Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fcss20

Sport in Society

Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics

ISSN: 1743-0437 (Print) 1743-0445 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fcss20

Jokerit’s move to KHL: an odd momentum in the

commercialization of Nordic elite ice hockey

Jyri Backman & Bo Carlsson

To cite this article: Jyri Backman & Bo Carlsson (2019): Jokerit’s move to KHL: an odd momentum in the commercialization of Nordic elite ice hockey, Sport in Society, DOI: 10.1080/17430437.2020.1696537

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1696537

© 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

Published online: 06 Dec 2019.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 38

View related articles

Jokerit’s move to KHL: an odd momentum in the

commercialization of Nordic elite ice hockey

Jyri Backmana,b and Bo Carlssona

aDepartment of Sport Science, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden; bDepartment of Sport Science, Malmö

University, Malmö, Sweden

ABSTRACT

The article is set to target several tensions, problems and possibilities in Finnish (and Nordic) men’s elite ice hockey, which have arisen due to increasing commercialization and professionalization. This process has accelerated simultaneously with the recent development and advances of the Kontinental Hockey League (KHL), in addition to the constant and general influences of NHL (i.e., Americanization). Thus, the essay will focus on Jokerit as an illustrative case. To state, Jokerit, founded in 1967, is a powerhouse in Finnish ice hockey, both sport-ingly and financially. The commercialization of Finnish elite ice hockey culminated in 2014/2015 when Jokerit joined KHL. This article reflects on Jokerit’s financial and legal challenges, as well as the commercial press and progress in Nordic elite ice hockey and thus on Jokerit’s drift towards KHL. In addition to these topics, the essay presents and discusses different aspects of the progress of KHL, as well as its reasons and consequences.

Introduction

‘Jokerit lähtee KHL:ään’ (‘Jokerit leaves for KHL’) was the major sport news in Finland in the summer of 2013 (Helsingin Sanomat 2013-06-29, p. A6). Rumours that had circulated in Finland were confirmed at a press conference in Hartwall Arena, Helsinki, on June 28, 2013. Jokerit was going to leave the Finnish ice hockey league for the international Russian-owned professional ice hockey league, the Kontinental Hockey League (KHL; Russian: Кoнтинeнтaльнaя xoккeйнaя лигa). Undoubtedly, Jokerit’s unexpected move from the Finnish Premier Ice Hockey League (SM-liiga) to KHL, one of the biggest and most suc-cessful ice hockey clubs in financial terms, was a huge and astounding step in relation to the traditional organization of Finnish elite ice hockey, as well as of Nordic elite ice hockey in general. Evidently, an action of this kind, which is normally associated with proceedings in the American Major Leagues, will challenge as well as modify the conception of Nordic elite ice hockey.

Thus, by taking a point of departure in Jokerit’s transfer, the essay focuses on frictions as well as prospects emerging in elite hockey in the Nordic countries1 in the wake of the

© 2019 the Author(s). published by informa UK Limited, trading as taylor & Francis Group CONTACT Jyri Backman jyri.backman@mau.se

this is an open Access article distributed under the terms of the creative commons Attribution-noncommercial-noDerivatives License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way

KEYWORDS

Political pragmatism; Americanization; entrepreneurship and sport in transition

tensions between traditional sport ideologies and increasing commercialization. In addition, the subject highlights the influence of the National Hockey League (NHL) and, recently, the impact of the Kontinental Hockey League (KHL). The presentation and the analysis will be shepherded mainly by the concepts of modernization and ‘Americanization’ as well as the perspectives of the politicization and political images of sport.

Methodologically, the essay is basically a case-study (Jokerit), with the aspiration, how-ever, of including a general analysis and findings related to a contextual understanding of the actual hockey leagues (SM-liiga, NHL, KHL) and their structures and impact. The material, which has been collected in archives (the Finnish Sport Museum and Archive in Helsinki), in newspapers (Aftonbladet, Helsingin Sanomat, Iltalehti, Ilta-Sanomat) and in magazines, as well as through readings of legislation has undergone a documentary analysis.

Jokerit: a powerhouse in Finnish ice hockey

Jokerit, founded in 1967, is a Finnish-speaking club from the eastern part of Helsinki and the opposing pole of Swedish-speaking IFK Helsinki, founded as early as 1897. Unquestionably, Jokerit has established itself as one of Finland’s most successful ice hockey club in a sporting sense and has won numerous Finnish championships and European Cup gold medals. In addition to its sporting achievements, Jokerit is among Finland’s largest ice hockey clubs in economic terms. It is thus a powerhouse in both Finnish ice hockey and in sports at large. Closely intertwined with the Joker logo (see below), it has also been a

rec-ognized force in the Nordic and European elite ice hockey in general (Aalto 1992, 26–27,

122–131, 160–161 and 208–210, Wickström 2012, 40–42, 169–189 and 194–214, Mennander

and Mennander 2004, 40, 58, 238–243, 250–252, 264–266 and 270–273).

It is important to stress that Jokerit’s organization was divided, like several other Finnish elite ice hockey clubs, in connection with the establishment of the Finnish Premier League,

SM-liiga, in 1975 (Aalto 1992, 144, 160 and 208–210). Thus, Helsinki Hockey-75 became

the right holder of Jokerit at the start of the SM-liiga, while child and youth ice hockey continued in the Helsinki Jokerit non-profit club. However, in 1980 Helsinki Hockey-75 transferred this right in the SM-liiga to Jokeriklubin Tuki, which likewise sold its rights in SM-liiga 1988 to Jokeri-Hockey Ltd. In connection with the 1980 transfer to Jokeriklubin Tuki, it was agreed that the elite team, regardless of series affiliation, should remain labelled and branded as Jokerit, keeping the Joker logo (Aalto 1992, 144, 160 and 208–210).2

The Jokerit dynasty started in 1991 when Harry ‘Hjallis’ Harkimo, an entrepreneur, bought 74 percent of Jokeri-Hockey Ltd. with support from the Finnish ice hockey mogul

Kalervo Kummola.3 After Harkimo had attained control of Jokerit and offered inspiration

and knowledge – such as organization and market strategies deriving from North America and NHL – Jokerit started to progress. Despite of its huge impact and practical influence, it is too simple to highlight one person, like Harkimo, as the engine of the commercial progress of Finnish elite ice hockey. Still, it is impossible to exclude or neglect Harkimo’s significance and his influence on Jokerit and on Finnish ice hockey in general.4

Initially, however, Harkimo’s engagement and take-over of Jokerit was like a tremor for its supporters. Previously, Harkimo was identified as an IFK Helsinki supporter, the big rival to Jokerit and, above all, a Finno-Swedish club. This shock increased as Harkimo was going to integrate the club into his private business. However, the negative attitudes among the supporters changed along with Jokerit’s successes on the ice. After his entrance into

Jokerit, Harkimo initiated another dream, which was to build a new modern multi-arena in Helsinki, a project that was completed in 1997 when Hartwall Arena was opened (Aalto

1992, 259–272, Mennander 1997, 9–11, 17–44, Mennander and Mennander 2004, 332,

Sjöblom 2007).

