Filipina Nurses in the National Health Service:

The push and pull factors behind international migration to the United

Kingdom

Catherine Ford 931014T289

International Migration and Ethnic Relations One-year master’s thesis (IM627L)

Submitted: 22nd August 2018

2

Abstract

Theshortage of nurses in developed nations such as the United Kingdom requires an influx of overseas workers, from developing countries including the Philippines, to fill these gaps. However, the issue is more complex than this. The aim of this paper is to explore the major factors that account for the international migration of female nurses from the Philippines, who move to work for the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. This is ensured by analysing the push and pull factors, as well as other contributing themes, using the classic push-pull framework, and human capital and social capital theories. An online survey

questionnaire completed by 75 respondents is used to gather the results. The results show that primarily negative, economic push factors, such as the lack of jobs, lack of professional development and low salaries for nurses are the most prevalent reasons behind nurse migration. In addition, positive pull factors including career growth/progression and higher wages, are the most common reasons stated. As well as economic factors, individual social issues, for example a chance of a better life, better opportunities and greener pastures in the UK, were mentioned. Also, themes surrounding remittances and return migration are also identified, providing the starting point for future research into the area of international labour migration of Filipina nurses.

Key words: push-pull factors, human capital, social capital, National Health Service, the United Kingdom, the Philippines, labour migration

3

List of acronyms

ICU – Intensive Care Unit NHS – National Health Service

OWWA – Overseas Workers Welfare Administration

POEA – Philippine Overseas Employment Administration RN – Registered Nurse

UK – United Kingdom

4

Table of contents

Chapter 1: Introduction ... 6

1.1 Aims and research questions ... 6

1.2 Delimitations ... 7

1.3 Contextual background ... 8

1.3.1 Filipino emigration policy... 8

1.3.2 The NHS and immigration ... 9

1.4 Thesis outline ... 9

Chapter 2: Previous research ... 10

2.1 Focus on Filipina migrants... 10

2.2 Focus on nurses ... 11

Chapter 3: Conceptual framework ... 15

3.1 Push-pull framework ... 15

3.2 Human capital theory ... 16

3.3 Social capital theory ... 18

Chapter 4: Methodology ... 20

4.1 Philosophical stance ... 20

4.2 Research approach and method ... 21

4.3 Data collection ... 22

4.4 Content analysis ... 22

4.5 Sampling ... 23

4.6 Feasibility ... 23

4.7 Secondary material... 24

4.8 Validity and reliability ... 24

4.9 Ethical considerations ... 26

Chapter 5: Results and discussion... 28

5.1 Overall findings ... 28

5.2 Main push factors ... 30

5.2.1 Economic factors ... 31

5.2.2 Environmental factors ... 32

5.3 Main pull factors ... 33

5.3.1 Economic factors ... 33

5.3.2 Social factors ... 35

5

5.5 Return migration ... 39

5.6 Summary ... 41

Chapter 6: Conclusion... 42

6.1 Concluding comments ... 42

6.2 Recommendations for further research ... 45

References ... 46

6

Chapter 1: Introduction

The longstanding global shortage of nurses, predominantly in industrialised nations such as the United Kingdom (UK), requires an influx of overseas recruitment, particularly from developing countries (Alonso-Garbayo & Maben, 2009). To fill the gaps in public healthcare sector jobs, primarily in nursing, the UK actively recruits international workers from the Philippines, as well as India, Bangladesh, and other developing nations (NHS Employers, 2018). For Filipino nurses (along with other healthcare professionals) a Memorandum of

Understanding is in place between both countries’ governments to enable the recruitment

process (ibid). Both the UK and the Philippines are dependent on international labour, albeit for different reasons. For example, the Philippine government relies on economic remittances and the UK healthcare system needs to fill labour shortages (NHS Employers, 2018; O’Neil, 2004). The need for overseas labour in the UK can be considered a pull factor, whereas the reliance on remittances in the Philippines is a push factor.

However, at an individual level, the specific factors that determine the migration of nurses from the Philippines to the UK are more complex. For this reason, this thesis focuses on identifying the push-pull factors involved in the immigration of female Filipino (Filipina) nurses that work in the public healthcare sector – the National Health Service (NHS) – in the UK. This research uses an online survey questionnaire aimed at female nurses from the Philippines to investigate the factors involved in their successful migration process. This introductory chapter explores the aims and research questions of the study; the delimitations of the research area; the contextual background to the NHS and its need for international workers; migration from the Philippines and finally, an outline of the thesis.

1.1 Aims and research questions

The aim of this thesis is to explore the main reasons that account for Filipina workers

migrating to the UK to work in the NHS as nurses. The focus of this research is to determine what pushes Filipina nurses to migrate from the Philippines and/or what pulls this specific group of migrants to work in the NHS in the UK.

To help fulfil the aims of this thesis, two primary research questions are asked. They are as follows:

7

1. What are the main reasons that push Filipina immigrants to live and work in the UK, for the NHS as nurses?

2. What are the main reasons that pull Filipina immigrants to live and work in the UK, for the NHS as nurses?

A further research question:

3. What other issues, if any, are involved with the push and/or pull factors of Filipina immigrants working as nurses in the NHS in the UK?

These questions directly relate to the conceptual frameworks and supporting theories, which will be discussed further in this thesis.

1.2 Delimitations

There are several delimitations which have been made to narrow the scope of this research. First, the focus of this thesis is on migrants from the Philippines that work for the NHS as nurses. The decision to focus on Filipinos was decided because nurses from the Philippines account for the highest overseas demographic of nurses, with over 9,000 Filipino nurses currently working for the NHS (Baker, 2018). Therefore, the international migrant group chosen is a significant sample size to study as it has the potential to yield high responses in the research. Next, the decision to focus on female nurses is due to nursing being a primarily female occupation in most countries (Buchan, et al., 2005, p. 7). For this reason, only females were asked to participate in this study. Consequently, findings presented must be viewed from this specific female perspective. Finally, the research in this thesis is undertaken as an online survey questionnaire. This method has been selected due to time and geographical constraints and the opportunity to distribute the survey conveniently via Facebook. The survey includes both quantitative and qualitative questions, which allows both descriptive answers, as well as statistics, thus allowing some generalisability compared to other qualitative methods. Though the researcher is aware of the benefits of using either a qualitative or quantitative method, due to the aforementioned time and geographical constraints, a combination of both was chosen.

8

1.3 Contextual background

It is important to outline the context of this thesis to fully understand the issues surrounding labour migration. The Philippine government, as well as its citizens, rely heavily on

international migration; for this reason its emigration policy will be outlined. Then, more specifically, the UK-Philippine policy for recruiting nurses will be explored. Some

background into the NHS will be discussed in addition to its dependence on migrant labour.

1.3.1 Filipino emigration policy

The Philippines is a nation that relies on outward migration for economic vitality, for example, the sending of remittances, which provide 20.3% of the nation’s export earnings alone (O'Neil, 2004). The government actively promotes emigration, specifically regarding temporary employment through regulated channels, and has protection policies and support networks in place: for instance, the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA) available for potential Filipino migrants (O'Neil, 2004). The OWWA is a Philippine

government institution that ‘protects and promotes the interest of members’ (Department of Labor And Employment, 2018). There is a membership fee of US$25 which entitles members to a range of services and benefits while they are working abroad (ibid).

