“No one knows who refugees really are”

Discourses around the ‘refugee crisis’ in Poland

Analysis of selected mainstream media articles published from 2014 to 2017

Matylda Jonas-Kowalik

International Migration and Ethnic Relations Master Thesis 30 credits

Spring 2020: IM639L

Supervisor: Anders Hellström Word count: 21,761

Abstract

The so-called refugee crisis was among the most significant events affecting European political and social structures during the previous decade. Previous research proves that the questions regarding refugee reception had instigated a rise of ethno-nationalistic and exclusionary sentiments across Europe. The Polish context has been a clear example.

This study aims to analyze the ways in which Polish media produced and reproduced the discourse pertaining to the refugee crisis and subsequently the perceived representation of refugees. Based on the review of literature and theories of discourse, mediatization, politicization and Othering, selected mainstream media articles from 2014 to 2017 were analyzed. The findings illustrate that an exclusionary discourse and Islamophobic notions were prevalent during this period. Moreover, the results indicate that a discursive shift regarding the representation of refugees has occurred, significantly altering the manner in which Polish society perceives both refugees and the refugee crisis more generally.

Keywords

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Acknowledgements……….………1

1. INTRODUCTION………..………2

1.1 Introduction………..………..…….………..……….2

1.2 Research problem………..………3

1.3 Aim and research questions……..……….……4

1.4 Academic relevance and contribution……..………..5

2. CONTEXTUAL BACKGROUND……..……….6

2.1 European Union……..………6

2.2 Poland……..……….……10

3. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND ……..……….12

3.1. Previous research……..………..12

3.1.1 Previous research in the Polish context.…….………..………14

3.2. Theoretical framework……..……….16 3.2.1 Discourse……..……….17 3.2.2 Discursive shifts……..………..……18 3.2.3 Mediatization……..……….……..19 3.2.4 Politicization………..………22 3.2.5 Othering……..……….………..22 4. METHODOLOGY……..……….24 4.1 Method……..……….24 4.2 Data analysis……..………28

4.3 Material……..………..….…….29

4.3.1 Selection of the newspapers……..………..29

4.3.2 Selection of the articles……..……….30

4.3.3 Typology of the articles……..……….32

4.4 Reflexivity……..………..……32

4.4.1 Role as researcher……..……….….….33

4.4.2 Ethical considerations……..……….………34

4.5 Limitations……..………34

5. DESCRIPTIVE FINDINGS……….35

5.1 Identifying the refugees……….………36

5.1.1 Refugees, immigrants, economic migrants?………..37

5.1.2 Religion, ethnicity, nationality…….………..40

5.1.3 Gender, age, sexual orientation……….….42

5.1.4 Other characteristics………..43

5.2 Identifying the reasons.……….44

5.2.1 War and conflict……….44

5.2.2 Economic reasons………..44

5.2.3 Other reasons……….………45

5.3 Identifying threats……….45

5.3.1 Threats of violence………45

5.3.2 Consequences of cultural differences………46

5.3.3 Diseases………47

5.3.4 Financial strains………47

6. ANALYSIS……….………..48

6.1 “No one knows who refugees really are” - the representation of refugees and the refugee crisis……….48

6.1.1 Implications of considerations of legal and administrative status…….……48

6.1.2 Discourse around identity of refugees……….….….50

6.2 Production, circulation and distribution………..52

6.2.1 The circulation and distribution of the selected newspapers…..…….…52

6.2.2 Understanding the typology of articles………..…..53

6.3 Media, politics and the refugee crisis……….….54

6.3.1 Politicisation of the refugee crisis……….…..……….54

6.3.2 Media as the most important source of information…………..………..55

6.3.3 The dependency of media on political institutions………..56

6.3.4 Media logic or political logic?………58

6.4 Discursive shift……….………..59 7. CONCLUSION……….………..61 List of articles……….64 1 .Gość Niedzielny……….….….64 2. Polityka……….………..…….68 3. Newsweek Polska……….………71 4. Sieci……….…….73 5. Do Rzeczy………..………..……….……76 Bibliography ………..………79

Table of figures and tables Tables

Table 1. European Union — population and asylum application 2014-2017………9 Table 2. Poland — population and asylum application 2014-2017………..11 Table 3. Selected newspapers — data……….………..30 Table 4. Numbers of articles mentioning legal and administrative status of newcomers

in 2014………..………..………..……37 Table 5. Numbers of articles mentioning legal and administrative status of newcomers

in 2015………..………..………..…………38 Table 6. Numbers of articles mentioning legal and administrative status of newcomers

in 2016………..………..………..39 Table 7. Numbers of articles mentioning legal and administrative status of newcomers

in 2017………..………..………..……40

Figures

Figure 1. Total number of people who arrived to the EU………….……….…….7 Figure 2. Four-dimensional conceptualisation of the mediatization of politics……….….…..20 Figure 3. Fairclough’s three-dimensional model for critical discourse analysis……….……..26 Figure 4. Number of articles published between 2014 and 2017……….……….36 Figure 5. Correlation between public opinion and number of articles………..60

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my thesis supervisor, Anders Hellström, for his support and guidance. His knowledge, comments and patience have been exceptionally helpful and greatly appreciated. My extended gratitude also goes to Linnea Adebjörk, Ebru Calin and Noah Godin for their continuous support and encouragement, without which writing this thesis would be a much more difficult task.

1.

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Introduction

The migratory event that reached its peak in 2015 and was characterized by the exceptionally high number of people arriving at the borders of the European Union overland or from across the Mediterranean Sea came to be known as the European migrant crisis or refugee crisis. Even this relatively small number of new arrivals — 1,032,408 people coming to Europe in 2015 which represented only 0,002% of the total population of European Union (UNHCR, 2020) — proved to be a very significant factor in its political climate, with effects lasting to this day. Although not a single one of the European Union member states ranked among the top ten hosting countries in the world (UNHCR, 2016), the influx of refugees choosing Europe as a destination can still be seen as unprecedented, comparable only to refugee movements during and succeeding World War II, when an estimated 40 million people had been displaced in the region (Chalabi, 2013). This immediately begs the question — who were the refugees that came to Europe? One of the most universal definitions, stemming from the The 1951 Refugee Convention, defines refugee as “someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion” (UN General Assembly, 1951). This definition will be adopted for the purpose of this study. However, the discourse produced regarding the refugee crisis is much more complicated than a simple legal definition.

For many the ‘crisis’ became synonymous with the countless media images and descriptions of people fleeing their homelands and trying to reach safety in Europe — on overpacked boats, with children and the elderly, with the little possessions they were able to carry with them. For others, it was represented by the pictures of young men illegally crossing the border, mass migration motivated by economic reasons, religious extremists and the threat of political havoc in the European Union. Both of these discourses were present in the media and both influenced the perception of public opinion, which in many countries had little to no first-hand experiences with refugees. One of those countries, Poland, — demographically homogenous and geographically positioned far from Greece, Italy and other states that were first to interact with these asylum seekers — will be the focus of this study which aims to

analyze the media discourse of the ‘crisis’ and its implications.

