PRESENTS

A STUDY ABOUT STEERING THE DANISH MOVIE

INDUSTRY TOWARDS A DIGITAL

TRANSFORMATION

By

Joy Hesselholdt Nielsen

Malmö University

Media Technology: Strategic Media Development (ME620A) Master Thesis, 15 credits, Advanced Level

Supervisor: Sven Packmohr Examiner: Bahtijar Vogel June 6, 2018

i

Abstract

Online movie distribution has become a common practice after giants such as HBO and Netflix have entered the scene. Despite the new digital technologies, the Danish movie industry are having a hard time benefitting from these. While watching the Danish movie ticket sales decrease, the film industry can observe the increasing number of people staying at home watching Netflix. Therefore, it is essential that the movie industry start looking at their business- and distribution models in order to find out where they can optimize their businesses. By using a qualitative inductive approach, this study explored how the Danish movie industry’s traditional business- and distribution models can be adjusted; in order to meet customer demands and be able to compete with its digital competitors. Focus groups with movie customers as well as interviews with industry experts were conducted. The main results were that the participants preferred watching Danish content at home, because of the lack of special effects; because of the cinema ticket prices; as well as the many different options they have at home. Furthermore, it was found that the film industry has difficulties creating content that is embracing new technologies such as 3D; that they are still focusing on the mass when producing movies; and they are not able to get first-hand data from customers. Based upon these results, new business models and distribution models were created. These implement concepts of how the Danish movie industry can meet the requirements of the audience and be able to compete with its digital competitors. The business models include a varies of factors such as Virtual Reality, 3D, data-driven marketing, audience co-creation, new niche subsidy possibility, crowdfunding, more film club memberships and QR codes. The new flexible distribution model makes it possible for a movie to move into the Video-on-Demand window as soon as the movie stops selling in the cinema. These models propose that by implementing these concepts in their business models, the film industry can attract more customers to Danish movies as well as move toward a digital transformation, letting them benefit from the new technologies and be able to compete with its digital competitors. Thereby this study contributes with the first steps for the Danish movie industry to go through a digital transformation.

Keywords

ii

Forewords

I want to give a special thanks to the four professionals Kim, Jesper, Merete and Mette, who by letting me interview them provided me with unique knowledge about their fields, which was an important part of this study, and I could not have done this without their help. Furthermore, I want to show all my focus group participants my gratitude, as they gave me some insights of their thoughts about Danish movies as well as their cinema habits.

Additionally, I want to thank both Teddy and Joa for giving me feedback on the business models and discussing some ideas with me. That has helped a lot. I also want to thank my supervisor, Sven, who has been a big support in the thesis writing, as I was able to discuss different perspectives with him about the report, and who also guided me in the direction of the digital transformation topic.

At last, I want to thank my thesis companion and good friend, Despina, who has supported me throughout this writing process, and lifted me up when I was down and questioned the whole project.

