J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O L JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSIT YR e c o g n i z i n g t h e F a i l i n g L a y e r s

o f I n t e r n a t i o n a l I n s t i t u t i o n s

d u r i n g t h e G e n o c i d e s i n

R w a n d a

Bachelor Thesis within Political Science Author: Henric Arnoldsson

Tutor: Benny Hjern, Mikael Sandberg Jönköping June 2009

Abstract

This thesis aims at finding the reasons for the genocide in Rwanda, not only in the history of the country, but also the reason why the international institutions failed to prevent it. The thesis begins with a historical background of Rwanda where key actors in the conflict are presented and in the end presents an explanatory model which is based upon the facts gathered during the thesis. The model aims at explaining why the genocide happened and it is built up of layers. These layers have their background in Rwanda’s history and also international institutions, such as the UN. The layers of importance which led to the genocide are: Rwanda’s colonial past, the Arusha Accords and the mandate of UNAMIR (failure of the United Nations), a uni-polar world, increasing poverty, and the assassination of President Habyarimana. There were few available strategies in the standard arsenal of international political means that could have been used to stop the genocide, both before it broke out, but especially after it had begun.

Key WordsRwanda, Genocide, UN, Peacekeeping, RPF.

Abstrakt

Uppsatsen ämnar hitta de bakomliggande orsaker till folkmordet, inte bara i Rwandas historia men också varför internationella instutitioner, så som FN, inte bidrog till att förhindra folkmorden. I det fortlöpande arbetet med uppsatsen har en modell utvecklats vilken ämnar förklara vad som hände, och som är byggd på den information som framkommit under arbetets gång. Modellen bygger på ett flertal lager av händelser. Dessa lager bygger på händelser som inte bara rör Rwandas historia utan också på vad de internationella institutionerna bidrog med i konflikten. De identifierade lagren som ligger till grund för konflikten är Rwandas koloniala bakgrund, Arusha Accords och mandatet för UNAMIR, en unipolär värld, ökande fattigdom samt mordet på President Habyarimana. Det fanns få tillgängliga politiska strategier som kunde ha använts för att stoppa folkmordet.

Table of Contents

1

Problem ... 4

1.1 Aim ... 4 1.1.1 Questions... 4 1.2 Method ... 5 1.3 Limitations... 52

Previous Research ... 6

2.1 Review of the Sources ... 7

2.1.1 Linda Melvern ... 7 2.1.2 Alan J. Kuperman ... 7 2.1.3 Roméo Dallaire ... 7 2.1.4 John A. Ausink ... 8 2.2 Summary ... 8

3

Presentation of Rwanda ... 9

3.1 History of Rwanda ... 9 3.2 Population Growth ... 10 3.3 Economic Regression ... 11 3.4 Summary ... 124

Key Actors ... 13

4.1 Rwandan Patriotic Front ... 13

4.2 The United Nations ... 14

4.2.1 1948 UN Resolution 260 on Genocide ... 14

4.3 France ... 15

4.4 The United States of America ... 16

4.4.1 The Presidential Decision Directive ... 16

4.5 Belgium ... 17

4.6 Summary ... 18

5

The Escalating Conflict, 1990 to 1993 ... 19

5.1 United Nations Observer Mission Uganda Rwanda- UNOMUR... 19

5.2 The Arusha Accords ... 19

5.3 United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda - UNAMIR ... 21

5.4 The Death of President Habyarimana – the Final Strike? ... 22

5.5 UNAMIR II... 23

5.6 Operation Turquoise ... 23

5.6.1 The Delusion of Impartial Intervention – A Response to Operation Turquoise ... 24

5.7 End of the Genocide ... 25

6

Reasons for the Genocide – Failing layers? ... 26

6.1 Rwanda’s Colonial Past ... 26

6.2 Arusha Accords & the Mandate of UNAMIR - the Failure of the United Nations ... 26

7

Classical Interventions ... 29

7.1 The False Promise of International Institutions ... 30

8

Different Levels ... 31

8.1 Conceptualizing Failing Layers ... 32

9

Concluding Discussion ... 34

1

Problem

Rwanda, a former German and Belgian colony, has a history of violence. Since independence there has been fighting between the two ethnic groups Hutus and Tutsis. Tutsis were the former supreme group who were in power before colonial rule and the Hutus were the suppressed. Ever since independence, the Hutu majority has been seeking revenge for what the Tutsis exposed the Hutus to. Many of the conflicts have been blown up in proportion by the Belgian colonial power and seem to be difficult for a westerner to relate. What has to be understood is that Rwanda has been a country where tribal traditions, especially for ruling, have been widely used. This is one of the reasons why the conflicts escalated to a civil war and later became denoted as genocide.

During the second half of the 1980’s, Rwanda experienced rapid economic growth. Their main export, coffee, was at peak prices in 1988. After a decision made by the leading coffee producing countries that prices should be floating (determined by demand prices), the price fell rapidly. From their independence in 1962 until late 1980’s, Rwanda was seen as a success with a steady growing economy and relatively low inflation. However, the population was also continuing to grow at a steady pace. Rwanda was being caught in a downward sloping spiral with decreasing income from exports, and internal fracturalizations lead to disturbances within the country.

There is not just one single cause that eventually leads up to genocide. The world order with its layers of institutions, both national and supranational, has been designed to prevent happenings such as those in Rwanda in the mid 1990s from actually taking place. One example is resolution 260 from 1948 “Prevention and punishment of the crime of genocide” (UN, 1948). The whole conflict in Rwanda is of such complexity that an explanatory model would be useful when analyzing the conflict.

The question of finding out how this could happen and why it happened is of great importance since ethnic related conflicts and wars are considered the biggest threat to global security since the end of the cold war (Hettne, 1996).

1.1 Aim

The aim is to recognize the failing layers; what are they and what made them fail. Further, it is necessary to determine if they were critical, and explain this to the reader in a way that is easy to understand, inducing greater interest for similar events. The aim is also to create an explanatory, or a concept evolving, model which would help to explain the complex situations leading up to genocide.

1.1.1 Questions

The questions this essay aims to answer are • What lead up to the conflict?

• What are the “SafetyNets”?

• Who were the key-actors in the conflict? • What were the decisive turningpoints?

• Which of the classical policy interventions would have been appropriate and what would their

These questions are of importance in both explaining what happened and why the genocide took place. The most important point is that the raised questions will provide an answer to how this could happen despite the rapid increase in amount and scope of international institutions aiming at preventing war and promote peace and stability.

1.2 Method

In order to answer the aforementioned questions, a qualitative analysis of sources will be the most useful. This paper will investigate the conflict in Rwanda in order to identify the key actors in the international and supranational arena and find out what circumstances prevented their intervention.

The author has to accept that his interpretations of the literature are influenced by his prior knowledge. An individual can never guarantee that their observations are infallible objec-tive views of reality. However, by using a larger selection of literature carefully investigated and weighted in terms of reliability, political independence, and concurrency should never-theless provide significance to the results of this thesis. Some of the literature will be pre-sented in Section 2, Previous Research. The use of primary sources is unavailable to the au-thor at the point in time of writing this thesis, so most of the literature used is secondary, and on some occasions, tertiary.

An explanatory model will be developed which aims at explaining the conflict in an accessible manner. The model explains how the situation in Rwanda could get so bad, despite the presence of institutional safety nets.