The structure of this thesis will continue as follows: first the aim and research questions will be introduced, followed by the detailed contextual background necessary to understand the political and social situation of the crisis in the European Union. Next, the context will be expanded by the presentation of previous research done on this topic, an introduction of the theoretical concepts that are crucial for conceptualizing the ‘crisis’ and the representations of refugees in Polish media that are the core interest of this study. Following the theoretical background, a discussion on the methodology of this study will be presented, together with the criteria and material chosen for the analysis. Last but not least, the descriptive findings followed by the analysis will be detailed and the study will reach its conclusion.

1.2 Research problem

Since attention towards refugees and asylum seekers has grown significantly in recent decades, both in the social and academic spheres, the analysis of media discourses can be seen as a way of connecting those two worlds. The subject of refugees became prevalent in the public discourse of the European Union in the wake of the migratory event of interest within this study, and even though it varied between the political spectrum, member states and individuals, the overall conclusions about the societal willingness of refugee reception in some countries were not always hopeful. This is perhaps why the subject of refugees has become increasingly politicized as well as, at times, very divisive, and remains of academic interest for so many — the author included.

Discourse, as elaborated upon in the later chapters of this study, is constantly produced and reproduced, adopted and contested. It can also undergo changes or shifts, especially in the wake of unprecedented situation, such as the arrival of hundreds of thousands of refugees on the shores of Europe. Within the context of this study, a discursive shift will be understood as the change of social functioning of language on the national level (Fairclough, 1992; Krzyżanowski, 2018), that leads to significant changes of the discourse and in effect has a crucial social relevance as an object of the analysis. The so-called “refugee crisis” caused a sharp increase of the news coverage on refugees and migrants in the Polish media (Krzyżanowska and Krzyżanowski, 2018) which had an important role in producing and

reproducing the discourse around refugees themselves. As some researchers argue, this upsurge of media coverage has been “one of the main reasons for a qualitative change in Polish public discourse that has translated into a notable radicalization of exclusionary views” (ibid.: 614). Therefore, the main interest of this thesis lies in the examination of the media discourse from a specified period in Poland with hopes to gain better understanding of the creation of discourse in the context of this discursive shift.

1.3 Aim and research questions

This study aims to analyze how refugees and the refugee crisis were presented in the Polish media, in order to gain a better understanding of discursive shifts in general, as well as the discourse around this migratory event in particular. The discourse over the period of four years, from 2014 to 2017 — before the peak, during the peak and in the period that can be described as an aftermath of the peak of migration in summer 2015 — will be analyzed. The central research question of this study is:

In what ways has Polish media produced and reproduced the discourse pertaining to the refugee crisis and subsequently the perceived representation of refugees?

The specific points of interest represented in the analyzed discourse will be explored with connection to the question written above:

a) Which actors were perceived as central to this migratory event and how were the migrating persons represented in Polish media?

b) What factors were perceived to cause this migratory event and for what reasons, according to the discourse, have these refugees migrated?

c) What perceived threats do refugees pose for Polish society, what is said to be at risk and where does the fear of refugees stem from?

Hence, this thesis will be a qualitative case study of Polish media discourse on the refugee crisis and the discursive shift occurring in this context in the given period. In order to describe and understand how this analyzed discourse emerged, I will focus on mediatization

and politicization of the 2015 migratory wave, with emphasis on the discourse constructed and reproduced by media.

This research will adopt Critical Discourse Analysis, in order to examine how discourse around refugees is linguistically generated in Polish media and what its discursive and social practices are. The selected mainstream media articles that will be the subject of the analysis were published by five Polish weekly newspapers (Gość Niedzielny, Polityka, Newsweek Polska, Sieci and Do Rzeczy) during the period between January 2014 and December 2017. This analysis will be done with close connection to the previous research on the topic.

1.4 Academic relevance and contribution

Much has been written about the increased migration to the European Union in the period analyzed in this study as well as the social and political aftermaths of this event. The discourse that was created and reproduced around the refugee crisis has far-reaching implications both on the international level as well as for the respective member states. With my research, I hope to make a humble contribution to the growing body of literature on the subject of mediatization and politicization of refugee reception in Poland. Additionally, by translating articles from Polish to English and conducting the analysis of the discourse present within them in English, I aim to bring this issue to wider international attention. Analyzing the selected mainstream media articles can illustrate the discursive shift, while also furthering the understanding of this phenomena, in a context broader than in Poland alone.

Lastly, since the migratory event of interest is widely known as the ‘refugee crisis’, — a phrase that is also commonly used in the analyzed discourse — for the purpose of this study I will use the phrase ‘refugee crisis’ and ‘European refugee crisis’ while bearing in mind the potential of reproducing a discourse that may be seen as harmful and oversimplified. This decision comes not without some concerns, since the word ‘crisis’ is seen as bringing a pejorative meaning, which was addressed by worldwide comparative research and its use often debated (i.e Taylor, 2015; Ruz, 2015). However, as mentioned before, having a better understanding of the of discourse regarding refugees as the aim of this study, the material analyzed in this thesis will hopefully provide a better understanding of why the phrase ‘refugee crisis’ has been so widely used. I also aim to emphasize how the mechanisms of fear

people who are different and in some cases described as essentially inferior; subsequently, this research has a societal relevance due to the potential of dismantling harmful stereotypes.

2. CONTEXTUAL BACKGROUND

Since attention to historical and social context is an important part of analyzing discourse, this section of the study will be dedicated to the events connected with the migratory wave of 2015 and how they influenced the politics of the European Union in general, and Poland specifically. Due to the high relevance of those affairs and variety of studies that were dedicated to this topic, the contextual background will be presented with the elaboration on both the procurring events as well as their conceptualization by researchers. 2.1 European Union

The wave of migration that peaked in the summer of 2015 and which is often referred to as the refugee crisis and by others as the “long summer of migration” (Scheibelhofer, 2019: 194) has shaped the contemporary discourse around refugee reception in the European context and continues to have a significant impact on politics in the European Union. Hence, those events and their repercussions are crucial as a contextual background for this study, since they create and influence the discourse that will be analyzed and will be important for sufficiently answering the stated research questions.

With the Syrian civil war and unrest in the Middle East, caused by, among other factors, the 2003 invasion of Iraq and destabilization of the region (Jaskułkowski, 2019), many refugees pursued futures in Europe, which is why the refugee crisis was characterized from the Western perspective by high numbers of people arriving in the European Union. Most followed main roads of migration — from Turkey via the Aegean Sea to the Greek islands (Eastern Mediterranean) or from Libya to Italy (Central Mediterranean), occasionally overland through the Southeast of Europe. To illustrate this situation with numerical data, in 2014, approximately 225,000 people arrived in the Europe Union, while in 2015 it was more than a million (UNHCR, 2016, 2020).

