Applications to enhance

participa-tion in everyday life for

children/ado-lescents with ID and ASD

A systematic literature review

Elise Flantua

One year master thesis 15 credits Maria Björk

Interventions in Childhood

Lilly Augustine/ Eva Björck Spring Semester 2021

2 SCHOOL OF EDUCATION

AND COMMUNICATION (HLK) Jönköping University

Master Thesis 15 credits Interventions in Childhood Spring Semester 2021

ABSTRACT

Author: Elise Flantua

Applications to Enhance Participation for Children/Adolescents With ID and ASD

A systematic literature review

Pages: 30

Mobile phones are a central part of the everyday life of children and adolescents. How-ever, the accessibility of using this technologies is not equal for all children/adoles-cents. Children with ID are under those who are being disadvantaged. Participation is considered important for both learning and development as well as for the health and wellbeing of a child. The aim of this study is to explore how applications can facilitate participation in society for children/adolescents with ASD or ID. Therefore, this sys-tematic literature review was performed. The results indicate that there were applica-tions available to support living skills, vocational skills, planning, and an event and thereby enhance participation in society. The results show that teaching children and adolescents in steps how to use the app, while preforming the task, is an effective way of teaching these children and adolescents a new skill. The identified articles show an increase of participation in different tasks (e.g. vacuum cleaning, grocery shopping, planning and attending events). Further research is needed to see if it would be possi-ble to create an application that addresses multiple tasks. Furthermore, the majority of the participants were male participants, future research should indicate how usable the applications are for females.

Keywords: Adolescents, Applications, Children, Daily Living, Participation,

Neurodevel-opmental Disabilities, Vocational Training.

Postal address Högskolan för lärande och kommunikation (HLK) Box 1026 551 11 JÖNKÖPING Street address Gjuterigatan 5 Telephone 036–101000 Fax 036162585

3

Table of Content

1 Introduction ... 6

1.1 Introduction ... 6

2 Background ... 6

2.1 Living with Autism Spectrum Disorder or Intellectual Disabilities ... 6

2.1.1 Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) ... 7

2.1.2 Intellectual Disability (ID) ... 8

2.2 Applications ... 8

2.2.1 Applications used by everyone ... 8

2.2.2 The use of applications by children with ID ... 9

2.2.3 Applications used by children with ASD ... 9

2.2.4 Applications used in healthcare... 10

3 Theoretical Frameworks ... 10

3.1 Participation in Everyday Life ... 10

3.2 Five A’s of Participation... 10

3.3 Rationale ... 11

3.4 Aim and Research Questions ... 12

4 Method ... 12

4.1 Systematic literature review ... 12

4.2 Search strategy ... 13 4.3 Selection criteria ... 13 4.4 Selection process ... 15 4.5 Peer review ... 17 4.6 Data extraction ... 17 4.7 Quality assessment ... 17

4

4.8 Ethical Considerations ... 19

5 Results ... 20

5.1 Characteristics of Included Articles ... 20

5.2 Areas in which the applications were available ... 21

5.3 How the applications were accommodated to the child’s special needs. ... 22

5.4 The effect of the applications on these children´s accessibility in society ... 23

5.5 How affordable were these applications ... 27

5.5.1 Affordability related to the concept of money ... 27

5.5.2 Affordability in concept time ... 29

5.5.3 Affordability in concept of energy ... 29

5.6 How willingly (acceptable) were these children/adolescents in using the apps ... 30

6 Discussion ... 31 6.1 Reflection on findings ... 31 6.1.1 Availability ... 31 6.1.2 Accommodability ... 32 6.1.3 Accessibility ... 33 6.1.4 Affordability ... 34 6.1.5 Acceptability ... 35

6.2 Methodological considerations and study limitations ... 35

6.3 Quality limitations of the articles ... 35

6.4 Practical Implications and Future Research ... 35

7 Conclusion ... 36

8 References ... 37

9 Appendix ... 47

9.1 Extraction protocol for the full- text screening: ... 47

5 9.3 Appendix 3 ... 51 9.4 Appendix 4 ... 55

6

1 Introduction

1.1 Introduction

Every child has the basic human right to participate in activities at home, at school, and in their community (UN General Assembly, 2020). Participation in daily activities is associated with positive outcomes (Willis, et al., 2017; Tonkin, et al., 2014) such as increased compe-tence and the increase of self-sense and personal preferences(Bright et al., 2015). Nonethe-less, young people with disabilities are likely to face restrictions and exclusion when trying to participating in everyday life activities (Schlebusch, et al., 2020). To manage daily living skills, such as personal care, banking and money management skills, grocery shopping, and communication and social skills, can be hard for children with neurodevelopmental disabili-ties. Limitation in these activities affects the child’s autonomy and self- determination (Ayres, et al., 2013; Van Laarhoven, et al., 2009). Being able to complete daily living skills can in-crease their independence, ability to take initiative and encourage their development of further abilities (Cannella, et al., 2005). With recent advances in technology and the use of mobile de-vices (smartphones), more individuals with neurodevelopmental disabilities take advantage of using (mobile) technologies to increase their independent living skills, while decreasing their reliance on others (Ayres, et al., 2013; Mechling, 2011). Therefore, it is important to investi-gate in which areas applications are available that enhance participation in everyday life set-tings for these children and adolescents. However, since neurodevelopmental disorders is a broad group of different disorders (e.g. Autism spectrum Disorder, Intellectual Disabilities, Attention-Defict/Hyperactivity Disorder, and Speech Disorder) (American Psychiatric Asso-ciation [APA], 2013), will this research primarily focus on Autism Spectrum Disorder and In-tellectual Disabilities, to make the research more specific.

2 Background

2.1 Living with Autism Spectrum Disorder or Intellectual Disabilities

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (APA, 2013), highlight that neuro-developmental disorders are typically manifest in the early development, often before the child starts school. Neurodevelopmental disorders are characterized by developmental deficits that can lead to impairments in personal, social, academic, or occupational functioning. Examples

7 of neurodevelopmental disorders are Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Intellectual Disabili-ties (ID), and learning disorders. This thesis will mostly focus on ASD and ID. However, neu-rodevelopmental disorders often co-occur, for example: individuals with ASD often also have ID (APA, 2013).

2.1.1 Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

ASD is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts. Therefore, children with ASD can experience difficulties initiating or respond to social interactions. Further on, children with ASD can experience difficulties in non-verbal communications such as: abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and using gestures. They can also experience difficulties in developing, main-taining, and understanding relationships. Therefore, children with ASD can show an absence of interest in peers (APA, 2013). There are different manifestations of the disorder, depending on the severity of the autistic condition, developmental level, and chronological age; hence, the term spectrum. Different forms of autism fall under this spectrum such as: childhood autism, Kanner´s autism, high- functioning autism, atypical autism, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, childhood disintegrative disorder, and Asperger´s disorder (APA, 2013). Symptoms can often be recognized during the second year of life (12-24 months of age), but symptoms may be seen earlier than 12 months if developmental delays are severe, or noted later than 24 months if the symptoms are more subtle (APA, 2013)

Further, epidemiological research has estimated that males with ASD outnumber females with the disorder at rates of 1.9-16 (Fombonne 2003, 2005, 2009; United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [US CDC], 2012). An explanation for this phenomenon can be that the male and female brains are differently hard-wired. This results in males exhibiting relative strengths in systemizing (e.g., understanding and building systems) and females exhibiting rel-ative strengths in empathizing (e.g., identifying with other´s thoughts and feelings with appro-priate responding) (Baron-Cohen 2002; Baron-Cohen and Hammer 1997; Baron-Cohen et al. 2005). Additionally, it is possible that males may be more vulnerable to develop ASD given that ASD traits stem from an extreme form of the male pattern of neurodevelopment, and fe-males may be less likely to have ASD because of their hard-wired empathizing abilities and social competencies (Baron-Cohen 2002; Baron-Cohen and Hammer 1997; Baron-Cohen et al. 2005).

8 In addition, ASD is frequently associated with intellectual impairment and structural language disorder. Many individuals with ASD have psychiatric symptoms that are not part of the ASD criteria. About 70% of the individuals with ASD have one comorbid mental disorder and 40% may have two or more comorbid mental disorders. It is hence important that, if besides ASD, criteria for another disorder are met, that this disorder should also be given a diagnosis (APA, 2013).

