School of Health Care and Social Welfare

Collaboration between health promoting

actors in a rural community

- Maciene, Mozambique

Master Thesis in Public Health Science Level D

30 ECTS points Public Health Science OF0240

Date: 2008-01-30 Author: Helene Lidquist Supervisor: Maja Söderbäck Examiner: Christina Lindholm

ABSTRACT

In community health promotion intersectoral collaboration is essential. Important actors are the governmental health system, the civil society and Non-Governmental organisations

(NGOs). The aim of this qualitative thesis was to examine what kind of cooperation existed in a rural community in Mozambique and to describe the actor’s experiences of collaboration and how it can be improved. This was done by conducting interviews. The result of the study showed that different ways of cooperation existed, intersectoral as well as side by side and intrasectoral. The extent of intersectoral collaboration was fairly loose, such as networks, alliances or partnership. All the informants were positive to collaboration, they had

experienced that people had been helped and their knowledge in health issues was improved as an effect of joint efforts. The experience among the actors was that the collaboration had improved and that they had become closer together over the years. Problems to cooperation that were mentioned concerned dropouts and financial issues. The informants were

unanimous that it was necessary to broaden the collaboration. They were concerned over the sustainability in the different projects as well as the sustainability in cooperation itself.

Keywords: Actors, community health promotion, intersectoral collaboration, low income

country

SAMMANFATTNING

I det lokala folkhälsoarbetet är den intersektoriella samverkan väsentlig. Viktiga aktörer är hälsosystemet, det civila samhället och frivilligorganisationer. Syftet med denna kvalitativa uppsats var att undersöka vilken typ av samverkan som förekom i en ort på landsbygden i Moçambique samt att beskriva aktörernas erfarenheter av samverkan och hur den kan förbättras. Detta gjordes genom intervjuer. Resultatet av studien visade att olika former att samverkan förkom, intersektoriell men även sida vid sida och intrasektoriell. Graden av intersektoriell samverkan var ganska lös, såsom nätverk, allianser eller partnerskap. Alla informanterna var positiva till samverkan, de upplevde att människor blev hjälpta och deras kunskaper i olika hälsofrågor ökade via gemensamma insatser. Aktörerna upplevde också att samverkan hade förbättrats och att de hade kommit närmare varandra de senaste åren.

Problem för samverkan som framkom var, avhopp och ekonomiska frågor. Informanterna var eniga att det var nödvändigt att vidga samverkan. De var också bekymrade över hållbarheten i de olika projekten liksom hållbarheten i samverkan i sig.

Nyckelord: Aktörer, intersektoriell samverkan, lokalt folkhälsoarbete, låginkomst land

ABSTRATO

Para a promoção da saúde em comunidade a colaboração intersetorial é essencial. O sistema público de saúde, a sociedade civil e as organisações não governamentais (ONGs) são importantes agentes. O objetivo desta tese qualitativa foi examinar qual tipo de cooperação existiu em uma comunidade rural em Moçambique e descrever as experiências de colaboração dos agentes e como ela pode ser melhorada. Isto foi feito através de entrevistas. O resultado

do estudo mostrou que existiram diferentes modos de colaboração: intersetorial assim como intrasetorial de forma paralela. O nível da colaboração intersetorial foi relativamente informal assim como redes de contato, alianças e parcerias. Todos os entrevistados foram positivos a colaborar e experienciaram que as pessoas tinham sido auxiliadas e que seus conhecimentos acerca de assuntos de saúde foi melhorado como resultado da união de esforços. A

experiência entre os agentes foi de que a colaboração foi melhorada e que eles se tornaram mais próximos através dos anos. Problemas acerca de colaboração que foram mencionados foram devidos a desistências e questões financeiras. Os entrevistados foram unânimes sobre a necessidade de aumento do nível de colaboração. Eles estavam preocupados sobre a

sustentabilidade de diferentes projetos assim como a sustentabilidade da cooperação em sí própria.

Palavras-chave: Agentes, promoção de saúde comunitária, colaboração intersetorial, país de

CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

2. BACKGROUND ... 1

2.1 Abbreviations ... 1

2.2 Health in low income countries ... 2

2.2.1 Health inequalities between high and low income countries ... 3

2.3 Community health promotion ... 4

2.3.1 Actors in community health promotion ... 5

2.3.2 Intersectoral collaboration ... 6

2.3.3 Coalition theory ... 8

2.3.4 Factors affecting collaboration ... 9

2.4 Community health promotion in Mozambique ... 12

2.4.1 Health indicators ... 13

2.4.2 The setting - Maciene ... 14

3. AIM ... 15

3.1 Survey questions... 15

4. METHOD ... 15

4.1 Research approach ... 15

4.2 Access to the field study ... 16

4.3 Procedure for data collection ... 17

4.4 Data analysis ... 18

4.5 Ethical principles and considerations ... 18

5. RESULTS ... 19

5.1 Health promotion actors in Maciene ... 19

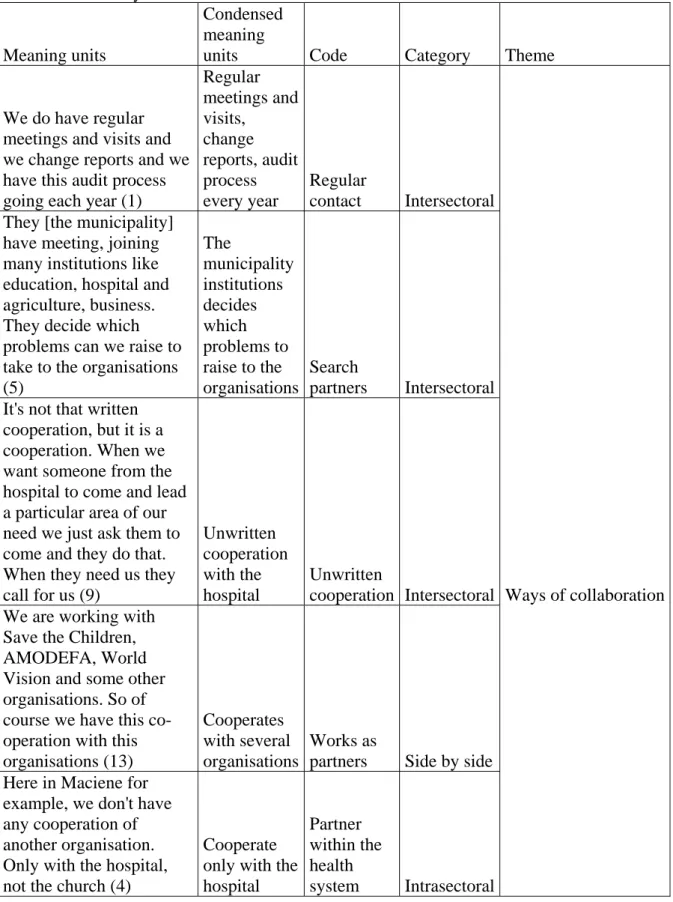

5.2 Ways of collaboration ... 21

5.2.1 Intersectoral collaboration ... 21

5.2.2 Activities side by side ... 22

5.2.3 Intrasectoral collaboration ... 22

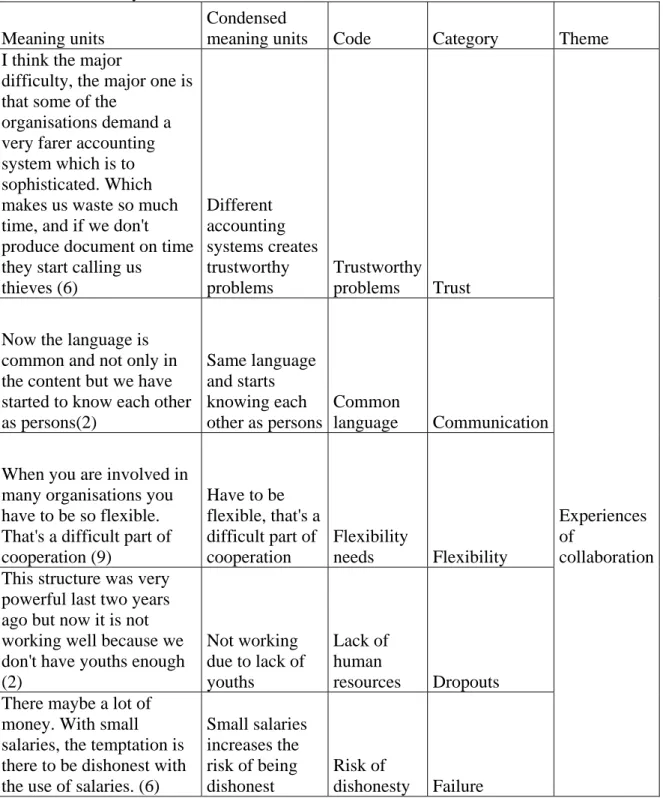

5.3 Experiences of collaboration ... 22

5.3.1 Relationship, trust and communication ... 23

5.3.2 Joining and flexibility ... 23

5.3.3 Improvements ... 24

5.3.4 Dropouts and failure ... 25

5.4 To improve collaboration ... 25

5.4.1 Broaden intersectoral collaboration ... 25

5.4.2 Sustainable collaboration ... 26

6. DISCUSSION ... 27

6.1 Methodological discussion ... 27

6.2 Discussion of the result ... 29

6.2.1 The actors ... 29

6.2.2 Existing collaboration ... 30

6.2.3 Prerequisites and barriers ... 31

6.2.4 Room for improvement ... 33

6.3 Implications ... 34

7. CONCLUSIONS ... 35

Appendix I: Interview guide on central and supervisor level Appendix II: Interview guide on local level

Appendix III: Example of data analysis – ways of collaboration Appendix IV: Example of data analysis – experiences of collaboration

1. INTRODUCTION

Health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health (WHO 1986a). Health promotion work includes working with both individuals and groups to enhance their knowledge and understanding what factors that affects their health (Nadioo & Wills 2000). It is not only the health sector but the whole society that is responsible for the inhabitants’ health. Therefore effective health promotion involves collaboration between actors from different sectors, governmental, civil society and NGOs (Walley, Wright & Hubley 2001). This intersectoral collaboration is supposed to have its greatest potential at community level where the sectoral barriers can be broken down (WHO 1986b).

In Mozambique NGOs have been implementing health promoting projects for many years and a common opinion is that complexity occurs when many actors are at the same arena. It would therefore be interesting to examine what kind of collaboration that exists in a rural community and which experiences there are among the actors. The topic of the study has been determined in consultation by the student; her supervisor at Mälardalen’s University, Maja Söderbäck; and Father Carlos Matsinhe, Dean of the Anglican Church in Maciene so it would be of benefit for the community.

The student has been interested in other cultures since many years and was pleased to have got this opportunity. She had also some previous experience of studying cooperation between health promoting actors as she in her bachelor thesis wrote about collaboration among actors involved in the integration of refugees and immigrants in Västerås. It would therefore be of interest to study collaboration in a country with other conditions.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1 Abbreviations

AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

FDC Foundation for Development of the Community HIV Human Immune deficiency Virus

MDG Millennium Development Goals NGO Non-Governmental Organisation NHS National Health Service

PHC Primary Health Care

PRA Participatory Rural Appraisal methodology STD Sexually Transmitted Diseases

UNFPA United Nations Population Fund UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund WHO World Health Organisation

2.2 Health in low income countries

Many of the major health hazards in high income countries are already reaching significant proportions in the low income countries. These countries have to deal with the urgent health problems of today as well as with future health issues. They need to examine how they can avoid or mitigate the health risks that are associated with industrialisation and development (WHO 1986b; Scriven & Garman 2005). Health is determined by a range of personal, social, economic and environmental factors (WHO 1998). Some health inequalities are attributable to biological variations or free choice and others are attributable to the external environment and conditions mainly outside the control of the individuals concerned. It is essential to

distinguish between inequality in health and inequity. In the first case it may be impossible or ethically or ideologically unacceptable to change the health determinants and so the health inequalities are unavoidable. In the second, the uneven distribution may be unnecessary and avoidable as well as unjust and unfair, so that the resulting health inequalities also lead to inequity in health1.

For global health promotion the factor of inequality is of special significance not only because of the strong links made with health aetiology but also because increased health inequalities between rich and poor countries call into question the authenticity of the rhetoric of

cooperation, participation and empowerment with which it has become associated. The striking difference in health status of populations in countries of comparable national wealth has redirected attention to the effectiveness of policies in protecting the health of populations (Townsend & Gordon 2002). According to Sen (1999) research suggests that effective social policies can improve health even in low income countries with little economic growth. A number of international initiatives either directly or indirectly can play a role in tackling inequalities in health. The United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) focus on health promotion activities for low income countries and aim to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, reduce child mortality, improve maternal health and combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases2. Other health related issues to be achieved include increasing access to clean drinking water, slum clearance, reducing gender disparities, and improving access to primary education and to affordable essential drugs (Scriven & Garman 2005). The current MDGs focus much on issues related to communicable diseases, and are less appropriate for tackling other global health inequalities. The deterioration of health status in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, where outcomes are approaching the level observed in some African countries, are largely due to increases in rates of injuries, accidents and violent activities, of which none are covered in the MDGs on health (Lock et al. 2002).

According to Walley, Wright and Hubley (2001) has much been done to improve the health of people throughout the world over the last century. Public health policies have provided

healthier environments with clean water, effective sanitation, and better housing. Programmes have supported immunisation campaigns to prevent communicable diseases, such as

tuberculosis, malaria, measles, pertussis and polio. Preventive health services, such as maternal and child health services have also been provided. Health promotion campaigns have attempted to change individual risk-taking behaviour and to improve awareness about the factors that cause disease and how they can be avoided. Yet inequalities in income and health continue to widen, not just in low income countries but throughout the world. Scriven and Garman (2005) mean that inequalities exist within as well as across countries, although

1

http://www.who.int/hia/about/glos/en/index1.html 2007-05-15

2

they are complex to measure and explain. They have formed the focus of attention in high income countries, but because of data limitations in low and middle income countries evidence is more limited, and where available predominantly concentrates on issues of child and maternal health. There is a need to improve data collection systems in low income countries in order to capture more information on geographic, socioeconomic, gender and ethnicity-related variations. Access to additional data therefore can help identify non-poverty related aspects of health inequalities and are essential for determining whether health

promoting strategies are reaching their intended target groups. Improved access to data is also needed to help identify effective approaches to tackling problems associated with economic transition and growth in countries. As nations develop and health status improves, disease patterns change, with a greater burden related to non-communicable diseases, such as accidents, heart disease, stroke and cancer, and a need to increase the focus on adult health.

