Communication for Development One-year master

15 Credits [Autumn, 2018]

Supervisor: [Oscar Hemer]

Under our own eyes

Mothers in search for consciousness

and social change in Brazil

1

ABSTRACT

This case study provides an analysis on how working women mothers in Brazil articulate themselves in a feminist network born on social media (Maternativa) to generate collective empowerment, raise awareness about oppression and mobilize around work rights. Using qualitative methods such as insider participant observation, interviews and content analysis, it investigates how participatory-related communicative practices and feminism interplay on digital and interpersonal environments fostering dialogue, conscientization and, potentially, a “political turn” in the collective’s agenda. Theoretical underpinnings include Manuel Castells’ network society, participatory communication and Paulo Freire’s theories on oppressed subjects, as well as insights from matricentric and black feminisms. The validity of (feminist) participatory practices for the strengthening of women mothers’ grass-roots movements and its potential applicability to mitigate the limitations of social media are some of the conclusions offered. Despite challenges typical of social movements and a significant “white woman bias”, participation has been able to produce an expanded awareness of the different systems of oppression. As a result, women’s discourse and engagement inside the network has become increasingly political and critical regarding structural power relations in the Brazilian society.

Keywords: women mothers, work rights, feminism, network, social media, empowerment, participatory communication, dialogue, conscientization

2

Table of contents

Abstract ……….. 1 Table of figures ……….. 3 Table of tables ……… 3 1. Introduction ……….…. 4 2. Background ……….. 5 3. Literature review ………..…… 7 4. Research questions ………. 10 5. Theoretical framework ………... 115.1 Network society, mass-self communication and refuge ………. 12

5.2 Participation, dialogue and conscientização ….…………...……...… 13

5.3 Matricentric and black feminisms ……….. 13

5.4 Mumpreneurship, meritocracy and collaborative economy ………... 15

6. Research design ………..…… 15

6.1 Methodology ...……….……….…..15

6.1.1 Insider participant observation ……….………. 16

6.1.2 Content analysis of user web-based content ………..… 17

6.1.3 Semi-structured interviews and software coding ………... 18

6.1.4 In-depth interview and grey material …………..………... 20

6.2 Limitations and reflexivity ……….… 20

6.3 Ethical questions ……….… 22

7. Analysis ……….………. 22

7.1 Facebook affordances ….……… 23

7.2 Dialogue, sororidade and acolhimento ……….. 27

7.2.1 The role of face-to-face ……….. 32

7.3 Motherhood and feminist awakening ………. 35

7.4 “Mumpreneurship” and the political turn ………...… 42

8. Conclusion ………. 49

9. References ………..……… 51

3

Table of figures

Figure 1. Desabafo (screenshot of post) ………..……… 25

Figure 2. Facebook fan page (screenshot) ………..………. 26

Figure 3. Eliciting question (screenshot of a post from moderation) ……..…….... 28

Figure 4. Live streaming (screenshot) ………. 28

Figure 5. Acolhimento (screenshot of post) ………...………..…… 31

Figure 6. Cafeína (picture) ……….. 33

Figure 7. Cafeína (screenshot of live streaming) ………. 33

Figure 8. “Mothers move the world” (one of Maternativa’s mottos) ……….. 35

Figure 9. Mothers not welcome (screenshot of post) ….………. 36

Figure 10. Feminism (screenshot of post) …..………. 38

Figure 11. Call for Black women (screenshot of post) ……… 39

Figures 12 and 13. Designs used in Maternativa’s materials (screenshot) ……..… 39

Figure 14. Maternativa’s market place (screenshot) ……….…40

Figure 15. Black women´s voice (screenshot of post) ………. 41

Figure 16. “About us” on Facebook (screenshot of page) ...……… 43

Figure 17. Representation of the “mumpreneur” on Google (screenshot) ……..… 44

Figure 18. The new motto (screenshot of design piece) ………... 45

Figure 19. “Respect for mothers in the job market” (screenshot of post) ………... 47

Figure 20. “Buy from mothers” (screenshot of Instagram post) ………. 48

Figure 21. Maternativa fair (screenshot of Instagram post) ……… 48

Table of tables

Table 1. List of informants for semi-structured interviews …...………..… 184

1. Introduction

In the last decade, Latin America has been experiencing an intensified feminist wave. Coined as “Women’s Spring” in academia and media, this momentum has been characterized by the centrality occupied by the internet in women´s articulations (Burigo, 2015; Matos, 2017), as well as by a high degree of diversity, differing itself from other feminist movements around the globe.

In Brazil, such characteristics have been opening space for a multiplicity of identities, such as feminist mothers. As a Brazilian citizen, I have been observing a crescendo of networks of women mothers1 who seek, in the intersections of the digital and the "real life", transformations that extrapolate classic feminist demands and embrace questions concerning different systems of oppression. As a journalist, I have been writing about the subject since I believe that this is a fundamental contemporary phenomenon on which there is still incipient literature (O'Reilly, 2017). Finally, as a feminist mother, I am engaged in the studied network as an active member since 2015, and have been making sense of its development as a referential voice in the Brazilian women´s movement in the last years.

The present case study is, thus, a contribution to the inclusion of women mothers’ voices in academia from this insider perspective. Through the investigation of the communicative practices of Maternativa, a network of Brazilian “mumpreneurs” (“new-born” women mothers who give up the formal labour market and grow

self-owned/small business2), I explore whether and how the use of social media has been

“enabling new and powerful forms of (women’s) counter-power” (Castells, 2007, p. 246). I also investigate the extent to which feminist and participatory-related

communication practices interplay and inform processes of conscientization, empowerment and mobilization.

These and other aspects of the study are explored in the next chapters. First, context, empirical object, and concepts are presented. Previous works in three major

epistemological fields of interest – social (media) movements, participatory

1 The term, instead of “mothers”, was intentionally chosen in order highlight that the identity of “woman”

precedes the role of “mother”, and not the other way around as it is normalized in patriarchal societies.

2 https://www.theguardian.com/women-in-leadership/2014/sep/17/mumpreneur-working-mother-proud-job-divides-opinion

5

communication and women’s studies – are then discussed in relation to my research. Following, the theoretical framework chapter outlines the main theories chosen – among others, Manuel Castells’ network society and mass-self communication, Paulo Freire’s liberating pedagogy, and matricentric and black feminisms.

In the methodology chapter, the choice of case study is justified, and the data collection methods, as well as the categories produced, presented. Following, the analysis chapter details the investigation of the empirical data collected through interviews, posts, videos and grey material in the light of the theories, and how they relate to the three

“moments” I propose in the scope of the study. The most relevant findings are further explored in the conclusion chapter.

2. Background

All around the world, working women mothers “suffer a penalty relative to non-mothers and men in the form of lower perceived competence and commitment, higher

professional expectations, lower likelihood of hiring and promotion, and lower

recommended salaries” – a phenomenon coined by sociologists as motherhood penalty (Correll, Benard and Paik, 2007). In Brazil, despite the existence of protective policies3, women mothers exclusion starts on job interviews - when, for instance, they have maternity plans questioned or are rejected for being mothers of babies or small children. At workplaces, mothers experience devaluing and a general lack of preparedness to address the special needs and demands of pregnant, breastfeeding and mothers returning from parental leave4. Cases of discrimination, work overload, moral harassment and dismissals during pregnancy are rampant but rarely lead to lawsuits against employers partially because of the cultural acceptance of the problem.

