Bachelor’s Degree Project in Business Administration:

The psychology behind stockpiling behaviour during critical

situations

: A study of the change in consumer behaviour with special regards tothe phenomenon stockpiling among Swedish residents during the Covid-19

outbreak

Authors: Anna Hanser and David Bereilh

Tutor: Max Mikael Wilde Björling

Acknowledgements

Previous to commencing this research project, the researchers wish to formally acknowledge certain individuals who played crucial roles in the process and development of this bachelor thesis. First, the researchers would like to explicitly express gratitude to Professor Max Mikael Wilde Björling for his continuous support during the research process. Thanks to his patience, motivation, and enthusiasm, the experience of writing this thesis was a sincere delight. On top of this, his guidance and knowledge enabled this research paper to reach new levels. Furthermore, the researchers would like to extend a cordial thank you to the fellow members co-operating in the seminar groups, for their recommendations and constructive criticism. Your comments and highlights greatly improved the overall quality of this research. Lastly, the authors would like to thank the participants who allowed their lived experiences to be put under scrutiny. Their collaboration provided valuable qualitative data that could be used to draw precise insights on the topic of stockpiling.

For the aforementioned reasons, we thank you all! Anna & David

Bachelor’s Degree Project in Business Administration

Title: The psychology behind stockpiling behaviour during critical situations: A study of the

change in consumer behaviour with special regards to the phenomenon stockpiling among Swedish residents during the Covid-19 outbreak

Authors: Anna Hanser and David Bereilh Tutor: Max Mikael Wilde Björling Date: 2020-12-09

Key terms: Stockpiling, panic buying, pandemics, Covid-19, psychology, consumer

behaviour

Abstract

Background: The novel coronavirus (Covid-19) spread globally from its outbreak in China

in the beginning of 2020, causing numerous deaths and strained on the health care systems all over the world. Most countries gave answer to this pandemic by implementing national lockdowns, which often evoked panic among citizens and therefore lead to stockpiling or sometimes panic buying behaviours. However, Sweden decided to take another approach in handling the crisis and refrained from implementing a forced lockdown and mainly focused on the responsibility of individuals. Given the lack of research in the field of stockpiling behaviour among Swedish residents and the magnitude of difference in the “Swedish approach”, compared to other countries, this situation provides the perfect ground to research stockpiling behaviour in Sweden.

Purpose: This research aims to identify patterns and drivers within stockpiling behaviour

among Swedish residents during the Covid-19 outbreak.

Method: The paper is based on a qualitative study. A frame of reference to support findings

and provide important links to existing literature regarding the psychology behind consumer behaviour, in particular stockpiling during critical situations, has been presented. To create

in-depth insight into the reasonings behind stockpiling behaviour in Sweden during the Covid-19 outbreak, six semi-structured interviews have been conducted.

Conclusion: Two patterns, rational stockpiling and the absence of irrational stockpiling, along

with five drivers, namely, governmental restrictions and recommendations, fear from the disease or transmission, risk mitigation, convenience, and level of trust in the government, have been observed.

“Joseph in the Bible, Genesis 41: 46-57, kept a stockpile of grain for the future which he knew was going to be lean in the next few years. He knew the future, we don’t. Stockpiling is Biblical, who knew!!”

Table of contents

1. Introduction ... 8 1.1 Background ... 8 1.2 Problem ... 10 1.3 Purpose ... 11 1.4 Research Question ... 12 2 Frame of reference ... 132.1 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs ... 13

2.2 The consumer decision-making process ... 14

2.3 Psychology behind stockpiling ... 15

2.4 Other pandemic related behaviours ... 16

2.5 Changes in spending during a pandemic ... 17

3. Methodology ... 19 3.1 Overview ... 19 3.2 Research philosophy ... 19 3.3 Research Design ... 20 4. Data... 21 4.1 Collection... 21 4.2 Interview design ... 22 4.3 Sample selection ... 22 4.4 Data analysis ... 24 4.5 Ethical considerations ... 25 4.6 Trustworthiness... 25 4.7 Limitations ... 26 5. Empirical findings ... 27

5.1 General Perception of the coronavirus ... 27

5.2 Level of trust in the Swedish system and government ... 28

5.3 The effects of the coronavirus on daily life ... 33

5.4 Effects of the coronavirus on consumer behaviour ... 34

5.5 Stockpiling ... 37

6. Analysis ... 43

6.1 Overview ... 43

6.2 Observable patterns ... 43

6.2.1 Rational Stockpiling ... 43

6.2.2 Absence of Irrational Stockpiling ... 46

7. Conclusion ... 48

9. References ... 51

10. Appendices ... 55

Appendix A. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs ... 55

Appendix B. Consumer Decision-Making Process ... 55

Appendix C. Coding Table ... 56

1. Introduction

__________________________________________________________________________ The purpose of this chapter is to provide insights into the background of the field of study and the reason for why this topic deserves to be studied. Furthermore, the purpose of this study, together with the research question will be presented.

__________________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

The coronavirus (Covid-19) belongs to a family of coronaviruses (CoV) or SARS-CoV-2, which can cause different kinds of illnesses, starting from the common cold up to more severe diseases (World Health Organization, 2020a). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the majority of young and physically healthy people, that are infected with the virus, will experience mild to moderate respiratory illness with common symptoms such as cough, fever, difficulty breathing, runny nose, blocked nose, sore throat, headache, nausea, or muscle and joint pain and are likely to recover without special treatment. Older people or people dealing with medical issues, e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, and cancer, are more likely to be affected more heavily by the infection and are more endangered to develop serious diseases, such as severe forms of difficulties breathing and pneumonia (World Health Organization, 2020a). Nevertheless, the virus and its resulting illnesses, have caused numerous deaths and strain on the health care systems in the affected countries (Kamerlin & Kasson, 2020).

After the first reported case in Wuhan, China, in December of 2019, the virus started to spread globally. By March 2020, the European Region had been declared the epicentre of a pandemic (World Health Organization, 2020b). Due to the rapid spread in-and outside of China and the considerable consternation and panic it evoked among national, regional, and international public and political communities, boosted by news media and social media hype, the World Health Organization International Health Regulations Emergency Committee declared the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 a global emergency (Zumla & Niederman, 2020). The reason for the spread of the virus at such a high pace resulted from national and international travel and the numerous chains of transmission, caused by interpersonal contact (Zumla & Niederman, 2020). After the severe spread in Italy and later in Spain, it quickly became very clear that the gravity of the situation had been underestimated.

The most common response to stop further spread of the virus has been a lockdown of society in most countries throughout Europe, following the recommendations regarding isolation, social distancing, and mass testing from the WHO (Lindström, 2020). However, Sweden chose to follow another, less restrictive, strategy, which mainly focused on individual responsibility and aimed to protect senior and vulnerable citizens with the intent of avoiding a collapse of the national health care system by slowing down the spread (Lindström, 2020). The main goal was to limit social and economic disruptive interventions, which have been implemented in most other countries, while simultaneously trying to slow the spread and keep the health care system intact to provide an effective medical response (Kamerlin & Kasson, 2020).