1.3 Limitations

This is not a thesis that is focused at describing the actual genocide itself, but is rather meant to be limited to the questions raised. A big part of the thesis will still describe the genocide and the preparations for the genocide since it is crucial to have this information in order to explain the failures; that is, to be able to know ‘why’ one has to understand ‘what’ (what happened).

The limitations will also include the choice of literature. There are hundreds of titles written on the topic of the genocides in Rwanda, but due to the time constraint in which the thesis is to be written it is impossible to filter through all available material. Therefore an appropriate selection has been made by the author which is likely to provide suitable materials for answering the questions raised.

2

Previous Research

There have been several books and reports written on the subject of the genocide in Rwanda. The majority of them are meant to describe the events, focusing on the humanitarian distress. Below, some of the books and papers that will serve as sources for this thesis are introduced.

Former Secretary-General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan, asked for a review of the actions undertaken during the conflict. The independent inquiry was given unrestricted access to all UN documents and persons involved. The inquiry was asked to find the key events and to evaluate their relevance to the implementations of the genocide. The final report was named “Report of the Independent Inquiry into the actions of the United Nations during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda”, written by former Prime Minister of Sweden Ingvar Carlsson, former Foreign Minister of the Republic of Korea Han Sung-Joo, and Lieutenant General Rufus Kupolati (1999). The report published was harsh against the UN and blamed the UN for having major responsibility in what happened. This work is mainly focused on answering the question ‘what’ happened. This report will be given a very important role in the thesis due to its critical reflection on the responsibility of the UN. Another seminal work is the book “A people betrayed – The Role of the West in Rwanda’s Genocide” by L. R. Melvern (2007). This book focuses on what happened and the failure to prevent it.

“The Limits of Humanitarian Intervention – Genocide in Rwanda” by Alan J. Kuperman (2007) is a book that deals mostly with questions such as ‘What could have been done’? He puts forward possible interventions and goes through numerous scenarios that could have been employed to prevent the genocide, or that could have stopped the genocide once it had begun.

The perhaps most read book on the genocides in Rwanda is Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire’s book ”Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda” (2003). This book is a biography, written by Dallaire himself, describing the events from his point of view. He was the commander of the UNAMIR forces which were the peacekeeping force in Rwanda as the genocides took place. His observations describe the history and assists in finding the key actors and the key events which lead up to the outbreak of the genocide.

Another text used in this thesis is “Watershed in Rwanda: The Evolution of President Clinton’s Humanitarian Intervention Policy” by John A. Ausink (1996). This text is focused to a large extent on the US’s non-intervention and what was going on in the US at that time.

Other than the literature listed above, there have been numerous other books and papers written on the subject that have been used for this thesis. The author is confident in using these sources since the majority has been backed up by UN sources and other well-reputed authors on the subject. Additionally, a more thorough analysis of the main authors will followin section 2.1.

2.1 Review of the Sources

This thesis is based on information gathered from the books mentioned above. Therefore these books, as well as their authors, deserve to be analyzed in further detail in order to avoid bias and misleading interpretations of events.

If you take four people with different education and different occupation they will have four different views explaining what they have seen although they have all been at the same place, at the same time. For example, if a Lieutenant in the military, a painter, a forester, and a bird watcher would all be taken into the woods at the same time, they would most certainly give four different evaluations of the terrain. The Lieutenant would perhaps see natural shelters from attacks, the painter would describe the colors, the forester the state of the trees and the bird watcher which types of birds he would estimate as inhabitants in the area. The beauty of this is that they are all right in their judgments and they are all equally important. However, if one is to write a thesis on the specific area these four people visited, one has to be aware of that the descriptions might be colored by one’s own background and ideas. True indeed there might be birds in the trees, but watch where you step or you might fall in one of the natural bunker-like holes.

In order to take into consideration the above, the author has chosen to present some of the authors of the main texts considered when writing this thesis.

2.1.1 Linda Melvern

Linda Melvern is an investigative journalist with a past on the British newspaper “Sunday Times”. She is an Honorary Professor at the University of Wales in the Department of International Politics. She has been a consultant involved with the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. Her books can be found on the UN website as suggested reading for those interested of the Rwandan genocide and therefore is seen as a trustworthy source. Her book is based on interviews and thereby primary sources.

2.1.2 Alan J. Kuperman

At the time of writing the book used in this thesis Kuperman was Resident Assistant Professor of International Relations at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) in Bologna, Italy (University of Texas at Austin, 2009). Tendencies in his work as being very “black or white” are identified in some sections and somewhat favoring military intervention. He teaches courses in Military Strategy and in his book “The Limits of Humanitarian Intervention – Genocide in Rwanda” (2007) he puts a lot of focus describing the military equipment, military capabilities; the whole book is very influenced by, and focused on, military questions. The book is mainly based on the author reviewing official documents and to some chapters direct interviews have been made. This does not mean that it cannot be used as a reliable source for the thesis but that one has to be aware of possible biases. This can be somewhat eliminated by using cross-references.

2.1.3 Roméo Dallaire

Roméo Dallaire who was the Commander of the UN lead forces in Rwanda has written a book called “Shake Hands with the Devil” which is an autobiography of his time in Rwanda. Since he has suffered a lot from his experiences, and has put a lot of blame on himself for the killings, this might affect his story. His background within the military will color his view on the conflict and he will of course, subconsciously, tell the story from a military point of view to some extent. He has been very critical of the way the UN acted

during the crisis. Regardless if wrong or right, his story may have too much of a focus on the UN and leave out other factors. This book would be referred to as a primary source. The information in this book has been used in order to grasp the whole picture and not used so much for precise information since there may be a lot of Dallair's own thoughts and ideas in the story.

2.1.4 John A. Ausink

Ausink has written a number of books in the field of military strategy and especially within the US Air Force. His text “Watershed in Rwanda: the Evolution of President Clinton’s Humanitarian Intervention Policy” (1996) is used as case study material at the Institute for the Study of Diplomacy at the Georgetown University, Washington DC. Ausink give important knowledge and information about the US decisions and perspective on the situation. That a university uses it as case study material adds to the reliability of the book for use in this thesis although the possibility still exists that the story may include some angled observations. His text is a mixture of secondary and tertiary sources.

2.2

Summary

Considering the very different backgrounds of the authors and their different focuses on describing the events which took place, a broad knowledge base has been created for this thesis. Through the different aspects of the conflict and the use of cross referencing, the risk of factual errors is minimized. The authors are also well known and have prior published works which have been considered authentic. In conclusion, using these sources as part of the research for this thesis will provide significance and validity to the results of this thesis.

3

Presentation of Rwanda

This section will give an introduction to Rwanda. It will cover the historical background in order to examine the root causes of the conflict, the population growth as an important indicator, and Rwanda’s economic situation. This section will lay the foundation upon which the explanatory model will be based.

3.1 History of Rwanda

Rwanda, located in the heart of Africa, is a small landlocked country with a size equivalent to the state of Maryland, USA. Before the brutal civil war broke out it was one of the most densely populated countries in Africa with a population of 7,5 million people, that is 405 people per accessible square kilometer. The country is divided into north and south, each representing one of the two major ethnic populations, the Hutu population in the north and the Tutsis in the south. There is also a third minority population which is the Twa, representing less than one per cent of the total population (Ausink, 1996; Stettenheim, 2002).