Motherhood in Brazil means also a working “death-sentence” for millions of women in form of wage devaluing, dismissals and doors closed at the job market. A study

published in 2017 by Getúlio Vargas Foundation, a Brazilian policy think tank, found

3 Brazilian labor laws and Federal laws prohibit discriminatory treatment toward pregnant women and

mothers – for instance, “new-born” mothers cannot be fired at least until 30 days after the return from parental leave. In addition, there are specific laws safeguarding topics such as the right to breastfeed during work time and have access to public daycares.

4 Four to six months for mothers, 5-20 days for fathers. Parental-leave is, therefore, called “maternity

6

out that almost 50% of the women interviewed were dismissed or had quit their jobs in the formal labour market in a period of only 12 months after returning from maternity leave (Machado and Pinheiro Neto, 2016). For the “survivors”, having a child can mean a salary decrease of up to 24%, reaching up to 40% if the family decides to have more kids (Gavras and Brandão, 2018; Ottoni, 2018). This scenario helps to explain why women mothers and, particularly, solo mothers from lower-income classes, represent one of the most socioeconomically vulnerable groups in Brazil.

Hence, today 52% of the new microentrepreneurs in Brazil are women, and about 78% of the 7.3 million of self-employed women (or 31% of the total of Brazilian

entrepreneurs) are mothers (Sebrae, 2016)5. The object of study of the present thesis,

Maternativa, was born from this reality as a closed group on Facebook. In 2015, Camila

Conti and Ana Laura Castro, two Brazilian young professionals who had experienced motherhood-related dismissals and discriminations at work, started the network by inviting women to use the space to share their challenges on balancing self-employment and motherhood in the Brazilian patriarchal context. In three years, Maternativa turned into the biggest Brazilian network for “mumpreneurs”, with more than 22 thousand members from all states.

Initially focused more on personal introductions and product/service pitching,

Maternativa’s initial call for “mothers ready for enterprise” – the network’s first motto - related to the discourses around entrepreneurship typical of the last years in Brazil6. In its initial stage, the community was mostly a place for “mother-to-mother” 7 networking,

providing essentially mutual support, information and collaboration on business-related issues. However, as the exchanges started including an intensified sharing of the

motivations behind deciding to start something by its own, critical feminist debates became also the daily bread of the collective. Through compelling testimonials, the

maternativas (as they use to call each other) voiced the widely spread and normalized

culture of exclusion of women and, in particular, mothers in the Brazilian work world and society in general.

5 Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service (Serviço Brasileiro de Apoio à Micro e Pequena

Empresa)

6 Critics of this trend poses that entrepreneurship is becoming Brazil’s “new religion” (Carvalho, 2016) 7 Inside Maternativa, this is translated into practices such as swaps, co-working and in a discourse around

7

Four years later, Maternativa has turned into one referential voice in Brazilian media and feminist blogosphere advocating for the transformation of “the relations between mothers and the labour market”. Being at the same time a network for mutual support and a platform for articulation around women mothers’ work rights, it resonates with the “citizen perspective” on communication for social change proposed by Thomas Tufte. This perspective includes community-based efforts usually considered “less ‘noisy’ and not as articulated as some of the more recent social uprisings” but equally capable of social transformations (Tufte, 2017). As a node in the Brazilian renewed feminist movement, the collective works also as a convergence point of three relevant struggles in Latin America, today – the liberation of women from the historically constructed and romanticized ideal of motherhood, a movement called maternidade

real8 (real motherhood); work justice and equality for women; a cultural turn concerning historically constructed gender roles and norms. In the present study, I investigate how social media, participatory communication and feminism play a role in those developments.

3. Literature review

In the long list of literature on the role of media and communication for social change, there is a significant stream of contemporary studies focused on (digital) media-centric dispositions. They attempt to make sense of the myriad of new forms of communication in relation to questions of power, structure, agency, dynamics. (Castells, 2010; Jenkins, 2006; Benkler, 2006).

While these scholars have brought compelling accounts of the internet era, they have been paying less attention to social and symbolic processes performed on the digital. Referring to Shirky (2010), Couldry (2012) makes a significant critique of this gap noting that "political and social change requires much more than a technological

opportunity" (p. 61) and introduces the concept of "media cultures" relying on different types of human needs. According to him, practices born out of specific inequalities, contexts and conditions can shape many innovative ways to use media for political and

8 Some referential actors of this incipient movement are the youtuber Helen Ramos (Hel Mother: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC8t_vJsGzOERkFdanDKTDhw), the NGO Casa Mãe (House Mother: https://www.facebook.com/casamaeong/) and the platform A Cientista que virou Mãe (The Cientist who became Mother: https://www.cientistaqueviroumae.com.br/)

8

social change and life improvements. His argument is part of a stream of recent studies proposing a renewed look on "how cultures and attitudes underlying the use of

communication technologies help us to move beyond technologically deterministic positions with regard to the influence of the Internet on organizing practices" (Kavada, 2014, p. 359).

Echoing this debate, Gerbaudo and Treré add the claim for the reassessment of the collective identity on the studies of social (media) protest movements in the detriment of the instrumental view of the “nature of technological affordances” (2016, p. 868). This position relates to the configuration of the Maternativa network as it seems to be highly informed by a “shared collective identity” (Diani, 1992: 1) of the “mumpreneur” and, therefore, a comprehensive concept. Hemer and Persson (2017) also call attention to the current multidisciplinary momentum where theories have been less media-centric and attracting different areas within humanities and social sciences. One example of this turn is the recent work of Thomas Tufte (2017) on cross-fertilizing dynamics among media, communication, citizen engagement and social change. As his work suggests, this moment means new perspectives for studies which have been produced in a "silos" logic, but also a challenge in terms of how to put in practice a more holistic approach to the field.

However, to ignore that digital networks are part of the “communication ecology of social movements” (Kavada, 2014, p. 359) would be contradictory to the claim for a more open-ended view of how communicational communities and networks grow (or not) towards social change – and how tools, solutions, strategies and practices created on digital spaces have also a role in shaping those cultures. Once the majority of the interactions of the maternativas happens on Facebook and Instagram, studies about the structure, context and functioning of those platforms - such as Jill Rettberg’s Blogging (2013) - have a particular significance for my research process. It addresses new

dimensions of the blogging phenomenon, such as the increased importance of posts and visual content sharing, which have decisive implications for modern communication and social networks. Although the substance of the content shared by the maternativas was the primary focus of my analysis, Facebook blogging features were also important sources of reflection about the extent to which the digital plays a role, and how, on contemporary citizens articulations.

