1

Communication of the

collaborative act

How Swedish climate councils engage in

collaboration-based sustainability

Master thesis, 15 hp

Media and Communication Studies

Sustainable communication

Spring 2020

Examiner:

Leon Barkho

Francesca Mariani

Contemporary times, characterized by global and complex challenges, call for innovative and comprehensive answers. Climate change and environmental issues are the protagonists of

institutions’ agendas, who consequently are looking for new and effective ways of replying to these challenges. Collaborations among actors coming from different sectors, belonging both to the private and the public sector, represent a strong tool to reply to today’s challenges, where centrifugal and centripetal forces need to be managed. This study highlights the importance of collaborative efforts toward sustainable development, and particularly, it aims at emphasizing the importance of the communication aspect, which is often underestimated in collaboration-based models.

To highlight the communication aspect in collaboration, three examples are analyzed: Jönköping Climate Council, Västra Götaland Climate Council and Jämtland Climate Council. Climate Councils represent a unique and effective Swedish institution that, through a joint effort between all the actors involved in a Region, put in place different activities to reach their climate goals.

Semi-structured interviews with Climate Council’s representatives unfolded different aspects behind the Climate Council phenomenon. Moreover, the critical discourse analysis of three reports issued by the institutions gives results that are compared with what emerges from the interviews. The findings of the study aim at highlighting the key role of communication within collaborations, which in the Climate Council institutions play a vital role for the Climate Council to exist.

JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY

School of Education and Communication Box 1026, SE-551 11 Jönköping, Sweden +46 (0)36 101000

Master thesis, 15 credits

Course: Sustainable communication Term: Spring 2020

ABSTRACT

Writer: Francesca Mariani

Title: Communication of the collaborative act

Subtitle: How Swedish climate councils engage in collaboration-based sustainability Language: English

Keywords: collaboration, sustainability, climate change, Climate Council, institutions, communication

Table of contents

Introduction ... 1

Background ... 2

Climate Council institution in Sweden ... 2

Jönköping climate council ... 3

Västra Götaland climate council ... 4

Jämtland climate council ... 4

Purpose ...5

Delimitation of the study ... 6

Aim and research questions ... 7

Previous research ... 8

Cross-sectoral collaboration ... 8

Public-private collaboration ... 10

Communication in cross-sectoral collaboration ... 11

Theoretical frame and concepts ... 13

Collaboration ... 13

Value creation in collaborations ... 14

Sustainability ... 16

Sustainable development goals ... 17

Framing ... 17

Accountability ... 18

Institutional communication ... 18

Method and material... 20

Interview design ... 21

Critical discourse analysis ... 22

Reliability and validity ... 23

Analysis ... 24

Data from the interviews ... 24

Data from the Critical discourse analysis ... 28

Presentation of results……….29

Summary and conclusions ... 32

Limitations………..33

References ... ………....35

Appendices……….38

Tables

Table 1 – Climate Councils in Sweden ... 5Table 2 – Cross-sectoral collaboration definitions ... 9

Table 3 – Public-private collaboration definitions………11

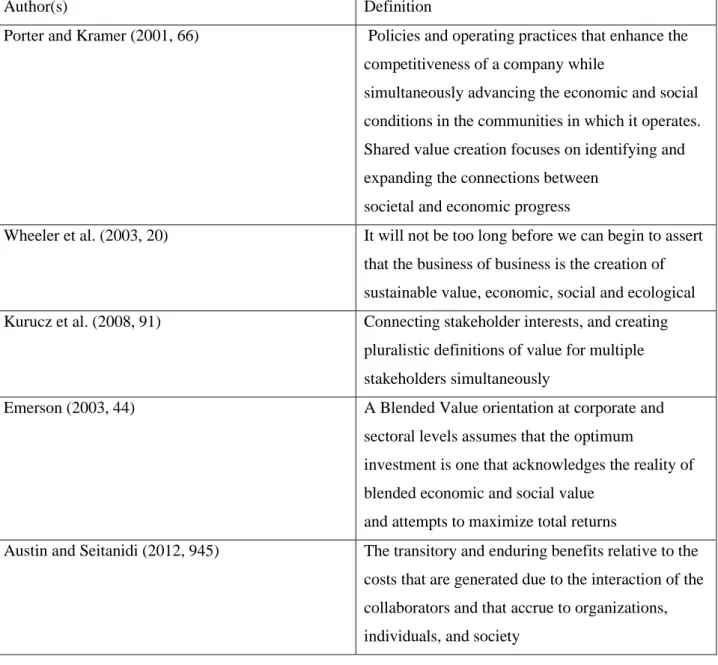

Table 4 – Value creation in collaboration ... 15

Table 5 – Interviews design ... 22

Table 5 – Interview design ... 22

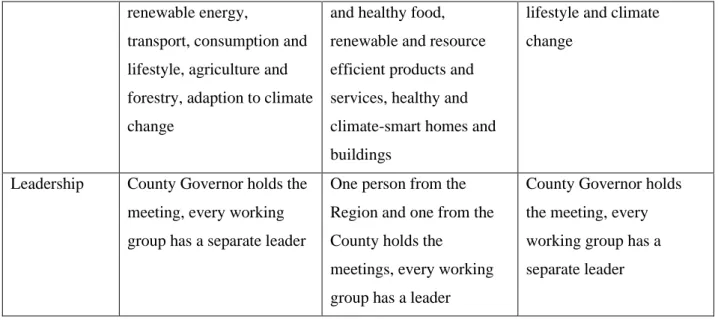

Table 6 – Comparison of collaboration structures in Climate Councils ... 29

Table 7 - Comparison of communication processes in Climate Councils ... 31

Figures

Figure 1 – Collaboration model by Bryson………..14Appendices

Appendix A – Interviews consent form……….38Appendix B – Interviews questions………....39

Appendix C – Interviews transcriptions………40

Abbreviations

CC Climate Council

PPP Public – private partnership

CSC Cross – sectoral collaboration

1 Introduction

Collaboration is a key tool when facing climate change issues because, with extended resources gained from different sectors, the outcome of the collaboration is greater than if the actors are handling the issues by themselves. Collaborations in sustainable development, between governments, organizations and industries represent a joint effort that utilizes capabilities from different sectors to achieve solutions that benefit themselves and society. Collaborative structures can develop in very different ways and seek different objectives. In this study, public-private (Bäckstrand, 2008, 74), cross-sectoral collaboration (Bryson, 2015, 647) structures are analyzed, focusing on the example of the Climate Council institution in Sweden. Swedish context opens up a new reality for collaboration efforts to happen, to work for sustainable development in the Nation and the creation of a common shared value. Climate Councils in Sweden work in the frame of

environmental issues and sustainable development, since they have the objective to get the different actors to work together towards a more sustainable developed Region. Increasing participation in sustainability-related matters has the aim to help in the reaching of wider objectives. Collaboration structures find their reasons to exist in the accountability they gain from the external environment, meaning here the knowledge and reconnaissance that the institutions hold.

