A holistic clarification of

the accounting item

goodwill

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Accounting NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonom AUTHOR: Simon Burman & Gabriel Demirel TUTOR: Andreas Jansson

JÖNKÖPING May 2021

Based on acquirers’ perceptions, what is the meaning of the accounting

item goodwill?

Acknowledgments

This master thesis marks the end of a four-year-long pursuit of knowledge and insight. The following is an attempt to express gratitude towards everyone who has been a part of this final composition.

We would first like to thank our families for providing us with the general support and encouragement to complete this concluding project. We would also like to thank our fellow colleagues – we who have shared the same journey. To you, we say thank you for your support during this last time together. Our gratitude goes also to the interviewees of this study, as this thesis would not exist without your participation. But if it was not for our tutor, Andreas Jansson, this thesis would never have seen anything close to its final shape and for that, we are extremely grateful for your support, enlightenment and never-ending encouragement.

It is with these last words we would like to devote our final gratitude to Jönköping University, for providing us with the opportunity, inspiration, and conditions of which in the end has provided us knowledge and experiences that will never be forgotten. Therefore, where the beginning of this four-year-long journey saw a warm welcome shall its final parting see nothing less than a warm farewell comprised of our deepest gratitude.

Jönköping International Business School May 2021

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: A holistic clarification of the accounting item goodwill Authors: Simon Burman and Gabriel DemirelTutor: Andreas Jansson Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: goodwill, business combinations, corporate acquisitions, subsequential measurement, purchase price allocation, impairment, amortization, intangible assets

Abstract

Goodwill is one of the most complex and unclear concepts within financial accounting; it is uncertain what it represents as an asset, it is only recognized during the creation of business combinations and is subject to impairments. The question becomes therefore what meaning is actually to be made from goodwill’s definite appearance as a financial statement line item? Due to a perceived low relevance by users of financial statements, it can be stated that the current narration by the accounting item goodwill fails to meet the fundamental purpose of accounting. Therefore, a study to bring a comprehensive clarification of the accounting item is required where this study attempts to achieve this objective by studying the acquirers’ perceptions of goodwill.

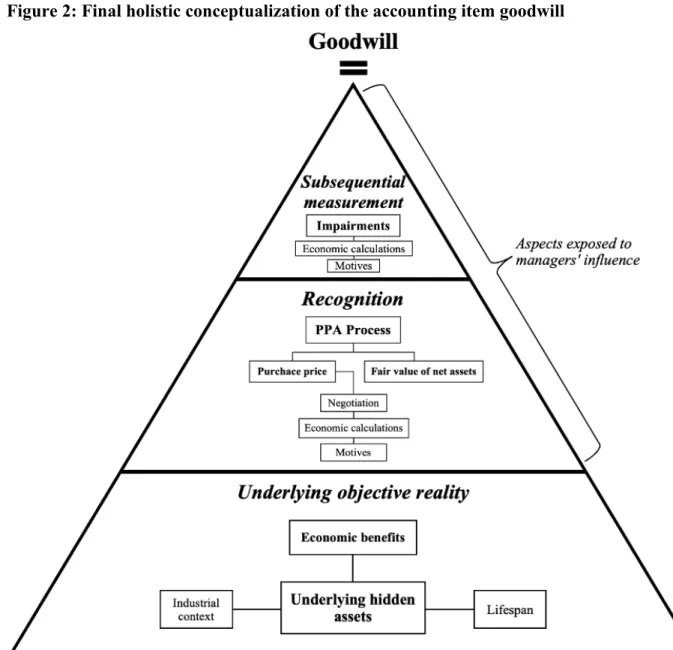

First was a thorough theoretical background established that compiles a wide collection of relevant literature on goodwill. Then were semi-structured interviews conducted with top managers of nine different parent companies who had recently made a corporate acquisition. Based on the most salient perceptions derived from the empirical data in relation to the comprehensive theoretical background, this study obtained the following findings. Goodwill can be understood through three central aspects: the underlying objective reality as an intangible asset, the PPA process and the subsequential measurement process. In relation to the two latter aspects could a fourth aspect of managers’ influence be derived. In an overarching integration, these four aspects could be synthesized into a final holistic model of the accounting item goodwill. This model

ultimately represents a comprehensive understanding of the current accounting item goodwill in financial statements based on the perceptions of acquirers.

The findings of this study can be used to bring clarity to the users of financial

statements when interpreting goodwill and therefore potentially increase its perceived relevance. Foremost can this study’s holistic model be used as a guideline for future research to further elaborate on the understanding of goodwill and generate

Abbreviations

AT Agency theory

CEO Chief executive officer

CFO Chief financial officer

DCF Discounted cash flows

EBIT Earnings before interest and taxes

EBITDA Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization

EMH The efficient market hypothesis

FASB Financial accounting standards board

GT Grounded theory

IAS International accounting standard

IASB International accounting standards board IFRS International financial reporting standard

PAT Positive accounting theory

PPA Purchase price allocation

Table of Contents

1 Introduction ... 1 1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Research problem ... 5 1.3 Research question ... 10 1.4 Purpose ... 10 1.5 Delimitations ... 10 1.6 Key concepts ... 11 2 Theoretical background ... 132.1 Goodwill in financial accounting ... 13

2.2 Theories on the underlying objective reality of goodwill ... 15

2.2.1 The master view ... 15

2.2.2 The economic view ... 16

2.2.3 The hidden assets view ... 17

2.2.4 Momentum theory ... 22

2.2.5 Theory of imperfect competition ... 23

2.2.6 Synthesis of the theories on the underlying objective reality of goodwill ... 24

2.3 Corporate acquisitions ... 26

2.3.1 The process of a corporate acquisition ... 26

2.3.2 Motives behind business combinations ... 27

2.3.3 Synthesis of the corporate acquisition aspect of goodwill ... 30

2.4 The subsequential measurement of goodwill ... 30

2.5 Complementary theories for an increased understanding of the accounting item goodwill ... 33

2.5.1 Agency theory ... 33

2.5.2 Positive accounting theory ... 34

2.5.3 The efficient market hypothesis ... 35

2.5.4 Synthesis of the complementary theories for an increased understanding of the accounting item goodwill ... 37

2.6 Synthesis of the theoretical background ... 38

3.1 Introduction ... 42

3.2 Research design ... 43

3.2.1 General methodological approach ... 43

3.2.2 Choice of data collection method ... 44

3.2.3 Choice of data analysis method ... 44

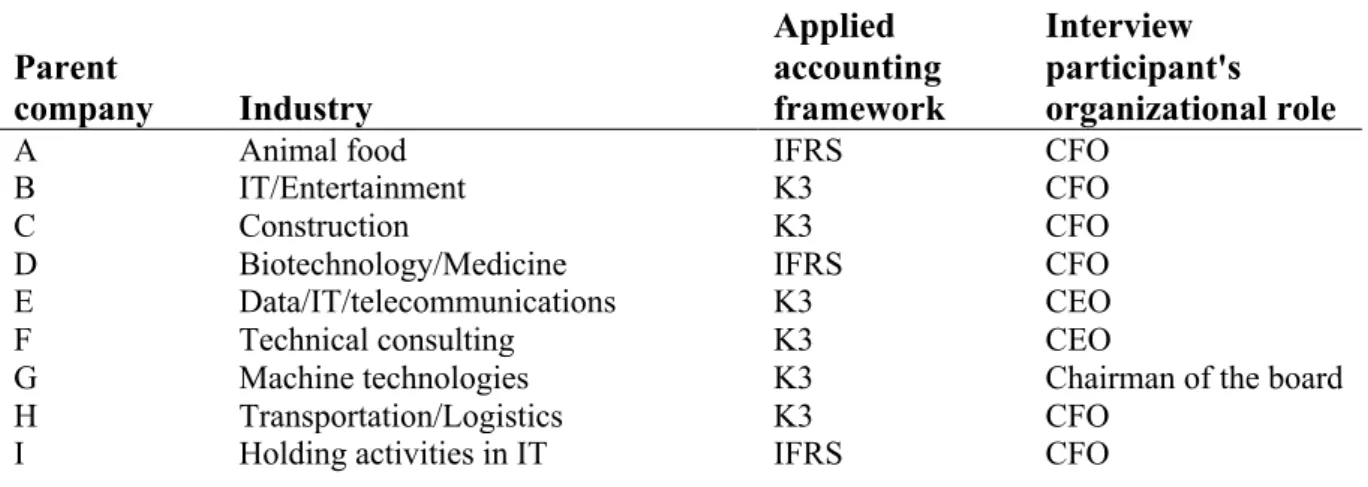

3.3 Sample selection ... 45

3.3.1 Population definition ... 45

3.3.2 The sample ... 46

3.4 Data collection ... 48

3.4.1 The interview guide ... 48

3.4.2 Data processing ... 52

3.5 Data analysis ... 52

3.6 Credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability ... 54

3.6.1 Credibility ... 54 3.6.2 Transferability ... 55 3.6.3 Dependability ... 57 3.6.4 Confirmability ... 57 3.7 Ethical considerations ... 58 4. Empirical results ... 59