Excurse: the Finnish SM-liiga

The Finnish Ice Hockey Federation started modernizing and reconstructing the league system in 1974 due to the stakeholders’ interest in improving domestic elite ice hockey (Finnish Ice Hockey Federation [1975], Development plan, 1 Report; Finnish Ice Hockey Federation [1975], SM-liiga Statutes, Finnish Ice Hockey Federation & Finnish Ice Hockey League [1975], Agreement). In connection with the foundation of the SM-liiga, an organi-zational change was announced, according to which the SM-liiga was going to operate independently of the Finnish Ice Hockey Federation, even though a formal agreement was to regulate the parties’ rights and obligations (Finnish Ice Hockey Federation [1975],

SM-liiga Statutes, Finnish Ice Hockey Federation & Finnish Ice Hockey League [1975], Agreement). First of all, the significant factor was that the SM-liiga, inspired from NHL,

became a closed league in 2000/2001. This was clearly a huge step away from the traditional organization of Finnish elite ice hockey with its deep tradition of promotion and regulation, which was normally profoundly rooted in the Nordic traditions and the European sport model. Still, the league was (re)opened for promotion and relegation 2008/2009 when qualifying matches (best of 7) were introduced between the last team in the premier league (SM-liiga) and the winner of the second league (Mestis). This system was in operation to 2012/2013 when, once again, a shift to the closed NHL-inspired system was reinstated in 2013/2014 and still prevails (2018/2019).

Secondly, in addition to this ‘closedness’, the absence of ownership restrictions for (public) limited companies has been an important prerequisite in the transformation of the SM-liiga into a professional and commercial elite ice hockey league. This means that there are no regulations imposing requirements for a non-profit sport club to own a voting majority in a ‘Sport Ltd/Plc’, the so-called ‘51-percent rule’. In comparison, Swedish elite ice hockey applies a 51-percent rule determined by the Swedish Sport Confederation, which restricts

the ownership in a Sport Ltd/Plc (Backman 2018, 99–105, 174–191 and 244–257, Carlsson

and Backman 2015; Mennander and Mennander 2004, 19–32 and 84–89, Mesikämmen 2002).

Post-CCCP hockey: Russian KHL sees daylight

The roots of KHL and the renaissance of Russian hockey lie, of course, in the immense hockey culture of the CCCP and the images of ‘The Big Red Machine’. Thus, a few short historical observations will be indispensable.

‘Canadian ice hockey’ first appeared in the Soviet Union in 1932 when a team of German workers from Berlin played several matches against the Central Red Army Sports Club. It took some time, however, after the end of the Second World War before the development of ice hockey accelerated (Baumann 1988). Its official start in the Soviet Union occurred in 1946 with the establishment of the Soviet Union Ice Hockey Federation and was accom-panied by the first championship in the same year (Kuperman, Szemberg, and Podnieks

2007, 187–188; Baumann 1988). The Soviet Union crowned its first time participation in the 1954 Ice Hockey World Championship in Stockholm by winning the gold medal and

sending shockwaves to Canada (Kuperman 2007b). After this epoch-breaking entry, the

Soviet authorities invested huge resources and money in ice hockey in order to show the

superiority of the communist system to the capitalism of North America (Baumann 1988;

Jokisipilä 2014; Backman 2018). In the prolongation, the ‘Cold War on ice’ culminated

with the unforgettable confrontations in Summit Series ‘72, Canada Cup and ‘Miracle on

ice’ in the Lake Placid 1980 Winter Olympics (Kuperman 2007a; Kuperman 2007b; Sanful

2007; Szemberg 2007). Generally speaking, Soviet hockey, in particular the national team, was impressive and dominated, in principle, the international rinks in the 60 s, 70 s and 80 s. In the middle of the 1980s, President Michail Gorbachev initiated through glasnost (openness) and perestroika (economic reforms) a radical change of the Communist Soviet Union (Gerner 2011, 273; Aleksijevitj 2017; Jokisipilä 2014). In the late 80 s, glasnost and perestroika also exerted an influence on the Soviet ice hockey scene. Victor Tichonov, for instance, the Soviet imperative coach, was in spite of the great victories criticized for his authoritative methods, a disapproval which would have been impossible without the

novel politics of President Gorbachev (Larionov 1989, 134–194). At the same time, it

must be remembered that the huge international success of Soviet ice hockey in the 60 s, 70 s and 80 s was built on authoritarian political governance, with huge individual sacri-fices, in the wake of the political and ideological struggle with the West (Jokisipilä 2014, 305). Nevertheless, the successful and proud Soviet ice hockey was finally buried with the Soviet Union’s dissolution in 1991. By then, as a mark of the magnitude of CCCP hockey, the country had won 7 Olympic gold medals, 22 World Championships and the

1981 Canada Cup (Stark 1997, 17).

Ten years after the systematic reform work, a crashed, but proud and successful Russian ice hockey started after the Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City 2002. In this context, Vladimir Putin offered the former Soviet star defender Vjatjeslav Fetisov the

job as Minister of Sports, which he held from 2002 to 2008 (Leinonen 2013, 289).

Vladislav Tretjak, the former Soviet star goaltender was, in 2006, recruited as chairman of the Russian Ice Hockey Federation. Besides, Alexander Medvedev, with his close connection to the Gazprom gas company, was, together with Fetisov and Tretjak, given the task of rebuilding Russian ice hockey in order to obtain a leading international

position in the sport (Leinonen 2013, 289–291, Jokisipilä 2011). Consequently,

Medvedev became a front person for the progress and image of KHL. In the process of renewal, Fetisov advocated a Russian NHL model, whereas Tretjak supported a re-vi-talization of a Soviet system ruled by the Russian Ice Hockey Federation. This discrep-ancy was solved when Tretjak stepped down from the KHL project. Instead, Fetisov and Medvedev pointed out the direction and worked out a plan whereby a new Eurasian professional hockey league would replace the 1999 Russian Superleague (Leinonen

2013, 289–291). The result was that the Kontinental Hockey League (KHL) was formed

in 2008, ‘created to further the development of hockey throughout Russia and other

nations across Europe and Asia’.5 It was the start of a professional and commercial ice

hockey league at the highest international level with a structure mainly inspired from NHL. Still, complementary to the commercial aspects of the NHL model, the ambitions of KHL have added implicit political aspirations by the aspirations of introducing KHL ‘across Europe and Asia’.

The Russian-Finnish relation

As bordering countries, Finland and Russia/CCCP have had a long common relation. Hence, due to Finland’s geographical location, the historical progress has resulted in several visible Russian influences in Finnish society in general. This relation has been formed by a mutual interest as well as by Finland’s struggle for independence and preservation as a national state. Consequently, this edged relation with Soviet/Russia has also had an impact on Finnish ice hockey as an influential supplement to the impact of NHL and the general Americanization of ice hockey.6

Without doubt, Finnish elite ice hockey has strongly desired to benefit from the knowl-edge of the recognized talented Russian/Soviet ice hockey coaches, with Vladimir Jurzinov – who used to be Viktor Tichonov’s assistant coach – as the paramount example. With Jurzinov as head coach for TPS Turku 1992–1998, a novel dimension was introduced into Finnish ice hockey. Jurzinov introduced professionalization, inspired by Russian/Soviet training culture, with discipline and a firm attitude to an extent which Finnish players had not been used to. As a result, through Jurzinov Finnish ice hockey was rebuilt, with further help and support from several other Soviet/Russian coaches and influential persons, such as Boris Majorov, Vasili Tichonov, Anatoly Bogdanov and Vladimir Jurzinov Jr. Thus, in Finnish hockey, the significance of Russian/Soviet coaching and its skills and knowledge has not only enriched the tactical and individual understanding of the game and the increas-ing degree of trainincreas-ing intensity. Simultaneously, the practical experience of this trainincreas-ing and commitment has also generated a Finnish understanding and appreciation of the culture

of CCCP hockey (Mennander and Mennander 2004; Sihvonen 2004; Backman 2018).

In light of these historical relations between Russia/the Soviet Union and Finland, the transfer of Jokerit to KHL is not remarkable. Nevertheless, the move is definitely special and rather unexpected in view of the general roots of Finnish sports in Nordic Sport Policy as well as in the European Sport Model.