Moreover, collaboration represents a complex set of ongoing communicative processes among the actors involved who act as members of both the collaboration and of the separate organizational hierarchies to which they are accountable for. Communication within the climate councils is seen as an example of wider organizational communication, in the study defined as institutional communication (Lammers, 2011, 154). Communication coming from an institution addresses its messages to both an internal and external audience. To engage with the public, trustworthiness and clarity in institutions’ internal and external messages are always to prefer. Climate Council institutions in Sweden make use of this positive outcome for good. And when there is effective collaboration, it must be backed by effective communication. Communication represents an important part of the effectiveness of collaborations, whereas good communication takes part among the actors involved but also on the outside, directed to all the different stakeholders. Communication activities span from creating a safe and clear environment within the organization to delivering the

information needed outside.

Public-private, cross-sectoral collaborations are an interdisciplinary scientific field that includes a variety of perspectives: in this case, institutional-led climate and environment policies achieved by CSPPs can

overcome issues that individual actors normally find challenging (Forsyth, 2014, 171), by creating new value, that sometimes is represented just by the collaborative act.

2 Background

During the last decade, climate change has moved from being a question of concern for the scientific community to achieving the status of a major political problem in need of urgent action (Giddens, 2009). As defined by the International Panel on Climate Change, the latter is defined as a “change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g., by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer”1. The substantial increase

in public attention around climate change and environmental threats has led to several debates about the responsibility of governments and businesses in facing these issues. Nowadays, in the context of the burgeoning effects of climate global change, networked modes of collaboration where Nations, Regions, institutions, companies, and citizens work together are imperative. Collaboration is a concept that

comprehends different meanings. Collaboration spans from helping each other in a small community to joint-ventures in business, to cross-sectoral joint-ventures on a national level. The reasons behind the establishment of successful collaborations reside in the challenges that the key players in the contemporary world have to face.

“The effort needs to help each partner organization achieve something significant. Incentives such as ‘we’ll do this for good publicity’ or ‘we do not want to be left out’ are not sufficient”. - Nigel Twose, director of the Development Impact Department, International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group (Albani, 2014, 1).

States, nations, businesses, are asked every day to do something in the direction of sustainable development, whereas the United Nations defines that sustainable development “calls for concerted efforts towards building an inclusive, sustainable and resilient future for people and planet” (UN, 2017).

This study has its focus on the Climate Council institution in the Regions of Jönköpings Län, Västra Götaland Län and Jämtland Län in Sweden. Regional Climate Councils tackle local actions and, therefore, they need the support of every part involved in the development of the Region, be they companies,

universities or citizens. Regional Climate Councils work as collaboration – based institutions, whereas regional offices work hand in hand with the companies that have their headquarters and operations in the Regions.

Climate Council institutions in Sweden

Even though regional development projects in Sweden all include sustainable development as a key issue, Regions and Counties have decided to do more in these terms, starting to put up independently the “Climate Councils”, institutions born with the aim at striving for sustainable development in all sectors, based on Regions’ strengths and weaknesses. Climate Councils arise in Regions as individual and voluntary forms of

3

collaboration between the governance institutions (Regions, Counties) and the companies that operate in the territory. Climate Councils are a new kind of institution in the Country and – as mentioned – voluntary: this means that Regions are not obliged to have a Climate Council (but most of them do, even if smaller than others). In its history of development, Sweden has always kept an eye on sustainability-related issues. On a political level, in June 2017, a broad majority in the Swedish Parliament decided on a Climate policy framework for Sweden. The framework consists of three parts: long-term goals, a planning and monitoring system, and a Climate Policy Council. Parts of the framework are regulated by a Climate Act, which came into force on January 1st, 2018. The National Climate Policy Council has duties of evaluating if the present

policies contribute or counteract the climate goals, reviewing the effects of both existing and planned policies from a broad societal perspective and identify policy areas where additional measures need to be taken if the climate goals are to be achieved. Besides evaluating government policy, the National Climate Policy Council evaluates the analytical methods and models which are at the basis of the policies, as well as contributing to the debate regarding climate policy2.

Despite the similar names, though, the National Climate Policy Council and Regional Climate Councils have a totally different structure, organization, goal and set of resources.

Jönköping Climate Council

In some cases, the goals of the regional institutions are higher than the ones of the National’s Climate Council, as in Jönköping’s County. Jönköping County’s Climate Council counts more than 50 actors, from building to energy companies, to food and design ones. The Climate Council in Jönköping has been founded in 2011. Focus areas for Jönköping County’s Climate Council are energy efficiency, sustainable transport, renewable energy production, sustainable agriculture techniques and climate change. Plus, it has a

communication group and an event group that organizes events like Climate Week and the Solsafari3.

Jönköping County is rooted in sustainable development as a Region in all its aspects: economical, social and environmental. Located in the South-central part of Sweden, the County of Jönköping is subdivided into 13 local municipalities with a population of just over 333 000 inhabitants. About 30 % of the population lives in rural areas outside of urban centers. The Region has a population density of about 32 inhabitants/km2 which

is higher than the national average of 22/km2. About 76 % of the land is forested (production forest and

protected) which is significantly higher than the national average of about 56 % (2016). The Region has a varied industry sector structure with many small and medium-sized enterprises, and it is known for its entrepreneurship. Jönköping is one of the most industrialized Regions in the country with a vibrant manufacturing industry. There is a whole range of biomass and biomass related projects such as logistics, upgrading, processing, distribution, conversions recently completed or in progress throughout the Region4. A

2 https://www.klimatpolitiskaradet.se/ 3 https://klimatradet.se/

4

development program in collaboration with the European Union specifies measures and strategies in entrepreneurship, creation of new business and a diversified, ethical and environmentally driven business sector5.

Västra Götaland Climate Council

Västra Götaland works towards its climate target since 2009. The transition to an attractive and climate-smart society can lead to many positive effects such as improved health, new jobs, and increased integration and involvement. To speed up the efforts to reach the climate target of the Region, all players in Västra Götaland need to take action – meaning the public sector, universities, businesses, organizations and individual citizens. Readjustments will take place within people’s organizations and in widespread collaborations across organizational boundaries. Västra Götaland’s Climate Council has been founded in 2017 and it counts 15 important representatives from the companies of the Region, going from the environmental manager of Nudie Jeans to the vice presidents of public affairs at Volvo.

Focus areas for the Climate Council of Västra Götaland are sustainable transport, climate-smart and healthy food, renewable and resource-efficient products and services and healthy and climate-smart home buildings6.

Västra Götaland counts 1.6 million inhabitants and is, therefore, the second largest populated Region in Sweden after Stockholm (density of population is 68 inhabitants/km2). Västra Götaland provides the

prerequisites for good public health, a rich cultural life, a good environment, jobs, research, education and good communications. All together, these provide a foundation for sustainable growth in Västra Götaland. Västra Götaland follows a sustainable model of development and growth and is for this reason recognized as a good practice in terms of environmental industries clusters7.