Shortly after the implementation of national lockdowns in many countries and recommendations of the WHO, especially regarding isolation and the avoidance of interpersonal contact, people started buying necessities in large amounts, which would serve the household for at least two weeks, as a way to minimize visits to public places like supermarkets or pharmacies. This behaviour can be referred to as panic buying (Loxton et al., 2020). This socially undesirable herd behaviour is characterized by large quantities of daily necessities and medical supplies being purchased from markets, which often results in stockout situations. These situations leave individuals in more vulnerable groups (e.g., elderly or poor), who are in greater need of the products, limited from accessing them, which generates negative externalities in societies (Loxton et al., 2020). Also, from the retail perspective, panic buying causes further disruptions to supply chains. The sporadic surge in demand for consumer products, coupled with closures of routes or limits on traffic, poses challenges in areas like ordering, replenishment, and distribution. Consequently, this exacerbates stockout situations and often leads to a price increase of consumer products (Yuen, et al., 2020).

This type of behaviour is not uncommon as several kinds of irrational stockpiling, hoarding or panic buying have been witnessed during multiple major natural disasters and humanitarian crises throughout history (Yuen et al., 2020). During continental hurricanes in the US, such as Ike (2008), Irene (2011), Sandy (2012) and Arthur (2014), people stockpiled bottled water in all impacted areas (Chen et al., 2020). In the Asian area, rice and grains have been stocked during disasters to mitigate food supply instability. Compared to brand promotion-triggered stockpiling behaviour, disaster stockpiling contains more irrational factors and can, therefore, be treated as unconventional inventory accumulation action for reducing potential losses. Due to the lack of information and time for judging the situation during crisis times, stockpiling

behaviours become a contagious action influenced by fear of scarcity and misinformation spread over media channels, which leads to purchase acceleration (Chen et al., 2020). Stockpiling behaviour during crises can be driven by three fundamental psychological needs: autonomy, relatedness and competence (Chen et al., 2020). Autonomy relates to the sense of gaining back control out of the uncertainties during a crisis and having a choice. Relatedness creates a sense of unity and belonging to a “team”, which refers to stockpiling being a crowd rather than an individual action, which makes this kind of behaviour feel less inappropriate. Lastly, competence refers to the desire of individuals to control outcomes. In stockpiling behaviour, this psychological need can be fulfilled by making purchases that make the consumers feel smarter and more secure than others (Chen et al., 2020).

Moreover, trust is an essential predictor of risk perception (Biqiong, 2020). In more complete welfare states, such as Sweden and other Nordic Countries, the degree of social trust and well-being is significantly higher than in other countries. Therefore, people in Sweden tend to trust others more than in other parts of the world (Biqiong, 2020). However, in March 2020, even in Sweden, people started to panic hence resulting in the stockpiling of certain products, in particular, dry food and conservatives. At Coop Österplan in Örebro, Sweden, the management could see equal sales numbers of dry milk in only two days, than in the whole month of March in the previous year (Bruhn, 2020). Following these events, the Swedish government assured their citizens sufficient food provisions and requested a stop of panic buying, yet to prepare with dry foods and tinned goods, according to the recommendations of the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency and the National Food Agency (Regeringskansliet, 2020).

1.2 Problem

There have been several pandemics throughout history with varying degrees of infectiousness and mortality. Examples include the Spanish flu (1918-1920), the Zika virus pandemic (1952), HIV/AIDS (1981 to present), Russian flu (1989-1990), and the Swine flu (H1N1) (2009), among others. However, the natural rarity of pandemic situations in which stockpiling can be measured, makes it hard to research this consumer behaviour phenomenon. As a result, there is a gap of knowledge between periods in which the phenomenon of stockpiling simply could not be observed. Given that stockpiling is a niche area in consumer behaviour research, its understanding is limited and scarce (Yuen et al., 2020). The literature on stockpiling behaviours is largely scattered and lacks a focus on the irrationalities connected to this scarce consumer behaviour. It is therefore that the timing of this research could not be any more appropriate.

Amid the Covid-19 outbreak, this situation provides a suitable occasion to investigate this rare phenomenon.

Much of the research that has been done on stockpiling has been to construct frameworks that can be used to determine which policies to implement to restrict stockpiling and its possible effects, rather than focusing on identifying individual patterns within stockpiling and investigating the different reasonings behind them. Other research is pointed towards psychological factors that trigger stockpiling in different situations, however, they are generalized and not country specific. Moreover, much of the studies that have been conducted previously in the area of stockpiling, have collected data in ways that leave much to be desired. These kind studies base their analysis upon data gathered through online surveys or the analysis of bank statement information. Although this provides the opportunity to gather and analyse large data bases, it may leave critical factors that affect stockpiling out of frame.

As mentioned earlier, the magnitude of the difference in the “Swedish approach” compared to other countries in dealing with the spread of the virus allows for new insights to be discovered about the phenomenon of stockpiling, particularly in Sweden. As a country that refrained from putting their citizens in forceful lockdowns, their stockpiling behaviours may have been different than in other countries and this presents a unique opportunity for new ideas to be explored. The stockpiling patterns of Swedish residents can serve as a basis for comparison for similar countries during this particular pandemic, as a way to add to the lack of existing literature.

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this research paper is to deepen the knowledge around consumer behaviour during crises. It is focused on stockpiling behaviours among consumers in Sweden during the Covid-19 outbreak and is aimed to find behavioural patterns to further understand the reasoning behind them. In light of the existing knowledge gap with regards to stockpiling behaviours among Swedish residents, this paper aims to contribute to the closing of that gap. Using recent data to provide insightful research, minimize the recall effect and provide new ideas about Swedish residents and their buying decisions during the Covid-19 pandemic. Given the radical differences between most other countries and Sweden, in the approaches against the spread of the coronavirus, it is important to investigate if the Swedish approach has had any significant effects on their stockpiling behaviours.

Contrary to what has been done in previous research, due to time and resource limitations, this research paper does not aim to define an exact framework model in the efforts of addressing stockpiling behaviours. Instead, it is aimed to observe if there are any trends in the behaviour of consumers, particularly in Sweden when it comes to stockpiling during the Covid-19 outbreak. Despite the above mentioned, some observations will be highlighted with regards to possible reasoning that might help to understand stockpiling behaviours during critical situations. These observations will serve as a base for comparison for further research to come. The intention is to understand if the different measures taken by the Swedish government with regards to the Covid-19 outbreak have had any impact on the buying decisions of consumers. This way, behavioural categories may be found as a way to classify the different types of stockpiling behaviours in Sweden.

1.4 Research Question

To solve the above-mentioned research problem, the following research question has been formulated:

What are the drivers that lead to stockpiling behaviour and which patterns can be drawn from this behaviour with special regards to the Covid-19 outbreak in Sweden?

Due to the lack of research in the field of stockpiling behaviour during crises among residents in Sweden, the researchers aim to fill up a gap, to contribute to a better understanding of the differences in behavioural patterns and drivers to these behaviours as a way to give governments, retailers, and stakeholders a basis to better prepare for future crises and/or to create a basis for further research. The researchers define patterns as frequent actions or

inactions among the study participants. Besides, a driver should be viewed as internal or external motivation that leads to a particular action.

Regarding the current situation, stamped by the recent Covid-19 outbreak, the researchers regard it the perfect time to investigate such a phenomenon. While observing the unique approach to handle the situation that Sweden’s government follows, compared to the majority of other countries, the researchers are especially interested in investigating the behavioural patterns of Swedish residents within stockpiling.