Figure 1: Total number of people who arrived to the EU (UNHCR, 2020)

(The numbers include sea arrivals to Italy, Cyprus and Malta, both sea and land arrivals to Greece and Spain.)

Among those who arrived in 2015, the largest group of asylum seekers were Syrians (56% of arrivals), followed by Afghans (24%) and Iraqis (10%) who fled from their unstable or war-torn countries (International Organization for Migration, 2016).

As response to this situation, there arose two main conflicting approaches to the refugee crisis considered in European countries which were, firstly, humanitarian discourse stressing the need to help people fleeing persecution and secondly, the rhetoric of state security and the need to maintain law and order (Triandafyllidou, 2018). The latter one, connected with the fact that the creation of the single market of the EU was accompanied by the strengthening of external border control, “the war on terror”, outsourcing of border control, a restrictive visa policy, offshoring border control, heavy militarization of borders, and overall securitisation (Jaskułkowski, 2019: 33) caused not only a delayed response to the 1 unfolding situation but also an uncoordinated one. Since this issue of securitisation is directly linked with the research questions, especially of the perceived “threats”, it will be explored in the analysis. Due to these factors, the borders of the European Union became very dangerous: as Jaskułkowski wrote, “migrants, including those who have a legitimate claim to seek refugee status, have very limited opportunities to reach the EU legally and safely” (ibid.: 34).

It should be pointed out that the EU actions has been at times contradictory: on the one

Securitization - version of politicization that facilitates the use of extraordinary means in the name of 1

security (CARFMS, n.d.). It can be understood as a process of social construction that pushes an area of politics, like migartion, into an area of security by using a rhetoric of discursive emergence, threat

0 275000 550000 825000 1100000 2014 2015 2016 2017

hand, some attempts to counteract the humanitarian crisis were made, especially after an extraordinary European Council meeting on 23 April 2015 following the humanitarian disaster in Lampedusa; on the other hand, the EU’s policies, or lack of them (e.g. absence of a common immigration policy, diametrically opposed attitudes and different practices of individual member states), arguably have worsened the crisis (Maldini and Takahashi, 2017). The humanitarian efforts connected to the Dublin Regulations were based on the Geneva Convention as well as the EU Qualification Directive and stated that the aim is to “determine rapidly the Member State responsible [for an asylum claim] and provides for the transfer of an asylum seeker to that Member State.” (Lorca-Susino, 2016: 125). According to some scholars (e.g. Selanec, 2015; Scheibelhofer, 2019; Maldini and Takahashi, 2017) and journalists specialising on the issue (Pai, 2020; Boghani, 2018), European states were neither prepared, nor willing to take responsibility for the arriving refugees, who needed material, psychological and medical support. Where the states failed in their efforts, many regular people and NGOs showed incredible strength and willingness to offer their services, filling the gaps left by the underfunded state agencies (e.g. Gunter, 2015; Kalogeraki, 2018; Bernát et.al, 2016). Yet, although there are many documented cases of personal involvement of groups and individuals in organizing efforts for refugees (ibid.; Scheibelhofer, 2019; Rozakou 2016), many others followed the exclusionist discourse of fear fuelled by the media in certain countries, such as Poland (Krzyżanowski, 2018). Hence, those two conflicting discourses - of solidarity and of exclusion, will be sought in the selected articles in the process of analysis.

For many scholars and experts working on the subject of refugee reception in the European Union, it is clear that the EU has had problems protecting the rights of refugees and did not manage to develop a long-term solidarity-based refugee policy (Maldini and Takahashi, 2017; Jaskułkowski, 2019; Scheibelhofer, 2019). Most of the people who arrived on the shores the EU came from countries that were not politically stable and did not guarantee the fulfilment of human rights. Adding to the definition of refugee quoted in the introduction of this study, the European Parliament defines refugees as “people fleeing their home country to save their lives and who have been accepted and recognized as such in their host country” (European Parliament, 2019a), while asylum seekers are defined as “people who make a formal request for asylum in another country because they fear their life is at risk in their home country” (ibid). Article 14(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

(UDHR), adopted in 1948, guarantees the right to seek asylum, therefore, one could argue that people arriving on the shores of Europe simply exercised their human right of seeking refugee and safety. Hence, mainstream framing of this event as a ‘crisis’ should not be seen simply as descriptive or neutral, as it constructs the discourse suggesting that migrants and refugees are a sudden and unexpected source of trouble (Jaskułkowski, 2019: 32).

Table 1. European Union — population and asylum application 2014-2017

Source: (European Parliament, 2019a)

Even though the EU was not the main destination for migrants and refugees, 2015 was characterized by politicians and the media as the time of the European refugee crisis. As mentioned before and as it can be seen in the data presented above in Table 1, even in the most intense period of migration to Europe in 2015, the percentage of new arrivals made up 0,002% of the total population of the European Union. In comparison, Turkey with a population of 79,81 million in 2017, one of the most important destination points for war refugees from Syria, hosted 4,2 million refugees that year, which made up 0,05% of their total population (UNHCR, n.d.).

According to a survey conducted by the European Parliament in June 2019, immigration was one of the most pressing issues that influenced the voting decisions of Europeans in May’s 2019 EU elections, with 34% of Europeans voting with immigration in mind. (European Parliament, 2019b).

2014 2015 2016 2017

EU total population 506 944 075 508 450 856 510 152 681 511 522 671

Number of asylum seekers arriving in the EU 225 455 1 032 408 373 652 185 139 Percentage of new arrivals to total EU population 0,0004% 0,002% 0,0007% 0,0004% Refugees residing in total in EU 1 090 833 1 326 701 1 863 881 2 283 199 Percentage of refugees in the total population of European Union

2.2 Poland

Poland, which joined European Union in 2004, from the very beginning presented a noticeably cautious and conservative approach to the refugee reception and humanitarian obligations that arose in 2015. This homogenous country can be described as a country of 2 emigration rather than immigration — in 2017, 2,54 million Polish citizens lived abroad (Główny Urząd Statystyczny [GUS], 2018), and 400,000 non-European citizens had a long-term stay visa in Poland. However, it should be specified, that the statistics on the largest foreign-born group, Ukrainians, do not include recently arrived migrant workers (Santora, 2019; Walker, 2019). In 2017, more than 1.7 million Ukrainian citizens worked legally in Poland (Chapman, 2018), which can be connected both with humanitarian (annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation and war in Donbass in 2014), as well as economic reasons.

