Department of Computer Science 205 06 Malmö, Sweden

Degree Thesis

15 Credits, Undergraduate Level

T

HE

D

IGITAL

W

ORKPLACE

–

Integrating Chaotic Knowledge Processes

DEN DIGITALA ARBETSPLATSEN –

integrering av kaotiska kunskapsprocesser

Victor Åkerblom

Degree: Bachelor of Science 180 Credits Major: Information Systems

Programme: Business Information Systems

Supervisor: Dr. Marie G. Friberger Examiner: Prof. Bengt J. Nilsson Date of final seminar: 28 May 2012

2

Creating knowledge from infor-

mation is a process of refinement

-Hampus, QlikTech

3

Abstract

This thesis provides contemporary insights how knowledge management can be approached by a knowledge-intensive organisation. Knowledge workers today have unprecedented means to collaborate in different spaces of knowledge sharing. By analysing the case of QlikTech, results indicate that knowledge management is an integral part of knowledge-intensive organisations.

By adapting an interpretive approach, eight semi-structured qualitative interviews with employees at QlikTech are analysed to find out how different information systems support different knowledge and collaboration processes. The interviews are complemented by on-the-job observations and analysis of documents to reach deeper understanding.

Results indicate that users use systems with predefined structures to document official knowledge, and systems with emergent structures for informal dialogue and collaboration. Different systems complement each other, as knowledge is transferred between systems. Grass root initiated information systems compensate for the gap between official technology implementations and the social communication needs. Technology and practice co-evolve. As discussions, ideas, perspectives and context can be sustained in emergent social software platforms, such as Salesforce.com, complex problem-solving can be enabled in computer-supported cooperative work. These platforms minimise the gap between the formal and social communication within communities of practice, which facilitates organisational learning.

At QlikTech, digital communities emerge organically over time. Organisations can use data and text mining, natural language processing and information extraction technologies to bridge fragmented communities to gain the capabilities to access dispersed knowledge sources through search. Organisations can add a social layer of these fragmented back-end systems, designed for building cross-functional employee-facing communities that drive collaboration and accelerate innovation in the workplace.

Keywords: Knowledge management, computer-supported cooperative work, comm-unity of practice, emergent social software platforms

4

Resumé

Genom fallet QlikTech ger denna uppsats en aktuell inblick i hur kunskaps-hantering kan hanteras i en kunskapsintensiv kontext. Medarbetare har i dag möjligheter att samarbeta inom olika interaktiva digitala miljöer för att hitta och dela med sig av kunskap och erfarenheter. Denna uppsats fokuserar på att undersöka hur digitala communitys uppkommer, växer fram och integreras för att uppnå global kunskapsdelning inom organisationer. Detta ses som en framgångs-faktor för att ta vara på kunskapsintensiva utvecklingsföretags kretivitet och innovationskraft.

Genom ett tolkande tillvägagångssätt, analyseras åtta semistrukturerade kvalit-ativa intervjuer med medarbetare på QlikTech för att undersöka hur olika informationssystem används för att stödja olika kunskaps- och kollaborations-processer. Intervjuerna kompletteras med observationer and dokumentanalyser för att nå djupare insikter.

Resultaten tyder på att användare använder system med fördefinierade strukturer för att dokumentera officiell kunskap, och system med framväxande strukturer för informell dialog och samarbete. Olika system kompletterar varandra, då kunskap förs över mellan system. Gräsrotsinitierande informationssystem kompenserar för glappet mellan officiella IT-implementationer och sociala kommunikationsbehov. Teknologi och praktik utvecklas hand-i-hand. Då diskussioner, idéer, perspektiv och kontext kan upprätthålls i emergent social software platforms, t.ex. Salesforce.com, kan komplext problemlösande underlättas i datorstött samarbete. Dessa platt-formar minimerar glappet mellan den formella och sociala kommunikationen inom communities of practice, vilket ger förutsättningar för organisatorisk lärande.

På QlikTech växer digitala communitys fram organiskt över tid. Organisationer använder data- och text mining och relaterade teknologier för att brygga fragment-erade communitys för att uppnå kapacitet att nå isolfragment-erade kunskapskällor genom sökning. Organisationer kan lägga till sociala lager över dessa fragmenterade back-end-system, designade för att bilda övergripande gränssnitt mot användare som underlättar samarbete och driver på innovation inom arbetsplatsen.

Nyckelord: Kunskapshantering, datorstött samarbete, community of practice, emergent social software platforms

5

Acknowledgements

I especially would like to thank Zaida at QlikTech who generously and tirelessly gave me the chance to make a meaningful and exciting case study as the foundation of my degree thesis in information systems. I would also like to thank the interviewees who enthusiastically participated in this study and openheartedly answered all my questions. Without your contributions, this study would never have seen the light of day.

I would also like to thank Marie Friberger, my supervisor, who’s insightful and deep knowledge in the field has given me the inspiration and guidance needed to finalise this thesis. Thank you for your detailed feedback, constructive criticism and supportive pushes in the right direction! Further, Bengt J. Nilsson gave valuable comments in terms of language.

Thank you all!

May 2012, Malmö Victor Åkerblom

6

Table of Contents

1. Introduction... 8 1.1 Problem Description ... 8 1.2 Research Questions... 9 1.3 Purpose ... 10 1.4 Delimitations ... 10 1.5 Thesis Outline ... 11 2. Theoretical Framework ... 12 2.1 Knowledge Management ... 122.1.1 Knowledge as Source of Innovation ... 12