2.1.2 Intellectual Disability (ID)

ID is characterized by significant limitations both in intellectual functioning and in adaptive behaviour as expressed in conceptual, social, and practical adaptive skills. ID originates before age 18 (Schalock et al., 2010,). Children with ID can experience difficulties in problem solving, planning, abstract thinking, academic learning, and learning from experience. They can also experience difficulties with personal independence at home or in community settings (adaptive functioning) (APA, 2013). The term “mild” and “severe” are used in combination with ID. However, Snell et al., (2009) avoided the use of the mild term and instead used descriptions as “people with intellectual disabilities who have a higher IQ”. This approach indicated the alter-native contemporary concept of ID as a spectrum disorder, with those with mild ID, are seen as being more at the upper end of the intellectual disability spectrum (Polloway et al., 2017). Just like in ASD, males are more likely than females to be diagnosed with both mild and severe forms of ID (ratio mild: 1.6:1, ratio severe: 1.2:1). However, it should be noted that these ratios vary widely in reported studies.

2.2 Applications

2.2.1 Applications used by everyone

Tablets and mobile devices are becoming more and more a part of children’s and adolescents´ everyday life. As an example, mobile phones are used by adolescents to interact with their peers (Tapscott, 2009). There are a variety of downloadable games and chatrooms, which especially attracts children to use mobile phones (Schüz, 2005). WhatsApp, Facebook, Messenger, Insta-gram, and Snapchat are examples of applications used to communicate with their friends and family. Besides communication, phones are used to order a taxi (with Uber) or to watch videos on YouTube (Marks, 2017). There is also an increased popularity of mobile bank applications that offers the bank customer to conduct financial transactions such as: checking account bal-ances, transferring money, and paying bills (Malaquias and Hwang, 2019). A Swedish study

9 (Davidsson and Findahl, 2016) showed that two out of three bank users, in the age of 16-25, frequently use a mobile banking app. Nevertheless, certain groups of people are at risk of being left behind when it comes to using (internet) applications, one example are people with ID (Chadwick et al., 2013; Kennedy et al., 2011).

2.2.2 The use of applications by children with ID

Young people with ID do not use these technologies as frequently as the general population (Government of Sweden, 2003; Scholz, et al., 2017). This entails that young people with ID less frequently participate in social life. This may affect their abilities to have interpersonal relationships and social inclusion (Asselt-Goverts et al., 2015; Simões & Santos, 2016; Umb-Carlsson & Sonnander, 2005). Since people with ID may have deficits in intellectual and adap-tive functioning in conceptual, social or practical domains, using the internet can be a compli-cated activity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Tassé et al., 2016). Darcy et al. (2016) demonstrated that the use of smartphones made it easier for the participants to seek social sup-port from their friends and family when they were on their own. That gave them more confi-dence to participate in everyday life activities (Darcy, et al., 2016). However, it is important to keep in mind that these technologies alone are not responsible for such benefits. Previous re-search has highlighted that there is a need for adapting support for each individual using the technologies (McNaughton and Light, 2013; More & Travers, 2012; Näslund & Gardelli, 2013; Ramsten et al., 2018; Sorbring et al., 2017). Darcy et al. (2016), concluded that those partici-pants who got the most out of using mainstream technologies (e.g. for communication and so-cializing) were those who received ongoing support such as training and technical adaption.

2.2.3 Applications used by children with ASD

Children with ASD appear to have an interest in computers and technology (Kuo et al., 2014). Technology tools are increasingly used to assist with earl diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring progress for individuals with ASD (Charlop-Christy & Daneshvar, 2003; Goldsmith & Le-Blanc, 2004). One example of an application for children with ASD is SideKkicks! (Birtwell et al., 2019). This applications facilitates therapeutic interactions with a coach (e.g. parent, thera-pist) and the child, through a chat function. Sidekicks! uses an avatar, which the child can select him/herself. In the application the child can watch videos, these videos coach the child in his/her social- emotional development.

10

2.2.4 Applications used in healthcare

There are applications designed for patients to organize and communicate information about their health care needs. Jiam et al. (2017) developed the application “Important Information About Me” (IIAM) where children and adolescents can share information at a physical therapy session, an patient intake, or a meeting with a (new assigned) case worker. Further, there are also applications developed to for example assess and monitor children who has chronical pain with tracking their behaviour, observing changes, and sharing information with their healthcare providers (Jamison et al., 2018).

3 Theoretical Frameworks

3.1 Participation in Everyday Life

A higher degree of participation increases independence and social inclusion, especially for people with disabilities (Simeonsson et al., 2001). Participation is a complex multidimensional construct, that is discussed and applied as both a process and an outcome (Granlund, 2013; King, 2013). Participation has two conceptual roots; within sociology and developmental psy-chology. Both of these roots relate to functioning within a context: sociology and developmen-tal psychology (Granlund, 2006). Participation that is based on sociological roots, focuses on the availability of the access to everyday activities and describes participation as equal to the frequency of attending the same activities as others. Participation based on the psychological root focuses on the intensity of the involvement or engagement within an activity and whether the environment is accommodated to a child and accepted by the child (Badley, 2008). Attend-ing is defined as ´beAttend-ing there´ and can be measured in the frequency of attendAttend-ing and/or the range of different activities. The term `involvement` is often used synonymous with ´engage-ment´ to describe the participation experience (Imms et al., 2017). Involvement might include elements of motivation, persistence, and social connection (Imms et al., 2016).

3.2 Five A’s of Participation

Since participation can be focused on the availability of the access to everyday activities, whether the environment can be accommodated to the child, and if a child is accepting this accommodation, the five A’s of participation will be used as a theoretical framework in this systematic literature review (Maxwell & Granlund, 2011). Originally the five A´s consisted of four A´s. The four A´s were first introduced by Tomaševski (2001). The four A´s contained:

11

availability, accessibility, acceptability, and accommobility . The fifth A that was added is af-fordability (Maxwell & Granlund, 2011).

The five A’s are described as the following: Availability, describes the objective possibility to engage in a situation. In terms of services it refers to the provision of facilities or resources (Maxwell & Granlund, 2011). For this systematic literature review this means the variety of applications that are available for these children. Accessibility describes if you can, or perceive that you can, access the context for the situation (Maxwell & Granlund, 2011). Therefore, this systematic literature review will look deeper into how applications can enhance the accessibility in society for these children. Affordability covers the financial constraints and if the amount of effort in time and energy is worth the return to engage in the situation (Maxwell & Granlund, 2011). Therefore, the focus will be on how affordable these applications are, for these children, concerning money, time and energy. Accommodability describes if a situation can be adapted to the needs of the child (Maxwell & Granlund, 2011). Thus, how applications can be adjusted to match the special needs of these children. Acceptability covers the acceptance of people, or the presence of a person, in a situation (Maxwell & Granlund, 2011). Therefore, the focus will be on how willingly these children are in using these application. Figure 1 shows that the two aspects of participation (frequency and intensity of involvement) exist in a spectrum of partic-ipation related to the five A´s (Simeonsson et al., 2001).

Figure 1 Environment dimensions of opportunity as a proposed measure of participation (Maxwell & Granlund, 2011, p 255)

3.3 Rationale

Participation is a basic human right (UN General Assembly, 2020). Even though participation is proven to lead to positive outcomes (Bright et al.,2015) children with disabilities are still at risk of being excluded from participating (Chadwick et al., 2013; Kennedy et al., 2011). Being able to participate in everyday life activities such as personal care, grocery shopping, and com-munication will lead to greater independence and increase the child’s ability to take initiatives

12 and develop further abilities (Cannella et al., 2005). Children with neurodevelopmental disabil-ities (such as ASD and ID) can experience difficulties in social interactions, planning, abstract thinking, and learning form experiences (APA, 2013). Nowadays, more individuals with disa-bilities take advantage of the technology to increase their ability to be independent in livings skills and thereby decrease their reliance on others (Ayres et al., 2013; Mechling, 2011). Tech-nologies can be used by these children, provided that they receive ongoing support such as training and technical adaption (Darcy et al., 2016). Thus, it is important to study what appli-cations that are available to enhance participation and how these appliappli-cations accommodate to the special needs of these children.

3.4 Aim and Research Questions

The aim of this systematic review is to explore how applications can facilitate participation in society for children/adolescents (aged 7-21 yrs) with ASD or ID.