Immigration was not a major topic in the media, nor in politics up to 2015 (Krzyżanowski, 2018; Bielecka-Prus, 2018). After the systemic transformation in 1989 and in the later years of the post-communist transition, immigration has been limited, mainly consisting of migrants from neighbouring countries — Ukraine and Belarus — whose presence

in Poland was long constituted as national minorities due to the historical changes of borders. The coalition government of liberal Platforma Obywatelska (eng. Civic Platform, PO) and agrarian Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe (eng. Polish People’s Party, PSL) in power between 2007-2015 “reluctantly agreed to accept refugees in the framework of the EU relocation scheme” (Jaskułkowski, 2019: 48). However, negotiations regarding the reception of refugees conducted by the Polish government in the autumn of 2015 coincided with a political campaign for parliamentary elections, which took place on October 25, 2015. Hence, the topic of refugees was used as one of the key program points of political parties competing for votes (Bielecka-Prus, 2018: 7).

Ultimately, the new right-wing government of Prawo i Sprawiedliwość party (eng. Law and Justice, PiS) elected in autumn of 2015 refused to accept the previous agreements concerning refugee reception. In PiS’s campaign in 2015, refugees and migration were one of the most debated and prominent issues, with the party taking a harsh and exclusionary approach to any relocation proposals and a complete rejection of any solidarity-based help for

In the last national census conducted in Poland in 2011, 96.88% respondents reported Polish as their 2

people arriving on the shores of the European Union (Jaskułkowski, 2019).

In effect, Islamophobic discourse in Poland was widely reproduced by the public media, the right-wing press, the Church as well as popular culture (Jaskułkowski, 2019; Krzyżanowski, 2018). This shift has an influence on the discourse that is analyzed in this study, which can also be seen in the numerical data from surveys conducted in this time in Poland. In May 2015, 76% of respondents expressed the opinion that Poland should give shelter to persecuted people, however, this sentiment was directed mainly towards Ukrainians from the war-torn area, while little over half of respondents (53%) did not agree to accept refugees from the Middle East and Africa (MENA) (CBOS, 2015a). In January 2016, the number of responders supporting the idea of asylum for persons from the MENA region amounted to 26%, while in June it was even smaller — 24% (CBOS, 2016).

In 2020 the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that Poland failed to uphold its obligations regarding refugee quotas as required by law (Hursh, 2020).

Table 2. Poland — population and asylum application 2014-2017

Source: (European Parliament, 2019a)

As can be seen in Table 2, the numbers of refugees residing in Poland, as well as the number of applications for refugee status are proportionately much smaller than other numbers in the European Union. The number of accepted applications is very low, which can also be

2014 2015 2016 2017 Poland total population 38 017 856 38 005 614 37 967 209 37 972 964 Refugee status applications in Poland 8020 12 190 12 305 5045 Accepted cases 262 348 390 520 Percentage of migrants applying to total population Poland 0,0002% 0,0003% 0,0003% 0,0001% Refugees residing in total in Poland 15 695 14 065 11 747 12 238 Percentage of refugees in the total population of Poland

attributed to the fact that many refugees decide to leave Poland before their cases are closed by authorities, most often choosing to continue their journey to Western Europe — in 2017, 53% of asylum status proceedings were discontinued (Urząd do Spraw Cudzoziemców, 2018a). Most applications in Poland during the period between 2007 and 2018 were submitted by citizens of Russia (most often Chechens), Georgia, Ukraine, Armenia and Tajikistan (Urząd do Spraw Cudzoziemców, 2018b).

Hence, the discourse of exclusion can be seen as prevalent in the Polish case, with very little public support for refugee reception for people from the MENA region.

3. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

This section of the study will be dedicated to the exploration of previous research and other past literature on the topic. In order to answer the research questions sufficiently, the direct links between the following three concepts must be explained. First, mediatization — phenomena that can occur when the political system is highly influenced and adjusted to how mass media cover politics (Lundby, 2014), Second, politicization — designating a political meaning and character to an issue or concept, and third, the shifts of discourse. While mediatization will be one of the main concepts this study will focus on, politicisation should be seen as a complimentary theoretical framework to explain the importance of bringing the issue of refugees to the public during the Polish parliamentary elections in October 2015. 3.1 Previous research

As underlined previously, the summer of migration was arguably one of the most critical events that has deeply affected the identity and unity of the European Union in recent history. Hence, it comes as no surprise that this subject was, and still is, of the utmost importance and interest for researchers from a variety of academic backgrounds. There have been numerous positions arising on the topics of refugee reception, media discourse as well as the upsurge of Islamophobia and Othering in recent years in Europe. In the vast body of literature regarding this subject, I focus on the particular positions that are interconnecting with the discourse analysis produced by media within the context of refugee crisis perception in the EU, and specifically Poland.

As argued by many researchers, both the new and the traditional media have been key proponents in creating a discourse of fear and have played into the populist and far-right discourses of the “crisis” in the European Union (Krzyżanowski, et.al, 2018; Krzyżanowski, 2018; Modebadze, 2019; Podobnik et.al. 2017). In many European countries, political radicalism and ethno-nationalist mobilisation has 3 4 caused a visible rise in patterns of xenophobic and racist discursive scapegoating and Othering (Krzyżanowski, et.al, 2018.: 4). According to the research by Krzyżanowski and co-authors, the majority of the discourses produced by the “strongly mediation-dependent European politics” were negative and served as a token for far-right and populist political movements. According to Wodak, populism in the ethno-nationalist form is especially prone to employing dichotomous strategies of, on one hand, engaging with the supposed national sameness, unity and cohesion (fallacy of sameness) and on the other hand, drawing a rigid distinction between “us” and other nations or ethnic minorities seen as “them” (fallacy of difference). This leads to constructing oneself as superior and unique (Wodak, 2015:54) and results in the discourse of Othering. Even though many populist right-wing parties are by nature skeptical of the European Union, they invoke the concept of “European identity” when it fits their political agenda (ibid.), which can be observed regarding this discussed migratory event. One of the main discursive changes — a concept that will be elaborated upon in the section dedicated to theory together with discursive shifts — that can be seen in Europe with connection to the refugee crisis, is that in many EU countries, even the mainstream political movements, parties and governments endorsed anti-immigration rhetoric as well as harshened stances toward refugees. This type of discourse before seemed to be visible mostly in connection with far-right and right wing movements (Krzyżanowski et.al, 2018: 7). In “The Mediatization and the Politicization of the ‘Refugee Crisis’ in Europe” authors point out that in the wake of the refugee crisis concepts

Political radicalism can be understood as an intent to transform or replace the fundamental principles

3

and values of a society or political system. It is often achieved through social, structural change or radical reform. Political radicalism is often conceived as protest that challenges the political establishment, however may also be interpreted as new ways of engaging increasingly depoliticized electorates against weak party governments (ECPR, 2017).