iii

Table of Contents

1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Research aim ... 2

1.2 Delimitations ... 3

1.3 Outline of the report ... 3

2 Background ... 4

2.1 Digital transformation ... 4

2.2 The Danish movie industry ... 9

2.3 Lesson Learned ... 16

3 Research Methodology ... 18

3.1 Qualitative Research ... 18

3.2 Focus Groups ... 19

3.3 Interviews ... 20

3.4 Data analysis ... 21

3.5 Artefact ... 22

3.6 Ethics ... 23

3.7 Reliability, validity & transferability ... 24

4 Results ... 25

4.1 Focus Groups ... 25

4.2 Interviews ... 34

4.3 Final Artefact ... 44

5 Discussion ... 51

5.1 Danish Movie Distribution Model ... 51

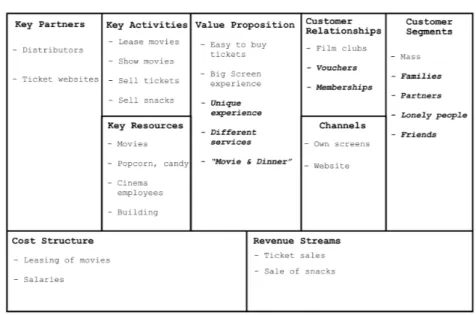

5.2 Danish Cinema Business Model Canvas ... 54

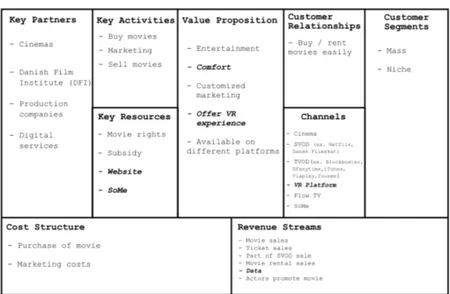

5.3 Studio Business Model Canvas ... 56

5.4 Distributor Business Model Canvas ... 59

5.5 Digital Transformation ... 60

6 Conclusion ... 62

6.1 Suggestions for further studies ... 63

6.2 Alternative Publication ... 63

iv

Table of Figures

Figure 1 - Overview of the report ... 3

Figure 2 - Traditional Distribution Model (DK) ... 11

Figure 3 - Focus Group Participants ... 20

Figure 4 - Word Cloud showing main themes at the focus groups (Nvivo) ... 25

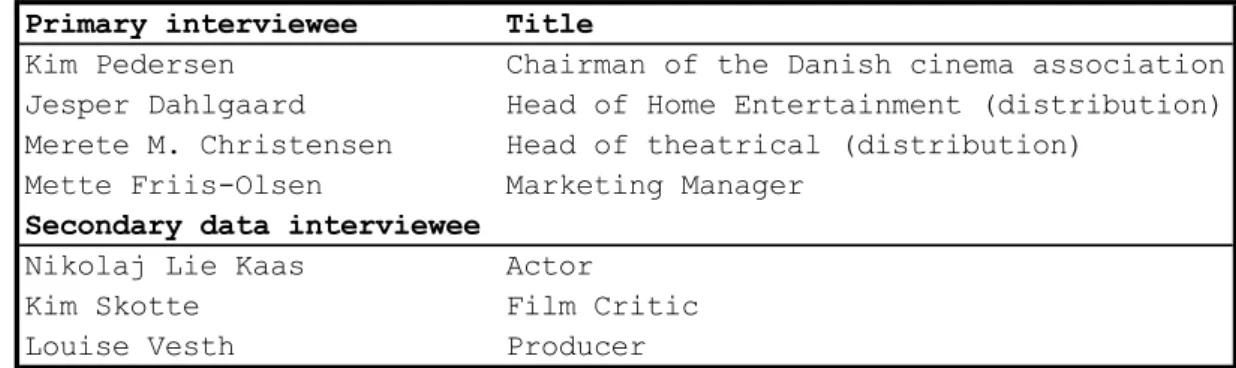

Figure 5 - Interview participants ... 34

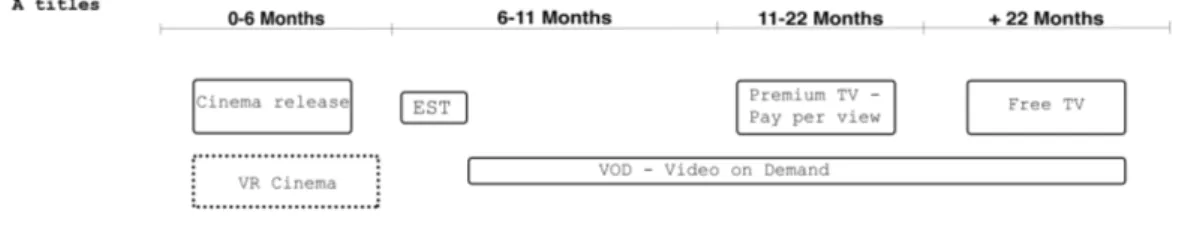

Figure 6 - New distribution model (A titles) ... 45

Figure 7 - New distribution model (B titles) ... 46

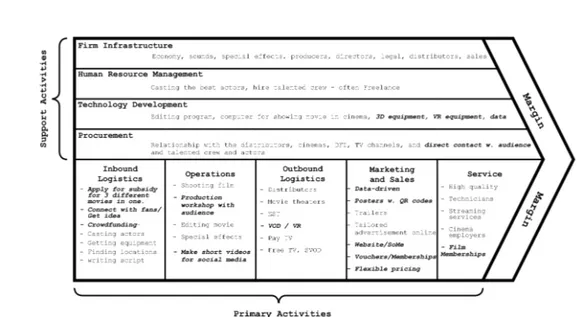

Figure 8 - New value chain ... 46

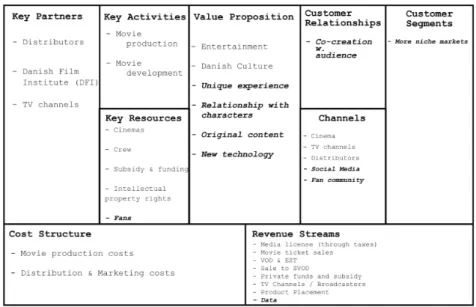

Figure 9 - Final BMC for Production company ... 48

Figure 10 - Final BMC for Cinema ... 49

v

List of Abbreviations

B2C Business-to-Consumer

BMC Business Model Canvas

DFI Danish Film Institute

EST Electronic Sell-Through

HE Home Entertainment

QR Quick Response code

SVOD Subscription-Video-on-Demand

TVOD Transactional-Video-on-Demand

VOD Video-on-Demand

1

1

Introduction

Over the past decades, there has been a significant change in the media landscape, which is very much due to digitalization. The word digitalization is defined by the shift from analog to digital production, transmission, storage, and consumption. (Fagerjord & Storsul, 2007, p. 26) As an effect of this traditional mediums like newspapers, books, music, and TV are now moving over to digital platforms instead of only having the old analog format (Bondebjerg, 2014; Yu et al., 2017).

The distribution of music and movies online is also becoming more common, because of the rapid spread of internet access (Bolin, 2007, p. 240; Gu et al., 2017) Twenty-nine percent of the Danish population visit the online streaming giant YouTube, and seven percent visit Netflix on a daily basis (Slots- & Kulturstyrelsen, 2017b). Furthermore, in 2017, thirty-seven percent of the Danish population used Netflix at least once a week, which is an increase from 32 percent in 2016 (DR Medieforskning, 2017). One of the reasons for the rise in online services is that people find it more convenient to have a library available online, with a lot of content, instead of having to buy individual physical DVDs one at a time which take up much room (Yu et al., 2017; McMillan et al., 2015). Furthermore, when watching a movie at home, it is usually something people do once, hence they prefer the convenience of not having to buy DVDs and having a physical collection of movies (Kalker et al., 2012). Another reason for the increasing demand for online video streaming services is that they offer much more flexibility than the traditional movie theater services (Gu et al., 2017). Thus, digitalization has created a culture where we can watch movies at the cinema, on our TV, on our phones, and on our computers at any time; and we are not limited to our DVD players at home (Bolin, 2007, p. 237; Yu et al., 2017; Rigby et al., 2016).

The digital trend of movie distribution is also visible in Denmark: DVD and Blu-ray sales of Danish movies have been decreasing rapidly from 22.7 percent in 2012-2013 to 11 percent in 2015-2016. Although the digital sales have seen a steady increase over the past years, the online sales of Danish movies, such as Video-on-Demand (VOD) services has not yet met the economic expectations there is for it. Subsequently, the cinema is the most prominent source of income in the Danish movie industry. (DFI, 2017) However, even though the theatrical window is still the most important for Danish movies economically, the sales in this window for Danish movies has also been decreasing since 2015; from 4,112,000 tickets sold in 2015 (Danmarks Statistik, 2018) to 2,534,857 last year in 2017 (DFI 2018). At the same time, the American movie ticket sales in Danish cinemas increased from 6,957,000 in 2015 to 7,249,000 in 2017. Nevertheless, the total

2

ticket sales have decreased from 12,994,000 tickets in 2016 to 11,927,000 in 2017. (Danmarks Statistik, 2018)

Meanwhile, there has been an increase in competition on digital platforms. In 2007 Netflix started the wave, then in 2011 Viaplay came and HBO joined in 2012. YouTube Red and Snapchat Discover (all new online TV-channels) came around in 2015, and Amazon Prime Video in 2016. In 2017, YouTube TV also showed up and started competing with established cable services. (Slots- and Kulturstyrelsen, 2017b) UltraViolet is yet another service Hollywood has made as an attempt to prevent illegal downloads of movies and is a service platform that has a family-oriented online digital movie library (Kalker et al., 2012). Hence, the sale statistics together with the increase in competition put considerable pressure on the Danish studios and the film industry, as its traditional business models, its revenues and its distribution models are challenged.

In order not to face destruction at the hands of their competitors that are succeeding in creating transformation through technology (Fitzgerald et al., 2013), the Danish movie industry also needs to take some steps toward digital transformation to survive on the market. Competitors such as Netflix and HBO have also previously faced challenges with their traditional business models because of digitalization. However, they adjusted their business models in order to create digital transformation and are now even more successful than they were before: Netflix going from 20 million subscribers in 2010 (Netflix, 2010) to over 110 million subscribers worldwide by the end of 2017 (Netflix, 2018). As well as HBO going from 81 million subscribers in 2010 (Time Warner, 2010) to over 140 million subscribers worldwide (Time Warner, 2018). Thus, HBO and Netflix are not only competitors to the traditional Danish movie industry, but they are also a picture of how an adjustment of business models and digital transformation can be beneficial for traditional media companies. Therefore, this study will explore ways in which the Danish film industry can create digitally transformed business models.

1.1 Research aim

The aim of this report is to investigate how the Danish movie industry can adjust its traditional business- and distribution models, in order to attract more people to watch- and pay for Danish movies, compete with competitors, as well as to make the industry benefit, instead of detriment from the technological advances. The objective of this thesis is to come up new business- and distribution models showing how the Danish movie industry can be led toward a digital transformation.

3

1.1.1 Research Question

In order to reach the aim and objective of this report, the research question for this project is:

How can the Danish movie industry adjust their current business- and distribution models, in order to meet customer demands and compete with its digital competitors?

This research question will be answered by conducting qualitative data in the form of focus groups with movie audience and individual interviews as well as secondary data with movie industry professionals. This information will then lead to a creation of new business- and distribution models, which show where adjustments can be made.

1.2

Delimitations

This report will have its emphasis on Danish movies, and not Danish TV shows. The reason for this is that these two are different in both distribution and production, hence the results would differ from one another. At last, as there are many different definitions of business models, this report will follow the Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010) as well as Porter’s Value Chain (Porter, 1985) as a tool for creating the business model artefacts.

1.3

Outline of the report

The structure of the report is as follows: The first section is the background, where information and previous research about digital transformation, the Danish movie industry, and the cinema business are addressed. This section is followed by the research methodology chapter, where the different choices and procedure of the research will be outlined and explained. Third is the results section, where the findings from focus groups, interviews, the artefact and its evaluation will be outlined. That leads to the fourth section, discussion, where the findings will be compared to the background and discussed. Lastly, the conclusion section provides answers to the research question, concluding comments on the project and include suggestions for further studies. A more visual overview of the report is shown in figure 1 below:

4

2

Background

This chapter provides information and previous research about digital transformation, the Danish movie industry, the cinema business, and competition, to get an understanding of the topic.