The following research questions were formed to guide the research:

1. In what areas are applications available to support participation in society?

2. How can applications be adjusted (accommodate) to these children’s special needs? 3. In which extent do applications enhance these children’s accessibility to participate in

society?

4. To what extent do these children have to put in money, time and energy (affordability) in order to use these applications?

5. In what way do these children accept (acceptability) using the application?

4 Method

4.1 Systematic literature review

The present study is a systematic literature review. A systematic review is transparent in the reporting of its methods, so others can replicate the process (Grant & Booth, 2009). A literature review is characterized by clearly stated questions which it aims to answer, a strictly transparent method for the search and collection of research, a defined inclusion and exclusion criteria and quality assessment criteria (Jesson et al., 2011).

13

4.2 Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in February 2021. For the search, the follow-ing databases were used: CINAHL, Web of Science, PsycInfo, ERIC and MEDLINE. These da-tabases were selected, because they proved literature in focusing on behavioural and social sci-ences and psychology.

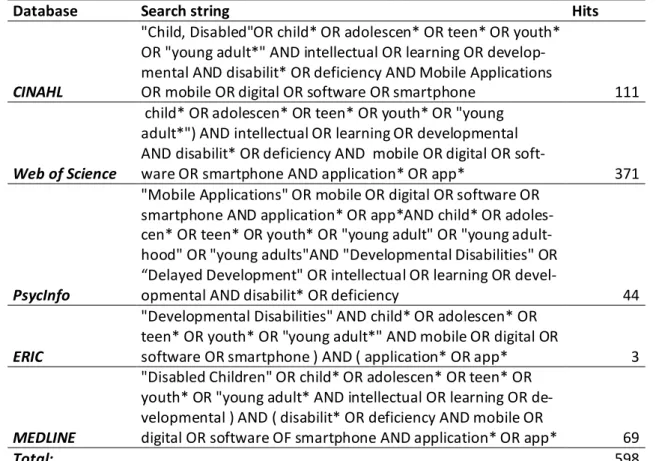

Together with a librarian from Jönköping University, a first search in CINAHL was performed. In order to make the search string, the Thesaurus was used in CINAHL for “disabilities”. For the rest of the search string (see table 1) the suggestions that CINAHL gave were used (e.g. Mobile Applications OR mobile OR digital OR software OR smartphone). The search string that was used in CINAHL, was also used in Web of Science and MEDLINE. For the other databases (PsycInfo and ERIC), the Thesaurus and the automatic suggestions were used as well. Table 1 Presentation of used search strings and related hits

Database Search string Hits

CINAHL

"Child, Disabled"OR child* OR adolescen* OR teen* OR youth* OR "young adult*" AND intellectual OR learning OR develop-mental AND disabilit* OR deficiency AND Mobile Applications

OR mobile OR digital OR software OR smartphone 111

Web of Science

child* OR adolescen* OR teen* OR youth* OR "young adult*") AND intellectual OR learning OR developmental AND disabilit* OR deficiency AND mobile OR digital OR

soft-ware OR smartphone AND application* OR app* 371

PsycInfo

"Mobile Applications" OR mobile OR digital OR software OR smartphone AND application* OR app*AND child* OR adoles-cen* OR teen* OR youth* OR "young adult" OR "young adult-hood" OR "young adults"AND "Developmental Disabilities" OR “Delayed Development" OR intellectual OR learning OR

devel-opmental AND disabilit* OR deficiency 44

ERIC

"Developmental Disabilities" AND child* OR adolescen* OR teen* OR youth* OR "young adult*" AND mobile OR digital OR

software OR smartphone ) AND ( application* OR app* 3

MEDLINE

"Disabled Children" OR child* OR adolescen* OR teen* OR youth* OR "young adult* AND intellectual OR learning OR de-velopmental ) AND ( disabilit* OR deficiency AND mobile OR

digital OR software OF smartphone AND application* OR app* 69

Total: 598

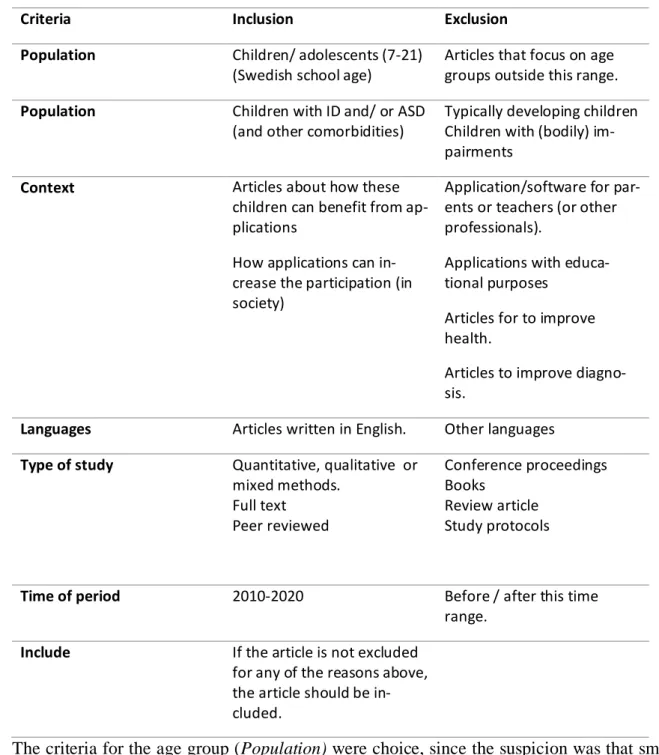

4.3 Selection criteria

The first step in the selection process, was formulating inclusion and exclusion criteria, that were related to the aim of this research. The articles were selected in accordance with the in-clusion and exin-clusion criteria (see table 2).

14 Table 2 PICO

Criteria Inclusion Exclusion

Population Children/ adolescents (7-21) (Swedish school age)

Articles that focus on age groups outside this range. Population Children with ID and/ or ASD

(and other comorbidities)

Typically developing children Children with (bodily) im-pairments

Context Articles about how these children can benefit from ap-plications

How applications can in-crease the participation (in society)

Application/software for par-ents or teachers (or other professionals).

Applications with educa-tional purposes

Articles for to improve health.

Articles to improve diagno-sis.

Languages Articles written in English. Other languages Type of study Quantitative, qualitative or

mixed methods. Full text Peer reviewed Conference proceedings Books Review article Study protocols

Time of period 2010-2020 Before / after this time range.

Include If the article is not excluded for any of the reasons above, the article should be in-cluded.

The criteria for the age group (Population) were choice, since the suspicion was that smaller children will use devices for other activities than to increase participation (e.g. playing games or watching videos) or, that they will not own their own devices yet. This research focus on ASD and ID, therefor this focus population was chosen, however it is possible that children with ID or AD have other comorbidities, those should be included as well. For the context, this research focus on applications to enhance participation. Therefore applications for with an ed-ucational purpose (e.g. to teach a specific school subject), helping improving diagnosis or im-proving health were excluded from this research. Since the author of this research is Dutch, but

15 the three other researches that helped conducting the screening, are Swedish, the language was set on English. So that all the reviewers could read the articles.

