Implementing Liikumisretsept

(Physical Activity on Prescription) in

Estonian healthcare

Based on the views of Estonian medical professionals

Tarmo Tikk

Sport Sciences: Two-Year Master’s Thesis, IV610G, 30 ECTS Sport Sciences: Sport in Society

VT/2020

Supervisor: Stephen Garland Examiner: Susanna Hedenborg

Abstract

Background: Physical Activity on Prescription (PAP) is a proven way to increase physical activity amongst patients in primary healthcare. Despite the scientific support for the method and the fact that it is being used in several countries (for example Sweden and Finland ), Estonia has not implemented this method in the healthcare system. The aim of the study was to describe Estonian healthcare professionals’ views on Liikumisretsept (Physical Activity on Prescription) and problematize the implementation of Liikumisretsept in the Estonian healthcare system.

Methods: Twelve semi-structured interviews with Estonian medical professionals were conducted: four with family doctors, two with specialist doctors, two with physiotherapists, and two with healthcare managers. The transcribed texts were analyzed using inductive content analysis.

Results: Key findings were that Liikumisretsept was described as a method that helps to support PA as part of the treatment by giving patients clear directions for PA depending on their condition. There is clear support from medical professionals and from the Health Insurance Fund for this method to be implemented in Estonian healthcare. It was found that it is a prescription that every medical professional should know how to prescribe, including physiotherapists. Secondly, main barriers to implementation were identified like lack of awareness, support, education, and the need for better collaboration between all stakeholders. Solutions identified were that there should be educational trainings for medical professionals on how to prescribe Liikumisretsept, promotion of this method through different channels, and having support for Liikumisretsept from national governing bodies like Healthcare Insurance Fund to guarantee the funding for it.

Conclusion: Liikumisretsept is seen as a method to provide individual PA guidelines for patients depending on their condition to raise their physical activity. Awareness about PA should be increased amongst medical professionals to support Liikumisretsept as a suitable treatment option. Educational trainings and supportive collaboration from all stakeholders are needed for successful implementation.

Table of Contents

Abstract ... 2 List of abbreviations ... 5 Glossary of terms ... 6 1. Introduction ... 7 2. Previous research ... 9 2.1. PA promotion ... 10 2.1.1. Physiotherapists ... 12 2.1.2. Physicians ... 132.2. Swedish Physical Activity on Prescription ... 15

2.3. Prescribing PAP ... 18

2.4. Implementation ... 19

2.4.1. Implementation examples ... 20

2.5. Making changes ... 22

3. Healthcare services role in Estonia ... 23

4. Research aim and questions ... 25

5. Theoretical framework ... 27

5.1. Systems approach ... 27

5.2. Implementation science ... 28

5.2.1. Implementation theory ... 29

5.2.2. Organizational readiness for change... 30

5.2.3. Combined theory ... 35

6. Methodology ... 37

6.1. Research design ... 37

6.3. Data collection ... 39

6.4. Data analysis ... 42

6.5. Research quality ... 43

6.6. Scientific, ethical and social considerations ... 45

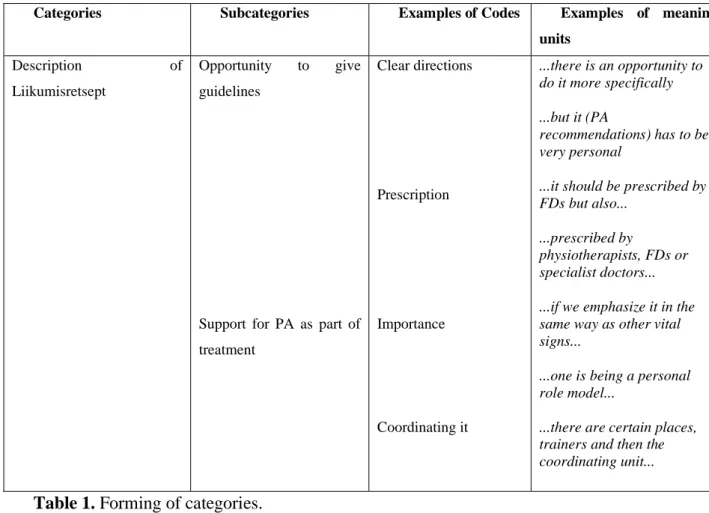

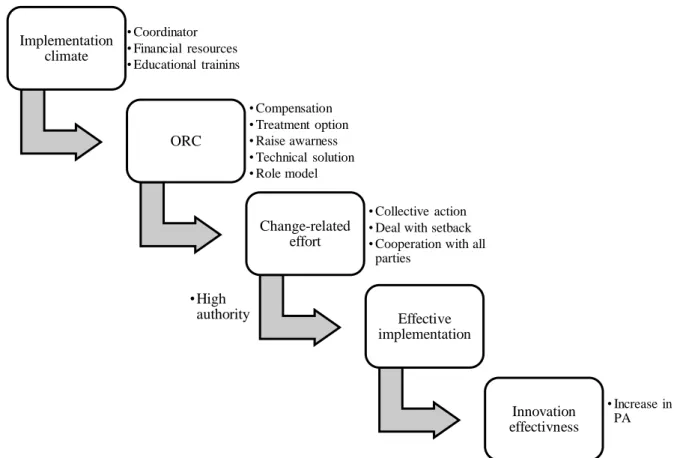

7. Results ... 47

7.1. What Liikumisretsept provides ... 49

7.2. What is needed for the implementation of Liikumisretsept ... 53

8. Discussion ... 59

9. Conclusion ... 66

10. Reflection on the processes ... 67

11. Future Research ... 70

12. References ... 71

13. Appendix ... 82

Appendix 1. The Ask-Assess-Advise structure (Aittasalo et al., 2016). ... 82

Appendix 2. PAPP (Weiner, 2009) ... 83

Appendix 3: Interview consent form ... 84

List of abbreviations

PAP - physical activity on prescription PA - physical activity

PI - physical inactivity

WHO - World Health Organization NCD - non-communicable disease FD - family doctor

SD - specialist doctor PT - physiotherapist HM - healthcare manager QOL - quality of life

EHR - electronic health records

Glossary of terms

Physical inactivity - Achieving less than 30 minutes (PA) per week (Public Health England, 2014)

Physical activity - Any bodily movement produced by the skeletal muscles. The result of this is energy expenditure that can be divided into categories: occupational, sports, conditioning, household, or other active daily activities (Caspersen et al., 1985).

Exercise - Exercise is a certain type of PA that is planned, structured, and done repetitively to improve or maintain physical fitness (Caspersen et al., 1985).

Healthcare professionals - Family doctors, specialist doctors, physiotherapists. Healthcare manager - Managing daily activities and long-term goals for healthcare.

1.Introduction

Maintaining sufficient physical activity (PA) has become more and more difficult as the daily environments have changed significantly in recent years. For example, the distances between homes, workplaces, shops, and places for leisure activities have become greater, and those distances are usually covered by cars (WHO, 2015). This has led to physical inactivity (PI) becoming a public health threat, and PI has become the 4th leading risk factor for global mortality causing 3.2 million deaths per year (Lim et al., 2014). With more and more people being physically inactive, it has significant implications for peoples' health and the prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCD) like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer. PI is responsible for approximately 21-25% of breast and colon cancer burden, approximately 27% of diabetes, and approximately 30% of ischemic heart disease burden (WHO, 2009). It is estimated that out of every ten deaths, six are due to NCDs (WHO, 2004). Since PI has a significant effect on morbidity and mortality, it puts economic pressure on the healthcare systems and wider society (Ding et al., 2016; Wen et al., 2011). Integrating PA promotion into

healthcare is among the seven "best investments" to reduce PI (Lowe et al., 2017), but it is a time-consuming process becoming from inactivity to being physically regularly active, and healthcare strives for efficiency (Joelsson et al., 2017).