9

Additionally, some studies on communication for social change and participatory communication (Servaes, Jacobson and White, 1996; Tufte and Mefalopulos, 2009) were particularly relevant for this research given the nature of Maternativa’s

communication dynamics. On the one side, Paulo Freire’s liberating pedagogy ideas (1970), specifically dialogic communication and conscientization, seem to be central to understand what kind of engagement is performed by the members of the collective. On the other, contentions surrounding the participatory-hype were considered. I find

particularly significant the questions raised by Martin Scott (2014) about some blind-spots left behind on the relation between media and participatory communication. Can any process be called participatory if its facilitator is a priori biased by its power position? To what extent do new technologies really matter for the fostering of participation – at least as Freire conceived it? Can the oppressed speak if the digital is divided and exclusive, and the media landscape is informed by a specific political economy?

I found all these reflections very useful for bringing balance to my research, however, the attempt is not to conceptualize what participatory communication really is but, instead, reflect on what kind of “participation” I am talking about. In this sense,

scholarship on contemporary local women’s movements and feminism, in particular, in Latin America and Brazil, becomes central to providing the social, cultural and political context in which Maternativa’s exchanges take place. In the first place, referential works addressing global development and women’s movements offer a historical background of women’s struggles for rights and transformations on gender power relations, local politics and public policies. (Basu, 2017; Visvanathan, Duggan, Wiesgersman and Nisonoff, 2011). Secondly, an incipient but growing academic attention paid to the “new” Latin American feminism, with welcome research on movements such as #niunaamenos in Argentina and #meuprimeiroassedio

(#myfirstharassment) in Brazil (Martini, 2016; Matos, 2017; Brandão, 2018), have been contributing with new perspectives to Global South’s women movements. The

discussion of the empowering disposition of cyberfeminism and the transformative role of new technologies on women’s lives (Harcourt, 2000; Everett, 2004; Sandoval, 2000; Wakeford, 2000) are present in most of those studies. It points to the implications of the web for enhancing women’s voice and agency in places of the globe where advances such as the right to safe abortion and equal access to education – which have come true

10

for women in many Western countries for decades - are still far from being achieved. Some of these studies, however, risk to lean slightly to “cyber-utopianism” - the “naïve belief in the emancipatory nature of online communication that rests on a stubborn refusal to acknowledge its downside” (Mororov in Scott, 2014, p. 67) – by putting too much emphasis on movements born out of urban, intellectual elites. For this reason, insights from this field were parsimoniously used in my analysis process, even though Maternativa is too an urban grass-root manifestation.

Finally, the feminist perspective and, even more important, the perspective of mothers in academic studies come to be at the same time a comprehensive theoretical framework for this research and a conscious personal political position. Feminist standpoint

theories, which stands for a feminist theory and methodology in social studies in order to give an account of “reality” from a myriad of women’s perspectives, represent a major link between maternativas life worlds of sexual reproduction, family caring and household (Smith, 1987) and their compelling accounts and perceptions of other systems of oppression. Particularly relevant, in this sense, is the work of matricentric feminists who advocate to take mothers’ voices (and in feminism as a whole) out of the academic invisibility.9 (Ruddick, 1989; Rich, 1976; O’Reilly, 2016).

4. Research questions

Given that Maternativa has been showing a growing political voice in the last two years, this study is based on two research questions:

1. How can women’s networks born on the internet evolve into political actors? 2. What role do social media, participatory communication and feminism have in

this process?

Although the two questions are interrelated, I have decided to divide them so I can take a broader approach to the dynamics I have been observing as an insider over the past four years. The first question brings the hypothesis that the network has evolved to a more affirmative political discourse and practice. In addition, it proposes a look on the

9 In a study from 2016, O’Reilly found that content related to motherhood in a sample of books, articles,

teaching plans and thematic panels of conferences on women's studies between the years 2005 to 2015 ranged from 1% to 3%.

11

role of social media for the articulation of contemporary women movements and the “reformulation of the feminist agenda, with new strategies for political intervention and action” (Vieira, 2012).

However, the same question contains the slight mistrust about how far transformative processes negotiated on digital platforms can go. Born in the world's largest social media platform, Facebook, Maternativa is a product of the internet and social media popularization in Brazil in the last decades. But, above all, it is one culturally informed expression of the increased dialogue among the “new feminisms” in Latin America. In the heart of the second question lies, thus, a desire to look at the “social backbone before, then exploring communicational possibilities” (Levy, 2016). Here, I propose to investigate the extent to which feminism as an assumed philosophical stance, and participation as practice, relates to transformative processes and a change in

Maternativa’s level of action. In search for a conceptual framework for such a question, I relied on a parachute-definition of feminism as “the belief in the social, political, and economic equality of the sexes” (Reisenwitz, 2018) and in the general understanding of patriarchy as the “social structure in which men have power over women” (Napikowski, 2018). Another central concept in the study is Paulo Freire’s conscientização

(conscientization or critical consciousness): “the process of developing a critical awareness of one’s social reality through reflection and action”10.

5. Theoretical framework

Departing from a constructivist view that “empirical reality and theoretical conceptions are mutually constitutive” (Blatter in Given, 2008, p.4), the theoretical framework takes in consideration how online and offline communicative practices within Maternativa at the same time inform and are informed by the specific reality of the working mothers11. In order to investigate this interplay, I first identified four broader epistemological fields in which the network is positioned, namely: networks and social (media) movements; participatory communication; feminism and development. Although interconnected,

10 http://www.freire.org/paulo-freire/concepts-used-by-paulo-freire

11 Leaving aside the debate on the unpaid and invisible reproductive and caring work of mothers, the term

“working mother” was used to refer to women mothers who, in the context of this study, are or have been active in the world of productive work.

12

each of these areas relates to what I am calling the “three stages” of the network: the crystallizing of a collective identity and articulation inside a digital platform; the

expansion beyond the limits of the internet, and critical consciousness raising. The main theoretical underpinnings used are as follows:

5.1 Network society, mass-self communication and refuge

In the analysis of this "first (digital) moment" of the collective, I discuss Facebook’s affordances for the articulation of women’s groups in the Brazilian context.

First, I rely on Manuel Castell’s concepts of the network society and mass-self

communication to position Facebook’s centrality in Maternativa’s articulations. In his referential book The Rise of The Network Society, he has argued that digital

technologies have been driving a new social structure “made of networks in all the key dimensions of social organisation and social practice” (Castells, 2010 in Scott,

2014:64). This “network society”, as he calls it, relies on a “mass-self communication” which he describes as “the global web of horizontal communication networks that include the multimodal exchange of interactive messages from many to many both synchronous and asynchronous” (ibid).

Secondly, in an attempt to “culturally localize” Maternativa’s communicative dynamics on the digital, I applied the idea of online networks as places of “refuge and hope” for women in Latin America. Discussed by Carolina Matos in one of the few available analyses of the new feminist moment in Brazil, this idea accounts for the cyberspace as a place where women can exercise voice and agency with autonomy and safety. As Matos puts it:

"…in the Brazilian case, it is not yet possible to talk about a post-modern, post-feminist sensibility, or a dominance of feminism in the media (Gill, 2012), within a reality that mingles elements of the ‘pre’ with the ‘post’ and where the ‘new Brazilian (career) woman’ has slowly gained space within Brazilian society in the re-democratization phase but who nonetheless still struggles to be fully accepted with the mainstream. Online networks thus emerge as a breath of fresh air, a place of hope and refuge from the hardships of marginalization of the offline environment (…)" (2017, p. 419)

By framing Facebook as a place of refuge and articulation around a collective identity of working/entrepreneur woman mother, I could also investigate the significance and limitations of this platform for Maternativa in the specific Brazilian context and apply a less media-determinist approach. This final effort relied also on literature and references about the algorithmic logic, political economy and the digital divide.