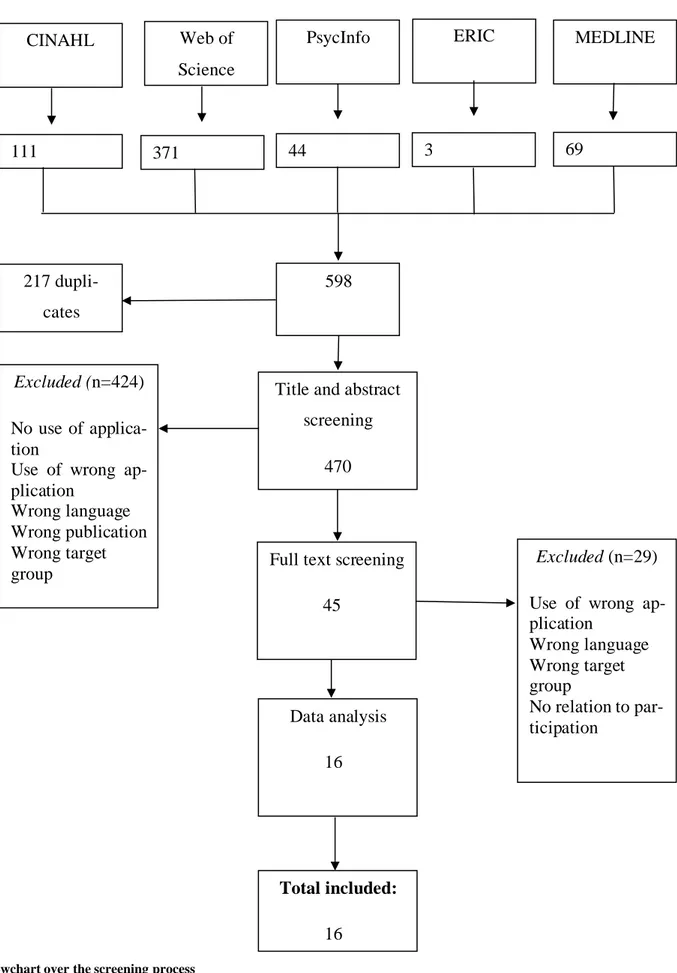

4.4 Selection process

After the selection criteria were made the screening started with the title and abstract screen-ing. To do so, the articles were imported to Rayyan. Rayyan is an online tool that is specifi-cally developed to expedite the screening of abstracts and titles (Ouzzani et al., 2016). After importing the 598 articles, a duplicate check was conducted and 217 duplicates were found. After removing the 217 duplicates, 470 articles were left for the title and abstract screening process. The numbers do not ad up, since some articles had three or even more duplicates and only one version was kept. The screening process was conducted in Rayyan. For the title and abstract screening, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were taken into consideration. Since there were four researchers for the screening, the articles were divided. The reviewers were split up in pairs and the 470 articles were divided over the pairs. The reviewers had a week to include or exclude the articles in Rayyan. After that a meeting was hold to discuss the articles that were labelled “conflict” and “maybe” in Rayyan. During this meeting 45 articles were chosen for the full text screening. The articles were divided over the four reviewers (who worked in pairs) so all the articles were read by two reviewers to prevent from bias. When reading the article in full text the focus mostly were on: is it really an application that is

de-scribed in the article, is this application for children/adolescents and what is the age group.

After the full text screening, 16 articles were selected. The other articles were excluded due to wrong language, wrong target group, wrong application or not focussed on participation. Hereafter, an extraction protocol was made (see appendix 1) where the focus was on the re-search design, the diagnose of the participants and how the application enhanced the five A’s. An overview of the screening process is presented in Figure 2.

16

Flowchart

Figure 2 Flowchart over the screening process

CINAHL Web of Science

PsycInfo ERIC MEDLINE

111 371 44 3 69

598 217

dupli-cates

Title and abstract screening

470

Excluded (n=424)

No use of applica-tion

Use of wrong ap-plication

Wrong language Wrong publication Wrong target

group Full text screening

45

Excluded (n=29)

Use of wrong ap-plication Wrong language Wrong target group No relation to par-ticipation Data analysis 16 Total included: 16

17

4.5 Peer review

Four researchers were included in the screening process. Every title and abstract, as well as the full text screening, were done by two researchers to strengthen the reliability of the study and to reduce bias. During this process, the researchers used the extraction protocol (appendix 1). When there were questions regarding an article, the persons within the pair tried to clarify the questions. If they could not solve it, the questions were raised with the other two researchers as well and discussed until consensus was researched.

4.6 Data extraction

Relevant information that could be related to the aim and the research questions were extracted using an extraction protocol. In the protocol, the focus was on the aim and research questions, which research design was used, amount of participants, how many male and female partici-pants, the diagnosis of the participants and how the applications used in the study enhanced participation, according to the 5 A´s. The author for this thesis took the overall responsibility of reading all the articles carefully and once again went through the data extraction protocol to carefully ensure that all the date met the requirements.

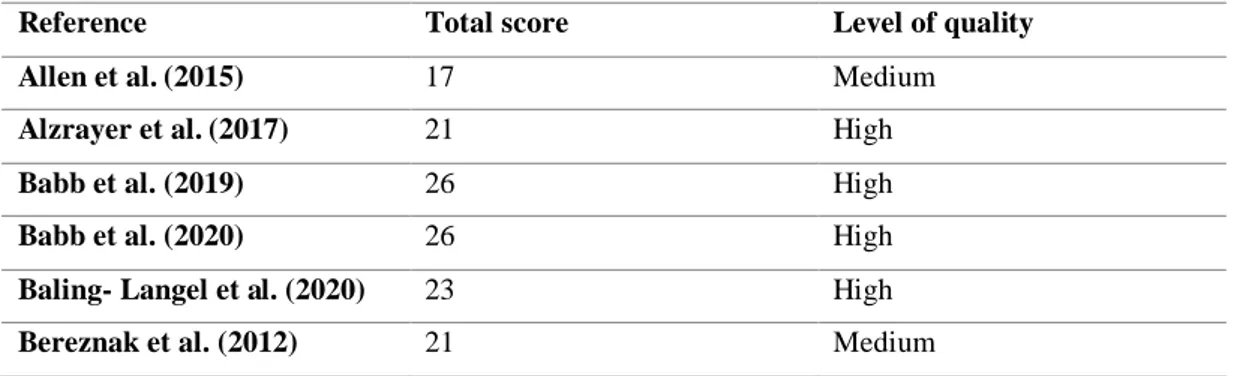

4.7 Quality assessment

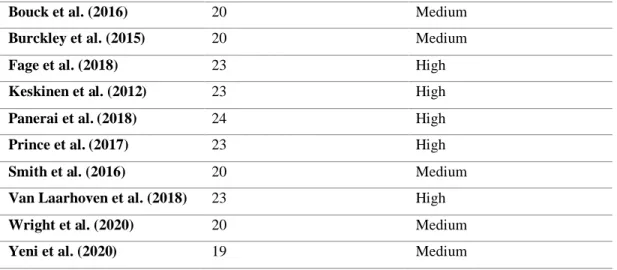

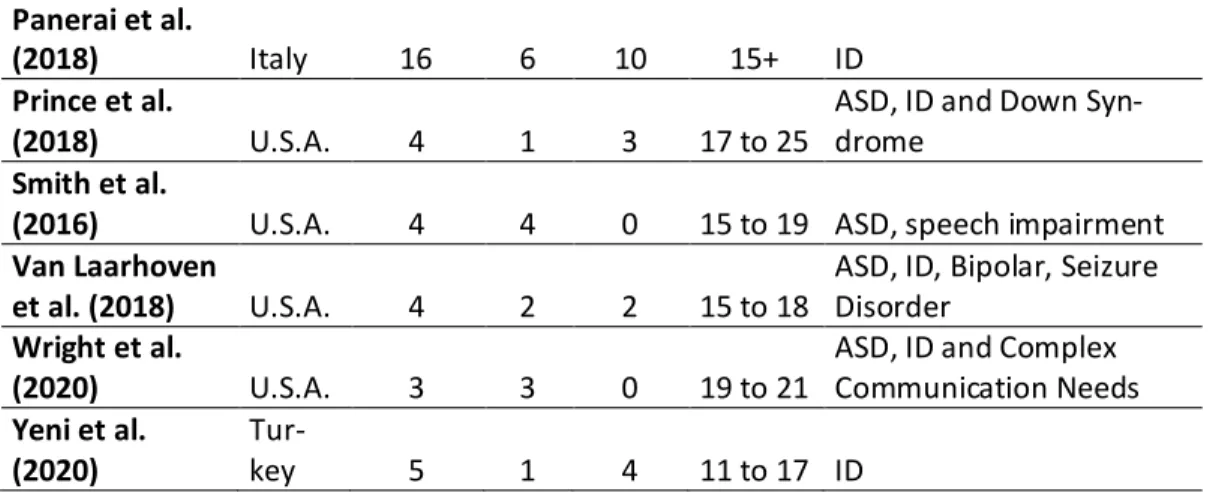

The “Critical Review Form - Quantitative Studies” from Law, et al. (1998) was used to assess the quality of the studies. The form was adjusted, so it would better fit with the aim and re-search questions. See appendix 2 for the form. Different factors were assessed such as: aim of the study, methods used, ethical considerations and the practical implications. The questions were scored from 0 point to 2 points, where 0 points stood for “None or unknown”, 1 point for “ Partial” and 2 points for “Adequate” (Auperin et al., 1997). For each article, the points were added up and ranked as Low (0 to 12 points), Medium (13 to 20 points) and High (21-26 points) quality according to the points. In table 3 an overview of the scores are presented. Table 3 overview of the quality score

Reference Total score Level of quality

Allen et al. (2015) 17 Medium

Alzrayer et al. (2017) 21 High

Babb et al. (2019) 26 High

Babb et al. (2020) 26 High

Baling- Langel et al. (2020) 23 High

18

Bouck et al. (2016) 20 Medium

Burckley et al. (2015) 20 Medium

Fage et al. (2018) 23 High

Keskinen et al. (2012) 23 High

Panerai et al. (2018) 24 High

Prince et al. (2017) 23 High

Smith et al. (2016) 20 Medium

Van Laarhoven et al. (2018) 23 High

Wright et al. (2020) 20 Medium

Yeni et al. (2020) 19 Medium

See appendix 3 for an overview of the different study designs and outcomes of the studies. Further also the five A´s of participation (Maxwell & Granlund, 2011) were used to extract the data, since the research questions are based on those five A´s. in table 4 an overview of which A was represented in which study.