The challenge is how to take known health and well-being benefits of PA into practical use and make PA a regular treatment and prevention option in the healthcare system (Hellénius & Sundberg, 2011). One option to do that and to get people more physically active is a concept called Physical Activity on Prescription (PAP). In Estonia, it would be called "Liikumisretsept". PAP aims to increase the motivation for PA and the PA level (Lundqvist et al., 2019). It is a concept used in Sweden since 2001 to promote physical activity to prevent and treat lifestyle-related health disorders (Faskunger et al., 2007). The benefit of PAP is that it gives more structured individual guidelines with written advice and/or follow-ups, which increase the patients' PA levels more than just brief oral counseling through changing their lifestyle behavior (Börjesson & Sundberg, 2013).

In 2018 only 9% of Estonians got a recommendation from doctors to increase their physical activity and 2,9% from other medical professionals (National Institute for Health Development, 2018). PAP is a proven method to increase PA by providing counseling on PA and prescribing individually tailored PA recommendations. Since PAP has shown good results in increasing physical activity in Sweden (Kallings, 2008), it is a concept

that could be implemented in Estonian healthcare as well. Both countries share similarities in healthcare structure; for example, both are mainly funded by taxes to provide equal access to healthcare for everyone who needs it (Orrow et al., 2012).

There is a need to increase the PA amongst Estonians since according to WHO, only 42% of adults in Estonia are physically active enough (reaching 150 minutes of moderate-physical activity per week) compared to Sweden (67%) for example where PAP is implemented (WHO 2018). Adding to that, the National Institute for Health Development (2018) found out that only 30% of Estonians spend less than 15 minutes walking or cycling to work, and just 30% spend 15-30 minutes. The same report included that only 7,7% exercise at least 30 minutes 4-6 times a week and 28% exercise 2-3 times. Implementing a similar concept like PAP that would be called "Liikumisretsept" in Estonian healthcare could be a solution to make Estonians more physically active and, through this, improve the quality of like (QOL) like it has done in Sweden (Kallings et al., 2008).

This paper investigates Estonian medical professionals' views on Liikumisretsept and addresses the challenge in the health community that is how to take an intervention like Liikumisretsept and implement it in the Estonian healthcare. More precisely, it will try to get a deeper understanding of the barrier Estonian medical professionals see for the implementation and what are their views on overcoming those obstacles. This is done by conducting interviews with family doctors, specialist doctors, physiotherapists, and healthcare managers.

2.Previous research

Although there is a global consensus that lack of PA is a threat to the people's health, there is not a consensus in healthcare how to achieve a sufficient level of PA (Borjesson & Arvidsson, 2018). PA has been coupled with diet to address obesity rather than being seen as a standalone issue despite the independent health effect of physical activity and physical inactivity (Kohl et al., 2012). Pechter et al. (2012) claim that people do not need to be doing exercise to be active. What it means is that people might think that only exercising with special equipment and under supervision is considered PA, and it might mean they pay less attention to everyday activities like walking, taking the stairs instead of the elevator, leaving the car away from the workplace that can increase everyday PA. Regular physical activity can have several health benefits like reduced body fat, improved cardiovascular health, enhanced bone health, and it can reduce the symptoms of anxiety and depression (WHO, 2010). Additionally, it reduces the risk of stroke, coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, colon, and breast cancer (WHO, 2004, 2009). WHO has estimated that 80% of heart and cardiovascular disease, 90% of non-insulin depended on diabetes, and 30% of all cancer can be prevented by changing lifestyle habits like eating a healthier diet, quitting smoking, and being physically more active (World Health Organization, 2002).

Despite the mentioned benefits of physical activity, 1/3 of people in high-income countries are not active enough (WHO, 2014). To get enough physical activity, adults (18-64 years old) should get at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week. It should be performed in bouts of at least 10 minutes duration. For additional health benefits, the numbers should be doubled. Moderate-intensity activities can be brisk walking or cycling, household chores like gardening or cleaning, manual work, different sports like dancing, swimming, tennis and team sports, jogging/running (McNally, 2015; WHO, 2010).

Muscle-strengthening exercises that involve major muscle groups should be done at least two times a week (WHO, 2010). Moderate-intensity physical activity means that the activity is performed 5-6 on a scale of 0-10 relative to the individual's capacity. Respectively for vigorous-intensity, the numbers are 7-8. Physical activity includes leisure-time physical activity, transportation (walking, cycling), occupational (work), household chores, games, sports, or planned exercises (WHO, 2010). Adults who do not

meet the requirements for physical activity should start by increasing duration, frequency, and finally intensity (WHO, 2010).

2.1.

PA promotion

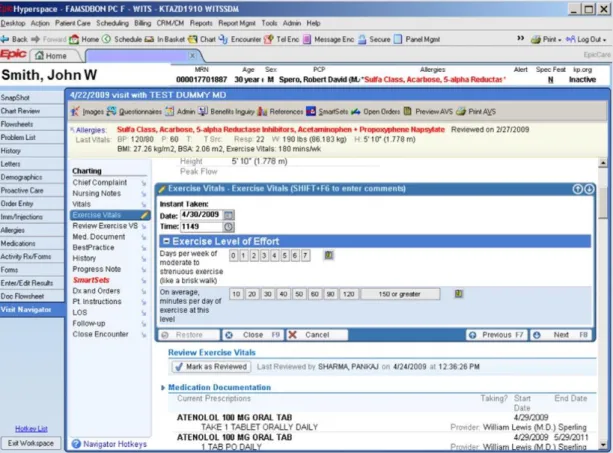

World Health Organization, (WHO, 2015) states that WHO member states should make the promotion of PA by health professionals the norm. Counseling should be included in the standard practice. Depending on the patients' needs, it can be a simple assessment of the level of PA followed by brief advice if necessary or for patients requiring more support. It can be counseling with motivational techniques and goal setting with referral to specialists. A challenge for PA promotion in healthcare settings is the time since, for one visit, doctors generally have only 15-20 minutes. Having patients PA level already on the electronic health records (EHR) (figure 1) can be a time-saving option as the physician has the option to advise the patient about starting, increasing, or maintaining his PA levels. This can be done by asking patients 2-3 questions about their current PA levels at the start of their clinic visit (Sallis et al., 2015). This can lead to more exercise-related activities like physician counseling, prescriptions for exercise, nutrition, and weight loss counseling (Grant et al., 2014). Having PA level in the EHR gives the physician the possibility to see the current PA levels of the patient and advise them on how to optimize their exercise habits (Sallis et al., 2015). In Sweden, FYSS is being planned to work seamlessly with the electronic health record that recommendations pop up as appropriate (Kohl et al., 2012).

Figure 1. Example of PA in EHS (Sallis et al., 2015).

PA promotion has been selected as one of the top priority strategies in the global fight against the NDC epidemic (WHO, 2014). Healthcare setting plays a crucial role in health promotion (Porras et al., 2018) and the promotion of physical activity by health professionals should be the norm (WHO, 2015). Regular contacts with health services provide the opportunity to promote the benefits of a healthy lifestyle (that includes increasing PA) to patients through conversations and by supporting them to take the steps towards it (Public Health England, 2016). Physiotherapists, medical doctors, nurses, or kinesiologists can promote physical activity for primary or secondary prevention of NCDs (Porras et al., 2018).

The healthcare sector can take the lead in six areas in physical activity promotion. These are:

1. Making physical activity part of primary prevention

2. Documenting successful interventions and publishing research 3. Showing the economic benefits of investing into physical activity 4. Connecting relevant policies

5. Promote and exchange information 6. Lead by example (WHO, 2020)

To be able to promote PA, healthcare professionals have to know PA guidelines. For example, in Ireland, only 51% of the physiotherapists knew the state of current PA guidelines (Barrett et al., 2013). They also need to know if the patient is in the risk category and know how to make evidence-based recommendations (Lowe et al., 2017). One of the challenges might be that some physicians do not regard lifestyle issues like PA to be their responsibility and because of that not realizing the potential treatment effects of PA for many patients with NCDs (van Gerwen et al., 2009).