The history of Rwanda as a unified country stretches back to 1860 when the Tutsi King Rwabugiri expanded his power and created a centralized state. In 1880, the first European explorers arrived in Rwanda and in 1899 Germany began its colonial rule over Rwanda and incorporated the country into the Deutsche Ostafrika. In 1916, Belgium took over as a colonial power in Rwanda under a mandate by the League of Nations (Ausink, 1996). The Belgians imposed indirect rule through Tutsis which was seen as a superior group over the Hutus (Ausink, 1996). The Belgians and the Germans “usurped the royal governing structure of Rwanda and ruled indirectly through the Tutsi” (Stettenheim 2002: 219). This was of course a serious assault on the Rwandan culture in which they gave monopoly of power to the Tutsi’s which was later to prove fatal.

The Hutu population lost their right to education and also the possibility to become Tutsi’s. Before colonial rule it was possible to climb the social latter from Hutu to Tutsi and vice versa. If a Hutu became wealthy he could become a Tutsi and if a Tutsi lost his wealth he became Hutu. The two ethnic groups were created through the colonial rule and were formerly more of social structure than ethnicity. It is first after the Belgians intervened in this social hierarchal system by forbidding marriage between the two groups that an ethnical difference occurred. In 1933, the Belgian colonial administrators insisted on issuing identity cards with the ethnical background and did so along with a number of other reforms which further increased the distance between the Hutus and Tutsis (Stettenheim, 2002). In the cases where there was doubt about a person’s ethnical background one simply stated that “a man owning ten or more cattle was classified Tutsi” (Ausink, 1996:2). The ethnical discrimination raised tensions between the Tutsi’s and Hutu’s and this would prove as an important source to the conflicts in the 1990’s.

In the 1950’s the UN pressured Belgium to prepare Rwanda for independence. The Belgians switched strategies, going from a policy of supporting the Tutsi population to supporting a power-sharing structure between the Hutus and the Tutsis (Ausink, 1996). The Hutus saw the benefit of this while the Tutsis felt betrayed and left aside, but the Hutus also felt that it was going too slow. In 1959, the Tutsi King, Mutura, died and in the confusion that followed violence broke out between the Tutsi and Hutu population. “The Belgians intervened and replaced about half of the Tutsi chiefs in leadership posts with Hutus” (Ausink, 1996:2). Then further, “from 1959 until 1962, when Rwanda and Burundi became separate, independent states, the idea that the Tutsis were ‘foreign minority’ who, according to the myth, were ‘tall and willowy’ people who had swooped down from the

north to ‘enslave the Hutu’, was key ideological ingredient justifying the Hutu revolutionary movement” (Ausink, 1996:2). In this revolution, which the Hutus had initiated, several thousand of Tutsis fled to neighboring countries. When Rwanda finally became independent from Belgium in 1962, organized harassments of the Tutsi population began (Ausink, 1996).

Joel Stettenheim describes in his work “The Arusha Accords and the Failure of International Intervention in Rwanda” (2002) that the aforementioned occurrences were very important events that would lead up to the genocides in 1994. He states, “In the late 1950s, the struggle for power had become defined in ethnic terms” (Stettenheim 2002:220). This is a very important and strong statement that Stettenheim brings up as this indicates that the Belgian separation and differentiation between Hutus and Tutsis had actually succeeded, at least as they intended, in creating ethnical differences.

In the years following Rwanda’s independence, hundreds of thousands Tutsis fled north to Burundi and Hutus fled from Burundi to Rwanda (Stettenheim, 2002, Ausink, 1996). “Repression of Tutsi during this period, including a massacre that killed 5,000 to 8,000, led to a massive exodus of refugees into Burundi, Zaire, Tanzania, and Uganda. Violence in Rwanda continued against the Tutsi, particularly in 1963-65 and 1973, and lead to successive waves of exodus. By 1990 the refugee population, including their descendants, numbered almost 600,000” (Stettenheim 2002:220).

In 1973 history took another turn in Rwanda as General Juvenal Habyarimana seized power through a coup. Habyarimana was of Hutu origin and established a government which only allowed political participation by the Republican Movement for Democracy and Development, MRND (Ausink, 1996). Habyarimana soon created his own inner circle of power and “by the mid 1980s, members of Habyarimana’s Bagogwe clan held 80 percent of the top military posts…” (Stettenheim, 2002). The former suppressed became the suppressor and created an apartheid like system.

During the initial stage of Habyarimana’s rule, Rwanda had relatively steady economic development and during the 1980s the World Bank considered Rwanda as a relative success in the region. In 1987, Rwanda had one of the lowest debts in Africa (Stettenheim, 2002). The success of Habyarmana’s rule eased some of the tensions between Hutus and Tutsis. During the period from 1980 to 1990, no major ethnic violence had occurred and Habyarimana also became favored by some of the Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

Rwanda had experienced positive development although it was not a straight line, but at least it showed tendencies for success. What the history of Rwanda proves is that there had been internal tensions within the country for many years which had not ended for good.

3.2 Population Growth

In 1950 the population in Rwanda reached 2,4 million people, and in 1993 the population had increased to 7,5 million inhabitants which is an increase by over 300 percent (Earth Policy Institute). The more people that have to survive on the same land area, putting increased stress on natural resources such as fresh water, is according to Hettne (1996) an underlying reason for ethnic conflicts. Increased competition for resources effectively undermined the stability in Rwanda. The pre-genocide population density was 405 people per square kilometers which was the highest density in Africa. The most densely populated region, Rhuengeri, had a population density of 820 people per square kilometer

Stettenheim has used a quotation by Gerard Prunier, a French author specializing in East Africa, which is brute, but somehowspeaks for what has been argued above:

“The decision to kill was of course made by politicians, for practical reasons. But at least part of the reason why it was carried out so thoroughly by the ordinary rank-and-file peasant ... was the feeling that there were too many people on too little land, and that with a reduction in their numbers, there would be more for the survivors.” (Gerard Prunier as cited by Stettenheim, 2002: 217)

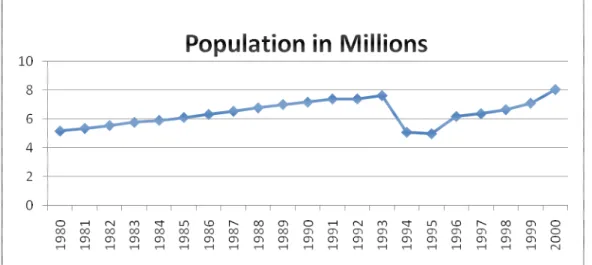

In the graph above a steady increase in population size can be seen. In 1980 there were about 5.2 million people in Rwanda; in 1990 there were about 7.2 million people. That would call for a population growth in real terms of 2 million people in 10 years. This would mean that 7.2 million people would share the same space as the state of Maryland in the US or the county of Dalarna in Sweden.