13

5.2 Participation, dialogue and conscientização

The analysis of the “second moment” of the network draws on participatory

communication and Paulo Freire’s theories on oppressed subjects, particularly the main principles of liberating pedagogy discussed in his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed

(1968). My choice is motivated by the hypothesis that, although Maternativa is not a

participatory development project but a loose network of citizens, it organically retains most of the essential principles of Freire’s theory.

Freire's work with adult literacy in the Brazilian state of Recife in the 1950s left as its legacy a methodology which became the main influence to participatory approaches to development. Central to participatory development is the promotion of horizontal, participatory (two-way) communication “rather than vertical (…) or trickle-down models, more suited to modernization and growth theories of development” (Lennie and Jo Tacchi, 2011, p. 15). By practicing a collective dialogic communication instead of receiving passively information in a one-way/top-down fashion, learners (or

development project stakeholders) construct of their own education/emancipation – here understood as liberation from oppressive/unjust realities. They become able to “name the world” (Freire, 1987), a process of conscientização (conscientization) which provides for a deeper understanding about the roots of injustices and “how the system itself would have to change to be more just and equal." (Needleman in Visvanathan et al., 2011, p.364)

For this research, I applied participatory communication in social movement

mobilization (Tufte and Mefalopulos, 2009) as a frame to analyse the exchanges among maternativas - both in the online and the offline environments - and some of the

transformations produced in terms of reflection and action. I depart from the perception that, although Facebook affordances discussed in the previous part have an important role for structurally enabling dialogue, it is informed by a collective capability toward horizontality, voice, humility and love, some of the key-concepts in Freire’s theory. 5.3 Matricentric and black feminisms

Maternativa is a declared feminist network whose debates and activism have been generating an expanded consciousness about the different systems of oppression and neoliberal development in Brazil. Thus, insights from “matricentric feminism” theory,

14

developed by Canadian researcher Andrea O’Reilly, were applied to frame the analysis on how motherhood provides for a “privileged account” of oppressive realities.

Matricentric feminism advocates that mothers need a specific feminist approach for being double-oppressed (for being women and mothers).12 In general lines, “the construction of the woman” and femininity implies in the compulsory experience of motherhood – i.e., the engendered notion that female identity is built through motherhood (Choi et al., 2005). Hence, the work of mothering (giving birth,

breastfeeding, raising children, etc.) and caring for the family and the home (including the elderly, animals and plants) has been normalized as the quintessential function of women in society. Over the centuries, societies have been supporting patriarchal oppression based on this argument, while disregarding, marginalizing and devaluing women’s “invisible” reproductive and caring work13.

Complementarily, ideas from Black feminist theorists Patricia Hills Collins and Djamila Ribeiro supported my account for the role of black and “peripheral” mothers for

Maternativa conscientization processes. In the 1980s, Collins proposed an “outsider within” perspective in sociology based on her own lived experiences as a black sociologist inside a white-male dominated academia. She argued that standpoints of people caught between groups of unequal power may imply in self-liberation for them, for other oppressed groups and, potentially, for all humankind. Later on, Kimberlé Crenshaw’s ground-breaking concept of intersectionality (1989) was incorporated in Collins studies on the standpoints of black women in the intersections of the different systems of domination (2000).

Finally, and dialoguing with those theories, I relied on insights from Brazilian

philosopher and Black feminist Djamila Ribeiro. Ribeiro makes an argument for black feminist counter-discourses as fundamental not only in epistemological terms, but as an “assertion of existence” through which the invisible (black women’s perspectives and lives) turns into visible. This movement would be able to open space not only for

12 Matricentric feminism was also supportive to my analysis about how women negotiate motherhood and

entrepreneurship, in an ambivalent relationship of adaptation and criticism.

13 Mothers’ lived experiences, therefore, were central in this research – i.e. during interviews or chats, I

considered children’s presence/interventions, pauses to household tasks, work calls answered with children around etc. as valuable data to account for their standpoints.

15

emancipatory solutions for these groups, but to a turn towards “the model of society we desire” (Ribeiro, 2016).

5.4 Mumpreneurship, meritocracy and collaborative economy

In the final part of the analysis, motherhood as a locus of patriarchal oppression and as a source of empowerment (Rich, 1995), one central idea in matricentric feminism, is further discussed vis-à-vis the term “mumpreneurship”, defined by Richomme-Huet, Vial and d’Andria’s as “the creation of a new business venture by a woman who

identifies as both a mother and a businesswoman (…) motivated primarily by achieving work-life balance and opportunities linked to the particular experience of having

children” (2013). In an attempt to analyse the implication of these positions to the “third stage” of the community - i.e. Maternativa’s political turn - I also apply the concept of meritocracy along with collaborative economy. The idea that the distribution of

resources depends solely on individual merits (Teklu, 2018) inherent to the meritocratic discourse helps to frame the investigation of Maternativa’s relation to the current Brazilian neoliberal and conservative (re)turn. In contrast, Felson and Spaeth’s original concept of collaborative consumption as a “set of practices based on resource sharing in contrast to the traditional capitalist relations of consumption” (1978) supports the discussion of counter-hegemonic discourses and practices inside the network.

6. Research design

6.1 Methodology

As I am too a maternativa, this research was written from an insider perspective and relies partially on an autoethnographic approach that included participant observation in two face-to-face meetings. The field research opportunities combined with the

exchanges inside the Facebook group and the reverberations of Maternativa’s activism on media – which I have been following since the last four years - helped me to make sense of the network as being worthy of attention in the study of communication and citizen/social movements. Thus, I chose case study as research method for its possibility to provide an in-depth approach to “a few instances of a phenomenon” (Blatter in Given, 2008, p.2) - in the present research, how social media affordances, participation and feminism intersect in processes of conscientization and political articulation inside a

16

support network for “mumpreneurs”. The research design consists of four combined methods:

6.1.1 Insider participant observation

During the whole process from the first ideas for this project to the performance of in-depth strategies, I kept an insider participant observer stance. Participant observation can be defined as "the process of learning through exposure to or involvement in the day-to-day or routine activities of participants in the researcher setting" (Schensul, Schensul, and LeCompte, 1999 in Kawulich, 2005). In case studies, this technique is usually related to a naturalistic approach, which makes the ontological assumption that there is a “single objective reality that is independent of human observation” (Blatter in Given, 2008, p. 4). For this research, the data collected using this method was used in a more constructivist way, helping understanding abstract meanings which construct and are constructed by concrete observations – for instance, how (if so) sociality in

Maternativa’s meetings are pinned down by feminism and participation.

