A Feasibility Study of a CBT-group Treatment for

Hypersexual Disorder in Women

Theodor Mejias Nihlén Malmö University, Malmö 2021 Master thesis in sexology Supervisor: Jonas Hallberg (ANOVA/Karolinska Universitetssjukhuset)

My sincere thanks to

Robert Jacobsson, Katarina Görts Öberg, Malin Lindroth, Eva

Elmerstig, Ulrika Olsson, Daniel Johnson, Fredrika Thelandersson and

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this thesis was to investigate the feasibility of a treatment for hypersexual disorder (HD) by calculating and reporting the results with pre-collected data from a research project at ANOVA/Karolinska

Universitetssjukhuset. The treatment was a cognitive behavioral group therapy (CBGT) developed for HD administered in a 7-session group setting with a sample of HD-diagnosed women (n = 16). Feasibility was explored through symptom change of hypersexuality, sexual compulsivity, psychological distress, and depression. Symptom change in relationship to treatment attendance was also explored. In this thesis, the results are considered in a broader context, discussing theoretical issues concerning women’s sexuality in relation to hypersexual

problems and medicalization of hypersexual behaviors.

The treatment was shown to be feasible. Significant decrease was found on all measures. Attendance rate significantly correlated with a decrease in depressive symptoms, but not on other measures. Women’s sexuality might differ from men’s, but the treatment, which was first evaluated for men, is still feasible for women. Treatment for hypersexual problems in women and hypersexual problems in women in general have been understudied, which makes this study an

important contribution to the research field. Further treatment studies could potentially investigate whether specific alterations based on gender and sexual orientation could be needed for further development of the treatment. There are issues concerning medicalization of hypersexual behaviors which should be considered when addressing the phenomenon, such as the influence of moral and cultural factors on the understanding of hypersexuality. Still, there is need for treatment for hypersexual behaviors experienced as problematic, and having these problems addressed within the medical and scientific field has potential for being beneficial and is preferred to having them left to alternative, unregulated health care providers.

1. INTRODUCTION ... 8

2. RESEARCH QUESTIONS ... 9

3. BACKGROUND ... 9

3.1 Different classifications of hypersexual behaviors ... 9

3.2 Suggestion for DSM-5 and admission into ICD-11... 11

4. PREVIOUS RESEARCH ... 12

4.1 Prevalence and course ... 12

4.2 Related factors and comorbidity ... 13

4.2.1 Neurobiological and neurocognitive factors ... 14

3.2.2 Developmental and personality factors ... 15

4.2.3 Coping and emotional regulation ... 16

4.3 Cognitive appraisals and shame in hypersexual problems ... 17

4.4 Risk factors and consequences associated with hypersexual problems ... 18

4.5 Treatment for hypersexual problems ... 18

4.5.1 Pharmacological treatment ... 19

4.5.2 Psychosocial treatments ... 19

4.6 Measures of hypersexual problems ... 20

5. THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 21

5.1 Cognitive behavioral therapy ... 21

5.2 Sexuality and hypersexual behaviors in women ... 22

5.3 Medicalization and sexuality ... 23

6. METHOD ... 24

6.1 Design ... 24

6.2 Setting ... 24

6.3 Recruitment procedure ... 24

6.4 Treatment components and procedure ... 25

6.5 Primary outcome measure ... 26

6.6 Secondary outcome measures ... 26

6.7 Statistics ... 27

6.8 Safety parameters and ethics ... 27

6.9 Contribution of this thesis ... 27

7. RESULTS ... 28

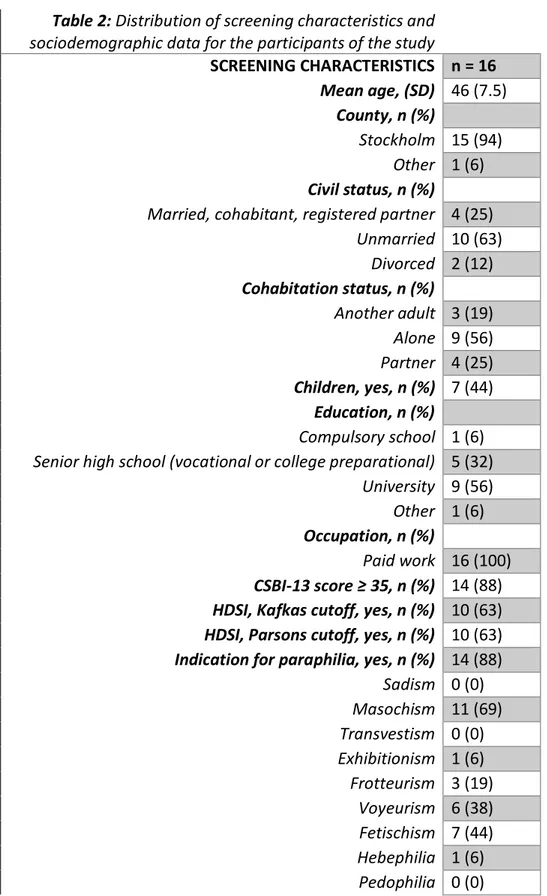

7.1 Participants... 28

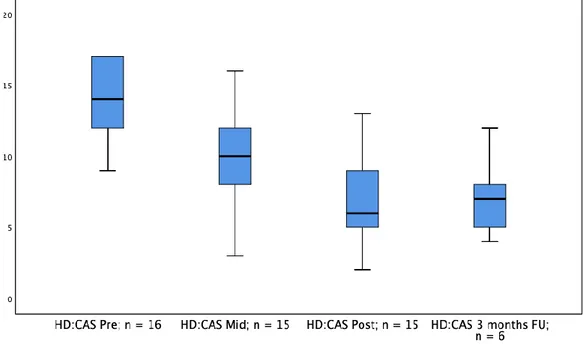

7.2 Primary outcome ... 29

7.3 Secondary outcomes ... 30

8. DISCUSSION ... 32

8.1 Cognitive behavior therapy for hypersexual disorder ... 32

8.2 Treatment for hypersexual disorder for women ... 33

8.4 Strengths, limitations and ethics ... 36 9. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS ... 37 10. REFERENCES ... 38

List of abbreviations

ACT Acceptance and Commitment Therapy ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder ASD Autism Spectrum Disorder

BDSM Bondage/Discipline, Dominance/Submission, Sadomasochism CBGT Cognitive Behavioral Group Therapy

CBT Cognitive Behavioral Therapy CD Conduct Disorder

CORE-OM Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation CSBD Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder CSBD-19 Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder Scale CSBI Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory

DSM Diagnostical and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders GAD Generalized Anxiety Disorder

HBI-19 Hypersexual Behavior Inventory HD Hypersexual Disorder

HDSI Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory HD:CAS Hypersexual Disorder: Current Assessment Scale HIV Human Immunodeficiency Viruses

HPA Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal

ICD International Classification of Diseases LGBTQ Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer MADRS-S Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale MINI Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview OCD Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

PTSD Post-traumatic Stress Disorder RCT Randomized Controlled Trial SAST Sexual Addiction Screening Test SCS Sexual Compulsivity Scale

SSRI Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor STD Sexually Transmitted Disease

1. INTRODUCTION

There are many people, both men and women, who experience lack of control of their sexual behaviors, and experience that this leads to distress and impairment (Briken, 2020). Compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD) has recently been admitted to the ICD-11 as a formal diagnosis (World Health Organization, 2020). A similar diagnosis, hypersexual disorder (HD), was proposed for DSM-5 during its development, but was not included (Kafka, 2014). This was due to questions regarding the scientific validation of the diagnosis (Reid & Kafka, 2014) and there has also been a fear for moral judgements and societal sexual taboos to influence the formulation of the diagnosis in a way that would render it open to misuse (Kaplan & Krueger, 2010). The diagnostic concepts are similar apart from the exclusion of a coping factor in the CSBD version of the diagnosis (Hallberg, 2019). With the inclusion of CSBD in the ICD-11 hope is expressed for more coherent research on compulsive sexual behaviors (Briken, 2020). This is needed since there have long been many different understandings and conceptualizations of the phenomenon in use within the research which scatters the field

(Montgomery-Graham, 2017b) and a common way to conceptualize

hypersexuality has been requested (Carpenter & Krueger, 2013). For clinical purposes, a common understanding might give researchers more confidence and enhance communication regarding the phenomena among health care

professionals (Reid, 2013).