2. Frame of reference

__________________________________________________________________________ This chapter provides theoretical background on the subject of this study, to provide general understanding and important links to the analysis in this study.

__________________________________________________________________________

2.1 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

To understand the reactions that people may have during a crisis, it is important to first understand the natural priorities that a human being must pursue in regular situations. This can be done by understanding Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a motivational theory in psychology, including a five-layer model of human needs, usually described as a hierarchy within a pyramid (McLeod, 2018). The lower needs in the hierarchy must be met before individuals can focus on higher needs. Starting from the bottom of the hierarchy, the needs are physiology, safety, love and belonging, self-esteem and self-realization (see appendix A) (McLeod, 2018). This five-stage model can be divided into deficiency needs and growth needs (McLeod, 2018). The first four levels are usually called "deficiency needs" (D

needs), while the highest level is called "growth of being needs" (B needs) (McLeod, 2018).

Deficiency needs are caused by scarcity, which is said to inspire motivation when people are unsatisfied. Similarly, the longer the duration of meeting such needs, the stronger their motivation will be (McLeod, 2018). For example, the longer a person has no food, the hungrier they become. Maslow (1943) initially pointed out that individuals must meet a lower-level need before they can continue to meet a higher level. However, he later clarified that satisfying needs is not an "all or nothing" phenomenon, and he admitted that his previous statement may give people the false impression that needs must be 100% met before the next need arises (McLeod, 2018). Meaning that if a lower-level need is partially met, people’s focus will habitually shift towards meeting the following need (McLeod, 2018). Conversely, growth needs do not stem from the lack of something, but from the desire for a person to grow. Once these growing demands are reasonably met, people can reach the highest level known as self-actualization (McLeod, 2018).

Although everyone is capable and eager to elevate the hierarchy to the level of self-actualization, unfortunately, failure to meet lower-level needs often disrupts this progress. Life experiences, including divorce and unemployment, may cause individuals to fluctuate between

classes. Therefore, not everyone will move through the hierarchy in a one-way manner but may move back and forth between different types of needs (McLeod, 2018).

2.2 The consumer decision-making process

To gain insight into the changes in the decision-making processes of consumers during critical times, the researchers feel the necessity to present a general model of the decision-making process itself. Kotler et al. (2020), developed a model, which describes five steps within the consumer decision-making process. (1) Need recognition, (2) information search, (3) evaluation of alternatives, (4) purchase decision, (5) post-purchase behaviour (see appendix B) (Kotler et. al, 2020). The model suggests that a consumer passes all of the five stages during every purchase. Regarding routine purchases, such as groceries and hygiene products, buyers often skip or reverse some of the stages. For example, a buyer who always buys the same brand of a daily necessity, would not look for information anymore, nor would the person evaluate possible alternatives. Therefore, in reality, when it comes to regularly purchased products, stages (2) and (3) are often being skipped (Kotler et. al, 2020). Following, the five stages of the consumer decision-making process are being explained more in-depth.

1. The buying process starts with the recognition of a need. This recognition can be triggered by internal stimuli when one of the normal needs (hunger, thirst, sex) rise to a level so that it becomes a driver. On the other hand, needs can also be triggered by external stimuli, such as advertisements or conversations with friends (Kotler et al., 2020).

2. The search for information depends greatly on consumer involvement in the buying process (Kotler et al., 2020). Consumer involvement can be high or low, which represents two opposite ends of a spectrum. Examples for products with high consumer involvement would be houses or cars, whereas examples for low consumer involvement represent toothpaste, yoghurt, milk, etc. (Laurent & Kapferer, 1984). If the consumer’s need is strong and a satisfactory product is near to hand, the search for information might be regarded as unnecessary for the buyer. The need for search of information, regarding the product, increases with higher involvement, which is more likely for bigger investments such as the purchase of houses, cars, etc. (Kotler et. al, 2020). 3. When it comes to regular purchases, consumer involvement is considered very low. As

the evaluation of alternatives, once again, highly depends on consumer involvement, it is likely to skip that stage when buying daily necessities. For example, a consumer regularly buying toothpaste from the same brand, would recognize the need and would forward straight to the purchase decision. This step is considered as more important to

the buyer if the intention is to make greater investments and/or buying new products, which the consumer has neither experience with nor a preferred brand (Kotler et. al, 2020).

4. During the purchase decision process, the consumer would most likely choose the product which he/she has the highest preference for. Nevertheless, two factors, attitudes of others and unexpected situational factors, which can be a turn in the economy for the worse, drop in prices by competitors, etc., can change the intended purchase decision. Therefore, preferences and purchase intentions do not always result in purchase decisions (Kotler et al., 2020).

5. The post-purchase-behaviour depends on the relationship between the consumer’s expectations and the product’s perceived performance. The larger the gap between expectations and performance, the greater the consumer’s dissatisfaction, which results in a bad relationship between the consumer and the brand. A profitable relationship with consumers is of great importance to the sellers, as it keeps and grows customers and leads to reaping their customer lifetime value. But once again, it is important to distinguish between high- and low-involvement products. For high-involvement products, if the product falls short of buyer expectations, complaints to the selling company and a substantial amount of negative word-of-mouth information in the social environment and on internet platforms could reflect negatively on the seller. Whereas regarding low-involvement products, such as yoghurt, low-sugar ketchup, or magazines, the consumers often don’t have the energy or motivation to take specific actions if they don’t meet their expectations (Kotler et al., 2020).

2.3 Psychology behind stockpiling

A pandemic is a situation in which people’s psychological responses are essential to the spread of emotional distress and social barriers that affect a wide range of conditions (Taylor, 2019). As a result, psychological factors play an important role in the way people respond to epidemics. The threat of losing loved ones, future uncertainty, and other potential sequelae affect the way people respond to such critical situations. Although many people seem to be able to cope well under threatening situations, others suffer from high levels of psychological distress and experience the worsening of pre-existing psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, or other clinical conditions (Yuen et al., 2020). It is therefore that psychological factors are of utter importance when managing broader societal problems involving pandemics (Taylor, 2019). Survival psychology suggests that after major events such as natural disasters and disease outbreaks, individuals may show behavioural changes, which may damage social

life and even threaten the health of individuals (Yuen et al., 2020). So much so that according to Atalan (2020), the lockdown measures adopted by many countries have increased stress and frustration. Both of which are psychological reactions related to mental health issues that can be caused by panic and uncertainty (Atalan, 2020).

The reason for accumulating food or any other goods may come from both rational and irrational aspects. It can be a holistic response that includes a mix of strategic, rational and emotional human responses (such as anxiety, panic, and fear) to perceived shortage threats (Wang & Na, 2020). From a rational point of view, consumers believe that the shopping journey provides an imminent threat of infection, while the supply of products may be damaged by the interruption of the supply chains. In fact, some governments (such as the United States) recommended households to store food, water and household necessities for two weeks according to the official website of the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA), when it was first recognized that public transmission could lead to two weeks of household quarantine after infection (Wang & Na, 2020). The most mentioned theme that helps explain stockpiling behaviours, is the personal perception of risk and assessment of the crisis. Previous research believes that irrational stockpiling is triggered by personal beliefs about the threat of events and the scarcity of products (Yuen et al., 2020). From an irrational point of view, some consumers may be influenced by peers, seeing how other people buy products in larger quantities, which may lead them to follow the so-called herd effect (Yuen et al., 2020). Other consumers may feel that they need to do something to gain a sense of control, and hoarding is an easy and relevant thing to meet their needs. Unreasonable hoarding is the result of panic buying, which is likely to cause food waste in the future and bring negative external effects to society (Wang & Na, 2020).