3.3 Economic Regression

Prior to 1980 the government of Rwanda was considered a success in economic management. Between 1965 and 1989 GDP increased by nearly five percent per year. Along with a steady economic growth they also managed to keep inflation low, at roughly 3.7 per cent per year although they had a large population growth (Meredith, 2005). They were still to be considered as poor although they had positive progress. Rwanda’s economy was highly dependent on coffee production and the export of coffee represented 75% of the total export earnings (Melvern, 2007). In the 1980’s the prices fell due to the collapse of the International Coffee Agreement, ICA, because of pressure from Washington who acted on behalf of the US coffee producers. The breakdown of the ICA affected Rwanda and the economy fell apart with it. From 1989 to 1993 the average GDP per capita fell with 40 percent (Stettenheim, 2002). Rwanda also had a growing tourism industry famous for its gorillas, which brought in foreign currency into the country. According to Stettenheim (2002) the impact of the increasing conflicts in Rwanda was fourfold; first it displaced people reducing productivity and increased demand on governments recourses; second the RPF, Rwandan Patriotic Front (will be explained in further detail in section 4.1) cut off the main export route of coffee; third, the tourism industry was destroyed; and fourth, the increase in military related expenses came to dominate government expenditures. All this plus the fact that the IMF and the World Bank demanded structural adjustments for their previous loans to Rwanda, hit to a great extent the Rwandan peasants.

Figure2: Rwandan GDP per Capita in USD. Source: IMF, 2009

As can be seen from the graph above, Rwanda sawa significant increase in GDP per capita during the 1980’s. In the beginnings of the 1990s, as the fighting between the RPF forces and government troops increased, there was a rapid decline in the GDP per capita. Already in the late 1980’s there was a slight decrease which was due to falling world coffee prices. This had a spinoff effect which together with the escalating war led to the massive decrease in the beginning of the 1990’s. Thus, the entire blame of falling GDP per capita cannot only be due to the conflict between RPF and the government. The cause of the steady increase in GDP per capita between 1984 and 1989 stems not only from the coffee exports. Rwanda had, as mentioned before, a growing tourism industry with increasing popularity. Rwanda also received a lot of foreign aid. Belgium, the former colonial power, was the largest donor, Switzerland had Rwanda on the top of their aid list, and France helped with military training and technology. “Foreign aid constituted an increasing proportion of national income, rising from 5 percent in 1973 to 22 per cent in 1991” (Meredith, 2005:486).

3.4 Summary

Rwanda has had a shaky history. The Belgians imposed an apartheid-like system which spurred conflicts. Hostilities between Hutus and Tutsis increased when Rwanda gained independence in 1962. Already in the late 1950’s the struggle for power had been defined in ethnic terms. In 1973, General Juvenal Habyarimana seized power through a coup. Habyarimana created an all-Hutu government with members of his own clan holding up to 80% of the top military posts. Rwanda saw some initial progress in economical development. In the late 1980’s the International Coffee Agreement fell apart. This harmed the Rwandan economy severely since 75% of the total export earnings stemmed from coffee production. Additionally, from 1980 to 1990, Rwanda saw an increase in population in real terms of 2 million people making Rwanda the most densely populated area in Africa.

4

Key Actors

Before explaining the escalating conflict in the beginning of the 1990’s, this section will introduce the key actors in the Rwandan conflict: the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), the UN, France, USA, and Belgium. This description will include the leaders, the main interests, and constraints of the key actors.

4.1 Rwandan Patriotic Front

The RPF originates back to 1979 as the movement Rwanadese Alliance for National Unity (RANU), was first organized. RANU was initially a refugee organization for Rwandan refugees in Uganda. In 1987, RANU changed its name to Rwandan Patriotic Front, RPF and at this time the organization changed course towards becoming a military guerilla movement.

Many of the RPF members had been involved in fighting against Idi Amin and Milton Obote (Stettenheim, 2002), both of them former dictators in Uganda, and were well equipped and well trained and very motivated. One of the big advantages they had in their organization against the government forces was their discipline, organization and motivation.

The RPFs “purpose, they said, was not only to promote the return of Tutsis, by force if necessary, but to support the wider cause of political reform in Rwanda. It sought neither to re-impose Tutsi rule in Rwanda nor to reinstate the Tutsi monarchy but to overthrow a bankrupt regime and establish a democratic government” (Meredith, 2005:492).

The RPF consisted not only of first generation Tutsi refugees but also of children and grandchildren of Tutsis who had fled in the late 1950s as the first harassments of Tutsis began. In September 1990, 4,000 Tutsis deserted the Ugandan army, took weapons and equipment with them and started their first invasion into northern Rwanda. The operation was a fiasco and on the second day their leader at the time, Rwigyema, was killed leaving the soldiers shocked and demoralized (Meredith, 2005). “Since retreating to the Virunga Mountains, the RPF regrouped under a new leader, Paul Kagame. At the time of the 1990 invasion, Kagame, a major in the Ugandan army, had been attending a military training course at Fort Leavenworth in the United States. On his return to Uganda, he had quit the army to join the rebels. By the end of 1991 he had managed to turn the RPF into a disciplined guerilla force of 5,000 men” (Meredith, 2005:496).

The guerilla warfare that the RPF used to do hit-and-run raids in northern Rwanda made them unpopular among the Rwandans and due to international pressure a ceasefire was signed between the RPF and Habyarimana’s government forces in April 1992 (Ausink, 1996). The international pressure on the two parties made them participate in peace talks in Arusha in Tanzania, which both parties agreed to. The peace talks began in July 1992 and came to be known as the Arusha Agreements or the Arusha Accords (Meredith, 2005).

4.2 The United Nations

Secretary-General for the United Nations was at the time Boutros Boutros-Ghali. Between 1993 and 1996 Kofi Annan, later to become the new Secretary-General of the UN, was the head of international operations. These two are the main characters representing the UN head quarters.

The UN was going through a time of financial crisis and there was an enormous demand for funding and troops in particular Somalia and Bosnia (Carlsson, Han &Kupolati, 1999). By 1993, the UN had twelve peacekeeping missions around the world, and they accounted for thirty per cent of the world’s total amount of peacekeeping missions (Melvern, 2003). Their main interest was to prevent the killing and being able to establish a lasting peace, not only in Rwanda, but also in the surrounding areas. The huge amount of Rwandan refugees also created instability in the bordering countries treathening the stability in the entire Great Lake Region. Their opinion on what would create long-lasting peace in Rwanda, and stability in the Great Lake Region, was the implementation of the Arusha Accords.

Their main constraints were their involvement in other regions and crises as well as the fact that they were going through rough financial times. The UN also does not have any of its own troops, but rather has to rely on troops from its member states. The decisions made are only of a recommendative nature, which often leads to slow and weak implementation. Adding to this, Rwanda was one of the members in the Security Council in 1994 and 1995 which made it difficult to pass any resolutions concerning Rwanda.

A resolution was passed in the Security Council on June 22nd1993 and called Resolution

846, which had been requested by the Governments of Uganda and Rwanda. The request was a UN led mission to prevent military backing to reach RPF from the Ugandan border (Simma, 2002).

The UN had intervened very successfully in the first Gulf war in 1990 and 34 countries joined up under the UN flag and successfully freed Kuwait from the Iraqi occupation forces. The ‘dark times’ of the UN were over and many people had faith in the belief that the UN now had a future. The UN had previously been locked by the bad relations between the Soviet Union and the US, but since the fall of the iron curtain many saw the opportunity for a reformation. “Less than two years before Rwanda exploded, the Clinton Administration’s new foreign policy team entered office in early 1993 with high hopes for reviving the UN as a major institution for world peace. Sympathetic to UN Secretary Boutros-Ghali’s 1992 call for the creation of a standing UN peacekeeping force” this could have become a great leap forward in the authority of the UN, but the US policy would soon change (Ausink, 1996:4).

