MASTER DEGREE PROJECT

THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration

NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Int. Logistics & Supply Chain Management AUTHOR: Caspar Richard Krol, Wiebren Prins

JÖNKÖPING May 2020

Cooperation between

established corporate

companies and start-ups

Gaining innovation power from start-ups’

digital-driven logistics innovation

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Cooperation between established corporate companies and start-ups - Gaining innovation power from start-ups’ digital-driven logistics innovation Authors: Caspar Richard Krol and Wiebren Prins

Tutor: Tommaso Minola Date: 2020-05-17 Word count: 24.616 words

Key terms: Digital-driven logistics innovation, cooperation, innovation power, start-ups

Abstract

Innovation power is essential for long-term survival in the competitive environment of a corporate and can often only be increased through cooperation. It is therefore crucial for management and researchers to know the most important factors influencing the increase of this power and the effects of the form of cooperation on it. Especially in the field of digitization, many corporates still lack experience, especially in how to cooperate with start-up companies to achieve effective digital innovations. This thesis identifies digital-driven logistics innovation used by corporates and their most important impact factors as well as forms of cooperation between the start-ups who invented those and corporates who are using them for improvement of their own innovation power. Therefore, qualitative interviews were conducted at management level, with large established manufacturing companies and logistics service providers (LSPs) from Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Great Britain, and Switzerland. The empirical findings show that the influencing variables application area and purpose, logistics activity, size, industry, digital experience, and cooperation experience are the most important factors. They also reveal that within the context of digital-driven logistics innovation, the cooperation between start-ups and the applied form of cooperation could influence the innovation output. The type of innovation is influencing the innovation power and slightly influences the type of cooperation. The cooperation form influences the innovation output as well. However, different results may be obtained for individual cases and companies, especially in the comparison between manufacturing companies and LSPs. Managers of established corporate companies can use these results to identify the best possible form of cooperation with start-ups for future decisions on cooperation to achieve digital-driven logistics innovation.

Table of Contents

... 1

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.1.1 Latest revolution within logistics ... 2

1.2 Problem discussion ... 4

1.3 Scope and delimitation ... 5

1.4 Purpose and Research question ... 6

1.5 Outline ... 8

2.

Literature Review ... 9

2.1 Innovation in the field of logistics ... 9

2.1.1 Forcing innovation in logistics ... 9

2.1.2 Digital-driven innovation ... 10

2.1.3 Technological, process, service, and business model innovation perspective... 12

2.1.4 Digital-driven logistics innovation ... 14

2.1.5 Cooperation as a lever for innovation ... 15

2.2 Cooperation with start-ups to thrive innovation ... 16

2.2.1 Challenges of corporates being innovative ... 16

2.2.2 Innovation potentials in cooperation with start-ups ... 18

2.2.3 Characteristics of corporates and start-ups ... 19

2.2.4 Forms and impact factors of cooperation ... 20

2.2.5 Measurability of unspecified impact factors through indicators ... 26

2.3 Literature gap statement ... 29

3.

Research methodology ... 30

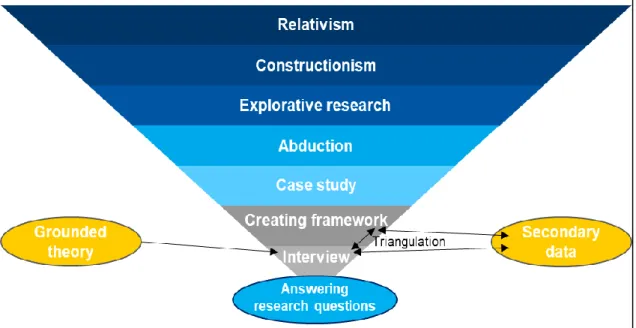

3.1 Research philosophy ... 30

3.2 Research approach ... 31

3.3 Research design ... 32

3.3.1 Case study design ... 33

3.3.2 Data collection ... 34

3.3.3 Data analysis ... 34

3.4 Research quality ... 36

3.5 Overview of the research methodology ... 38

4.

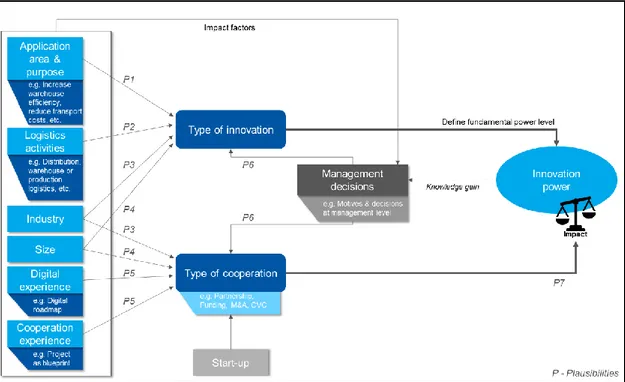

Conceptual framework ... 39

5.

Empirical findings ... 42

5.1 Evaluation of digital-driven logistics innovation and their innovation power ... 42

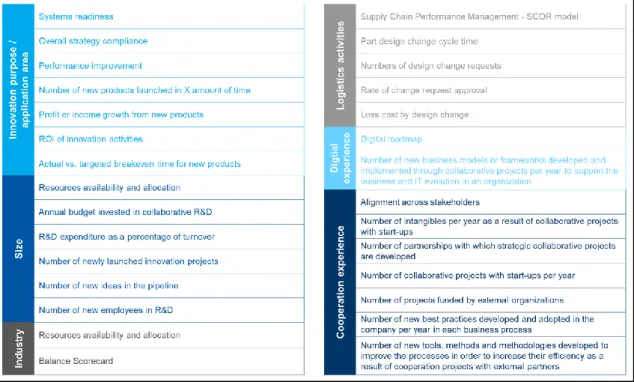

5.2 Evaluation of corporate characteristics ... 45

5.2.1 Industry and activity level ... 45

5.2.2 Company size ... 47

5.2.3 Experience level ... 48

5.3 Evaluation of the effective relationship of cooperation form and innovation power ... 49

6.