2.1

Digital transformation

Digital transformation is defined by the use of new digital technologies (social media, mobile, analytics or embedded devices) to enable major business improvements, which among other things can include enhancing customer experience or new business models (Fitzgerald et al., 2013). According to a study in 2015, 76 percent of the interviewed employees said that digital technologies were important for their organizations today, and 92 percent said that the technology will be important three years from now (Kane et al., 2015). However, despite this acknowledgment, many companies around the world struggle to get clear benefits from the new digital technologies (Fitzgerald et al., 2013).

Because of the new technologies, digitalization makes it possible to deliver and design new business models. Therefore, companies also continuously need to explore the best way for them to generate revenue, structure activities and place themselves in new or existing industries. (Berman, 2012) Digitalization has moved physical objects to files and then from digital files to cloud served experiences. The concepts of digital media still draw on traditional models of interaction back when the media had a physical presence. The insistent use of these traditional concepts is beneficial in the way that end users easily understand them, but it does also imply a failure to exploit new possibilities the digital media comes with. (McMillan et al., 2015) The internet creates an opportunity to get broader exposure, decrease costs and the ability to target a little group of people in the demographic (Ulin, 2010, p. 3). A new cost-effective tool that can help bring offline media into the online space, is the use of scannable Quick Response (QR) barcodes (Cooper, 2011). QR codes have several advantages: Better connectivity with consumers, traceability and tracking options, an opportunity for product evaluation, and curiosity creation (Larkin, 2010).

In order to succeed in digital transformation, companies need to redefine their customer values and operating models at the same time. Those companies that are able to implement new business models based on customer demands can win first choice of talents, partners and resources. (Berman, 2012) Fitzgerald et al. (2013) states that even though companies may be afraid of doing

5

the wrong thing, the only wrong move they can do is to not make any move at all. The ability to go through a digital transformation is not only about the technology, but mostly about having a clear digital strategy. It is simply a matter of fact how the companies integrate these new technologies to transform their businesses. (Kane et al., 2015) This is supported by Matt et al. (2015) who believe digital transformation has four different elements: “Use of technologies”, “changes in value creation”, “structural changes” and “financial aspects”. The use of technologies is about the company’s attitude towards the new technologies and their ability to use them. The use of new technologies then often leads to changes in the value creation because the new digital activities may be very different from the classical business. This is supported by Ulin (2010, p. 308-309) who says that digital services add to the value proposition, because one key element is that customers are able to access their video on whatever screen they want, and at any time they want. The changes in value creation leads to structural changes because it is needed to have a solid base for the new operations, when using different technologies and new forms of value creations. These three elements can only be transformed after thinking about the fourth, financial aspects. Because, it is essential that the company can pay for the transformation. (Matt et al., 2015) In creative industries when going through a digital transformation, the value propositions are changed, which includes the product offering, the target customer segment and the revenue model (Li, 2017).

An example of a company who has gained digital transformation in their business model is Paramount Pictures, who have experimented with other more digital distribution methods. Instead of the traditional physical movie theatres, they made a 3D version of the Top Gun movie available on bigscreenvr.com, where everyone with a Virtual Reality (VR) headset could watch the movie for free in a virtual cinema. The movie started every 30 minutes for 24 hours. (Busch, 2017) In that way, people were able to get a movie theatre experience at home, as the movie showed on a virtual big screen. Furthermore, with the app BigScreen, it is also possible to invite friends who also have the app to sit next to you in the theatre. (Hunt & Karner, 2017)

2.1.1 Digital content

Just like Paramount Pictures, other entertainment companies have to recognize the need for a digital transformation, as digitalization has changed the way to reach an audience: It is no longer the sender who is in charge of deciding what everyone should watch and at what time (Bondebjerg, 2014). In the old days there were a limited number of TV networks, therefore they could reach a massive audience (Satell, 2015). Today, streaming services like Netflix, make it

6

possible for people to consume a much wider diversity of media, because of the big exposure (McMillan et al., 2015).

Research shows that movie viewers are more attracted to newly produced movies on streaming services, even though the movie ratings may not be high yet, because the movie is that new. Thereby the release date of the movies is found to have a significant influence on the movies view count on the leading streaming service Youku in China. (Gu et al., 2017) In 2016, Danish households paid an approximate annual price of 275 DKK for streaming services (Slots- & Kulturstyrelsen, 2017). Furthermore, Danish people in the ages between 15-29 use around 97 minutes a day on streaming movies or TV shows. Over the age of 30, the number is 31 minutes. Additionally, in 2017, Danish people used the internet on their mobile phones more than they did on their computer with nearly 70 percent vs. 60 percent. (DR Medieforskning, 2017) Research show that tiny screens reduce the viewing experience, but after a certain size there is no real difference: In the study there was no real difference between watching a movie on a 13-inch laptop compared to a 30-inch monitor screen. (Rigby et al., 2016) Other mediums that are getting more and more hold in the Danish population is the social media site Facebook, which 65 percent use on a daily basis, and Snapchat which 23 percent use on a daily basis (DR Medieforskning, 2017).

2.1.2 New business models

Young people today are “Digital Natives”, as they have grown up with the internet and the ability to use digital media, and this has challenged the top and down business models, as the consumers now need to be part of the process to a bigger extent (Andersen et al., 2015, p. 37). Smith and Telang (2016, p. 115) agree with this by saying that the old top-down model is changing to a more downstream one, as distribution platforms have a mass of content, learn customers’ preferences and recommend content directly to the consumer. When using the old traditional business models, the studios are not able to exploit that opportunity. Instead, this opportunity is given to the emerging online distributors like Netflix and Amazon. (Smith & Telang, 2016, p. 115) The question about having a movie available online is not about whether this can happen, but more about what the appropriate window is for it (Ulin, 2010, p. 35). Thomas Mai, a Danish movie salesman and speaker, suggests thinking about the internet already in the pre-production phase of a movie, by having movies shown both at cinemas, on Video-on-Demand (VOD) services and DVD at the same time, as this will target everyone simultaneously. He believes that when the audience has to wait around six months before the movie is available on other platforms than the cinema, then people are more willing to find it illegally online. By continuing this way, he

7

believes the movie industry is “punishing the audience, and not rewarding them”. (Monggaard, 2011) This is supported by Duelund (1995) saying “if you can’t beat them, join them” (p. 413) about online competition. However, Ulin (2010, p. 5) does not agree, because he believes online distribution does not provide content value, as the distribution is non-exclusive, flat-priced and simultaneous. He believes online distribution only provides value based on the time factor. Another example of a company that has gained digital transformation is Netflix, who by changing its business model grew from 7 million subscribers in the US to 93 million worldwide (Lotz, 2017). Netflix adapted to digitalization and changed its business models because of it: In 1997 Netflix started offering a DVD mailing service, which became successful with 14 million customers in 2010. But in 2010, DVDs were on their way out, and Netflix therefore embraced the technological development and created an online streaming service, which cannibalized on its own DVD service. (Smith & Telang, 2016, p. 137) Now they are even producing their own shows (Lotz, 2017). Netflix uses a Subscription-Video-on-Demand (SVOD) model, which allows subscribers to access as many movies as possible at any time, and for the same price each month (Ulin, 2010, p. 374). The traditional cable channel HBO has also managed to compete in the new era, due to a shift in their business model. First, by launching HBO Go in 2010 for people already paying for their TV channel; and then in 2015, launching HBO Now, allowing people who do not pay for their TV channel to subscribe. Because HBO uses a business to customers (B2C) model, they get all their money from the subscriptions, and do not have to share with TV distributors, like it would otherwise. HBO has simply adapted to the digital era and transformed their business model accordingly, in order to continue to create value in the fast-changing media landscape. (Nathalie, 2017)