Ethno-nationalist mobilisation can be seen as a nationalist political strategy to push a radical social 4

discourse to shape memory and identity politics of the nation state. It combines radical politics with national sentiment. Ethnic nationalism, which sees the nation through the concept of ethnicity, pays special attention to shared ancestry, culture, language, religion and history of the nation. As Mazzini writes, “history is a source of identity power, and, for incumbents, a political one” and, in context of Poland, ethnic-nationalist rhetoric is an “instrument for radicalizing public sentiment and deepening

that are especially vulnerable to politicization — humanitarianism, security, diversity, protectionism — were used in public discourses to sanction the new, harsh restrictions of migration and asylum policies (Krzyżanowski et.al, 2018:1). These are drawing on both the traditional and new forms of discriminatory rhetoric, Othering, outright racism and xenophobia (Krzyżanowski et.al, 2018: 3).

A significant discursive shift can be observed not only on the level of the EU, but also in Polish political discourse (Krzyżanowski, 2018). Prior to 2015, anti-immigration rhetoric was scarce however, now can be characterized as strongly anti-immigrant, Islamophobic, and even racist. As the author writes, one of the central issues that has contributed to the process of politicization of immigration in Poland is the accommodation of debates about the refugee crisis in Europe in 2015 (ibid.: 92). He argues that the heated way in which political debates were conducted has a direct link to the rise of discriminatory public opinions about immigrants, which are especially visible regarding asylum seekers and refugees. (ibid.). In the analyzed texts, describing refugees as a “threat” to Polish culture, religion, and nationhood was prevalent. In Krzyżanowski’s words, “Such a marking of difference spanned a wide range of arguments, starting from cultural/religious incompatibility and ending in radical and blatantly racist statements on biological inferiority that recontextualized elements of Polish historical anti-Semitic arguments.” (ibid.). This change of discourse is identified by the author as “strategic enactment” and is based on the strategy of introducing new ways and patterns of debating certain topics — in this case immigration and refugees - that are in fact drawn from patterns previously used in different debates and discourses (Krzyżanowski, 2018: 78). Discourses were not only introduced to the public but further recontextualized and perpetuated, which in time elevates them to become hegemonic discourses. According to Krzyżanowski, in the case of Poland, this is visible in the connection between historical, Antisemitic discourse and modern, Islamophobic rhetoric (2018).

3.1.1 Previous research in the Polish context

Within the context of Poland, there are many notable works published in the broad area of interests connected with this thesis. Literature dating to the pre-crisis era includes, among others, studies on “othering” and ethnic exclusion — “Constructing “the Other”: The images of immigrants in Poland” by Grzymała-Kazłowska (2007) and “Realms and forms of

ethnic exclusion in Poland” by Jasinska-Kania and Łodzinski (2009), as well as media analysis focusing on nationalist tendencies and prejudice by Starnawski (2003). Bielecka-Prus argues, that in the context of Poland, the research on press discourse about refugees and immigrants is still insufficient, which can be explained by the fact that the conflict with the presence of foreigners was, as mentioned before, almost absent prior to 2015 (Bielecka-Prus, 2018: 13). However, given the literature on the subject, one can conclude that even with the lack of widespread public discourse concerning immigrants and refugees, these topics were indeed still of interest for some researchers focused on migration studies.

As Jaskułkowski writes, three main approaches to study attitudes towards migrants in Poland so far contain: analyzing public opinion polls (quantitative research), analysis of the media and political discourse (qualitative research) and the contextualization of structural and historical processes (2019: 4). This study is aimed to fall into the second category, since my main focus lies in the media coverage of the refugee crisis.

In his book, that aims to connect those three approaches, Jaskułkowski (2019) focuses on the attitudes towards migrants and refugees from the MENA region during the European refugee crisis of 2015-2016 in Poland, based on the qualitative data from interviews and analyzes of the policies by the Polish government and media discourses as well as popular culture. According to his findings, the overwhelming majority of the individuals interviewed for the purpose of his research identified refugees with Muslims, who were deemed to pose a threat to the Polish nation; which might be a direct link to the discursive shift described by Krzyżanowski (2018). This analysis establishes that even though the hegemonic Islamophobic public discourse can be reproduced, negotiated and contested, it was largely adopted in the Polish view of refugees and the refugee crisis. Even among interviewees who adopted a solidarity based approach and invoked arguments of open borders, the humanitarian discourse and the discourse of multiculturalism, the reproduction of some Islamophobic stereotypes remained present (ibid.: 8).

This hegemonic perspective of the refugee crisis is also present in Bielecka-Prus’s “The Rhetoric of the Fear of the Stranger in the Polish Press Discourse” (2018). The author focuses on the “rhetoric of fear” by conducting an analysis of articles published in two main Polish daily newspapers — Gazeta Wyborcza of a more progressive profile, and Rzeczpospolita which holds a more conservative standpoint. Her analysis shows that the

rhetoric of fear and anxiety is present in both texts published in Rzeczpospolita and Gazeta Wyborcza. Names and adjectives used to described refugees appear fearful in both newspapers, especially in metaphorical form (ibid: 28). Clear differences can only be seen in how the themes of shame and guilt were used: the progressive newspaper more often appeared as an accuser, condemning the Polish approach to the refugee crisis, while the conservative newspaper more often assumed the role of advocate for antagonistic views. As the author writes, both press titles engaged in a normative discourse, characterized by a strong emotional charge (ibid.). This study, especially relevant given the topic of this thesis, shows that one should not blatantly assume a stark difference between media outlets of different political leaning when it comes to an issue as dividing as a refugee crisis. As Bielecka-Prus notes, the topic of refugees was so prevalent in everyday discourse, that the information on refugees reached 91% of respondents of a CBOS study, and almost half of respondents (46%) were interested in the issue (Bielecka-Prus, 2018:11; CBOS, 2015b). One of the interesting positions, which is based on the similar foundations as Bielecka-Prus’s work, is an article by Bobryk that looks into discourse analysis of the refugee crisis in the Polish press, analyzing material published in Gazeta Wyborcza and in Nasz Dziennik (Bobryk, 2017 in: Pasamonik and Markowska-Manista, 2017: 46).

The research on this topic has yet to be expanded upon, however one of the few studies related to this issue suggests that, to a large extent, knowledge about refugees was shaped through the media, such as the press, television and internet portals (Pędziwiatr, 2015:132-150). Given the importance of media coverage regarding this issue, and with the aim of contributing to the still-developing body of literature regarding the discourse of refugee crisis in Poland, this study will specifically focus on the press discourse regarding refugees from 2014 through 2017.

3.2 Theoretical framework

Mediatization of the refugee crisis in Poland together with its politicisation of the issue connected with parliamentary elections of 2015, created a change of discourse that can be identified as the Othering of refugees and migrants — labelling them as a threat; different and even inferior to the native Polish population. This change of discourse surrounding the refugee crisis is described as a discursive shift, which is elaborated upon in the following sections of this study.