2.4 Other pandemic related behaviours

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to a series of behaviours such as avoiding crowded places and public transportation and engaging in emergency purchases (Usher et al., 2020). When an infectious disease breaks out, people are usually the most worried about getting infected (also called “disease-related concerns”), these concerns tend to compound and drastically affect the uncertainty of the severity of a threat (Usher et al., 2020). The emergence of abnormal behaviours has been observed during this and other pandemics. Behaviours related to panic that have led to empty shelves in stores, violence over daily necessities such as toilet paper; extreme shortages of basic items such as hand sanitizer and personal protective equipment and even attacks on health professionals (Malta et al., 2020). Recent literature conducted during the early

stages of the Covid-19 outbreak classify pandemic-related behaviours into three main categories: (1) protective behaviours, (2) preparedness behaviours, and (3) perverse behaviours (Usher et al., 2020).

Protective behaviours conform to public health rules, implemented to prevent the spread of diseases. These behaviours are further divided into strengthening personal hygiene practices (personal hygiene measures) and social distancing practices (social orientation measures). All of which are designed to prevent the spread of diseases (Usher et al., 2020). Moving on, preparedness behaviours operate as actions or anticipated actions that are designed to ensure that there are sufficient resources to implement an effective response to prevent the spread of diseases (Usher et al., 2020). Studies have identified several preparatory behaviours, including purchasing or intending to purchase materials to prepare for a larger pandemic, intent to delay or cancel air travel plans, and intent to reduce the use of public transportation. Also seeking active information, such as case distribution, number of infected individuals, infection control interventions, and preventive measures, are part of the so-called preparedness behaviours (Usher et al., 2020). Lastly, perverse behaviours are described as behaviours that deviate from what society considers "normal" or "ideal". Research has shown that some improper behaviours exhibit themselves during a pandemic. Behaviours such as avoiding going to the hospital, purchasing antiviral drugs, and the self-administration of antiviral drugs are all categorized as perverse behaviours that fall out of what is considered “normal” (Usher et al., 2020).

2.5 Changes in spending during a pandemic

As Covid-19 spreads around the world, households have faced drastic changes in many aspects of their lives. Government decrees closed a large number of businesses and in many cities in the world people were required to restrict travel abroad and contact with others following shelter orders (Hale et al., 2020). It is, therefore, that people have adapted their way of living and working in response to uncertainty about the future, they have also quickly changed how and where they spend their money (Baker et al., 2020).

After news spread about the impact of Covid-19 on a particular region, families changed their spending drastically. In general, spending has heavily increased as means to stock household goods and to anticipate shortage threats (Baker et al., 2020). Between February 26 and March 11, household spending increased by about 50% overall. As of March 27, grocery spending continued to grow, an increase of 7.5% compared to the beginning of the year (Baker et al., 2020). Research from the American National Bureau of Economic Research has also seen an

increase in credit card spending, which is consistent with households borrowing inventory (Baker et al., 2020). As the virus spreads, sharp declines have been observed in the number of restaurants, retail, air travel, and public transportation usage in mid to late March (Baker et al., 2020). Restaurant spending fell by about a third (Baker et al., 2020). The speed and timing of these spending fluctuations may vary from individual to individual, depending on their geographic location, as different countries and local governments have responded to disease outbreaks in varying ways and priorities (Baker et al., 2020). In countries and cities with shelter-in-place orders, total spending has fallen roughly twice as much as in places with less restrictive normative. However, in cities and countries that have shelter-in-place orders, grocery spending has tripled (Baker et al., 2020).

3. Methodology

__________________________________________________________________________ In this chapter, the methods used to study the given topics are going to be elaborated and reasonings about why these specific methods fit this study are going to be presented.

__________________________________________________________________________

3.1 Overview

The main goal of this research is to find insights and ideas that might help contribute to the understanding of stockpiling behaviours in Sweden during the Covid-19 outbreak. Given the severity of this new infectious disease, many countries have opted for a forceful lockdown of society (Lindström, 2020), and implemented different public health measures, following a suppressive approach to arrest transmission (Kamerlin & Kasson, 2020). Many countries, except Sweden. Sweden has taken an alternative approach by putting the responsibility on its citizens and appealing to a higher standard of trust in the people. By applying only very light mandates, such as the closing of high schools and universities and advising voluntary self-isolation of symptomatic people and senior people from the age of 70, Sweden has attracted much international attention and has become the most popular example of mitigation (Kamerlin & Kasson, 2020).

3.2 Research philosophy

Certain parameters identify the classification of this study. A research paradigm is a philosophical framework that guides how scientific research should be conducted (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Philosophy is “a set of our system of beliefs [stemming from] the study of the fundamental nature of knowledge, reality, and existence"(Collis & Hussey, 2014). Within scientific research, two main paradigms exist at opposite ends of a spectrum and will dictate the different approaches that a study can assume. On one hand, we have the positivist approach, which is based on the assumption that social reality is objective and external to the researcher (Collis & Hussey, 2014). On the other hand, we have the interpretivist approach, based on the assumption that social reality is subjective and socially constructed (Collis & Hussey, 2014 p. 44). There exist other research philosophies, however, they will not be included in this thesis due to their low level of relevance.

As it stands, we can say that this research paper falls into the research philosophy of interpretivism since it assumes that reality can be constructed by society and can be subject to interpretation. This philosophy seems to work particularly well with this study as there is little concrete information about the stockpiling behaviours of Swedish residents during the Covid-19 pandemic. However, there is literature on stockpiling occurring in other parts of the world. The assumption that the reality of stockpiling is external to the researchers' ability, can hinder the results of this study, providing misleading information that would not translate to other scenarios. Therefore, the interpretivist views of subjectivity seem to be better suited to the nature of this study. The interpretivist ideas served as a framework for this study and will therefore be reflected in the results of this thesis.

3.3 Research Design

This study is based on a mono method (only one research method has been applied), which is the qualitative research method. Qualitative research uses a naturalistic approach that attempts to understand phenomena in context-specific environments, meaning that researchers do not try to manipulate the “real-world” environment phenomena of interest (Golafshani, 2003). In a broad sense, qualitative research refers to any research that cannot be concluded through statistical procedures or other quantitative methods (Golafshani, 2003). The type of knowledge generated by qualitative analysis is different from that of quantitative, because one side argues from underlying philosophical nature of paradigms, conducting detailed interviews and other forms of qualitative data collection, while the other side focuses on the apparent compatibility of research methods (Golafshani, 2003).