Din et al. (2015) found that physicians who are physically active themselves promote activity during their consultations more, and they are perceived as a more credible source to patients. It was also found that the advice was targeted to individuals whom physicians felt would be motivated to change; for example, it depended on patients' physical appearance, conditions, age/or gender. What makes patients change their PA behavior can be a significant life event or a health crisis such as a myocardial infarction. Having gym classes with people with similar problems can give patients confidence and empower them to modify their behavior instead of going to the regular gym classes (Din et al., 2015).

2.1.1. Physiotherapists

Physiotherapists primarily use non-drug interventions, including exercises and patient counseling, in their treatment. PA counseling is an excellent way for health professionals to discuss lifestyle issues at appointments. Counseling aims to develop the patient's views and skills to support his or her health, well-being, and functional capacity (Walkeden & Walker, 2015). Physiotherapists should take the leadership role in PA counseling among the established health professions since they have prolonged periods within treatment and sessions longer compared to physician sessions. They can build trust with the patients and have the potential to affect their health behavior (Heath et al., 2012).

Dean (2009) suggests that physiotherapists should have a professional and ethical responsibility to make sure that health promotion opportunities are maximally used. It has been found that physical therapists can potentially effectively counsel patients for lifestyle-related health conditions in the short term (McPhail, 2015). Arsenijevic & Groot (2017) found that a large proportion of physiotherapy patients are either overweight or

Lowe et al. (2017) found that 77% of physiotherapists routinely discuss and 68% deliver brief interventions (like making a forward referral) for physical activity; however, only 40% routinely assess physical activity status and 44% sign for further physical activity support. However, O'Donoghue et al. (2014) found that 76% of physiotherapists always assessed PA levels. The difference might come from the fact if a formal or informal assessment is used. The formal assessment would include using General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire to assess the PA level (NHS England, 2008), and informal is just oral assessment. Some of the reasons for not delivering brief interventions might be because lack of time, lack of belief in the effectiveness of interventions, perceived lack of knowledge and a feeling that it is not acceptable to the patient (Hébert et al., 2012; O'Donoghue et al., 2014; Shirley et al., 2010; Walkeden & Walker, 2015).

Lowe et al. (2017) found that despite 88% of physiotherapists were aware of the current PA guidelines, only 16% answered all three questions correctly about PA guidelines. The questions were:

1. How many minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity is recommended per week for adults? (60% answered correctly)

2. How many minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity is recommended per week for adults? (33% answered correctly)

3. On how many days per week is it recommended that adults undertake strength training? (32% answered correctly).

Carstairs et al. (2020) found in their study that clinical consultations are a good opportunity for health professionals (nurses and physicians) to provide PA promotions and interventions. The role of increasing PA should not be limited to health professionals but also individuals, to the larger society and societal norms. This is the method that was used to control the smoking prevalence, and physical activity should learn from it (Kohl et al., 2012).

2.1.2. Physicians

Health professionals are seen as facilitators but not dictators in PA promotion because health professionals have a lot of influence. There is a delicate balance between directing and suggesting in a supportive manner and being too descriptive and prescriptive. Health professionals should provide patients with PA opportunities to look into instead of just saying you should get more exercise. However, the barrier with this is not knowing different local activity physical groups and opportunities and the medico-legal aspect of

referring patients to local activity groups they are not familiar with. The solution to this could be a coordinator who would be available in the local area to whom they could officially refer patients to. This also alleviates the time pressure from health professionals, so they do not have to discuss the specific PA opportunities. Opportunity to meet and exercise together with similar people who are trying to increase their PA would be a potential supportive solution that the broader community could be involved with. For example, in Scotland, they have jog for Scotland program (Carstairs et al., 2020).

Persson et al. (2013) found that general practitioners (GP) know about how important physical activity is, but it takes time to change a treatment strategy from prescribing drugs to replacing or supplementing this with PAP. Prescribing PAP is something that doctors feel uncomfortable doing. It is natural for them to talk about it, but prescribing it is a job for someone else. Also, there is distrust if PAP has enough potential to make a difference. Doctors want clear guidelines and processes for prescribing PAP like there are for pharmacological treatment (Persson et al., 2013). Patients also expect drugs from physicians, and they are not satisfied when they are prescribed exercise (Agadayı et al., 2019). O'Brien et al. (2019) found that doctors are more likely to ask about PA habits from their patients if they place a higher priority on PA counseling in practice and if they feel more confident and competent in helping their patients to achieve behavioral change.

FDs should know the patient's level of physical activity to start the discussion about physical activity, it's impact on health, and encourage patients to be more physically active (Börjesson & Sundberg, 2013). Borjesson & Arvidsson (2018) found that 55 patients (23%) asked for advice from their FD about physical activity. Also, it was found that patients with BMI > 25, patients who considered their health poor, and patients with chronic disease sought advice more often. Healthcare professionals must be motivated to deliver lifestyle advice. This can be done by a behavioral change in physicians if PA treatment is given similar status as conventional medical treatment (Börjesson & Sundberg, 2013)

If physical activity promotion is added into the routine care of primary care consultation, different concerns like skills, priority settings and time constraints emphasized by physicians need to be considered. Training in physical activity

advice-2.2.

Swedish Physical Activity on Prescription

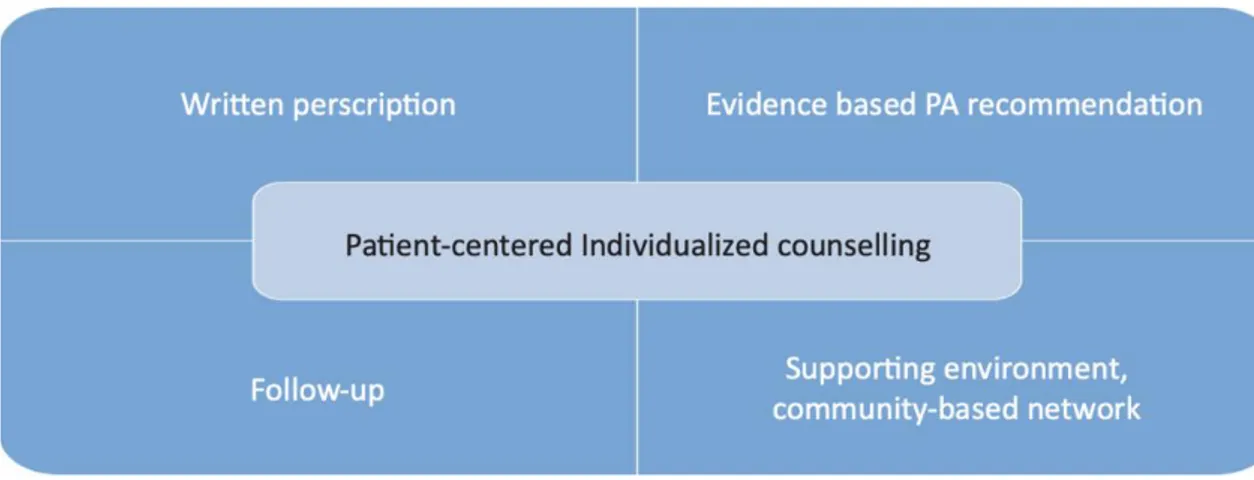

Swedish Physical Activity on Prescription (SPAP) can be used to treat or prevent over 30 diseases or conditions, and it is implemented in the Swedish healthcare system. It is mostly used in primary care (Professional Associations for Physical Activity—Swedish National Institute of Public Health, 2010). It has five components: 1) structured consultation, 2) written individual prescription of physical activity based on the goals of the patient and the expertise of the health professional, 3) scientific guidance how physical activity can prevent and treat health conditions, 4) follow-up of the prescription, 5) collaboration between healthcare services and sport centers (figure 2) (Kallings, 2008). SPAP also takes into account which disorder to treat, potential or real barriers to exercise, possible contradictions, and current diseases and medications (Börjesson & Sundberg, 2013).

Figure 2. Overview of the SPAP method (Kallings, 2008).