2.1.3 Data-driven business models

According to Smith and Telang (2016, p. 155) the entertainment industry will need to embrace data-driven decision making and make use of detailed customer data, if they want to succeed in operating in the changing digital media landscape. When distributing a movie through the cinema, it needs to be promoted in order for customers to hear about it. However, when distributing the movies through services like Netflix, it has algorithms and properties to promote itself. (Crewe, 2017) In order to open a movie in the cinema, a lot of marketing is needed to be done in order to create awareness of the movie. The media costs for this are quite high, and if the movie does not perform well in the theatre, it is just too late. (Ulin, 2010, p. 399) That is why some studios in Hollywood have started to use data-driven business models in order to make sure they only use advertising money on the actual target group. For example, the director Eli Roth used

8

demographic data to create the most cost-efficient marketing campaigns for his movie “The Green Inferno”. They simply tracked who watched the movie clips, how long they were watching it and who shared, liked or commented on it, which provided them with the data showing that teenage girls were the target group. (JP, 2015) Another way of using data in the film industry is to predict a movie’s market revenue. A study by Shim and Pourhomayoun (2017) showed that they were able to determine the success of a movie by predicting the movie’s opening weekend revenue, only by using data from Twitter. Netflix started in 2013 to develop its own shows, which they created based on an analysis of its customers’ data. Netflix kept track of rankings, popularity and interests of their customers, and invested in original content productions based on that. (Radak, 2016) When producing the series House of Cards, Netflix had analyzed 33 million subscribers’ viewing patterns and preferences, which gave them the basic confidence that the show would be popular, and it was (Smith & Telang, 2016, p. 136).

Studios know about the possibility to use data, but they do not want to make decisions based on the data and they do not know what to do with it. Nevertheless, the market reports that studios use are not the same as the data Netflix for instance get, as Netflix get data straight from the customers, and thereby gives a better picture of the audience. (Smith & Telang, 2016, p. 138, 150) Most studios do not have direct contact with the customers, because they use distributors, which makes it hard to get the necessary data. And companies like Netflix does not give any data to the studios, only quarterly reports on how many views the movies have had. (Smith & Telang, 2016, p. 140, 144, 178; Masters, 2016) However, creating their own streaming channel is not always the solution for studios because customers prefer convenience and simplicity, and if they cannot find all their digital content at one place, they will use one of the bigger ones instead. (Smith & Telang, 2016, p. 129, 151)

2.1.4 The Long Tail

Years ago, everything was about the big hits. One popular show on TV attracted a big audience, and that was the way of doing business. However, today it is not so much like that anymore, and the hits are not the economic force they once were. The internet is able to bring millions of shows to one person, and thereby customers are simply scattered into many niches online. (Anderson, 2006, p. 2, 5) The Long Tail is about focusing on having a big variety of products, each selling in small volumes, whereas in the old days the market focused on a small range of products which all sold in big volumes (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010, p. 68-69). Having a big selection of products online, the storage and delivery does not cost much today, thus selling many of these niche products can add up to what one big hit would be able to (Anderson, 2006, p. 8). The

9

streaming services have allowed the Long Tail to take entry, as it makes many niche genres available to customers. Each person therefore has an easier time to find content that fits their own belief or opinion, compared to only the mainstream content being showed at cinemas. (Sweetenham, 2017) The search engine Google also supports the idea of the Long Tail, as it does not rank its results based on time, but on the most relevant, why some old movies or products can show up on this search engine, and make people discover them (Anderson, 2006, p. 143). The entertainment industry is a “want” market, because for the right price people will buy the product, and be encouraged to try something new (Anderson, 2006, p. 139). Having a subscription service can support the Long Tail, as people can browse around and watch many different movies, “for free” - without it costing the customer anything (Anderson, 2006, p. 138; Smith & Telang, 2016, p. 44). Research also supports the idea of the Long Tail on digital platforms like YouTube: Sikdar et al. (2016) found that more than 10 percent of the 350,000 YouTube videos they analyzed, peaked in popularity after at least one year from being uploaded, which means that the biggest number of viewers did not occur when the videos were just uploaded.

2.2

The Danish movie industry

The Danish Film Institute (DFI) was established in 1972 (Wümpelmann, 2008, p. 16), and is a part of the Danish culture ministry, which was created back in 1961 (Duelund, 1995, p. 207). DFI was established because the politicians realized that the market for Danish movies was not big enough to create differentiated Danish movies. It is usually DFI who finance the majority of the Danish films, but besides DFI there are also private funds, TV stations, distributors and international investors who can help. (Wümpelmann, 2008, p. 16, 22) DFI supports the development of movie scripts and movie production economically, as well as movie import, distribution and exhibition of art film, and help create awareness of the Danish movies internationally (Duelund, 1995, p. 45). Basically, public subsidies are an integrated part of the movie industry in Denmark, and therefore DFI plays a big role in the production of Danish movies (Wümpelmann, 2008, p. 69-70). Public subsidiaries account for approximately 60 percent of the financing source of Danish films (DFI, 2017). However, the public subsidies in Danish movie production may face some problems: In worst case scenario the financing of the movies can create a film industry that is only able to make it due to the public film subsidies, and not by the income from the cinema and video- & TV distribution. (Duelund, 1995, p. 206) Additionally, producers are selling their movie rights, in order to finance the movie production, which means they are now doing business based on the film production rather than the products out on the market (DFI, 2017). Because the studios’ incomes are dependent on the film subsidies rather than the movies’

10

success, they often focus on the movies that they expect will get a subsidy, rather than to apply with more original content. This leads to the creation of movies very similar to each other. Since 1972, when DFI was established, only a total of seven movies have paid back all its given subsidy to DFI. The reason for the missing back payment is because the movies do not have a big enough income to pay back the money. (Wümpelmann, 2008, p. 60) Only around 68 out of a total of 211 Danish movies have made break-even economically1 (DFI, 2017).

Danish movies usually take about two years to make and go through different phases: Pre-production, Pre-production, post-production and distribution & exhibition. The majority of the financing for the movie is needed to be found in the pre-production phase of the movie, in order for the script to be finished. (Wümpelmann, 2008, p. 21-22) A problem with financing the movie that early on in the phase is that it is almost impossible to have all the adequate information to make that decision (Ulin, 2010, p. 81). In 1989, a new film law was introduced, in order to support the cinemas, and a new type of subsidy was created, which was given to movies that were believed to have a broad audience appeal and thereby were able to attract many cinema-goers. Also, in order to attract more private capital to the movie production. (Duelund, 1995, p. 211, 213) According to Bondebjerg (2014), both production and distribution will become more globalized due to digitalization, and the national distributors and content creators need to embrace this development. He states that Denmark has to produce content for different platforms and cannot sit and wait for the global actors to take over the leading role in the country. (Bondebjerg, 2014) Because of globalization, Danish-produced media content of high quality and context has never been more challenged than now (Slots- & Kulturstyrelsen, 2017b). This challenge can be understood by the fact that Danish people more often spend money on international streaming services than the Danish ones (DR Medieforskning, 2017). Additionally, Danish movies do have an obvious limitation on the market, as the politicians have decided that the majority of the Danish-produced movies shall be Danish speaking (Wümpelmann, 2008, p. 36). Every studio wants to make a movie that they know will sell. In Hollywood they have four types of these: The real world (historical settings or real-life events), books & comics, sequels and spin-offs. Furthermore, remakes have also become a successful formula. (Ulin, 2010, p. 25, 27-29) Additionally, some argue that using a popular producer or popular director for the movie has a positive effect on the movie’s success (Wümpelmann, 2008, p. 48). This argument is supported by research showing that using popular directors or actors do have a positive effect on the movie’s

1 Movies reach break-even when the net income exceeds the producer’s and possible co-producers investment in the movie.

11

performance (Bagella & Becchetti, 1999). However, others believe that “Gone are the days where there was a clear formula to follow in order to create a hit” (Satell, 2015).

