Japan: The New Leader of Free Trade?

Case-Study on Japan’s Role in the CPTPP

Núria Casas González

Department of Global Political Studies

Bachelor’s Degree in International Relations

15 ECTS

Spring 2019

2

Abstract

This paper aims at contributing to the debate about Japan’s leadership capabilities. Lately, scholars from all around the world have referred to Japan as the “new leader of free trade”. This comes as a surprise, as the country has always been the archetype of a passive and mercantilist state. Therefore, what role is Japan playing in contemporary free trade agreements? What leadership style, if any, is the country exercising? What changes has Japanese leadership experienced in the last decades? Testing theories of this kind is challenging because there is limited information on the topic and most of it is only available in the language of the country in matter. Drawing on a case study based on the role of Japan in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and analyzing it from Young’s framework on political leadership, this article concludes that Japan is exercising a leadership role in contemporary FTAs.

Word count: 12.636

Key words: CPTPP, TPP11, Japan, Japanese leadership, free trade agreement, East Asia, Asia-Pacific, regional economic integration

3

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 4

2. Literature Review ... 6

2.1. Regional economic integration in East Asia and Asia-Pacific ... 6

2.2. Leadership in regional economic integration ... 7

2.3. IR debate: Japanese leadership ... 10

2.4. Formulation of hypotheses ... 11

3. Background ... 12

3.1. Japan: A passive state ... 12

3.2. Japanese leadership ... 13

3.2.1. Structural leadership ... 14

3.2.2. Entrepreneurial leadership ... 15

3.2.3. Intellectual leadership ... 16

3.3. Japan’s regional role ... 18

4. Methodology ... 20

4.1. Foundations of the method ... 21

4.2. Case-study ... 21

4.2.1. Qualitative data analysis ... 23

4.3. Evaluation of sources ... 26

5. Analysis ... 27

5.1. Empirical data ... 27

5.1.1. From TPP to CPTPP ... 27

5.1.2. Japan’s regional strategy ... 31

5.1.3. Japanese leadership ... 32

5.2. Discussion ... 34

6. Conclusion ... 37

Notes ... 39

4

1. Introduction

During the last decades, economic globalization has promoted regional economic integration all over the world (Deng 1997:353; Fratianni 2006; WTO 2019). Regional economic integration has been part of a continuing debate in the field of International Relations (IR) (Smith 1983; Ricardo 1992; Fratianni 2006; Mukhopadhyay & Thomassin 2010). Lately, East Asian and Asia-Pacific regionalisms in particular have been a focus of attention and many scholars claim they pose a great example of how regional economic integration can lead to significant improvements in regional trade (McKinnon 2004; Richardson 2005; Kim & McKenzie 2008; Korol and Nebyltsova 2015; Chen 2016).

Due to such economic integration, Japan in particular has almost doubled up the number of exports in the last two decades, going from 41 billion in 1990 to 78 billion in 2017 (Japan’s Ministry of Finance 2019). Moreover, the country is now implementing new FTAs such as the Japan-European Union (EU) Pact or the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Within the next decades, agreements like such will contribute even more to the expansion of the Japanese market (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2019).

Due to the future potential Japan seems to have, some scholars have referred to the country as the “new leader of free trade” (Lee-Makiyama 2018; Nikkei Asian Review 2018). This claim, however, goes against the passive and mercantilist image scholars have had of Japan for a long time (Bobbitt 2002; Hagström 2014). Therefore, how can it be claimed that Japan is the new leader of free trade if it has always been the archetype of a passive and mercantile state? In order to solve this puzzle, this paper has set two specific goals: theoretically, to contribute to existing research in the field, like Young’s (1991) work on political leadership and empirically, to explore Japan’s ability to exercise leadership in contemporary FTAs.

In order to give answer to the puzzle, this paper has formulated some specific questions. The main research question is: What role is Japan playing in contemporary FTAs? This one is followed by two other sub-questions: What leadership style, if any, is Japan

5 exercising in the FTAs? What changes has Japanese leadership experienced in the last decades?

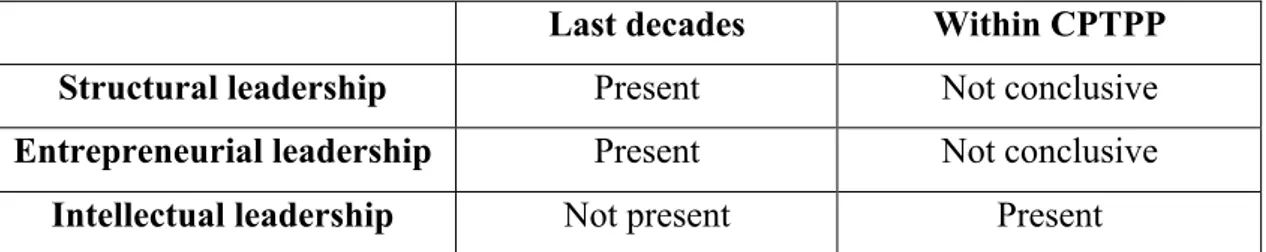

As a first step to try and answer these questions, this paper will establish three sets of hypotheses. After having carried out the research, this paper will determine whether the hypotheses are confirmed or infirmed. Therefore, main hypotheses are the following:

• Japan is acting as a leader in contemporary FTAs

• Japan is exercising the three types of leadership: structural, intellectual and entrepreneurial

• The major change in Japan’s exercise of leadership is its new role as an intellectual leader

In order to provide an answer to the research questions, this paper will use Young’s (1991) framework on political leadership as the theoretical tool. Based on this theory, a method will be developed. The method will be based on a hermeneutic ontology, which will aim at explaining Japan’s role in contemporary FTAs, not at explaining the motivations behind the state’s actions. In order to do so, this paper will take the CPTPP as a case study. More specifically, this paper will conduct a bifurcated analysis that will use qualitative data to investigate Japan’s leadership within the framework of the CPTPP. The first half will look into the nature of the CPTPP and how Japan has had to adapt to changes in the agreement since the United States (US) withdrew from the original Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), as well as Japan’s grand strategy in the East Asian and Asia-Pacific regions. In the second half, the paper will narrow down its focus to analyze Japan’s leadership more specifically, using Young’s (1991) framework on political leadership. Overall, in order to research what has just been mentioned, this paper will be divided into the following chapters: Literature Review, Background, Methodology, Analysis and Conclusion.

6

2. Literature Review

This part of the paper aims at examining previous literature on the topic to expand the puzzle and situate where the research comes from. In order to do so, this chapter will be divided into four subsections: 1) Regional economic integration in East Asia and Asia-Pacific, 2) Leadership in regional economic integration, 3) Japan’s regional role and 4) Formulation of hypotheses.