Empirical analysis ... 52

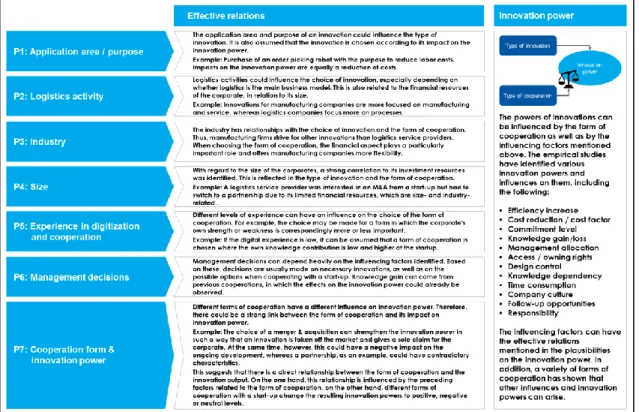

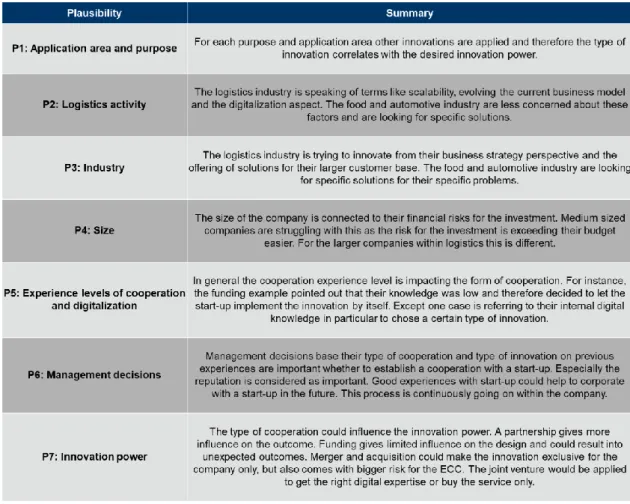

6.1.2 Logistics activity ... 53 6.1.3 Size ... 53 6.1.4 Industry ... 54 6.1.5 Cooperation experience ... 54 6.1.6 Digital experience ... 55 6.1.7 Innovation power ... 56

6.1.8 Management decisions for considering other cooperation forms ... 57

6.2 Empirical model ... 57

6.2.1 Impact factors ... 58

6.2.2 Start-up ... 59

6.2.3 Management decisions ... 59

6.2.4 Plausibilities of the effective relations ... 59

7.

Discussion ... 64

8.

Conclusion ... 67

8.1 Research questions and purpose ... 67

8.2 Implications ... 69

8.2.1 Theoretical implications ... 69

8.2.2 Practical implications ... 69

8.3 Limitations and further research ... 69

9.

Reference list ... 71

Figures

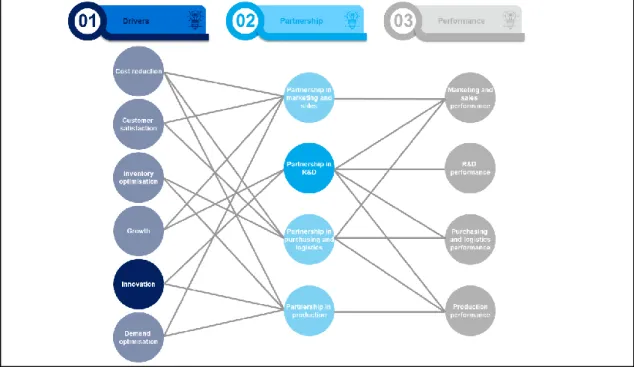

Figure 1: Partnership drivers and their related performances ...

(own depiction based on Rezaei et al., 2018) ... 1

Figure 2: Research scope ... 5

Figure 3: Model for the research methodology ... 38

Figure 4: Conceptual framework of empirical analysis ... 39

Figure 5: Impact factors and their indicators ... 45

Figure 6: Model based on empiricism of the effective relations ... between type of cooperation and innovation ... and the innovation power ... 58

Figure 7: Visualization of the findings from the empirical research ... 63

Figure 8: Summary of the plausibilites from the empirical research ... 85

Figure 9: Overview of the plausibilites from the empirical research ... with quotes from the conducted interviews ... 86

1.

Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The first chapter is discussing the background of the thesis which is the cooperation between corporates and start-ups on a digital context to strive towards effective innovation cooperation. Following, the underlying problem is brought up leading up to the scope of the thesis and their delimitations. Lastly, the purpose and research questions are examined.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

Many revolutions have been ongoing within the field of logistics and supply chain (Chen & Paulraj, 2004). Starting from the quality revolution followed by integrated logistics and industrial markets and networks. These networks arise from international cooperation, vertical disintegration resulting into firms linked within the supply chain. Revolutions inspiring and requiring chance to gain competitive advantage, reducing costs of operation, improving customer satisfaction, improving inventory, growth, innovation, and demand optimisation (Mathauer & Hofmann, 2019; Rezaei et al., 2018) within the logistics sector.

Figure 1: Partnership drivers and their related performances (own depiction based on Rezaei et al., 2018)

Concerning the network within logistics, cooperation is needed on different levels. For instance, the horizontal cooperation is a form of cooperation between companies which are providing similar services within the market (Cruijssen et al., 2007) where vertical cooperation is executed between the supplier, manufacturer, and customer.

Rezaei et al. (2018) are clarifying that effective supply chain management should integrate all functions as suppliers and buyers do not only exchange material assets, but financial assets, technological assets, information, and knowledge. Therefore, business functions and functional areas as marketing and research and development (R&D) are calling for specific partnerships. Benefits of collaboration and cooperation, considering these so-called business functions, could be classified as customer-related benefits, productivity-related benefits, and innovation-related benefits. Innovation goes beyond the technological breakthroughs or products alone and can occur within services, processes, or any social system (Flint et al., 2005). Multiple innovative technologies combined and applied creates digitization (Mathauer & Hofmann, 2019) and digital manufacturing (Holmström & Partanen, 2014) resulting into lower complexity through simpler and more effective solutions.

1.1.1 Latest revolution within logistics

The latest revolution within the logistics industry is characterized by digitization of markets, industries, and companies (Jung, 2018). Digital technologies radically changed strategies resulting into new business models and new operational capabilities and perspectives (Mola et al., 2017). Connected to high investment costs of such digital technology firms struggling to adopt these technologies as a lack of knowledge and expertise in this area is missing. Consequently, firms chose not to develop these technologies in house. High tech small and medium business sized companies (SME’s) could possibly contribute to this process of being innovative (Rezaei et al., 2018) resulting into digitization, which is the usage of various technologies (Mathauer & Hofmann, 2019) as for instance the big data analytics, industry 4.0, additive manufacturing, e-commerce and advanced tracking and tracing technologies (Ivanov et al., 2019; Mola et al., 2017).

Corporates need understanding of digital innovations within logistics because of customer service levels improvement reaching beyond level of transportation including order processing and additional IT-services (Mathauer & Hofmann, 2019). Secondly, the

competitive pressure is increasing related to global market working and therefore the need to require new sources of innovation or improve existing solutions to gain competitive advantage over competitors (Lin & Lin, 2014). Implementing these digital innovations result into changed firms’ operations, logistical activities, communication and marketing strategies, relationships with suppliers and customers, and the way in which customers are served (Mola et al., 2017). Thus, they are influencing the processes within a company. Finally, digitization is resulting into shorter technology innovation cycles and new competitors and business models, such as marketplace platform providers (Hofmann & Osterwalder, 2017).

Some articles discuss the relationship of cooperation between SME’s as possibly negative (Arend & Wisner, 2005; Rezaei et al., 2018) on the supply chain partnership and overall firm performance level resulting from short-term vision of strategy, even though it remains unclarified from an empirical point of view. On the other side SME’s could gain advantage from core competencies perspective when cooperating with large corporations (Cassetta et al., 2019). SME’s could also be categorized as the logistics service providers (LSP), as many LSP’s are family owned and therefore smaller companies (Wagner & Franklin, 2008).