The case/test/‘lab’: Jokerit’s move to KHL

In this part, we will describe some aspects of Jokerit’s move to from SM-liiga to KHL, with a focus on public reactions, the economy and recruitments. In these respects, the case might work tacitly as a ‘social lab’, reflecting several features of the commercialization process and of trends and conditions in Nordic elite ice hockey.

The progress of the transfer and its reactions

Although Jokerit broke the ice, it is not the only Finnish club that has attracted the Russians. Both Tappara Tampere and Oulun Kärpät, for instance, were offered to join KHL in con-nection with the formation of the league in 2008 but decided to continue in the SM-liiga, due to the immaturity and uncertainty of KHL (Iltalehti 2013-06-29). Still, Kärpät’s former CEO, Juha Junno, related Jokerit’s decision to the sales of Hartwall Arena (Pärnänen 2014). However, Kärpät, like other Finnish clubs, was ‘more interested in Western co-operation’, in which the formation of Champions Hockey League (CHL) played an essential role

(Pärnänen 2014). Perhaps, without this European opportunity, other clubs than Jokerit

Furthermore, Espoo Blues Hockey Ltd had far-reaching plans to join KHL in 2011 when Gennady Timchenko, the Finnish-Russian oligarch, whose fortune was estimated at $14.1 billion, aspired to purchase the club when it was for sale. However, when Espoo Blues’ owner Jussi Salonoja offered the club to Finnish investors, the KHL plan was abandoned (Iltalehti 2013-06-29, 2013-07-09; Ilta-Sanomat 2013-06-29).

Surely, the announcement that Jokerit had been granted access to the KHL and, addi-tionally, that Hartwall Arena had been sold was received with mixed feelings. Basically, KHL received Jokerit with open arms, while the league clubs in SM-liiga opposed the move

(Backman 2018, 314). The supporter reaction was also divided. Some supporters criticized

Jokerit’s leadership for not informing them or discussing with them the imminent move to KHL. Thus, for the younger fans, Russia was not the essential problem. The problem was the way the move was conducted. No serious information had been given to the supporters, despite being faithful fans and game visitors. Besides, some of the older supporters main-tained that the classic games in SM-liiga between the Finnish combatants would be missing. Yet, their dominant opinion was that Jokerit should stay in Finnish majority ownership (Helsingin Sanomat 2013-06-29). However, there were also fans who believed that Jokerit betrayed Finnish ice hockey. One burning issue, for instance, was how to follow Jokerit in, as stated, ‘a foreign league’. For sure, the geographical distances in KHL are significant, as a supporter strikingly claimed: ‘I’m not going to go to Siberia at the moment’ (Nuutinen 2013).7

The Finnish Ice Hockey Federation’s attitude to having a Finnish team in KHL has also fluctuated over time. In an interview, Kalervo Kummola, its former chairman, stated for instance that two years before Jokerit’s move was completed, he had wanted to stop it, but that his attitude had changed gradually (Ilta-Sanomat 2013-06-29), the increasing migration of Finnish players and coaches to KHL being an important motivation. The sales of Hartwall Arena also affected the decision (Helsingin Sanomat 06-29; Iltalehti 06-29, 2013-07-09; Ilta-Sanomat 2013-06-29).

Discussions in various Finnish media also focused on the political significance of KHL’s expansion to Finland, in addition to the sporting effects (Helsingin Sanomat 2013-06-29;

Ilta-Sanomat 2013-06-28; Iltalehti 2013-06-28; Jääkiekkolehti, Nro. 7, 2013; Jääkiekkolehti

Nro. 1, 2014; Jääkiekkolehti Nro. 8, 2014; Jääkiekkolehti Nro. 9, 2014). Prior to the expansion to Finland, KHL had expanded in former Eastern Europe, to the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Latvia, Ukraine, Belarus and even Croatia, as well as to Asian Kazakhstan. In the post-World War II and the Cold War perspective, but still in the wake of glasnost and perestroika, Jokerit’s move was unique. Thus, this Finnish club was the first club, apart from the former Soviet satellite states, to take the step (Ilta-Sanomat 2013-06-29).

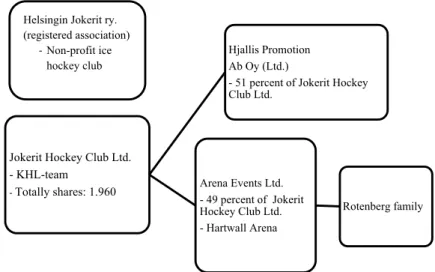

Spending secures Russian minority ownership

Jokerit’s move to KHL had a significant effect on the organization. The traditional form was abandoned, and instead Jokerit Hockey Club Ltd. was established as the operative commercial legal form, holding 1,960 shares with equal voting power.8 Jokerit Hockey Club

Ltd. is, consequently, the owner of Jokerit’s players as well as of the team’s business opera-tions. In conjunction with the press conference came the information that Hartwall Arena had been sold to the Russian investors, which entailed a serious (psychological) predicament. Since the opening in 1997, the Arena had been the home of the Finnish national team

(Ilta-Sanomat 2013-06-29). Actually, the business of elite ice hockey took the new step in Finland

business deal meant that 51 percent of Jokerit Hockey Club Ltd. remained in Harkimo’s ownership, while 49 percent was owned by Arena Events Ltd., which since then has also

acquired Hartwall Arena. The owners of Arena Events Ltd. (see Figure 1) are the

Finnish-Russian oligarchs of the Rotenberg Family, in conjunction with Gennady Timchenko (Helsingin Sanomat 2013-06-29; Iltalehti 2013-06-29; Ilta-Sanomat 2013-06-29). During the purchase, Timchenko stated that KHL’s expansion to Finland was a major step forward in the league’s ambition to become established throughout Europe (Helsingin Sanomat 06-28; 06-29; Ilta-Sanomat 06-29; 07-04; Iltalehti 06-28; 2013-06-29; 2013-07-01). What was important in the purchase and the business deal, however, was to maintain the sporting, commercial and identity-creating base intact, with Jokerit’s traditional brand and image as the solid foundation.

The Finnish business magazine Kauppalehti, which has examined the business docu-ments submitted to the Finnish authorities in relation to the purchase and the deal, reached the conclusion that the Russian investors had paid 3.4 million EUR for 48.98 percent of Jokerit Hockey Club Ltd. In addition, the price for Hartwall Arena amounted to 36 million EUR (Kauppalehti 2014-09-17). These figures, however, appear rather modest given Jokerit’s merits and, in particular, Hartwall Arena’s size and geographical location. Still, there are explanations for this modest price. First of all, the buyers had to cover the previous year’s financial deficits. Secondly, and quite decisively, Harkimo wanted to enter and register Jokerit in KHL at any cost and without any serious hesitation. Harkimo’s interest seems to have been driven by the heavy burden to run and operate Hartwall Arena, as well as by a declining interest in ice hockey business, in addition to Jokerit’s economic losses and several years’ failure to win the Finnish championship (Helsingin Sanomat 2013-06-29, 2013-07-03;

Iltalehti 2013-06-29; Ilta-Sanomat 2013-06-29).

Financial and legal issues

From having an annual turnover of approximately 8 million EUR in 2013/2014, Jokerit’s budget increased to about 20–25 million EUR during the club’s first KHL season 2014/2015

Jokerit Hockey Club Ltd. - KHL-team

-Totally shares: 1.960

Hjallis Promotion Ab Oy (Ltd.)

- 51 percent of Jokerit Hockey Club Ltd. Arena Events Ltd. - 49 percent of Jokerit Hockey Club Ltd. - Hartwall Arena Rotenberg family Helsingin Jokerit ry.

(registered association) - Non-profit ice

hockey club

(Helsingin Sanomat 2013-06-29; 2014-03-11). Besides, the premiere season was successful with regard to spectators, reaching an audience size of 10,932. In comparison, the audience for Jokerit the season before ‘the historic move’, in SM-liiga, was 9,252 spectators (Alliance

of European Hockey Clubs 2019).