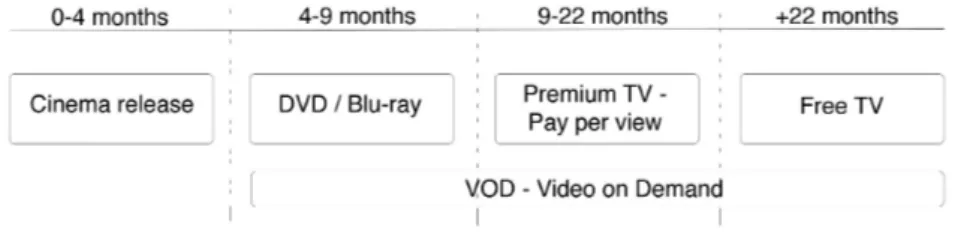

2.2.1 Traditional distribution model

Distribution means to make a product’s consumption profitable, and to make opportunities for repeated consumption of the same product (Ulin, 2010, p. 5). The distributor is the organization who decides when and where the movie shall be released (Wümpelmann, 2008, p. 24). A typical release strategy for movies is to divide the release into several “windows” (Smith and Telang, 2016, p. 40). In Denmark, the first window is the cinema where the movie is released and leased by the cinema. In 2008, the cinema paid back a lease of 44 percent of the cinema ticket sales to the distributors. Of this money the distributor gets around 20 percent and the studio gets 80 percent. After the cinema window, the movies are released on video and DVD. (Wümpelmann, 2008, p. 25) As a third window, the movie is sold to TV channels as pay-per-view, and by the fourth window it is available on free TV (Imagine, 2005. p. 22). Due to digitalization, these distribution windows have been joined by the new Video-on-Demand (VOD) window (DFI, 2017). The distribution model and its length is shown in figure 2 below (Based on model in DFI,

2017):

Figure 2 - Traditional Distribution Model (DK)

Many theatres are afraid that they will not survive if they do not have a protected window for a movie release (Ulin, 2010, p. 34), like they do now. In Denmark, the theatrical window is still the most important for Danish movies economically, as the VOD services still have not reached the expectations there were for it. Nevertheless, the Danish Film Institute believes that the online sales do have the greatest economic potential in the film industry. (DFI, 2017) And digital sales are increasing in Denmark: Digital home entertainment sales have had a solid increase in Denmark over the past years: In 2012-2013 digital sales accounted for 6.7 percent and in 2015-2016 it accounted for 12.6 percent of the sales. Whereas the physical products were decreasing from 22.7 percent in 2012-2013 to 11 percent in 2015-2016. The total income of the SVOD and Transactional-Video-on-Demand (TVOD) sales increased from 230 million DKK in 2013 to 573 million DKK in 2014. However, the slow increase in digital sales, does still not make up for the

12

decrease in sales of DVDs. For every 10 DKK that is lost from the video or DVD sales, only 1 DKK is earned on TVOD sales. (DFI, 2017) A reason for this can be that the price for a media product available online is relatively low, even if the physical product of the media is not (McMillan et al., 2015). Therefore, VOD may be the future of video, but the revenue still remains a small part of the larger markets (Ulin, 2010, p. 299).

As a reaction to the increasing sales on VOD services and the still decreasing physical DVD sales, the Danish Producer association, Producentforeningen, has come up with a solution to the problem: They suggest that VOD services should be required to pay a contribution of around 80-100 million DKK annually, which will be used for Danish content and thereby support Danish production. Around half, 40-50 million DKK, should support motion pictures and should be given to DFI to offer as a subsidy, and the other half to support TV shows. Furthermore, they suggest that a new subsidy should be available for quality content that is not limited to the flow-TV platform, but also be used to support digital productions, in order to reach kids and young adults who are using these digital platforms more. (Producentforeningen, 2018)

There is a clear reason for the Producer association to reach out for new subsidy possibilities: The economic volume for Danish movie production has decreased from 476 million DKK in 2003 to 394 million annually in 2016, an 82 million DKK decrease, which is the same as the production of approximately four motion pictures a year. The gross income has totally decreased with 16 percent from 2004 to 2016. Therefore, DFI believes that producers need to reevaluate their business models, as there has not yet been a significant change in them. (DFI, 2017) According to Bondebjerg (2014) the real problem with the Danish movie- and cinema industry is that they are not embracing the digitalization and are not willing to move forwards, regarding the digital challenge. Therefore, the traditional use of distribution windows needs to be looked at. Thomas Mai agrees as he believes the Danish movie industry is thinking too traditional in regard to financing, distribution and marketing, instead of focusing on the audience. He suggests using the audience already in the pre-production and script phase, as there may be professionals within a certain topic that could add value to a certain topic movie. (Monggaard, 2011) He states:

It is about being where the audience is. Otherwise we cannot deliver the movies they want to watch, and then they find them illegally instead. The audience has changed habits, and therefore we have to change our habits too. Otherwise we will see our own death. (Monggaard, 2011)

On the contrary, Flyverbom (Slots- & Kulturstyrelsen, 2017b) believes that one of the most important technological developments in Denmark is that the media business’ traditional linear

13

value chain has been maintained, but at the same time been able to remain in an increasing competition of the established market. Movie production companies are, however, trying to produce TV shows in order to supplement the movie production and have a more stable economy (DFI, 2017). The idea of supplementing with TV shows can be explained by the TV and radio industry’s increase in turnover of approximately 17 percent from 15.2 billion DKK in 2010 to 17.8 billion DKK in 2016 (Udvalget om Finansiering af Dansk Digital Indholdsproduktion, 2017). Movie distribution keeps relying on traditional methods of physical distribution (To et al., 2014). However, media distribution models are moving from focusing on the mass to focusing on niche markets, and from synchronous to asynchronous (Curtin et al., 2014, p. 13). In today’s market, what matters the most is the content, not the platform (Covert, 2016).

2.2.2 Movie theatres

In the ‘50s, the only place people could watch motion pictures was in the cinema, this is why people went to the cinema a lot. In the ‘60s, people would get TV in their homes, but they were still bound to the timetables of the movies or TV shows offered either by the cinema or the TV. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, as media became more global, more channels could be found and people were able to make their own films to show at home. Then in the ‘90s, the computer came around. Already in the ‘90s the so-called “zap” culture was created, because people were able to choose between different programs and channels. (Duelund, 1995, p. 407, 413) These trends can also be found in statistics: In 1953, Danish people watched 13.5 movies annually on average in the cinema (Wümpelmann, 2008, p. 74), whereas in 2016 this average was 2.3 movies annually (Nordicom, 2017). This shows that in the 1950’s the cinema was a common activity, which people attended approximately once a month. However, today, the cinema is just one of the great variety of entertainment possibilities available on the market, and people have therefore adjusted to this and go less to the cinema. (Wümpelmann, 2008, p. 75) Going to the movie theaters is much more the idea of “going to the movies” rather than the actual “movies”, because it is a social activity we have grown up with (McNamara, 2017). This agrees with Sweetenham (2017), who says that people rarely go to their local cinema to watch a movie alone. Meanwhile, many people worldwide are sitting at home and watch movies alone. At home, people can sit in their own environment and watch a movie which may not be one of the popular hits, but a niche movie. (Sweetenham, 2017) Gilchrist and Luca (2017) also argue that movies are best as a shared experience, as your decision on which movie to watch is often related to the word-of-mouth technique. If your friends talk about a certain movie, you seem to value that movie more when others have watched it.