In addition, methods such as interviews and observations dominate in the naturalistic (interpretative) paradigm, while in the positive paradigm it is complementary. Although some people claim that quantitative researchers try to divorce themselves from the research process as much as possible, qualitative researchers have begun to accept their participation and role in research (Golafshani, 2003). Using this kind of method provides the opportunity to observe and investigate consumers’ behaviour during a crisis and further separate drivers and patterns in a more analytical manner. With a qualitative approach, the researchers can dig deeper and understand the psychology behind consumers’ actions during uncertain times and as a result, provide in-depth analysis of the results.

4. Data

__________________________________________________________________________ The goal if this chapter is to provide insight on how data has been collected and analysed, how samples have been selected in this study, and how the research has been designed. Furthermore, limitations, ethical considerations, and trustworthiness are going to be presented.

__________________________________________________________________________

4.1 Collection

This study considers primary data along with supporting literature from other related studies as a means to acquire knowledge from several sources. Peer-reviewed articles, journals, and books were used to build knowledge around the basic information of stockpiling and in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted to gather first-hand data about the stockpiling behaviours of Swedish residents. The structure of these interviews will be discussed in the following section Interview Design. This information was later used to compare the different stockpiling behaviours that have been observed previously, with those that could be found during this investigation. This data served to facilitate the understanding of broader perspectives of the topic and provide insights into previous theory. The primary data gathered from semi-structured interviews were collected from a sample of six people. This was done to gather information relevant to the research problem (Hox & Boeije, 2005), in this case, stockpiling behaviours in Sweden during the Covid-19 outbreak. Although interviewing only six participants might seem like an arbitrary decision, this decision does not limit the credibility of this study. The information gathered through the six in-depth interviews appeared to reach maturity meaning that patterns could be observed and conclusions could be drawn (Griffee, 2005).

The supporting literature used in this paper was gathered through Primo, which is the online library at Jönköping University and Google Scholar, which is a widely known source for online research. These databases were used since they provide a wide variety of sources such as articles, journals, and entries, which are all applied in this study. These platforms proved to be useful for this study, as they provided a viable way of gathering various academic sources concerning several subjects. The majority of the sources used in this investigation are peer-reviewed, meaning that they have been reviewed by other intellectuals, therefore enhancing the trustworthiness of the sources (Nicholas, et al, 2015). This way, it was possible to get a

well-rounded understanding of the intricacies of stockpiling and the different factors that affect this consumer behaviour phenomenon.

4.2 Interview design

The interviews in this study are designed to explore the personal experiences of Swedish residents with regards to stockpiling. By using open-ended questions, subjects can elaborate on their different experiences. Through these interviews, the researchers aim to explore the possibility of encountering behavioural patterns with regards to their purchasing decisions during the Covid-19 outbreak. Due to negative portrayal in the media, especially social media, where people shame others for buying greater quantities than they might need and therefore putting the supply to serve everyone at risk (Preston, 2020), the word “stockpiling” will not be mentioned until the last question of the interview as a way to avoid compromising the results that may come from the negative connotations that the word may carry. Subjects may be inclined to deny their involvement with any stockpiling behaviour.

Regarding the interpretivist paradigm, this thesis is based on the interviewer’s aim to investigate attitudes, feelings, data on understandings, what people remember doing, and things that people have in common. The design is laid out in the form of semi-structured questions, which means that the interviewers ask open questions that cannot simply be answered with “yes” or “no” and are designed in a way that allows elaboration and engagement, thinking, and reflecting of the interviewee. Furthermore, the prepared questions are encouraging the participant to talk about the main topics of interest and gives the interviewer the possibility to develop further questions throughout the course of the interview (probes). The order of questions is, therefore, flexible and gives room to skip certain questions, where the interviewee may have already provided the relevant information by answering another question (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The entire question guide can be found in the appendix.

4.3 Sample selection

Convenience sampling (also known as availability sampling) is a common type of non-probability sampling method where the main criterion is convenience for the researchers (Farrokhi & Mahmoudi-Hamidabad, 2012). It consists of choosing participants based on convenient availability with few regards for other factors. In business studies, such as this one, this type of sampling method can be used to gather primary data on a particular subject, such as the perspective or experience about an observed phenomenon. Since this paper aims to investigate the stockpiling behaviours of Swedish residents, the participants must have been

living in Sweden before and after the Covid-19 outbreak as a way to compare their consumer behaviours pre- and post-the viral outbreak. This also avoids compromising the results of the study by refraining from adding unaccounted variables like a recent change of residence to Sweden. The participants in this study were obtained conveniently, using direct contact with individuals in close proximity to the researchers, therefore, complying with the parameters of convenience sampling. This sampling method was chosen to provide conveniently selected participants ranging from several different demographic categories for semi-structured interviews. These demographic categories will be used to further specify any potential patterns of stockpiling that might adhere to specific demographic characteristics. The researchers focused on four main criteria while choosing their interview participants:

• Having both, male and female participants

• Having people born in different generations

• Having only Swedish residents

• Having participants with different residencies

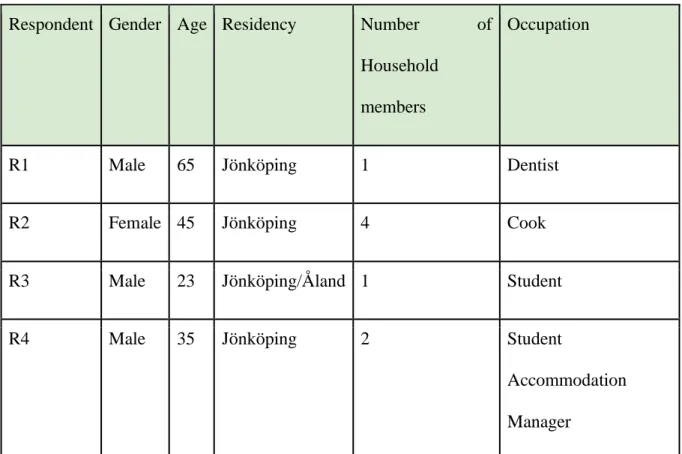

The following table shows all six respondents that meet all four criteria and were willing to participate in the interviews. If any reference from participants is being quoted throughout the paper, they will be referred to by the respondent's number, for example, “R1” (see table 1).

Table 1. Interview participants

Respondent Gender Age Residency Number of Household

members

Occupation

R1 Male 65 Jönköping 1 Dentist

R2 Female 45 Jönköping 4 Cook

R3 Male 23 Jönköping/Åland 1 Student

R4 Male 35 Jönköping 2 Student

Accommodation Manager

R5 Female 21 Falköping 3 Student

R6 Male 19 Stockholm 4 Student

Source: This table has been designed by the authors of this thesis.

4.4 Data analysis

According to Miles and Huberman, the analysis of qualitative data is based on three main steps: (1) reduction of data, (2) displaying the data, and (3) drawing conclusions and verifying the validity of those conclusions (Collis & Hussey, 2014). However, Neale (2016) claims that in practice the process can be simplified into only two steps: (1) transcription of data and (2) interpretation of data (Neale, 2016).

All semi-structured interviews were audio or video recorded with consent from the participants. Later on, the audio was transcribed, followed by coding. According to Collis & Hussey (2014), coding allows the researchers to group data into categories that share common characteristics (Collis & Hussey, 2014). A code is “a word or short phrase that symbolically assigns a summative, salient, essence-capturing, and/or evocative attribute for a portion of language-based or visual data” (Saldana, 2013). The researchers have generated the codes in a way they provide links between the collected data and the researchers’ analysis and interpretation of the data. Table 2 shows an example of the code words that have been used to categorize the answers from the respondents during the data analysis. The entire Table 2 (Appendix C) and question guide (Appendix D), which is connected to Table 2, can be found in the appendix.