Although Jokerit, during the club’s first KHL season, attracted a large audience to Hartwall Arena, Jokerit Hockey Club Ltd. made an economic loss, largely due to high payroll and

travel expenses (Rajala 2016b). According to preliminary data from Kauppalehti (Rajala

2016b), this deficit amounted to several million euro, which were to be covered by the Russian stakeholders. However, according to the same source, they did calculate with neg-ative records initially (Rajala 2016b; Backman 2018, 316–317). The actual size of Jokerit Hockey Club Ltd’s budget, annual turnover and financial loss became public in the spring of 2016, according to current Finnish stock company rules. Thus, Jokerit’s total turnover was 11.6 million EUR, while the budget for the KHL adventure was 23.1 million EUR, of which the payrolls accounted for 12.6 million EUR (cf. Kauppalehti 2014-09-17). Consequently, Jokerit Hockey Club Ltd’s loss was 13.5 million EUR that year.

Even though the budget notably came to more than twice the size, the annual economic growth only increased marginally from the previous position in SM-liiga. Nor did Jokerit’s second KHL season improve financially. The annual turnover was 10.2 million EUR, which was 1.4 million EUR less than the first year, while the loss amounted to a total of 15 million

EUR (Rajala 2016a). This ‘paved road’ continued during the third season, when the loss

amounted to 14.9 million EUR (Rajala 2017).

At the time, it was remarkable that Jokerit’s annual turnover was no more than 7.7 million EUR. Yet, this situation can in part be attributable to falling public revenues and the absence of a major television agreement. In comparison, the SM-liiga clubs Oulun Kärpät (10 m EUR), IFK Helsinki (9.8 m EUR) and Tappara Tampere (8.4 m EUR) had higher annual sales of 10, 9.8 and 8.4 million, respectively (Rajala 2016a, 2017). On the whole, Jokerit’s first three KHL seasons ended with an economic loss of almost 45 million EUR.

The financial deficits have been covered by the new club owners as well as by the arena owners (Kauppalehti 2014-09-17). Apparently, the Russian investors have paid a form of ‘loss guarantee’ for the seasons in question (Rajala 2016b). This economic development has of course not been desirable. The expected symbiosis with television has not yet given the desired effect, although Jokerit is able to sign a separate KHL TV agreement for Finland. Thus, all these TV revenues have gone to KHL in order to decrease Jokerit’s financial deficit (Rajala 2017).

In Ilta-Sanomat, the day after Jokerit’s preliminary financial report for the third KHL season, the club presented their understanding of the economic situation, during which the board stated that Jokerit would not be economically viable – it was more important to

continue business (Hiitelä 2016). This statement was, rather remarkably but politically

understandably, corrected the following day. The new information was supplemented by the declaration that Jokerit will not become profitable as long as sanctions remain against Russia – due to its annexation of the Crimea in 2014 (Lempinen 2016). This is a significant political reality that Jokerit’s board and management could hardly have envisioned, which has adversely affected the curbed commercial development, even though KHL as a whole

does well, according to Dmitry Chernyshenko, the president of KHL (Häyrinen 2016).

The political reality has also affected the capital flow between Russia and Finland. For this reason, player wages have been delayed with some regularity. Undoubtedly, Jokerit has

a great deal to work with in regard to financial maturity, in a period where Russian money is operating and supporting KHL’s ‘Finnish expansion’. An applicable explanation to the ongoing capital supply from Russia is that KHL’s brand-building, in regard to the economy, cultural settings as well as political image, is considered as being long-termed, and that a huge amount of money and prestige has already been invested. Thus, that ‘Jokerit is very important for KHL, and it is hard to imagine KHL without Jokerit’, has been avowed by KHL president Chernyshenko (Saari 2016). In this respect, Jokerit was regarded as a strong brand, with the potential to help KHL and the future ambition towards Western expansion, to, e.g., Sweden, Germany, Switzerland, Norway and Austria, and as part of ice hockey’s globalization. (Ilta-Sanomat 2013-06-29).

Despite this encouraging Russian financial support and affirmative image, it has been discussed, for instance in Ilta-Sanomat, if these annual deficiencies in Jokerit’s play in KHL, due to legal clauses in the ownership, could result in a takeover by the Russian investors, in case the loss guarantees of the 45 million EUR during the first three seasons in KHL cannot be repaid (Lempinen 2016). What is important to stress is that this legal obstacle has not yet been confirmed or handled. Besides, even though the economic manoeuvres during Jokerit’s first three KHL seasons have been numerous and difficult, there will be an extension of the rights to play in the league. Thus, in the spring of 2017 it was announced that Jokerit had signed a long-term agreement with KHL to continue in the league over the coming five seasons (2017/2018–2021/2022). In a historical perspective, this commercial-ization process – ‘Americancommercial-ization of hockey’ – seems, rather oddly, to be formed according to the epitomes of the Soviet five-year plans.

On the legal front, it was important to solve Jokerit’s breach of contract with the SM-liiga’s shareholder agreement, in the wake of the club’s move to KHL. Originally, all clubs in the SM-liiga are to be considered as shareholders through their mutual cooperation in the Ice Hockey SM-liiga Ltd. To become reconciled with the other clubs in the SM-liiga, Jokerit

paid 5–8 million EUR to the clubs for breaking the shareholder agreement (MTV 2013).

The amount of compensation must be understood in light of Jokerit’s position in the SM-liiga and of being the club attracting the most audiences. The other clubs saw huge revenues disappear when the ‘jokers’ no longer came to visit their arenas (MTV 2013). With this monetary compensation, the clubs in the SM-liiga Ltd. backed Jokerit’s move to KHL (Ilta-Sanomat 2013-06-29).

Another legal question was related to the sales of Hartwall Arena to Russian entrepreneurs, an arena that was largely built with public funds and investments. After an investigation by Paavo Arhinmäki, the Minister for Sports, an enduring Jokerit supporter, it was declared that, according to Finnish legislation, it was more or less impossible to reimburse this kind of public capital 15 years after the original deal (Helsingin Sanomat 2013-06-29, Valtanen 2013). Sporting aspects

On top of issues related to the ownership as well as organizational, financial and legal challenges, sporting aspects were a major concern in relation to Jokerit’s transfer to KHL.

Imperatively, the loss of the local rivalry in Helsinki between Jokerit and IFK Helsinki became a vital reality. Thus, with Jokerit’s move, Finland lost its biggest local sports derby all categories (cf. Wickström 2012). In this perspective, the local rivalry had to stand back for commercial interests and gains in a globalized ice hockey world.

Despite the loss of this animating Helsinki derby, however, some supporters expressed positive feelings regarding this new adventure, believing that the new opportunities could make an appealing progress. In this reasoning, they regarded the KHL championship, Gagarin Cup, as having more sporting value than the Finnish championship, Canada-malja (Canada Bowl), nicknamed ‘Poika’ (Boy), which in turn facilitated an acceptance in some supporter circles. It was also reported in the Finnish media that Jokerit’s move was rather ‘brave’, but that it would not adversely affect Finnish elite ice hockey in regard to ‘sport quality’ (Ilta-Sanomat 2013-06-29; Jääkiekkolehti Nro. 8, 2013). Still, there were some worries. One risk in the wake of Jokerit’s relocation could be, for instance, that more Finnish clubs might consider a move to KHL. If that should happen, Finnish elite ice hockey would, consequently, be undermined at the club level.