Jämtland Climate Council

The model of the Jämtland Climate Council gives a holistic, and at the same time very detailed, view of the Region itself, allowing for the determination of targets of major importance and where measures can or should be taken. The development of such model calls for the inclusion of continuous cooperation with other stakeholders, which is necessary to prevent misunderstanding. Jämtland Climate Council counts around 40 actors, going from the University to transport, food, tourism companies. The council divides the job into 4 “Arbetsgrupper” – working groups, everyone with each specific competence: transports, energy supply, lifestyle and climate change8. Jämtland Region counts 115,331 inhabitants with a density of population of

3.4/km2 (2016). Östersund is the center of trade and commerce in Jämtland: except for the city, Jämtland is a

5 https://ec.europa.eu/ 6 https://klimat2030.se/

7 https://www.lansstyrelsen.se/vastra-gotaland.html

5

very sparsely populated Region. Jämtland’s economy has its roots in the extraction of raw materials but most of all in the developed tourism sector: the tourism in Jämtland is dominated by winter sports and especially alpine skiing in various facilities in Åre, Bydalen, Storlien. Region Jämtland Härjedalen is regionally responsible for development and Regional growth, especially focusing on efforts for sustainable Regional growth and development9.

The table here displayed presents the main data about the three Climate Councils.

Jönköping Climate Council Västra Götaland Climate Council Jämtland Climate Council Established in 2011 Established in 2017, climate

strategy started already in 2009

Established in 2014

Counts 5 members, divided in 7 core areas

Counts 15 members, divided in 4 core areas

Counts 40 members, divided in 4 core areas 333 000 inhabitants, 32 inhabitants/km2 1.6 million inhabitants, 68 inhabitants/km2 115,331 inhabitants, 3.4 inhabitants/km2

One of the most industrialized regions in the country

Second largest populated Region with a good job and educational environment

Economy has its roots in the extraction of raw materials but most of all in the developed tourism sector

Purpose

Nationals, Europeans, and international guidelines for sustainable future development merge and cohabit in our present. Institutional environment is considered as the rule of the game for collaborations to happen. Multilevel governance is indeed executed through the Swedish Climate Policy, then the European Union Climate Policy and the international Kyoto Protocol. This multilevel dilemma of multi-actors’ rules and policies opens up new spaces for more locally-oriented institutions like the Climate Councils, analyzed in this study.

The creation and design of local climate policy match with more flexibility, a better view on the needs and possibilities of the territory and different logic of actions.

In this process, communication plays a vital role in exchanging information both internally and externally of the institution. First of all, the degree of unanimity and certainty among scientists and policy-makers about the state of the climate and adequate countermeasures is crucial to the success of any climate strategy, in

9 https://www.lansstyrelsen.se/jamtland/

6

order to affect individual consciousness and response (Lundqvist, 2007). Clarity, trustworthiness, and transparency of the institutions play a vital role in the success of the collaborative act. An empirical research gap is recognizable in how authorities as in this case collaborate in the frame of sustainable development and of its communication. The purpose of the study here presented is to highlight the importance of

communication within collaborative structures, as regards the reality of the Climate Councils in Sweden. Collaborations arise with different aims and targets but still, they have communication at their core. The study will, therefore, analyze how communication makes collaboration possible.

Delimitation of the study

Cross-sectoral, public-private collaborations have received so far little interest in the community, especially the communication aspect within collaborations. Considering the increased focus on collaborative processes within the literature, there is a gap about CSPP on a local level and about their contextual reality,

collaboration structure and communication practice. This paper addresses cross-sectoral, public-private collaboration examples and their communication practices, where literature gaps have been found and these are investigated within the context of the communication aspect in collaborations. Sample of analysis includes three Climate Councils – Swedish Regional institutions, in particular Jönköping, Västra Götaland and Jämtland Climate Council.

There is a growing interest of cross-sectoral, public-private collaborations that strive to act for climate change and sustainable development, and Climate Councils represent a reply to the sustainability challenges that the business and social world are called to answer. The study analyzes the actors’ motivations for collaboration, the challenges faced throughout the venture development process and their impact within their field of action. Moreover, an important focus is put on the importance of communication within Climate Councils, which is to be considered not only as information exchange, but most of all as a factor of success for collaborations.

7 Aim and research questions

This study wants to examine the collaborative processes behind the Climate Council institutions, concerning external communication, internal communication, and forms of collaboration. The gap in research that this study wants to fill regards the institution of the Climate Council. The institutions taken into consideration for the study are based in the Regions of Jönköpings Län, Västra Götaland Län and Jämtland Län. The three Councils’ practices – their collaborative structures and communication processes - are compared in the study, to highlight the different approaches carried out by the three similar establishments. Even though

collaboration structures differ in the three Councils, communication plays a vital role in all of them.

RQ1: How do Climate Councils work to realize the promise of collaboration?

The perspective of the thesis is on the collaborative act between actors from different sectors and

organizations, both public and private, that collaborate for the common goal of sustainable development. As regards these unique and new forms of collaboration, the collaborative effort among these very different participants is already to be considered as an important newly generated value.

RQ2: How do Climate Councils communicate internally and externally?

Institutional communication targets both internal and external actors and differ from other communicative concepts because of the uniqueness of the institutions analyzed.

Key issues emerge and are analyzed by answering to the two research questions, regarding cross – sectoral, public – private collaboration in the frame of sustainable development, with an important focus on the communication practices.

8 Previous research

This study finds its roots in a multiplicity of previous researches. Seen the number of different concepts and pillars that this study addresses, previous research spans from cross-sectoral and public-private collaboration to the communication aspect involved.

Cross-sectoral collaboration

Bryson, in his study from 2006 called “The Design and Implementation of cross-sector collaborations”, defines collaborations as “involving government, business, nonprofits and philanthropies, communities, and/or the public as a whole". After his study here mentioned, new empirical and theoretical frameworks about collaboration have been developed, which Bryson collects and analyzes in a study from 2016 called “Designing and Implementing Cross-Sector Collaborations: Needed and Challenging”. To start with, it is important to highlight that determinants of the collaborative governance regime are rooted in the external context, including resources’ conditions, policy and legal frameworks, politics and power conditions. Even when general environmental conditions favor the formation of cross-sector collaborations, they are unlikely to get underway without the presence of more specific drivers or initial conditions. In the study, Bryson reviews all the assets that make collaborations effective. Collaborative processes have their roots in trust, commitment, communication, legitimacy and collaborative planning (Bryson, 2016, 652).