2.1. Regional economic integration in East Asia and Asia-Pacific

This chapter starts with an explanation of the importance of East Asian and Asia-Pacific integration for regional economic integration as a whole. The reason why this chapter highlights the importance of these types of regionalism is because the CPTPP, as will be seen along this chapter, is relevant for both regions.

For the last decades, economic globalization has promoted regional economic integration all over the world (Deng 1997:353; Fratianni 2006; WTO 2019). In the field of IR, the debate on regional economic integration dates from even before, and many scholars have presented different points of view since then. Generally speaking, on the one hand, liberal political economists have defended regional economic integration and free trade, claiming that it benefits all parties involved (Smith 1978; Ricardo 1992). On the other hand, radical and national critics have criticized regional economic integration and free trade agreements. According to them, “free trade can undermine national economies, create uneven development and damage the environment” (O’Brien & Williams 2016:104). Frank (1967) and Coote (1992) are some of the scholars that have supported this view (Frank 1967; Coote 1992 in O’Brien & Williams 2016:105-108).

Recently, many scholars within IR have highlighted the role of East Asia and Asia-Pacific in regional economic integration. Regarding East Asia, McKinnon (2004), Korol and Nebyltsova (2015) and Richardson (2005) are some of the scholars that have defended the importance of this region. East Asia, according to Korol and Nebyltsova (2015) is one of the greatest centers of contemporary global development. McKinnon (2004) claims that East Asia plays an important role in the world economy due to the trade and economic integration the region has faced. Richardson (2005) also shares this view, adding that East

7 Asian nations are good trade partners because of their prosperity, stability and economic integration with the other Asian countries. When it comes to Asia-Pacific, Chen (2016:167) claimed that “the Asia-Pacific community has the most outstanding economic dynamics [from] the past several decades”. Similarly, Kim and McKenzie (2008:5) claimed that Asia-Pacific financial markets are increasingly integrated with the mainstream world markets.

Both East Asian and Asia-Pacific economic integration have been significantly discussed in the field of IR and they have brought interesting perspectives. Overall, it can be said that economic integration in East Asia and Asia-Pacific poses a great example of how regional economic integration can lead to significant improvements in regional trade. The growing importance of such integration has been materialized in the increasing amount of free trade agreements that are being constituted all over the world (Wignaraja 2011:48). The importance of these two regions is one of the main motivations behind the choice of the CPTPP as a case study. More specifically, the case of Japan – which will be further developed later on – is a good example of the effects of this growing integration. The country, by becoming part of different FTAs, has significantly expanded its markets in the last two decades – up to the point of being considered the “leader of free trade” (Lee-Makiyama 2018; Nikkei Asian Review 2018).

2.2. Leadership in regional economic integration

There is an increasing acceptance around the fact that regions are constructed socio-politically, not geographically (Katzenstein 2000). For this reason, many scholars emphasize the role and influence of a leader that can determine the shape and structure of a region (Grieco 1999; Cooper & Taylor 2003; Destradi 2010 in Park 2010:292). Scholars such as Destradi (2010) have claimed that regional powers strongly influence the interactions that take place regionally, significantly contributing to the regional order. Realist scholars have also shared this view, defending the fact that a hegemonic state can use its material capabilities to enable or constrain actions in the regions (Grieco 1999; Cooper & Taylor 2003 in Park 2010:292).

8 Theories of leadership have been widely used in the field of IR and regional economic integration in particular (Nabers 2010; Åberg 2016; Deng 1997). Nabers (2010), for example, conducted a qualitative textual analysis to look into the conditions for effective leadership for states in international politics, in processes of institutional building. He used different theoretical approaches on leadership, focusing on Burns’ framework (2010:931). Another research that used theories on leadership is Åberg’s (2016) case study on Chinese assertiveness and China’s leadership in East Asia. By combining institutional and material factors, this paper carried out a textual analysis that used Young’s framework on political leadership as the theory. Lastly, Deng’s (1997) case study on Japan’s leadership role in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) also made use of leadership theories. There, the scholar carried out a qualitative textual analysis that also used Young’s theory on political leadership as the theoretical framework.

These are only some examples of research where the scholars used leadership theories to conduct their studies. There is a significant amount of frameworks on leadership; however, many of them present shortcomings. Burns’ (1978) framework, for instance, even though it is one of the most popular and widely-used ones, it does not examine political leadership in particular. Even though it can be adapted to political research as well, this paper prefers to use a theory that is specialized in this branch. Another theory that presents shortcomings is, for example, Kindleberger’s (1973). He fails to assess the essential elements of leadership – the author does not clearly specify whether leaders are collectives or individuals. Other scholars directly link leadership to success, which does necessarily have a causal inference (Young 1991:286-287).

In order to solve these issues and to contribute to existing literature, Young (1991:285) develops his own theory, taking as a premise that leadership has great influence on an actor’s success or failure in international bargaining. However, as an answer to other scholars whose papers present shortcomings, he specifies that acting as a leader does not have a direct connection to success. Building on this, he develops a definition that frames leadership as “[…] the actions of individuals who endeavor to solve or circumvent the collective action problems that plague the efforts of parties seeking to reap joint gains in processes of institutional bargaining” (Young 1991:285). Based on this, he develops three

9 different types of political leadership: structural, entrepreneurial and intellectual (Young 1991:287):

● Structural leadership, often represented by someone who acts in name of an actor - usually a state -, leads by finding ways of bringing that actor’s structural power into the form of bargaining leverage.

● Entrepreneurial leadership, represented an individual who may or may not be representing a major stakeholder, leads by using negotiating skills to influence the presentation of matters and, therefore, convince the other parties by yielding benefits for everybody.

● Intellectual leadership, represented by an individual who may or may not be representing a major stakeholder, leads by using ideas to shape the how other actors understand and interpret the issues at stake.

Young (1991:288) stresses that in order to produce constitutional contracts in international bargaining, actors should possess more than one type of leadership. Lastly, he goes on to argue that leadership should be approached in behavioral terms - it should focus on the actions of individuals, not collectives. “In the final analysis, leaders are individuals, and it is the behavior of these individuals which we must explore to evaluate the role of leadership in the formation of international institutions” (Young 1991:287). As seen above, some scholars have previously used Young’s theoretical framework to bring light into their research (Deng 1997; Åberg 2016). Moreover, in both cases, the authors have adapted the theory to suit their needs. In other words, Young approaches leadership in behavioral terms, but the two previous scholars have used the theory to conduct state-level or system-level analysis. This paper will do the same, given that the research will be approached only from Japan’s perspective – that means, from a state-level perspective.

This early body is very significant in terms of placing leadership theories in the field of IR. However, leadership literature has raised many questions concerning some counties’ leadership capabilities. More specifically, one of the countries that has been involved in these questions has been Japan.