Research has shown that (SPAP) increases physical activity in patients in primary healthcare (Kallings et al., 2008). Additionally, it has shown to reduce sedentary time, body mass index and systolic blood pressure, improve health-related QOL, improve body composition, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease (Kallings, 2008; Kallings et al., 2009; Lundqvist et al., 2017; Orrow et al., 2012; Petrella et al., 2003; Rödjer et al., 2016). Sweden uses a reference book called "Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of disease (FYSS) when prescribing SPAP (Professional Associations for Physical Activity—Swedish National Institute of Public Health, 2010). This book collects all the evidence for treatment with different diseases, including the mechanisms, most effective dosages, side-effects, and contradictions for PA (Börjesson & Sundberg, 2013).

Before launching SPAP, a survey was carried out that showed that 9 out of 10 patients in the primary care waiting room preferred physical activity over drug treatment if the outcome was the same. SPAP was created in 2001 based on a pilot education program. In this program, Swedish Health Care introduced pedometers as a tool for intervention and evaluation for patients who decide to follow the prescription on their own. The prescription can also be followed by visiting local SPAP providers like gyms, sport clubs, walking clubs, or other associations with SPAP educated staff like health promoters or personal trainers (Kallings & Leijon, 2003). The unique aspect of SPAP is that it is individualized counseling and prescription in combination with the cooperation between the Health Care System and NGOs like sport associations, patient organizations or municipal facilities, and private businesses (Raustorp & Sundberg, 2014). SPAP is now implemented in all Swedish councils and is widely spread in primary care (Raustorp & Sundberg, 2014).

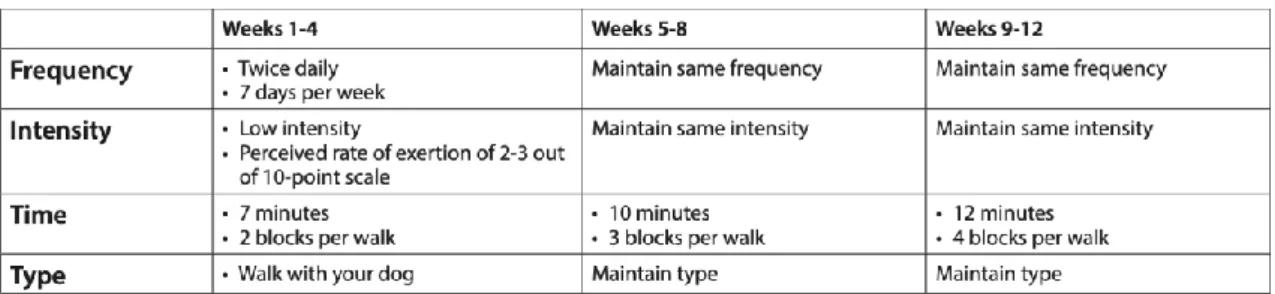

One of the key components of SPAP is that it has to be tailored to the individual physical's capacity, include professional counseling, a follow-up to adjust the prescription and having someone who can motivate for continued physical activity (appendix 1) (Andersen et al., 2013; Kallings, 2016). SPAP treatment starts with a patient describing his or her previous experiences of physical activity, the current level of physical activity, and sedentary behavior. From this, it is possible to assess and measure the patient's health status (symptoms, diagnoses, and potential risk factors), level of motivation, self-efficacy, and readiness to change physical activity behavior. This is followed by a discussion and a written prescription where type and dose (frequency, duration, intensity) of physical activity is shown. This prescription can be prescribed by all licensed healthcare professionals (Borjesson & Arvidsson, 2018; Kallings, 2008). The individual written prescription must show the type of PA (aerobic fitness training/strength training/flexibility training), dose (frequency, intensity, and duration), prescribed activities, contraindications, and a plan for follow up. It can also include the current status of PA, the reason for prescription, and what are the patient's goals/ambitions. The patient also receives a PA diary. FYSS is used to ensure that the prescribed PA is evidence-based (Kallings, 2016).

Figure 3. Exercise prescription (Kern et al., 2019).

In Sweden, patients are usually referred to training specialist (most often physiotherapist) who is trained in motivational interviewing (MI) by general practitioners. Then fitness tests are performed that help to identify appropriate physical activities based on the patient's physical ability and using FYSS (Joelsson et al., 2017). To sustain the prescribed activity, it has to be fun and enjoyable for the person. To find the best suited PA for the patient, there needs to be cooperation between different activity centers and other PA providers outside the healthcare system (Rödjer et al., 2016). The patient is also asked to come for a follow-up that is an integral part of PAP, where possible use of physical activity diary and usage of a pedometer is discussed. Using pedometers can be a way to bridge the gap between research and practice since there are physical activity recommendations based on steps per day and using pedometers has shown to be an effective intervention to increase PA (Garber et al., 2011; Heath et al., 2012; Raustorp & Sundberg, 2014). During follow-up, patient health status is measured as well (Borjesson & Arvidsson, 2018). The follow-up could be done by the PAP coordinator instead of a doctor or a physiotherapist. PAP coordinators would conduct patient-centered interviews, set goals, motivate, find an appropriate physical activity, follow-up, and give feedback (Rödjer et al., 2016).

SPAP has been used in Sweden for almost two decades, and it is recognized as an effective method to increase physical activity in the healthcare setting (Beckvid-Henriksson et al., 2018). An important part of SPAP is how people adhere to the prescription. Adherence by WHO is defined as "the extent to which a person's behavior, taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider" (WHO, 2003). Leijon et al. (2010) study looked at how patients with high blood pressure, diabetes, and/or musculoskeletal disorders could benefit from increased physical activity. Patients were prescribed PAP, and their self-reported adherence rate to the prescription was measured. 56% of the

patients adhered to the prescription after three months, and 50% adhered after 12 months, and adherence to the prescription raised their physical activity levels. Home-based activities are more easily adhered to than facility-based activities. Home-based activities can be walking, jogging, or cycling that can be easily incorporated into everyday life. Facility-based activities require more effort and planning, and that might be the reason why the adherence rate to those is lower (Leijon et al., 2010).

Leijon et al. (2011) found that just 28% of patients did not adhere to the PAP, and the largest group who did not adhere were those who were inactive at baseline or were referred to facility-based activities. Unfortunately, this is the group that would gain the most from increased physical activity. Among older patients, it was sickness and pain for not adhering to PAP, and among younger patients, it was economic factors and lack of time. Economic factors were also more common among patients who were referred to as facility-based activities. The low motivation was the reason for non-adherence amongst those who were prescribed home-based activities and those who had BMI<25. Motivation is influenced by factors like person's self-efficacy, perceived environmental barriers to preforming the behavior, attitudes towards the behavior, and social support, and knowing these factors can help to promote the development of PAP schemes (Leijon et al., 2011). Joelsson et al. (2017) claim that even though patients know the importance of physical activity, they still wait for physicians' recommendations, and that implicates that PAP prescription is better adhered to when written by a physician who has the highest authority and patients' confidence. Leijon et al. (2010) claim that PAP works better on patients who are already at least slightly active, and it might not be enough to initiate a new behavior. O. Morgan (2005) supports the same claim. To achieve a behavioral change and new behavior, it might be necessary to add personal counseling or some type of motivational technique (Leijon et al., 2010).

2.3.

Prescribing PAP

PAP can be prescribed by all licensed healthcare professionals who know patient's current health status, how PA can be used for prevention and treatment, patient-centered counseling, and the PAP method with all five core components. It is mostly prescribed by general practitioners, physiotherapists, and nurses but also by specialist doctors,

duration and the intensity of the activity chosen together with the patient, the likelihood of using PAP increased from 4.20 PAP prescriptions to 3.43 PAP/10.000 consultations. Persson et al. (2010) claim that the impact of lifestyle change is more substantial when family physicians and physical therapists both are involved when prescribing PAP. This claim is also supported by Wemme & Nilsson (2003).