Cross-sector collaborations have proliferated in recent years for a variety of reasons, but first and foremost because organizations within the collaboration are trying to accomplish something, they could not achieve by themselves (Provan and Kenis 2008, 240). Many see such arrangements as a necessary approach in dealing with challenging public problems (Bryson, Crosby, and Bloomberg 2014; Kettl 2015; Popp et al. 2014). In the last decade, scholars have developed comprehensive theoretical frameworks for understanding cross-sector collaborations and how they might produce desirable outcomes. The frameworks in question have much in common, but they differ in important ways. Collectively, they show that cross sector collaboration is a very complex phenomenon that should be conceptualized as a dynamic system. The complexity is

inescapable because these collaborations are dynamic fields that brush up against and are penetrated by other dynamic fields (Fligstein and McAdam, 2012). A systemic view is necessary in order to understand how the parts fit together and to avoid unintended deleterious effects. The challenge for scholars is clear, as Berardo, Heikkila, and Gerlak note: “Collaboration processes are complex enough to demand a simultaneous analysis of all its moving parts, a goal that should drive future research efforts in this area” (Berardo, 2014, 701). The challenge for practice is the same: how to understand collaborations and their moving parts well enough to actually produce good results and minimize failure.

As regards sustainable development, cross-sectoral collaboration governance comprises a mix of compulsion and voluntarism, implying the need for collaborative approaches to address complex changes. In a study from Fenton and Gustafsson about multi-governance for sustainable development, particularly as regards to

9

cities and municipalities’ governments, it is stated that “sustainable development is one of many arenas for inter-municipal competition, and part of wider processes framing the production of knowledge. This, and the extent to which policies are present or absent across contexts, forms part of the flourishing literature on policy mobilities. Such literature points to a need for pluralism and reflexivity in the practice and study of governing for sustainable development and cities, particularly with issues of representation” (Fenton, Gustafsson, 2017, 130). The discovery and acceptance of collaboration as a key organizing theme for building sustainable societies takes a great deal of construction and reconstruction.

Nguyen & Janssen analyze how the cross-sectoral collaboration process unfolds: it cannot be assumed that partnership stages (Austin, 2000) or partner differences – in terms of power (Gray, Purdy, 2014), logics (Gray, 2004) or culture (Berger et al., 2004) – are enabling or constraining factors; rather they become relevant context as they are talked into being. Cross – sectoral collaborations are recognized as a continuous development of the initial conditions.

Author(s) Definition

Bryson, 2006 Cross-sectoral collaborations involve government, business, nonprofits and philanthropies,

communities, and/or the public as a whole and have their roots in trust, commitment, communication, legitimacy and collaborative planning.

Provan and Kenis, 2008, 240 Organizations in the collaboration are trying to accomplish something they could not achieve by themselves

Fligstein and McAdam 2012 Collaborations are dynamic fields that brush up against and are penetrated by other dynamic fields

Further development of the concept of cross-sectoral collaboration is represented by the concept of social partnerships, as defined by Waddock as “social problem-solving mechanisms among organizations”, (Waddock, 1989, 79) that primarily address social issues such as the environment by combining organizational resources to offer solutions that benefit partners, as well as society at large.

It is within this frame that Seitanidi and Crane address the need for studies about “micro-level processes".

10 Public-private collaboration

Googins defines public-private collaborations as: “Public-private partnerships all speak to a new frame for how society begins to organize and respond to common issues and concerns. The assumptions underlying this framework are that no sector can or should dominate public life, and that no one sector has sufficient resources or capability to adequately address or resolve common social issues” (Googins, 2000, 128). Public - private collaborations are a particular type of cross-sectoral collaborations based on formal,

contractual relationships between two or more entities, belonging to the public sector on one hand - meaning the government, the Region, the local administration - and the private sector on the other hand - meaning companies, industries, offices, … Since the 1990s, public–private collaborations have been promoted as tools for good governance that can increase the legitimacy, effectiveness and efficiency of multilateral

environmental politics.

Public–private collaborations are defined as: “alliances, partnerships, roundtables, networks, and consortia— in order to promote innovation, enter new markets, and deal with intractable social problems” (Dyer & Singh, 1998).

The link between intersectoral collaborations and sustainable development was formalized when partnerships were declared an important tool for implementing sustainable development at the 2002 WSSD in

Johannesburg (Hens, Nath 2003; Norris 2005; Eweje 2007). In this frame, a study carried out by Karin Bäckstrand compares two examples of public-private collaboration, namely Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Johannesburg partnerships adopted at the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD), in terms of inclusiveness, deliberation, accountability, institutional effectiveness and environmental effectiveness. The Johannesburg partnerships have been advanced as innovations in global sustainability governance and generally hailed as a success (United Nations, 2008). Similarly, the CDM has also been framed as “a mechanism that can deliver better governance in terms of both cost and environmental effectiveness” (Streck, 2004; Streck and Chagas, 2007, 62).

All in all, the debate on the promises and pitfalls of partnerships is also polarized between the liberal - functionalist perspective claiming that partnerships are win–win instruments that can decrease the three deficits, and the critical governance perspective arguing that partnerships reinforce market environmentalism and privatization. Beyond this contested argument there is the need for a comparative empirical research that assesses the performance of public–private partnerships across different sectors and in different multilateral settings. As a result, the separation between “new” modes of public–private partnership governance and “old” modes of regulation, command and control is an analytical distinction that does not hold in political reality. Public-private collaborations operate in the shadow of the hierarchy with background conditions of state authority, intervention, steering and control (Bäckstrand, 2010).

A study by Huxham and Vangen, highlights the key factors to be taken into consideration in a successful public-private collaboration: managing aims, compromise, communication, democracy and equality, power

11

and trust. Findings of their study highlight that the dilemma for public-private collaborations concerns agreement among actors involved about broad aims and about detailed actions to allow the joint initiative to progress (Huxham, Vangen, 1996). This reflects on public private collaborations in the field of sustainable development activities whereas the actors involved need to agree and discuss their positions towards a more sustainable way of action. PPPs play a vital role in the development of comprehensive sustainability

connected actions.

Author(s) Definition

Googins, 2000, 128 No sector can or should dominate public life, and that no one sector has sufficient resources or capability to adequately address or resolve common social issues

Dyer & Singh, 1998 Alliances, partnerships, roundtables, networks, and consortia—in order to promote innovation, enter new markets, and deal with intractable social problems

Bäckstrand, 2008 Public private collaborations operate in the shadow of the hierarchy with background conditions of state authority, intervention, steering and control Huxham, Vangen, 1996 There has to be at least enough agreement about

broad aims and about detailed actions to allow the joint initiative to progress

Communication in cross-sectoral collaboration

In a study carried out by Koschmann & Kuhn, a framework for increasing and assessing cross-sector collaborations’ value is developed, and it has its roots in alternative conceptions of organizational

constitution rooted in communication theory. Starting with defining cross-sectoral collaborations as a unique form of social organization, “multilateral collectives that engage in mutual problem solving, information sharing, and resource allocation” (Koschmann, Kuhn, 2012, 332). The focal argument of this study is that “the overall value of cross-sectoral collaborations is not merely in connecting interested parties but, rather, in their ability to act—to substantially influence the people and issues within their problem domain”

(Koschmann, Kuhn, 2012, 332). Communication is key in the functioning of cross-sectoral collaboration and therefore his study investigates the way in which communication processes facilitate the emergence of distinct organizational forms that have the capacity to act upon, and on behalf of, their members.