A specific organisation, the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA), aids the recruitment process of Filipino nurses to work in the NHS. This agreement between the Philippine and UK governments, called the Memorandum of Understanding, is in place to both ‘promote employment opportunities’ for Filipino nurses (and other health professionals) and ‘develop close cooperation to respond to the need for professionals in the healthcare sector’ in the UK (POEA, 2002, p. 1). To qualify to work as a nurse in the UK, Filipinos must fulfil a variety of non-negotiables: hold a bachelor’s degree of nursing in the Philippines, be in paid employment at the time of application, hold a current Filipino nursing licence and have fewer than six months of their employment contract remaining (ibid, pp. 2-3).

Therefore, it is clear that strict prerequisites are in place for potential overseas nurses from the Philippines to enable them to work for the NHS.

9

1.3.2 The NHS and immigration

Founded in 1948, the NHS is the publicly-funded healthcare system in the UK which remains free at the point of use for patients (NHS England, 2016). It employs 1.5 million people (ibid) and was rated “most impressive overall” compared to healthcare systems in Australia,

Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the US, by the Commonwealth Fund (Davis, et al., 2014). Despite the majority of NHS staff being British, 139,019 workers report being ‘non-British’ (Baker, 2018, p. 5). There are over 200 ‘non-British’ nationalities working for the NHS, with the top 5 being Indian, Philippine, Irish, Polish and Spanish (ibid, p. 3). Currently, the Filipino diaspora constitutes the second largest overseas nationality of NHS, with 15,391 employees (Baker, 2018, p. 3).

The NHS has been heavily dependent on migrant labour due to staff shortages as well as the comparatively high cost of training medical staff in the UK. For this reason, medical

professionals, especially doctors from abroad are preferred (Migration Watch UK, 2012, p. 1). The vast majority of NHS nurses, 84%, are British. However, 6% of nurses are Asian, primarily from the Philippines and India (Baker, 2018). As of September 2017, there were 9,544 nurses of Philippine nationality working in the NHS (ibid). Nurses from the Philippines are the largest international group making them a significant group to research.

1.4 Thesis outline

Chapter One outlines the aim and research questions of this thesis, along with the

delimitations and the contextual background to this topic of discussion. Following this,

Chapter Two explores the existing research into this topic in the form of a literature review. Chapter Three details the conceptual frameworks surrounding this thesis, along with

supporting theoretical perspectives. Then, Chapter Four encompasses the methodology of this research: the philosophical stance of the researcher; the research method and approach; material collection and data analysis; sampling; feasibility; validity and reliability and ethical considerations. Next, Chapter Five analyses the results of the research undertaken for this thesis and finally Chapter Six concludes this thesis with a summary of the findings and recommendations for future research.

10

Chapter 2: Previous research

Having outlined the aims and background of this research, this chapter explores the existing studies surrounding female international labour migration. First, the emphasis will be on studies of Filipina labour migrants and second, of nurses who emigrate to work overseas. There is an abundance of existing literature in these subjects and five relevant studies have been chosen to be discussed in this chapter.

2.1 Focus on Filipina migrants

Jørgen Carling (2005) explores the issue of gender in migration from the Philippines in his paper Gender Dimensions of International Migration. Carling (2005, pp. 8-9) outlines the importance of overseas employment in supporting the Philippine economy as well as the lives of Filipino families since the 1970s. Carling (2005) tracked the increasing levels of female migration; in 1975 just 30% of all Filipino migrants were female, by 1994 this percentage had grown to 60%. Ultimately, the demand for domestic work from overseas and the surplus of female migrants in developing nations such as the Philippines accounts for the increasing number of Filipina workers overseas. Furthermore, the opportunity to earn a higher wage working overseas acts as a significant pull factor (Carling, 2005, pp. 13-14).

From exploring empirical studies, the author finds that research into migrant Filipina workers surrounds the notions of sacrifice and suffering, which is associated with exploitation. Such studies present female migrants as victims (ibid, p. 9). However, Carling (2005, p. 12) argues that more recent studies have challenged the self-coined ‘sacrifice and suffering approach’ to Filipina international migration and instead awards them the possibility to balance self-interest and self-sacrifice. Factors such as high earnings overseas, allowing for remittances to be sent home to their family in order to raise their standard of living, as well as the ability to emulate migrant friends’ and relatives’ lives abroad, all account for pull factors behind female migrants from the Philippines (ibid).

Similarly, Naima Tabassum, Abida Tahiani, Huma Tabassum and Misbah Bibi Qureshi (2014) focus their study on gendered patterns of labour migration from the Philippines between 2001 and 2009. The authors argue that migration ‘should be analysed through a gendered lens’ as the causes for and effects of migration differ between men and women

11

(ibid, p. 78). The reasons behind both internal and international migration, according to Tabassum et al. (2014, p. 78) are a result of the social, political and economic conditions and can be categorised as the push or pull factors. Push factors drive people from a particular area, for instance, unemployment or natural disasters, whereas push factors draw or attract migrants to another area with opportunities of employment and better living conditions, among other factors (ibid).

Using secondary data in the form of statistics from the government of the Philippines, the study highlights gender disparities in different labour fields for Filipino migrants in different employment sectors. Women are more likely than men to fill job roles that are considered ‘feminine’ including roles in ‘services, sales and low level clerical jobs’ however women also account for 73.9% of Filipino labour migrants working in ‘professional and technical jobs’ between 2001 and 2009 (Tabassum, et al., 2014, p. 90). This statistic supports global trends of increasing international migration by women (due to factors such as women becoming more independent and the main income earners) (UN World Survey, 2004, in Piper, 2005, p. 4). Nursing is considered both a professional and a female-dominated career (Simpson, 2004, p. 2) so focusing on migrant nurses in the NHS in this thesis is a relevant sample to Tabassum et al.’s 2014 study.

Tabassum et al. (2014, p. 92) conclude their study by stating that both men and women emigrate from the Philippines, however for the period of time they focused on (2001-2009), women account for almost double the number of international migrants compared to men. This study is a significant research paper for this thesis as it highlights the variances between males and females for Filipino migrants specifically and the segregation of jobs between the sexes. Nursing (which is the career in focus in this thesis) can be considered as both

professional and ‘feminine’ employment and is dominated by female migrants from the Philippines.

2.2 Focus on nurses

A study by Donna S. Kline (2003) titled Push and Pull Factors in International Nurse

Migration aimed to describe the push-pull factors in relation to the international recruitment

and migration of nurses. The study used a review of literature in the field of nurse migration and it found that the primary donor countries were Australia, Canada, the Philippines, South Africa and the UK. The primary receiving countries were Australia, Canada, Ireland, the UK

12

and the United States (US) (Kline, 2003, p. 107). There is a global shortage of registered nurses (RNs) globally, according to Kline (ibid), particularly in the US and the UK, which are the primary host nations of migrating nurses.