2.2.1 Health inequalities between high and low income countries

Child mortality rates are one of the key indicators used to identify health inequalities between high, middle and low income countries, because much of the variation in the global average life expectancy is due to profound differences in mortality rates for children, especially in the first five years of life (Scriven & Garman 2005). Globally deaths in children under five have decreased from 17.5 million in 1970 to 10.5 million in 2002. Of the current deaths almost all, 98 per cent occur in low and middle income countries where children are more exposed to many risk factors, such as lack of sanitation and clean water, poor housing conditions, malnourishment and lack of education. Disparities in child health between and within

different low and middle income regions are also growing. Mortality levels are now higher in 16 countries than they were in 1990, 14 of these are in Africa, and overall 35 per cent African children are at a higher risk of death than they were in 1992 (WHO 2003). Wang (2003) found in his study, a strong negative correlation between the average rate of child mortality and the level of inequality in child mortality rates. Countries where child mortality rates had decreased, inequalities in mortality by socioeconomic position had increased. Variations in mortality rates between urban and rural areas within the countries were also identified. Child mortality in rural areas was substantially higher than in urban areas, the reduction in child mortality was much slower in rural areas where the poor are concentrated. This suggests that health interventions implemented in the past decade may not have been as effective as intended in reaching the poor.

Globally life expectancy has improved for those who reach adulthood by between two or three years over the last twenty years. There are two notable exceptions to this trend. One is parts of Africa where life expectancy has been reduced by approximately seven years due to the spread of HIV/AIDS. The other is the former Soviet Union and parts of Eastern Europe where life expectancy has fallen by almost five years for men since the 1990, and the risk of death from injuries, including suicide, is now six times higher than in Western Europe. Of all worldwide deaths related to HIV/AIDS in 2002, 80 per cent occurred in Africa. Average life expectancy at birth ranges from 81.9 years in Japan to just 34.0 years in Sierra Leone, and of the 50 countries with the lowest rates 44 are to be found in sub-Saharan Africa, with just five in Asia and one in the Caribbean (WHO 2003). Maternal death rates are more than 100 times higher in sub-Saharan Africa than in high income countries. Within countries disparities are again found. The risk of maternal death in Indonesia, for example, is three to four times greater in the poorest income quintile of the population compared to the richest (Graham et al. 2004).

2.3 Community health promotion

The Ottawa Charter is regarded as the formal beginning of the New Public Health movement (Beaglehole & Bonita 2004). The first WHO International Conference on Health Promotion was held in Ottawa 1986 and the charter (WHO 1986a) was the outcome. It highlighted the conditions and resources required for health and set out the action required to achieve Health for All by the Year 2000. The fundamental conditions and resources for health are peace, shelter, education, food, income, a stable ecosystem, sustainable resources, social justice and equity. Improvement in health requires a secure foundation in these basic prerequisites. In the Ottawa Charter five action areas are designed to promote health. One of them is create

supportive environments which involve protection of both the natural and built environment.

The conservation of natural resources throughout the world should be emphasized as a global responsibility. Changing patterns of life, work and leisure has a significant impact on health. Work and leisure should be a source of health for people. Another one is strengthen

community action as communities themselves are the experts in their own community and

should determine what their needs are and how they can best be met. Community

development draws on existing human and material resources in the community to enhance self-help and social support, and to develop flexible systems for strengthening public participation in and direction of health matters. This requires full and continuous access to information, learning opportunities for health, as well as funding support. The remaining three areas are; to develop personal skills, reorient health service and build healthy public policy. Talbot and Verrinder (2005) point out that the strength of the Ottawa Charter is that it incorporates both selective and comprehensive perspectives of Primary Health Care. These five action areas used collectively have a far better chance of promoting health than when they are used singularly. Naidoo and Wills (2000) state that health promotion encompasses different political orientations that can be characterised as individual versus structural approaches. Some see it as a narrow field of activity referring to individuals’ lifestyles and that an expert determines the process and it emphasis on personal responsibility where the state has a minimal role. Others recognise that health and wealth are inextricably linked and use challenging approaches to seek the root causes of ill health and problems of inequity. One is not better than the other, both are necessary. Health promotion involves working with individuals and groups to enhance their knowledge and understanding of the factors that affect health.

A health promotion programme can have a “top-down” or a “bottom-up” perspective (Laverack & Labonte 2000). The former is more associated with disease prevention efforts, and begins by seeking to involve particular groups or individuals in issues and activities largely defined by health agencies where improvement in particular behaviours is regarded as the important health outcome. The latter is used in lesser extent, and is more associated with concepts of community empowerment. It begins on issues of concern to particular groups or individuals and regards some improvement in their overall power or capacity as the important health outcome.

WHO (1986a) has identified three ways in which practitioners can promote health. The first one is advocacy which means to represent the interests of disadvantaged groups and speak on their behalf or lobbying to influence policy. People’s knowledge and understanding of the factors which affect health should be increased and health promoters should work to empower people so they may argue their own rights to health and negotiate changes in their personal environment. The second is enablement, health promotion should aim to reduce differences in

current health status and ensure equal opportunities to enable all people to achieve their full health potential. Health promoters should work with individuals and communities to identify needs and help to develop support networks in the neighbourhood. Enablement is an essential core skill for health promoters since it requires them to act as a catalyst and then stand aside, giving control to the community. The last one is mediation where it states that health

promotion requires coordination and cooperation by many agencies and sectors. Working with health promotion is to mediate between different interests by providing evidence and advice to local groups: by influencing local and national policy through lobbying, media campaigns and participate in working groups.

Partnerships working in communities with concentrated poverty face several unique barriers. Economic problems, such as high unemployment or inadequate housing, often overshadow the categorical health concerns, such as substance abuse or childhood immunizations.

Although social and economic problems are likely to be interconnected with health concerns, the community may not have sufficient resources to allocate to multiple and interrelated issues. Mobilizing citizens around distant health concerns, such as reducing risks for

cardiovascular diseases, may be particularly difficult. Resources for proximal concerns, such as youth violence or crime, might be better allocated to addressing the fundamental social determinants (e.g. education and jobs). Competition for scarce resources and economic and social gaps between low-income residents and those with financial resources may further challenge collaborative and substantial investments in local work (Roussos & Fawcett 2000). Empowerment, a process through which people gain greater control over decisions and actions affecting their health, has been proposed as one of the main aims of health promotion in communities. This has been proposed despite lack of evidence for the impact of

empowerment programmes on health even with growing literature on the topic (Scriven & Garman 2005).

To develop interventions that will be effective in the prevention of diseases and the promotion of health is one of the most important challenges in community-based health promotion (Walley, Wright & Hubley 2001). Well-planned programmes which take into account the many factors that influence the health of a community is the only possible way. Three different areas have shown to be important to prevent diseases and promote health of the community; communication, service delivery and structural/enabling factors. The balance of activities between these areas depends on the nature of the health topic and the extent to which it is influenced by lifestyle factors, appropriate health services or the wider

social/political environment. Enabling factors can not usually be changed through actions of health services alone. They require involvement of other sectors including community development, women’s affairs, agriculture, education and the legal system. Effective health promotion therefore involves intersectoral collaboration. The way this is achieved is through formation of health coalitions – networks of government and NGOs working together to achieve promotion of health.