One particular form of SME’s are start-ups. Those firms can be classified as companies younger than ten years, providing highly innovative technologies or business models, are recognized by their activities in the early stages of operations (Kollmann et al., 2017; Nurcahyo, 2018) and are characterized by entering existing markets or new markets with innovative services and products and therefore impacting corporates in different ways as business transformation, growth and performance (Ben Arfi & Hikkerova, 2019). The larger corporations are less productive in R&D (Shan et al., 1994) where other sources implying the statement of larger corporations supporting innovation within smaller firms. The need for innovation is there, still logistics companies experience problems at being innovate (Wagner & Franklin, 2008) where Wagner (2008) is proposing the toolkit approach to overcome this barrier of innovation. Still, this is on a technological level and no digital consideration. Basically, the logistic companies do not possess the knowledge of getting the right innovations.

1.2 Problem discussion

Start-ups could help to get the logistics sector to deal with this barrier of being innovative as they have the expertise dealing with digitalized innovations. The entrepreneurial behaviour of the start-up is resulting into business transformation as the restructuring of corporate models, growth, and performance (Ben Arfi & Hikkerova, 2019; Kohler, 2016) for the ECC. The process of achieving the greatest benefits in the context of technological integration and digital innovation within the logistics companies has never been researched before. This process includes the external and internal technology access of the technological integration (Mathauer & Hofmann, 2019). External technology access options could be corporation with start-ups to get the right innovation.

When an ECC decides to corporate with a start-up, cooperation forms need to be discussed in order to create the greatest potential benefits for both ECC and start-up (Yoon et al., 2018). Cooperation between start-ups and corporates could be made in forms of joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, corporate venture capital investment, strategic alliance, licensing, on business function level as marketing or research and development (Shan et al., 1994; Simon et al., 2019; Weiblen & Chesbrough, 2015). Each form has different characteristics and could influence the outcome of the innovation (Benson & Ziedonis, 2009; Yoon et al., 2018).

Information concerning the proposed field of research is overflowing, still most articles exclude the factor of digital innovations. Most articles discussing innovations on technological level but exclude the digital innovation factors, since this development is recently interesting and therefore could be considered as the latest revolution within the logistics field. According to Jung (2018) start-ups have the knowledge power of dealing with this latest revolution. Besides this, an ECC could apply many cooperation forms, but the interaction between the chosen corporation form and the possible influence on the innovation power remains unanswered. This clarifies the proposed literature gap which needs to be researched to gain the needed insights in how corporate companies can cooperate with start-up companies to achieve effective digital innovations.

1.3 Scope and delimitation

The scope of this thesis covers the cooperation between established corporate companies (ECC) and start-ups, with the aim of taking advantage of the innovation power of the digital logistics innovation of the start-ups. Innovation is understood here and hereafter as a competitive advantage for the corporate, i.e. an improvement of the own entrepreneurial situation. This can apply to financial aspects, the reputation of the company and all aspects relating to the company. The context of the cooperation refers to the innovative power of corporates and the possibility to increase this through different forms of cooperation with external start-ups. In this case, only start-ups are considered as external sources of innovative power, since the thesis focuses on digital-driven innovations and tools. These are mostly still untapped, have not yet achieved extensive market penetration and are therefore usually only offered by start-ups. This thesis looks at the forms of cooperation from the perspective of corporate companies and less from the start-up perspective.

Figure 2: Research scope (own depiction)

Hence, this thesis comes with certain delimitations. The considered innovations, which are the basis for the cooperation, only refer to a logistics environment. This means that these innovations were developed for the logistics sector or can be applied within this environment. Excluded from these innovations, however, are all those which are not digitally driven. When considering these digital-driven innovations, the purpose of use is described, and a basic understanding is created. Technical details and in-depth analyses

of the individual innovations are not mentioned, as they are not very relevant to the form of cooperation. Also, not within the scope of this thesis is the process of start-ups and cooperation, how they can become innovative. Another limitation is the evaluation of the individual cooperation processes, which means that there is no evaluation and therefore no measuring. In this context, financial aspects are also excluded from the scope. Case studies are carried out for the analysis part and the data collection. For the corporate companies surveyed in these case studies, the prerequisite is that they have already cooperated with a start-up.

1.4 Purpose and Research question

The gap identified in the literature shows that there is a lack of analysis of the forms of cooperation between established corporate companies (ECC) and start-ups in the logistics sector and the increase in innovative power through the use of their digitally driven logistics innovations. The constant growth in digital innovations and the rising expectations of customers with regard to the logistics services of corporates are forcing them to invest more and more in digital-driven logistics innovation. The lack of know-how within the company and the high time pressure ensure that many companies rely on innovations from third parties. Therefore, this thesis focuses on closing this research gap, in the area of increasing innovation through digitization and the possibilities of corporates to obtain these from external sources. Furthermore, the most important digital-driven innovations in the logistics sector are presented as well as the individual possible processes of cooperation. Therefore, the aim of this thesis is to give a comprehensive overview of the forms of cooperation possibilities, their influencing factors, and the exact processes with regard to their ability to increase the innovative power of corporates. Hence, the general purpose is formulated as follows:

“To identify digital-driven logistics innovation used by corporates and their most important impact factors as well as forms of cooperation between the start-ups who invented those and corporates who are using them for improvement of their

own innovation power.”

To achieve this purpose two research questions were created to close the existing research gap. To ensure that the first research question can be adequately addressed, the existing literature is first examined for the existing digital-driven innovations in the logistics sector

to provide a basic understanding. With this understanding of digital-driven innovation, the first part of the purpose can be created, with the aim to identify the most important digital-driven logistics innovation and the impact factors for the forms of cooperation and the type of innovation. Therefore, the first research question of this thesis is:

RQ1: In the context of cooperation between established corporate companies and start-ups, which are the most important factors influencing (the choice of) the type of innovation and forms of cooperation?

When the most important digital-driven logistics innovation as well as their innovation power and the impact factors for the type of innovation and cooperation have been identified for the corporates, the relationships between these factors needs to be acknowledged. By linking the impact factors and the associated relationships, it is possible to identify the impacts of the type of cooperation on the innovation power of the various corporates. Based on that approach, the second research question for this thesis is as follows:

RQ2: In the collaboration of corporates and start-ups in the context of digital-driven logistics innovation, what is the relationship between the forms of cooperation and the innovation output?

The results of the two research questions can then be correlated in order to create a contingency for corporates in which the innovation powers can be brought into an interplay. This contingency should help other companies to simplify future cooperation decisions with start-ups in order to strengthen their own innovation power with the help of digital-driven innovations. In order to enable these results, i.e. to answer the research questions and fulfil the purpose, a case study will be conducted with companies that have already cooperated with start-ups in the context of their logistics activities in order to use their digitally driven innovations.