The theory is based on the previous research that indicates that prior to 2015 a discourse of hostility towards refugees did not exist to the same extent as can be observed throughout and after 2015. This shift is directly related to how this topic has been presented in the media, by politicians and by the clear signs of Othering that now permeate this discourse. Important theoretical concepts — discourse, discursive shifts, mediatization, politicization as well as Othering will be discussed in detail in the next sections of this study.

3.2.1 Discourse

Discourse can be defined as the use of language spoken, written or visual — in a given social context. All social practices hold a discursive meaning — they convey meaning, which shapes

and influences actions (Hall, 1992: 291). The conditions under which the language was used, by whom it was used and why, all influence the understanding of the “object” that is being discussed - “the way in which a particular set of linguistic categories relating to an object and the ways of depicting it frame the way we comprehend that object” (Bryman, 2012: 528).

Discourses are seen as much more than simply ways of thinking and constructing meaning. They define the “‘nature’ of the body, unconscious and conscious mind and emotional life of the subjects they seek to govern” — they shape the world and people’s

understanding of it (Weedon, 1987:108). Hence, language cannot be considered neutral due to the fundamental subjectivity rooted in the relativism of social context and the identity of the user. Fairclough uses the term ‘discourse’ to make the connection between texts and their social purposes - therefore, discourses do not simply reflect or represent social entities or relations, they construct or ‘constitute’ them (Fairclough, 1992). In the context of this thesis, the discourses around refugees will therefore be seen as not only a reflection of certain social and political contexts but also as something that actively constructs them.

As defined by Foucault, discourse encompasses ways in which societies produce meaning and knowledge and is inherently linked with social practices, subjectivity, power relations and relations between all of the aforementioned factors (Weedon,1987:108). Knowledge is inherently linked with power — ‘there is no power relation without the

correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time, power relations.” (Foucault, 1977: 27). According to his understanding of power, one can observe an unbreakable bond between knowledge and power

— power is based on knowledge and makes use of it, while simultaneously, power reproduces knowledge by shaping it (Foucault, 1998). Therefore, in this context, power means having control over the practices constructing both knowledge and discourse as well as what is seen and understood as reality (Fairclough, 2009).

Discourse, being itself both a theoretical and methodological concept, can be used to inspect how shared frames of understanding the world and reality are being produced and reproduced through oral or written sources, in the case of this study — the newspapers. Critical

Discourse Analysis, which is the method adopted in my research, will be explained in detail in the next section, dedicated to methodology.

3.2.2 Discursive shifts

As mentioned in the pervious chapters of this study, discourse is not static, since the language responds to the changing structures of the society and events. Discursive changes, as defined by Fairclough are “a significant shift in the social functioning of language” (1992: 6). Local appropriations of discursive changes — the discursive shifts, are further described as “actor-s p e c i f i c r e s p o n s e s t o w a r d s o c i a l , p o l i t i c a l , a n d e c o n o m i c m a c r o - l e v e l transformations.” (Krzyżanowski, 2018: 78). Discursive change and discursive shift both can be used to conceptualize the changes of discourse, yet they are not synonymical - discursive change is a concept that, on the macro-level, indicates global or transnational framing of public discourse (ibid: 78), while discursive shift helps to identify how and when public and political discourses are changing, becoming politicized and often simultaneously mediatized (ibid.: 79) on the mezzo-level, i.e. state. Hence, the international changes of discourses around refugees can be seen as a discursive change, however, when analyzed in the context of Poland, should be referred to as a discursive shift - responses to social and political transformations that are happening on the macro-level, but are interpreted and reproduced by actors within Polish politics and media. Discursive shifts are often seen as an essential factor within the context of mediatization of politics - which Krzyżanowski understands as a “process whereby politics becomes increasingly dependent on the media and profoundly changes the course and logic of its practices in line with media-driven demands” (ibid.). Therefore, to analyze the changes of discourse that this study focuses on, discursive shift will be one of the central concepts utilized.

Discursive changes and discursive shifts — non-simultaneous, contextual, and field dependent — can be seen in the areas of ongoing securitisation of sociopolitical realities and political radicalization. This plea of securitisation is also a way to legitimize exclusionary measures and exclusionary rhetoric under the guise of national safety (van Leeuwen and Wodak, 1999).

3.2.3 Mediatization

Mediatization can be seen as one key concept to understand the transformation of modern democracies. It has been described as a meta-process together with globalization and individualization (Lundby, 2014: 376). In the context of politics, mediatization has been seen as a process in which politics has increasingly “lost its autonomy, has become dependent in its central functions on mass media, and is continuously shaped by interactions with mass media” (Mazzoleni and Schulz , 1999: 250). One of the most prominent researchers working on the mediatization of politics, Asp (Hjarvard 2013:8–9) defines this process as a “change in which politicians tend to adapt to various constraints imposed by the media” (Lundby, 2014: 351).

By using the term mediated politics, Asp describes the relationship between the media and politics in which media became a necessary source of information between those in positions of power and authority as well as the governed communities and individuals. Mass media is often the main or even the only source of political information which shapes people’s conceptions of political reality. Since in the context of the refugee crisis in Poland, the media can be described as the main source of knowledge about refugees, as touched upon in the previous research, the concept of mediatization is helpful to sufficiently answer the posed research questions.

Strömbäck proposes analyzing the process of mediatization of politics over four different dimensions - this model will be operationalized in this study in order to answer the research questions.

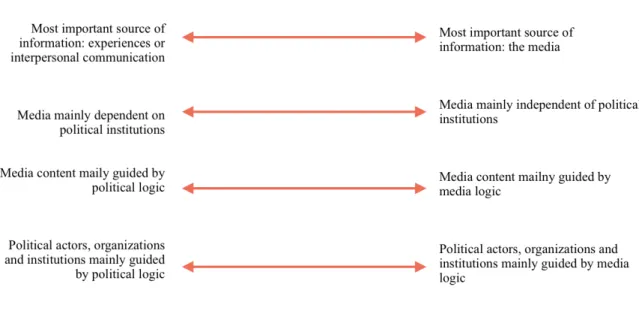

Figure 2. Four-dimensional conceptualization of the mediatization of politics (Lundby, 2014: 378)

The first dimension is concerned with to which degree media constitutes the most important source of information about politics and society, which can be seen as the channel of communication between political institutions and the public (Lundby, 2014: 378). It describes the extent to which politics have become mediated. The second dimension refers to the degree to which media has become independent from other political and social institutions. If the media is differentiated and independent from other social and political institutions, it will be “shaped by the media’s own interests, needs, and standards of newsworthiness, rather than subordinated to the interests and needs of political institutions and actors” (ibid.). This influences both what is being covered and how media covers certain topics. The next dimension describes the degree to which the coverage of politics and society is guided by media logic and not by political logic (ibid.).