12

The framework depicts that communication practices of increasing meaningful participation, managing centripetal and centrifugal forces in the collaboration process, and creating distinct and stable identities can enhance the potential for a cross-sectoral collaboration’s trajectory to develop collective agency and its capacity for value. Given the practical nature of the framework proposed, it naturally has some immediate implications for practice. First, a communicative perspective encourages cross-sectoral collaborations’ meetings facilitators to find ways to encourage meaningful participation and to include a diverse range of participants’ interests in the discussion. Finally in this study, communication has the capacity to constitute and sustain complex organizational forms like collaborations that display value through their collective agency—their ability to have a meaningful impact on the people, organizations, and issues involved in a given problem domain.

Googins, in his study, delineates the role of communication for intermediation in collaborations: “creating more and more major institutions and intermediaries across the sectors of society have entered the fray in an attempt to encourage corporate-community involvement and to catalyze the formation of cross-sector partnerships”. (Googins, 2000, 132).

The premise here is that communication in collaborations “cannot be sustained by limited and sterile conceptions of communication grounded in linear models of information exchange” (Koschmann, 2016, 408), rather it has to have a wider objective, target and model. In the case of collaboration, communication plays the important constitutive role in the collaboration itself. Scholars have defined the term

communicative constitution of organization (CCO) to connote a more explicitly constitutive approach to communication and organizational theory (Ashcraft et al., 2009; Putnam, Phillips, & Chapman, 1999). The highlight on the communication aspect for collaboration is given by Craig (1999), who defines a

“communicational perspective on social reality”, specifically organizational collaborations where organizations exist within a dynamic, relational landscape consisting of various network relationships. Koschmann summarizes that a communication perspective helps in explaining collaborative relationships as dynamic sites of organizational constitutions where negotiation and meaning construction shape how

organizational realities are known and experienced (Koschmann, 2016, 424). Communication is, therefore, at the center of the construction of a coherent and effective image of the collaboration.

This study fills the gap regarding cross-sectoral, public-private collaborations on a local level: before it has never been carried a comparative study about the institution of the Climate Councils, in particular. Climate Councils in Sweden are a peculiar yet positive example of effective collaboration in terms of sustainable development and climate change. Climate councils, by collaborating on a Regional basis, strive to have a positive impact on the National level.

13 Theoretical framework

The theoretical background of this study finds its roots in key concepts for the analysis of collaborative institutions that work in the field of sustainability and of climate change. The term collaboration is narrowed down to collaborations in the sustainable development field. Still, there is a difficulty in dividing the

communication aspect from the collaboration structure, because communication is a basilar aspect for the correct functioning of collaborations.

Collaboration

Collaboration has emerged as one of the defining concepts of international development in the 21st century. Initially, in part as a response to the limitations of traditional state-led, top-down development approaches, collaborative modes have grown to become an essential paradigm in sustainable development (Stibbe, Reid, 2018). Collaborations have indeed become a common answer to the new challenges emerging in every sector. Different factors affect the existence of sustainable collaborations, i.e.: drivers, motivations, partners’ characteristics, process issues and outcomes. What emerges as a driver for collaborations is the possibility to complement each other’s strengths and weaknesses by accessing to other’s skills, resources and capabilities (Bryson, 2015).

After an exhaustive literature review, Bryson developed a framework that clearly shows fundamental aspects that need to be considered when putting up a collaborative entity. The framework developed by Bryson has its roots in antecedent conditions and drivers for collaboration. This two elements, if coordinated, give space for a creation of collaborative processes and structures: the former are defined as “processes that unite organizations and make it possible for actors to establish comprehensive structures” and the latter as “management of tensions between opposites, formal and informal networks”. Collaborative processes and structures work in intersection that could face threats by endemic conflicts and tensions and, on the other hand, can be favored by leadership and capacity. At the end of the model there are accountabilities and outcomes: newly generated value is one of the outcomes emerging from an effective collaboration.

14

As regards the creation of new, effective collaborations, according to the institutional perspective, the key issue is the actual and possible role and function of collaborations in an environmental governance regime. Drivers for collaborations can be found in business motives for economic development, and government motives for the protection of public goods. Aims and goals in collaborations do not contradict, rather they complement.

The communication aspect is not mentioned in the presented model, even if communication stands at the core of enabling an efficient collaboration.

Different models exist to explain the collaboration phenomenon. All they have in common is the recognition of the fact that collaborations should be treated as a dynamic and interdisciplinary phenomena.

Value creation in collaboration

The notion of value is multifaceted and has different shapes of meanings regarding the sector and the entity discussed. Definitions of value go from a more neo-classical approach to a newer, “win–win” perspective.

Accountabilities and outcomes

Fig. 1 – Collaboration model by Bryson

Antecedent conditions

- Institutional environment

- Business environment

Drivers - Agreement on aims Collaborative Processes - Trust - Committment Collaborative Structures - Development of rules - Creation of working groups Conflictsand tensions

15

Author(s) Definition

Porter and Kramer (2001, 66) Policies and operating practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company while

simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities in which it operates. Shared value creation focuses on identifying and expanding the connections between

societal and economic progress

Wheeler et al. (2003, 20) It will not be too long before we can begin to assert that the business of business is the creation of sustainable value, economic, social and ecological Kurucz et al. (2008, 91) Connecting stakeholder interests, and creating

pluralistic definitions of value for multiple stakeholders simultaneously

Emerson (2003, 44) A Blended Value orientation at corporate and sectoral levels assumes that the optimum

investment is one that acknowledges the reality of blended economic and social value

and attempts to maximize total returns

Austin and Seitanidi (2012, 945) The transitory and enduring benefits relative to the costs that are generated due to the interaction of the collaborators and that accrue to organizations, individuals, and society

In a study carried out by Le Pennec, in order to identify the different types of value that are created in a collaboration, the Austin and Seitanidi’s Collaborative Value Creation framework of value creation in nonprofit–business collaboration is used. The case study results in the fact that collaboration tends to become the desired outcome itself, and not simply the vehicle for value creation. Four objectives concur when collaborating: legitimacy – oriented motivations, competency – oriented motivations, resource – oriented motivations and finally society – oriented motivations.

The transfer of tangible and intangible resources (in the form of new tools, methods, and opportunities) to the partners who are working on the project did create transferred value; the individuals learned these new tools and methods, which helped them to gain efficiency and efficacy in the conduct of their administrative and managerial duties. In the end, the transferred value is related to the implementation rather than the innovation within and related to the project.