1.5 Outline

In this section an overview of the thesis structure is given. In the introduction, the exact background and motivation for the topics examined in this thesis is presented. Furthermore, the problem of the thesis is discussed in more detail, which is based on the research gap in the literature. In the following section the framework of this paper is defined, and delimitations are made. The problem definition and the delimitation of the thesis leads to the purpose and the related research questions. The second chapter provides the theoretical background and thus the frame of reference for this thesis, based on the literature review. In the third chapter, the research methodology is presented, consisting of the research philosophy, the approach, and the applied design of the research. In addition, the chosen methodology of data collection and analysis is presented with the link to the maintenance of research quality. Chapter four provides an overview of the conceptual framework of the thesis, which is supported graphically. The empirical results obtained from the literature review and case studies are presented in the fifth chapter and then analysed in the sixth chapter. The resulting outcomes and contingencies for corporates are discussed in the seventh chapter and presented in the final chapter eight, together with the resulting constraints and proposals for future research topics.

2.

Literature Review

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter gives an overview of the literature in the research field of digital-driven logistics innovation, the cooperation between corporates and start-ups and its possible forms and influencing factors. It provides a more comprehensive, although general understanding of the topic of this thesis and serves as a basis for the empirical study.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1 Innovation in the field of logistics 2.1.1 Forcing innovation in logistics

The logistics market is facing new challenges in the age of digitization and is forced to change by many developments. While increasing globalization has had an impact on supply chains over the past decades (Busse & Wallenburg, 2011), there is now pressure to technologize the supply chain and to consistently use additional IT services (Mathauer & Hofmann, 2019). According to Mathauer and Hofmann (2019), the pressure for change arises from the increased outsourcing of logistics services, the globalization of markets and thus increased competitive pressure as well as shortened innovation cycles and new competitors due to digitization. Busse and Wallenburg (2011) add that the increased and more in-depth range of services offered by logistics service providers means that there is also a need to become more innovative in these areas in order to remain competitive. In order to keep up with these fast-moving developments, today's supply chains need to be quickly adaptable, i.e. agile, and require disruption risk management to reduce risk (Ben-Daya et al., 2019; Ivanov et al., 2019).

In principle, there is agreement in the literature about the "how" to overcome the challenges. Innovations in logistics help logistics service providers to improve their competitiveness. Only the exact definition and the type of innovation differ. There is widespread agreement on citing technologies as triggers for innovation (Busse & Wallenburg, 2011; Hofmann & Rüsch, 2017; Ivanov et al., 2019; Mathauer & Hofmann, 2019). These technologies are often placed in the same context as digitization and Industry 4.0, such as digitally controlled supply chains, cyber-physical systems, and Internet of Things (IoT) (Ben-Daya et al., 2019; Hofmann & Rüsch, 2017; Ivanov et al., 2019). Busse and Wallenburg (2011) differentiates innovation in a company into two

areas. On the one hand, the ability to bring about innovation, i.e. an innovation process. This consists not only of the technology required, but also the will and awareness to create new innovations. The second aspect is the innovation systems, i.e. all tasks that go beyond the creation of a single innovation process. In this context, the strategy linkages with which innovations can be managed are considered primarily at the organizational level. Flint et al. (2005) add that in addition to technology, innovations can also arise in processes and services. In the following, the connection between innovations and digitalisation in logistics is shown.

2.1.2 Digital-driven innovation

Innovations in logistics have already been dealt with extensively in the literature, as well as its indispensability for a company in order to survive in the market (Flint et al., 2005; Grawe, 2009; Wallenburg, 2009). However, the image of innovations in logistics has changed as a result of the digital transformation, which is still in its infancy. In recent years, innovation prior to digitization has essentially been the expansion of the service offering around the primary product (Lampe & Stölzle, 2012). Especially through the creation of digital technologies, innovations are now digitally controlled. The innovative power of digital-driven innovations and how this term can be defined on the basis of existing literature will be discussed in more detail below.

Hsiao and Chang (2019) see the strengths of digital-driven innovation, especially on the operational side. In particular, the use of information technology contributes to improving operational efficiency. The technological innovation capability of a company still leads to an improvement in services (Agrawal et al., 2020; Queiroz & Telles, 2018), but mainly to innovations in the area of corporate processes and business models (Hsiao & Chang, 2019). In the literature, the keywords digital innovation, information technology, technological innovation and digital technologies are consistently associated with a competitive advantage (Agrawal et al., 2020; Barczak et al., 2019; Hsiao & Chang, 2019). This competitive advantage is expressed by a reduction in costs, mainly on the process side, by a general increase in efficiency and thus also an increase in organizational performance (Hsiao & Chang, 2019). Agrawal et al. (2020) add that the innovation powers are especially on the side of a better networked supply chain, through robustness and flexibility. In this way, partnerships and connections can be improved both in the direction of the supplier and on the customer side, in the form of improved customer

service. This creates increasing sales figures as well as increased development of the company. In principle, the innovative power of digitally controlled innovations in logistics can be expressed in many ways, whereby the benefits and the desired goal can move in different directions. Digital-driven innovations can generate different potentials and arise from different motives, e.g. cost optimization or reduction, reduction of risk potential, increase efficiency due to increased transparency in the supply chain, better availability, and quality of data, etc. (Stölzle et al., 2018).

The innovation powers most frequently mentioned in the literature are increasing efficiency, quality, and flexibility, reducing costs, expanding the product portfolio, and creating disruptive innovations (Najafi-Tavani et al., 2018; Nasution et al., 2011; Stölzle et al., 2018). Thus, the powers of digital-driven innovations mentioned are for the most part congruent in the literature. The definitions of digital-driven innovations from the literature show that there is a general, uniform basic understanding of the term. The most frequently used term or synonym for the word innovation is 'technology' (Agrawal et al., 2020; Barczak et al., 2019; Hsiao & Chang, 2019; Ivanov et al., 2019; Mathauer & Hofmann, 2019). Barczak et al. (2019) define digitization as a transformation of old structures and relationships, both on the technical and organizational side, to a digitized set of structures and relationships. A digital-driven innovation is thereby triggered by a digital technology and generates new forms of digitization. Mathauer and Hofmann (2019) add that these forms may differ in intensity. For example, the expansion or improvement of existing structures and technologies has a significantly different effect than radical features such as the introduction of completely new disruptive technologies.

Hsiao and Chang (2019) and Ivanov et al. (2019) combine digital-driven innovations with the business model of logistics and stress the importance of those for the logistics sector. Hsiao and Chang (2019) emphasize the importance of information technologies, which enable logistics services to create further innovations. The principles and models of supply chain management are being repositioned on the basis of disruptive innovations triggered by digitization and Industry 4.0, which are increasingly influenced by these technologies (Ivanov et al., 2019). In order to clarify the technologies and innovations such as Internet of Things (IoT), big data analytics (BDA) and cyber-physical systems into a context for its leading role as a basis for cooperation between corporates, the term digital-driven logistics innovation is defined as follows for this thesis:

“Digital-driven logistics innovations are data-based, autonomous and self-controlling technologies that are linked together in socio-technical structures and enable a more efficient and cross-company logistics process design by means of these technologies. They can have incremental or radical properties or be of a disruptive nature and were designed for use in logistics or were misused for this purpose. Their innovative strength lies mainly in the characteristics of high robustness and high efficiency within the supply chain.”