2.3.1 Actors in community health promotion

According to WHO (2000) actors in governmental health system have an important role in reorienting health services to integrate health promotion and disease prevention into the health care delivery process. It is also necessary to incorporate health promotion principles into health service management as an integral part of every stage of the system. It was

of the Ottawa Charter, development had been inconsistent and there had been no systematic analysis of what has happened and what was possible.

The Wikipedia1 describe a civil society as composed of all the voluntary civic and social organisations and institutions that form the basis of a functioning society opposed to the force-backed structures of a state and commercial institutions. Actors are for example

charities, community groups, trade unions and advocacy groups. WHO (2005) stated that civil society and communities often lead in initiating, shaping and undertaking health promotion. It is necessary to have the rights, resources and opportunities to enable contributions to be amplified and sustained. In less developed communities, support for capacity building is particularly important. Well organized and empowered communities are highly effective in determining their own health, and are capable of making governments and the private sector accountable for the health consequences of their policies and practices.

Non-Governmental organisations have been defined by the World Bank2 as private organisations that pursue activities to relieve suffering, promote the interests of the poor, protect the environment, provide basic social services, or undertake community development. NGO activities can be local, national or international. According to Lindstrand et al. (2006) they may either be member organisations (with individuals as members) or umbrella organisations (with other organisations as members). The line between governmental organisations and the private sector is not always clear. In some countries, especially the former socialist countries, NGOs were often regarded with mistrust and had to work in close connection with governments. In some countries the Red Cross association can still be seen as a semi-governmental entity. Delisle et al. (2005) came to the conclusion that NGOs can also have a principal role in the process of shaping research priorities, advocating for more relevant research, translating and using research findings. They also have a crucial role in generating new knowledge in areas where they may have a comparative advantage, notably qualitative, social, action, evaluative and policy research. NGOs collaboration with research organisations should be seen as means of a mutual enhancement of health research capacity and contribution to development.

2.3.2 Intersectoral collaboration

There are many different and sometimes contradictory definitions of concepts like coordination, cooperation and collaboration (Leutz 1999). In this study cooperation and collaboration are used synonymously, meaning a voluntary agreement reached between two persons, a group of people or two or more actors from different sectors, to work together towards a shared aim. It is important to distinguish intersectoral collaboration with

intrasectoral as intrasectoral is collaboration between actors within a sector (Hornby 2000).

There also seems to be a conceptual confusion related to the problem of intersectoral relations. These relations have been described as networks, partnerships, coalitions and strategic alliances of organisations, or as ecology of organisations (Hannan & Freeman 1989). Intersectoral collaboration has also been described in terms of community health partnerships, healthy alliances or “socio-ecological” approaches to prevention and health promotion

(Davies & Macdonald 1998). Intersectoral collaboration is defined by WHO (1998, page 14) as “a recognised relationship between part or parts of different sectors of society which has

1

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civil_society 2007-12-10

2

been formed to take action on an issue to achieve health outcomes or intermediate health outcomes in a way which is more effective, efficient or sustainable than might be achieved by the health sector acting alone”.

Intersectoral cooperation for health has been accepted as one of the guiding principles of the health strategy and was adopted at WHO International Conference on Primary Health Care (PHC) in Alma-Ata 1978 (WHO 1978). This strategy (WHO1986b) changed the priorities in the health care sector, moving from a health perspective that was disease-oriented and

curative to a perspective that emphasized prevention of ill health, removal of health risks and promotion of health. To enable intersectoral collaboration changes in the process of

development planning, resource allocation and budgetary procedures are necessary. Normally the development planning system organises activities vertically in sectors, neglecting

horizontal linkages with major synergistic impact on development. The greatest potential for intersectoral cooperation is often found at the community level. It is here the sectoral barriers can be broken down as the community perceives development as a composite whole in which the activities of various sectors are interdependent and contribute together to its well-being. In their article, reporting from the International Conference – Intersectoral Action for Health in 1997, Kreisel and von Schirnding (1998) write that intersectoral action for health had contributed many excellent examples of infrastructure development, institutional reforms, sustainability of health actions, empowerment of people, health gains and reduction of health inequities at global, national and local levels. It was also established that documentation and the analysis of studies needs to be done more systematically to determine what works under which political, social and cultural conditions and which intersectoral linkages work best and on what geographical scales. Limited empirical evidence has also been mentioned by O’Neill et al. (1997) and Roussos and Fawcett (2000). This is one of two factors pointed out by

O’Neill et al. (1997) why intersectoral work fails more often than it succeeds. The other one is that those health-related professionals are used to operate in a very prestigious sector. They often approach other sectors expecting them to accept their issues without regarding how the health sector can support other sectors. Roussos and Fawcett (2000) consider that

collaboration between partners is a promising strategy for engaging people and organisations in the common purpose of addressing community-determined issues of health and well-being. Scriven and Garman (2005) state that few studies measured the long-term impact,

sustainability of interventions or provided cost-effectiveness of the methods used. Another problem was that much evidence of effectiveness of health education and health promotion came from small-scale pilot programmes that are often not sustained beyond the lifetime of the project. Scaling up and integrating these improved practices within routine services are vital in order to achieve a meaningful impact on the health of communities. Scriven and Garman (2005) also meant that there is clear evidence that effective health promotion can be carried out within the demanding conditions found in low and middle income countries. The challenge is to put this into practice.

Butterfoss and Francisco (2004) also pointed out the importance of evaluation in developing and sustaining community collaboration. They suggested that evaluation should be measured at three levels; (a) processes that sustain and renew collaboration infrastructure and function; (b) programs intended to meet target activities, or those that work directly toward the

collaboration goals; and (c) changes in health status or the community. They also meant that if collaboration is to survive, it must produce more than a sense of solidarity among members; it must engage in the tasks and produce the products for which it was created. The participants must be aware of both the short-term changes and the long-term changes. Kreuter, Lezin and

Young (2000) meant that quick wins may help to maintain member interest but is unlikely to lead to significant outcomes. Scriven and Garman (2005) report that an interesting

development in community based health promotion has been the movement for participatory rural appraisal methodology (PRA), also called participatory learning and action, and health analysis and action cycle. PRA uses a range of methods to help communities to identify their needs and develop solutions to their problems. Challenges are that the process requires skilled field staff; it has to be repeated with each separate community and is therefore labour

intensive.

2.3.3 Coalition theory

Nutbeam and Harris (2004) point out that there is not only one model by which organisations work together concerning partnerships or coalitions, there is a wide spectrum. At one end, there are relationships between actors where the motive may be to simply share information and meet regularly to discuss common problems. At the other end, there can be highly

structured partnerships where roles, responsibilities and outcomes are mandated. O’Neill et al. (1997) base their model, Coalition theory, on Gamson’s (1961) four parameters which predict the formation and evolution of a coalition. O’Neill el al. (1997) also added a fifth parameter based on Hinckley’s suggestions that the organisational context refers to rules defined by the environment (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Continuum of ways organisations work together

Source: Nutbeam & Harris (2004) adapted after O’Neill (1997)

Nutbeam and Harris (2004) also meant that there are few theories or models that define intersectoral action for health and none that enjoy universal recognition among health

promotion workers. Attempt has been made to review experiences in intersectoral action and in related activities such as coalition-building and partnerships. Different forms of

intersectoral action and sets of factors have been identified that are important to understand in the process by which organisations or parts of organisations work together. According to Lasker, Weiss and Miller (2001) different investigators have used a variety of approaches to conceptualise the functioning of health collaborating teams. Those efforts have shed

considerable light on various aspects of the teams functioning but lacking in the work is an explication of the pathway through which collaborating teams functioning influences the effectiveness. To strengthen the ability of collaborative teams to realise the full potential of collaboration, funders and participants in cooperating work need to know what influences the ability of collaboration to achieve this outcome.