Table 4 Studies related to the 5 A´s

Author Availabil-ity Accomobility Afforda-bility Accessibility Acceptabil-ity Allen et al. (2015) X X X X Alzrayer et al. (2017) X X X Babb et al. (2019) X X X Babb et al. (2020) X X X

Baling- Langel et al. (2020) X X X X Bereznak et al. (2012) X X X X Bouck et al. (2016) X X X X Burckley et al. (2015) X X X X Fage et al. (2018) X X X

19 Keskinen et al. (2012) X X X X Panerai et al. (2018) X X X Prince et al. (2017) X X X X Smith et al. (2016) X X X Van Laarhoven et al. (2018) X X X X Wright et al. (2020) X X X X X Yeni et al. (2020) X X X X 4.8 Ethical Considerations

While conducting a research, there are several ethical issues that need to be taken into consid-eration. These issues contain for instance obtaining an informed consent, doing no harm (be-neficence), and respecting the anonymity, confidentiality and privacy of participants (Fouka & Mantzorou, 2011). Even though there is no sensitive or personal data collected from participants in a systematic literature review, the reviewer should consider perspectives of previous authors and participants of original studies (Suri 2020). For this specific case it should be taken into consideration that children with ID are a vulnerable group while examining studies and writing up the results in this review (Oliver 2020). It should be noticed, that only in Allen et al. (2015) two authors had financial benefits from sale of the application.

However, nine of the 16 studies mentioned they had an ethical approvement (Allen et al., 2015; Alzraye et al., 2017; Babb et al.,2019; Babb et al.,2020; Bouck et al., 2016; Fage et al., 2018; Panerai et al.,2018; Prince et al., 2017; Van Laarhoven et al., 2018). Furthermore, eight articles out of the 16 articles mentioned they had collected consents from the legal guardians of the participants (Allen et al., 2015; Alzrayer et al., 2017; Babb et al.,2019; Babb et al.,2020; Burck-ley et al., 2015; Panerai et al.,2018; Prince et al., 2017; Van Laarhoven et al., 2018). Some (n=5) of the articles mentioned specifically that they had consents from the participants as well (Babb et al., 2020;Bouck et al., 2016; Fage et al., 2018; Van Laarhoven et al., 2018; Prince et al., 2017). Only six of the studies do not mention ethical considerations (Baling- Langel et al., 2020; Bereznak et al., 2012; Keskinen et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2020; Yeni et al.,

20 2020). However three of this studies mention that their participants were selected by the teacher or program coordinator (Baling- Langel et al., 2020; Bereznak et al., 2012; Wright et al., 2020) and the other three studies asked feedback from the parents (legal guardians) of the participants (Keskinen et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2016; Yeni et al., 2020).

5 Results

5.1 Characteristics of Included Articles

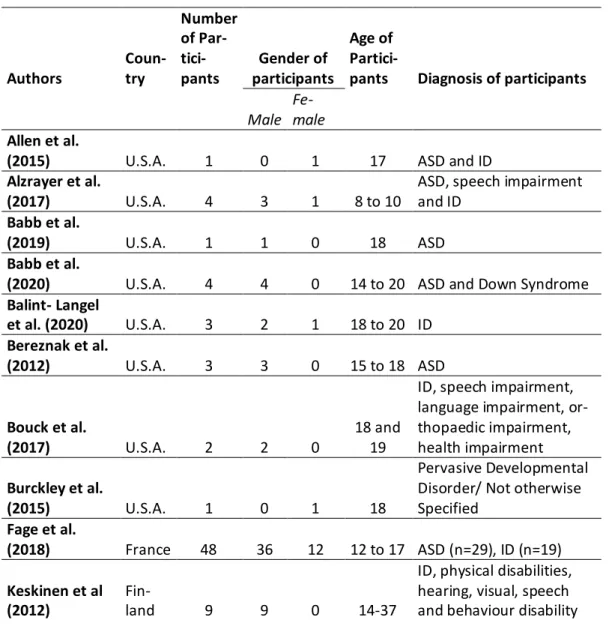

All the studies were peer reviewed and published between 2010-2020. Most of the articles were from the USA. An overview of the general characteristics of these studies (e.g. authors, country, and more information about the participants) are found in table 5.

Table 5 overview characteristics

Authors Coun-try Number of Par- tici-pants Gender of participants Age of

Partici-pants Diagnosis of participants

Male

Fe-male

Allen et al.

(2015) U.S.A. 1 0 1 17 ASD and ID Alzrayer et al.

(2017) U.S.A. 4 3 1 8 to 10

ASD, speech impairment and ID

Babb et al.

(2019) U.S.A. 1 1 0 18 ASD

Babb et al.

(2020) U.S.A. 4 4 0 14 to 20 ASD and Down Syndrome Balint- Langel et al. (2020) U.S.A. 3 2 1 18 to 20 ID Bereznak et al. (2012) U.S.A. 3 3 0 15 to 18 ASD Bouck et al. (2017) U.S.A. 2 2 0 18 and 19

ID, speech impairment, language impairment, or-thopaedic impairment, health impairment Burckley et al.

(2015) U.S.A. 1 0 1 18

Pervasive Developmental Disorder/ Not otherwise Specified Fage et al. (2018) France 48 36 12 12 to 17 ASD (n=29), ID (n=19) Keskinen et al (2012) Fin-land 9 9 0 14-37

ID, physical disabilities, hearing, visual, speech and behaviour disability

21 Panerai et al.

(2018) Italy 16 6 10 15+ ID Prince et al.

(2018) U.S.A. 4 1 3 17 to 25

ASD, ID and Down Syn-drome

Smith et al.

(2016) U.S.A. 4 4 0 15 to 19 ASD, speech impairment Van Laarhoven

et al. (2018) U.S.A. 4 2 2 15 to 18

ASD, ID, Bipolar, Seizure Disorder

Wright et al.

(2020) U.S.A. 3 3 0 19 to 21

ASD, ID and Complex Communication Needs Yeni et al.

(2020)

Tur-key 5 1 4 11 to 17 ID

5.2 Areas in which the applications were available

The identified articles described different applications that are used in a variety of focus areas. Of the identified articles, 11 focused on Living skills” which meant that the children/adolescent were supported with different tasks for example ordering in a restaurant, requesting skills and vacuum cleaning. Five of the identified articles focused on “Vocational activities”, which in-cludes to support the participants to participate in vocational settings for example putting books away and making copies. Two articles focused on “planning events” which supported the par-ticipants to plan and attend events. In table 6 an overview of the different focus areas, the spe-cific tasks, name of the applications and the authors.