10

2.3. IR debate: Japanese leadership

This last section of the Literature Review will analyze the studies that have motivated the choice of this research topic: the role of Japan in FTAs. Many scholars have researched Japan’s leadership role (Bobbitt 2002; Lee 2002; Solís & Katada 2014). Although their analyses differ in terms of the events analyzed, one common question scholars tried to answer was whether Japan was capable of exercising leadership. Regarding this IR debate, scholars have supported two different views: on the one hand, some authors have questioned Japan’s ability to exercise leadership; on the other hand, others have supported that the country is indeed capable of exercising such role.

As mentioned, some scholars have questioned Japan’s ability to exercise a leadership role (Waltz 1993; Bobbitt 2002; Hagström 2014). Hagström (2014:127), drawing on the concept of identity and the difference between exception and norm, carried out a qualitative textual analysis. Even though his research did not analyze Japan’s leadership role in the CPTPP in particular, it brings valuable insights into the nature of Japan’s foreign policy. The results concluded that Japan is an ‘abnormal’ state. Despite having the capabilities to act as a leader, the Asian country decides to stay passive. Other scholars from the Realist school also shared this view. According to their understanding, the structure of the international system called for the maximization of power, but as mentioned, Japan was staying passive despite of its capabilities (Waltz 1993). Similarly, Phillip Bobbitt (2002:283), in his book The Shield of Achilles pictured Japan as the perfect example of a mercantile state – that means, a state that seeks to improve its relative position to other states, but that does not exercise the role of a leader.

On the other hand, contrary to the results of the previously conducted studies, some scholars have suggested that Japan might be playing an important role in current FTAs (Solís & Katada 2014; Lee-Makiyama 2018; Nikkei Asian Review 2018). This branch of the literature, although defended by very few scholars, is the one that represents the main motivation for the proposed research. An example is Solís and Katada’s (2014) analysis of the effect of Japan’s participation in the TPP. By conducting a case study of the TPP in particular, the scholars concluded that even though more research should be done, Japan could have influenced in some way the negotiations of this agreement. Other

11 sources such as newspapers have also highlighted Japan’s role in nowadays’ regional economic integration, even claiming that Japan is now “the new leader of free trade” (Lee-Makiyama 2018; Nikkei Asian Review 2018). The problem with these sources, however, is that their arguments are not based on solid methodological foundations and there is risk of bias.

This ongoing debate is what has created the research puzzle motivating this paper: how can it be claimed that Japan is the new leader of free trade if it has always been the archetype of a passive, mercantilist state? In order to solve this puzzle, this study has formulated three interrelated research questions, which will be presented again in the next section. The next chapter will also present the hypotheses that stem from these questions, which will serve as a base to reach conclusions later on in the paper.

2.4. Formulation of hypotheses

By proposing an analysis of Japan’s role in an FTA – in this case in the CPTPP- this paper seeks to represent an advancement to previous studies that have highlighted the role of Japan in regional economic integration (Solís and Katada 2014; Lee-Makiyama 2018; Nikkei Asian Review 2018). As seen along this literature, some scholars have already analyzed Japan’s role in FTAs. Just to show a few examples, Deng (1997) analyzed Japan’s leadership role in APEC and Solís and Katada (2014) looked into Japan’s influence on the TPP. However, no-one - according to the author’s knowledge - has yet studied Japan’s leadership in the CPTPP, which is the main motivation for conducting the proposed research. Further reasons behind the choice of this trade agreement will be presented in the methodology chapter. By making use of Young’s theoretical framework on political leadership, this paper will try to provide an answer to this paper’s research questions. As mentioned above, there are three different questions; a general one:

● What role is Japan playing in contemporary FTAs?

And two specific ones that will help to answer the general question: ● What leadership style, if any, is Japan exercising?

12 Before moving onto the Methodology and Analysis sections, this paper will present the hypotheses that will serve as a base for the upcoming chapters:

• Japan is now acting as a leader in multilateral FTAs

• The Asian country is exercising the three types of leadership: structural, intellectual and entrepreneurial

• The major change in Japan’s exercise of leadership is its new role as an intellectual leader

Before introducing the method, this paper will present some background information that will allow to get a clearer view of the research paper as a whole.

3. Background

As mentioned, this chapter aims at introducing the key aspects within Japan’s foreign policy that will provide an overall view of the topic and of the matters analyzed in this study. Moreover, the information presented in this section will, later on, be used to give answer to the third research question: what changes has Japanese leadership experienced in the last decades? The operationalization of the research questions will be further explored in the methodology chapter. This section will be divided in the following sections: 1) Japan: A passive state, 2) Japanese leadership and 3) Japan’s regional role.

3.1. Japan: A passive state

In August 1945, Japan was beaten by outside forces for the first time in history. Losing the Second World War (2nd WW) brought about the loss of territories, as well as the complete destruction of many Japanese cities as a consequence of American bombardments. Moreover, by that time, American troops were about to invade Japanese territories (Togo 2010:31). The post-war period was challenging. In order to rebuild the country, different values of economic reconstruction had to be gradually blended with individual values as democracy, peace or imperial tradition, which became fundamental points for the Japanese government during this period (Togo 2010:35).

13 Under American occupation, a new constitution would be adopted in November 1946. This one included some major changes – mainly based on United States (US) policy objectives -, such as the sovereign right of the people, the new role of the Emperor or, most importantly, the renunciation of war. This last amendment would be materialized in the Article 9 of the constitution, where the Japanese government expressed its willingness to get rid of any threat that could potentially cause another war (Togo 2010:40; Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet 1946; Hagström 2014:127). The Article reads as follows (Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet 1946:4):

“Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.

In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state shall not be recognized.”

After the creation of the constitution, a fourth fundamental point would become key for the Japanese post-war period: economic development and recovery. This would be the most important and powerful element that would allow Japan to recover from those years (Togo 2010:35).

Thanks to this new fundamental point, in the following years Japan increased its economic capabilities to the point of being considered an economic “superpower” by many (Hagström 2014:127). Despite having the capabilities, and due to the pacifist policy Japan had adopted since the 1946 Constitution, the country did not exercise such power as to become a “fully fledged great power” (Hagström 2014:127). Due to these reasons, Japan became the archetype of a mercantilist, passive state. However, regardless of the passivity Japan has been showing in the last many years, it cannot be claimed that Japan has not been exercising any type of leadership until now.

3.2. Japanese leadership

This subchapter aims at exploring the types of leadership that have been present in Japan’s foreign policy during the last decades. The three kinds of leadership that will be used

14 (structural, entrepreneurial and intellectual) are based on Young’s theory on political leadership, previously introduced in the Literature Review.