Being personally engaged in debates, exchanges and mobilizations as a maternativa since 2015, I occupy an insider, interactional and constructivist position. This means that I have been exchanging contents and opinions, making sense of the network and collecting (previous) insights for my research since then. In 2016, I was also in one of Maternativa’s face-to-face meetings, Cafeína (Caffeine), as a participant. The notes I took during the meeting, despite being mostly of personal interest or connected to my ideas on a future research, were a fundamental complement to the material “officially” collected. It helped me to make a deeper sense of women´s interpersonal dynamics and was, therefore, a valuable material to my research.

In order to use these previous insights and others which came in a more organic fashion as I interact with the group on a regular basis, I ask for formal consent of Maternativa’s moderators in 2018. As I live in Sweden since 2014 and follow Maternativa mainly through its main social media platforms (Facebook and Instagram), most of those interactions were made online through posts and comments, and a few texts I wrote for the collective’s blog14. In may 2018, I posted in the group that I was finally starting my research and collecting data, and invited women to participate in semi-structured

17

interviews. Since then, I intensified my observations of the dynamics of the group in comments and posts, and attended a live streaming of a Cafeína held in June 2018 with the explicit goal to observe and collect data following the main guidelines of participant observation.

6.1.2 Content analysis of user web-based content

In the second moment of my long research process, I applied content analysis to a sample of 66 excerpts of posts and comments extracted from Maternativa’s Facebook group. The selection was made based on the main categories of threads observed inside the community, as follows: outbursts, calls for support, personal introductions,

messages from the moderation, tips, acknowledgments, guidelines, calls for action/mobilization and feminism.

Krippendorf (2004, p. 18) defines content analysis as “a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from data to their context”. Focused on the examination of the artefact (texts, images, etc.) of communication and not on the individual, it is an unobtrusive yet context-sensitive technique (Berelson in Kim and Kuljis, 2010, p.340) which helps to detect particular attitudes, preferences, opinions and behaviours by content frequency of occurrence.

My goal using this method was, first of all, to provide for a more “objective, systematic and quantitative examination of communication content” (Berelson in Kim and Kuljis, 2010, p.369) in order to minimize biases inherent to inductive methods such as

interviews. In a first moment, thus, I coded the material using MaxQDA software in an open-minded way (as much as my own biases allowed), looking for the most used words in the selected sets of posts and comments. It is important to note, however, that this coding process was inevitably biased since the categories of choice of posts, because of their relevance in terms of occurrence, were a priori connected with my research questions.

Because of that, the identification of categories followed “naturally” the criteria of searching for patterns (Benaquisto in Given, 2008, p. 2) which could validate (or not) my research hypothesis. The number of words such as feminism, feminist, gratitude, inspiration, sisterhood, empathy, action, union, together, strong, empowerment, work, motherhood, children, challenge, hardship, obstacle, solo-mothers, mumpreneur, and

18

others related to the universe and struggles of working women mothers, were therefore superior than business, tools, advertisement, success, opportunity, partnership, social media, sells, finances, etc. As a result, the final categories reflected the feminist and participatory dynamics of the exchanges among the maternativas. The most important for the scope of this research, and which I used all the way in my analysis, were “mutual support”, “collective mobilization”, “participation and dialogue effort”, “displays of affection”, “collective identity sense-making”, “feminist un/consciousness”,

“matricentric feminism”, “oppression systems”, “class and race discourses”, “black feminism” and “relation with neoliberalism”.

6.1.3 Semi-structured interviews and software coding

In the third moment of my research process, I performed semi-structured interviews by Skype or Whatsapp audio/video function to a sample of eight maternativas (table 1). My choice for this method was based on its usability for “research questions where the concepts and relationships among them are relatively well understood” (Ayres in Given, 2012), which I believe is the case of this research.

The sample of informants was formed based on successful feedbacks I have gotten from a post, in the group on Facebook, inviting those “who have a minimum of one year of active participation in the group and identify with women’s struggles”. My main goal with the interviews was to get a closer understanding of how the group makes sense of the affordances of Maternativa’s communicative strategies, and the transformative potential of the network both in individual and collective terms.

Tabel 1. List of informants for semi-structured interviews

Name* Status Media used

Ana Pereira Group member Skype Cleise Lima Group member Skype Janaina Yoko

Nascimento

Group member Whatsapp

Juliana Santos Group member Skype Letícia Felix Group member Whatsapp Luciene Group member Skype/Whatsapp

19 Rochael

Roberta Rezende

Group member Whatsapp

Thaise

Pregnolatto de Mello

Group member Whatsapp

*All interviewees authorized the use of their real names

The interviews were carried out in Brazilian Portuguese during May and June 2018 and followed a list of questions divided into four parts related to four broad themes:

identity/belonging, participation, conscientization, inspiration/transformation (Annex 1). I kept a flexible mind regarding the questionnaire – e.g. asking additional questions to further explore some specific issues brought up by the informant, or simply discharging questions which were not applicable to the ongoing talk. Following standpoint feminist theory, I also sought to approach their lived experiences as mothers while performing the interaction – e.g. the fact that five of them had to handle children’s demands while being interviewed. By doing this, I strived to capture more closely how they

“conciliate” their roles as workers and mothers, and contextual questions such as material conditions and family situation.

The content was then transcribed and coded using MaxQDA software. The most relevant categories produced related to collective awareness of feminism in general and of the diverse feminist standpoints, especially that of Afro-Brazilian and the mulheres

periféricas - women living in the impoverished outskirts of the cities. In-vivo codes

supported the construction of conceptual categories such as “sisterhood” (sororidade), “welcoming” (acolhimento), “privilege”, “consciousness”, “organicity”, “conflict”, and “horizontality”. Different from the coding process performed upon the posts and

comments, the interviews revealed categories intensely related to development model critique, such as “neoliberalism failure”, “meritocracy”, “mumpreneurship hype”, “solidary economy”, “corporative responsibility” and others. In addition, the coding process brought up the role of Maternativa’s network in individual and collective transformative processes.

20

6.1.4 In-depth interviews and grey material

In the final phase of the research, I compared the results of the content analysis of posts and comments with the analytical categories produced based on the interviews, and performed a final in-depth interview (Annex 2) with one of the founders of Maternativa. In addition, I sent topic questions to two others moderators, who answered me by email and messenger (table 2), and performed focused readings of documents such as

guidelines and articles on media. The material helped me to understand the strategies adopted by the network, its institutional challenges and its developments in terms of discourse and practice. My focus in this phase of the research was to make sense of Maternativa’s “movement” towards a more political stance, which relates to my research question/hypothesis.

Tabel 2. Informants for in-depth and topic questions

Name* Status Type of

interview Ana Laura Castro Group founder, moderator Additional questions Camila Conti Group founder,

moderator until mid-2018

In-depth

Viviane Abukater

Group moderator Additional questions * All interviewees authorized the use of their real names

6.2 Limitations and reflexivity

To discuss the limitations of my research process, I depart from the central idea that reliability and validity are not concepts of major epistemic status in qualitative research once “researchers can observe the world only from a particular place in that world” and “all that is available to us are different linguistically mediated social constructions of reality” (Smith in Lewis-Beck et al., 2011, p. 2, 3).