Besides, Jokerit’s ‘KHL-move’ has not, initially, involved any major problems for the Finnish national team. On the contrary, in KHL, many Finnish players face high-quality sporting challenges which require stronger performance, which will probably strengthen the Finnish national team in the long run. Yet, this expected outcome has still to be proved in practice, when ‘pros and cons’ are weighed against each other.

Regardless of the traditional organization of Finnish elite ice hockey, KHL matches in Finland add both high-quality ice hockey and money to the arenas. Consequently, the Hartwall Arena audiences are able to watch the biggest star players in Europe and Russia when Jokerit plays. Likewise, the recruitment of players to Jokerit is, in a Nordic perspective, easier due to KHL’s attraction and image as the best league in Europe, as well as by Helsinki being Finland’s capital (Backman 2018, 315; Jääkiekkolehti Nro. 8, 2014). In this respect, the move has opened up for Finnish fans to watch and experience new clubs as well as hockey stars from different countries entertaining and performing ‘high-quality ice hockey events’.

Conversely, with regard to sporting values, the Russian investors’ involvement in Jokerit and the acquisition of Hartwall Arena have met opposition. Thus, Finnish media have discussed the involvement in light of ‘a conflict of interest’ (YLE 2016). The argument is that the Rotenberg family, the buying oligarchs, already possessed interests in SKA Saint Petersburg, as well as in Dynamo Moscow.10 In comparison, franchise owners are prohibited

from owning two different teams in the NHL (Sharp, Moorman, and Claussen 2010, 272–

276),11 due to sporting values and conflict of interests. To stress, ice hockey, as well as all

sport, is built on the principles of fairness, competitive balance and uncertainty of outcome, besides being a topic for sport economics (Lavoie 2009).

Analysis and reflections

Analytically, the ‘Jokerit Case’ could be comprehended and discussed in light of a) local conditions and trends, b) Russian interests and (political) ambitions, as well as c) sport’s global effects, images and expansions – which, sequentially, could be related to the strong

conviction in contemporary society that sport generates economic growth globally.12

Nordic horizon and comparisons

In a local and regional perspective, Jokerit’s move to KHL was a huge step from the tra-ditional organization of Finnish and Nordic ice hockey, as well as of sports in general.

Despite being the most radical sport in light of commercial ambitions, elite ice hockey in Finland, but most particularly in Sweden, has been entrapped – to some extent (SM-liiga) or rather substantially (SHL, the Swedish Hockey League) – in the Nordic sport model. In addition to the general trend of ‘Americanization’, however, the Russian edition of this ‘impetuous commercialization process’, has had an imperative influence on the Nordic progress towards ice hockey as a business, as a market and as an entertainment industry

post-Bosman.13

In spite of Jokerit’s repositioning, we have to observe that Jokerit was not, initially, unique in the Nordic hockey landscape. The Swedish clubs AIK, from Stockholm, and MIF Redhawks, from Malmö (with Copenhagen as a potential lucrative market), received similar invitations, formally as well as informally, which were, however, declined in 2009 (Grefve 2010). Still, there are conditions for several Swedish ice hockey teams, due to large arenas, urban infrastructures and the number of spectators, to become members of KHL. Besides, Percy Nilsson, an entrepreneurial patron, has acted in MIF Redhawks in a similar manner as Harkimo, Mr. Jokerit. Still, he had to maneuvre this Swedish club, like other Swedish Sports CEOs, in a rather dissimilar context, with their ‘popular roots’ and the fervor of a general consensus and traditions. Thus, a basic reason for the Swedish clubs to ignore the Russian call is the hegemony of the Swedish Sports Confederation and the unwillingness of the Swedish Ice Hockey Federation to request and appreciate an opponent to the SHL, the Swedish Premier League, or a ‘Russian club’ on a Swedish soil. Indeed, there are several realistic reasons for Finland to have a team in KHL, while teams in Sweden have held aloof.

First of all, Finland has closer social, cultural and geographical ties to Russia than Sweden.

By being a small and independent country, with Russia/the Soviet Union as a decisive – and precarious – neighbour throughout modern history, Finland has developed a pragmatic attitude (Backman 2018; cf. Jakobson 1999; Jussila, Hentilä, and Nevakivi 2000). In society, for instance, the Russian marks are represented by a speaking minority, the Russian-Orthodox church, Russian food traditions and buildings, as well as Russian-speaking news on YLE (public service). Finnish ice hockey has recurrently received impulses from CCCP hockey by the enrolment of Russian coaches and the use of their authoritative training methods. Regardless of the implicit esteem of CCCP hockey and the ‘Big Red Machine’, Swedish ice hockey has not been affected as concretely and tangibly.

Secondly, in comparison with the organization of the Swedish sports movement, the

absence of a central governing administration and an umbrella organization for Finnish sport has principally eliminated the possibility of a normative regulatory framework for the entire Finnish sporting movement. In comparison, the sports traditions and the basic ideology of the Swedish sports movement (Norberg 2003; cf. Norberg 2011) as an integrated popular movement (by consensus) have impregnated the organizations as well as the mind-sets in Swedish sport at large. This has also has affected SHL, despite its commercial ambi-tions and entrepreneurial acambi-tions (Carlsson and Backman 2015) going beyond the traditions. Importantly, there is no 51-percent rule in Finnish elite ice hockey. Thus, a majority of the shareholders of a limited company operate and steer the company, according to their own preferences and interests. By comparison, the Swedish Sports Confederation has, in this respect, obstructed the increase of commercialization by implementing a 51-percent rule (i.e., Sport Ltd/Plc), a regulation which the Swedish Ice Hockey Federation is bound by, and more or less complies with, in spite of its commercial objectives.

Thirdly, the Finnish SM-liiga has gradually progressed into a closed league, in the mode

of the NHL. The danger of relegation has, thus, vanished. In this respect, the financial operations have become more predictable. At the same time, however, teams from lower divisions have been deprived of the prospect of promotion. The Swedish SHL, on the con-trary, sticks to the European sport model, keeping the logics of promotions as well as rele-gation in an attempt to praise ‘the uncertainty of outcome’, as a crucial sport logic.14 Such

openness is generally cherished in Sweden, particularly in media and among supporters. This difference, regarding the tradition of ‘closedness’ and ‘openness’, has also made clubs, supporters and journalists in Finland more prepared for an adventure in KHL with its NHL copycat.

In all, the orientation towards business has been easier to realize in Finnish ice hockey, which has facilitated Jokerit’s move to KHL, practically as well as mentally and conceptually. In spite of this difference, Jokerit’s transfer will, in the long run, have an impact on Swedish ice hockey’s commercial matureness, both practically and conceptually.

Global horizon: new markets

It is regularly stated that sport generates and offers economic growth, as well as image and city-marketing (Berg, Braun, and Otgaar Alexander 2002/2017). In this perspective, Jokerit’s move to KHL raises questions about commercial opportunities in Russia, as well as in Asia, in light of the search for new (sports) markets.

The gigantic Asian market is highly prioritized by KHL, as well as by NHL. Through Jokerit’s move to KHL, there might emerge beneficial conditions for business networks and operations even for Finnish (and European) enterprises. In this respect, Jokerit’s and the stakeholders’ interests in KHL, and even in games in Eastern Russia, are understand-able. Accordingly, Jokerit’s odyssey in KHL provides opportunities for attracting audiences and sponsors, as well as television and other media. KHL and their sponsors and, conse-quently, Jokerit’s commercial bandwagon/lobby, are given exposure and the possibility to enter markets in Russia and China in a manner that would have been significantly harder without entryways of this kind, through ice hockey events.

KHL’s commercial potential in China was even more accentuated when HC Red Star

Kunlun from Beijing became a full-fledged KHL team in 2016/2017.15 The club was

very rapidly formed in June 25, 2016, with manifest support from the highest political levels in Russia and China. Actually, the agreement was signed under the supervision of Putin and Xi Jinping, during the Russian president’s state visit to China on the day

the team was formed (KHL 2016a, 2016b). KHL can, in this respect, function as an

‘entry’ – as a lobby – to a commercial market that may otherwise be difficult to access. The league has, thus, obtained common political and economic interests from several directions.