So far, most studies that have been made on compulsive sexual behaviors and related concepts have been done on non-clinical populations (Kowalewska et al., 2020). There has also been a lack of representative research, and women with compulsive sexual behaviors is an understudied group compared to heterosexual men (Kowalewska et al., 2020). This lack concerns both research on etiology and prevalence, as well as research on treatment. Lack in

representation of women in the research becomes especially poignant since there is reason to believe that women’s experiences of sexual compulsive behaviors might differ from men’s experiences. Aspects of sexuality, such as sexual response and motivational forces for sexuality, is thought to differ between men and women (Basson, 2000; Calabro et al., 2019) and it is hypothesized that for women, hypersexual behaviors does indeed present itself in a somewhat different way than for men (Oberg et al., 2017). It has been found that women seeking help for problematic sexual behaviors have more behaviors connected to sexual

interaction with others compared to men seeking help for problematic sexual behaviors, while men have a higher degree of consumption of pornography (Oberg et al., 2017). It also appears as if women with compulsive sexual behaviors have a higher degree of risky behaviors and a lower overall

socioeconomic status than men with compulsive sexual behaviors. McKeague (2014) has claimed that shame is especially important for women with compulsive sexual behaviors and that they are more relationally motivated in compulsive sexual behaviors, although there is evidence that this relational aspect might be overstated in women (Klein et al., 2014). It also seems that in a clinical population women have higher means on measures of hypersexual behaviors than men

(Oberg et al., 2017) but in a non-clinical sample the relationship is the opposite (Bothe et al., 2020). In addition, there might as well be a rise in women self-identifying as having problems with hypersexual behaviors (Oberg et al., 2017), yet there seems to have been no studies on treatment assessment specifically for women (Kowalewska et al., 2020).

This thesis is trying to fill an important gap in the research

CBT-treatment for this group. The study is part of a larger body of work by Jonas Hallberg and his colleagues at ANOVA/Karolinska Universitetssjukhuset and Karolinska Institutet (Hallberg, 2019). The Hallberg group has studied a CBT-treatment manual for hypersexual disorder as a group CBT-treatment and one

individual version administered through the internet, showing good feasibility and efficacy for men. They have also validated the hypersexual disorder screening inventory (HDSI), showing good psychometric qualities. At the time the overall research project was developed, the HD version of the diagnosis appeared likely to become formally recognized by DSM-5, thus the design of the studies has been based on the HD version of the diagnosis. As the data for this study was collected within that project this is also the case for this study. This specific study looks at the feasibility for the CBT-treatment in group format for a sample of women who participated in the research project. It is to the knowledge of the author the first study investigating feasibility for a CBT-treatment for HD for women.

2. RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Aim: The aim of the study was to investigate feasibility of a manual-based cognitive behavioral therapeutic group (CBGT) developed for hypersexual disorder (HD) in a group of HD-diagnosed women. Feasibility was explored through symptom change of hypersexuality, sexual compulsivity, psychological distress and depression, as well as symptom change in relationship to treatment attendance. The specific research questions are:

- Is a CBGT a feasible treatment for HD-diagnosed women?

- How does CBGT for HD influence symptoms of psychological distress and depression?

- Does attendance rate influence treatment outcomes?

3. BACKGROUND

3.1 Different classifications of hypersexual behaviors

Kafka (2010) states that problems associated with excessive sexual behaviors have been documented during a long period in the history of medicine. He mentions Benjamin Rush who was a physician in the late 18th century, as well as

early 19th century clinicians and investigators such as Richard von Krafft-Ebbing,

Havelock Ellis and Magnus Hirschfeldt as having documented the phenomenon. Concepts such as Don Juanism, Satyriasis and specifically for women;

Nymphomania, are according to Kafka (2010) representative of earlier versions of hypersexual disorder (HD). Others though have been skeptical to such a

comparison with older concepts claiming they are embedded in a cultural context that does not allow direct translation (Moser, 2011; Reay, Atwood & Gooder, 2015). In the United States the concept of sex addiction became popularized much due to the 1983 book Out of the Shadows by Patrick Carnes, and he and his followers’ subsequent work on developing screening tools, and an addiction model treatment for the phenomenon (Reay et al., 2015). Love addiction has also been a similarly popularized concept, but there is lack of diagnostic criteria and little evidence for effective treatment of the phenomenon (Sanches & John, 2019). Love addiction could possibly be considered similar to anxious-ambivalent

attachment (Sussman, 2010). Clinicians have earlier also used diagnoses such as excessive sexual drive for women and disorder of sexual preference for men to

diagnose persons who experience that they have problems with sexual addiction (Briken et al., 2007).

It seems as if compulsive sexual behaviors or hypersexuality can present themself in a lot of different ways (Fong, 2006) and some kind of

diagnosis was requested by many clinicians (Goodman, 2001) long before it was taken up as a diagnosis in ICD-11 in 2018. The most popularized term among the public is sex addiction (Reay et al., 2015) and sex addiction have by some

researchers been considered the best terminology for these types of problems (Goodman, 2001). Rosenberg et al. (2014) support the concept of sex addiction and propose that it progresses in the same way as other addictive disorders and that successful treatment is based on similar treatment components as for other addictive disorders. There are also those who suggest that there is neurobiological evidence for hypersexual problems as being best understood as an addiction disorder (Carnes & Love, 2017). Contrary to this view, other researchers claim evidence for HD to be classified as an addiction disorder is lacking (Kor et al., 2013) and others stipulate that the addiction model for either sex or pornography addiction has not been scientifically validated (Williams et al., 2020). Withdrawal and tolerance which are important parts of the understanding of addiction have not been scientifically documented as being part of compulsive sexual behaviors (Samenow, 2010b) and there are studies that have found that tolerance and withdrawal was in fact not an issue for participants in sex addiction treatment (Ševčíková et al., 2018). Fuss et al. (2019) showed that CSBD related to

compulsiveness to a higher degree than to addictive disorders. On the other hand, Samenow (2010b) argues that compulsion is not a good choice for understanding problematic sexual behaviors as patients do gain a psychological reward from their behaviors, and do not necessarily have an anxiety reduction which, according to him, would be the case in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Chatzittofis et al. (2016) found that there appear to be a negative correlation with baseline cortisol on some scales measuring HD, which indicates dysregulation in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis in the measured sample. Since OCD has been found to be associated with cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical circuits (Ting & Feng, 2011) this might be an indication not to understand

hypersexual behaviors as compulsive (Hallberg, 2019). Impulsivity appears to be related to hypersexual behaviors (Carvalho, Guerra, et al., 2015; Reid et al., 2014) and currently the CSBD is classified under the section of impulse control

disorders in ICD-11 (2020). Although other aspects such as problems with self-concept, for instance low self-esteem, might be a potential mediating reason for people with impulsivity tend to have a higher degree of hypersexual problems (Reid, Carpenter, et al., 2011).

There seems to be multiple possible etiologies involved in the development of HD (Samenow, 2010b) and thus Samenow (2010a) suggest that it might be important with a biopsychosocial understanding of the disorder. It is also important to remember that the sexual inhibition being lowered or heightened to create risk for problematic sexual behaviors or dysfunction might be part of a naturally occurring individual variability (Bancroft, 1999). Such a variability exists also in degree of sexual excitation (Bancroft et al., 2009) and high sexual excitation does indeed seem to correspond to higher degree of sexual responses (Erick et al., 2002). Knight and Graham (2017) argue for two main paths to hypersexuality, one being high sexual drive and the other sexual behaviors that are for some reason problematic, for instance due to dysfunctional coping.