14

In 2016, Danish films sold 2,731,000 cinema tickets, which is a big decrease from 4,112,000 in 2015 (Danmarks Statistik, 2018). Last year, in 2017, Danish movies again had a decrease in ticket sales, as it ended on 2,534,857 tickets (DFI, 2018). And this is even though there were more cinema screens in Denmark than before, since from 2006 to 2016, the number increased with 60 screens nationally (DFI, 2017). Some suggest that the decreasing sales of Danish movie tickets can be due to big established Danish directors having moved from Denmark to focus on their international careers (Reseke, 2017). However, others believe that the increasing opportunity to watch TV and video at home is the reason for the decreasing cinema visits (Duelund, 1995, p. 207). Hamid Hashemi, the CEO of iPic Entertainment, agrees by pointing out that the cinema now is competing with your home, due to all the streaming services and content available at home. Some theaters have therefore made seats with pillows, blankets and even a menu, in order to attract more movie-goers to the cinema. Other theatres are using the cinema as video game centers, as it is important for the movie theatres to reinvent themselves in order to survive and attract the younger audience. (Faughnder, 2017) This is supported by Sweetenham (2017) who believes that the movie theatres have to adapt to the digital age by creating a more social experience, as what has worked for the previous 100 years does not work anymore. According to Kohn (2017), it is important for the movie theatres to accept that the big screen in today’s society is optional, and that it is the streaming services like Netflix that rule the medium today. In order to create new experiences for the audience at movie theaters, Häkkilä et al. (2014) created an interactive game experience for the audience, letting them play on their phone while watching the movie. It allowed the audience to compete in catching different elements from the movie and collect some other objects on their phone. This way, the audience was able to not just sit and watch the movie, but to be active while watching, and to use their mobile devices at the same time.

Due to the lower sales in movie theatres, movie studios are focusing on the bigger movies – as they have a better chance of selling tickets (Crewe, 2017). In the recent years, big movie studios’ strategy has been to make fewer films and focus on the successful franchises that would make it to the top (Sweney, 2017). On the contrary, Netflix are focusing on having a Long Tail, in order to have something for all types of people, and attract more subscribers (Crewe, 2017). The prices in the Danish cinema are not flexible, as there is no differentiation between different movies or cinemas, which can be due to the pricing model between distributor, cinema and the studio. The only flexible pricing is extra, for movies at night, or 3D movies. The cinema prices are therefore not adjusted to the demand. (Wümpelmann, 2008, p. 97, 104) According to Smith and Telang (2016, p. 169) pricing needs to vary depending on how old the movies are. In that way you get

15

people who want to watch the content right away to pay a higher price, than the people who want to watch it but are willing to wait to get it for a lower price.

Netflix does not produce movies with the idea of distributing them through movie theatres. (Larsen, 2017). However, if they decide on a theatrical distribution, they also release the movie on Netflix the same day as it is in the cinema (Rodriguez, 2017a). Netflix simply refuses to have the movie shown exclusively in the cinema (Masters, 2016). Cinemas are refusing to book movies when DVDs or online releases are too close to the theatrical premieres. There have been tests about releasing a movie for internet download the same time it was in the theatre, in order to try decrease piracy, but it did not succeed. However, the reason why it did not succeed has never been confirmed, but rumors say it was because the theaters did not support the product because of the online window. (Ulin, 2010, p. 35) This is supported by Curtin et al. (2014, p. 11) who says that movie theaters have reacted negatively on the VOD experiments, because they believe this service cannibalizes the cinema ticket sales (Curtin et al., 2014, p. 11). And because everyone is able to watch the movie instantly online, many would justify this as cannibalizing theatrical revenues (Ulin, 2010, p. 139). However, according to a study from Korea, digital music streaming actually had a positive effect on the physical music album sales (Lee et al., 2016). Nonetheless, cannibalizing does not have to be negative for a company: Steve Jobs (as cited in Isaacson, 2011) believed that “If you don’t cannibalize yourself, someone else will” (p. 408). Although Jobs knew that the iPhone would cannibalize sales on the iPod and the iPad could cannibalize sales of the laptop, he was not discouraged by that (Isaacson, 2011, p. 408).

On the other hand, delaying digital availability of movies was shown to have a downside, as no statistical increase in DVD sales was found, while there were almost a half cut in digital sales when the digital version was released after the DVD. The reason for this can be due to the digital consumers having already gone and have found the movie on piracy sites. (Smith & Telang, 2016, p. 182-183) However, according to Yu et al. (2017) consumers actually want physical formats of videos if they are not available on other services. Therefore, they recommend to delay or even completely avoid at all having these titles on streaming services in order to reduce cannibalization. But they recommend releasing these titles after a long time on streaming sites in order to generate additional revenue.

2.2.3 Competition

One big threat for the entertainment industry is the small number of dominant players on the market, such as iTunes, Amazon, and Netflix. This means that the traditional strategy of

16

negotiating with different retailers is not possible anymore, thus the power now is in the big players’ hands. (Smith & Telang, 2016, p. 122, 179) Mister Smith Entertainment CEO David Garrett, has pointed out that Netflix and Amazon are creating their own content, and deliver it straight to costumers, this is why the middlemen are cut out. He therefore believes that the only way for film companies to get an advantage is to develop, produce and own their own content. (Goldstein, 2017) Smith and Telang (2016, p. 122, 179) agree that those big companies are less dependent on studios because of their own original content. Therefore, they argue that the studios should also integrate into direct distribution, and thereby be less dependent on distributors for getting access to customers. Wümpelmann (2008, p. 83) also mentions time as another competitor for the cinema. A movie shown in the cinema typically takes two-three hours, plus transportation time back and forth. Thus, DVDs and movies at home are more convenient for busy people who have less time. (Wümpelmann, 2008, p. 83)

Even though traditional network broadcast companies compete with different kinds of VOD, they are all competing with piracy sites (Curtin et al. 2014, p. 13). Piracy is a word for copyright theft and covers illegal copies of prints or tapes and digital copies (Ulin, 2010, p. 69-70). In 2016, approximately 12 million illegal downloads of Danish movies were made (DFI, 2017), hence piracy is still a big competitor for the Danish movie industry. According to Steve Jobs you cannot stop piracy, but you have to compete with it: One way is to make the paid version easier to use, more convenient or more reliable. (Smith & Telang, 2016, p. 98) This is supported by Monggaard (2011) and Cook & Wang (2004) who believe piracy can be fought by offering legal opportunities for people, because they are willing to pay if it is easy and fast. If a movie, is not available on any platform legally, then people simply turn to piracy. Additionally, Cook and Wang (2004) believe that there is great potential for the movie industry to fight illegal services, by changing the supply chain: First, they can have flexible exhibition windows for each movie to reach maximum revenue, but also offer VR experiences in the cinema. Furthermore, they will need to make online movies more available and at good prices in order to attract customers. Although illegal streaming and downloading is seen as a threat to the entertainment industries, it is not certain that the people watching illegally would actually spend money on buying the movie. Piracy is therefore also able to strengthen the knowledge of a movie when people watch it on piracy sites. (Smith & Telang, 2016, p. 84)

2.3

Lesson Learned

From the theory it is now learned what digital transformation is and how companies like Netflix and HBO is using the new digital technologies to attract more customers. Furthermore, it is

17

learned that the Danish movie industry is still using the traditional distribution model, which is divided into different windows, and they are having a hard time benefiting from the new technologies. Additionally, the movie theaters are hesitating to change their exclusive distribution window, and are now competing with peoples’ homes. It is also acknowledged how digitalization is much more about the Long Tail and niche products because of the bigger exposure online instead of the mass market. At last, more competitors are emerging due to the digital technologies, and one of these is piracy, and even though the movie industry will not be able to stop it, they can compete with it by making legal opportunities available for the audience instead.

18

3

Research Methodology

In this chapter you will find the methods and procedures used to create this research, as well as explanations for why these are found appropriate in order to reach the aim of the study.