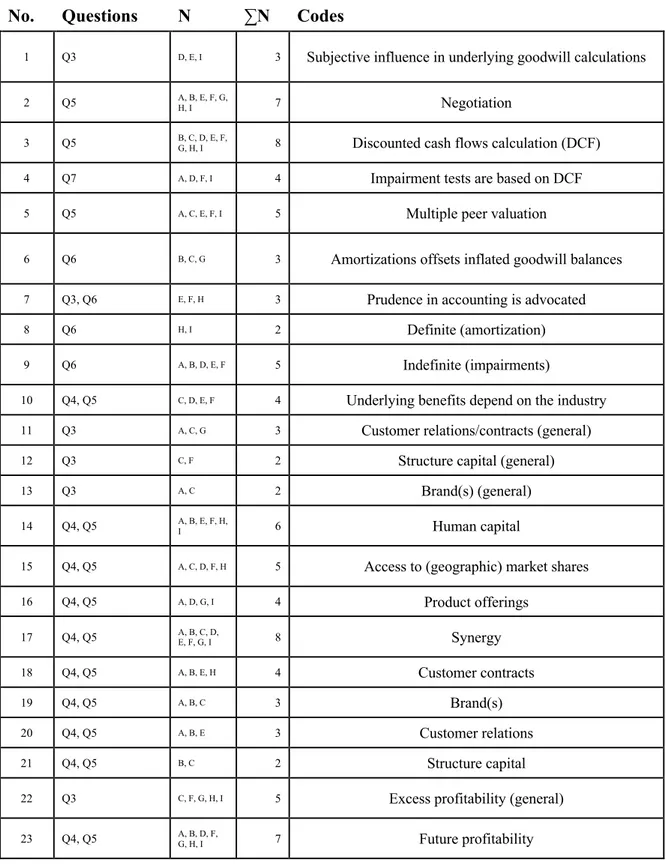

4.1 Code 1: Subjective influence in underlying goodwill calculations .... 61

4.2 Code 2: Negotiation ... 61

4.3 Code 3: Discounted cash flows calculation (DCF) ... 62

4.4 Code 4: Impairment tests are based on DCF ... 63

4.5 Code 5: Multiple peer valuation ... 63

4.6 Code 6: Amortizations offsets inflated goodwill balances ... 64

4.7 Code 7: Prudence in accounting is advocated ... 65

4.8 Code 8: Definite (amortizations) ... 65

4.9 Code 9: Indefinite (impairments) ... 66

4.11 Code 11: Customer relations/contracts (general) ... 67

4.12 Codes 12-21: Different unrecognized intangible assets ... 67

4.13 Code 22: Excess profitability (general) ... 68

4.14 Code 23: Future profitability ... 69

5. Empirical analysis ... 70

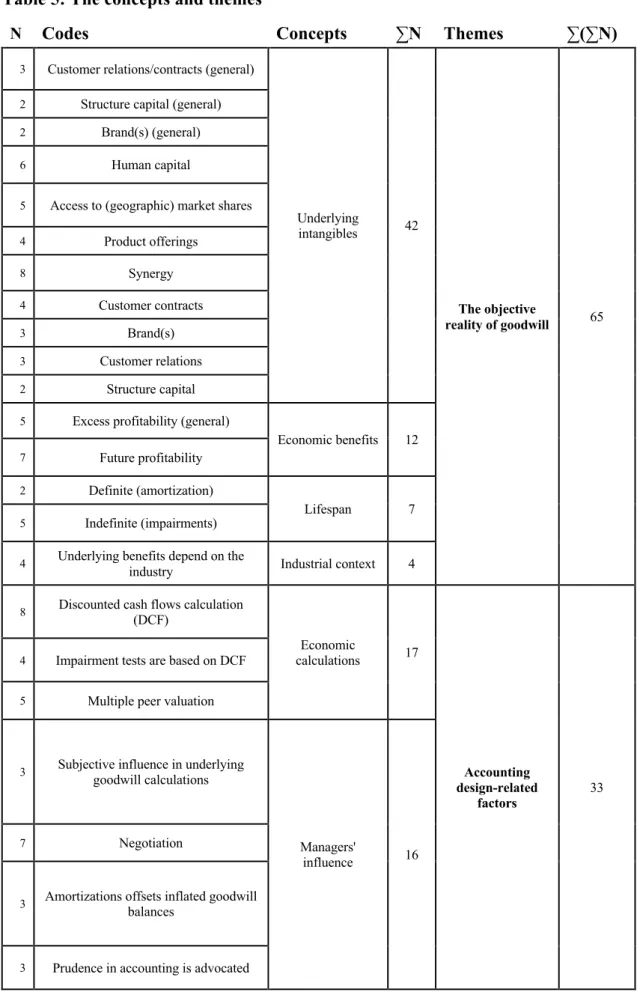

5.1 Theme 1: The objective reality of goodwill ... 72

5.2 Theme 2: Accounting design-related factors ... 75

6. Discussion ... 77

6.1 The underlying objective reality of goodwill ... 77

6.2 The accounting design of goodwill ... 82

6.2.1 The recognition aspect of the accounting item goodwill ... 82

6.2.2 The subsequential measurement aspect of the accounting item goodwill ... 87

6.3 The holistic understanding of the accounting item goodwill ... 90

7. Conclusion ... 94

7.1 The findings of this study ... 94

7.2 Contributions of this study ... 95

7.3 Limitations of this study ... 97

7.4 Suggestions for future research ... 98

References ... 99 Tables ... 107 Table 1 ... 107 Table 2 ... 107 Table 3 ... 107 Table 4 ... 108 Table 5 ... 109 Figures ... 110

Figure 1 ... 110 Figure 2 ... 111 Appendices ... 112 Appendix 1 ... 112 Appendix 2 ... 113 Appendix 3 ... 114

1

Introduction

This chapter introduces the reader to the accounting item goodwill by first presenting a general background that presents its complexity. This is then followed by a problematization that motivates why there is a need to bring clarity to the accounting

item goodwill.

1.1 Background

Financial accounting is a highly detailed, thorough and meticulously formulated reporting system that provides guidelines for how business entities shall disclose financial information (IASB, 2018a). This system achieved international harmonization in the early 2000s which ultimately enabled official comparisons of entities’ financial information (IASB, 2018a; IASB, 2018b; Wagenhofer, 2009). One can therefore proclaim that financial accounting today resembles a global language. The purpose of this language is to achieve standardization of relevant and faithful narrations of entities’ financial events (IASB, 2018a). This is achieved through the application of a regulatory dictionary that centers around final narrative forms of concepts attached to numbers, called line items of financial statements (IASB, 2001). Inventory, accounts receivables and PPE are all examples of such concepts, where their attached values are obtained through systematic calculations (IASB, 2001). In the end, thanks to this reporting language’s regulatory legitimacy can these items be considered reliable and therefore effectively act as a foundation for decisions made by entities’ different stakeholders (IASB, 2018a). However, among the many and well-established line items within the accounting dictionary exists one item whose narration has always been complex – goodwill (Wen & Moehrle, 2016).