16

The associational value, which began with the joint scoping of the project, led to the transfer of value between the organizations that are involved in the form of skills, financial resources, and tools. Interactional value stemmed from the repeated interactions between individuals from the organizations that are involved in the project and brought about the creation of intangible resources and values. The synergistic value builds on the three types of previously created values mentioned above. Indeed, transferred value (particularly knowledge and skills acquired, funding, and access to networks) combined with interactional value (relationships of trust, transparency, and coordination, among others) allowed partners, as they put it, to ”enlarge perspectives”, “change paradigms”, “break with stereotypes”, and “innovate”. As regards sustainable developments actions, trust and commitment to the generation of new value are key.

In a collaborative framework, a collaboration continuum exists, and while value is always exchanged among partners in collaborations, partners achieve greater value as they deepen their relationships (Austin and Seitanidi, 2012).

Sustainability

The concept of sustainability has its roots in what might be called “the crisis of development”, that can be defined as the failure since World War II of international development schemes intended to improve impoverished peoples around the world. In 1983 the United Nations convened the World Commission on Environment and Development to address these problems. This Commission (later called the Brundtland Commission after its chair, Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland) set about the task of developing ways to address the deterioration of natural resources and the decrease of the quality of life on a global scale. In its 1987 report, the Brundtland Commission described this problem as arising from a rapid growth in human population and consumption and a concomitant decline in the capacity of the Earth’s natural systems to meet humans’ growing needs. The Brundtland definition provides a new vision of development - optimistic in tone but laced with challenges and contradictions. It suggests that we have a moral responsibility to consider the welfare of both present and future inhabitants of our planet - a serious task indeed. Environmental values make the ethics of sustainability both especially challenging and especially promising.

What is understandable from the broad concept of sustainability, is that it is to be considered not as a single goal, carried out by a single institution, and it cannot be treated in light of a single issue or achieved by attending to only one kind of problem.

Sustainability challenges that society is tackling now are different in kind from the environmental challenges the society faced in the past: Hedenus, Persson and Sprei state that the latter – water pollution, smog ad example – were local, had clear cause-and-effect chains and were relatively simple to solve; the former – climate change – is a global crisis, with effects spread unconditionally (Hedenus, Persson, Sprei, 2018, 134). They define these contemporary issues as “wicked problems”: climate change is characterized by not having

17

unique and objective optimal solutions and parties involved in tackling it cannot agree on how to define it. Wicked problems cannot just be left to a group of experts with the objective to solve them, and moreover they are dynamic and changing over time. That is why sustainability-related issues call for a broader expertise (Hedenus, Persson, Sprei, 2018, 136).

Sustainable development goals

The importance of the collaborative model has been fully recognized by the UN, by businesses and by all leading institutions in international development. The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – the blueprint for global development represents a fundamental shift in thinking, explicitly acknowledging the interconnectedness of prosperous business, a thriving society and a healthy environment (Stibbe, 2018). The implementation of the SDGs requires multi-level governance to stimulate action across many levels, scales and sectors. The goals included in Agenda 2030 are actively doable, most of all in relation to the cost of not doing them. The UN system defines collaborations for the SDGs as follows: “multi-stakeholder initiatives voluntarily undertaken by Governments, intergovernmental organizations, major groups and other stakeholders, which efforts are contributing to the implementation of inter-governmentally, agreed

development goals and commitments”. Goal 17 of the Agenda 2030, issued by the United Nations, is about strengthening the means of implementation and revitalize the global collaborations for sustainable

development. SDGs can only be realized with strong, global collaboration and cooperation. Collaboration structures in an interconnected world are recognized as a positive example to tackle complex issues, such as climate adaptation and change.

Framing

It is important to state the concept of framing regarding climate change. “Framing” has been described as a process by which actors construct and represent meaning to understand a particular event, process or occurrence (Goffman, 1974; Gray, 2003). Framing needs a social space where frames can circulate.

Framing is constructed thanks to the contributions of all the key players taken into consideration. In order to gain positive outcomes, it is important to define the problem and the challenges addressed, meaning

conceptual distinction accounting for the problematization process in a particular context. The issue of how to frame ethical problems in constructive and fruitful ways is especially relevant for problems of

sustainability, where popular discourse often defines problems as stark choices between economic or environmental goods. In such situations, one of the most important tasks of ethics is asking questions that help lead to good solutions. Focusing on the environmental and sustainability topics which this study focuses on, as pointed out by Teresa Kramarz, regarding the framing of environmental issues, increasing

18

As stated by Hansen, framing has its principles in selection, emphasis and salience in communication content, “which may contribute to the structuring of public and political responses by directing attention to how an issue or problem is defined, who is cast as being responsible and what solutions are proposed or implied for remedying the issue” (Hansen, 2019, 181).

Accountability

Focus is on accountability: as Karin Bäckstrand highlights in her study from 2006, then further developed two years after, the proliferation of climate collaborations is tied to the rise of transnational networked governance, involving multi-sectoral collaboration between civil society, government and market actors (Bäckstrand, 2008, 74). Collaboration calls for accountability, defined as a tool that identifies what the object is for holding people to account, such as mitigating environmental damage, as well as how they should be held to account, through transparent standards of assessment. Evidence is still required to support the argument that any kind of accountability measure has a positive effect. In the first place, there is a great deal of ambiguity and widespread disagreement about the details and achievability of sustainability (Hediger, 1999). Moreover, supportive and critical views of collaborations coexist.

Accountability procedures are designed to ensure that authority holders are responsible and answerable for their actions within the governance institution’s goals, accountability procedures to increase transparency, the reasoning for government decisions (Kramarz, 2016, 1). Accountability in networks becomes more complex since sites of governance are dispersed: in a network there are multiple key actors and, therefore, reputational accountability and credibility become crucial. The availability, open access and transparency of both information and extensive monitoring mechanisms are important dimensions of accountability. In the example of climate councils, transparency can be found in the publishing of different reports both on the regional and national levels.

Accountability for an institution finds its target in the stakeholders of the institution, whereas stakeholders can be defined as “no longer targets to hit, but people to engage” (Sobrero, 2018, 39).

As mentioned in Bryson’s model, accountability “is a particularly complex issue for collaborations because it can be unclear to whom the collaborative institution is accountable and for what” (Bryson, 2015, 657).

Institutional communication

Communication is an important tool for the success of cross-sectoral collaborations. For communication to effectively function, there is a need of a coherent framework regarding both the internal and external

communication of the institution. Interaction and dialogue among the members stand at the heart of effective institutional communication. Institutional communication activities are divided in internal and external

19

communication. Lammers states: “institutional messages provide a conceptual and empirical link between the predominantly macro-world of institutions and the micro-world of organizational communication”. Even if institutional communication is not much developed as a concept, it is the best concept to describe the communication activity of the Climate Council institutions. Meetings occurring within the Climate Council are the starting point for both internal and external communication for this kind of institution: the meeting is the institutionalized dialogue form for the organization. The concept finds its roots in organizational

communication but represents a wider view of the former. Institutional communication has both an internal and an external audience. Internal communication is needed for effective collaboration; to both answer research questions and disseminate the results. External communication, on the other hand, is the exchange of information between the institution and those external to it. External communication must be consistent and clear, across all methods of engagement. This requires establishing a recognizable identity for the institution, creating key communication messages, and identifying the institutions’ audiences. Internal and external communication have the goal to create a coherent discourse. Communication must express coherent institutional goals of the organization so that they can be understood and shared by all members of the organization and by the society where they act.