3.1

Qualitative Research

This study is a qualitative research with an exploratory nature, as it seeks to explore how the Danish movie industry can embrace digitalization in order to get to its customers. A qualitative study aims at gaining a deep and holistic overview of a specific topic (Gray, 2014, p. 160), which is true for this report as the Danish film industry and its audience was the topic that was investigated in-depth. An exploratory approach was chosen, as it is useful when a topic has not been investigated much, and thereby allow the topic to be explored more by looking into what is happening in the field and asking questions about it (Gray, 2014, p. 36). As there has not been much literature or studies about digital transformation and the Danish movie industry, this was found to be the best approach to use, and in order to be able to explore this and be able to answer the “how” research question of this report, qualitative methods were found most useful (Morgan, 1998, p. 12, Creswell, 2007, p. 39). The data collection methods were both focus groups with movie audience, semi-structured interviews with film professionals and secondary data with film professionals. These data collection methods are commonly used in an exploratory study, where talking to experts in the field, conducting focus groups interviews and/ or have a search in the literature are the characteristics (Saunders et al., as cited in Gray, 2014, p. 36).

In order to get information from the “ground” and collect data from the industry, an inductive process has been followed, meaning that the research moved from data to the theory (Denscombe, 2007, p. 288). This means that the research started by conducting data from the focus groups and interviews, and after that moved more into theory. However, in inductive processes the researcher still has an idea or pre-existing theories when starting in the field as they may help formulate the overall purpose of the study, but yet they do not try to falsify or validate a theory. (Gray, 2014, p. 17-18) This was true to this study, as the researcher did have a little knowledge about the film industry before starting in the field, however, the emphasis was put on the data collection, in order to discover things from the data (Denscombe, 2007, p. 288). As an inductive process has been followed, it was not possible to have a completely pre-fixed process to follow, as some phases of the process changed, which Creswell (2014, p. 186) explains might happen after the researcher enters the field. With other words, one phase led to another in this study – a so-called trail of discovery (Denscombe, 2007, p. 90), as each focus group and interview led to new ideas and new

19

questions to go forward with. After the first interviews were done, it guided the data collection towards the importance of marketing within the movie distribution, and thus an interview was scheduled with a marketing manager.

3.2

Focus Groups

In order to get a better knowledge of the Danish movie customers and get to know what they demand in movies; the first qualitative data conducted was with three different focus groups. Focus groups create a possibility of getting a discussion going about a specific topic (Wibeck, 2010, p. 11), which in this case was about Danish movie habits. Furthermore, focus groups provide a good way to listen to people and learning from them (Morgan, 1998, p. 9), which also was important in this study in order to be able to find optimization opportunities in the models. At the very beginning of the focus groups, a “focusing exercise” was made, which included having five Danish movies that the group together should range after the year these films were released. Afterwards they were given the same exercise with American movies. Ranking exercises are a very common type of a focusing exercise (Bloor et al., 1994, p. 43), hence this was chosen. This was first of all in order to get people to feel more relaxed and get used to each other, but also in order to concentrate the group’s attention and interaction on the movie topic as Bloor et al. (1994, p. 43) have pointed out. This was not only an ice-breaker activity, but also gave some information to the study about how many of these films the participants knew of, and as Wibeck (2010, p. 40-41) points out, this can give a base for the first discussion and interaction in the group.

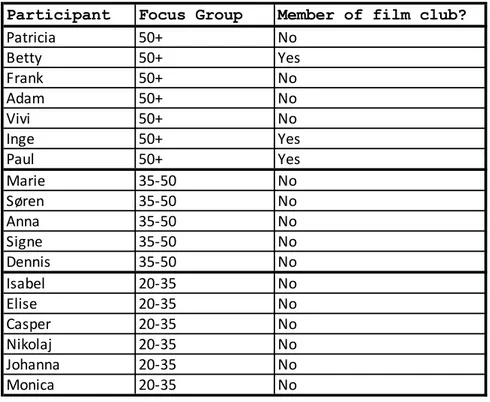

3.2.1 Participants – The audience

According to Wibeck (2010, p. 62) focus groups should not contain more than six people or less than four people, in order for every group member to be able to participate. However, according to Denscombe (2007, p. 181) the focus groups should have between six and nine participants; thus it was aimed to get around six people at each focus group to fit both arguments. It ended up being three focus groups, divided into three different age groups: 20-35, 35-50 and 50+, in order to be able to compare the similarities and differences between these different generations: Six people were in the 20-35 age group; five people were in the 35-50 age group; and seven people were in the 50+ age group, these can be found in figure 3 below:

20

In order to preserve the participants’ anonymity, they have all been given another name for the purpose of this report. The participants for the focus groups were “hand-picked” so to speak in the recruitment process, in order to get both people going to the cinema and others who do not, as well as different types of ages and backgrounds, which would be the best for the discussion and the data collection. The main sampling method was therefore purposive sampling. (Denscombe, 2007, p. 17; Morgan, 1998, p. 30) However, a few people have also been recruited through a snowballing sample, as some participants have been recruited via another person who was attending the focus group as well (Bloor et al., 1994, p. 31).

3.3

Interviews

In order to get insight of the current business- and distribution models used in the film industry, semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted as the second qualitative data. Four different professionals were interviewed: Two film distributors (one with main focus on digital sales, and another with main focus on cinemas), a marketing manager and the chairman of Danish cinemas. This was found relevant in order to hear their opinions about streaming services, and their traditional business- and distribution models. All were relevant to interview in order to compare their answers and take their similarities and differences into account when creating the new models. Additionally, the goal with these interviews was to hear their main arguments for

Participant Focus Group Member of film club?

Patricia 50+ No Betty 50+ Yes Frank 50+ No Adam 50+ No Vivi 50+ No Inge 50+ Yes Paul 50+ Yes Marie 35-50 No Søren 35-50 No Anna 35-50 No Signe 35-50 No Dennis 35-50 No Isabel 20-35 No Elise 20-35 No Casper 20-35 No Nikolaj 20-35 No Johanna 20-35 No Monica 20-35 No

21

hesitating to change their business model, and to talk with them about the future of the industry. The questions asked can be found in appendix 2.

3.3.1 Participants – The professionals

All the people interviewed were recruited through a purposive sample, as the participants were chosen based on their job titles and their experiences in the field, which was necessary for matching the criteria for the interviews and get as much relevant data for the study as possible. (Gray, 2014, p. 217) Several production- and distribution companies were contacted, many not responding to the email, a few production companies responded that they relied on their distributors, and thereby did not have anything to contribute with, and a few responded they did not have time. A total of 16 people were contacted.

3.3.2 Secondary qualitative data

Secondary analysis means to use data that has already been gathered in relation to another study previously made (Goulding, 2002, p. 56). As the topic of this study has become quite hot in Denmark after the beginning of this research, a documentary program was made for Danish television (DR), where one producer, one actor and one movie critic were interviewed. This data was found relevant for this research, as it was not possible to get primary data from any producers as aimed for in the beginning of this study. Therefore, this program was transcribed and used as secondary qualitative data together with the primary interviews in the results in order to use it for the discussion part of this study. This mean an assorted analysis was made for the secondary data, as the data re-used was carried out alongside the collection and analysis of the primary data for the same study (Gray, 2014, p. 525).

3.4

Data analysis

The focus groups, interviews and secondary data were all transcribed and then analyzed in the Nvivo text analysis software. According to Morgan (1998, p. 70) the transcript strategy produces the most in-depth and detailed analysis. Using the Nvivo software it was easier to generate codes of the text, which thereby made it possible to find common themes, patterns and categories that are stated in the results part of this paper. Both Creswell (2014, p. 197-200), Gray (2014, p. 610) and Denscombe (2007, p. 288) say that data analysis of qualitative research starts by transcribing the raw data and then get familiar with it and read the data more thoroughly. After that it is possible to code the data into descriptions, categories and themes, which are often used as

22

subheadings in the findings section. This is true to this report, as the most frequent words used for the focus groups was also found as the themes and were thereby put as the heading for the focus group results. According to Denscombe (2007, p. 294) the researcher could base the coding on different things, including a kind of event, an action, an opinion, an instance of the use of a particular word or expression, or an implied meaning or feeling. Whereas the focus groups were coded based on the usage of words, the interviews were coded into different categories, as it was not possible to analyze the interviews based on the word usage. Instead their opinions and information about the field were put into categories, for instance digitalization, which also is found as the heading in the interview results. As the data included a lot of different information, it was clear that not all could be used in the study, and therefore it was necessary as the researcher to focus on some parts of the data and disregard other, in order to use the most relevant information in the report (Creswell, 2014, p. 195; Denscombe, 2007, p. 293).