Of course, Jokerit and particularly sponsors and businessmen in the hub of Jokerit might receive enhanced economic prospects in the KHL cities in Asia and China. Yet, this com-mercial ‘co-value’ mainly remains a presumption and a vision, which has to be proven by empirical standards. Still, this business-related aspect is certainly an embedded motive behind Jokerit’s involvement in KHL, beyond the ordinary references to KHL’s sporting qualities, challenges and opportunities.

Russian horizon: interests and impact

The inclusion of Jokerit in KHL presents legitimacy as well as authenticity to the KHL project due to Jokerit’s solid position in the Nordic and European ice hockey landscape. From KHL’s angle, Jokerit might in this respect work as an entry – as a sign and ‘brand-ing’ – to other European clubs in commercially advantageous cities, such as Berlin, Vienna, Copenhagen, Zürich and Stockholm. Besides, the Russian acquisition of Hartwall Arena was a strategic business deal in the ambition of creating an entertainment link Moscow – Saint Petersburg – Helsinki (Ilta-Sanomat 2013-06-29). The general view is that Russian export is built on energy, mineral and raw materials. However, after the collapse of the USSR, the media and entertainment industry has developed and grown very fast. Hence, sport business is an important industry in contemporary Russia, and KHL is one of its success factors (Helsingin Sanomat 2013-06-29)

Regardless of these practical concerns, we have to extend our examination and the critical reflections in order to grasp Jokerit’s role in this Russian game.

Surely, KHL stands out as a prompt and serious Russian initiative to revitalize the proud, but declining, Soviet/Russian ice hockey. However, regardless of the Soviet style of ice hockey in the rinks, this revitalization has received an organization model far beyond the history

of the magnificent CCCP hockey (Backman 2018, 284–310; Baumann 1988; Hongxin and

Nauright 2018; Jokisipilä 2011, 2014; Leinonen 2013, 287–291). Yet, the authoritative – ‘militarian’ – elements from this period seem to be part of the progress of KHL. However, the crucial part of the rebuilding has been inspired by the NHL, as well as the commercial aspects of this league/franchise, with the increasing atmosphere of the ‘Americanization of sport’. This ‘American’ part might be seen as paradoxical and ironical due to the history of political antagonism and the aegis of the cold war after WWII. Nevertheless, this commercial attitude, in addition to traditional political governance, has been effectively adapted to progress in contemporary Russia and its everyday life.

Thus, a quite harsh and unruly capitalism in the modus of Russian oligarchism has, post-Gorbachev, altered the Stalinist militant and bureaucratic nationalism of the Soviet Union. Still, the ‘representation of czarism’ has survived both systems and has received a novel and contemporary political dress by the authoritative governance of Putin, Kremlin and the oligarchs (cf. Arutunyan 2014; Wegren 2018). In this political setting, KHL could be presented as an offspring of current Russian political ambitions.

Needless to say, it is actually in this perspective hard to grasp Jokerit’s step, as well as the rationale of KHL’s progress, without considering Putin’s political ambitions and strategies and, consequently, to comprehend Jokerit as an individual case within a more extensive and enthralling ‘master plan’. At a time when the importance of the Warsaw Pact seems to be gradually receding, the prospect of the Kontinental Hockey League and its progress in East Europe and Asia turns up as an interesting substitute.

Hence, KHL can be seen as a ‘hybrid’ with elements of both utility maximization and profit maximization. When it comes to profit, the league has not reached the economic stability of NHL in a natural way, at least not during its first ten years of operation 2008– 2018. On the contrary, the oligarchs, with Putin’s political patronage, have substantially covered the clubs’ finances and investments at large. This makes the question of utility maximization challenging. Utility maximization is regularly used to conceptualize that the money goes to increasing sporting successes by being invested in arenas and players. This

may be the case, even for KHL. Still, we find an additional and latent ‘utility’ related to political image and cultural reputation. In a historical perspective, the Soviet Union, as well as DDR, used sport to increase its political image (cf. O’Mahony 2006). By the development of KHL, the Russian political-administration in a sense follows this strategy. Still, the meth-ods are different. The nation is not explicitly praised. The focus is on teams/cities,16 even

outside Russia, as representations of the ‘Russian’ KHL.

By using the commercial model of NHL and adding political aspiration and the oligarchs’ capital as well as globalization, the progress of KHL might be a way to break NHL’s hege-monic position in ice hockey, as well as a manner for obtaining a political image. Of course, Jokerit is only a small, but vital, piece in this project/masterplan. Regardless of this limita-tion, Jokerit’s adventures in KHL, in regard to hockey, economy and politics, is crucial for the crossroads in Nordic ice hockey.

Postscript

On May 24, 2019, at a notable press conference, it was announced that Jokerit had received a new owner. Earlier on, Jokerit’s majority owner, Harry Harkimo, had bought all of the Russian minority owners’ shares (49 percent) in Jokerit Hockey Ltd and had thus become sole owner of Jokerit. After this purchase, Harkimo had also decided to sell all the shares in Jokerit Hockey Ltd. to the former Finnish star player Jari Kurri (who has five Stanley Cup victories on his merit list).

The strategy behind these business transactions was to increase Finnish ownership in Jokerit and thereby facilitate and enhance Finnish sponsorship as a radical counter move-ment to the questionable Russian investmove-ments. It is anticipated that this move and the return to ‘Finnishness’, as well as to the Jari Kurri brand, will attract the Finnish business more strongly than previously.

In connection with this, it was speculated and assumed, even by Harkimo, that Jokerit, in light of the Russian oligarchs’ minority ownership, had suffered commercially, particularly after the sanctions implemented against Russia after the 2014 annexation of the Crimea. In addition, the oligarch families of Rotenberg and Timchenko, previous owners of Jokerit, had been placed on the US sanction list (Office of Foreign Assets Control), which had restricted their possibilities of doing business in the west. Consequently, the current actions of Jokerit demonstrate how sport, politics and economy can be amalgamated.

All the same, the new owner stated that there will be no change in league belonging and that Jokerit will continue to play in the KHL.

In June 17, 2019, however, it was announced that Kurri, the majority owner, had sold 40 percent of Jokerit to a metals and mining firm, Norilsk Nickel Harjavalta Ltd; a firm affiliated to the Mining and Metallurgical Company Nornickel Group, which is a global Russian com-pany, minority owned by the Russian oligarchs Vladimir Potanin and Roman Abramovich.

Notes

1. In this essay we will concentrate on Finnish (and Swedish) elite ice hockey, even though ice hockey is played in all Nordic countries. Notwithstanding this practice, domestic ice hockey in Norway and Denmark is fairly immature, regardless of some respected exports to NHL and the Swedish leagues.

2. All Finnish sport clubs are registered associations (ry./rf.) according to the Finnish Act (26.5.1989/503) for registered associations unless they are (public) limited companies.

3. Kalervo Kummola has been active in Finnish elite ice hockey for more than four decades, e.g., in the positions of CEO for SM-liiga and chairman of the Finnish Ice Hockey Federation.

4. Harry Harkimo, born in Helsinki 1953, was early devoted to business and sports, especially sailing. His dedication to sailing as a life dream reached its peak when he alone managed to sail around the world in 1986–1987. This challenge and experience developed him as a person and future entrepreneur and testified that he was able to get things done by his own power. By being visible in different public contexts and media, Harkimo has become widely known in Finland, like few others.