A dimensional latent structure for the understanding of HD, rather than a categorical, has been suggested for both men and women (Graham et al.,

2016). This was supported in a general Swedish sample (Walters et al., 2011). Hypersexuality could potentially be understood as a general spectrum from hyposexual to hypersexual (Samenow, 2010b).

A way to differentiate various types of hypersexuality has been to specify whether the problems are present with or without a comorbid paraphilic disorder as this seems to be an important factor in certain presentations of the disorder (Briken et al., 2007). In a sample of Swedish men and women

hypersexuality and paraphilia had a strong association (Langstrom & Hanson, 2006). Sutton et al. (2015) have suggested several subtypes such as the aforementioned paraphilic type, but also avoidant masturbators, chronic adulterers, and patients who are designated by others to have problems with hypersexuality. In a study they revealed some significant differences between the various suggested groups. The paraphilic group had more substance abuse and novelty seeking as a driving force, while avoidant masturbators had higher anxiety, more often had problems with delayed masturbation and were motivated by avoidance of negative affect. Chronic adulterers had more premature

ejaculation and later onset of puberty and patients designated by others as having problems were less likely to abuse substances, be unemployed or have financial problems than the other groups. Reid (2013) suggests considering subtypes based on whether hypersexuality is expressed in solo or relational sex. He also mentions levels of impulsivity and comorbid ADHD as ways of differentiating groups of people with hypersexual problems.

Reid (2015) has discussed the need for determining severity and suggests risk taking level, impairment level, lack of control, consequences, frequency, or duration of the problem as possible variables but find no concrete approach currently agreed upon.

3.2 Suggestion for DSM-5 and admission into ICD-11

A suggestion for DSM-5 was made for the diagnosis of hypersexual disorder (HD) (Kafka, 2010). The diagnosis was constructed as atheoretical and symptom-based to be able to capture the phenomenon beyond academic disagreement on the many aspects of the concept (Kafka, 2010). The criteria for the diagnosis were validated and showed consistency over time, correct reflection of problems through sensitivity and specificity, good validity with related measures and also measures on impulsivity, emotional regulation and stress proneness (Oberg et al., 2017; Reid, Carpenter, et al., 2012). The criteria also showed good internal validity. Consequences specific to HD compared to other psychiatric conditions were also found, such as a higher degree of sexually transmitted infections (STI). In the end HD suggestion for DSM-5 was rejected (Kafka, 2014). It was rejected for DSM-5 partly because of a fear of risking overdiagnosis, and it was said to lack enough empirical support, especially since no large study of prevalence for the diagnosis had been done. Among other things critics of the concept claimed that it was unclear whether HD was a relevant construct in its own right, and not just symptoms of other comorbid diagnoses (Moser, 2011). Although, Reid and Kafka (2014) pointed out that some reasons for exclusion, such as risk for imposing conformity by pathologizing certain behaviors, is more of a critique of psychiatric diagnoses in general.

In 2018, compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD) was included in the section on impulse control disorders in the ICD-11 (World Health

Organization, 2020). Like HD, CSBD targets a persistent pattern of failure to control sexual impulses or urges, resulting in unwanted sexual behavior. It is stated that moral distress about sexual impulses, urges, or behaviors alone are not

sufficient to meet the diagnostic requirements (World Health Organization, 2020). HD and CSBD are likely to describe approximately the same behaviors but CSBD may be more inclusive since the coping criteria is not part of the diagnosis criteria (Hallberg, 2019). The introduction in the ICD-11 as compulsive sexual behavior disorder is anticipated to lead to more diagnostically coherent research (Briken, 2020).

4. PREVIOUS RESEARCH

Because of the many understandings of hypersexual problems, capturing the phenomenon includes looking at research on various concepts, as well as related phenomena such as problematic internet pornography use, sexual offending, and paraphilia. The original concepts used by another author have been applied when so has been considered helpful to increase comprehensibility of the text and it is assumed that the various concepts for hypersexual behaviors capture

approximately the same phenomena.

4.1 Prevalence and course

About 3-5% have been suggested as a prevalence estimate considering the various concepts of hypersexuality and compulsive sexual behaviors in the general

population, and approximately two or three times more men than women have been assumed afflicted (Briken, 2020). Larger prevalence numbers in general and a higher proportion of HD in women were found in a large American prevalence study that found 7.0% of the women and 10,3% of the men to have experienced clinically relevant levels of distress and/or impairment in connection to

controlling sexual feelings, urges, and behaviors (Dickenson et al., 2018). The sample of 2325 was considered nationally representative, and the study was done using the later diagnosis concept CSBD, not including coping as criteria. Fewer criteria might be a reason for the high numbers of prevalence. Problematic sexual internet use was studied in a young Swedish population with 1913 participants (Ross, Månsson et al., 2012). The study found respondents’ answers indicating

Table 1: “Hypersexual disorder proposed for DSM-5 criteria:

A. Over a period of at least 6 months, recurrent and intense sexual fantasies, sexual

urges, or sexual behaviors in association with 3 or more of the following 5 criteria:

A1. Time consumed by sexual fantasies, urges or behaviors repetitively interferes with

other important (non-sexual) goals, activities and obligations.

A2. Repetitively engaging in sexual fantasies, urges or behaviors in response to

dysphoric mood states (e.g., anxiety, depression, boredom, irritability).

A3. Repetitively engaging in sexual fantasies, urges or behaviors in response to

stressful life events.

A4. Repetitive but unsuccessful efforts to control or significantly reduce these sexual

fantasies, urges or behaviors.

A5. Repetitively engaging in sexual behaviors while disregarding the risk for physical

or emotional harm to self or others.

B. There is clinically significant personal distress or impairment in social, occupational

or other important areas of functioning associated with the frequency and intensity of these sexual fantasies, urges or behaviors.

C. These sexual fantasies, urges or behaviors are not due to the direct physiological

effect of an exogenous substance (e.g., a drug of abuse or a medication)

Specify if: Masturbation, Pornography, Sexual Behavior with Consenting Adults,

some problems in 5% of the women and 13% of the men and more serious problems in 2% of the women and 5% of the men. Similarly, in another recent study among 820 post-deployed U.S. military men and women, more men (13.8%) than women (4.3%) were found to have compulsive sexual behaviors (Kraus et al., 2017).

The clinical course and onset of HD is not well examined in the scientific literature (Kafka, 2010). However, Reid, Carpenter, et al. (2012) showed in a study with a sample of 123 men and women that most participants (84%) had experienced a gradual development of their problematic sexual behaviors over months or even years. 54% of the sample had experienced problems before the age of 18 and 30% of the sample had experienced symptoms between 18 and 25 years of age.