Based on this definition, the exact perspectives and applications in logistics are examined in more detail below.

2.1.3 Technological, process, service, and business model innovation perspective

As described before logistic companies use innovation to improve their performance and competitive advantage. Changes are required on different layers within the business as the strategy, customer, and operational level (Hristov & Reynolds, 2015) are highly impacted by innovations. Applying technology within the supply chain is one way to achieve this innovation. Technological innovations can be divided in four different classifications (Mathauer & Hofmann, 2019): customized hardware is bringing physical solutions for customer needs, standardized hardware which is hardware technology accessed by stakeholders, customized software is bringing software solutions for customer needs and finally the standardized software technology which is accessed by stakeholders. The integration of various technologies is referred to as digitization of the supply chain.

Examples regarding these digital technologies include cloud computing, the internet of things, three-dimensional printing (3D printing), artificial intelligence, big data analytics, blockchain, automation, robotics, drones, machine learning, augmented reality, autonomous vehicles, and digital platforms (Barczak et al., 2019).

So considering the technological perspective of innovation within the digital world the next statement can be made: ‘technological innovation within the digital world considers the application and implementation of customized and standardized hardware where the support of standardized and customed hardware is needed to make the system work’. Applying and implementing these technologies resulting into dramatically changed firm’s (Mola et al., 2017) operations, logistical activities, communication and marketing strategies, relationships with suppliers and customers. This means that technology is

changing the process, service, and business model within the supply chain. For instance, the implementation of three-dimensional printing allows manufacturing in smaller batches and in relatively smaller facilities resulting into manufacturing postponement and locating manufacturing closer to customers and point of use (Holmström & Partanen, 2014). So, applying three-dimensional printing is impacting the processes and services for the better as the technology allows manufacturing in smaller batches and therefore influencing the daily processes within a company. Concluding the result of implementing a technological innovation is highly impacting the processes within a company and therefore require changes and adaptions within the processes of a company.

From the service perspective “digital manufacturing and access to digital infrastructure” (Holmström & Partanen, 2014) result into overlap of product design and improvement of the equipment within the process. New business models arise from customer centric approaches in the manufacturing process related to the more active role for consumers within the value chain (Durach et al., 2017).

Logistics service providers (LSP’s) struggling with innovations and the management of these innovations. The innovation level at these companies is mostly focussed on incremental innovations instead of radical innovations (Wagner, 2008) as the LSP is reacting to specific customers’ requirements and simply adapts by making small customer specific solutions (Wagner & Franklin, 2008). Studies show innovation at LSP-shipper relationships level can positively impact the effectiveness in the supply chain (Wagner, 2008), but the problem remains with offering innovations for a larger customer base. This is the main reason why from a service innovation perspective, logistics service providers are struggling with implementing their innovations and introducing the innovations for a larger customer base. On the other side Wagner (2008) is pointing out that the share of innovators within the transportation and logistics industry is significantly lower than the manufacturing industry and possibly influence the innovation level as well. The transportation and logistics industry shows a share of only 30% while at the manufacturing industry was 52%. Connected to the processes of a company the digital innovations are impacting service levels as well in the form of producing smaller batches and therefore result into a lower lead time. Still in general the LSP are struggling with being innovative as their culture is focussing on incremental changes rather than radical innovations possible because of the low share of innovators within the logistics sector.

Decisions to implement digital technologies demand reconfiguring operations and develop information technology (IT) capabilities for effective and efficient use of knowledge and change management within the supply chain (Mola et al., 2017). Applying such systems resulting into increased level of complexity and therefore creating opportunities in offering different business models that rely on technological choices. One example of these business models are digital platforms. These platforms are collecting existing knowledge about corporate entrepreneurship strategies and product innovation. This enables companies to be connected with suppliers, customers, and other actors (Ben Arfi & Hikkerova, 2019).

From business model perspective existing business units are struggling designing disruptive concepts and therefore employing accelerators to create ideas outside the scope of existing business units (Kohler, 2016). For instance, Barclays stimulated start-up activity on a product platform to challenge start-ups to build their own made products on top of company’s platform or Nike invited start-ups to develop product and services for their digital activity tracking platform resulting into valid testing of products and building a network of developers. Connected to the implementation of digital technologies resulting into arising new business models for companies relying on technological choices existing new ideas to create disruptive concepts expanding to new markets and gain advantage in validation testing and building a competence network. The above-mentioned perspectives are discussed in more detail in the following subchapter using examples.

2.1.4 Digital-driven logistics innovation

Some examples will be discussed after analysing the different perspectives of innovation within the logistics field. Based on the classifications of Mathauer and Hofmann (2019) two out of the four classifications can be excluded since the focus of the study is on the digital driven innovations within the logistics area. These two classifications are the hardware related innovations are excluded of the literature review. The main focus of this research is on the digital aspects of software applications.

Nevertheless, understanding is gained that hardware technological innovations are closely related to software innovations. For instance, the additive manufacturing or 3D printing is considered as synergy in technological or hardware and digital or software innovation

and therefore always cooperating to make the digital innovation possible (Holmström & Partanen, 2014). Same understandings could be mentioned about the other recent digital innovations within the logistic area like cloud computing, the internet of things, three-dimensional printing (3D printing), artificial intelligence, big data analytics, blockchain, automation, robotics, drones, machine learning, augmented reality, self-propelled vehicles, and digital platforms (Barczak et al., 2019; Holmström & Partanen, 2014; Hsiao & Chang, 2019; Li & Wang, 2017; Queiroz & Telles, 2018).

Other more specific technologies are considered effectively implemented and applied within the food and retail sector within the supply chain (Li & Wang, 2017) as for example the ratio frequency identification technology (RFID) for real time information of product identification or time-temperature integrator for storage conditions and location positions insights. These technologies are highly connected to quality monitoring within big data applications connected to big data analytics or BDA (Queiroz & Telles, 2018) which result into better decision-making processes.

When implementing and applying certain risk and outcomes are known. Based on the article of Barczak et al. (2019) digital innovations are affecting many components of the businesses positively. Especially the competitive advantage, also known as the innovation power, is highly related to the implementation of digital innovations. The most frequent competitive advantages result from a cost reduction or optimization, from an increased efficiency in the processes or from a reduction of risk potentials (Stölzle et al., 2018).

2.1.5 Cooperation as a lever for innovation

This positive effect of digital innovation on businesses is also confirmed by Tranekjer (2017). They are an important factor in the success of a company and ensure its long-term competitive advantage. However, innovations have the characteristic that their outputs are often uncertain. High investment in in-house R&D or the development of in-house investments does not guarantee that innovation will result (Blanchard et al., 2013; Tranekjer, 2017). Projects in the development of innovations are usually very costly and also risky due to the uncertain output (Tranekjer, 2017). As many companies have only limited resources, especially in know-how, more and more companies are taking advantage of the opportunity to open up their own boundaries to an inflow and outflow of knowledge in order to improve their own innovations or to create innovations from

external sources (Wikhamn & Styhre, 2019). Cooperation with external companies can change the innovation process of a company in a positive way by enabling the bundled use of knowledge and other external resources (Blanchard et al., 2013).