2.1.2 Data, Information, Knowledge and the Importance of Context ... 13

2.1.3 Tacit Knowledge, Explicit Knowledge and the Creation of New Knowledge ... 14

2.1.4 From Documenting to Discussing ... 16

2.1.5 Social Capital and Capacity to Collaborate ... 17

2.2 Computer-Supported Cooperative Work ... 18

2.2.1 Communities of Practice for Shared Contexts ... 18

2.2.2 Stickiness of Knowledge ... 19

2.3 Information Systems to Support Knowledge Management ... 21

2.3.1 Overview of Knowledge Management Systems ... 21

2.3.2 Chaotic Knowledge Dialogues vs. Systemic Information Proc-esses ... 22

2.3.3 Emergent Social Software Platforms ... 23

2.3.4 Changing Roles in Enterprise 2.0 ... 25

2.4 Summary of Theoretical Framework ... 26

3. Methodology and Research Design ... 29

3.1 Case Study as Research Strategy ... 29

3.2 Qualitative Data Collection ... 29

3.2.1 Qualitative Triangulation Approach ... 30

3.2.2 Semi-structured Qualitative Interviews ... 31

3.2.3 Observation of Behaviour ... 32

3.2.4 Document Collection and Analysis ... 33

3.3 Approach to Analyse Data ... 33

4. Results and Analysis ... 34

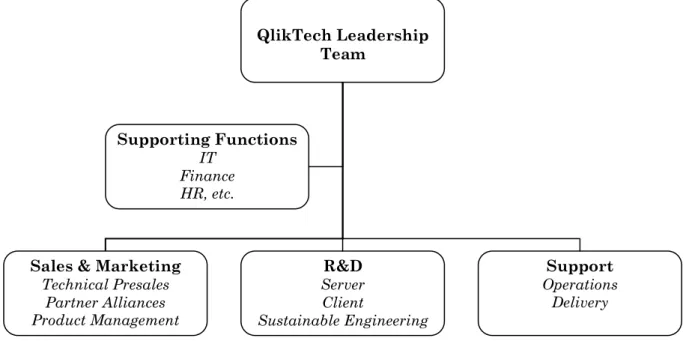

4.1 Case Description ... 34

4.1.1 About QlikTech ... 34

4.1.2 Project Q 2.0 - The Social Intranet ... 36

4.2 Emerging Digital Communities ... 37

4.2.1 Formation of Fragmented Communities of Practice ... 37

7

4.2.3 Grass Root Initiated Wiki ... 39

4.2.4 Adoption of Knowledge-Centred Support ... 40

4.3 Integrating Various Knowledge Processes ... 41

4.3.1 Overview of Information Systems at QlikTech ... 41

4.3.2 Usability Test of Q ... 44

4.3.3 Bridging Communities for Global Knowledge Sharing ... 47

4.3.4 Knowledge Sharing Across Borders ... 48

4.3.5 Designing Cross-Border Information Flows for Innovation... 52

4.4 Emergent Problem-Solving ... 53

4.4.1 Complementary Use of Documents and Discussions ... 53

4.4.2 Emerging Contexts for Complex Problem-Solving ... 56

5. Discussion and Conclusion ... 58

5.1 Quadrant of Emergent Social Software Platform – Theory and Practice ... 58

5.2 Conclusions... 59

5.2.1 Different Knowledge in Different Systems ... 59

5.2.2 Integrating Emerging and Fragmented Communities ... 60

5.2.3 Social Problem-Solving ... 61

5.3 Reflections ... 62

5.4 Future Work ... 62

References ... 64

Appendices ... 67

Appendix 1: Interview Guide, Users ... 67

8

1. Introduction

The digital workplace is evolving. New tools are doing old things, as knowledge workers have unprecedented means to collaborate in different spaces of knowledge sharing, and in real time find the information they need to solve problems. Organisations deploy a variety of information systems to support the creativity and innovation of workers, as knowledge management aims to identify, create, represent, distribute, and enable adoption of insights and experiences (Nonaka 1991).

In this thesis some current challenges within knowledge management are investigated from an information systems perspective by looking at the case of QlikTech, a knowledge-intensive software development company. The thesis takes its departure from the fundamental question how knowledge is shared in different contexts, and how information systems are used in different stages to create, share and sustain new knowledge within organisations.

Specifically, the thesis aims to show how the emergence of context can be supported to enable unstructured problem solving; how rigidity and emergence of systems support different knowledge processes; and how fragmented digital communities can be bridged to enable global knowledge sharing within organisations. These are important areas of knowledge management for organisations to understand in order to design information flows that encourage cross-border collaboration and innovation.

1.1 Problem Description

The following presents and motivates the research questions (RQ) which are established in Section 1.2.

Knowledge intensive organisations operate in rapidly changing environments and workers are expected to solve unstructured and complex problems. Problem solving is a process that is influenced by the problems solvers, their background and understanding, the environment in which they exist and the emerging context where problems become situated (Augier et al. 2001). This is reflected by the latest developments in social software in the workplace; today’s systems have emergent structures to support activity streams that are dynamically updated by user activity, by other system events and by information from external systems (Drakos et al. 2011).

More rigid information systems are deployed to support document sharing, wikis, blogs and corporate intranets. These systems, though, often have interactive components as these have been recognised as important to enable creation of new knowledge (Davenport & Prusack 2000; Duguid 2005). The communication channels

9

and collaboration platforms in today’s digital workplace open up many possibilities, but also raise some critical questions. Different systems are used for different purposes; Research question one aims to reach understanding about what different kind of knowledge is created, shared and sustained in self-organising emergent feeds versus predefined structured content.

The goal of many knowledge management initiatives is to develop a global knowledge community where knowledge is shared and utilised across the organisations as a whole. As organisations grow, communities of practice evolve and bring together groups of people informally bound together by shared expertise in various areas (Wenger & Snyder 2000). It has been recognised that multiple channels and platforms are needed in order to accommodate diverse knowledge sharing needs and preferences (Shan & Leidner 2003). Less research has been done to show how different communities of practice within organisations emerge and how they can be integrated by information systems to enable global knowledge sharing, with IT as an overall knowledge infrastructure. The purpose of research question two is to investigate how digital communities emerge and how information systems can be used in enabling the bridging of communal knowledge resources (van Krogh 2002).

Theoretically, social software with its emergent qualities should provide platforms to support collaboration to solve complex and unstructured problems, as this involves the reworking of previous ideas and knowledge to new and unanticipated situations (Augier et al. 2001). This leads us to research question three, which aims to investigate how emergent social software platforms with their high level of interactivity help teams to solve complex and unstructured problems, as the lack of interactivity is often ascribed to why traditional knowledge management systems fail (Alavi & Leidner 1999).

1.2 Research Questions

Based on the problem discussion above, this thesis aims to answer the three research questions listed below.

RQ1: What different kind of knowledge is created, shared and sustained in self-organising emergent systems versus predefined structured systems?

RQ2: How do fragmented communities of practice emerge and how can they be integrated to enable global knowledge sharing within organisations?

RQ3: How are emergent social software platforms used to solve unstructured problems among knowledge workers?

10

1.3 Purpose

As knowledge intensive organisations continuously need to innovate to stay comp-etitive (Steiber 2012), they are interesting to study in terms of how they approach knowledge management problems, which aim to identify, create, represent, distribute, and enable adoption of insights and experiences (Nonaka 1991). The purpose of this thesis is to probe theory gaps related to the research questions listed above.

1.4 Delimitations

Knowledge management is a broad and inter-disciplinary area, covering subjects as information systems, computer science and business administration. This thesis focuses on the information systems and the processes used by organisations to enable cross-functional knowledge sharing, social collaboration and problem solving. The technology enabling this is only briefly mentioned, as this is beyond the scope of this thesis.

11

1.5 Thesis Outline

Introduction

In this chapter a brief introduction to the scope of the thesis is presented, follow-ing a presentation of the research area around knowledge management and a problem discussion leading to the research questions. Also the purpose and research delimitations are outlined.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework introduces the reader to the implications of knowledge management theory, and then goes on to show how shared context in computer-supported cooperative work is an important aspect in terms of knowledge creation in the enterprise. The discussion is concluded with an outlook of emergent social software platforms.

Methodology and Research Design

In this section, the choice of case study research strategy is motivated, and data collection methods are described. Also the method to analyse the collected empirical data is explained to strengthen the scientific reliability of the findings.

Results and Analysis

This section gives an introduction to the case study, with information about QlikTech and the Q 2.0 project. Subsequently the empirical findings are presented, interpreted and analysed in relation to the research questions.

Discussion

The main findings are discussed, summarised and presented using a four category model of information systems supporting knowledge management.

Conclusions

Conclusions are drawn from the analysis of the study and the research questions are answered. The choices of methods are critically discussed and advice is given for further research.