2.3.4 Factors affecting collaboration

Working together with others is never simple, but with collaboration across organisations the complications are magnified (Huxham 1996; Weick 1979). This kind of collaboration requires

structures, relationships and procedures that are quite different from the way many people

and actors have worked in the past. Building effective collaborating teams is time consuming,

resource intensive and very difficult (Fawcett et al. 1997; Kreuter, Lezin & Young 2000;

Mitchell & Shortell 2000; Wandersman, Goodman & Butterfoss 2005).

Financial and in-kind resources are the basic building blocks of synergy. It is by combining these resources in various ways that partners create something new and valuable that

transcends what they can accomplish alone (Alter & Hage 1993; Huxham 1996; Israel et al. 1998; Mitchell & Shortell 2000). Beyond these basic resources a broad array of skills and expertise it is also necessary to engage partners support in the collaboration process, and carry out and coordinate the multiple components of their interventions. Examples of such skills include community organising, outreach, leadership, communication, management, training, clinic care, public health practice and evaluation. Information which forms the basis for joint problem solving is also an essential resource for achieving synergy (Lasker, Weiss & Miller 2001).

Building relationships is probably the most daunting and time-consuming challenge collaborating teams’ face. To think in new ways it is necessary that the people in the group are able to talk to each other and are influenced by what they hear. They also need to be willing to coordinate their activities (Kreuter, Lezin & Young 2000). Trust is one of several aspects that are likely to influence which collaborating teams achieve high levels of synergy. To work closely together, the people and actors involved in a collaborating team need to be confident that other partners will follow through on their responsibilities and obligations and will not take advantage of them (Goodman et al. 1998). Huxham (1996) points out that there is a difficult balance between autonomy and accountability in a multidisciplinary team, which requires a skilful communication based on knowledge of the actors involved. Wolff (2001) means that communication is the lifeblood of a collaborating team. Ensuring that all members understand the collaborating team’s actions, builds ownership and trust.

Other factors that are likely to have a strong influence on the level of collaborating teams’ synergy are: leadership, administration and management, governance and efficiency of

collaboration. These factors affect the ability of collaborating teams to actively engage an

partners, and combine the perspectives, resources, and skills of different partners (Kegler et al. 1998; Lasker, Weiss & Miller 2001). One of the key challenges of collaboration is that the type of leadership needed to achieve synergy is not the type of leadership most sectors and professions are producing (Alter & Hage 1993). The collaborating team leaders should be able to articulate what the partners can accomplish together, and how their joint work will benefit not only the community but also each of them individually. They also need strong relationship skills to foster respect, trust, inclusiveness and openness among partners; create an environment in which differences of opinion can be voiced; and successfully manage conflict among partners (Alter & Hage 1993; Lasker, Weiss & Miller 2001).

The administration and management of a collaborating team is the “glue” that makes it possible for multiple, independent people and actors to work together. Actors that seek high levels of synergy require approaches that are more flexible and supportive (Lasker, Weiss & Miller 2001). One important management function is to coordinate the different activities within the programme as well as with external activities. Confusion can occur when different actors working in the same community have different objectives or adopt different approaches (Walley, Wright & Hubley 2001). Governance is a key to how collaborating teams function and has a profound effect on the team’s synergy level. Through procedures that determine who is involved in decision making and how the collaborating team make decisions and do their work governance influences the extent to which partners’ perspectives, resources, and skills can be combined (Butterfoss, Goodman & Wandersman 1996; Mitchell & Shortell 2000; Potapchuk, Crocker & Schechter 1999). Within teams where the members know and trust each other, are working close together, and have similar interests, values and goals, decision-making is usually collegial or consensual and there is a common team culture (Vangen & Huxham 2003).

Different formal structures and organisational cultures among the actors have been found common. These cultural differences were based on professional attitudes and behaviours, which were related to the different roles and tasks of the organisations (Bate 2000). He suggests it is necessary to develop models that manage organisational culture. This would make all the difference between whether the problems become manifest and destructive or get properly addressed and managed. The structural barriers to intersectoral collaboration usually can be managed by the actors involved through formal agreements on rules, regulations and financial support (Hultberg et al. 2003). Mattesich, Murray-Close and Monsey (2001) state it is significant that every level within each actor has at least some representation and ongoing involvement in the collaborative initiative. Flexibility is also important; the collaborative teams need to be flexible both in their structure and in their methods.

Conflict and power differentials have also been emphasised in discussions of partner

interactions (Alter & Hage 1993; Mitchell & Shortell 2000). Conflict can foster synergy if differences of opinion sharpen partners’ discussions on issues and stimulate new ideas and approaches. But if conflict is not managed well, the same differences of opinion can lead to strained relations among partners. Power differentials among partners also have the potential to seriously undermine synergy since they limit who participates, whose opinions are

considered valid, and who has influence over decisions made (Israel et al. 1998). The process of building a multidisciplinary team goes through a series stages (Tuckman 1965). First there is the forming stage, when the members of the team through testing identify the boundaries of both interpersonal and task behaviours. After that there is usually the stage

the different professional and organisational cultures of the team members. If and when these conflicts are resolved, there is the stage of “norming”, when the members begin to trust each other, formulate shared goals and develop a common team culture. If this stage is successful, the team may reach the stage of performing, when the members are concentrating on

accomplishing their goals. Talbot and Verrinder (2005) describe also a fifth stage; the

mourning stage when the time has come to end the group this will also has an impact on the

team. In this stage is it important to evaluate the group’s achievements and deal with any unfinished business. Having some form of ritual ending may help the group to finalise its activities and members to acknowledge its ending.

To achieve high levels of synergy the collaborating teams must be able to recruit and retain partners who can provide needed resources. The voluntary nature of partner participation can make such recruitment and retention particularly challenging (Lasker, Weiss & Miller 2001). The literature on collaborating teams’ functioning suggest that it is important to assess the

heterogeneity and level of involvement of partners (Alter & Hage 1993; Kreuter, Lezin &

Young 2000; McKinney, Morrissey & Kaluzny 1993; Mitchell & Shortell 2000) The critical issue for collaborating teams’ seeking to achieve high levels of synergy is not the size or diversity of the teams, but whether the mix of partners and the way they participate are optimal for defining and achieving the common goals (Lasker, Weiss & Miller 2001). One of the factors that influence actor’s decisions about participating to cooperate with another actor is their perception of relative benefits and drawbacks involved (Alter & Hage 1993; Chinman et al. 1996). An actor’s level of involvement may depend on the authority that actors grant to their representatives. Individuals who represent actors in collaborating teams have multiple and competing demands placed on them. It is often difficult for these

individuals to devote the necessary time and energy to the work of the collaboration (Israel et al. 1998). Minimising the drawbacks arising from a partners’ participation in the collaboration may just be as effective as providing additional benefits (Chinman et al. 1996).