This is relevant once being an insider puts me in an extra biased position in relation to my research. On the one hand, being a maternativa was a strength, especially in the case of the interviews, once it facilitated “developing intimate, trusting and empathetic

21

relationships” which makes “respondents feel able to disclose the truth” (Gomm, 2004 in Newton, 2010, p. 6). Most of the interviews, because of that, turned into “natural exploratory” conversations were the women openly shared their life stories, concerns, suggestions, opinions and (self)reflections. The use of a common mother language was also a facilitator in terms of understanding and cultural barriers.

On the other, this position meant a permanent challenge in terms of identification and mitigation of the effects of biases and preconceived ideas influencing “what is and is not worth discussing” (Newton, 2010, p.4) during the conversations with the maternativas. The use of the leading question “Do you think participation in Maternativa is

democratic?” instead of “What do you think about participation in Maternativa? is an example of this bias. It might have caused the “demand characteristics” effect, i.e “when the interviewee’s responses are influenced by what s/he thinks the situation requires” (Newton, 2010, p.5 referring to Gomm 2004).

Besides, some stories told by the women triggered emotional response as I too have experienced some of the oppressive situations narrated. My evaluation is that, although those moments of empathy and connection enabled rich data, self-reflection and a deeper dive into the interviewee’s life worlds, they also represented barriers for a more distanced and objective approach.

The same goes in the case of participant observation. As I am a member of the group studied, my stance of observation was participant as observer, which brought me some advantages in terms of access, acceptance (from the group) and trust. However, this also meant that there was at least some level of “trade-off between the depth of the data revealed to the researcher and the level of confidentiality provided to the group for the information they provide.” (Kawulich, 2005).

Moreover, my position as an insider made self-reflection even more important in the case of this method. In participant observation, understanding “how his/her gender, sexuality, ethnicity, class and theoretical approach may affect observation, analysis, and interpretation” (Kawulich, 2005) is fundamental because of the nature of the method – direct, relational, often empathetic. My main effort to fight that effect was to “recognize those biases that may distort understanding”, replacing them with perspectives that

22

could make (me) more objective” (ibid)15. I also used other complementary methods in order to avoid the likelihood that the researcher “will fail to report the negative aspects of the cultural members” (ibid) if relying only on participant observation.

Furthermore, to deal with questions related to my own experience of oppression or privilege meant to deal with emotions and pre-concepts in my native language, which eventually influenced my writing process as well. This fact brought an extra element of caution once this work intends also to critically discuss some aspects of Maternativa that can be improved. As much as my “blind spot” allowed, therefore, I tried to keep my research process opened to hidden meanings and divergent perspectives.

Finally, I am a white middle-class woman from the suburbs of São Paulo, the richest Brazilian city, and Maternativa itself is a network of mostly white feminists. It meant also a precaution in terms of how to interpret and size many aspects of the network, i.e. to keep in mind that the horizon of oppressions in Brazil are diverse and gets worse the poorer the population is. I found this ground-wired attitude productive towards a work that is intended to reflect on the different realities in which all Brazilian women live. 6.3 Ethical questions

Regarding ethical issues, the most important was that both interviews and posts and comments brought up a couple of sensitive testimonials, e.g. discrimination and harassment at work, family and social conflicts. In order to preserve the integrity of women, I asked for their consent for use of the data provided (Annex 3), leaving the use of their real names as an option in case they would expressly allow it. I also chose to refer to sensitive issues in a more generic way so as to avoid exposure in quotes, and erased all information that could facilitate or enable the identification of subjects.

Authorizations for the use of images were also collected with Maternativa’s moderators.

7. Analysis

In the first and second parts of the analysis, I discuss the affordances of Facebook for Maternativa and other women’s groups in Brazil, and how they articulate participation

15 For instance, while taking notes, I included observations about my feelings, attitudes and reminders

reflecting on something said or done, e.g. “I feel sorry for her when she said that”. Later, those notes helped me to interpret my data more critically by reflecting on what triggered my feelings, and why.

23

and dialogue in the digital. In the second part, I investigate how insider participant observation in face-to-face meetings enabled essential complementary insights on Maternativa’s participatory practices. The third part is dedicated to the discussion of conscientization processes inside the network. In the final part, I make an argument about Maternativa’s turn to a more political stance.

7.1 Facebook affordances

As already mentioned, Maternativa was born as a closed Facebook group for mutual support and strengthening among working and microentrepreneur women mothers. Despite the aggregation of new tools in response to the network’s new goals and needs16, the platform remains until today, four years since its first post, as the place where new members join the network, get in contact with its guidelines and principles, introduce themselves to older members, and where the majority of everyday exchanges happens. Facebook’s microblogging functions “enabling individual users to share content (text, videos, images…) to others” (Rettberg, 2013, p. 66) are, thus, central in Maternativa’s communication practices. By “making it easier for groups to self-assemble and for individuals to contribute to group effort without requiring formal management” (Shirky, 2008, p. 21), it provides for maternativas’ mass-self

communication (Castells, 2010) through the sharing of texts, videos, links and pictures “from many to many”.

The interactions observed inside Maternativa also point to the remaining importance of Facebook to citizen mobilizations in Brazil17, especially in the case of women. Besides having “access to conversation” (Shirky 2011 in Scott 2014, p. 66), the maternativas frequently make sense of the group as a door to exchanges which provide not just quality information on micro-entrepreneurship but a better understanding of feminism and issues related to women’s struggles. To Castells, mass-self communication “enhances the opportunities for social change” by affording the users of the new technologies autonomy to produce communication with the potential to make “new values and new interests (…) enter the realm of socialised communication” (ibid, p. 65).

16 For instance, an online marketplace (https://maternativa.com.br/) where the mumpreneurs can find each

other’s services and products, an Instagram profile (https://www.instagram.com/maternativa/) for pitching mothers’ works and advocating for collaborative consumption, and a business day-workshop for women.

17 In July 2018, Brazil occupied the third place in number of Facebook users - 130 million. Source:

24

Ana, who started a group for mutual support for women and mumpreneurs inspired in Maternativa, perceives this transformative aspect:

What is most interesting is the fact that anyone (…) can at any time start a discussion, start a network, a chain ... at any moment. (…) It is the actual power of connection that the network provides. (…) Things happen in a very free and organic way. (...) anyone can join the network today and start a mobilization that will generate some change.

Hence, in the Brazilian case, Facebook groups promote something else than just “transform sets of geographically dispersed aggrieved individuals into a densely connected aggrieved population” (Diani, 2001, p. 388). They fill up the function of "refuge from the hardships of marginalization of the offline environment” (Matos, 2017, p. 419) for women, and recall the role of social media as allowing "communities to realize that they shared grievances" (Howard and Hussain, 2013, p. 3). With

approximately 600 new members joining the group per month, according to Camila (one of the creators of the network), Maternativa’s growth rate on Facebook points to the significance of this media for women’s articulations.