Lundqvist et al. (2019) found in their study that 73% of the patients increased their PA level within six months to some extent when they were prescribed PAP and 42% went from having insufficient PA level to having sufficient level of PA according to the WHO public health recommendations (WHO, 2010). Lundqvist et al. (2019) also suggest that patients with lower levels of PA benefit more from PAP. They also found that patients with greater self-efficacy expectations, more preparedness, and confidence for change, a BMI<30, and a positive value for a measure of physical health were more likely to increase their PA after receiving PAP. The most common recommendation for the patients was moderate-intensity walking 30-45 minutes 2-5 times a week. This kind of activity is suitable for the most physically inactive patients who have the most to gain from increased PA levels (Wen et al., 2011).In Sweden, PAP numbers have seen a positive trend since 2007. It is estimated that about 50,000 prescriptions were written in 2010. This averages about 5 PAP/1000 inhabitants or about 1 PAP/1000 healthcare visits (Kallings, 2016).

2.4.

Implementation

Implementing physical activity promotion into healthcare systems and policies and providing enough resources and support will increase the use of preventive exercise prescription in the management of patients with chronic diseases. Having physical activity promotion programs included in the standard practices and guidelines can increase the usage and quality of these programs. (Grol & Grimshaw, 2003). To tailor an implementation strategy, it requires an understanding of the critical barriers to change and finding creative solutions (Grol et al., 2013).

To implement evidence, it is essential to prepare well: involve relevant people, prepare an evidence-based, manageable, and attractive proposal for change, bring out the main difficulties achieving the change, prepare a set of strategies and measures connected with the problem. Have measurable indicators for success and monitor the progress constantly. The main goals should be to make patients' care more effective, efficient, safe, and friendly (Grol & Wensing, 2013). Some of the barriers to successful implementation in

healthcare are lack of awareness, insufficient motivation, negative attitudes, or old habits (Weiner, 2009).

Li et al. (2018) found that implementation process is influenced by the organizational culture (openness for innovation, positive attitude to change), leadership, communication and networks, resources (financial, staffing and workload, time education and training), champions (someone who advocates for the new way of doing things and is expert, trains others and supports colleagues), and evolution, monitoring and feedback activities within healthcare organizations

2.4.1. Implementation examples

2.4.1.1. PAPP

In 2001-2004 Finland implemented the Physical Activity Prescription Program (PAPP) to increase PA. Their implementation strategy consisted of developing a counseling approach for physicians, providing easy and open access to counseling materials, facilitating the uptake and adoption of the counseling approach, disseminating information about counseling approaches to physicians, health and exercise professionals, and decision-makers and raising financial resources to cover program expenses. A full-time program coordinator was hired, and they had a partnership with the Finnish Medical Association. Physical Activity Prescription form was chosen. They used a counseling approach of 5 A's (assess, advise, agree, assist, arrange) (appendix 2). The strengths in their implementation were using a pilot study, well-known and respected channels for dissemination (professional journals, health and exercise magazines), good counseling material, and an extensive network of peer-trainers (trainers who were trained in counseling to teach it to others). The drawback was a failure to put it to EHS (Aittasalo et al., 2007).

Aittasalo et al. (2006) found that a more centered approach with patient-initiated goals, PA plans with lifestyle activity, and a precise schedule for control is needed in PAPP, and lack of time was reported the most common barrier for counseling. The paper concluded that PAPP could be used as a tool to promote PA in primary healthcare, especially when more time can be allocated for the appointment. The paper also found that after the implementation of PAPP, there was an increase in

moderate-about the effectiveness of PA counseling and establish inter-sectorial collaborations between primary care, municipal PA services, sports clubs, fitness centers and community centers (Aittasalo et al., 2016).

Aittasalo et al. (2016) helped health centers to implement PA counseling through PAPP by offering them local support. Each health center had a working group that planned and carried out development actions. The development work included tutorials, working group meetings, and actions to develop the implantation of PA counseling. Working groups achieved some changes in the familiarity and use of PAP. However, to achieve changes in organizational issues, inter-professional agreements (like entering information to patient record systems) and inter-sectional agreements would have needed a more extended timeframe (Aittasalo et al., 2016). Aittasalo et al. (2016) results are similar to counseling done on smoking, eating fruits and vegetables, and alcohol consumption.

2.4.1.2. SPAP

Gustavsson et al. (2018) found out that there is a lack of knowledge and lack of organizational support when it comes to implementing the SPAP method. Participants (healthcare managers and healthcare professionals) revealed that they have limited knowledge about the components and theoretical principles of SPAP, and they are not sure how to apply it. It was also found that there was insufficient accessibility to policy documents and clinical guidelines, clear instructions from the management side, and lack of resources, mainly time. SPAP is prescribed more when doctors have a chance to collaborate with physiotherapists (Jørgensen et al., 2012).

Persson et al. (2010) claim that it is crucial that the management has a supportive attitude towards SPAP and approves this method. It gives more power to the method. He also found out that it is important to have cooperation outside healthcare (sports clubs, fitness centers, pensioners' and patient associations or municipal facilities and private businesses) to enable the transition of the patient between different organizations. (Petrella & Lattanzio, 2002) support the same idea by claiming that community-based networks can help to develop a supportive environment that helps patients increase and maintain their activity levels. Also, cooperation between doctors and physiotherapists because physiotherapists are more trained to work with physical activity. It should be all health professional's responsibility to support health promotion.

2.5.

Making changes

Healthcare is in constant change with technological advancements, aging populations, changing disease patterns, and discoveries for diseases that require organizational changes to keep up with the societal norms and values (Nilsen et al., 2020). Healthcare workers' workload has increased due to the expectations to document their work, take on administrative tasks, and participate in management-led quality improvement initiatives (Nilsen et al., 2019).

When it comes to changes in healthcare the healthcare professionals must have the opportunity to influence organizational changes that are implemented since they can identify the relevant problems initiate the appropriate changes, it might mean that "bottom-up" change can be preferred (Nilsen et al., 2020). When it comes to "top-down" design where the initiation comes from managers or politicians that lack their input, this might cause frustration (Nilsen et al., 2019). For the change to be successful, healthcare workers should be involved in the early stage of the process and influence the process. Another factor that supports the changes is that they need to be clearly communicated to allow for preparation, so changes should not happen too rapidly. Healthcare professionals need to understand the need for change and how it benefits them and/or the patients so the changes would not be meaningless and unjustified that might create resistance (Nilsen et al., 2020). If healthcare workers are prepared for the change, they can align their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors with the expectations who are in charge of the implementation process. If healthcare workers find changes well-founded, they support them. To have support, healthcare workers need an understanding of why the change was made or prioritized (Beer & Nohria, 2000).

Wensing & Eccles (2005) brought out that healthcare professionals complain about changes that have been implemented by political levels, and physicians or professional organizations should be involved in the decision-making procedure. When conducting a change or new implementation in an organization, it is vital to consider all these factors since research has found that 70% of all organizational change initiatives are failures (Nilsen et al., 2019)

3.Healthcare services role in Estonia

In the Estonian healthcare system, family doctors, together with their nurse, provide primary healthcare. Every Estonian citizen has the right to choose their FD, but in case they do not do that, they are appointed to one by the Health Board based on their primary residence (Ministry of Social Affairs, 2017). In Estonia, healthcare professionals are doctors, dentists, nurses, and midwives if they are registered with the Health Board but not physiotherapists. Estonian healthcare is funded by Health Insurance fund that covers the cost of health services required by the person in case of illness, and their goal is to increase the number of healthy life years (Ministry of Social Affairs, 2018)

Healthcare services can reach many people, so they have an essential role to play when it comes to promoting health. They can reach otherwise difficult to reach populations like the elderly, socio-economically weak, and people on sick leave (Pechter et al., 2012). In the Estonian healthcare system, there are family doctors (FD) who have a good position for health promotion since they have previous knowledge about their patients, the opportunity to provide information and counsel patients concerning risk factors related to their health (Suija et al., 2010). Patients expect to be educated about health-related risk factors, and it is something physicians consider is their responsibility (Pechter et al., 2012).