Table 2. Example Coding

Question Code Word 1 Code Word 2 Code Word 3

Q4 positive attitude negative attitude indifferent Q5 trust significantly trust with some reservations no trust at all subQ1 follow rigorously follow to a certain extent don’t follow at all Source: This table has been designed by the authors of this thesis.

While going through the material multiple times, similar phrases, patterns, themes, relationships, sequences, differences between subgroups, etc. have been identified purely based on the patterns found in the data. Lastly, a small set of generalizations, that cover the consistencies found in the data, has gradually been developed and further linked to a formalized body of knowledge in the form of constructs (concepts or ideas) or theories (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

4.5 Ethical considerations

During the process of research, ethical standards play an important role. The researchers assured to consider the four ethical principles, mentioned by Tracy (2013), which are (1) do not harm, (2) avoid deception, (3) informed consent, and lastly, (4) privacy and confidentiality (Tracy, 2013). It is following this premise, that not one of the participants in this study has been harmed. Prior to the interview, all of them have been asked for consent to record the conversation, have been offered anonymity, have been respected in their privacy, and have been assured confidentiality.

Moreover, all participants of this study have been informed about the topic of the study before their interview and have been informed about confidentiality. Their participation was completely voluntary, nothing was offered in return for their participation which guaranteed that they were purely interested in adding data to this study and not driven by other external factors.

4.6 Trustworthiness

The trustworthiness of a study represents the validity of the results and should therefore be considered of high importance (Conelly, 2016). It is important for the readers to know that the results are based on impartial data analysis and not on researchers’ opinions (Shenton, 2004). The research protocols are to aid the transparency and the credibility of the study by avoiding any compromising practices (Connelly, 2016).

In this study, several methods have been used to collect, categorize, and analyse the data to provide trustworthy results. Semi-structured interviews were used to gather in-depth information about the subjects’ experiences within stockpiling. The participants of these interviews were all living in Sweden before and after the Covid-19 outbreak as a way to obtain credible insights of people who were within the designated area of research (in this case Sweden). On top of this, the researchers gave importance to the demographic categories of these

participants as a way to explore different demographic categories, therefore amplifying the scope of the study.

Lastly, a framework was chosen to analyse the data in an organized manner by using codes to assign categories to the different patterns of stockpiling found during this study. All of the above-mentioned factors add to the trustworthiness of this research paper. It is therefore that the results of this study are to be considered credible as they can be replicated in similar circumstances.

4.7 Limitations

Although this research can be considered credible in its majority, it includes certain limitations that are tied to circumstantial factors that slip out of the researchers’ hands. For example, there were time and resource limitations that resulted in a smaller number of interviews conducted. This could have had an effect on the findings of this study as a small sample might not capture all the intricacies of the phenomenon of stockpiling. Moreover, the natural resistance of participants to agree to participate in interviews due to social distancing practices may have contributed to a smaller sample in this study.

Lastly, the sampling method used in this study (convenience sampling) could have had an impact on the results, as the participants were individuals close to the researchers. It is possible that having another sampling strategy might have yielded different results. The limitations in this research paper do not discredit the results of this study. However, they should be taken into consideration for further research as they can be accountable for variances when replicating this study.

5. Empirical findings

__________________________________________________________________________ In this chapter, the empirical findings of the six conducted semi-structured interviews in this study will be presented. All of the respondents are Swedish residents, located in different Swedish cities, are both male and female, and differ in age (see table 1). Based on the interview guide (see appendix D), the results are categorized in general perception of the corona virus, level of trust in the Swedish system and government, effects of the coronavirus on daily life, effects of the coronavirus on consumer behaviour, and stockpiling.

__________________________________________________________________________

5.1 General Perception of the coronavirus

To gain insight into the consumer behaviour of individuals during the coronavirus crisis, the researchers started the interviews by asking the participants about their general perception of the outbreak of the coronavirus. None of the respondents said that they were scared of being infected with the virus. Most of the time, if the participants were younger than 40, they argued their answer with the fact that they are young and unlikely to get serious health conditions if they happened to get infected.

R3: “I don’t worry about the coronavirus because I’m young.”

R4: “I am taking it seriously, but I also understand that I am not in a risk group. I am scared for other people but not myself.”

R5: “ I’m more scared to transmit the virus to other people than I am scared to get sick.”

Another reason for not being scared of the virus is that participants have been previously infected and experienced a mild course of the disease and therefore considered themselves immune to the disease.

R1: “I’m not scared of the virus. I was actually infected with corona in April, so I was scared only during my sickness but not anymore.”

However, the majority of the respondents take the situation very seriously claiming that it is important to be cautious and act with common sense. The participants understand that it is just as important to protect others as it is to protect oneself. Yet, it is smart to stay calm to avoid panicking in society.

R2: “One needs to be cautious but not panicky. Acting hysterically can affect other aspects around corona. One needs to have common sense.”

R5: “I am very concerned about my family, especially for my brother who is in the risk group. I don’t want to infect them.“

To gain a better understanding of the drivers behind participants’ consumer behaviour and actions, the researchers were interested in knowing if any of the respondents had already experienced a similar situation, such as another pandemic, natural disaster, or even war. Five out of six participants have never experienced a similar situation and are therefore confronted with unknown feelings, uncertainty, and/or fear. One respondent claimed to remember the “H1N1” flu in 2009, which did not, according to the respondent, draw that much public attention and did not restrict daily life as much as this pandemic does.