12

2. Theoretical Framework

Since the early 1990s, extensive research has been made in what has become known as knowledge management, and its various applications in today’s organisational context. In this chapter, an attempt is made to give a critical overview of key concepts that lay the foundation of contemporary problems faced by organisations that relate to our research questions. The spectrum of the knowledge management research field is broad, while we focus on the information systems enabling the creation and sharing of knowledge here.

2.1 Knowledge Management

Why do organisations engage in knowledge management projects in the first place? In this chapter we briefly look at the expected benefits of information systems designed to support knowledge management. We will also attempt to define the concept in order to frame our understanding of computer-supported cooperative work (Ackerman 2000) and contemporary attempts to implement emergent social software platforms (McAfee 2011).

2.1.1 Knowledge as Source of Innovation

What are the purposes of knowledge management and why are the ideas behind the concept a source for innovation in the way we work and collaborate? The driving forces behind knowledge management, and related fields such as intellectual capital, learning organisations and social collaboration, are all rooted in the action of creating value to support the overall organisational goals (Patrash 2000). The role of information systems to achieve these goals is clear: to enable communities to overcome time and space constraints in knowledge sharing and increase the speed and range of access to information (van Krogh 2002).

Motivations and expected benefits tend to relate to more efficient processes where knowledge is seen as driver for innovation to produce creative thoughts, products and services, as well smarter ways of working (Takeuchi & Nonaka 1995). It also aims to encourage how knowledge is shared amongst workers, so that organisations can improve some quality aspect, e.g. better customer service. Organisations see knowledge management as an important way to be more successful in what is sometimes called the information age or knowledge economy.

Looking at a strategic level, Skyrme (2000: 64) suggests that there are two major fundamentals in which knowledge is expected to support the business strategy. The first fundamental is to make acquired knowledge more accessible across the organ-isation, as a measure to realise statements like “if only we knew what we knew”.

13

Potential technologies to support this can be sharing of best practices through lessons learnt databases or intranets to access under-utilised knowledge in new situations. The second fundamental of which Skyrme (2000) considers knowledge to be a critical factor is innovation, which further reiterates Takeuchi & Nonaka’s (1995) perspective on knowledge management: It is through the creation of new knowledge in which new products or services and more efficient and effective processes can be innovated and commercialised.

What are the potential benefits of engaging in knowledge management? Skyrme (2000) suggests that by applying knowledge management, sharing of best practices is made possible by taking the best performance and applying it in similar situations elsewhere. This enables faster problem-solving and faster development times by creating learning networks, leading to further benefits. For instance, the possibility of gaining new business as knowledge is increased making it possible for consultants to combine their collective knowledge and respond to bids quicker, to give just one example.

2.1.2 Data, Information, Knowledge and the Importance of Context

As demonstrated by the examples mentioned above, there is a close link between

information stored in various information systems and what is referred to as knowledge. This brings us to a central theme in knowledge management and the

problems associated with its applications. The expressions are often used inter-changeably in everyday discourse. However for the purpose of understanding the challenges associated with knowledge management it is important to see the difference.

Classic differentiation is made between data, information and knowledge (Ackoff 1989) where knowledge is said to be “justified belief” (Takeuchi & Nonaka 1995: 141) and can be described as “information combined with experience, context, inter-pretation and reflection” (Davenport et al. 1998: 43). This distinguishes knowledge as it is considered a higher valued form of information, enabling the “the capacity to act” (Sveiby 1997: 23). A key difference, then, is that knowledge is context-specific, meaning that there are potentially vital details around pieces of information which make it difficult to reproduce unless the context is known (Junnarkar 2000).

This relationship can be better illustrated using an example: many organisations use document management systems1 to capture, organise, store, retrieve and browse documents. Such systems are updated with pieces of content by individuals, however, as context is typically experiential by nature, it is difficult to capture and share through a digital document. The same problems are encountered when updating knowledge databases, as Skyrme (2000: 75) notes it may “filter out some of

14

the key ingredients that distinguish knowledge from information – contextual richness, the human cognitive dimension and tacit knowledge”. This brings us to an important insight: it is easy to remember context, and from it reproduce content, as opposed to reconstructing context by looking at content (Junnarkar 2000).

As human knowledge and machine information are two separate things (Duguid 2005), this calls for platforms that to a greater extent support human behaviour and the way context is shared in real life conversation and other forms of social interaction. Attempts to design knowledge management systems with the purpose of eliciting knowledge, best practices and experiences from individuals and store them in widely available databases are not widely used in today’s business context (McAfee 2006). As social activity is fluid and nuanced it makes systems technically difficult to construct (Ackerman 2000). Whether or not this need is met through what McAfee (2006) refers to as emergent social software platforms is difficult to establish – although these platforms in theory resemble more dynamic communities of practice to sustain social context (Böhringer & Richter 2009). In order to reach further understanding of this potential relationship, we need to look at another central theme in knowledge management: Distinguishing between tacit and explicit knowledge.

2.1.3 Tacit Knowledge, Explicit Knowledge and the Creation of

New Knowledge

As discussed earlier, the purpose of knowledge management includes the achievement of innovation and organisational learning. There are, however, two types of knowledge, tacit and explicit, which interact with each other in order to result in new knowledge being created and hence innovation taking place (Takeuchi & Nonaka 1995). Building on our argument that information needs to be allocated in the right context in order to be meaningful, knowledge creation can be viewed from a perspective of social constructivism. This suggests that “reality” is merely a result of individuals and groups recreating their surroundings and attaching artefacts with meaning (Watson 2006).

When looking at creation of new knowledge, Takeuchi & Nonaka (1995) brings forward new epistemology when recognising tacit knowledge as a category of know-ledge. Tacit knowledge can be described as highly personal, context-specific insights, intuitions and hunches, and therefore hard to formalise into explicit knowledge. It is, for example, hard to articulate how to ride a bicycle, which can be described as the result of applying tacit knowledge to a situation. Tacit knowledge is displayed or exemplified but difficult to transmit; we learn how by practice and that by acquiring explicit, codified knowledge (Duguid 2005). The importance of context is once again reiterated as “new knowledge is created out of existing knowledge through the

15

change of meanings and the contexts” (Nonaka et al. 2000: 8 in Augier et al. 2001: 128).

Explicit knowledge can consequently be described as “embodied” information (Skyrme 2000: 65) and can be codified, written down, stored in information systems and be expressed in a more tangible form. Explicit knowledge, as opposed to tacit, can be expressed in words or numbers and disseminated around an organisation. However – to use a popular analogy – the kind of explicit knowledge that can be stored in e.g. a knowledge database, only represent the “tip of the iceberg of the entire body of knowledge” (Polanyi 1966, in Takeuchi & Nonaka (1995: 60).