Goodwill in financial accounting acts as the official concept for benefits obtained during the creation of a business combination and has done so for a very long time (e.g.,

Dicksee, 1897; Leake, 1914). Its current international definition is “An asset representing the future economic benefits arising from other assets acquired in a business combination that are not individually identified and separately recognized”

(IASB, 2008, p. A210). Put in other words, goodwill is therefore any value of a

company that is assumed to exist but not narrated by any other financial statement item and recognized only during the transfer of ownership to another entity (Courtis, 1983; IASB, 2008; FASB, 2014). Goodwill therefore practically acts as the accounting language’s narration of a residual difference between the price paid for obtaining the ownership of another entity and the value of the entity’s other identifiable line items (Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994). Goodwill is therefore strongly linked to corporate ownership transactions.

As the world has experienced a continuously growing global economy since the post-war era, businesses have grown into sizes larger than ever before (e.g., Davis, 1992; Wen & Moehrle, 2016). Entailed to this growth, corporations have increased in their merger and acquisition activities (Wen & Moehrle, 2016). Since the 70s has this implied an almost proportional growth rate of goodwill values on balance sheets, seeing a

compound annual growth rate of almost 18% in the US (Davis, 1992; Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994). This means that in recent years has goodwill become a substantial line item on financial statements, as sometimes up to 50% of the price paid in corporate ownership transactions has seen its allocation to goodwill (Boennen & Glaum, 2014). Goodwill has therefore seen a substantial increase in its relative weight against other items within the accounting dictionary. Consequently, goodwill has become a hotter topic among academics in more recent years, having induced debates around its different underlying aspects (Wen & Moehrle, 2016).

When looking deeper into the international dictionary, one of the first notable issues is that goodwill is only allowed to appear as an item on balance sheets in sequence to a business combination (IASB, 2008; IASB, 2004a). Consequentially, this implies that goodwill is not considered an asset if internally generated (IASB, 2004b). This perspective on goodwill can be referred to as the recognition issue of goodwill in accounting and is one of the less discordant research topics on goodwill (e.g., Malmqvist, 2017). Opponents to this view argue however that as the two essential characteristics when recognizing intangible assets are possession and severability (IASB, 2004b), it can be questioned whether if goodwill really meets these

As a response, others have instead proposed that any asset should primarily be

perceived as an economic quantum with potential future benefits possessed by an entity (Paton, 1968; Gynther, 1969). Hence, regardless of its shape, measurability and

severability, goodwill does not contradict the fact that it might consist of important values for a firm and thus, deserves to be reflected in the financial statements (Paton, 1968; Gynther, 1969).

Whereas the recognition issue experiences more unity of opinions, the second issue of how to continuously measure goodwill does not (e.g., Falk & Gordon, 1977; Jennings et al, 1996; Drefeldt, 2009; Wen & Moehrle, 2016). The debate has a long history and centers around mainly whether goodwill should be amortized or impaired (Wen & Moehrle, 2016). Before the current IASB standard IAS 36 Impairment of assets took shape, amortization dominated the subsequential measurement aspect of goodwill (Wen & Moehrle, 2016; Jennings et al, 1996; Jennings et al, 2001; Ayres et al, 2019). The change from amortization to the current impairment method occurred after a discussion of what approach is best at capturing fluctuating goodwill values, mainly based on assessments of whether goodwill has a definite or indefinite lifespan (Gynther, 1969; Davis, 1992; Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994; Jennings et al, 1996; Choi et al, 2000).

Eventually reaching consensus, annual impairment tests ended up being perceived as the more convincing method for the task (Jennings et al, 2001; IASB, 2004a). However, since 2014 has the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) been discussing whether to re-introduce amortizations again, indicating towards absolute unanimity in opinions is yet to be reached (FASB, 2014; Wen & Moehrle, 2016).

Whether the discussion is how to continuously measure goodwill or when it should be allowed recognition into a balance sheet, goodwill remains still yet another concept in the language of accounting whose connotation has an attachment to an underlying objective reality. Consider the concept of real estate, it is instantly clear what this refers to as it has the physical evidence of a building that proves its existence. But for

goodwill, the connotation for this concept does not share the same privilege as it lacks any physical evidence to prove its existence (IASB, 2004b). Thereby lies the issue concerning what the goodwill item fundamentally refers to as its underlying objective reality. Nevertheless, the item has its claim in the accounting dictionary and therefore

officially generates narration of something that is unclear. The question of what the goodwill item actually seeks to narrate has attracted academic curiosity for a very long time (Canning, 1929; Gynther, 1969; Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994; Drefeldt, 2009; Malmqvist, 2016; Nilsson, 2017; Malmqvist, 2017). One belief has been that goodwill represents a compilation of several underlying components such as brand names, customer loyalty, special skills and knowledge, management’s competence, good name and reputation, established clientele, favorable situation among else (Chauvin &

Hirschey, 1994; Davis, 1992; Falk & Gordon, 1977; Nelson, 1953; Duvall et al, 1992; Tearney, 1973; Gynther, 1969). Still, goodwill has not yet managed to be elaborated in this spectrum, as its definition lingers on an elusive interpretation of goodwill only being benefits from other unrecognized assets (IASB, 2008).

The accounting item goodwill is therefore currently one of the more complex items within the accounting dictionary. It demands not only from its audience an

understanding of what impairments are and how a business combination is

accomplished but also imagination of what the concept of goodwill is fundamentally referring to. Had goodwill only possessed an insignificant claim on balance sheets would these demands seem neglectable. But as goodwill has only kept establishing itself in the exact opposite direction of being a marginal item on balance sheets, these

demands can only be stated to have seen a proportional increase in their importance (Boennen & Glaum, 2014). It is therefore to this background it becomes apparent, that the current state of the accounting item goodwill can be questioned.

1.2 Research problem

Among the many different concepts within the accounting language’s dictionary can goodwill be perceived as one of the most complex in terms of what is required by a user to fully understand it. And as the accounting language’s ultimate narrative form is the line items of financial statements, the question becomes therefore what perception is actually to be made from the final designation of the accounting item goodwill? What does an entity that includes goodwill in their balance sheet seek to disclose with the word goodwill and its attached value? What information is sought to be communicated to the entity’s stakeholders through this item? In its current state in financial statements, the accounting item goodwill cannot be stated to have a clear answer to these questions. Instead, the status quo of goodwill in the language of accounting rather nurtures

different problems for its audience that ultimately overwhelms its relevance as an accounting item.

As line items of financial statements consist of two components – a concept and an attached value – it can be perceived as namely two central messages are sent by each individual item. Considering the concept in the line item goodwill, the early premise is that it represents an economic asset for an entity and deserves thus a position on the balance sheet (IASB, 2001; IASB, 2004a; IASB, 2008). But what this concept suggests being its underlying objective reality that generates economic benefits has long been addressed by researchers to be highly difficult to define (e.g., Sands, 1963; Chambers, 1966). For example, in comparison to the concept “real estate”, it is instantly clear that a building of some sort is referred to as the general underlying objective reality. But for goodwill, there exists no such clear connotation for its underlying objective reality correspondingly. Therefore, when a user of financial statements is presented with the concept of goodwill, he or she would find it difficult to assess what the entity

specifically intends to say with the concept of goodwill. The user could seek further information in the attached notes, as these aim to bring further explanation required to gain an understanding of the financial statement’s line items (IASB, 2001). But even here might the information be limited for goodwill, as prior studies have found that most notes attached to goodwill are more bland than contributive (e.g., Rahm et al, 2016). The concept of goodwill is therefore a big question mark regarding what its

underlying objective reality is, and this issue only further limits what understanding can be made from the second aspect of the goodwill item – its attached value.