3.2.1. Structural leadership

After many years of the creation and implementation of the Article 9 of the 1946 Constitution and the subsequent renunciation of war, Japan, in the early 1990s, started gradually changing the institutional setting that had been part of the country’s security policy for the last many years (Schulze 2016:229). A first step towards this significant change came together with the implementation of the so-called ‘checkbook diplomacy’ during the Second Gulf War. In other words, in this initial stage of the policy changes, given that the Japanese state was unable to send troops to the coalition because of the restrictions imposed by the constitution; the Asian country contributed to the war with large sums of money instead. This action led to great criticism and, as a response to the critiques, Japan started modifying its position within foreign policy (Schulze 2016:229). The first actions towards the materialization of this change included the creation of the International Peace Cooperation Law in 1991, which made it possible for Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) to take part in United Nations Peace-Keeping Operations (UNPKO) worldwide. Another major change in Japan’s security policy came with the creation of the US-Japan security alliance. This agreement included actions such as the renovation of the ‘US-Japan Joint Security Declaration’ in 1996 or the creation of the new US-Japan Defense guidelines in 1996 (Schulze 2016:229). Moreover, since 2001, and as a consequence of the 9-11 terrorist attacks, Japan has shown intense support for the international community, and the US in particular, for the fight against terrorism (Hughes 2004: 441). All these changes, together with the administrative reforms the former Prime Minister Hashimoto Ryutaro implemented to increase the responsibilities of the Prime Minister with respect to security and foreign policy, led to a growing importance of security policy in Japan (Schulze 2016:229).

With the first administration of the nowadays Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, even more administrative and institutional changes were implemented. Most importantly, the Japanese Defense Agency (JDA) was upgraded to the Japanese Ministry of Defense (JMOD). With this change, the JMOD gained an equal organizational and legal status as

15 any other ministry in the Japanese Government (Schulze 2016:230). This upgrade, according to Abe was important to “make a clean break with the post-war regime”, as well as to protect “the lives and bodies of the people of Japan” (Abe 2006 in Schulze 2016:230).

Moreover, due to the growing security concerns about countries from the same region - such as North Korea and its nuclear program or China’s unprecedented economic growth – in the 1990s Japan also started strengthening its security posture in East Asia. Also, both as part of the US alliance network and individually, the Asian country established new bilateral military agreements with countries from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), South Korea or Australia. In 2004, following this same path, Japanese policymakers started to push to lift Japan’s ban on the export of weapons.

Japan’s policy changes and its ‘normalization’ as a military power have vital implications for both East Asian and global security, as well as a decisive role in the stability of the region and the international order (Hughes 2005:15). All of these facts prove that Japan started exercising structural leadership in the 1990s and, little by little, the country has been implementing more significant measures, which have led to an increase in the leadership capabilities in structural terms.

3.2.2. Entrepreneurial leadership

The pacifist role Japan has been playing for the last many decades has shaped the foreign policy of the country. For many years, the prohibition on the use of military force made Japan look for other ways to exercise regional and global influence. This is what made the country start using soft power (Hayden 2012:77).

The use of soft power by Japanese authorities, however, goes beyond being a simple strategic move. The Asian state, unable to project other types of power right after losing the 2nd WW, needed to look ways of competing with neighbor countries such as South Korea or China for the regional influence. Therefore, in order to recover from the war, Japan had to make use of soft power, since material sources of leadership and power were not at their hands by then (Hayden 2012:79).

16 In the post-war era, the Japanese public diplomacy mainly consisted of three activities: cultural diplomacy, international broadcasting services and investment and aid for development, being cultural diplomacy the most notorious one. More recently, public diplomacy has also included Japanese “branding”, coinciding with the growing popularity of Japanese culture. This new emphasis within soft power consists of efforts from different stakeholders such as commercial organizations and ministries or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) of Japan, that seek to ring Japanese public diplomacy even further (Hayden 2012:79).

The increasing importance of pop culture represented an opportunity for the government to promote its cultural values. Through such promotion, then, other kinds of international influence could be achieved. In other words, popular culture has connected with political, economic and diplomatic power (Hayden 2012:79). The vibrant Japanese civil society and the stable democracy have been the core of this soft power strength. Other actions such as academic exchanges or trade have triggered the international openness of the country, and could contribute even more to the expansion of the “Japanese model” in the future (Smith 2013:116).

Another important aspect that could benefit Japan’s efforts to project soft power has to do with its alliance with the US. Apart from the benefits it brings in terms of security and the projection of structural power, such bilateral alliance also plays a role in the non-security dimension, with special emphasis on areas such as health, disaster and humanitarian relief and environmental protection. In the longer term, such small-scale cooperation could also start including third countries (Smith 2013:116).

Overall, by making use of its soft power – or entrepreneurial leadership -, Japan has been able to increase educational, economic and cultural interactions with other countries worldwide. Also, its alliance with the US could be used as a vehicle to project even further this type of leadership globally.

3.2.3. Intellectual leadership

The Asian financial crisis from 1997 is widely considered to be an attempt from the Japanese state to gain a leadership position in the Eastern Asian region. During this

17 conflict, both Japan and China sought to be leaders to counter the financial crisis (Nabers 2010:941).

In this period of time, Japan put strong effort into defending the Asian values to try to create a regional solution to the ongoing crisis. They believed that a regional solution, that means, a self-help mechanism, was preferable than looking for help in Western countries (Nabers 2010:944). This idea came together with a widespread criticism of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The most common criticism they faced was focused on two main aspects: 1) their requirement for taut monetary policy and 2) the fact that, in order to get loans, the Asian countries had to carry out a series of structural reforms. Moreover, the institution had limited financial resources given that it had global responsibilities, and it failed to strengthen the countries’ supply side, as well as to give support for economic activities like financing exports (Nabers 2010:945).

Therefore, as mentioned before, in order to end with the regional economic crisis and the values from the IMF, Japan aimed for a regional solution. More specifically, Tran Van Tho,who previously chaired the Japan Forum on International Relations, claimed that

“[…] there is a need for a new institution that plays a role complementary to the IMF’s. Such a framework cannot be established on a worldwide scale, though, because forming a consensus among a large number of countries will be difficult and require considerable time. In addition, crises are often a matter of regional concern, and it is perhaps only natural that deeply interdependent countries should help each other out” (Nabers 2012:945).

The initiative Japan presented to complement the IMF’s role consisted on the creation of an Asian Monetary Fund (AMF). The initiative faced great backlash and few were the countries that actually supported it. The country that presented the most opposition to it was the US. If such a fund was created, they claimed, this one would not only be redundant due to the existence of the IMF, but it would also foster a split between North America and Asia. Many other countries also rejected the initiative - most significantly Occidental, but also many Asian ones like China. Due to this great opposition, the AMF ended up not being realized (Nabers 2010:942).

18 As shown above, even though the Japanese Government tried to exercise intellectual leadership in the East-Asian region, their initiative to try and create an AMF did not succeed. Therefore, their attempt to try and promote a regional identity and, at the same time, lead the region to recover from the crisis did not become a reality.