The process of active strategic integration of the corporate environment to increase an organization's own innovation potential is also called open innovation (Chesbrough, 2003). Through open innovation, more diversified and broader forms of innovation models are possible, which make the output of an innovation more calculable (Nambisan et al., 2018). Nambisan et al. (2018) emphasize the importance of platformization in connection with open innovation in the context of digitization. Platformization is the use and provision of digital platforms as a method of creating value (Jha et al., 2016; Nambisan et al., 2018). Digital platforms offer an openness of resources, which enables companies to use these resources, expand their own offerings and open up new markets (Ceccagnoli et al., 2012). The integration of platforms as an open innovation by external platform owners therefore promises an expansion of their own business and the opportunity to develop further innovations.

In their paper Blanchard et al. (2013) show that the obstacles for a company increase when it invests more in its own research and development. The reason for this is the broader search for innovation by taking on several innovation projects at the same time and thus a higher probability of encountering obstacles. They also find that cooperation encountering obstacles. This is also confirmed by the study of Wikhamn and Styhre (2019), who show that the risk and uncertainties in the innovation process are reduced when cooperation with external partners is undertaken. The pharmaceutical company analysed in the study also applied two different forms of cooperation, a spinout initiative, and a divestment process, which led to this result, but in different forms. On the one hand, this shows that cooperation can be a lever to bring about innovation within the company, but also that the innovation power depends on the form of cooperation. This aspect will therefore be examined in more detail in the following chapter.

2.2 Cooperation with start-ups to thrive innovation 2.2.1 Challenges of corporates being innovative

The ever-increasing pace of globalization is creating ever stronger and more complex competitive conditions on the market for companies. Falling trade barriers and thus easier

access to markets for new countries means that there is an ever-increasing number of competitors offering new, innovative products and services (Patterson et al., 2003). Information flows in real time throughout trade networks, thanks to increasing opportunities in technology and lower investment costs. Richter et al. (2018) argue that the fast, progressive growth in technologies allows direct access to the customer without time limits. Corporates are therefore increasingly faced with the challenge of managing this competitive market, which is characterized by more demanding customers, shorter product life cycles and individualization of uncertainty and complexity.

As already discussed in the previous chapters, continuous innovation is the prerequisite for future corporate growth. Established corporate companies (ECC) often have difficulties in identifying new technologies that could serve as such innovations (Benson & Ziedonis, 2009; Patterson et al., 2003). Furr et al. (2016) note that it is almost impossible for companies to provide the breadth of innovation or technology demanded by customers at the pace they are attempting to do so. A synchronization with new technologies must be ensured in all areas of the company, in the area of the emerging e-commerce market and the networking of the supply chain in order to increase the company's own market penetration (Patterson et al., 2003). While in the past, quality assurance and cost reduction were decisive for maintaining one's own market share (Patterson et al., 2003), today the ability to innovate at the forefront is required, at the same pace as the entire competition (Porter & Stern, 2001).

In order to keep up with this pace and maintain synchronization, many corporates have to rely on external resources. Therefore, corporates are increasingly focusing on cooperation with new ventures and start-ups in order to use their knowledge and innovations to strengthen their own innovative power (Richter et al., 2018). However, established firms often find it difficult to identify the right innovations in the marketplace (Benson & Ziedonis, 2009), and managers in particular are faced with too many opportunities (Furr et al., 2016). The fact that the technologies go far beyond a single area of the company means that companies usually cooperate with several partners at the same time, and managers are faced with the challenge of managing the cooperation accordingly, or, in the first step, do not have enough basis for decision-making to be able to make the right choice of the form of cooperation (Furr et al., 2016). On the basis of this approach, the potential, and characteristics of cooperations with start-ups will be

examined in more detail in the following, in order to be able to shed more light on their forms and processes.

2.2.2 Innovation potentials in cooperation with start-ups

According to the European Startup Monitor (Kollmann et al., 2017) established companies its openness towards start-up cooperation is helping both organisations. This change of innovation processes is called: ‘Open innovation’. This includes integration of external organisations as start-ups, universities, licensing agreements related for improved innovation. Where our interests lay within the factor of cooperation with start-ups. Reason for this change of innovation processes is linked to the entrepreneurial behaviour is resulting into business transformation as corporate renewal, (long-term) growth and performance (Ben Arfi & Hikkerova, 2019; Kohler, 2016). With start-ups as cooperative partner this behaviour can be achieved as they benefit from technical expertise and the patents hold by the innovative start-ups (Kollmann et al., 2017; Yoon et al., 2018) as their core mission is focussed on developing new products and exploring new ideas (Jung, 2018; Kohler, 2016). On the other side, start-ups may benefit from the corporation’s distribution channels and knowledge concerning national and international markets (Yoon et al., 2018). Sharing resources might be the cheapest way for ECC’s to create cooperation between start-ups. For instance, Google and Microsoft allow start-ups to make use of their technologies and digital tools to expand their digital business (Jung, 2018). On the other side, ECC’s use the culture differences of start-ups to change their own employees’ mind-set to be innovative.

When cooperating with start-ups as corporate companies the partnership needs to be discussed as well as the type of contract and specific contract terms influence the achievement of greatest potential benefits for the start-up as well as the corporate companies (Yoon et al., 2018). To achieve the greatest potential benefits for both organisations three types are mentioned by the literature. The first two types considering upfront payment including two options: milestone or royalties. The third type is a possible acquisition model (Benson & Ziedonis, 2009; Yoon et al., 2018).

Related to the acquisition model Benson and Ziedonis (2009) are pointing out the need and importance for established firms to renew and extend their internal capabilities and resources by applying external technologies. The start-ups are a perfect fit for meeting

these demands. However, the established corporate firms are struggling with identifying new technologies or recognize the potential benefits related to applying these new technologies. Another reason mentioned by Jung (2018) is that corporations its strategy is driven by various key performance initiators (KPI’s) which is causally linked by their inability to innovate.

A way for established corporate companies is to make use of corporate venture capital where the ECC is becoming a minor stakeholder within private companies to provide a potential gateway into interesting technologies from start-ups. The greatest positive influence is experienced within the research and development productivity for established companies when applying this specific method of cooperating as they learn from expertise of start-ups linked to failed attempts and success to use this knowledge within the own company. Where greater performance is achieved when cooperation is established with privately owned start-ups instead of start-ups already active on public equity markets. For a better understanding of ECC and start-ups and their background, these are discussed in more detail below.

2.2.3 Characteristics of corporates and start-ups

As mentioned before, start-ups can help ECC’s innovate and a lot of cooperation types are possible. But what is exactly the difference between the two companies? What is classified as a start-up and what is an ECC. These questions are going to answered by using the literature. Firstly, the start-up is going to defined, followed up by the ECC.