Engagement is at the center of the communicative process, where feedback on the communication activities is encouraged from every stakeholder (Coombs, 2012, 135). Collaborative efforts should be transparent and clear, because companies are considered “houses made of glass”, in which transparency and responsibility become fundamental (Sobrero, 2018, 125). Institutional communication becomes sustainable whereas it widens in a programmatic way “the relationship between explanation and implementation, hence an enlarged view of sharing the central themes discussed within the institution” (Sobrero, 2018, 153).

It is important to note that communication regarding environmental issues is characterized by a vocabulary that could sound familiar and recognizable, still it lurks some immensely complex issues, that require a great deal of engagement (Hansen, 2019,1). This explains why institutional communication about environmental issues and climate change policy seems so difficult to analyze and to distinguish from the whole institution’s body.

20 Methods and material

“Methods are but a means to an end, important though they are, they are not an end in themselves, nor should they be used, as they have been, to determine the end or define the nature of the problems to be investigated” (Halloran, 1998, 10 – 11). This work has the aim to use two different methods to gather the data needed: interviews and critical discourse analysis, in order to arrive at a final comparison between the results of the different methods.

Interviews took place from 2nd March 2020 to 20th March 2020 with representatives of the Climate Councils

in each Region taken into consideration, hence Västra Götaland Län, Jönköping Län and Jämtland Län. In the first place, the main reason behind the usage of interviews as a research method is that they allow the understanding of reasons, modes and traditions behind the collaboration set up between the Climate Council and the companies. During the time of one month, interviews have been done with representatives of the Västra Götaland Region, County Administration of Västra Götaland Region, Jönköping County

Administration and Jämtland County Administrations. The first three interviews took place face-to-face, and the last one took place online, due to logistic matters. These interviews are structured through a list of key themes and issues prepared from the researcher, although they tend to be semi-structured and open-ended, allowing the discussion to develop along any interesting line. Interviews are used to get personal accounts of behaviors, opinions, and experiences: they are often used to support or explore other kinds of data. In order to avoid any ethical problem, a consent form is presented to the respondents who accept it and sign it. The interview method is chosen because it gives great freedom to the interviewer to explore issues and produce information in greater detail.

Critical discourse analysis is utilized in this study to research and show features of the language utilized in the reports issued by the three institutions - Västra Götaland Län CC, Jönköping Län CC and Jämtland Län CC. The three reports can be found on the website of each Climate Council and then downloaded. In this report, the whole discourse regarding the Climate Councils is largely developed: the term “discourse” is central to CDA. In the concept of Fairclough (1997), he explains that discourses project values and ideas and in turn contribute to the reproduction of social life. Therefore, it is through language that we constitute the social world. Finally, Critical Discourse Analysis provides a set of tools used to describe the language and grammar choices in a text and to draw out the ideology of a text, by pointing to the details of language. Västra Götaland Län Climate Council issued a report called “Västra Götaland - Ställer om!”, composed of 8 pages, written in English. The report is downloadable from the website of the Climate Council.

Jönköping Län Climate Council issued a report called “Klimatsmart Jönköping Län + Plusenergilän 2050”, composed of 12 pages, written in Swedish – then translated in English. The report is downloadable from the website of the Climate Council.

21

Jämtland Län issued a report called “Fossilbränslefritt 2030 Jämtlands Län”, composed of 36 pages, written in Swedish – then translated in English. The report is downloadable from the website of the Climate Council. This study wants to shed a light on the collaboration and communication aspects behind the institution of the Climate Council, peculiar in Sweden: qualitative investigation seems like the most suitable method to gain a deeper understanding of the practices put in place by the Climate Councils. Qualitative structure allows the data to emerge in a flexible way (Bryman, 2008).

The choice of the sample of the analysis – Jönköping Climate Council, Västra Götaland Climate Council and Jämtland Climate Council – is dictated by personal reasons, due to previous contact of the researcher with representatives of the three institutions. It is important to note that Climate Councils in Sweden are not peculiar just in these three regions, but other embryonal examples of Climate Councils are arising in other Regions as well. The three Climate Councils here analyzed are the most developed as for now, therefore the most prominent to be studied.

Methods selected to carry out the analysis will have their focus only on the collaboration and communication aspects of the Climate Councils institutions.

Interviews design

Interviews are a prevalent method of collecting primary data within qualitative studies, allowing the respondent to express his point of view. To gather data needed for this paper, qualitative semi-structured interviews are conducted with representatives of the three different Climate Councils. With semi-structured interview, the interviewer does not strictly follow a formalized list of questions, instead more open-ended questions are conducted, allowing for a discussion with the interviewee rather than a straightforward question and answer format. As Bryman states, “qualitative semi-structured interviews tend to be flexible, responding to the direction in which interviewees take the interview and perhaps adjusting the emphases in the research as a result of significant issues that emerge in the course of interviews” (Bryman, 2012, 470): in this case, a series of questions have been asked even if they were not in the list of the initial questions, in order to follow the flow of the discourse between the interviewer and the interviewee. Semi-structured interviews are approaches that allow the researcher a potentially much richer and more sensitive type of data (Hansen, Manchin, 2019). Flexibility makes this tool suitable to analyze such a rich institution.

Four semi-structured interviews for this study took place. First of all, one with the representative of the Region Västra Götaland for the Climate Council, Amanda Martling, followed by an interview with the representative from the County Administration of Västra Götaland for the Climate Council, Svante Sjöstedt. These two interviews took place in Göteborg. Then, an interview with the administrator of the Climate Council in Jönköping, Andreas Olsson, which took place in Jönköping. The last interview is with Lars

22

Jonsson, representative of the Jämtland Climate Council, online. Interviews have been recorded. Before the start of the interviews, an interview consent form has been presented to the respondents. After the

completion of the interview, transcripts were written.

Interviewee Date Duration Place

Amanda Martling 03/03/2020 57:56 min Region Västra Götaland

Svante Sjöstedt 04/03/2020 46:54 min Länsstyrelsen Västra

Götaland

Andreas Olsson 11/03/2020 31:17 min Länsstyrelsen Jönköping

Lars Jonsson 18/03/2020 35:40 min Skype

Interviews follow a semi-structured design. The first thing asked is the possibility to record the interview, to have the possibility to transcript the answers in a separate time. Questions regard, in general, key figures about the institution of the climate council and about the strategies put in place. Subsequently, more focus is put on the themes of internal and external communication and collaboration. The interviews end with a “goals for the future” section. The table here covers the interviews topics, and the questions are found in the Appendix.