Table 6 Overview focus areas

Focus areas Specific task(s) Authors Ordering in a restaurant and paying in a shop. Allen et al. (2015)

requesting a toy/activity Alzrayer et al. (2017) Cooking, doing laundry Bereznak et al. (2012)

Cooking Smith et al. (2015)

Burckley et al. (2015)

Groceries Bouck et al. (2017)

Living skills

Navigating to and in the classroom, communica-tion, identify emotions, orientation in social

situ-ations Fage et al. (2018)

taking medications, preparing a suitcase,

grocer-ies Panerai et al. (2018)

Communicate with others Keskinen et al. (2012) Using public transport, taking the bus, getting

off at the right stop. Prince et al. (2018)

Vacuum cleaning Yeni et al. (2020)

Checking books, put books away Babb et al. (2019)

Packing food backpacks Babb et al. (2020)

22

Vocational Setting a conference room

Van Laarhoven et al. (2018)

skills Preparing a boardgame and Smith et al. (2015) different office tasks such as; preparing a

let-ter/package and sort paperwork/office supplies

Planning events Scheduling and attending meetings

Balint- Langel et al. (2020)

Scheduling and attending meetings, plus addi-tional tasks (such as: buy the book in the

bookshop) Wright et al. (2020)

5.3 How the applications were accommodated to the child’s special needs.

The identified articles used different strategies to accommodate to the participants needs. Out of the 16 identified articles, nine used video instructions to show the participants how to per-form the tasks (Allen et al., 2015; Babb et al., 2019; Babb et al., 2020; Balint- Langel et al., 2020; Bereznak et al., 2012; Burckley et al., 2015; Bouck et al., 2015; Prince et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2015; Van Laarhoven et al., 2018; Wright et al., 2020; Yeni et al., 2020 ).

Some of these studies (n=2) also besides the video instruction also used audio and picture prompting (Burckley et al., 2015; Bouck et al., 2017). An example of this is from Bouck et al. (2017) were they used the picture prompts, audio prompts, and the video prompts to their the participants how to do the groceries. Prior to the participants visit, the researcher would go to the grocery store to record the video. In the video the researcher would verbally state each product and aisle number, walking through the store, show the aisle number, and select the grocery items. The participants could watch the video while doing the groceries. The aim of this study was to see which intervention was the most effective in increasing independence and with which intervention the participants selected the most correct items.

Most of the articles (n=11) used steps to teach the participants how to use the application (Al-len et al., 2015; Alzrayer et al., 2017; Babb et al., 2019; Babb et al., 2020; Balint- Langel et al., 2020; Bereznak et al., 2012; Burckley et al., 2015; Bouck et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2015; Van Laarhoven et al., 2018; Yeni et al., 2020). As an example, in Balint-Langel et al. (2020) the participants were in eight steps taught how to use, the specially designed, application. A mnemonic of CALENDAR was used where the child by going through the eight steps learned was taught how to use the application. See appendix 4 for the example of the mnemonic.

23 Another example is Alzrayer et al. (2017), the application guided and supported the children in how to request something (e.g. a toy or an activity). They adjusted the application to the pref-erences of each participant. The application had three pages of symbols where the first screen had one symbol for “I WANT”. Touching the symbol resulted in production of speech saying “I want”, and then turned to the second screen. This screen showed a symbol with “ACTIVI-TIES”. Selecting this symbol, would lead the participant to the third screen that displayed pre-ferred items and activities.

However, three of the studies did not specifically mention how they taught the participants how to use the application (Fage et al., 2018; Panerai et al., 2018; Keskinen et al., 2012).

It is not mentioned in the studies if the applications were especially developed by the re-searchers. However, some of the studies (n=4) used common applications, such as Goolge maps or Video application (Bereznak et al., 2012; Prince et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2015; Wright et al., 2020). As an example, in the study by Prince et al. (2018) the participants were taught in different steps how to use Google Maps, for using public transportation (e.g. plan-ning the trip, getting on the bus, and getting of the bus). They learned how to get the phone, then navigate in the phone to find the application, how to fill in the starting point and destina-tion, how to select the bus opdestina-tion, and how to start navigating.

5.4 The effect of the applications on these children´s accessibility in society

Living skills

Out of these 16 identified articles, 10 studies targeted living skills, five (Allen et al., 2015; Bereznak et al., 2012; Burckley et al., 2015; Bouck et al., 2017; Panerai et al., 2018) showed that there was some effect in performing the task independently while using the application. There is a wide variation in performing the tasks correctly in maintenance/ generalization phase (40% to 100% correct performance). Four (Alzrayer et al., 2017; Prince et al.,2017 Smith et al., 2015; Yeni et al., 2020) of the studies showed a high effect in performing the task independently. The results showed that the independently performing the tasks went up to 85-100% in maintenance/ generalization phase. In two studies (Fage et al., 2018; Keskinen et al., 2012) is it more difficult to interpret the results in a “high” or “some” percentage, as

24 these studies are focused on socio-emotional development, and the results were presented dif-ferently. However, the results from both studies indicated that the applications were useful and increase socio-emotional behaviour.

Even though all the studies showed an increase in independently performing the different tasks, some of the studies showed a smaller effect than others. For example, in Allen et al. (2015), the participants were taught how to ask for help in the store (to find an item), how to pay the items and how to order in a fast food restaurant by looking at homemade videos. The participants improved their performance in doing these tasks after watching the instruction video. They observed the participant in “real life” settings, were the correct responses went up from 40% to 80% and 90%. Further, Bouck et al., 2017; Burckley et al., 2015; Panerai et al., 2018 describe how participants were taught how to do grocery shopping. In Burckley et al. (2015), the Book Creator™ application was used to provide picture cues and video instruc-tions to teach the participant (n=1) to independently do groceries. The parents and educational staff reported that there were some improvements in the participant’s shopping skills. In Bouck et al. (2017) video prompts, audio prompts, and picture prompts were used in order to support the participants to independently do groceries. The participants (n=2) preformed best when using the video prompts. They were able to use the videos to walk to the right aisle numbers and select the correct items. In Panerai, et al. (2018). The application consisted of different phases, a phase in the kitchen (to determine the shopping list), the second phase cludes a supermarket shelf with different products and a shopping card, the third phase in-cludes the cash counter to pay. The results of their research shows that there was a significant increased amount of correct responses, while the total execution time decreased (Supermarket p <0.001). From the 10 studies that focused on living skills two studies focused cooking as a task to teach the participants (Bereznak et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2015). Where Bereznak et al. (2012) showed a high result and Smith et al. (2015), showed some results in their study. In Smith et al. (2015) the participants were taught how to cook, using video instructions. None of the participants (n=4) were able to perform the task by themselves prior to the intervention. Almost all participants (n=3) performed the task by using the self-instruction (the videos on the device). Only one participant, did not possess the motor skills to navigate through the phone, and therefore needed help from an adult. In Bereznak et al. (2012), an iPod application was used to watch the instruction videos for cooking (making noodles), as well as how to use a washing machine and a vocational task (making copies). In this study the participants were able to perform a few steps prior to the intervention. One participant was not able to perform

25 the task, while implying the intervention. Two other studies that showed high results were Alzrayer et al. (2017) and Yeni et al. (2020). In Alzrayer et al. (2017) they used the Prolo-que2Go application to teach children (age 8-10) to request a toy or an activity. Two of their participants (n=4) were quickly able to use the application by themselves. The other two par-ticipants needed additional training sessions, before being able to use the application. In Yeni et al. (2020), they taught the participants how to use a vacuum cleaner. The parents (of the participants) had not previously offered them the opportunity to use the vacuum cleaner at home. With help from the application, the participants were able to use the vacuum cleaner. By preforming this task, like their family members do, they recognized themselves as capable individuals. One these identified articles focused on teaching the participants how to use pub-lic transportation. In Prince et al. (2017) the participants (n=4), with IDD, were taught to use Google Maps to take the bus. Three of the participants learned how to use public transporta-tion independently by using the applicatransporta-tion.

Further in Keskinen et al. (2012) they developed a communication app, SymbolChat to sup-port people with ID to communicate with each other (and their caregivers) over the internet. The research showed that the participants were able to communicate with each other using the application. In Fage et al. (2018), multiple applications were developed. The applications fo-cused on different areas and tasks. So was there a routine application to support the children to find their way to the classroom, a communication application that focused on the verbal communication within a classroom, an emotional regulation application to support the chil-dren with emotion regulation to identify their own emotions, and socio- cognitive remediation

application(s) that support the child with recognizing the emotions of others. The results

sug-gested significant benefits in terms of socio-cognitive function for both groups (children with ID and children with ASD), however the impact of the application was bigger on children with ASD.