The ability to achieve high levels of synergy in a collaborating team is not only influenced by internal factors but also by factors in the external environment, which are beyond the ability of any cooperating team to control. Examples of external factors are public and organisational policy barriers which may make it difficult to achieve high levels of synergy (Lasker, Weiss & Miller 2001). Another external factor is how conducive the community is to the work of the collaboration (Goodman et al. 1998; Israel et al. 1998; Mattesich, Murray-Close & Monsey 2001; Roussos & Fawcett 2000). Many of the factors that influence health and health-related behaviour can be traced to the social structures and the wider social environment. People feel connected to their community and it is often possible to take action to improve health by working in community settings. It is therefore important in contemporary health promotion work to understand these social structures and how to engage and mobilise local communities (Davies & Macdowall 2006). People working with health promotion such as researchers and practitioners must also understand the community development process and apply that

information to help community-based groups achieve real successes (Butterfoss, Goodman & Wandersman 1996).

2.4 Community health promotion in Mozambique

Mozambique became independent in 1975 after nearly 500 years of Portuguese colonial government. The Africa Groups of Sweden1 reported that the new government with support from the Soviet Union, other Eastern countries and the Nordic countries put all their effort on building schools, hospitals and to educate teachers, doctors and nurses. They also adopted the PHC system which was advocated by WHO (Pavignani & Durão 1999). For the new

government education was a symbol for success. From 1972 when only one third of the children went to school the number increased to more than half of the children in 1979. But in the beginning of 1980s a civil war started and half of the schools were destroyed or had to close due to the war. The civil war ended in 1992 and in the beginning of 2000s almost half of the children were attending school, little fewer girls than boys.

In 2006 Mozambique had a population of nearly 20 million people. The World Bank2

considers it to be one of the poorest countries in the world due to a large number of social and economic challenges such us unemployment, low agricultural production and limited

infrastructure and social services. A huge problem in Mozambique is the big socioeconomic differences between the south and north parts of the country. Almost all financial activity is concentrated to the capital Maputo and the southern parts. Other difficulties are lack of

financial resources, high debts and complicated bureaucracy (Utrikespolitiska Institutet 2003). Despite its difficulties Mozambique has made substantial progress in improving human

development and in the fight against poverty. Statistics from the World Bank2 showed that from 1997 until 2003 had the per cent of population living below the poverty line declined with 16 per cent to 54 per cent with a little higher per cent in the rural areas than in urban. In 2004, 70 per cent of the population lived in rural areas. 2005 the World Bank3 reported that the foreign direct investment, net flows was 107.9 million US dollar and the official

development assistance and official aid 1.3 billion US dollar. The same year WHO4 reported that nearly 70 per cent of the total expenditure on health was financed by external resources. Pfeiffer (2003) meant that the inundation of the health sector by international NGOs since the late 1980s may have damage the PHC system. Rather than redistributing resources to promote greater equity and help alleviate poverty, the flood of NGOs and their expatriate personnel has fragmented the health system and contributed to intensifying social inequality in local communities with important consequences for PHC delivery. According to UNICEF5 less than 40 per cent of the population has access to basic health services, largely due to a shortage of trained medical personnel.

The National Health Service (NHS) in Mozambique has three levels of management: Ministry of Health, Provincial Directorates of Health and District Directorates of Health. The

management system is structured top-down: resources (personnel, drugs, equipment and funds) are allocated from one level to the level below. Each level enjoys considerable autonomy in using its own resources. The managerial culture within the NHS is mainly reactive. Decades of crises have shaped the management style, which can be likened to that of a sailor at the helm of a leaking boat, crossing stormy seas. The sailor is concerned with 1 http://www.afrikagrupperna.se/cgi-bin/afrika.cgi?d=s&w=1502 2007-08-09 2 http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/AFRICAEXT/MOZAMBIQUEEXTN/0,,menu PK:382142~pagePK:141132~piPK:141107~theSitePK:382131,00.html 2007-04-27 3 http://devdata.worldbank.org/external/CPProfile.asp?CCODE=MOZ&PTYPE=CP 2007-04-27 4 http://www.who.int/nha/country/MOZ-E.pdf 2007-04-27 5 http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/mozambique_2226.html 2007-08-13

keeping the boat afloat, and does not pay much attention to the choice of the harbour, provided it is safe. With this experience managers do not spend much energy in formulating long-term visions. Also the memory of the central planning failures still fresh makes

managers sceptical of plans. The perennial scarcity of accurate information has made managers reliant on experience, common sense and intuition, rather than on hard data. The top-down structure of the state administration and of the NHS inclines local officials to follow central directives rather than taking initiative (Pavignani & Durão 1999).

Pfeiffer (2003) found in his study from Mozambique that, when highly educated technicians from rich countries act in communities of extreme poverty, relationships of power and inequality may be enacted in ways that profoundly shape PHC policies and program.

Expatriate health workers employed by international agencies can be found at all levels of the health systems; from Ministry of Health offices in capital cities to remote villages where they are involved in health program implementation. In addition to their expatriate staff, agencies usually employ small armies of “nationals”, from trained health professionals and office workers to drivers and guards. Usually these workers are paid far more than their counterparts in the public sector. Chabal and Daloz (1999) argue that many locals among the elite sectors have learned how to manoeuvre in the NGO world of the new “civil society” for personal benefit.

The process of aid management has been incremental and innovative. Budget support is the most illustrative example of an open-ended process. Deliberately laid down vaguely at the beginning, it has provided to every involved partner, on both sides of the cooperation

relationship, a stimulating learning ground. The tension between keeping the services running and strengthening management systems has been resolved through progressive improvements, crises, detours and restarts. Pavignani and Durão (1999) believed that a more formal approach used in Mozambique can not be successful if some preconditions are not fulfilled. A strong political commitment is mandatory on the recipient’s side, so as to learn from mistakes and overcome hurdles. On the donor side, procedural flexibility, risk taking and a long-term perspective are crucial. A considerable degree of frankness is needed on both sides. Within the Mozambican context, informal arrangements may be more effective. The arrangements would have been more successful if they were kept flexible and forgiving at the beginning, and progressively made more challenging, demanding and structured as they grow and matured (Pavignani & Durão 1999). Dr Aida Libombo1, the Vice-Minister of Health, said at her lecture that today Mozambique is trying to improve the collaboration with NGOs through the contracting approach and using the sector wide approach as the way forward financial support. The strategic vision is to keep economic growth and to reduce poverty. Prioritised sectors are infrastructure, education and health. The main areas of cooperation are to educate health personnel, the provision of drugs and expansion of health services.

2.4.1 Health indicators

According to Aida Libombo1, the three main diseases in Mozambique are; malaria,

tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. UNICEF2 reported that more children in Mozambique die of malaria than of any other disease and this is one of the major reasons why the country has one of the highest child mortality rates in the world. For pregnant women malaria can be serious

1

Personal contact, 2007-04-28

2

due to the risk of severe anaemia which can be fatal. It can also lead to low birth weight of the child which is one of the most important factors in determining the child’s future survival. WHO1 reports that the prevalence of tuberculosis has decreased from 615 cases/100 000 people in 2003 to 596 cases/100 000 people in 2005. World Bank2 statistics shows that the prevalence of HIV/AIDS among 15-49 years old was year 2002 nationally 13.6 per cent. In 2005 the prevalence of HIV/AIDS had increased to 16 per cent. In Gaza province, where this study was performed, the under five mortality rate was lower than nationally in 2003, 156 compared to 178. The prevalence of HIV/AIDS among 15-49 years old in Gaza was 16.4 per cent in 2002 which was nearly 3 per cent higher than national. In the province 60 per cent of the population lived below the poverty line in 2003.