5.2 Level of trust in the Swedish system and government

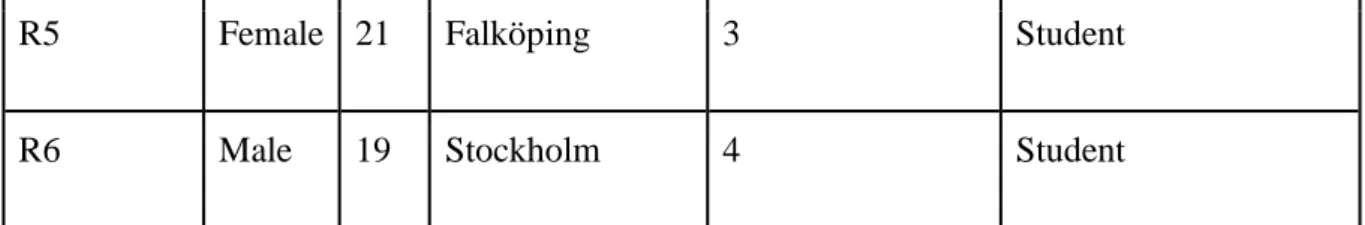

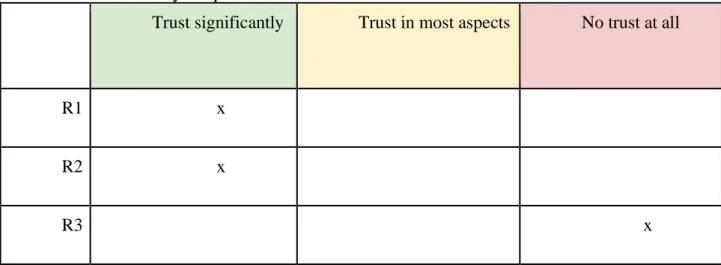

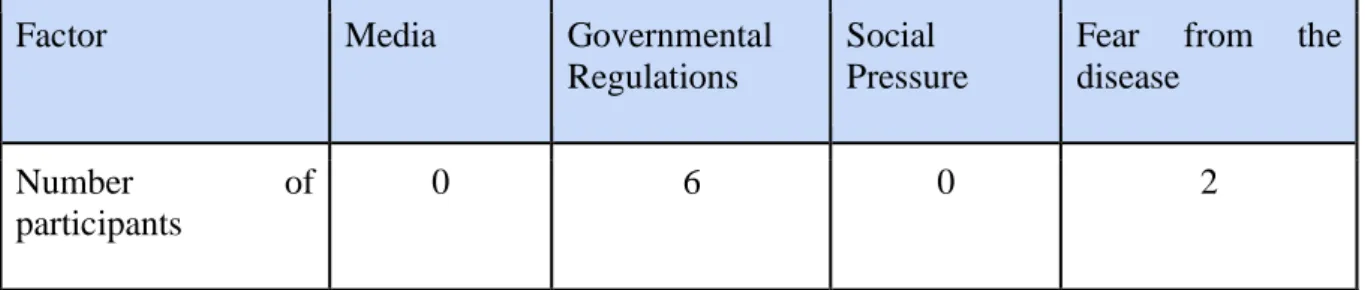

The data in this study, collected through semi-structured interviews highlights the high level of trust that Swedish residents have in their system. Five out of six respondents of this study claimed that they generally trust the Swedish system and the government (see Table 3).

Table 3. Level of trust by Respondents

Trust significantly Trust in most aspects No trust at all

R1 x

R2 x

R4 x

R5 x

R6 x

Source: Designed by the authors of this thesis.

What we can see from the results in table 3 is that the older generation tends to trust the system and the government to a great extent, whereas the younger generation trusts the government either with some reservations or not at all. The reasons named by the participants, that cause a reserved trust in the system and the government, are mostly actions in the past and/or present that are not being supported by the participants.

R1: “Yes, I trust the government very much. I would follow their recommendations because I think that the people making decisions are competent and educated”

R2: “I trust the government because we have scientists in charge instead of politicians.”

R4: “Yes. Not always but in this case. I am watching a documentary about Estonia, where a boat sank in 1985 where the Swedish government put a lock on the boat and a couple of hundred people died because they couldn’t escape. So, I am really disappointed how our government handled this, therefore I lost trust in them due to the fact that it wasn’t their first priority to save people when they could. The case is still open today and nobody wants to take responsibility for it. Nevertheless, when it comes to handling the pandemic, I totally trust them because we are probably the only country, where not the politicians but the scientists and people from the health care department, who are educated in this area, make the decisions. If you look at the US, you see that this whole crisis became a political show and part of the elections between Trump and Biden and no competent decisions are being made there. Therefore, their situation is also really bad. It’s all publicity there.”

R5: “I am pretty sure that they are good at making decisions as the country is still running. In this case, though, I think the government worked a bit backwards in this case because they didn’t take it seriously in the beginning and now that the second wave hits, they are waking up

and realize that we need restrictions too. So, I think we are a little bit behind, compared to other countries.”

R6: “I Kind of trust them. They are doing stuff their own way, sometimes right but sometimes very wrong. They only work in one direction (drive people in the direction they want them to). Also, a lot of money (tax money) does not end up at the places and people who need it. It is not allocated right.”

Furthermore, it has been mentioned that the decisions by the government are rather taken for publicity or ideological purposes than serving the interests or health and safety of the population.

R6: “The decisions are not only scientific based but more ideological. The government only promotes positive things that support their motives and ideals and totally ignores negative factors that influence their decisions.”

R4: “At the beginning of the outbreak, I think that the government did the right things but now I think that it’s more about publicity than the genuine care about the people.”

Nevertheless, when it comes to how Sweden is handling the coronavirus pandemic in a different way than the rest of the affected countries, which has been elaborated in the introduction chapter, all six respondents think that the people in charge of making decisions are competent and that they trust their actions. A very frequent answer was that Sweden is one of the few countries, where scientists are in charge of making decisions instead of politicians. The participants believe that the people in charge are very well educated and competent in this field. This could also be the reason that five out of six participants claimed that they try to follow the recommendations, implemented by the government, as much as possible.

R1: “Yes, I trust the government very much. I would follow their recommendations because I think that the people making decisions are competent and educated.”

R4: “When it comes to handling the pandemic, I totally trust them because we are probably the only country, where not the politicians but the scientists and people from the health care department, who are educated in this area, make the decisions.”

R2: “I trust the government because we have scientists in charge instead of politicians and I trust the scientists more than the politicians.”

Half of the respondents in this study are very supportive of the way Sweden is handling the situation. Which means, no strict limitations, to trust in the responsibility of the Swedish population, no implementation of a national lockdown, trying to keep the economy intact, and to simply keep distance and self-isolate if one suffers from any kind of symptoms that are related to the Covid-19 disease. Where on the other hand, the other 50% of the participants, which represents once again the younger generation, wishes that the government would undertake more actions and would act more responsibly to assure the health and safety of Swedish residents. A frequently given answer was that participants would have wanted better recommendations from the beginning of the outbreak, such as the recommendations of face masks (which have been advised against to by the government up to this day) and that the Swedish government would have taken the situation more seriously from the beginning, to create a more cautious and serious mindset for the Swedish society. Also, the hesitation of implementing some kind of recommendations and/or restrictions and the long period of time that it took for the government to discuss and elaborate their decisions, has been taken negatively by the respondents.

R3: “In the beginning, they went with a reckless solution. They didn’t take it seriously.”

R5: “It is frustrating because I think that we wouldn’t have that high numbers we are having right now if people would wear face masks and actually keep a social distance. I wish that the government would have taken it more serious from the beginning and would have handled it the way it’s supposed to be handled because then our society wouldn’t have gotten this laid-back mindset and would have taken the situation more seriously.”

R6: “Sweden has been the most hesitant country in the world when it comes to taking measurements against the pandemic. I think that the government should have acted earlier, at the beginning of the pandemic. Face masks have not even been promoted or suggested by the government. Recommendations would have a bigger impact if they would have been implemented earlier.”

Nevertheless, all respondents agree with the decision of the government to not implementing a national lockdown, as most other countries did. The participants see the economic aspects just as important as the health aspects and enjoy the unrestricted freedom they are getting assured with by the system and constitution in their country. It has also been mentioned that lockdowns do not necessarily contribute to a long-run reduction in infections, as it could be witnessed in other lockdown-countries, that suddenly regained freedom after a national lockdown, also referred to as “lockdown cravings” by the respondents, boosted the number of infections even higher, compared to before the implementation of lockdowns.

R1: “We are a very small country so we can get away with this way of handling the situation. We can get away with not having a lockdown.”