Values attached to the goodwill concept are currently regulated by the accounting processes of recognition during business combinations and subsequential measurement through impairments (IASB, 2004a; IASB, 2008). However, when the underlying objective reality of goodwill per se is unclear, how can these accounting processes be certain on what value to capture and consequentially display? Consider the impairment method for goodwill where the impairment tests rely on managers’ continuous future estimations of goodwill’s economic benefits (IASB, 2004a). But as goodwill’s underlying reality is not objectively definable, it consequentially entails an inherent uncertainty in these assessments (Li & Sloan, 2017). Research has therefore argued that this uncertainty might result in impairment tests becoming subject for opportunistic behavior, ultimately making values of the accounting item goodwill less reliable (Sands, 1963; Chambers, 1966; Boennen & Glaum, 2014; Li & Sloan, 2017; Glaum et al, 2018; Ayres et al, 2019). Consequentially, this is believed to contribute to information

asymmetry between the managers and the users of financial statements; something that is believed to only keep increasing the higher the share of goodwill in balance sheets gets (Boennen & Glaum, 2014; Davis, 1992; Rahm et al, 2016; Muller et al, 2009). The question becomes therefore what reasonable understanding is to be made from the value displayed in the accounting item goodwill.

The ultimate question becomes therefore how the accounting item goodwill is currently perceived by the users of financial statements. Initially, has research found that

investors incorporate goodwill information in their decision processes, hence perceiving information related to goodwill as meaningful (e.g., Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994;

Jennings et al, 1996; Li et al, 2011; Knauer & Wöhrmann, 2016). But at the same time has it been found that investors might not be able to completely comprehend the meaning of the goodwill item (Duvall et al, 1992) and that they perceive it as less important relative to other items on the balance sheet (Choi et al, 2000). Further, Li and Sloan (2017) found that investors were not able to anticipate the timeliness of

impairment tests. This is coherent with the findings of Bens et al (2011) who found that markets reacted significantly to unexpected goodwill impairments. Hence, the

impairments were not anticipated and therefore not reflected in the stock price, indicating that the market couldn’t access or comprehend the information. Therefore, findings on the current relevance of goodwill as perceived by investors indicate that the goodwill item is not completely understood. This can be due to many other reasons than just the unclarity of the item, however. For example, investors might naturally be more interested in other financial metrics than the values of goodwill. However, the

implication that the goodwill item might not be perceived as relevant or completely understood by investors remains.

Goodwill can therefore be stated to be an unclear and bland line item that ultimately results in it having a lower perceived relevance in financial statements. Whether this outcome is due to its inherent complexity or simply not including valuable information enough for its users, it is still questionable why it is not better understood, considering its substantial claim on balance sheets (Boennen & Glaum, 2014). However, where the problem of the accounting item goodwill’s low relevance becomes most obvious is in consideration to the very purpose of its existence.

The purpose of the language of accounting through its meticulously and thoroughly designed dictionary is to ultimately generate faithful and relevant information about reporting entities’ financial positions (IASB, 2018a). The financial statements represent this reporting language’s definitive shape which means that the inherent line items act as the final narrations for achieving this purpose (IASB, 2001). The legitimacy of the language of accounting relies therefore largely on these line items’ ability to generate relevant and faithful narrations about the financial position of entities. But as the line item of goodwill is currently unclear and bland rather than contributing to users of financial statements, this item can therefore be stated as failing to live up to this purpose. Goodwill, being one of the most historically discussed and problematic concepts in accounting (Wen & Moehrle, 2016), represents therefore an ultimate shortcoming of the accounting language. The purpose of this study is therefore to respond to this failure, by bringing clarity to the accounting item goodwill and hopefully contribute to an increase in its current relevance.

The question becomes therefore how this unclarity of the accounting item goodwill can be treated for the ultimate improvement of its relevance. As goodwill is one of the most historically covered topics within accounting research, this question has been asked in a wide collection of previous research (e.g., Dicksee, 1897; Canning, 1929; Falk & Gordon, 1977; Gynter, 1969; Drefeldt, 2009). The academic debates have still managed to constantly remain in discordance, as debates of goodwill’s inherent issues continue to generate little to no outcomes (e.g., Drefeldt, 2009; Nilsson, 2017; Wen & Moehrle, 2016; Jennings et al, 2001; FASB, 2014). Thus, due to the current state of goodwill in accounting, prior research has yet not succeeded in generating substantial clarity. This signals that goodwill is indeed a complex phenomenon, but it also raises the question of why prior research has not been more contributive?

One reason could be that prior goodwill studies have mostly focused on the different aspects that constitute the complete item goodwill. For example, some studies have been particularly directed towards the subsequential measurement aspect, some towards the recognition aspect and others on the asset definition of goodwill (e.g., Jennings et al, 2001; Falk & Gordon, 1977, Davis 1992; Bradley et al, 1988). Hence, these studies’ concentration on elaborating specific issues related to the complete item goodwill might have omitted understandings of a holistic perspective of goodwill. It could be argued that clarification of individual aspects of goodwill, in summary, should contribute to such a complete understanding of goodwill. But by only focusing on individual aspects, integrations between these or interrelating consequences might be overlooked. Further, due to the vast spectrum of research on individual aspects of goodwill (Wen & Moehrle, 2016; Chambers & Finger, 2011; Duvall et al, 1992; Gynther, 1969), it becomes

difficult to argue that conducting similar approaches would generate a substantial contribution to the vast research field of goodwill. As such, this study will therefore attempt to address a more complete and synthesizing understanding of the accounting item goodwill to generate a comprehensive description of its current narration and thus, potentially contribute to an increased relevance.

Another potential reason behind the lack of debate-changing results might be due to the type of research methods applied by earlier goodwill studies. Most prior studies have focused on studying annual reports, share prices, press releases, balance sheets, notes or

reviewing and discussing prior literature (e.g., Bradley et al, 1988; Chauvin & Hirschey, 1993; Choi et al, 2000; Davis, 1992; Duvall et al, 1992; Glaum et al, 2018; Gynther, 1969; Henning et al, 2000; Miller, 1973; Tearney, 1973). What this means is that there has been an overemphasis on archival and secondary data, meaning that limited

perceptions of goodwill have mostly been studied and thus might have prevented a full understanding of its complexity. Hence, one reason behind the lack of effective results could be a methodological research gap. Therefore, in opposite interpretation, if one would instead approach goodwill empirically directly through the eyes of the ones involved in its practical unfolding, a new perspective might be obtained.

One approach would be to study goodwill during its creation process through business combinations. Consider the corporate acquisition phenomena. It is reasonable to assume that an acquirer who is purchasing goodwill intuitively might be among those that possess the most knowledge about how goodwill is measured and what it represents. Auditors, the selling company or participating corporations in a merger would also be potential groups with similar substance of knowledge about goodwill in practice. However, due to the clear transaction event of a corporate acquisition, this study will focus on acquirers. Therefore, to act on this methodological research gap, this study will investigate goodwill from the perspective of the acquirer which might bring a new nuance to the current understanding of the line item goodwill.

In summary, it becomes clear that the current unclarity of the accounting item goodwill is an issue that needs to be addressed, as its current state fails to live up to the very purpose of accounting. In a new attempt to try and bring clarity to the goodwill item and increase its relevance, this study will attempt to approach goodwill through a holistic synthesizing perspective of its current state. Further, by doing so through empirical firsthand observations of the acquirers’ perceptions about goodwill, we hope to generate findings that might bring new perspectives for an otherwise well-known historically established concept. The purpose of this study is therefore to generate an increased understanding of what the accounting item goodwill means by bringing new perspectives into its current conceptualization. Any findings can act as a direct interpretation between the intended narration by the preparers and the resulting perception of the users. As such, clarity of the item goodwill might be achieved and

therefore ultimately contribute to an increase in its relevance as perceived by the users of financial statements. Further, by clarifying the line item goodwill, this study might hopefully introduce a path of enlightenment for today’s standard setters that in the end might generate a change in the current usage and application of goodwill. In the hopes of ultimately generating clarity to the meaning of the accounting item goodwill, it could imply that future methods of measuring and interpreting goodwill might become more accurate and representative of its actual meaning as an asset.