Start-ups are defined as companies younger than 10 years and feature highly innovative technologies or business models. Their ambitions are high as they strive for significant growth in sales and size of the company (Kollmann et al., 2017). So, they are small scale organisations (Nurcahyo, 2018) where ECC’s are large scale organisations. The life cycle of organisation development starts with the start-up phase, followed by emerging growth, maturity and finally revival. To classify them within the life cycle of organisation development they are typically at the starting phase. The ECC’s are mature companies and therefore in their maturity phase. Their goal is to stay within this phase preventing the revival.

The business goals of start-ups are entering existing markets or sometimes create a new market by developing innovative products or services. Where the ownership of a start-up

is characterized by their centralized decision-making processes related to the flat hierarchies within the internal start-up landscape (Kollmann et al., 2017) and direct supervision. ECC have a different structure and strategic as ECC contain multiple layers within the company which makes is influencing their decision-making processes of being less effective and their strategic focus is on rather on profits.

Still they are not simply a smaller version of corporations. Their structure and culture are significantly different from these bigger corporations as the start-up is designed to create new products and service and deal with the high uncertainty which is the result of their innovative behaviour (Jung, 2018). Because of the small scale and high uncertainty still the majority of the ups defined responsibilities and job descriptions within the start-up.

2.2.4 Forms and impact factors of cooperation

Since the necessity of corporates for cooperation with start-ups and the resulting potential was demonstrated in advance, the question now arises as to how a corporate should approach this cooperation. The difficulty in identifying potential is also a major factor in the choice of the form of cooperation. In addition to the final choice of the form of cooperation, the literature also emphasizes many external and internal factors that influence it (Gallie & Roux, 2010; Markowitz, 1995; Sie et al., 2014).

External factors

External factors relate mainly to the market structure and the regulations prevailing in the market (Markowitz, 1995). However, these factors have only limited influence on the scope and nature of cooperation and provide more of a management view of the importance of cooperation and its affordability (Fashoyin, 2006). New entrants to the markets, changes in demand and the conditions for entering the market play an important role. In the cooperation with a start-up, the local regions of both parties can also be a factor of influence. Particularly in the area of platformization and digital products, local proximity can usually be treated as a secondary consideration (Nambisan et al., 2018), but in the context of the new market development, the region gains great importance (Fitjar et al., 2013). For example, the innovations of start-ups are usually still strongly penetrating the market, but their development and conception is based on certain influencing factors of an industry or market.

Internal factors

Internal factors such as the corporate culture, the ownership structure of a company and its financing and management structure have a more direct influence on the form of cooperation. In their paper Sie et al. (2014) particularly emphasize the internal characteristics of the cooperation partners. Corporate cultures can influence the success or failure of a cooperation and are characterized by factors such as the personality of a company, which can strongly influence the pattern of a social network. The balance of power between the companies also determines the form (Keltner et al., 2008). In most cases, the financial situations of the two companies are decisive in this regard, which help one to achieve more or less power. Especially for the start-up, the size, i.e. the number of employees, and the status and reputation of the corporate is of great importance (Jensen & Roy, 2008; Sie et al., 2014). Size can also be important for a start-up when it comes to communication and closer cooperation, as the work mentality is usually different, and start-ups prefer a fast and direct communication channel. The status of the cooperation partners can also be a factor for the corporates, in the context of existing or past experiences of the start-up with other companies (Jensen & Roy, 2008). If the innovation is not intended to be a product of the company itself, but merely a support, well-known references of the start-ups may tempt them to cooperate. The financing structures are particularly decisive in the breadth of the cooperation (Fashoyin, 2006; Gallie & Roux, 2010). For established corporates companies, financing is an important factor, but it is not the most decisive one. Risk and loss aversion of the corporates as well as its economic situation are taken into account (McCarter et al., 2010).

If the company has more capital available for the development or acquisition of innovations, forms of cooperation are usually chosen that provide for the entire merger of the start-up into the company (Carbone, 2011). The risk of misinvestment increases with this form of cooperation, as this initially involves the largest investment costs, while the possibilities for identifying potential and success remain the same. The financing regulates the ownership structure of the cooperation and usually also the management structures between the parties. The abilities and possibilities for cooperation management become significant in coordination and administration (Sie et al., 2014). Thus, requirements must be defined from management level, the associated dependencies as well as the desired working procedure and its execution (Schreiner et al., 2009).

The most decisive internal factor for the choice of the form of cooperation is the set business strategy of the corporates (Fashoyin, 2006; Jensen & Roy, 2008; Sie et al., 2014). Thus, a cost reduction strategy has a completely different procedure and measures than, for example, the expansion of a product line. The business strategy has a direct correlation to the expected impact on the cooperation. General business strategies such as the expansion of products, services, quality improvements and stronger customer orientation require increased investment. However, there are strategies that do not require significant investment, such as brand development or aggressive marketing. In the strategy to promote innovation, increased investment is usually required, as these either have to be developed first or bought in externally (Sie et al., 2014).

Once these internal and external influencing factors are known, corporates can get a more precise picture of the possibilities and forms of cooperation. Depending on these factors, cooperation can vary from simple free business relationships to mergers of the two companies (Shan et al., 1994; Simon et al., 2019). The most common forms of cooperation between established corporate companies and start-ups are highlighted in more detail below.

Partnerships

Shan et al. (1994) investigate cooperation with start-ups in order to gain innovations in the field of biotechnology. These agreements serve to learn new technologies and provide a method for start-ups to obtain financial and sales resources. The contractual form of the agreement can be organized in various ways, from joint ventures to R&D partnerships (Hamilton, 1986). The main difference in the forms, especially in the area of partnerships, is the participation of equity. A distinction can be made between equity and non-equity or contractual partnerships (Gallie & Roux, 2010; Simon et al., 2019).

One form of equity-based partnerships are research joint ventures, in which two companies join forces in a subordinate organization to conduct joint research on new innovations (Gallie & Roux, 2010). This form offers more flexible solutions but is less common today. On the other hand, non-equity-based contractual partnerships, which are often concluded for a shorter period of time but do not affect the commitment (Hagedoorn, 2002). These forms of cooperation can be set up as market transactions with the aim of acquiring external technologies. This form can also be described as

outsourcing and is usually associated with the acquisition of patents, as these promote the acquisition of the technologies.

Another form of cooperation in this area are joint projects, which are used exclusively in the research phase and not in the development phase (Caloghirou et al., 2003; Gallie & Roux, 2010; Hagedoorn, 2002). In this case, two organisations are investigating a risky research area, the outcome of which is highly uncertain (Caloghirou et al., 2003). The aim is to create technological breakthroughs, but the uncertainty in the result is the reason why this form hardly ever occurs in start-ups. All these forms of partnership can be formal or informal (Gallie & Roux, 2010). In a non-contractual partnership, two companies can also exchange technical information without any basis. For example, if a technology manufacturer wants to test his product and another company can use this technology and in return send the collected data to the manufacturer. In principle, informal cooperation prevails in the area of partnerships.