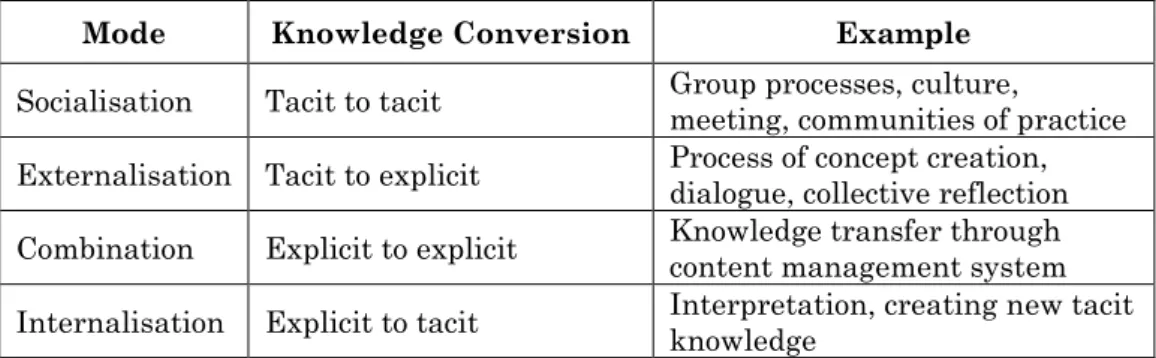

The iceberg analogy helps us to understand that we know more than we can tell. Therefore the ability to capture tacit knowledge becomes important, as it is by its conversion into explicit knowledge in which new knowledge is created (Takeuchi & Nonaka 1995). The conversion is described as the interaction between tacit and explicit knowledge which takes places as a social process between individuals. In their SECI model, Takeuchi & Nonaka (1995) illustrate how this interaction occurs by referring to the four modes of socialisation, externalisation, combination and internalisation of tacit and explicit knowledge, as described in Table 1.

Table 1: Explaining the SECI model (Takeuchi & Nonaka 1995)

Mode Knowledge Conversion Example

Socialisation Tacit to tacit Group processes, culture, meeting, communities of practice Externalisation Tacit to explicit Process of concept creation, dialogue, collective reflection Combination Explicit to explicit Knowledge transfer through content management system Internalisation Explicit to tacit Interpretation, creating new tacit knowledge

As we have discussed previously, much on the contextual richness is lost when updating information systems in attempts of codifying knowledge into explicit form. Skyrme (2000: 71) goes as far as calling attempts to manage tacit knowledge an “oxymoron”, due to its intangibility. Furthermore, the internalisation of explicit knowledge into tacit knowledge is what Junnarkar (2000) describes as the reconstr-uction of context by looking at content, which is similarly difficult to diffuse. By taking part of explicit, codified information we know that, however this does not per se produce knowing how (Duguid 2005). As the externalisation and internalisation of knowledge are crucial modes in order for organisations to innovate (Takeuchi & Nonaka 1995), we need to look closer at ways that these processes can be supported. Nonaka (1991) argues that tacit knowledge is serendipitous by nature, meaning that its discovery is unexpected and can result in unforeseen benefits (Oxford Dictionary

16

of English 2012). This insight strengthens the notion that innovation does not happen from simply processing information, but points to the importance of sharing intuitions and hunches by individuals and making those insights available for collaboration with others. Indeed, the serendipity of tacit knowledge makes its management an oxymoron (Skyrme 2000); a more valid question is how the socialisation mode described in Figure 1 can be supported and hence new knowledge created.

2.1.4 From Documenting to Discussing

The existence of tacit and explicit knowledge is widely accepted; however their relationship to each other is more complex and need further explanation. The notion that the latter can be transformed into explicit by articulating it is debated. The iceberg model also suggests that all knowledge have tacit components and as such cannot be converted into explicit knowledge (Tsoukas 2003). This view argues that explicit knowledge is not simply the results of externalised tacit knowledge. In the same logic, tacit knowledge is not simply internalised explicit knowledge. Tsoukas (2003) criticise Takeuchi and Nonaka of reducing knowledge to commodities and ideas are seen as objects that can be extracted from people. Instead, tacit and explicit knowledge are complementary to each other; the articulation of knowledge is a continuous process which requires pre-understanding and thus the results of interpretations (Ibid 2003).

Traditionally, tacit knowledge is more easily shared in socialisation mode by obser-vation, personal communication, demonstration, on-the-job learning, etc. – activities which are usually carried out in real life situations. Therefore, attempts should be made to enhance tacit knowledge flow through better human interaction (real life or digital) so that such knowledge is diffused around the organisation and not held in the heads of few (Skyrme 2000). Consequently, attempts to capture tacit knowledge should shift focus from documents to discussions (Davenport & Prusack 2000). Before elaborating further on this argument, we need to summarise this discussion by defining the concept of knowledge management. As there is no universal definition, Seeman’s et al. (2000: 89) will be used throughout this thesis:

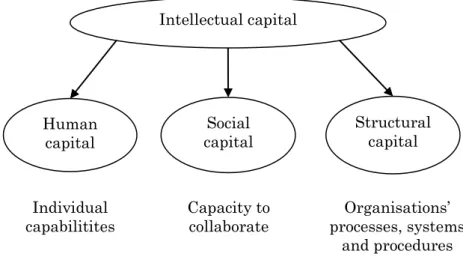

The deliberate design of processes, tools structures etc., with the intent to increase, renew, share, or improve the use of knowledge represented in any of the three elements of intellectual capital.

The definition introduces what is referred to as the three elements of intellectual capital (see Figure 2 on next page). The model will be briefly explained in the next chapter which further builds on the argument that knowledge management can be approached in two ways; either by focusing on organising collaborative communities,

17

or on more structured processes of knowledge creation, sharing, and distribution (Leidner, Alavi & Kayworth 2006).

2.1.5 Social Capital and Capacity to Collaborate

Knowledge can be seen as intangible assets of organisations, assets out of which knowledge management activities aims to build intellectual capital (Seeman et al. 2000). This rather economical view of knowledge creation again strengthens the presumed rationale behind engaging in strategic knowledge management projects; the action of creating value to support the overall organisational goals (Patrash 2000).

However, within the scope of this thesis we are interested in the technologies and processes which enable these value creating activities, i.e., the information systems deployed to facilitate knowledge sharing. We will use the model presented in Figure 1 to illustrate how activities in knowledge management contribute to the increase in intellectual capital. The model uses a holistic perspective of value creation taking all possible activities into account.

Figure 1: Key components of intellectual capital (Based on Seeman et al. 2000: 87)

The three elements all contribute to what Seeman et al. (2000) refer to as intellectual capital. Human capital involves the individuals who contribute within organisations and the structural capital include the systems and processes designed to support individuals to carry out their daily tasks, such as finding information in databases, document management systems.

The third element, social capital, can be viewed as the glue that brings the other two together and makes intellectual capital building possible. Social capital describes the

Intellectual capital Human capital Structural capital Social capital Individual

capabilitites Capacity to collaborate processes, systems Organisations’ and procedures

18

way people work together, build networks and webs of trust, negotiate meaning around artefacts and is hence an important aspect of knowledge creating activities. To learn how the social capital can be realised, we need to look as computer-supported cooperative work.

2.2 Computer-Supported Cooperative Work

In this chapter, we will specifically look at computer-supported cooperative work and its role in creating, diffusing and sustaining knowledge. As teams often are geographically distributed this kind of real-life social interaction is difficult to achieve. Instead, teams engage in computer-supported cooperative work (Ackerman 2000). As knowledge has important tacit components (Tsoukas 2003), its under-standing and interpreting resides on individual skills, underunder-standing, collaborative social arrangements, but also in the tools, systems and processes that embody knowledge (Wenger & Snyder 2000).