1.3 Research question

Based on the acquirers’ perceptions, what is the meaning of the accounting item goodwill?

1.4 Purpose

The purpose of this study is to clarify the financial statement line item goodwill by generating a holistic understanding. This will be approached by examining what the concept of goodwill and its attached value really mean. By bringing an increased understanding of the accounting item goodwill, it could help increase its current

perceived relevance among users of financial statements. An increased relevance would also help contribute to the purpose of accounting by generating relevant and faithful information to entities’ stakeholders. Lastly, as the topic of goodwill is one of the most historical and complex issues in accounting research, a clarification of its current state in balance sheets might provide guidelines for future research in the pursuit of

ultimately improving the accounting of goodwill.

1.5 Delimitations

This study aims to bring clarity to the financial statement line item goodwill. This means that the study assumes foremost goodwill from the perspective of the definitions obtained by its current accounting standards. Specifically, these resemble the global dictionary of goodwill as assumed provided by IASB. As such, this study does not look at goodwill from a general business perspective but from the assumptions defined by the language of accounting. Furthermore, this study intends to examine goodwill through its

recognition from the business combinations phenomena, where the perception of acquirers has been stated as the main empirical focus. This means that this study assumes foremost corporate acquisitions as the main method for generating business combinations, meaning that mergers and other methods to obtain a business

combination are not highlighted in this study.

1.6 Key concepts

Accounting dictionary = in this study, a parable for the regulatory accounting

standards in financial accounting. For goodwill, the accounting dictionary is assumed to be the IASB standards of IFRS 3, IAS 36, IAS 38 and IASB conceptual framework. Accounting item = financial statement line item, consisting of a concept and an attached value of this concept’s underlying objective reality.

Amortization (intangible assets) = in financial accounting, a method of measuring an intangible asset’s subsequential value. Amortizations are systematic pre-determined deductions of an asset’s carrying amount.

Business combination = a transaction that results in one entity acquiring the control of one or several other entities. In this study, business combinations are foremost assumed implemented through corporate acquisitions.

Discounted cash flows (DCF) = in this study, the primary economic calculation that is conducted to generate the present value of future cash flows.

Fair value = the value of an asset as reflected by its market participants. Thus, the price received if the asset would be sold at a market at any current date.

Goodwill = a residual that arise during business combinations as the purchase price exceeds the sum of the acquired company’s fair value of total identifiable assets and debt.

Impairment = in financial accounting, a subsequential measurement method for assets based on continuous evaluations. An asset’s carrying value is compared against its recoverable amount. If the recoverable amount is lower than the current carrying value, then the asset’s carrying value is reduced to this level through an impairment.

Intangible asset = economic benefits owned by an entity that lacks physical substance. Manager discretion = freedom for a manager to decide what to be done in a particular situation.

Opportunism = during the economic assumption of rationality, the behavior of acting towards one’s self-interests with no consideration towards others.

Purchase price = in corporate acquisitions, the price paid to obtain control of the acquiree, resulting in a business combination.

Purchase price allocation (PPA) = during the creation of a business combination, the allocation of the purchase price across the acquiree’s identifiable assets and liabilities, conducted by the acquirer.

Recognition = a concept in financial accounting of when an item is acknowledged existence into the financial statements of an entity. For goodwill, this is only through business combinations.

Underlying objective reality = during the assumption that accounting items act as narrations of events that have occurred for an entity, the underlying objective reality is what is trying to be narrated by the concept of an accounting item. For example, the underlying objective reality of the item real estate is its building.

2

Theoretical background

The following chapter includes the authors’ collection of relevant theories and research on goodwill. This collection acts as the theoretical base for this study by providing the

main assumptions for the authors in their pursuit of an answer to their research question.

2.1 Goodwill in financial accounting

In pursuit of reaching clarification of the accounting item goodwill, it becomes convenient to start by reviewing IASB’s dictionary for the item’s current

conceptualization. For goodwill, this dictionary is assumed in this study to specifically be the IASB standards of IFRS 3, IAS 36, IAS 38 and the IASB conceptual framework (IASB, 2004a; IASB, 2004b; IASB, 2008; IASB, 2018a). Hence, the following section includes an overview of these standards’ comprised conceptualization of goodwill which will act as a main guide towards an overall understanding of the concept.

Goodwill is an intangible asset. An asset is a resource in control of the entity as a result of past events that is expected to generate economic benefits for the entity (IASB, 2018a). Intangible is anything identifiable of non-monetary or non-physical substance (IASB, 2004b). The category of intangible assets means therefore a very broad

classification, including copyrights, patents and licenses among others in its scope (IASB, 2004b). Initially, the broad category therefore opens the possibility of recognizing almost any cost as an intangible asset. Thus, IASB (2004b) has a strict criterion for when certain costs are recognized as intangible assets, emphasizing restrictions for internally generated intangible assets. For goodwill, the only way of becoming recognized is through business combinations (IASB, 2008). This makes goodwill therefore unique as an intangible asset, being per definition not directly identifiable other than as a cost in relation to a corporate transaction of ownership.

Accounting items are ultimately depicted on financial statements and achieve this form through a process called recognition (IASB, 2018a). For goodwill, this is through business combinations (IASB, 2004b). The motive behind only allowing recognition of

goodwill in relation to a business combination is because it ensures that goodwill originates from a contractual event (IASB 2004b). The major problem expressed with goodwill is that it is not separately identifiable when internally generated and cannot therefore be proved to be generating future economic benefits for an entity (IASB, 2004b). In a corporate acquisition however, this problem gets avoided as goodwill can be recognized through the purchase price (IASB 2004a). The reasoning being that acquisitions are investments that include expectations of future returns as well as goodwill becoming identified as an obtained residual (IASB 2004a). Historically has recognition through business combinations always been perceived as the only legitimate way to recognize goodwill in balance sheets (e.g., Canning, 1929; Falk & Gordon, 1977).

Once recognized, an asset in financial statements is faced with the task of seeing its value measured over time (IASB, 2018a). For goodwill, this is a topic that has seen a large debate between mainly the amortization and impairment methods (Wen & Moehrle, 2016). Before IASB established the impairment method for subsequential measurement of goodwill, nations adopted different accounting standards which implied slight differences (Gynther, 1969; Davis, 1992). Although impairments currently act as the generally assumed method, some countries still apply the amortization method, for example the Swedish GAAP K3 (BFNAR 2012:1). The debate of which method is best at measuring goodwill’s value over time has centered around the issue of deriving a lifespan for goodwill (Ladd, 1963; Jennings et al, 1996). The current impairment method implies the adoption of an indefinite view on goodwill’s lifespan, where amortizations assume a definite period (Davis, 1992; Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994; Jennings et al, 2001).

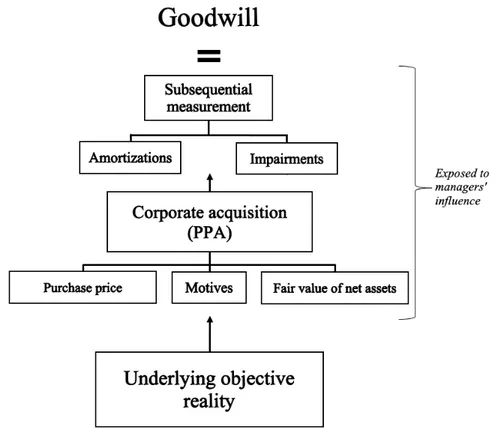

With this brief overview of the IASB dictionary on the accounting item goodwill, it becomes clear that the item is constituted by three central aspects. First, goodwill is to be perceived as an intangible asset that generates future economic benefits and is controlled by an entity. But what these benefits are is not explained more than as being benefits that are not included in the other identifiable assets of an entity (IASB, 2008). Thus, the second aspect is that this intangible asset can only be recognized in relation to a transfer of corporate ownership, meaning that business combinations is central for

understanding goodwill. Lastly, the value of goodwill over time is currently decided through continuous impairments, where a main estimation in these assessments relies on an assumed lifespan of goodwill. All these three aspects can therefore be perceived as separate underlying aspects of the accounting item goodwill that together constitutes its holistic meaning. The subsequent sections for this study’s theoretical background will therefore assume these three aspects as main guideline for the pursuit of generating a complete understanding of the accounting item goodwill.