4.2.1 1948 UN Resolution 260 on Genocide

The goal of the UN General Assembly was to create an international law which would prevent genocide. Although the genocides during the Second World War are perhaps the most famous example, there have been other genocides during the 20thcentury such as the

Turkish genocide on Armenians 1915, and the Red Khmer genocide in Cambodia. The work began already in 1946 as the General Assembly declared that genocide is a crime under international law and violates the values of the United Nations, which was declared

The definition of genocide is any acts with the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group as such” (UN, Resolution 260 article 2). “Namely:

1. Killing members of the group.

2. Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group.

3. Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.

4. Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.

5. Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.” (Wells, 2005:129) The third (III) article of the convention describes what should be punished: “The following acts shall be punishable:

1. Genocide;

2. Conspiracy to commit genocide;

3. Direct and public incitement to commit genocide; 4. Attempt to commit genocide;

5. Complicity in genocide” (UN Resolution 260, 1948).

The biggest fault with the convention is that the definition leaves out social and political groups and is therefore incomplete. This is important because the use of the term genocide on what happened in Rwanda depends on how one chooses to denote the Hutu and Tutsi population. Either they are denoted as two groups based on social structure as it was before the colonial era, or as two groups based on ethnic difference which it came to be after the colonial era. This is important to know however it not of concluding importance to this thesis.

4.3 France

France had a very interesting role in Rwanda. France, as an old colonial power in Africa, wanted to maintain their influence in Africa and France actually had troops in the country before the genocides began. Their role was, according to official sources to”protect French citizens and other foreigners” (Melvern, 2007:49), but aid workers reported that they had seen how French military personnel manned artillery positions in the war between the RPF and government forces. French soldiers were also seen manning check-points in Kigali, controlling identity cards and passing over Tutsis to the Rwandan army (Melvern, 2007). Melvern (2007) notes that “the full story of French involvement will never be known” (p.48), but what is known is that five days after the genocides began, the French embassy in Kigali was abandoned only leaving thousands of shredded documents. Another known fact is that France gave aid to Rwanda in the form of military training, weapons, army vehicles, helicopters etc, which resulted in an increase from 5,000 to 28,000 soldiers in the Rwandan Army of which all were Hutus (Melvern, 2007). French weapon producers continued to deliver arms to Rwanda under government permit during the face of the actual genocide (Meredith, 2005). According to Melvern, a total of US$ 10 million was given in military aid from France alone between 1991 and 1993.

France would later ‘switch sides’ in the conflict, actually being the only country voluntarily sending troops to Rwanda to stop the genocide in their much criticized “Operation Turquoise”. This intervention which occurred late in the conflict was much criticized for not being neutral, which violates UN policy.

4.4 The United States of America

The United States (US) played an important role in the conflict since they were seen as the only nation with the efficient capacity to make a rapid deployment of troops that would contribute to a major change in the outcome of the conflict. After the iron curtain had fallen and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the US was the only superpower left in what now had become a unipolar world. The president at the time was Bill Clinton who was in his first mandate period as President. Mid-term elections were coming up in November of 1994, which was a crucial event taking place in the US. Therefore the pressure on the President was high not to make any failures that could cost him and his administration a loss in the elections. The US had no direct interest in Rwanda except defending their ‘own values’ such as human rights, democracy, freedom, etc. Rwanda was ”considered a low priority, the United States maintained only a single human intelligence asset in central Africa…” (Kuperman, 2001:23), which is a further point of reference to their low interest in this part of Africa.

The US faced a high reputational loss from the tragedy in Somalia in 1992 where eighteen US soldiers lost their lives in what was thought to be a quick ‘in-and-out-operation’ in Mogadishu. The result of the operation was eighteen casualties and 78 wounded (Ausink, 1996). Pictures were broadcasted from Mogadishu with images of dead American soldiers being dragged after cars with cheering crowds. On August 10th, 1993, UN Ambassador

Madeleine Albright said that US forces would ”stay as long as needed to lift the country and its people from the category of a failed state into that of an emerging democracy” (Ausink, 1996:4). By the seventh of October, President Clinton announced that all US troops would be withdrawn by March 31, 1994 (Ausink, 1996).

The UN approved the US intervention on the third of December, 1992, and the first American soldiers landed on the beaches of Mogadishu by the ninth of December (Meredith, 2005). What is very important to point out here, because it will have an effect on the following decisions made by the US, is the cost of the Somali intervention which added up to $2 billion. An intervention that lasted sixteen months cost $2 billion and the reputational loss to the US was immense.

4.4.1 The Presidential Decision Directive

This document plays a very important role for the US non-intervention in Rwanda since it was this document the US claimed partly blocked them from intervening.

The Presidential Decision Directive (PDD; final draft called PDD25), was created as a ”guide for future U.S participation in and funding of multilateral peace operations” (Ausink, 1996:4). A draft of the PDD was approved on the 19th of July, 1993. In this document one could read that the PDD ”represented a major, albeit evolutionary, change in the U.S policy toward multilateral peace operations… …which supported an enhanced use of multilateral operations, elevated the United Nations as a major actor on the world stage, and committed the United States to support such operations in all of their political, military, and financial dimensions” (Daalder as cited in Ausink, 1996:4). With a statement like this, one undertakes great responsibility.

The aforementioned document was just a draft and the events in Somalia would soon lead to a call for reworking the PDD. President Clinton signed the final draft on May third, 1994. ”The policy represents the first, comprehensive framework for U.S. decision-making on issues of peacekeeping and peace enforcement suited to the realities of the post Cold War period” (Bureau of International Organization Affairs, 1994).

The basic outline of the PDD-25 is that for the US to participate, a series of criteria’s has to be met. Among them are:

1. There must be an identifiable interest from the US at stake,

2. The mission have to have a clear definition in the area of the size, duration and scope of the mission,

3. There has to be a political will to execute the mission,

4. There has to be an identified exit strategy for ending the US involvement in the mission and finally,

5. The US should not pay more than 25% of the peacekeeping budget.

Perhaps most interesting in the PDD-25 is the final conclusion at the bottom of the document: “Properly constituted, peace operations can be one useful tool to advise American national interests and pursue our national security objectives. The U.S. cannot be the world’s policeman. Nor can we ignore the increase in armed ethnic conflicts, civil wars and the collapse of governmental authority in some states – crises that individually and cumulatively may affect U.S. interests. This policy is designed to impose discipline on both the UN and the U.S. to make peace operations a more effective instrument of collective security” (Bureau of International Organization Affairs, 1994). The PDD-25 is an important document that the US would lean against in making their decisions.