3.3. Japan’s regional role

The Asian financial crisis led to new correlations between leadership, power and hegemony. In the following years, and following Japan’s attempt to create the AMF, a quest for leadership in the East Asian region developed, involving countries like Japan, China or, later on, the US (Nabers 2010:940).

Until that moment, the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) had been the main focus for East Asian regional economic integration and thus, Japan was not part of it. In order to strengthen economic ties different initiatives were suggested: the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services (AFAS), the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) or the ASEAN Investment Area (AIA), all of which had as their main goal to accelerate regional integration (Kawai & Wignaraja 2008:119). In 1997, the Chinese, Japanese and Korean leaders were invited to the Second ASEAN Informal Summit in Malaysia. In that meeting, China suggested to create a new agreement where three countries that did not belong to the ASEAN would be included: China, Japan and Korea. This new agreement would be called ASEAN+3 or East Asia Free Trade Area (EAFTA) (Kawai & Wignaraja 2008:119). ASEAN+3 would be institutionalized in 1999 after issuing The Joint Statement on East Asia Cooperation, which had as a main objective to “strengthen and deepen East Asia cooperation at various levels and in various areas, particularly in economic and social, political and other fields” (ASEAN 2018:1).

In 2002, despite the existence of ASEAN+3, Japan’s former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi gave a speech where he called for Australia and New Zealand, where later on India would be added, to be included as members in the creation of an East Asian community. These would be added to the members that already constituted the ASEAN+3. This new proposal would be called ASEAN+6 or Comprehensive Economic Partnership in East Asia (CEPEA). This move of creating an expanded version of the agreement encouraged the countries that would constitute ASEAN+6 to encompass

19 ministerial meetings on economy, foreign affairs and energy. These meetings sought to achieve progress towards creating a more functional framework to promote East Asian cooperation (Terada 2010:72). By that time, both ASEAN+3 and ASEAN+6 were coexisting, which created the argument as to which framework was the most effective for promoting regionalism in East Asia (Terada 2010:72).

According to Terada (2019:72), the regional concept of the ASEAN+6 originated from the concerns of the US and Japan that China’s market and economic growth would strongly influence the economic and political trends of the East Asian region. In other words, the creation and implementation of this new initiative was an attempt from Japan and the US to stop China’s growing influence. By involving countries like India or Australia, Japan and the US tried to counterbalance against China, since India or Australia were seen as countries that shared the same democratic values as them (Terada 2010:73). The US views had a strong influence on Japan’s interest in creating the ASEAN+6 framework; that is so that the structure of the agreement followed the same direction as US foreign policy. This was due to the fact that Japan, being a key US ally, was forced to incorporate such influence in its policy formulation.

The attempt to develop ASEAN+6 as more effective than ASEAN+3 faced difficulties: unexpected changes were made to the structure of the framework. One of the changes that challenged ASEAN+6 was the US support for a competing framework, the Free Trade Area in Asia Pacific (FTAAP), which would be endorsed in 2006 as a long-term goal. At this point the US introduced the Asia-Pacific regionalism, which substituted the East Asian one that had been present until that moment. The establishment of this new framework stemmed from the recognition that having overlapping regional trade agreements would have a negative impact on the region (Terada 2010:73; Solís 2010:325). This new agreement would be constituted by the members of the APEC; and it would “deter the formation on an exclusionary East Asian regional bloc, […] improve the US-China relations [and] raise the quality of economic integration as the United states pursued high standard trade agreements” (Solís 2012:325). However, some scholars critiqued the agreement as, according to them 1) “the large US trade deficit with China would make it very difficult to sell a trade deal at home” (Solís 2012:325), and 2) taking

20 into account how heterogeneous and large APEC’s membership was, this new agreement did not seem feasible to counter the other two proposals (Solís 2012:326).

In the last months of Bush’s presidency, it was announced that the US would join the negotiations of a new trade agreement. However, as the US was healing from a financial crisis and a presidential campaign was coming - where public opinion did not believe in FTAs, blaming them for exporting jobs -, President Obama put the talks on hold to first review the US trade policy (Solís 2012:326). Nevertheless, in 2016, after going back to the negotiations, the TPP was constituted. This agreement was constituted by 12 members: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, United States and Vietnam.

In 2017, short after the constitution of the agreement, and after President Trump was elected, the US announced its withdrawal from the agreement. This was done because, according to the newly-elected president, the agreement would steal jobs from the US to benefit large corporations– increasing this way the unemployment rate in the US (Pham 2017/12/29). Following these actions, in 2018, the other countries that constituted the TPP reached an agreement to create the CPTPP, also known as TPP11. This new deal is considered to be one of the biggest FTAs in the world, which represents around 13.5% of the global gross domestic product (GDP) (Goodman 2018).

These last two agreements - TPP and CPTPP - will be further explored in the Analysis chapter of this paper.

4. Methodology

This chapter has two main objectives: a) to introduce the method at the heart of this research and b) to assess the sources from which the data will be obtained. In order to do this, this section will be divided into three subchapters: 1) Foundations of the method, 2) Case-study and 3) Evaluation of sources.

21

4.1. Foundations of the method

The ontological and epistemological foundations are key when choosing a method. The difference between a scholar who aims at explaining and one who seeks to understand usually lays on the ontological and epistemological standpoints of the researcher. This paper has chosen to take a hermeneutic ontology, which aims at understanding Japan’s leadership role in FTAs, not at explaining the reasons and motivations behind such role. Epistemologically speaking, this article leans toward a normative interpretative epistemology. Interpretivism defends the idea that social phenomena cannot exist without our interpretation of the matter – social phenomena is what affects an outcome (Marsh & Stoker 2002:26). If we try to link these standpoints to the methods, then, interpretivist approaches are usually associated with qualitative studies. On a different note, this article will be deductive. A general rule or theory – in this case, Young’s framework on political leadership – will be used to explain a specific case or situation – Japan’s leadership role in FTAs.

4.2. Case-study

In order to give answer to this paper’s research questions, the main one being ‘what role is Japan playing in contemporary FTAs?’, a case study will be conducted. In order to do so, this article will analyze Japan’s leadership role in FTAs, taking the CPTPP as the case study.

As seen in the leadership subchapter of the literature review, case studies are one of the most common methods when assessing leadership in regionalism. For instance, Deng (1997) carried out a case study of Japan’s leadership role in the APEC. There, the author used qualitative data, mainly from second hand sources (such as other studies or newspapers) to asses Japan’s leadership. Similarly, Åberg (2016) took China’s role in Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as a case study to analyze Chinese assertiveness and China’s leadership in East Asia. In this case, the author used the concept of ‘assertiveness’, analyzed through both material and institutional factors to assess China’s leadership position in the AIIB. The way this article will analyze the data is more similar to Deng’s (1997) case. Generally speaking, by using Young’s theory as a base,

22 this research paper will analyze qualitative data (both first and second hand) to be able to assess Japan’s leadership role in the CPTPP. This will be further developed along this chapter.