The author cites push and pull factors constituting international nurse migration and stresses that ‘both forces must be operating for migration to occur’ (Kline, 2003, p. 108). She

concluded that nurses migrate overseas in search of better wages and working conditions compared to those in their home nation (ibid, p. 107). Also, using existing studies, Kline (2003, p. 108) cites that nurses migrate in search of professional development, opportunities to use their specific skills and knowledge, higher standards of living and decreased risk to personal safety while at work (ibid). Therefore, a range of educational, economic, social and political push and pull factors are involved in the migration of nurses overseas.

For the Philippines, large numbers of nurses migrate to countries including Australia,

Canada, Ireland, the UK and the US (see table, in Kline, 2003, p. 108). Filipino migration is a result of push factors, for example, an oversupply of qualified nurses, minimal employment opportunities and dominant export policy by the Philippine government (ibid). Both the government and families back in the Philippines are heavily dependent on remittances sent back by nurses (ibid, p. 109). The demand for nurse labour in host nations such as Canada, the US and the UK is a major pull factor. With large numbers of nurses from the Philippines, shortages in developed nations can be filled, specifically in English-speaking countries due to Filipinos’ language skills and their qualifications being accepted in these countries (Kline, 2003, p. 109). Kline (2003, p. 111) completed her research by stating that international migration of nurses ‘is expected to remain high’ and there should be steps taken to improve the conditions in industrialised countries for overseas migrants, for instance, examining their recruitment practices, ensuring ethical treatment of foreign nurses and addressing existing problems behind the shortage of nurses.

Hongyan Li, Wenbo Nie and Junxin Li’s (2014) research titled The benefits and caveats of

international nurse migration used the existing, secondary material to determine the factors

influencing international nurse migration and the impacts and issues associated with this type of migration. The authors stated that in general the stream of nurse migration moves from developing nations to industrialised ones and the current largest source of migrant nurses globally, is the Philippines (ibid, p. 314). The authors cited that the global nursing shortage

13

due to increased demands for healthcare is a major factor responsible for the migration of nurses overseas, however, this is not the solitary reason, and in fact, it is more complicated than this (ibid, p. 314-315). For instance, Li et al. (2014, p. 315) stated that ‘nurses are pushed by their home countries and pulled by recipient countries to migrate’. The main pull factors that are mentioned include: ‘the availability of jobs, opportunities for professional or career advancement, professional development, recognition of professional expertise, quality of life improvement, attractive salaries and social and retirement benefits’ among others (ibid). On the other hand, push factors such as ‘low wage compensation, limited career opportunities, limited educational opportunities and unstable and/or dangerous working conditions’ are cited in this research by Li et al. (2014, p. 315).

The authors determined that a combination of both push and pull factors are accountable for international nurse migration. However, the research went further than outlining the push and pull factors involved in international nurse migration and stated that with the positive factors that migrant nurses experience overseas, there are negative aspects such as leaving their families, living in an unfamiliar environment, and experiencing a period of adjustment in their new work environment (ibid). They concluded that the global nursing shortage and the recruitment of overseas nurses have been controversial, and these issues will not be quickly resolved. The blame is placed on flawed national healthcare policies in the source countries and economic and political strengths in receiving countries (ibid, p. 317). In order to resolve this global phenomenon, the authors proposed that both sending, and recipient countries need to contribute to guiding nurse migration in a ‘positive direction’ (ibid).

Álvaro Alonso-Garbayo and Jill Maben’s (2009) study in the UK focused on nurses recruited to work for the NHS from India and the Philippines. The research surrounds the issue of a global shortage of nurses and the need for increased international recruitment in low-income countries and focuses on the UK as the host nation. The authors stated that ‘the decision to emigrate is essentially a personal one’ and the costs and benefits are weighed up. The push-pull factors theory is drawn upon and push factors are described as ‘forces in countries of origin that impel workers to emigrate’ whereas pull factors ‘attract professionals’ to the destination country (ibid, p. 2). The use of the push-pull framework, originally proposed in the late 1800s, is justified due to its flexibility and clarity.

14

Alonso-Garbayo and Maben’s (2009) study aimed to establish the reasons behind the

decision to emigrate to the UK and the data collected is in the form of a case study at an NHS Acute Trust in London. They used a qualitative (interpretive) approach using narratives to explore the internationally-recruited nurses’ expectations and experiences as migrant workers. A longitudinal study, in the form of interviews with six Indian nurses over eight months, and interviews with two cohorts of six nurses from the Philippines working in the UK for 18 months and nine Filipino nurses recruited in the UK for four years, was the methodology of the study. The use of face-to-face, individual, semi-structured interviews allowed for intra-case and cross-case comparisons between the groups, contrasting nurses at different stages of the migration experience and adaptation, as well as comparing Indian and Filipina nurses (ibid).

The study concluded that the interviewees’ decisions to emigrate were complex and influenced by multiple individual, social and cultural factors in their lives. Individually, economic and professional reasons are cited, and socially, family and other social networks are influential. From a cultural perspective, nurses previously working in Saudi Arabia, stated that religion or gender issues influenced their decision to move to the UK to work for the NHS (ibid, pp. 5-6). The authors’ findings validate previous studies on

internationally-recruited nurses and at the same time identify the importance of social networks regarding the decision to emigrate (ibid, p. 7). Overall, this study shows that the decision to migrate to the UK is complex for this group and not entirely based on economic factors. Therefore, along with pull factors such as higher wages in the UK, social networks and the ability to improve skills and knowledge in the form of human capital acquisition, explain the reasons behind Indian and Filipino nurse migration to the UK (ibid).

From the aforementioned research articles, it is clear that the push-pull factors behind the international migration of Filipina nurses are complex and varied. Nevertheless, there are patterns in the reasons cited in the studies in this chapter, including unemployment and low wages in the sending country, and better-paid jobs and opportunities in the host country. Along with push-pull factors, social and human capital is also involved in the migration process of Filipina migrants, which is particularly highlighted in Alonso-Garbayo and Maben’s study (2009, p. 7). For this reason, in this thesis, the primary conceptual framework used will be the push-pull model, mirroring the studies in this chapter, along with supporting theories of social capital and human capital. These will be explored in-depth in the

15

Chapter 3: Conceptual framework

This chapter investigates the conceptual framework used to support the research in this thesis. The push-pull model is discussed as the primary framework for this research. In addition, two supporting theories- human capital and social capital- are explored as they relate to the push-pull model.

3.1 Push-pull framework

Classic push-pull models, that dominated migration research until the 1960s, identify economic, environmental, and demographic factors ‘assumed to push people out of places of origin and pull them into destination places’ (Castles, et al., 2014, p. 28). Generally, push factors include population density and growth, political repression and lack of economic opportunities, whereas pull factors consist of availability of land, political and economic freedom and demand for labour’ (ibid, p. 28). The push/pull framework can explain migration on both a macro and micro level. On a grand scale, essentially, it stems from uneven spatial distribution of labour. For example, in some regions, labour is abundant while capital is scarce, resulting in low wage levels. On the other hand, the opposite exists in other countries, so workers migrate from low-wage economies to high-wage ones (King, 2012, p. 13). On a micro level, the individual is a ‘rational actor’ and the pros and cons of migrating are weighed up before doing so (King, 2012, p. 14). Lee’s (1966) micro-level framework focuses on the supply and demand side of migration. It argues that migration is hindered by intervening factors, for example, migration laws and personal factors, for instance, how the migrant perceives these factors (Hagen-Zanker, 2008, p. 9). So, there is a strong focus on the individual actor in this viewpoint.