4.5 Belgium

Belgium’s role in Rwanda can be seen as quite moderate. In 1990, on the 14th of October, the Belgian Prime Minister, Wilfried Martens went to Nairobi to settle a ceasefire between the RPF and the Rwandan Government They did, through their diplomats in Rwanda, receive early warning signs of what was about to come. The Belgian ambassador reported in early spring, 1992 that the Akazu group (which will be explained on the next page) was planning for an extermination of the Tutsis in Rwanda (Meredith, 2005). In 1993, a report was published revealing that during the last two years there had been organized killing of Tutsis and members of the opposition had been tortured and thrown in jail. The Belgians reacted by threatening to reconsider its military and financial aid if the situation didn’t improve. During the negotiations in Arusha between the RPF, the opposition and the Rwandan Government, Belgium had observing status (Melvern, 2007).

When it came to sending troops on a UN mandate, Belgium would volunteer to send 400 troops of different ranking. The chief of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), Romeo A. Dallaire criticized Belgium for sending personnel who did not have the sufficient training in peacekeeping and for sending troops who would better fit in peace enforcement and not in peacekeeping (Melvern, 2007; Meredith, 2005).

In 1994, after the Presidential plane was shot down over Kigali carrying President Habyarimana and the Burundi President 6thof April, the violence escalated and as a total of

ten Belgian peacekeepers were subsequently murdered by the Rwandan Government Forces. The Belgian Government would two days after decide to withdraw their troops from Rwanda (Ausink, 1996).

4.6 Summary

There were several countries and international institutions, which all played an important role. These were the RPF, the UN, France, the US, and Belgium. They all had some interest in the conflict and also some constraints. The RPF wanted to gain influence in the power structure of Rwanda, the UN wanted to defend human rights and promote stability and peace, and France wanted to gain bigger influence in Africa. The US was first and foremost defending its own values and as the only superpower left in the world and the only country with sufficient capabilities to make a difference in the conflict, was caught in the headlights of the conflict. They were constrained to act due to the PDD-25, which blocked them from participating in missions in Rwanda except from pure humanitarian assistance. Belgium, Rwanda’s former colonial master, saw early signs that genocide was being prepared and would be among the few countries to voluntarily send troops to Rwanda.

5

The Escalating Conflict, 1990 to 1993

The key actors have been introduced in the conflict in Rwanda, and this section will now concentrate on the events that lead up to the escalating conflict. The Arusha Accords will be presented in more detail as well as the world’s reaction to these events.

5.1 United Nations Observer Mission Uganda Rwanda-

UNOMUR

RPF operated over the border from Uganda into northern Rwanda. The conflict spread into Uganda and the two governments posed a mutual request to the United Nations where they called for assistance to monitor the border between the two countries, in order to prevent the RPF from reaching into Rwanda. The mission set up was the United Nations Observer Mission Uganda Rwanda (UNOMUR) (Meredith, 2005).The resolution was passed in the Security Council June 22, 1993, as resolution 846.

5.2 The Arusha Accords

After years of tension and war between the RPF and the government forces with thousands of deaths, the outside world now started to react. News spread from Rwanda that there were plans of a genocide against the Tutsi population from a group called ”Akazu”. Akazu was a secret group, with close connections to president Habyarimana's wife. This group worked as a mafia in northern Rwanda and their death-squad was known for notorious murdering of members of the opposition and of Tutsis (Melvern, 2007). They had on their agenda to get rid of the Tutsi population in Rwanda ”to resolve once and for all, in their own way, the ethnic problem and to crush the internal Hutu opposition” (Melvern 2007:43).

In May 1992, the RPF met with members of Rwanda’s political opposition in Brussels where they decided that they should start to work together in order to expose the misdeeds of Habyarimana’s regime. At this point the US also started getting interested in what happened in Rwanda, and to help promote peace the US sent ”Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, Herman Cohen, to try to contribute to peace talks between the government and the RPF” (Melvern, 2007:47). The peace talks between the RPF, the political opposition and the ruling government began in July 12th, 1992 in Arusha,

Tanzania.

In the Arusha talks, the sitting government in Rwanda did not only have to negotiate with the RPF, but also with other opposition parties. The sitting government was highly fragmented and the RPF is described by Stettenheim (2002) as very well organized and by this they were able to exploit the weaknesses of the sitting government. ”A former RPF official described the basis of the party’s success at the table as fourfold: 1) they were highly motivated because they felt that they were fighting for a just cause, 2) their strong organization and discipline allowed them to speak unfailingly with one voice, 3) they were in a strong negotiation position because of their military successes, and 4) they were able to more effectively develop support among the observer group” and further; ”the RPF argued for the creation of a pluralistic Rwandan society that guaranteed individual rights and was not based on ethnicity” (Stettenheim 2002:225).

President Habyarimana withdrew his support for the negotiations by November 15, 1992, referring to the protocols as merely ”pieces of paper” (Stettenheim, 2002). At the same time as the talks were going on in Arusha, Habyarimana’s regime signed a weapons deal worth US$ 12 million with a French company. Just to understand what this money could

buy, the order included 1,000 pistols, 4,000 AK 47s, 40,000 grenades, 29,000 bombs, and 7 million rounds of ammunition (Melvern, 2007). The regime handed out weapons to the Hutu population with the explanation that ”the locals have to be able to defend themselves against rebel and guerilla forces because there were not enough troops” (Melvern, 2007:55). This information was passed to the outside world by several relief agencies that had witnessed this. In other words; the world did know.

The Arusha talks ended with the signing of the Accords on August 3, 1993. The final package of protocols included:

• Amended cease-fire

• Principle and creation of the rule of law

• Power sharing, the enlargement of the transition government and the creation of a transition parliament

• Reintegration of refugees and internally dislocated persons

• Creation of a nationally unified army (merger of RPF and FAR1) (Stettenheim, 2002).

As an initial stage in the implementation of the Arusha accords, according to the accords, one battalion of RPF soldiers would be stationed in Kigali, a transitional government was to hold power until free elections could be held no later than twenty-two months after being given power (Melvern, 2007).

The Arusha accords also provided a role for the UN to intervene with a Neutral International Force that was supposed to supervise during the transition period. Both the RPF and the Rwandan Government had requested such a force and had in a letter to Secretary-General requested for a reconnaissance team to Rwanda to plan the force. The force should be assigned wide security task such as guarantee the overall security in the country, ensure delivery of humanitarian aid and also to assist in tracking arms, undertake mine clearance and to determine security parameters for Kigali with the objective of making it to a neutral zone (UN S/1999/1257).

Although both the parties showed signs of cooperation and willingness to take the Arusha Accords seriously they had claims on the UN which could not be met. Among them was that they exercised a sort of blackmailing by delaying the actual signing of the accords until their demands were met. They pressured the UN to send troops before signing the protocols and they requested UN forces to be deployed within one month of the signing, which was according to the UN impossible to meet (UN S/1999/1257).

One week after signing of the Agreement a report was published, by the UN, describing the terrible conditions in Rwanda and the author did also bring up the question if the term genocide was applicable on the situation. ”This report seems to have been largely ignored by the key actors within the United Nations system” (UN S/1999/1257:7).

In order to follow up the Arusha Accords and the following agreement being signed, Secretary-General sent a reconnaissance team to Rwanda to find out possible functions and resources that was expected to be needed in this type of peacekeeping mission. This mission was led by Romeo A. Dallaire. Dallaire was at this point in time the Chief Military Observer of the UNOMUR. ”On 15 of September, a joint Government-RPF delegation met with the Secretary-General in New York. The delegation argued in favor of the rapid deployment of the international force and the rapid establishment of the transitional

institutions” (Carlsson, Han & Kupolati, 1999:7). The delegation also argued that any delay might cause the peace process to collapse. They asked for 4,260 troops to be deployed to Rwanda, but Secretary-General gave the delegation a sobering message that even if the council would approve a force of this size, it would take several months before it could be deployed.