NGOs have been implementing projects to improve health promoting activities in rural communities in Mozambique for several years however it has been difficult to integrate activities of different actors. Therefore it is important to look into how the collaboration works.

2.4.2 The setting - Maciene

This study was carried out in Maciene, a rural village in the province of Gaza in south of Mozambique. It is located 30 km from the capital of the province, Xai-Xai, which is also the nearest city (Maciene Vision 2001). Around 1000 people live in the centre of Maciene. Together with the surrounding villages in the Maciene locality there are about 7 500 inhabitants. The number of inhabitants is increasing; however growth is slow due to a high amount of people moving out from the village. Most of the villagers’ live on farming, cattle raising and to extent fishing. Mostly women and children do the farming, while the men work in Xai-Xai, Maputo or in the mines in South Africa (Sigvardsson & Söderberg 2005).

Maciene is the Diocesan Centre of the Anglican Diocese of Lebombo in Mozambique and has been there for 100 years. In the beginning of the 20th century missionaries built the church, hospital and school which has been the centre of the community. Both the hospital and the school are parts of the official health respectively education system. 1994 the church proposed the Maciene Vision to local and international partners for their support. The Maciene Vision is an integral development plan for improving life in the village and evolved from the need of the people. The Vision focuses on growth of the people and the community in various aspects, spiritually, socially and economically. Since the beginning the main areas of the development plan has been agriculture, health and water (Maciene Vision 1999). Large efforts have been made on improving education; rebuilding school classrooms, building a new school house, building a Lay Training Centre, starting adult education, starting collaborating with

Mälardalen University. To enable this, collaboration between international, national and local partners has been initiated. To develop and keep the collaborating partners, exchanges are important (Maciene Vision 2001; 2002; 2004). The strategy is to educate people in aspects of leadership and capacity building in order to deal with the basic challenges of life (Maciene Vision 2004). 1 http://www.who.int/GlobalAtlas/predefinedReports/TB/PDF_Files/moz.pdf 2007-04-27 2 http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/AFRICAEXT/MOZAMBIQUEEXTN/0,,menu PK:382142~pagePK:141132~piPK:141107~theSitePK:382131,00.html 2007-04-27

3. AIM

The aim of this study is to describe collaboration among health promotion actors; health system, civil society and NGOs, in a low income setting - Maciene.

3.1 Survey questions

- Who are the health promoting actors in the setting? - What kind of collaboration exists?

- What are the experiences of collaboration among the actors? - How can collaboration be improved?

4. METHOD

4.1 Research approach

The thesis has a qualitative approach. It is a method well suited when you strive to explore and describe an overall picture of a special circumstance (Olsson & Sörensen 2007).

Qualitative research projects are undertaken to describe the context of a phenomenon and the activities that are of interest but also to discover new concepts, hypotheses and theories (Dahlgren, Emmelin & Winkvist 2004). For studies about interactions between actors involved in public health activities, qualitative research is one of the most used methods (Baum 1995). As the qualitative research is holistic and grounded in the context, multitude contextual factors must be taken into account. It also has an ontological view which means that reality is socially constructed and therefore multiple, and that subjective realities exist. The aim of qualitative studies is to discover the subjective realities of the informants in a specific context, not to uncover the objective truth of all human beings (Dahlgren, Emmelin & Winkvist 2004).

To do good qualitative research it is essential that the researcher has an open mind, ability to flexibly adjust to the unknown and awareness of her pre-understanding. Only the researcher can cope with the situation of changing demands, by being responsive, flexible, and adaptive and a good listener. Therefore the field student must be involved in every step of the research process from initiating the process through data collection and analysis to report writing. The personality of the researcher is important as well as the experiences of the research process (Dahlgren, Emmelin & Winkvist 2004).

In qualitative studies knowledge is generated in interaction between people. The field student and the study participants are part of an interaction, they are interrelated and inseparable. That means that the student and the informants will influence each other. This is not regarded as a problem or weakness; it is accepted as a part of reality that has to be taken into account, explored and learned from (Dahlgren, Emmelin & Winkvist 2004). As the field study took place in a foreign country the student had to work with an interpreter who also has an effect on the study (Edwards 1998; Kapborg & Berterö 2002). The field student tried to see how the

interaction affected both her self, the interpreter and the informants and utilised this knowledge in the data collection as well as in the analysis.

To learn about Maciene and to find actors working with health promoting activities the Maciene Vision (1999; 2001; 2002; 2003; 2004) and earlier thesis written by former students from Mälardalen’s University was to read (Ahl & Björklund 2004; Karevik & Svensson 2004; Sigvardsson & Söderberg 2005; Stenström & Tolf 2005). This resulted in the knowledge that apart from the local community, important actors were; the hospital and the Anglican Church. NGO’s that had health promoting activities were the Foundation for Development of the Community (FDC), a national organisation and World Vision, an international organisation. There was also a national program called Geração Biz where activists educate and inform adolescents in sexual and reproductive health with the focus on sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) including HIV/AIDS. Since the information on actors in Maciene was obtained through other studies, there was some uncertainty if all actors of interest for this study had been identified. Therefore the first survey question was to identify actors that had activity in Maciene during the students visit in the village.

4.2 Access to the field study

In 2002 the cooperation between the Anglican Diocese of Lebombo and Mälardalen

University started and the first students from Sweden visited Maciene for their field studies (Maciene Vision 2001; 2002). Father Carlos Matsinhe, Dean in the Anglican Church acted as a gatekeeper and supervisor in Mozambique (Burgess 1984). He also had approved the study before the field student arrived to Mozambique. In the preparatory phase in Sweden contact was taken by e-mail with FDC, World Vision and Pathfinder, one of the organisations involved in the Geração Biz program, and contact with informants on central level were established.

As the official language in Mozambique is Portuguese, in which the field student only had basic knowledge, working with an interpreter was necessary. In Maciene people speak Portuguese or their local language Shangaana. The interpreter was not a professional

interpreter but had knowledge in the three languages that was used; English, Portuguese and Shangaana. He was living in Maciene, working in the Anglican Church and therefore familiar with the village and its culture. He was also a well-established link to the local informants (Baker 1981). The interpreter met the field student and her co-worker when they arrived at the airport in Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, and introduced them to the country and its culture during the whole visit in Mozambique (Jentsch 1998). On the first Sunday after

entering the village the student and her co-worker were formally introduced in the community at a mass in the church, where they introduce themselves and informed of the purpose of their stay.