In a general sense, ultimately migration occurs due to ‘the interplay of various forces of the migratory axis’ according to Mejia et al. (1979, cited in Kline, 2003, p. 108). For international labour migration, successful migration depends on both the push factors (low wages, high unemployment etc.) and pull factors (for example chronic need for foreign workers to perform menial jobs). In core countries, the pull factors are the benefits for migration, whereas migrants from periphery countries are pushed by negative factors (Oishi, 2005, p. 6). The push-pull model states that the combination of push and pull factors determine the size and direction of

16

migration flow and it is assumed that the more disadvantaged a place is, the higher the prospect of migration occurring (Schoorl, et al., 2000, p. 3) The result is decreased wage differentials and an equilibrium reflecting material and immaterial costs of living according to Massey et al. (1993, cited in Schoorl et al., 2000, p. 3).

For labour migrants in the healthcare sector such as nurses, Mireille Kingma (2002) states that both push and pull factors are involved. For instance, in her study, nurses migrated due to the search for attainable professional development, that was unachievable in their home nation or job. Also, the better wages, higher standards of living and improved working conditions were other factors involved in successful migration, according to Kingma (2002, cited in Kline, 2003, p. 108). These are economic and social push-pull factors that help understand the complexity of migration occurring. For example, often, successful migration occurs due to a wide range of factors, in which the benefits outweigh the costs.

The neo-classical, push-pull framework of migration has been extensively critiqued. On the one hand, it has been cited for its ‘internal logic and elegant simplicity’ according to Malmberg (1997, p. 29, cited in King, 2012, p. 14). However, the failure to explain why so few people migrate, despite the many positive factors to do so has been described as the perspectives’ ‘Achilles heel’ by Arango (2004, pp. 19-20, cited in King, 2012). Arango (ibid) states that he push-pull framework cannot be used to explain why some countries have such high rates of outward migration, compared to other countries with the same economic conditions (ibid). Having said this, due to the push/pull framework including a range of social, economic, political, and environmental factors, at both a micro and macro level, it is an important conceptual framework to use in this thesis.

3.2 Human capital theory

In a general sense, human capital is ‘any stock of knowledge or characteristics the worker has (either innate or acquired) that contributes to his or her “productivity”. Examples include school quality, training, attitudes towards work, etc. (Pischke, 1977, p. 3). Different perspectives on human capital exist, including the Becker stance (1994), which directly links it to the production process and worker’s productivity. In addition, the Bowles-Gintis view

17

states that human capital is the capacity to work in organisations, obey orders, and adapt to life in a capitalist society (Pischke, 1977, p. 5).

Human capital theory states that migration is an investment for an individual and it traditionally studies the movements of non-whites from the global South to the North (Yezer & Thurston, 1976, p. 693). According to Beine et al. (2008, p. 633) ‘at birth, individuals are endowed with a given level of human capital normalized to one’. They then make two decisions: either to invest in education when they are young or to migrate when they are an adult. As adults, people can move to high-wage regions for skilled workers (and unskilled workers) (ibid). In migration studies, human capital is a key individual-level measure of an immigrants’ integration in a host country’s labour market (Brodmann & Polavieja, 2011, p. 59; van Tubergen et al., 2004, p. 705). Migration is viewed as a human capital investment, implying that migration occurs when the returns are higher than the costs (Borjas, 1989, p. 458).

For immigrants, examples of human capital include education, language skills, the age of the migrant, and previous work experience, as well as the length of stay in the host country (van Tubergen, et al., 2004, p. 705). Immigrants “adapt” to the host country labour market conditions and they have higher incentives than native workers to invest in their human capital (Borjas, 1989, p. 472). This process includes ‘accumulation of language skills and the internal migration of foreign-born persons within the host country’ (ibid). It can be expected that migrant workers with higher education levels, better host language skills, and more work experience will perform better in the labour market. This is also true for those who migrated younger, and those who have been in the host country for a long period of time, compared to newly-arrived migrants (van Tubergen, et al., 2004, p. 705).

Similar to the push-pull framework, human capital theory is a traditional approach to explaining migration and has been widely critiqued. For instance, Theodore W. Shultz (1961) highlighted human capital as an investment and included migration of individuals and families in the five categories of the theory. Shultz (1961) states that underinvestment in human capital exists, particularly as some countries place education on par with culture, viewing it as a non-material good (Shultz, 1961, cited in Kolomiiets & Petrushenko, 2017, p. 79). Alfred Marshall (1965) on the other hand, argues that human capital is “neither appropriate nor practical to apply”, and although he realizes that human beings are crucial in labour economics, they are

18

not viewed as production costs. The emphasis is placed on costs for parents in terms of education, rearing and training for their children (Kolomiiets & Petrushenko, 2017, p. 79).

In spite of these criticisms, the Philippines is a country that promotes and supports education, for both male and female children, particularly girls, (World Bank, 2013). This is unique to a developing country, as many traditional societies favour boys being educated (Global Partnership for Education, 2018). As the Philippines relies so heavily on emigration, education is an important human capital investment and arguably, the “costs” for parents educating and training their offspring, as highlighted by Marshall (1965), can be outweighed when successful outward migration occurs and with it the benefits that brings to the family.

3.3 Social capital theory

In brief, the concept of social capital denotes ‘norms and networks that enable people to act collectively’ and can result in positive or negative outcomes (Woolcock & Narayan, 2000, p. 225). The basic idea of social capital is the association of a person’s family, friends, and associates to be called on in times of crisis, ‘enjoyed for its own sake, and leveraged for material gain’ (Woolcock & Narayan, 2000, p. 226). The theory was first introduced by Glenn Loury (1977) as a set of intangible resources in families and communities and the development of young people, however, Pierre Bourdieu (1986) connected the concept to wider human society (Palloni, et al., 2001, p. 1263). Social capital theory focuses on the convertibility of capital and how it is gained through the membership of interpersonal networks and institutions in society. In this process, social capital is converted into other forms and results in the maintenance or improvement of the persons’ position in society (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988, cited in (Palloni, et al., 2001, p. 1263).

Migrant social capital refers to ‘resources of information or assistance that individuals obtain through their social ties to prior migrants’ (Garip, 2008). The risks and costs of migrating are reduced through these resources and networks and, according to studies, the stronger the ties, the greater the likelihood of an individual migration (ibid). Social capital and financial resources ‘increase people’s aspirations and capabilities to migrate’ (Castles, et al., 2014, p. 25). Having previous migrant ties not only increases the likelihood of migration, it helps an individual gain access to financial capital in the form of foreign wages, which leads to the

19

possibility of sending remittances to family in their home country through the accumulation of savings (Palloni, et al., 2001, p. 1264). Similar to human capital theory, social capital can be seen as an investment ‘in interpersonal relationships useful in the markets’ (Lin, 2002, p. 25). For example, for migrants, using their connections in the labour market to secure employment in the host nation is viewed as an investment.