As teams in today’s organisations are often geographically distributed, the way we collaborate in projects online has in important role in knowledge sharing. Although taking a variety of shapes and forms, computer-supported cooperative work involves key aspects of the challenges faced in knowledge management, as we shall see. One such example is the re-contextualisation of information. We will frame this chapter by referring to the definition of knowledge management as provided by Seeman et al. (2000), and further discuss how computer-supported cooperative work plays in integral role in the three elements of intellectual capital

2.2.1 Communities of Practice for Shared Contexts

Information systems often assume shared understanding of information. Therefore, the capacity to collaborate, digitally interact and engage in other trust-enhancing activities is important in order to encourage the sharing of information to others. In this way, experience and knowledge can be reused and applied to new business situations (Ackerman 2000). Potential technical mechanisms to augment such social trust-enhancing mechanisms are chat and comment functions. These allow interactivity among the users of the information systems, and potential norm creation within the community can be made2. When the knowledge source and the knowledge recipient share the same context and are engaged in the same practice, high level of trust can be reached. This enables the possibility of mutual understanding and socialisation of tacit knowledge (Wenger & Snyder 2000; Tsoukas 2003).

2 Taking Facebook as an example, it is considered norm today to congratulate friends on their

19

This brings us to the concept of communities of practice, which can be defined as a setting where “groups of people informally bound together by shared expertise and passion for a joint enterprise” (Wenger & Snyder 2000: 139). When individuals share knowledge in such communities, boundaries tend to be transcended and external experts are drawn in to solve problems. In theory, it is through such communities of practice that true collaboration, learning and innovation can take place.

Computer-supported cooperative work may increase the quality of the knowledge creation when conducted in communities of practice, by enabling a digital forum for constructing and sharing beliefs, confirming consensual interpretation, and for expressing new ideas (Alavi & Leidner 1999). It is through the extended field of interaction among the members of the community of practice for sharing persp-ectives and establishing dialogue that information systems enable individuals to arrive at new insights and more accurate interpretations.

As most definitions of communities of practice stress the importance of shared practice, repertoire, interests and knowledge; the informality and self-organising characteristics of the community are closely linked to the social capital element of achieving intellectual capital, which reminds us of the definition of knowledge man-agement by Seeman et al. (2000).

As the knowledge sharing can take place within the community of practice rather than around the copying machine, during coffee breaks etc., the objectification of new knowledge may be better diffused as it is articulated or shared in digital form, such as pictures, numbers, diagrams etc. As the externalisation of tacit knowledge and internalisation of explicit knowledge is made visible, this enables learning from others and more efficient problem-solving as groups do not have to reinvent the wheel when facing situations others have faced before (Ackerman 2000).

From this perspective, communities of practice support the capacity to collaborate and thus contribute to the intellectual capital through organisational innovations (Seeman et al. 2000). Furthermore, Steiber (2012) points to the sustainability of organisational innovation and argues that the process of creating, diffusing and sustaining knowledge is an intertwined process as organisational innovations are continuously reinvented. Therefore, communities of practice with their emergent qualities can be seen as dynamic improvement trajectories where knowledge can be generated and renewed (Wenger & Snyder 2000).

2.2.2 Stickiness of Knowledge

As discussed, the tacit component of knowledge makes its sharing to others complex. Communities of practice facilitate knowledge sharing amongst its members as members share context and common practice. This makes the communication richer and they can collaborate to reach mutual understanding to solve certain problems.

20

However, organisations use multiple information systems which make knowledge sharing between departments a challenge as both the source and recipient of the knowledge need to adjust and interpret the sharing. The transfer costs of disembedding knowledge from one practice and reembedding it in another, Szulanski (2003) call the stickiness of knowledge.

Szulanski (2003) argues that people on the source side might be reluctant to share knowledge as this means losing ownership, privilege, superiority or that they lack the time to do so. People might also be unaware of the importance their knowledge might have to others, which again reminds us of the serendipitous nature of the tacit. In the same way, people might be reluctant to absorb the knowledge of others (Ibid 2003).

Furthermore, depending on the circumstances and the culture within the organisation, the work might get more formal and the willingness to share might be reduced when conducted within a community of practice as it is exposed to others, such as management (Ackerman 2000). Users can experience uncertainty whether managers will value their participation in the community or if they will assume that they users are not interested in their “real jobs” (McAfee 2011). People prefer to know who else is present in a shared space. The trade-offs between awareness versus privacy, and awareness versus disturbing others, are central themes in computer-supported cooperative work and should be taken seriously. The willingness to share insights and best practices is a success factor to reach the benefits in knowledge management (Ives, Torrey & Gordon 2000).

As discussed earlier, the serendipitous nature of tacit knowledge activities requires collaborative technologies which to a greater extent resemble human behaviour in order to encourage socialisation of knowledge sharing, discussion and collaboration (Wenger & Snyder 2000; Davenport & Prusack 2000). Information tends to lose context as it crosses boundaries, and different groups attach different understanding and meaning to information (Junnarkar 2000; Ackerman 2000). Engaging in communities of practice can reduce the stickiness of knowledge, or as Duguid (2005: 113) puts it:

Membership in the CoP [community of practice] offers form and context as well as content to aspiring practitioners, who need to not just acquire the explicit knowledge of the community but also the identity of a community member.

21

2.3 Information Systems to Support Knowledge

Management

In this chapter, an overview of the different types of information systems used by organisations to support knowledge management will be presented.

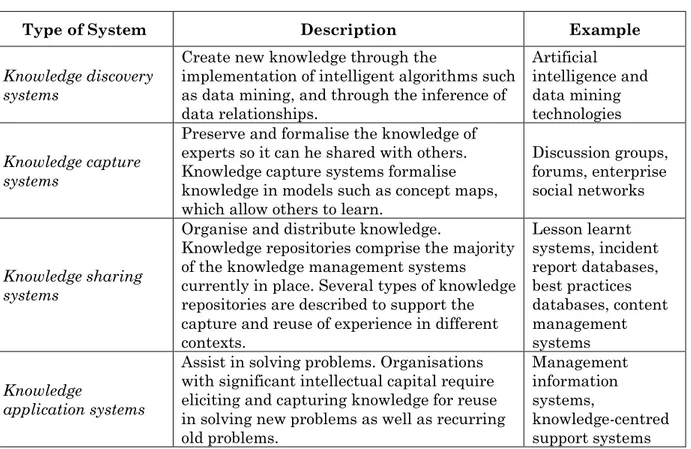

2.3.1 Overview of Knowledge Management Systems

So far we have analysed theory on how knowledge is created amongst individuals, disseminated around organisations to accumulate intellectual capital, and sustained as organisational innovations are constantly reinvented in a dynamic process. By using concepts such as tacit and explicit forms of knowledge, computer-supported cooperative work and communities of practice, we have recognised a common challenge in knowledge management: How can systems be designed to reflect the way people really carry out their work in the digital workplace?

According to Cook (2008) the challenge lies in minimising the gap between the formal and the social communication within the organisation. By using a framework for classification of knowledge management systems as presented in Table 2, the following types can be categorised.

Table 2: Role of Information Systems in Knowledge Management (Becerra-Fernandez & Leidner 2008: 6)

Type of System Description Example

Knowledge discovery systems

Create new knowledge through the

implementation of intelligent algorithms such as data mining, and through the inference of data relationships. Artificial intelligence and data mining technologies Knowledge capture systems

Preserve and formalise the knowledge of experts so it can he shared with others. Knowledge capture systems formalise knowledge in models such as concept maps, which allow others to learn.