2.2 Theories on the underlying objective reality of goodwill

The concept of goodwill is just as any other concept of an accounting item a word that aims to explain a past financial event that an entity has experienced (IASB, 2018a). This financial event has occurred in the reality of an entity’s day-to-day activities, whereas an accounting concept aims to achieve narration of this reality. For the concept of goodwill is this reality currently explained to be future economic benefits generated by other unidentified assets (IASB, 2008). However, there exists a wide base of literature that suggests that this current definition of the concept of goodwill can be perceived as questionable (Wen & Moehrle, 2016). The following paragraphs will therefore present and discuss the most established theories on the understanding of goodwill’s underlying reality to gain a better understanding of the accounting item goodwill.

2.2.1 The master view

Starting with the master view on goodwill. This view represents one of the currently most unified apprehensions of goodwill. The view states that goodwill is a residual that arise during business combinations due to a difference between the purchase price and the fair value of the net assets of the acquired entity (Canning, 1929; Miller, 1973; Falk & Gordon, 1977; Duvall et al, 1992; Choi et al, 2000; IASB, 2008; Drefeldt, 2009). Being also one of the earlier views, it yet remains the main belief behind the current accounting process of how goodwill is recognized into financial statements (IASB, 2008). This view is argued however to merely be a financial calculation of business combinations rather than an actual description of what benefits goodwill represents as an asset (Falk & Gordon, 1977; Drefeldt, 2009); the view can be interpreted as telling little to nothing about what the residual of a business combination represents.

Regardless, the existence of this residual might still indicate towards the idea that underlying economic assets might exist underneath but have not yet been recognized ex-ante the business combination (Falk & Gordon, 1977).

Thus, the master view can be perceived as mostly justifying the current view on the recognition issue of goodwill, as it states that the reality of goodwill is no more than a mere excess outcome from a technical business combination process. This theory therefore becomes difficult to completely deny, as it acts more as a statement of a procedure that occurs during corporate ownership transactions. Where other theories stand out however in the task of addressing goodwill’s underlying reality is by further explaining what this residual of the master view might represent.

2.2.2 The economic view

A theory that has contributed a lot to the goodwill concept’s more practical debate is the economic view. This view has dominated most discussions on the issue of goodwill’s subsequential measurement that took place during the 90s (e.g., Duvall et al, 1992; Jennings et al, 1996). Building on the master view’s residual proposition, the economic view argues that this residual is representing excess earnings power of the acquired entity (Duvall et al, 1992; Colley & Volkan, 1988). Excess earnings power is explained as the abnormal returns generated by the assets of the business, both present and absent from the balance sheet ex-ante the acquisition (Colley & Volkan, 1988). Goodwill is the result of a calculation of the future excess earnings discounted at a normal rate of return over an estimated period, net from its operating costs (Colley & Volkan, 1988; Jennings et al, 1996). Goodwill becomes therefore the recognition of future cash flows in the acquirer’s balance sheet, discounted over the assumed lifespan of the goodwill.

There have been debates regarding the lifespan of these future cash flows, which to some extent explains why there has never been absolute agreement regarding

amortizations or impairments for goodwill evaluation (Wen & Moehrle, 2016). If the excess earnings are believed to eventually stop, then goodwill’s lifespan is definite and should therefore be amortized over this period (Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994). If the excess earnings are not perceived as definite however, then the lifespan is to be

et al, 1996). However, like the master view, the economic view of excess earnings has been criticized to only be an elaborated economic calculation of goodwill as a residual, as there have never been clear explanations of what it is that is generating the alleged excess earnings (Gynther, 1969; Drefeldt, 2009). Because regardless of any discounted future cash flows that the residual represents, these cash flows depend on something that generates them. It exists therefore other theories that try to respond to this shortcoming of the two thus far covered theories.

2.2.3 The hidden assets view

Being the oldest and most discussed view on goodwill in research, the hidden assets view has gained many followers over the last century (Dicksee, 1897; Falk & Gordon, 1977; Davis, 1992; Lys et al, 2019; Wen & Moehrle, 2016; Nilsson, 2017). Since the very first attempts at explaining what underlying benefits goodwill refers to, theorists have suggested that goodwill represents a sum of unrecognized intangible assets. Examples are brand, customer and supplier loyalty, patents, copyrights and the going value of the firm (Canning, 1929; Gynther, 1969; Tearney, 1973; Miller, 1973; Johnson & Petrone, 1998). These are considered hidden because despite having confirmed existence, they are not considered separately identifiable assets according to accounting standards and thus not recognized on financial statements (IASB, 2004b). Instead, they are believed to be hidden in balance sheets behind the accounting item goodwill.

There exist different specific perceptions within the hidden asset view regarding what type of assets are most likely to hide behind goodwill as underlying components. Some have exemplified specific components as more potential than others to stimulate engagement of discussions for new views on goodwill (e.g., Colley & Volkan, 1988; Rahm et al, 2016). Others have studied components directly in connection to the discussion of which of the methods of amortizations or impairments is best at continuously measuring goodwill (Nelson, 1953; Falk & Gordon, 1977; Johnson & Petrone, 1998; Henning et al, 2000). In the normative discussion on goodwill however has the motivation behind hidden assets studies been a belief that by decomposing goodwill into identifiable components, in an omniscience scenario – if everything would be measurable and identifiable – it would result in goodwill not needing to exist on balance sheets as its value would instead be distributed over all its underlying

components (Gynther, 1969; Tearney, 1973; Miller, 1973; Davis, 1992; Drefeldt, 2009). The lack of any change in this direction among standard setters perhaps signals a lack of empirical evidence or theoretical disagreement. Nonetheless, it remains a vast field of study that has produced several different examples of potential components. Many articles have brought their own unique presentations and categorizations of goodwill components (e.g., Johnson & Petrone, 1998). This has led to the literature becoming both dispersed and repeating of some assets at large. Thus, we found it to be of

relevance to synthesize all goodwill components mentioned within top research articles to facilitate the understanding of the hidden assets view.

2.2.3.1 Literature review on the hidden assets view

Our review began by reading the most dominant and contributing literature addressing the issue of goodwill’s substance as an asset. The selection of these articles was based on the number of citations, the rank of the journals and if the papers had been quoted by sooner articles. This criterion resulted in us reviewing a total of 24 top articles on goodwill, covering almost 120 years of research. Out of these papers, 12 either

specifically mentioned or directly studied underlying goodwill components. From these 12 articles could 84 explicit mentions goodwill components (n) be observed of which were documented and structured in Excel. One mention is defined as one observation of a component. We then analyzed for commonalities among the articles’ total mentioned components, leading us into creating five different component categories as presented in Table 1. These categories were identified based on the main assumption of goodwill being recognized in relation to a corporate acquisition. This means that the categories represent different categories of beneficial aspects that the acquirer has obtained because of the business combination.

Table 1: Categorization of different hidden components of goodwill

Hidden component categories % of n % of authors mentioning (n = 12)

Unrecognized intangible assets 45% 83%

Economic enhancing 24% 67% Human capital 14% 50% Synergy related 8% 42% Acquisition process-related 6% 17% n = 84

2.2.3.1.1 Unrecognized intangible assets

The commonality of the components in this category is that the components refer to an acquirer’s access to any asset that is previously unrecognized and intangible. Examples being R&D projects, brand value, contractual intangibles such as patents or licenses or customer lists, access to market shares, customer relations and technology. This category was inarguably the most dominant among the literature where contractual intangibles were the most mentioned to be composing goodwill (Falk & Gordon, 1977; Gynther, 1969; Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994; Johnson & Petrone, 1998; Nelson, 1953; Tearney, 1973; Davis, 1992; Bradley et al, 1988; Ladd, 1963; Dicksee, 1897).