Social networks can be crucial in securing employment in a host nation, particularly for newly-arrived migrants, who depend on family and friends to find them jobs not available in the mainstream labour market (Portes, 1995; Linn, 1999; cited in Reyneri & Fullin (2010, pp. 34-35). On the other hand, social networks can hinder immigrants’ mobility in the labour market due to the specificity of jobs available in the networks’ sphere. The lack of host country-specific social capital for highly educated migrants, as well as immigrant workers being trapped in low-paid, low-status jobs in the secondary labour market, are examples of this (ibid, p. 35). So, social networks can provide important connections to new employment in the host nation but can also result in lack of mobility for migrants in certain employment sectors.

There are perceived controversies in the social capital theory. For instance, Lin (2002, pp. 26-27) explores the issues of collective social capital and the assumed or expected closed, dense social networks. This relates to the investment of the members in the dominant class (of the network) to maintain their position. Membership in said network is clearly based on differentiation, for example, nobility, title, family, therefore excluding outsiders. This reinforces the need for closed dense groupings. However, this issue does not consider mobility in social networks. Lin (2002, p. 27) argues that dense, closed social networks are unnecessary and unrealistic. Instead, the need for bridges in networks is stressed (Granovetter, 1973; Burt, 1992; cited in ibid). For example, using extended social networks to look for an alternative, better employment. However, despite the controversies surrounding the focus of closed social networks, social capital theory is vital in exploring migrant workers in a host nation, for example, Filipina immigrant nurses in the UK.

20

Chapter 4: Methodology

This chapter focuses on the research methodology of this thesis. It explores the ontological and epistemological aspects of research, the research design used, the research method used, the sampling technique, along with issues such as validity and reliability, and ethical

considerations.

4.1 Philosophical stance

According to Alexander Rosenberg (2012, p. 1) philosophy is difficult to define as a subject, which reinforces why it is important to study, particularly the philosophy of social science. Rosenberg (2012, p. 1) argues that research in the social sciences cannot be completed without ‘taking sides on philosophical issues’ and ‘without committing oneself to answers to philosophical questions’ (ibid). The philosophical aspects being referred to are ontology and epistemology.

First, the ontology will be explored. Ontology refers to ‘the nature of reality and what there is to know about the world’ (Ormston, et al., 2014, p. 4). Broadly speaking, social science research has been shaped by two ontological viewpoints- realism and idealism (ibid), however other perspectives exist such as the constructivist and positivist/postpositivist perceptions (Creswell, 2003, p. 19). In this research, a constructivist approach is taken. Constructionism (often referred to as constructivism) implies that ‘social phenomena are not only produced through social interaction but are in a constant state of revision (Bryman, 2016, p. 29). Also, this ontological perspective asserts that ‘social phenomena and their meanings are being accomplished by social actors’ (ibid). So, the researcher believes that reality is socially constructed, and the research undertaken in this thesis is no exception, as the researcher is a social actor.

Epistemology is centred around ‘ways of knowing and learning about the world and focuses on issues such as how we can learn about reality and what forms the basis of our knowledge’ (Ormston, et al., 2014, p. 6). This relates to the objectivity or subjectivity of social research. For instance, with the method of survey questionnaires, as used in this thesis, high levels of objectivity are obtained, compared with interviews or focus-groups. This is due to the method

21

allowing for a distance between the researcher and the respondents (Bryman, 1984, p. 77). The researcher has never met with nor knows the names of any of the respondents, excluding the Filipino friend that distributed the surveys online, so there is little chance of bias. However, it is worth noting that with any research that is undertaken, there is always an element of subjectivity (6 & Bellamy, 2012, p. 2). For example, the subject of Filipino labour migrants working for NHS as nurses has been chosen due to the researcher’s interest in it. This is included as an example of bias in the construction of research and it is ultimately influenced by the researchers’ personal interests, either wittingly or unwittingly (Sarantakos, 2013, p. 13). Therefore, despite the research involving a comparatively objective method, the researcher is aware of the subjectivity of this thesis and that no type of research can be fully objective.

4.2 Research approach and method

In any research, there are two styles of reasoning or two methods of scientific enquiry: inductivism and deductivism (Adams, et al., 2014, p. 9). As opposed to a deductive method, that ‘seeks to draw valid conclusions from initial premises’ (Hammond & Wellington, 2013, p. 40), this research uses an inductive approach. Inductivism observes the ‘world’ and operates from the specific to the general. Patterns or trends in a specific variable of interest, in this case push-pull factors behind the international migration of nurses, are used to formulate a theory behind that variable (Adams, et al., 2014, p. 10).

This research uses a mixture of quantitative and qualitative methods in the form of a survey questionnaire. Quantitative research refers to pre-determined, instrument-based question data and statistical analysis (Creswell, 2003, p. 17). Quantitative data tends to include surveys and experiments and uses closed-ended questions and numerical data (ibid). On the other hand, qualitative research aims ‘towards the exploration of social relations and describes reality as experienced by the respondents’ (Adams, et al., 2014, p. 6). As many of the questions in the survey were closed, providing numerical data, the method is quantitative. Having said this, some of the questions enabled the respondents to write their own answers so the method is also qualitative. Allowing for rich-description in some of the responses, such as the reasons for the nurses emigrating from the Philippines, helps to answer the research questions. Thus, the use of both closed and open-ended questions in the survey equates to a mixture of a quantitative and qualitative research method.

22

4.3 Data collection

To answer the aim and research questions of this thesis, a survey was used. Survey research is ‘the systematic collection of data from a survey population’ (Hammond & Wellington, 2013, p. 137). Most survey data are quantitative, and the aim of a survey is to ‘find out ‘how many’ feel, think or behave in a particular way’ (ibid, p. 138). However, the survey in this research paper can be referred to as a survey questionnaire. It is a self-completing questionnaire and is considered a similar method to structured interviews (Bryman, 2012, p. 233). Self-completing survey questionnaires tend to have fewer open questions, have easy to follow designs, and be shorter to minimize ‘respondent fatigue’ (ibid). They are also cheap to administer, enable respondents to complete the survey at a convenient time for them, and do not have the problem of interviewer variability (asking questions in different ways or in a different order) (ibid). Consequently, for this research, an online survey questionnaire was the most suitable method and is discussed further in Section 4.6.

The survey questionnaire, conducted online using Survey Monkey, includes ten questions, with a mixture of closed and opened-ended questions. The survey was distributed online via

Facebook through a Filipino friend, who works at a nurse in a hospital. Although the official

language of the Philippines is Tagalog, and some respondents may have preferred to answer in their home language, the survey questions were written in English as to be able to work in the NHS a high level of English is needed (NHS Employers, 2016). So, with this, it is assumed by the researcher that all participants were able to understand the English language well enough to participate fully in the survey.

4.4 Content analysis

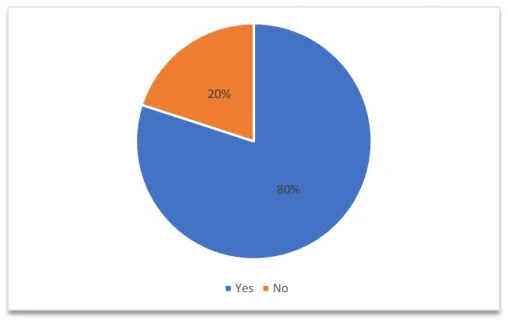

In social science research, after the information has been collected, the following stage is to analyse the data to determine if it answers the problem at hand (Guthrie, 2010, p. 7). Microsoft Excel was used to analyse the results collected. For instance, charts were used to present the results in a practical manner without the need to include the whole survey answers for all the respondents. The use of charts, for example, pie charts, was helpful to explain the key concepts of this thesis, for example, showing the high number of respondents stating that they send

23

remittances back to the Philippines. Thus, by inputting the data into Microsoft Excel, comparisons in the data were outlined and the findings could be presented in an effective way in this thesis.