Discussion groups, forums, enterprise social networks

Knowledge sharing systems

Organise and distribute knowledge.

Knowledge repositories comprise the majority of the knowledge management systems currently in place. Several types of knowledge repositories are described to support the capture and reuse of experience in different contexts. Lesson learnt systems, incident report databases, best practices databases, content management systems Knowledge application systems

Assist in solving problems. Organisations with significant intellectual capital require eliciting and capturing knowledge for reuse in solving new problems as well as recurring old problems. Management information systems, knowledge-centred support systems

22

Limitations placed by the importance of context in the applicability of for example knowledge repositories narrows the possibilities for their impact, thereby supporting learning only at the group level (Becerra-Fernandez & Leidner 2008). As a reaction to this, systems providers are adopting ideas from community of practice theory to design social mechanisms to support the activities of the learning organisation. As discussion and interactivity are necessary elements in order to share tacit knowledge (Davenport & Prusack 2000; Alavi & Leidner 1999), such features are becoming standard in modern information systems designed to facilitate knowledge manage-ment.

As we shall see in this chapter, the social features and the identities of community members are central in e.g. emergent social software platforms (McAfee 2011). New generations of knowledge management systems use technologies to support global brainstorming and collaboration such as wikis. These technologies are providing opportunities for perspective making and social networking among users at the organisational level. The social features support the processes of combination and socialisation of knowledge, and thereby promoting the goals of knowledge management (Becerra-Fernandez & Leidner 2008; Takeuchi & Nonaka 1995).

2.3.2 Chaotic Knowledge Dialogues vs. Systemic Information

Proc-esses

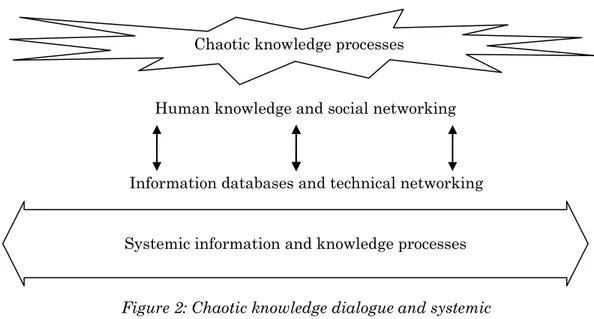

Organisations are challenged to reach a balance between the fluid but chaotic news and collaboration feeds on the one hand and the rigid, traditional and contextually poor document management systems on the other hand. As the traditional social-isation of the knowledge-creating company takes place in real life situations, systems are designed to support these knowledge processes within communities of practice in order to effectively create, diffuse and sustain knowledge.

However, organisations use both kinds of systems for different purposes, as more than one channel or platform are needed in order to accommodate diverse knowledge sharing needs and preferences that different groups have (Shan & Leidner 2003). The struggle to minimise the formal and social communication can be illustrated in Figure 2 below. Here, the fluid dialogue takes place in chaotic social processes where new knowledge is created. The created knowledge needs to be captured and stored in information systems in order to disseminate it around the organisation (Cook 2008; Ackerman 2000).

23

Figure 2: Chaotic knowledge dialogue and systemic information processes (Adapted from Skyrme 2000: 72)

The chaotic knowledge processes – the socialisation of tacit knowledge – is crucial and should happen transparently to enable internalisation of knowledge (Takeuchi & Nonaka 1995). Modern emergent social software platforms such as Yammer, Salesforce Chatter etc. resemble posting streams and social feeds like Twitter or Facebook, but are designed for internal use within organisations. These platforms offer possibilities to exchange ideas and capture knowledge from workers, and are often grass root initiatives from early adaptors within organisations as a response to the often poor knowledge management systems that are in place (Riemer et al. 2012).

As organisations grow and are divided into different departments there is often a struggle to support knowledge management across borders (Shan & Leidner 2003). Each department might individually implement information systems which differ in their design and functionality. As new needs are faced for various reasons, new systems are implemented resulting in dispersed information sources. What are the options to consider for organisations facing these kinds of challenges? To try to answer this, we will take a brief look at the concepts behind emergent social software platforms.

2.3.3 Emergent Social Software Platforms

The reason why many organisations are implementing interactive elements in their intranets is to empower the creativity and potential of their employees. By enabling users with the possibilities to generate, alter and update content, a critical difference in terms of knowledge elicitation is reached, as more and better output is created which can lead to innovation (Jacobs & Nakata 2010; Tuzhilin 2011). As users can

Chaotic knowledge processes

Human knowledge and social networking

Information databases and technical networking Systemic information and knowledge processes

24

collaborate without hierarchical or geographical impediments, knowledge can be found quicker. This reduces the risk of double work and information can flow easier across borders, which contributes to the intellectual capital of the organisation as a whole (McAfee 2006; Seeman et al. 2000).

Organisations use several technologies to enable knowledge sharing, which can be summarised into two categories; channels and platforms (McAfee 2006). E-mails and person-to-person chat are examples of channel technologies that enable digital communication to anyone, albeit with low level of commonality, contextual richness and support for serendipitous updates. The second category is platforms, which include corporate websites, intranets and other information portals. These platforms, in contrast to channels, generate content available to a larger audience and with high level of commonality, but often with centralised editorial requirements.

Traditionally, these platforms support formal and top-down communication. With technologies such as Ajax (Asynchronous JavaScript), there is a shift and decentral-isation of content provision as the users of a community can take more active roles. The platforms can be updated in a continuous and collaborative manner as Ajax enables content to be updated without having to reload the entire website, since it uses JavaScript to download and upload new data from the Web server. On the server side technologies such as PHP, Python, Perl, ASP.NET etc. are used to output data from XML-files and databases more dynamically (O’Reilly 2005).

A term to describe this is user generated content. Since user generated content is made available to others through a website or social network, it does not include e-mail which is considered a channel technology. Popularly, this is called Web 2.0 and includes participatory information sharing, inter-operability, user-centred design and collaboration on the World Wide Web (O’Reilly 2005). The technologies behind Web 2.0 enable richer experience in terms of user experience, but also functionality as applications can be spread and integrated, through feeds, Web services, RSS (really simply syndication), mash-ups etc. It is through technologies like these that social software can involve the users as integral parts of systems/platforms in a more interactive manner (O’Reilly 2005).

When adapting these technologies to the enterprise, organisations face better opportunities to enable successful knowledge management; as capabilities on both the client and the server side can syndicate content, the output and practices of knowledge workers can be made more visible to colleagues. In this way, information can be created, shared and sustained by individual users without formal hierarchies. McAfee (2011) calls these platforms for emergent social software platforms as they are not dependent on predefined workflows, roles or responsibilities among users. Instead, they emerge over time as user generated content and activity streams are dynamically updated by user activity, by other system events and by information

25

from external systems (Drakos et al. 2011). As emergent social software platforms are built on Web 2.0 technologies, they are sometimes referred to as enterprise 2.0 when adapted to the enterprise (McAfee 2006).