Vocational skills

From the 16 identified articles, five focused on teaching the participants vocational skills. Out of these identified articles two (Babb et al., 2019; Babb et al., 2020) showed there was some results in increasing independently performing the task. In the intervention phase the percent-age of correct performing the tasks had a wide variation (from 40% to 100%). Three studies (Bereznak et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2015; Van Laarhoven et al., 2018) showed a high result.

26 In the intervention phase the results were between 85% and 100% correct performing the tasks.

The articles that both (Babb et al., 2019; Babb, et al.,2020) showed some increasing in inde-pendently performing the tasks, the EasyVsD application was used. In Babb et al. (2019) the participant performed different tasks in the library (e.g. putting books away, asking for help and telling when he was done). The EasyVsD showed a video of one of the authors preform-ing the tasks in steps. The professional, who normally helped the participant in his vocational tasks, responded in a questionnaire that the intervention was successful in increasing inde-pendents in both the tasks and the communication. In Babb et al. (2020) they taught the par-ticipants (n=4) a different vocational task (packing food backpacks) in a volunteering pro-gram, which was set in an elementary school, next to the school the participants attended. This study showed similar results, where (in this case) the educational professionals valued the outcomes. As a result of the study, the elementary school proceeded the volunteer pro-gram, for more days and with more students, than originally in the study.

The studies that showed high results, different applications were used. So in Van Laarhoven et al. (2018) they used the Go Talk Now application and a PowerPoint presentation. The par-ticipant could use the different prompts (picture/text, audio, video) or no device. The results indicated that all the participants increased their vocational skills by using either the applica-tion or the PowerPoint presentaapplica-tion. Three out of four participants showed an immediate and substantial increase in independent correct responding once they were introduced to the inter-vention. The other participant showed a large increase in the second session. In Bereznak et al. (2012) they used the iPod application on the iPhone. Besides the living skills (making noo-dles and using the washing machine) they also taught the participants to make copies. Their results support the use of an iPhone as effective self-prompting device to teach a vocational skill to adolescents with ASD. Lastly, in Smith et al. (2015) they taught the participants multi-ple vocational skills (e.g. preparing a boardgame, different office tasks such as; preparing a letter/package and sort paperwork/office supplies). The purpose of the study was to evaluate the effects of progressive time delay on the imitation of self-instruction by individuals with ASD when they were presented with untrained tasks. In the baseline phase, none of the partic-ipants were able to independently initiated self-instruction in any of the settings. It took the participants different amount of sessions to master the initiated self-instruction (e.g. one par-ticipant masted this in four sessions, and another in eight sessions).

27

Planning events

From the 16 identified articles, two focus on teaching the participants how to plan events

(Balint- Langel et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2020). The effects of both this studies shown that

the participants perform better after being presented with the intervention. In Balint- Langel et al. (2020), they taught the participants (n=3) to schedule and attend a meeting with the Calen-dar app. It shows that in baseline, the participants could not perform the steps independently, after they were taught to use the application, the results show a high increase of independently preforming the tasks. All their participants were able to use the steps of scheduling an event while using the Calendar application and two of their participants also showed up at their event after scheduling it. As shown, the other participant was also able to use the application to schedule events, so this may indicate that having the skill to schedule an event using the ap-plication, does not always guarantee that these adolescents can independently respond to the prompts. In Wright et al. (2020) they use the MoveUp! application on a smartwatch. They taught the participants (n=3) to schedule different appointments (e.g. checking mailbox, vac-uum floors, deliver envelope, and clean bathroom). None of the participants were able to com-plete any of the tasks independently during baseline (0% comcom-pleted appointments). However, after introducing the intervention two of the participants increased to a 100% independently completion and the other participant to 93%. However, when the intervention was withdrawn, the task completion decreased to 9% and when the intervention was reimplemented again, the completed appointments once again increased to 97%.

5.5 How affordable were these applications

Affordability can be seen through the concepts of money, time and energy. The included studies did not specifically mention how the participants experienced using the application in concept of time and energy. Even though these concepts were not specifically mentioned, information could be extracted from the studies.

5.5.1 Affordability related to the concept of money

The identified studies used different types of applications and devices. Table 7 provides an overview of the different devices used in the studies. Eight studies used an Apple product, five used an Android device (this included the Samsung tablets), three used the participants own device and one study did not mention which (or who´s) devices that were used. Only one study (Bouck et al., 2017) mention how much the devices costed. In this study they used multiple devices, such as an audio device and an iPad. The audio device costed approximately $20-$30

28 and the iPad approximately $400. Beside these devices, a photobook, that consisted pictures of the groceries items and the aisles were also used to help the participants to find the items. The included studies did not mention if the applications were free to download, only Wright et al. (2020) mentioned that the application they used was a free application that was only availa-ble on the smartwatch. In 10 studies they used applications that were especially designed for children with special needs (Allen et al., 2015; Alzrayer et al., 2016; Babb et al., 2019; Babb et al., 2020; Balint-Langel et al., 2020; Fage et al., 2018; Keskinen et al., 2012; Panerai et al., 2018; Van Laarhoven et al., 2018;Yeni et al., 2020). In two studies it is not clearly mentioned if the applications are especially designed (Bouck et al., 2016; Burckley et al., 2015). Further four studies use common applications that are available on the devices (Bereznak et al., 2012; Prince et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2015; Wright et al., 2020).

Beside the devices and the applications, the studies also used furniture, books, etc to be able to perform the practice of the skills. In Allen et al. (2015) they described how a mother made the video instructions together with her daughter (the participant). The mother had created a simu-lated store, in the basement of their own house, to perform and for producing the videos. The simulated store had a toy cash register, shelves and some common items the participant could purchase. Beside the store, the mother also made a simulation of a fast-food restaurant, that included a menu and the same toy cash register.

Table 7 Devices and applications used

Devices used Applications used Author

iPad2 VideoTote Allen et al. (2015)

iPad2 Proloque2Go Alzrayer et al. (2017) Samsung Galaxy Note Pro 7 EasyVsD Babb et al. (2019) Samsung Galaxy Note Pro 7,

sony CX405 Handycam EasyVsD Babb et al. (2020) Mobile phone of the

partici-pants were used (iPhone and

Android) and an iPad Calendar Balint-Langel et al. (2020) iPhone 3, digital camera,

computer for editing iPod app (on an iPhone) Bereznak et al. (2012) Photobook (pictures), iPad,

audiodevice (Olympus DP-10)

Mentioned as: appropiate

application Bouck et al. (2017) iPad2, protective case (Otter

29 iPad (second generation)

Daily routine, School+, Communication app, Emo-tion regulaEmo-tion app, Socio-Cognitive Remediation

apps, Fage et al. (2018)

Not mentioned SymbolChat Keskinen et al. (2018) Tablets of the participants

Medicines, Suitcases,

Su-permarket Panerai et al. (2018) Mobile phone of the

partici-pants Google Maps Prince et al. (2015) iPhone Video app (on an iPhone) Smith et al. (2015)

iPad and HP slate (tablet) The Go Talk Now Van Laarhoven et al. (2018) Android tablet

Sweeping Carpet with

Vac-uum (SCV) Yeni et al. (2019)

5.5.2 Affordability in concept time

In Bouck et al. (2017) the teacher expressed concern about the video prompting system, since she had to make a video, in her own time, each week. Also the students had to carry the tablet with them while doing the groceries, this could be inconvenient since they also had to use a cart. The teacher felt that the audio prompting would be easier to use, since it was easier to carry. In Allen, et al. (2015) they use more than just the devices mentioned in table 6. In their research they observed how a mother made the video instructions with her daughter (the par-ticipant). The mother had created a simulated store, in the basement of their own house, to perform and for producing the videos. The simulated store had a toy cash register, shelves and some common items the participant could purchase. Besides the store, the mother also made a simulation of a fast-food restaurant, that included a menu and the same toy cash register. In the videos the mother would play the role of the clerk. In other words, this asks time from the mother.

5.5.3 Affordability in concept of energy

The participants have to be taught how to use the applications and/or how to navigate through the device. Although it could be possible that once the children/adolescents have been taught to use the video instructions (on the devices), in several tasks, they may be able to independently learn new tasks (Babb, et al., 2019). But before that, this does cost (not only time) but also energy from the child/adolescent as from the person who is teaching them.