Media logic and political logic refer to modus operandi of those respective institutions, and should be understood as “appropriate behaviour that is reasonable and consistent within the rules and norms of the respective institutional context” (ibid.: 381). Rules and procedures can be formal or informal and guide the ways of thinking and acting of those institutions. Political logic is shaped mostly by the framework of the political system of the country in question and the need to be successful on the political level when it comes to wining political power and in affecting policy changes and reforms (ibid.: 383). Media logic

is guided by professionalism (neutrality, transparency, trustworthiness), commercialism (media markets are commercial and outlets need to compete for audience attention), and media technology — “applied communication technologies shape content in production and reproduction processes, as well as the processes of finding or reshaping news to fit the socio-technological formats of different media” (ibid.: 382).

If media is the most important source of information while the media coverage of politics is largely shaped by media logic, political actors have little influence of what and how is covered. This leads to the last dimension, which is concerned with whether those political actors are acting driven by the media logic in order to “influence the media, and through media the public” (ibid). Therefore, the increased power of the media should be seen as both a cause and an effect of the process of mediatization (ibid.: 360). Especially in the case of the creation of knowledge within the intersection of politics and media, hegemonic discourses are prone to be produced — as Marcuse writes, “one-dimensional thought is systematically

promoted by the makers of politics and their purveyors of mass information. Their universe of discourse is populated by self-validating hypotheses which, incessantly and monopolistically repeated, become hypnotic definitions of dictations (1964: 40).

Even though the transformations of politics, media and society and their interrelations can sometimes be seen as over-generalized or over-simplified, mediatization of politics can clearly be seen when it comes to political campaign communication (Esser and Strömbäck 2012a), journalistic approaches toward covering elections (Esser and Strömbäck, 2012b), and voter values and behaviour (Dalton, 2008). This becomes relevant to this study, due to the fact that negotiations regarding the reception of refugees conducted by the Polish government in the autumn of 2015 coincided with a political campaign for parliamentary elections.

The definition of what constitutes the media can be blurred, especially in the era of social media, increased possibilities of content production and reaching the largest possible audience with it. In research on the mediatization of politics, the media that is described as the most important is, as Strömbäck and Esser frame it, “news media as socio-technical organisations and institutions” (Strömbäck 2008; Esser 2013). This means television, radio, newspapers, as well as news magazines in their traditional or digital formats, but also digital news providers that approach journalism in an organized form and recognized criteria. In my thesis, I will analyze, the five most prominent weekly newspapers in Poland, with the criteria

of selection being the largest newspaper circulation: Gość Niedzielny, Polityka, Newsweek Polska, Sieci and Do Rzeczy. All of them fullfill Strömbäck and Esser’s definition of media as socio-technical organisations and institutions.

3.2.4 Politicization

Politicization is a process of designating a political meaning and character to a phenomenon, identity, activity or event. In the Polish context, in recent years the topics of migration and refugees became more prevalent in political debates and in the media (Krzyżanowski, 2018), and therefore, politicized. This is visible in other member states of the European Union as well — in 2019, Felipe González Morales, the Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants for the United Nations publicly expressed a deep concern over how issues of migration and migrants themselves are being politicized and scapegoated in Hungary, saying that “migrants are portrayed as dangerous enemies in both official and public discourses in this country” (UN News, 2019). Some political parties in the EU exploited the political-opportunity of the refugee crisis, by fostering their anti-establishment claims, stressing the need to secure external borders and against further integration (Gianfreda, 2017).

3.2.5 Othering

The term Othering describes the diminishing action of defining and labelling a person or group as different and essentially inferior to oneself. powell and Menendian define 5 “othering” as a “set of dynamics, processes, and structures that engender marginality and persistent inequality across any of the full range of human differences based on group identities” (powell and Menendian, 2017). Due to the high relevance of historical and social background in Critical Discourse Analysis, a method adopted in this study, a short introduction of the significance of Othering has to be provided. The term has its roots in the colonial practices of military conquest of non-white peoples and cultural genocides of European imperialism (Kingston, 2015). In postcolonial studies, the term subaltern coined by Gramsci, designates the indigenous populations of colonized land who are politically, socially

john a. powell chooses to spell his name in lowercase

as well as geographically outside the colony’s hierarchy of power (Liguori, 2015). The practice of Othering served as a justification of physical domination and the destruction colonized people’s culture by degrading them to colonial-subjects and placing them on the peripheral spheres of geopolitical operation of colonial imperialism (Ashcroft, Griffits and Tiffin, 1998: 142; Fanon, 1952; Spivak, 1985). This process can also be described with another Gramscian term, cultural hegemony — domination maintained by ideological and cultural means (Cole, 2020). The ruling-class imposes beliefs, norms and values on the society by manipulating the culture and as an effect, the ruling-class worldview becomes the cultural norm that justifies the status quo of hierarchal structures of the society and injustices (ibid; Bullock and Trombley, 1999: 387–88).

This notion of colonial rhetoric manifests itself in Orientalism, that as scholars concerned with postcolonial studies argue, has a direct influence on European perception of the Eastern world, including the Middle East (Said, 1978). Orientalism, the study and fetishisation of “The Orient”, now referred to as territories of West Asia, South Asia, East Asia, and Southeast Asia, intellectually justified Western imperialism. According to Said, who introduced the wider academic debate on this issue with his book “Orientalism” (1978), the binary relation between “the Occident” — Europe, seen as Western Self and “the Orient” seen as non–Western Other, created the hegemonic discourse of superior European civilization and inferior, uncivilized people of the East. Foucault’s theorisation of discourse (especially the knowledge-and-power relation) describes the cultures that were considered inferior as “a whole set of knowledges that have been disqualified as inadequate to their task or insuffi-ciently elaborated: naive knowledges, located low down on the hierarchy, beneath the required level of cognition or scientificity” (Foucault, 1980: 82). According to Said, this patronizing and discriminatory discourse was, and still is, reflected in art, politics and academic studies that adopted and reproduced prejudiced, outsider-interpretations of Arabo-Islamic cultures (Said, 1978).