2.3.4 Changing Roles in Enterprise 2.0

With emergent social software platforms, organisational communities are taking shape and are populated by their users. Jackson et al. (2009) categorise the users who participate in emergent social software platforms into the following categories:

1. Creators are users who create what other users are consuming; they create content, blog entries, status updates, tags articles etc.

2. Critics are users who react on what the creators are creating by commenting on blog posts, news articles, documents etc.

3. Collectors are users who collect links, sign up for signal alerts, subscribe to RSS feeds etc.

4. Participants are users who use emergent social software platforms to build professional networks, find competencies etc.

5. Spectators are users to consume information, read blogs, articles, discussion forums, social feeds etc. but do not contribute or share themselves. This tends to be the largest group of users in such networks (Lundgren et al. 2012).

Even though the majority of the users in emergent social software platforms tend to be spectators – which again reminds us of the trade-offs in sharing knowledge as discussed in chapter 2.2.3 – these platforms facilitate knowledge sharing and collaboration which can be beneficial for the entire organisation (McAfee 2011). Through blogs, wikis and communities these platforms connect knowledge seekers with knowledge providers through social networking, and their dialogue can be viewed and searched by others who can learn from the process. Bin Husin & Swatman (2010) refer to the different roles within enterprise 2.0 as creators, synthesisers and consumers and illustrate their relationships in the model presented in Figure 3.

26

Figure 3: Creators, synthesisers and consumers of knowledge in enterprise 2.0 (Adapted from Bin Husin & Swatman 2010: 279)

The creators are often a minority that contribute the majority of content, which is consequently synthesised and disseminated by a larger group around the organis-ation to be consumed by its entire populorganis-ation (the creators are also consuming information and knowledge).

The user involvement as described above can be a reason why some organisations fail to implement emergent social software platforms, which is closely linked to user resistance. If users do not see the purpose in engaging in the various information systems that are put in place, they will resist in actively participating. As social software is dependent on user generated content it is crucial that employees are educated thoroughly so that the benefits are made evident (Lundgren et al. 2012). A risk with having a small percentage of creators is that the real experts with the most knowledge might not take active roles in sharing the knowledge sought after within the communities. They might be busy engaging with customers or working on other assignments, while others post in the communities (Lundgren et al. 2012).

2.4 Summary of Theoretical Framework

To summarise the theoretical discussion, the key points are presented in short. Knowledge managements is defined as

…the deliberate design of processes, tools structures etc., with the intent to increase, renew, share, or improve the use of knowledge represented in any of the three elements of intellectual capital. (Seeman’s et al. 2000: 89)

1 % Creators 10 % Synthesisers 100 % Consumers

27

Knowledge creation involves iterative conversions from tacit to explicit in four different modes – socialisation, externalisation, combination and internalisation – and Nonaka and Tageuki (1995) emphasise that the social dimension is key for the whole knowledge creation process. The social capital describes the way people work together, build networks and webs of trust, negotiate meaning around artefacts and is hence an important aspect of knowledge creating activities (Seeman et al. 2000). As knowledge has important tacit components (Tsoukas 2003), its understanding and interpreting resides on individual skills, understanding, collaborative social arrangements, but also in the tools, systems and processes that embody knowledge (Wenger & Snyder 2000). Computer-supported cooperative work facilitates key challenges in knowledge management, such as re-contextualisation of information (Ackerman 2000). It may increase the quality of the knowledge creation when conducted in communities of practice, by enabling a digital forum for constructing and sharing beliefs, confirming consensual interpretation, and for expressing new ideas (Alavi & Leidner 1999).

As the externalisation of tacit knowledge and internalisation of explicit knowledge is made visible, this enables learning from others and more efficient problem-solving as groups do not have to reinvent the wheel when facing situations others have faced before (Ackerman 2000). From this perspective, communities of practice support the capacity to collaborate and thus contribute to the intellectual capital through (Seeman et al. 2000).

Limitations placed by the importance of context in the applicability of for example knowledge repositories narrows the possibilities for their impact, thereby supporting learning only at the group level (Becerra-Fernandez & Leidner 2008). Communities of practice reduce stickiness of knowledge, as knowledge sharing is facilitated amongst its members as people share context, practice and can communicate and collaborate to reach mutual understanding (Wenger & Snyder 2000).

Emergent social software platforms include technologies to support global brainstorming and collaboration such as wikis (McAfee 2011). These technologies are providing opportunities for perspective making and social networking at the organis-ational level by supporting processes of combination and socialisation of knowledge, and thereby promoting the goals of knowledge management (Becerra-Fernandez & Leidner 2008; Takeuchi & Nonaka 1995).

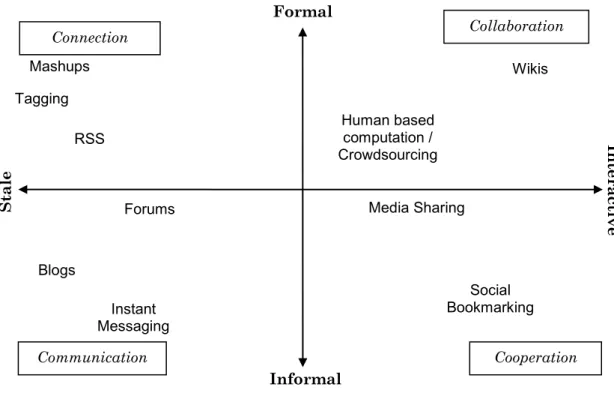

To get an overview of the Web 2.0 technologies used to enable emergent knowledge sharing within organisations, Bin Husin & Swatman’s (2010) four-category model is illustrated in Figure 4 (see next page). It gives a broad overview of how the needs of communication, cooperation, collaboration and connection are met through different technologies, all with different degrees of formality and social interaction.

28

Enterprises can make use of the relevant Web 2.0 technologies in a number of different ways to suit the needs and culture of their organisation. Very informal and collaborative cultures are described to use technologies on the Connection and Communication side. More formal but highly collaborative cultures are said to use technologies in Collaboration corner of the graph. Informal and formal cultures, with focus on individual effort but with group problem solving are describes to use software in the Cooperation part (Bin Husin & Swatman 2010).

Figure 4: Four Category Model of Emergent Social Software Platforms (Adapted from Bin Husin & Swatman 2010: 277)

Blogs Instant Messaging Tagging RSS Connection Collaboration Communication Cooperation Mashups Media Sharing Social Bookmarking Forums Human based computation / Crowdsourcing Wikis Formal In te rac tiv e Informal S tal e

29

3. Methodology and Research Design

The research methods describe how the research questions are approached in order to reach answers using scientific practices. Informatics is an interdisciplinary academic area as it encompasses the interplay between organisations, information systems and people. Researching these rather complex relationships, involving technology as well as social science, requires well developed methods. In this chapter, the choices of methods for collecting and analysing data are explained.