5.3 United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda - UNAMIR

On October 5th, 1993, the Security Council in the UN adopted resolution 872 which

allowed for a peacekeeping operation in Rwanda, and the former UNOMUR mission was merged with the UNAMIR forces. The force was supposed to have 2,548 troops, a little less than two thirds asked for by the delegation two weeks earlier. The decision of the size of the force would later prove fatal. The Secretary-General had asked for a number of responsibilities and actions to be undertaken by UNAMIR, but all of these were not approved by the members of the council. One of these suggestions was that the UNAMIR forces should be permitted to recover arms, a strategic action that was seen as vital by the Secretary-General in order to prevent the outbreak of uncontrolled civil war. The main elements of the mandate were to monitor the cease-fire agreement, demarcate a demilitarized zone, assist with mine clearance, assist in the coordination of humanitarian assistance, etc. (Carlsson, Han & Kupolati, 1999).The United Nations solicited troop contributions, but initially only Belgium ,with half a battalion of 400 troops, and Bangladesh , with a logistical element of 400 troops, offered personnel. It took five months to reach the authorized strength of 2,548.

Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire, who was appointed Force Commander of UNAMIR, sent a draft set of Rules of Engagements2to the UN Headquarters asking for the allowance

to use force to prevent or to fend of crimes against humanity, but received no official answer.

In late October the President of Burundi3, the first Hutu elected to the post after

twenty-eight year of Tutsi control, was assassinated by members of the all Tutsi army. This lead to a flow of refugees, estimated to 200,000, from Burundi due to the conflict arising there. According to Melvern (2007) this was the end of the peace process in Rwanda. This was an event that the UN had not foreseen when the mission had been set up and so the mission of UNAMIR was short-staffed. The Hutu refugees from Burundi brought with them a message of ”Never trust a Tutsi!” which spurred the existing conflict between the Hutus and Tutsis.

At the end of December, an RPF battalion was installed in Kigali at the Conseil Nationale du Développement (CND) complex in accordance with the Arusha Agreement. There were clear signals and even physical evidence in the form of hidden weapons, that General Habyarimana did have something to hide. Informants took contact with the UNAMIR forces and told them that the Interahamwe, which was an extremist youth wing of the sitting government, planned genocide. Dallaire sent several messages to the UN headquarters asking for permission to follow up these clues, but was constantly denied. There was an obvious lack of communication between the different departments within the UN since officials who had power in these questions claimed that some of Dallaire’s messages sent did not reach through (Carlsson, Han & Kupolati, 1999).

2Rules of Engagement (ROE) is a military term describing when, where and how force should be used. They

can be seen as a set of guidelining rules of how one is allowed to act, i.e. ”you cannot fire until fired upon”, ”only use force in case of self defense”.

Dallaire took direct contact with Habyraimana to discuss these questions along with other questions that needed answers, but with no real effect. Habyarimana practiced fraud negotiations in order to buy time and promised to set up investigations to hunt down the problems presented by the UNAMIR troops.

In early 1994, problems continued to rise in Rwanda. Dallaire asked for permission for more direct interventions by UNAMIR troops but was denied and ignored by the UN who obviously did not take Dallaire’s fears seriously.

On the 21nd and 22rd February, the leaders of two opposition parties were killed and tension rose in both Kigali and in the rest of Rwanda. Dallaire reported to the UN that weapons were being distributed by the army and that death squads started listing people as preparation for war. The former Foreign Minister of Cameroon, who was appointed as Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali’s representative in Rwanda, reported that the violence might be ethnically motivated and directed towards the Tutsi minority. But the signals were considered too weak to pass as conviction.

The UNAMIR not only had to fight for their right in Rwanda, but also in New York at the UN Headquarters. As mentioned before, Rwanda had a seat in the Security Council, which was acting as a restraint on the council. The US wanted to see a time limit on UNAMIR’s mandate and demonstrated a tough policy, where the main focus was not only placed on the case of Rwanda, but on the UN as such (Melvern, 2007). President Clinton stated in the UN General Assembly on September 27, 1993, that ”The United Nations simply cannot become engaged in every one of the world’s conflicts” (Ausink, 1996) and this might be seen as reason for the US’s non-intervention policy. To sum up, UNAMIR lacked authority, personnel, training, weaponry, etc. Perhaps the most serious issue about the UNAMIR mission was that they were not properly backed up by the UN headquarters.

5.4 The Death of President Habyarimana – the Final Strike?

On the 6thof April 1994, president Habyarimana and the President from Burundi, Cyprien

Ntaryamira who had been elected Burundi’s President after the assassination of Melchior Ndadye, flew back from a sub regional summit under the support of the facilitator of the Arusha process, Tanzania’s President Ali Hassan Mwinyi. According to Tanzanian officials, the talks in Dar es Salaam had been successful and President Habyarimana had committed himself to the implementation of the Arusha Agreement. Recognizing it as being true, this could have turned the situation over, but a tragic event later the same night meant that there would no longer be a peaceful solution to the conflict.

At approximately 20:30 that night, as the plane came in for landing in Kigali, it was hit by a missile and the plane crashed and left no survivors. ”By 21:18, the Presidential Guard had set up the first of many roadblocks. Within hours, further road-blocks were set up by the Presidential Guards, the Interahamwe, sometimes of the Rwandan Army, and the gendarmerie” (Carlsson, Han & Kupolati, 1999:15). Less than an hour after the plane was shot down the genocide began. This can only lead to the conclusions that genocide actually must have been planned and it was only a question of when it was about to start.

UNAMIR troops tried to reach the crash site of the plane, but was not only denied access, but also disarmed and placed in custody at Kigali Airport. Politicians from the different parties contacted UNAMIR asking for protection as they were seen as targets. There are numerous stories about how these politicians were executed, their families beaten up or raped without the UNAMIR troops intervening. The ROE for UNAMIR personnel was to

Ten Belgian peacekeepers were beaten up, tortured and killed as they tried to protect one of the ministers in the government. The slaughter of Tutsis began simultaneously as their names and addresses had already been listed. The national radio station, Radio Mille Collines, broadcasted Hutu leaders who said that the war against the Tutsis is everyone’s responsibility and submitted messages with names and addresses of Tutsis (Meredith, 2005). In the literature there are stories telling how Hutus burst into churches, slashing everyone in there, leaving the whole church with dead and wounded on top of each other. The ongoing situation only seemed to worry the outside world in the sense that they needed to evacuate their own citizens in the area. On the 9th of April the French arrived to evacuate their personnel, but also persons who belonged to Habyarimana’s clique, the akazu, ”whom France had supported for so long and who had been deeply involved in planning genocide” (Meredith, 2005:509). Among the evacuated with the French was also the director of Radio Milles Collines who had broadcasted and organized the hate broadcasts.

For the UNAMIR, they were now supervising a collapsed peace process. They had food for less than two weeks and water for two days (Dallaire, 2003). Dallaire was asked to make a plan for withdrawal of the UNAMIR troops and on the 15thof April the Belgian

government announced that they would withdraw their troops from UNAMIR (Melvern, 2007).