Soon after the field student’s arrival to Maciene a discussion was held with Carlos Matsinhe, where the student explained what positions the informants preferably should have in the different organisations. The strategy was to interview people from three different levels in the organisations; central level, supervisor level and on local level. The reason for doing these interviews at different levels was to see if the experiences and opinions of collaboration were the same. Carlos Matsinhe helped the field student to get in contact with the informants, either by writing recommendation letters or by calling them. Some of these people were of common interest for both the student and her co-worker in their studies and together with the

interpreter they went by the local bus to deliver the recommendation letters. At this point a deeper discussion was held with the interpreter to inform him about the aim of the study and the interviews and the interpreter’s role (Baker 1981; Murray & Wynne 2001; Phelan & Parkman 1995). The student had to consider what impact the interpreter might have at the interviews and how it may affect the validity of the study (Kapborg & Berterö 2002). The interpreter also knew some people that could be important informants and contacted them to set up meetings.

4.3 Procedure for data collection

The field study was carried out during a nearly six week long visit in Mozambique with four weeks in Maciene. One of the first days in Maputo a short meeting with Carlos Matsinhe occurred and an appointment with an informant at FDC on central level was made. Unfortunately this meeting had to be cancelled since the informant got sick in malaria. Decision was made that a new meeting would take place when the field student returned to Maputo after her visit in Maciene.

A semi-structured interview guide had been prepared in Sweden and the supervisor at Mälardalen’s University read the interview guide. After arrival to Maciene Carlos Matsinhe also read the interview guide without comments. Two pilot interviews were conducted in Maputo which was not included in the study (Kvale 1997). However the interview guide needed to be revised. The question about communication within the informant’s organisation was excluded. The reason for this was that the student had experienced that this question was a bit sensitive and was uncertain if the informants would answer truthfully as they might not want to criticise their organisation/project. A question about, if any improvements had been seen, was added after the first four interviews (Appendix I, II).

For this study sixteen interviews were carried out from six different actors/program; Maciene community, the National Health service, the Anglican Church, FDC, World Vision and Geração Biz. Six interviews were on central level, five on supervisor level and five on local level. There was one more interview planned on local level but the informant never showed up and new appointment was never arranged. Eight of the interviews were conducted in Maciene of which six were conducted at the informants’ offices, one in the informant’s home and one in the Anglican Church’s guesthouse where the field student lived. Interviews were also made in communities nearby Maciene; three in Xai-Xai, one in Chicumbane and one in Chongoene. Three interviews were also carried out in Maputo after the visit in Maciene. These six last mentioned interviews were all held at the informants’ offices.

Fifteen of the sixteen interviews were tape-recorded. At the 16th the informant did not allow the field student to tape-record, instead notes were taken during the interview and some information might therefore have been lost or misinterpreted. Eight of the interviews were held together with the interpreter as the informants did not speak English, only Portuguese and/or their local language Shangaana. The remaining eight interviews were held in English by the field student herself (four) or together with her co-worker (four). At two of these interviews the interpreter was present in case his knowledge in the languages was needed. Times for the interviews were between 19 minutes and 1 hour and 10 minutes. The field student also took reflexive notes of her impressions and thoughts throughout the research process. These notes were utilised in the data collection as well as in the analysis (Dahlgren, Emmelin & Winkvist 2004).

4.4 Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed by the field student herself as close in time to the interview as possible and the 15 tape-recorded interviews resulted in 95 A4 pages of text. The 16th interview, where notes were taken, was also typed. In total there were 97 A4 pages transcribed text.

To analyse the collected data content analysis was used. It is a “research technique for

making replicable and valid interferences from text (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use” (Krippendorff 2004 p.18). When analysing a text there will always be

some degree of interpretation and the researcher’s interpretation is influenced by her personal history (Graneheim & Lundman 2004). The transcript text was read through several times to obtain a sense of the whole (Graneheim & Lundman 2004) with the aim of the study close in mind. One by one the interviews were analysed by starting with preliminary themes (Downe-Wamboldt 1992) related to the interview questions. Then a total of 149 meaning units were elected with differences between 2 and 28 meaning units from each informant. These meaning units were first condensed and then coded. The various codes were then compared based on differences and similarities and sorted into categories. The categories were then sorted into the preliminary themes (Appendix III, IV). During the whole analysis process the students focus has moved from themes to meaning units and then back to themes again (Graneheim & Lundman 2004).

4.5 Ethical principles and considerations

When doing research there are several ethical aspects that the researcher needs to have in mind. According to The Swedish Council for Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences (2002) four general principles are very important in every research project; information demand, consent demand, confidential demand and demand of use and rights. Since the student did not book all interviews herself, each respondent was informed by the field student about the study and that it was voluntary to participate before the interview. All the

informants gave verbal consent. They were also assured and informed that the information given during the interview was handled according to the principle of confidentiality. The collected material was kept at the home of the field student were no one else had access to it. To remain confidential at the quotations, numbers has been used to distinguish the informants. All participants were assured that the material collected during the field study in Maciene was used for a master paper in Public Health Science and only for this purpose.

5. RESULTS

The result will be described in four parts. The first part presents the health promoting actors/program in the village. The second part describes different ways of collaboration that occur. The third part describes the informant’s experiences of cooperation and the fourth part the informant’s opinion about how collaboration can be improved.

5.1 Health promotion actors in Maciene

Maciene community is divided in four areas; Maciene, Cumbene, Ngangalene and Marramine.

The community is governed through a council consisting of 30 people. Five of these form the executive council and are permanent members; one of them is the president of the locality. The executive council develop a plan which they discuss with the rest of the council members and then with the locality. Each area has a person that brings and represents the people’s opinion in his or her area. The plans are based on the people’s opinions. If something can not be solved within the areas the president of the community can help out. The local politics are depending of the people’s opinions and ideas. According to the president of the community people participate a lot but only about 20 per cent of the people know what democracy is. One of the main reasons for this is that Maciene is a village with only a few higher educated people. People’s volition to stay in Maciene and to be a part of the village is important but people see a problem in lack of job opportunities after finishing school. Many feel that this is the reason for moving away from Maciene or just sitting in their homes doing nothing. Most of the locals would like to participate in changing their life situation and in developing Maciene rather than being forced to move. There was also a strong feeling for the local community rather than on the individual (Ahl & Björklund 2004). The community supports the Maciene Vision through voluntary work mostly done by women in caring aspects (Maciene Vision 2004).

The hospital is considered to be a Health Centre, which is the lowest level of health care in

Mozambique (Gaza Provincial Directorate of Health 2005). About 3.500 patients attend the hospital every month. The hospital provides aid to sick people, family planning and health prevention work, such as vaccinations (Maciene Vision 1999; 2001). It has 35 beds, a

delivery ward and a small laboratory. Nowadays the hospital also has water, electricity and a refrigerator. The staffs’ level of education is divided in four levels (superior, medium, basic and elementary level). The hospital in Maciene has one person at medium level, three at basic level and three at elementary level (Gaza Provincial Directorate of Health 2005). The hospital was damaged during the civil war however it was repaired and re-equipped in the beginning of 1990s in order to provide improved and effective service. In the surrounding rural areas there are Health Posts which provide basic services such as malaria treatment. Patients who can not be treated at a Health Post are referred to the hospital in Maciene (Maciene Vision 1999).

The development is moving fast and the Anglican Church regards themselves to have a crucial role through their pastoral, spiritual and teaching vocation. They regard they can help by educating and stimulating people to respond and participate in the development process which affect their lives (Maciene Vision 1999). The church also plays an important role in the fight against lack of education among its members. 95 per cent of the population is Anglicans and many of them have no other opportunities for education than through church, where they receive informal education. At every mass the priest spends time to educate by discussing one