4.2 Related factors and comorbidity

There are a variety of factors that have been studied in relation to hypersexual problems. Coleman et al. (2018) argue that hypersexuality is a disorder of identity and intimacy thus putting focus on major existential aspects of being human. In a large Swedish study with a non-clinical sample of 2450 adult men and women, it was found that high rates of impersonal sex correlated with early onset of sexual activity, parent separation, relationship instability, same sex partners, diverse sexual experiences, paraphilic interests and having sexually transmitted diseases (STD) (Langstrom & Hanson, 2006). Specifically paraphilia related disorders have been related to disinhibited sexuality (Kafka, 2003b), and the diagnosis of HD was thus specified as a nonparaphilic disorder in the suggestion made by Kafka (2010) for DSM-5. Raymond et al. (2003) found a 100% lifetime

prevalence of other psychiatric disorders, mostly mood and anxiety disorder, in a sample of men and women with compulsive sexual behaviors, and Kafka (2015) showed that there is a common comorbidity with both unipolar and bipolar disorder as well as anxiety in men. Decreased mood, high anxiety and increased stress correlates were found for men with compulsive sexual behaviors (Wordecha et al., 2018), and negative mood seems to be related to more sexual behavior in women (Klein et al., 2014). Depressiveness and vulnerability to stress were found to be predictors of sexual compulsivity among an almost all male sample (Reid et al., 2008) and a moderate correlation between depressive symptoms and

hypersexual behaviors were found similar across gender, sexual orientation and age (Schultz et al., 2014). In Brazil (Scanavino et al., 2018) and India (Nair et al., 2013) studies have also shown anxiety and mood disorders to be related to

excessive sexual behavior and hypersexuality in both men and women. Related social factors that have been studied in relation to hypersexuality include isolation (Phillips et al., 2019), withdrawal (Reid et al., 2009), and loneliness (Chaney & Burns-Wortham, 2015). Boredom and dissociative symptoms have been conceptualized to facilitate and maintain internet sexual addiction (Chaney & Chang, 2005), and three dimensions of dissociation; absorption, depersonalization and amnesia, were all found to be predicted by online sexual compulsivity in men who have sex with men (Chaney & Burns-Wortham, 2014). Detachment has also been found to predict higher degree of hypersexual behavior in women, but contrary so in men (Giordano et al., 2015). In a sample of persons aged 50-77, boredom and involvement in cybersex predicted online sex addiction (Ševčíková et al., 2020) and it appears that specifically engaging in online sexual behaviors is related to higher risk of developing sexual compulsivity (Efrati & Amichai-Hamburger, 2021).

4.2.1 Neurobiological and neurocognitive factors

Dopaminergic and serotonergic systems seem to be important for sexual response in general (Calabro et al., 2019). Monoamines such as dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin have been found to be important for male sexual behavior in

laboratory animals, and alterations of these can cause functional changes in sexual behavior, and medication based on monoamines appear to ameliorate paraphilic symptoms (Kafka, 2003a). Therefore, it is hypothesized that monoamines play a role in the psychopathology of paraphilia (Kafka, 2003a). According to Grant et al. (2013), it is considered possible with a common neurobiological dysfunction or pathology due to high lifetime comorbidity between different addictions,

including compulsive sexual behaviors, whether they are behavioral or of

substance related and it is also claimed that compulsive sexual behavior and non-substance addiction overlap in neuroimaging (Kowalewska et al., 2018).

Similarities with the neurological patterns of OCD have also been suggested in men with CSBD (Draps et al., 2021). Brain regions and networks connected to sensitization, habituation, impulsivity and reward patterns seem to have altered functioning, for instance in nucleus accumbens, striatum, amygdala, frontal and temporal cotices (Kowalewska et al., 2018). Various studies have found

neurological activation in relationship to hypersexual behaviors that is similar to neurological activation in substance abuse and other behavioral addictions (Brand et al., 2016; Draps et al., 2020; Seok & Sohn, 2015; Voon et al., 2014). Potentially reward mechanisms in ventral striatum may have a role in vulnerability for

problems that are conceptualized as internet porn addiction (Gola et al., 2017; Sohn et al., 2015). An approach bias towards erotic stimuli in heterosexual women were found to correlate with problematic pornography use (Sklenarik et al., 2020) and this has also been shown in a male sample for compulsive sexual behaviors, possibly indicating support for the incentive motivational theory which is sometimes used to explain addictive behaviors (Mechelmans et al., 2014). This theory claims that there is an aberrant response to sexual cues underlying the compulsivity. Similarly, another study on a sample of men who met criteria for CSBD were shown to have higher activation in lingual gyrus when watching porn indicating support for the salience addiction theory (Sinke et al., 2020). When understood for pathological drug use this is thought to be caused by sensitization in the mesocorticolimbic systems towards reward-associated stimuli (Robinson & Berridge, 2008). Briken (2020) argues that there is a problem interpreting

causality from these studies, as there are no longitudinal data. He considers it possible that there might be biological vulnerability for some individuals that are related to neurological correlates to have an increased consumption of

pornography. This, he argues, does not mean that high frequency sexual behaviors or pornography consumption would be problematic for non-vulnerable individuals as current longitudinal studies suggest (Dawson et al., 2019; Koletic et al., 2019; Landripet et al., 2019).

HD has been found to correlate with problems in task initiation and also to some degree with scales measuring emotional control, task shifting and capacity to organize and plan (Reid et al., 2010). This could be related to problems regarding regulation of sexual thoughts and behaviors. Another study has shown a relationship between hypersexuality and problems with emotional regulation, stress proneness and impulsivity (Reid et al., 2014). In a non-clinical sample of women high impulsiveness predicted sexual compulsivity (Carvalho, Guerra, et al., 2015). Other types of behaviors concerning sexual behaviors, such as posting sexual images, were related to higher levels of impulsivity as well as HD itself (Turban et al., 2020). Poor decision making has also been found to

correlate to higher degree of hypersexual behaviors (Mulhauser et al., 2014). Although a study using experimental design to interpret emotional dysregulation found no signs of this in persons with perceived problems of down-regulating their use of visual sexual stimuli (Prause et al., 2013). In fact, it might be the perceived control over one’s sexual thoughts and behaviors that is an important factor for sexuality to be experienced as problematic (Carvalho, Stulhofer, et al., 2015; Wordecha et al., 2018).

In a Swedish study attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD) in youth predicted early sexual intercourse, before age 15 (Donahue et al., 2013). The inattentive subtype of ADHD correlated in a study with nonparaphilic hypersexual disorder in males (Kafka, 2015), and another study found a moderate correlation between ADHD and hypersexuality in both men and women in a non-clinical sample (Bothe et al., 2019). Soldati et al. (2021) though, reviewing the field, did not find it clear that hypersexuality was more common among persons with ADHD, although some studies found a high frequency of ADHD in hypersexual

individuals hinting at the possibility that hypersexual behaviors could sometimes be a functional coping mechanism for ADHD-symptoms. In another study by Reid, Carpenter, et al. (2011) on men with ADHD they demonstrated that neither impulsivity, inattention, memory problems or hyperactive restlessness predicted hypersexual problems. Nevertheless, the study found that problems with self-concept, such as low self-esteem, predicted hypersexual problems. For men especially, but also for women, there was a correlation between autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) and hypersexual behaviors (Schöttle et al., 2017).

3.2.2 Developmental and personality factors

Concerning the relationship to past aversive sexual experiences, Aaron (2012) suggests that problematic sexual behaviors may be related to sexual abuse in childhood, both behaviors of avoidance of sex and compulsive sexual behaviors. Aaron (2012) further proposes that gender and age of being subjected to an aversive experience might partly determine whether a person become more avoidant of sex or develop compulsive sexual behaviors. He claims that the younger a person is when experiencing abuse, the more likely it is that the person will have problems with sexual compulsivity. Sexual abuse experience and poor family environment during childhood were found to be associated with sexual compulsion as well as sexual sensation seeking (Perera et al., 2009) and a study showed both higher sexual compulsivity and sexual avoidance to be related to sexual abuse in childhood (Vaillancourt-Morel et al., 2015). HD patients have also been demonstrated to have more childhood trauma than those without HD

(Chatzittofis et al., 2016) and for instance exposure to interpersonal violence in childhood might be a factor for HD and this seems to be true also for violence witnessed in adulthood (Chatzittofis et al., 2017). In women, a correlation

between self-identified sexual addiction and childhood abuse were found (Opitz et al., 2009). Although in a sample of men who have sex with men there was no significant correlation between online sexual compulsivity and abuse in childhood (Chaney & Burns-Wortham, 2014).

Attachment styles have been examined in relation to compulsive sexual behavior. It appears as if most people with compulsive sexual behavior problems do have a secure attachment but there is still a higher amount of persons, at least in the male population, that have different types of insecure attachment (Gilliland et al., 2015). It was found that insecure attachment is more common in men with out-of-control sexual behavior (Crocker, 2015) and that men

with sex addiction are more likely to have an insecure attachment responding style as well as higher anxiety and avoidance in their relationships (Zapf et al., 2008). Specifically anxious attachment mediated the relationship between adverse childhood experience and sex addiction (Kotera & Rhodes, 2019).