The relevance of Orientalism for this study lies in the fact that the Orientalist discourse has an influence on how people from MENA countries are perceived in the European context. This attitude towards Arab and Muslim people as “the Other” is argued to still be present in Western politics and media (Arif, 2018; Shatz, 2019). Said,

as a threatening Other — with Muslims depicted as fanatical, violent, lustful, irrational - develops during the colonial period… The study of the Other has a lot to do with the control and dominance of Europe and the West generally in the Islamic world. And it has persisted because it’s based very, very deeply in religious roots, where Islam is seen as a kind of competitor of Christianity” (Said, 1997; cited in Arif, 2018: 35). The Orientalist discourse was especially visible in the justification of “the war on terror”, which as mentioned before, can be seen as linked with the destabilization of the Middle East. The language of Orientalism during the post-9/11 era, albeit not always explicitly racist, often focused on tropes “putative differences in culture” (Shatz, 2019). Same observations were made in the wake of the refugee crisis in the European Union (Arif, 2018), and will also be of interest in this study. Othering can clearly be observed in the previously mentioned ethno-nationalistic fallacy of difference together with the strategy of singularisation — constructing oneself as unique and superior (Wodak, 2015:54), populist discourse used by political parties as a response to this migratory event, as well as in rhetorical strategies such as the appeal to emotions and the appeal to fear which will be elaborated on later in this study. Othering can be seen as a crucial rhetorical strategy in the discourse surrounding Arab and Muslim peoples as well as refugees, this will be explored in detail in the section dedicated to the analysis with the investigation of “threats” — building of Saids concept of “the sense of Islam as a threatening Other”.

4.

METHODOLOGY

4.1. Method

Discourse analysis (DA), which Gill intriguingly calls “skeptical reading” (Gill, 2000) focuses on how language can be seen as constituting and producing the social world (Bryman, 2008: 500). In other words, it “emphasises the way versions of the world, society events and inner psychological worlds are produced in discourse” (Potter, 1997: 146 in:Bryman, 2008: 500). Moreover, DA focuses on locating contextual understanding when looking into situational specifics of speech and text. Therefore, three basic questions that can guide research employing the DA as the method are: 1) What is the discourse doing? 2) How is the discourse constructed to make it happen? 3) What

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) which will be adopted as a method in this thesis for analyzing the empirical material, focuses on a Foucauldian approach to discourse, that sees the language as a power resource that is related to ideology and socio-cultural change (Bryman, 2008: 508). The critical part signifies that this type of DA aims to “expose connections between language, power and ideology” (Halperin and Heath 2017:338) and the role of discourse is described as “enacting, reproducing, and resisting social power abuse, dominance, and inequality” (ibid.:339). Following this approach, CDA focuses not solely on the text, but also on the relationship of historical, social context of the events and relations of power addressed in the texts that are being analyzed (Bryman, 2008: 508-509). This is connected with the notion of intertextuality, which touches upon the fact that the discourse can be seen as existing beyond the discursive event that is analyzed, and therefore enables the researcher to focus on contexts in which the discourse is situated (ibid.: 509) Hence, the main aim of CDA is both uncovering meanings through analysis of language and uncovering how meanings are constructed in the process of production, distribution, and consumption of the texts analyzed while taking into consideration the perviously mentioned contexts (Halperin and Heath 2017: 377).

Apart from the focus on exploring the stages and aspects of text production, one of the main differences between DA and CDA comes in the ontological considerations - both are rooted in epistemological constructivism, however, scholars grounded in DA tend to represent strong anti-realist tradition, while CDA adopts a critical realist standpoint, that connects the concept of independent reality and the personal perspectives and biases that together construct the world that is knowable and understandable for people through what is ‘observable’ (Bryman, 2008). Therefore critical realists “believe that there are unobservable events which cause the observable ones; as such, the social world can be understood only if people understand the structures that generate such unobservable events” (IS Theory, 2015).

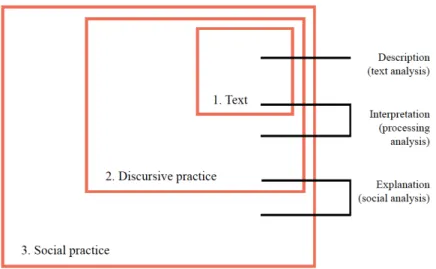

Based on Foucault’s definition of discourse, sociolinguist Fairclough created a three-dimensional framework for CDA, that will be used in this study. This model is based on the authors belief that every “discursive event” should simultaneously be analyzed as a “piece of text, and instance of discursive practice, and an instance of social practice” (Fairclough, 1992: 4).

Therefore, the model presents itself as follows:

Figure 3. Fairclough’s three-dimensional model for Critical Discourse Analysis (Fairclough, 1992: 73)

1. Text analysis

This level of the analysis focuses on the text itself and its linguistic features - content, meaning and structure of the text. The focus will lay on the descriptive layer of the text (Halperin and Heath, 2017). Hence, in this step the linguistic layer of the selected articles will be analyzed. In order to observe the discursive shift, the text analysis will be conducted separately for 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017 — the years this study is concerned with. This level of analysis, will be crucial for answering the research questions, especially “who” are the refugees according to the discourse, “why” are they coming and Othering, with connection to what are the “threats” they are bringing with them.

2. Discursive practice

This level of the analysis focuses on the processes related to the production and consumption of the text — how the text was produced, distributed and consumed (ibid.). On this level, the state of accessibility, scope of publicity and popularity of the selected newspapers as well as who they are aimed for will be taken into consideration. Together with the first step, the processing analysis will be conducted in order to answer the research questions. The mediatization of politics will also be a concept that will be used in order to

conduct the second step of the analysis. 3. Social practice

This last level of analysis focuses on the connection between the text and the social context in which it is situated (ibid.). With the contextual background provided in the second chapter of this study, the mediatization of politics and politicisation of the refugee crisis will be the theoretical concepts that will allow the research to dive into social analysis.

Since this study focuses on the discourses presented in the newspapers, it is crucial to note that media messages are produced, disseminated, and interpreted by the recipients, the process which influences the discourse greatly. This phenomenon was most famously described by Stuart Hall (1973) as encoding and decoding. It underlines the different intentions and interpretations between the actors in the communication process — the encoding of a message is its production, while the decoding refers to how members of the audience are able to interpret and understand this message. This process also depends on the requirements of the actual medium i.e newspapers, TV, social media, and will vary between them. This phenomena is the focus of CDA — not simply analyzing text but also looking at the process and connections between text, discursive practice and social practice.

This “intervention of the medium” as Hjarvard writes, “can affect both the message and the relationship between sender and recipient” (2013: 19). If one defines the media as forms of technology, all technology-supported communication will be seen as “mediated communication” (Lundby, 2014: 7). The use of a particular medium, in the case analyzed in this thesis — newspapers, will alter the outcome of the communication as well as its format and the content — it will have a significant effect on the discourse and the way it is analyzed. Therefore, in order to answer the research question proposed by this study one of the steps of analysis will focus particularly on the level of mediatization of politics in the Polish context. In order to do so, the Strömbäck’s four-dimensional conceptualization of the mediatization of politics, explained in detail in the section dedicated to theory, will be used as a tool to analyze this particular issue.

Hence, the analysis will be based on the Fairclough model — by employing CDA, first text will be analyzed, then discursive practice and, last but not least, social practice. Strömbäck’s conceptualization of the mediatization of politics will be used in the analysis as an additional tool to connect discourse analysis with the concept of mediatization.