1. Introductory questions 2. General context questions 3. Collaboration structure 4. Communication processes

5. Accountability to the stakeholders 6. Goals for the future of the institution

Critical Discourse Analysis

Critical Discourse Analysis aims at highlight and revealing facts hidden in the discourse, by answering to questions such as what is the discourse doing? How is the discourse constructed to make this happen? What resources are available to perform this activity? (Potter, 2004, 269). According to Fairclough, 1997,

discourse constitutes society and culture: the way people talk about things constitute society but society also Tab. 6 – Interview design

23

constitutes how people talk about things. Furthermore, discourse can only be understood with reference to the historical context, extralinguistic factors such as culture, society and ideology matters.

CDA will be applied in the study to three reports from the three institutions and it has the aim at revealing and confirming major themes emerged from the interviews in the frame of collaborations. The critical discourse analysis will inspect lexical choices of the reports, especially focusing on the pronouns used. The selection and usage of pronoun “we” instead of “I” depicts the importance of the plurality of subjects involved within the collaboration, especially focusing on how everyone has got a role and a duty for the collaboration to actually function. In this case, the critical discourse analysis will highlights these functions.

Reliability and validity

The reliability of the research can be defined as “the extent to which your data collection techniques or analysis procedures will yield consistent findings” (Saunders et al., 2009). Reliability of qualitative,

interview data can be challenging due to the uniqueness of each interview. This variation in findings can be due to differences in questions asked. To ensure reliability, one-on-one interviews with an interview guide were conducted. Prior to the questions, the interviewer was introduced aiming at creating familiarity and comfort. Moreover, interviewees were asked if they understood the questions, in order to decrease misunderstanding and thus unreliable answers. Probing further allowed the elaboration on questions to support understanding of the questions (Zikmund, 2000).

Reliability of the quantitative research is assured through the critical discourse analysis.

Validity is defined as “whether the findings are really about what they appear to be about” (Saunders et al., 2009). In order to ensure validity within the research, a mixed-method approach of interviews and Critical Discourse Analysis is used.

Validity in qualitative data is much discussed among researches. They argued that validity does not apply to qualitative research, yet realise the necessity for a qualifying analysis or measure in research. Techniques utilised to increase validity in this research were the recording and transcribing of the interviews. These techniques were implemented to ensure correct recollection of qualitative data and thus reducing interviewer bias (Griggs, 1987; Hirschman, 1986).

24 Analysis

Dynamics and structures of the Climate Councils analyzed in this study are different in several aspects, but they all aim at creating a transferred and interactional value, thanks to the collaborative efforts. The two main focuses of the thesis regard the collaboration structures and the communication practices, which are here highlighted through findings coming from the interviews and the critical discourse analysis.

Jönköping Climate Council has been founded in 2011 with the goal to become a surplus, self-sufficient energy County. Preliminary work behind the actual introduction of the Climate Council started in 2009 – 2011 as a collaboration practice among the County administration, the University of Jönköping and the companies present on the territory. Jönköping Climate Council’s work is divided into groups of actions, whereas members meet and discuss upon the decisions regarding their area of interest.

Västra Götaland Climate Council has been founded in 2017, together with the correlative strategy “Klimat 2030”, about the reduction of gas emissions of 80% by 2030. Västra Götaland represents a collaborative structure among the County administration, the Region and the companies present on the territory.

Jämtland Climate Council has been founded in 2014 as a space for dialogue among its different members. It holds an important accountability with the public since then.

Data from interviews

The interviews questions and transcripts can be found in the appendices. Interviews help in digging deeper into how collaborations are enacted within the climate councils institutions and how these collaborations are communicated.

“In collaborations, the best thing is to be open, sincere, tell your weaknesses and to trust the other” (interview with Andreas Olsson, administrator of Jönköping Climate Council). This phrase represents the strategy for collaborations put in action by the Climate Council in Jönköping. As mentioned earlier,

Jönköping’s Climate Council exists as a collaborative effort among the County administration and the local companies: “to cope with the change needed to reach our visions, we need a purposeful and productive cooperation between the County's actors” (Olsson). An important focus on the plurality of actors involved is clear.

To join the Climate Council in Jönköping, “the CC asks to the companies if they want to join, but always through someone, whenever a member says that there is a need, a matter to be solved, just then more people should be included” (Olsson). This system for inclusion goes hand in hand with efficiency and

accountability: “Members hold leading positions within their organizations and thus have a role to play in determining what is being decided in the Climate Council” (Olsson). The principal role is played by the Climate Council as a unique institution, that takes decisions and engage with stakeholders as a

25

comprehensive institution. “We do not really change members, but people can decide if they do not want to join anymore. We send to the members, monthly, questionnaires, to follow up with them” (Olsson). As regards leadership, every working group has its own leader and – at the meetings – the County Governor holds the leadership for the correct functioning of the encounters.

In an institution like the Climate Council, internal communication is key to exchange ideas and perspectives between the members. As stated by Andreas Olsson, regarding JKPG Climate Council: “The CC is based on dialogue and insight from different perspectives, from diverse requests: to follow up, to be transparent, to include, to be open minded and to be able to change is very important.”. The attendance to the meetings is good: “We send out the agenda one week before the meeting and we publish the web page about the meeting. We have to be transparent. Everybody, also outside the Climate Council, can see the process”. There are 4 meetings during the year, but every workgroup meets independently whenever it is needed. Accountability for the institution is gained through effective internal communication, as emerges from the interview: “it is more a word of mouth. Companies participating in the Climate Council have their own network so, if they see the benefits in participating in the Climate Council, they disseminate that to their network and, therefore, spread the word”.

As regards external communication, the strategy is divided into different tools. The website is an important tool to communicate to the public, then a series of events are organized, like the “Climate Week” and the “Climate Prize”. A specific team and budget for communication projects are present at Jönköping Climate Council. Jönköping Climate Council is not present on social media. The team creates a communication package that can be utilized from every member in order to convey a coherent and recognizable communication10.

Communication with external entities, for example other regions and associations, is said to not going so well: “Communication on a National level is not going so well. Fossil free Sweden has been to our meetings, but we did not actually collaborate with them” (Olsson).

“Ours is a very good example of collaboration between the Region and the County. We want to stress other Regions to do like us! Just seeing two big institutions as such collaborate in this way makes you realize our legitimacy” (Svante Sjöstedt, administrator of Västra Götaland Climate Council). This phrase summarizes the key aspect of the Climate Council in Västra Götaland, which is a full and connected collaboration between the Region and the County administration. A focal part of Västra Götaland Climate Council is represented, indeed, by the fact that they started as a collaborative body since the beginning. Lexical choices in the report highlight from the beginning the importance of the plurality of actors, summarized with the personal pronoun “we”: “We have an ambitious target” – “We need to invest in solutions” – “We need to speed things up”.