Personality factors have also been discussed as contributing or at least correlating to hypersexuality. Both psychoticism, agreeableness and

neuroticism were found to predict sexual compulsivity in men (Pinto et al., 2013). Contrary, Walton, Cantor and Lykins (2017) demonstrated that agreeableness was lower for men and women with hypersexual behaviors. Rettenberger et al. (2016) did however find similar results on neuroticism and they also found HD to be associated with lower levels of conscientiousness. Psychoticism was also shown to predict sexual compulsivity in a sample of women (Carvalho, Guerra, et al., 2015). A modest but significant relationship was also found with alexithymia and sexual compulsivity (Reid et al., 2008). A study by Reid, Cooper, et al. (2012) indicated that various aspects of perfectionism were positively correlated with higher levels of hypersexual behavior, these included feeling concern over mistakes, needing approval and tendencies to ruminate.

In women, borderline personality disorder was significantly related to compulsive sexual behaviors, even after it was controlled for alcohol and substance abuse (Elmquist et al., 2016) and in a study with both male and female participants a relationship between borderline and CSBD was demonstrated (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2020). However, in a mostly male sample, this association was not strong (Lloyd et al., 2007). In a study on men seeking help for HD, it was indicated that personality disorders were more common in men seeking help for HD than in a community sample, but lower than for persons seeking help for psychiatric conditions in general (Carpenter et al., 2013) and in both men and women paraphilias (Lodi-Smith et al., 2014), such as exhibition and voyeurism, as well as sex addiction (Kotera & Rhodes, 2019) appears to be related to narcissism. 4.2.3 Coping and emotional regulation

Coping is not part of the criteria for CSBD (World Health Organization, 2020) but was a part of the suggested HD diagnosis (Kafka, 2010). The idea that

hypersexual behaviors can function as a coping mechanism is supported in a study by Miner et al. (2019). They found, in a sample of men who have sex with men, that positive and negative affect in relation to sexual behaviors differed depending on whether the person had hypersexual tendencies or not. For hypersexual men the affect predicted sexual behavior. A tendency to experience increased sexual interest when depressed or anxious was correlated to self-defined sex addiction (Bancroft & Vukadinovic, 2004). Experiential avoidance partly mediated the relationship between compulsive sexual behaviors and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Brem et al., 2018) and it seems that women with compulsive sexual behaviors are often motivated by avoiding painful affective sensations (Brem et al., 2017). This hypothesis is further supported as an inverse relationship between HD and mindfulness has been shown (Reid et al., 2014). Another study, looking at problematic internet pornography use, did suggest that experiential avoidance was not connected to the use itself of internet pornography, but to the stress related to the use and that the stress usually increased after the use had been deemed problematic (Wetterneck et al., 2012). LGBTQ-women were revealed to be at higher risk for engaging in hypersexual behavior specifically due to coping (Bothe et al., 2018). Also, lower function of emotional control could be related to hypersexual problems (Schmidt et al., 2017).

4.3 Cognitive appraisals and shame in hypersexual problems

The new CSBD diagnosis in ICD-11 states that hypersexual problems should not be solely due to suffering from moral incongruence (World Health Organization, 2020). Yet, this seems to be an important aspect for many who experience hypersexual problems (Carvalho, Stulhofer, et al., 2015). Studies have found that degree of religiosity predicted if the use of internet for sexual purposes would be experienced as problematic (Ross, Månsson et al., 2012) and there appears to be a link between distress about hypersexual behaviors and negative appraisal of sexual behaviors (Karaga et al., 2016). Lewczuk et al. (2017) demonstrated that this is the case especially for women seeking help for problematic pornography use. They found that religiosity was the most important factor for women seeking help, while for men the quantity of use was more predictive of help-seeking behavior. In an Iranian study it was argued that parents attitudes towards gender and sexuality might be an important factor for compulsive sexual behaviors (Moshtagh et al., 2018). This relates to the importance of distinguishing high degrees of sexual behaviors that are not problematic from compulsive sexual behaviors that do become problematic (Stulhofer et al., 2016). Studies have noticed these differences, for example Carvalho, Stulhofer, et al. (2015) found two groups of hypersexuality, one consisting of persons with high sexual desire and high sexual activity and one that experienced low control over their sexuality and negative consequences from sexual behaviors. In a study of Croatian women, those with high sexual desire compared to those with or without high sexual desire that were also considered having hypersexual problems, had better sexual functioning, higher sexual satisfaction, and lower odds of negative outcomes from their sexuality (Stulhofer et al., 2016). Similarly, van Tuijl et al. (2020)

demonstrated that high sexual desire correlated with less need for help for hypersexual behaviors. It has also been found that sexual compulsivity was not related to novelty and variety of sexual practice but to lower levels of self-esteem (Kalichman & Rompa, 1995).

Shame-proneness was shown to predict high degree of hypersexual behaviors while guilt-proneness predicted a lower degree of hypersexual

behaviors (Giordano et al., 2015). Guilt-proneness also correlated positively with motivation to change and also with preventive behaviors (Gilliland et al., 2011) and seems to be negatively related to behaviors of self-handicapping, that is behaviors that prevent one from achievement (Hofseth et al., 2015). McKeague (2014) writes that shame is important for understanding sex addiction in women. Contrary, Phillips et al. (2019) demonstrated that low-shame proneness actually correlated with hypersexual behaviors. This study did not use a clinical sample which might suggest that those exhibiting hypersexual behaviors and not seeking help for them might be less ashamed than the clinical group exhibiting similar behaviors. They also found that more hypersexual behaviors did correlate with low self-compassion (Phillips et al., 2019). In women, only consequences of hypersexual behaviors appeared to have an influence on shame in a study by Dhuffar and Griffiths (2014). They also did not find an influence on shame from religiosity. In another study shame was not indicated to be an independent predictor of hypersexuality but mediated through neuroticism in a sample of men (Reid, Stein, et al., 2011). It was suggested that this might be because neuroticism is connected to more negative affect because of self-devaluation, dysfunctional coping and less affective awareness. Other studies have shown that

self-forgiveness was negatively related to hypersexual behaviors (Hook et al., 2015) and that low self-esteem (Chaney & Burns-Wortham, 2015; Kalichman & Rompa, 1995), self-hostility (Reid, 2010) and attack against self as coping (Reid et al.,

2009) were associated with hypersexual behaviors. People who are more self-critical tend to be more ashamed, as well as prone to contempt, disgust and sadness (Whelton & Greenberg, 2005).

Maladaptive schemas were found to be linked to higher CSBD (Efrati et al., 2019) and people with a high degree of compulsive sexual behaviors tend to expect their needs not to be met, to consider themselves dependent in daily functioning, having lack in internal and interpersonal limits, and to have

unrealistic standards both towards themselves and others (Efrati et al., 2020). In homosexual and bisexual men with hypersexuality a tendency to magnify need for sex, and disqualify benefits of sex, had a relationship to low self-efficacy for controlling sexual behaviors (Pachankis et al., 2014). The stress was hypothesized to come from not thinking positively about sex, and still pursuing it actively. Negative appraisal of sexual behaviors from religious beliefs seems to be associated with levels of distress from hypersexual behaviors (Karaga et al., 2016).