2.2.3.1.2 Economic enhancing

This category intervenes with the economic view on goodwill. It consists of components that exclusively represent direct economic beneficial outcomes for the acquirer due to the business combination. These components relate to either production, sales or

financing benefits. Examples of mentioned components are access to economies of scale benefits, increased credit ratings, tax benefits, excess earnings power and supply

assurance to name a few (Falk & Gordon, 1977; Gynther, 1969; Johnson & Petrone, 1998; Henning et al, 2000; Rahm et al, 2016; Nelson, 1953; Bradley et al, 1988). Compared to the other four identified categories, the economic enhancing components signify themselves due to their direct relationship to economic or financial benefits. The other categories achieve these outcomes rather indirectly by generating potential for enhanced competitive ability that ultimately may result in economic benefits.

2.2.3.1.3 Human capital

As many intangible assets were included into the unrecognized intangible assets category, one intangible component was saliently separatable out of these. Human capital represents the compilation of components that refers to the skills and knowledge of the workforce or management of the acquired entity. (Falk & Gordon, 1977; Gynther, 1969; Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994; Tearney, 1973; Davis, 1992; Bradley et al, 1988). Thus, the human capital components belong to the intangible asset category but remain not subject to legal ownership of the entity and therefore separates itself into its own category. By some, it could be argued that human capital is therefore not able to be an asset and never appear on financial statements, although nonetheless an obvious aspect in business prosperity.

2.2.3.1.4 Synergy

Synergy refers to when the interaction and collaboration of assets generate outcomes greater than their sum (e.g., Johnson & Petrone, 1998; Lys et al, 2019). In practice has synergy been widely used by corporations during disclosure of goodwill in annual reports (Rahm et al, 2016; Malmqvist, 2017). It could therefore be argued that synergy deserves to rather be described as its own theory on the objective reality of goodwill. However, more than rarely is synergy making appearances as an independent

component together with other hidden asset components (Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994; Johnson & Petrone, 1998; Henning et al, 2000; Tearney, 1973; Bradley et al, 1988). Therefore, we found it more accurate for this study to include synergy as its own category of a goodwill component.

Apart from synergy being explicitly expressed in some studies, some also mentioned other benefits such as integration, beneficial spillover effects of recognized intangible assets, product diversification and resource combinations (e.g., Bradley et al, 1988). We chose to interpret these concepts as components of synergy as they are likely to be either alternate descriptions or results from synergy. The reasoning was that these concepts all refer to obtained benefits that are dependent on the business combination and therefore related to the concept of synergy.

2.2.3.1.5 Acquisition process-related

As the least prominent category of components in goodwill literature, acquisition process-related components are nonetheless highly apparent in practice and in particular merger and acquisition literature (e.g., Bradley et al, 1988; Johnson & Petrone, 1998). These components are isolated to the acquisition event and are therefore not primarily considered assets. Still, due to the current accounting of recognition, they might be included in the accounting item goodwill (IASB, 2008). The concepts observed were overvaluations of purchase prices and write up surpluses of assets to fair value (Johnson & Petrone, 1998; Henning et al, 2000). These components therefore represent values that are independently attached to the technical process of corporate acquisitions (Henning et al, 2000).

Table 1 therefore is a synthesis of the hidden assets view’s central arguments in more detail. The theory stands not without criticism, however. The main critique towards the hidden assets view are questions regarding the identification and measurement of the alleged hidden assets (Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994). This critique can also be found in the motivation of the IAS 38 principles on the strict recognition criteria of internally generated intangibles (IASB, 2004b). The problem is expressed as these hidden assets – brand, brand names, customer relations or market positions as mentioned examples – are too difficult to objectively identify and measure and therefore being too subjective for inclusion into financial statements (Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994). Thus, considering the historical significance of the suggested hidden assets view, it still has not convinced standard setters to disseminate the accounting item goodwill, nor practitioners in advancing in development of objective measurement and identification procedures of such assets.

It can be interpreted that the hidden-asset view is one of the more substantial theories that try to approach the question of what goodwill is referring to from its core existence. In relation to economic view and master view, the hidden-asset view can be interpreted as trying to go one step further in understanding goodwill’s underlying objective reality. Due to focus on unrecognized intangible assets however, the theory seems to point towards that to achieve clarification of goodwill’s connotation to reality, it demands pre-understanding of other accounting concepts that on their own require clarifications –

what is a brand and how is its value derived? What can therefore be perceived as an attempt to strike a middle ground between the hidden asset view and economic view is momentum theory (Nelson, 1953; Falk & Gordon, 1977).

2.2.4 Momentum theory

In the 50s, momentum theory was presented as a new approach in the debate on the underlying objective reality of goodwill (Falk & Gordon, 1977). The original author, Nelson (1953), based his theory on the economic view and hidden assets view (Falk & Gordon, 1977). Momentum theory explains goodwill as being an initial push that is achieved from the acquisition of beneficial assets of the acquired entity. These assets, referring to many of the hidden assets view’s components, bring higher excess profits for the acquirer during the initial years following the acquisition as the entities integrate which therefore acts as an initial gain of momentum (Nelson, 1953). This momentum is therefore represented in goodwill and is believed to be reducing in value over time as the two businesses are getting more integrated into one unified group where assets are no longer as easily separated between the entities.

Thus, Nelson (1953) believed goodwill to be best described as an asset with limited lifespan due to the integration between the hidden assets that it consists of. This puts momentum theory in a middle ground between the two most established theoretically views and provided researchers with a unique approach on understanding the underlying reality of goodwill. It can be questioned however if the theory possesses substance in the theoretical debate due to a lack of reoccurring citations in more recent research (e.g., Falk & Gordon, 1977). Further, one could argue that the theory only acts as a more complicated way to describe the merger phenomena of business combinations. This is because as businesses merge, it would be easier to point out the integration’s benefits at an earlier stage but becomes more difficult over time as the two entities get more integrated into one unified business group.

2.2.5 Theory of imperfect competition

Another view with a different perspective on goodwill is the view of goodwill

representing benefits that generate imperfect competition. Initially authored by Sands (1963) and further elaborated by Falk and Gordon (1977), this theory approaches goodwill from a market-oriented perspective. An imperfect market is the opposite of a perfect market – when every resource and skill is accessible on markets, businesses would enter markets and develop in a way that would generate predictable returns, called normal returns (Sands, 1963). In contrast, an imperfect market therefore is a market where businesses can possess resources and skills exclusively which puts them at individual monopolistic positions, creating competitive abilities that enable the possibility of generating returns higher or lower than normal – called abnormal returns (Sands, 1963). Goodwill is explained as therefore representing these resources and skills that generate imperfect competition by consisting of assets such as brand, management competence, trademarks and copyrights for example that are exclusive to the firm. (Falk & Gordon, 1977).

The theory of imperfect competition can therefore to some extent be interpreted as being related to the hidden assets view. This is because the theory assumes underlying components but calls them monopolistic positions, where their value is determined based on the abnormal returns they generate (Sands, 1963). The theory of imperfect competition can in this interpretation therefore be said to resembling a theoretical bridge between the hidden assets view and economic view – describing the relationship

2.2.6 Synthesis of the theories on the underlying objective reality of goodwill

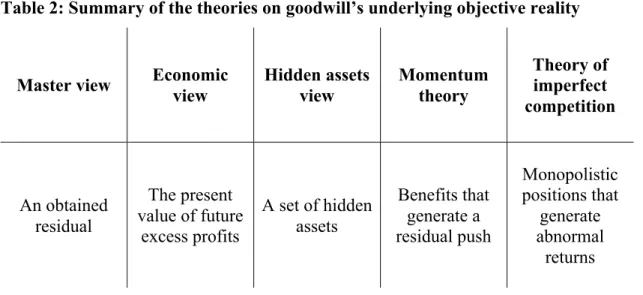

The above sections have compiled five of the most established theoretical views that address the question of what the concept of the accounting item goodwill refers to as its underlying objective reality. To facilitate an understanding of these theories, their central messages have been summarized in Table 2. The following section includes a discussion of what these theories together might imply for an understanding of goodwill’s underlying objective reality.