3.1 Case Study as Research Strategy

The principal objective of adopting a case study is to achieve deep understanding of processes and other concept variables, such as participant’s thinking processes, intentions and contextual influences (Woodside 2010). According to Yin (1994), case studies can be approached in three different ways: exploratory, descriptive and explanatory. As the purpose of this thesis involves organisational and individual behaviour in relation to the use of information systems, it aims to answer both how and what questions. Therefore this case study has both descriptive and exploratory approaches, and qualitative data needs to be collected for a subsequent analysis. We aim to provide empirical insights to a specific problem area within knowledge management by looking at a specific organisation, QlikTech. For this purpose, a case study research strategy is suitable as it investigates a phenomenon within its real life context (Yin 1994: 13). As the boundaries between the specific phenomenon and its context are not clearly evident, in-depth describing and understanding are required in order to answer the research questions. According to Yin (1994), if the research questions aim to answer how and what, case studies are suitable as they provide deep and rich approaches to analyse particular problems.

3.2 Qualitative Data Collection

In order to reach deep understanding of the research case, multiple qualitative research methods are involved. Case studies involving qualitative methods can be contrasted to surveys, which focus on more quantitative data that can be expressed in statistical numbers (Bryman & Bell 2005). The two different research strategies – qualitative vs. quantitative – are used for different purposes where one is better studied than the other to show different relationships, phenomena, contexts etc. Surveys can provide more general insights as large populations can be studied, and case study research can provide more detailed, deep and accurate understanding (Woodside 2010). Qualitative approaches can provide richer and more detailed

30

information and data (Bryman & Bell 2005), albeit with less guarantee of correctness and generality.

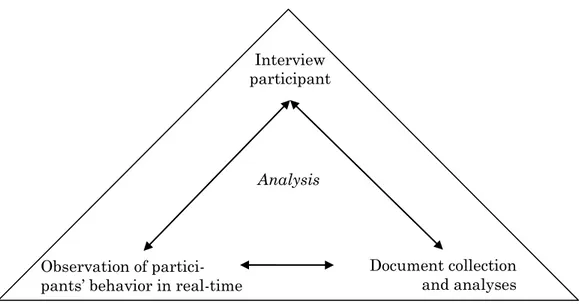

3.2.1 Qualitative Triangulation Approach

For the purpose of this thesis, a qualitative triangulation approach is taken, as illustrated in Figure 5 (Woodside 2010). Our triangular approach involves direct observation, semi-structured qualitative interviews and analysis of written documents. Woodside (2010) argues that mixed methods in case studies contribute to increased accuracy and complexity, rather than increased generality.

As the main objective is to understand user perspectives on knowledge sharing, collaboration etc. within the organisation, in-depth interviews with follow-up questions are necessary to understand participants’ highly subjective reasoning, opinions and thoughts. Combined with on-the-job observations, user behaviour and experiences are analysed in real time and within their local context by asking the interviewees to explain why certain actions are taken, and the meaning of those actions. Analyses of written documents e.g., project briefs and other secondary data, are included mostly in order to verify organisational information that are gathered from the interview.

Figure 5: Triangulation in case study research (adapted from Woodside 2010: 35)

By taking the triangulation of methods approach, Woodside (2010) argues that deeper understanding can be confirmed, as individuals by themselves are limited in their ability to report the details necessary to understand the process being studied. Case studies are sometimes criticised to be too unique and that they only represent their particular context and can therefore not be generalised. However, the purpose

Interview participant

Observation of partici-pants’ behavior in real-time

Document collection and analyses

31

of case studies is not to generalise findings to larger populations, but to probe theory (Yin 1994). In our case, the empirical findings aim to probe the theoretical gap of how unstructured and structured knowledge processes are managed by taking an interpretive approach.

Interpretive research takes the notion that we are all biased in various ways into account, by our own background, knowledge and prejudices to see things in partic-ular ways and not others (Walsham 2006). This means that when the researcher interprets the collected data based on preconceived ideas, theories and perspectives, it will have an effect of the outcome of the analysis of that data.

3.2.2 Semi-structured Qualitative Interviews

In order to gather primary data from the users of the systems, seven interviews are arranged with employees of the company (see Table 4 on next page). Personal interviews give the best opportunities to both observe and ask questions in order to find answers to complex problems in real life contexts (Bryman & Bell 2005). In order to obtain valid and representative input from the interviewees, the choice of users are scattered geographically and across different departments. As the organ-isation is global, some interviews are conducted using IP telephony and remote desktop sharing software. This is necessary, as some questions are formulated as cases, and the interviewees are asked to show how they navigate the systems in order to find specific information or knowledge.

The interviews are semi-structured, meaning that the questions are predefined, however conducted as conversation with the possibility to ask follow-up questions when necessary (Bryman & Bell 2005). In this way, the interviews are prepared to cover the intended scope of the research but still not limited to a predetermined direction. By designing interviews with a semi-structured approach, Bryman & Bell (2005) argue that exploratory questions can be asked requiring extensive explan-ations and descriptions from the interviewees, hence achieving richer and deeper answers.

32

Table 4: Overview of semi-structured qualitative interviews

Interviewee Role Method

Zaida Systems Manager, Knowledge, Lund, Sweden Personal interview Lisa Director, Internal Communications, Radnor, US Personal interview

Vanja Partner Sales Administrator, Gothenburg, Sweden IP telephony + remote desktop sharing software Jeff Presales Consultant, Atlanta, US IP telephony + remote desktop sharing software Finn Presales Consultant, Sydney, Australia IP telephony + remote desktop sharing software Johan Project Manager R&D, Lund, Sweden Personal interview

Hampus Support Coordinator, Lund, Sweden Personal interview

Irena Financial Accountant, Radnor, US IP telephony + remote desktop sharing software

3.2.3 Observation of Behaviour

As part of the research included observation of how the information systems are used in terms of navigation, searching for information and general approaches, the interviews are set up so that the users can share their desktop with the interviewer. For the interviews conducted on site at the Lund office this was no problem, as they simply show their monitor to the interviewer.

For the interviews that are conducted using IP telephony (see Figure 4), the interviewees share their desktop using the built in desktop sharing feature in Skype. This enables the interviewer to observe how the users approach three cases that are presented to them, with the purpose to show the level of usability of the intranet “Q” deployed at QlikTech. The three cases have been formulated by Zaida, who is the System Manager for Knowledge, and the stakeholder at QlikTech. The cases are listed below.

Case 1: Finding information about holidays in your local region. Case 2: Find who is the Business owner of the Q 2.0 project.

Case 3: Find the document “Partner Marketing Toolbox - Asset Catalog (Updated 4.24.12)”

33

As the users go about to find information, notes were taken as the interviewer observe their approach, comments and steps taken. The results are presented in section 4.3.2.

3.2.4 Document Collection and Analysis

A few documents are collected and analysed as part of the triangular case study approach (Woodside 2010). The documents are mostly used as reference data to make sure that the correct information is understood during the qualitative inter-views, as this is our primary data collection method.

3.3 Approach to Analyse Data

During the semi-structured qualitative interviews, notes are taken in order to capture certain feeling and ideas that come up during the conversations. They are also recorded using a voice recording application, and fully transcribed in digital documents. Central themes are then identified in the collected data that give insights related to each other and to the research questions. Although the coding of the data is made exactly as recorded from the recordings, learning from that data is partly a subjective process as the researcher chooses to focus on certain themes and concepts (Walsham 2006).

As the interviews are semi-structured, and some more in the direction of being unstructured, many of them take unexpected turns as follow-up questions are asked as interesting tracks are taken. This has an effect on the direction of the interviews, and hence on our results. Further, the questions are affected by the chosen theory.