4.4 Risk factors and consequences associated with hypersexual problems

It appears that hypersexual behaviors are related to several risk behaviors. A Brazilian study found that men with sexual compulsivity showed more risk behaviors such as unprotected anal sex (Scanavino et al., 2018) and sensation-seeking and risk-taking behaviors in general are associated with nonparaphilic hypersexual disorder in men (Kafka, 2015). In a Russian study it was suggested that compulsive sexual behaviors increased risk of HIV (Chumakov et al., 2019). Also for women an association between HIV risk and compulsive sexual

behaviors have been found (Miner & Coleman, 2013) and an association between unprotected sex and sexual compulsivity was shown in a sample of female

migrant workers in China (Luo et al., 2018). Sexual compulsivity also appears to be related to higher alcohol and drug use in both men and women (Seth & Demetria, 2004) and is common among persons with substance abuse (Brem et al., 2017; Stavro et al., 2013). Kafka and Hennen (1999) demonstrated that social disadvantages such as unemployment and disability were related to sexual

impulsivity disorders in men.

In men, hypersexuality was shown to be prevalent in sexual offenders (Kingston & Bradford, 2013). A study found that 12% met the criteria for hypersexuality and hypersexuality was seen as an important risk factor in both sexual offending and reoffending (Kingston & Bradford, 2013) and sexual

preoccupation could be considered an important target in treatment of persistent sexual offenders (Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2005). When it comes to women, research on sexual offending is very scarce in general (Comartin et al., 2021) and women consist of a very small proportion of those being charged for sexual offences (Cortoni et al., 2017).

4.5 Treatment for hypersexual problems

Various treatments have been used for treating hypersexual problems, although few studies using randomized controlled trials have been made, and especially so for women (Kowalewska et al., 2020) and in the studies that have been made there has been a general lack of methodological strength (Hook et al., 2014).

Furthermore, a lot of material published for helping hypersexual patients has been anecdotal suggestions in self-help literature (Reid, 2013). There has been a lack of representation not only of women but also in non-white participants and there has also been a lack of report of sexual preference in the treatment literature (Hook et al., 2014). Other problems found by Hook et al. (2014) in an overview of

treatment studies, were that sometimes participants were self-identified as having problems with hypersexual behaviors without formal assessment and few studies have had long-term follow ups. Another overview of various specific treatments for compulsive sexual behaviors found several potentially effective treatments, for example, psychosocial and psychological treatments such as the 12-step program, CBT and mindfulness, as well as pharmacological treatment with naltrexone or SSRI (Efrati & Gola, 2018b). It also seems as if multimodal treatment, where both psychotherapeutic and psychopharmaceutical components are used can be of benefit for the patients. In a Swedish study it was shown that specialized units gave good treatment for HD and found significant improvement after 10 months (Kjellgren, 2018). The specialized units were found to be skilled in dealing with shame and stigmatization. A Polish study found that religiosity and negative symptoms seem to be important for women seeking help for problematic

pornography use, while for men the amount of use was more important (Lewczuk et al., 2017). Thus, social norms may be important for treatment-seeking

tendencies, especially in women. 4.5.1 Pharmacological treatment

The main pharmacological treatments suggested are SSRI and naltrexone. (Briken, 2020). In a study with hypersexual men imprisoned for sexual offence a significant reduction in sexual preoccupation and hypersexual behaviors were found using either SSRI or antiandrogens (Winder et al., 2017). A recent study at Karolinska Institutet and ANOVA demonstrated significant symptom reduction for HD in a study using naltrexone (Savard et al., 2020). In earlier studies methodological rigor has been lacking and there has been obscuration of results due to high comorbidity in studied patients with other mental disorders (Naficy et al., 2013).

4.5.2 Psychosocial treatments

There are some claims about a good treatment effect from 12 step approaches on HD, with patients feeling less helpless concerning their sexuality, having lower degree of compulsive sexual behaviors as well as sexual suppression, and higher overall well-being and self-control (Efrati & Gola, 2018a). However, parts of the 12-step program, such as step work, have been criticized for not being beneficial and even less beneficial than no treatment (Miller, 2008). There might also be a risk that sex negative attitudes are developed in these programs (von Franque et al., 2015).

Strength-based approaches for sex offenders have been studied, but there seems to be various treatments under that concept and no convincing treatment efficiency has been determined (Marshall et al., 2017). A specific strength-based approach was found in a study with child molesters: the good lives rating used by the researchers correlated with the perceived reentry into society on e.g. accommodation, social support and employment variables (Willis & Ward, 2011) Art therapy for shame in hypersexual patients was found to be equally effective as modified CBT-treatment (Wilson & Fischer, 2018). Relapse prevention for sexual offenders could also be a valuable approach (Ward & Hudson, 1996). An integrative biopsychosocial and sex positive model for treatment of compulsive sexual behaviors has also been developed (Coleman et al., 2018). An important idea of this treatment is to capture the multi-dimensional aspects of compulsive sexual behaviors to create a treatment that is easy to individualize. Briken (2020) suggests an integrated approach based on the dual-control model and the sexual tipping point model to form an individualized

therapeutic intervention. He also suggests relapse prevention at the end of treatment, and if needed further intervention for comorbid disorders. Another suggested approach is an eclectic approach of sexological perspectives, family system perspectives, attachment and interpersonal theories and a social learning perspective (Coleman et al., 2018).

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) has been studied in a randomized controlled trials (RCT) targeting problematic internet pornography use for men (Crosby & Twohig, 2016). In the study, 12 sessions with individual ACT were compared to a wait list condition. The treatment showed significant decrease in hours of pornography used but showed no evidence for increase in quality of life in the 3 month follow up measurement. Most participants were Mormons which might affect representability. Recently, and as part of the same overall research project as this study, a RCT was made including male

participants with HD in a group CBT-treatment that showed significant results on symptom reduction and treatment satisfaction (Hallberg et al., 2019). A version of the treatment was administered individually through the internet, and this as well showed significant decreases on symptoms of hypersexuality, sexual

compulsivity, psychological distress, and depressive symptoms (Hallberg et al., 2020).

4.6 Measures of hypersexual problems

Several measures for the different classifications related to hypersexual behaviors have been developed. Many of them, such as the Sexual compulsivity scale (SCS), Compulsive sexual behavior inventory (CSBI), Sexual addiction screening test (SAST) and Hypersexual behavior inventory-19 (HBI-19) seem to have internal consistency but they are based on different understandings of compulsive sexual behaviors (Stewart & Fedoroff, 2014). In an overview article, looking at what kind of items the various measures of HD and related concepts actually measured, subjective distress was the factor stemming from hypersexual

behaviors that was most thoroughly examined by the different measures included (Womack et al., 2013). Hypersexual behaviors in response to stress were in the same study found in only 12 of 32 examined measures and hypersexual behaviors in response to dysphoric mood in 8 of the measures. It is worth noting that

exclusion of the coping items is in line with the ICD-11 diagnosis. Items examining whether a person was exposed to any substances or had a medical condition that could potentially explain hypersexual behaviors were only found in 4 out of 32 measures.

Hypersexual Disorder: Current Assessment Scale (HD:CAS) (Hallberg, 2019) measures the severity of HD symptoms in accordance with HD criteria as proposed by Kafka (2010) for the DSM-5. It looks at a span of two weeks. HD:CAS has not been properly validated, but an Indian study found high significant correlation between clinical severity assessment and HD:CAS scores in an Hindi translation in a sample of persons with anxiety and/or mood disorders (Nair et al., 2013).

Sexual Compulsivity Scale (SCS) is a measure of experienced compulsive sexual behavior, sexual preoccupations, and intrusive sexual thoughts (Kalichman & Rompa, 1995, 2001). In a sample of HIV-positive men and women the SCS has been shown to be reliable and valid (Kalichman & Rompa, 2001) as well as in a study of college men (Lee et al., 2009), for young adults (McBride et al., 2008) and in a Brazilian sample of both men and women (Scanavino Mde et al., 2016) A Chinese version were found to be well adaptable for a sample of female migrant workers in China (Luo et al., 2018).

Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI) is a measure of sexual compulsivity and was originally used as a 22-item scale (Miner et al., 2007). A subscale of items measuring violence was found not to add much predictive power (Miner et al., 2017) and the scale has since been used in a 13 item version (Dickenson et al., 2018). The 22 item version of CSBI was also validated for homosexual Latino men with good results (Miner et al., 2007) and the 13 item version of the same scale was found to have good psychometric properties for a sample of African American low-income men and women (Carpenter & Miner, 2012). The 13 item version has also been used in a large prevalence study with both men and women (Dickenson et al., 2018)

Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (HDSI) examines three clusters; recurrent problems, clinical distress, and coping (Parsons et al., 2013). In a Swedish population the HDSI was found to have good psychometric properties (Oberg et al., 2017) and was considered to have the strongest psychometric support in a review comparison of six common measures for hypersexual behavior (Montgomery-Graham, 2017a). HDSI and SCS were found not to be comparable in a study with a sample of highly sexually active homosexual and bisexual men (Ventuneac et al., 2015) which might indicate the distinction between a compulsive and a hypersexual understanding of the phenomenon. Parsons et al. (2013) suggests a 20 point cutoff, while Kafka (2013) used a cutoff with 3 or 4 points on at least 4/5 A criteria and at least 1/2 out of B criteria.

A recent scale, Compulsive sexual behavior disorder scale, (CSBD-19), has been based on the ICD-11 understanding of CBSD as an impulse-control disorder and measures control, salience, relapse, negative consequences, and dissatisfaction (Bothe et al., 2020). The scale was found valid and reliable looking at a large sample with participants in the USA, Hungary, and Germany.

5. THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS

5.1 Cognitive behavioral therapy

The treatment studied was developed using principles of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT is a broad umbrella of therapeutic orientations based on behavioral psychological principles and theories about cognitive processes (Kåver, 2016). It is usually structured, transparent and client oriented (Kåver, 2016). Third wave CBT, such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is also influenced by Buddhist philosophy and practice, such as mindfulness techniques. The psychological processes assumed to be active in CBT are well scientifically supported (Bieling et al., 2008). Psychoeducation is very common in CBT and something that generally distinguishes CBT from other types of therapy (Philips & Holmqvist, 2008). Furthermore, homework is also usually used (Scheel et al., 2004) and its use has good empirical support (Philips & Holmqvist, 2008). In general, doing exercises and creating change by direct experience is typical for CBT (Kåver, 2016). Third wave CBT has also introduced working with such techniques as acceptance, valued direction (Harris, 2011) and self-compassion practice (Neff et al., 2019). CBT is easy to adapt to individual needs, also for more complex patients (Beck & Larsson-Wentz, 2007). It is also adaptable for group settings (Singh, 2014), as well as for being administered through internet platforms (Vernmark & Bjärehed, 2013). There are several treatments based on CBT for specific sexual problems, and it is also possible to use CBT principles for various types of sexual dysfunction more generally (Ekdahl, 2017).

Based on the clinical presentation of and previous research on HD treatment, components targeting for instance depressiveness, anxiety and deficits in relational capacity and problem solving were assumed to be helpful also for patients suffering from HD (Hallberg, 2019). Working with CBT combined behavioral and cognitive methods in psychotherapy for anxiety disorders has been shown to be effective according to a meta study (Deacon & Abramowitz, 2004). Pure behavioral therapies were also found efficient. Brief psychoeducation can reduce symptoms of depression and psychological distress (Donker et al., 2009), and functional behavior analysis is considered an effective intervention in treatment (Forsyth & Eifert, 1996). Furthermore, behavioral activation is

evidence-based for depression (Martell, Jacobson & Addis, 2001; Sturmey, 2009) and CBT is efficient for general anxiety disorder (GAD) (Hebert & Dugas, 2019). CBT has as well been shown to significantly reduce internal shame in social anxiety disorder (Hedman et al., 2013). In a meta-study it was found that group therapy in general seems to have the potential to be as efficient as individual therapy (Chris et al., 1998) and in a meta-analysis for group therapy for depression it seemed that the treatment participants improved substantially (McDermut et al., 2001). A study with experiential group therapy showed effects 6 months after treatment as well as a significant reduction of various psychiatric symptoms (Klontz et al., 2000). CBT groups have been shown to be efficient for several different types of psychiatric problems and it is specifically efficient in proportion to therapist hours being used (Bieling et al., 2008). CBT has also been used for problems with ADHD-symptoms (Safren et al., 2011). An American study with Latino participants in CBT treatment for anxiety disorder indicated that CBT was efficient also for Latino participants (Chavira et al., 2014). CBT has also been found to ameliorate symptoms associated with internet addiction (Young, 2013), it has been developed for relational problems (Burman et al., 2018) and is used for working with interpersonal dysfunction and emotional dysregulation (Kåver & Nilsonne, 2021).

5.2 Sexuality and hypersexual behaviors in women

Hypersexual behaviors in women have been understudied and women have rarely been included in research on the phenomenon (Montgomery-Graham, 2017b) and the current diagnosis of CBSD has mostly been developed from research on heterosexual men (Kowalewska et al., 2020). This could be important as it does appear as if women’s sexuality differs to some degree from men’s sexuality. Some suggest this is due to evolutionary and biological factors (Basson, 2000; Thornhill & Gangestad, 2008). Calabro et al. (2019) notes that many neurological factors are similar in both men and women, such as the mechanism for desire, arousal, and orgasm, but that sexual responses differ. Potential reasons for this, they argue, may be hormonal differences and sexual dimorphism in anatomical substrates in genital and nervous systems. Basson (2005) suggests that men and women are differently motivated sexually as women tend to be less spontaneously aroused, and more in need of triggers for arousal. Further, Basson (2000) proposes that women are more mentally excited and less genitally focused compared to men. Men have also been claimed to have a higher degree of interest for fetishes and are more bothered by abstaining from sex (Pedersen, 2005). Young women appear to have a more fluid sexuality compared to other groups (Ross, Daneback et al., 2012). Men are considered as having more desire than women in general (Carvalho & Nobre, 2010).

Some researchers claim that essential sexual differences in gender are sparse and that most differences, behaviors, anticipations and relationships,

are constituted by social context (Tiefer, 2004), and even if sexual capacities, values and responses are potentially more similar than different between men and women, sexual roles and behaviors are highly gendered across cultures (McCarthy & Bodnar, 2005). Butler et al. (2005) argues for the concept of the heterosexual matrix which sets a cultural framework in which sexuality is formed and

expressed. Thus, according to Butler (2006), sexuality and gender are intrinsically connected whether a socially constructed phenomena or not. Even if there are those that propose that no essential differences between men and women in sexual drive exist, most social constructivists would admit that different physiological constitutions do set some requisites for the development of sexuality (Johnsdotter, 2012).

5.3 Medicalization and sexuality

In sociological research, medicalization has been assumed to be an important part of the development of western culture (Conrad, 1992). The concept became widely used in the 60’s and 70’s (Sholl, 2017). Medicalization is when a problem is understood in medical terms and/or handled by medical interventions (Conrad & Barker, 2010). Phenomena can be more or less medicalized (Conrad, 1992) and both psychotherapies and biotherapies can be part of medicalization (Tiefer, 2012). Concerning sexuality, this can be understood as medical authority over sexual matters (Tiefer, 2004) and it is claimed that medicalization in general is an expanding phenomenon (Conrad & Barker, 2010). Foucault (2002) understands the claims to truth about sexuality in medical science to be a way of exercising power and that the ultimate function most of all is disciplinary and he argues that this type of knowledge is used to create norms and for stigmatizing through pathologization (Pedersen, 2005). Spurlin (2019) proposes that there is often a conflation between conformity to sexual norms and good health. Sexuality is a phenomenon that elicits strong emotions for many people and also create polarized opinions on a societal level (Rubin, 1984). Thus, according to Rubin (1984), what is considered normative or not could have great consequences for how sexuality and sexual behaviors are conceived in society. Specifically, she suggests sex negativity as a fundamental part of western cultural norms. Rubin (1984) uses the concept of the ‘charmed circle’ to differentiate expressions of sexuality that are normalized and accepted from those that are not. According to her, those who practice sexual behaviors within the charmed circle are rewarded but those who practice behaviors that fall outside the circle become punished and stigmatized. Well known historical examples of medicine being a part of

regulating sexual expressions based on moralistic values has been the

pathologization of masturbation (Lennerhed, 2002), homosexuality (Norrhem et al., 2015) and BDSM (Carlsson, 2017). Sholl (2017) notes that there can be problems with medicalization when used in a misguided way. But he argues that many critics of medicalization often have faultily assumed a single medical model as well as has been unclear about the delineation of what is to be considered medical. He further proposes that medicalization understood as pathologization of certain phenomena and the use of medical interventions is often justified and can help alleviate suffering, enhance self-control, and reduce unwarranted blame and stigma.