Table 2: Summary of the theories on goodwill’s underlying objective reality

Master view Economic view Hidden assets view Momentum theory Theory of imperfect competition An obtained residual The present value of future excess profits A set of hidden assets Benefits that generate a residual push Monopolistic positions that generate abnormal returns

Table 2 presents the five theories’ suggested descriptions of the underlying reality attached to the concept of goodwill. In an initial comparison, it can be derived that all theories except the hidden assets view explain goodwill’s reality as fundamentally referring to benefits of economic nature. This is because the concepts of residual, discounted cash flows, momentum and abnormal returns are all financially oriented (e.g., Nelson, 1953; Sands, 1963; Miller, 1973; Duvall et al, 1992). The hidden assets view is indeed mentioning economic value for potential underlying components of goodwill, but it does not emphasize that these component’s derived economic benefits are decisive for explaining the underlying objective reality of goodwill (e.g., Davis, 1992; Tearney, 1973; Gynther, 1969). For example, a brand is alleged to possibly be constituting goodwill regardless of whether its exact economic benefits have been derived or not (Davis, 1992). However, when looking at the hidden assets view and the theory of imperfect competition, it can be interpreted that the two theories partly

intertwine. The theory of imperfect competition can be interpreted as elaborating on the hidden assets view’s idea of goodwill consisting of underlying components but instead

describes these as monopolistic positions that generate abnormal returns (Sands, 1963; Falk & Gordon, 1977). As such, the theory of imperfect competition might act as a bridge between the hidden assets view and the economic view by providing the connection between underlying components and future cash flows (Colley & Volkan, 1988).

Considering further the hidden assets view and its connection to the other theories, Table 1 on categories of hidden assets includes for example the categories of acquisition process-related and economic enhancing. These categories include components that are linked to economic benefits or the acquisition event, thus being very related to the master- and economic views (e.g., Johnson & Petrone, 1998; Henning et al, 2000). Further, the hidden assets view category of synergy in Table 1 could be interpreted as being related to the momentum theory. This is because the concept of momentum can itself be interpreted as just another word for synergy – benefits that are obtained due to the integration of two businesses (e.g., Nelson, 1953; Tearney, 1973; Bradley et al, 1988). This signals that even if the hidden assets view generally stands out as having a more componential view on the substance of goodwill rather than economic, it might be more related to a financially oriented perception of goodwill than it wants to believe.

In the end, the question becomes therefore how different the theories really are

concerning their description of goodwill’s underlying objective reality. It might be the case that all the five goodwill theories might not be completely mutually exclusive as they can be perceived as intertwining in some concerns which ultimately might make them less separatable. For a complete understanding of the underlying objective reality of goodwill, it might therefore mean that it’s not only one theory that provides the best answer to this issue, but rather a combination of several.

2.3 Corporate acquisitions

The second concept that constitutes goodwill in accounting according to the dictionary provided by IASB is the issue of when goodwill is acknowledged existence. This is referred to the recognition of goodwill, which according to current accounting standards is only allowed during the creation of a business combination (IASB, 2004b). There exist different types of transactions that may lead to the creation of a business

combination (IASB, 2008). Among these was specifically corporate acquisition decided to be focused on in this study to obtain a greater understanding of the accounting item goodwill (see section 1.2). Further, due to the nature of corporate acquisitions as a type of investment, it is likely that these transactions are considered major decisions by acquirers. Hence, an important part in the process of understanding goodwill might also be related to the underlying motives behind corporate acquisitions.

2.3.1 The process of a corporate acquisition

Business combination is the name of all transactions that involve a transfer of control of an entity to an acquirer, where a corporate acquisition is when one entity obtains control of another entity through a purchase (IASB, 2008). The acquiring entity becomes the parent company in the business combination (IASB, 2008). During a corporate acquisition, a purchase price allocation (PPA) process is conducted by the parent company which determines if goodwill is recognized (IASB, 2008). This process consists of allocating the purchase price across the identifiable net assets of the acquiree, where goodwill is created if the purchase price exceeds the value of the net assets (IASB, 2008). There are two more components in this process: non-controlling minority interest and previous equity that affects goodwill. However, as non-controlling interests and previous equity interests are not guaranteed to be present for every

corporate acquisition (IASB, 2008), these aspects are not as central as the purchase price and net assets valuation aspects. For simplicity, this study assumes therefore a shortened PPA process, referring solely to the allocation of the purchase price and the valuation of net assets.

2.3.2 Motives behind business combinations

Compared to other financial events and transactions performed by business entities, corporate acquisitions stand out as being one of the biggest. As an investment, acquisitions might therefore be among the most complicated and important decisions executed by the managers of a company. Therefore, it becomes interesting to examine what different motives might exist behind these big transactions as it ultimately might affect the PPA process and therefore the goodwill that is recognized.

2.3.2.1 Shareholder motives

There are several different reasons why companies may want to participate in

acquisitions. A common pattern is corporate objectives that aim to maximize firm value (e.g., Mace & Montgomery, 1962; Falk & Gordon, 1979; Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994). Mace and Montgomery (1962) observed that the main corporate objectives acting as motives behind acquisitions were related to the improvement of financial metrics, product diversification, personnel improvement, and improvement of the ability to satisfy target markets. The findings are in line with those of Falk and Gordon (1979) who showed that the most important motivations behind acquisitions were related to acquiring managerial talent, brand name and improving operating economies. In addition, Tearney (1973) showed that most motives behind acquisitions were based on acquiring human capital, product diversification, integration, and geographic expansion.

Thus, a common reason behind business combinations is the general motive to enhance the value for shareholders by ultimately maximize firm value. These motives can therefore be called shareholder motives. These refer therefore to any underlying aspects taken into consideration during the strategic decision-making process of an acquisition that are believed to generate an increased value to the acquiring company. Thus, it is directly attached to the perceived positive attributes of a target corporation that ultimately contributes to an increased value for the parent company’s shareholders.

2.3.2.2 Manager motives

In contrast to shareholder motives, literature is also suggesting that motives behind acquisitions might be related to the personal motivations of the managers of a parent company. Due to managers’ participation as executors of corporate acquisitions, several other motives may underly this participation such as improving the individual

performance of the executing managers or diversifying their employment risks (e.g., Morck et al, 1990; Amihud & Lev, 1981). Morck et al. (1990) investigated what type of acquisitions could potentially be bad for bidding shareholders but good for bidding managers. They found that in the case of acquisitions where managerial objectives had pushed for the acquisition, it tended to result in less profitable acquisitions. For

example, firms with bad managers, identified through poor firm performance, tended to participate in less fortunate acquisitions. This could be due to personal incentives to participate in more acquisitions to potentially benefit the managers’ performance (Morck et al, 1990). These findings are consistent with earlier research such as Amihud and Lev (1981) who tested whether if conglomerate mergers are driven by managerial motives. They based their reasoning on the assumption that shareholders can achieve preferred risk exposure through portfolio diversification, whereas managers cannot diversify their employment risk. They found that managerial objectives related to diversification of the unemployment risk may therefore act as a driver for acquisitions (Amihud & Lev, 1981). Hence, findings seem to suggest that managers might be inclined to diversify firm operations for self-interest motives and therefore do so regardless of any conflict between the interest of their shareholders.

2.3.2.3 Motives affecting the PPA process

Apart from underlying motives behind the decision to acquire, research has found that managers might influence the PPA process based on personal motives. Detzen and Zülch (2012) found that managers who are relatively more exposed to bonuses tend to recognize more goodwill. The underlying reason being that managers obtain an advantage over the stakeholders due to information asymmetry (Landmans, 2007). Thus, managers will be more inclined to allocate more of the purchase price to goodwill as it, compared to other intangible assets, is exposed to impairments tests and not