3.5

Artefact

The artefact for this paper is new business- and distribution models for the movie studios and distributors. These could allow them to adapt more to the digital era and is aimed to propose ways in which they can adjust their operations, instead of only focusing on the old traditional business model, which counts for the cinema to be the main channel of income. The model was made based upon the findings from the interviews and the focus groups. The new business- and distribution model was thereafter evaluated by doing interviews with two people outside the film industry, who are both professionals working with new businesses and business models on a regular basis. They were therefore able to provide feedback on the first draft of the artefacts. Their feedback then made room for adjustments, which ended up being the final artefact.

3.5.1 Business Model Canvas

In order to create a new type of business model for the Danish movie industry, the Business Model Canvas (BMC) was used. Before making the new business model draft, the BMC was filled out in order to get an overview of the current film industry. Thereafter, a new Business Model Canvas for each part of the industry was made based upon the answers from the interviews and the focus groups. According to Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010, p. 15), the Business Model Canvas enables companies to describe and reflect over its business model or competitors, and the BMC makes it easier to describe and handle business models with the aim of creating new strategic alternatives. The model simply makes it easy to see and evaluate how all the parts fit together (Greenwald, 2012). Therefore, this was a great tool to use in order to come up with new solutions for the movie

23

industry and see how it would work together in the different parts. The BMC consists of nine parts: Customer segment, value proposition, channels, customer relationships, revenue streams, key resources, key activities, key partners and cost structure (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010, p. 16-17).

3.5.2 Porter’s Value Chain

The value chain was used as a framework in order to get a better overview of the whole film industry business and to explore what activities could be optimized in order to be able to compete with its digital competitors. The value chain is divided into two different activity types: The primary activities and support activities. The primary activities being: Inbound Logistics, Operations, Outbound Logistics, Marketing & Sales and service. And the support activities being: Procurement (purchase), Technology Development, Human Resource Management and Firm Infrastructure. (Porter, 1985, p. 33, 38-42)

3.6

Ethics

As it is important to protect the participants in a study, everyone participating in this research was made aware of the purpose of this project, that their information would not be given to third parties, and that their information would be used for this study only (Denscombe, 2007, p. 173). Furthermore, all participants, both in the interviews and the focus groups were able to leave at any time during the interviews and were free to choose whether to answer the given questions or not, which Gray (2004, p. 235) points out is important in order to work ethical. In order to make sure all the participants understood and gave permission for the above, every focus group participant had to sign an informed consent form. The informed consent was written in a formal yet easy to understand format, in order to make sure it was user-friendly, as Wiles (2013, p. 27) points out that the way information is provided to the participants is important. The people interviewed were given the informed consent orally, which was recorded and they were asked whether or not their name and title was allowed to appear in the thesis. The focus group participants will be anonymous; thus, they have been given another name for the purpose of the report. Thereby, they cannot be identified by the readers, which give them the freedom to talk about their thoughts freely without later being judged or harmed by anyone. Due to the fact that a few of the participants were recruited through a snowballing sample, it was even more important to make sure that these participants knew what they were going in to, and that they were informed, as it is the researcher’s responsibility to ensure that the guidelines are followed (Bloor et al., 1994, p. 32).

24

3.7

Reliability, validity &

transferability

Reliability and validity are factors that are often associated with quantitative research (Bryman, 2012, p. 43). The reliability issue means whether the results would be the same if another researcher was doing the same study over again (Denscombe, 2007, p. 296). However, a problem with this in qualitative research is that the results are based on the participant’s feelings and opinions, and it is hard to get people to say exactly the same again. Therefore, the results may vary if a research is done again with the same methods, as it depends on the people interviewed. However, in order to try to reduce bias, all the data in this report was transcribed and analyzed in a computer software, as mentioned previously. According to Kruger, 1998, p. 11) using such a systematic analysis procedure helps ensure that the results will be as authentic as possible. Validity means how accurate the findings are to the topic (Creswell, 2014, p. 190). The validity issue of a research is important to recognize, and as this study are limited to seven film industry professionals in total and only 18 people in focus groups, it can be argued whether this sample is big enough to generalize the results and make them valid. However, this study does not want to generalize from the results as some qualitative researchers do, instead it is tried to make a study that is authentic and dependable in a specific context – the film industry (Gray, 2014, p. 160). Furthermore, in order to get as much reliable and valid results as possible for this research, a within-method triangulation was done as both focus groups, interviews and secondary data was used for analysis and thereby used data from varies data gathering techniques. Furthermore, the data was conducted with people working in the movie industry as well as a Danish movie audience in several ages, giving more trustworthy results, as it combines both the audience and business perspective. (Gray, 2014, p. 184-185) According to Denscombe (2007, p. 299) it is important in qualitative research based on small numbers of data, to have an alternative way of addressing the issue about generalization. Instead of being able to generalize, the researcher should focus on transferability, in the way to what extent the results would be transferable in other comparable instances. The models proposed in this paper are made on the basis of the information gotten from the film industry. However, other industries may also be able to use the models or the concepts, especially when looking at where the adjustments are found – the value proposition and the segments. Other industries are able to use this information when wanting to go through a digital transformation, and when not knowing how to get started or what to focus on, as this study provides the industries with some research about how the digital technologies can be adapted to enhance customer experiences.

25

4

Results

This chapter gives an overview of the findings from the focus groups, interviews and the creation of the new business- & distribution models and the evaluation hereof. Together with the background, this information will be the base for the discussion chapter later.

4.1

Focus Groups

In order to understand the customer demands, which constitute a main part of RQ1, the focus group participants were asked about their movie habits, their thoughts on Danish movies and their cinema visits. Please find the questions asked in appendix 1.

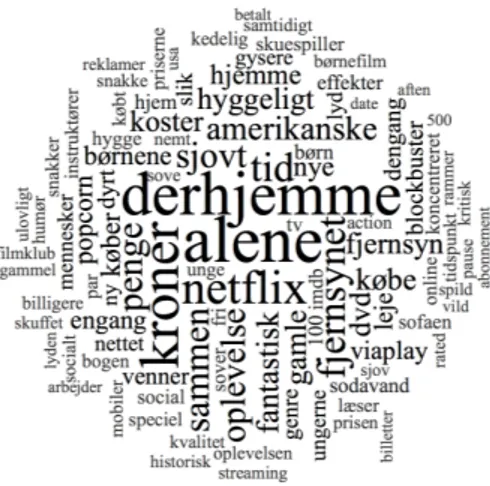

Below in figure 3, is a word cloud showing the different words the focus groups used the most in their discussions. The bigger the word, the more it was used.

Figure 4 - Word Cloud showing main themes at the focus groups (Nvivo)

4.1.1 At home vs. an experience

(derhjemme2 vs. enoplevelse)

The word “at home” came up 53 times in the focus group interviews and covered how the majority of the participants preferred watching Danish movies at home. However, the participants also mentioned that watching a movie in the cinema is a different experience than watching it at home. Nevertheless, many agreed that watching a Danish movie at home is the same experience as watching it in the cinema. Yet, both Frank and Monica disagreed a little with the majority, as Monica preferred watching Danish movies in the cinema and Frank said that the Danish comedy