Suija et al. (2010) found that 94% (208 FDs) of FDs in their study claimed that they counsel their patients about exercise. This contradicts the findings from Pechter et al. (2012), who found that only 34% of patients claimed to have received advice from their FD about physical activity. The difference in numbers might come from different styles of counseling. For the counseling to be effective, it should be patient-oriented and an excellent technique to use for that is MI (Guassora et al., 2015). One reason why physicians do not use motivational interviewing is that they lack enough skills to carry it out, and they do not have enough training to give lifestyle advice. What is more, physicians find it challenging to discuss patients' lifestyles if patients themselves consider their lifestyle unproblematic. It is still necessary to talk to patients about PA and its benefits, but it has to be done in a way that it is sensitive to patients' needs, and the dialogue is not perceived as intrusive (Andersen et al., 2013).

National Health Plan 2020-2030 published by the Estonian Ministry of Social Affairs states that physical activity counseling should be integrated into the health- and social system and improvements should be made to the quality and the accessibility of the

counseling. Also, in the same document, it is stated that the goal is to improve the population awareness about the importance of physical activity and its impact on the well-being of people (Sotsiaalministeerium, 2020). While there are some solutions suggested in the Green Book of Nutrition and Physical Activity, like funding the employment of the second nurse in the FD practices to improve the counseling about physical activity and the creation of a new specialization in the Physiotherapy curriculum called Fitness and Health Counselling that should prepare students who are specialized in human behavior to maintain/improve health and active longevity (Sotsiaalministeerium, 2016), there is a missing link between getting the people from FD offices to the counseling, and that is where Liikumisretsept could be helpful.

4.Research aim and questions

Previous research has shown that Estonians are not physically active enough (WHO 2018), and Estonian doctors do not give recommendations for physical activity to their patients during the consultations (National Institute for Health Development, 2018). This creates the need to find new methods of how to increase PA amongst Estonians and motivate medical professionals to counsel patients on PA. Since PAP is a proven concept to increase PA and QOL (Kallings, 2008), this method has the potential to increase PA amongst Estonians by providing a new way for medical professionals how to prescribe PA to their patients.

The implementation of Liikumisretsept is built on the theories of ORC and implementation (Weiner, 2009; Weiner et al., 2009). ORC helps to understand if Estonian healthcare workers and managers would be committed to implementing Liikumisretsept (Weiner et al., 2009). Implementation theory shows what actions are needed to be taken by medical professionals and healthcare managers to implement Liikumisretsept in Estonian healthcare successfully (Weiner et al., 2009). In this paper, author combines these theories into one since they share numerous similarities.

The aim of this research was to describe Estonian healthcare professionals' views on Liikumisretsept (Physical Activity on Prescription) and problematize the implementation of Liikumisretsept in the Estonian healthcare system. For that, interviews were conducted with Estonian healthcare professionals and managers who have previous knowledge about Liikumisretsept. The focus of the paper was how Estonian healthcare professionals and managers describe and understand Liikumisretsept. Adding to that, the paper aims to problematize the implementation of Liikumisretsept in Estonia by finding out the potential barriers. Together with the potential obstacles for the implantation, the possible benefits of Liikumisretsept to patients were discussed.

Main research questions:

• How do Estonian health care professionals perceive Liikumisretsept? • How could it be implemented in Estonian healthcare?

Sub-questions:

1. What are the opinions about Liikumisretsept of Estonian family doctors, physiotherapists, specialist doctors, and healthcare managers?

2. What kind of collaborations between different medical professions do we need to implement Liikumisretsept in Estonian healthcare?

3. What would be the potential barriers and benefits of implementing Liikumisretsept in Estonian healthcare?

4. What actions need to be taken to implement Liikumisretsept in Estonian healthcare?

5.Theoretical framework

This paper will combine organizational readiness for change (ORC) and implementation theory (Weiner, 2009; Weiner et al., 2009) to support my research aim, and these theories will be used as a tool for analysis to help to answer my research questions. By using ORC theory, it gives a closer look if Estonian medical professionals feel committed to the implementation of Liikumisretsept and have the collective abilities to do so. Implementation theory helps to understand the actions that are needed to be taken to put this idea into use. Together these two theories help to develop a framework for implementing Liikumisretsept in Estonian healthcare

5.1.

Systems approach

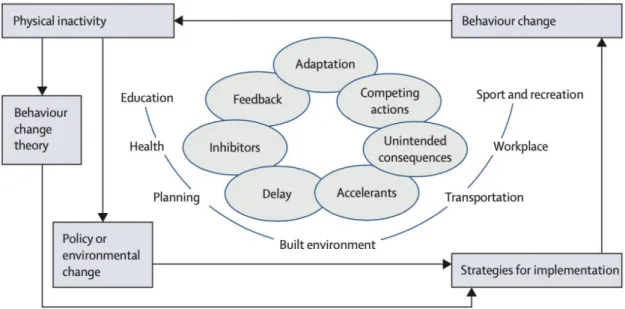

To successfully implement PA in healthcare, it requires a systems approach (figure 4) and strengthening an individual's motivation and capability. Systems approach is a complex systems perspective where physical activity acknowledges issues like delay, functions, adaptation, unintended consequences, competing interests, and feedback that could have a negative impact to increase physical activity. System approach takes into account these complexities and lets planning to counteract these unintended consequences. Through the systems approach, a specific health behavior pathway is attempted to understand and not only determinants at an individual or environmental level. It uses enablers, accelerants, synergies, and interconnectedness of multiple influences to affect physical activity on a population level (Kohl et al., 2012). To give an example of the systems approach, a policy designed to reduce automobile congestion could result in increased PA levels for one segment of the population but for the other segment to reduce it, resulting in a net-zero gain. Improvements in public transport might not have immediate results in increasing transport-related PA by the target population (delay). Specific accelerants and inhibitors like reduced ticket prices could affect PA associated with transport choice (Kohl et al., 2012). For the implementation of Liikumisretsept, it is vital to distinguish what could be the possible issues that might arise during the implementation process and strengthen the motivation and capability of medical professionals.

Figure 4. System approach (Kohl et al., 2012).

Systems approach requires support from the political policymaker, healthcare leader, and at the professional, societal level. This could be done through national evidence-based recommendations and guidelines and also through educational programs from the undergraduate level to medical education that increase awareness and legitimacy. In addition to that, it requires tools for execution and structure for delivery to be available. For example, handbooks like FYSS, having PAVS in EHRs, and the usage of pedometers (Ampt et al., 2009). Also, providing better infrastructure to increase the opportunities to choose activity rather than a sedentary lifestyle which is something that PAP provides (Börjesson & Sundberg, 2013).

5.2.

Implementation science

Implementation science is a scientific study of methods that takes findings into practice and questions if and how an intervention can make a difference to patients' life or the practice of the healthcare delivery team. Implementation science can be complicated, but Curran (2020) provides a clear and easily understandable explanation of the implementation science (figure 4). "The thing" is the intervention/practice/innovation that requires support for implementation. In this paper, it can be replaced with Liikumisretsept. However, in this thesis, the main focus is if Liikumisretsept would

Figure 4. Implementation science made simple (Curran, 2020).

Implementation science has two aims: generalize and produce knowledge that contributes to science and produce knowledge that can be used in practice (Kitson et al., 1998). There is a knowledge-practice gap in healthcare between scientific knowledge and its application in routine healthcare practice. Implementation science is one way to close this gap by promoting knowledge for better uptake of evidence and making improvements in the quality and safety of healthcare. Nevertheless, there are still low rates of adoption and limited use of evidence-based interventions (D. L. Fixsen et al., 2017).