R2: “I think that Sweden is handling the situation amazingly. My husband and daughter are stuck in a lockdown in Canada with a bunch of restrictions and can’t even leave the house most of the time. In my opinion, a lockdown is a way of overkilling the situation, which brings a lot of side effects with it, for example, kids staying home from school, people losing their jobs, etc.” R4: “I don’t think that a lockdown in Sweden would work as you can see in other countries that had lockdowns, like Italy or Spain, that the second wave hits them just as hard. So, from my point of view, I think we did the right thing. I believe that the government in Sweden is doing the best they can and from what I can see, nobody did the right decision, it’s just a different decision and the outcome is the same everywhere. Countries, where people wear masks, have just as high numbers as we have. I am confident that the government did the best they could to ensure our health and I think that economics is just as important. In the long term, not as many people lost their jobs because of the crisis and many people saved money during this time so I think once this is over, there will be an economic boom.”

R5: “I am kind of happy that we don’t have such strict measurements because then I can still go out and live an almost normal life even during the crisis.”

R6: “Since people have been scared, everyone acted out of their own responsibility. Also, when you look at other countries, where people regained the feeling of freedom after hard lockdowns and went crazy, we Swedes didn’t have such “lockdown craves”, that I believe, is also a reason why our numbers stayed quite constant.”

5.3 The effects of the coronavirus on daily life

Due to several restrictions implemented by the government, many people had to adjust to multiple new rules and changes in their daily lives such as change of workplace, working remotely from home, facing different opening hours of stores and pharmacies, avoiding social contact, etc. During our research process the researchers found out that depending on occupation and lifestyle, participants experienced different kinds of effects on their daily lives caused by the pandemic. Half of the respondents claimed to have experienced mild effects on their daily lives. These could be a change from working/studying at the workplace/university to working/studying remotely from home, not being able to visit practical classes at university, grocery shopping and visits at pharmacies being more time-consuming due to keeping distance, longer waiting hours in front of stores and pharmacies because of governmental regulations that only allow a certain amount of people in at once, reduction of personal contact with relatives and acquaintances, and avoidance of public places in general.

R4: “Hasn’t affected me too much, apart from not going to restaurants anymore, to avoid places with many people. I’m meeting people in smaller groups though but as I am awaiting a baby, I am trying to avoid social contacts.“

R5: “It has affected my education in terms of not being allowed to go to university any longer and in my program (nursing program) we have some very practical courses and therefore we need to be on campus.“

R6: “Yes, I don’t really go outside too much anymore. A lot of stores have closed now, and my habit was to just go to the mall and look around for things but now I only go to a store if I really need something specific. My classes have changed to distance learning though, so instead of getting work done at the campus, I am sitting at home in front of my computer and books all day. I have learned to deal with this new way of studying but I miss going to school, mostly because I miss going outside.”

Some of the participants have been affected more heavily by, for example, losing their jobs or by having major or slight decreases in their salary. On the other hand, family members of the respondents who work in industries such as health care could see a salary increase. Thus, workers in the healthcare system were impacted in their daily lives just as much, as they have

to work a remarkable amount of extra hours and are, additionally, not able to take sick days or days off from work, during the duration of this pandemic.

R1: “We had a decrease in the number of patients in the Spring (which resulted in less income) but now it’s more normalized. However, now since the infections are going up again maybe it will decrease again. We treat elder patients, and they don’t dare to come to their appointments out of fear of getting infected.”

R2: “I lost my job because of the crisis, so my income decreased significantly.”

R3: “It's super hard to get jobs now. It feels like getting an interview is really hard because people don’t want to meet.”

R5: “My mom works in healthcare, so things have changed for her because she is not allowed to take days off (holidays) at this time and she has to work a lot of extra shifts. She has even been promised to be rewarded for her extra services.”

R6: “My father works in the home office now and my mom works in the healthcare system, so their jobs are secured, and they can still work the same amount than before or even more. My mother just can’t take sick days anymore and they can make her work more than what she is getting paid for.”

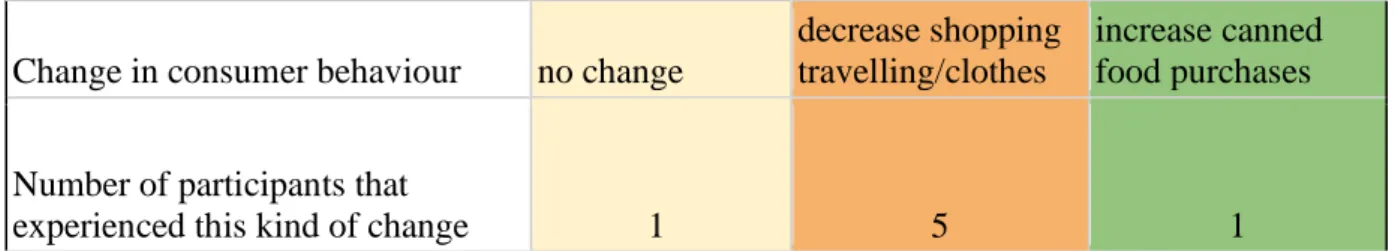

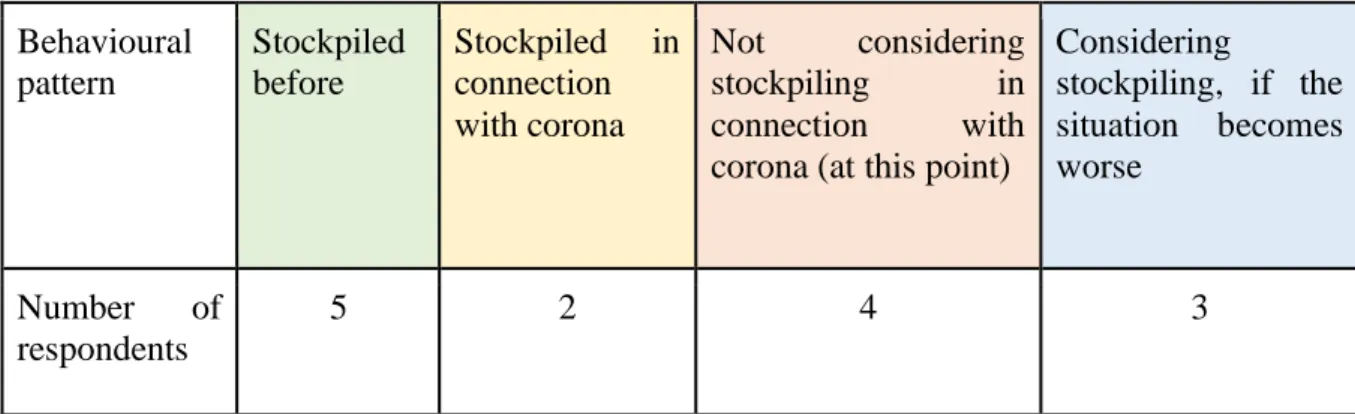

5.4 Effects of the coronavirus on consumer behaviour

When asking the participants about changes in their consumer behaviour, influenced by the change in lifestyle or recommendations/restrictions from the government, a clear tendency towards a decrease in purchases of travel tickets and leisure shopping could be discovered. In Table 4 below, the most frequently claimed changes in consumer behaviour due to the outbreak of the coronavirus have been listed and the numbers of participants that have mentioned such changes have been allocated.