5. KHL, ‘About the KHL’, there is no page as the information is on KHL’s website, https://en.khl. ru (2018-10-16); cf. Jokisipilä (2011).

6. In Sweden, as an interesting comparison, the Soviet influence on the progress of Swedish hockey has been quite limited, regardless of the general admiration and acknowledgment of CCCP hockey in the 70s and 80s, and the admiration of the “Big Red Machine”.

7. There is no page number as the information is published on Ilta-Sanomats homepage (own translation).

8. Jokerit Hockey Club Ltd. is also, in legal terms, a subsidiary of Harkimo’s family-owned busi-ness, Hjallis Promotions Ab Oy (Ltd.).

9. The information (2018-03-01) about shares in Jokerit Hockey Ltd. comes from the Finnish Patent and Registration Office.

10. Noteworthy, Dynamo Moscow was formerly supported by the KGB, according to the American business magazine Forbes (Forbes 2013).

11. NHL owners are nevertheless allowed to own teams in minor or junior leagues as well as in other different sport organizations, constituting ownership structures that are not well known (Winfree 2010). Rules to prevent conflict of interest among the players also exist in NHL’s collective bargain agreement (2012–2022), article 31.

12. At least among sports evangelists, there is a tendency to present co-values to sport, such as public health, integration, democracy as well as image and economic growth (Carlsson and Hedenborg 2014).

13. Naturally, elite sport’s resemblance to business in general has been accentuated by EU Law and the Bosman case (cf. Halgreen 2004; Parrish 2003).

14. However, the Major League systems, despite its closedness (franchises) have proven to be more uncertain than the big European leagues when it comes to the annual championships (Anderson 2010).

15. Red Star Kunlun’s women’s team is, strikingly, recognized as a part of the Canadian Women’s Hockey League (CWHL) (cf. Hongxin and Nauright 2018)

16. In this perspective, the designers of KHL follow a global trend, by using ‘sport as city-market-ing’ (van den Berg, Braun, and Otgaar Alexander 2002/2017). For instance, it is stated that every US city with self-esteem ought to have at least one team in the Major Leagues (cf. Rosentraub 1999).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

Alliance of European Hockey Clubs. 2019. Euro Attendance: 2013/2014 and 2014/2015. https:// www.eurohockeyclubs.

Aalto, S. 1992. Jokerit liukkaalla jäällä – 25 vuotta Jokeri-kiekkoa [Jokerit on Slippery Ice – 25 Years of Jokerit-hockey]. Jyväskylä: Gummerus.

Aleksijevitj, S. 2017. Secondhand time. The last of the Soviets. New York: ndom House. doi:10.1086/ ahr/79.5.1658.

Anderson, J. 2010. Modern Sport Law. Oxford: Hart Publisher.

Arutunyan, A. 2014. The Putin Mystique. Bloxham: Skyscraper Publications.

Backman, J. 2018. Ishockeyns amerikanisering: En studie av svensk och finsk elitishockey [the Americanization of Ice Hockey: A Study of Swedish and Finnish Elite Ice Hockey]. PhD Diss. Malmö Studies in Sport Sciences, Nr. 27. Malmö University.

Baumann, R. F. 1988. “The Central Army Sports Club (TsSKA) Forging a Military Tradition in Soviet Ice Hockey.” Journal of Sport History 15 (2): 151–166.

Berg, van den L., E. Braun, and H. J. Otgaar Alexander. 2002. Sports and City Marketing in European Cities. Aldershot: Ashgate (reprint, eBook 2017).

Carlsson, B., and J. Backman. 2015. “The Blend of Normative Uncertainty and Commercial Immaturity in Swedish Ice Hockey.” Sport in Society 18 (3): 290–312. doi:10.1080/17430437.2014. 951438.

Carlsson, B., and S. Hedenborg. 2014. “The Position and Relevance of Sport Studies: An Introduction.” Sport in Society 17 (10): 1225–1229. doi:10.1080/17430437.2014.849433.

Forbes 2013. “Arkady Rotenberg.” forbes.com. http://www.forbes.com/profile/arkady-rotenberg/. Gerner, K. 2011. Ryssland: en europeisk civilisationshistoria [Russia: A European Civilization History].

Lund: Historiska media.

Grefve, D. 2010. “AIK får inte spela i KHL.” [AIK is not Allowed to Play in KHL], aftonbladet.se from https://www.aftonbladet.se/sportbladet/hockey/a/L0611q/aik-far-inte-spela-i-khl

Halgreen, L. 2004. European Sports Law – a Comparative Analysis of the European and American Models of Sport, Diss. Copenhagen University.

Hiitelä, J. 2016. “Hjallis Harkimo myöntää: Ei Jokereista tule kannattavaa” [Hjallis Harkimo Admits: Jokerit Will not be Profitable] iltasanomat.fi. http://www.iltasanomat.fi/khl/art-2000005008491. html

Hongxin, L., and J. Nauright. 2018. “Boosting Ice Hockey in China: Political Economy, Mega-Events and Community.” Sport in Society 21 (8): 1185–1195. doi:10.1080/17430437.2018.1442198. Häyrinen, R. 2016. “KHL uhoaa kovaa talouskuntoa – Jokerit neuotelee jatkosopimusta liigan

kans-sa.” [KHL Blusters Economic Conditions – Jokerit Negotiating New Agreement with the League], aamulehti.fi. https://www.aamulehti.fi/kotimaa/khl-uhoaa-kovaa-talouskuntoa-jokerit- neuvottelee-jatkosopimusta-liigan-kanssa-23856160

Jakobson, M. 1999. Finlands väg 1899–1999: från kampen mot tsarväldet till EU-medlemskap [Finland’s Road 1899–1999: From the Struggle against Czarist Rule to EU Membership]. Stockholm: Atlantis.

Jokisipilä, M. 2011. “World Champions Bred by National Champions: The Role of State-Owned Corporate Giants in Russian Sports.” css.ethz.ch, Russian Analytical Digest, No. 95http://www.css. ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/pdfs/RAD-95-8-11.pdf

Jokisipilä, M. 2014. Punakone ja vaahteranlehti [the Red Machine and Maple Leaf]. Helsinki: Otava. Jussila, O., S. Hentilä, and J. Nevakivi. 2000. Finlands politiska historia 1809–1999 [Finlands Political

History]. Schildst: Esbo.

Kuperman, I. 2007a. “Tarasov’s Unstoppable Dynasty.” In World of Hockey – Celebrating a Century of the IIHF, edited by A. Podnieks and S. Szemberg, 49–62. Bolton, Ontario: Fenn Publishing. Kuperman, I. 2007b. “The Fall of the Maple Leaf and Rise of the Star.” In World of Hockey – Celebrating

a Century of the IIHF, edited by A. Podnieks and S. Szemberg, 36–48. Bolton, Ontario: Fenn Publishing.

Kuperman, I., S. Szemberg, and A. Podnieks. 2007. History of IIHF and Member Associations.” in World of Hockey – Celebrating a Century of the IIHF, edited by A. Podnieks and S. Szemberg, 177–191. Bolton, Ontario.

KHL 2016a. “Enter the Dragon! Beijing club to join KHL.” en.khl.ru. http://en.khl.ru/

news/2016/06/25/308623.html

KHL 2016b. “It’s Official! Kunlun Red Star joins the KHL.” en.khl.ru. http://en.khl.ru/

Larionov, I. 1989. Ykkösketju kapinoi [First Line Revolts], Helsinki: SN-kirjat.

Lavoie, M. 2009. “Ice Hockey.” In Handbook on the Economics of Sport, edited by W. Andreff and S. Szymanski, 542–551. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Leinonen, K. 2013. Leijonapolku: Jääkiekon maailma 2014 [the Lion Path: World of Ice Hockey 2014], Helsinki: Readme.fi.