5.2.1. Implementation theory

Weiner et al. (2009) claim that a theory of the organizational determinants of effective implementation (also referred to as implementation theory) can be used for health promotion programs like obesity interventions in middle school or HIV prevention programs in local health departments. From this, it can be claimed that implementation theory can also be used for the implementation of Liikumisretsept since implementation theory is suitable when the implementation requires specialized training, resource allocation, and support (Weiner et al., 2009). Implementation of new practices in healthcare is influenced by a combination of several interdependent factors like complexity and combability with existing routines, strategies for the implementation, the attitudes, beliefs, and motivation of the healthcare workers (Nilsen, 2015). It is important to understand healthcare professionals' views on the implementation to achieve change in evidence-based practice (D. Fixsen et al., 2011). This research uses implementation

theory to investigate Estonian healthcare professionals' views on the implementation of Liikumisretsept.

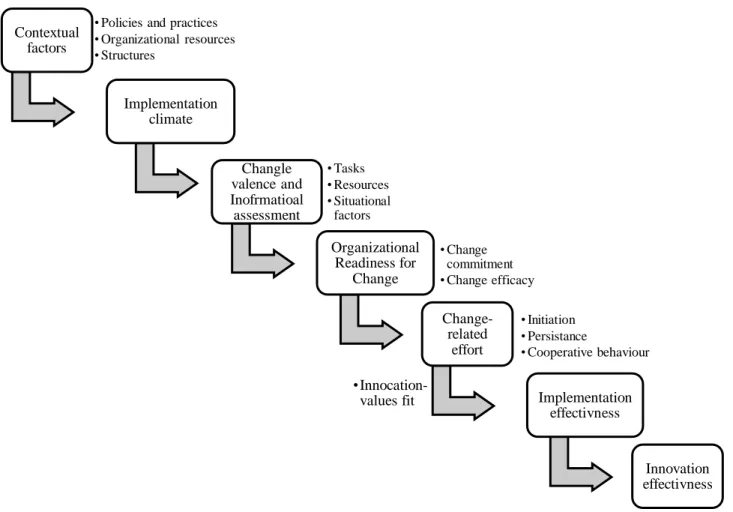

Implementation can be defined as "a course of action taken to put into use an idea, decision, procedure or program" (Klein & Sorra, 1996). It predicts and explains how actions are taken to put the idea, decision, procedure, or program into use result in observed patterns of initial or early use and predicts or explains implementation success through showing how implementation activities have generated desired program use, for example, employee participation in program activities. Implementation theory also shows how organizational members use the new idea, program, process, practice, or technology. Organizational issues like administrative coordination, resource allocation, and technical support are part of the theory of implementation. Effective implementation consists of the organization's readiness for change, the quality of implementation policies and practices the organization employs, and the climate for implementation (figure 5) (Weiner et al., 2009). This paper will focus on what actions need to be taken by medical professionals and healthcare managers to implement Liikumisretsept in Estonian healthcare successfully.

5.2.2. Organizational readiness for change

ORC is a multi-level and -faceted construct. Weiner (2009) defines ORC as "a shared psychological state in which organizational members feel committed to implementing an organizational change and confidence in their collective abilities to do so". It refers to the change commitment and change efficacy by the organizational members to implement organizational change.

In this paper, the author will be combining Weiner et al. (2009) implementation and Weiner (2009) ORC theory (figure 5) because they share numerous similarities with having a slightly different outcome. Both theories are influenced by contextual factors and claim that implementation climate can be made stronger by specific measures. The difference in theories is that ORC theory focuses more if the organizational members have a shared decision and belief that the change is possible (Weiner, 2009). Implementation theory addresses more the question of how innovation will fulfill the values of the employees (Weiner et al., 2009). Implementation policies affecting the

lead to effective implementation and the early use of the initial idea (Weiner, 2009). At the same time, implementation theory moves from implementation effectiveness to innovation effectiveness that shows what benefits the organization gets from the innovation. However, to do that, it needs to have shared beliefs and decisions that the change can be possible, which is part of the ORC theory (Weiner et al., 2009). The final innovation outcome will affect future implementations by shaping the implementation climate.

Contextual factors

When implementing organizational change, content matters as much as context. For example, a healthcare organization can be receptive to new context through implementing changes and values risk-taking and experimentations through having good managerial-clinical relationships, however at the same time showing a low level of content by not willing to implement an open-access scheduling system. Adding to that, simultaneously, the same organization can show readiness to implement electronic medical records (which shows their willingness to new content). This example just shows that healthcare organizations can be opened to implement a certain new policy, but it does not mean they are opened to all new implementations (Weiner, 2009). Weiner (2009) claims that to promote change, it might be necessary to have good managerial-clinical relationships. However, it does not guarantee that clinicians will commit to implementing this change. Having a receptive context (cognitive aspect) is one of the determinants of readiness for change. In this paper, it helps to understand if Estonian medical professionals are ready for the implementation of Liikumisretsept.

The term "readiness" shows the state of being both psychologically and behaviorally prepared to take action and implement the change. To create readiness for a change, it is needed to get rid of existing mindsets and create motivation for change. That can be done by generating a shared sense of readiness by having consistent messages and actions from leadership, sharing information through social interaction, and experience how previous change efforts have gone. A common perception of readiness can be low when leaders communicate inconsistent messages or act inconsistently, when sharing information and interaction is limited inside the organization, or when members of the organization do not have a common basis of experience (Weiner, 2009). Readiness helps to understand what actions are needed amongst Estonian healthcare professionals and managers to implement

Liikumisretsept. It demonstrates the existing mindsets towards the idea and explores the motivation for changing them.

Implementation climate

Implementation climate that affects change valence and informational assessment is based on contextual factors like plans, strategies, structures, and practices to be employed (figure 5). ORC and implementation theories both claim that implementation climate can be made stronger by specific measures like allocating resources or giving accurate information about the change, so the organizations understand the innovation. A strong implementation climate shows that the specific innovation is rewarded, supported, and expected. The stronger the implementation climate is, the greater likelihood of the innovation there is. It can be strengthened by specific measures like high-quality trainings for the members of the organization or including them in the implementation process. Those strengthening measures are innovation specific (Weiner et al., 2009). Implementation climate helps to understand if Liikumisretsept is a change that would be rewarded, support, and expected from Estonian medical professionals.

Organizational readiness for change

Change commitment can be seen if organizational members have a shared decision to pursue the courses of action involved with implementing the change. To effectively implement organizational change, collective action needs to be taken, and each person should contribute to implement the change and produce expected benefits. Committing to a change can be dependent on if organizational members value the forthcoming change, it is referred to as a change valence in figure 5, and it can be raised by showing why change is needed, important, and worthwhile (Weiner, 2009). The more the change is valued, the more willingness there is to implement it, and the reason for valuing change might be that organizational members believe the change is needed, and it can effectively solve an essential organizational problem. They can also see the benefits the change might bring for the organization, patients, employees, or to them personally. Also, they might value it because it is lined with their values or other people (manager, opinion leaders, peers) around them support it. Organizational members can value the change for different

in it (it is also the strongest level of commitment), they have no other choice to do it, or they feel obliged to do it (Herscovitch & Meyer, 2002). Change commitment will help to understand if healthcare professionals and managers are willing to take the actions needed for the implementation of Liikumisretsept and demonstrate if they value this change.

Change efficacy can be seen if the organizational members share the feeling that they are capable of performing the tasks to implement the change (Weiner, 2009). When organizational members make change-efficacy judgments they take into account if they have common, favorable assessment of the task to implement it effectively, resource (human, financial, material and informational) availability for it and in the current situation (is there enough time or if the internal political environment supports it) is it possible to implement this change successfully. These are referred to as informational assessment in figure 5. Change efficacy is high when organizational members share a common, favorable assessment of the task (know what and how to do), there are enough resources available, and favorable situational factors like favorable timing (Weiner, 2009). Implementing organizational change is not dependent on how much resources, endowments the organization has, or what is the organizational structure but rather how they utilize, combine, and sequence those resources and routines (Nilsen et al., 2020; Weiner, 2009). Change commitment and change efficacy demonstrate that organizational readiness is high when members want to implement the change, and they are confident that they can do it (Herscovitch & Meyer, 2002). This helps to understand if Estonian medical professionals share the capability of performing the tasks needed to implement Liikumisretsept and do they see that if there is financial capacity to implement it now or it is something that requires better timing and different allocation of resources.