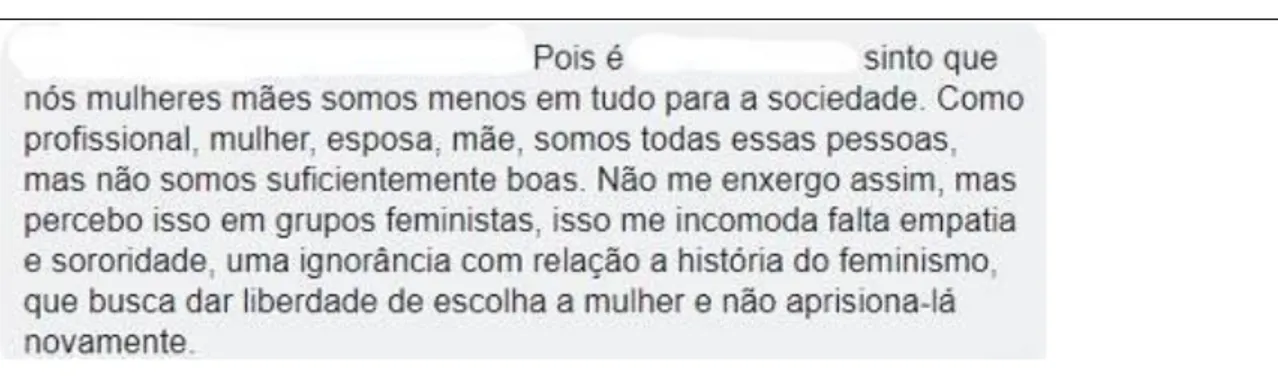

This aspect as also highlighted by the maternativas in posts, comments and was also mentioned in some of the interviews. The description of the network as a place of “encounters”, “recognition”, “exchanges” and “support”, among other terms used by them, suggests that, rather than a tool or channel “carrying certain messages”, Facebook operates as a stage where “ritual and symbolic nature of communicative processes” takes place (Gerbaudo and Treré, 2015, p.867). The sense of belonging to a “shared collective identity” (Diani, 1992, p. 1) of entrepreneur/working mother is exercised in the contact with the “other” living in similar conditions by the exchange of compelling testimonials, life stories and social critics, among other issues, in post-and-comments at Maternativa’s feed on Facebook. Through this practice, the group transcends its more pragmatic goal to promote information and practical exchanges on entrepreneurship and integrate shouts of women who are tired of discriminations, injustices and lack of respect within the family, the society and the labour market. The desabafos (outbursts) are among the most representative examples of this dynamic – figure 1. Those stories represent a space where women’s voices which are normally not recognized in the "offline" world can be shared and articulated.

25

Figure 1. Desabafo (screenshot of post)

“I was an outsourced worker in an NGO when I got pregnant. I was fired in the eighth month of pregnancy. And I'm suing it even with the whole world telling me that the third sector is small and that I'm never going to get a job in an organization because of it.”

Notwithstanding, the internet and Facebook’s limitations play an important role in Maternativa’s dynamics as well. Despite its popularity in Brazil, Facebook’s algorithmic logic and commitment with market-led and political forces rather than community interest18 highlight the contradiction - for social movements and networks

advocating for freedom and social justice - of using proprietary platforms (Castells, 2012, 2015, p. 178). Moreover, the critique of the real disruptive potential of those tools once the web is informed by the “material reality of the global political economy of new technologies” (Daniels in Matos, 2017, p. 420) leaves room to further questioning of how far mobilizations centred on digital media can reach.

Maternativa, as other Facebook-born social movements/groups, operates within this ambivalent space. The interactions among its members happen in an environment whose algorithmic logic along with effects of the specific characteristics of the Brazilian digital divide19 brought together mostly middle-class women mothers. The creation of the network reflects a legitimate struggle for change as job market exclusion and discrimination concerns all Brazilian working women mothers. But it is reasonable to argue that Maternativa’s formation has also to do with a hegemonic discourse lead, in the social and traditional media, mostly by urban citizens with higher formal education. The idea of “entrepreneurship” as a silver bullet for unemployment, discrimination at the labour market, self-fulfilment and for a promised “active motherhood”, i.e. the “utopia” of balancing work life and motherhood, resonates with the reality of women

18 See Facebook-Cambridge Analytics data scandal:

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/cambridge-analytica-facebook-influence-us-election

19 Driven by the popularization of smartphones and other mobile devices, the percentage of households

with connection increased from 13.6% to 57.8% in Brazil between years 2005-2015. However, this advance did not reach the poorest - only 32.7% of the people with an income less than ¼ of the minimum wage accessed the internet in the reference period of the survey, while it reached 92.1% among those earning more than 10 minimum wages. (IBGE, 2018)

26

who can chose this way of life, not with the life of the majority of Brazilian mothers. Maternativa, in this sense, not only “preaches to the converted” (Kladerman in Crossley 2002, p. 174), but preaches mostly to a privileged converted on social media. When asked if the group on Facebook is democratic, the interviewees show awareness about this limitation:

I found it democratic from my point of view (…) I'm white, with high education and full of privileges. (Roberta)

I think that there is a natural socioeconomic cut in there. (Juliana)

I think it's democratic, but I find it still a bit elitist because I see fewer mothers of lower social classes. (Janaína)

In an attempt to “break the bubble”, the network has been actively working to voice the cause in traditional media since its formation. In addition, it maintains a fan page on Facebook and a profile on Instagram20 (figure 2), currently with approximately 16 and 21,5 thousand followers respectively. Both are used as platforms were the network can advocate for a wider audience, potentially attracting more voices from different

backgrounds to the closed group. Other efforts include welcoming plurality both into the online environment and in the Cafeínas.

Figure 2. Facebook fan page (screenshot)

27

7.2 Dialogue, sororidade and acolhimento

As previously discussed, there is an internal movement inside Maternativa to dialogically articulate on Facebook. Although the collective does not operate

affirmatively according to participatory communication, in part because of its original focus on exchanges of a more individualistic nature, its communicative practices retain relations with some of Paulo Freire’s central concepts, which I discuss next.

To Paulo Freire, dialogue is “the encounter between human beings in order to name the world” – i.e. an open and free interaction that leads to a deeper understanding of the roots of inequalities and injustices. A truly dialogic communication is able to give “voice to marginalized groups, time and space to articulate their concerns, to define their problems (…) and to act on them” (Tufte and Mefalopulos, 2009, p. 11). The result of dialogue is action-reflection-action, or conscientização, an empowerment process that is based on “reflection on problems, but also the integration of action - the attempt to act collectively on the problem identified” (ibid), ultimately leading to a shift in power imbalances rooted in society.

In the interactions among the maternativas, the practice of free and open critical exchanges can be observed both in the online and offline environments. Some

interviewees mention that there is an affirmative disposition to “inclusion” at the basis of Maternativa’s communicative dynamics, even though they are mostly digitally

mediated. They recognize this commitment not only in the network’s list of principles -

itself product of a collective effort to systematize contributions of several women - but in a daily effort to translate values such as empathy, respect and transparency21 into

meaningful exchanges. “Different from the others”, “a different approach”, “philosophy in practice” were some of the expressions used by the women when making sense of this aspect.