Lempinen, M. 2016. “Mikä bisneksissäsi oikein mättää, Harry Harkimo?” [What is Rotten in Your Business, Harry Harkimo?], iltasanomat.fi. http://www.iltasanomat.fi/khl/art-2000005010384.html

Mennander, A. 1997. Hjallis Hartwall Areena: Miten mahdottomasta tehtiin mahdollinen? [Hjallis Hartwall Arena: How Did the Impossible Become Possible?]. Helsinki: Otava.

Mennander, A., and P. Mennander. 2004. Liigatähdet – Jääkiekon SM-liiga 30 vuotta 1975–2005 [the League Stars – Ice Hockey’s SM-liiga 30 years 1975–2005]. Helsinki: Ajatus Kirjat.

Mesikämmen, J. 2002. “From Part-Time Passion to Big-Time Business: The Professionalization of Finnish Ice Hockey.” In Putting It in Ice, Volume II: Internationalizing Canadás Game, edited by D. C. Howell, 21–28. Halifax: Saint Mary’s University,

MTV. 2013. ”Harkimo: Jokereiden korvaus väitettyä pienempi.” [Harkimo: Jokerit’s compensation smaller], mtv.fi. http://www.mtv.fi/sport/jaakiekko/sm-liiga/artikkeli/harkimo-jokereiden- korvaus-vaitettya-pienempi/3802112

Norberg, J. R. 2003. Idrottens väg till folkhemmet [Sport and the Welfare Community]. Stockholm: SISU.

Norberg, J. R. 2011. “A Contract Reconsidered? Changes in the Swedish State’s Relation to the Sports Movement.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 3 (3): 311–325. doi:10.1080/194069 40.2011.596157.

Nuutinen, A. 2013. “Jokerifani Mikko Kivinen: Ihan heti en Siperiaan lähde.” [Jokeritfan Mikko Kivinen: I’m not Going to Siberia at the Moment], iltasanomat.fi. http://www.iltasanomat.fi/khl/ art-1288578207401.html

O’Mahony, M. 2006. Sport in the USSR. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Parrish, R. 2003. Sports Law and Policy in the European Union. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Pärnänen, A. 2014. “CHL piti Kärpät SM-liigassa – muuten ehkä KHL:ään.” [CHL Kept Kärpät in SM-liiga – Otherwise Maybe to KHL], is.fi. https://www.is.fi/sm-liiga/art-2000000743054.html

Rajala, A. 2016a. “Jokereille jättitappiot viime pelikaudesta.” [Jokerit Made a Giant Financial Loss Last Season], kauppalehti.fi. http://m.kauppalehti.fi/uutiset/jokereille-jattitappiot-viime- pelikaudesta/LmPRM3nu

Rajala, A. 2016b. “Jokereiden ensimmäinen kausi tuotti jättitappiot.” [Jokerits First KHL-season Resulted in a Giant Financial Loss], kauppalehti.fi. http://www.kauppalehti.fi/uutiset/ jokereiden-ensimmainen-khl-kausi-tuotti-jattitappiot/ZcH9ZvqU

Rajala, A. 2017. “Näin Jokerit on takonut tappiota – Taloudellinen yhtälö vaikuttaa mahdottomal-ta.” [This is How Jokerit Has Made a Financial Loss – ‘Financial Equation Seems Impossible’], kauppalehti.fi. https://www.kauppalehti.fi/uutiset/jokerit-teki-jalleen-jattitappiot--taloudel-linen-yhtalo-vaikuttaa-mahdottomalta/Lrh27QLG

Rosentraub, M. S. 1999. Major League Losers: the Real Cost of Sports and who’s Paying for It. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Saari, R. 2016. “KHL-presidentti: Jokerit on sarjalle tärkeä.” [KHL President: Jokerit is Important for the League], jokerit.com. http://www.jokerit.com/khl-presidentti-jokerit- sarjalle-tarkea

Sanful, J. 2007. “The Miracle and Revenge.” In World of Hockey – Celebrating a Century of the IIHF, edited by A. Podnieks and S. Szemberg, 8–91. Bolton, Ontario: Fenn Publishing.

Sharp, L. A., A. M. Moorman, and C. L. Claussen. 2010. Sport Law: A Managerial Approach, Scottsdale: Holocomb Hatchaway Publishers.

Stark, J. ed. 1997. Svensk Ishockey 75 år: ett jubileumsverk i samband med Svenska Ishockeyförbundets 75-års jubileum, Del II, Faktadelen [Swedish Ice Hockey 75 Years: An Anniversary Book in Connection with the 75th Anniversary of the Swedish Ice Hockey Federation, Part II, Facts]. Vällingby: Strömberg/Brunnhage.

Sihvonen, P. 2004. “Jurzinovilaisuus – Maailman Moderneinta Jääkiekkoa.” [Jurzinov – the World’s Most Modern Ice Hockey.”]. In Liigatähdet – Jääkiekon SM-liiga 30 vuotta 1975–2005, edited by A. Mennander, and P. Mennander, 78–81Helsinki: Ajatus Kirjat.

Sjöblom, K. 2007. “Harkimo, Harry Hjallis”, Biografiskt lexikon för Finland [Biographical Dictionary for Finland], blf.fi. http://www.blf.fi/artikel.php?id=9609

Szemberg, S. 2007. “Old Hockey, New Hockey.” In World of Hockey – Celebrating a Century of the IIHF, edited by A. Podnieks and S. Szemberg, 63–79. Bolton, Ontario: Fenn Publishing.

Valtanen, T. 2013. ”Arhinmäki: Hjallis Harkimo saa pitää tukirahansa.” [Arhinmäki: Hjallis Harkimo Can Keep His Support Money], yle.fi. http://yle.fi/uutiset/arhinmaki_hjallis_harkimo_saa_ pitaa_tukirahansa/6725960

Wegren, S. K. 2018. Putin’s Russia, Lanham, MD: Rowman Littlefield Publishers.

Wickström, M. 2012. HIFK–Jokerit: Taistelu Helsingin herruudesta [HIFK–Jokerit: The Battle of Helsinki]. Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Tammi.

YLE. 2016. “Jokeri-hyökkäjä fanien protestoinnista YleX:llä: Vähän nihkeä fiilis, kun eteläpääty tyhjenee.” [Jokerit-Attacker About the Fans’ Protest Against YleX: A Strange Feeling When the South Curve Was Emptied), yle.fi. http://yle.fi/urheilu/jokeri-hyokkaaja_fanien_protestoinnista_ ylexlla_vahan_nihkea_fiilis_kun_etelapaaty_tyhjenee/8694988

Archive, statutes and other documents

Finnish Ice Hockey Federation [1975], Development plan, 1 Report [Hj1, 1970-I];

Finnish Ice Hockey Federation [1975], SM-liiga Statutes, May 24th 1975 [Hj1, 1970-I];

Finnish Ice Hockey Federation & Finnish Ice Hockey League [1975], Agreement [Cb4 Finnish Sport Museum and Archive in Helsinki

In Finnish: Suomen Jääkiekkoliitto [Finnish Ice Hockey Federation]

SM-liigan yhdistyksen perustamiskirja, toukokuun 24 päivä 1975 [SM-liiga Statutes]

(HJ1, 1970-I)

SJL:n organisaatiotoimikunta (1975), JKS Jääkiekkoliiton kehitämissuunnitelma, 1 Raportti, 1975 [Development plan, 1 Report] (Hj1, 1970-I)

Suomen Jääkiekkoliitto ja Suomen Jääkiekkoliiga (1975), Sopimus [Agreement] (Cb4).

Newspapers and magazines

Aftonbladet Helsingin Sanomat Iltalehti Ilta-Sanomat Jääkiekkolehti Kauppalehti