4.5 Sampling

A sample refers to ‘a portion or a subset of a larger group called a population’ (Sutton, 2011, p. 99). Initially, the survey for this thesis research was sent to a Filipino friend working as a nurse, where she distributed it to friends and colleagues via social media. This way of sampling – snowball sampling – is an important way to reduce time constraints associated with this type of research method. In this research, non-probability sampling was used, as the size of n was unknown, so no sampling frame was available.

This small-scale survey questionnaire aims to give a representative view of the wider population in terms of Filipina nurses working for the NHS. This is considered to be a purposive sampling technique as the characteristics of the respondents are known (Sutton, 2011, p. 100). For instance, before completing the survey, on the introduction page explaining the motivation for the research, respondents were only asked to complete it if they were: female; born in the Philippines and Filipino by nationality; and currently working as a nurse for the NHS in the UK. Therefore, by distributing the survey via an associate and highlighting the prerequisites needed to complete it, snowball sampling enables this particular sample to be studied.

4.6 Feasibility

A survey was chosen as the research method over others such as focus groups or interviews for several reasons. Firstly, this technique could easily be accessed by many people within the time constraints of this research. Compared to interviews, for instance, this option is both time and cost-efficient (Denscombe, 2014, p. 5). With interviews, money and resources are needed to travel to, arrange and attend interviews, and a great deal of time is needed to transcribe them afterwards. Also, as the research is focused on the UK and the researcher is studying at university in Malmö, Sweden, this heightens the financial and time pressures for conducting interviews face-to-face. In addition, owing to lack of time and resources, only a limited number of interviews would be undertaken, and organising specific times to conduct them would have

24

been time-consuming. Hence the use of internet surveys to reach many participants living in the UK is justified. The survey was able to be accessed by participants via a web-link and was available to complete 24-hours a day, making it easy for responses at a time that suits them. This is particularly important for nurses, who work unsociable hours, such as nightshifts. So, for many practical reasons, surveys were chosen as the research method for this thesis.

4.7 Secondary material

In addition to primary data, existing (secondary) research material is cited in this thesis. Secondary data refers to ‘analysis of data generated within other studies and made available to the wider research community’ (Hammond & Wellington, 2013, p. 133). Most of this research was sourced from the Malmö University Library and Google Scholar, online, and includes journal articles, books and research papers. The use of secondary data is relatively straightforward, however, issues of access, ethics, and interpretation, are often encountered (ibid, p. 135). For instance, some journal articles and books were unavailable on the Malmö

University Library website, therefore time was spent sourcing these materials elsewhere, for

example on Google Scholar and other online databases.

Initial searches regarding the concepts and theoretical perspectives used in this thesis, UK immigration, and Philippine migration policy were conducted to gather relevant information. The information was then used in the thesis, particularly in the literature review and the results chapter. Using methodological literature, such as assumptions, arguments and debates, along with topic literature, including definitions, questions and scope (Hart, 2001, pp. 3-4) ensured a well-rounded, accurate and referenced discussion of the area of interest was made in this thesis.

4.8 Validity and reliability

Validity and reliability are important in any research. These concepts will now be discussed further. Validity, in quantitative research, refers to the ‘extent to which a concept is accurately measured’ (Heale & Twycross, 2015, p. 66). Simply, it is the ‘extent to which a research instrument consistently has the same results if it is used in the same situation on repeated occasions’ (ibid). It is also the ‘degree to which our statements approximate to truth’ (6 & Bellamy, 2012, p. 21). There are measures of validity, for example, construct validity and

25

internal and external validity. Construct validity is the degree to which the measures of codes used to operationalise a concept really captures what was intended (ibid). Like in other quantitative methods, numerical analysis, with the use of Microsoft Excel, was used to determine if there were any common factors in the data and present such data effectively. This was undertaken with questions 1, 5 and 8 giving the research more operational precision (ibid, p. 22). Internal validity is within a study and refers to the warrant for inferring that an outcome can be explained by one (or more) causal factor(s) (6 & Bellamy, 2012, p. 22). For example, the primary research questions of this thesis aim to determine the main push and pull factors for Filipino NHS workers migrating to the UK.

From the results of this thesis (see Chapter 5) the internal validity is high, as the casual factors have been established. In terms of external validity, this relates to the warrant for inferring that the research can be used in other studies in a similar way (6 & Bellamy, 2012, p. 22) . As this research focuses on Filipino migrants working as nurses specifically, the survey questions will not be able to be used for other migrants from other nations. However, by changing the country of origin, the same framework can be used in other studies. So, excluding the external validity the validity of this research is high.

Reliability is how the subject of interest is measured. The more reliable the data, the more consistent it is (6 & Bellamy, 2012, p. 21). To ensure the research in this thesis has high reliability, the same questions were asked to each participant. This was made possible by providing a standard set of questions on the online survey. Also, to deliver reliable data, it was assumed that all respondents would answer all the questions provided. This was ensured as the survey had a 100% completion rate. The survey did not enable respondents to duplicate responses thereby increasing the reliability of the results (Denscombe, 2014, p. 15). The survey was only able to be accessed via a link sent online. This enabled only respondents who have been recommended via snowball sampling to complete the survey, meaning the intended sample group with relevant characteristics were answering the questions. Preventing multiple responses (using Survey Monkey) ensures that accurate answers are given. This was automatically enabled by the website itself.

A way of testing the reliability of this research is ‘internal consistency’. This can be done by inserting questions that are phrased differently, which essentially ask the same thing (6 & Bellamy, 2012, p. 21). So, if the answers are the same, the reliability is higher. As only 10

26

questions were asked in this survey, this was not able to be done fully. Although, many of the questions involved similar topics, for instance focusing on ‘moving to the UK’. This meant that the topic of questions remained relatively consistent throughout the survey. Overall, high levels of validity and reliability are needed for a successful research project and this thesis includes these.

4.9 Ethical considerations

Unlike the natural sciences, social science research predominantly involves humans therefore when completing research, the moral aspects or ethics need to be taken into consideration (Rosenberg, 2012, pp. 253-255; Denscombe, 2014, p. 78). Additionally, Webster, Lewis and Brown, in Ormston et al., 2014, p. 78 state that ethics should ‘be at the heart of research’ at all stages of research, from the design until reporting and beyond. The key principles of ethical practice remain relatively unchanged over several decades, according to Bryman (2012, cited in ibid) however they have become more central in the research methods discussion. In general, ethical research involves:

• worthwhile investigation that bears no unreasonable demands on the participants; • participation based on informed consent;

• participation that is voluntary and free from any coercion or pressure;

• informing participants of risks of harm and adverse consequences of participation being avoided, and;

• respect of participants’ confidentially and anonymity. (Webster, Lewis and Brown, in Ormston et al., 2014, p. 78).