30

5.6 How willingly (acceptable) were these children/adolescents in using the apps

Of the 16 including studies, 10 mentioned something about the willingness among the partici-pants to use the application/device. Of these 10 studies, six showed that the participartici-pants were willingly in using the application/device and in the other four the participants were only partly willingly. In Prince et al. (2018) one of the participants did not want to follow the prompts she was taught when using Google Maps, but instead wanted to use own visual environment cues in order to know where to get off the bus. Further, in Bereznak et al. (2012) the participants (n=3) were asked if they were interested in working with the iPhone. The participants re-sponded positive. They choice working with the iPhone over working alone. One of the par-ticipants also responded that he felt “cool” using the iPhone, because his older sister also had one. Their last participant however, seemed frustrated working with the iPhone, due to fine motor difficulties. The instructor stepped in to assist the participant. In Van Laarhoven et al. (2018) one participant chose not to use the device for most of the steps that were required to perform the task (71%) and selected the instruction videos for a small part of the steps (29%), however the participant selected the incorrect icon and preformed the steps incorrectly. The second time the participant worked with the device, he relied more on the instruction videos, which improved his performance. In Keskinen et al. (2012) three (out of nine) participants stated that it was fun that they could use the application to have conversations with someone. Two of the participants reported negative experiences, one participant lacked motivation and the other participant thought it was difficult that he did not knew the symbols and therefore lacked the motivation to use the application. Further in Smith et al., (2015), their participants (n=4) all watch the videos to perform the tasks. One of the participants preformed the task ex-actly how it was performed in the video. Therefore, in the video for collating and stapling pa-pers, there were three sheets of paper and the actor pointed out the number that was shown in the right corner (as a signal how to order the papers). The participant also completed this, non-essential step after seeing the video. In Babb et al. (2019) it was mentioned that the inter-vention was socially appropriate, effective, efficient and that she (the teacher) would like to use the technology again. Burckley et al. (2015) asked the participant´s (n=1) parents and edu-cational staff to fill in a questionnaire to assess their opinions on the goals, procedures and outcomes of intervention. All the respondents felt that the iPad 2 with Book Creator™ was as acceptable as other methods for community instruction and that it is more likely that they will use this application to teach other community skills. Also in Wright et al. (2020) they held a

31 questionnaire, in this questionnaire all the participants agreed that they were interested in us-ing the smartwatch (with the application) again. In Bouck et al. (2017) the teacher expressed concern about the video prompting system, since she had to make a video, in her own time, each week. Also the students had to carry the tablet with them while doing the groceries, this could be inconvenient since they also had to use a cart. The teacher felt that the audio prompt-ing would be easier to use, since it was easier to carry.

However, the devices are not useable for everyone, in Bouck et al. (2017), participants who did not possess the sufficient fine motor skills for operating the tablet (or the audio recorder), were excluded from the research.

6 Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to explore how applications can facilitate participation in society for children/adolescents (aged 7-21 yrs) with ASD or ID. To guide this research aim, research questions, based on the five A´s of participations (Maxwell & Granlund, 2011) were made. the five A´s were described as the following: Availability, describes the objective possi-bility to engage in a situation. In terms of services it refers to the provision of facilities or re-sources. Accessibility describes if you can, or perceive that you can, access the context for the situation. Affordability covers the financial constraints and if the amount of effort in time and energy is worth the return to engage in the situation. Accommodability describes if a situation can be adapted to the needs of the child. Acceptability covers the acceptance of people, or the presence of a person, in a situation (Maxwell & Granlund, 2011).

After a comprehensive literature search, there were 16 articles chosen that addressed the study aim and met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The results show that there are applications available in different areas of focus e.g. living skills, vocational skills, and planning. Most of the applications (n=9) work with video instruction to teach a certain skill in steps to the partic-ipants. It is also common (n=13) that the application is taught in steps from getting the phone, navigating to the phone, to preforming the task step by step.

6.1 Reflection on findings

6.1.1 Availability

The findings of this systematic literature review indicate that there is a wide variation of appli-cations available in different focus areas that enhance participation. The appliappli-cations, that were

32 addressed, supported the participants to participate in different areas important for them in their everyday life. The focus on the areas covered in the applications were: living skills, vocational skills, planning and using public transportation. The applications supported them, for example, to navigate to the classroom, taking medications, ordering in a restaurant, doing groceries, cook-ing, vacuum cleancook-ing, planning and using public transportation. Besides the focus areas ad-dressed in the results, there is a wide variant of applications available to support children/ado-lescents with special needs. Such as the previous mentioned application (Important Information About Me) mentioned to support in a healthcare situations (Jiam et al., 2016). Or the application that helped adolescents to seek social support from their friends and family when they were on their own (Darcy et al., 2016). Or the application Sidekicks! That help children with ASD to learn more socio/emotional skills.

All of these areas combined, show that there is a wide range of applications available. However

availability is not only if there are applications available but also if it is possible for the child

to act and what are the available resources (Maxwell, 2012). It should be noted that just the application alone is not enough to enhance participation, but that these children need additional support (McNaughton and Light, 2013; More & Travers, 2012; Näslund & Gardelli, 2013; Ramsten et al., 2018; Sorbring et al., 2017). This is where the other A´s of participation are shown as well. Even though that there are applications available, that they are available does not automatically lead to increasing of participation.

6.1.2 Accommodability

Previous research has already shown that technology is an effective design for new learning approaches (Bertini & Kimani, 2003) and can be effectively adapted to teach functional daily living skills directly in the community. This also shows in the results in this systematic litera-ture review, where watching video instructions on a device gives these children/adolescents the opportunity to practices the new skills in the “real” environment (Burckley et al., 2015). The devices give the children/adolescents the freedom of movement, while watching a video instruction using an application (Yeni et al., 2019). So, children/adolescents can learn a new task, directly while performing this task.

According to other research (Bidwell & Rehfeldt, 2004), video instruction is an efficient way of giving instruction, in which several learners can benefit at the same time. Also video in-struction may be an effective intervention, because it combines observational learning and im-itation of observed behaviours (Clark et al., 1992).

33 However, technologies alone are not responsible for benefits. The use of tablets or

smartphones in a way that actually contributes to increase independence and participation is the main consideration (Lussier-Desrochers et al., 2017; McNaughton & Light, 2013; More & Travers, 2012). Previous research has highlighted the need to adapt support for these children and adolescents using the technologies (McNaughton & Light, 2013; More & Travers, 2012; Näslund and Gardelli, 2013; Ramsten et al., 2018; Sorbring et al., 2017).

Darcy et al. (2016) concluded that those who get the most out of using mainstream technolo-gies, are those who have significant ongoing support, such as training and technical adaptions. Therefore the applications need to be in line with these children’s needs. A way to accommo-date this is to teach these children/adolescents how to use the application (and preform the task) in steps. This is shown in Balint-Langel, et al. (2020) were they taught their participants to use the application in steps using a mnemonic of CALANDER, were each letter stood for a step the participants needed to perform in order to schedule an event. However there is also a risk in teaching the participants to perform a task in steps. In Smith et al. (2015) it showed that one of the participants also performed unnecessary steps, such as pointing to the right corner (in the video the adults pointed to the corner where a number would appear).

6.1.3 Accessibility

The applications helped to enhance accessibility in the community, by teaching the children with special needs everyday life skills, such as cooking, doing groceries, making copies, using public transportation, planning and attending events, and vacuum cleaning. For example. in Yeni et al. (2020) it showed that the participants felt more as capable individuals, when they could vacuum clean (while using the application). The results from Yeni et al., 2020 are in line with other conducted research and support the suggestion of the effectiveness of educa-tional (mobile) technology use for improving academical, communicaeduca-tional, leisure, and tran-sition skills for individuals with special needs (Burke et al., 2010; Cihak et al., 2010; Fernán-dez-Lopez et al., 2013; Flores et al., 2012; Kagohara et al., 2011; Van Laarhoven et al., 2009). Another research addressed in this systematic literature review, was Van Laarhoven et al. (2018), the findings in this study suggest that independent responding can be increased by us-ing devices with built in decision points (steps), this in agreement with other conducted search done by Mechling et al. (2009, 2010); Mechling & Seid (2011), Further, also the re-sults from Balint-Langel et al. (2020) are in line with other conducted research. The rere-sults suggest that young adults with ID can learn to use (mobile) applications, which may ease a variety of life skill difficulties (Ayres et al., 2013; Kagohare et al., 2013; McMahon et al.,