Change-related efforts

The chances are higher for successful change implementation when the readiness for change is greater, and members agree in their readiness perception (Klein & Sorra, 1996; Weiner, 2009). It is because having high readiness for change makes organizational members more likely to initiate change by initiating new policies, procedures, or practices, making more effort to support the change, and showing persistence in overcoming obstacles or setbacks during the implementation. These are referred to as change-related efforts in figure 5. High readiness for change will also bring more behaviors that are actions towards supporting the change effort that is not part of their job requirements or role expectations (Weiner, 2009). When organizational members commit

to change because they "want to", they show more cooperative (volunteering to complete tasks) and championing (promoting the value of change to others) behavior (Herscovitch & Meyer, 2002). Understanding if the readiness for change is high amongst Estonian medical professionals towards implementing Liikumisretsept will help to explain if they are ready to take steps for the implementation to occur.

Implementation effectiveness

When change-related efforts are high effective implementation can take place, meaning the early use of the initial idea. For that to happen, innovation has to fulfill the innovation-values fit (figure 5). Innovation-values fit shows how the use of innovation will fulfill the values of the employees, and it is dependent on if higher or lower authority group values them. Higher authority group can influence the lower group by making the implementation climate either weaker or stronger. For the innovation-values fit to affect the implementation effectiveness, it is needed that the specific innovation is rewarded, supported, and expected (Weiner et al., 2009). Innovation-value fit helps to understand if implementing Liikumisretsept would fulfill medical professional values and investigates if higher authority groups like healthcare managers see the value in Liikumisretsept. Lastly, effective implementation can lead to innovation effectiveness, showing what kinds of benefits the organization gets from the innovation. This helps to understand what benefits Estonian healthcare would get from implementing Liikumisretsept.

Peters et al. (2013) bring out a few examples like quality improvement programs, electronic health records, and patient safety systems, where organizational changes have taken place. They also claim that there are practices that healthcare workers can use on their own with little training like smoking counseling, and it does not have to be implemented, adopted, or used by other providers to provide benefits to the patients.

ORC theory is useful when implementing changes in healthcare (Gagnon et al., 2011; Nilsen, 2015). What is more, Weiner et al. (2008) bring out in their review paper that ORC is a critical precursor to successful change implementation in healthcare. Organizational changes are part of present-day healthcare, and ORC is one part of implementing the changes (Montague et al., 2007). It focuses on integrating new researched-based knowledge into practice (Gagnon et al., 2011). Since PAP is a proven

ORC can be assessed at the individual level or supra-individual level (team, department, or organization) (Shea et al., 2014). This paper will be using supra-individual level since previous implementations in healthcare like EHC, or patient-centered medical homes have required collective, coordinated actions for collective behavior change by many organizational members (Kim et al., 2017; Weiner, 2009). From this, it is possible to draw assumptions that the supra-individual level will be needed to implement Liikumisretsept in Estonian healthcare.

5.2.3.

Combined theory

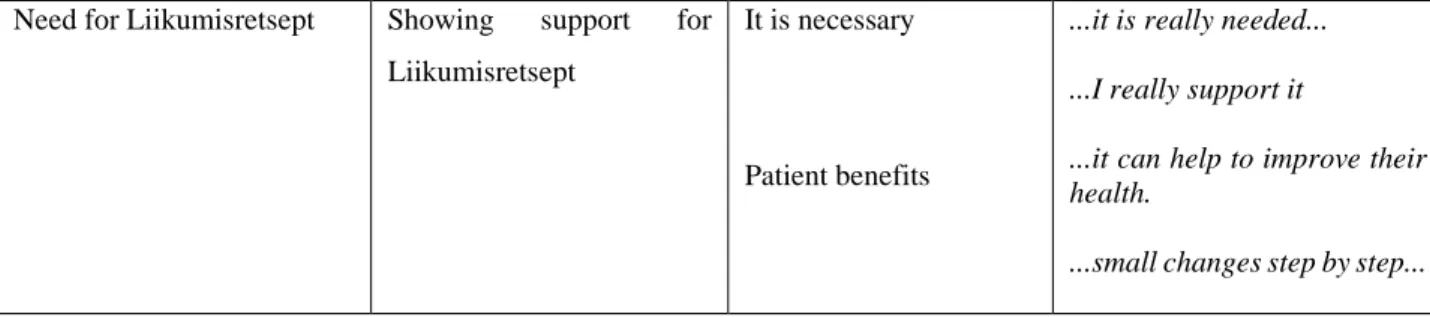

Author combined organizational readiness for change (ORC) and implementation theory (Weiner, 2009; Weiner et al., 2009) into one theory (figure 5). It shows that possible contextual factors influence the implementation climate. Contextual factors help to understand what plans, practices, structures, and strategies need to be employed to implement Liikumisretsept in Estonian healthcare. Implementation climate helps to understand if Liikumisretsept would be supported by Estonian healthcare professionals be evaluating tasks, resources, and situational factors needed for the implementation. ORC helps to understand shared beliefs and decisions about the possibility of implementing Liikumisretsept and shows if there is enough willingness from healthcare professionals to go through with the implementation. If ORC is high change-related effort will take place. This helps to understand if healthcare professionals and managers are willing to initiate the change, do they show support and cooperative behavior for the implementation to take place. Having high change-related effort will lead to implementation effectiveness showing the early use of the initial idea. However, this is dependent on innovation-values fit. Understanding if Liikumisretsept will fulfill the values of healthcare professionals and managers can help to implement Liikumisretsept effectively. Lastly, innovation effectiveness helps to understand the benefits Estonian healthcare would get from Liikumisretsept.

Figure 5. Combined implementation and ORC theory (Weiner, 2009; Weiner et al., 2009)

Contextual factors

• Policies and practices • Organizational resources • Structures Implementation climate Changle valence and Inofrmatioal assessment • Tasks • Resources • Situational factors Organizational Readiness for Change • Change commitment • Change efficacy Change-related effort • Initiation • Persistance • Cooperative behaviour Implementation effectivness •Innocation-values fit Innovation effectivness

6.Methodology

This study is qualitative descriptive research that uses semi-structured interviews to collect data and analyzes data by using inductive content analysis.

6.1.

Research design

Qualitative, descriptive study design was chosen for this research since the goal of the research is to explore the phenomena of Liikumisretsept in Estonia through the eyes of the healthcare professionals to discuss the possible implementation of it in Estonian healthcare. Qualitative research enables this paper to understand and discover the phenomenon of Liikumisretsept and how medical professionals view it from their perspective, which is a goal for qualitative research, according to Caelli et al. (2003). Liikumisretsept is not a well-known phenomenon, and using descriptive study design allows to gather a description of this phenomenon and helps to explain and understand it (Bradshaw et al., 2017). This design focuses on people who have experiences with Liikumisretsept and allows every person to share their views on Liikumisretsept. With qualitative descriptive study, straight descriptions and a comprehensive summary of the phenomenon can be given about Liikumisretsept using participant's language, and it enables researcher to stay close to the data (Kim et al., 2017).

Using qualitative descriptive study design for Liikumisretsept allows learning from the participants and using this knowledge to influence interventions to help practitioners and policymakers (Sandelowski, 2000; Sullivan-Bolyai et al., 2005) with the implementation of Liikumisretsept. This study design is relevant since information is required directly from those who have experience with the phenomena of Liikumisretsept. Also, qualitative research studies have gained popularity in recent years within nursing and midwifery, which shows it is a suitable method to use in healthcare research (Bradshaw et al., 2017). Since the goal of the research is to explore the phenomena of Liikumisretsept in Estonia through the eyes of the healthcare professionals to discuss the possible implementation of it in Estonian healthcare, the use of descriptive research design is justified. Since the concept of Liikumisretsept is not that well known in Estonia, using descriptive study can help to explain what Liikumisretsept is through the eyes of people who have previous knowledge about it and discuss if Estonian healthcare is ready to implement Liikumisretsept.