The survey was designed to be answered easily and relatively quickly online – and the consent form stated that no more than 15 minutes was needed – so for this reason no unreasonable demands were made to respondents. The participants were given a consent form before completing the survey and were free to withdraw at any time. The purpose and nature of the study was provided, along with a statement regarding confidentiality and anonymity. Correspondingly, all responses were anonymised. In the instance that respondents gave names, they would have been changed, but in practice, this was not needed as no names were provided. Hence, the responses were labelled as ‘Respondent No.1’, ‘Respondent No.2’ and so on. As

27

this study was conducted online and could be completed anonymously, with an average completion time of four minutes, it is considered relatively straightforward and low-risk.

28

Chapter 5: Results and discussion

This chapter explores the findings from the survey questionnaire carried out by the

researcher, in order to address the aim and answer the research questions of this study. From the survey answers, two main areas of interest were established, relating to the push and pull factors of international migration by Filipina nurses. In the core country (the UK) the pull factors are the benefits for migration, whereas migrants from the periphery country (the Philippines) are pushed by negative factors (Oishi, 2005, p. 6). First, the overall findings will be discussed.

5.1 Overall findings

According to Buchan et al. (2005) in their survey of internationally recruited nurses in London:

‘there is much written on the "push" and "pull" factors stimulating health

professionals to move and migrate, but little is evidence-based, and not much is known about the profile, motivations and plans of the health professionals who have actually made an international move’ (Buchan, et al., 2005, p. 1).

So, with this in mind, the preliminary questions of the survey questionnaire conducted as part of this thesis’ research, aim to gather some contextual information or “profiles” of the

respondents. Therefore, this section will cover the age of respondents, the length of time they have been working as a nurse and which department or section of the NHS the respondents work in.

The survey yielded results from 75 respondents, who according to the criteria set out, were female, born in the Philippines and Filipino by nationality. They also had to be working as a registered nurse for the NHS, in the UK, at the time of completion. Of the 75 respondents, 27 were between the ages of 45 and 54 years, closely followed by the 25 to 34 age bracket, where there were 24 people. This is shown in Figure 1 below:

29

Figure 1: Age of respondents in years

The next question asked participants how long they had been working as a nurse for. This referred to the duration of time they have been working as a nurse overall, not only in the UK. The responses ranged from one year to 37 years. The most common lengths of time, (the mode), for Filipinas working as nurses in the survey questionnaire was 21 years and 25 years. The average time in years that the respondents worked as nurses was 16 years. So, nursing can be considered a long-term career for these migrants.

The subsequent question asked what department or section of the NHS the nurses worked in. The clear majority of respondents stated that they worked in ‘critical care’ or ‘theatres’. Critical care nurses, often referred to as Intensive Care Unit (ICU) nurses provide care to patients in a critical condition and are ‘some of the most in-demand nurses in this field’. They work long hours and in stressful working environments, making it a challenging job role (EveryNurse, 2018). As a theatre nurse, a high standard of skilled care is provided in each of the four stages involved in an operation in the UK and they work with patients of all ages. As well as being a registered adult, child, mental health or learning disability nurse, specialist training is also required (Health Careers, 2018). So, for these roles, high skills and

qualifications are needed.

The fourth question of the survey questionnaire asked how long the Filipina nurses had been living in the UK for. All the respondents were long-term migrants, according to the United Nations (UN) having lived in the host country for over 12 months consecutively (UN Data, 2018). Of the respondents, 45 nurses stated that they have lived in the UK for between 15 and

30

18 years. These responses mirror Buchan et al.’s (2005) study where they found that between 1999 and 2003, the number of entrants of registered nurses into the UK from other countries significantly increased. The Filipina respondents from this survey questionnaire are among the 12,000 nurses that were admitted to the UK from overseas up until March 2005,

according to Buchan et al. (2005, p.5).

From the opening questions of the results, it is clear that this group of migrants have key factors of human capital, according to van Tubergen et al. (2004, p. 705) needed for adapting to the host country’s labour market, including:

high levels of education- all the Filipina participants are registered nurses, and this is required by the POEA and included in the Memorandum of Understanding by both the UK and Philippine government (POEA, 2002, p. 1);

previous work experience- the respondents’ average length of time working as a nurse was 16 years, and;

length of stay in the host country- 60% of the respondents have been living in the UK for over 15 years.

This means that the nurses in this research are among those who perform better in the host country’s labour market, according to van Tubergen et al. (2004, p. 705), due to their high level of human capital.

5.2 Main push factors

With regard to the first research question – ‘What are the main reasons that push Filipina immigrants to live and work in the UK, for the NHS as nurses?’ – the major push factors highlighted by the survey responses need to be established. The term ‘push factor’ can be classified as economic, environmental and/or demographic and are generally ‘assumed to push people out of places of origin’ (Castles, et al., 2014, p. 28). Push factors, usually from periphery regions, tend to be negative (Oishi, 2005, p. 6). As per the push-pull framework on a micro level, the researcher assumes that the respondents are ‘rational actors’ and that they had weighed up the pros and cons of migrating before they did so, resulting in successful overseas migration. The following push factors identified from the survey responses will be categorised into economic factors and environmental factors.

31

5.2.1 Economic factors

From Question 9 of the survey questionnaire, which asked respondents to ‘Explain the

reason/s that made you decide to leave the Philippines’, several economic push factors can be identified. For instance, ‘lack of jobs or opportunities’ was a recurrent theme among the respondents, as well as the ‘lack of professional growth’ and ‘low salaries’ for nurses.

For example, Respondent No.18, aged between 35 and 44, who has been living in the UK for 13 years but working as a theatre nurse for 22 years, said that:

“There are lots of nurses in the Philippines and there’s not enough jobs for nurses”.

Similarly, Respondent No.5, who is another theatre nurse aged between 25 and 34, working in the UK for two years, cited that the most fundamental reason for emigrating from the Philippines to the UK were economic reasons, those being the:

“Salary Status of Nurses [sic]”

Also, Respondent No.62, an elderly care nurse of 7 years, aged between 25 and 34, cited:

“Lack of progress in the nursing field, slow career growth and low income”

Another participant, Respondent No.48, who is between the ages of 55 and 64 and has been living in the UK for 17 years, has been working as a nurse for the longest time of all

respondents – 37 years. She has worked as a nurse in dialysis, transplants, wards and research sectors. Her reason for moving out of her home nation of the Philippines and to the UK was:

“For further developmental professional development of my carrer [sic] and financial advances”

Castles et al. (2014) highlight the push factors of the classic push-pull framework being a lack of economic opportunities as well as the uneven distribution of labour (ibid, p. 28). On a grand scale, the uneven distribution generally refers to the oversupply of nurses in the global South, (Alonso-Garbayo & Maben, 2009), which includes countries such as the Philippines. Despite being qualified nurses, respondents in this survey raised issues surrounding the lack of job opportunities in their home country. The lack of economic opportunities can also refer to the career progression and low-paid jobs for nurses, as stated in the answers to this survey questionnaire. Therefore, predictably, the economic push factors that were identified in this research match the push-pull conceptual framework.