This article will develop a single, exploratory case study that will use qualitative evidence to back up the findings. According to Yin (2002:13-14), a case-study consists of an empirical inquiry characterized by four aspects: 1) it “investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident”, 2) it “copes with the technically distinctive situation in which there will be many more variables of interest than data points […]”, 3) it is based on several sources of evidence and 4) it “benefits from the prior development of theoretical propositions to guide data collection and analysis”.

Case studies have five different applications. They can be used to explain, describe, illustrate, explore or evaluate. More specifically, this one will consist of an exploratory case study. Exploratory case studies are those that aim at answering “what”-questions while “developing pertinent hypotheses and propositions for further inquiry” (Yin 2003:6). In this case, this paper will use this application to try and find new actors and scenarios where Japan could exercise its leadership. On the other hand, case studies can be either single or multiple. As mentioned, this one will be single – that means, it will only focus on one case. Multiple case studies are useful because they allow to apply a same issue/theory to different situations, but for delimitation purposes, this article will only focus on the CPTPP.

The methodological strengths of case studies are the following: 1) they allow to use significant amounts of empirical data in the research process, which can be both quantitative and qualitative, 2) by only focusing on one case, they allow in-depth analysis of phenomena and rich textual description, and 3) they allow to develop theories that can later be applied to other cases and contexts (Halperin & Heath 2017:214). However, they can also present some limits. Many scholars have presented concerns about the lack of rigor and generalization that case studies offer. Given that in many cases there are no specific procedures to follow, some authors take biased views to influence the direction of their conclusions. Another common problem has to do with generalization. Some claim

23 that case studies provide little ground for generalization: even when similar hypotheses are tested in different contexts, it is still challenging to reach solid conclusions about whether the results confirm or infirm the theory (Halperin & Heath 2017:217). To reach solid conclusions, the hypothesis should be tested with the same method every time (Halperin & Heath 2017:217).

Nevertheless, these shortcomings in case studies can be fixed. To solve the criticism on lack of generalization, for instance, a scholar can carry out a multiple case study instead of a single one. To keep the variables still, one could conduct a most-similar case study, where most of the variables are the same (Yin 2002). Due to delimitation purposes, however, this research paper will only be able to conduct a single case study - where only the role of Japan in the CPTPP will be analyzed. However, this article encourages other scholars to take these aspects into consideration for further studies.

4.2.1. Qualitative data analysis

As mentioned above, this article aims at exploring the role of Japan in contemporary FTAs. To reach conclusions, this paper will make an interpretation of Japan’s leadership role in the CPTPP that will allow to understand the social reality of Japan - it will not seek to create general laws.

This paper has devoted a chapter to explain where Japanese leadership capabilities come from and, more specifically, a section where competing versions of FTAs in East Asia and Asia-Pacific have been looked into. By presenting that overview, this paper was not aiming at carrying out a process-tracing of everything that has happened until now within Japan’s leadership, but rather at introducing the aspects that could be useful to understand the analysis later on, and also at looking for the most appropriate case to analyze. Therefore, this study will explore Japan’s leadership role in FTAs taking into consideration the political and historical past of the country.

As mentioned above, the case analyzed will be the CPTPP. There are many reasons behind the choice of this agreement. First of all, as mentioned above, the CPTPP is relevant for East Asian and Asia-Pacific regionalisms, which pose a great example of how regional economic integration can lead to significant improvements in regional trade.

24 Also, the agreement was signed and ratified in 2018. This means that it is very recent – this way we make sure that the topic is still internationally relevant and, at the same time, we ensure that there are aspects to be researched. Moreover, it is the third largest free trade agreement worldwide by gross domestic product (GDP) after the European Single Market and the North American Free Trade Agreement and it is constituted by some relevant state-actors in the international arena. Finally, the fact that the US is not present in the agreement makes it harder to point at a leader on the first place. This is beneficial for the study because this way we make sure that it is not biased and that the overall research process is more objective. Also, seeing that there is no obvious leader and considering that the agreement follows a more shallow nature than the TPP, it could be a good opportunity to see if Japan finally manages to exercise its leadership freely.

To explore Japan’s role in contemporary FTAs, this paper will conduct a bifurcated analysis that will use qualitative data to investigate Japan’s leadership within the framework of the CPTPP. The first half will look into the nature of the CPTPP and how Japan has had to adapt to changes in the agreement since the US withdrawal, as well as Japan’s grand strategy in the East Asian and Asia-Pacific region. During this discussion it will become clear that Japan was forced to take a leading role in the agreement after the US withdrawal. The main reason behind it was the need to counter China’s leading role in Asia. The grand strategy, therefore, was a reflection of this need, where Japan aimed at taking over the leading position in the region. In the second half, the paper will narrow down its focus to analyze Japan’s leadership more specifically, using Young’s (1991) framework on political leadership. This part of the article will identify evidence that proves Japan’s leading role in the region within the framework of the CPTPP.

Before moving on to the analysis, however, it is important to operationalize the theory – that means, to turn the abstract definitions for each type of leadership into observable indicators that can be found in the data. For structural leadership, the element analyzed will be hard power. More specifically, the paper will look into economic and military tangible resources such as payments or ways to coerce. Examples of this can be having an important security posture in the region or giving money to infrastructure funding for coercive reasons. For entrepreneurial leadership, the element analyzed will be soft power. More specifically, the paper will look into tangible resources in the diplomatic context

25 and agenda setting. Examples of this can be the internationalization of Japanese products or technologies, development approaches to critical infrastructure-building, opportunities for developing countries or setting rules based on Japanese ideals. Lastly, intellectual leadership will be analyzed by looking into proposals of regional cooperation Japan has made and other initiatives the country has come up with in relation to the CPTPP. To analyze the previously operationalized theory, this paper will use publicly-accessible qualitative data, both first and second hand. By using different kinds of material, this paper aims at making data triangulation. That means, by comparing and contrasting different sources, the validity of the study will increase. More specifically, the material analyzed will consist of speeches and statements from politicians involved in the CPTPP, policy documents and second-hand sources such as relevant books and research papers. The first-hand data will be taken from sources such as the Japanese government website – which also includes the Diet of Japan- or the US government website. Second-hand data will be looked for in IR journals from the Malmö University library or in relevant newspapers’ webpages. All of this information will be looked for through the online search system of the different websites stated above. The search will include politicians’ comments and relevant policy documents and evidence, not only from the CPTPP but also from the TPP. The reason why this paper will focus on data from the TPP as well is due to the fact that both agreements have the same economic and strategic significance, so the data from the TPP is also relevant in this case.