The work of the moderation group in keeping this spirit alive is one particular feature of how the maternativas communicate on Facebook. Similar to the role played by the “catalyst” in Liberating Pedagogy, the moderators help to facilitate “a dialogue whereby collective problem identification and solution would take place” (Tufte and

21 Feminism, women’s empowerment, empathy, affirmative policies, concern with childhood,

transparency and ethics, articulation, collaborative economy, social transformation and respect to differences are the 10 guiding principles of Maternativa closed group.

28

Mefalopulos, 2009, p. 11). This dialogue uses to happen in a very organic and

unstructured matter in the daily exchanges through posts and comments where women collectively make sense of their struggles. However, it becomes evident when the moderators use the space to actively hear women by means of queries and calls for debates (figure 3), an aspect with direct relation to the “problem-posing dialogue” proposed by Freire: thought-provoking questions which are used “to invite participants to reflect critically and collectively on their own experiences in order to unveil the true reality of their oppression and its causes” (Scott, 2014, 53).

Figure 3. Introducing eliciting questions (screenshot of a post from moderation)

Deconstructing – and reconstructing – our idea of entrepreneurship

Women, I would like to bring some questions which I have been seeing here inside the group and which I think are very important for us to discuss. Let us talk about this?

Additionally, opinions, demands and reflections shared by the maternativas are frequently used as a basis for the implementation of new strategies (figure 4). Here, a relation with the engagement of stakeholders to “explore the situation and define the needed change” (Tufte and Mefalopulos, 2009, p. 15), another key-stone in

participatory communication, is demonstrated. Figure 4. Live streaming (screenshot)

29

One recent example of participatory dynamics inside the network was the series of “lives” produced in response to a recurrent debate on Maternativa’s face-to-face reunions and digital platform: how to “conciliate” motherhood, time and work.

“Horizontality” and “organicity”, relating to the perception that there is no real hierarchy at play inside the group, were also mentioned during the interviews. They include the work of the moderators who are able to "moderate themselves too", in the words of Letícia, in the sense of submitting their interactions to the same rules of the collective. "There is a very strong coherence between what they preconize and they what they do", reflects Ana.

As the moderators are the people in charge of the administration of the group – e.g. to answer all inbox questions, promote face-to-face meetings etc. – some power imbalance is of course at stake. As Scott (2014, p. 73) pointed out, participatory communication has its contentions as well, and the role of the facilitators in acting as a “catalyst in the empowerment of others” often means to deal with “marks of their origin” (Freire, 1970, p. 42) – i.e. their own biases. Thus, critics on attitudes read as arbitrary, such as sudden deletion of posts that ended up in quarrels, and “lack of empathy” toward women

refractory to feminism, were mentioned by some women in the interviews. Direct critics towards moderation are expressed on the Facebook group as well.

However, besides the existence of conflicts, the findings point that the heart of dialogic communication according to Freire, i.e. humility, love, faith and hope (1970, p. 107), generally inform the exchanges facilitated by the moderation group. Critics,

dissatisfaction or disagreement are usually treated with empathy and an intention

towards mutual understanding. A conscious effort to welcome all the views of women is frequently noticed, even though they are divergent or even "anti-feminist". Perhaps most importantly, the moderators often recognize mistakes and express awareness about the fact that they are also learners “creating a collective by collectively creating it”, in the words of Camila.

30

Reflecting on the instrumental relevance of dialogue against the dehumanizing potential of technology and the “confirmation bias”22 effect on social media, one interviewee

states:

(…) one thing that I find very challenging and that is apparently happening is gathering people from very different visions together. Of course, the network has a guideline (…) but I realize that every time a very divergent opinion appears, there is an effort in trying to discuss it, to see points, the pros and cons... (…) Looking from the outside of this experience as someone who has also worked with social movements and communication, I think it is incredible that they can do this at that moment, especially aggravated by the political polarization in Brazil.” (Juliana)

Finally, when making sense of the way they communicate, some maternativas point also to “honesty” among mothers who “can be who they are” inside the network because "everybody is in the same boat" (Cleise words). Once in a “refuge” with a clear feminist and participatory approach, they can be opened about the reality of their lives as

mothers and as working/self-employed women in a patriarchal country. They can share flaws and failures which, in other spaces, would never be received with empathy by a society that continues to double oppress them: “first, for being women; second, for being mothers” (Mendonça, 2017, p. 500). In Ana words:

… everyone can talk, everyone is welcome. Nobody has to be ashamed of having struggles, because everyone is struggling. No woman there has to fake she is a “winner” or happy.

Connected with this idea, the term sororidade (the Portuguese word for the feminist concept of sisterhood), appeared frequently in posts, comments and were stated several times during the interviews. Black standpoint feminist and sociologist Patricia Hills Collins defines sisterhood as “a supportive feeling of loyalty and attachment to other women stemming from a shared feeling of oppression” (1986, p.522). In the real world, sisterhood is controversial as any other kind of empathy and has been quite banalized in feminist discourses23. Notwithstanding, a common perception among contemporary feminists is that, although difficult, it is an inspiring and powerful disposition toward women’s strengthening and liberation because of its potential to challenge the

“patriarchal strategy of divide and conquer” (Dill in Collins, 1986, p. 521).

22 The term was coined by English psychologist Peter Wason, who demonstrated, in an experiment

performed in 1960, the existence of a cognitive bias shaping the human inclination to relate to information in a way that confirms pre-existing beliefs or ideas.

23 In 2017, sororidade was one of the most googled words in Brazil, suggesting both the increased

31

Some maternativas express the perception that there is a conscious effort inside the network to translate sisterhood into real practice. As Ana explains:

… and this thing to break this competition, that a woman has always been taught to compete with another woman (…) I think that is revolutionary (…) The effectiveness of feminism is changing from sisterhood, from the more sympathetic and more connected look to the other. (…) This thing in Maternativa is fundamental.

They call this disposition acolhimento: a mix between “being welcomed whoever you are”, and “supported with no need for paying back”. Inside the network, acolhimento is enacted through certain practices. The most common are expressions of gratitude or encouragement through affectionate comments (figure 5). Eventually, they can evolve into the offering of emotional and informative support, or even work-tasks in inbox conversations. “She did the service for me and did not accept payment. She just said that we are there to support each other”, tells Thaíse. Often, they mean mobilizations to rescue women in and outside the network from situations of domestic violence or economic vulnerability, in spontaneous and instantaneous callings in which dozens of women engage.

Figure 5. Acolhimento (screenshot of post)

However, although this ethics lies at the heart of Maternativa’s communication

dynamics, the collective is not immune to obstacles typical of grass-roots networks and social movements. Maternativa is usually successful in the translation of horizontality, humility and love into dialogue, sisterhood and welcoming, but some important

conflicts have been posing challenges and self-reflection. Not all women have the same understanding of feminism, and not all discussions about those different perspectives have a positive end. Besides, the prevalence of the white woman voice informing the general discourses of the network has been also criticized. To produce cracks in this logic and advance an amplified agenda have been both a task of the black and

“Mothers… and friends because that is how I see you in the group… Never give up… fight… seek knowledge… and do what you love to do and not because it is your obligation.”