32

The economic issues highlighted by the respondents echo previous studies in the area of push-pull migration of both female workers and nurses, such as Tabassum et al. (2014, p. 78). From their research into gendered migration from the Philippines, a major push factor was unemployment in the sending country. In the research for this thesis, respondents cited the difficulty to find jobs as nurses in the Philippines. Linking to this, the oversupply of nurses, as stated by Respondent No.18, is another push factor accounting for overseas migration. This mirrors Kline’s (2003) research into nurse migration, which cited the oversupply of qualified nurses as well as the search for professional development (2003, p. 108). This also reflects Li et al.’s (2014) conclusion of professional or career development as a major push factor (ibid, p. 315). Another economic push factor cited by many of the survey respondents in this paper’s research was low income for nurses in the Philippines. Respondents cited ‘small salary’, ‘low income’ and ‘lack of financial stability’ as the major reasons that made them decide to move abroad to live and work. Again, this is similar to Li et al.’s (2014) study into international nurse migration, where they concluded that low wage compensation was a major push factor (ibid, p. 315).

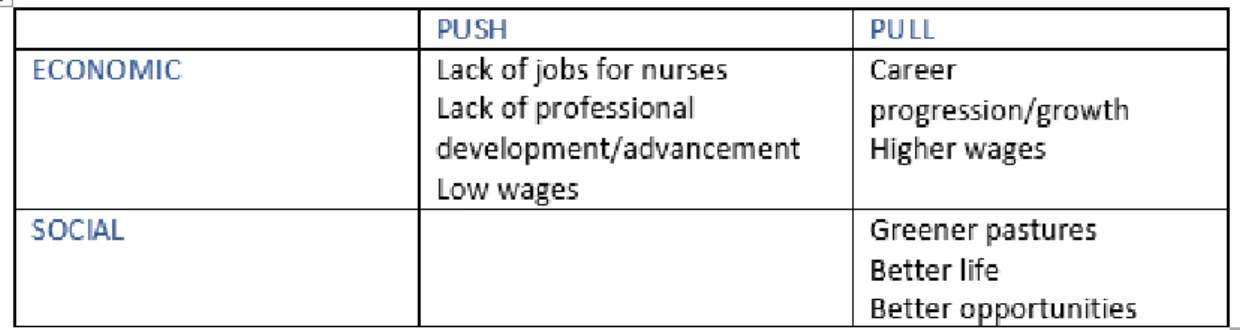

To summarise, the major economic push factors, as classified in the push-pull framework (Castles, et al., 2014, p. 28), identified in this research were lack of jobs for nurses (or oversupply of nurses), lack of professional development in the field of nursing, and low salaries in the Philippines. These factors were most prevalent in the answers and they resonate the findings from existing literature in the area of international nurse migration.

5.2.2 Environmental factors

In the results collected from the survey questionnaires, the nurses did not outline

environmental factors as their primary reason for moving overseas from the Philippines. However, an exception to this was Respondent No.20. She is aged between 45 and 54 and has been working as a nurse for 25 years. Although, she has been living in the UK, with her husband and children, and working as a theatre nurse for 18 years. She explained the main reasons that made her decide to leave the Philippines as:

‘Tired of the hard life, tired of the traffic, the floods…’

This answer was the first and only time that environmental issues were used to explain their push factors. So, environmental factors can be considered a less important issue for the nurse

33

migrants. Having said this, it is important to include this answer as flooding is an

environmental factor as outlined by the classic push-pull model, that identified economic, environmental and demographic factors (Castles, et al., 2014, p. 28). Also, from existing research on the subject, Tabassum et al. (2014, p. 78) state that push factors, such as natural disasters (which flooding can be considered) drive people from a region. Although floods as an environmental impact were outlined in one response, this cannot be considered a major contributing push factor, as it was not a recurrent theme in the participants’ answers. For this reason, to refer to the first research question, environmental push factors are not included in the main reasons that push Filipina immigrants to live and work as nurses in the UK.

Therefore, the main push factors behind Filipina nurse migration to the UK were economic factors and the three main features identified were: the lack of jobs, the lack of professional development, and low salaries for nurses.

5.3 Main pull factors

Similar to Section 5.2, this section will explore the second research question of this thesis which is ‘What are the main reasons that pull Filipina immigrants to live and work in the UK, for the NHS as nurses?’. According to Castles et al. (2014, p. 28), pull factors are those which pull migrants into the destination country, in this case being the UK. These factors tend to be beneficial to potential migrants (Oishi, 2005, p. 6). Question 6 asked respondents to ‘explain the main reason/s why you moved to the UK’. This question is vital in answering the second research question, thus fulfilling the aims of this research. From the respondent’s answers, they can be categorised into economic, social and ‘other’ reasons.

5.3.1 Economic factors

Economic pull factors were outlined by 57 of the participants. Similar to the push factors identified, economic pull factors were the most common responses in the survey

questionnaire. This result was expected as the survey focuses on Filipinas that emigrated to work as nurses in the UK, so they are considered labour migrants. The two recurring themes referred to were ‘career growth/career progression’ and ‘higher wages’ in the UK, although many of the respondents mentioned financial stability as well as the ‘salary’, ‘work

34

factors were more likely to be named by the respondents in the 25 to 34 age bracket, with respondents in the 45 to 54 age group citing both economic and social factors. One deviation from the rest of the results came from Respondent No.8, who is aged between 55 and 64, has worked as a nurse for 37 years and has lived in the UK for 17 years. She stated:

“Pension, NHS state”

The mention of pensions is thought-provoking as it is associated with the matter of returning to the Philippines in the future (see Section 5.4). It can be deduced that the respondent is referring to the NHS pension that she will receive upon retirement as a nurse (NHS, 2018). So, this positive pull factor of an NHS pension that the respondent will gain once she has retired, as it will be considered an investment of migration.

According to human capital theory, migration is viewed as an investment for an individual, once the cost and benefits are weighed up (Yezer & Thurston, 1976, p. 693). The pull factors to the host nation are viewed as generally positive and will benefit the migrant’s life (Oishi, 2005, p. 6). The factors mentioned by participants of the survey including higher wages and the ability for career progression, among other things, are all positive. Therefore, for these nurses, their migration process is considered a human capital investment. For immigrants such as Filipina nurses, examples of human capital include education, language skills, the age of the migrant, and previous work experience, as well as the length of stay in the host country (van Tubergen, et al., 2004, p. 705). The migrants can use their human capital and improve it by migrating to places in need of skilled workers, for example, the UK, which faces a

shortage of nurses (Alonso-Garbayo & Maben, 2009). So, by considering these positive economic factors, such as higher wages and opportunities to grow in their job role in the host country, nurses as labour migrants choose to move overseas to improve their life (Oishi, 2005, p. 6).

All of the results provided by this survey questionnaire regarding economic pull factors that explain the international migration of nurses mirror the existing studies on the topic, as outlined in the literature review chapter. The focus on employment and income, and career advancement in the host nation, in the nurses’ responses are comparable to Li et al.’s (2014) study, in which they concluded that professional or career development and attractive salaries were the top pull factors for nurses who internationally migrate (ibid, p. 315). Similarly, Kline’s (2003) study into the push and pull factors resolved that the search for professional