By analyzing all of this material, this paper will be able to answer the research questions. Just to provide a better understanding of what will be done in the following chapter, the research questions will also be operationalized. The main research question, ‘what role is Japan playing in contemporary FTAs?’ will be answered after having answered the two sub-questions. All of the questions consist of descriptive ones because, as mentioned above, this paper aims at understanding Japan’s leadership in contemporary FTAs, not at creating general laws. Therefore, the first sub-question is: what type of leadership, if any, is Japan exercising in the FTAs? This question will be answered directly after applying the theory to the data. That means, this question only requires to assess if any of the leadership types from Young’s theory are present in Japan’s role in the CPTPP. The second sub-question is: what changes has Japanese leadership experiences in the last

26 decades? In order to answer this question, the paper will compare the results obtained in the Analysis with the information from the Background section. By comparing them, this research paper will be able to determine what has changed in the last decades. Lastly, in order to answer the general question: ‘what role is Japan exercising in contemporary FTAs?’, this paper will look into the results from the previous two sub-questions to reach a general conclusion. All of this will be argued for and developed in the Discussion subchapter of the Analysis. There, after having presented the evidence in the Analysis, everything will be compared and discussed, so that the reader can better understand the results of the study.

4.3. Evaluation of sources

As mentioned above, this paper will use both first and second-hand data to conduct the analysis. Regarding second-hand sources, especially newspapers, it is important to highlight that this paper is aware of the fact some of the information might be biased. The information presented in newspapers can sometimes be based on subjective interpretations of the matters or be government-controlled, which can affect its validity and reliability. Therefore, by doing data triangulation we will try to counterbalance the disadvantages that making use of newspapers presents.

Also, before moving on to the analysis, this article will mention the problems presented when looking for the data. The first and most important problem this paper has faced has been that the CPTPP is a very new agreement. Seven of the countries that constitute the agreement ratified it in 2018 (Australia, Canada, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore and Vietnam), and the remaining four countries (Brunei, Chile, Malaysia and Peru) still have not done so. Therefore, even though the agreement has already come into force, there is very little evidence of actions that have already taken place within the framework of the CPTPP. This has not allowed to reach solid conclusions in some regards. Also, a lot of the information and reports found were only available in Japanese, with no translation available, which was one of the most challenging problems when processing the data.

As mentioned above, this paper will take a state-level perspective, as the main goal is to analyze the facts from Japan’s perspective. This article is aware of the fact that focusing

27 only on a statist point of view could leave some aspects uncovered, but for delimitation purposes it will only be possible to look into this dimension. Further studies could consider to analyze this from individual or system-level perspectives, which would bring more variables into consideration and, therefore, add more perspectives to the research on the field.

Overall, the focal points of this research paper will be contemporary FTAs and, more specifically, the role of Japan in such regions within the CPTPP. As mentioned, it would have been interesting to include more variables in this study but, for delimitation purposes, only these ones will be taken into account.

5. Analysis

The aim of this chapter is to tie the theory and method together to give answer to this paper’s research questions. As mentioned previously, this paper has formulated three interrelated questions: 1) What role is Japan playing in contemporary FTAs? 2) What type of leadership, if any, is the Japanese state exercising? 3) What changes has Japanese leadership experienced in the last decades? In order to analyze the data that will give answer to these questions, this section will be divided into two main subchapters: 1) Empirical data, where all the empirical data will be presented, and 2) Discussion.

5.1. Empirical data

5.1.1. From TPP to CPTPP

After the 2008 Financial Crisis, “the major geostrategic challenge facing Asia, and the United States in Asia, was how to react to the dramatic rise of China in the previous decade. China’s spectacular economic growth […] and its thorough integration into the economies of the region through a web of trade and investment had permanently altered the geopolitical landscape” (Bader 2013:2-3). This was, according to Jeffrey Bader, the former Asian affairs director of the US National Security council, the biggest problem for the US in Asia. Together with this fact, the by-then leading FTA in East Asia - the FTAAP - was facing problems. As mentioned above, scholars who critiqued the agreement claimed that 1) “the large US trade deficit with China would make it very

28 difficult to sell a trade deal at home” (Solís 2012:325), and 2) taking into account how heterogeneous and large APEC’s membership was, this new agreement did not seem feasible to counter the other two proposals (ASEAN+3 and ASEAN+6) (Solís 2012:326). The US was in a serious need for leadership both regionally and globally. The US trade deficit with China was $250 billion per year and many Americans felt weak in front of the significant scale of the Chinese possession of US debt. The Obama administration knew that approaching China unilaterally would not bring satisfactory outcomes. The result to this problem, therefore, was to ensure that the US role in Asia would be strengthened (Bader 2013:3). This can be seen in Barack Obama’s speech in the Australian Parliament from 2011, where the by-now former president claimed that their presence in the Asia-Pacific region was “a top priority”. He went on by saying: “our enduring interests in the region demand our enduring presence in the region. The United States is a pacific power and we are here to stay”1. In order to counter all those issues, the US created the TPP, which would be signed in 2016. One of the central matters for the US in this agreement was the exercise of leadership. As Andrew Robb, Australian Minister for Trade and Investment argued, “the US must continue to play a very significant leadership role”2. Such leadership, he argued, would be critical for securing an agreement for the TPP.

The US shaped the outcome and structure of the TPP in many ways. As Barack Obama said himself in Oregon in 2015, “the TPP […] reflects our values and ways”. “Some of [the other TPP countries], they do not have the standards for wages and labor conditions that we have here”. Asserting the US’ leadership, the former president went on by saying:

“If any of the […] countries in this trade agreement do not meet [the] requirements, they will face meaningful consequences. If you are a country that wants to enter this agreement, you have to meet higher standards. If you don’t, you’re out. If you break the rules, there are repercussions, and that is good for American businesses and American workers, because we already meet higher standards [than] the rest of the world, and that helps level the playing field. And this deal would strengthen our hand overseas by giving us the tools to open other markets to our goods and services and make sure they play by the fair rules we help to write”3.

29 Such American leadership in the shaping of the TPP was reflected in many different aspects. Some of the most significant ones were, for instance, the environmental policies, where the US forced the other members to sign a series of environmental agreements; or the adoption of horizontal issues to try and tackle non-tariff barriers. This last objective would be implemented by establishing a coordinating office, similar to the US Office of Information and Regulation Affairs (Inside Washington Publishers 2011/05/13; Inside Washington Publishers 2011/03/11). Most significantly, the US also increased the already existing provisions on investment and intellectual property or implemented the open membership clause (Solís 2012:333).