In meetings in New York at the UN on the 21stof April a resolution was passed which

meant that the UNAMIR force was decreased to include 270 men. Thousands of people were killed every day and there was no place to consider safe.

5.5 UNAMIR II

On the 17thof May 1994, less than a month after the decision had been undertaken to

withdraw a majority of the UN troops from Rwanda, the international involvement took a new turn. UNAMIR II was established as a result of a new resolution authorizing a second UNAMIR force consisting of 5,500 troops. This is yet another proof of the inefficiency of the UN since there were no troops or equipment yet identified. In other words there was no concrete plan of who was actually going to supply these troops. On the 8thof June the

resolution became consolidated by the Security Council’s approval. It was also in this resolution that the UN first mentioned the word “genocide”, not in clear text but wrapped up using the term “acts of genocide”. As Meredith asks in his book “The State of Africa”, “How many acts of genocide does it take to make a genocide?” (Meredith, 2005:519). While the genocide was still in progress, France sent weapons to the Rwandan government on at least five occasions between May and June (Meredith, 2005), and on June 14ththe

French President Mitterrand, authorized plans for sending troops to Rwanda dressing it up as a humanitarian mission. This would lead up to the very controversial mission that would be called operations Turquoise.

5.6 Operation Turquoise

In mid June and in the deadlock that was present, France called for other nations to join in on a French led operation in Rwanda if the UN did not approve the Secretary-Generals request for a peacekeeping force consisting of 5,500 troops. France themselves proposed sending 2,500 French soldiers. Belgium refused, due to their previous loss of 10 peacekeepers in earlier efforts. On June 22nd, the UN accepted the French initiative. In the

Security Council the US, UK, and Russia voted for the resolution while China abstained (Ausink, 1996). What made the Security Council accept the offer and even the US to vote in favor for the proposition was that France was willing to take the costs themselves for the

operation. General Dallaire was hostile to the offer since he believed that their intentions were to serve the interim Government, a belief that would prove right. The French mission was backed up by heavy mortars, one hundred armored vehicles, ten helicopters, fighter jets, and Special Forces. To many it seemed that the problem was a non-neutral French operation and who had been criticized for actively backing up the Hutus both in operation Turquoise and in their previous involvement in Rwanda.

The Operation Turquoise was given “a chapter VII mandate”, which is peace enforcement rather than the previous peacekeeping mandate, which is referred to as “chapter VI mandate”(Howard, 2008). The chapter refers to the chapters in the UN charter. The French intention was to reach Kigali, but due to the risks they stopped southwest of Kigali on the 4thof July 1994, where they were commanded to set up a secure humanitarian zone

(Meredith, 2005). In Meredith (2005) he writes that the French soldiers had been fooled by their government that it was the Tutsis killing the Hutus and not the other way around. When setting up the secure humanitarian zones they soon realized it was more of the other way around; that in fact the Hutus were killing the Tutsis as they were overrun with Tutsi refugees seeking protection. This is another fact that speaks in favor of the belief that the French Government, with President Mitterrand in the lead, supported the Hutus and the former sitting government (Meredith, 2005). This, along with the evacuation of members of the Akazu group, is very controversial keeping in mind what they may have been responsible for.

5.6.1 The Delusion of Impartial Intervention – A Response to Operation

Turquoise

A very controversial text is written by Richard K. Betts (1994) on the notion of impartial intervention in conflicts. Betts argues that the root of the issue in war is; who rules when the fighting is over? He has a belief that the strongest one will win and that trying to help the weak is only going to prolong the conflict. Parts of the text ”The Delusion of Impartial Intervention” can be considered very controversial since it goes against what a majority of people, along with the UN, thinks is the best way to solve conflicts.

Betts claims that the old saying that intervention should be both limited and impartial is consistent with the old-fashioned UN peacekeeping operations ”where the outsiders’ role is not to make peace, but to bless and monitor a cease-fire that all parties have decided to accept” (Betts, 1994:20). This delusion becomes destructive when it comes to the realm of peace enforcement. This is very interesting when looking at the case of operation turquoise by the French when they were blamed for not being neutral in their intervention. According to Betts (1994), limited intervention may end a war if the intervener takes sides, and impartial intervention may end a war if the outsider takes complete command over the situation. ”Trying to have it both ways usually blocks peace by doing enough to keep either belligerent from defeating the other, but not enough to make them stop trying” (Betts, 1994:21).

In this text one could find support for the French soldiers in their accused biases in the conflict since Betts argues that the use of deadly force must serve the purpose of settling the war; if it is not, then it is just senseless killing. Settling the war means determining who rules and it means leaving someone in power at the end of the day. Compromising is only useful when both sides of the conflict see that they have more to lose than to gain from fighting. Since leaders often are reasonable, this happens before a war starts which is why most conflicts and crisis are resolved by diplomacy rather than combat (Betts, 1994). This is where it went wrong in the case of Rwanda. There had been efforts made in cooling

conflicts in surrounding countries induced the two parties to see greater gains in fighting than in solving the conflict by compromise and diplomacy.

Finally, in the text by Betts (1994), he states: ”Do not confuse balance with peace or justice. Preventing either side from gaining a military advantage prevents ending the war by military means. Countries that are not losing a war are likely to keep fighting until prolonged indecisions makes winning seem hopeless. Outsiders who want to make peace, but do not want to take sides or take control themselves try to avoid favoritism by keeping either side from overturning an indecisive balance on the battlefield. This supports military stalemate, lengthens the war, and costs more lives” (Betts, 1994:32).

By using this text to analyze and explain the French intervention, one might draw the conclusion that if the French intervention was meant to stop the killing by shortening the war, using the method of supporting the stronger part, the French decision of supporting the Hutus was wrong. This is so because the RPF, the Hutus enemy, was the strongest side militarily speaking, and the one who was seen as the winner in the conflict.

5.7 End of the Genocide

By the 4thof July the RPF forces reached Kigali. The radio station “Radio Mille Collines”

continued to spread fear and terror messages and also encouraged the remaining Hutus in the capital to flee. This added to further instability and chaos in the region as nearly one million refugees crossed the border from Rwanda to Zaire4in just two days. Officials who

had been pointed out to be responsible for different parts of the genocides were walking through French checkpoints with the motivation that the French soldiers had not been authorized to arrest them, since doing so could undermine the French neutrality (Meredith, 2005).

Paul Kagame, the leader of the RPF soldiers, was installed as vice-president on July 19th

and a new government with a power sharing structure between Hutus and Tutsis was enforced. Summing up the genocide; over the period of 100 days 800,000 people were killed. That is 8,000 people per day, which means that the killing rate was five times that of the Nazis. Of these 800,000 victims, the majority was Tutsi, and in total three quarters of the Tutsi population was killed.

The Security Council decided to establish the International Criminal Court for Rwanda (ICTR) (Mingst & Karns, 2007). The decision was taken with passing resolution 955 at the 8th of November 1994. The ICTR was established for the prosecution of persons

responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of Rwanda between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 1994. It may also deal with the prosecution of Rwandan citizens responsible for genocide and other such violations of international law committed in the territory of neighboring states during the same period (United Nations, International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. 2009).