment in the regular labour market, the model also includes the unemployment rate. The same regressions are then run on the share of self-employed immigrants as well as natives who are still running a business after one year to see if the local business climate influences the decision to continue running a business and whether there are any differences between natives and immigrants.

We find significant negative relationships for the municipal tax rate, the public-sector size, the unemployment rate, median income and habitants share of foreign background with the share of self-employed immigrants. The number of companies in a municipality, local business perception and share of unemployment among immigrants had an insignificant relationship. The variables education and population density vary between significance and insignificance depending on whether the model is general or immigrant specific. Hence, there appear to be regional variations in the share of self-employed immigrants which is due to differences in the local business climate. In light of this, the local business climate influences the share of self-employed immigrants. However, the prevailing business climate in a given municipality has a stronger relationship with the share of self-employed natives than with self-employed immigrants of out of the total working population. One reason why the business climate is less significant for self-employed immigrants than for self-employed natives could be because of obstacles in the business climate for immigrant entrepreneurs, such as more rejections on bank loans, higher interest rates on loans, and less access to formal networks.

One of the immigrant specific factors of self-employment that previous literature has examined that we use in our regression, the share of foreign-background, show opposite directions in our results than what is predicted. The unemployment rate for immigrants is insignificant.

When we tested regional differences for self-employed immigrants who were still in business after one year the variables in the business climate were insignificant which indicates that the

30

local business climate does not affect survival rates in the short-run. However, future research should investigate the business climate and the share of self-employed immigrants in a longer perspective. It might also be of interest to look at how the local business climate affects people who are self-employed from different ethnicities. In our study we have generalized all immigrants, that is all people who are born outside of Sweden, but it is likely that the business climate is more available to certain ethnicities and more excluding to other ethnicities.

In this paper we only look at data at one point in time when we assess the relationship between the local business climate and the share of self-employed immigrants due to limitations in data from other years. Therefore, an area that can be explored further is to examine this relationship over time which would strengthen the conclusions about which factors in the business climate that affect the share of self-employed immigrants. In addition, we examine the relationship between the share of self-employed immigrants who are still in business after one year and the business climate. It could be argued that one year is not enough time after the start-up process to make any assessments about this relationship in a longer perspective. We used the best data that was available to us, but it would be interesting to examine the survival rate of the businesses in an even longer perspective. Hence, this area can also be explored further.

The findings in this study can help policy makers when trying to integrate immigrants. For instance, policy makers should facilitate the networking process for immigrants which could help immigrants to interact with natives through business networks. Also, since the study finds a positive relationship between rural municipalities and the share of self-employed immigrants, perhaps immigrants should be placed in rural municipalities. However, this does not take into account the individual's preferences and wishes. It can be considered inhumane to place a person in a rural municipality where there may not be as many opportunities as in more populated areas. Perhaps politicians can try to attract immigrant entrepreneurs to less populated areas where the politicians wish to see an increase in the level of entrepreneurship through some sort of benefit, rather than placing them in those areas and force them to self-employment.