These US-led policies and the overall nature of the TPP made it hard for some countries to join the FTA. Japan, for instance, was one of the nations that faced difficulties. Firstly, the admission of the Asian country into the agreement was not simple, neither from Japan’s or from the US’ side. On the one hand, it was difficult for the country to build domestic support for participating in the agreement. The Japanese economist Nobuhiro Suzuki, for example, claimed that “Japan [had] to examine its domestic policies such as boosting self a sufficiency reach before diving into […] a pact like the TPP. By removing the tariffs completely or unifying investments and services now only [damaged] the Japanese economy”4. On the other hand, the US did not make it easy for Japan to join the agreement either. Many car companies tried to block Japan’s membership, claiming that “with the elimination of the US tariff on car imports […] an avalanche of Japanese imports could ensue” (Solís 2012:334; Inside Washington Publishers 2012/05/05; Inside Washington Publishers 2012/03/16).

Despite the difficulties, Japan ended up joining the TPP. According to Shinzo Abe, the Japanese Prime Minister, the TPP would allow to “turn the [Asia-Pacific] area into a region for lasting peace and prosperity"5. Short after, in January 2017 Japan ratified the agreement. Parallelly, however, the newly elected President Donald Trump announced the US’ withdrawal from the TPP, which came into force on the third day of his mandate. “I am going to issue a notification on intent to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a potential disaster for our country. Instead, we will negotiate fair, bilateral trade deals that bring jobs and industry back on to American shore”6. Many politicians from the other countries that constituted the TPP believed that, without the US, the trade

30 agreement would become insignificant. Abe, for instance, claimed that “as for aiming to bring the [TPP] into effect without the United States […] there [is] no such discussion. TPP is meaningless without the US”7.

Despite Japan’s initial opposition to the establishment of an alternative trade deal that would substitute the TPP, the Asian country not only ended up giving in, but it actually ended up being the country that pushed through the new agreement into effect: the CPTPP. Moreover, Japan adopted a leading role in this new agreement, possessed previously by the US. This fact is reflected in the words of Toshimitsu Motegi, the Japanese Minister of State for Economic and Fiscal Policy, at Bloomerang, The Year Ahead summit in Tokyo from 2018. There, the Minister said: “as for the TPP11, last year in January the US expressed its intention to exit, and then Japan came the leader of the discussion”8.

Therefore, the remaining 11 countries that initially constituted the TPP drafted a revised version that excluded many provisions that were part of the initial agreement (Asian Trade Center 2017). The idea behind the suspension of such 22 provisions was to make of the CPTPP a more shallow, less intrusive agreement so that all member countries could obtain benefits out of it. As Motegi claimed, “I think we have maintained a balance, we have avoided opting for lower standards. There are lots of areas where, if you rest to agree, high standards will be sacrificed. But if you insist on high standards, it can take a long time or some countries might drop out. So all 11 countries are on board”9. Generally speaking, the legal texts from both agreements remain the same, with the exception that all references to the United States have been deleted. Also, the most important changes that have taken place among the 22 suspended provisions have been in relation to property rights and investment. Overall, the provisions that were eliminated with the creation of the CPTPP were seen as too far-reaching and extensive for most of the members that constituted the agreement. This suspension has lessened significantly the reach and scope of the CPTPP in comparison to the TPP (Goodman 2018). This could be one of the reasons why Japan might now be able to act as a leader in the region.

31

5.1.2. Japan’s regional strategy

As seen along this paper, since the end of the Cold War, the emergence of China as a leader in East Asia has shaped the structure of the international relations within the region. More specifically, China’s increasing military budget and economic development have challenged Japan’s attempts to exercise leadership in East Asia. This situation has triggered a need for Japan to balance against China’s growth (Terada 2010 in Black 2017:152). One of the main pillars of Japan’s strategy to counterbalance such threat and exercise leadership in the region was the establishment of the TPP, both before and after the US’ withdrawal. As part of this regional strategy, Japan has also promoted the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy’. According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (2017:3), this policy is based on 3 key areas: peace and prosperity, human security and economic diplomacy. When it comes to the third one, Japan aims at ensuring quality growth in developing countries. “[T]hrough that cooperation [Japan] will grow together with developing countries, thereby contributing to Japan’s regional revitalization at the same time”. Moreover, such Japanese regional revitalization will include “the promotion of Japanese technologies and systems in overseas markets” (Ministry of foreign Affairs of Japan 2017:3). Regarding East Asia and Asia-Pacific specifically, the main goal is to “increase in awareness of confidence, responsibility and leadership, as well as democracy, rule of law and market economy […]” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2017:9). The Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy is a great example of Japan’s regional strategy. However, this policy does not only concern East Asia and Asia-Pacific – Japan has also set goals for Africa and the Indian Ocean. This strategy reflects the vision of regional revitalization, market expansion and leadership. The idea behind the establishment of this strategy, then, is to become a regional leader and influence not only neighbor countries, but also other regions. As part of this strategy, Japan is now establishing new FTAs all over the world. For instance, apart from the CPTPP, Japan is also taking part in the negotiations for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) or for the Japan-EU Pact. Nevertheless, given the position Japan is occupying in the CPTPP, as well as the leading position Japan took in the establishment of the agreement show that the CPTPP is one of the most successful cases of Japan’s regional and grand strategy so far.

32

5.1.3. Japanese leadership

As mentioned above, China’s leadership in Asia forced Japan to start playing a more leading role in the region, and the CPTPP is an example of this. This third and last subsection of the analysis aims at analyzing the types of leadership that Japan has exercised in the CPTPP. In order to do so, this subchapter will be divided into three sections, which correspond to the three types of leadership developed in Young’s theory.

5.1.3.1. Structural leadership

Already under the umbrella of the TPP, Japan supported the use of soft power instead of hard power. Mulgan (2016) also argued for this view in previous research. This fact can be reflected in Abe’s speech of ‘The Bounty of the Open Seas’, where the Prime Minister advocated for a world of “freedom and openness, ruled not by might but by law”10. More specifically, referring to the TPP, Abe claimed that “in both diplomacy and security, we are striving to make this region a place based on rules, which is endowed with both freedom and transparency. Japan is poised to proceed down both these paths, which are nothing more than two different names for the same motivation”11.Therefore, due to this fact, it is hard to find clear evidence that backs the view that Japan is exercising structural leadership though the CPTPP.

Nevertheless, there are some hints of this in the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy policy document. There, Japan expresses its aim to develop and lead counter-terrorist measures in the East-Asian region. Also, the country aims at promoting “cooperation on urban infrastructure development by using Japan’s technologies and experiences […] which will lead to the facilitation of […] direct investment by Japanese companies” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2017:3).

All of this has not yet been materialized. For now, it is only part of Japan’s strategy. In the future, these actions could be carried out through the CPTPP. Due to this, for now it is only possible to speculate– no solid conclusions can be reached at this point. Nevertheless, despite not having more evidence, it seems like Japan could be exercising structural leadership in the region through the CPTPP in the near future.