In the case of particularly large research projects, multilateral partnerships also come into play, i.e. an association of several companies in order to share the costs and risks as well as for an increased gain in knowledge and skills (Sakakibara, 2001). The concept of partnership-based cooperation is particularly interesting when companies want to engage in technical sourcing, since these forms of cooperation are mainly focused on joint research into new innovations or technologies (Nicholls‐Nixon & Woo, 2003).

Strategic alliances

In the course of a greater bond between the companies, partnerships are being expanded, especially from start-ups to strategic alliances. Access to higher recognition and more resources makes these alliances particularly attractive to start-ups and enables faster growth through interaction with listed companies (Chang, 2004). This is also due to the better perception of the start-ups through the acquired reputation of the corporates and the greater access to resources (Baum et al., 2000).

The best known and most frequently used form of a strategic alliance is an academic spin-off. An academic spin-off is an enterprise, usually in the high-tech field, which is supported by academic researchers to extend previous research results with new contexts in order to gain new insights (Hagedoorn et al., 2018). According to the definition of Belitski and Aginskaya (2018), academic spin-offs consist of academic researchers, a

cooperation between a university and a for-profit company, and the sale or production of technologies from the research area. This form often occurs in research-intensive industries such as the biopharmaceutical industry, where companies are heavily dependent on current research for the development of new products (Hagedoorn et al., 2018). In addition, collaboration with a respected academic institution enhances the reputation of the corporates. An academic spin-off has a high degree of knowledge acquisition and creation of novelties and often enjoys political support to generate economic value through research. Funding often plays a major role in supporting the research work (Weiblen & Chesbrough, 2015). One form of funding are corporate incubations, in which companies create a kind of incubator to generate new innovations, which, however, do not match the actual subject areas or business models of the companies. The business incubator is provided with the financing, expertise, and contacts to create radical innovations as in a start-up setup. If this is successful, this innovation can be brought to market independently by the business incubator and can be added to the company's existing business model (Kohler, 2016; Weiblen & Chesbrough, 2015).

Another possibility of funding is offered to sponsor organizations with outside-in start-up programs. Here, start-start-ups can provide their technologies and ideas to the sponsors in order to further develop and implement them (Weiblen & Chesbrough, 2015). Corporates benefit in particular from external innovation, which can give them a competitive advantage in hot areas. The greatest advantage here is the focus on several approaches simultaneously, which can at best learn from each other. Such forms of cooperation can also be described as corporate accelerators (Kohler, 2016). The focus here is not only on individual founders but on small teams that receive temporary support from corporate. The use of corporate accelerators makes the process of value creation through cooperation with start-ups more cost-effective and efficient (Anthony, 2012; Kohler, 2016). A classic form of such an accelerator is the pilot project. Here, the development of existing innovations of the start-ups is financially supported by the corporates. This represents lower costs and a shorter period of time for the corporates to search for innovative solutions with less risk that do not affect the core business (Kohler, 2016). Another accelerator is the possibility for the corporates to become a customer of the start-up and its innovation. Here, too, several solutions can be tested in parallel, but this always involves costs. This form can represent a great added value for both sides, if the start-up

wins a large customer for its product and the corporate in return can eliminate a weak point or the product extends its range of services (Weiblen & Chesbrough, 2015). A third option is to use the corporation as a kind of distribution partner. If the start-up's target groups are already represented in the corporate's existing distribution network, this network can be used to offer the products via the corporate (Kohler, 2016; Weiblen & Chesbrough, 2015). In return, the corporation usually benefits from using the product or expanding the product portfolio. A cost-intensive accelerator is the acquisition of a start-up company to develop new innovations (Carbone, 2011; Kohler, 2016; Lerner, 2013). The form of mergers and acquisitions will be examined in more detail below.

Corporate venture capital

A more profound form of cooperation than funding is venture capital, which, in addition to financing, also has an influence on strategic goals (Hall, 2015; Weiblen & Chesbrough, 2015). With corporate venture capital, companies participate financially in the start-ups. If the knowledge gained from this cooperation is useful for the company, it may also acquire the start-up completely (Hall, 2015). The most common form is an independent corporate venture, financed by the sponsors, which can act flexibly, quickly, and unbiased. In addition to the financing, the corporate venture capital is also used to pursue the interests of the corporates and to create innovations for their purposes (Ivanov & Xie, 2010; Weiblen & Chesbrough, 2015). They are also intended to promote the joint research and development of the two companies.

In this context, one form of cooperation is becoming increasingly interesting in the context of digitization: the inside-out platform start-up programmes. Here, the start-ups serve as a kind of supplier, which should develop new innovations and products based on the existing technologies of the corporates (Weiblen & Chesbrough, 2015). The focus is on the platforms of the companies as the new and dominant type of innovation. The company's goal may be to be the platform leader and to benefit from any further innovation offered on the platform. A classic example is the operating system Google Android, which participates in the turnover of every app offered (Gawer & Cusumano, 2014).

Mergers & Acquisitions

Already in the case of company accelerators, mergers & acquisitions was mentioned as a cost-intensive form of cooperation. In this form, it is first examined whether resources are consolidated on the corporate side or on the start-up side (Carbone, 2011). Then it can be decided whether the merged company remains as an independent entity or is integrated into the corporates (Cherep et al., 2019). Carbone (2011) analysed four known models of how to proceed after a merger. In the cross-leverage model, the resources, i.e. technologies and employees, are transferred from the start-up to the corporates, but the acquisition remains an independent business unit. This model is mainly used when the portfolio of the start-up is largely congruent with that of the corporates (Finkelstein, 2017). These parts are rationalized in the course of the merger. The next model, 'new bet', transforms the acquisition into a stand-alone business unit to open up new segments in the market. This model is often used when the start-up product has a high value proposition but does not have a sufficient reputation and therefore uses the corporates' reputation (Carbone, 2011; Schuhmacher et al., 2013). The product remains an independent business unit. However, the start-up in particular is confronted with challenges such as a lack of brand, unwanted help or influence from the corporates and the alignment of different processes.

The third known model is called 'top up' and provides for the subdivision of the acquired company. The company is divided into different portfolios, which are then individually integrated into the corresponding areas of corporate (Carbone, 2011). In this way, additional resources can be made available selectively and possible problem areas and gaps can be closed more quickly (Veugelers, 2006). Finally, the most common model of a merger is the 'double down' model. This model provides for the merger of the assets of both companies, consolidated at corporate. The corporate often chooses this solution if they already have good market access, the corresponding customer base, and a strong brand name. The merger with start-up is then often used to add a particular innovation to the corporate portfolio or to obtain sole rights and use (Kreutzer, 2012).

2.2.5 Measurability of unspecified impact factors through indicators

In addition to the target values as external and internal influencing factors, there are also general factors which, in contrast, influence the preliminary stages of a cooperation. The type of innovation and the general conditions of the company play a major role. In the