6. METHOD

6.1 Design

This is a within-group feasibility study of a manual-based group-administered CBT-treatment for HD. Outcome measures were administered simultaneously before the initiation of the treatment (pre-treatment), during the fourth week (mid-treatment), and during the seventh week (post-treatment) and three months after the treatment ended (3 month follow-up).

6.2 Setting

The treatment group took place at ANOVA at Karolinska University Hospital (Karolinska, Sweden), a multidisciplinary clinic for research, assessment and treatment in andrology, sexual medicine and trans medicine.

6.3 Recruitment procedure

Advertisements in Swedish newspapers and Google AdWords were used to recruit participants to the overall research project. Patients referred to ANOVA with suitable symptomology received information about the study. Information about the study was also published at the official website of ANOVA. The target population was women and men who self-identified as having problems with “hypersexual behavior”, “out-of-control sexual behaviors” or “sex addiction” and who were interested in participating in a group CBT intervention at ANOVA. Applications were made through a secure Internet platform where the participants gave informed consent and contact information. The participants were asked to fill out an online screening battery with 23 structured questionnaires. These

questionnaires measured sociodemographic data, hypersexual behavior, overall psychiatric status, paraphilic interest, and substance abuse. This was followed by two clinical assessment interviews performed in clinic at the same occasion. HDSI was used for preliminary HD screening and final diagnostic assessment was done through a clinical assessment from a psychiatrist and a psychologist/licensed sexologist. For diagnostic reliability, each participant was reviewed in a referral meeting between the psychiatrist and the psychologist. The inclusion criteria for this study were that the participants; were over 18 years old; fulfilled the proposed criteria for hypersexual disorder; had at least three months stability in their

medication regimen if medicated with any psychoactive compounds; and were willing to be a part of the study. Participants were excluded if they had;

paraphilias of pedophilia, voyeurism, exhibitionism, frotteurism, sadism and/or sexual coercion; severe psychiatric comorbidity (assessed through

Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)); substance abuse; ongoing psychotherapy; or other circumstances that contraindicated for group therapy such as poor hygiene or deviant or therapy-obstructing behavior.

Those participants excluded but in need of further assessment were offered the standard clinical procedure at ANOVA or were referred to another healthcare service if considered more appropriate. A total of 87 women submitted application and 30 moved through to assessment. After assessment, 19 women were included of which 3 declined participation, so 16 women finally started treatment. Recruitment process flow is shown in Figure 1. Given the prolonged recruitment period, randomization of women was not feasible considering too few candidates. The data from the sample was instead used to explore feasibility for the treatment. Both recruitment and the treatment study were continuously ongoing over a period of 4-years (December 14 2011 to July 28, 2015).

Figure 1. Participant flow in the feasibility study of CBGT for HD diagnosed women.

6.4 Treatment components and procedure

The treatment manual was developed for targeting nonparaphilic HD as described in the hypersexual disorder criteria developed by Kafka (2010) for DSM-5 and results from a validity study looking at HDSI measurement for HD (Hallberg, 2019). A similar treatment had been found feasible for men in an earlier study within the same overall research project (Hallberg et al., 2017). The treatment used a CBT framework and consisted of seven modules administered in one session weekly for seven weeks. The administration consisted of both lectures and written materials. Session 1 consisted of an introduction to the study and

psychoeducation of CBT and hypersexual disorder. Session 2 was about surplus and deficits of behaviors, basic functional analysis, and motivation. Session 3 was about urge surfing and identification of values. In session 4 the values identified in the previous session were worked with through behavioral activation and more advanced functional analysis. The session 5 module was about challenging dysfunctional thoughts and beliefs through problem solving, cognitive restructuring and behavioral experiments. Session 6 focused on interpersonal behavior activation using assertiveness skill training, conflict management and working with interpersonal goals. Finally, session 7 included treatment summary

Did not fill in enough data: n = 22

Submitted application: n = 87

Contacted for assessment: n = 65

Declined therapy, n = 3 Assessed: n = 30 Psychiatric contraindication, n = 5 Subclinical, n = 2 Pedophilia, n = 1 Drug abuse, n = 1 Alcohol abuse, n = 1 Contraindication UNS, n = 1

Offered group therapy: n = 19

Participated and/or gained access to treatment material: n = 16

No established contact, n = 17 Declined assessment, n = 13 Did not show up, n = 5

and working with an individual maintenance program. Each session was 2.5 hours long. A total of 127 pages plus appending exercises with written and visual

material were used in lectures and as homework. Two licensed psychologists and a licensed psychotherapist led the group treatment; they had between 1.5 and 15 years of experience in CBT and a minimum of 3 years of experience working with issues concerning sexology/sexual medicine. The group sizes were 2-8. The therapists gave feedback to homework assignments, reinforced behavior change, helped the patients design behavioral experiments and promoted repetition of the exercises.

6.5 Primary outcome measure

Hypersexual Disorder: Current Assessment Scale, HD:CAS (Hallberg, 2019) was used as the primary outcome measure as it measures specifically hypersexual disorder symptoms. It investigates a span of two weeks which is useful for

repeated measurements. The measure has seven items. The first item consists of multiple-choice questions regarding sexual behavioral specifiers experienced as problematic, these are: “masturbation”, “pornography”, “sex with consenting adults”, “cybersex”, “telephone sex”, “visits to venues for sexual entertainment”, and “other”. This item is not included in the calculation of the total score. The following six items measure the number of times the respondent has experienced orgasm through any of the specified sexual behaviors; the amount of time spent daily on sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors; sexual behaviors or fantasies used to cope with dysphoric moods; sexual fantasies and behaviors used to postpone or manage stressful life events or other problems in life; the experienced level of control over sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors, and engagement in risky, harmful, or dangerous sexual behaviors. The questions are measured on a 5-point Likert scale from 0–4 points making the highest possible score 24 points. When analyses were made the third item was found to be incorrectly worded. Thus, the internal consistency at pre-, and post-measurement was examined both with and without item 3. No significant difference in internal consistency was found.

6.6 Secondary outcome measures

Sexual Compulsivity Scale, SCS was used to measure sexual compulsivity. It consists of 10 items (Oberg et al., 2017). The items are scored on a Likert scale from one to four which are summed as an overall score and calculated as a mean. A mean score equal to or over 2.1 is the cutoff for sexual compulsivity.

Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation, CORE -OM was used to measure overall psychological distress. It is a measure that consists of 34 items. It describes the level of psychological distress (Evans et al., 2002). The measure shows a good internal reliability and test-retest stability for all sub-scores, except for the subscore of risk. The mean scores are recommended to be multiplied by 10 so that score format will be easier to interpret (Barkham et al., 2006). There has also been validation of CORE-OM for a Swedish population (Lundgren Elfström et al., 2013).

The Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, MADRS -S (Svanborg & Asberg, 2001) was used to depressive symptoms. The measure consists of nine-items that is designed to measure both the severity of and changes in depressive symptoms. The total scale range is 0–54 where a score of 0–12 indicates “no discomfort”, 13–19 indicates “mild depression”, 20–43 indicates “moderate depression”, and a score higher than 34 indicates “severe depression”. The